Americans and Return Migrants in the 1881 Scottish Census

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Return Migration Issues

- The difficulty in discovering rates of return. This is largely due to the lack of documentation and, where there is documentation, the inclusion of return migrants with visitors, tourists and others;

- Defining return migration. Different definitions revolve around length of stay and the motives behind the migration;

- Why do people return? There are many reasons people have for returning to their country of origin. Those discussed in the literature include political and/or economic climate in home and/or host country, the saving of enough money for successful return, family ties, retirement, homesickness;

- What type of impact do returnees have on their country of origin? Most researchers find both positive and negative impacts in the home country. Some researchers claim that impact seems to be diluted due to low numbers of return migrants in any one area whereas others find important local impacts through the enrichment of the economy.

- Gaps in research. Researchers all agree that there are many gaps in the topic area of return migration and much more work needs to be done.

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Initial Research Aims and Results

- (1)

- Gather basic demographic data on the 2167 Americans in the 1881 Scottish census to include:

- Age;

- Sex;

- Occupation;

- Birthplace in USA.

- (2)

- To consider why these people were bucking the overwhelming trend of migration to the United States and moving in the opposite direction—to Scotland.

4.1.1. Sex

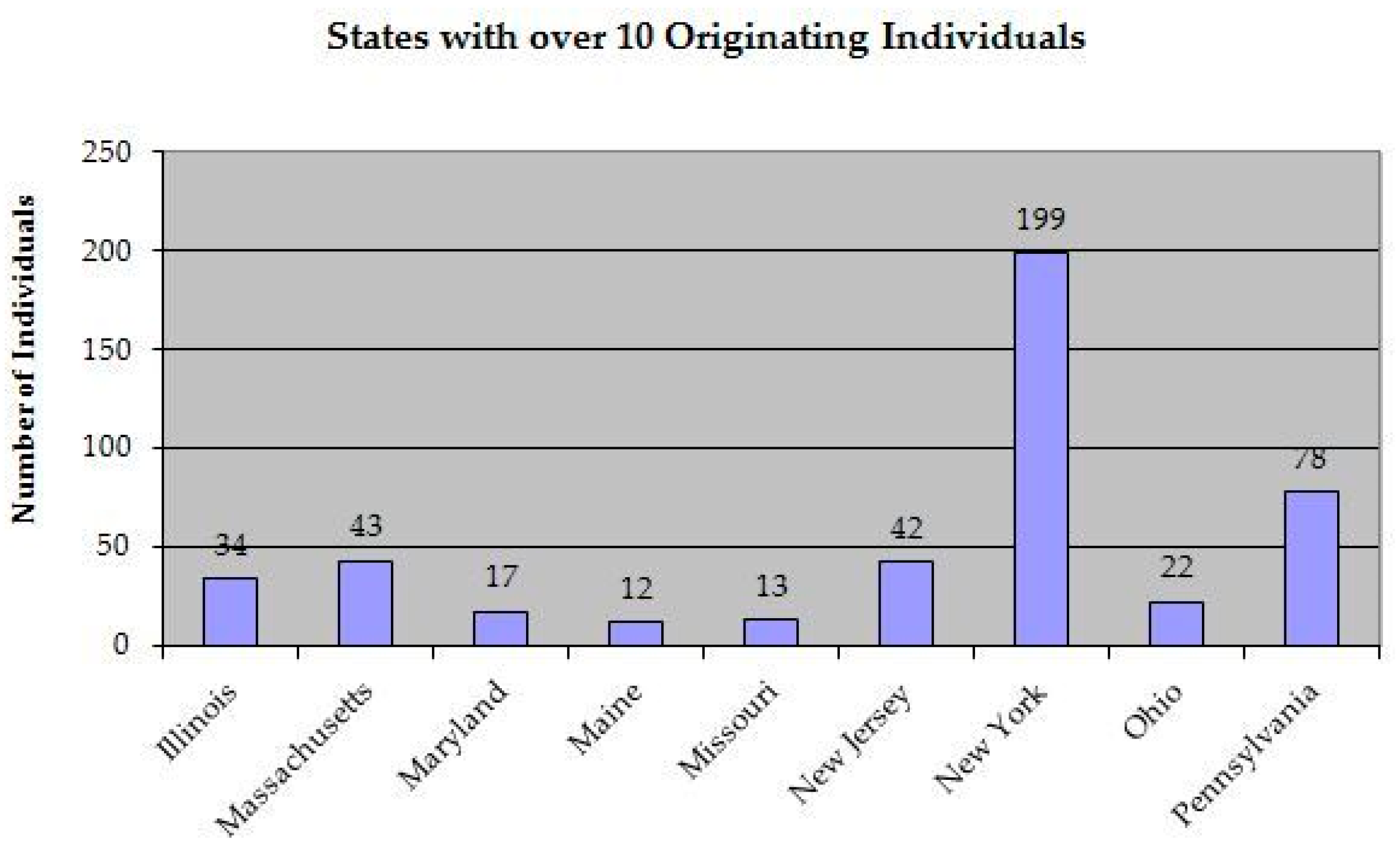

4.1.2. U.S. State of Origin

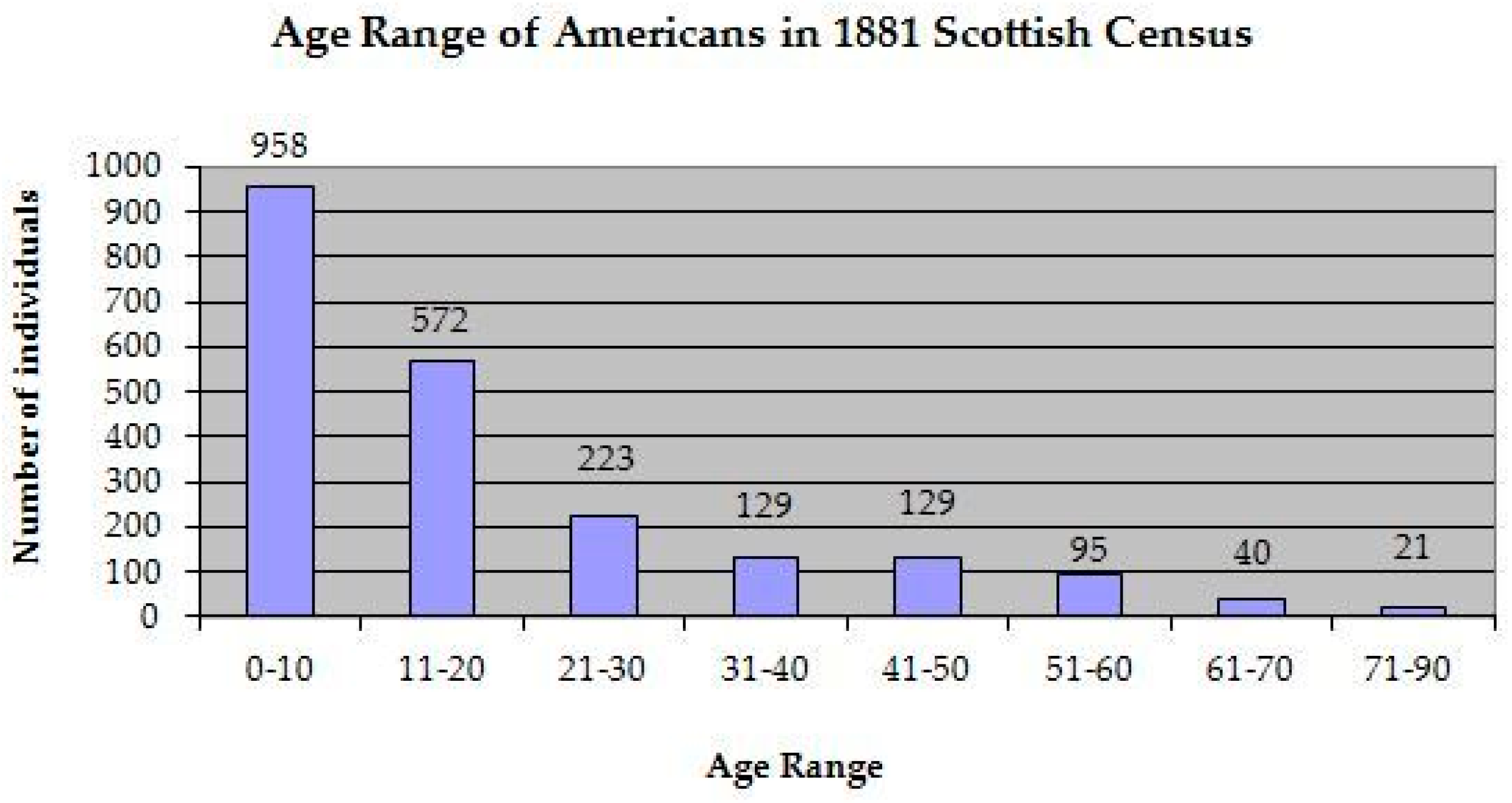

4.1.3. Age Range of Americans in 1881 Scottish Census

4.1.4. Occupations of Adult Americans in the 1881 Scottish Census

4.1.5. Discussion of Initial Research Results

4.2. Expanded Research Aims and Results

- (1)

- Gather basic demographic data on the parents in the 1881 Scottish census to include:

- Nationality;

- Scottish county of residence by number of American children;

- Occupation of parent;

- Number of years in Scotland since return.

