Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the technical and environmental feasibility of producing concrete paver blocks and pervious concrete paver blocks by incorporating marble waste to evaluate its filler effect within the cementitious matrix. The methodology included the characterization of marble waste, the production of test specimens with the control (0%), 10%, 20%, and 30% of cement replacement, and the execution of performance tests, supplemented by statistical analyses. The results indicated that marble waste replacement significantly impacted the properties. In terms of pervious concrete paver block permeability, the highest rates were observed in the control and 30% treatments. For water absorption, concrete paver blocks showed higher values at a maximum of 20%, while pervious concrete paver blocks maintained statistically analogous values for 10% and 20%. Regarding compressive strength, the concrete paver block formulation with 10% marble waste was statistically compatible with the control. It is concluded that the incorporation of marble waste into concrete and pervious concrete paver blocks is environmentally advantageous as it valorizes an industrial waste. However, mix design optimization is essential, given that excessive replacement (above 10%) resulted in a reduction in compressive strength.

1. Introduction

The expansion of impervious surfaces within urban areas has contributed to the increase in urban flooding and contamination associated with surface runoff, exposing the limitations of conventional drainage systems [1]. At the same time, cement production accounts for approximately 8% of global CO2 emissions, reinforcing the need for more sustainable construction practices [2]. These combined challenges underscore the importance of developing permeable and low-impact concrete solutions capable of enhancing surface infiltration and supporting the restoration of the natural hydrological cycle [3].

The use of concrete paver blocks (CBs) is an environmentally advantageous alternative that supports sustainable construction [4]. These systems are recognized for their low maintenance costs, ease of installation, and ability to reduce soil impermeabilization [5]. In addition to improving surface permeability, CBs allow the incorporation of waste materials into their composition, adding value to residues [6]. Another type of pavement widely used in sustainable urban drainage is pervious concrete paver blocks (PCBs), which are characterized by their high porosity and are applied in stormwater management [7]. PCB reduces surface runoff and enhances water infiltration, contributing to flood control and groundwater recharge [1,8]. Furthermore, studies indicate that PCB can improve water quality by acting as a passive barrier that immobilizes inorganic pollutants and organic contaminants, as micropollutants tend to accumulate on its surface [9]. Thus, pavers blocks can provide significant environmental benefits by integrating sustainable stormwater management strategies [10].

Parallel to the growing soil imperviousness, the increase in construction activities has substantially elevated waste generation, notably construction and demolition waste (CDW) [11,12]. Furthermore, the construction industry is a major consumer of natural resources, accounting for approximately 40% of aggregates (stone, gravel, and sand) and 25% of wood consumed annually [2]. The magnitude of waste volume is particularly notable in the ornamental stone industry, where residues represent an estimated 25% to 30% of the total production, following the sawing process [13].

Despite recent advances in waste management, the large volumes of CDW continue to pose environmental challenges. According to Sakthibala et al. [14] and Bonifazi et al. [15], CDW represents a substantial fraction of municipal solid waste streams, accounting for approximately 20–50% of the total waste generated in many regions, thereby making the construction industry responsible for nearly one-third of all waste destined for landfills in some countries [2]. Nevertheless, these authors also report that recycled CDW has been investigated and applied in construction-related uses, particularly as aggregates in concrete and in road base and sub-base layers.

In this context, residues from the ornamental stone industry, particularly marble and granite dust, deserve special attention, as their improper disposal has been associated with surface water contamination, air pollution through fine particulate dispersion, and adverse effects on human health due to inhalation [16]. These impacts tend to be exacerbated in developing countries, where less effective waste management systems and limited segregation and recovery practices intensify soil and groundwater contamination risks through leachate generation. Consequently, CDW-related environmental impacts remain a relevant concern, reinforcing the importance of waste valorization strategies aimed at reducing improper disposal and mitigating ecological burdens [14,15].

The valorization of industrial waste in construction (including marble powder, or MW, and plastic residues) is an effective approach that contributes to environmental impact reduction, energy conservation, and compliance with the Sustainable Development Goal of responsible consumption and production (SDG 12). The expressive quantity of waste generated by the ornamental stone industry has motivated researchers to investigate potential applications for these residues in various products [17], such as concrete by replacing cement or aggregates [18], mortar [19], and ceramic products like tiles and bricks [20]. The use of residual materials, such as MW, in pavement units emerged as a solution to the high production cost of blocks, also leading to improvements in their durability and resistance.

The main objective of this study was to investigate the technical feasibility of incorporating MW into CB and PCB. Specifically, the research aimed to evaluate how the specific lamellar and blocky geometry of MW facilitates the packing density of the cementitious matrix. This physical mechanism is hypothesized to act as a micro-filler, potentially reducing capillary porosity and enhancing stress distribution pathways. By employing statistical tools, this work identifies the optimal substitution level to balance structural performance with satisfactory permeability, thereby reducing cement consumption and mitigating the environmental impacts of CDW and GHG emissions from cement production.

2. Results

2.1. Performance Tests

2.1.1. Compressive Strength

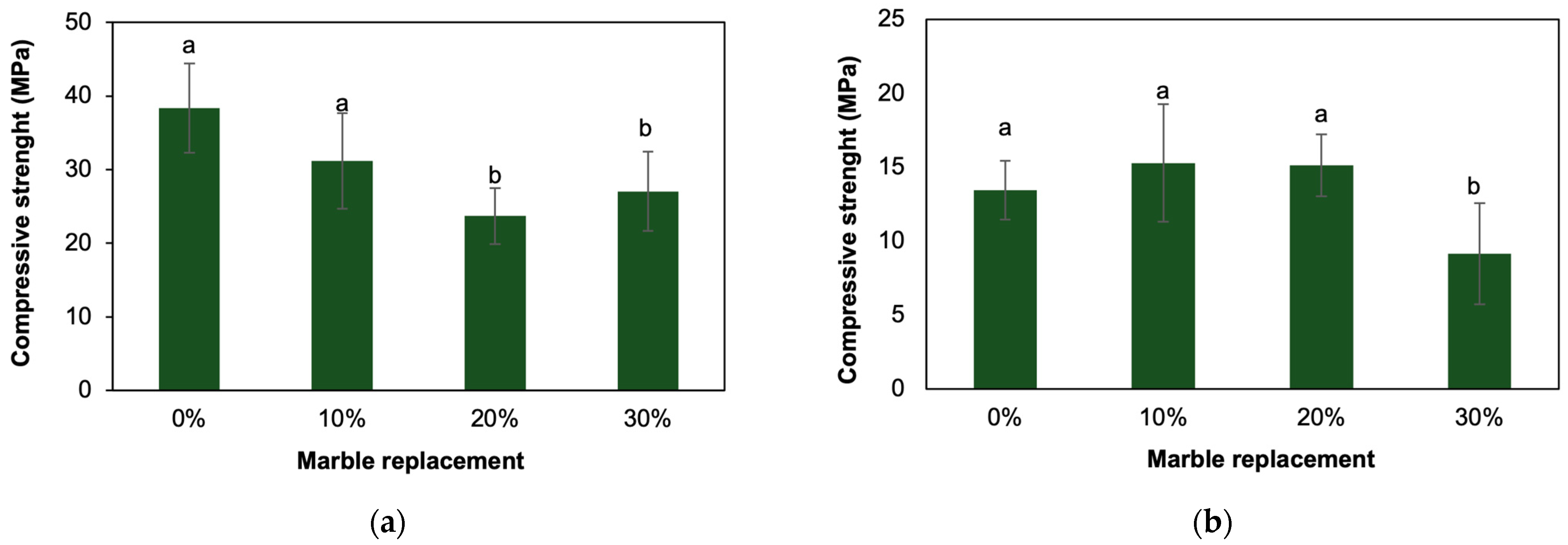

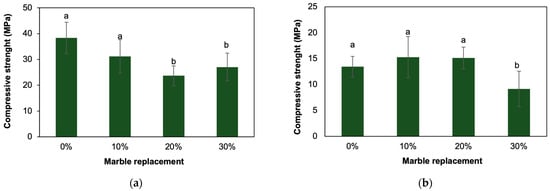

Figure 1 presents the compressive strength results for the CBs and PCBs at 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% replacement with MW. The statistical analysis (ANOVA followed by the Tukey post hoc test) indicated the existence of significant differences between the treatments (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the compressive strength of (a) concrete paver blocks (CBs) and (b) pervious concrete paver blocks (PCBs). Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s post hoc test.

The highest mean strength in CBs was observed in the control sample (0%) with 38 ± 6 MPa, belonging to statistical group ‘a’. The 10% replacement (31 ± 6 MPa) was statistically compatible with the control (group ‘a’). Conversely, treatments with higher MW content (20% and 30%) showed a significant reduction, being grouped together in statistical group ‘b’ (24 ± 4 and 27 ± 5.39 MPa, respectively), indicating that replacement levels above 10% significantly compromise mechanical strength.

In the case of PCB samples, the Tukey post hoc test confirmed that only the 30% replacement level exhibited significantly lower mean strength (9 ± 3 MPa) than other treatments. The highest strength was observed at the 10% replacement level (15.28 ± 3.98 MPa) and 20% replacement level (15.11 ± 2.10 MPa). These two treatments, along with the control (0% replacement, 13.45 ± 2.00 MPa), were found to be statistically similar, as indicated by overlapping standard deviation intervals and the Tukey test results.

The significant reduction in compressive strength at the 30% MW replacement level can be attributed to the binder dilution effect. While lower contents (up to 10%) promote microstructural refinement via the micro-filler effect, the excessive addition of MW, which acts as a chemically inert material, critically reduces the volume of reactive clinker per unit of volume. Consequently, there is a lower formation of C-S-H gel, the main phase responsible for mechanical strength [21,22,23,24]. In cementitious composites, the microstructural characteristics of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), particularly porosity and hydration product distribution, play a key role in mechanical performance and crack propagation under stress [25]. In this context, excessive amounts of fine MW particles may induce particle agglomeration, increasing localized porosity and weakening the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), which facilitates crack propagation under stress.

Regarding the variability observed in the 30% MW group, high standard deviation is associated with the inherent heterogeneity of pervious concrete and the manual molding process. However, the downward trend in mechanical performance remains statistically significant and consistent with the literature on high-volume mineral additions, where the inert nature of the filler at high concentrations creates stress concentration points that compromise the material’s stability [21].

