Abstract

First Nations children remain dramatically over-represented in Australia’s Out-of-Home Care (OOHC) system, particularly in New South Wales (NSW), which continues to report the highest numbers nationally. This narrative review, grounded in a relational First Nations Standpoint Theory and decolonising research paradigms, to critically examine the systemic, structural, and historical factors contributing to these disproportionalities. Drawing on interdisciplinary evidence across law, criminology, education, health, governance studies, and public policy, the analysis centres Indigenous-authored scholarship and contemporary empirical literature, including grey literature, inquiries, and community-led reports. Findings reveal that the OOHC system reproduces the colonial logics that historically drove the Stolen Generations. Macro-level structural drivers—including systemic racism, Indigenous data injustice, entrenched poverty and deprivation, intergenerational trauma, and Westernised governance frameworks—continue to shape child protection policies and practices. Micro-level drivers such as parental supports, mental health distress, substance misuse, family violence, and the criminalisation of children in care (“crossover children”) must be understood as direct consequences of structural inequality rather than as isolated individual risk factors. Current placement and permanency orders in NSW further compound cultural disconnection, with ongoing failures to implement the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (ATSICPP). Contemporary cultural rights and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) frameworks highlight the urgency of restoring Indigenous authority in decision-making processes. The literature consistently demonstrates that cultural continuity, kinship networks, and ACCO-led models are sort to produce stronger long-term outcomes for children. The review concludes that genuine transformation requires a systemic shift toward Indigenous-led governance, community-controlled service delivery, data sovereignty, and legislative reform that embeds cultural rights and self-determination. Without acknowledging the structural drivers and redistributing genuine power and authority, the state risks perpetuating a cycle of removal that mirrors earlier assimilationist policies. Strengthening First Peoples governance and cultural authority is therefore essential to creating pathways for First Nations children to live safely, remain connected to family and kin, and thrive in culture.

1. Introduction

First Nations children remain significantly over-represented in statutory Out-of-Home Care (OOHC) across Australia, with New South Wales (NSW) consistently reporting the highest numbers of child removals nationwide (AIHW 2023; SNAICC 2024, 2025). This over-representation is not an isolated phenomenon but reflects enduring patterns of state intervention in First Nations families, shaped by colonial logics, racialised governance, and systemic failings in the provision of culturally safe support services (Davis 2019; Watego 2021). Contemporary child protection discourse positions removal as a necessary response to “risk,” yet a growing body of Indigenous scholarship demonstrates that these deficit and risk framings frequently misinterpret poverty, structural disadvantage, and cultural difference as parental failure (Kukutai and Taylor 2016; Walter and Carroll 2020; Griffiths et al. 2021; Trudgett et al. 2022). Consequently, First Nations children continue to experience disconnection from family, community, identity, and Country—harmful outcomes extensively documented in historical inquiries and reinforced in recent evidence (R. Wilson 1997; Bamblett and Lewis 2007).

This article undertakes a First Nations-centred narrative review to critically examine the systemic, structural, and cultural drivers underpinning First Nations over-representation in OOHC. Guided by First Nations Standpoint Theory (Moreton-Robinson 2015), relational research paradigms (Walter et al. 2017; S. Wilson 2008), and decolonising methodologies (Tuhiwai Smith 2021), the review foregrounds Indigenous knowledge systems, community testimony, and Aboriginal community-controlled research (ACCO). The methodology incorporates interdisciplinary scholarship across law, criminology, sociology, public health, Indigenous studies, and education, together with empirical research, policy documents, community submissions, and grey literature produced by First Nations organisations. This approach responds directly to critiques that much child protection scholarship marginalises Indigenous perspectives or treats Indigenous experience merely as “data,” rather than as sovereign intellectual authority (Carlson and Frazer 2021; Janke and Dawson 2020; Janke 2019).

The scope of this review examines the historical continuities between colonisation, assimilation, institutionalisation, and contemporary child protection practices, demonstrating that OOHC continues to operate as a mechanism of state governance over Indigenous life (Atkinson 2002; Watego 2021). It explores macro-level structural determinants—including structural racism, Indigenous data injustice, socioeconomic exclusion, cultural displacement, and intergenerational trauma—alongside micro-level factors such as parental mental health, substance use, family violence, and the heightened vulnerability of Indigenous children in care (Atkinson et al. 2014; Roach and McMillan 2022; AIHW 2023). The review also critically examines issues of placement, permanency, cultural rights, and the failure of statutory systems to meaningfully implement the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (ATSICPP). Central to this analysis is the work of Janke (2019) on Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) rights, which frames cultural identity and connection as legally and culturally protected, rather than optional “add-ons” within OOHC practice.

Finally, the article synthesises evidence demonstrating the transformative potential of Indigenous governance in child and family services, including the successes of Aboriginal Community-Controlled Organisations (ACCOs), on-Country models, culturally grounded early intervention programs, and community-led decision-making structures (Swan and Swan 2023; SNAICC 2024; Beaufils et al. 2024). The persistent failures of state systems to meet even minimal cultural safety standards underscore the urgency of structural reform grounded in Indigenous sovereignty, cultural rights, and community authority. The review concludes by identifying key priorities for change and outlining pathways for restoring cultural continuity, strengthening family-led decision-making, and embedding First Nations governance at every level of the OOHC system.

2. Methodology & Theoretical Positioning

This narrative review implements a relational First Nations Standpoint and decolonising research orientation, that centres Indigenous sovereignty, relationality, and lived experience as foundational sources of knowledge. First Nations Standpoint Theory, articulated by Moreton-Robinson (2013, 2015), is expanded through Indigenous feminist and relational scholarship, asserting that knowledge production is inherently political and that Indigenous peoples possess distinct and sovereign intellectual traditions. In applying this standpoint, the analysis begins from the lived realities, cultural frameworks, and collective authority of First Nations peoples, recognising that only through privileging Indigenous perspectives can the systemic and structural conditions of removal systems, specifically OOHC, can be fully understood (Carlson 2016; Martin 2017).

Aligned with this positioning, the review draws on relational and decolonising research paradigms that foreground principles of respect, responsibility, relational accountability, and cultural governance (S. Wilson 2008; Tuhiwai Smith 2021). These paradigms reject extractive, deficit-oriented knowledge production and instead emphasise relationships with community, Country, and culture as integral to ethical inquiry.

The methodology integrates a First Nations-centred narrative review, synthesising interdisciplinary literature from law, criminology, sociology, social work, Indigenous studies, public health, psychology, and human rights. This includes peer-reviewed academic publications, quantitative and qualitative empirical studies, policy evaluations, and government inquiries. Importantly, it also incorporates grey literature and community-controlled texts, such as reports from SNAICC, Aboriginal Community-Controlled Organisations (ACCOs), the Productivity Commission, peak bodies, community submissions, and digital testimonies from frontline First Nations workers and care leavers. This wider evidentiary landscape is essential, given the chronic under-representation of Indigenous-led research in mainstream scholarship and the structural barriers that limit Indigenous authorship within academic and policy discourse (Griffiths et al. 2016, 2021).

