Abstract

This study investigates the processability and performance limits of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) recovered from mixed polyolefin waste under realistic mechanical recycling conditions. The waste stream was processed by extrusion and injection molding, with parameters actively adapted. ATR-FTIR and DSC analysis confirmed HDPE as the matrix, contaminated with minor fractions of polypropylene (PP), PET, and polyurethane (PU). The reprocessed material exhibited a single melting peak at 132 °C and a melt flow rate (MFR) of 9.9 ± 0.6 g 10 min−1, indicative of moderate degradation. Mechanical testing revealed reduced tensile strength and elongation at break compared to virgin HDPE, indicating compositional heterogeneity and poor interfacial adhesion. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) revealed dispersed inclusions and microvoids acting as stress concentrators, consistent with reduced ductility. Crucially, progressive reduction of back pressure during processing optimization was essential for stabilizing melt flow and minimizing shear-induced degradation. This adjustment enabled consistent mold filling despite the material’s variability. The results demonstrate that mixed HDPE waste can be successfully valorized for non-structural applications such as plastic lumber or pallets, providing a sustainable pathway for recycling heterogeneous streams without costly pre-treatment or compatibilization.

1. Introduction

Polyolefins, including polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP), are the most widely used class of polymers in packaging applications due to their favorable balance of mechanical strength, chemical resistance, low density, and cost-effectiveness [1]. Their versatility and ease of processing by extrusion, blow molding, and injection molding make them indispensable in both food and non-food packaging, where performance, durability, and economic viability are critical. Packaging alone accounts for more than 40% of global plastic consumption, underscoring the central role of polyolefins in the packaging sector and the growing environmental concerns surrounding their end-of-life management [2]. Although their chemical inertness provides durability during use, it also delays degradation. This fact relies on the accumulation of vast amounts of post-consumer plastic packaging. Moreover, each packaging contains different additives and fillers, and can be composed of more than one type of plastic. Consequently, recycling is not straightforward, making polyolefins a key focus in the development of circular economic strategies for plastics. Recent studies have highlighted that mechanical recycling of mixed polyolefin waste remains fundamentally limited by compositional heterogeneity and polymer incompatibility, which often result in inferior mechanical properties compared to virgin materials. Despite continuous improvements in recycling technologies, contamination and phase separation remain critical bottlenecks to the high-value reuse of recycled polyolefins, particularly in real post-consumer waste streams [3,4,5,6].

Among polyolefins, high-density polyethylene (HDPE) is one of the most widely used materials in rigid packaging, employed extensively in bottles, containers, and caps for household and industrial products [7]. As a result, HDPE accounts for a significant portion of the post-consumer plastic waste stream. Mechanical recycling has become the preferred method for recovering and reintroducing this material into the production cycle, as it requires no depolymerization and can be implemented using conventional plastic processing equipment. However, the effectiveness of mechanical recycling strongly depends on the purity of the input waste. In practice, HDPE from post-consumer packaging is rarely isolated from other polymers, leading to impurities and non-polyolefinic contaminants, such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyurethane (PU), pigments, fillers, and residual organic matter. These components are introduced at different stages of the product life cycle, during use, collection, sorting, or reprocessing, and are difficult to remove completely [8]. Furthermore, the presence of colorants, additional polymers, and processing additives significantly complicates recycling, as they degrade the mechanical, thermal, and rheological properties of polyolefin materials [9,10].

Contamination remains a significant barrier to the high-value reuse of recycled HDPE, despite advances in processing technologies. Recent studies have reaffirmed that even small amounts of incompatible polymers and impurities in post-consumer HDPE can severely limit property recovery during mechanical recycling [4,6]. At the same time, the literature highlights the importance of exploring alternative reuse routes for contaminated polyolefin streams, such as downcycling into low-demand applications, compatibilization approaches, or integration with complementary recycling strategies, as realistic pathways to increase the value and utilization of mixed polyolefin waste [4,11].