2.1.2. Water Absorption

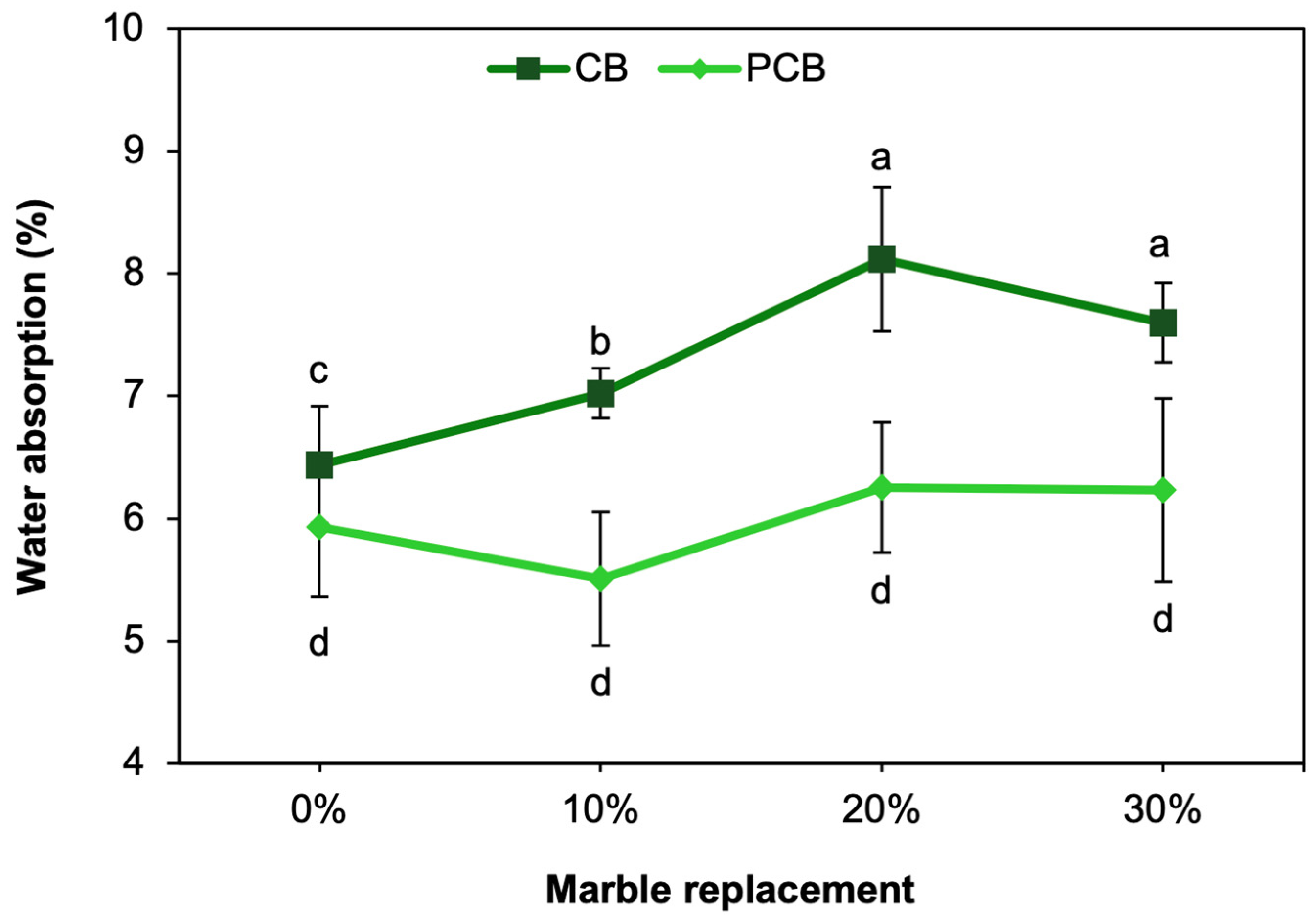

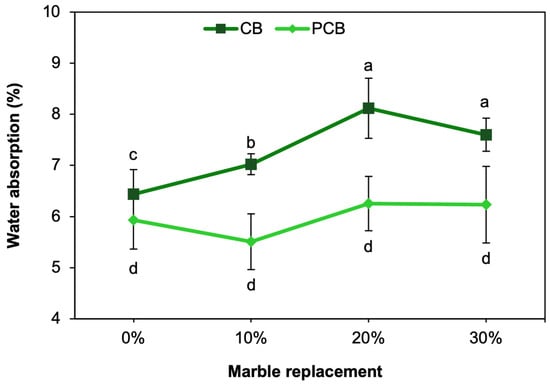

Figure 2 illustrates the comparative results of the water absorption test for the CBs and the PCBs.

Figure 2.

Results of water absorption tests of concrete paver blocks (CBs) and pervious concrete paver block (PCB) samples. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s post hoc test.

The ANOVA followed by the Tukey post hoc test of the CB samples indicated that replacement with MW significantly increased water absorption compared to the control. The highest absorption for CBs was recorded at the 20% replacement level (8.11 ± 0.59%), which exceeds the maximum 7% limit established by the Brazilian standard for concrete paving units [26].

For the PCBs, the ANOVA indicated that the mean absorption values were statistically analogous (or similar) across all treatments (p > 0.05). The best performance (lowest water absorption) was achieved by the 10% replacement level (5.51 ± 0.55%), followed by the control sample (5.93 ± 0.56%), demonstrating that MW can be incorporated into PCBs without compromising absorption uniformity. These trends confirm that the hydration properties of the cement and the final mix design influence water absorption.

2.1.3. Permeability

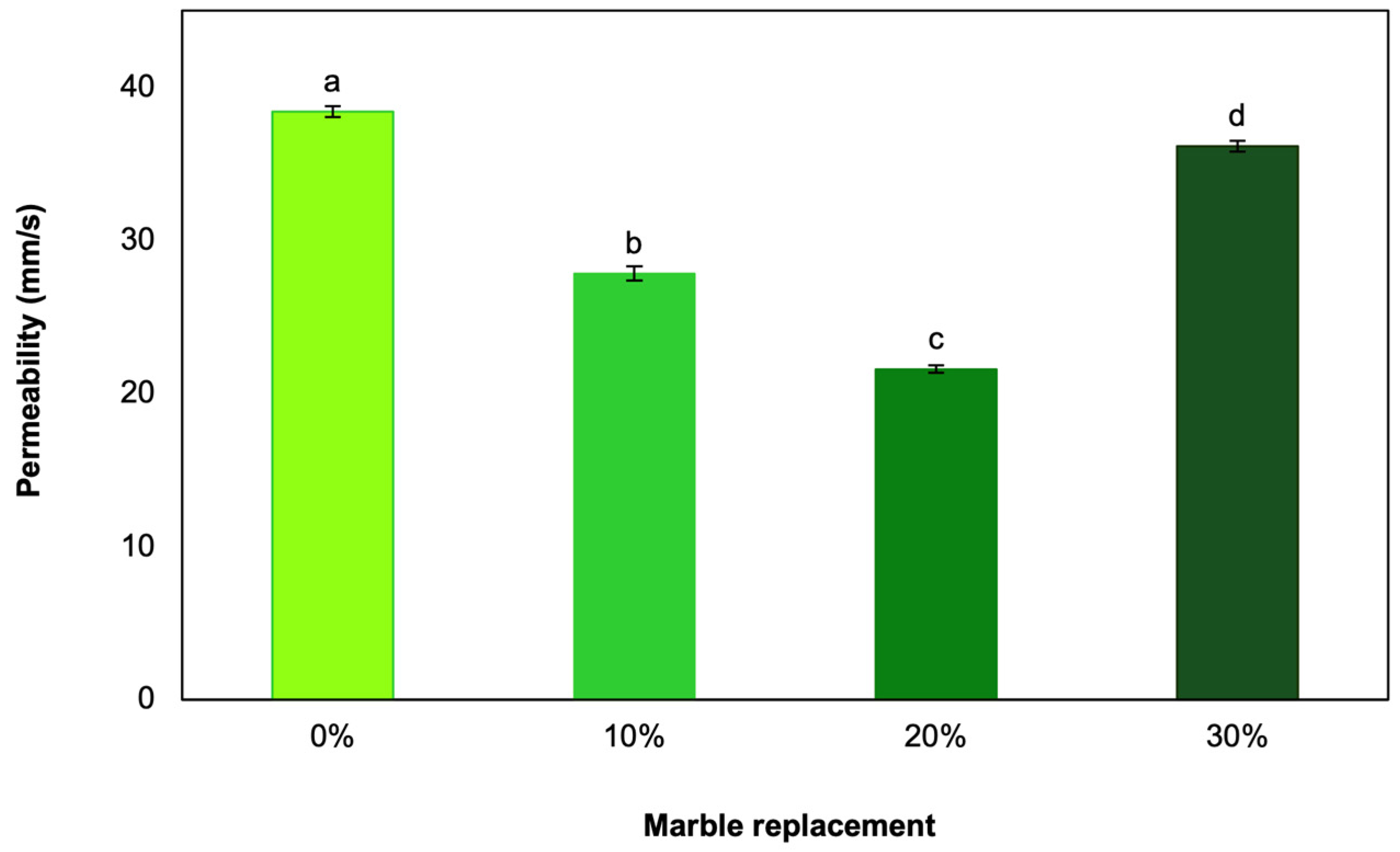

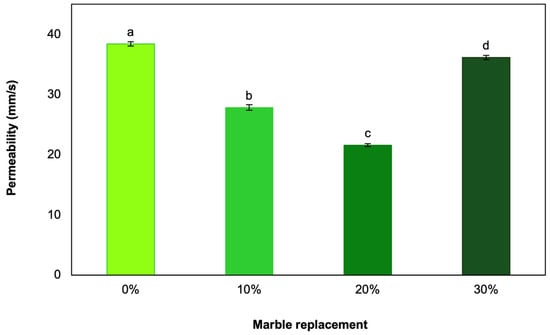

The result of the permeability test for the PCBs is presented in Figure 3. Statistical analysis revealed that all comparisons between the treatments were statistically significantly different (p 0) for all adjusted p-values.

Figure 3.

Permeability test results of pervious concrete paver blocks. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s post hoc test.

The highest permeability was observed in the control sample (0%), with a mean of 38.4 ± 0.36 mm/s (group ‘a’), followed closely by the 30% replacement level (36.15 ± 0.37 m/s, group ‘d’). In contrast, the lowest permeability was exhibited by the 20% replacement sample (group ‘c’). All analyzed samples demonstrated permeability values greater than required by the Brazilian standard [27], thus confirming their classification as pervious units.

