Abstract

This article examines how the insecure and precarious legal status of adoptees gives rise to vulnerabilities, with a particular focus on the citizenship of foreign-born adoptees. The primary objective of this work is to identify vulnerabilities associated with U.S. citizenship rules. While adoption is often assumed to guarantee both familial belonging and a legal status of citizenship, the U.S. legal framework frequently reveals gaps that leave adoptees in vulnerable positions. By tracing how administrative requirements, adoptive parents’ lack of due diligence, and fragmented legal pathways create insecurity, this article shows that the law itself may generate or exacerbate vulnerabilities it purports to resolve. Drawing on the concepts of vulnerability and navigating the intersection of family law and immigration law, the analysis highlights how citizenship is more than a legal status, affecting deeper issues of identity-building and belonging. The article concludes by underscoring the need for a protective, adoptee-centered, coherent approach to citizenship rules, one that offers better legal permanence for adoptees.

1. Introduction

At first glance, adoption1 seems a practical, straightforward match between a child without permanent care and a family hoping to expand. Once the child is brought home, the state, the community, and the parents must recognize them as fully and legally belonging to that family. Yet, beneath this reassuring promise of protection and belonging lies a series of cracks due to legal shortcomings in cases concerning foreign-born adoptees. Significantly, one of these cracks relates to their legal status and citizenship.

Many parents may believe that the act of adoption in itself grants automatic citizenship; however, this is not always the case. While it is true that, in the United States (hereinafter: ‘U.S’.), the Child Citizenship Act of 2000 (CCA) offers a guarantee that foreign-born adoptees may automatically acquire citizenship. However, although automatic, this citizenship is not without requirements. If these key requirements are not fulfilled, the adoptee does not automatically benefit from these citizenship rules and needs to follow general naturalization procedures instead. Where adoptive parents have overlooked bureaucratic steps or were unaware that completing an adoption does not automatically confer legal citizenship, the consequences can be severe. Adults who believed they were citizens may discover, during routine interactions with immigration authorities, that they are not.2 Despite the provisions introduced by the CCA, the promise of a secured citizenship has proven illusory for many adoptees. Beneath the apparent clarity of the statute lies a coverage gap that has left some adoptees deported and others in limbo,3 living with a constant fear of expulsion from the only country they have ever known. The vulnerability of foreign-born adoptees is worse for those who were subject to disrupted or successive adoptions.

What emerges is a paradox: adoption, meant to end the uncertainty of a child’s status by providing permanence, makes the adoptee susceptible to uncertainty due to citizenship rules. Foreign-born children, placed into new families, may grow up in a prolonged and latent state of non-belonging, trying to navigate complex immigration laws. The end result is more than just legal complexity; it extends to issues of identity development and social belonging.4

By employing notions of legal vulnerability, this paper aims to explore the intrinsic risks associated with citizenship rules governing foreign-born adoptees. The remainder of this article is organized and structured as follows: Section 2 explores the complex role of citizenship rules while examining the regulatory regime that governs adoptees’ citizenship in the U.S. In Section 3, the interplay between vulnerability and law is presented, along with working definitions of vulnerability, based on a social-legal framework. Section 4 presents the analysis of the identified vulnerabilities, ranging from structural shortcomings to particularized context-sensitive issues. Lastly, this article concludes that U.S. citizenship rules governing adoptees would benefit from a more adoptee-centered approach. This is because immigration law should not serve as a tool to induce or expeditiously ease adoption practices, but to safeguard the adoptees’ best interests.

2. Citizenship Rules for Foreign-Born Adoptees in the U.S.

Defining citizenship is a complex matter that has been subject to much academic debate. For some, citizenship is seen as a right-based, duty-based, or even as a fluid, dialectical relationship between rights and duties (Lister 2003, pp. 13–14, 42). Where citizenship is understood as a dialectical relationship, it can be described both as a status, encompassing a wide range of rights, and as a practice, involving political participation broadly defined (ibid.). Others argue that modern citizenship resembles feudal practices, where citizenship is mainly assigned at birth based on birthplace or parentage and, like feudal status, highlights the inherent unfairness of being born in a wealthy country (Song 2025, p. 2). Attributes such as totalitarianism, sexism, and racism5 are also explored as linked to citizenship. A third group of scholars understands citizenship as a framework for political participation, social organization, and a sense of belonging (Mantha-Hollands and Orgad 2021, pp. 1522–25). It is connected to a collective sense of civic identity, which not only reflects, but also determines the inner circle of a national community (Daniel 2000, p. 242). Egalitarian perspectives on citizenship include the right to collective self-determination, the duty to remedy historical injustice, and the duty to extend membership to resident non-citizens in its conceptualization (Song 2025, p. 1). The term ‘legal status’ will often be used in this article to refer to ‘citizenship’.

The link between adoption, citizenship, and immigration laws is equally complex. Some suggest that adoptees are essentially immigrants who might not see themselves as such, even though they benefit from immigration rights (Kim and Park Nelson 2022, p. 62). Others dismiss the immigrant classification, reinforcing automatic citizenship rights (considering that adoptees would be ‘born-as-if’) (ibid.).6 While some consider retroactive birthright citizenship to be a policy that undermines adoptees’ origins and the sovereignty of the sending state (ibid., p. 74), there are advantages to having a stable and permanent citizenship status. For adoptees, in particular, citizenship can be closely tied to identity formation (Myers et al. 2020, p. 206).

Some authors have suggested that immigration law appears to serve as a tool to induce or ease adoption practices. This is because the presence of foreign-born adoptees in the U.S. has historically been based on exceptions and immigration privileges (ibid., p. 62). To put it differently, foreign-born adoptees have been subject to policies that were mainly designed to bring children into U.S. homes expeditiously (ibid., p. 71). Using immigration law as a tool to bring children shows a contrast within immigration law itself. The law appears to serve different purposes: while the law itself claims to provide some level of protection against the precarious legal status of adoptees, its underpinning objective seems to be that of facilitating adoption procedures.

In relation to adoptees’ protection, U.S. rules on citizenship have been criticized for a possible lack of automatic citizenship to be conferred on adoptees. The lack of automatic citizenship created gaps between kinship and citizenship, which affected legal and cultural contexts (ibid., p. 63). Automatic citizenship rules are intended to serve as a safeguard for foreign-born adoptees. They serve as a measure against statelessness and represent an instrument of integration in a new culture, enabling individuals to enjoy the benefits of citizenship. The idea behind automatic citizenship is to ensure psychological family unity, equalizing the citizenship status of biological and adopted children while also removing the threat of deportation (Romero, as cited in Manta and Robertson 2023, p. 488). However, automatic citizenship rules do not come without criticism. It has been pointed out by the former Immigration and Naturalization Service that to retroactively confer birthright citizenship may rewrite adoptees’ story, erase the foreign origins of the child, and challenge the sovereignty of the sending nation (Kim and Park Nelson 2022, p. 74).