- (2)

- To consider issues around return migration found in the literature.

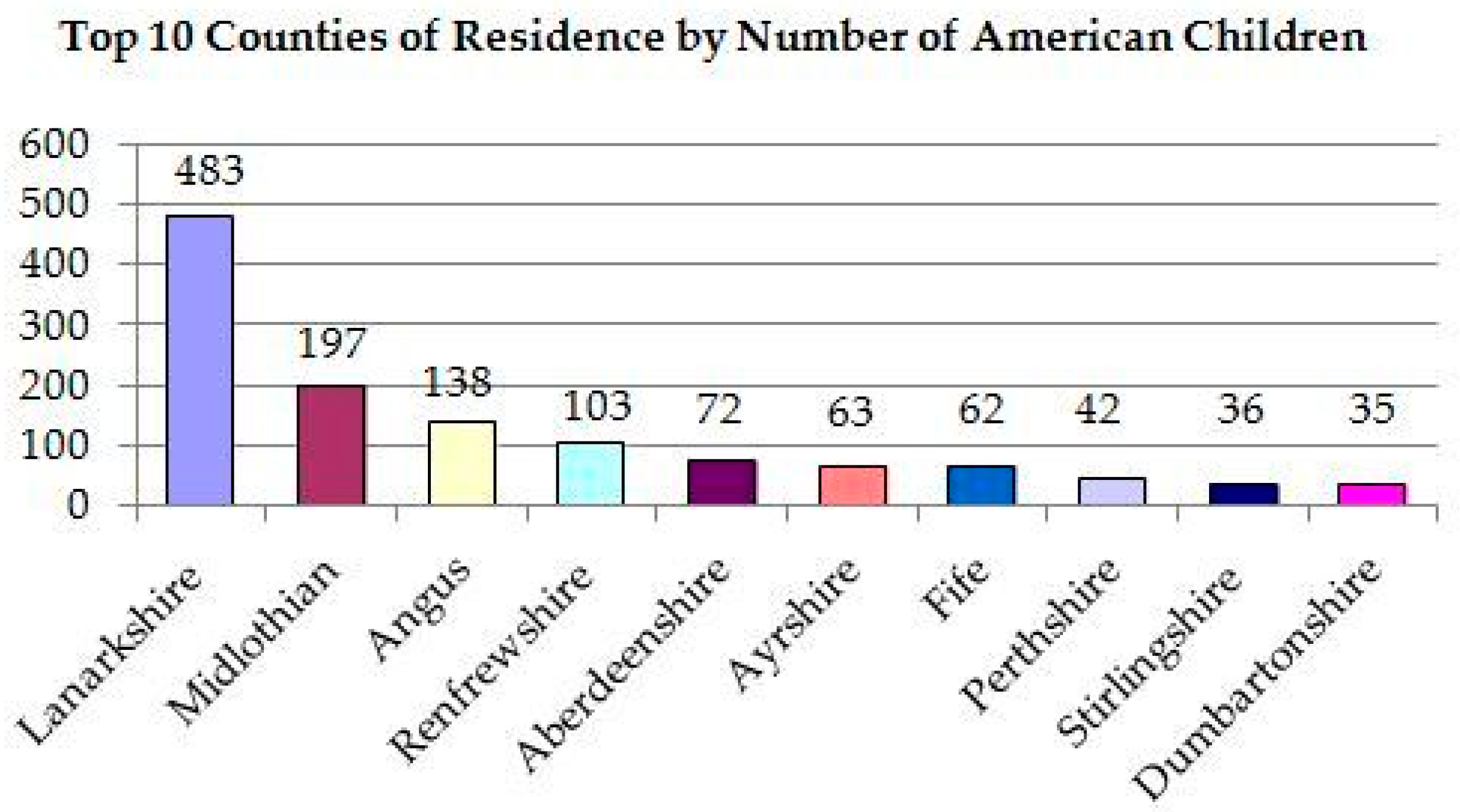

4.2.1. Top 10 Scottish Counties of Residence

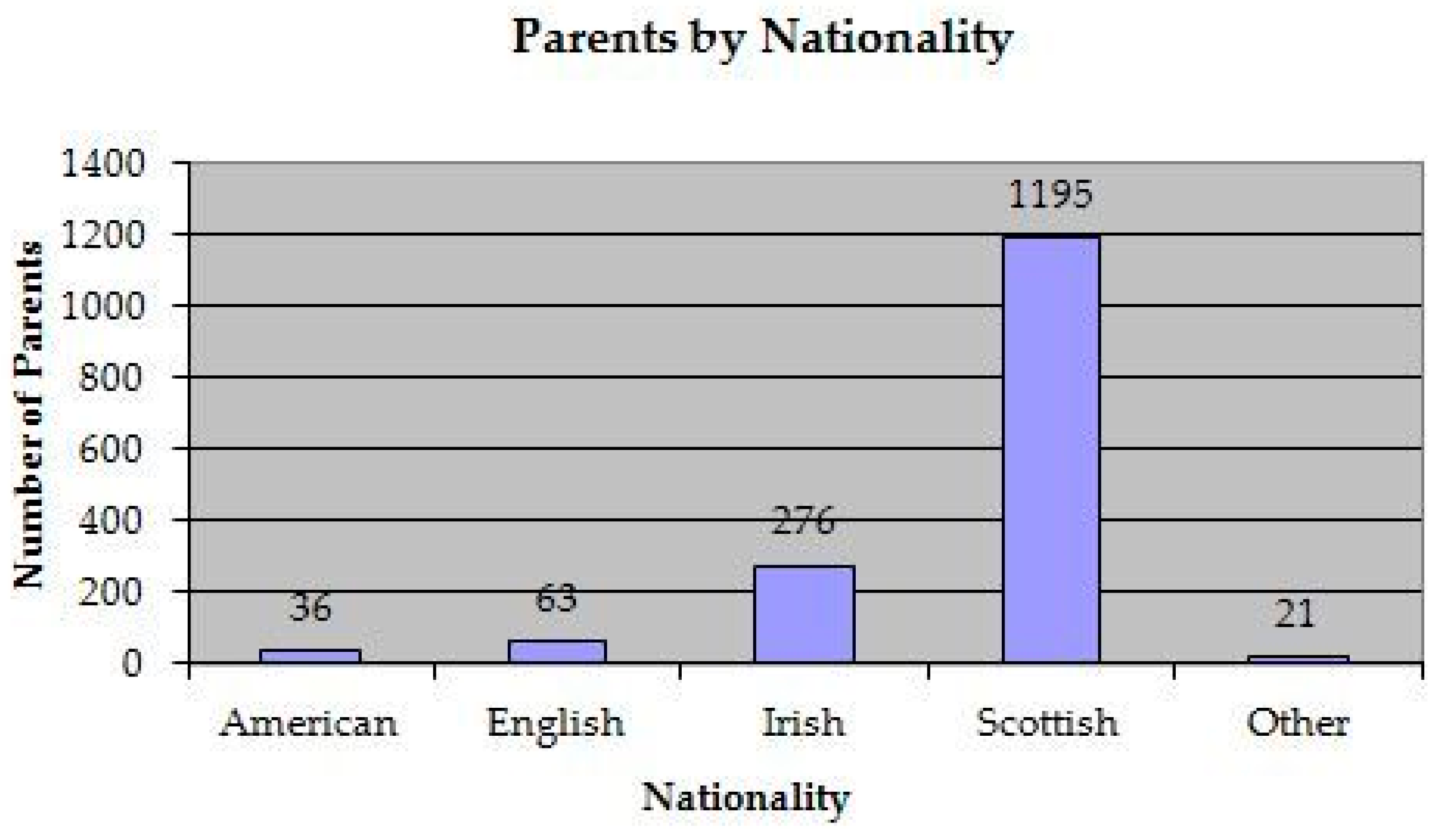

4.2.2. Parents by Nationality

4.2.3. Number of American Children in Two-Parent Households Grouped by Parental Nationality

4.2.4. Probable Year of Migration to Scotland

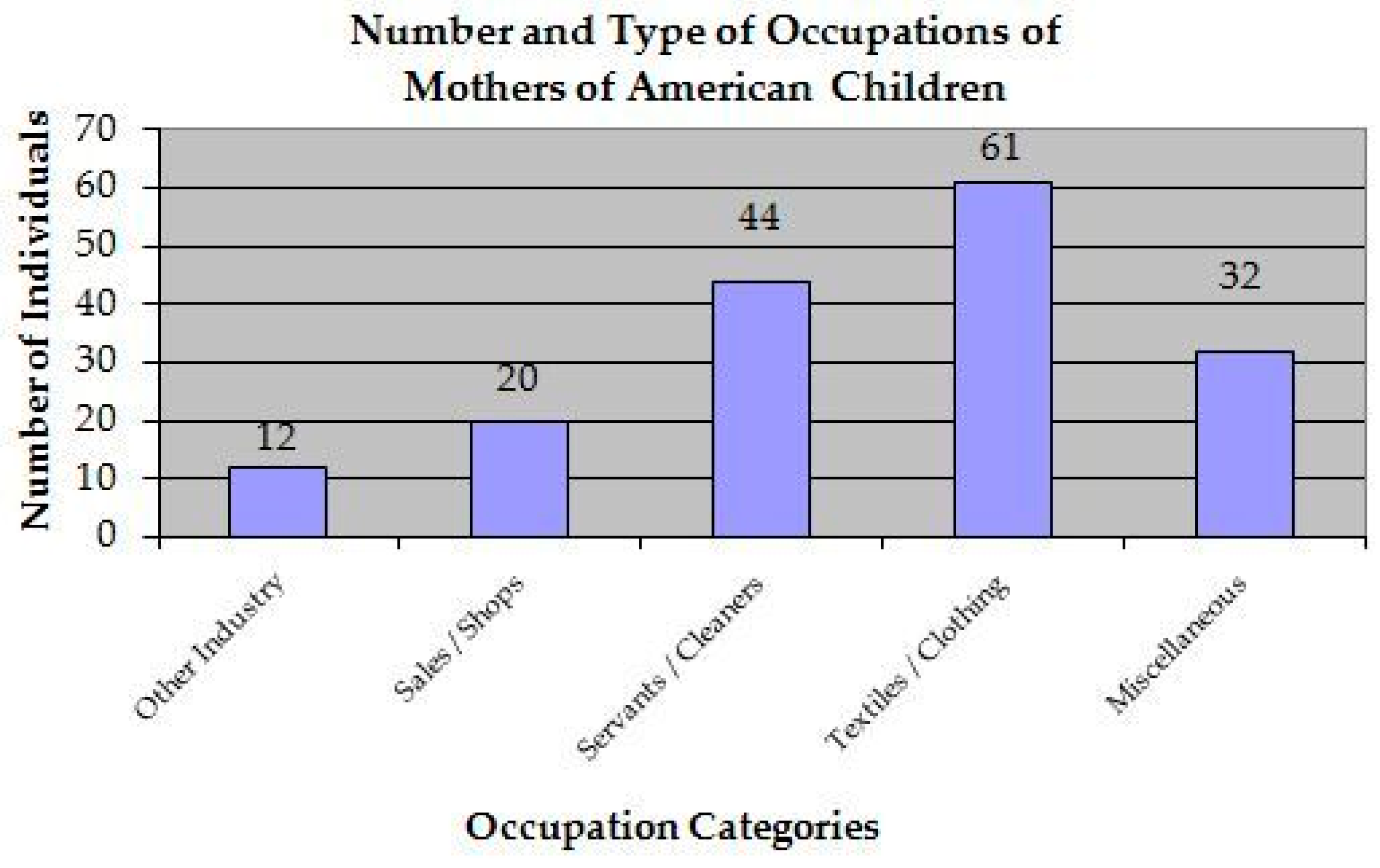

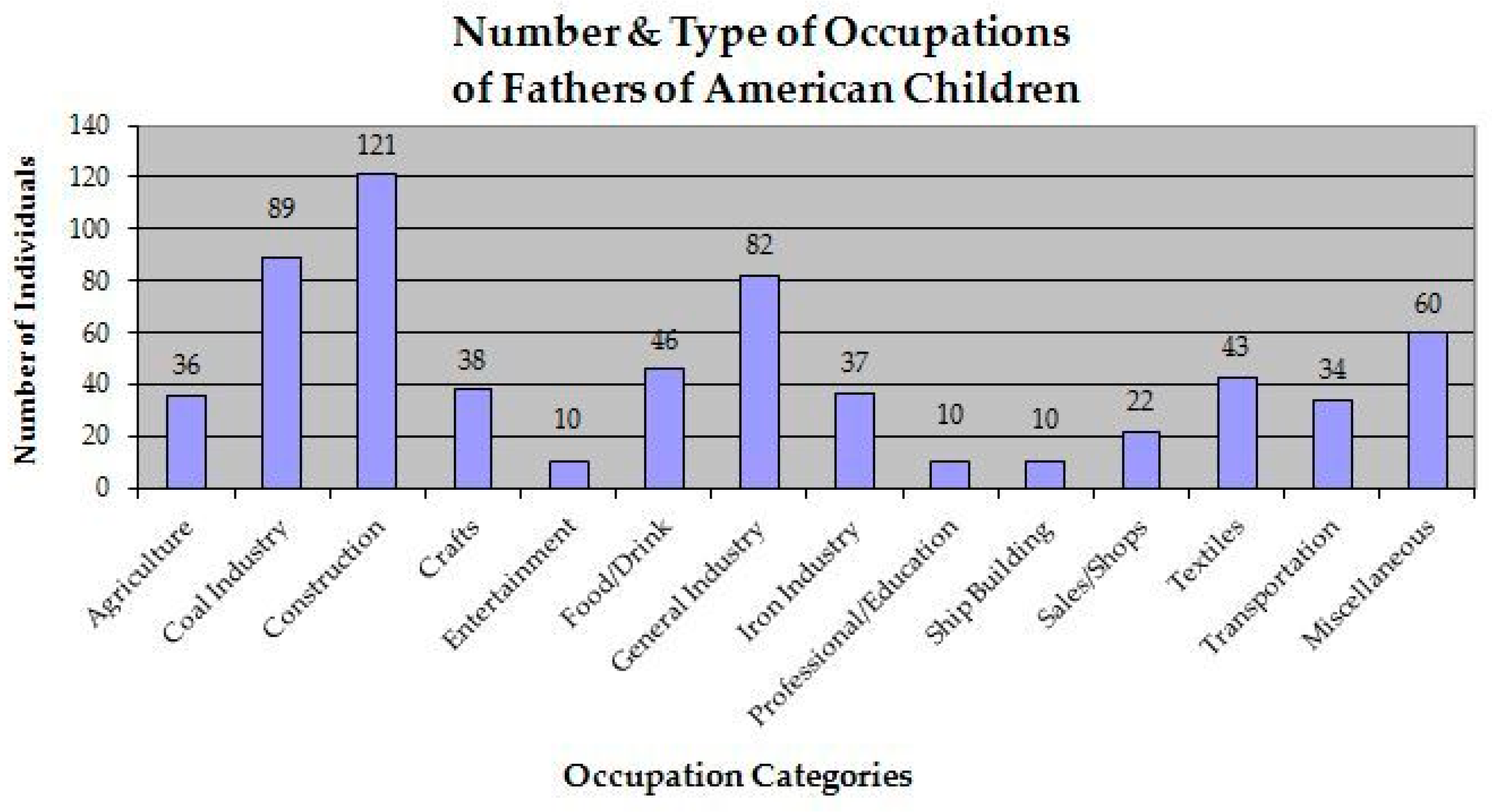

4.2.5. Number and Type of Occupations of Parents of American Children

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Case Studies on Individual Families

- Catherine M.H. Hay, born about 1865, America. There is a possible death registration record for her in Queensland, Australia on 21 January 1953; the parent names match the census information quite closely;1

