Simple Summary

Cancer-associated fibroblasts are supportive cells found within the environment of solid tumors. These cells help tumors to grow, spread, and resist treatments by actively changing the tumor environment and modulating immune response. In recent years, scientists have discovered that fibroblasts vary in type and function, and some can be specifically targeted for diagnosis and therapy. This review explores the many roles of these cells in cancer and how they can be used for imaging and treatment, and highlights promising new strategies that may improve cancer detection and open the door to more effective treatments.

Abstract

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are an abundant and diverse cell population within tumor microenvironments of solid tumors. Multiple subtypes of CAFs, defined by molecular and functional markers, have been described in the literature. CAFs contribute to tumor progression by remodeling the extracellular matrix, promoting immune evasion, and supporting angiogenesis and metastasis. Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) is a transmembrane serine protease minimally expressed in normal adult tissues but significantly upregulated in certain subtypes of CAFs across many solid tumors. High levels of FAP have been associated with poor prognosis in various cancers. FAP has increasingly emerged as a promising target for both imaging and therapy. Multiple FAP-targeting strategies, such as small molecules, monoclonal antibodies, drug conjugates, and radiolabeled ligands, are currently being investigated in preclinical and early clinical settings. This review provides a clinically focused overview of CAFs in the tumor microenvironment, highlighting key fibroblast markers, their associations with prognosis across various tumor types, and their utility in radiologic imaging and targeted therapy. We also discuss the potential of non-FAP fibroblast targeting molecules and the clinical rationale for more selective, subtype-specific strategies. By examining fibroblast biology through a radiologist’s lens, we aim to explore the evolving role of stromal targeting in imaging and the treatment of solid tumors.

1. Introduction

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are stroma cells abundantly present in the tumor microenvironment (TME) [1]. CAFs can acquire tumor-promoting phenotypes which significantly impact cancer pathology [2,3,4]. Rather than serving as a passive scaffold, CAFs actively reshape the structural, biochemical, and immunological landscape of tumors, thus facilitating cancer progression, therapy resistance, and immune evasion [5,6]. CAFs constitute a substantial portion of the stromal compartment in most solid tumors, and their abundance is generally linked to poor clinical prognosis, advanced disease stages, and therapeutic resistance [7]. CAFs uniquely bridge mechanical remodeling and paracrine signaling through their secretion of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, cytokines, and growth factors [8,9], modulating both cellular behavior and physical properties of the tumor.

Recent advances in single-cell and spatial transcriptomics have revealed previously unrecognized cell types within the TME, including the discovery that CAFs are not a uniform population but instead comprise functionally and transcriptionally distinct subtypes with context-dependent roles [10]. This heterogeneity, along with their prevalence in tumors, highlights the importance of CAFs as both biomarkers and therapeutic targets [11,12,13]. Recently, attempts to modulate CAFs have included inhibiting key pathways involving TGF-β or targeting specific markers like Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP) [3]. The future of CAF-directed therapy likely resides in precision medicine that selectively inhibits specific pro-tumorigenic CAF subsets [2].

Given the rapid expansion of the CAF literature and the clinical momentum surrounding FAP-targeted agents, a consolidated and up-to-date synthesis is needed. To our knowledge, no recent review has integrated the latest clinical developments in FAP imaging and theranostics, with an updated overview of CAF heterogeneity, molecular function, and emerging non-FAP stromal targets. In this review, we summarize current knowledge on CAF biology, outline their mechanistic contribution to tumor progression, and provide a clinically oriented survey of CAF-directed therapeutic strategies, including, but not limited to, FAP-targeted imaging, radioligand therapy, and stromal modulation. By bridging fundamental stromal biology with evolving clinical applications, this work aims to offer a comprehensive and timely reference for researchers and clinicians in this field.

2. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and the Tumor Microenvironment

Once activated, CAFs play a central role in shaping the TME through reciprocal interaction with cancer cells and surrounding stromal elements [14]. By secreting cytokines, chemokines, and ECM components, CAFs contribute to a protumorigenic niche that promotes malignancy, immune evasion, and resistance to therapy [8,15]. The following sections outline the diverse, context-dependent, roles of CAFs in modulating tumor behavior, immune responses, metabolism, and treatment outcome.

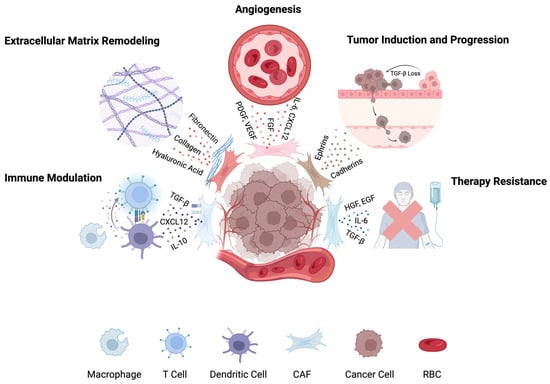

Physical Tumor Microenvironment: CAFs are central in remodeling the ECM by producing collagens, fibronectin, and hyaluronic acid, leading to desmoplasia which is a stiff, fibrotic stroma that elevates interstitial pressure, enhances mechanotransduction, and facilitates tumor invasion and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through integrin and focal adhesion signaling [16,17].

Malignancy Induction and Tumor Progression: Disfunction of the resident tissue fibroblasts can in and of itself lead to malignancy [18]. Pathways implicated in fibroblast induced malignancy include the loss of TGF-β pathway regulation in fibroblasts, activation of the JAK-STAT3 pathway in gastrointestinal tumors and blockage of the CXCR4 receptor in mamillary tissue [18,19,20,21]. Once transformed into CAFs, these cells promote tumor progression through paracrine signaling and ECM remodeling. They secrete growth factors such as TGF-β, HGF, EGF, and IL-6, which drive malignant transformation, therapy resistance, and EMT [22]. CAFs also support angiogenesis via VEGF, CXCL12, and PDGF, facilitating new blood vessel formation and metastatic spread [23,24]. In addition, CAF-derived proteins (e.g., ephrins, cadherins, tenascin-C, and thrombospondin-1) and exosomes contribute to cell–cell interactions and promote both local invasion and distant colonization [25,26,27,28].

Immune Modulation: CAFs suppress anti-tumor immunity by secreting immunosuppressive cytokines (TGF-β, IL-10), expressing checkpoint ligands (PD-L1, PD-L2, FASL), and altering chemokine gradients (CXCL12) to exclude cytotoxic T cells [29,30,31,32]. They promote expansion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and M2-polarized macrophages via IL-6, M-CSF, CCL2, and IL-8, and impair dendritic cell maturation through IL-10 and TGF-β. CAFs also secrete amyloid-β, recruiting tumor-promoting neutrophils [33,34,35,36,37,38].

Metabolic Effects: CAFs support tumor energetics through bidirectional metabolic interactions with malignant cells. CAFs absorb lactate produced by tumor glycolysis and modulate the pH and nutrient composition of the TME [39,40]. They secrete additional metabolites such as alanine to sustain tumor growth under nutrient stress [41].

Therapy Resistance: CAFs contribute to resistance against chemotherapy and targeted therapies through multiple mechanisms. They transfer exosomal RNAs and secrete cytokines like IL-6 that enhance tumor plasticity, leading to resistance to agents such as oxaliplatin and cisplatin [42,43]. Additionally, CAF-induced desmoplasia increases tissue stiffness and reduces vascular perfusion, hindering drug delivery [44].

A schematic overview of CAFs role in the TME is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Roles of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in the tumor microenvironment. CAFs contribute to tumor progression by remodeling the ECM, suppressing immune responses, promoting angiogenesis, enhancing metastasis and proliferation, and driving therapy resistance. Distinct CAF subtypes mediate these processes through secretion of cytokines, growth factors, and matrix proteins. Figure created in BioRender.

3. Heterogeneity of CAFs

Importantly, CAFs do not represent a uniform population. Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), spatial transcriptomics, and lineage tracing have revealed that CAFs consist of multiple phenotypically and functionally distinct subtypes [8,16]. These include myofibroblastic CAFs (myCAFs), which are contractile and matrix-depositing; inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs), which secrete cytokines and chemokines [17,45]; antigen-presenting CAFs (apCAFs), which express MHC class II molecules [12]; vascular CAFs (vCAFs) which are located in perivascular regions; and matrix-remodeling CAFs (mCAFs) which are enriched for ECM-associated genes [46,47]. Each of these subtypes plays different roles in tumor progression, immune modulation, and therapy resistance [7].

CAF subtype composition and spatial distribution are highly context-dependent and may vary with tumor type, stage, anatomical site, and therapy exposure. Some subsets may demonstrate protumorigenic effects, while others may restrain tumor growth or modulate immune responses in more complex ways [8,48]. This functional heterogeneity underscores the need for subtype-specific therapeutic strategies, as global CAF depletion has yielded paradoxical effects in preclinical models [49,50]. Distinct protein expression pattern within the tumor microenvironment have also been shown to influence tumor progression, immune landscape, and therapeutic responsiveness, highlighting the importance of molecular heterogeneity in guiding targeted interventions [51,52].