To provide a brief historical overview, U.S. law did not account for any rules that would allow derived U.S. citizenship before 1952 (U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services n.d.-b). Until 1978, U.S. citizenship and naturalization laws still did not provide for an automatic acquisition of citizenship.7 However, parents could apply for naturalization on the adoptees’ behalf, in accordance with the former Immigration and Naturalization Act 323. From 1978 until 2001, with the introduction of the current CCA, there was also no automatic derived citizenship for adoptees. The adoptee could become a citizen through a general naturalization procedure or through a citizenship application, to be filed by the adoptive parents through the Immigration and Naturalization Service, in accordance with the former Immigration and Naturalization Act 322 (Cody 2023, p. 233).

Currently, U.S. citizenship rules for adoptees are governed by the CCA (U.S. Congress 2000), which took effect in 2001. The CCA amended the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) to eliminate the requirement that adoptive families naturalize their children after an adoption was complete (ibid., 230). On the basis of the CCA, foreign-born children born on or after the 28th of February 1983 can now automatically gain citizenship before turning eighteen, so long as statutory requirements are met. While the CCA secures citizenship rights for many individuals, its protection does not extend to those born before 1983, to those whose adoption was never properly finalized, and to some individuals who entered the U.S. on a temporary visa (Manta and Robertson 2023, p. 486). This is because this group of adoptees is particularly excluded from the legal text.

According to CCA, a child who immigrates to the U.S. as the adopted child of a U.S. citizen automatically becomes a U.S. citizen if the following conditions are met: (a) the child is below 18 years of age; (b) the child was lawfully admitted to the U.S. as a permanent resident before their 18th birthday and (c) the child resided in the U.S under their parent’s legal and physical custody before their 18th birthday.8 This automatic citizenship can be obtained via three immigration routes connected to adoption: the Hague Adoption Procedure, the Orphan Procedure, or a Family-based Petition.

Before the CCA, the absence of automatic citizenship created a state of ‘limbo’ that left many adoptees uncertain about their immigration status. Despite the CCA being introduced with the aim of addressing this regulatory gap, in practice, the limbo still remains. Although no official records exist, some online sources estimate that the number of adoptees who lack citizenship ranges from 18,000 to 75,000 individuals (Bergsten 2025; Galofaro and Tong-Hyung 2024). Recognizing the limited scope of the CCA, attempts have been made to address its age barrier. In particular, the proposed bill Equal Citizenship for Children Act, introduced in 2023, aims at a retroactive effect for those born after January 1941 (U.S. Congress 2023) However, this retroactivity would not apply to intercountry adoptees or others who arrived in the U.S. on a non-immigrant visa (e.g., a tourist/visitor visa) and did not obtain a green card before the age of 18 (Adoptee Rights Law Center 2025). Another proposed bill is the Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2024 (U.S. Congress 2024). As introduced, it would provide automatic citizenship to intercountry adoptees, regardless of their date of birth. To do so, it would amend Section 320(b) of the INA to remove the age cutoff. This would create, in practice, the retroactive effect that CCA is lacking. However, this bill is still undergoing legislative scrutiny. Despite these two legislative initiatives, it appears that changing the citizenship rules governing adoptees presents significant difficulties. According to Cody, the outlook of the proposed bills is not promising. Repeated attempts to correct the CCA have failed, and Congress is unlikely to prioritize this kind of legislative correction to the INA in the future (Cody 2023, p. 248).

This section has explained how, while the CCA amended the prior law to confer automatic citizenship rights, this measure is not sufficient in itself to address the vulnerabilities associated with adoptees’ citizenship. Building on this discussion, the next section turns to the concept of vulnerability, exploring how it has been theorized in connection with the law. By understanding vulnerability not merely as individual susceptibility but as a phenomenon connected to, generated, and exacerbated by the law, it is possible to better grasp why certain adoptees are left exposed despite formal legal protections. Following this conceptual framing, the article then identifies some of the problems embedded in current adoption and citizenship legal frameworks.

3. Vulnerability and Law

How do legal systems address vulnerabilities, and who could be considered vulnerable? Fineman’s Theory on vulnerability aims at answering those two inquiries. Vulnerability, as described by Fineman, is a constant and universal human issue, as there is always an imminent possibility of harm, injury, or misfortune that humans cannot eliminate (Fineman 2010, p. 267). Therefore, vulnerability is not understood as an exceptionality, but rather as a complex phenomenon that can manifest in multiple forms, ranging from physical to financial, legal, and economic contexts. Additionally, although universal, vulnerability also has an individual component. This is because humans are placed differently in relation to their vulnerability (ibid., pp. 268–69), displaying varying levels of resilience (Gant 2023, p. 12). Similarly, vulnerability is a common feature of human life, although not everyone is vulnerable in the same way (Butler, as cited in Godden-Rasul and Murray 2023, p. 9).

The Vulnerability Theory asks for a responsive state, capable of acting in the face of the vulnerability of its subjects (Fineman 2010, pp. 255–56). Under this lens, States should focus on providing equal opportunities, rather than developing public policies under an anti-discrimination paradigm. In law-making, the theory mandates that the legislative process must remain attentive to the subjects’ dependency (ibid., p. 263). The idea of a vulnerable agent should be central to policy design (Fineman 2015, p. 2091). Viewed in light of this theory, while vulnerability cannot be eradicated, it can be mediated, compensated or lessened through State action (ibid., p. 2090). Nonetheless, this theory is not without its critics. Cooper has argued that there is a need to link the vulnerability theory to an analysis of relative privileges that are enjoyed by some, as a contrast to the element of ‘universality’ (Cooper 2015, pp. 1374–76). Kohn has indicated that this theory has some limitations as it cannot prescribe exact policies or laws, despite recognizing the theory’s relevance in rethinking the role of the State in light of social welfare (Kohn 2014, pp. 25–26).9 Others have noted that this theory may be as problematic as a categorical approach to vulnerability, as it considers everyone to be equally and essentially vulnerable (Luna, as cited in Hudson 2018, p. 31). Although Finneman’s theory is constructed on human dependencies (inevitable and derivative) associated with social and cultural discrimination, it provides great insights for analyzing legal frameworks (Gant 2023, p. 12). This is because, as explained by Gant, equality of treatment in some circumstances does not amount to fair treatment, since this may ignore degrees of power and resilience that different agents may have in a particular context (ibid., p. 14). The Vulnerability Theory has been explored in various other fields of law, including insolvency proceedings (ibid.), environmental law (Dobbelsteyn 2024), access to justice (Pilliar 2023), State vulnerability (MacDowell 2018), migration law (Hudson 2018), labor law (Rodgers 2024), and adoption (Perovic 2025).

