SRE-FMaps: A Sinkhorn-Regularized Elastic Functional Map Framework for Non-Isometric 3D Shape Matching

Abstract

1. Introduction

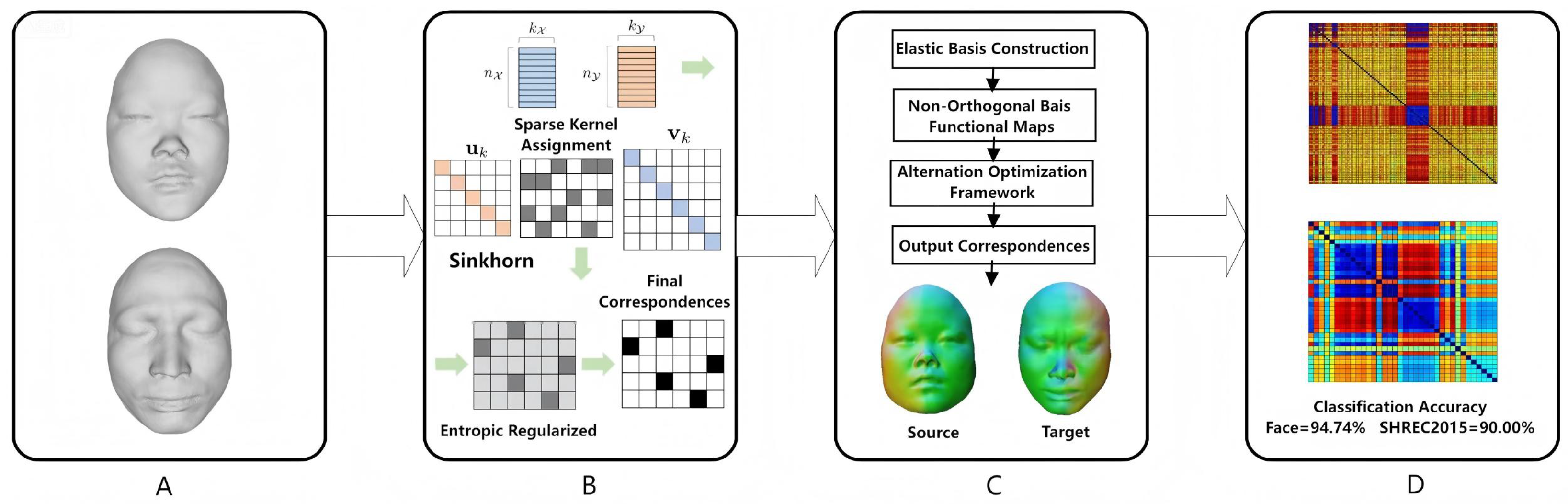

- Elastic deformation-aware spectral representation. We propose SRE-FMaps, a Sinkhorn-Regularized Elastic Functional Map framework that replaces conventional LB eigenbases with thin-shell-derived elastic basis functions, greatly enhancing sensitivity to high-frequency non-isometric deformation.

- Scalable entropy-regularized optimal transport correspondence. We integrate entropy-regularized Sinkhorn transport with sparse kernel acceleration to establish bijective and computationally efficient initialization, achieving linear complexity while maintaining high correspondence accuracy.

- Unified matching and classification via elastic cosine distance. We design a multi-scale cosine-based elastic distance metric that fuses global spectral information with local geometric features, enabling reliable evaluation in both 3D correspondence and classification tasks.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Functional Maps