CAF Markers and Expression Patterns

Identifying CAFs remains difficult due to the lack of a single definitive marker identifying the cell type and their heterogenous and plastic nature. They are typically defined by a combination of positive markers reflecting activation or differentiation, and negative markers to exclude epithelial (EpCAM), endothelial (CD31), and hematopoietic (CD45) lineages [53,54,55].

Among positive markers, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) is a hallmark of myCAFs, which are contractile and contribute to matrix deposition and desmoplasia. However, α-SMA is also expressed by pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells, limiting specificity [56,57]. Fibroblast activation protein (FAP), a membrane-bound serine protease enriched in tumor-associated stroma, is widely used due to its minimal expression in normal adult tissues and its role in matrix remodeling and immune modulation. Still, FAP expression varies by CAF subtype and tumor stage [58,59,60,61]. Fibroblast-specific protein 1 (FSP1/S100A4) marks a broader CAF population associated with motility and metastasis, including non-proliferating or FAP-negative subsets; however, it is also expressed in certain immune and endothelial cells [62,63,64]. Other broadly used markers such as platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFR-α/β) and vimentin (VIM) reflect mesenchymal identity but exhibit cross-lineage expression, being present in pericytes, endothelial cells, and EMT-activated epithelial cells [53,54,65,66].

Recent research has identified emerging markers that further delineate functional CAF subsets. Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 15 (LRRC15) marks TGF-β–responsive CAFs enriched in matrix remodeling and immune suppression, particularly in lung, breast, and pancreatic tumors [67,68]. G-protein coupled receptor 77 (GPR77) identifies CAFs that promote cancer stemness and chemoresistance, correlating with poor prognosis [69]. ApCAFs express MHC class II molecules such as HLA-DRA, and CD74 and may play a role in local immune tolerance within the tumor [12,70]. Additional context-dependent markers include CD90 (Thy-1), podoplanin (PDPN), and tenascin-C (TNC), which are associated with immune modulation, stromal remodeling, and therapy response in specific tumor types [71,72,73,74].

No single marker sufficiently captures the complexity of CAF identity. A combinatorial marker panel approach, informed by tumor type, anatomical context, and functional state, along with integration of multi-omic approaches such as single-cell RNA sequencing remains essential to resolve CAF heterogeneity [56,72]. A comparative summary of key CAF markers, their associated subpopulations, biological roles, tumor-specific expression, and interpretive limitations is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of key cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) markers, their associated subpopulations, functions, tumor-type specificity, and interpretative notes. (PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer).

4. Strategies to Attenuate and Reprogram CAF Activity

CAFs are increasingly recognized as promising imaging and therapy targets due to their role in tumor progression, immune evasion, and therapy resistance [79]. High CAF abundance is associated with poor prognosis and reduced treatment efficacy in many contexts [80,81]. While early strategies aimed at broadly depleting CAF populations, these untargeted approaches have not consistently improved outcomes, and in some cases, have led to accelerated tumor growth and invasion [49,50]. Recognizing CAF heterogeneity has shifted the focus toward selectively targeting pro-tumorigenic subtypes and modulating CAF signaling pathways at various stages of tumor development and immune interaction, rather than broad depletion [3].

To this end several approaches have been explored. One strategy seeks to block the initial activation of quiescent resident fibroblasts into CAFs by targeting upstream signaling pathways such as FGFR, Hedgehog, and TGF-β, though clinical benefit has been inconsistent [82,83,84,85,86]. For example, TGF-β is a central regulator of CAF differentiation, converting quiescent fibroblasts or bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells into activated, tumor-promoting CAFs. In breast cancer models, this transition involves the myeloid zinc finger 1 (MZF1)/TGF-β axis and is associated with increased expression of CAF markers and increased tumor-promoting activity. Inhibition of TGF-β signaling reduces both CAF activation and tumor growth, highlighting its therapeutic promise despite challenges related to its broad physiological functions [76,87].

Other interventions disrupt CAF effector functions, for instance by using FAK or ROCK inhibitors to reduce matrix remodeling, or by targeting PDGFR, LRRC15, FSP-1, and immunomodulatory cytokines such as IL-6 and CXCLs [88,89,90,91,92,93]. Additional strategies include stromal depletion (e.g., PEGPH20 targeting hyaluronic acid) and losartan, an angiotensin II blocker that modulates the fibrotic TME, have shown preclinical promise but limited clinical impact [94,95,96].

Emerging research has revealed the importance of metabolic reprogramming in CAFs. These cells frequently undergo a glycolytic shift, termed the “reverse Warburg effect”, in which non-cancerous stromal cells such as CAFs metabolize glucose via aerobic glycolysis, producing lactate, even in the presence of oxygen. This phenomenon is metabolically similar to the classic “Warburg effect”, which occurs within cancer cells themselves, but in reverse Warburg effect, energy-rich metabolites, such as lactate and pyruvate, produced by CAFs are transferred to adjacent tumor cells to fuel mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [97]. Tumor-derived factors such as TGF-β and HIF-1α drive this metabolic reprogramming in CAFs. The lactate secreted not only supports cancer cell metabolism but also enhances immunosuppression by promoting IL-6 secretion that impairs CD8+ T-cell cytotoxicity [98,99,100]. Pharmacologic inhibition of lactate production using LDHA inhibitors, such as FX11, has been shown to restore antitumor immune responses and enhance the efficacy of PD-L1 blockade [101]. Beyond glycolysis, CAFs also exhibit enhanced glutamine and lipid metabolism that support tumor growth and immune evasion. Targeting these metabolic dependencies offers an opportunity to disrupt stromal–tumor crosstalk and synergize with existing immunotherapies [102].

Another therapeutic approach aims not to eliminate CAFs, but to revert them to a quiescent or tumor-suppressive phenotype [79]. Vitamin D and vitamin A analogs have shown promise in this context by reprogramming activated fibroblasts into a more differentiated, stellate-like state, particularly in pancreatic cancer models [103,104,105]. Similarly, inhibition of HSP70 has demonstrated efficacy in suppressing the pro-tumorigenic functions of CAFs, potentially through disruption of stress response pathways and attenuation of inflammatory signaling [106]. HSP90 has also emerged as a promising target, as it supports ECM remodeling, tumor growth and angiogenesis, which are key processes in sustaining CAF-mediated tumor progression [107,108].

Retinoic acid (RA) signaling is a key regulatory axis in fibroblast differentiation, but its activity can be attenuated by the nuclear receptor co-repressor RIP140. Chromatin immunoprecipitation studies have shown that RIP140 competes with coactivator complexes at RA-targeted promoters, delaying histone acetylation and recruitment of coactivators such as p300/CREB-binding protein-associated factor (P/CAF). The presence of RIP140 suppresses RA-induced gene expression despite ligand binding, and RA treatment induces dynamic assembly of retinoic acid receptor (RAR) coregulator complexes over time. These findings suggest that modulating RIP140 may enhance the transcriptional output of RA signaling in the tumor stroma [109].

While these strategies are supported by encouraging preclinical data, clinical trials evaluating CAF reprogramming remain in early stages. Results have so far been mixed, underscoring the need for precise therapeutic modulation and better characterization of CAF subpopulations to predict response.

5. FAP-Expressing CAFs: A Targetable Subset for Imaging and Therapy

FAP is a membrane-bound serine protease highly expressed in a subset of CAFs across many epithelial cancers, while showing minimal expression in normal tissues [110]. This selective expression supports its use as a tumor-restricted marker for both therapeutic and diagnostic purposes. FAP-positive CAFs contribute to tumor progression through ECM remodeling, immunosuppression, and angiogenesis, particularly in desmoplastic and therapy-resistant cancers [2,111,112]. Despite its variable expression among CAF subtypes and tumor stages, the high tumor-to-background contrast of FAP makes it a promising candidate for imaging and drug targeting [113]. In the following sections, we explore the correlation of FAP+ CAFs with prognosis, the current state of FAP-targeted therapeutic approaches, and emerging clinical applications in molecular imaging and drug delivery.

5.1. Prognostic Implications of FAP Expression Across Tumor Types

FAP expression on CAFs has been explored as a prognostic biomarker in several cancers, though its significance varies by tumor type. In general, high stromal FAP levels correlate with poorer outcomes, especially in aggressive or therapy-resistant tumors [114,115].

Pancreatic and colorectal cancer: Elevated FAP expression correlates with shorter overall and disease-free survival, higher recurrence, and increased metastatic potential [116,117].

Breast cancer: The prognostic significance of FAP is more variable. Some studies have identified a negative prognostic association, particularly in hormone receptor–negative subtypes, while others have reported no clear correlation or even improved survival in certain cohorts [118,119,120].

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Paradoxically, higher stromal FAP levels have been linked to improved prognosis, reinforcing the need for tumor-specific interpretation in clinical settings [121].

Ovarian, hepatocellular carcinoma and neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors: High FAP is associated with advanced stage, treatment resistance, and reduced survival [122,123,124,125,126].