In this way, the presence of impurities not only limits the applications and reduces the commercial value of recycled products because of the low quality of recycled material, but also leads to poor melt flow, which impairs processability, promotes surface defects, and reduces durability, which compromises the long-term performance of the recycled material [8]. The extent of the consequences depends on the nature, concentration, and distribution of contaminants within the polymer matrix, all of which influence phase morphology and mechanical behavior [12,13]. Consequently, maintaining consistent quality in recycled polyolefins remains challenging, and understanding these degradation and incompatibility phenomena is essential for producing high-quality recycled material from rigid packaging waste [14].

Although the effects of contamination and polymer incompatibility in recycled polyolefins have been widely reported, most recent studies are focused on general recycling challenges, upcycling strategies, or controlled approaches rather than on the detailed behavior of mechanically recycled materials derived from actual mixed waste streams [4,5]. In particular, post-consumer HDPE obtained from mixed polyolefin packaging remains insufficiently investigated under realistic mechanical recycling conditions, where impurity type, concentration, and distribution are notable variables [6,11]. As evidenced in recent works, there remains a lack of application-oriented studies that simultaneously assess compositional heterogeneity, processing behavior, and final material performance, which are essential for defining reusable pathways for recycled mixed polyolefin waste [11,15].

Several recent studies have investigated mechanically recycled HDPE and polyolefins derived from post-consumer or commercial streams. However, the majority focus on material characterization or quality assessment under standard conditions, leaving a gap in the systematic adaptation of processing parameters required to stabilize inherently heterogeneous mixed waste streams. This distinction highlights a critical disconnect between using real recycled post-consumer plastic waste for characterization purposes and evaluating their actual processability under industrial constraints.

Table 1 summarizes representative studies on real post-consumer or commercial recycled polyolefin streams, comparing their approach to feedstock control, impurity management, and processing optimization. As shown, while the analysis of real recycled streams is increasing, research explicitly focusing on processability limits and flexible processing strategies for heterogeneous mixed HDPE waste remains scarce. Moreover, in several cases, the considered recyclates originated from a specific post-consumer plastic product stream that was well-conditioned, at least clean, and label-free [16,17]. In this way, the problem is simplified, since the type of plastic in these particular products is always the same and the presence of impurities from other plastics is unlikely. For example, [18] worked with detergent bottles and [19] with blow-molded containers, both products made from HDPE. However, in these studies, they intentionally introduce recycled PP as impurities to analyze its influence on the final performance of recycled HDPE. Moreover, in the specific case of [18], the authors noted that recycled HDPE could not be injected due to its flow behavior, which differs significantly from that of virgin HDPE. In this regard, they use compression molding for sample preparation rather than adjusting injection parameters for recycled HDPE.

Table 1.

Comparison of representative studies on mechanically recycled HDPE/polyolefins using real waste streams.

Within the aforementioned framework, this study aims to analyze the impact of impurities on the processability and properties of recycled high-density polyethylene (HDPEw) derived from mixed polyolefin rigid packaging waste. In contrast to previous studies that rely on model blends or controlled impurity additions, this work investigates HDPEw obtained directly from a real post-consumer mixed waste stream, characterized by inherent compositional heterogeneity and limited control over impurity content.

A combination of ATR-FTIR, DSC, melt flow rate (MFR), mechanical testing, and FESEM is used to evaluate how impurities affect both microstructure and macroscopic performance under realistic mechanical recycling conditions. Furthermore, systematic optimization of extrusion and injection-molding parameters is performed to identify practical processability limits. Rather than attempting to reproduce virgin HDPE properties through additives, this study establishes flexible processing strategies to manage heterogeneity.