In centring Indigenous knowledge systems, the review treats Indigenous cultural rights, data sovereignty, and community governance as methodological commitments rather than background considerations. Janke’s (2019) Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) principles guide the treatment of cultural knowledge and emphasise collective authorship, communal ownership, and culturally informed interpretation. Similarly, the application of Indigenous Data Sovereignty frameworks, as articulated by Griffiths et al. (2021), Maiam nayri Wingara (2022), and K. Wilson (2023) ensure that evidence is contextualised within First Nations governance structures and avoids reproducing deficit narratives embedded in state-generated datasets.

The narrative review approach is particularly suited to Indigenous-centred inquiry because it allows for the integration of multiple forms of knowledge—including community testimony, intergenerational experience, oral accounts, and service-based insights—while also critically interrogating mainstream policy frameworks and empirical claims. This method recognises that OOHC research has historically been dominated by non-Indigenous voices and institutions, often privileging quantitative metrics over Indigenous worldviews or explanations of harm. By drawing from First Nations scholarship, survivor testimony, and interdisciplinary data, this review seeks to reframe OOHC as not merely a child welfare issue but as an expression of structural power, racial governance, and enduring colonial state control.

Through this methodological and theoretical foundation, the review positions First Nations voices not as supplementary perspectives but as the primary analytical authority. This approach challenges the epistemic dominance of Western research traditions in the field of child protection and ensures that the analysis remains accountable to the communities whose experiences and rights are at stake. Ultimately, this standpoint-guided methodology provides a robust and culturally grounded foundation for examining the systemic conditions that continue to shape the over-representation of First Nations children in OOHC.

3. Historical and Structural Foundations of OOHC in Australia

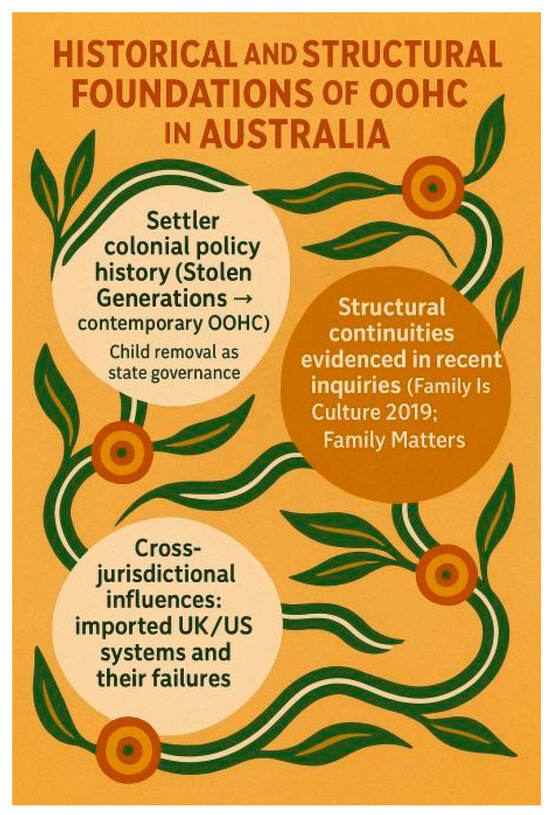

The contemporary operation of Out-of-Home Care (OOHC) in Australia cannot be understood without situating it within the long arc of settler-colonial child governance. Since the early 19th century, Australian authorities have used child removal as a mechanism of social control, racial management, and cultural assimilation (See Figure 1). These practices intensified throughout the 20th century, culminating in the policies documented in the Bringing Them Home (R. Wilson 1997) report, which found that the forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children constituted a gross violation of human rights and resulted in enduring intergenerational harms. Although the language and structure of child welfare systems have since changed, the foundational logics of surveillance, deficit-based assessments, and state paternalism remain embedded in contemporary OOHC systems (Davis 2019; R. Wilson 1997; Beaufils et al. 2024, 2025; Beaufils 2025).

Figure 1.

Historical and Structural Foundations of OOHC.

The structural continuities between historical and contemporary child removal are well documented. Megan Davis’ Family Is Culture Review (Davis 2019) exposed that NSW child protection decisions continue to treat Indigenous identity as a risk factor and frequently disregard the legislated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (ATSICPP). The review found persistent racialised assumptions about parenting capacity, over-surveillance of Aboriginal families, and systemic failure to prioritise cultural connection. Similarly, repeated findings from the Family Matters reports (SNAICC 2024) demonstrate that the conditions enabling the Stolen Generations—poverty, discrimination, inadequate housing, punitive welfare systems, and systemic racism—continue to shape the contemporary policy environment. These findings reveal that what is often framed as “modern child protection” reproduces earlier colonial structures under new administrative arrangements.

Australian OOHC has also been profoundly shaped by cross-jurisdictional policy ‘borrowing’, primarily from the United Kingdom and the United States. These systems adopted child protection models prioritising forensic investigation, rapid risk assessment, and legal intervention over relational support and family strengthening (Gilbert et al. 2012). As Price-Robertson et al. (2014) note, the transplantation of UK/US-style statutory frameworks into Australia entrenched a reactive, punitive orientation rather than community-led or prevention-focused approaches. These imported models were never designed for Indigenous families, nor were they grounded in Indigenous concepts of kinship, relational accountability, or collective caregiving (Bamblett and Lewis 2007). Instead, they imposed Eurocentric notions of “good parenting,” individual responsibility, and state-defined permanency—norms that continue to shape NSW’s OOHC system today.

Additionally, neoliberal reforms of the 2000s and 2010s accelerated the outsourcing and privatisation of OOHC services, transferring responsibility from government to a mixed market of NGOs. While some Aboriginal Community-Controlled Organisations (ACCOs) have achieved significant progress within this landscape, they remain structurally constrained by state funding models, bureaucratic compliance regimes, and legislative authority that remains firmly in government hands. These dynamics reproduce what Moreton-Robinson (2015) describes as the white possessive logics of the state—ongoing attempts to manage, contain, and define Indigenous lives within non-Indigenous frameworks of governance.

Importantly, contemporary research shows that these structural legacies result not only in over-representation but also in qualitatively different experiences of OOHC for First Nations children. Recent studies emphasise fails of predicted risk and cultural disconnection—through placement with non-Indigenous carers, limited contact with family, and absence of cultural planning—directly harms identity formation, mental health, and social belonging (Krakouer 2018; Krakouer et al. 2021). Similarly, international evidence indicates that Indigenous children across Canada, Aotearoa New Zealand, and the United States experience disproportionate removal due to structural inequalities, not parental action, confirming the global pattern of Indigenous over-policing in family welfare systems (Fallon et al. 2013; Palmater 2018).

