Abstract

The first generation of non-Aboriginal children born into the First Nations/Aboriginal country had their own relationship to colonising. For them, Aboriginal people were negotiated as part of play. The children escaped the strictures of work or classroom to spend time at the Aboriginal camps located near the homesteads, or to indicate Aboriginal presence on the stations. The locating of First Nations/Aboriginal people as part of play had an influence on the way non-Aboriginal people related to Aboriginal people and politics in Australian history.

1. Introduction

Australia was first colonised in 1788, yet from the perspective of Aboriginal country, colonisation was staggered and lasted until the 1930s. The first generation of white children born into different First Nations/Aboriginal country during those years maintained independent communication with Aboriginal people. In their own ways, they negotiated a culture other than their own. This paper examines records surviving from six children of the first generation on different First Nations/Aboriginal country who produced records or later reminiscences. William and Caroline Rothery near Carcoar inhabited Wiradjuri country in the from the 1830s and left texts and drawings in the torn registers of accounts of the family. William Ogilvie, on Gumbayngirr and Bunjalung country, left two childhood diaries in the 1870s; his sister, Mabel, aged sixteen, left one from the 1880s. Florence Bray recalled her childhood on Bunjalung/Githabul/Ngarkwal country, as did her neighbour, Jack Byrne. These were written in the 1930s and 1940s, recalling childhoods of the 1870s and 1880s. Together, these records give some idea of the children who inhabited a violent society. Children conceptualised First Nations/Aboriginal people in a distinct way, one that is influential in perceiving Aboriginal people today.

Stephen Muecke wrote that there are only so many ways non-Aboriginal people can conceptualise Aboriginal people, only so many available discourses. These available discourses dominate non-Aboriginal thinking today, as scholars such as Frances Peters Little have pointed out (Peters Little 2018). The first way is through enlightenment ideas of the noble savage, where Aboriginal people are innocent and childlike with no politics of their own. This, combined with starker racism of the ‘dying race’ or ‘treacherous savage’, give us the forms of thinking about Aboriginal people today (Muecke 1982, p. 98). The noble savage, as Frances Peters Little writes, is present in a great deal of very recent popular culture and historiography, where Aboriginal people do no wrong and are passive recipients of white attention (Peters Little 2002, p. 71). Such a perspective has been powerful in colonial history, where Aboriginal politics is centred on an idea of Aboriginal passivity, as if there is no pleasure in killing (Hercus and Sutton 1986, p. 205) or that the ‘native’ is a one-dimensional heroic or tragic figure. Peters-Little’s perspective highlights that the current, 2025, Australian political emphasis on First Nations welfare rather than political recognition is influenced by those ideas of childlike innocence—a familiar fantasy. As Peters Little and Joanne Faulkner have noted, Aboriginal people have been delegated the space of the child, and decisions are to be made for them (Peters Little 2002, p. 78; Faulkner 2016, p. xi).

Jenny Green and Tim Rowse have written of ‘recognition space’, looking at the plastic field of intercultural relations. Fluid and changing, this space, too, works to limit understandings of the past. Recognition space has a white fantasy element. Unlike Muecke’s available discourses, we non-Aboriginal people construct and reconstruct recognition space, drawing from many components. Rowse and Green write of Arrernte jurisdiction (this is the law of the First Nations around Alice Springs, Northern Territory, Australia) becoming ‘visible’ and entering the settler colonial archive as ‘a representation of (what we are choosing to call) Arrernte jurisdiction’ (Green and Rowse 2022, p. 186). Such self-qualification incorporates the authors themselves into recognition space; there can be nothing outside of it for non-Aboriginal people. Far more powerful than Muecke’s tracing of influences, which suggest that failings in perception may be overcome, Green and Rowse’s description disempowers non-Aboriginal readings of Aboriginal history and has far-reaching ramifications for Australian history. We historians may examine each other’s recognition space. Recognition space is a far looser imagining than Muecke’s available discourses; there is room to see multiple and contradictory influences.

This paper seeks to analyse children’s accounts and memories of intercultural relationships in Australia as part of their own and our non-Aboriginal recognition space. That is, the children’s mindset has ramifications today. Catherine Gay has written of children in Australia as ‘parties of encounter’, and her close study of the Seivwright, Hinkler, and Ware families in Victoria is influential here. She writes, ‘young people could both maintain and destabilize the cultural, social and racial order of imperialism’ (Gay 2025, p. 1) They could both accept the dominant social view of Aboriginal people and also undermine that power. Her sources are accounts on the activities of the children, reminiscences, paintings depicting the children, and the Seivwright girls’ ethnographic research, tending to an ethnography of Aboriginal people rather than concentrating on the perceptions of the girls. This is because of the nature of Gay’s records; only reminiscences, art, and child ethnography has survived, rather than diaries or letters. Also, the information from the girls’ records fits that of ethnographic colonisation, where knowledge belonging to First Nations/Aboriginal people is re-presented by non-Aboriginal people. My paper focuses on the components of the self that are represented in children’s diaries, drawings, and memoirs of childhood. It is a different project to Gay’s, but one can see her ‘maintaining’ and ‘destabilizing’ operative here. Each document is analysed according to how First Nations/Aboriginal people are represented in the wider context of the document. Above all, my paper does not attempt to discuss intercultural relationships—only their representation. Djon Mundine has recently explored intercultural relationships in art, and the complexity from his First Nations perspective is complicated by the non-Aboriginal inability to listen to art, to First Nations ideas and debate (Mundine 2025, p. 1). Writing of First Nations/Aboriginal business is best undertaken by Aboriginal people themselves. My focus is not to deny the complexity of kinship, ceremony, and culture but to make space for Aboriginal education in these fields.