5.2. Strategies to Target FAP

Antibodies and Immunoconjugates: Early attempts to target FAP involved the murine monoclonal antibody F19, which selectively recognized FAP on stromal fibroblasts in epithelial cancers [127]. Its humanized version, sibrotuzumab, entered clinical trials and showed a favorable safety profile in colorectal and lung cancers, but failed to demonstrate meaningful clinical efficacy [128]. To improve efficacy, newer approaches utilize antibody-drug conjugates and radioimmunoconjugates. Agents like αFAP-PE38 and radiolabeled antibodies (e.g., 177Lu-ESC11, 177Lu-ESC14) have shown the ability to deplete FAP+ stroma and suppress tumor growth in preclinical models [129,130]. Immunotoxin αFAP-PE38 was studied in the metastatic breast cancer mouse model [129]. 177Lu-labeled ESC11 and ESC14 have been tested in melanoma xenograft models [130]. In parallel, bispecific antibodies and fusion proteins are being developed to pair FAP recognition with immune modulation. Examples include RG7386 (FAP/DR5), RO7300490 (FAP/CD40), and FAP-4-1BBL, which co-engages T cells to enhance CD8+ T-cell activation and promote tumor regression [131,132,133,134]. FAP-4-1BBL was studied in preclinical rhesus monkey model with colorectal cancer and human patients with epithelial ovarian cancer or NSCLC [133,134]. These advanced constructs demonstrate how antibody formats can be engineered to overcome the limitations of early monotherapies, offering targeted cytotoxicity and immune activation by leveraging the tumor-restricted expression of FAP.

Small Molecule FAP Inhibitors: A major advance in targeting FAP has been the development of small molecules to inhibit FAP, including the quinoline-based FAP inhibitors (FAPI) [135]. Although early FAPI molecules had limited tumor retention time, structural improvements led to newer compounds such as FAPI-04, FAPI-46, and FAPI-74, which have continually improved the FAP binding capability of these molecules. Among these, FAPI-46 offers longer tumor retention and better imaging contrast, while FAPI-74 is suitable for broader clinical use due to dual labeling with 68Ga and 18F [136,137]. These agents have shown superior lesion detection across various cancers (e.g., sarcomas, head and neck, pancreatic) compared to FDG-PET [138]. However, their short biological half-life limits therapeutic applications, although newer versions have improved tumor retention time compared to the original compounds. Current efforts are exploring FAPI-drug conjugates and radioligand therapies to extend their role beyond diagnostics [139]. Li et al. have reviewed and summarized the clinical trials evaluating FAPI-04, FAPI-46 and FAPI-74. Ongoing clinical trials of FAPI-46 include breast cancer (ER-positive, lobular, and triple-negative cancer) [140], lung cancer [141], pancreatic/bile duct cancers [142], hepatocellular carcinoma, cancer of unknown primary [143], prostate cancer, sarcoma [144], and ovarian cancers [142].

Peptides: Peptide ligands offer an alternative to small molecules for FAP-targeting, with enhanced versatility and stability. Among these, FAP-2286, a cyclic peptide optimized for dual diagnostic and therapeutic use, has shown high binding affinity and metabolic stability in preclinical studies [145]. Its radiolabeled form, 68Ga-FAP-2286, demonstrated sustained tumor uptake in a Phase I trial, supporting its role in baseline imaging and therapy monitoring across several solid tumors (e.g., breast, colorectal, sarcoma) [146]. The therapeutic counterpart, 177Lu-FAP-2286, is under active investigation in the LuMIERE Phase I/II trial, with early data suggesting good tolerability [147,148]. Ongoing studies aim to refine dosing and assess clinical efficacy in advanced tumors. For example, 68Ga-FAP-2286 was employed as an imaging agent in various solid tumors [147], breast, bladder, prostate, colorectal, head and neck, pancreatic, sarcoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and lung cancers [149]. In terms of the safety profiles and clinical trials outcomes of different FAP-targeted radionuclide therapy, Privé et al. have thoroughly reviewed and compared FAPI-04, FAPI-46, FAP-2286, SA.FAP, ND-bisFAPI, PNT6555, TEFAPI-06/07, FAPI-C12/C16, and FSDD [150]. Additionally, in a single center, prospective study (64 patients with 15 types of cancer, 19 patients underwent paired 68Ga-FAP-2286 and 68Ga-FAPI-46 PET/CT) assessing the diagnostic accuracy of 68Ga-FAP-2286 to detect primary and metastatic lesions in patients with various cancer types by comparison with 18F-FDG and 68Ga-FAPI-46, researchers concluded that 68Ga-FAP-2286 and 68Ga-FAPI-46 yielded comparable clinical performance, especially in visceral and bone metastases, the quantitative tumor uptake of 68Ga-FAP-2286 was not inferior to that of 68Ga-FAPI-46 in the lung, liver, peritoneum, or bone. In one metastatic cholangiocarcinoma patient 68Ga-FAP-2286 PET/CT detected more subcutaneous metastases than 68Ga-FAPI-46 did [151]. Palihati et al. have recently reviewed ongoing clinical trials evaluating fibroblast activation protein targeting [152].

Other FAP-Targeting Strategies: Additional approaches have been developed to exploit FAP biology, including cellular therapies, vaccines, and prodrugs. FAP-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have shown promise in preclinical models by remodeling the tumor stroma and enhancing immune responses, with early clinical trials indicating acceptable safety [153,154,155,156,157]. These cells have been studied in human lung cancer xenografts and syngeneic murine pancreatic cancers [158,159]. Another phase I clinical trial studied F19-based CAR-T-cells in malignant pleural mesothelioma patients [155,156]. DNA vaccines against FAP reduced tumor growth and stromal collagen in animal models, improving drug delivery and reducing fibrosis without systemic inflammation [160,161]. They have also been studied in multidrug-resistant murine colon and breast carcinoma [160]. Enzyme-activated prodrugs like FAPα-activated vinblastine prodrug Z-GP-DAVLBH selectively disrupt tumor vasculature and have led to complete tumor regression in resistant models [162]. These innovative approaches highlight the expanding potential of FAP as a versatile therapeutic target.

An overview of representative agents, clinical trial status, and key findings across the major FAP-targeting strategies is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of major approaches FAP-targeting, including small-molecule inhibitors, peptide ligands, monoclonal antibodies and immunoconjugates, CAR-T cells, vaccines, and prodrugs. For each category, representative agents, clinical status, and key findings or limitations are reported.

5.3. Application of FAP-Targeting

Due to its selective expression in CAFs, minimal presence in normal tissue, and critical role in tumor progression, FAP has emerged as a promising clinical target, driving the development of novel strategies for imaging, radioligand therapy, and targeted drug delivery.

Imaging: Given its high expression in CAFs and minimal presence in healthy tissues, FAP has emerged as a promising target for tumor imaging. While CT scans have traditionally been used to visualize masses [167], PET imaging enables non-invasive in vivo visualization of dynamic inflammatory and cellular processes, enabling the visualization of stromal remodeling and therapeutic response across both oncologic and fibrotic contexts [168]. Compared to conventional 18F-FDG PET, long considered a cornerstone of oncologic imaging [167], FAP-targeted tracers offer simplified patient preparation, flexible imaging windows (10 min to 3 h post-injection), favorable biodistribution with low background uptake, and rapid renal clearance with minimal uptake in healthy tissue [112]. However, FAP imaging may also detect activated fibroblasts in non-oncologic conditions, including sites of fibrosis and inflammation [169].

Clinical studies have shown that FAPI PET often outperforms 18FDG PET in desmoplastic tumors [170]. In early-stage lung adenocarcinoma (stage IA), 18F-FAPI-04 PET/CT demonstrated higher SUVmax and tumor-to-background ratios than FDG, with tracer uptake correlating with FAP expression on immunohistochemistry [171]. Moreover, in patients with lung cancer evaluated using both tracers, 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT has been shown to detect a greater number of suspected nodal, pleural, bone, and intracranial metastases compared with 18F-FDG PET/CT [172]. In esophageal cancer, 68Ga-FAPI PET detected all primary cancers and additional nodal metastases missed by CT [173]. Systematic reviews in breast and gastric cancers confirmed that FAPI PET frequently identified more lesions, with superior sensitivity for nodal metastasis and recurrent disease [174,175,176]. Similarly, meta-analyses in hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancers showed FAPI PET outperforms 18F-FDG in nodal, liver, and distant metastasis detection [177]. In sarcomas, 68Ga-FAPI-46 PET demonstrated 96% sensitivity, with uptake correlating with FAP expression and altering staging or management in ~30% of patients [178]. Further studies have highlighted diagnostic advantage of FAPI PET in colorectal [179], ovarian [180], peritoneal [181], and bladder cancers [182], often with significant impacts on clinical decision-making.

The integration of FAP-targeted imaging into clinical practice will require the development of standardized guidelines for patient selection and scan interpretation. While 18F-FDG PET remains the current standard in oncologic imaging, FAP PET offers several advantages in specific clinical contexts. For example, tumors characterized by a dense desmoplastic reaction, such as sarcomas, pancreatic cancers, and lung adenocarcinomas, demonstrate robust FAP expression which results in high tumor-to-background contrast that may surpass the performance of FDG PET [170]. Additionally, FAP PET may outperform FDG in tumors with inherently low metabolic activity, such as gastric and pulmonary adenocarcinomas, where FDG uptake is limited and disease burden may be underestimated [171,183]. FAP imaging can also offer an advantage in anatomical regions with high physiological FDG uptake that may obscure malignancy, such as in hepatic tumors [179].