Overall, this section demonstrates that contemporary OOHC is not merely a service system but a continuation of the colonial governance structures that have long shaped the lives of First Nations families. The system’s historical foundations—cultural assimilation, racialised judgments, state paternalism, and imported foreign models—continue to inform today’s risk assessments, placement practices, and permanency decisions. Understanding these continuities is essential for any meaningful transformation of OOHC policy, governance, and practice, particularly within NSW, where First Nations children remain the most disproportionately represented in the country.

4. Macro-Level Structural Drivers

The over-representation of First Nations children in Out-of-Home Care (OOHC) cannot be accounted for by individual or family factors alone. A substantial body of Indigenous-led research demonstrates that macro-level structural conditions—shaped by colonisation, racialised governance, social inequality, and injustice—play a decisive role in producing the conditions under which child removal occurs (Watego 2021). These structural determinants are neither accidental nor neutral; they constitute an entrenched architecture of state power that continues to regulate, surveil, and intervene in the lives of First Nations families. Understanding these macro forces is essential for transforming the systemic drivers of OOHC.

A central structural determinant is structural racism, which shapes how Indigenous families are perceived, monitored, and responded to by state agencies. As Watego (2021) argues, racism is not episodic but “structural and saturating,” embedded in the everyday practices of policing, welfare assessments, risk thresholds, and service provision. In the OOHC context, this manifests through disproportionate reports to child protection, lower thresholds for statutory intervention, discriminatory assumptions about Indigenous parenting, and persistent failures to recognise the strengths of kinship and extended family systems (Carlson and Frazer 2021; Bamblett and Lewis 2007; Warren et al. 2024). Racialised governance within child protection systems, is an that Indigenous families experience of constant state involvement, not as support but as surveillance and punishment—an extension of colonial governance rather than a neutral welfare process.

Another critical structural factor is Indigenous data injustice, which influences how risks are classified, how decisions are justified, and how accountability is monitored. Griffiths et al. (2021) demonstrates that state-generated child protection data often reproduces deficit narratives, positioning Indigenous families as inherently vulnerable or dysfunctional. Risk assessment tools used in many Australian jurisdictions rely on variables that correlate strongly with structural disadvantage—poverty, housing instability, and contact with police—leading to algorithmic and procedural biases that disproportionately label Indigenous families as “high risk.” The absence of Indigenous Data Sovereignty frameworks exacerbates these injustices by denying First Nations communities’ authority over the interpretation, use, and governance of data produced about them (K. Wilson 2023).

Socioeconomic inequality remains a profound structural driver of child protection involvement. Poverty, deprivation, and social exclusion are frequently mischaracterised as parental neglect, even when families are attempting to meet children’s needs within structurally constrained conditions (AIHW 2023; Walter and Carroll 2020). Beaufils et al. (2025) argues that many child protection interventions are in fact responses to state-produced inequities, including inadequate housing, limited access to healthcare, insecure employment, and systemic under-investment in Aboriginal communities. Rather than addressing these inequalities, statutory systems often penalise families for the consequences of structural harm. For Indigenous families in NSW, where housing shortages, remote service access, and economic marginalisation are widespread, these structural inequities significantly elevate child protection contact.

Cultural disruption and identity harm also operate as macro-level drivers. Colonisation has systematically undermined Indigenous child-rearing systems, kinship obligations, language transmission, and community governance, creating conditions in which cultural continuity becomes difficult to sustain (Krakouer 2018). Contemporary OOHC practices often fail to support cultural identity or recognise culture as protective, despite extensive research showing that cultural connection strengthens wellbeing, resilience, and long-term outcomes for Indigenous children (Krakouer 2018; SNAICC 2024). The erosion of cultural authority contributes to a cycle in which families are judged against Western norms while the cultural foundations that support Indigenous child-rearing are systematically undermined.

Finally, macro-level drivers are reinforced through policy design, neoliberal outsourcing, and hierarchical placement systems. Gilbert et al. (2012) highlight how imported UK/US child protection models favour forensic investigation over prevention, creating a system that responds to crisis rather than structural need. In NSW, the outsourcing of OOHC to NGOs has generated a fragmented, compliance-heavy system in which Aboriginal Community-Controlled Organisations (ACCOs) remain structurally disadvantaged despite producing better outcomes for children (SNAICC 2024). However the proportion of funding allocation to ACCOs in NSW, similarly in other states and territories, is only 6.38% (SNAICC 2025). Placement hierarchies prioritise non-Indigenous foster care and long-term guardianship orders, often at the expense of restoration, kinship placements, and community-led supports (Davis 2019). The result is a system that reproduces colonial power structures under the guise of modern policy frameworks.

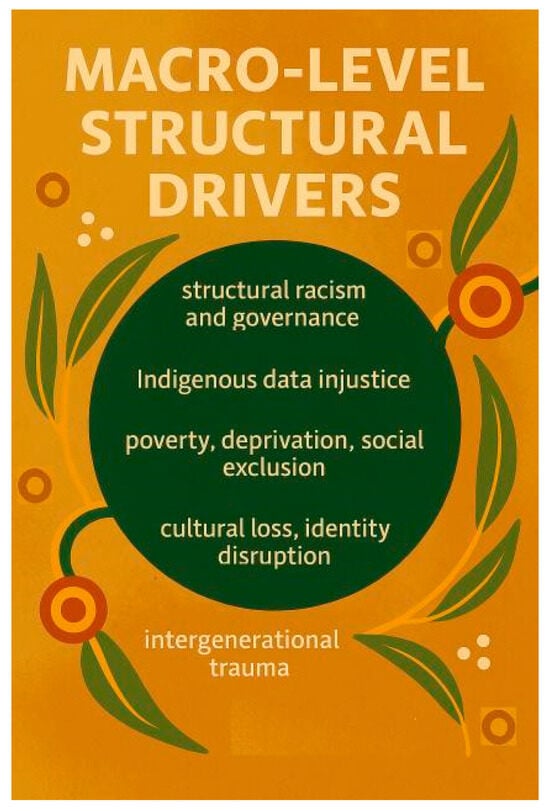

Taken together, these macro-level structural drivers reveal that First Nations over-representation in OOHC is not an artefact of parental behaviour but a predictable outcome of racialised policy environments, entrenched inequalities, and systemic failures to uphold Indigenous cultural rights and governance (See Figure 2). Without addressing these structural conditions, reforms focused solely on family-level interventions will continue to produce inequitable outcomes and perpetuate cycles of state intervention.

Figure 2.

Macro-Level Structural Drivers.

5. Micro-Level Drivers Affecting First Nations Entry and Experience in OOHC

Micro-level drivers refer to the immediate, individual and family-level circumstances that influence children’s involvement with statutory systems. While these factors are often framed through a deficit lens—emphasising parental behaviour or “risk”—a substantial body of Indigenous scholarship has demonstrated that these micro-level concerns cannot be separated from the structural violence and systemic racism described in Section 4 (Carlson and Frazer 2021; Watego 2021). This section presents a critical overview of the most prominent micro-level drivers cited in contemporary research: parental mental health, substance misuse, family violence, child wellbeing, and the pathways that lead First Nations children from care into the criminal justice system.