2.2. Deep Functional Maps

3. Methods

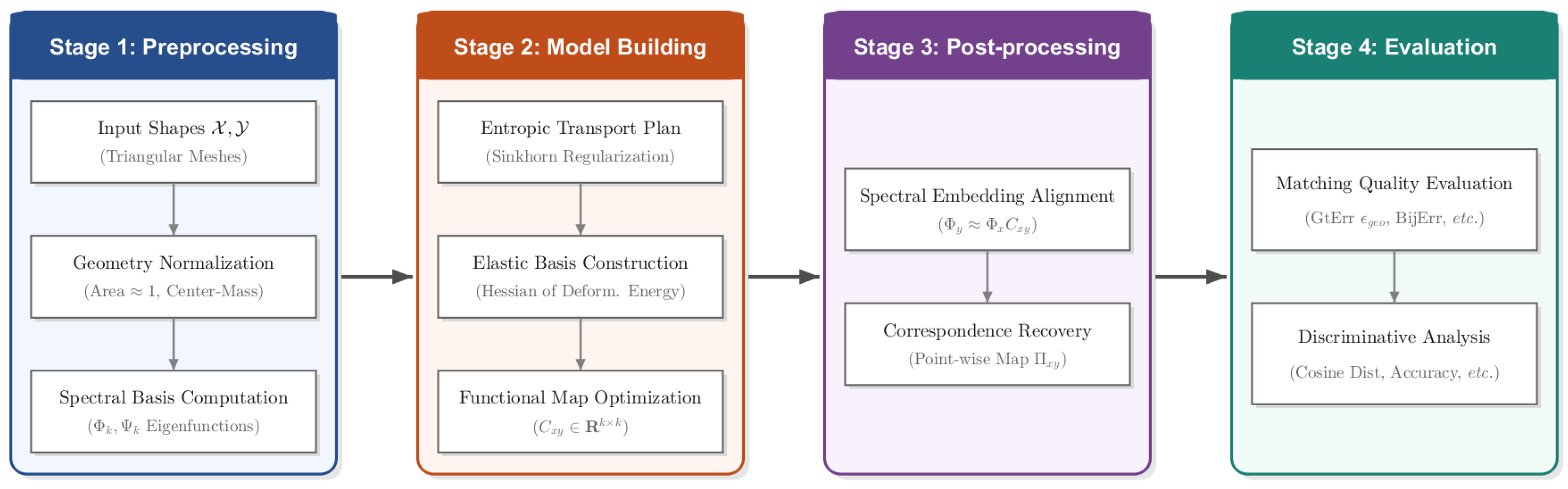

3.1. Overview of the SRE-FMaps Framework

3.2. Initial Map Calculation

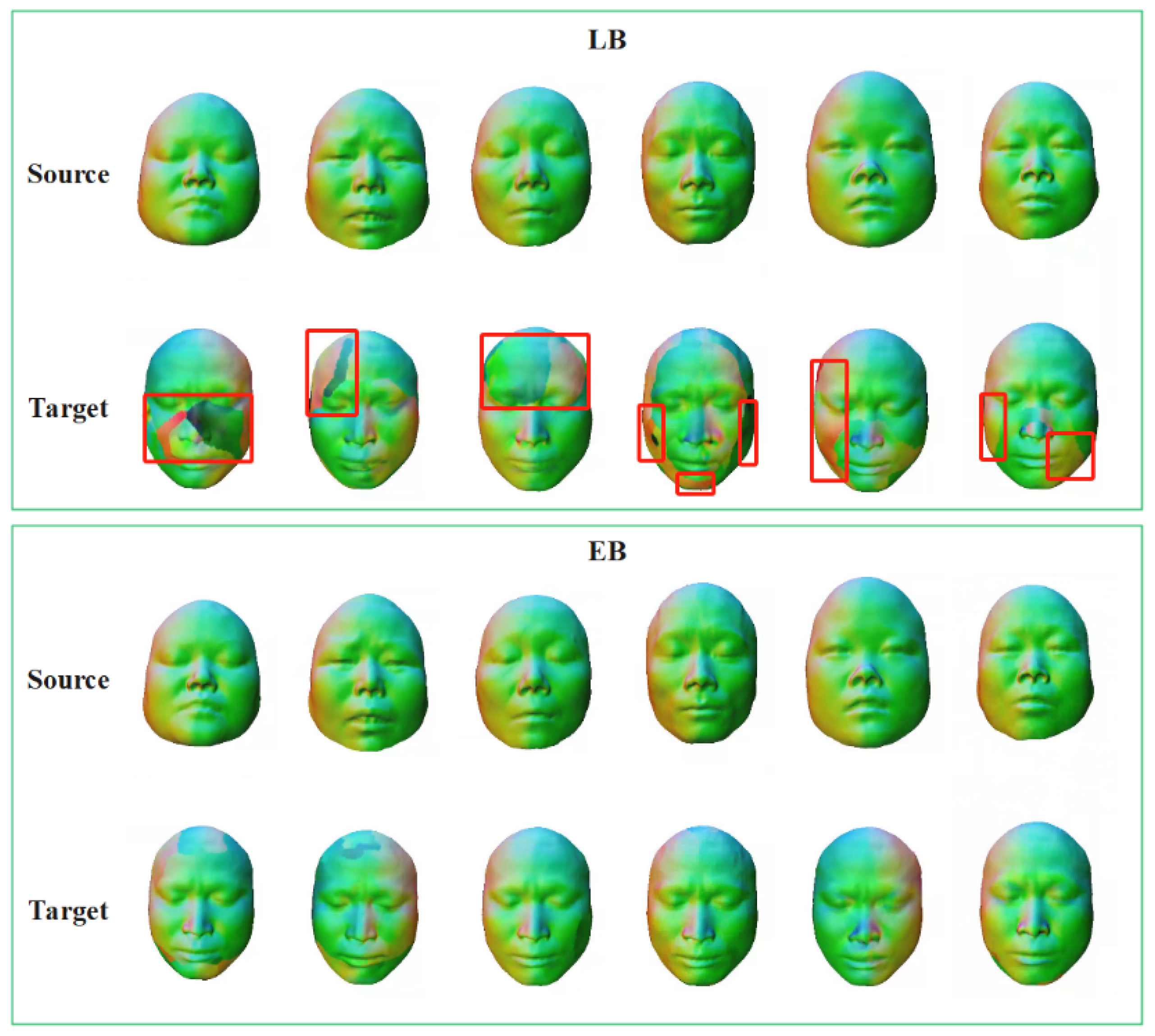

3.3. SRE-FMaps

3.3.1. Functional Maps Under Orthogonal and Non-Orthogonal Bases

3.3.2. Point-to-Point Map Calculation

3.4. Shape Distance Measurement

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Datasets

4.2. Experimental Design

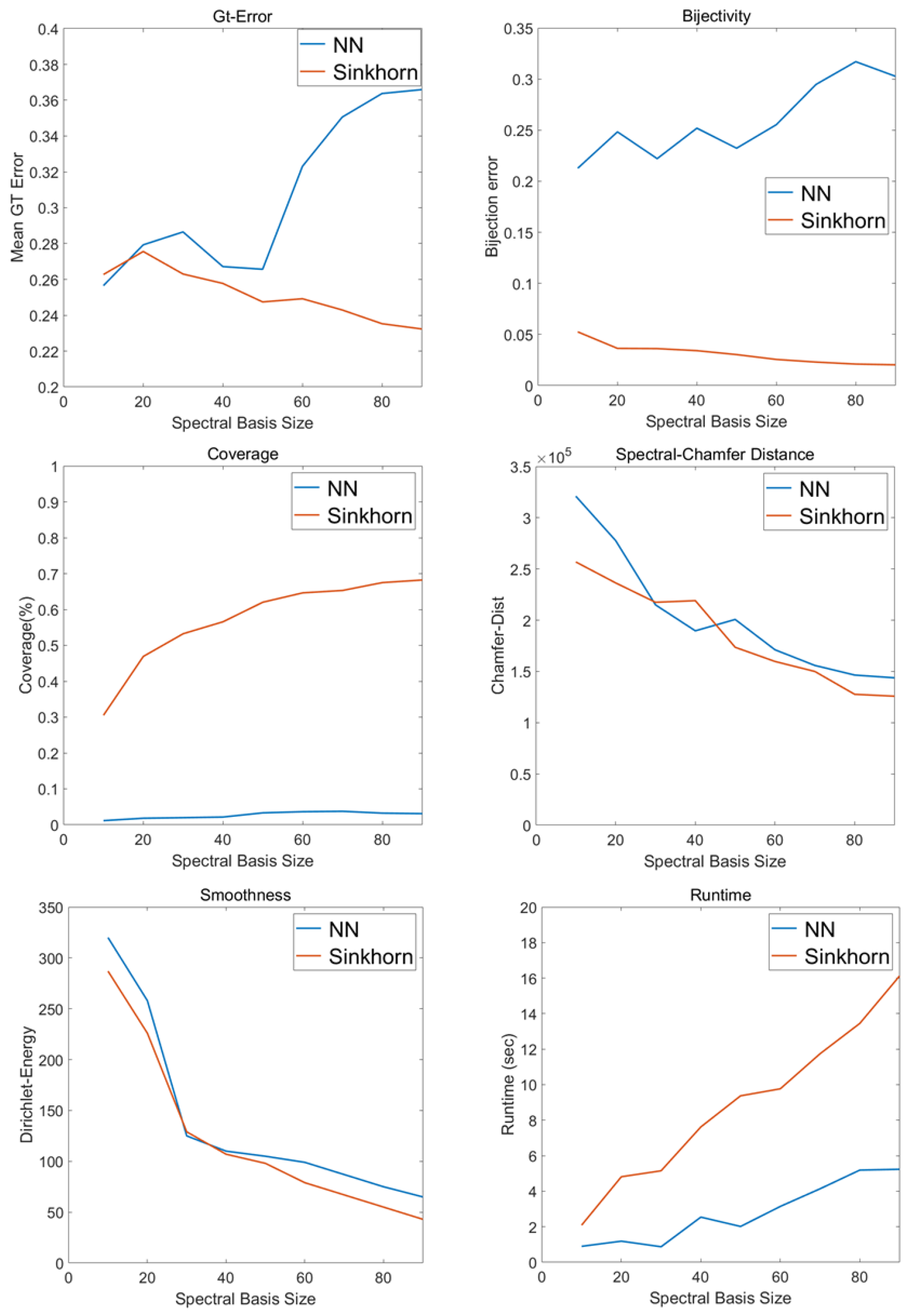

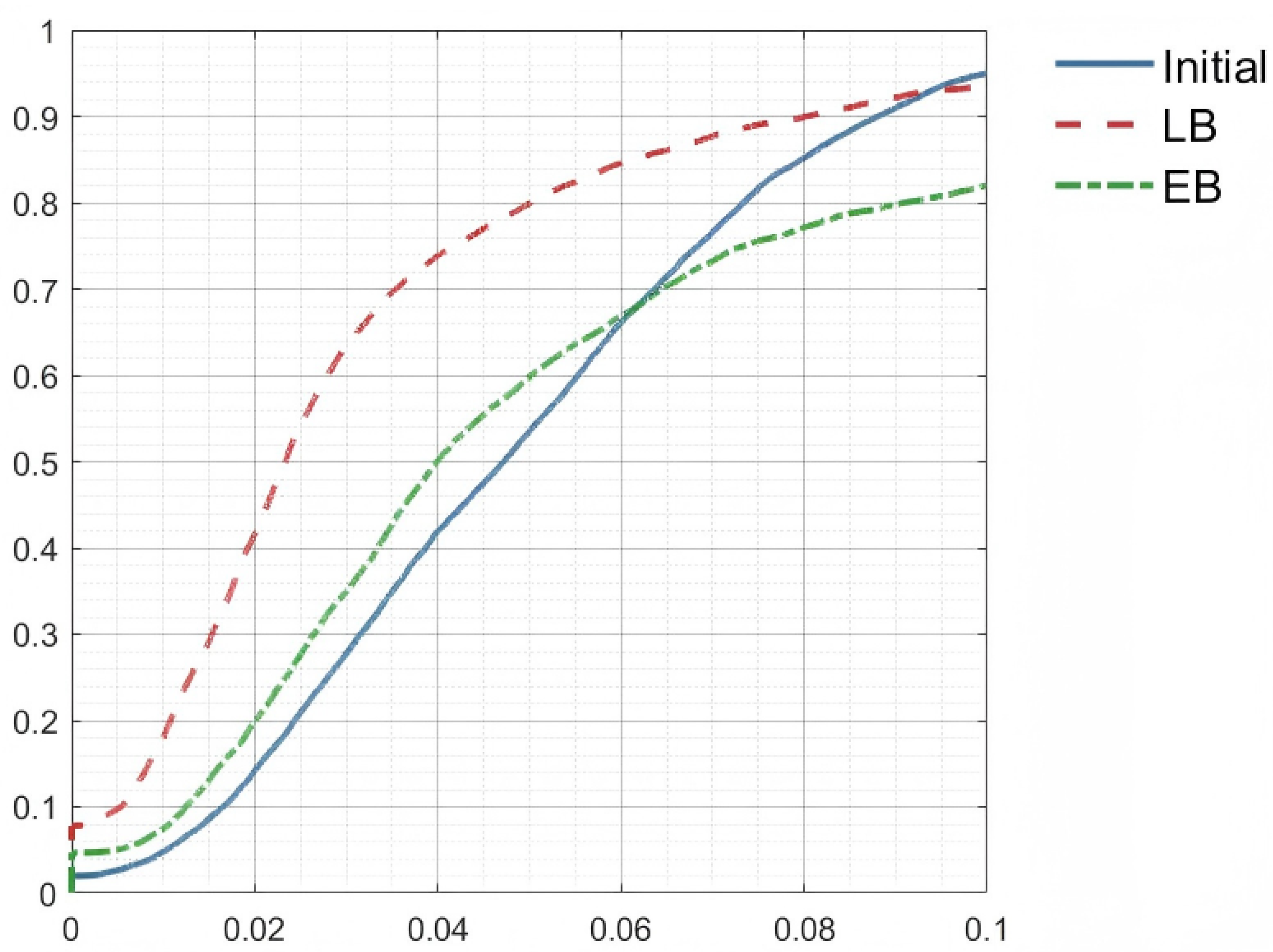

Matching Performance Evaluation

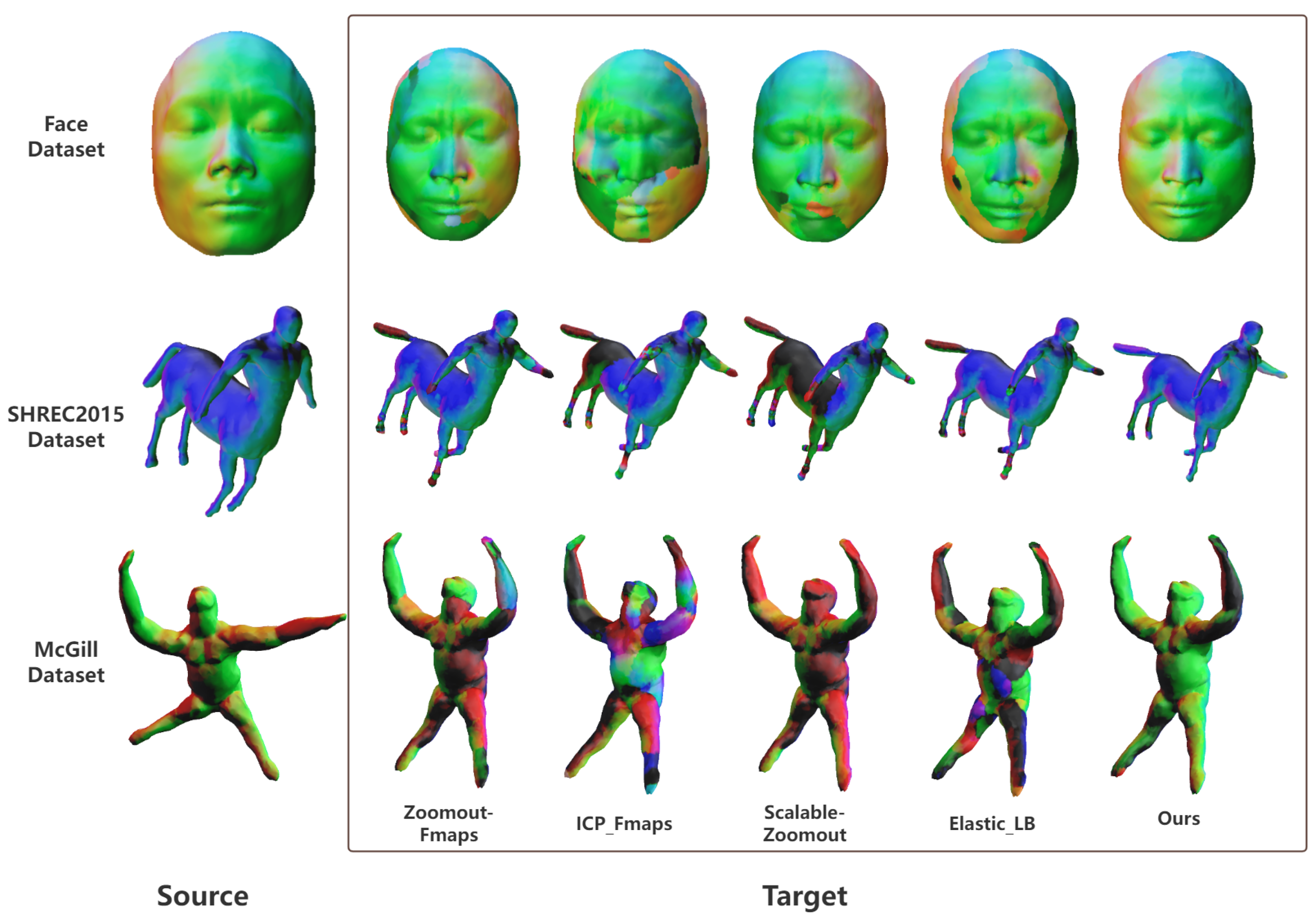

4.3. Comparative Experiment

4.4. Shape Distance Calculation and Classification Results

4.4.1. Shape Distance Calculation

4.4.2. Classification Results