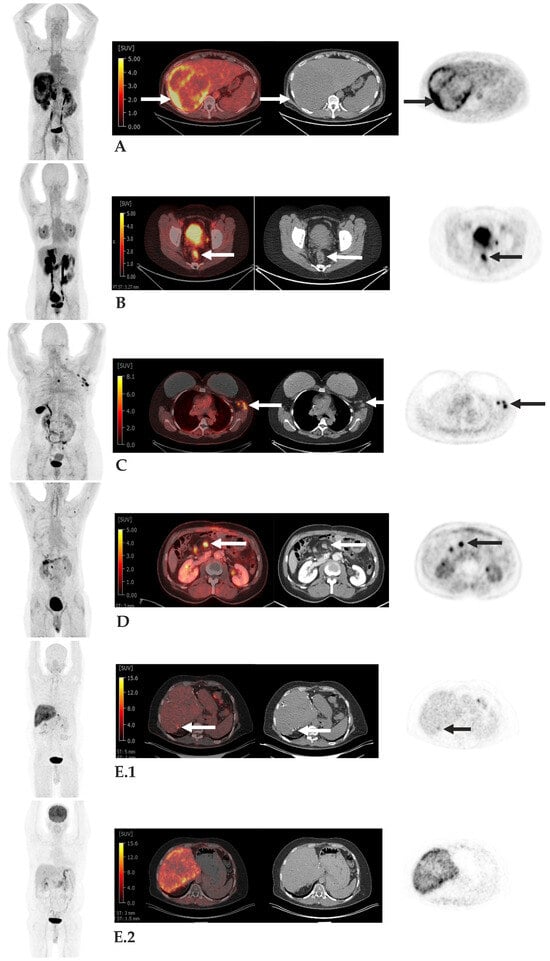

However, careful interpretation of FAP PET is essential due to the potential for off-target uptake in pathologic tissue though non-malignant conditions. Because FAP PET targets activated fibroblasts and fibrotic tissue, uptake may occur in areas of non-malignant fibrosis or inflammation. For instance, in patients with extensive pulmonary fibrosis, inflammatory uptake can confound evaluation for lung cancer. Similarly, FAP PET may demonstrate uptake in regions of physiological tissue remodeling or chronic inflammation, including degenerative joint changes associated with aging, rheumatoid arthritis, myocarditis, and scar tissue [184,185]. Awareness of these potential pitfalls is critical to avoid false-positive interpretations and ensure accurate clinical assessment. Representative examples of clinical FAP PET imaging across tumor types, illustrating the utility and diagnostic contrast of FAP-targeted tracers, are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Examples of FAP PET Imaging. Case (A): 52-year-old man with hepatocellular carcinoma. Large right hepatic mass with intense peripheral FAPI uptake, Standard Value Uptake (SUV) up to 10.0 (arrows), consistent with patients known primary neoplasm. Case (B): 41-year-old man with FAPI-avid rectal cancer, SUV 6.7 (arrows), consistent with patients known primary neoplasm. Case (C): 52-year-old woman with breast cancer with FAPI-avid left axillary nodes, SUV up to 11.1 (arrows), consistent with metastases. Case (D): 55-year-old man with pancreatic adenocarcinoma post Whipple procedure with FAPI-avid central mesenteric node, SUV 9.1, consistent with metastasis. Case (E): 56-year-old man with colon cancer metastatic to liver post hepatic resections with focal FAPI uptake along segment 7 wedge resection (arrow) (Panel (E.1)) without correlate on corresponding FDG PET/CT (Panel (E.2)), subsequently biopsy-proven metastasis. Disclaimer ID: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

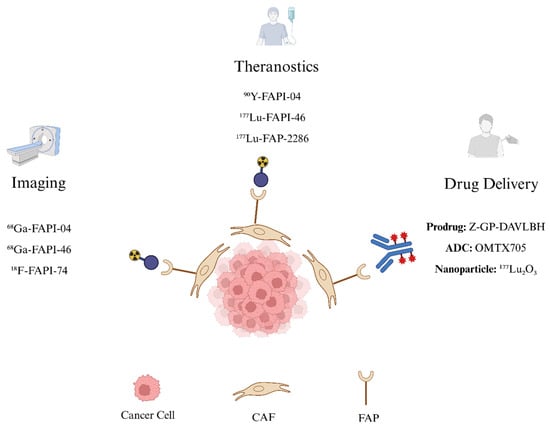

Theranostics: Beyond diagnostic imaging, FAP-targeting agents have been applied in theranostics, pairing PET-based detection with radionuclide therapy. In early studies, 68Ga-FAPI-04 PET/CT was used to localize metastatic breast cancer lesions, followed by therapeutic administration of 90Y-FAPI-04. High uptake was observed in metastatic sites, and the patients experienced pain relief, supporting this therapy [186].

Subsequent early-phase studies have supported the feasibility of radioligand therapy (RLT). In a Phase I trial, 177Lu-FAPI-46 was administered to 18 patients with advanced, treatment-refractory FAP positive cancers, achieving stable disease in two-thirds of cases with minimal radiation to healthy tissues [187]. A separate case series of nine patients with high FAP expressing advanced solid tumors treated with 90Y-FAPI-46 reported favorable tumor uptake and disease control in ~50% of patients, although grade 3–4 hematologic toxicity occurred in four cases [188]. In another first-in-human study in patients with advanced adenocarcinoma (pancreatic, breast, rectal, and ovarian), 177Lu-FAP-2286 showed prolonged tumor retention and high tumor absorbed doses, with low systemic exposure and manageable grade 3 adverse events [189].

FAP-targeting RLT has also been explored in radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer. Treatment with 177Lu-DOTAGA.(SA.FAPi)2 in 15 patients who had progressed on standard therapies and demonstrated high FAP uptake on 68Ga imaging, reduced serum thyroglobulin and improved pain and performance scores, without significant hematologic, renal, or hepatic toxicity [190]. Encouraged by these findings, later-phase clinical trials are underway. The LuMIERE Phase I/II trial is currently evaluating 177Lu-FAP-2286 in advanced solid tumors, using paired 68Ga-FAP-2286 imaging for patient selection and dosimetry [147].

Together, these studies highlight the early but growing evidence that FAP-targeted theranostics may offer a safe, tolerable, and effective therapeutic option across multiple tumor types, particularly in settings where conventional treatments have failed.

Drug Delivery: Beyond theranostic applications, FAP-targeting has been explored in a range of drug delivery platforms, including prodrugs, antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), and nanoparticle systems. These strategies aim to exploit the high expression of FAP in CAFs to achieve selective intratumoral drug activation or accumulation while minimizing systemic toxicity.

FAP-activated prodrugs remain inert in circulation but are enzymatically converted into active cytotoxic agents within the TME. In a 2014 study, the FAP-activated prodrug ERGETGP-S12ADT effectively suppressed tumor growth in mouse xenograft models of human breast and prostate cancers with efficacy comparable to docetaxel but markedly lower systemic toxicity [191]. Additional candidates have shown similar preclinical promise across tumor types, though none have yet reached clinical evaluation.

FAP-directed ADCs combine a monoclonal antibody specific to FAP with a potent cytotoxic payload. OMTX705, a humanized anti-FAP ADC, induced complete tumor growth inhibition and durable regression in patient-derived xenograft models, both as monotherapy and in combination with chemotherapy [192]. While early studies yielded positive results, translation into clinical trials remains pending.

Nanoparticle-based drug delivery platforms represent an emerging strategy for FAP-targeted therapy. In a 2020 study, lipid–albumin nanoparticles engineered to release paclitaxel in response to FAPα demonstrated enhanced tumor penetration and robust tumor regression in a pancreatic cancer mouse model, with minimal systemic toxicity [193].

Together, these approaches highlight the versatility of FAP as a tumor-specific target. While further clinical trials are necessary, these platforms offer a promising direction for expanding FAP-targeted interventions in oncology. A schematic overview of current FAP-targeting applications, spanning diagnostic imaging, radioligand therapy, and drug delivery platforms, is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

FAP-targeting Schematic. FAP expressed on CAFs is a promising oncologic target. FAP-targeting tracers labeled with positron-emitting isotopes such as 68Ga-FAPI-04, 68Ga-FAPI-46, and 18F-FAPI-74 enable diagnostic PET imaging, while FAP-targeting tracers labeled with β-emitting radionuclides such as 90Y-FAPI-04, 177Lu-FAPI-46, and 177Lu-FAP-2286 deliver targeted radioligand therapy. Beyond radiopharmaceuticals, FAP-targeting strategies also include drug delivery approaches such as prodrugs (Z-GP-DAVLBH), antibody–drug conjugates (OMTX705), and nanoparticles (e.g., 177Lu2O3). Figure created in BioRender.