The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the limitations of the operational boundaries for mixed polyolefin waste. The results demonstrate that, despite compositional heterogeneity, mixed HDPE waste streams can be valorized as secondary raw materials for applications with lower mechanical requirements, offering a realistic and sustainable approach to reducing plastic waste accumulation.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Sample Preparation and HDPEw Fragments Characterization

Figure 1 shows the representative subsample of HDPEw used for characterization. From this subsample, individual fragments with distinct colors, textures, and apparent densities were selected and analyzed by attenuated total reflectance–Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to identify their polymeric composition. The results from the analysis are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Representative subsample of recycled HDPEw obtained through the quartering procedure. The individual fragments selected from the subsample, highlighting the pronounced heterogeneity in color, surface texture, and particle size characteristic of post-consumer HDPEw.

Table 2.

Photographs of selected high-density polyethylene waste (HDPEw) fragments along with corresponding sample numbers and the polymer types (ID) identified by attenuated total reflectance–Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR).

Analysis revealed the presence of multiple polymer species within the HDPEw fraction, confirming contamination and plastic type mixing during waste sorting and collection. Besides HDPE, the presence of polyurethane (PU), polypropylene/polyethylene terephthalate (PP/PET) blends, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and polypropylene/polyethylene (PP/PE) blends were also identified, illustrating the complex and heterogeneous nature of the post-consumer waste stream.

