Public Health Education in Mexico in 2024: National Distribution, Accreditation, and Modalities of Training

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

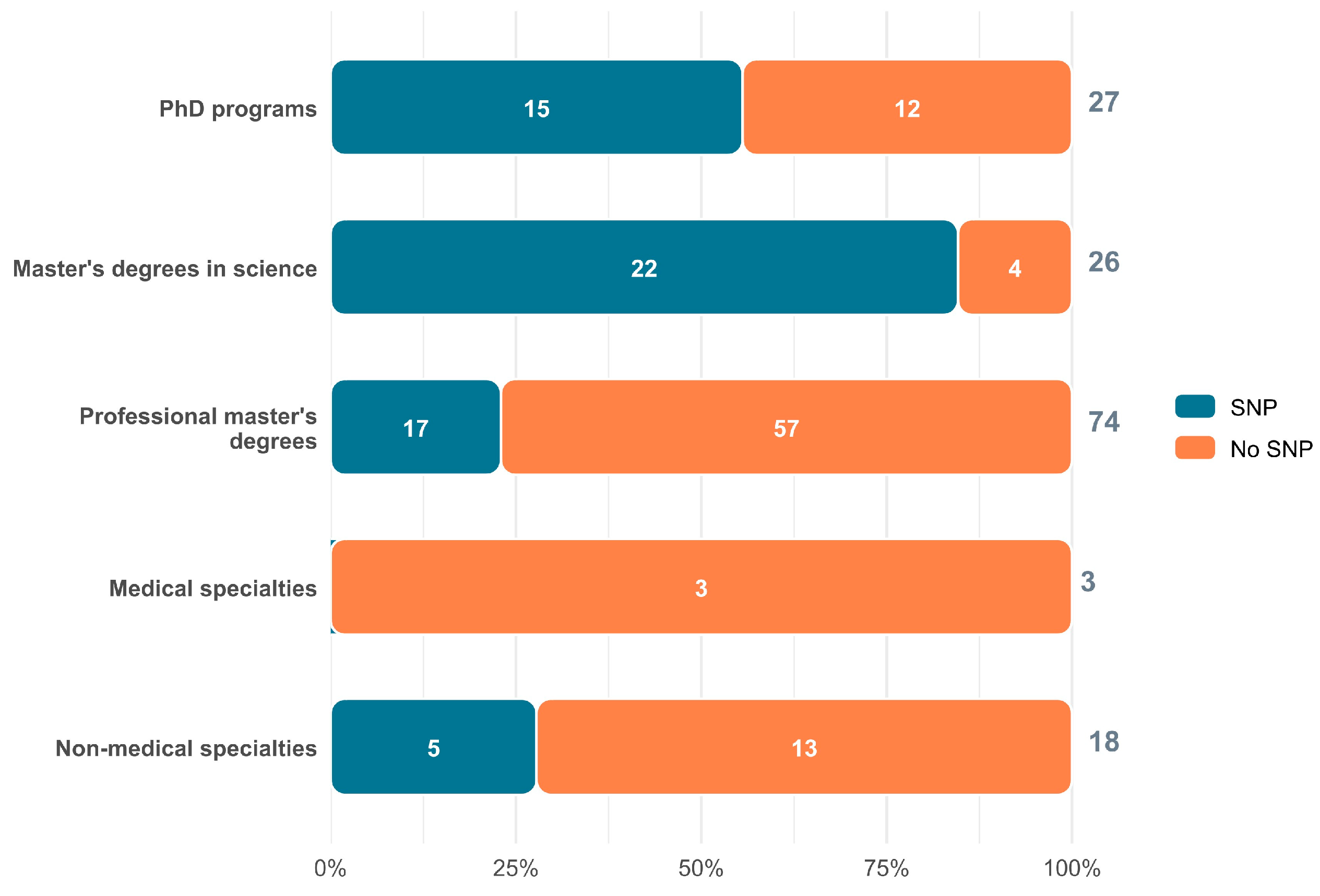

3.1. Institutional Sector and Accreditation Status

3.2. Delivery Modality and Institutional Sector