Ann Curthoys in her discussion of popular historical mythology argues that the imagined world in which we have found ourselves in Australia derives from the cultural notion of the suffering settler, alone in the bush, struggling against the elements. This image of the Australian sufferer bleeds through ANZAC commemorations and can be widely politically utilised (Curthoys 2009, p. 1). Occupying the same theoretical space as Curthoys’s notion of suffering is the idea of the child. As Joanne Faulkner writes, there is a national obsession with childhood, whereby Australia is the child (Faulkner 2016, p. i), the young nation, born in 1901, steadying itself, learning to walk. This image has been rhetorical; powerful today, the child nation on the world stage is timid or careful not to offend what is perceived as greater powers. Drawing on parts of Faulkner’s work, this paper argues that the child hides within a particular variant of non-Aboriginal political and social relations to Aboriginal people, and this derived from nineteenth-century Australian children in contact environments. At its most complex, this relationship involves notions of play and escape. As in the slave states of North America or South Africa, First Nations/Aboriginal people were not only servants but inhabited camps near homesteads from and around which ceremonial life was conducted. Squatters had close relationships with people at the camp, both intimate and violent at once (P. J. Byrne 2023, p. 58), and their children had to negotiate this curious combination. Contact childhoods influenced the grammar of governance if we understand that in 1857, according to the Empire newspaper of 27 December 1857, 66% of the members of the Legislative Assembly of New South Wales were from squatting (grazier) backgrounds. They would have had, as children, close contact with Aboriginal people. The diaries, drawings, and memories referred to here allow for access to white children in contact environments, illuminating the child’s mentality. Aboriginal people were part of childhood, to be left behind, forgotten, or seen only in the context of a ‘welfare problem.’ (Attwood 2020, p. 137). The elements of the psyche apparent in these children reappear in modern politics and popular understandings.

The first generation of white children born on Aboriginal country were familiar with Aboriginal people, and they also inhabited a landscape deriving from atrocity. Judith Wright in The Generations of Men, expressed that there was a fear on the part of colonial mothers that ‘our children will become like them [Aboriginal people]’ (Wright 1959, p. 57) This is one reason Wright gave for the killing undertaken by her squatter ancestors. The diaries of the Wright family at the time of colonisation express no such fear at all. Judith Wright in the 1950s conjured or fathomed reasons for the killing undertaken. Nevertheless, her image of children slipping away from the house or camp, toying with another culture, is a useful one. White children always slipped away and needed to be drawn back to become civilised in the nineteenth-century perspective. Wet nurses, servants, and governesses all ‘took’ children, and their influence had to be managed, usually by making them see servants as objects of pity (Steedman 2007, p. 36; 2009, p. 228). Aboriginal people, whose camps non-Aboriginal people settled adjacent to, influenced the first generation of white children born near them.

Because the records are of such diverse natures, the methodology must differ for each. William Ogilvie’s diary was a gift from his grandmother, and he began entering daily events. His diary was not read by his parents, or else he would have been in more trouble than he usually was because he was frank about his father’s temper and his rules. Mabel Ogilvie recorded a visit to Yugilbar in her diary. These diaries can be examined linguistically to access the child’s psyche. We only have pencil drawings and lines written as punishment by the Rothery children. These must be approached mainly through art analysis. Reminiscences such as those of Jack Byrne and Florence Bray that were meant for publication are recalled memories, usually unconsciously chiselled to fit standard tropes of the Australian past. But there are slips and glosses that tell much of the mind that was created in the middle years of the nineteenth century.

2. The Families

William Montegu Rothery (1809–1899) and Fanny Oceana Lockyer (1817–1888) had fifteen children. The Rotherys occupied Cliefden, a run near Carcoar, in the central west of New South Wales from the early 1830s. One child born in 1856 survived a year, and Charlotte A Rothery lived only six years, from 1842 to 1848 (Geneanet 1996). The rest of the family lived long lives. The first person indicated in the old family register that included the drawings was Caroline Rothery, who was born in 1851, which made her 14 at the time of the drawings in 1864. It is partly her handwriting that appears in the repetitive lines written in the old registers of Cliefden, the run occupied by her family. The other name that is written is ‘William.’ Francis William, or William, was born in 1854, making him 10 in 1864. The drawings appear to have a similar theme, and that is the history of Cliefden, with illustrations of family stories.

Edward David Stewart Ogilvie (1814–1896) came from Merton near Muswellbrook, land granted to his father by Governor Darling in the 1820s. He married Theodosia Isabella de Burg (1838–1886). They had 12 children (WikiTree 2008). Edward married Theodosia when she was 20. He was then in his early 40s and had gone to Ireland to find a wife. He promised her a castle and built an Italianate castle on his run near the Clarence River, Yugilbar (Farwell 1973, p. 335). William Frederick Ogilvie was his eldest child, followed by six sisters, of whom Mabel was the sixth. William was born in 1862, making him 12 when his diaries were written. Mabel was born in 1866; she was 16 when her diary was written. These diaries were written in Sydney and Yugilbar. The Yugilbar sections are discussed here.

Joshua Bray (1838–1918) took up the Wallambin run in the Tweed Valley in far northern New South Wales in the early 1860s, coming from Tumut. He married Gertrude Nixon in 1866. They had 13 children, all who survived, except Clive who was killed in WWI. Florence was the third child, born in 1870, living until 1938 (Australian Royalty 2021). Florence wrote a memoir that was published in 1997 (Bray and Ebsworth 1997). The Byrne family were tenants of the Brays. James Byrne (1831–1916) married Bridget Clear (1836–1923). They had twelve children. Jack Byrne (1864–1954) was their third son. They had come from the Clarence River to the Tweed. Jack Byrne spent most of his life in western Queensland and in what would become the Northern Territory. He has Aboriginal descendants (F. Byrne 2023).

The occupation of all these areas of Aboriginal country was violent and merciless. Each of their wealthy fathers, apart from the Rotherys, records in their own diaries at least one punitive raid against local Aboriginal people (Bray 16 September 1866; Ogilvie 20 January 1856). James Byrne originally went with his brother Myles to the Tweed River Valley, and they were cedar getters—this group having a history of violence in Nambucca and Tweed (Blomfield 1981, p. 55). The last raid mentioned in the Bray papers occurred in 1866, the year of Joshua’s marriage to Gertrude. Jack Byrne would follow the killing fields in the 1880s to the 1940s, up to what would become the territory.