5.1. Parental Mental Health

Parental mental health is frequently identified as a factor in child protection interventions, yet standard diagnostic narratives often ignore the colonial determinants shaping First Nations emotional and psychological distress (Dudgeon et al. 2020). Mental health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is relational, collective and grounded in land, culture and community rather than individual pathology (Jackson Pulver et al. 2019). Consequently, conditions such as depression, anxiety or complex trauma cannot be understood outside the impacts of dispossession, over-policing, loss of culture, and intergenerational child removal (Atkinson 2002).

Research across NSW has found that First Nations families experiencing mental health challenges are more likely to be categorised as presenting “neglect risk,” often without culturally appropriate assessments or supports (AIHW 2023). Moreover, caseworkers frequently interpret trauma-related behaviours through Western clinical frameworks, contributing to escalated statutory involvement rather than culturally grounded healing supports.

5.2. Substance Misuse

The relationship between substance misuse and OOHC is similarly shaped by colonial conditions. While alcohol and drug use is often cited as a reason for removal, the drivers of substance use—intergenerational trauma, poverty, housing stress, and grief—are routinely downplayed or ignored (Parisi et al. 2019). As Wundersitz (2010) and more recent analyses show, substance misuse often co-occurs with experiences of violence, unresolved trauma, or lack of culturally safe mental health care.

First Nations scholars and health leaders, including Roach and McMillan (2022), highlight that substance misuse cannot be separated from systemic failures that limit access to culturally informed AOD support, remove children prematurely, and escalate harm through punitive surveillance models. Removal in these contexts often breaks kinship networks that could otherwise support recovery.

5.3. Family Violence

Family violence is consistently raised in substantiated cases, but public policy frequently reduces it to individual pathology rather than a colonial problem (Cripps and Habibis 2019). Indigenous women experience violence at disproportionately high rates, not because of cultural failings—as racist narratives imply—but because of systemic drivers including police inaction, poverty, housing precarity, and the legacies of child removal (Carlson and Frazer 2021).

Cripps (2023) argues that statutory systems often respond to Indigenous women as “failed protectors,” punishing victims by removing their children rather than addressing the violence itself. This dynamic compounds trauma and reinforces systemic mistrust. For many mothers, fear of child removal prevents disclosure of violence and access to services (Davis 2019, 2021).

5.4. Child Wellbeing

Children in OOHC experience disproportionately high rates of developmental delay, mental health needs, and health conditions when compared to their non-Indigenous peers (Raman et al. 2011). However, First Nations child wellbeing must be understood holistically—connection to Country, spirituality, ancestors, kinship and identity are foundational determinants of wellbeing (Biles 2024).

Western developmental frameworks embedded in NSW policy often pathologize normal cultural practices—such as communal parenting, mobility between households, or extended-kin caregiving—leading to inappropriate assessments of “risk” or “instability” (Martin 2017). These misinterpretations can result in First Nations children being placed in non-Indigenous settings, further undermining their wellbeing by severing cultural continuity.

5.5. The “Crossover Child” Pathway

One of the most concerning micro-level phenomena is the pathway from OOHC into the criminal justice system, commonly described as “crossover” or “care criminalisation.” McFarlane (2017) and Gerard et al. (2018) has shown that First Nations children in OOHC are far more likely to be charged for behaviours that would not attract police intervention in family homes—such as property damage, absconding, or verbal outbursts. This “institutionalisation of normal childhood behaviour” reflects structural racism embedded within residential care models.

Recent analyses confirm that crossover is driven not by inherent behavioural issues but by systemic responses, lack of cultural support, placement instability, and the criminalisation of trauma (Sentencing Council of New South Wales 2022). The crossover pathway represents one of the most harmful outcomes of contemporary OOHC, contributing directly to the over-representation of First Nations youth in detention.

5.6. Limitations of Individual-Risk Framings

Across all micro-level factors, a consistent critique emerges; individualising the “problem” obscures the structural causes and risk. Risk frameworks that focus solely on parents’ deficits serve to absolve the state of responsibility for poverty, inadequate housing, racism, or social exclusion. Individual-level assessments often ignore community strengths, kinship resilience, and protective cultural factors, leading to removal decisions that reinforce, rather than mitigate, harm (See Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Micro-Level Drivers.

A holistic, relational approach—guided by First Nations governance and worldviews—requires shifting from surveillance and deficit-thinking toward collective healing, cultural authority, and community-controlled care.

6. Placement, Permanency, and Cultural Rights in OOHC

The placement and permanency architecture of the NSW Out-of-Home Care (OOHC) system remains one of the most significant structural determinants shaping the experiences and outcomes of First Nations children. This section critically examines the role of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (ATSICPP), the entrenched shortcomings of non-Indigenous placements, the tension between permanency orders and restoration, and the centrality of cultural rights—including Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP)—in ensuring children’s wellbeing. Recent research further emphasises the importance of embedding children’s voices in decisions that affect them, particularly given the growing body of evidence showing the harms associated with cultural disconnection (Burns 2024; Garvey et al. 2024).

6.1. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (ATSICPP)

ATSICPP remains the core legislative and policy mechanism designed to protect cultural continuity for First Nations children. It outlines a clear hierarchy prioritising placement with family, kin, community, and other Aboriginal carers before any non-Indigenous arrangement. Despite being embedded in legislation across all Australian jurisdictions, reality and evidence continues to show persistent and widespread non-compliance with the principle, with only 37% of Aboriginal children nationally placed with Indigenous carers in 2023 (SNAICC 2024).

The Family Is Culture (Davis 2019) review demonstrated that non-compliance is not random but reflects deeper structural problems: inconsistent assessments of kinship, inadequate funding for Aboriginal Community-Controlled Organisations (ACCOs), racialised assumptions about “safety,” and the systemic privileging of non-Indigenous foster carers. Renewal of ATSICPP must therefore be understood not merely as a policy adjustment but as a fundamental requirement for upholding cultural rights and ensuring self-determination in child welfare systems.

6.2. Shortcomings of Non-Indigenous Placements

Non-Indigenous placements remain the dominant placement pathway for First Nations children, despite strong evidence of harm. Studies have consistently found that such placements increase the risk of cultural disconnection, identity fragmentation, and long-term psychological distress (Krakouer 2018; Beaufils 2023). Non-Indigenous carers often lack cultural capability, and many do not receive the training or community support necessary to maintain a child’s cultural identity.

Non-Indigenous placements also frequently fail to provide sustained contact with families and community networks, further undermining connection to culture, kinship, and Country. Janke’s (2019) Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) framework underscores that cultural identity is collective and relational; it cannot be reproduced through tokenistic gestures or superficial engagement with culture. When cultural authority is absent from caregiving environments, long-term developmental outcomes are compromised.

6.3. Permanency Orders Versus Restoration

Permanency planning reforms introduced in NSW in 2015 have had profound impacts on First Nations families. These reforms accelerated timelines for adoption, guardianship, and long-term care orders while narrowing the window for restoration. Davis (2019) argues that these policies operate as a contemporary iteration of removal logic, emphasising speed and administrative certainty over cultural continuity and family reunification.

