Occupational and Nonoccupational Chainsaw Injuries in the United States: 2018–2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

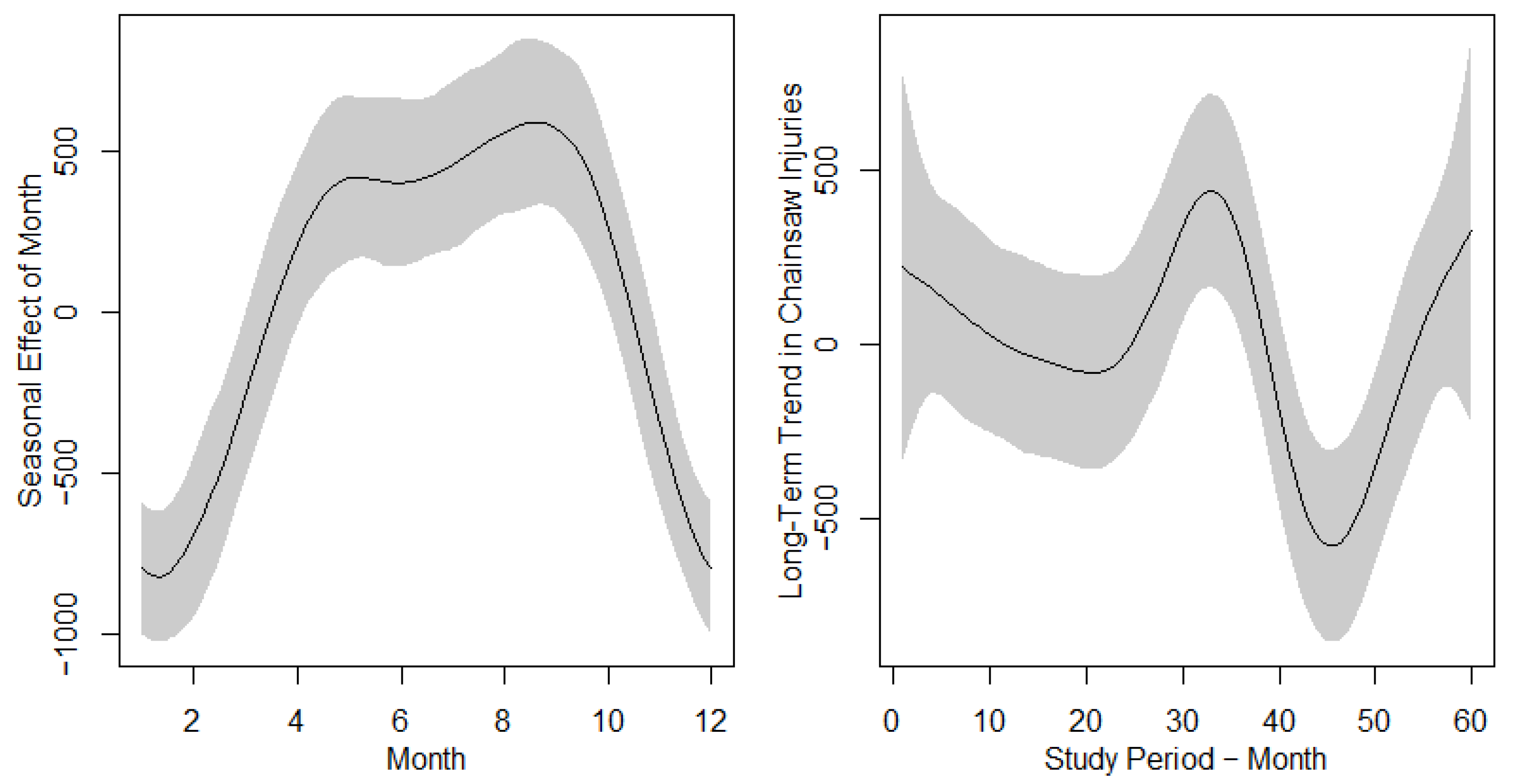

3.1. Nonoccupational Chainsaw Injuries

3.2. Occupational Chainsaw Injuries

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Recommendations

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Preventing Injuries and Death of Loggers. 1995. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/95-101/default.html (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Robb, W.; Cocking, J. Review of European chainsaw fatalities, accidents and trends. Int. J. Urban For. 2014, 36, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEntire, D. Managing debris successfully after disasters: Considerations and recommendations for emergency managers. J. Emerg. Manag. 2006, 4, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Chainsaw Safety. NIOSH. 2020. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/chain_saw_safety.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Haynes, C.D.; Webb, W.; Fenno, C. Chain saw injuries: Review of 330 cases. J. Trauma 1980, 20, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, J.H.; Gorucu, S. Occupational Tree Felling Fatalities: 2010–2020. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2021, 64, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities. 2022. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/iif/fatal-injuries-tables/fatal-occupational-injuries-table-a-1-2022.htm (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Hammig, B.; Jones, C. Epidemiology of Chain Saw Related Injuries, United States: 2009 through 2013. Adv. Emerg. Med. 2015, 2015, 459697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lawson, S.; Masterson, E. Timber, Noise, and Hearing Loss: A Look into the Forestry and Logging Industry. NIOSH Science Blog. 2018. Available online: https://blogs.cdc.gov/niosh-science-blog/2018/05/24/noise-forestry/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Feyzi, M.; Jafari, A.; Ahmadi, H. Investigation and analysis the vibration of handles of chainsaw without cutting. J. Agric. Mach. 2016, 6, 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, B.M.; Graydon, P.S.; Pena, M.; Feng, H.A.; Beamer, B.R. Hazardous exposures and engineering controls in the landscaping services industry. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2025, 22, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slappendel, C.; Laird, I.; Kawachi, I.; Marchall, S.; Cryer, C. Factors affecting work-related injury among forestry workers: A review. J. Saf. Res. 1993, 24, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosencrance, J.; Lagerstrom, E.; Murgia, L. Job Factors Associated with Occupational Injuries and Deaths in the United States Forestry Industry. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2023, 58, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, B.; Brodbeck, B. Chainsaw safety: Ergonomics. Alabama A&M Extension. Available online: https://www.aces.edu/blog/topics/forestry/chainsaw-safety-ergonomics/#:~:text=Most%20chainsaw%20injuries%20are%20a,fatigue%20and%20lower%20back%20injuries (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Lopez-Toro, A.; Pardo-Ferreira, M.; Martinez-Rojas, M.; Carrillo, J.; Rubio-Romero, J. Analysis of occupational accidents during the chainsaws use in Andalucía. Saf. Sci. 2021, 143, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormoehlen, S.A.; Field, W.E.; Ehlers, S.G.; Ferraro, K.F. Indiana Farm Occasional Wood Cutter Fatalities Involving Individuals 55 Years and Older. J. Agric. Saf. Health 2020, 26, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. NEISS Highlights, Data and Query Builder. Available online: https://www.cpsc.gov/cgibin/NEISSQuery/home.aspx (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. NEISS Frequently Asked Question. Available online: https://www.cpsc.gov/Research--Statistics/NEISS-Injury-Data/Neiss-Frequently-Asked-Questions (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. NEISS Coding Manual. Available online: https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/2019_NEISS_Coding_Manual.pdf?kF045AF8hSkt_vPuRHjyIbiet.BzcT_v (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Explanation of NEISS Estimates Obtained Through the CPSC Website. Available online: https://www.cpsc.gov/Research--Statistics/NEISS-Injury-Data/Explanation-Of-NEISS-Estimates-Obtained-Through-The-CPSC-Website (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- U.S. DOL. Fatality and Catastrophe Investigation Summaries. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/pls/imis/accidentsearch.html (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- BLS. Occupational Injury and Illness Classification System (OIICS) Code Trees v2.01. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Washington, DC, USA. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/wisards/oiics/Trees/MultiTree.aspx?Year=2012 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- U.S. DOL. Severe Injury Reports. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/severeinjury (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Gomes, H.; Parasram, V.; Collins, J.; Socias-Morales, C. Time series, seasonality and trend evaluation of 7 years (2015–2021) of OSHA severe injury data. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 86, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American National Standards Institute. ANSI Z133: Safety Requirements for Arboricultural Operations. ANSI. 2020. Available online: https://www.isa-arbor.com/Portals/0/Assets/PDF/research/Z133_2nd_Public_Review_Clean.pdf?ver=2024-01-31-141704-253 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Helmkamp, J.; Bell, J.; Lundstrom, W.; Ramprasad, J.; Haque, A. Assessing safety awareness and knowledge and behavioral change among West Virginia loggers. Inj. Prev. 2004, 10, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagerstrom, E.; Magzamen, S.; Brazile, W.; Stallones, L.; Ayers, P.; Rosecrance, J. A Case Study in the Application of the Systematic Approach to Training in the Logging Industry. Safety 2019, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oregon OSHA. Guide for Landscaping Contractors. 2018. Available online: https://osha.oregon.gov/OSHAPubs/2942.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Dabrowski, A. Reducing Kickback of Portable Combustion Chain Saws and Related Injury Risks: Laboratory Tests and Deductions. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2015, 18, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papendrea, S.; Cataldo, M.; Zimbalatti, G.; Grigolato, S.; Proto, A. What Is the Current Ergonomic Condition of Chainsaws in Non-Professional Use? A Case Study to Determine Vibrations and Noises in Small-Scale Agroforestry Farms. Forests 2022, 13, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggstrom, C.; Edlund, B. Knowledge Retention and Changes in Licensed Chainsaw Workers’ risk awareness. Small-Scale For. 2023, 22, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSHA. Fact Sheet. Working Safely with Chain Saws. 2018. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/chainsaws.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- OSHA. Landscape and Horticultural Services, Hazards and Solutions. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 2020. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/landscaping/hazards (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Chainsaw Safety: 6 Minutes for Safety. Available online: https://www.nwcg.gov/6mfs/felling-safety/chainsaw-safety (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Hönigsberger, F.; Gollob, C.; Varch, T.; Waldhäusl, D.; Holzinger, A.; Stampfer, K. Use of Bluetooth low energy and ultra-wideband sensor systems to detect people in forest operations danger zones. Int. J. For. Eng. 2024, 36, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorucu, S.; Michael, J.; Chege, K. Nonfatal Agricultural Injuries Treated in Emergency Departments: 2015–2019. J. Agromed. 2022, 27, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Number (n = 2528) | Estimated Patients (95% CI) (n = 127,944) | % of National Estimate (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2018 | 520 | 26,876 (24,529–29,223) | 21.0% (19.2–22.9%) |