The children were born into war country. All of them had Aboriginal camps near their houses or across the creek.

3. Historiography of Children

Jan Kociumbus in her history of children in Australia concentrates on the controls operating on them, and the welfare strand of focus is an important component of the history of children, both First Nations and non-Aboriginal. Child abuse and removal centre in this kind of analysis, which sees state control and state power as central (Kociumbus 1997, p. 1). Carla Pascoe, in her excellent discussion (which need not be restated here) of the Australian historiography of children, makes a strong distinction between the history of childhood and the history of children. The former is concerned with ideas and ideals of childhood at any one time. The history of children is somewhat messier, concentrating on the recorded experience of children. Of particular importance to this latter historiography is the history of play. Pascoe has examined the use of space and objects by children in play. She writes that play can be seen as a protest against an adult world, that it is self-governed, and that it parodies (Pascoe 2010, p. 1143; 2011, pp. 3–4, 12, 60). Following Pascoe, this study examines children’s playfulness when confronted with authority, as well as the texts they created as play or in recording play.

Roger Cox sees the child as ‘an idea’ that has been ‘let loose on the world. ‘This idea resides in unexpected places, acquires unexpected meanings, and becomes the subject of controversy, a pawn in battles that have little to do with its origins’ (Cox 1996, p. 4) Exploring the meaning of the child through the words and images created by children results in the unexpected; when one examines children, the writer too is freed from societal constraint.

For Hyunsu Kim, children’s art is constructed from various experiences rather than being a simple product. Line quality, types of forms, and types of spaces are created through a process of interaction or discussion with the people and environment around them (Kim 2017, p. 101). In the Rothery drawings, we can see the process of decision making and collaboration; such decision making is also apparent in the Ogilvie diaries. How information is included may be analysed through Kim’s approach.

4. Slipping Away

The children with written records each recount incidents where they were alone with Aboriginal people. On 6 January 1875, William Ogilvie wrote, ‘Joey, King of the Bulginibar tribe came and I turned the fountain on for him.’ The Italianate castle included a courtyard and fountain, but such were water supplies that it rarely operated. William showed the King how it worked. William’s accounts of his involvement with Aboriginal people at the camp show a similar emphasis on usefulness and work. In September 1875, while Bob, an Aboriginal man, was away with the cattle, William ‘walked down to camp and gave a few pence to a gin.’ William was able to walk down to the camp by himself and interact socially with Aboriginal people. He recounted Bob’s activities more than any other person, ‘went down (by moonlight) to Bob’s hut, called him, saw a meteor. Bob didn’t come till half past seven’ (26 June 1875). William was walking around the camp at night. It is not clear if he meant Bob did not return until half past seven at night or in the morning. On 27 November, William writes, ‘I had a battle with Bob.’ This was fighting, or rather play fighting, and William had battles with his brother also. Bob was older than William because there was a ‘Mrs Bob’ mentioned, and Bob was employed as a guide for Edward Ogilvie.

This pattern of having a particular older Aboriginal friend is present in other written accounts. For Jack Byrne, it was Wallambin Johnny, ‘a King and a leader of his people.’ Jack spent hours with Wallambin Johnny, watching him swim and dive, learning stories from him, watching ceremonies. For Byrne, there were also political divisions associated with Wallambin Johnny. He recalled an Aboriginal man he called ‘the captain’, a stranger who did not speak English, who stopped his boat with three other Aboriginal men and commandeered it to go fishing, taking the frightened boy with them. Jack was 12 in the year 1876. ‘I feared that had Johnny and the Captain ever met, it would spell finis for the King.’ The captain ‘had the usual string girdle round the waist and a dingo’s tail bound round his long curly hair, in which he carried a tomahawk with a sharp pointed handle, a fire stick and a clay pipe. He had no nulla nulla, nor had any of the others, but one of the youths carried a shield.’ Jack was initially frightened by the men, but when he saw their skill at spear fishing, he wrote, ‘I was charmed, I could scarcely restrain a cheer.’ Jack’s written account captures the materiality of Aboriginal fishing, with each gesture and silent direction detailed. Though he feared for Wallambin Johnny, he was an enthusiastic audience to Aboriginal skill.

Jack had been on his way to obtain seed potatoes from further down the river. It was his mother who gave him these orders, as his father and older brother were away at Dunbible where they had a small cane plantation. ‘I had no end of instructions to hurry up and to be back by a specified time, without taking into account the fact that the tide was against me both ways.’ Like William Ogilvie, Jack wandered among Aboriginal people.

Florence Bray also writes of Wallambin Johnny and the camp that Byrne calls Jegiga. She too spent time with Aboriginal people.

There were generally no less than one hundred blacks camped on the plain behind the house. I remember the names of some of them. There was Abram, devoted to my father, Suzy his gin, also Polly whom I liked better than Suzy. Polly sewed very well and used to help us with our doll’s clothes and I thought her very nice looking.(Bray and Ebsworth 1997, p. 14)

Like William and Jack, Florence had one Aboriginal person she connected with. Since the Brays did not have Aboriginal servants inside the house, these contacts would have been in the camp. Florence, too, wandered.

In 1884, the Ogilvie family returned to Yugilbar to visit. They stayed in the schoolhouse because the main house was occupied by the manager of the run, Sydney Penrose. Mabel Ogilvie wrote in her diary on 15 March 1884, ‘in afternoon saw the little black children, heard them sing.’. At the houses the Ogilvies stayed at on their journey to Yugilbar, young squatter women had set up schools for Aboriginal children. Imitating them, Mabel, aged 16, and her sister, Theodosia, aged 21, set up a school at Yugilbar. The ‘little Black children’ came on odd days, and Mabel and her sister taught them reading and writing. Mabel sewed clothes for the children, which she refers to on 1 April 1884 as ‘dresses’, so it may have only been the girls she was teaching. However, like Florence, William, and Jack, Mabel also visited the Aboriginal camp to hear the children sing. Mabel wandered.