In contrast, for others, vulnerability can be defined through a categorical approach, applied to individuals and their membership of a distinct population categorized as ‘vulnerable’. Being classified as vulnerable amounts to a group that is deserving of special protections (Hudson 2018, p. 4). As an example, in the context of migration, a vulnerable subject can be defined as being part of a vulnerable group that is at a higher risk than members of other groups within a specific administrative and legislative entity (Gilodi et al. 2022, p. 623). Some examples of those risks include discriminatory practices, violence, social disadvantage, and economic hardship, amongst others.

Vulnerability is recurrently defined in association with ‘risk’, as a vulnerable agent is someone with an internal risk factor or subject to a system that is exposed to a hazard. It refers to an intrinsic tendency to be affected or susceptible to damage (ibid.). This is also observable in migration law, where being in vulnerable situations refers to those who are at increased risk of violations (ibid.) and abuse. Gilodi et al. indicate how risk is interestingly referred to as a state of vulnerability to structural conditions rather than individual attributes (ibid., p. 624).

Vulnerability may also refer to a lack or limited capacity of an individual, or to a diminished level of autonomy and higher dependency (ibid., pp. 624–25). Gidoli et al. present a conceptualization study on vulnerability by differentiating vulnerability as: (a) innate, (b) situational, and (c) structural. Innate vulnerability refers to a vulnerability inherent in a person, whereas situational vulnerability refers to a temporary context to which an agent is subject. Structural vulnerability relates to systems and structures that create vulnerability, focusing on institutional, legal and economic conditions (ibid., p. 628). This vulnerability is contextual and social (ibid., p. 629). Nonetheless, some authors suggest that adopting a categorical approach to vulnerability may lead to additional complex issues, as it risks stigmatizing agents and subjecting them to paternalistic protections (Hudson 2018, p. 30).

Adoption and Vulnerability

As previously mentioned, the legal practice of adoption has also been examined through the lens of vulnerability. According to Perovic, applying a vulnerability approach to intercountry adoption redirects attention from only individual rights to a broader outlook including socio-economic and legal structures involved with the vulnerabilities of the adoption triad (Perovic 2025, p. 1004).10 Perovic explains the systemic challenges faced in cases of intercountry adoptions, such as inconsistent regulations, illegal practices, and misuse of the system. In addition, there is a lack of adequate pre- and post-adoption services that ought to be provided by the government, as well as the lack of transparency and oversight of private adoption agencies (ibid., p. 1005).11

This systemic approach allows Perovic to explain that vulnerabilities experienced by birth families, adoptive families, and children cannot be viewed in isolation. As an example, birth families are subject to a systemic issue of economic hardship, property distribution, and resource allocation. Birth families may also experience a lack of accessible alternatives like financial aid, counseling, and temporary foster care solutions. At the same time, however, adoptive families also display vulnerabilities, such as significant emotional and psychological strain throughout the adoption process and having to navigate complex cultural integration. Often intermediaries between the two, adoption agencies must manage a complex web of international law, as well as State vulnerabilities which are often connected to limited funding and staff resources. In relation to adoptees, Perovic identifies the psychological and social vulnerabilities regarding belonging and the enduring psychological impacts of the intercountry adoption (ibid., p. 1007).

Having outlined some definitional parameters of vulnerability, the following section aims to contribute to previous academic scholarship and turns to an investigation of foreign-born adoptees’ vulnerabilities. Although adopting the concept of structural and systemic vulnerability is an interesting choice for evaluating the legal system related to citizenship rules and adoption, this article focuses on the identification and analysis of the processes through which vulnerability can be generated, including systemic or individual-related vulnerabilities.

As a working definition, vulnerability is understood here as the identifiable risks associated with being a foreign-born adoptee in light of citizenship rules. The risks refer to contexts that can affect or impede the acquisition of citizenship by the adoptee. Such risks may vary from being inherently connected to the structure of the adoption process and immigration, to situational, context-specific risks related to particular scenarios of adoptive parents.

4. Legal Analysis: Citizenship Rules in the U.S and Connected Vulnerabilities

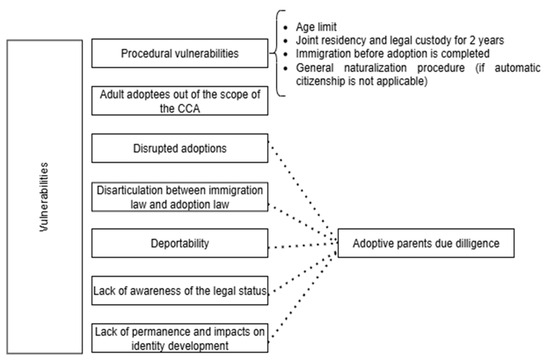

This section delves into the vulnerabilities connected to adoption and immigration processes, examining how legal and procedural factors can create risks for foreign-born adoptees. To better understand these dynamics, the following figure (Figure 1) presents a visual overview of the vulnerabilities discussed in this section. It then explores various contextual scenarios of foreign-born adoptees, such as a child being adopted in the U.S followed by immigration procedure, a child that is brought to the U.S. with the intention of being adopted (guardianship), and adoptions via the Orphan Procedure and the Hague Procedure.

Figure 1.

Diagram by the author.

4.1. Disarticulation: Immigration and Adoption Law

One may assume that completing the adoption of a foreign-born child necessarily makes a child a U.S. citizen. After all, this child was raised in a U.S. household, attended U.S. schools, speaks the language, and is immersed in the U.S. culture. Yet, the law tells a different story: completing an adoption does not automatically entail a lawful status or even citizenship under U.S. rules. Put differently, there is a disarticulation between rules on adoption procedures and the rules for the legal status of the adoptee.

A child might be successfully adopted in a particular U.S. state, but fail to meet the 2-year legal custody and joint residency requirements with the adoptive parents,12 which is one of the requirements for starting a family-based immigration procedure13 that results in citizenship under the CCA. In other cases, the adoptee may be granted a visa to enter the U.S. territory without having their adoption completed, such as in cases of guardianship of the prospective adoptive parents.14 These examples serve to illustrate that a completed procedure within adoption law does not necessarily match a completed procedure in accordance with immigration law, and vice versa.