Evidence from the NSW Pathways of Care Longitudinal Study (POCLS) shows that First Nations children are less likely to be reunified and more likely to remain in long-term placements compared with non-Indigenous children (AIHW 2023). This disparity persists even when restoration is culturally desirable and potentially safe. Research has highlighted four barriers: limited culturally informed assessments, inadequate supports for parents during restoration attempts, inconsistent casework quality, and structural racism that pathologizes First Nations parenting (Goldingay et al. 2024).

A shift toward relational and community-led restoration is increasingly advocated by scholars and ACCOs, who argue that restoration should be the default pathway—not an exception.

6.4. Cultural Rights and ICIP Frameworks

Cultural rights are not supplementary to child wellbeing; they are central determinants of wellbeing for First Nations children. Janke’s (2019) True Tracks framework articulates that cultural identity, stories, kinship obligations, and cultural authority are forms of ICIP and must be recognised, respected, and protected within any caregiving environment. This aligns with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which asserts children’s rights to maintain, practise, and revitalise their cultures.

The failure to embed cultural rights in OOHC placements constitutes both a systems failure and a cultural rights violation. Cultural authority must therefore be positioned as a governing principle in placement decisions, case planning, and restoration assessments—not as an optional consideration.

6.5. Children’s Voices and Indigenous Ethics of Listening

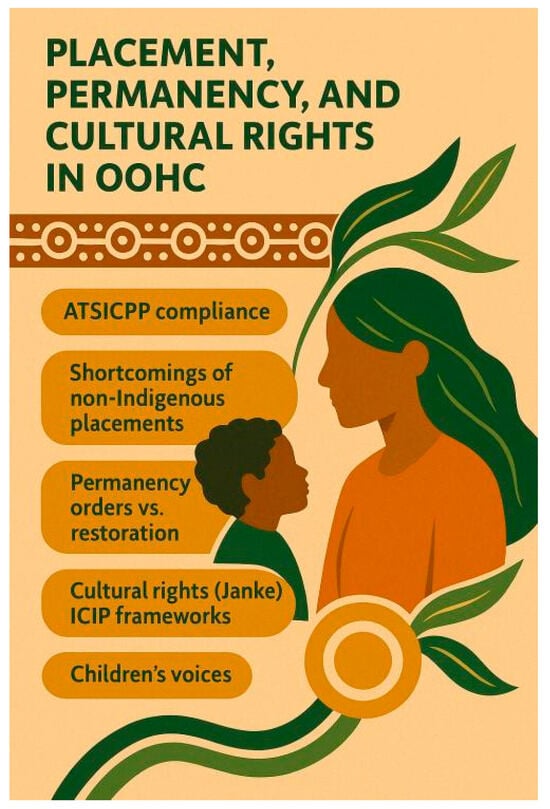

Emerging evidence highlights the importance of centring the voices of First Nations children and young people in care (See Figure 4). Burns (2024) and Garvey et al. (2024) demonstrate that young people consistently articulate the importance of kinship, connection, belonging, and cultural identity, often in contrast to the priorities of statutory agencies. Listening to children requires more than consultation; it requires adherence to Indigenous ethical frameworks of deep relational listening, reciprocity, and accountability.

Figure 4.

Placement, Permanency & Cultural Rights in OOHC.

The systematic exclusion of children’s voices is a key driver of poor outcomes. When children’s expressed desires for family, culture, or connection are disregarded, statutory systems reproduce colonial harms. Embedding Indigenous ethics of listening is therefore integral to any genuine reform approach.

7. Key Priorities for Transformation

Transforming the OOHC system for First Nations children requires a fundamental shift away from deficit-based, crisis-driven statutory responses and toward governance models grounded in culture, community authority, and relational accountability. The persistence of over-representation, the failure of ATSICPP compliance, and the deep cultural harms caused by non-Indigenous placements illustrate that incremental reforms have been insufficient. This section outlines the key priorities emerging from the literature, First Nations scholarship, community testimonies, and recent inquiries.

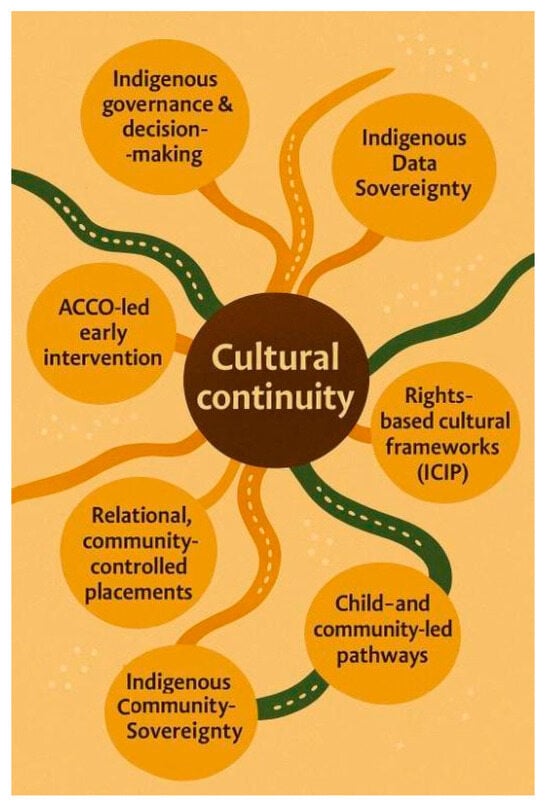

7.1. Centring Child Needs Through Cultural Continuity

Research consistently demonstrates that cultural continuity is a core determinant of wellbeing for First Nations children (Beaufils 2023; SNAICC 2024). Cultural identity is not an optional supplement to safety; it is a foundational requirement. The evidence shows that when children are placed away from kin, Country, language, and cultural authority, they experience higher rates of disconnection, mental health distress, identity fragmentation, and contact with the justice system (Burns 2024; Krakouer 2018).

Transformation therefore requires embedding cultural continuity at all levels of decision-making, including early intervention, kinship assessment, case planning, and permanency. This means restoring community authority in defining what constitutes safe, culturally authentic care—beyond Western developmental markers alone.

7.2. Indigenous Governance and Decision-Making Authority

Recent literature identifies Indigenous governance as the most urgent structural reform priority. Self-determined governance is not an “add-on” but the core mechanism through which systems become genuinely culturally safe. Without governance authority, ACCOs remain constrained by state-defined funding, compliance, and casework structures that replicate colonial power.

Indigenous governance includes legislated decision-making authority for ACCOs, community-led case consultations, and oversight bodies with cultural jurisdiction. Internationally, comparative studies from Canada and Aotearoa New Zealand show that when Indigenous communities hold authority over child welfare decisions, removal rates fall and restoration increases.

Transformation therefore requires shifting from participation to genuine authority.