- George H Hay, born about 1862, America. George appears in the 1891 Scottish census and the 1901 English census (where his birthplace is given as Scotland). It appears he immigrated to Australia as he can be found on a passenger list with his wife and children arriving in Brisbane on 5 February 19022, in the Australian electoral rolls from 1913 to 19543, finally dying on 27 October 1956 in Queensland;4.

- Grace Caroline Halkett Hay, born about 1860, America. She was married in 1885 in Alyth, Perth to Caleb Joseph Pamely, a Welsh 36 year old mining engineer.5 She appears on the 1901 Welsh census living in Chepstow, Wales with Caleb and their three Welsh children. In this census, she is shown as having been born in Minnesota, U.S.A.6 The family also appear in the 1911 living in Bristol7 and Grace’s probate entry shows her death on 26 October 1940 in Bristol.8

- James Fisher, born about 1875, is a British subject born in America, a scholar. See below for further details.

- Rose Mechan, born about 1874, in New York, America. No further information could be found for Rose.

- Margret Morrisey, born about 1869, in Vermont, USA, is a scholar. No further information could be found for Margret.

- George Waterston, born about 1874 in Ralls County, Missouri, America. He married Eva Dooley Wills on the 7 July 1915 in Mexico, Monroe County, Missouri.18 He registered in the WWI draft on 12 September 1918 at the age of 45 residing in Perry, Missouri.19 George died in Olmstead County, Minnesota on the 21 April 1923;20

- Oly May Waterston, born about 1876 in Ralls County, Missouri, America. She married Thomas A. ROSELLE on the 9 February 1904 at the ‘bride’s home’ which was in Perry, Monroe County, Missouri.21 She appears in American censuses residing in Missouri through 1940 and died in December of 1954 in Palmyra, Missouri.22

References

- Alexander, J. Trent, Katherine M. Donato, Donna R. Gabaccia, and Johanna Leinonen. 2008. Gender ratios in global migrations, 1850–2000. Paper presented at the Population Association of America 2008 Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, April 18; Available online: http://paa2008.princeton.edu/abstracts/80505 (accessed on 26 June 2017).