2.2. Chemical and Morphological Characterization

2.2.1. SEM Analysis

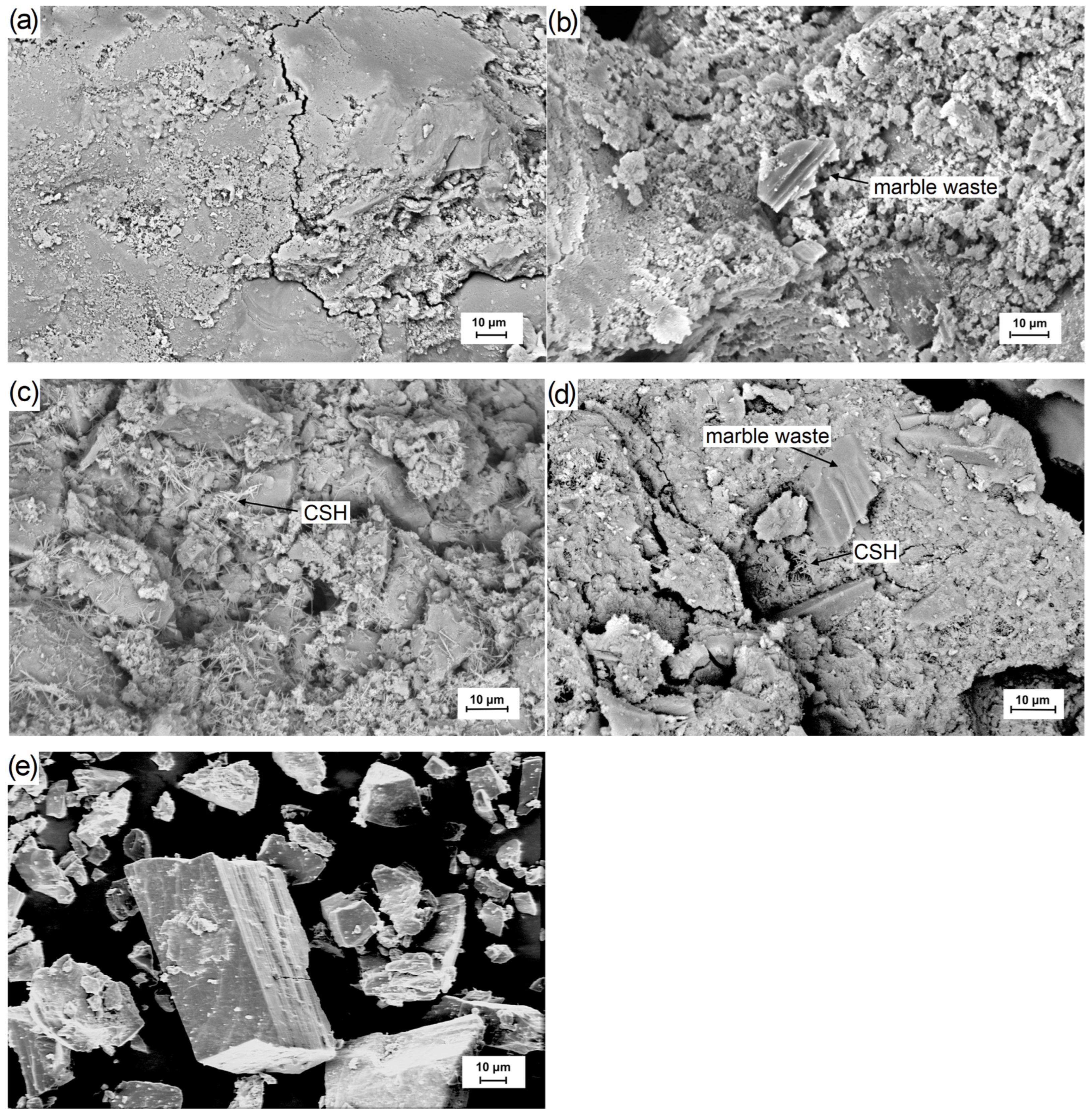

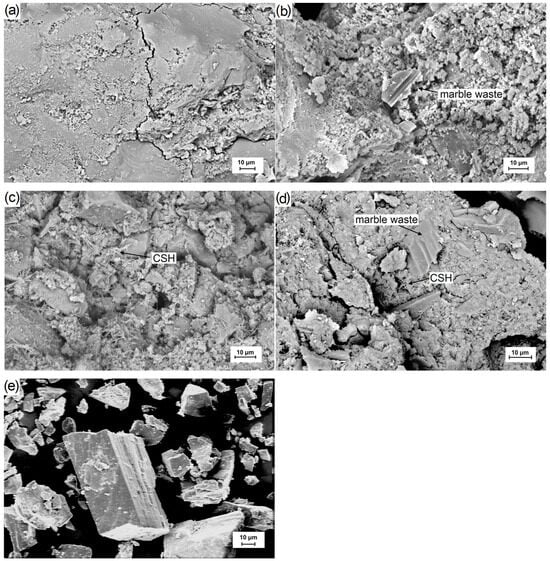

The morphological characteristics of MW and the microstructure of the concrete blocks were investigated using SEM, and the results are presented in Figure 4. The MW, shown in Figure 4e, is composed of fine-sized particles with a particular geometry that includes laminar shapes and crystalline blocks. This distinct geometry is important for its role in the cementitious matrix.

Figure 4.

Scanning electron microscopy images of (a) concrete paver blocks (CBs), (b) CB with 10% cement replacement using marble waste (MW), (c) pervious concrete paver blocks (PCBs), (d) PCB with 10% cement replacement using MW, and (e) MW.

The incorporation of 10% MW modified the microstructure of both CB and PCB samples. A comparison between the control sample (Figure 4a) and the CB sample with 10% MW (Figure 4b) reveals MW particle within the cementitious matrix. These particles, characterized by a distinct lamellar and blocky geometry, are thoroughly enveloped by hydration products, exhibiting high chemical–mechanical integration. Similarly, Figure 4d (PCB with 10% MW) illustrates the intercalation of these fine particles among the C-S-H formations, confirming that the MW geometry facilitates the filling of capillary pores [28,29].

This micro-filler effect enhances the global packing density of the matrix and reinforces the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the paste and the aggregates. Rather than attributing strength gains solely to particle geometry, these results suggest a synergistic mechanism where the MW particles reduce local porosity and provide a more continuous path for stress distribution within the composite. This visual and structural contrast provides the morphological basis for understanding how moderate MW replacement levels maintain structural integrity despite the partial reduction in clinker content [24,30].

The observed morphology suggests that the MW lamellar/blocky geometry particles promote a more efficient mechanical interlocking and improve overall particle packing. Consequently, this geometry facilitates the reduction in capillary voids, creating a more continuous and denser matrix that is more effective at transferring loads during compression. Thus, the maintained structural performance is not a direct result of the geometry itself, but a consequence of the microstructural refinement and improved ITZ integrity that this geometry enables [31,32].

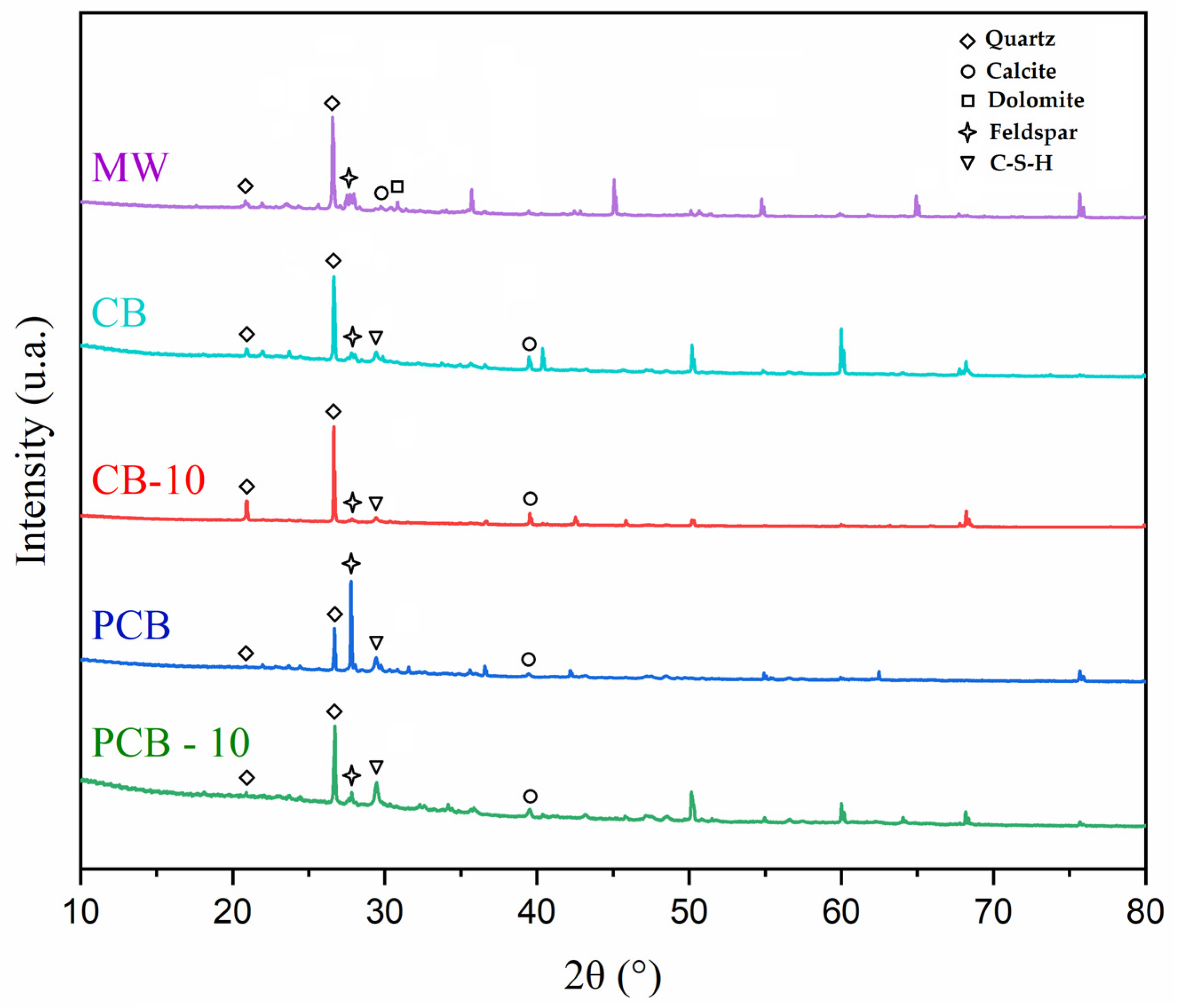

2.2.2. XRD Analysis

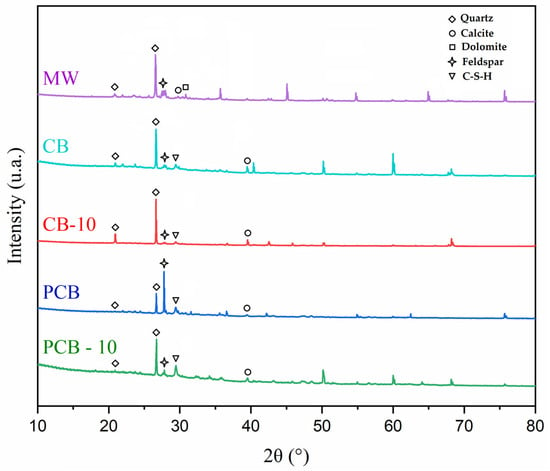

Figure 5 displays the XRD diffractograms of the MW and of PCB and CB, as well as of PCB-10 and CB-10 samples. The analysis revealed several characteristic mineralogical phases in all samples, providing insight into the material’s composition and the incorporation of the MW.