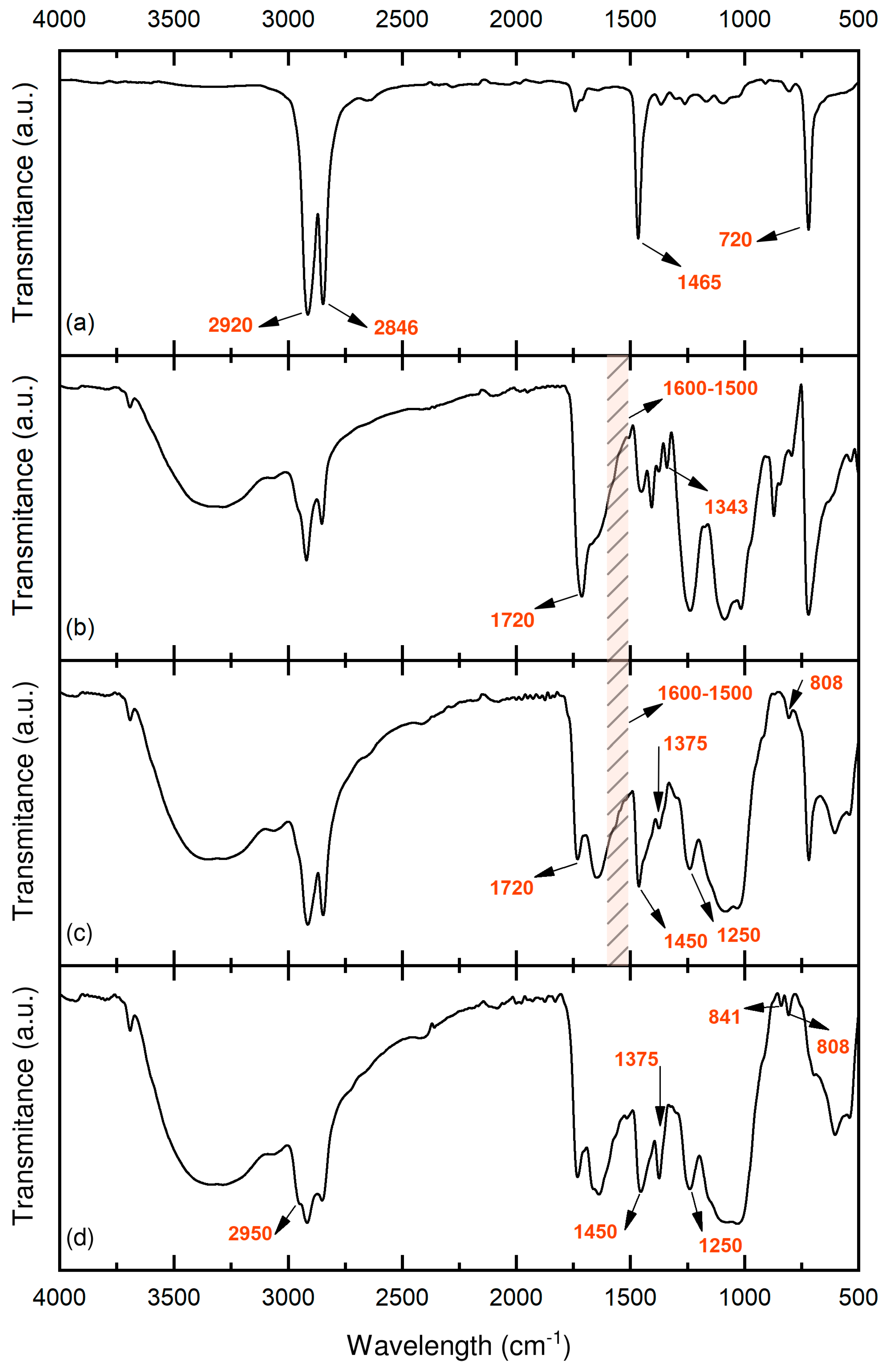

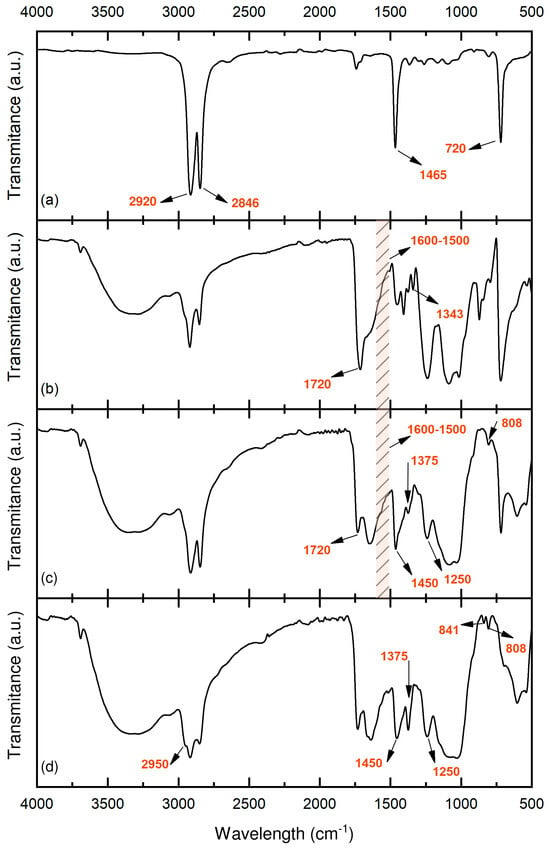

Figure 2 presents ATR-FTIR spectra of selected fragments according to different identified polymers. The spectrum of Fragment 2, chosen as a representative HDPEw sample (Figure 2a), displayed the characteristic absorption peaks of PE, including the CH2 rocking vibration at 720 cm−1, CH2 scissoring vibration at 1465 cm−1, symmetric C–H stretching at 2846 cm−1, and asymmetric C–H stretching at 2920 cm−1 [23]. These distinctive bands are characteristic of polyethylene and agree well with PE/HDPE FTIR spectra reported in the literature [23,24].

Figure 2.

FTIR-ATR spectra of: (a) Fragment 2, representative of recycled HDPEw; (b) Fragment 16, (c) Fragment 19, and (d) Fragment 21.