- Anderson, Michael, and Donald Morse. 1990. The people. In People and Society in Scotland, 1830–1914. Edited by Fraser W. Hamish and Robert John Morris. Edinburgh: John Donaldson Publishers, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, Dudley. 1985. Migration in a Mature Economy: Emigration and Internal Migration in England and Wales, 1861–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, Dudley. 1991. Emigration from Europe: 1815–1930. London: Macmillan Education Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Jeanette M. 1999. The Mobile Scot: A Study of Emigration and Migration, 1861–1911. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Census. 1881. Scotland. [Transcription]. Available online: https://www.ancestry.co.uk/ (accessed on 1 January 2008–31 July 2009).

- Census Office Scotland. 1882a. Census of Scotland 1881, vol. I. Available online: http://www.histpop.org (accessed on 27 April 2017).

- Census Office Scotland. 1882b. Census of Scotland 1881, vol. II. Available online: http://www.histpop.org (accessed on 27 April 2017).

- Devine, Tom M. 2006. The Scottish Nation, 1700–2007, 2nd ed. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Encyclopedia Britannica. 2014. Bret Harte: American Writer. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bret-Harte (accessed on 27 April 2017).

- Gottlieb, Amy Zahl. 1978. Immigration of British coal miners in the Civil War decade. International Review of Social History 23: 357–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, A. 2005. Returning to Belhavie, 1593–1875: The impact of return migration on an Aberdeenshire parish. In Emigrant Homecomings: The Return Movement of Emigrants, 1600–2000. Edited by Marjory Harper. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 216–32. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, Marjory. 1988. Emigration from North-East Scotland: Willing Exiles. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- King, Russell, ed. 1986. Return migration and regional economic development: An overview. In Return Migration and Regional Economic Problems. Kent: Croom Helm Ltd., pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- King, Russell, and Anastasia Christou. 2010. Cultural geographies of counter-diasporic migration: Perspectives from the study of second-generation ‘returnees’ to Greece. Population, Space and Place 16: 103–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Russell, and Anastasia Christou. 2011. Of counter-diaspora and reverse transnationalism: Return mobilities to and from the ancestral homeland. Mobilities 6: 451–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFeber, Walter. 1963. The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860–1898. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, Tahitia. 2016. Identifying Americans resident in Scotland during the 19th century: The evolution of a research project. Paper presented at the XXXII International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences, Glasgow, Scotland, August. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Angela. 2007. Personal Narratives of Irish and Scottish Migration, 1921–1965: ‘For Spirit and Adventure’. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peart, Ann. 2008. Women and Ministry within the British Unitarian Movement. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Tindall, George Brown, and David E. Shi. 1997. America: A Narrative History, brief 4th ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Consulate General in Scotland. 2007. History of the U.S. Consulate Edinburgh. Available online: https://uk.usembassy.gov/embassy-consulates/edinburgh/history/ (accessed on 27 April 2017).

- U.S. Secretary of Labor. 1923. Eleventh Annual Report; Washington: Government Printing Office.

- Wyman, Mark. 1993. Round-Trip to America: The Immigrants Return to Europe, 1880–1930. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Varricchio, Mario, ed. 2012. Back to Caledonia: Scottish Homecomings from the Seventeenth Century to the Present. Edinburgh: John Donald, Birlinn Ltd. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Death Index. (CR) Australia. Queensland. 21 January 1953. HAY, Catherine Margery. Reg. No. B041909, p. 1013. [Transcription] Collection: Australia, Death Index, 1787–1985. Available online: https://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 29 April 2017). |

| 2 | Passenger List for S.S. Duke of Argyll departing London 5 December 1901, arriving Brisbane, Australia, 5 February 1902. HAY family. p. 355. Collection: Assisted Immigration 1848–1912. Available online: https://www.qld.gov.au/recreation/arts/heritage/archives/immigration/ (accessed on 29 April 2017). |

| 3 | Australian Electoral Commission. Queensland Electoral Rolls. 1913–1954. HAY, George Halkett. Collection: Australia, Electoral Rolls, 1903–1980. Available online: https://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 29 April 2017). |

| 4 | Death Index (CR) Australia. Queensland. 27 October 1956. HAY, George Haleburton Halkett. Reg. No. B016779, p. 1103. [Transcription] Collection: Australia, Death Index, 1787–1985. Available online: https://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 29 April 2017). |

| 5 | Marriages (CR) Scotland. Alyth, Perthshire. 14 October 1885. PAMELY, Caleb Joseph and HAY, Grace Caroline Halkett. 328/A0 15. Available online: https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk (accessed on 29 April 2017). |

| 6 | Census. 1891. Wales. Chepstow, Monmouthshire. PAMELY Family. PN: RG 13/4917. FL 61. ED 20. p. 33. Available online: https://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 29 April 2017). |