4.5. Discussion and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Derivation of Adjoint Operators

Appendix A.1. Continuous Definitions and Inner Products

Appendix A.2. Discrete Discretization and Mass Matrices

Appendix A.3. Adjoint of the Functional Map Matrix

Appendix A.4. Adjoint of the Point-to-Point Map

Appendix B. Derivation of Spectral–Spatial Consistency

References

- Weinhart, M.; Hocke, A.; Hippenstiel, S.; Kurreck, J.; Hedtrich, S. 3. organ models—Revolution in pharmacological research? Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 139, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Osaimi, F.; Bennamoun, M.; Mian, A. An expression deformation approach to non-rigid 3D face recognition. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2009, 81, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzmann, M.; Pilet, J.; Ilic, S.; Fua, P. Surface deformation models for nonrigid 3D shape recovery. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007, 29, 1481–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovsjanikov, M.; Ben-Chen, M.; Solomon, J.; Butscher, A.; Guibas, L. Functional maps: A flexible representation of maps between shapes. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2012, 31, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustamov, R.M. Laplace-Beltrami eigenfunctions for deformation invariant shape representation. In Symposium on Geometry Processing; Eurographics Association: Goslar, Germany, 2007; Volume 257, pp. 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, F.; Sassen, J.; Azencot, O.; Rumpf, M.; Ben-Chen, M. An elastic basis for spectral shape correspondence. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH 2023 Conference Proceedings, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 6–10 August 2023; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Litany, O.; Remez, T.; Rodola, E.; Bronstein, A.; Bronstein, M. Deep functional maps: Structured prediction for dense shape correspondence. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 5659–5667. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, N.; Attaiki, S.; Crane, K.; Ovsjanikov, M. Diffusionnet: Discretization agnostic learning on surfaces. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2022, 41, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetverikov, D.; Svirko, D.; Stepanov, D.; Krsek, P. The trimmed iterative closest point algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2002 International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 11–15 August 2002; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 3, pp. 545–548. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, G.; Ren, J.; Melzi, S.; Wonka, P.; Ovsjanikov, M. Fast sinkhorn filters: Using matrix scaling for non-rigid shape correspondence with functional maps. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 384–393. [Google Scholar]