This disarticulation can be considered a potential vulnerability. It is understandable that some may interpret a completed domestic adoption as proof of the adoptees’ lawful status in the U.S. from the perspective of an ordinary citizen. And this interpretation has happened in practice: many adoptees have not discovered until years later that they are not actually citizens, because immigration procedures were not properly initiated or finalized by their adoptive parents (Manta and Robertson 2023, p. 483).

In reality, navigating adoption rules and rules on the legal status of adoptees may feel like exploring a maze, maneuvering different levels of norms: immigration rules are established through Federal law (Immigration and Nationality Act 2019), while adoption procedures are primarily regulated by State law (Ahlers 2014, p. 56). If the adoption refers to an intercountry adoption, additional laws come into effect, such as the laws of the country of origin (ibid., p. 22). Although it is true that adoption rules are solely responsible for creating the legal parent–child relationship, adoptees would benefit from a better articulation between immigration and family law.15

4.2. Procedural Vulnerabilities

In cases of a family-based petition for a foreign-born child in the U.S.,16 there are possible pitfalls in this procedure that could translate into vulnerabilities for adoptees. Imagine a child who entered a U.S. home through adoption. Law requires more than parental attention and protection. Formal steps17 must be taken to secure this child’s citizenship status, as adoptive parents must submit the family-based immigration case to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). This institution is responsible for processing immigration and naturalization applications.

There are requirements for the concession of citizenship: adoptive parents must complete an adoption procedure in a State court18 before the adoptee reaches 16 years old (U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services 2024b), and parents must present proof of legal custody and joint residency for at least two years before or after adoption (U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services 2024a).19 This means that, while adoption of children above 16 years old is possible, it would not lead to immigration benefits. Although having an approved family-based petition by the USCIS may entail automatic citizenship (as established by the CCA), adoptive parents still need to submit the petition and comply with formal requirements to acquire citizenship on the adoptees’ behalf. In cases where the child was brought illegally into U.S. territory, the procedure is additionally challenging, as this child can be considered out of status and may accrue unlawful presence if over 18 years old.

If the age limit or the period of joint residency and legal custody are not met, then the adoptee may only be a lawful permanent resident, subject to the general rules on naturalization. In this scenario, a possible vulnerability may arise: if adoptees wish to obtain citizenship, they will need to undergo a general naturalization procedure, which is also applicable to other adult immigrants (Laybourn 2024, p. 8).20

Although some may indicate that adoptees are, in essence, also somewhat immigrants (Kim and Park Nelson 2022, p. 2), others point out the difference between adult immigration and foreign-born adoptees (Manta and Robertson 2023, p. 512). In adult immigration, the relationship with the country of residence is usually volitional, whereas the relationship between adoptees and their adopted countries is fully mediated through their parents (ibid.). According to Manta and Robertson, bringing a child from abroad to U.S. society makes an implicit promise that the child has the opportunity to become an integrated part of the polity. Therefore, the authors state that the children are expected to be included as U.S citizens in their adoptive family and society. This begs the question of how a legal system can allow such adoption practices and promote integration into a new culture and family setting, if not granting equal citizenship rights to those who are part of the family (ibid., p. 523).

Along those same lines, it is important to note vulnerabilities connected to the general naturalization procedure, which lead to the lack of equality of citizenship between natural-born and naturalized individuals. Some have indicated that, although equality of citizenship should be guaranteed by law, this is not often the case. In practice, naturalized individuals may face citizenship precarity, which includes the risk of denaturalization, the difficulty of proving citizenship, and the failure to extend constitutional birthright citizenship to individuals born in the U.S. territories (ibid., p. 504). General rules on naturalization may create a vulnerability, considering that the adoptee cannot commit any type of crime prior to obtaining citizenship, differently to natural-born citizens.21 As an example, while secluded, an American prisoner remains a part of the country and cannot be entirely excluded from the nation as such, in contrast with the ‘naturalized’ adoptee (Manta and Robertson 2023, p. 524). Morawetz explains that when immigration law treats adoptees differently in light of criminal convictions, this constitutes disrespect towards the commitment made by the adoptive parents to their foreign-born adopted children (Morawetz, as cited in Kim and Park Nelson 2022, p. 73). Additionally, being subject to general rules on naturalization may also exacerbate the feeling of displacement in adoptees, where they have to prove their cultural belonging (ibid., p. 62).

However, even if one can become a U.S. citizen via automatic citizenship rules by the CCA (i.e., assuming the age requirement and the 2-year period are met), some authors indicate that there is still a lack of equality between adoptees and non-adoptees. This is because adoptees remain unable to confer an immigration benefit to their biological family (E. Kim 2007, p. 499)22 a privilege that others may enjoy by virtue of their status as natural-born U.S. citizens (Bergquist 2007, p. 18).

Adoptions may also take place via the Orphan adoption procedure23 or the Hague Procedure in accordance with 101.B.1.F, and G of the INA. Those are the cases of adoptees who were born in Ukraine24 and Ireland, for example, and are not in U.S territory. In these circumstances, it is possible that the adoption procedure took place entirely abroad. In that event, the adoptee will be awarded a special visa, which grants citizenship upon entry into the U.S.25 In this scenario, the child seems to be less vulnerable to risks related to their citizenship status. However, another possibility is delaying the completion of the adoption procedure (or re-adoption) until after the child enters the U.S. territory.26 Those cases are also referred to as guardianship cases. The adoptee may be entitled to automatic citizenship under INA § 320, provided that the adoption or re-adoption of the child is completed in the U.S.

However, a question ought to be asked: what if the adoption is not finalized, or the child is not re-adopted in accordance with the requirements of State law? If the adoptive parents do not meet this requirement, then the child is not entitled to automatic citizenship, but only to legal resident status. This status, in turn, does not automatically entail the legal status of a citizen.27 Although adoptees may still benefit from being residents, the child’s familial and cultural connection to their country of birth has been severed in favor of a permanent connection with the adoptive family that may not exist (Manta and Robertson 2023, p. 513). Therefore, the fact that the prospective adoptee can immigrate without a fully completed adoption procedure can be a vulnerability to their legal status.

One could wonder if a possible solution following the non-completion of an adoption is that the foreign-born adoptee ought to return to their birth state. However, once again, another vulnerability arises: if the adoptee were to return, would careful consideration be given to supporting the adoptee’s needs? (ibid., p. 500). In practice, matters have unfolded differently in cases of deported adoptees.28 Kim explored cases of voluntary returns, which did not occur without challenges (notwithstanding their voluntary nature). Adoptees’ first trip back could be complex, filled with psychological experiences that challenge identity and previous narratives of coherent selves (E. Kim 2007, p. 511). If challenges arise in voluntary returns, they are all more likely, if not exacerbated, in cases of forced returns.