5. The Rothery Drawings

The Rothery children were allowed in the 1860s to play with the old family registers from 1836 and 1839. The registers were also a site of punishment; repetitive lines were written by two hands. The first was William’s; they were lines from history or geography books. The other, lighter hand was Caroline’s. The children also copied signatures and some letters of appointment of servants or letters from their father, William Montegu Rothery’s. The registers were also a place of play, and this play included a drawing of Aboriginal people.

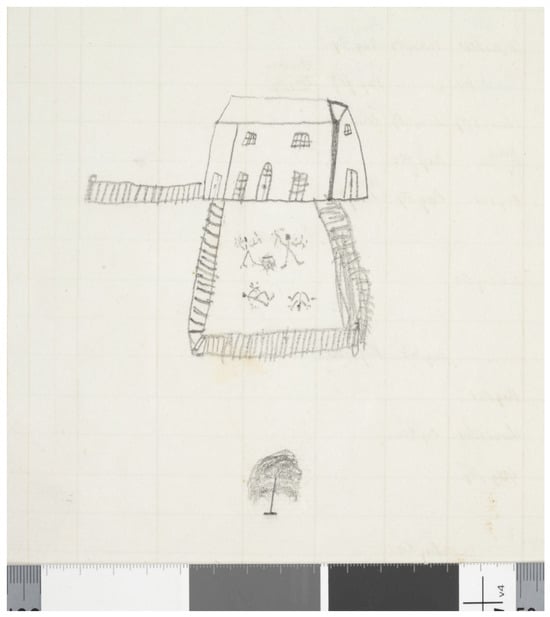

The Rothery drawings illustrate family history. There are 11 separate drawings in pencil in the empty pages of the Register of Accounts for 1836 and 1839, and one drawing (Figure 1) from the back of the 1836 volume shows a barn with a tree of heaven in the foreground. These drawings were made in the early 1860s when the register was no longer in use. In the yard of the barn is an illustration of four Aboriginal people. The tree of heaven was specially planted at Cliefden in the 1830s, and the species originates in China. Planting exotic trees was a merchant custom, and the Lockyer family had London merchant connections (Seppings Family History 2010). The rendering of the tree shows its importance to the family, but it is also a place and time locator. The barn was opposite the tree. The tree of heaven is a deciduous species, and the drawing is set in spring or summer. The event at the Aboriginal camp in the yard next to the barn occurred at a particular time because it was before a side fence, crossed out, was built. The tree, the hard lines of the barn outline, and the fences crossed indicate effort and a wish for accuracy. The representation of the fences indicates they were important spatial locators for the artist. Fences drawn hard and corrected appear in several of the drawings. In Figure 2 the house is drawn with large, curved fences on either side of it, as if they were protective arms. Fences have significance. Another hand had drawn the Aboriginal people. The lightness and skill suggest it was Caroline, as her handwriting was lighter and more graceful than William’s. The four Aboriginal people depicted are involved in a conflict, and two are lying on the ground, either dead or wounded, while the others brandish weapons. The fire in the middle of the skirmish shows it was a camp.

Figure 1.

First Nations camp near the barn.

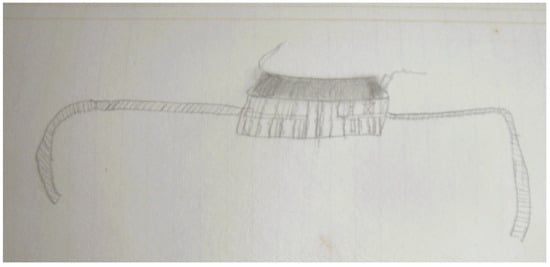

Figure 2.

The house with fences.

No written account of this incident survives, but it clearly represents an event that the child wanted recorded for accuracy. This is a very rare drawing of an Aboriginal camp. Joshua Bray did not feel himself skilled enough to be able to draw the camp near the house at Wallambin. Although there are drawings and photographs of Yugilbar, no image of the camp, so present in diaries, survives. Figure 1 represents intra Aboriginal conflict, as Jack Byrne also recalls in his understanding of the captain’s relationship to Wallambin Johnny. What makes this drawing unusual is that the Rothery family and others in the region excluded Aboriginal people from newspaper reports and diaries. There are no accounts of colonisation by this family. This erasure is confronted by the children’s drawing. They make visible not only Aboriginal people but also Aboriginal politics, as this drawing shows conflict between two groups of people.