Figure 5.

X-ray diffraction of marble waste (MW), pervious concrete paver blocks (PCBs), concrete blocks (CBs), and samples with 10% cement replacement using MW (PCB-10 and CB-10).

The XRD pattern of the MW reveals that quartz (SiO2) is the dominant crystalline phase, as indicated by the most intense diffraction peak at 26.6° (RRUFFID R040031) [4]. In addition, carbonate phases, characteristic of marble rocks, are also identified in the diffractogram. The reflections of calcite (CaCO3) appear at around 29.4° and 39.5° (RRUFFID R050009), while the presence of dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) is identified by the peak at approximately 30.9°(RRUFFID R050370).

For all processed materials, including the CB and PCB with 0% and 10% of MW, the SiO2 peak at 26.6° remains evident in the XRD patterns. This reflection is associated with both the intrinsic presence of quartz in the natural aggregates and in the mixtures containing MW, with the contribution of the quartz-rich fraction identified in the marble powder itself.

Furthermore, a diffraction peak observed at around 27.8° can be attributed to feldspar phases (RRUFFID R040055) originating from the coarse aggregate. This peak is noticeably more intense in the PCB samples, which is consistent with their higher proportion of coarse aggregate in comparison with the conventional mixtures.

Finally, all cementitious samples exhibit a broader peak located near 29°, which is likely to be associated with the presence of calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H). This broad reflection partially overlaps with the sharper peak of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), indicating the superposition of the main hydration product of Portland cement with carbonate phases in this angular region.

The XRD patterns (Figure 5) confirm the chemical integrity of the cementitious matrix following the incorporation of MW. The persistence of characteristic Ca(OH)2 peaks and the amorphous halo associated with the C-S-H gel indicate that the partial replacement of cement did not inhibit the essential hydration reactions for strength development. The prominent CaCO3 peaks, originating from the marble waste, corroborate the SEM analysis, suggesting that these crystalline particles act synergistically with the hydration products. While C-S-H provides chemical cohesion, the MW particles exert a micro-filler effect, occupying intergranular voids and reinforcing the ITZ. This cooperation between the crystalline phases of the waste and the amorphous hydration products explains the maintenance of macroscopic mechanical performance, demonstrating that MW acts as a physical reinforcement that compensates for the reduced clinker volume in the mixture [21,23].

The synergy between the crystalline CaCO3 pikes and the C-S-H gel indicates that while the cement provides chemical bonding, the MW geometry supports the physical skeleton of the matrix. By acting as a stable micro-filler, the MW particles mitigate the presence of weak points in the microstructure, facilitating a more uniform stress distribution across the substituted matrix.

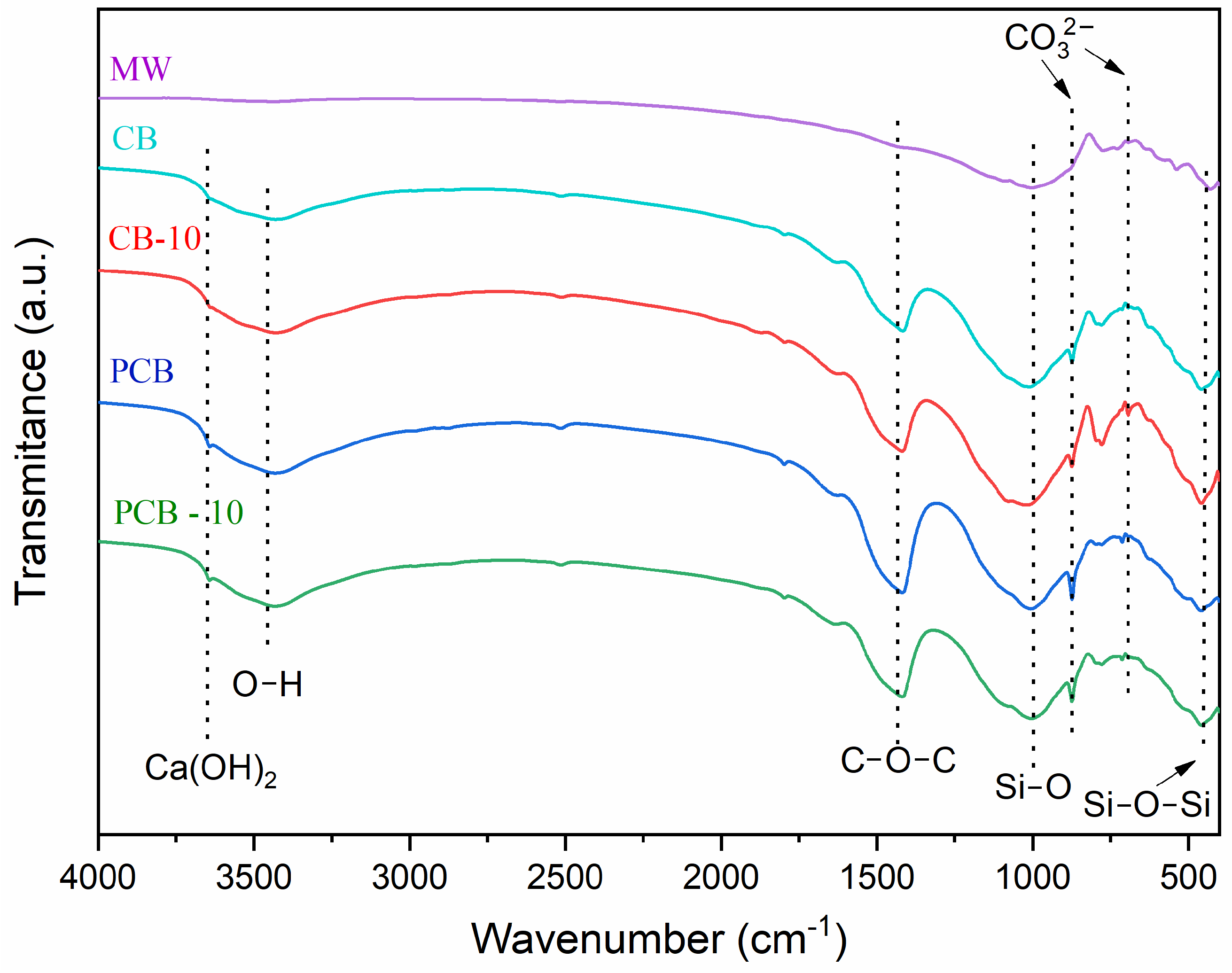

2.2.3. FTIR Analysis

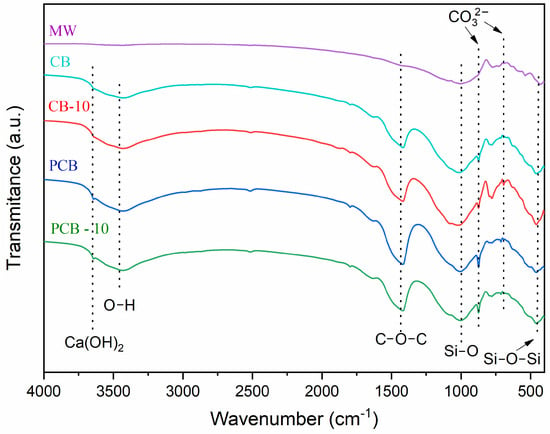

The FTIR spectra obtained (Figure 6) enabled the identification of functional groups associated with the chemical composition of MW and with the hydration products of Portland cement paste, particularly C-S-H. In the low wavenumber region, characteristic vibrational modes observed around 450 cm−1 are attributed to Si–O–Si bending vibrations [33,34].

Figure 6.

FTIR analysis of marble waste (MW), concrete paver blocks (CBs), pervious concrete paver blocks (PCBs), and samples with 10% cement replacement using MW (CB-10 and PCB-10).

The presence of carbonate groups, presented in both MW and the cement matrix [35], was confirmed in the low wavenumber region through the carbonate bending vibration (CO32−) appearing near 710–720 cm−1 and 870–880 cm−1 [36]. This result is consistent with the well-documented detection of carbonates in concrete incorporating marble-derived residues.

In the mid-infrared region, the spectra reveal features associated with hydrated silicate phases and other mineral additions. A broad band centered near 1000 cm−1 (approximately 885–1285 cm−1) corresponds to silica phases [37]. The asymmetric Si–O stretching vibrations observed in this region are due to the presence of silicate aggregates and also the contribution of the formation of hydraulic compounds, particularly C–S–H, the primary strength-bearing phase in cementitious systems [36]. In addition, variations in the spectral region between 1350 cm−1 and 1600 cm−1 are likely associated with the O–C–O vibrational modes [38]. However, no significant variation in peak position or intensity is detected with increasing MW content. This indicates that the presence of these bands cannot be directly correlated with MW incorporation alone and may also be influenced by the intrinsic carbonate content of cement.

Finally, the high-wavenumber region reflects contributions from water and hydroxyl groups (O–H). Changes observed in this band are attributed to molecularly bound water, while distinct peaks in this region indicate the formation of O–H bonds characteristic of cement hydration products [39]. The weak and relatively sharp bands around 3640 cm−1 may be assigned to the O–H stretching vibration of Ca(OH)2, indicating the presence of crystalline calcium hydroxide in the hydrated matrix [30].

3. Discussion

The formulation with 10% MW was statistically comparable to the control, which is consistent with the literature indicating that partial replacement of cement or fine aggregate with MW is most effective at moderate levels. Studies have shown that partial replacement of Portland cement with MW up to 10% can improve mechanical properties [35,40]. Maintaining or increasing strength at the 10% level is attributed to the “micro-filler effect,” in which fine particles (such as MW powder) act as an inert filler material, occupying voids and increasing the packing density of the mixture [34]. The filling of voids and the improvement in packing density are key factors contributing to strength gain or maintenance at moderate replacement levels. MW powder has the ability to penetrate the porosity of the concrete’s granular structure, filling voids and reducing porosity, thus compensating for the reduction in cement content [4].