| 7 | Census. 1911. England. Bristol, Gloucestershire. PAMELY family. RD 319. ED 9. SN 429. Piece: 15067. Available online: https://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 29 April 2017). |

| 8 | Testamentary Records. England. 20 January 1941. (Death date: 26 October 1940). PAMELY, Grace Caroline. Principal Probate Registry. Calendar of the Grants of Probate. p. 177. Collection: England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858–1966, 1973–1995. Available online: https://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 29 April 2017). |

| 9 | Deaths (CR) Scotland. Alyth, Perthshire. 9 May 1883. HAY, Charles Halkett. 328/A 36. Available online: https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk (accessed on 29 April 2017). |

| 10 | Census. 1891. Scotland. Dalziel, Motherwell, Lanarkshire. FISHER Family. ED 14. SN 211. [Transcription] Available online: https://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 29 April 2017). |

| 11 | Census. 1901. Scotland. Old Monkland, Lanarkshire. FISHER Family. ED 1. SN 100. [Transcription] Available online: https://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 29 April 2017). |

| 12 | Passenger list for S.S. Columbia departing Glasgow December 1906, arriving New York City, USA, 24 December 1906. MECHAN, James. p. 22. Available online: https://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 29 April 2017). |

| 13 | Passenger list for S.S. Furnessia arriving New York City, USA. WATERSTON, Jno E. 30 November 1889. National Archives and Records Administration (United States). Available online: http://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 17 November 2016). |

| 14 | Marriages (CR) USA. Perry, Monroe County, Missouri. 8 January 1899. WATERSTON, Alfred and STUART, Allie M. p. 159. Available online: http://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 27 June 2017). |

| 15 | Deaths (CR) USA. Salt River, Ralls County, Missouri. 18 April 1919. WATERSTON, Alfred. RD: 727, State file No. 15656. Available online: http://www.sos.mo.gov/images/archives/deathcerts/1929/1929_00016076.PDF (accessed on 27 June 2017). |

| 16 | Marriages (CR) USA. Ralls County, Missouri. 22 September 1897. WATERSTON, Elizabeth F. and MARTIN, William A. Record number: 4400. Available online: http://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 27 June 2017). |

| 17 | Monumental inscriptions. USA. Mission Garden of Memories Cemetery, Clovis, Curry County, New Mexico. 1958. MARTIN, Elizabeth W. Transcribed by Michael Trower. Find A Grave Memorial: 65163700. Available online: http://www.findagrave.com (accessed on 27 June 2017). |

| 18 | Marriages (CR) USA. Mexico, Monroe County, Missouri. 7 July 1915. WATERSTON, George Fenton and WILLS, Eva Dooley. p. 375. Available online: http://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 27 June 2017). |

| 19 | Selective Service System (USA). World War I Draft Registration Card. 12 September 1918. WATERSTON, George Fenton. Residence: Monroe County, Missouri. Available online: https://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 27 June 2017). |

| 20 | Deaths (CR) USA. Olmstead County, Minnesota. WATERSTON, George Fenton. State file number: 010006. Record number: 376595. Available online: http://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 27 June 2017). |

| 21 | Marriages. (CR) USA. Perry, Monroe County, Missouri. 9 February 1904. WATERSTON, Ollie May and ROSELLE, Thomas A. p. 42. Available online: http://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 26 February 2014). |

| 22 | Deaths (CR) USA. Palmyra, Marion County, Missouri. 23 December 1954. ROSELLE, Oly Mae. RD: 209, State file No: 41731. Available online: http://www.sos.mo.gov/images/archives/deathcerts/1954/1954_00041731.PDF (accessed on 26 June 2017). |

| 23 | Census. 1900. USA. South Fork Township, Monroe County, Missouri. ED 121. p. 5A. Available online: http://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 26 February 2014). |

| 24 | Census. 1910. USA. South Fork Township, Monroe County, Missouri. ED 127. p. 7B. Available online: http://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 26 February 2014). |

| 25 | Census. 1920. USA. Perry City, Salt River Township, Monroe County, Missouri. ED 157. p. 4B. Available online: http://www.ancestry.co.uk (accessed on 26 February 2014). |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCabe, T.L. Americans and Return Migrants in the 1881 Scottish Census. Genealogy 2017, 1, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy1030016

McCabe TL. Americans and Return Migrants in the 1881 Scottish Census. Genealogy. 2017; 1(3):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy1030016

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCabe, Tahitia L. 2017. "Americans and Return Migrants in the 1881 Scottish Census" Genealogy 1, no. 3: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy1030016

APA StyleMcCabe, T. L. (2017). Americans and Return Migrants in the 1881 Scottish Census. Genealogy, 1(3), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy1030016