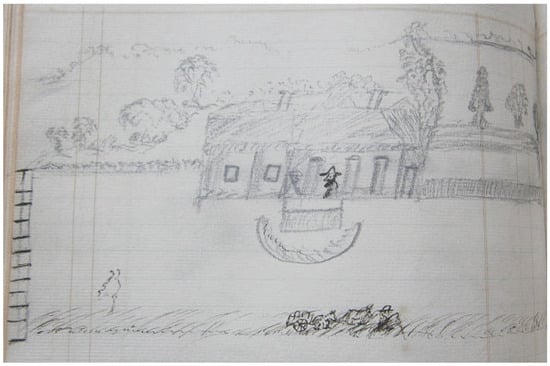

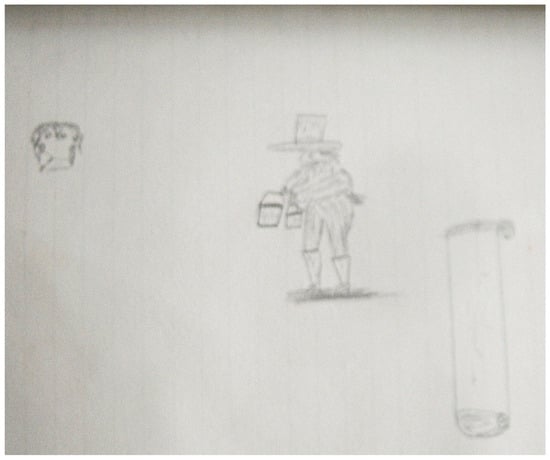

The other drawings are of two kinds—there are drawings that relate to the 1864 raid on Cliefden by the bushranger Ben Hall, another record of violence, and, secondly, risqué drawings. The bushranging incident is referenced in the old 1839 register. There is an elaborate drawing of the house with the trees and field in the background (Figure 3). A side fence is drawn in both pencil and ink. A newspaper report by the Western Herald in 16 November 1962 reports William Rothery claiming that Cliefden was ‘impregnably fortified’, meaning it was well protected from a bushranging attack. Perhaps such sentiments resulted in the children’s rendition of the fences. Curved at the entrance to the house are two gardens, one crescent shaped and the other square. Hidden in the long grass at the front of the property is a cart with two horses. These are drawn with ink. At the door of the house is a bearded man with a wide brimmed hat and a sharp black beard; he is also rendered in ink. They are both important to the story. The man with the beard looks out at us with a very clearly marked eye. The darker drawing of him in the landscape emphasises his menace. This figure with the same beard appears in the 1836 volume (Figure 4). He carries two buckets and has high Wellington boots. He stands beside an uncertain object that looks like a rolled-upswag. Stories of the Ben Hall bushranging gang compress their visits to several stations. Unlike the oral tales, the gang did not enter the Rothery household; they were repelled at the locked door, behind which Mr Rothery assured them he was well prepared for them. One of the gang left with the overseer’s Wellington boots.

Figure 3.

The bushranging attack.

Figure 4.

Bushranger with Wellington boots.