However, it is important to emphasize that the compressive strength of cementitious composites results from the combined contribution of the aggregate skeleton, the hydrated cement matrix, and the interfacial transition zone, rather than from the action of a single constituent [21,23]. Therefore, the role of MW at moderate replacement levels should be interpreted as facilitating physical densification mechanisms, rather than as a direct load-bearing contribution.

The maintenance of mechanical strength at the 10% MW replacement level is visually supported by the SEM morphological analysis, which illustrates the “micro-filler effect”. A direct comparison between the control concrete block (CB, Figure 4a) and the sample with 10% MW (CB, Figure 4b) elucidates certain characteristics. Figure 4b clearly demonstrates the presence of numerous fine MW particles dispersed and well-integrated into the cementitious matrix, a characteristic absent in the control sample (Figure 4a). This visual observation is consistent with the micro-filler mechanism. The MW particles (whose wide range size is evident in Figure 4e) can act by filling the voids within the matrix. This effective void-filling effect significantly improves the local packing density, which is crucial for compensating for the reduced cement content at moderate replacement levels and, consequently, ensuring the maintenance of the composite’s strength.

The significant decrease in compressive strength observed at higher replacement levels (above 10% for CBs) is a direct consequence of the inert nature of MW. The XRD analysis (Figure 5) confirmed that MW is composed primarily of SiO2 and CaCO3. The characteristic and well-defined SiO2 and CaCO3 peaks at 26.6 and 29.4°, respectively, are prominent in the samples containing MW. The FTIR analysis also confirmed this inert composition of the residue, as the identified peaks (such as Si-O-Si and O-C-O) validate that the MW is majorly SiO2 and CaCO3, a material that does not actively participate in the pozzolanic reaction. In addition, the presence of a broad diffraction feature associated with amorphous C–S–H in all cementitious samples indicates that strength preservation at low MW contents is linked to maintaining an effective volume of hydration products, rather than to any chemical activation of MW. For this reason, it is more suitable as a partial replacement for sand rather than cement [17]. When incorporated at high concentrations, its inert character leads to a decline in performance, which is attributed to increased porosity in the hardened cement paste [41]. This reduction in strength is explained by the dilution effect, in which the addition of inert materials (such as marble residue) decreases the concentration of calcium silicate phases and other cementitious components that are essential for compressive strength [42].

Water absorption in the CBs increased significantly with the addition of MW, surpassing the maximum limit of 7% established by ABNT NBR 9781. This increase in water absorption is directly related to the rise in void content within the matrix. Excessive substitution of cement with an inert material can increase porosity, thereby compromising durability. Other studies have also reported increases in water absorption and porosity as the MW replacement level rises [18,43]. Some authors have further suggested that concrete becomes less durable with MW incorporation due to the increase in surface water absorption [43]. Therefore, although certain studies indicate that fine marble powder, when used as a partial replacement for fine aggregate at optimal levels, may reduce water absorption through pore-filling effects, higher replacement rates lead to reduced strength and increased water absorption [44].

The high permeability of the PCBs is attributed to their interconnected pore structure [45]. The highest permeability values were observed in the control and 30% MW replacement treatments. In the control, permeability is high because no MW is present; therefore, the micro-filler effect does not contribute to pore refinement. As MW content increases, the micro-filler effect improves matrix packing up to an optimal point. Beyond this point, however, the dilution effect becomes dominant, reducing the amount of cementitious material and increasing voids. A similar trend was reported by other study, who observed a decrease in porosity up to a 30% MW replacement, followed by an increase at higher levels [46]. Since porosity and permeability are intrinsically linked [12], the increase in porosity beyond the optimal replacement level suggests a corresponding increase in permeability. Thus, the high MW content (30% cement replacement), which leads to a less dense microstructure due to the dilution effect, likely increased the number of interconnected voids, resulting in a higher permeability rate [47].

This result suggests a trade-off between strength and permeability, as the formulation with 30% MW may be hydraulically efficient (high permeability) but exhibits lower compressive strength compared with the control. When selecting the most suitable replacement level, the expected traffic load must be considered, given that strength is inversely related to total porosity. PCBs are generally used in low-traffic areas or sidewalks [45], where hydraulic performance may, depending on the application, be prioritized over mechanical strength.

To compare the experimental results obtained in this work, Table 1 and Table 2 present a comparative summary of the mechanical and durability properties reported in the literature for CB and PCB samples incorporating marble residue.

Table 1.

Literature results for marble waste substitution in concrete paver blocks (CBs).

Table 2.

Literature results for marble waste substitution in pervious concrete paver blocks (PCBs).

For CBs, the compressive strength values reported in the literature generally range from approximately 35 to 50 MPa, depending on the replacement level, particle size distribution and composition of the marble waste, and mixture design. The compressive strength obtained in this study (31.18 ± 6.49 MPa) is slightly lower than the upper values reported but remains within a technically relevant range for paving applications. Similarly, the water absorption values compiled in Table 1 indicate that increases in absorption with marble waste incorporation are a common trend, particularly at higher replacement levels, supporting the durability-related behavior observed in the present work.

In the case of PCBs, Table 2 highlights the wide variability in both compressive strength and permeability reported in the literature, reflecting the strong influence of porosity and aggregate skeleton on performance. The compressive strength (15.28 ± 3.98 MPa) and permeability (21 mm/s) obtained in this study fall within the ranges reported by previous investigations, indicating that the mixtures developed herein achieved a balance between mechanical resistance and hydraulic functionality, comparable to that of similar systems reported in the literature.

Overall, the comparative analysis presented in Table 1 and Table 2 confirms that the experimental results obtained in this study are consistent with previously reported data for concretes incorporating marble waste. This agreement reinforces the validity of the observed trends and supports the technical feasibility of using marble waste in both conventional and pervious concrete blocks for paving applications.

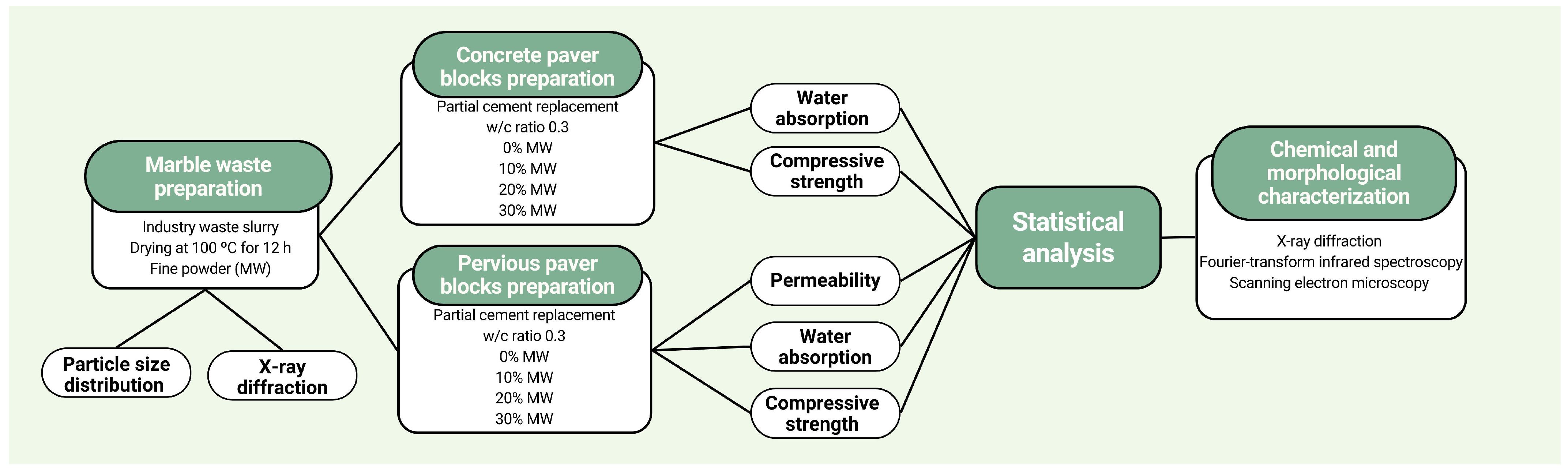

4. Materials and Methods

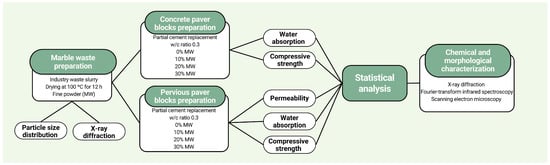

The concrete paver blocks (CBs and PCBs) were produced in partnership with a company located in Maringá-PR (Brazil) that specializes in the manufacturing of concrete products. Compressive strength, water absorption, and permeability tests (for PCB specimens) were carried out in triplicate. Figure 7 illustrates the stages of the adopted methodology, which followed the procedures established in NBR 16416 [27], concerning permeable concrete pavements.

Figure 7.

Flowchart of the experimental methods.

4.1. Materials

The study employed the following materials, cement (InterCement Brasil, São Paulo, Brazil), coarse aggregate, sand, chemical additive (Liquiplast-1400, Tecnomor, Palhoça, Brazil), and the industrial residue, which were sourced primarily from a company located in Maringá, Paraná State, Brazil. The study employed the structural cement brand CP V ARI–ABNT NBR 16697 [52] (equivalent to Type III–ASTM C150/C150M), which is known for its high early strength and structural characteristics. The characteristics of the cement used in this study are present in Table 3.

Table 3.

Chemical composition and physical properties of cement.

The chemical additive Liquiplast-1400 (Tecnomor) was used as a high-performance water-reducing superplasticizer, contributing to the dispersion of cement particles by decreasing flocculation forces. Its mechanism of action consists of the adsorption of the additive molecules onto the surface of cement grains, which induces repulsion between particles and promotes a more uniform distribution within the mixture. As a result, a significant improvement in concrete workability was observed, allowing for a reduction in water content without compromising consistency. In addition, this contributes to a denser cementitious matrix, with the potential to enhance mechanical properties.

The industrial residue used was MW, a by-product from the ornamental stone processing industry. The MW was supplied by a marble company located in Maringá, PR, Brazil. Initially, the MW is discarded as slurry/mud resulting from the cutting and sanding processes. To enable its incorporation into the concrete mixture, the material was subjected to controlled oven drying at approximately 100 °C for 12 h. This standardized procedure is essential for removing excessive moisture from fine ornamental stone residues. Upon completion of this preparation, the MW achieved a fine powder consistency, making it suitable for incorporation as a supplementary cementitious material or aggregate substitute.