6. Targeting Other CAF Markers

While FAP remains the most studied CAF marker, additional fibroblast-associated molecules such as PDGFR, LRRC15, GPR77, and CD105 have emerged as promising therapeutic targets. These markers define distinct CAF subsets with specialized roles in tumor growth, immune evasion, and therapy resistance.

Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor (PDGFR): PDGFRα/β are tyrosine kinase receptors that regulate fibroblast proliferation via PI3K/Akt, MAPK, and ERK pathways [194]. Aberrant PDGFR signaling contributes to tumor progression, metastasis, and fibrosis, making it a useful therapeutic target for tyrosine kinase inhibitors and degradation agents [195]. A spatial transcriptomics study identified a novel PDGFRα+ITGA11+ CAF subset enriched in bladder cancer and associated with lymphovascular invasion and nodal metastasis [196]. Separately, a mechanistic study using the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data and breast cancer models demonstrated that PDGFRβ, along with caveolin-1 (Cav-1), promotes autophagy in CAFs through the mTOR/FIP200/ATG13 pathway and enhances tumor invasiveness via HIF-1α/MCT4/MCT1 signaling [197].

Leucine-Rich Repeat-Containing Protein 15 (LRRC15): LRRC15 is upregulated in CAFs from breast, lung, pancreatic, and head and neck cancers. It fosters tumor progression, metastasis, and resistance to immunotherapy [198]. In ovarian cancer models, LRRC15 expression inhibited anoikis and promoted metastasis, which was suppressed by the LRRC15-targeted ADC ABBV-085 [199] Single-cell RNA sequencing of over 600 patient samples revealed that tumors with abundant LRRC15+ CAFs demonstrated poor response to anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy, highlighting their immunosuppressive role [46]. Mechanistic studies in pancreatic cancer and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) further implicated LRRC15 in fibroblast differentiation via TGFβR2 signaling and invasion through Wnt/β-catenin activation [67,200]

C5a Receptor-Like 2 (GPR77): GPR77, often co-expressed with CD10, defines a CAF subset associated with cancer stem cell survival, chemoresistance, and tumorigenesis. GPR77 maintains NF-κB signaling through p65 phosphorylation and acetylation, sustaining an inflammatory CAF phenotype [69]. In gastric cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy and gastrectomy, high post-treatment GPR77 expression correlated with worse tumor regression grade (TRG), indicating its potential as a predictive biomarker for poor therapeutic response [201].

Endoglin (CD105): CD105 is a TGF-β co-receptor enriched in CAFs from breast, pancreatic, and cervical cancers. In pancreatic tumors, CD105+ CAFs secrete exosomes enriched in circAMPK1, which enhanced malignant progression [202]. In breast cancer, high CD105 expression in peri-epithelial CD105 expression, particularly in older women and BRCA1 carriers, correlated with increased risk of metastasis, notably to bone [199,203]. In cervical cancer, CD105+ stromal fibroblasts were linked to high VEGF-A expression, suggesting roles in tumor angiogenesis and vascular remodeling [204].

Table 3 summarizes key therapeutic strategies targeting non-FAP CAF markers, including PDGFR, LRRC15, GPR77, and CD105. For each marker, representative agents, mechanisms of action, relevant preclinical and clinical findings, and associated challenges are outlined.

Table 3.

Summary of Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Non-FAP CAF Markers. This table outlines therapeutic agents directed at non-FAP CAF markers such as PDGFR, LRRC15, GPR77, and CD105. For each target, it highlights representative drugs, mechanisms of action, key preclinical or clinical findings, and current challenges. The comparison emphasizes the benefits and limitations of these approaches and underscores the need for marker-specific, selective therapies.

7. Success Comparisons and Emerging Subtype-Specific Strategies

Theranostic approaches targeting CAFs, particularly FAP-positive subsets, have shown encouraging results but also revealed important limitations. For example, FAP-2286 has demonstrated strong tumor uptake and retention in both preclinical models and early peptide-targeted radionuclide therapy trials, yet variable patient responses highlight the functional heterogeneity of CAF populations [189,221]. Similarly, spatial single-cell studies in colorectal cancer revealed that enrichment of FAP+ fibroblasts and SPP1+ macrophages correlate with reduced benefit from anti-PD-L1 therapy, underscoring the immunosuppressive crosstalk between stromal and myeloid compartments [222]. These findings illustrate both the therapeutic promise and biological complexity of targeting FAP.

Clinical setbacks such as the failure of the monoclonal antibody sibrotuzumab in Phase II trials for metastatic colorectal cancer underscore the need to stratify patients based on CAF subtype. Incomplete enzymatic inhibition and intertumoral CAF heterogeneity likely contributed to its limited therapeutic benefits [223]. Emerging subtype-specific approaches also extend to non-FAP markers. For instance, LRRC15-targeting ADCs demonstrated enhanced efficacy in osteosarcoma cell lines with high LRRC15 expression. Notably, LRRC15-low cells could be sensitized to ADC therapy through TGFβ-induced re-expression, offering a strategy for overcoming resistance via tumor microenvironment modulation [93].

GPR77+ CAFs, driven by CCL18 signaling from TAMs, promote stemness and chemoresistance in breast cancer, but this effect can be reversed with anti-CCL18 therapy [215]. CD105, a TGF-β co-receptor, has been extensively studied in angiogenesis, particularly in renal cell carcinoma (RCC). TRC105, a monoclonal antibody targeting CD105, showed additive anti-angiogenic effects when combined with VEGF inhibitors in preclinical models. These promising results led to early-phase clinical trials evaluating this combinatory strategy [224]. Finally, beyond CAF-specific roles, PDGFR signaling has been implicated in both tumor stroma and bone remodeling, suggesting broader therapeutic opportunities [225].

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Over the past decade CAFs have evolved from being viewed as passive structural elements to being recognized as dynamic modulators of tumor progression, immune suppression, and therapeutic resistance. This conceptual shift has profound implications for how we diagnose, monitor, and treat solid tumors. By integrating CAF biology into the broader framework of tumor biology, the stromal compartment is now seen not only as a therapeutic target but also as a diagnostic and prognostic resource.

The next decade of fibroblast-directed therapies is expected to rely on increased precision, integrating multi-marker and subtype-specific strategies rather than relying solely on single targets such as FAP. Preclinical and translational studies increasingly suggest that identifying distinct CAF subsets, including inflammatory (GPR77+), matrix-remodeling (LRRC15+), angiogenic (CD105+), and motile (FSP1+) fibroblasts, could enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects. By distinguishing tumor-promoting CAFs from neutral or tumor-restraining populations, these approaches promise a more refined and clinically sustainable way of modulating the stroma.

This evolution is already reflected in the clinical pipeline. The LuMIERE trial, with an estimated conclusion date of 2028, is evaluating 177Lu-FAP-2286 in patients with advanced solid tumors, combining FAP-PET imaging for patient selection with radioligand therapy to measure safety, dosimetry, and early efficacy [147]. A novel FAP-activated prodrug of doxorubicin, named AVA6000, has demonstrated selective activation within the TME, which significantly reduces systemic toxicity while maintaining antitumor efficacy in FAP-rich models, and is currently in phase I clinical trials with an expected completion date in 2026 [226,227]. On the non-FAP front, the ABBV-085 tested an LRRC15-directed antibody–drug conjugate in sarcomas and other stromal-rich cancers, with endpoints including pharmacokinetics, safety, and preliminary response. The trial, which concluded in 2021, demonstrated ABBV-085 to be well tolerated at a biweekly dose of 3.6 mg/kg and showed early signs of efficacy, particularly in patients with osteosarcoma and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma [211]. Meanwhile, newer FAP-targeted bispecific antibodies and imaging probes are entering early-phase trials to enable dynamic stromal profiling and patient stratification. Complementing these therapeutic developments, AI-enabled multimodal imaging and radiomics approaches are being explored to characterize stromal features, monitor therapy-induced remodeling, and predict immune related adverse events, with the goal of enabling real-time, response-adaptive treatment strategies [228].

The outlook for CAF targeting presents an exciting field. As this review shows, multiple clinical trials are in progress and may directly impact clinical practice. Growing knowledge of the subtypes of CAFs, as well as their intricate role in cancer biology, has unlocked the potential for more targeted approaches to therapies and diagnostics which have the potential to enter the clinic in the 2030s. Looking ahead, stromal targeting is expected to integrate into routine oncology practice for imaging and therapy. Advances in stromal imaging and spatial profiling are likely to support patient stratification and adaptive therapy monitoring in real time. As clinical trials indicate, CAF-directed interventions may increasingly be combined with immunotherapies, chemotherapies, and radiotherapies to break physical and immunologic barriers, thereby improving drug penetration, immune infiltration, and survival outcomes. Over the next decade, the stroma may shift from being seen as an obstacle to being recognized as a dynamic, targetable, and reversible element of solid tumor biology, central to precision oncology.