Cases of disrupted adoptions may also be indicative of vulnerability. Suppose the original adoption was disrupted before the adoptee obtained citizenship, in cases of a family-based Petition. In that case, the child needs to be re-adopted by new adoptive parent(s) and meet the procedural requirements of age and legal/joint residency. If the requirements are met, adoptive parents may apply for the Certificate of Citizenship (U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services n.d.-a). However, in this described scenario, adoptees may experience heightened vulnerability as they need to promptly undergo an entirely new adoption procedure (including the matching process and assessment of prospective adoptive parents) to ensure their citizenship status. This vulnerability overlaps with the previously described vulnerability–heavy reliance on adoptive parents’ due diligence.

Besides possible procedural pitfalls, the system is strongly reliant on the adoptive parents’ initiative and due diligence. That is to say, adoptees’ legal status is heavily dependent on the adoptive parents’ actions and their capacity to be willing, able, and legally knowledgeable enough to navigate the citizenship process on their children’s behalf successfully (Manta and Robertson 2023, p. 523). In relation to older adoptees (particularly those who did not benefit from the CCA), parents who did not have their children naturalized left the adoptees vulnerable to deportation (Bergquist 2007, p. 6). This is a critical point: not only are foreign-born adoptees removed from their country of origin, but they are also often young and unaware of the procedural needs related to their citizenship status. Adoptees have no management or control over this matter and therefore cannot determine if all necessary steps were taken to secure their citizenship or residence permit. Adoptive parents, therefore, play a key role in preventing this vulnerability.

4.3. Acutely Vulnerable: Adult Adoptees

This article explored that, even with the current CCA legislation, which aimed to address citizenship vulnerabilities, some vulnerabilities still remain. However, a particular group of adoptees is acutely vulnerable, as they fall out of the scope of the automatic citizenship rule. Adoptees who were above 18 years old are left responsible for their own naturalization, as they are explicitly excluded by the language employed in the legal text (Kim and Park Nelson 2022, p. 77). The irony is that the CCA had been introduced as a bill in part because of the deportation of some adult adoptees (ibid., p. 76). Hauenstein considered this a shocking contradiction, stating that ‘in the CCA, a class of adoptees is protected from statelessness while another class is directly exposed to risks of deportation’ (Hauenstein 2019, p. 2145). This would violate the notion of equal treatment for children, regardless of the circumstances of adoptees’ birth (ibid., p. 2146).

This older group of adoptees is particularly vulnerable, considering that, before the CCA, adoptees were also required to be naturalized by their adoptive families to gain citizenship. However, many adoptive families were unaware that this naturalization process was required or were deterred by the costly and complicated process (Cody 2023, p. 229). There are cases where adoptees were denied citizenship due to their adoptive parents failing to file just one document (‘N-600 Form’) before the adoptees’ reaching legal age (Manta and Robertson 2023, p. 501). The lack of due diligence of adoptive parents left adoptees subject to the vulnerability of being deported, such as in the case of Adam Crasper, a Korean adoptee deported at the age of forty-one (H. Kim 2019). The same applied to Schreiner, Monte Haines, Phillip Clay, Russel Green, John Gaul III, and Joao Herbert, all cases of known adult deportations (Kim and Park Nelson 2022, pp. 73–78; Hauenstein 2019, p. 2134). As an acute vulnerability, it is worth noting that all of those adoptees were deported to a country where they did not speak the language. For Romero, this reveals the sad reality of non-citizen adoptees, whose existence is in a state of limbo, ‘being unsure whether they will be able to return, while trying to navigate a life in a foreign country, without cultural competency, language skills or support.’ (Cody 2023, p. 23).

As the State, adoptive parents, and professionals pilot the adoption procedure, it is reasonable that many adoptees are unaware of their own citizenship status (Associated Press 2019).29 This amounts to another vulnerability: lack of knowledge about one’s citizenship status. As an example, Amie Kim wrongfully believed she was a naturalized U.S. citizen by her parents and committed a felony by voting in the 1992 presidential elections at the age of eighteen (Kim and Park Nelson 2022, p. 61; Cody 2023, p. 229).30 Therefore, one may believe they are a U.S. citizen, despite their adoptive parents not having followed the procedural steps for citizenship concession.

As mentioned, there are cases where, even if the adoptive parents correctly follow the procedure, the outcome of the process is a residence permit rather than citizenship.31 In such cases, adoptees would be subject to the general naturalization procedure. This puts adoptees in a vulnerable position, as they may be unaware of the additional requirements for naturalizing as a U.S. citizen, as opposed to obtaining derivative citizenship through adoption.32 Even if adoptees are able to undergo the naturalization procedure, this returns the analysis to the risks attached to general naturalization rules.

Citizenship rules affect more than just one’s legal status. Identity issues are particularly prevalent in adoption contexts, and those can be deeply affected by rules on citizenship. Adoptees must not only engage in the same process of identity development that domestically adopted children must undergo, but they also face an additional level of insecurity about their legal belonging to the country (Manta and Robertson 2023, p. 509). Manta and Robertson explain the importance of ensuring a feeling of ‘permanence’ (ibid., p. 511), opposing a fear of deportation (Hauenstein 2019, pp. 2125, 2137).

Not only is not knowing one’s legal status a vulnerability, but also becoming aware that one is not a U.S. citizen may also be perceived as such. In adoption contexts, adoptees’ need to develop a sense of self-identity, integration, and belonging may be worsened by not being recognized as citizens.33 In other words, there is an emotional toll associated with discovering one is not a U.S. citizen after being a foreign child subject to adoption (Hauenstein 2019, p. 2125). An adoptee described the feeling of becoming aware of her current legal status as ‘not exactly a Korean citizen and not exactly a US citizen’ (Kim and Park Nelson 2022, p. 61). For the authors, this reveals the connection between legal citizenship and cultural citizenship via cultural belonging (ibid.). Therefore, the idea of legal citizenship may be interconnected with a cultural identity. Where this legal citizenship is perceived as precarious or something that could be revoked, problems arise of an ‘in-between, liminal, or hybrid cultural identity’ (ibid., p. 62).

5. Discussion: A More Adoptee-Centered Approach to Immigration and Adoption Law?

This article began by exploring the contrasting paradox of U.S. adoption practice: although intended to resolve the uncertainty of a child’s status by providing permanence, it left the adoptee susceptible to uncertainty due to citizenship rules. To promote adoptees’ welfare, connected to a sense of legal permanence, this article offered an analysis of the vulnerabilities associated with the U.S. legal framework. Vulnerabilities were defined as the risks associated with being a foreign-born adoptee in light of citizenship rules. Risks referred to contexts capable of affecting or impeding the acquisition of citizenship by the adoptee. The risks varied from being inherently connected to the structure of the adoption process and immigration, to situational risks related to particular scenarios of adoptive parents.

