Abstract

Breast cancer is one of the most common death causes amongst women all over the world. Early detection of breast cancer plays a critical role in increasing the survival rate. Various imaging modalities, such as mammography, breast MRI, ultrasound and thermography, are used to detect breast cancer. Though there is a considerable success with mammography in biomedical imaging, detecting suspicious areas remains a challenge because, due to the manual examination and variations in shape, size, other mass morphological features, mammography accuracy changes with the density of the breast. Furthermore, going through the analysis of many mammograms per day can be a tedious task for radiologists and practitioners. One of the main objectives of biomedical imaging is to provide radiologists and practitioners with tools to help them identify all suspicious regions in a given image. Computer-aided mass detection in mammograms can serve as a second opinion tool to help radiologists avoid running into oversight errors. The scientific community has made much progress in this topic, and several approaches have been proposed along the way. Following a bottom-up narrative, this paper surveys different scientific methodologies and techniques to detect suspicious regions in mammograms spanning from methods based on low-level image features to the most recent novelties in AI-based approaches. Both theoretical and practical grounds are provided across the paper sections to highlight the pros and cons of different methodologies. The paper’s main scope is to let readers embark on a journey through a fully comprehensive description of techniques, strategies and datasets on the topic.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed diseases amongst women worldwide. It is mainly detected on screening exams or the onset of clinical symptoms. Most breast cancers start in mammary glands [1]. The incidence of breast cancer has increased all over the world, and around one million new cases are reported every year [2]. Medical examinations are the most effective method for diagnosis of this cancer. Radiologists use various imaging modalities, such as mammography, breast MRI, ultrasounds, thermography and histopathology imaging. Visual inspections of images allow clinicians to identify suspicious areas that deserve further and more in-depth analysis. The visual inspection is an operator-dependent and time-consuming task. Over the last few decades, both academics and tech companies have proposed and developed proper computer-aided methods to assist the radiologist in diagnosing. Nowadays, CADe (computer-aided detection) and CADx (computer-aided diagnosis) systems are adopted as second opinion tools by expert clinicians for the detection of suspicious regions or abnormalities [3,4]. Most CADe and CADx tools rely on image analysis, machine learning (ML) and the deep learning (DL) approach.

Malignant and benignant masses are abnormal regions or cells that can be identified in mammograms. Various visual descriptors, such as shape, margin and density, are used to categorise abnormal cells. These descriptors are adopted in BI-RADS (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System) [5], developed by the American College of Radiology. Shape and margin are adequate and discriminating descriptors for detecting masses [6]. For mammogram patch detection, low-level image features, such as interest keypoints, area, orientation, perimeter, and intensity, are frequently used [7,8]. Lot of work has been done to detect mammogram lesions using low-level image features, such as shapes, texture and local keypoint descriptors, which are discussed in this work.

AI (artificial intelligence) approaches, such as machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) gradually replaced these image processing-based techniques (e.g., methods relying on the analysis of low-level image descriptors, such as texture, local keypoints, and boundaries) because of their higher accuracy rates. Machine learning links the problem of learning from input data samples to the universal rules of inference. This approach uses analytical, statistical, and mathematical techniques that allow the machines to infer knowledge from training data without explicit programming. Some machine learning approaches [9,10,11], such as support vector machine (SVM), naïve Bayes, artificial neural network (ANN), and set classifiers [12], have become quite common for the development of computer-aided detection system for breast cancer. Machine learning techniques usually rely first on a step of image features’ extraction. Generally, the image features are described with arrays, namely descriptors, which feed training processes. The opportune choice of features then plays a fundamental role in the overall training accuracy. Historically speaking, there were some challenges motivating deep learning [13] that have represented an evolution in the traditional machine learning paradigm. Deep learning focuses on knowledge inference mechanisms from data and achieves higher levels of generalisation than in conventional machine learning. One of the most influential deep learning networks is the so-called CNN (convolutional neural network), characterised by convolutional layers. Other than traditional machine learning approaches, deep learning techniques are independent of feature extraction steps because of the high number of inner layers that somewhat perform feature extraction on the way through layer-embedded operators. DL-based algorithms are not trained to classify abnormal masses by inputting them with information about their shape, size, pattern, and other features; the algorithm itself learns what the mass looks like [14], using thousands of images during the training process. More details about techniques, architectures and models are provided in the corresponding sections of the paper.

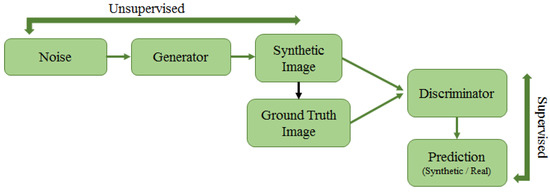

Publicly available and adequately annotated datasets are rare in the medical imaging field; hence, there is a need for methods to deal with a low number of annotated images for training models and reaching a high accuracy rate. In this regard, two main approaches, such as transfer learning and unsupervised deep learning, turn out to be quite helpful. The former faces the lack of hand-labelled data, using pre-existing deep learning architectures and fine-tuning them onto a new application domain with a reduced number of samples [15]. The latter mainly derives direct perceptions from data and uses them for data-driven decision making. These approaches are more robust, meaning that they provide the base for varieties of complex problems, such as compression, classification, denoising, reducing dimensionality, etc. Unsupervised learning is also combined with supervised learning to create a model with added generalisation. Autoencoders and generative adversarial networks are widely adopted unsupervised deep learning approaches, which are discussed in the paper.

1.1. Motivation and Study Criteria

The main objective of this paper is to discuss different techniques in the literature to detect and/or classify suspicious regions spanning from mammograms using low-level image features to machine learning techniques and deep learning approaches. In the attempt to feed the open debate on the topic as mentioned earlier, the paper aims at answering the following questions:

- Which are various techniques to extract low-level image features from mammograms?

- What machine learning approaches tackle the detection of a mistrustful region in breast images?

- What are the various supervised and unsupervised deep learning approaches used for breast image analysis to detect and/or classify a suspicious region from a mammography image?

- What are the most commonly cited and publicly available mammogram datasets?

The survey also briefly discusses various forms of breast abnormalities—morphological features that are used by radiologists to detect suspicious masses and standard projection views of mammograms. This article further shows commonly cited and publicly available datasets of breast mammograms. The same datasets are compared. Furthermore, this paper mainly presents a comprehensive study of various methods in the scientific literature on the detection of suspicious regions from mammograms. Three main groups of methods are presented in this work: low-level image feature-based approaches, machine learning approaches, and deep learning approaches. The scientific literature is full of techniques that fall within each of these categories. One of the objectives of this paper is to discuss the most used and cited ones in the mammogram analysis domain.

This paper surveys hundreds of articles from indexed and referred journals, conference proceedings and books out of major online scientific databases, including IEEE Xplore, Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed. Insightful and comprehensive surveys on mammographic image analysis are present in the scientific literature. Sadoughi et al. [16] thoroughly encompassed image processing techniques for detecting breast cancer by mostly focusing on artificial intelligence techniques. This paper aims to offer a bottom-up review, spanning both low-level image analysis and artificial intelligence techniques and providing the reader with all the materials needed to start working on the topic. For a more comparative analysis amongst studies, the paper is provided with relevant information, such as references, techniques used, scopes of work, datasets, and various performance metrics.

1.2. Paper Organization

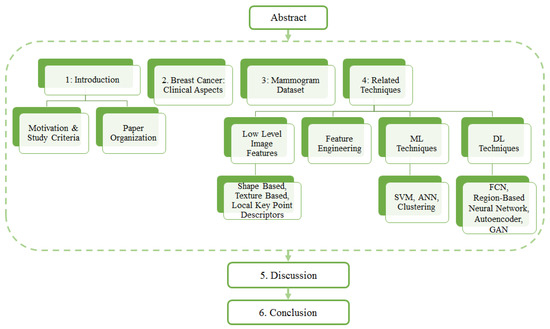

The overall structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 provides readers with a description some clinical aspects of breast cancer in terms of mammogram projection views and various forms of breast abnormalities in mammograms. Section 3 provides an up-to-date list and details of mammogram datasets along with their comparisons. A link to the URL of each dataset is also provided. Section 4 reviews the related techniques, focusing on three categories and different approaches. Finally, the paper ends with a discussion Section 5, followed by a conclusion (Section 6). The organisation of the entire paper is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Organization of paper.