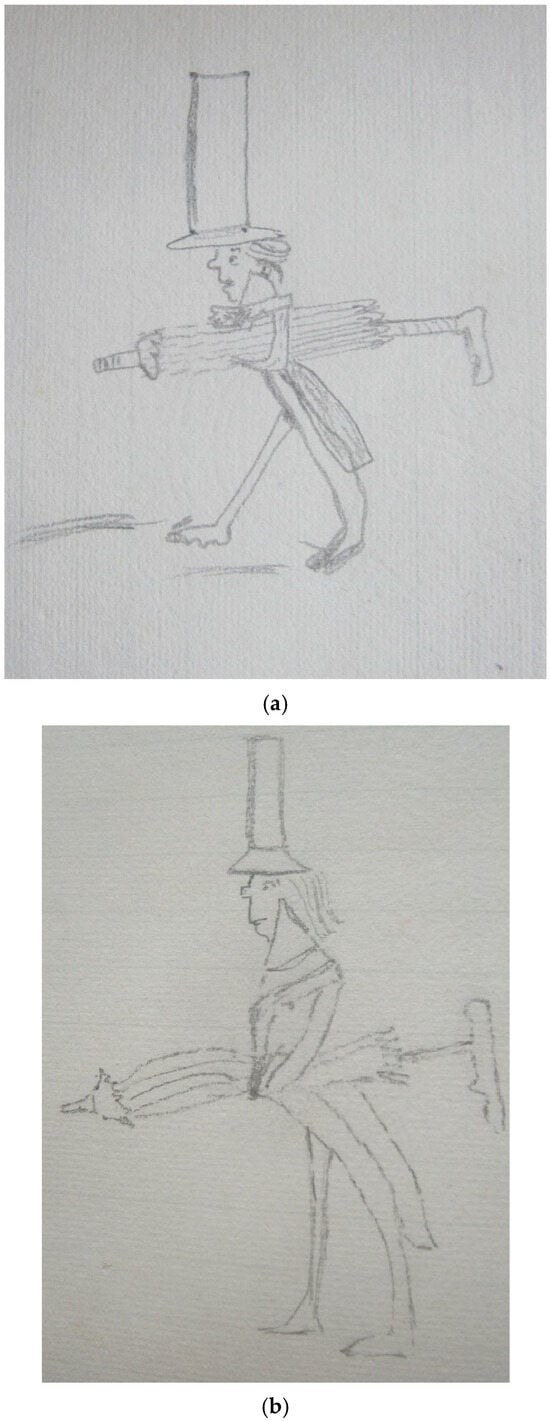

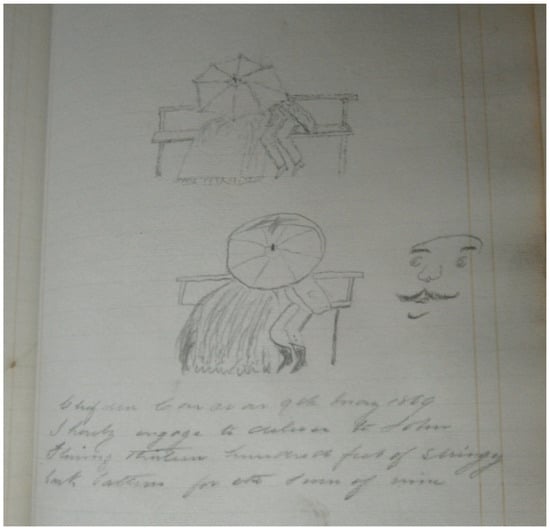

The second kind of pictures are risqué drawings of encounters between a white woman and man. There are two drawings of two separate men, both carrying an umbrella (Figure 5a,b). Their top hats are exaggeratedly tall. They wear different suits, and their shoe soles are different; the sense of accuracy is there again. The drawings may have come from different hands, but one is not a copy of the other because one is landscaped and the other portrait. The faces are similar enough to be a depiction of one man on separate days, but the chin on one of the figures is weaker, despite the nose being similarly rendered. The first carries a large beach-like umbrella high under his arm. The second carries it far lower on his body so it is in the same position as his penis; it stands out from the body, and the end of the umbrella is intricately drawn. Figure 6 is rendered in the same way—two drawings on a page indicating a seated man and woman kissing behind an umbrella. Only the skirt of the woman and the trousers of the man can be seen on the bench; the umbrella hides their identity. This is a secret, illicit relationship. Again, the men are differently dressed by the separate artists, with the first figure wearing a very ill-drawn baggy suit, the second figure wearing trousers and shoes, and the third wearing high black Wellington boots and close-fitting tight pants with buttons on the side, indicating a gentleman squatter. These are in two distinct hands or two styles of drawing. There are two attempts at beginning the umbrella rendition on the first page. The pencil strokes are more ragged in two of the drawings and finer in the third. The skirt of the woman has the same trim in all three pictures—this is a reference to one woman. On the side of the second page is a drawing of a man’s face with an elaborate curled moustache and beard. He looks surprised. Underneath is a handwritten copy of a work agreement from 9 May 1869, which may date the drawings, particularly as it is under the seated couple. It is a clearing agreement with John Fleming for ‘1300 feet of stringy bark for the sum of nine…’ and the copying is abandoned. The inclusion of the copying brings the authority of the father onto the page. But this is juxtaposed with the risqué image of the couple.

Figure 5.

(a) The umbrella carried high. (b) The umbrella carried low.

Figure 6.

The umbrella hides dalliances.

The effort at accuracy again suggests a connection to a true story about men with an umbrella having an assignation with a woman in secret.

The ragged strokes again appear in Figure 7, where a woman is shown in great detail in bed, with patterned bed hangings and an elaborate coverlet. She has a bedside table with books, and the end of the bed is drawn as if there are a series of books leaning there. This is not an attractive woman; her nose is big, her face marked with either wrinkles or cream, and her hair in a cap. She is sitting up stiffly in bed and she has large breasts covered tightly by a nightgown with frills at the neck. Walking away from the woman is a cat with what seems to be something in its mouth. Its hindquarters are a sharp inverted ‘v’ as if attention is meant to be drawn to them. This picture is meant to be comic in some way that escapes a 21st century viewer. Traces of sexuality in the breasts of the woman and the hindquarters of the cat suggest the humour is sexual in origin.

Figure 7.

A woman and a cat.

There are small, tiny, graffiti-like drawings in the register that resemble modern teenage graffiti of a vagina (Carrington 1989, p. 89). Lines written by Caroline suddenly transform into a love poem or song which cannot be identified. The playfulness and sexuality expressed in the drawings represent a subculture on Cliefden—that of the children of the family. Thus, a serious record of history exists alongside what would be considered in the nineteenth century disrespectful or sexualised imagery. The registers thus situate the Rothery children in the same position as those children with written records, in opposing authority and escape from restraint. This is particularly so when the registers are also clearly used for the writing of lines as punishment. And the Aboriginal camp is in this child play drawing, one of the very few references to Aboriginal people in the entire Cliefdon papers, the others being work agreements with Jacky Sloane and Maryanne on 8 September 1865. This play around drawing incorporates Aboriginal people and politics.

6. The Father

Children’s play and ranging about is countered in the records by evidence of the control of the father. Relationships with squatter fathers concerned discipline. Only Flora Bray recounts a story where her father is seen in a positive light, but he is reported as engaged in aggression against Aboriginal people.

On their return after hearing the ‘little Blacks’ who ‘sang to us’, it was late, and Mabel wrote ‘Papa not pleased’ (19 April 1884). The family left Yugilbar on the 22nd of April to travel around other squatter households on their way to Sydney. The last mention of the ‘little Blacks’ was the sewing of red petticoats for them, which further indicates they were all girls. But the visit to hear the singing would have been to the Aboriginal camp. Mabel and Theodosia’s venture outside the schoolhouse was also a walk away from their earlier, culturally appropriate role of teaching the Aboriginal children.

The father in squatting households perpetrated violence against Aboriginal people. At Yugilbar, physical violence was one means by which Ogilvie disciplined his Aboriginal workforce (Ogilvie Diary). Punitive raids on camps were sudden events; there was an instant reaction to a suspicion that Aboriginal people were stealing cattle or sheep or were intending to do so. The reaction was passionate, influenced by romantic ideals of loss of self or giving oneself up to desires (P. J. Byrne 2023, p. 84). This passion was carried into the household, and the children in the Ogilvie household appeared to have been disciplined in an erratic manner. On Boxing Day, 26 December 1874, William writes, ‘laugh at Papa at breakfast and get into disgrace’. On 28 June 1875, William wrote, ‘gave Stinyard’s Grandmamma seeds to plant. Papa was displeased because he said it was disobedience, and he kept me at French all afternoon.’ The next day, William let the horse, Duke, ‘through the little gate’ before he was to go for a ride—‘Papa made me stay indoors all afternoon.’ On 8 August, William noted, ‘Papa was angry at me for not answering properly.’ His exasperation with his father is apparent in his entry of 19 June 1875, ‘Papa angry at me because I forgot one thing about Cardinal for Mary.’ The other children were also disciplined; Em was thrashed ‘for tearing the paper’ on 29 January 1875 and whipped for making up the firewood on the 29th of July that year. Ed was locked in a room with bread and water all day.

Florence Bray recounts a story of her father’s violence to Aboriginal people.

Soon after he arrived on the Tweed they were sending mail to Ballina and decided that Mickey [Mickey the Priest] should take it. But Mickey did not want to go he said the road lay through enemy country and my father was determined he should go if only for the sake of discipline. Accordingly he set out at daybreak for the Black’s camp. The camp was at a little distance from the river, on some ground behind the Gray’s house which sloped down to the swamp. The smoke was just rising from the fires and dozens of picaninnies were running about screaming and playing. My father stole quietly along but the sharp eyes of the picaninnies espied him and they gave alarm. There was a wild commotion, gins and picaninnies screaming and dogs barking madly. Mickey started for the river. My father, who could, in those days run as fast as any black, raced after him and caught him just after he reached the riverbank. But Mickey slipped like an eel from his grasp, plunged into the river and disappeared into the thick scrub on the other side. My father could not hold him because he was greased from head to foot.(Bray and Ebsworth 1997, p. 14)

The story, like the drawings of William Rothery, is a family history. It represents an attack on an Aboriginal camp by a white man and the terror of women and children. Their expectation that a stalking white man meant an attack shows the Brays had not always lived in peace beside the camp. That the father could run as fast ‘as any Black’ indicates an equality in skill, something not apparent in Jack Byrne’s accounts where skill is utterly Aboriginal. But Bray is tricked; Mickey the Priest has on grease from an Aboriginal ceremony, and he escapes from Bray’s grasp. Deftness belongs to the Aboriginal person.