- Corman, E.; Ovsjanikov, M.; Chambolle, A. Continuous matching via vector field flow. In Computer Graphics Forum; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 34, pp. 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Nogneng, D.; Ovsjanikov, M. Informative descriptor preservation via commutativity for shape matching. In Computer Graphics Forum; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; Volume 36, pp. 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.; Ovsjanikov, M. Adjoint map representation for shape analysis and matching. In Computer Graphics Forum; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; Volume 36, pp. 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Poulenard, A.; Skraba, P.; Ovsjanikov, M. Topological function optimization for continuous shape matching. In Computer Graphics Forum; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; Volume 37, pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Melzi, S.; Ren, J.; Rodola, E.; Sharma, A.; Wonka, P.; Ovsjanikov, M. Zoomout: Spectral upsampling for efficient shape correspondence. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.07865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Li, Q.; Liu, S.; Liu, X. Efficient deformable shape correspondence via multiscale spectral manifold wavelets preservation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 14536–14545. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, D.K.; Vandergheynst, P.; Gribonval, R. Wavelets on graphs via spectral graph theory. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 2011, 30, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnet, R.; Ovsjanikov, M. Scalable and efficient functional map computations on dense meshes. In Computer Graphics Forum; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; Volume 42, pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, M.; Toker, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Cremers, D. Deep shells: Unsupervised shape correspondence with optimal transport. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 10491–10502. [Google Scholar]

- Bruna, J.; Zaremba, W.; Szlam, A.; LeCun, Y. Spectral networks and locally connected networks on graphs. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6203. [Google Scholar]

- Donati, N.; Corman, E.; Ovsjanikov, M. Deep orientation-aware functional maps: Tackling symmetry issues in shape matching. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 742–751. [Google Scholar]

- Donati, N.; Corman, E.; Melzi, S.; Ovsjanikov, M. Complex functional maps: A conformal link between tangent bundles. In Computer Graphics Forum; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; Volume 41, pp. 317–334. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Li, Q.; Liu, S.; Yan, D.M.; Xu, H.; Liu, X. RFMNet: Robust deep functional maps for unsupervised non-rigid shape correspondence. Graph. Model. 2023, 129, 101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnet, R.; Ovsjanikov, M. Memory-scalable and simplified functional map learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 4041–4050. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, D.; Lähner, Z.; Bernard, F. Synchronous diffusion for unsupervised smooth non-rigid 3D shape matching. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 262–281. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, F.; Li, Q.; Hu, L.; Wang, H.; Xu, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, H. Deep Frequency Awareness Functional Maps for Robust Shape Matching. In IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Volume 31, pp. 7781–7794. [Google Scholar]

- Salton, G.; Wong, A.; Yang, C.S. A vector space model for automatic indexing. Commun. ACM 1975, 18, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickup, D.; Sun, X.; Rosin, P.L.; Martin, R.R.; Cheng, Z.; Nie, S.; Jin, L. SHREC’15 track: Canonical forms for non-rigid 3D shape retrieval. In Proceedings of the 8th Eurographics Workshop on 3D Object Retrieval, Zurich, Switzerland, 2–3 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi, K.; Zhang, J.; Macrini, D.; Shokoufandeh, A.; Bouix, S.; Dickinson, S. Retrieving articulated 3-D models using medial surfaces. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2008, 19, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, D.M. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Method Combinations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combination | NN + LB | NN + EB | Sink + LB | Sink + EB | |