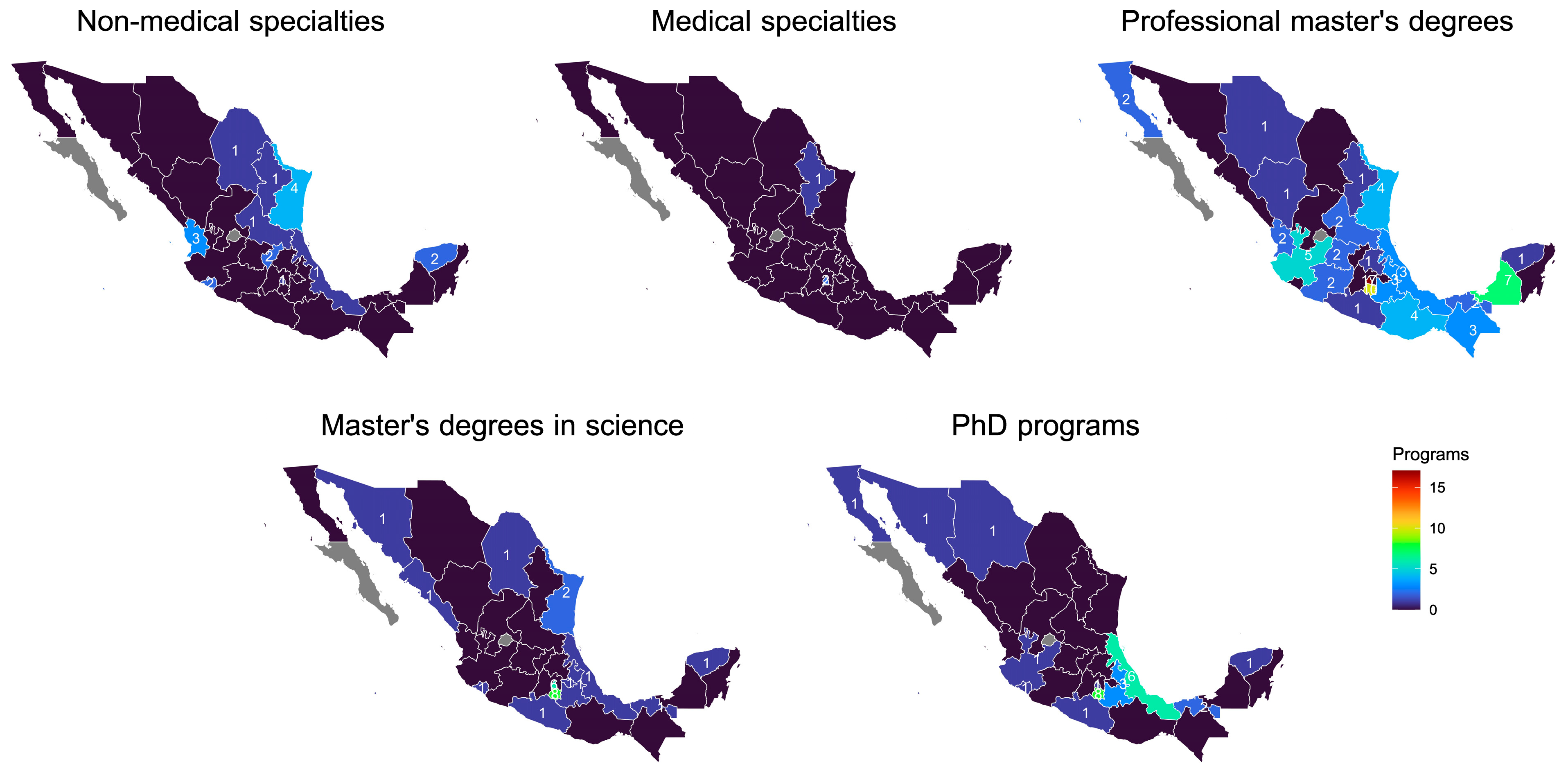

3.3. Geographic Distribution of Programs

3.4. Factors Associated with Accreditation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CONACYT | National Council for Science and Technology |

| ENIF | National Survey on Financial Inclusion |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies |

| INEGI | National Institute of Statistics and Geography |

| NPS | National Postgraduate System |

| PAHO | Pan American Health Organization |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Arrieta, A. Health Insurance and the Contributory Principle of Social Security in the United States of America. Rev. Latinoam. De Derecho Soc. 2016, 23, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, F.; Centurión, M.P.B.; da Silva, J.M.B.; Brandão, A.L. Mapping Public Health Education in Latin America: Perspectives for Training Institutions. Pan Am. J. Public Health 2023, 47, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization. The Essential Public Health Functions in the Americas: A Renewal for the 21st Century. Conceptual Framework and Description; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Narro-Robles, J. Flexner’s Legacy: The Basic Sciences, The Hospital, The Laboratory, The Community. Gac. Med. Mex. 2004, 140, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Pinzón, C.E. The Major Paradigms of Medical Education in Latin America. Acta Medica Colomb. 2008, 33, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Delors, J. The Four Pillars of Education. In Learning: The Treasure Within; Report to UNESCO of the International Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century (Highlights); UNESCO: Paris, France, 1996; pp. 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Galbusera Testa, C.I. The Evolution of Teaching-Learning Models Design in the New Generational Scenario. In Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios en Diseño y Comunicación; Ensayos, DC Publications: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2020; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sandmann, L.R. Adult Learning: A Key for the 21st Century. Adult Learn. 1998, 10, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsti, A.-M.; Margherita, B.; Anusca, F.; Yves, P.; Christine, R. Learning 2.0 the Impact of Web 2.0 Innovations on Education and Training in Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gebbie, K.M. Public Health Certification. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2009, 30, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebbie, K.; Goldstein, B.D.; Gregorio, D.I.; Tsou, W.; Buffler, P.; Petersen, D.; Mahan, C.; Silver, G.B. The National Board of Public Health Examiners: Credentialing Public Health Graduates. Public Health Rep. 2007, 122, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listovsky, G.; Duré, M.I.; Reboiras, F.; Roni, C.; Rosli, N.; Mur, J.A.; Deza, R.; Rosli, J.; Cedro, M.I.F.; Faingold, D.; et al. Strengthening Leadership for Educational Management in the Americas: An Action Research Strategy.Fortalecimento Da Liderança Para a Gestão Educacional Na Região Das Américas: Uma Estratégia de Pesquisa-Ação. Pan Am. J. Public Health 2024, 48, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez Conejero, J.E.; Listovsky, G.; Magaña Valladares, L.; Isabel Duré, M.; García Gutiérrez, J.F.; van Olphen, M. Core Competencies for Public Health Teaching: Regional Framework for the Americas. Competências Essenciais Para a Docência Em Saúde Pública: Um Marco Regional Para as Américas. Pan Am. J. Public Health 2023, 47, e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragelli, T.B.; Shimizu, H.E. Competências Profissionais Em Saúde Pública: Conceitos, Origens, Abordagens e Aplicações. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2012, 65, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Lozano, R. Public Health Teaching in Mexico. Salud Ment. 2018, 41, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña-Valladares, L.; Nigenda-López, G.; Sosa-Delgado, N.; Ruiz-Larios, J.A. Public Health Workforce in Latin America and the Caribbean: Assessment of Education and Labor in 17 Countries. Salud Pública De México 2009, 51, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenk, J.; Chen, L.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Cohen, J.; Crisp, N.; Evans, T.; Fineberg, H.; Garcia, P.; Ke, Y.; Kelley, P.; et al. Health Professionals for a New Century: Transforming Education to Strengthen Health Systems in an Interdependent World. Lancet 2010, 376, 1923–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declercq, E.; Caldwell, K.; Hobbs, S.H.; Guyer, B. The Changing Pattern of Doctoral Education in Public Health from 1985 to 2006 and the Challenge of Doctoral Training for Practice and Leadership. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1565–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangdiwala, S.I.; Tucker, J.D.; Zodpey, S.; Griffiths, S.M.; BChir, M.; Li, L.-M.; Srinath Reddy, K.; Cohen, M.S.; Gross, M.; Sharma, K.; et al. Public Health Education in India and China:History, Opportunities, and Challenges. Public Health Rev. 2011, 33, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Negandhi, H.; Zodpey, S. Current Status of Master of Public Health Programmes in India: A Scoping Review. WHO South-East Asia J. Public Health 2018, 7, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anitha, C.T.; Akter, K.; Mahadev, K. An Overview of Public Health Education in South Asia: Challenges and Opportunities. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 909474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, S.B.; Guttmacher, S.; Nezami, E. Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? The Case for Undergraduate Public Health Education: A Review of Three Programs. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2008, 14, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhagavkar, P.S.; Angolkar, M.; Nagmoti, J.; Zodpey, S. Mapping of MPH Programs in Terms of Geographic Distribution across Various Universities and Institutes of India—A Desk Research. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1443844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Car, L.T.; Poon, S.; Kyaw, B.M.; Cook, D.A.; Ward, V.; Atun, R.; Majeed, A.; Johnston, J.; Van der Kleij, R.M.J.J.; Molokhia, M.; et al. Digital Education for Health Professionals: An Evidence Map, Conceptual Framework, and Research Agenda. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binagwaho, A.; Kyamanywa, P.; Farmer, P.E.; Nuthulaganti, T.; Umubyeyi, B.; Nyemazi, J.P.; Mugeni, S.D.; Asiimwe, A.; Ndagijimana, U.; Lamphere McPherson, H.; et al. The Human Resources for Health Program in Rwanda—A New Partnership. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 2054–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershuni, O.; Orr, J.M.; Vogel, A.; Park, K.; Leider, J.P.; Resnick, B.A.; Czabanowska, K. A Systematic Review on Professional Regulation and Credentialing of Public Health Workforce. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espejo, R.; José, L.; González-Suárez, M. Transformative Learning and Research Programmes in University Teacher Development. REDU Rev. Docencia Univ. 2015, 13, 309–330. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, E.; Figueira, A.R.; Torres, A.R.F. Evaluation of the Implementation of Public Policies in Education: The Case of Capes PrInt at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. Ens. Avaliação Políticas Públicas Educ. 2025, 33, e0255068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Draft Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Academic Level | Total Programs n (%) | Public Institutions n (%) | Private Institutions n (%) | Mean Duration (months) | Duration Range (months) | Included in National Postgraduate System n (%) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bachelor’s degrees | 27 (15.4) | 12 (44.4) | 15 (55.6) | 57.6 | 30–66 | |