Author Contributions

Project administration, K.M.C.; Writing—original draft preparation, N.N., A.K., M.P., Y.P. and A.O.G.; Writing—review and editing, N.N., A.K., M.P., Y.P., A.O.G., K.M.C. and J.P.D.; Supervision, K.M.C. and J.P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT-4o for the purpose of grammar correction. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

ADC, antibody–drug conjugate; α-SMA, alpha-smooth muscle actin; apCAF, antigen-presenting CAF; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T cell; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; CD, cluster of differentiation; CXCL, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand; DOTA, 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid; ECM, extracellular matrix; EGF, epidermal growth factor; FAP, fibroblast activation protein; FASL, Fas ligand; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; FSP1, fibroblast-specific protein 1; GPR77, G-protein coupled receptor 77; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; iCAF, inflammatory CAF; IL, interleukin; JAK-STAT3, Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; LRRC15, leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 15; mCAF, matrix-remodeling CAF; MHC-II, major histocompatibility complex class II; myCAF, myofibroblastic CAF; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PD-1/PD-L1/PD-L2, programmed death-1/ligands 1 and 2; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; PDPN, podoplanin; PET, positron emission tomography; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; RA, retinoic acid; RLT, radioligand therapy; TAMs, tumor-associated macrophages; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; TME, tumor microenvironment; TNC, tenascin-C; Tregs, regulatory T cells; VCAF, vascular CAF; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VIM, vimentin.