Florence Bray presents this as ‘an amusing story.’ If so, it is an amusing story that includes representation of the sheer terror of women and children. This ambiguity is also apparent in Jack Byrne’s reminiscences. When the captain leaves the boat, he reaches into the bushes and captures two wrens, which he kills and puts in his hair. He also obtains a carpet snake that he ties around his neck. He tells Jack that he is good for pulling the boat to where they wanted to fish, but he looks so amusing that Jack laughs in his face. Florence’s and Jack’s are stories of white superiority—Florence’s relying on the control of her father and his capacity to create fear, Jack’s because of his making fun of a powerful Aboriginal man, as if that power did not matter.

Jack Byrne withdraws his affection from Wallambin Johnny. His new interest was the first constable on the Tweed, Luke Thorpey, and his ‘big white horse.’ It is this man who would put a stop to the ‘treachery’ of the blacks—there was to be no more trouble. That there is no account of any ‘trouble’ at all in the rest of Jack’s memories is an indication of later Queensland activity affecting his thinking. Similarly, Florence writes that her mother must have been ‘terribly afraid’ with the large camp of Aboriginal people near the house. There is no mention of fear in the rest of her memoir; indeed, she wanders about the camp by herself. The Wright memoirs contain a similar sentiment—‘it is a wonder they did not kill us all’—but there was no fear mentioned at all in the Wright family’s diaries. The buzzing static of later ideas of the frontier influenced what was remembered.

The Rothery registers include lines written as punishment. One page belongs to Caroline with her fine handwriting, and the opposite page belongs to George, as if they sat side by side to enter them. This seems to be the pattern in the pencil drawings as well; they drew the same subject on opposite pages of the register, as if they were drawing at the same time or in response to each other. These lines contain sentences from English and European geography, history, and moral or religious texts. Interspersed between the lines are the children’s own insertions. George writes:

Henry Plantagenet became king after the death of his brother Richard. W.M Rothery esq. Australia Club, Syney [sic]. G. M Rothery esq Austral Thomas Iceley Esq Commining [sic] of Crown Lands of Carcoar. W. M Rothery esq Australia Club Club Club Club Club Club Club Club Club Coombling C John the youngest son of Henry Plantagenet1 became king on the death of his brother. Richard John the youngest son…

Exactly what the repetition of ‘club’ implies is difficult to be certain of, but it is onomatopoeic and is reminiscent of violence. This listing of gentlemen comes from letters entered into the register, but not a great deal of attention is paid to the correct spelling of proper nouns. The creativity is suddenly halted, as if George has been caught, and he continues his lines from the history of England. A great deal of copying of his father’s signature occupies George in the register, and the father, as in William Ogilvie’s diary, is the centre of attention.

Caroline’s lines are a foray into romance:

Edinburgh the capital, Edinburgh the capital capital city of Scotland an Island in the arctic ocean. An elegant running command admonition Genuine tranquility degenerates in the practice of virtue and is the first requisite of tolerable feeling by the calm and clear atmosphere for security come say say to me you love me And let us no longer tarry If you love as love you. Then why should we not marry. I promised fond love to or. And will be constant. So take me now as I am free. Or else you will have me never come say to me you love me true. And let us no longer tarry. If you love me as I love you then why should we not marry.2

This is a song, and the lines are repeated over and over until the end of the page. Caroline’s foray away from the lines is into the realm of romantic love. The song cannot be located, and she may have learned it from the servants, as it seems to be a folk tune. (Mark Finnane has suggested an Irish folk tune. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d3cPQK5pMxM, accessed on 25 August 2025).

Caroline plays with the idea of lines, and she does not appear to be interrupted, but immediately over the page one clear line is copied over and over again as if she has indeed been admonished. The line is ‘Command you may your mind from. [sic]’ and continues repetitively. Caroline has been brought to heel, into the disciplinary purpose of the lines.

7. Conclusions

Aboriginal people in these child accounts appear to be in the realm of escape and play. There is tension between the squatter father’s authority and the disrespect and humour shown in the Rothery drawings, William’s diary, Mabel’s records, and Jack’s memories. Florence joins her father’s brutality, as does Jack, with his adoption of the policeman and his horse. The affection between child and Aboriginal person is not long-lasting. The stories Wallambin Johnny told Jack and the accounts of the ceremonies Jack attended were published in the local newspaper by Jack in the 1940s, an ethnographic theft without permission, without regard for the owners of those stories.

In later life, Jack Byrne returned to the Tweed Valley from Kimberley to write about local Aboriginal people who were ‘gone’ despite his niece marrying into an Aboriginal family. His was always a racist position;, the Second World War was to him a ‘race war’, and Social Darwinism informed his perspectives. William Ogilvie did not return from England where he had gone to university. None of the Ogilvie children wanted Yugilbar, and it was left to Mabel. Early in the 1920s, Aboriginal people were persuaded to move off Yugilbar, and, according to the manager, the most resistant to such a move were the women, perhaps the little children that Mabel taught. Mabel herself had no objection to the move (P. J. Byrne 2020, p. 139). The relationship between the non-Aboriginal child and the Aboriginal person were fleeting rather than long-lasting.