2. Breast Cancer: Clinical Aspects

2.1. Breast Positioning and Projection View

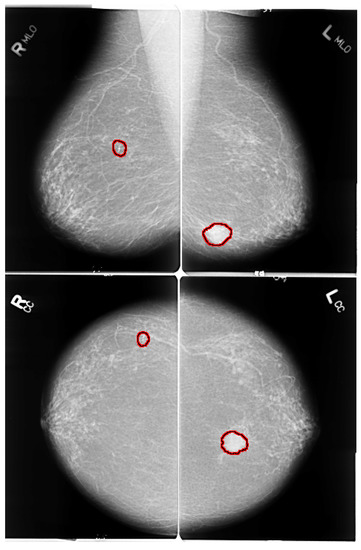

The early detection of breast cancer depends on some crucial factors, such as the quality of the imaging technique and the patient’s position while the mammogram images are being taken. Breast positioning plays such a critical role in the process; improper positioning may result in inconclusive examination and mammogram artefacts. Mediolateral oblique (MLO) and bilateral craniocaudal (CC) represent the standard mammogram views. Both views encompass routine clinical screening mammography as depicted in Figure 2. It is essential to have proper and acceptable head-turning of the patient to obtain the CC view and raising of the arms of patients to obtain the MLO view. A correct CC projection should demonstrate the pectoral muscle on the posterior breast edge, maximum breast tissue and retro mammary space. As described by Moran et al. [17], a proper MLO view should ideally show the axilla, the tail of the axilla, and the inframammary fold along with the breast tissue. For an adequate breast cancer diagnosis, it is crucial to have multi-view mammographic data. Single-view mammograms may not provide enough information for a complete screening (some lesions might be missed). Andersson et al. [18] focused on the influence of the number of projections in mammography on breast disease detection. They reviewed 491 cases of breast cancer and evaluated the diagnostic importance of standard projection views. In their study, they reported that 90% of the malignancies were detected with a single projection view. The percentage of detected malignancies increased to 94% with multi-view projections. Furthermore, the latter reasonably lowers the number of false positives. Nowadays, many publicly available datasets include multi-view images [19].

Figure 2.

MLO and CC views of mammogram. Red highlighted sections in the images present abnormalities. Left images shows right MLO and CC views of benign calcification in upper outer quadrant of right breast. Right images shows MLO and CC views of spiculated mass lesion in lower inner quadrant of left breast.

2.2. Various Forms of Breast Abnormalities

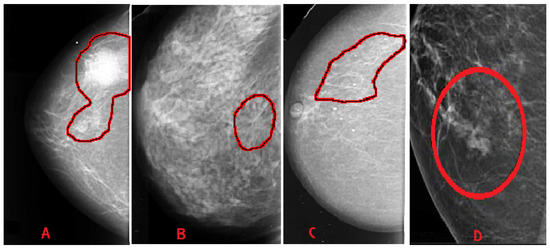

Breast abnormalities can assume different shapes and characteristics: mass (lesion), architectural distortion, calcification and asymmetry, as shown in Figure 3. These images are taken from publicly available mammogram datasets. This section briefly overviews these abnormalities and associated features.

Figure 3.

Categories of breast abnormalities. (A) Mass—well-defined irregular lesion, suspicious spiculated mass. (B) Architectural distortion. (C) Calcification—discrete microcalcification. (D) Asymmetry.

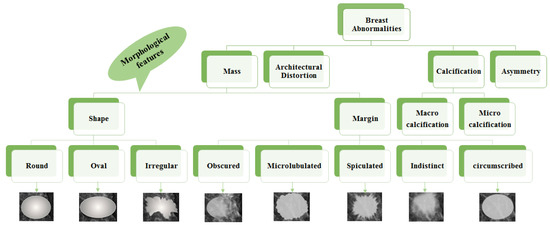

- Mass: A mass is a 3D lesion that can be seen in various projections. Morphological features, such as shape, margin and density, are used for mass characterisation. The shape can be round, oval or irregular. The margin can be not well defined, microlobulated, speculated, indistinct or circumscribed. Figure 4 shows the graphical representation of these morphological features (shape and margin) of a mass along with their subcategories. When superimposed breast tissues hide margins, that is called obscured or partially obscured. Microlobulated infers a suspicious finding. Spiculated margin with radiating lines is also a suspicious finding. Indistinct, also termed as ill-defined, is a suspicious finding too. Circumscribed is a well-defined mass that is a benign finding. Density can be high, low or fat-containing. The density of a mass is related to the expected attenuation of an equal volume of a fibroglandular tissue [6,20]. High density is associated with malignancy.

Figure 4. Taxonomy of breast abnormalities and morphological features in mammograms.

Figure 4. Taxonomy of breast abnormalities and morphological features in mammograms. - Architectural distortion: This abnormality is found when normal architecture is distorted without certain mass visibility. Architectural distortion may include straight thin lines, speculated radiating lines, or focal retraction [6,20]. This abnormality can be seen as an additional feature. If there is a mass with distortion, it is likely to be malignant.

- Calcification: Calcifications are tiny spots of calcium that develop in the breast tissues. Arrangement of calcifications can be diffuse, regional, cluster, linear or segmental [6,20]. There are two types; macrocalcification and microcalcification. Macrocalcifications are large dots of white colour and often spread randomly within the breast area. Microcalcifications are small deposits of calcium, usually non-cancerous, but if visualised as particular patterns and clustered, they may reveal an early sign of malignancy.

- Asymmetries: These are the findings that show unilateral deposits of fibroglandular tissues, which cannot confirm the definition of mass. That can be seen in only one projection and is mainly caused by the superimposition of breast tissues that are normal [6,20].

Morphological features play an essential role in diagnosing breast diseases. Several studies evaluated the effectiveness of these features to diagnose the disease and to suggest the malignancy. Gemignani [21] presented a study on breast diseases. Mammographic lesions and microcalcifications are studied in the article. According to this study, masses with spiculated boundaries and irregular shapes have the highest chances of being carcinoma. Carcinoma is a common type of breast cancer. Rasha et al. [22] used morphological descriptors of BI-RADS for the characterisation of breast lesions. The study was carried out on a total of 261 breast lesions that were identified on contrast-enhanced spectral mammography in 239 patients. The authors concluded that morphological descriptors can be applied to characterise lesions. Most suggestive morphological descriptors are irregular-shaped mass lesions with spiculated and irregular margins. Wedegartner et al. [23] presented a study to check the expediency of morphological features to distinguish between malignant and benign masses. The result of the study shows that the irregular shape of the lesion is highly indicative of malignancy. The overall taxonomy of breast abnormalities and morphological features in mammograms are presented in Figure 4.

There is a well-defined tool for risk assessment and quality assurance, developed by the American College of Radiology, called BI-RADS (Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System) [5]. Descriptors, such as shape and margin (along with their morphological features), are adopted in BI-RADS. Studies of breast imaging are allotted one of seven categories of BI-RADS assessment [24] as shown below:

- BI-RADS 0 (Assessment Incomplete)—Need further assistance.

- BI-RADS 1 (Normal)—No evidence of lesion.

- BI-RADS 2 (Benign)—Non-cancerous lesion (calcified lesion with high density).

- BI-RADS 3 (Probably benign) —Non-calcified circumscribed mass/obscured mass.

- BI-RADS 4 (Suspicious abnormality)—Microlubulated mass.

- BI-RADS 5 (High probability of malignancy)—Indistinct and spiculated mass.

- BI-RADS 6 (Proven malignancy)—Biopsy-proven malignancy (to check the extent and presence in the opposite breast).

Limitations of BI-RADS: The BI-RADS assessment is subjective. Several studies reported an anatomical variability in interpreting mammograms before the use of the BI-RADS lexicon, and it was not improved with the help of BI-RADS [25]. Beam et al. [26] conducted a study on the mammograms of 79 women, out of which 45 were cancerous. One hundred and eight radiologists reviewed these mammograms. The authors have reported that mammogram reading sensitivity and specificity varied from 47% to 100% and 36% to 99%, respectively. In another study, Berg et al. [27] presented intra- and inter-observer variability amongst five expert radiologists. The assessment of the lesions was highly variable. The readers agreed on only 55% of the total 86 lesions. Finally, Geller et al. [28] presented a study to check whether mammographic assessments and recommendations are appropriately linked or not as per BI-RADS. The study highlighted that BI-RADS 3 category had the highest variability.

3. Mammogram Datasets

This section briefs the publicly available mammography datasets that researchers use to detect and/or classify suspicious regions. Table 1 depicts a summary of the most cited and commonly used datasets. Sample images from these datasets are shown in Figure 3.

Table 1.

List of commonly used mammogram datasets and reference URLs.

Table 1.