In contrast, fragments 16 (Figure 2b), 19 (Figure 2c), and 21 (Figure 2d) exhibited spectral features consistent with non-polyethylene polymers. Fragments 16 and 19 showed a pronounced carbonyl (C=O) stretching peak at approximately 1720 cm−1, a characteristic and intense band of PET. Particularly in fragment 19, this carbonyl peak partially overlapped with adjacent absorption bands but remained clearly identifiable. Additional PET-specific peaks were observed around 1250 cm−1, corresponding to the ester group (O=C–O–CH2) torsion, and the 1600–1500 cm−1 region, associated with aromatic ring vibrations [25]. This fragment as well as the 21 (Figure 2d) contain polypropylene (PP), evidenced by the typical methyl (–CH3) bending vibrations between 1450 and 1375 cm−1, along with peaks at 2950 cm−1 (–CH3 asymmetric stretching), 841 cm−1 (out-of-plane CH bending), and 808 cm−1 (C–C skeletal stretching), which clearly differentiate PP from HDPE [24]. Fragment 14 presented a more complex case. Its FTIR spectrum showed overlapping features of PU and PET; consequently, the polymer type cannot be accurately identified by FTIR [26]. In this regard, DSC analysis was performed on all fragments to identify the polymeric material of fragment 14 and to corroborate the FTIR-ATR results. The obtained thermograms are shown in Figure 3, along with the characteristic temperatures for each fragment.