| 2019 | 463 | 24,715 (22,390–27,041) | 19.3% (17.6–21.2%) | |

| 2020 | 607 | 29,416 (27,027–31,805) | 23.0% (21.2–24.9%) | |

| 2021 | 474 | 21,162 (19,151–23,172) | 16.5% (15.0–18.2%) | |

| 2022 | 464 | 25,775 (23,410–28,139) | 20.1% (18.4–22.0%) | |

| Gender | Male | 2394 | 121,060 (119,738–122,382) | 94.6% (93.5–95.5%) |

| Female | 134 | 6884 (5585–8183) | 5.4% (4.5–6.5%) | |

| Age group | 0–17 | 106 | 4940 (3811–6068) | 3.9% (3.1–4.8%) |

| 18–24 | 189 | 8938 (7491–10,384) | 7.0% (5.9–8.2%) | |

| 25–34 | 387 | 19,872 (17,791–21,954) | 15.5% (14–17.2%) | |

| 35–44 | 451 | 21,942 (19,794–24,090) | 17.1% (15.5–18.9%) | |

| 45–54 | 461 | 23,616 (21,398–25,834) | 18.5% (16.8–20.3%) | |

| 55–64 | 474 | 24,643 (22,387–26,898) | 19.3% (17.6–21.1%) | |

| 65 and older | 460 | 23,994 (21,741–26,247) | 18.8% (17.1–20.6%) | |

| Variable | Number (n = 2528) | Estimated Patients (95% CI) (n = 127,944) | % of National Estimate (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injury diagnosis | Open wound/amputation | 1947 | 97,691 (95,240–100,142) | 76.4% (74.4–78.2%) |

| Fracture | 190 | 9294 (7812–10,775) | 7.3% (6.2–8.5%) | |

| Soft tissue injury | 103 | 5780 (4561–6999) | 4.5% (3.7–5.6%) | |

| Burns, foreign body, nerve | 68 | 3622 (2668–4575) | 2.8% (2.2–3.7%) | |

| Sprain or strain | 55 | 3388 (2427–4350) | 2.6% (2–3.5%) | |

| Traumatic brain injury | 50 | 2240 (1507–2972) | 1.8% (1.3–2.4%) | |

| Other a | 115 | 5930 (4714–7145) | 4.6% (3.8–5.7%) | |

| Body part injured | Upper extremities | 1085 | 54,399 (51,574–57,223) | 42.5% (40.3–44.7%) |