List of commonly used mammogram datasets and reference URLs.

| Origin and Year | Total Cases | Total Images (Approx) | View Type | Image Type | Annotation | Reference Link for the Dataset | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SureMaPP | UK, 2020 | 145 | 343 | MLO | DICOM | Centre and radious of circle enclosing the abnormality | https://mega.nz/#F!Ly5g0agB!%E2%80%91QL9uBEvoP8rNig8JBuYfw (accessed on 27 October 2020) |

| DDSM | USA, 1999 | 2620 | 10000 | MLO, CC | LJPEG | Pixel level boundary around abnormality | http://www.eng.usf.edu/cvprg/Mammography/Database.html (accessed on 31 May 2021) |

| CBIS-DDSM | USA, 1999 | 6775 | 10239 | MLO, CC | DICOM | Pixel level boundary around abnormality | https://wiki.cancerimagingarchive.net/display/Public/CBIS-DDSM (accessed on 31 May 2021) |

| INBreast | Portugal, 2011 | 115 | 422 | MLO, CC | DICOM | Pixel level boundary around abnormality | http://medicalresearch.inescporto.pt/breastresearch/GetINbreastDatabase.html (Link is taken from the base paper. Accessed on 31 May 2021) |

| MIAS | 161 | 322 | MLO | PGM | Centre and radious of circle enclosing the abnormality | https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/250394 (accessed on 31 May 2021) | |

| BCDR | Portugal, 2012 | 1734 | 7315 | MLO, CC | TIFF | Unknown | https://bcdr.eu/information/about (accessed on 31 May 2021) |

| IRMA | Germany, 2008 | Unknown | 10509 | MLO, CC | Several | Several | https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/6915/1/Toward-a-standard-reference-database-for-computer-aided-mammography/10.1117/12.770325.short?SSO=1 (accessed on 31 May 2021) |

| BancoWeb LAPIMO | Brazil, 2010 | 320 | 1473 | MLO, CC | TIFF | ROI for few images | http://lapimo.sel.eesc.usp.br/bancoweb (assessed on 31 May 2021) |

3.1. SureMaPP

SureMaPP [29] is a recently published dataset of mammograms with around 343 images manually annotated by experts in the field. Two different devices capture this dataset’s images: GIOTTO IMAGE SDL/W and FUJIFILM FCR PROFECT CS. Mammograms are available with two different spatial resolutions: 3584 × 2816 pixels and 5928 × 4728.

3.2. DDSM

The digital database of screening mammography (DDSM) [30] is a very old mammogram dataset. It consists of 2620 mammography studies from hospitals and medical universities in the U.S. Each case includes standard views, such as the mediolateral oblique (MLO) view and craniocaudal (CC) view for the left and right breast.

3.3. CBIS-DDSM

Curated Breast Imaging Subset of DDSM (CBIS-DDSM) [31] is a modified and standardised version of DDSM. Images of CBIS-DDSM are uncompressed and converted into DICOM format. This dataset includes an updated region of interest (ROI) segmentation and bounding box. Other pathological details, such as type of mass, grade of tumour and cancer stage, are included in the dataset.

3.4. INBreast

INBreast [32] has a total of 410 images acquired at the Breast Centre in CHSJ, Porto. As for CBIS-DDSM, DICOM format images with both MLO and CC views are provided. All images are annotated and validated by expert clinicians. Currently, Universidade do Porto has stopped supporting the dataset, but researchers may have access to the dataset by requesting the same.

3.5. MIAS

The Mammographic Image Analysis Society (MIAS) [33] dataset consists of 322 screening mammograms. Annotations are available in a separate file containing the background tissue type, class and severity of the abnormality, x and y coordinates of the centre of irregularities, and the approximate radius of a circle enclosing the abnormal region in pixels.

3.6. BCDR

The Breast Cancer Digital Repository (BCDR) [34] is a public mammogram dataset containing 1734 patient cases. These cases are classified as per Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System (BIRADS). BCDR comprises two repositories: Film Mammography-Based Repository (BCDR-FM) and Full Field Digital Mammography-Based Repository (BCDR-DM). BCDR-FM contains 1010 patient cases with both MLO and CC views. BCDR-DM is still under construction. The BCDR dataset can be accessed by registering on the dataset website.

3.7. IRMA

The IRMA [35] dataset was developed from the union of various other datasets, such as DDSM, MIAS, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), and routine images from the Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule (RWTH) Aachen. Images of this dataset are also available with both views. The dataset contains all types of lesions. IRMA is enriched with ROI annotations, which make the dataset suitable for supervised deep learning approaches.

3.8. BancoWeb LAPIMO

The BancoWeb LAPIMO [36] dataset is equipped with a total of 320 cases and 1473 images with MLO and CC views. Pictures of the dataset are grouped into the following categories: normal, benign and malignant. Annotations and patients’ background information are provided with BI-RADS. Annotations in the form of ROI are available for just a few images, while a textual description of the findings is available for all images. BI-RADS mammograms are in TIFF format.

4. Related Techniques

The scientific literature offers a wide variety of approaches for biomedical image processing tasks. Computer-aided detection (CADe) helps to detect regions of interest clinically from images. Computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) solutions measure the malignancy of masses [37]. CADe identifies suspicious regions and classifies a detected region as a mass or non-mass. CADx identifies a mass as a malignant or a benign one; it helps radiologists recommend biopsy or other follow-ups and treatment planning [38]. This section provides readers with a list of the state-of-the-art methods and techniques to detect suspicious regions from mammogram images. More precisely, it is noticed that most approaches in the scientific literature can be grouped into three prominent families. The following sections focus on methods relying on different techniques: the extraction of low-level image features, machine learning models, and deep learning models. For the sake of clarity, we want to highlight that in our work, we focus on methods for detecting suspicious regions in mammograms. However, we also consider those mammogram patch classification methods that have a model or architecture trained over small-sized image patches. We include them in this paper because those methods classify tiny areas of mammograms by labelling them as suspicious or non-suspicious. They return patches as classified, small enough to have them suitable for locating suspicious areas in the whole mammogram image.

4.1. Low Level Image Features

The detection of suspicious regions is accomplished with different approaches; the main focus in this subsection is to provide the reader with those techniques that rely on the extraction of low-level image features, such as shapes, texture and local keypoint descriptors. Furthermore, articles based on low level image features are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3.

4.1.1. Shape Based Features

A non-negligible number of techniques for the detection of mammogram’s suspicious regions rely on the analysis of shape features, such as concavity, fractals, compactness, and morphological operators. The following subsections group shape-based feature analysis methods into two main categories: (1) techniques that rely on the numerical analysis of shape descriptors; and (2) techniques that employ shape descriptors to feed classification systems and neural networks.

Shape Descriptor Analysis Approaches

In this subsection, methods relying only on the numerical analysis of shape descriptors are presented. Raguso et al. [39] tackled the classification of breast masses by employing fractal analysis. Due to differences in shape complexity of breast masses contours, the fractal dimension is adopted as a discriminating feature for the purpose. Eltonsy et al. [40] reported that the growth of a mass forms concentric layers around activity areas in breast parenchyma structures; they proposed the so-called multiple concentric layers (MCLs) method to detect those activity areas. Morphological analysis of the concentric layer model is the cornerstone of the MCLs detection algorithm. There are three fundamental assumptions that guide the design of the MCLs algorithm. First, it is assumed that the focal activity layer is the brightest that and its evolving concentric layers tend to grow dimmer. Second, the morphology of the focal layer contains useful information regarding the presence of a potentially malignant mass. Third, if the relative incidence of a focal area with MCLs morphology is low in the breast region, then there is a higher probability that this area represents a true abnormality. Rangayyan et al. [41] tackled the detection of mammograms’ masses, using a boundary segmentation approach. They went first to separate major portions of the boundary and labelled them as concave or convex segments. Features were computed through an iterative procedure for polygonal modelling of the mass boundaries. The latter allows analysing shape features localised in each segment. Rangayaan et al. proposed a spiculation index based on the concavity fraction of a mass boundary and the degree of the narrowness of spicules. The spiculation index, fractional concavity and the global shape feature of compactness were combined for the boundary segmentation task. Chakraborty et al. [42] focused their efforts on the detection of the pectoral muscle from mammograms. The proposed method first approximates the boundary by a straight line. Within a selected region, maximum discontinuity points are determined along each horizontal line, based upon the weighted average gradient. An adaptive shape-based method is then applied to divide these points into a number of bands. The band with the maximum number of points is considered the most probable band containing probable pectoral edge points. A straight line is then estimated based upon the probable pectoral edge points. Surendiran and Vadivel [6] analysed the distribution of shape features, such as eccentricity, elongatedness, circularity1 (which measures how much a mass resembles a circle), circularity2 (which measures how much a mass resembles an ellipse), compactness, standard deviation, and dispersion to build on shape characteristics descriptors. Mustra et al. [43] proposed a method based on morphological operators and geometry for accurate nipple detection in craniocaudal mammograms.