Although adoption may lead to certain vulnerabilities in identity-building and belonging (Keyes et al. 2013, p. 644), adoptees who are foreign-born are in an enhanced context of vulnerability. While the CCA has been a great step towards a more protective framework of citizenship rules, a crucial point must be reiterated: the automaticity of citizenship under the CCA is not a complete solution for all adoptees. In fulfilling the CCA‘s citizenship requirements, we may find additional procedural pitfalls such as the age limit and the relevant period for joint residency and legal custody.

The disarticulation between immigration law and family law, along with the complicated intersection between different legal frameworks in cases of intercountry adoption, creates a maze of rules that are complex to navigate. As it is not strange to interpret a completed domestic adoption as proof of the adoptee’s lawful status in the state, a better articulation between laws could offer more protection to the adoptee. Additional risks are connected to potential deportability, disrupted adoptions, immigration before adoption is finalized, uncertainty about one’s own legal status, not being able to benefit from citizenship status, being subject to the general naturalization procedure, and not being covered by the automatic citizenship rules of the CCA. Such issues extended beyond the mere acquisition of a legal status, as citizenship is for some also a form of cultural identity and belonging. Adoptive parents are a key figure in this vulnerability analysis as they may cause or prevent additional vulnerabilities, while they may also be a vulnerability themselves. The system is strongly reliant on the adoptive parents’ due diligence, translated into their capacity to be willing, able, and legally knowledgeable enough to navigate the citizenship process on their children’s behalf successfully.

This paper concludes that a more adoptee-centered approach to citizenship rules is needed and suggests careful consideration of the identified vulnerabilities in future law-making. Immigration law in adoption contexts should not serve as a tool to induce or expeditiously ease adoption practices, but to safeguard the adoptees’ best interests in having a safe, permanent, and recognized legal status. In this context, some measures could offer additional protection to adoptees, such as a simpler citizenship path and a more seamless interplay between immigration and adoption law. In cases of guardianship, where the adoptee must be re-adopted or have their adoption finalized in the U.S. to gain citizenship, citizenship could be granted upon entry into the U.S. territory, rather than being delayed until the completion or re-adoption.34

Conferring retroactive effects to the CCA would be an important measure to mend the ‘limbo’ that adult adoptees may currently find themselves in. Those adoptees are deserving of special protection, given their heightened status of vulnerability. In relation to procedural requirements for family-based petitions, immigration law would benefit from rethinking the age cutoff and the two-year period for joint residency and legal custody. Although such requirements may have been designed to avoid immigration fraud, this may come at the expense of adoptees’ feelings of legal permanence.

Interestingly, perhaps the main suggestion of this article is the creation of a due diligence requirement for adoptive parents in adoption procedures, which includes legal awareness or a commitment to strive for their adopted children’s citizenship (when applicable). Although the lack of adoptive parents’ due diligence may, to some extent, be solved by the automatic citizenship rules of the CCA, adoptees would benefit from additional legal protection. Being able to qualify as a diligent, knowledgeable and aware prospective adoptive parent could be an important selection criterion in adoption procedures. Such a criterion would add an additional layer to the already existing layers of care that should be provided by parents towards their children. This measure would also help to articulate different laws, connecting immigration and adoption procedures. Requiring legal awareness from adoptive parents could be achieved through specific preparatory courses on parenting adoptees, an obligation to obtain proper legal advice, or a signed declaration that adoptive parents are aware and will comply with the necessary steps required in citizenship procedures.

Needless to say, evaluating law from a perspective that diminishes the risks of not obtaining U.S. citizenship does not erase or undermine the value of adoptees’ country of origin citizenship. This origin/birth-citizenship is a relevant legal status and has been explored as a valuable form of redress in cases of adoption (Van Steen 2025, p. 20). Nonetheless, if one wishes to provide a sense of security and legal protection to the foreign-born adoptee regarding their status in the U.S., facilitated access to citizenship should be provided, without any detriment to the citizenship of the country of origin. After all, having access to one’s origin’s citizenship is a relevant component of the adoptees’ right to know.35 As a limitation, this article did not explore the vulnerability of citizenship laws from the perspectives of other agents involved in adoption, such as adoptive parents, birth parents and the State. Nonetheless, although this article focused on the analysis of the U.S. citizenship law, these findings are somewhat extendable to other legal systems which display a similar disarticulation between adoption and immigration procedures.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Eleonora Di Franco, Kevin van Abswoude, and Henrique J. Bezerra Marcos for their valuable assistance in preparing this manuscript, as well as their insightful comments and constructive suggestions, all of which have greatly enhanced this article. I also thank the anonymous peer reviewers and Editor Gonda van Steen for their helpful feedback and guidance throughout the review process.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Some authors point out that adoption can be seen as a historical and customary practice, considering that the integration of orphaned children into stranger households is a centuries-old practice (Cantwell 2011, p. 2). Others point out that although adoption of children is a familiar practice in modern society, it was neither historically nor culturally universal and that traditional adoptions were intended for family succession rather than child protection (Kyung-eun 2021). Recently, there has been a global shift in the adoption debate: initially portrayed as an inherently good practice that benefits all, it is now subject to criticism due to systemic abuses in transnational practices (Cawayu 2023, pp. 27–28). |

| 2 | Refer to Section 4.3 on the lack of awareness of adoptees’ legal status. |

| 3 | The resulting lack of coverage for a significant number of U.S. international adoptees has led to deportation for some and fear of deportation for others (Hauenstein 2019, p. 2125). |

| 4 | Although this article refers to citizenship as a possible tool for belonging, it is worth pointing out that citizenship does not automatically entail or relate to belonging. While citizenship is a formal legal status, belonging refers to a deeper level of inclusion, such as social and cultural (Erdal et al. 2018, pp. 707–9). Research has also indicated that citizenship policy does not have a moderating effect on the association between citizenship and national belonging (Simonsen 2017, p.16). |

| 5 | For example, in Menzel, citizenship laws are not treated just as technical rules, but as tools to maintain racial hierarchies. (Menzel 2013, pp. 29–58). |

| 6 | According to Kim and Park Nelson, ‘foreign-born adoptees have long been viewed as non-immigrant immigrants, whose legal and cultural citizenship is considered to be, like transracial adoptive kinship itself, (as-if) natural-born and (almost) white.’ (Kim and Park Nelson 2022, p. 62). |