| Lower extremities | 1056 | 53,834 (51,004–56,663) | 42.1% (39.9–44.3%) | |

| Head and neck | 253 | 13,082 (11,341–14,824) | 10.2% (8.9–11.7%) | |

| Trunk | 122 | 6068 (4848–7288) | 4.7% (3.9–5.8%) | |

| Other b,c | 12 | 561 (181–941) | 0.4% (0.2–0.9%) | |

| Variable | Fatal | Nonfatal | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2018 | 7 (12.3%) | 65 (32.2%) | 72 (27.8%) |

| 2019 | 10 (17.5%) | 57 (28.2%) | 67 (25.9%) | |

| 2020 | 9 (15.8%) | 29 (14.4%) | 38 (14.7%) | |

| 2021 | 23 (40.4%) | 27 (13.4%) | 50 (19.3%) | |

| 2022 | 8 (14%) | 24 (11.9%) | 32 (12.4%) | |

| Gender 1 | Male | 57 (100%) | 86 (100%) | 143 (100%) |

| Female | - | - | - | |

| Age group 1 | 0–17 | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| 18–24 | 2 (3.5%) | 11 (5.4%) | 13 (5.0%) | |

| 25–34 | 13 (22.8%) | 25 (12.4%) | 38 (14.7%) | |

| 35–44 | 13 (22.8%) | 22 (10.9%) | 35 (13.5%) | |

| 45–54 | 14 (24.6%) | 10 (5%) | 24 (9.3%) | |

| 55–64 | 12 (21.1%) | 14 (6.9%) | 26 (10%) | |

| 65 and older | 2 (3.5%) | 3 (1.5%) | 5 (1.9%) |

| OIICS Category | Fatal | Nonfatal | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature | |||

| Crushing injuries | 16 (28.1%) | 4 (2%) | 20 (7.7%) |

| Unspecified traumatic injuries | 14 (24.6%) | - | 14 (5.4%) |

| Traumatic injuries to bones/muscles | 8 (14%) | 54 (26.7%) | 62 (23.9%) |

| Open wounds and amputations | 7 (12.3%) | 117 (57.9%) | 124 (47.9%) |

| Electrocutions | 7 (12.3%) | 1 (0.5%) | 8 (3.1%) |

| Intracranial injuries | 5 (8.8%) | 2 (1%) | 7 (2.7%) |

| Multiple traumatic injuries | 12 (5.9%) | 12 (4.6%) | |

| Other traumatic injuries | 12 (5.9%) | 12 (4.6%) | |

| Body part injured | |||

| Head and neck | 19 (33.3%) | 14 (6.9%) | 33 (12.7%) |

| Multiple body parts | 15 (26.3%) | 30 (14.9%) | 45 (17.4%) |

| Trunk | 5 (8.8%) | 10 (5%) | 15 (5.8%) |

| Upper extremities | 2 (3.5%) | 64 (31.7%) | 66 (25.5%) |

| Lower extremities | 1 (1.8%) | 79 (39.1%) | 80 (30.9%) |

| Nonclassifiable | 15 (26.3%) | 5 (2.5%) | 20 (7.7%) |

| Primary Source | |||

| Trees, tree limbs, logs, etc. | 38 (66.7%) | 47 (23.3%) | 85 (32.8%) |

| Chainsaws | 9 (15.8%) | 129 (63.9%) | 138 (53.3%) |

| Machine, tool, electric parts | 7 (12.3%) | 3 (1.5%) | 10 (3.9%) |

| Others | 3 (5.3%) | 23 (11.4%) | 26 (10%) |

| Event | |||

| Contact with objects and equipment | 42 (73.7%) | 165 (81.7%) | 207 (79.9%) |

| Falls | 7 (12.3%) | 31 (15.3%) | 38 (14.7%) |

| Exposure to electricity | 7 (12.3%) | 2 (1%) | 9 (3.5%) |

| Others | 1 (1.8%) | 4 (2%) | 5 (1.9%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Michael, J.H.; Gorucu, S. Occupational and Nonoccupational Chainsaw Injuries in the United States: 2018–2022. Safety 2025, 11, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030075

Michael JH, Gorucu S. Occupational and Nonoccupational Chainsaw Injuries in the United States: 2018–2022. Safety. 2025; 11(3):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030075

Chicago/Turabian StyleMichael, Judd H., and Serap Gorucu. 2025. "Occupational and Nonoccupational Chainsaw Injuries in the United States: 2018–2022" Safety 11, no. 3: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030075

APA StyleMichael, J. H., & Gorucu, S. (2025). Occupational and Nonoccupational Chainsaw Injuries in the United States: 2018–2022. Safety, 11(3), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030075