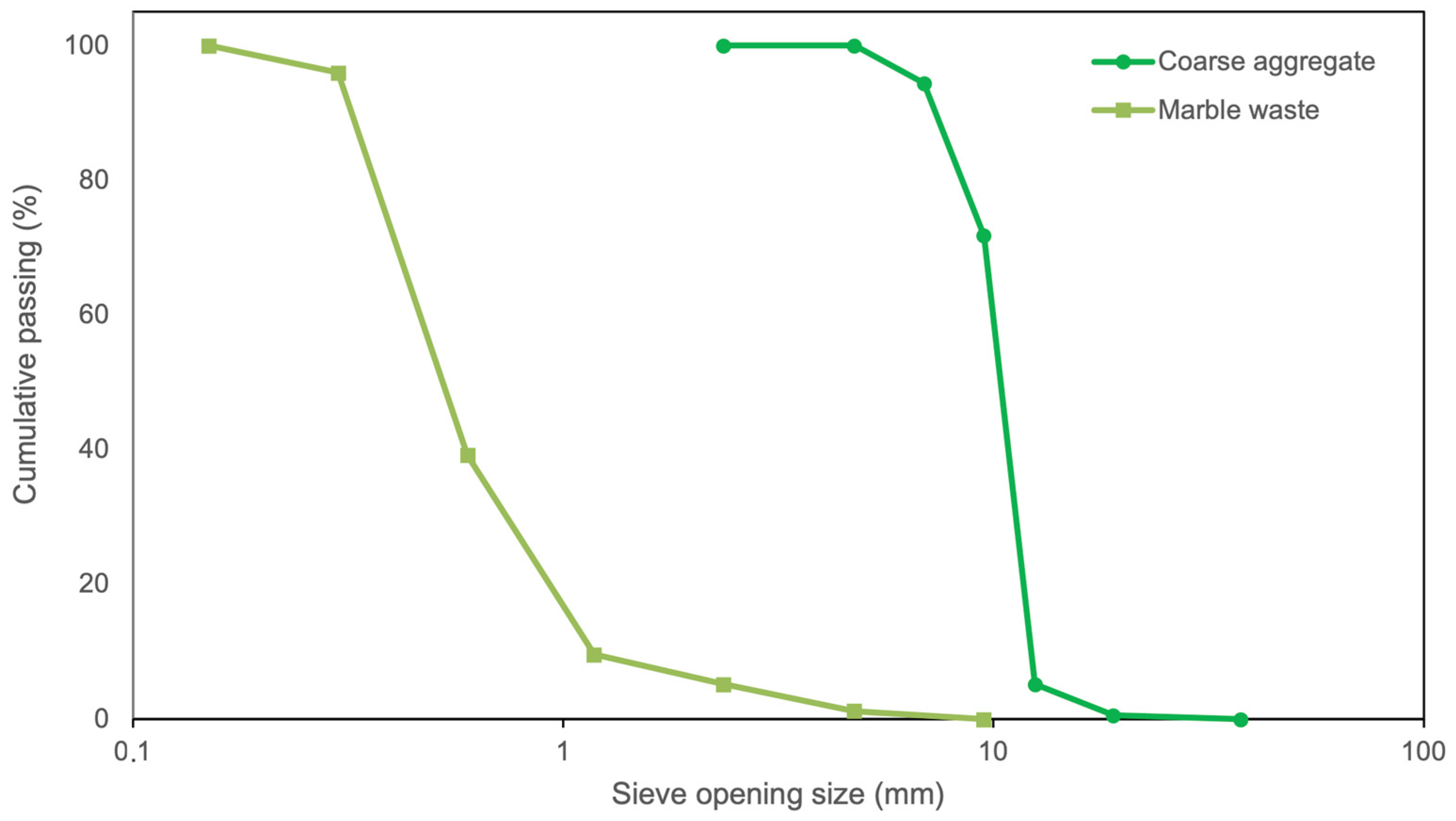

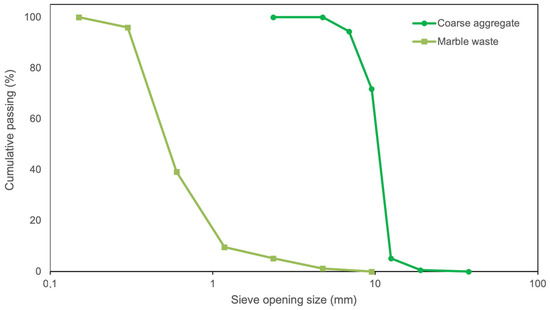

Figure 8 displays the particle size distribution analysis of the MW and the coarse aggregate. The coarse aggregate selected was crushed stone, with a particle size range of 4.8 mm to 9.5 mm. The blue line represents the percentage retained in each sieve and indicates that the MW accumulated primarily in the sieves ranging from 150 μm to 2.36 mm. The retained values shown in the sieves on the blue line below refer to the granulometry of the MW. The coarse aggregate exhibited a particle size distribution between 2.36 mm and 12.5 mm.

Figure 8.

Particle size distribution curve of marble residue and coarse aggregate.

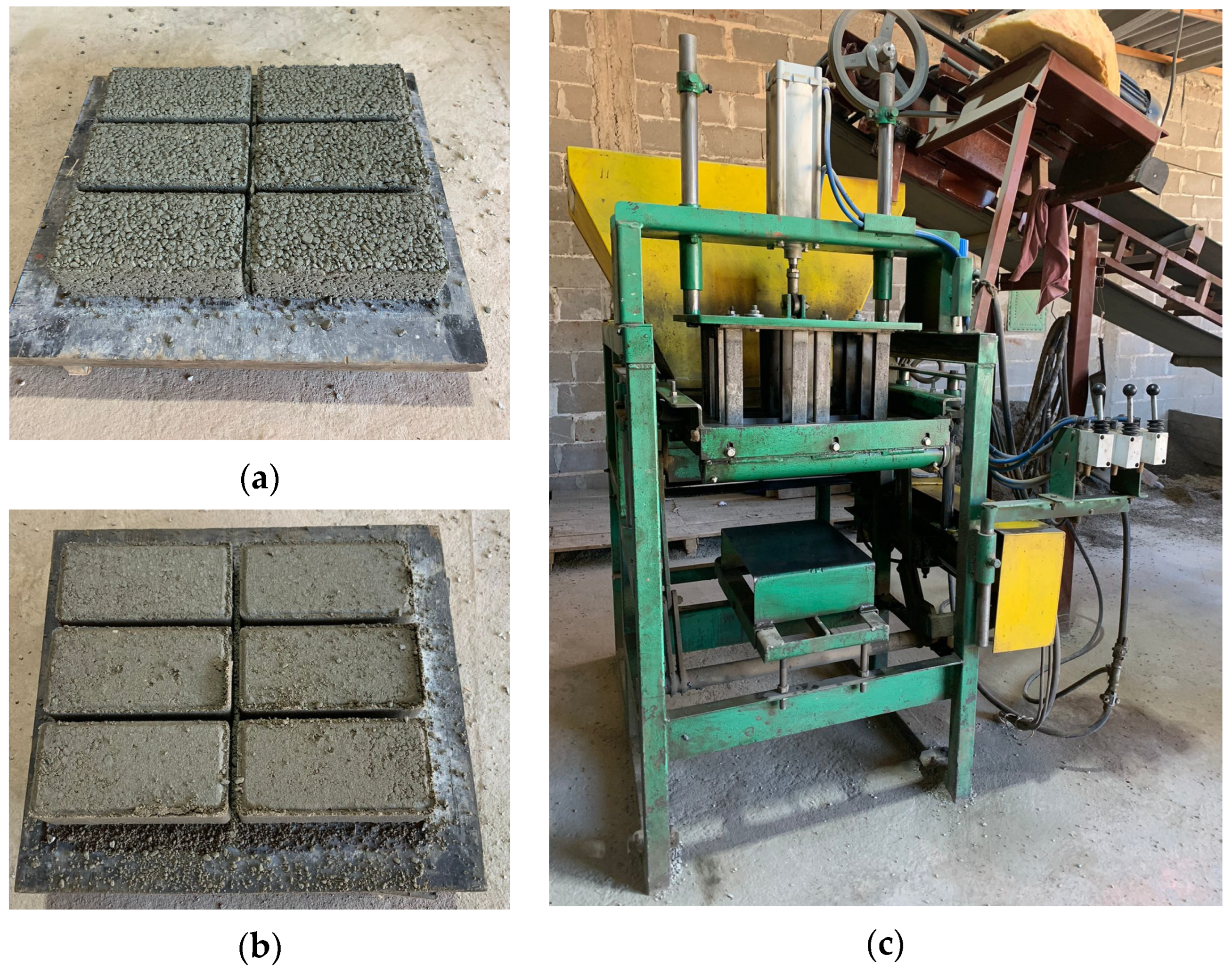

4.2. Concrete Paver Block Preparation

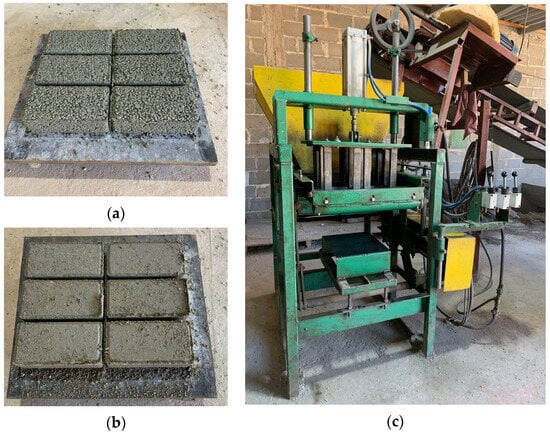

The PCBs (Figure 9a) were produced using a mixture proportion of 4:1:1 (by volume) of coarse aggregate, sand, and cement, respectively, while the CBs (Figure 9b) were prepared with a mixture proportion of 1.5:3:3:1 (by volume) of coarse aggregate, sand, stone powder (with particle size range of 0.15–4.75 mm and typical specific gravity of 2.60–2.75 g/cm3), and Portland cement, respectively. To improve workability and performance, in both mixtures, a chemical additive (plasticizing) was incorporated. Each batch utilized 600 mL of an additive solution, prepared by diluting 25 mL of the concentrated product in 575 mL of water, with a total water volume of approximately 4 L per batch.

Figure 9.

(a) Pervious concrete paver blocks, (b) concrete paver blocks, and (c) equipment used for manufacturing paver blocks.