| 7 | U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Policy Manual Section 2–Eligibility, documentation, and evidence. Available at: https://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual/volume-5-part-f#3#2 (last visited 1 September 2025). |

| 8 | Additional requirements may apply depending on the route through which the child enters the immigration system and whether this child entered U.S. territory legally. Refer to (U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services n.d.-a). |

| 9 | In this piece, the author Kohn proposed that vulnerability should not be identified as a fixed trait of individuals, but rather as a context-specific issue. |

| 10 | Adoption triad refers to children, birth families, and adoptive families. |

| 11 | In some jurisdictions, such as Brazil, adoptions are done exclusively via public state-run institutions. However, in jurisdictions such as the U.S., private adoption agencies are allowed to guide and intermediate adoption procedures in cases of intercountry adoption. Similarly, the Netherlands also allowed procedures guided by private adoption agencies before the intercountry adoption ban that took place in 2024. |

| 12 | INA §101(b)(1)(E). |

| 13 | Petition I-130. |

| 14 | For more on guardianship, refer to p. 11. |

| 15 | The disarticulation between immigration and adoption Law is not unique to the U.S. legal system. Such disarticulation is also seen in many different jurisdictions such as Australia and Canada. |

| 16 | INA §101(b)(1)(E) and Petition I-130. |

| 17 | A detailed chart on adoptees’ citizenship is provided by the Adoptee and Foster Family Coalition of New York. (10 January 2025). Available at: https://affcny.org/au-citizenship-resources-for-intercountry-adoptees (accessed on 20 October 2025). |

| 18 | Adoption may have occurred in or outside the U.S. territory. Refer to p. 8; except if the context involves the adoption of an older sibling. |

| 19 | Except in cases where the period can be waived in cases of abused children. |

| 20 | Whether adoptees are identifiable as ‘immigrants’, or ‘as-if-natural-born children of U.S citizen parents’ who deserve special citizenship protection is not a matter without debate (Laybourn 2024, p. 8). |

| 21 | Refer to Section 4.3 Acute vulnerability on how citizenship was denied to adoptees who had committed criminal offences. |

| 22 | The author mentioned that, in fact, Korean American adoptees who have been reunited with their birth families as adults have recently discovered that their rights to sponsor their Korean relatives’ entry into the U.S. have already been forfeited. |

| 23 | Orphans can be the result of the death, disappearance, abandonment, desertion, separation, or loss of both parents, or for whom the sole or surviving parent is incapable of providing proper care. Quiroz explains that adoptions take place in the context of losses, which may result from a variety of separations, which are not restricted to the death of biological parents. Some of those children may be adopted because their parents had been detained or deported (Quiroz 2022, pp. 42–44). |

| 24 | State not party to the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption. |

| 25 | Cases of IR-3 or IH-3 Visas. |

| 26 | Cases of IR-4 or IH-4 Visas. |

| 27 | Refer to p. 9 for more on naturalization procedures. |

| 28 | Refer to p. 12 on the case of Adam Crasper. |

| 29 | For example, Paul Fernando Schreiner spent 30 years believing he was an American citizen (Associated Press 2019). See more at: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/i-m-american-adopted-u-s-parents-deported-brazil-n1014031 (accessed in 1 July 2025). |

| 30 | According to Cody, ‘many adoptees are unaware of their non-citizenship status in the United States and only learn they are not citizens when deportation proceedings are initiated against them after a U.S. criminal conviction.’ (Cody 2023, p. 229). |

| 31 | Cases of adoption of children above 16 years old, for example. |

| 32 | As an example, if one is unaware that they still need to obtain citizenship through naturalization, they might plead guilty to criminal charges which would impede the acquisition of citizenship. This was the case of Anissa Druesedow was deported to Jamaica in 2004 because her parents did not get her naturalized while she was a minor, and she pleaded guilty to criminal charges. For more on lived vulnerabilities by adoptees, refer to (Manta and Robertson 2023, p. 485). |

| 33 | Refer to (Manta and Robertson 2023, pp. 487–92) on the feeling of loss of American identity by an adoptee after a late discovery of a lack of citizenship. Kim-Alessi compared the late awareness of not being a citizen with a ‘car crash.’ |

| 34 | Similarly to the procedure applied to IR-3 or IH-3 Visas. |

| 35 | For more on the adoptees’ right to know, refer to the previous work of this Author. |

References

- Adoptee Rights Law Center. 2025. FAQ: U.S. Citizenship and Intercountry Adoptees. Available online: https://adopteerightslaw.com/faq-adoptee-citizenship/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Ahlers, Glen-Peter Sr. 2014. Adoption law in the United States: A Pathfinder. Child and Family Law Journal 2: 2. Available online: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/cflj/vol2/iss1/2 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Associated Press. 2019. “I’m an American”: Man adopted by U.S. parents deported to Brazil. CBS News. June 5. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/im-an-american-man-adopted-by-u-s-parents-deported-to-brazil/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Bergquist, Kathleen Ja Sook. 2007. Right to define family: Equality under immigration law for U.S. inter-country adoptees. Georgetown Immigration Law Journal 22: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten, Susanné Seong-eun. 2025. Some US Adoptees Fear Stricter Immigration Policies, Mass Deportations. Human Rights Watch. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/02/07/some-us-adoptees-fear-stricter-immigration-policies-mass-deportations (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Cantwell, Nigel. 2011. Adoption and Children: A Human Rights Perspective. Issue Paper 2, Strasbourg, p. 7. Available online: www.commissioner.coe.int (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Cawayu, Atamhi. 2023. Searching for Restoration: An Ethnographic Study of Transnational Adoption from Bolivia. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium; pp. 27–28. Available online: https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/01H7XN0JF52GKC9QHE9E1QN5YM (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Cody, Halley. 2023. America’s hidden citizens: The untold stories of the unconscionable deportations of its international adoptees. Seattle University Law Review 47: 227. Available online: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sulr/vol47/iss1/5/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Cooper, Frank Rudy. 2015. Always already suspect: Revising vulnerability theory. North Carolina Law Review 93: 1339–96. Suffolk University Law School Research Paper No. 15–23. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2605151 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Daniel, Dominique. 2000. Automatic birthright citizenship: Who is an American? In Federalism, Citizenship, Collective Identities in U.S. History: Amsterdam: European Contributions to American Studies. Amsterdam: VU University Press, p. 242. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbelsteyn, Erin. 2024. Ecological vulnerability and socioecological justice: A vulnerability approach to ecological law in Canada. Justice, Ecology, Law, & Place 1. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4937587 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Erdal, Marta Bivand, Elin Martine Doeland, and Ebba Tellander. 2018. How citizenship matters (or not): The citizenship–belonging nexus explored among residents in Oslo, Norway. Citizenship Studies 22: 707–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineman, Martha Albertson. 2010. The vulnerable subject and the responsive state. Emory Law Journal 60: 251–76. Available online: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol60/iss2/1 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Fineman, Martha Albertson. 2015. Vulnerability and the institution of marriage. Emory Law Journal 64: 2089–134. Available online: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol64/iss6/10 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Galofaro, Claire, and Kim Tong-Hyung. 2024. Thousands were adopted to the US but not made citizens. Decades later, they risk being deported. AP News. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/adoption-citizenship-congress-immigration-a1ec84a94f2442e3dc4b7a31cad27d21 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Gant, Jennifer L. L. 2023. Vulnerability theory in insolvency law. In Rethinking Insolvency Law Theories in a Changing World: Perspectives for the 21st Century. Edited by Emilie Ghio, John Wood and Jennifer L. L. Gant. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Gilodi, Amalia, Isabelle Albert, and Birte Nienaber. 2022. Vulnerability in the context of migration: A critical overview and a new conceptual model. Human Arenas 7: 620–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godden-Rasul, Nikki, and Colin Murray. 2023. Accounts of vulnerability within positive human rights obligations. International Journal of Law in Context 19: 597–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauenstein, Holland L. 2019. Unwitting and Unwelcome in Their Own Homes: Remedying the Coverage Gap in the Child Citizenship Act of 2000. Iowa Law Review 104: 2123. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, Ben. 2018. Migration in the Mediterranean: Exposing the limits of vulnerability at the European Court of Human Rights. Maritime Safety and Security Law Journal 4: 4–30. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3688533 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Immigration and Nationality Act. 2019. Available online: https://www.uscis.gov/laws-and-policy/legislation/immigration-and-nationality-act (accessed on 7 October 2019).