| Face | Same Kinds | ||||

| C1-C1 | 0.7855 | 0.5009 | 0.4287 | 0.1102 | |

| C1-C1 | 0.7968 | 0.6804 | 0.5235 | 0.3222 | |

| C1-C1 | 0.8737 | 0.7487 | 0.6090 | 0.1385 | |

| C2-C2 | 0.7966 | 0.5881 | 0.5354 | 0.1511 | |

| C2-C2 | 0.8282 | 0.6203 | 0.5912 | 0.3108 | |

| C2-C2 | 0.8141 | 0.6958 | 0.4683 | 0.2625 | |

| Different Kinds | |||||

| C1-C2 | 1.0900 | 1.2306 | 1.2268 | 1.3661 | |

| C1-C2 | 1.1048 | 1.3157 | 1.0267 | 1.2904 | |

| C1-C2 | 1.0034 | 1.1074 | 0.9630 | 1.0196 | |

| SHREC2015 | Same Kinds | ||||

| C1-C1 | 0.8801 | 0.5398 | 0.6698 | 0.5139 | |

| C2-C2 | 0.3557 | 0.4360 | 0.3239 | 0.2192 | |

| C3-C3 | 0.3051 | 0.2918 | 0.3433 | 0.1009 | |

| C4-C4 | 0.6438 | 0.5015 | 0.4841 | 0.1755 | |

| C5-C5 | 0.6985 | 0.3761 | 0.4750 | 0.2750 | |

| C6-C6 | 0.3099 | 0.3030 | 0.8203 | 0.6367 | |

| Different Kinds | |||||

| C1-C2 | 1.0295 | 1.1799 | 1.6532 | 1.7381 | |

| C1-C3 | 1.3148 | 1.4316 | 1.6126 | 1.7893 | |

| C1-C4 | 0.7150 | 0.9408 | 1.5563 | 1.5693 | |

| C1-C5 | 1.3621 | 1.3885 | 1.3693 | 1.6932 | |

| C1-C6 | 1.1759 | 1.7381 | 1.3306 | 1.3701 | |

| Evaluation Indicators | Calculation Formula | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Accuracy is the most intuitive global performance indicator, measuring the proportion of correct predictions made by the model as a whole. | |

| Precision | Precision is the proportion of samples predicted to be positive that are actually positive, reflecting the reliability of the model’s prediction results. | |

| Recall | The recall rate is the proportion of positive samples that are correctly identified, reflecting the ability of the model to find positive samples. | |

| Specificity | The specificity is the proportion of correctly identified samples in the negative class, which reflects the ability of the model to identify negative samples and is only used in binary classification. | |

| F1-Score | The F1-score is the harmonic average of precision and recall, which comprehensively evaluates the accuracy and coverage of the model. |

| Metric | Methods | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NN + LB | NN + EB | Sinkhorn + LB | Sinkhorn + EB | |

| Accuracy (%) | 42.11 | 63.16 | 73.68 | 94.74 |

| Precision (%) | 57.14 | 63.64 | 77.78 | 100.00 |

| Recall (%) | 33.33 | 70.00 | 70.00 | 88.89 |

| Specificity (%) | 57.14 | 55.56 | 77.78 | 100.00 |

| F1-Score | 0.42 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.94 |

| Metric | Methods | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NN + LB | NN + EB | Sinkhorn + LB | Sinkhorn + EB | |

| Accuracy (%) | 40.00 | 60.00 | 70.00 | 90.00 |

| Precision (%) | 33.33 | 52.78 | 66.67 | 91.67 |

| Recall (%) | 33.33 | 58.33 | 61.11 | 91.67 |

| F1-Score | 0.31 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhao, D. SRE-FMaps: A Sinkhorn-Regularized Elastic Functional Map Framework for Non-Isometric 3D Shape Matching. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11120452

Zhang D, Zhang Y, Wang N, Zhao D. SRE-FMaps: A Sinkhorn-Regularized Elastic Functional Map Framework for Non-Isometric 3D Shape Matching. Journal of Imaging. 2025; 11(12):452. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11120452

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Dan, Yue Zhang, Ning Wang, and Dong Zhao. 2025. "SRE-FMaps: A Sinkhorn-Regularized Elastic Functional Map Framework for Non-Isometric 3D Shape Matching" Journal of Imaging 11, no. 12: 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11120452

APA StyleZhang, D., Zhang, Y., Wang, N., & Zhao, D. (2025). SRE-FMaps: A Sinkhorn-Regularized Elastic Functional Map Framework for Non-Isometric 3D Shape Matching. Journal of Imaging, 11(12), 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11120452