Shape Descriptors for Classification Systems

This subsection aims to list and describe those classification systems fed with shape-based features. Li et al. [44] introduced a method to convert 2D breast mass’ contours in mammography into 1D signatures. The method provides a descriptor for contour features and breast mass regularity. The whole 1D signature is divided into subsections. The contour descriptor consists of four local features extracted from subsections. The contour descriptor is the root mean square (RMS) slope. On top of that, KNN, SVM and ANN classifiers are used to classify benign and malignant breast masses. Elmoufidi et al. [45] proposed a multiple-instance learning method based on the analysis of combined texture and shape features to classify malignant and benign masses in the breast. Elmoufidi et al. addressed the classification using features such as the equivalent circle of ROI (region of interest) and the bounding box, which is defined by the smallest rectangle containing the ROI. Zhang et al. [46] proposed a method that relies on two main steps encompassing eleven features: nine features from both spatial and morphology domains, and two cluster description features. The first stage plays a critical role in detecting coarse visual features, while the second stage allows for detecting finer analysis and classification. Soltanian-Zadeh et al. [47] ran microcalcification classification by comparing multi-wavelet, wavelet, haralick, and shape features. Several useful properties, such as symmetry, orthogonality, short support, and a higher number of vanishing moments, simultaneously can be retrieved by using the mentioned features. The usefulness of these properties is well known in wavelet design. The symmetric property allows symmetric extension when dealing with the image boundaries. Felipe et al. [48] carried out experiments to test out the effectiveness of Zernike moments as shape descriptors for mammograms’ classification. Zernike moments calculated from the pixels’ values of images retain pattern information related to shape. Soltanian-Zadeh et al. [49] presented two image processing methods for differentiating benign from malignant microcalcifications in mammograms. The gold standard method for differentiating benign from malignant microcalcifications is a biopsy, which is invasive. The goal of the proposed methods is to reduce the rate of biopsies with negative results. In the first method, the authors extracted 17 shape features from each mammogram. These features are related to the shapes of individual microcalcifications or to their clusters. In the second method, the co-occurrence method of Haralick achieves the extraction of 44 texture features from each mammogram. The best features from each set are extracted with a genetic algorithm by maximising the area under the ROC curve. This curve is created using a k-nearest neighbour (kNN) classifier and a malignancy criterion. The final step consists of comparing ROCs with the largest areas obtained, using each technique. Zyout et al. [50] presented a shape-based approach for the classification of MC (microcalcification) clusters. The proposed diagnosis scheme applies an embedded feature selection framework, called PSO-kNN (particle swarm optimisation and k-nearest neighbours), representing a unified scheme for accomplishing the feature selection and the classifier learning tasks. Sahiner et al. [51] dealt with the characterisation of breast masses on mammograms by developing a three-stage segmentation method based on clustering, active contour, and spiculation detection stages. After segmentation, extracted morphological features described the shape of the mass. Texture features were also extracted from a band of pixels surrounding the mass. Stepwise feature selection and linear discriminant analysis were employed in the morphological, texture, and combined feature spaces for classifier design. Junior et al. [52] proposed a method to detect breast cancer through diversity analysis, geostatistical and concave geometry (alpha shapes). Furthermore, they assessed the effectiveness of each feature, using support vector machine (SVM) in the MIAS and DDSM databases.

Pros and Cons

Some pros and cons for both approaches can be noticed by observing Table 2. Overall, those techniques based on the analysis of shape descriptors achieve good results in terms of accuracy. Raguso et al. [39] score 0.97 in the area under ROC. Nevertheless, the results are reported only on a local dataset, and no performance metrics are provided over publicly available databases. The experiments run by Rangayyan et al. [41] showed a certain level of accuracy and reliability of shape descriptors, such as spiculation index, fractional concavity and compactness on mass classification (accuracy of 80%) on MIAS. The method of Chakraborty et al. [42] reported very few false positives and false negatives in the detection of the pectoral muscle by using lightweight features, such as the average gradient. A morphological descriptor–based technique by Eltonsy, N.H. et al. [40] revealed high accuracy rates on DDSM, even though only the specificity is provided and no information about the number of false positives is given. Mustra et al. [43] used morphological descriptors and geometrical properties by which a 97.92% detection rate for nipple detection task was achieved in craniocaudal mammograms from a local dataset. The performance of the methods mentioned above shows reasonable accuracy rates and is lightweight. On the other side, their results show lower accuracy than the methods proposed by Li et al. [44], Zhang et al. [46], Sahiner et al. [51], and Junior et al. [52], which feed shape descriptors into SVMs, clustering, k-nearest classifier, etc. The method of Junior et al. showed a high sensitivity and detection rate on two different publicly available datasets (DDSM and MIAS), using geostatistical and concave geometrical descriptors and SVM.

4.1.2. Texture-Based Features

Texture indicates visual patterns in visual content. Because of the complexity and diversity in natural images, texture analysis and description still represents a challenge [7]. In this section, the readers are provided with a description of texture analysis-based methods for detecting suspicious regions in mammograms. Like the previous section, this section is further divided into two subsections. The first one groups those methods relying on the analysis of texture feature descriptors, while the second one encompasses techniques, where the texture descriptors feed into the classification systems.

Texture Descriptors’ Analysis

Ramos et al. [53] proposed a technique that relies on texture features extracted from co-occurrence matrices, wavelet and ridgelet transform of mammogram images. They focused their efforts on detecting suspicious regions out of craniocaudal mammograms. Properties, such as entropy, energy, average, sum variance and cluster tendency, are calculated on top of texture features. The features mentioned above also undergo a GA (genetic algorithms) check to assess their effectiveness. Haindl and Remeš [54] dealt with enhancing suspicious breast tissue abnormalities, such as microcalcifications and masses, by helping radiologists detect developing cancer. They addressed the task, using a two-dimensional adaptive causal auto-regressive texture model to represent local texture characteristics. Furthermore, they used the Karhunen-Loeve transform to combine more than 200 local textural features (sensed with different frequency bands) into a single multi-channel image. Zheng et al. [55] presented a lattice-based approach that relies on a regular grid virtually overlaid on mammographic images. They used a local window centred on each lattice point to extract texture features within the breast. Tai et al. in [56], presented an automatic CADe (computer-aided detection) system that relies on local and discrete texture features for mammographic mass detection. In greater detail, Tai et al. [56] segmented adaptive square suspicious areas. In their study, the co-occurrence matrix and optical density transformation are used to describe suspicious regions with local texture and discrete photometric distributions. The same features undergo stepwise linear discriminant analysis to rank abnormal areas. Mudigonda et al. [57] introduced the concept of texture flow-field analysis to the mammogram analysis.

Texture Descriptors for Classification Systems

In the methods described in this subsection, texture descriptors feed into classifiers, logistic regression, clustering functions, and self-organising maps to classify suspicious regions in mammographic images. Farhan and Kamil [58] demonstrated the usefulness of texture analysis in mammograms to discriminate breast masses from normal tissue. They conducted their study on the MIAS [33], using LBP (local binary pattern) and a logistic regression classifier. Zheng et al. [55] as well as Mohanty et al. [59] extracted a range of statistical and structural (local binary pattern, and fractal dimension) features to carry out experimental detection of suspicious regions in mammograms. An association between lattice-based texture features and breast cancer was evaluated using logistic regression. Li et al. [60] presented a texture feature descriptor for mammographic image classification into different breast density categories. More precisely, they adopted the commonly used local binary patterns (LBP) and considered more feature details by including its variant, local quinary patterns (LQP). The descriptor turned out to be robust against rotations and translations. Quintanilla-Domínguez, et al. [61] analysed regions of interest (ROI) in mammograms by using the top-hat transform to enhance the ROI. Top-Hat transform increases the contrast between the background and well-defined/circumscribed masses, ill-defined masses, speculated masses, architectural distortions and asymmetries as described in MIAS [33]. After applying the top-hat transform with a sized structuring element, the method carries out a window-based extraction of statistical moments, such as mean and standard deviation. K-means clustering and SOM (self organising maps) address grouping and labelling tasks. Hung and Lin [62] provided the scientific community with a GPU computing implementation of GLRLM to speed up the extraction process of texture features from mammograms. Gaussian smoothing and sub-sampling operations were employed to pre-process mammograms by Mudigonda et al. [57]. Mass segmentation is accomplished by establishing intensity links from the central portions of masses to their spatial neighbourhood. Mammogram regions are classified with flow orientation in adaptive areas of pixels across the boundaries of masses. A logistic regression system ingests the output of the last step. Biswas and Mukherjee [63] recognised architectural distortions in mammograms with a generative model carrying out the extraction of distinctive textures. The first layer of the architecture in this study consists of a multiscale-oriented filter bank that draws filter vectors as texture descriptors. The second layer of the proposed model is responsible for textural primitives’ representation tackled with a mixture of Gaussians.