- Keyes, Margaret A., Stephen M. Malone, Anu Sharma, William G. Iacono, and Matt McGue. 2013. Risk of suicide attempt in adopted and nonadopted offspring. Pediatrics 132: 639–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Eleana. 2007. Our Adoptee, Our Alien: Transnational Adoptees as Specters of Foreignness and Family in South Korea. Anthropological Quarterly 80: 497–531. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30053063 (accessed on 1 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kim, Eleana, and Kim Park Nelson. 2022. “Natural Born Aliens”: Transnational Adoptees and US Citizenship. In Adoption Across Race and Nation–U.S. Histories and Legacies. Edited by Silke Hackenesch. Athens: The Ohio State University Press, ISBN 0814282601 (ebook). [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hayeon. 2019. Adopted and Deported, Orphaned and Detained: The Case of Adam Crapser and the 20,000 Deportable Korean Adoptees in the U.S. Border Criminologies. University of Oxford. Available online: https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2019/02/adopted-and (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Kohn, Nina A. 2014. Vulnerability theory and the role of government. Yale Journal of Law & Feminism 26: 25–26. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2562737 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Kyung-eun, Lee. 2021. The Global Orphan Adoption System: South Korea’s Impact on Its Origin and Development. Seoul: KoRoot Publisher. ISBN 978-8996879886. [Google Scholar]

- Laybourn, SunAh Marie. 2024. Critical adoptee standpoint: Transnational, transracial adoptees as knowledge producers. Genealogy 8: 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, Ruth. 2003. What is Citizenship? In Citizenship: Feminist Perspectives. Edited by J. Campling. London: Palgrave, pp. 13–14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDowell, Elizabeth L. 2018. Vulnerability, access to justice, and the fragmented state. Michigan Journal of Race & Law 23: 51–90. UNLV William S. Boyd School of Law Legal Studies Research Paper Series. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3217152 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Manta, Irina D., and Cassandra Burke Robertson. 2023. Adopting nationality. Washington Law Review 98: 483. Available online: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol98/iss2/6 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Mantha-Hollands, Ashley, and Liav Orgad. 2021. Citizenship at a Crossroad. International Journal of Constitutional Law 18: 1522–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, Annie. 2013. Birthright citizenship and the racial contract: The United States’ jus soli rule against the global regime of citizenship. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 10: 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Kit, Amanda L. Baden, and Afonso Ferguson. 2020. Going Back “Home”: Adoptees Share Their Experiences of Hong Kong Adoptee Gathering. Adoption Quarterly 23: 187–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovic, Bojan. 2025. From stalemate to solutions: Rethinking intercountry adoption through vulnerability theory and technological innovation. Mississippi Law Journal 94: 923–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Pilliar, Andrew. 2023. Vulnerability theory and access to justice: Elaborating possibilities for legal system design. In Law, Vulnerability, and the Responsive State. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, Pamela Anne. 2022. US adoption and fostering of immigrants’ children: A mirror on whose rights matter. In Adoption Across Race and Nation: US Histories and Legacies. [E-book, Formations: Adoption, Kinship, and Culture]; Edited by Silke Hackenesch. Athens: The Ohio State University Press, chap. 2, pp. 39–58. Available online: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/gdc/gdcebookspublic/20/21/75/86/21/2021758621/2021758621.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Rodgers, Lisa. 2024. Chapter 5: Vulnerability theory. In Research Methods in Labour Law. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 623–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, Kristina Bakkær. 2017. Does citizenship always further Immigrants’ feeling of belonging to the host nation? A study of policies and public attitudes in 14 Western democracies. Comparative Migration Studies 5: 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Sarah. 2025. Is citizenship like feudalism? An egalitarian defense of bounded citizenship. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services. 2024a. Family-Based Petition Process. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Available online: https://www.uscis.gov/adoption/immigration-through-adoption/family-based-petition-process (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services. 2024b. Instructions for Form I-130, Petition for Alien Relative. Available online: https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/forms/i-130instr.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services. n.d.-a. After Your Child Enters the United States. Available online: https://www.uscis.gov/adoption/after-your-child-enters-the-united-states (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services. n.d.-b. Policy Manual, vol. 5, Part F. Available online: https://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual/volume-5-part-f-chapter-3#3 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- U.S. Congress. 2000. Child Citizenship Act of 2000, H.R. 2883, 106th Congress. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/106th-congress/house-bill/2883 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- U.S. Congress. 2023. Equal Citizenship for Children Act of 2023, H.R. 1386, 118th Congress. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/1386/text (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- U.S. Congress. 2024. Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2024, S. 448, 118th Congress. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/4448/text (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Van Steen, Gonda A. H. 2025. Adoption agrafa, parts ‘unwritten’ about Cold War adoptions from Greece: Adoption is a life in a sentence, adoption is a life sentence. Genealogy 9: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).