Manufacturing was performed using a QMP6 semi-automatic pneumatic machine (QualyMáquina, São Paulo, Brazil), which employs high-frequency vibration and high-pressure compaction (Figure 9c). All specimens were produced with a uniform thickness of 60 mm and a constant water-to-cement (W/C) ratio of 0.3.

The specimens were cured under typical ambient conditions of the region (Maringá, Brazil). After demolding, the paving blocks were stacked and subjected to an initial curing stage under plastic sheet coverage, remaining in a closed environment protected from direct solar radiation, wind, and rainfall for a period of 48 h, to prevent premature moisture loss. Subsequently, the specimens were transferred to a covered and protected environment, where they remained under ambient temperature curing until completing a total curing period of 28 days.

In the experimental groups, MW served as a partial mass replacement for cement at three substitution levels: 10%, 20%, and 30%. In accordance with Brazilian technical standards [27], the sampling consisted of six specimens for mechanical testing and three specimens for physical property characterization.

4.3. Performance Tests

Performance tests were executed in accordance with Brazilian normative standards for concrete paving units [26]. For both PCB and the CB, tests for compressive strength and water absorption were performed. Additionally, the permeability coefficient test was included for the PCBs, as this is mandatory according to the specific standard for pervious pavements [27].

4.3.1. Compressive Strength

For compressive strength tests, the specimens were immersed in water at 23 ± 5 °C for a minimum of 24 h prior to testing. Immediately afterward, the loading surfaces were capped. The specimens were then placed on the auxiliary testing plates, with the top face in contact with the upper auxiliary plate. This ensured that the vertical axis passing through the specimen’s center aligned with the vertical axis passing through the center of the plates, within the area of the unit having a minimum width of 9.7 cm. The test was conducted using a compression testing machine (PCE100C, Emic, São José dos Pinhais, Brazil) with a continuous loading rate of 550 kPa/s and a tolerance of 200 kPa/s, until the complete failure (rupture) of the specimen.

4.3.2. Water Absorption

Prior to the water absorption test, the specimens were oven-dried for 24 h until constant mass. Subsequently, the specimens were immersed in water at 25 ± 2 °C for a period of 24 h, in accordance with the procedures established in the applicable Brazilian technical standards [26]. Subsequently, the water absorption value for each specimen was calculated using Equation (1).

where

is the absorption of each specimen, expressed as a percentage (%);

is the mass of the dry specimen, expressed in grams (g);

is the mass of the saturated specimen, expressed in grams (g).

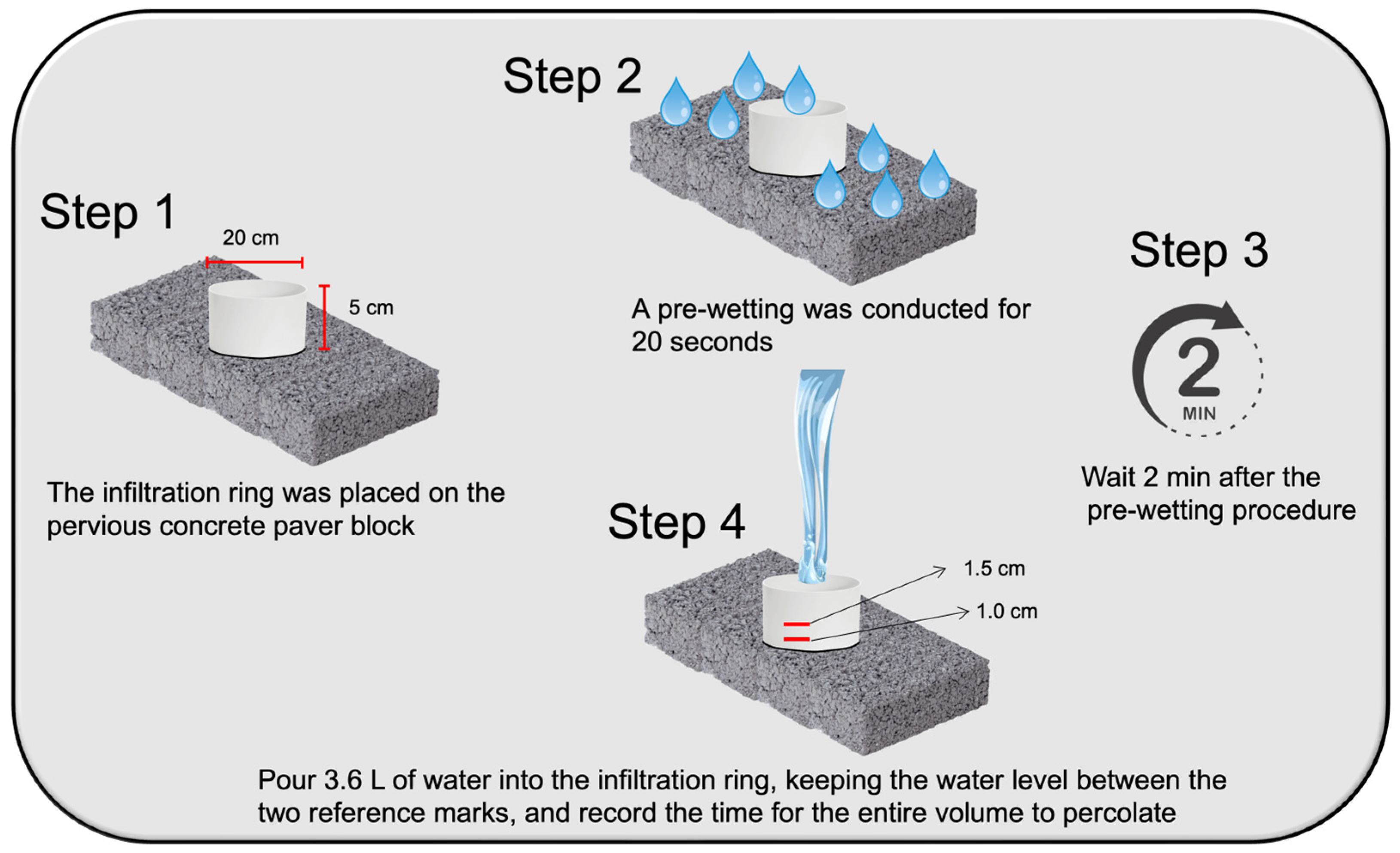

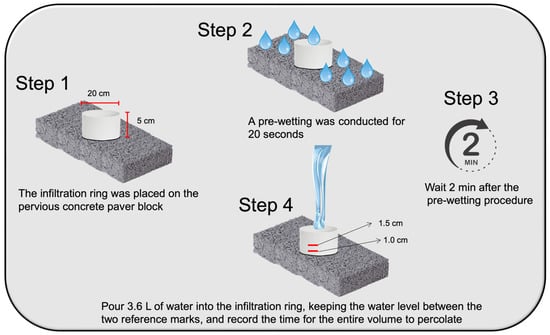

4.3.3. Permeability

The test for determining the permeability coefficient was conducted according to the Brazilian technical standard [27] as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Scheme of the steps for the permeability test.

The permeability coefficient (k) was calculated using Equation (2).

where

is the permeability coefficient, expressed in millimeters per hour (mm/h);

is the mass of the infiltrated water, expressed in kilogram (kg);

is the internal diameter of the infiltration cylinder, expressed in millimeter (mm);

is the time required for all the water to percolate, expressed in seconds (s);

is the unit conversion factor from the SI system, with a value equal to 4,583,666,000.

4.3.4. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis of the performance data, which included compressive strength, permeability, and water absorption tests, was conducted to determine the mix design that provided the best performance. To evaluate the impact of the different proportions of MW (0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% replacement) on compressive strength, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized. The objective was to verify the existence of statistically significant differences among the tested groups. When ANOVA indicated significant differences, the Tukey post hoc test was applied. This test is crucial for identifying which pairs of MW replacement percentages (the treatments) exhibited significantly distinct mean strengths, thus offering the necessary detail for decision-making regarding the most effective formulations.