7.3. ACCO-Led Early Intervention and Prevention

Evidence from the Family Matters (SNAICC 2024) report highlights that ACCO-led early intervention is the most effective protective factor against child removal. ACCOs provide culturally grounded supports—holistic family strengthening, healing programs, kinship mapping, and community-based responses to violence—that target structural, not individualised, drivers.

Yet ACCOs currently receive a fraction of total OOHC and prevention funding, even though they deliver better outcomes for families and children (SNAICC 2024). Redressing this imbalance requires targeted, long-term investment in ACCO service infrastructure, workforce development, and cultural healing models. Without this shift, early intervention will remain fragmented and reactive.

7.4. Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Accountability

Access to data that accurately reflects community experience is critical for transforming the system. State-held child protection data is often produced through colonial logics, obscuring structural drivers and reproducing harm (K. Wilson 2023). Indigenous Data Sovereignty requires that First Nations peoples govern the collection, interpretation, and use of all data affecting their children. This shift would transform accountability by providing:

- community-controlled monitoring of ATSICPP compliance

- transparent reporting on placement decisions

- better identification of systemic racism

- evidence for targeted, culturally grounded reform

Embedding Indigenous data governance is therefore essential to systemic transformation.

7.5. Relational and Community-Controlled Placements

A priority across all scholarship is shifting placements from transactional, case-managed models to relational, community-controlled approaches that foreground kinship systems (See Figure 5). Placement stability is not just about continuity of carers; it is about continuity of relationships, cultural authority, and community accountability (Janke 2019; Beaufils 2023). Community-controlled placements require:

Figure 5.

Priorities for Transformation: Cultural Continuity.

- kinship-first models

- cultural authority in caregiver training

- ongoing family contact as a non-negotiable

- restoration as the preferred approach

- placements on or connected to Country

This relational framework reflects Indigenous conceptions of care as collective, intergenerational, and embedded in Country—not as an individualised responsibility.

8. Voices from the Field

Meaningful transformation of the OOHC system requires centring the lived experiences, knowledge, and authority of those who are most affected—First Nations families, Elders, community leaders, frontline workers, and young people who have lived in care. These voices reveal, with consistency across decades of inquiries, the systemic harms and failures that statistical analyses alone cannot capture. While governments often frame these accounts as “anecdotal,” Indigenous scholarship emphasises that lived experience is a form of sovereign knowledge that exposes the everyday operations of power and its effects on families (Carlson and Frazer 2021; Jackson Pulver et al. 2019). This section synthesises key themes from testimonies, inquiries, community submissions, and qualitative research that centre First Nations voices.

8.1. Frontline Workers: Professional Witnesses to Systemic Harm

Frontline Aboriginal workers—particularly those in ACCOs, family support programs, health services, and on-Country programs—consistently describe systems that mistake poverty for parental neglect, misinterpret cultural practices, and fail to invest in relational support (SNAICC 2024). Child protection engagement often begins through over-surveillance rather than support, with mandatory reporting settings such as schools, hospitals, and police amplifying racialised assumptions about danger and dysfunction.

Workers also describe the systemic disregard for their cultural expertise. First Nations workers frequently provide the most culturally grounded assessments and recommendations, yet their advice is deprioritised in favour of non-Indigenous professional judgments (Corrales et al. 2025). This undermines cultural authority and erodes opportunities for culturally legitimate decision-making.

8.2. Elders and Community Knowledge Holders: Cultural Authority Silenced

Elders play central roles in defining safety, relational obligations, kinship responsibilities, and cultural identity for First Nations children (Beaufils 2023). Yet across NSW inquiries, Elders repeatedly report being marginalised or excluded from formal decision-making processes (Davis 2019). Many describe cultural safety meetings that are rushed, tokenistic, or conducted without community consultation.

Janke’s (2019) ICIP framework emphasises that cultural authority is collective, intergenerational, and grounded in Country, yet statutory systems continue to treat it as optional “cultural advice.” Elders identify this marginalisation as a key reason why cultural continuity breaks down within OOHC, with deep consequences for children’s sense of belonging and identity.

8.3. Parents: Experiences of Surveillance, Punishment, and Disempowerment

Parents’ testimonies highlight the emotional, cultural, and structural violence embedded within removal processes. Common themes include:

- fear of engaging with services due to the risk of removal

- experiences of racism and dehumanisation

- poor communication and lack of culturally safe support

- unrealistic reunification timelines

- coercive relationships with caseworkers

The Family Is Culture Review (Davis 2019) documented numerous cases in which parents felt set up to fail, with minimal access to therapeutic support despite clear evidence of trauma. Parents repeatedly describe restoration pathways that feel punitive rather than supportive, with decisions made without transparency or cultural accountability (Garvey et al. 2024).

8.4. Young People: The Lived Reality of Disconnection

Young people with lived experience of OOHC consistently articulate the harms of cultural disconnection, instability, and exclusion from decision-making. Recent studies show that First Nations young people describe:

- feeling isolated in non-Indigenous placements

- wanting more contact with family, siblings, and community

- needing cultural mentors and guidance

- being moved frequently without explanation

- experiencing racism in placement settings

- being criminalised for trauma-related behaviours

Burns (2024) and Garvey et al. (2024) highlight that young people want connection—to kin, culture, Country, and identity—and that placement environments rarely support this. Their testimonies challenge the assumption that “stability” is achieved through long-term placement alone; instead, stability is relational, cultural, and grounded in belonging.

8.5. Failures of Consultation and the Impact on Trust

A recurring theme across voices is the persistent failure of government agencies to consult meaningfully with First Nations people. Consultation is often conducted late in the process—after removal decisions are made—or is limited to procedural meetings with minimal authority to influence outcomes (Swan and Swan 2023). This reinforces mistrust and retraumatisation.

Recent scholarship on Indigenous governance frameworks emphasises that consultation without authority reproduces colonial power. For many families, the experience of child protection involvement is not one of “support” but of surveillance, judgment, and the extraction of their cultural stories without consent.

8.6. Pathways to Restoration and Healing: Community-Led Solutions

Despite systemic failings, the voices from the field highlight clear, actionable pathways toward transformation. Families, Elders, workers, and young people consistently call for:

- Aboriginal-led decision-making

- family-led restoration plans

- trauma-informed, culturally grounded healing supports

- investment in ACCO-led early intervention

- on-Country programs and kinship-first placements

- stronger recognition of cultural rights in legal processes

These pathways align with international evidence showing that Indigenous-led systems result in lower removal rates and better long-term outcomes. At their core, these testimonies reveal that meaningful reform must shift authority to community-controlled structures that uphold cultural sovereignty and relational accountability.