Play becomes a locale of Aboriginal people; they are not part of what is adult, what is real. They are absent. This is relevant to the long-term problem First Nations people have in being listened to, in being taken seriously. Time and time again, they conduct policy analyses, telling the government and authority what authorities do not understand, only to be ignored (Watego 2021, p. 59). Secondly, the vacillating nature of play, the easy replacement of one playmate with another, the rapid movement of play itself, relates to inconstancy, the failure of ‘allies’ to be continually so, and the rapid movement of whites through Aboriginal settlements and towns means projects are begun again and again, and then let slide, to be forgotten about (Liddle 2025). Thirdly, Aboriginal people are associated with escape, with a particular kind of entertainment (Peters Little 2018).

How Aboriginal people came to be identified as children has been well discussed by writers such as Frances Peters Little. The identification of the nation with the child has also been explored, but to relate to Aboriginal people as children would has not been recognised as one of the components of politics. The non-Aboriginal person thus sees themselves as the child, engaged in play with the First Nations person. This is not serious and not real; as in play, it has vacillating attention, and loyalties can easily switch or be forgotten if something new appears. We do not find this openly discussed, but like Ann Curthoy’s ‘suffering’, it can be located today in the treatment experienced and described by First Nations persons.

The commonality of the children’s relationship to First Nations/Aboriginal people is remarkable—linking to one particular Aboriginal person, idolising them, following them about, and then forgetting them, and in some cases erasing their place, as in the case of Mabel and Jack. The statement indicating that Aboriginal people were ‘all gone’ represented was a powerful public statement by Jack in the local newspaper of the 1940s, influencing generations of writers about the Tweed. The eviction undertaken by Mabel in the 1920s was a physical erasure of Aboriginal people from Yugilbar All of the children created this play recognition space, and, as stated, they must have mirrored the experiences of the children who later became legislators. Play was powerful.

The author would like to thank Victoria Grieves, Tim Rowse, and Mark Finnane for their comments on this paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In the 1839 register. |

| 2 | 1839 register, Rothery Papers. |

References

Primary Sources

Bray Family Papers, State Library of New South Wales, ML MSS 1929.Jack Byrne newspaper articles, 1945–1947, Tweed Heads Historical Society, Tweed Heads, Australia.James Bray Diary, held by Tweed River District Historical Society, Tweed Heads Australia.Phillip Wright Papers, University of New England Archives, A430.Rothery Family Papers accounts, State Library of New South Wales, MAV FM4, 6481–2; 6484.Rothery Family Papers State Library of New South Wales ML MSS 10009.Empire.Edward Ogilvie Diary, State Library of New South Wales, ML 1686 Add On 2203, Vol III.Ogilvie Papers, University of New England Archives, A179.Trove search for violence on the Lachlan River.Western Herald.Secondary Sources

- Attwood, Bain. 2020. Rights for Aborigines. Melbourne: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Royalty. 2021. Available online: www.coraweb.com.au (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Blomfield, Geoffery. 1981. Baal Belbora, The End of the Dreaming. Sydney: Alternative Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, Florence, and Noella Ebsworth. 1997. My Mother Told Me. Sydney: Self-Published. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Frank. 2023. Living in Hope, The Complete Memoirs of Frank Byrne. Alice Springs: Running Water Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Paula Jane. 2020. Women, Reading and Colonisation. Clio Histoire: Femme et Societies 47: 123–41. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Paula Jane. 2023. Australian Squatter Space 1850–1880. Britain and The World 16: 58–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, Kerry. 1989. Girls and graffiti. Cultural Studies 3: 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, Roger. 1996. Shaping Childhood: Themes of Uncertainty in the History of Adult Child Relationships. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Curthoys, Ann. 2009. Expulsion, exodus and exile in white Australian historical mythology. Journal of Australian Studies 23: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farwell, George. 1973. Squatter’s Castle the Story of a Pastoral Dynasty; Life and Times of Edward David Stewart Ogilvie. Melbourne: Landsdowne Press. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, Joanne. 2016. Young and Free, [Post]colonial Ontologies of Childhood, Memory and History in Australia. London: Rowman and Littlefield International. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, Catherine. 2025. Children as parties of encounter on Australian Frontiers: Girls in Colonial Victoria. Settler Colonial Studies 15: 663–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geneanet. 1996. Available online: https://en.geneanet.org (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Green, Jennifer, and Tim Rowse. 2022. Mparntwe/Alice Springs: Towards a History of Indigenous and Settler Jurisdictions. In The Cambridge Legal History of Australia. Edited by Peter Cane, Lisa Ford and Mark McMillan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 186–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hercus, Luise, and Peter Sutton. 1986. This Is What Happened. Canberra: AIATSIS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hyunsu. 2017. Towards a Dialogic Understanding of Children’s Art Making Process. The International Journal of Art & Design Education 37: 101–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kociumbus, Jan. 1997. Australian Childhood a History. Sydney: Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle, Catherine. 2025. We Are Facing a Crisis. Youtube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z0Zfy12nf8U (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Muecke, Stephen. 1982. Available Discourses on Aborigines. In Theoretical Strategies. Edited by Peter Botsman. Sydney: Local Consumption Publications, pp. 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Mundine, Djon. 2025. Windows and Mirrors. Sydney: Art Ink. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe, Carla. 2010. The History of Children in Australia: An Interdisciplinary Historiography. History Compass 8: 1142–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, Carla. 2011. Spaces Imagined, Places Remembered: Childhood in 1950s Australia. Liverpool: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Peters Little, Frances. 2002. The Return of the Noble Savage by Popular Demand. Master’s thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Peters Little, Frances. 2018. Interview. Available online: https://satellitedreaming.com/sources/frances-peters-little-interview (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Seppings Family History. 2010. Available online: www.seppingsfamilyhistory.com (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Steedman, Carolyn. 2007. A Boiling Copper and some Arsenic. Servants, Childcare and Class Consciousness in late Eighteenth Century England. Critical Inquiry 34: 36–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steedman, Carolyn. 2009. Labours Lost, Domestic Service and the Making of Modern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watego, Chelsea. 2021. Another Day in the Colony. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- WikiTree. 2008. Available online: https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Ogilvie-709 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Wright, Judith. 1959. The Generations of Men. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).