4.4. Chemical and Morphological Characterization

Based on the statistical analyses, the samples with the best performance were selected for chemical and morphological characterizations and compared with the control specimens. For functional group determination, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy was conducted on a Shimadzu equipment, IR PRESTIGE 21 model (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). The samples were prepared by the KBr pellet method, employing a scanning range of 4000–400 cm−1. The surface morphology was investigated with a Shimadzu SS-550 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Finally, the identification of crystalline phases was carried out by an X-ray diffraction (XRD) technique utilizing a Shimadzu XRD 6000 (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) equipment.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the incorporation of MW into CB and CPB constitutes a technically viable strategy for enhancing the performance of cementitious matrices. The central finding is that MW acts as a functional mineral addition that optimizes the matrix microstructure through a significant micro-filler effect. At an optimal content of 10%, the MW particles synergistically improved the matrix microstructure through improved packing and the mitigation of micro-voids, without compromising the clinker hydration kinetics. This preservation of mechanical performance is attributed to physical densification mechanisms that improve particle packing and refine the pore structure, rather than to any chemical interaction between MW and cement hydration products. Microstructural analyses confirmed that MW acts primarily as an inert filler, improving particle packing at moderate contents but inducing dilution effects at higher levels. The maintenance of compressive strength at low MW contents is associated with the preservation of an effective volume of amorphous C–S–H, which is the main strength-bearing phase in cementitious systems. These findings highlight the importance of mix design optimization to balance mechanical performance, permeability, and durability. This structural enhancement allows for a potential reduction in clinker content without compromising structural integrity, as the increased resistance provided by the physical densification compensates for a lower cement volume. Consequently, the incorporation of marble waste represents a viable pathway to reduce cement consumption, mitigate industrial waste disposal, and support sustainable urban drainage systems, reinforcing the role of paving materials in advancing low-impact infrastructure and sustainable construction practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.V.B. and N.U.Y.; methodology, A.C.V.B. and M.E.C.F.; software, A.C.V.B., W.L.d.O. and M.E.C.F.; validation, A.C.V.B. and N.U.Y.; formal analysis, W.L.d.O., N.U.Y. and L.F.B.R.; investigation, A.C.V.B. and M.E.C.F.; resources, J.E.G. and N.U.Y.; data curation, A.C.V.B. and M.E.C.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.V.B.; writing—review and editing, N.U.Y. and L.F.B.R.; visualization, A.C.V.B.; supervision, N.U.Y.; project administration, N.U.Y.; funding acquisition, N.U.Y. and J.E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES, Brazil)—Finance Code 001, through the Master’s scholarship awarded to A.C.V.B. (grant number 88887.671413/2022-00). This work was also supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Brazil) through the Doctoral scholarship awarded to M.E.C.F. (grant number 144939/2022-3), and Research Productivity fellowships awarded to N.U.Y. (grant number 312892/2025-0) and J.E.G. (grant number 309838/2022-3). Additionally, the authors acknowledge the Research Productivity grants provided to N.U.Y. and J.E.G. by the Cesumar Institute of Science, Technology, and Innovation (ICETI).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Thelma e Tania Company (Maringá, Brazil) for the donation of marble waste. We also express our gratitude to Engineer Thiago Shiguehiro Suzuqui Kato and Building Kontrol Engenharia Ltda (Maringá, Brazil) for their technical support in conducting the compressive strength, water absorption, and permeability tests. Additionally, the authors acknowledge the Complex of Research Support Centers (COMCAP) at the State University of Maringá (UEM, Brazil) for the SEM, XRD, and FTIR analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Monrose, J.; Tota-Maharaj, K.; Mwasha, A.; Hills, C. Effect of Carbon-Negative Aggregates on the Strength Properties of Concrete for Permeable Pavements. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2020, 21, 1823–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichael, I.; Voukkali, I.; Loizia, P.; Zorpas, A.A. Construction and Demolition Waste Framework of Circular Economy: A Mini Review. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 1728–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, L.N.; Ghisi, E.; Thives, L.P. Permeable Pavements Life Cycle Assessment: A Literature Review. Water 2018, 10, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M.; Shahzada, K.; Iqbal, M.; Khan, E.A. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Paver Blocks by Replacing Cement with Fly Ash and Marble Waste. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, E.M.; Machado de Oliveira, E.; de Oliveira, C.M.; Dal-Bó, A.G.; Peterson, M. Performance Analysis of Paver Blocks Manufactured with an Incorporation of Waste from the Disposable Straw Industry. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2022, 24, 1757–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, Y.; Gupta, T.; Sharma, R.K. Effect of Compaction Technique on Single Used Polythene Bag Waste Concrete Paver Blocks: Mechanical and Durability Performance. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboo, N.; Nirmal Prasad, A.; Sukhija, M.; Chaudhary, M.; Chandrappa, A.K. Effect of the Use of Recycled Asphalt Pavement (RAP) Aggregates on the Performance of Pervious Paver Blocks (PPB). Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262, 120581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supit, S.; Priyono. Utilization of modified plastic waste on the porous concrete block containing fine aggregate. J. Teknol. Sci. Eng. 2023, 85, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Akin, M.; Shi, X. Permeable Concrete Pavements: A Review of Environmental Benefits and Durability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1605–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins Vaz, I.C.; Antunes, L.N.; Ghisi, E.; Thives, L.P. Permeable Pavements as a Means to Save Water in Buildings: State of the Art in Brazil. Sci 2021, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liang, C.; Wang, C.; Ma, Z. Properties of Green Mortar Blended with Waste Concrete-Brick Powder at Various Components, Replacement Ratios and Particle Sizes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 342, 128050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, N.; Minh, P.; Giang, N.; Dung, N.; Kawamoto, K. Porosity and permeability of pervious concrete using construction and demolition waste in Vietnam. Int. J. Geomate 2023, 24, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebello, T.A.; Zulcão, R.; Calmon, J.L.; Gonçalves, R.F. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Ornamental Stone Processing Waste Recycling, Sand, Clay and Limestone Filler. Waste Manag. Res. 2019, 37, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthibala, R.K.; Vasanthi, P.; Hariharasudhan, C.; Partheeban, P. A Critical Review on Recycling and Reuse of Construction and Demolition Waste Materials. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 12, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, G.; Grosso, C.; Palmieri, R.; Serranti, S. Current Trends and Challenges in Construction and Demolition Waste Recycling. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2025, 53, 101032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyousef, R.; Benjeddou, O.; Soussi, C.; Khadimallah, M.; Jedidi, M. Experimental Study of New Insulation Lightweight Concrete Block Floor Based on Perlite Aggregate, Natural Sand, and Sand Obtained from Marble Waste. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 8160461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Balaji, S.; Selvapraveen, S.; Kulanthaivel, P. Laboratory Study on Mechanical Properties of Self Compacting Concrete Using Marble Waste and Polypropylene Fiber. Clean. Mater. 2022, 6, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhalilou, M.; Belachia, M.; Houari, H.; Abdelouahed, A. The study of the characteristics of sand concrete based on marble waste sand. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2020, 30, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khyaliya, R.K.; Kabeer, K.I.S.A.; Vyas, A.K. Evaluation of Strength and Durability of Lean Mortar Mixes Containing Marble Waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 147, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboya, F.; Xavier, G.C.; Alexandre, J. The Use of the Powder Marble By-Product to Enhance the Properties of Brick Ceramic. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 1950–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezzerini, M.; Luti, L.; Aquino, A.; Gallello, G.; Pagnotta, S. Effect of Marble Waste Powder as a Binder Replacement on the Mechanical Resistance of Cement Mortars. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şanal, İ. Significance of Concrete Production in Terms of Carbondioxide Emissions: Social and Environmental Impacts. Politek. Derg. 2018, 21, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jia, J.; Qi, Z.; Dong, S.; Mou, Y.; Zhu, M. Impact of Synthetic C-S-H-Go Seeds on Hydration Kinetics and Pore Structure Evolution of Cement Pastes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2026, 168, 106470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El maguana, Y.; Elhadiri, N.; Bouchdoug, M.; Benchanaa, M. Valorization of Powdered Marble as an Adsorbent for Removal of Methylene Blue Using Response Surface Methodology. Appl. J. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2019, 5, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Dong, Y.; Qiu, T.; Lv, J.; Guo, P.; Liu, X. The Microstructure and Modification of the Interfacial Transition Zone in Lightweight Aggregate Concrete: A Review. Buildings 2025, 15, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas (ABNT). NBR 9781: Concrete Paving Units-Specification and Test Methods; ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas (ABNT). NBR 16416: Pervious Concrete Pavement-Requirements and Procedures; ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseka, I.; Mohotti, D.; Wijesooriya, K.; Lee, C.-K.; Mendis, P. Influence of Graphene Oxide on Abrasion Resistance and Strength of Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 404, 133280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, S.; Dong, S.; Yu, X.; Yang, R.; Ou, J. Nano-Core Effect in Nano-Engineered Cementitious Composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 95, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Khitab, A.; Mehmood, K.; Tayyab, S. Green Non-Load Bearing Concrete Blocks Incorporating Industrial Wastes. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dong, S.; Ashour, A.; Zhang, W.; Han, B. Effect and Mechanisms of Nanomaterials on Interface between Aggregates and Cement Mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 240, 117942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dong, S.; Li, Z.; Han, B.; Ou, J. Nanomechanical Characteristics of Interfacial Transition Zone in Nano-Engineered Concrete. Engineering 2022, 17, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G.; Öz, A.; Bayrak, B.; Aydin, A. The Effect of Geopolymer Slurries with Clinker Aggregates and Marble Waste Powder on Embodied Energy and High-Temperature Resistance in Prepacked Concrete: ANFIS-Based Prediction Model. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 67, 105987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babouri, L.; Biskri, Y.; Khadraoui, F.; El Mendili, Y. Mechanical Performance and Corrosion Resistance of Reinforced Concrete with Marble Waste. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 4112–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djebien, R.; Hebhoub, H.; Belachia, M.; Berdoudi, S.; Kherraf, L. Incorporation of Marble Waste as Sand in Formulation of Self-Compacting Concrete. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2018, 67, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, V.S.; Agrawal, U.; Arora, K.; Sancheti, G. FTIR Analysis of Nanomodified Cement Concrete Incorporating Nano Silica and Waste Marble Dust. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 796, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nega, D.M.; Yifru, B.W.; Taffese, W.Z.; Ayele, Y.K.; Yehualaw, M.D. Impact of Partial Replacement of Cement with a Blend of Marble and Granite Waste Powder on Mortar. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, S.; Das, S.K. Effect of Marble Slurry as a Partial Substitution of Ordinary Portland Cement in Lean Concrete Mixes. Struct. Concr. 2021, 22, E514–E527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, Q.; Qu, L.; Li, X.; Xu, S. Study of Water Absorption and Corrosion Resistance of the Mortar with Waste Marble Powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 345, 128235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikanth, P.; Saravanan, T.; Kabeer, K. Supervised Data-Driven Approach to Predict Split Tensile and Flexural Strength of Concrete with Marble Waste Powder. Clean. Mater. 2024, 11, 100231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, A.; Kabeer, K.; Vyas, A. Evaluation of Strength and Durability of Lean Concrete Mixes Containing Marble Waste as Fine Aggregate. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2020, 24, 1398–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djebien, R.; Abbas, Y.; Bouabaz, A.; Ziada, Y. Shrinkage and absorption of sand concrete containing marble waste powder. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2022, 32, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R.; Gupta, R.; Nagar, R.; Jain, A. Sorptivity Characteristics of High Strength Self-Consolidating Concrete Produced by Marble Waste Powder, Fly Ash, and Micro Silica. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 32, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadharajan, S. Determination of Mechanical Properties and Environmental Impact Due to Inclusion of Flyash and Marble Waste Powder in Concrete. Structures 2020, 25, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, G.; Pieralisi, R. Sustainable Aggregate Impact on Pervious Concrete Abrasion Resistance. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oggu, A.; Sai Madupu, L.N.K. Study on Properties of Porous Concrete Incorporating Aloevera and Marble Waste Powder as a Partial Cement Replacement. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 52, 1946–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalehnovi, M.; Rahdar, H.; Ghorbanzadeh, M.; Roshan, N.; Ghalehnovi, S. Effect of Marble Waste Powder and Silica Fume on the Bond Behavior of Corroded Reinforcing Bar Embedded in Concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04022460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaly, A.O.; El-Kaliouby, B.A.; Shalaby, B.N.; El-Gohary, A.M.; Rashwan, M.A. Effects of Marble Sludge Incorporation on the Properties of Cement Composites and Concrete Paving Blocks. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashwan, M.A.; Al-Basiony, T.M.; Mashaly, A.O.; Khalil, M.M. Behaviour of Fresh and Hardened Concrete Incorporating Marble and Granite Sludge as Cement Replacement. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencel, O.; Ozel, C.; Koksal, F.; Erdogmus, E.; Martínez-Barrera, G.; Brostow, W. Properties of Concrete Paving Blocks Made with Waste Marble. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 21, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimon, A.; Istiqomah, I.; Kudwadi, B. Effect of Marble Waste Aggregate Percentage with Fly Ash Admixture toward Compressive Strength of Pervious Concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 830, 022062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas (ABNT). NBR 16697: Portland Cement-Requirements 2018; ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.