Pros and Cons

Pros and cons of the previous section methods are described here. It is noticeable how texture descriptors, such as co-occurrence matrices, wavelet and ridgelet transforms [53], local texture features and KL transforms [54], lattice-based features [55], GLCM features and density features [56] and texture flow-field [57] perform reasonably well, in order, on mass classification, texture irregularity enhancement, density percentage in mammograms. Nevertheless, Ramos et al. [53] reach 0.9 in the AUC on a local dataset, while no performance metrics are given on public databases. The method of Haindl et al. [54] showed a remarkably high percentage of false positives. The method of Zheng et al. [55] achieved AUC values within the range [0.60, 0.74]. Tai et al. [56] obtained 99% sensitivity on DDSM but no data about false positives’ rates are given. With the only exception of local patterns [60], when texture features feed into classification systems [58,59,61], they return noticeably high rates of accuracy (93.6% on DDSM), sensitivity and specificity (greater than 99% on MIAS). However, as in the method of Biswas et al. [63], the classification systems’ performance may slightly drop when other texture features and descriptors are used (mixture of Gaussians).

4.1.3. Local Keypoint Descriptors

Local keypoints and their corresponding descriptors, such as SIFT [64] and SURF [65], have been widely adopted over many computer vision topics [66]. Since their first introduction in 1999, a lot of water went under the bridge [64]. Different methods for image retrieval, image registration, object recognition, object classification, pattern recognition, robot localisation, wide baseline matching, and video shot retrieval ingest keypoint descriptors. Since then, biomedical researchers have started detecting regions of interest in images with local keypoint descriptors because of their robustness against varying illumination conditions and spatial noise distribution, geometric and photometric transformations in images. As far as it concerns the subject of this survey, several state-of-the-art methods rely on local keypoint descriptor. The following two subsections group methods and techniques into two main approaches: local keypoint descriptor analysis, and local keypoint descriptors for classification systems.

Local Keypoint Descriptor Analysis

Jiang et al. [67] proposed a method specifically for a query mammographic region of interest (ROI). They compared SIFT descriptors extracted from the ROI to a vocabulary tree, which stores all the quantised features of previously diagnosed mammographic ROIs. The method improves its performances with contextual information in the vocabulary tree. Jiang and Zhang conducted experiments on 11,553 mammographic ROIs. Guan et al. [68] focused on the liability of SIFT keypoints on microcalcification segmentation in MIAS dataset images. In greater detail, they fine-tuned the SIFT extraction parameters over MIAS by looking into the following steps: scale-space extrema detection, keypoint localisation, orientation assignment, and keypoint descriptor. Insalaco et al. [69] proposed a SURF-based method for detecting suspicious regions in mammograms. Their method is unsupervised and it relies on three main steps: pre-processing, feature extraction and selection. The histogram-based image intensity threshold assumes a relevant role in their method. The method allows extracting features from two versions of the same mammogram with different dynamic grey intensity levels.

Local Keypoint Descriptors for Classification Systems

In this section methods, local keypoint descriptors feed into classification systems. Utomo et al. [70] tested out some well-known scale and rotation invariant local features, such as SIFT, SURF, ORB, BRISK, and KAZE, to check which of them might replace the convolutional layers of CNN models. They kept the fully connected layers of the CNN model as the classifier, while they removed the convolutional layers. Furthermore, they assigned the high-level feature maps at the flatten layer with scale and rotation invariant local features. Utomo et al. [70] carried out experiments on MIAS dataset images. SIFT and SURF reportedly exhibited state-of-the-art performances when paired to VGG16 and MobileNetV2 models. Salazar-Licea et al. [71] presented a technique that combines SIFT features and K-means clustering to detect ROIs in mammograms. Their method first enhances the image quality through image thresholding and contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE). Then, they locate regions of interest in mammograms, using SIFT and binary robust independent elementary features (BRIEF) and feed keypoint coordinates into K-means clustering. Bosch et al. [72] presented a technique to model and classify breast parenchymal tissue. The authors analysed the spatial distribution of different tissue densities in an unsupervised manner by using SIFT and texture features. They also used both a classifier based on local descriptors and the probabilistic latent semantic analysis (pLSA) to detect meaningful aspects in mammograms. The MIAS and DDSM datasets were used to compare performances of different state-of-the-art methods to theirs. Liasis et al. [73] provided the scientific community with a method to investigate statistical distributions of different texture descriptors with support vector machines (SVMs) for breast density classification in mammogram images. They tested out features, such as SIFT, LBP (Local Binary Patterns) and texton histograms. TMatos et al. [74] conducted a study on the effectiveness of different features, such as (SIFT), speed up robust feature (SURF), oriented fast and rotated BRIEF (ORB) and local binary pattern (LBP) descriptors for local feature extraction in mammograms. The mentioned features are represented with the BOF (bags of features) approach to decrease data dimensionality. The same features fed support vector machine (SVM), adaptive boosting (Adaboost) and random forests (RF) for mammogram patch classification. Deshmukh and Bhosle [75] carried out some experiments on mammogram classification with SURF: they optimised SURF, ran the mammogram image classification with an associative classifier ingesting the optimised SURF. SURF descriptors and spatial distance measurements are taken into account to discard some regions. Mammogram classification relies on SURF features and the random forest method. Abudawood et al. [76] conducted experimental campaigns to assess LBP (local binary pattern) effectiveness against other image features, such as SURF, sparse coding and BRISK, using Gaussian process, k-nearest neighbours, support vector machines and AdaBoost.

Pros and Cons

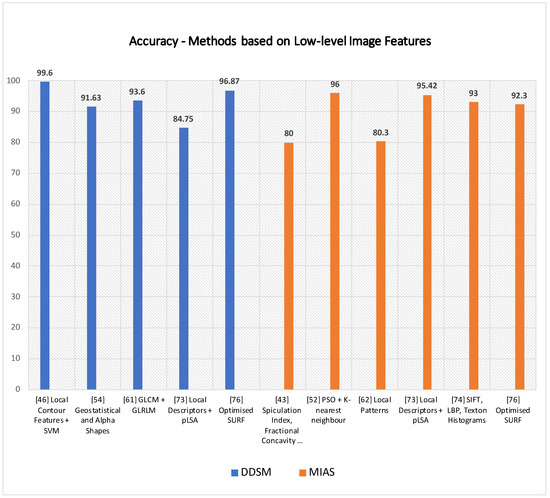

As for those methods based on shape and texture features, a further subsection provides the paper with the pros and cons of local keypoint-based methods. The method of Jiang et al. [67] successfully detected masses on a local mammogram dataset of 11,553 ROIs, achieving 90.8% accuracy by using an approach based on SIFT and vocabulary tree. It would be interesting to assess its performances on a public dataset to compare it with other state-of-the-art techniques on the task. SIFT descriptors were also adopted for detecting microcalcification by Guan et al. [68], but no accuracy metrics and comparison to other techniques are provided. Assuming that the method of Insalaco et al. [69] mainly relies on histogram-based image intensity thresholds, it would be interesting to know how robust the method is over datasets with different features. Utomo et al. [70] conducted noteworthy experiments to compare other keypoint descriptors feeding into FCN, and they achieved 100% sensitivity and specificity on MIAS for mass classification. It would be interesting to assess their performance on other datasets such as InBreast, DDSM and SuReMaPP. Bosch et al. [72] used local keypoint and pLSA for classifying parenchymal tissue on MIAS and DDSM. It is noticeable how performance accuracy rates drop by 13 percent from MIAS 95.42% to DDSM 84.75% showing better suitability of the proposed method for the MIAS dataset. Experimental results show higher accuracy rates for methods that feed local keypoint descriptors into classification systems at the expense of a higher computational cost. However, having most of the classification overall high accuracy performances, their accuracy rates drop when run over different datasets. In addition, the method of Deshmukh et al. [75] seems to have the most well-balanced accuracy rate over two datasets, such as DDSM and MIAS. It obtained, respectively, 92.30% and 96.87% accuracy rates on MIAS and DDSM. A graph showing accuracy rates of some methods based on low-level image features are shown in Figure 5. Due to heterogeneity in the metrics and datasets provided by the reference articles, only some techniques having the same datasets and metrics are plotted. More details are provided in Table 2 and Table 3 for a broader range of techniques.

Figure 5.

Some techniques based on the analysis of low-level features are plotted above according to their accuracy rates on DDSM and MIAS.

Table 2.

Methods based on low-level image features (a).

Table 2.