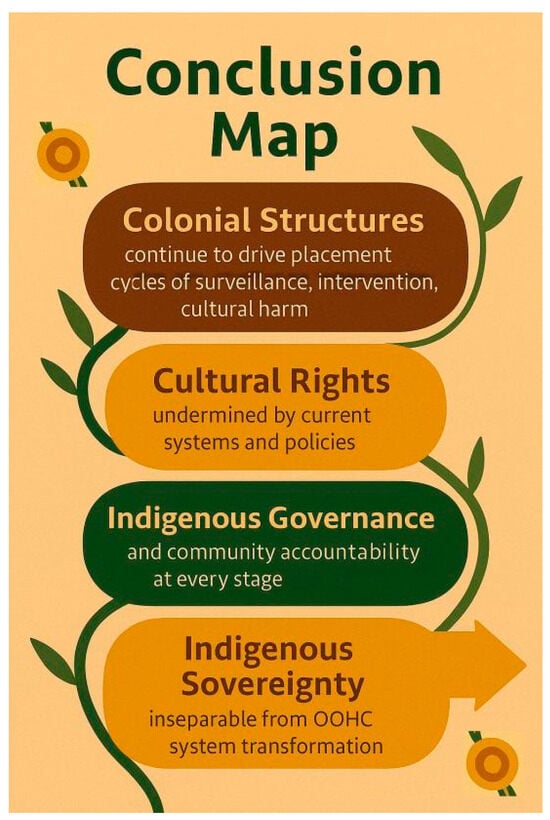

9. Conclusions

The persistent over-representation of First Nations children in Out-of-Home Care (OOHC) is not an aberration but a predictable outcome of long-standing colonial structures that continue to shape the operations of child protection systems in Australia (Figure 6). Across the historical, structural, and contemporary evidence examined in this review, a clear through-line emerges: the systems tasked with caring for First Nations children have instead reproduced cycles of surveillance, racialised intervention, cultural disruption, and relational harm. These outcomes arise from macro-level determinants such as structural racism, Indigenous data injustice, and socioeconomic inequality, as well as micro-level drivers related to trauma, violence, and service exclusion—drivers that are themselves deeply shaped by colonial histories and contemporary policy failures.

Figure 6.

Sovereign Childhood: Conclusion Map.

The analysis demonstrates that current placement and permanency frameworks in NSW continue to undermine children’s cultural rights and relational identities. Despite legislative protections such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle, compliance remains inconsistent and often superficial. Too many First Nations children are placed in non-Indigenous settings where cultural connection is treated as optional, and permanency orders continue to prioritise administrative efficiency over restoration, healing, and cultural continuity. These practices are not neutral; they reflect a system that persistently privileges Western frameworks of safety, risk, and care at the expense of Indigenous sovereignty and cultural authority.

The voices from the field—Elders, frontline workers, parents, and young people—underscore these systemic failures with clarity and urgency. Their testimonies reveal the emotional, cultural, and structural violence embedded in current child protection practices, as well as the profound harm caused by disconnection from kin, culture, and Country. Yet these voices also illuminate clear pathways forward. Families and communities consistently articulate the need for community-led decision-making, culturally grounded supports, ACCO-led early intervention, relational healing, and governance arrangements that honour Indigenous cultural authority.

The evidence presented across this review points toward a singular, overarching conclusion: meaningful transformation of the OOHC system cannot occur without a fundamental redistribution of power. Reform cannot be reduced to procedural improvement or new compliance targets; it must involve a structural shift toward Indigenous governance, community-controlled accountability, and cultural authority at every stage of the system. Embedding Indigenous Data Sovereignty principles, strengthening ACCO infrastructure, ensuring kinship-first placement pathways, and legislating Indigenous-led decision-making bodies are not reforms on the margins—they are the necessary conditions for a system that protects, rather than harms, First Nations children.

Ultimately, transforming OOHC is inseparable from broader movements toward Indigenous sovereignty, cultural resurgence, and relational justice. A system that truly supports First Nations children must be grounded in the realities of their lives: their kinship networks, their cultural identities, their communities, and their rights to self-determination (Beaufils et al. 2024). The path forward requires not incremental adjustments but a paradigm shift toward a child and family system designed, led, and governed by First Nations peoples. Only then can Australia begin to break the cycles of removal and build a future where First Nations children grow up safe, loved, connected, and strong in culture.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Open access publishing facilitated by Jumbunna and the University of Technology Sydney. Thank you to the communities for leading the way in this space and continuing to care right way. To the team at Jumbunna for the support and tough conversations. To mingaan for the guidance and finally, my wife and son for the grounding and purpose.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- AIHW. 2023. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle indicators 2023; Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- Atkinson, Judy. 2002. Trauma Trails, Recreating Song Lines: The Transgenerational Effects of Trauma in Indigenous Australia. Victoria: Spinifex Press. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Judy, Jeff Nelson, Robert Brooks, Caroline Atkinson, and Kelleigh Ryan. 2014. Addressing individual and community transgenerational trauma. In Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, 2nd ed. Edited by Pat Dudgeon, Helen Milroy and Roz Walker. Sydney: Commonwealth of Australia, pp. 373–82. Available online: https://www.telethonkids.org.au/globalassets/media/documents/aboriginal-health/working-together-second-edition/wt-part-4-chapt-17-final.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Bamblett, Muriel, and Peter Lewis. 2007. Detoxifying the child welfare system. First Peoples Child & Family Review 3: 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Beaufils, James. 2023. ‘That’s the bloodline’: Does Kinship and care translate to Kinship care? Australian Journal of Social Issues 58: 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaufils, James. 2025. First Nations Child Removal and New South Wales Out-of-Home Care: A Historical Analysis of the Motivating Philosophies, Imposed Policies, and Underutilised Recommendations. Genealogy 9: 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaufils, James, Deborah Swan, and Tatiana Corrales. 2025. “They know what’s best for the poor little black fellows, like they did all them years ago”: Continued paternalism and pressure to place. Australian Journal of Social Issues 60: 876–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaufils, James, Jacynta Krakouer, Lease Kelly, Michelle Kelly, and Dana Hogg. 2024. “We all grow up with our mob because it takes all of us”: First Nations collective kinship in Australia. Children and Youth Services Review 169: 108059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biles, Brett, Serova Nina, Stanbrook Gavin, Brady Brooke, Kingsley Jonathan, Topp Stephanie, and Yashadhana Arvati. 2024. What is Indigenous cultural health and wellbeing? A narrative review. The Lancet Regional Health–Western Pacific 52: 101220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Burns, Bradley, Rebekah Grace, Gabrielle Drake, and Scott Avery. 2024. What are Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care telling us? A review of the child voice literature to understanding perspectives and experiences of the statutory care system. Children and Society 38: 2107–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Bronwyn. 2016. The Politics of Identity: Who Counts as Aboriginal Today? Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, Bronwyn, and Ryan Frazer. 2021. Indigenous Digital Life: The Practice and Politics of Being Indigenous on Social Media. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, Tatiana, Danielle Captain-Webb, and James Beaufils. 2025. Bail law reform and the erosion of First Nations children’s rights in NSW. First Nations Law Bulletin 1: 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cripps, Kyllie. 2023. Indigenous Domestic and Family Violence, Mental Health and Suicide; (Catalogue No. IMH 19). Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Available online: https://www.indigenousmhspc.gov.au/publications/dfv (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Cripps, Kyllie, and Daphne Habibis. 2019. Improving Housing and Service Responses to Domestic and Family Violence for Indigenous Individuals and Families. AHURI Final Report. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Megan. 2019. Family is Culture: Independent Review into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children and Young People in Out-of-Home Care in New South Wales. Available online: https://www.familyisculture.nsw.gov.au/ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Davis, Megan. 2021. Still They Take the Children Away While Our Report Gathers Dust. The Sydney Morning Herald. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/still-theytake-the-children-away-while-20211107-p596oy.html (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Dudgeon, Pat, Abigail Bray, Gracelyn Smallwood, Roz Walker, and Tania Dalton. 2020. Wellbeing and Healing Through Connection and Culture. Lifeline. Available online: https://www.lifeline.org.au/about/our-research/connection-and-culture-report/ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Fallon, Barbara, Martin Chabot, John Fluke, Cindy Blackstock, Bruce MacLaurin, and Lil Tommyr. 2013. Placement decisions and disparities among Aboriginal children: Further analysis of the Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect part A: Comparisons of the 1998 and 2003 surveys. Child Abuse & Neglect 37: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, Darren, Ken Carter, Kate Anderson, Alana Gall, Kirsten Howard, Jemma Venables, Karen Healy, Lea Bill, Angeline Letendre, Michelle Dickson, and et al. 2024. Understanding the Wellbeing Needs of First Nations Children in Out-of-Home Care in Australia: A Comprehensive Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21: 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gerard, Alison, Andrew McGrath, Emma Colvin, and Kath McFarlane. 2018. “I’m not getting out of bed!” Criminalising young people in residential care. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 51: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Niel, Nigel Parton, and Marit Skivenes. 2012. Child Protection Systems International Trends and Orientations. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldingay, Sophie, Joleen Ryan, and Angela Daddow. 2024. Decolonising and Reframing Critical Social Work: Research and Stories from Practice, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, Kalinda, Clare Coleman, Vanessa Lee, and Richard Madden. 2016. How colonisation determines social justice and Indigenous health—A review of the literature. Journal of Population Research 33: 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, Kalinda E., Jessica Blain, Claire M. Vajdic, and Louisa Jorm. 2021. Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Data Governance in Health Research: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 10318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson Pulver, Lisa, Megan Williams, and Sally Fitzpatrick. 2019. Social Determinants of Australia’s First Peoples’ Health: A Multi-Level Empowerment Perspective. In Social Determinants of Health. Edited by Pranee Liamputtong. Docklands: Oxford University Press, pp. 175–214. [Google Scholar]