References

- Bussard, K.M.; Mutkus, L.; Stumpf, K.; Gomez-Manzano, C.; Marini, F.C. Tumor-associated stromal cells as key contributors to the tumor microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res. 2016, 18, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahai, E.; Astsaturov, I.; Cukierman, E.; DeNardo, D.G.; Egeblad, M.; Evans, R.M.; Fearon, D.; Greten, F.R.; Hingorani, S.R.; Hunter, T. A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of cancer: New dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansems, M.; Span, P.N. The tumor microenvironment and radiotherapy response; a central role for cancer-associated fibroblasts. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 22, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; Zeisberg, M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, M. Cancer associated fibroblasts in cancer development and therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; McAndrews, K.M.; Kalluri, R. Clinical and therapeutic relevance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.M.; Simon, M.C. The tumor microenvironment. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R921–R925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, G.; Khavaran, A.; Gasull, A.D.; Cahueau, J.; Diebold, M.; Chhatbar, C.; Friedrich, M.; Heiland, D.H.; Sankowski, R. Transcriptome Analysis Identifies Accumulation of Natural Killer Cells with Enhanced Lymphotoxin-β Expression during Glioblastoma Progression. Cancers 2022, 14, 4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Kieffer, Y.; Scholer-Dahirel, A.; Pelon, F.; Bourachot, B.; Cardon, M.; Sirven, P.; Magagna, I.; Fuhrmann, L.; Bernard, C. Fibroblast heterogeneity and immunosuppressive environment in human breast cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 463–479.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elyada, E.; Bolisetty, M.; Laise, P.; Flynn, W.F.; Courtois, E.T.; Burkhart, R.A.; Teinor, J.A.; Belleau, P.; Biffi, G.; Lucito, M.S. Cross-species single-cell analysis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reveals antigen-presenting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 1102–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öhlund, D.; Elyada, E.; Tuveson, D. Fibroblast heterogeneity in the cancer wound. J. Exp. Med. 2014, 211, 1503–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, R.S.; Kanugula, S.S.; Sudhir, S.; Pereira, M.P.; Jain, S.; Aghi, M.K. The role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumor progression. Cancers 2021, 13, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Vega, V.; Rojas, B.V.; Torres, W.D. Immunohistochemical analysis of cancer-associated fibroblasts and podoplanin in head and neck cancer. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2020, 25, e268–e276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Xu, J. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: A versatile mediator in tumor progression, metastasis, and targeted therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2024, 43, 1095–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhlund, D.; Handly-Santana, A.; Biffi, G.; Elyada, E.; Almeida, A.S.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; Corbo, V.; Oni, T.E.; Hearn, S.A.; Lee, E.J. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, N.A.; Neilson, E.G.; Moses, H.L. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature 2004, 432, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollila, S.; Domènech-Moreno, E.; Laajanen, K.; Wong, I.P.; Tripathi, S.; Pentinmikko, N.; Gao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Niemelä, E.H.; Wang, T.C.; et al. Stromal Lkb1 deficiency leads to gastrointestinal tumorigenesis involving the IL-11-JAK/STAT3 pathway. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffini, M.V.; Soto, A.M.; Calabro, J.M.; Ucci, A.A.; Sonnenschein, C. The stroma as a crucial target in rat mammary gland carcinogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Nan, F. Breast cancer stromal fibroblasts promote the generation of CD44+CD24- cells through SDF-1/CXCR4 interaction. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 29, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, K.T.; Adema, G.J.; Bussink, J.; Ansems, M. Cancer-associated fibroblasts, tumor and radiotherapy: Interactions in the tumor micro-environment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, T.; Mizushima, H.; Chinen, I.; Moribe, H.; Yagi, S.; Hoffman, R.M.; Kimura, T.; Yoshino, K.; Ueda, Y.; Enomoto, T. HB-EGF and PDGF mediate reciprocal interactions of carcinoma cells with cancer-associated fibroblasts to support progression of uterine cervical cancers. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 6633–6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orimo, A.; Gupta, P.B.; Sgroi, D.C.; Arenzana-Seisdedos, F.; Delaunay, T.; Naeem, R.; Carey, V.J.; Richardson, A.L.; Weinberg, R.A. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell 2005, 121, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labernadie, A.; Kato, T.; Brugués, A.; Serra-Picamal, X.; Derzsi, S.; Arwert, E.; Weston, A.; González-Tarragó, V.; Elosegui-Artola, A.; Albertazzi, L.; et al. A mechanically active heterotypic E-cadherin/N-cadherin adhesion enables fibroblasts to drive cancer cell invasion. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado, B.A.; Bushnell, G.G.; Rao, S.S.; Jeruss, J.S.; Shea, L.D. Engineering the pre-metastatic niche. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 0077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhome, R.; Goh, R.W.; Bullock, M.D.; Pillar, N.; Thirdborough, S.M.; Mellone, M.; Mirnezami, R.; Galea, D.; Veselkov, K.; Gu, Q.; et al. Exosomal microRNAs derived from colorectal cancer-associated fibroblasts: Role in driving cancer progression. Aging 2017, 9, 2666–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzese, F.; Hägglöf, C.; Leone, A.; Sjöberg, E.; Roca, M.S.; Kiflemariam, S.; Sjöblom, T.; Hammarsten, P.; Egevad, L.; Bergh, A.; et al. Local and systemic protumorigenic effects of cancer-associated fibroblast-derived GDF15. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 3408–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteran, L.; Erez, N. The dark side of fibroblasts: Cancer-associated fibroblasts as mediators of immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauriello, D.V.F.; Palomo-Ponce, S.; Stork, D.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Badia-Ramentol, J.; Iglesias, M.; Sevillano, M.; Ibiza, S.; Cañellas, A.; Hernando-Momblona, X.; et al. TGFβ drives immune evasion in genetically reconstituted colon cancer metastasis. Nature 2018, 554, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feig, C.; Jones, J.O.; Kraman, M.; Wells, R.J.; Deonarine, A.; Chan, D.S.; Connell, C.M.; Roberts, E.W.; Zhao, Q.; Caballero, O.L.; et al. Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20212–20217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, P.; Mielgo, A. Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Mediated Inhibition of CD8+ Cytotoxic T Cell Accumulation in Tumours: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers 2020, 12, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakins, M.A.; Ghorani, E.; Munir, H.; Martins, C.P.; Shields, J.D. Cancer-associated fibroblasts induce antigen-specific deletion of CD8+ T Cells to protect tumour cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearon, D.T. The carcinoma-associated fibroblast expressing fibroblast activation protein and escape from immune surveillance. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esebanmen, G.E.; Langridge, W.H.R. The role of TGF-beta signaling in dendritic cell tolerance. Immunol. Res. 2017, 65, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskov, H.; Orhan, A.; Gaggar, S.; Gögenur, I. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Cancer and Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 668731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Qian, Y.; Ye, Z.; Chen, H.; Xie, H.; Zhou, L.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, S. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote M2 polarization of macrophages in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, H.; Jones, J.O.; Janowitz, T.; Hoffmann, M.; Euler, M.; Martins, C.P.; Welsh, S.J.; Shields, J.D. Stromal-driven and Amyloid β-dependent induction of neutrophil extracellular traps modulates tumor growth. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, C.; Qin, Z. Metabolic reprogramming of cancer-associated fibroblasts and its effect on cancer cell reprogramming. Theranostics 2021, 11, 8322–8336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukourakis, M.I.; Giatromanolaki, A.; Harris, A.L.; Sivridis, E. Comparison of metabolic pathways between cancer cells and stromal cells in colorectal carcinomas: A metabolic survival role for tumor-associated stroma. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.M.; Biancur, D.E.; Wang, X.; Halbrook, C.J.; Sherman, M.H.; Zhang, L.; Kremer, D.; Hwang, R.F.; Witkiewicz, A.K.; Ying, H.; et al. Pancreatic stellate cells support tumour metabolism through autophagic alanine secretion. Nature 2016, 536, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Ding, L.; Zhang, D.; Shi, G.; Xu, Q.; Shen, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Hou, Y. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts promote the stemness and chemoresistance of colorectal cancer by transferring exosomal lncRNA H19. Theranostics 2018, 8, 3932–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shintani, Y.; Fujiwara, A.; Kimura, T.; Kawamura, T.; Funaki, S.; Minami, M.; Okumura, M. IL-6 Secreted from Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Mediates Chemoresistance in NSCLC by Increasing Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Signaling. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016, 11, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olive, K.P.; Jacobetz, M.A.; Davidson, C.J.; Gopinathan, A.; McIntyre, D.; Honess, D.; Madhu, B.; Goldgraben, M.A.; Caldwell, M.E.; Allard, D.; et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science 2009, 324, 1457–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, V.; Semaan, A.; Huang, J.; San Lucas, F.A.; Mulu, F.C.; Stephens, B.M.; Guerrero, P.A.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Kamyabi, N. Single-cell transcriptomics of pancreatic cancer precursors demonstrates epithelial and microenvironmental heterogeneity as an early event in neoplastic progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2194–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, C.X.; Müller, S.; Keerthivasan, S.; Koeppen, H.; Hung, J.; Gierke, S.; Breart, B.; Foreman, O.; Bainbridge, T.W.; Castiglioni, A. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals stromal evolution into LRRC15+ myofibroblasts as a determinant of patient response to cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 232–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Sun, B.-F.; Chen, C.-Y.; Zhou, J.-Y.; Chen, Y.-S.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Huang, D.; Jiang, J.; Cui, G.-S. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intra-tumoral heterogeneity and malignant progression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wu, C.; Mao, H.; Gu, H.; Dong, H.; Yan, J.; Qi, Z.; Yuan, L.; Dong, Q.; Long, J. Subpopulations of cancer-associated fibroblasts link the prognosis and metabolic features of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, B.C.; Pentcheva-Hoang, T.; Carstens, J.L.; Zheng, X.; Wu, C.-C.; Simpson, T.R.; Laklai, H.; Sugimoto, H.; Kahlert, C.; Novitskiy, S.V.; et al. Depletion of Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts and Fibrosis Induces Immunosuppression and Accelerates Pancreas Cancer with Reduced Survival. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, A.D.; Oberstein, P.E.; Thomas, D.H.; Mirek, E.T.; Palermo, C.F.; Sastra, S.A.; Dekleva, E.N.; Saunders, T.; Becerra, C.P.; Tattersall, I.W.; et al. Stromal Elements Act to Restrain, Rather Than Support, Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwaier, A.; Zhu, S.-X.; Tian, X.; Xu, W.-H.; Wang, Y.; Palihati, M.; Wang, W.-Y.; Shi, G.-H.; Qu, Y.-Y.; Zhang, H.-L.; et al. Large-Scale Proteomics Data Reveal Integrated Prognosis-Related Protein Signatures and Role of SMAD4 and RAD50 in Prognosis and Immune Infiltrations of Prostate Cancer Microenvironment. Phenomics 2022, 2, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Anwaier, A.; Ma, C.; Liu, W.; Tian, X.; Palihati, M.; Hu, X.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ye, D. Multi-omics reveals novel prognostic implication of SRC protein expression in bladder cancer and its correlation with immunotherapy response. Ann. Med. 2021, 53, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurmik, M.; Ullmann, P.; Rodriguez, F.; Haan, S.; Letellier, E. In search of definitions: Cancer-associated fibroblasts and their markers. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louault, K.; Li, R.-R.; DeClerck, Y.A. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: Understanding Their Heterogeneity. Cancers 2020, 12, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, J.; Qian, H.; Zhuang, Q. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: From basic science to anticancer therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoschek, M.; Oskolkov, N.; Bocci, M.; Lövrot, J.; Larsson, C.; Sommarin, M.; Madsen, C.D.; Lindgren, D.; Pekar, G.; Karlsson, G.; et al. Spatially and functionally distinct subclasses of breast cancer-associated fibroblasts revealed by single cell RNA sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, I.A.; Zakuan, N.; Billet, F.; Desmoulière, A. The myofibroblast, a key cell in normal and pathological tissue repair. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamson, E.J.; Keane, F.M.; Tholen, S.; Schilling, O.; Gorrell, M.D. Understanding fibroblast activation protein (FAP): Substrates, activities, expression and targeting for cancer therapy. Proteom.—Clin. Appl. 2014, 8, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, J.; Pang, Y.; Fu, K.; Shang, Q.; Wu, H.; Sun, L.; Lin, Q.; Chen, H. Fibroblast activation protein-based theranostics in cancer research: A state-of-the-art review. Theranostics 2022, 12, 1557–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidrak, M.M.A.; De Feo, M.S.; Corica, F.; Gorica, J.; Conte, M.; Filippi, L.; Schillaci, O.; De Vincentis, G.; Frantellizzi, V. Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitor (FAPI)-Based Theranostics—Where We Are at and Where We Are Heading: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, A.A.; Weiner, L.M. The role of fibroblast activation protein in health and malignancy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39, 783–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahounová, Z.; Kurfürstová, D.; Bouchal, J.; Kharaishvili, G.; Navrátil, J.; Remšík, J.; Šimečková, Š.; Študent, V.; Kozubík, A.; Souček, K. The fibroblast surface markers FAP, anti-fibroblast, and FSP are expressed by cells of epithelial origin and may be altered during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cytom. Part A 2018, 93, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-F.; Dong, M.; Pan, Y.-H.; Chen, J.-N.; Huang, X.-Q.; Jin, Y.; Shao, C.-K. Expression pattern of cancer-associated fibroblast and its clinical relevance in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 2017, 65, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strutz, F.; Okada, H.; Lo, C.W.; Danoff, T.; Carone, R.L.; Tomaszewski, J.E.; Neilson, E.G. Identification and characterization of a fibroblast marker: FSP1. J. Cell Biol. 1995, 130, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venning, F.A.; Zornhagen, K.W.; Wullkopf, L.; Sjölund, J.; Rodriguez-Cupello, C.; Kjellman, P.; Morsing, M.; Hajkarim, M.C.; Won, K.J.; Erler, J.T.; et al. Deciphering the temporal heterogeneity of cancer-associated fibroblast subpopulations in breast cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caligiuri, G.; Tuveson, D.A. Activated fibroblasts in cancer: Perspectives and challenges. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurty, A.T.; Shyer, J.A.; Thai, M.; Gandham, V.; Buechler, M.B.; Yang, Y.A.; Pradhan, R.N.; Wang, A.W.; Sanchez, P.L.; Qu, Y.; et al. LRRC15+ myofibroblasts dictate the stromal setpoint to suppress tumour immunity. Nature 2022, 611, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, J.W.; Tanlimco, S.G.; Hickson, J.; Fox, M.; Sho, M.; Durkin, L.; Uziel, T.; Powers, R.; Foster, K.; McGonigal, T.; et al. LRRC15 Is a Novel Mesenchymal Protein and Stromal Target for Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 4059–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Chen, J.; Yao, H.; Liu, J.; Yu, S.; Lao, L.; Wang, M.; Luo, M.; Xing, Y.; Chen, F.; et al. CD10(+)GPR77(+) Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Promote Cancer Formation and Chemoresistance by Sustaining Cancer Stemness. Cell 2018, 172, 841–856.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wei, R.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Liu, X. Antigen-presenting cancer associated fibroblasts enhance antitumor immunity and predict immunotherapy response. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Gao, M.; Liao, S.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, G.; Zhou, Y. Role and mechanism of CD90+ fibroblasts in inflammatory diseases and malignant tumors. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieffer, Y.; Hocine, H.R.; Gentric, G.; Pelon, F.; Bernard, C.; Bourachot, B.; Lameiras, S.; Albergante, L.; Bonneau, C.; Guyard, A.; et al. Single-Cell Analysis Reveals Fibroblast Clusters Linked to Immunotherapy Resistance in Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1330–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, W.-D.; Yang, Z.-T.; Cui, C.-A.; Cui, Y.; Fang, L.-Y.; Xuan, Y.-H. Tenascin-C is a potential cancer-associated fibroblasts marker and predicts poor prognosis in prostate cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 486, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuzillet, C.; Nicolle, R.; Raffenne, J.; Tijeras-Raballand, A.; Brunel, A.; Astorgues-Xerri, L.; Vacher, S.; Arbateraz, F.; Fanjul, M.; Hilmi, M.; et al. Periostin- and podoplanin-positive cancer-associated fibroblast subtypes cooperate to shape the inflamed tumor microenvironment in aggressive pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Pathol. 2022, 258, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busek, P.; Mateu, R.; Zubal, M.; Kotackova, L.; Sedo, A. Targeting fibroblast activation protein in cancer—Prospects and caveats. Front. Biosci. 2018, 23, 1933–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Meng, Q.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Liang, C.; Hua, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, X.; et al. Signaling pathways in cancer-associated fibroblasts: Recent advances and future perspectives. Cancer Commun. 2023, 43, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokhanbigli, S.; Haghi, M.; Dua, K.; Oliver, B.G.G. Cancer-associated fibroblast cell surface markers as potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets in lung cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2024, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, G.; Wang, X.; Ou, H.; Guo, D. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: Dual roles from senescence sentinels to death regulators and new dimensions in therapy. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1635771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Song, E. Turning foes to friends: Targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calon, A.; Lonardo, E.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Espinet, E.; Hernando-Momblona, X.; Iglesias, M.; Sevillano, M.; Palomo-Ponce, S.; Tauriello, D.V.; Byrom, D.; et al. Stromal gene expression defines poor-prognosis subtypes in colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Barraza, J.; Francescone, R.; Luong, T.; Shah, N.; Madhani, R.; Cukierman, G.; Dulaimi, E.; Devarajan, K.; Egleston, B.L.; Nicolas, E.; et al. Matrix-regulated integrin α(v)β(5) maintains α(5)β(1)-dependent desmoplastic traits prognostic of neoplastic recurrence. Elife 2017, 6, e20600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.O.; Feng, Y.H.; Su, W.C.; Oh, D.Y.; Keam, B.; Shen, L.; Kim, S.W.; Liu, X.; Liao, H.; Qing, M.; et al. Erdafitinib in Asian patients with advanced solid tumors: An open-label, single-arm, phase IIa trial. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loriot, Y.; Matsubara, N.; Park, S.H.; Huddart, R.A.; Burgess, E.F.; Houede, N.; Banek, S.; Guadalupi, V.; Ku, J.H.; Valderrama, B.P.; et al. Erdafitinib or Chemotherapy in Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1961–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoda, A.M.; Simovic, D.; Karin, V.; Kardum, V.; Vranic, S.; Serman, L. The role of the Hedgehog signaling pathway in cancer: A comprehensive review. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2018, 18, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra Jena, B.; Sarkar, S.; Rout, L.; Mandal, M. The transformation of cancer-associated fibroblasts: Current perspectives on the role of TGF-β in CAF mediated tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. Cancer Lett. 2021, 520, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Quazi, S.; Arora, S.; Osellame, L.D.; Burvenich, I.J.; Janes, P.W.; Scott, A.M. Cancer-associated fibroblasts as therapeutic targets for cancer: Advances, challenges, and future prospects. J. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 32, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarratana, A.O.; Prendergast, C.M.; Salvatore, M.M.; Capaccione, K.M. TGF-β signaling: Critical nexus of fibrogenesis and cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, H.A. Avutometinib and Defactinib: First Approval. Drugs 2025, 85, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.A.; Walton, M.I.; Grimshaw, K.M.; Te Poele, R.H.; Eve, P.D.; Valenti, M.R.; de Haven Brandon, A.K.; Martins, V.; Zetterlund, A.; Heaton, S.P.; et al. Correction: AT13148 Is a Novel, Oral Multi-AGC Kinase Inhibitor with Potent Pharmacodynamic and Antitumor Activity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Khan, F.; Upadhyay, T.K.; Seungjoon, M.; Park, M.N.; Kim, B. New insights about the PDGF/PDGFR signaling pathway as a promising target to develop cancer therapeutic strategies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fatatry, B.M.; El-Haggar, S.M.; Ibrahim, O.M.; Shalaby, K.H. Niclosamide from an anthelmintic drug to a promising adjuvant therapy for diabetic kidney disease: Randomized clinical trial. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunetto, E.; De Monte, L.; Balzano, G.; Camisa, B.; Laino, V.; Riba, M.; Heltai, S.; Bianchi, M.; Bordignon, C.; Falconi, M.; et al. The IL-1/IL-1 receptor axis and tumor cell released inflammasome adaptor ASC are key regulators of TSLP secretion by cancer associated fibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slemmons, K.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Meltzer, P.; Purcell, J.W.; Helman, L.J. LRRC15 antibody-drug conjugates show promise as osteosarcoma therapeutics in preclinical studies. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2021, 68, e28771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Tempero, M.A.; Sigal, D.; Oh, D.Y.; Fazio, N.; Macarulla, T.; Hitre, E.; Hammel, P.; Hendifar, A.E.; Bates, S.E.; et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of Pegvorhyaluronidase Alfa with Nab-Paclitaxel Plus Gemcitabine for Patients with Hyaluronan-High Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3185–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, R.; Liew, S.H.; Connelly, A.A.; Yee, N.S.; Deb, S.; Kumar, B.; Vargas, A.C.; O’Toole, S.A.; Parslow, A.C.; Poh, A.; et al. The angiotensin receptor blocker, Losartan, inhibits mammary tumor development and progression to invasive carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 18640–18656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losartan and Nivolumab in Combination with Combination Chemotherapy and SBRT in Treating Patients with Localized Pancreatic Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/research/participate/clinical-trials-search/v?id=NCT03563248 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, W.; Hu, X.; Wang, D.; Tang, D. Metabolic reprogramming of cancer-associated fibroblast in the tumor microenvironment: From basics to clinic. Clin. Med. Insights Oncol. 2024, 18, 11795549241287058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, F.; Semba, T.; Yasuda-Yoshihara, N.; Yamada, K.; Nishimura, A.; Yamasaki, J.; Nagano, O.; Yasuda, T.; Yonemura, A.; Tong, Y.; et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts reuse cancer-derived lactate to maintain a fibrotic and immunosuppressive microenvironment in pancreatic cancer. JCI Insight 2023, 8, 163022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Zhou, F.; Wu, X. Lactate-Mediated Crosstalk Between Tumor Cells and Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Huang, X.; Yang, M.; Zhou, S.; Li, Z.; Fang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Hou, H. Lactate in the tumor microenvironment: A rising star for targeted tumor therapy. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1113739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, M.; Ishimoto, T. Targeting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: Eliminate or Reprogram? Cancer Sci. 2025, 116, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Fu, D.; Cai, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, N.; Xu, Z. Metabolic Reprogramming of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: Transforming Tumor Accomplices into Immunotherapeutic Allies. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2418240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.R.; Colston, K.W.; Lofts, F.J.; Cunningham, D.; Anthoney, D.A.; Gogas, H.; de Bono, J.S.; Hamberg, K.J.; Skov, T.; Mansi, J.L. A phase II trial of the vitamin D analogue Seocalcitol (EB1089) in patients with inoperable pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2002, 86, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiba, T.; Morikawa, T.; Odaka, M.; Nakada, T.; Kamiya, N.; Yamashita, M.; Yabe, M.; Inagaki, T.; Asano, H.; Mori, S.; et al. Vitamin D Supplementation and Survival of Patients with Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 4089–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, K.; Nimeiri, H.S.; McCleary, N.J.; Abrams, T.A.; Yurgelun, M.B.; Cleary, J.M.; Rubinson, D.A.; Schrag, D.; Miksad, R.; Bullock, A.J.; et al. Effect of High-Dose vs Standard-Dose Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Progression-Free Survival Among Patients with Advanced or Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The SUNSHINE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modi, S.; Giri, B.; Gupta, V.K.; Lavania, S.; Sethi, V.; Sharma, N.S.; Pandey, S.; Vickers, S.; Dudeja, V.; Saluja, A.K. Minnelide synergizes with conventional chemotherapy by targeting both cancer and associated stroma components in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2022, 537, 215591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, A.; Hummel, B.; Khavaran, A.; Redhaber, D.M.; Aprile-Garcia, F.; Rawat, P.; Gundel, K.; Schneck, M.; Hansen, E.C.; Mitschke, J.; et al. Heat-Shock Protein 90 Controls the Expression of Cell-Cycle Genes by Stabilizing Metazoan-Specific Host-Cell Factor HCFC1. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 1645–1659.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-García, S.; Rodríguez, J.; Juliá, M.; Coursier, D.; Pérez-López, C.; Carnicero, P.; Villar, A.V.; von Kriegsheim, A.; Calvo, F. Proteostasis control via HSP90α sustains YAP activity to drive aggressive behaviours in cancer-associated fibroblasts. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, Y.; Farooqui, M.; Thomas, M.C.; Chiang, C.M.; Wei, L.N. Suppressive effect of receptor-interacting protein 140 on coregulator binding to retinoic acid receptor complexes, histone-modifying enzyme activity, and gene activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basalova, N.; Alexandrushkina, N.; Grigorieva, O.; Kulebyakina, M.; Efimenko, A. Fibroblast activation protein alpha (FAPα) in fibrosis: Beyond a perspective marker for activated stromal cells? Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Yu, D.H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, C.Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.H.; Ni, C.R.; Zhu, M.H. Expression of fibroblast activation protein in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma and its clinicopathological significance. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Novruzov, E.; Schmitt, D.; Cardinale, J.; Watabe, T.; Choyke, P.L.; Alavi, A.; Haberkorn, U.; Giesel, F.L. Clinical applications of fibroblast activation protein inhibitor positron emission tomography (FAPI-PET). NPJ Imaging 2024, 2, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glabman, R.A.; Choyke, P.L.; Sato, N. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: Tumorigenicity and targeting for cancer therapy. Cancers 2022, 14, 3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]