Methods based on low-level image features (a).

| Reference | Technique | Task Performed | Dataset | Performances |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [39] | Fractal Analysis | Mass Classification | Local Dataset San Paolo Hospital, Bari, Italy | Area under ROC: 0.97 |

| [44] | Local contour features, +SVM | Mass Classification | DDSM | Accuracy: 99.6% |

| [45] | Multiple instance learning: textural and shape features + K-means | Mass Classification | DDSM and MIAS | Sensitivity: 95.6% on DDSM 94.78% on MIAS |

| [46] | Spatial and Morphology domain features | Microcalcification clusters’ detection | USUHS | Sensitivity: 97.6% |

| [47] | Multiwavelet, wavelet, Haralick, and shape features | Microcalcification classification | Nijmegen Database | Area under ROC: 0.89 |

| [48] | Zernike moments | Classification of mammographic mass lesions | Local dataset | Precision: 80% Recall: 20% |

| [41] | Spiculation Index, Fractional Concavity, Compactness | Mass Classification | MIAS | Area under ROC: 0.82 Accuracy: 80% |

| [42] | Average Gradient and Shape Based Feature | Pectoral Muscle Detection | MIAS a local database | False Positives (FP) and False Negatives (FN): FP on MIAS 4.22%, FN on MIAS 3.93%; |

| [49] | Shape features and Haralick features. | Microcalcification classification | Nijmegen Database | Area under ROC: Shape Features 0.82; Haralick Features 0.72 |

| [50] | Swarm optimisation (PSO) algorithm and k-nearest classifier | Microcalcification cluster detection | MIAS and a local dataset from the Bronson Methodist hospital | Accuracy: 96% on MIAS, 94% on BMH |

| [51] | Texture and Morphological Features | Mass Classification | local database | Area under ROC: 0.91 ± 0.02 |

| [40] | Morphological Features | Mass Detection | DDSM | Sensitivity: 92% |

| [52] | Geostatistical and concave geometry (Alpha Shapes) | Mass Detection | MIAS and DDSM | Detection rate: 97.30% on MIAS and 91.63% on DDSM |

| [53] | Co-occurrence matrices, wavelet and ridgelet transforms | Mass Classification | Local Database | AUC = 0.90 |

| [58] | Local Binary Pattern | Breast Mass Recognition | MIAS | Sensitivity 99.65% Specificity 99.24% |

| [54] | Local texture feature and KL Transform | Enhancing texture irregularities | Inbreast | True Positive 96% False Positive 65% False Negative 4% |

| [59] | GLCM and GLRLM features | Mass Classification | DDSM | Accuracy 93.6% |

| [43] | Pixel intensity and Morphological Features | Nipple detection | 144 Mammograms (Local Dataset) | Detection Rate 97.92% |

Table 3.

Methods based on low-level image features (b).

Table 3.

Methods based on low-level image features (b).

| Reference | Technique | Task Performed | Dataset | Performances |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [55] | Texture Feature and Lattice Points | Mammographic Percent Density | Local Database | Area under Curve: 0.60–0.74 |

| [60] | local patterns | Mass Classification | INBreast and MIAS | Accuracy: 82.50% on INBreat 80.30% on MIAS |

| [61] | morphological Top-Hat transform | mass and microcalcification detection | MIAS | Sensitivity and Specificity: 99.02% 99.94% |

| [62] | Texture Features analysis with GPU | Texture analysis in mammograms | DDSM and MIAS | CPU and GPU time on each picture |

| [56] | GLCM features and optical density features | Mass Detection | DDSM | Sensitivity 99% |

| [57] | Density Slicing and Texture Flow-Field Analysis | Mass Detection | MIAS | Area under Curve: 0.79 |

| [63] | Mixture of Gaussian distribution for texture analysis in mammograms | Architectural Distortion Detection in Mammograms | MIAS and DDSM | MIAS Sensitivity 85.5% Specificity 81.0% DDSM Sensitivity 89.2% Specificity 86.7% |

| [70] | FC-VGG16 + SIFT, SURF, ORB, BRISK, and KAZE | Mass Classification | MIAS | SIFT + FC MobileNetV2 Specificity 100%; Sensitivity 100%; |

| [67] | SIFT features, Vocabulary Tree and Contextual Information | Mass Classification | Local dataset of 11553 ROIs from Mammograms | Accuracy 90.8% |

| [68] | SIFT features | Segmentation of Microcalcifications | MIAS | - |

| [71] | Scale-Invariant Feature and K-means clustering | ROI (Region of Interest) detection in mammograms | 4 mammograms from MIAS | - |

| [72] | Local Descriptors and (pLSA) | Parenchymal Tissue Classification | MIAS and DDSM | Accuracy on MIAS 95.42%; DDSM 84.75% |

| [73] | SIFT, LBP and Texton Histograms and SVM | Breast Density Classification | MIAS | Accuracy 93% |

| [74] | Bag of Features (BoF) and SVM | Mass Classification | DDSM | Sensitivity 100% Specificity 99.24% |

| [69] | Histogram Specification and SURF features | Mass Detection | MIAS | Sensitivity 0.89 |

| [75] | Optimised SURF | Mass Classification | MIAS and DDSM | MIAS Accuracy 92.30% DDSM Accuracy 96.87% |

| [76] | LBP plus classifiers (KNN, SVM, Gp, AB) | Abnormality Classification | DDSM | Precision 94.60% Recall 95% |

4.2. Feature Engineering

Feature engineering allows formalising meaningful features from data. Machine learning models generally use these features for a variety of tasks. This technique transforms raw data into features that better represent the target to be learned. It features in the pipeline of many machine learning methods. That being said, feature engineering is specific to a problem and is error-prone. Moreover, finally crafted features are limited by user creativity. The manual feature engineering approach aims to create or build features one at a time with the help of domain knowledge as depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Manual feature engineering process: Features are crafted one at a time using domain knowledge by understanding underlying data.

The logic for crafting features is problem dependent and needs to change for every new application and underlying dataset. Feature engineering comprises various representative tasks, such as feature transformation, feature generation and extraction and feature selection. Feature engineering can be applied to all types of data and is frequently used with images and text. Chandakkar et al. [77] discussed various feature engineering aspects for image data, including texture, shape, colour features, etc. Some methods relying on these features are described in Section 4.1. In manual feature engineering, well-defined characteristics, such as texture, shape, and other low-level image features are constructed from input images to define imaging expression [78,79]. Though earlier researchers have used manually crafted features for various tasks, it is not always easy and possible to transform the medical imaging domain to precise scientific descriptors for manual feature engineering. This task becomes even more challenging when the field of application is not adequately understood [80].

When compared to deep learning, feature engineering needs pre-established descriptors or features of images or data. As far as it concerns medical images, this task is much more constrained because understanding this domain is mainly nonfigurative and difficult to define and set out with accurate scientific descriptors. With massive training data, deep learning automatically acquires inherent imaging features and uses these features to represent the outcome. Studies [80,81,82,83] show that feature extraction with the help of deep learning approaches presents better results as compared to pre-established descriptors in varieties of the application domain. An end-to-end deep learning model proposed by Arefan et al. [80] focuses on predicting short-term breast cancer risk using mammogram images. The authors used GoogleNet with the LDA model to extract deep features. As deep learning is considered a black box system, feature interpretation is not a straightforward process. Authors have used feature activation maps to highlight the essential and related regions in the images concerning the specific prediction tasks. Dhungel et al. [84] developed a method to learn the mammogram features automatically. Authors have used two-step training; pre-training based on the learning of a regressor that estimates the large set of handcrafted features that follow a fine-tuning stage that learns the classification of breast masses. It was shown in the study that the proposed method performs well when comparing to machine learning models with manually crafted features. Arora et al. [85] proposed a method for automatic classification of mammograms using ’deep features’. Features extraction and classification is carried out with deep ensemble learning and neural network classifier. The features that the ensemble model extracts are then optimised into a feature vector. Further, these features are classified with the help of neural network classifiers. The proposed model achieved an accuracy of 88%.

4.3. Machine Learning

In this section, several machine learning methods for classification and detection of suspicious regions are encompassed (see Table 4. In greater detail, methods relying on artificial neural networks, clustering techniques and classifiers such as SVM are tackled in the following subsections.

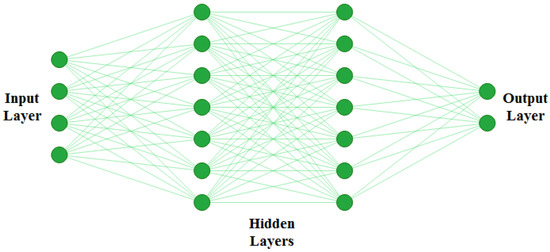

4.3.1. Artificial Neural Networks

The artificial neural network (ANN) is simply a computing system inspired by the biological neural network [86]. ANN works similarly to the biological neural networks of the human brain but does not resemble the same. The basic structure of ANN is depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Basic structure of ANN. ANNs are generally defined as having three different layers; an input layer, hidden layer, and output layer. The input layer reads in data values from the user. There can be multiple hidden layers where actual learning takes place, and finally there is an output layer which presents the final result of the ANN.