- Janke, Terri. 2019. True Track: Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property Principles for putting Self-Determination into practice. Ph.D. thesis, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Janke, Terri, and David Dawson. 2020. Protecting Indigenous cultural authority in Australian law. Griffith Law Review 29: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Krakouer, Jacynta. 2018. “We Live and Breathe Through Culture”: Conceptualising Cultural Connection for Indigenous Australian Children in Out-of-home Care. Australian Social Work 71: 265–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakouer, Jacynta, Wei Wu Tan, and Arno Parolini. 2021. Who is analysing what? The opportunities, risks and implications of using predictive risk modelling with Indigenous Australians in child protection: A scoping review. Australian Journal of Social Issues 56: 173–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukutai, Tahu, and Taylor John, eds. 2016. Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Toward an Agenda. Canberra: ANU Press, vol. 38, Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1q1crgf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Maiam nayri Wingara. Indigenous Sovereignty Data Collective and Australian Indigenous Governance Institute. 2022. Indigenous Data Sovereignty–Data for Governance: Governance of Data: Briefing Paper. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b3043afb40b9d20411f3512/t/5b70e7742b6a28f3a0e14683/1534125946810/Indigenous+Data+Sovereignty+Summit+June+2018+Briefing+Paper.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Martin, Karen. 2017. Aboriginal child-rearing practices. The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children Discussion Paper. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane, Katherine. 2017. Care-criminalisation: The nexus between the care and criminal justice systems. Continuum 32: 151–64. [Google Scholar]

- Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. 2013. Towards an Australian Indigenous Women’s Standpoint Theory: A Methodological Tool. Australian Feminist Studies 28: 331–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. 2015. The White Possessive: Property, Power, and Indigenous Sovereignty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt155jmpf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Palmater, Pam. 2018. Confronting Racism and Over-Incarceration of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Journal of Community Corrections 27: 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Parisi, Anna, Anjalee Sharma, Matthew O. Howard, and Amy Blank Wilson. 2019. The relationship between substance misuse and complicated grief: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 103: 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price-Robertson, Rhys, Leah Bromfield, Alister Lamont, and Child Family Community Australia. 2014. International Approaches to Child Protection: What Can Australia Learn? Melbourne: Child Family Community Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Raman, Shanti, Reynolds Sandra, and Khan Rabia. 2011. Addressing the well-being of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care: Are we there yet? Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 47: 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, Pamela, and McMillan Faye. 2022. Reconciliation and Indigenous self-determination in health research: A call to action. PLoS Global Public Health 2: e0000999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentencing Council of New South Wales. 2022. Annual Report 2022—Sentencing Trends and Practices; Sydney: NSW Sentencing Council.

- SNAICC. 2024. Family Matters Report 2024. Available online: https://www.snaicc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/241119-Family-Matters-Report-2024.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- SNAICC. 2025. Family Matters Report 2025. Available online: https://www.snaicc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Family-Matters-Report-2025.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Swan, Debra, and Jen Swan. 2023. Demanding Change of Colonial Child Protection Systems Through Good Trouble: A Community-Based Commentary of Resistance and Advocacy. First Peoples Child & Family Review 18: 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudgett, Skye, Kalinda Griffiths, Farnbach Sara, and Shakeshaft Anthony. 2022. A framework for operationalising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander data sovereignty in Australia: Results of a systematic literature review of published studies. EClinicalMedicine 45: 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tuhiwai Smith, Linda. 2021. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 3rd ed. London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, Maggie, and Stephanie Carroll. 2020. Indigenous Data Sovereignty, Governance and the Link to Indigenous Policy. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, Maggie, Martin Karen, and Bodkin-Andrews Gawaian, eds. 2017. Indigenous Children Growing up Strong: A Longitudinal Study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Families. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Ian, James Beaufils, and Tatiana Corrales. 2024. Decolonisation, biopolitics and neoliberalism: An Australian study into the problems of legal decision-making. Children and Youth Services Review 168: 108035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watego, Chelsea. 2021. Another Day in the Colony. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Kris. 2023. Indigenous data sovereignty in practice. First Nations Law Bulletin 1: 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Richard. 1997. Bringing Them Home: National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. Sydney: Commonwealth of Australia, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Shawn. 2008. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wundersitz, Joy. 2010. Indigenous Violence and Alcohol-Use. AIC Reports. Washington, DC: AIC. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.