| Non-medical specializations | 18 (10.3) | 12 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | 17.4 | 12–36 | 5 (27.8) |

| Medical specializations | 3 (1.7) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 36.0 | — | — |

| Master’s degrees in science | 26 (14.9) | 25 (96.2) | 1 (3.8) | 23.8 | 18–24 | 22 (84.6) |

| Professional master’s degrees | 74 (42.3) | 39 (52.7) | 35 (47.3) | 22.6 | 10–30 | 17 (23.0) |

| PhD programs | 27 (15.4) | 22 (81.5) | 5 (18.5) | 39.1 | 12–48 | 15 (55.6) |

| Total | 175 (100.0) | 113 (64.6) | 62 (35.4) | — | — | 148 (39.9) |

| Academic Level | Total Programs n (%) | Public Institutions n (%) | Private Institutions n (%) | School-Based n (%) | Semi-School-Based n (%) | Online n (%) | Modality Not Reported n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bachelor’s degrees | 27 (15.4) | 12 (44.4) | 15 (55.6) | 24 (88.9) | — | 3 (11.1) | — |

| Non-medical specializations | 18 (10.3) | 12 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | 13 (72.2) | 2 (11.1) | — | 3 (16.7) |

| Medical specializations | 3 (1.7) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (100.0) | — | — | — |

| Master’s degrees in science | 26 (14.9) | 25 (96.2) | 1 (3.8) | 25 (96.2) | — | — | 1 (3.8) |

| Professional master’s degrees | 74 (42.3) | 39 (52.7) | 35 (47.3) | 27 (36.5) | 12 (16.2) | 26 (35.1) | 8 (36.4) |

| PhD programs | 27 (15.4) | 22 (81.5) | 5 (18.5) | 17 (63.0) | 5 (18.5) | 3 (11.1) | 2 (7.4) |

| Total | 175 (100.0) | 113 (64.6) | 62 (35.4) | 102 (58.3) | 19 (10.9) | 32 (18.3) | 22 (12.6) |

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic region (reference: South) | |||

| Northwest | 0.56 | 0.09–3.61 | 0.538 |

| Northeast | 0.62 | 0.13–3.06 | 0.560 |

| West and Bajío | 0.90 | 0.23–3.57 | 0.877 |

| Mexico City | 0.49 | 0.12–2.04 | 0.324 |

| South Central and East | 2.42 | 0.79–7.48 | 0.123 |

| Postgraduate level (reference: Doctorate) | |||

| Non-medical specialization | 0.59 | 0.13–2.70 | 0.495 |

| Master’s degree in science | 7.35 | 1.72–31.34 | 0.007 |

| Professional master’s degree | 0.36 | 0.13–1.01 | 0.051 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the JMMS. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Real-Ramírez, J.; Arias-Carrión, O. Public Health Education in Mexico in 2024: National Distribution, Accreditation, and Modalities of Training. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2026, 13, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms13010004

Real-Ramírez J, Arias-Carrión O. Public Health Education in Mexico in 2024: National Distribution, Accreditation, and Modalities of Training. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2026; 13(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms13010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleReal-Ramírez, Janet, and Oscar Arias-Carrión. 2026. "Public Health Education in Mexico in 2024: National Distribution, Accreditation, and Modalities of Training" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 13, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms13010004

APA StyleReal-Ramírez, J., & Arias-Carrión, O. (2026). Public Health Education in Mexico in 2024: National Distribution, Accreditation, and Modalities of Training. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 13(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms13010004