The functioning of ANN consists of two main steps: forward pass and backpropagation. During forwarding pass, feature values () are multiplied by weights (), and the activation function is applied to each neuron. That generates a weighted output . The next layer ingests , and the process repeats till the output layer is reached. A typical ANN architecture can have one input layer, multiple hidden layers, and one output layer. Artificial neural networks are trained using backpropagation, which relies on the previous layer feedback. Finally, in the output layer, ground truth data are compared with the output generated by ANN. The loss function is responsible for determining the gap between results and labelled data. For updating weights, this loss is then transmitted to the network during the next iteration [87]. ANNs are among the most commonly used AI approaches for building CADe systems for mammogram analysis. It can be applied in different ways to mammograms; first, as a feature extractor and, second, as a classifier to directly classify the region of interest (ROI) of an input mammogram [88].

Artificial Neural Networks for Mammogram Analysis

In this subsection, ANN methods for detecting suspicious regions in mammograms are described. Wu et al. [89] inspected the potentiality of ANN as a decision-making tool to assist radiologist on mammogram analysis. In greater detail, the authors trained a three-layer feedforward neural network to analyse mammograms, using hand-labelled features by expert radiologists. Forty-three features allowed to reach 0.95 for the area under the ROC curve on lesion classification. An ANN-based system to analyse interpreted radiographic features from mammograms was proposed by Fogel et al. [90]. The model was trained with evolutionary programming to indicate the presence of malignancies. For suspicious masses, the model returned average area under ROC values of 0.91 with a specificity of 62% and sensitivity of 95%. Halkiotis et al. [91] proposed a model to detect clustered microcalcification using mathematical morphology and ANN. Morphological operators remove noise and regional maxima. The authors reviewed two models based on ANN; a two-layer MLP (multi-layer perceptron) and radial basis function neural networks (RBFNN) with variable hidden layers. With 10-hidden nodes, MLP could score a 94.7% positive detection rate and 0.27% false positives per image. Ayer et al. [92] presented an overview of ANN in mammography interpretation and diagnostic decision making and showed several limitations of existing ANN-based systems for detection and diagnosis. Quintanilla-Domínguez et al. [93] tackled the detection of microcalcifications using adaptive histogram equalisations and a self-organising map (SOM). Computer simulations confirmed the model’s capability and effectiveness to detect microcalcifications from mammograms. Papadopoulos et al. [94] proposed an approach for detecting and characterising microcalcification clusters from digitised mammograms. The method consists of three stages; cluster detection, feature extraction and classification that provides the final characterisation. The classification stage rule-based classifier, such as ANN and SVM, were evaluated using ROC analysis. The use of extra features extracted from the mammogram itself or collected from patient data could help the diagnostic process. García-Manso et al. [95] developed a system to detect and classify masses from mammograms. In this method, Independent Component Analysis (ICA) method is used to extract blind features, and neural networks run the classification process. Experimental results showed that the employment of heterogeneous datasets takes to variation in performance. Hupse et al. [96] developed an ANN-based CAD system to detect abnormal mass and architectural distortions from mammograms. The authors compared the results of human readers and the CAD system. The performance of the CAD system was close to that of certified experts in the field. One more CAD system for mammographic image feature analysis and screening is proposed by Tan et al. [97]. The system relies on ANN to predict the probability of a mammogram being positive. The authors used a ten-fold cross-validation method to test the performance of the system. The computed area under the ROC curve equalled 0.779 ± 0.025. Mahersia et al. [98] introduced a mass detection technique based on three steps: enhancement, characterisation and classification. The enhancement step helps to analyse breast texture. A Gaussian density function is used in the wavelet domain to segment the breast mass during the characterisation step. Last, a comparative classification method uses backpropagation networks and adaptive network-based fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) techniques.

4.3.2. Clustering Techniques

Image segmentation is an essential task allowing the extraction of objects and their boundaries in a given picture. It is safe to say that segmentation plays such a fundamental role in medical image analysis. A properly segmented region helps practitioners retrieve vital information for the detection of diseases and may help them in surgical planning [99]. Clustering techniques are somewhat similar to classifier methods, except they do not use training data; hence they are called unsupervised methods. These methods iterate segmented images and characterize each class with properties to compensate lack of training data. K-means clustering relies on a simple algorithm, and it is moderately less computationally expensive. It is well suited to mammogram images because most breast regions can be clustered using pixel intensity values [100]. K-means algorithm partitions the dataset into k different clusters that are non-overlapping, and each data point fits into one cluster. Data points are assigned to clusters so that the total sum of the squared distance between the data points and the cluster’s centroid (mean of all data point of that cluster) is minimal. This approach helps to solve the expectation-maximization, where step E assigns the data points to the nearest cluster, and step M is to find clusters’ centroids. The objective function is as follows:

where = 1 for data point if it belongs to cluster k; Otherwise, = 0 and is the centroid of ’s cluster

Clustering Techniques for Mammogram Analysis

A segmentation model was proposed by Kamil and Salih [101] to determine the boundaries of the tumour. The model builds on two algorithms based on clustering methods, such as K-means and fuzzy C-means. The authors employed a lazy snapping algorithm to improve model performances. After testing the model on the MIAS dataset, accuracy rates of 91.18% and 94.12% were achieved by K-means and fuzzy c-means algorithm, respectively. Ketabi et al. [102] presented a model to detect breast masses. It consists of the combination of three different approaches: clustering, texture analysis and support vector machine. Using data cleansing and greyscale enhancement, ROIs are detected and then segmented using spectral clustering. Features such as shape and probabilities are extracted from these segmented sections. For feature selection, the authors opted for genetic algorithms (GA). Finally, for the classification process, linear kernel was used. On the DDSM dataset, the classification accuracy obtained by the classification model is 90%. The segmentation of a region of interest from the image background is quite a complex task. The resulting segmented areas are generally pretty noisy. Kumar et al. [103] handled this issue by proposing a fuzzy c-means based model and incorporating similar superpixels and spatial information. Features of breast tissues such as the size of mass and size of breast ingested the model. The highest accuracy rate obtained was 84.32%. Hybridization of fuzzy c-means algorithm was proposed in [104]. Chowdhary and Acharjya et al. [104] addressed the co-presence of coincident clusters in the same mammogram with a possibilistic and intuitionistic fuzzy c-means.

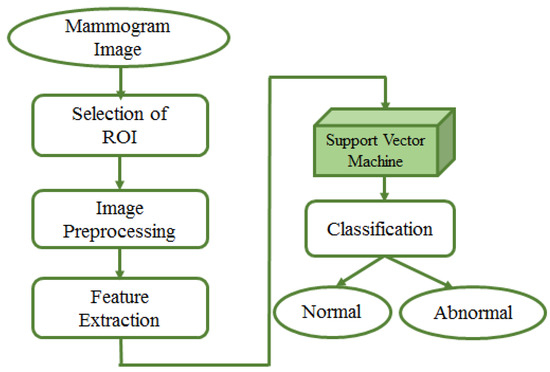

4.3.3. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

In 1992, Boser et al. [105] presented a supervised algorithm for classification that successively evolved into the well-known support vector machines (SVMs) [106]. The key innovations of SVMs were the use of convex optimization, statistical learning theory, and kernel functions. The SVM method has been widely adopted in biomedical image analyses. Fixed-size region of interest (ROI) patches are extracted from mammogram images; then, patches are usually pre-processed for enhancement purposes. Afterwards, a feature extraction step is necessary to ingest SVM to train a model for classification. This entire process is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Mammogram image analysis by SVM. Input to the model is the mammogram image. Fixed-size region of interest (ROI) patches are extracted from mammogram images; pre-processing is done on extracted patches to improve the quality. Afterwards, a feature extraction step is needed to ingest SVM to train a model for classification of patches as benign or malignant.

The main idea of this approach is to find a line called hyperplane in N dimensions, which classifies the input data samples. A hyperplane is an -dimensional subspace for an N-dimensional space. Mathematically, the hyperplane is defined as follows:

Here, d is the number of features, and are feature and weights, respectively. is bias.

The main challenge of this approach is to find a plane called the maximum margin plane, which is necessary for accurate result prediction and generalised classifier. There is always an adjustment between correct classification and a large margin. If the margin is maximised to obtain better quality results, support vectors (data points closer to the plane) may be considered members of the other class. On the other way round, the margin could be narrow if we want an exact classification, which can lead to an improper or lower accuracy level of the model [107]. SVMs are widely adopted techniques for classification and regression task. SVM achieves very high accuracy rates when the data are linearly separable. For nonlinear data, kernel functions remodel nonlinear data to a high dimensional space; afterwards, SVM ingests the remodelled data. Varieties of kernel functions, such as linear, nonlinear, polynomial, and sigmoid are available for the purpose. When using SVM, the selection of kernel function and its parameters is a crucial challenge [108].

SVM for Mammogram Analysis

In this subsection, SVM-based techniques for mammogram analysis are described. Liu et al. [109] proposed the integration of possibilistic fuzzy C-means (PFCM) clustering and a weighted SVM to detect clusters of microcalcification regions. Suspicious regions are extracted using the region growing method and active contour segmentation. For each of these regions, texture and geometry features are obtained. For every sample, weights are calculated according to possibilities and typical values from the PFCM and the available ground truth. Suspicious regions of microcalcification are classified using weighted nonlinear SVM. This method was examined over around 410 images and compared with unweighted SVM. The performance of the model was evaluated based on ROC and FROC curve. The proposed approach could get better results as compared to standard SVM. A team of researcher presented a method in [110] for detecting masses from mammograms. Thresholding, correlation function and SVM tackled the detection process. Pre-processing increased the image contrast using a low pass filter. Wavelet transform with a linear function was used to enhance an image. The authors performed segmentation using thresholding. The post-processing step consisted of shape descriptors and SVM. Finally, SVM was again used for the classification process. Ancy and Nair [111] proposed a technique to detect breast cancer from mammograms using a gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM)–based SVM. After preprocessing a single view mammogram, ROI segmentation and GLCM feature extraction followed the classification process. This method was evaluated using two mammogram datasets named MIAS and University of South Florida Digital Mammography (USFDM). Qayyum and Basit [112] offered a model of breast cancer detection consisting of three main steps such as breast region segmentation (Otsus algorithm), pectoral muscle removal (using canny edge detection) and classification of normal and abnormal tissues (using SVM). Gray level co-occurrence matrices (GLCM) were used for feature extraction. The model was evaluated on the MIAS dataset. Results compared to previously proposed methods showed the reliability of the method of Qayyum et al. A CAD to detect suspicious areas in mammograms and classify them as benign or malignant was proposed by Sharma and Khanna [113]. The preprocessing step fulfilled the background breast region separation. Zernike moments of different orders described fixed-size (128 × 128) patches extracted from input mammograms as feature vectors. SVM eventually classified the extract ROI patches that. The experimental result showed better results obtained with order 20 Zernike moments and an SVM. To detect mammogram image features, Vijayarajeswari et al. [114] used Hough transform, and these features are used as an input to the SVM classifier. This model achieved an accuracy of 94%, which was very good when compared to the accuracy obtained by the LDA classifier (86%). Findings from various articles based on Machine Learning approaches for breast cancer diagnosis are summarised in Table 4. Some techniques are also compared in Figure 9 Due to the heterogeneity of datasets and metrics reported in the reference articles, only the accuracy rates of machine learning and deep learning over DDSM and MIAS are plotted in Figure 9.

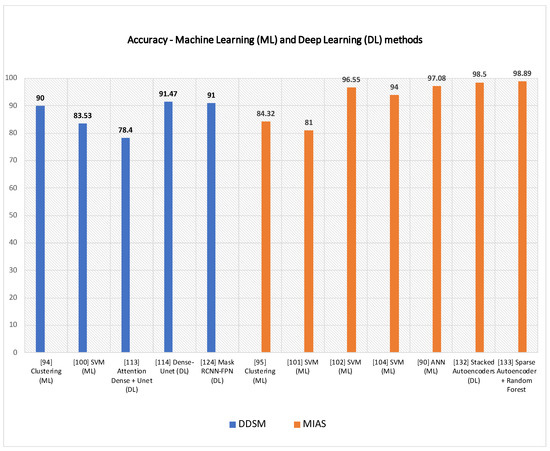

Figure 9.

Some machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques are shown above, according to their accuracy rates on DDSM and MIAS.

Table 4.

Machine learning approaches for breast cancer diagnosis from mammograms.

Table 4.

Machine learning approaches for breast cancer diagnosis from mammograms.

| Reference | Technique | Task Performed | Dataset | Model Performace |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [101] | Clustering | Mass Segmentation | MIAS | K-means: 91.18% Fuzzy c-means: 94.12% |

| [102] | Clustering | Mass Detection | DDSM | Accuracy: 90% |

| [103] | Clustering | Suspicious Lesion Segmentation | MIAS | Accuracy: 84.32% |

| [109] | SVM | Microcalcification Detection | InBreast | ROC: 0.8676 Sensitivity: 92% FPR: 2.3 clusters/image |

| [110] | SVM | Mass Detection, Mass Classification | DDSM | Sensitivity: 92.31% Specificity: 82.2% Accuracy: 83.53% ROC: 0.8033. |

| [111] | SVM | Tumor Detection | USFDM, MIAS | Precision:0.98 Sensitivity: 0.73 Specificity: 0.99 Accuracy: 0.81 Score: 0.758 |

| [112] | SVM | Segmentation, Classification | MIAS | Accuracy: 96.55% |

| [113] | SVM | Abnormality Detection | IRMA, DDSM | IRMA: Sensitivity: 99% Specificity: 99% DDSM: Sensitivity: 97% Specificity: 96% |

| [114] | SVM | Mammogram Classification | MIAS | Accuracy: 94% |

| [89] | ANN | Lesion Classification | Mammography Atlas | ROC: 0.95 |

| [90] | ANN | Mammogram Feature Analysis | Private | ROC: 0.91 Specificity: 62% Sensitivity: 95%. |

| [91] | MLP, RBFNN | Microcalcification Detection | MIAS | Positive detection rate: 94.7% False positives per image: 0.2% |

| [94] | SVM, ANN | Microcalcification Characterization | MIAS | SVM: Original feature set, Az: 0.81 Enhanced feature set, Az: 0.80 ANN: Original feature set, Az: 0.73 Enhanced feature set, Az: 0.78 |

| [95] | ANN | Detect and Classify Masses | DDSM | AUC = 0.925 |

| [96] | ANN | Detection of Mass and Architectural Distortion | Private | TPF: 0.620 |

| [97] | ANN | Detection of Breast Cancer | Private | AUC = 0.779 ± 0.025 |

| [98] | ANN | Mass Detection | MIAS | Recognition Rate = 97.08% |

Pros and Cons of Machine Learning Approaches

The previous sections encompassed several machine learning methods, such as clustering, ANN and SVM, accomplishing computer vision tasks over mammograms. Here pros and limitations of those techniques are stressed out to enrich the narrative with some considerations and experimental details. Models’ performances are reported in Table 4 according to tasks performed, techniques adopted, and datasets used. For example, the methods of Kamil et al. [101] and Kumar et al. [103] proved the highest accuracy rates, respectively, with 94.12% and 90% over MIAS and DDSM among the clustering-based methods. The ANN-based method proposed by Fogel et al. [90] reached a high sensitivity rate of 95% on a private dataset. At the same time, specificity is lower by 33%, showing a not negligible number of false positives. Conversely, the ANN-based methods by García-Manso et al. [95], and Mahersia et al. [98] achieved, respectively, 0.925 in AUC on DDSM and ranked the highest recognition rate of 97.08% on MIAS. Overall, the best performances over IRMA and DDSM datasets are shown by SVM in the method proposed by Sharma and Khanna [113]. They obtained, respectively, 99% of sensitivity and specificity on IRMA, and 97% sensitivity and 96% specificity on DDSM. Qayyum and Basit [112] reached 96.55% accuracy in both segmentation and classification of suspicious regions over MIAS. Overall, supervised machine learning approaches such as SVM and ANN outrank clustering techniques in the detection of suspicious areas on mammograms, even though the fuzzy c-means–based method by Kumar et al. [103] achieves up to 94.12% accuracy on MIAS.

4.4. Deep Learning Approaches

4.4.1. Supervised Deep Learning

Other than conventional machine learning approaches, newer AI approaches called deep learning (DL) [13] are playing a critical role in the progress of many scientific fields. Unlike the more traditional machine learning techniques, DL architectures are fed with raw data and automatically build those data representations necessary for detection or classification. Deep learning architectures consist of several simple but non-linear modules, which process the representation at different levels, spanning from the raw input to increasingly higher representation layers. Deep learning methods, figuratively speaking, are like complex algebraic circuits whose connections can be fine-tuned. The word deep takes after the many layers characterising architectures. Deep also means that computations across the whole architecture pipeline have many steps. Deep learning is currently the most widely used approach for visual object recognition, machine translation, speech recognition, speech synthesis, and image synthesis. Over the last decades, AI researchers extended pre-existing architectures and proposed some new ones. Fully convolutional networks (FCN), region-based CNN (R-CNN), faster R-CNN, and mask R-CNN, ResNet, inception, VGGNet, feature pyramid networks, cascade R-CNN and libra R-CNN are just some of the most popular architectures adopted for classification and detection tasks. This section discusses deep learning–based approaches for the detection of suspicious regions in mammograms. Table 5 summarises articles based on both supervised and unsupervised deep learning approaches for breast cancer diagnosis.

Fully Convolutional Network (FCN)