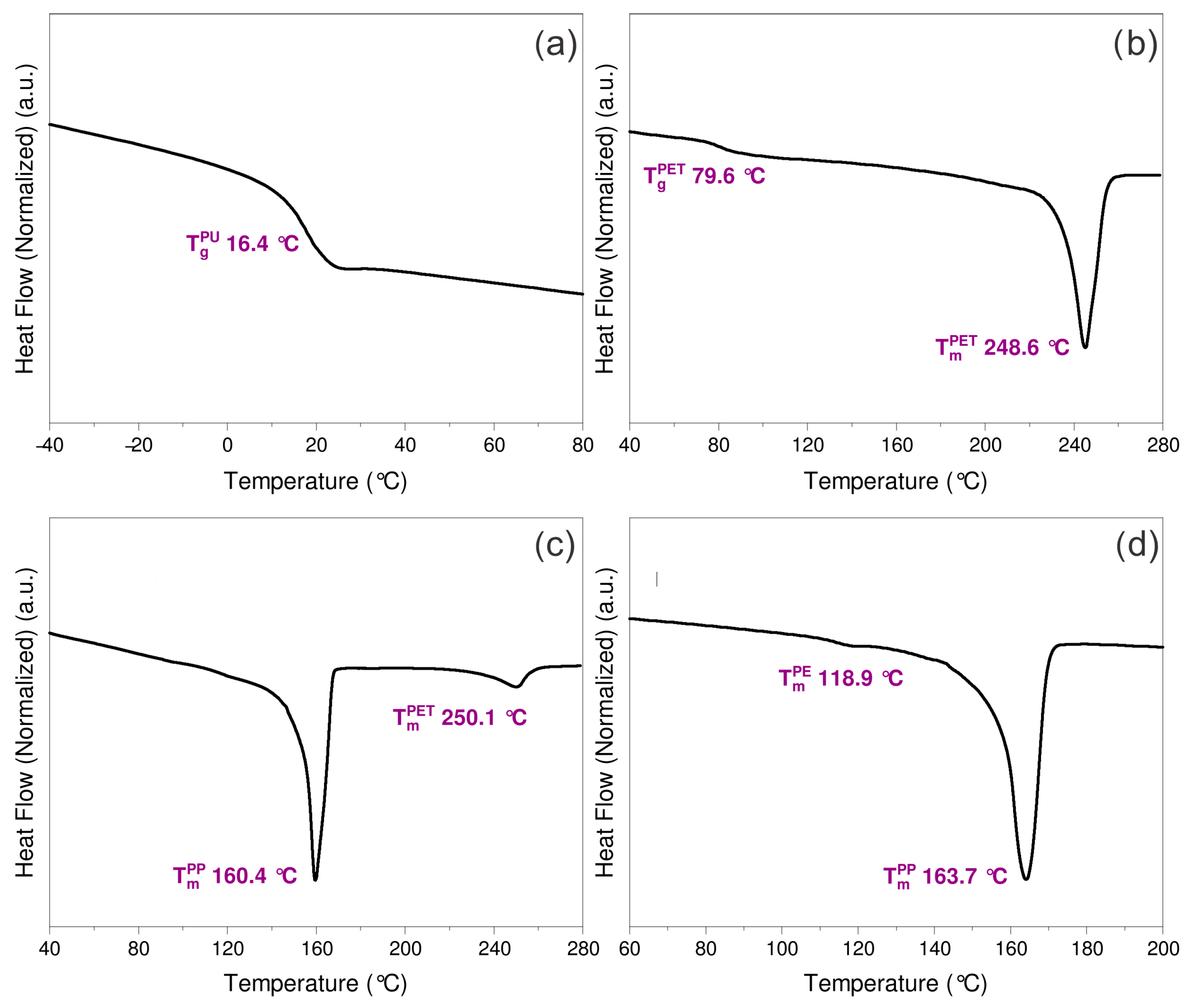

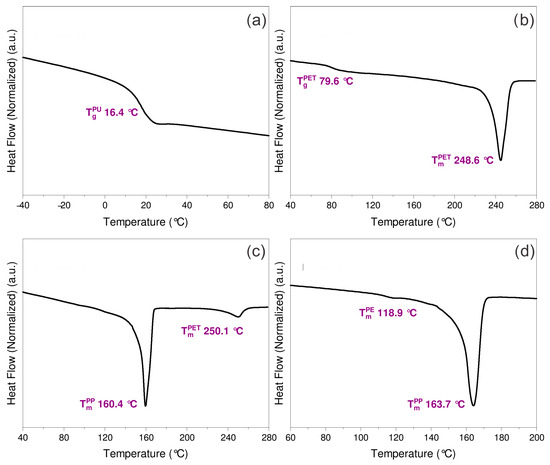

Figure 3.

DSC thermograms of (a) Fragment 14, (b) Fragment 16, (c) Fragment 19, and (d) Fragment 21.

The corresponding thermogram of fragment 14 (Figure 3a) revealed a glass transition temperature (Tg) near 20 °C, typical of PU elastomers [14]. In fragments 16 (Figure 3a) and 19 (Figure 3b), a melting temperature (Tm) of around 250 °C is observed, which corresponds to the crystalline phase of PET. Along with Tm, PET has a glass transition temperature around 80 °C [27]. This temperature is observed in the thermogram of Fragment 16 but is not detected in Fragment 19. This fact is consistent with the relative PET content in fragment 19, as expected. The Tm at approximately 160 °C, related to the PP crystalline phase, is more pronounced, indicating that PP is the significant component of the polymeric blend in this fragment. In this sense, Tg of PET is difficult to detect due to the influence of the PP crystalline phase [28]. Regarding fragment 21, the DSC thermogram exhibits two melting events, one around 120 °C and the other near 160 °C, as expected. The first one concerns the crystalline phases of PE and PP [29].

Overall, the combined ATR-FTIR and DSC analyses confirm that HDPE is the dominant component in the recovered material. However, the presence of PET, PP, PU, and blended polymers evidences the heterogeneous composition of the feedstock. This compositional variability highlights the importance of effective sorting and pre-treatment before recycling, ensuring consistent material properties and optimal processing performance. Moreover, this finding highlights the importance of adopting ecodesign strategies during the early stages of plastic packaging conception to improve post-consumer material recycling [30].

2.2. Processing Parameters

Although the recycled HDPEw exhibited a moderate melt flow rate (MFR) of 9.8 g 10 min−1, its behavior during processing showed significant flow irregularities in the extruder screw, making injection molding difficult. From an industrial perspective, this confirms that standard MFR measurements are often insufficient predictors of processability for heterogeneous post-consumer streams. Such discrepancies typically arise from the presence of immiscible phases and solid impurities, which induce local viscosity variations and can lead to screw slippage or feeding instability—critical issues for the reproducibility of industrial cycles.

2.2.1. Process Parameter Optimization

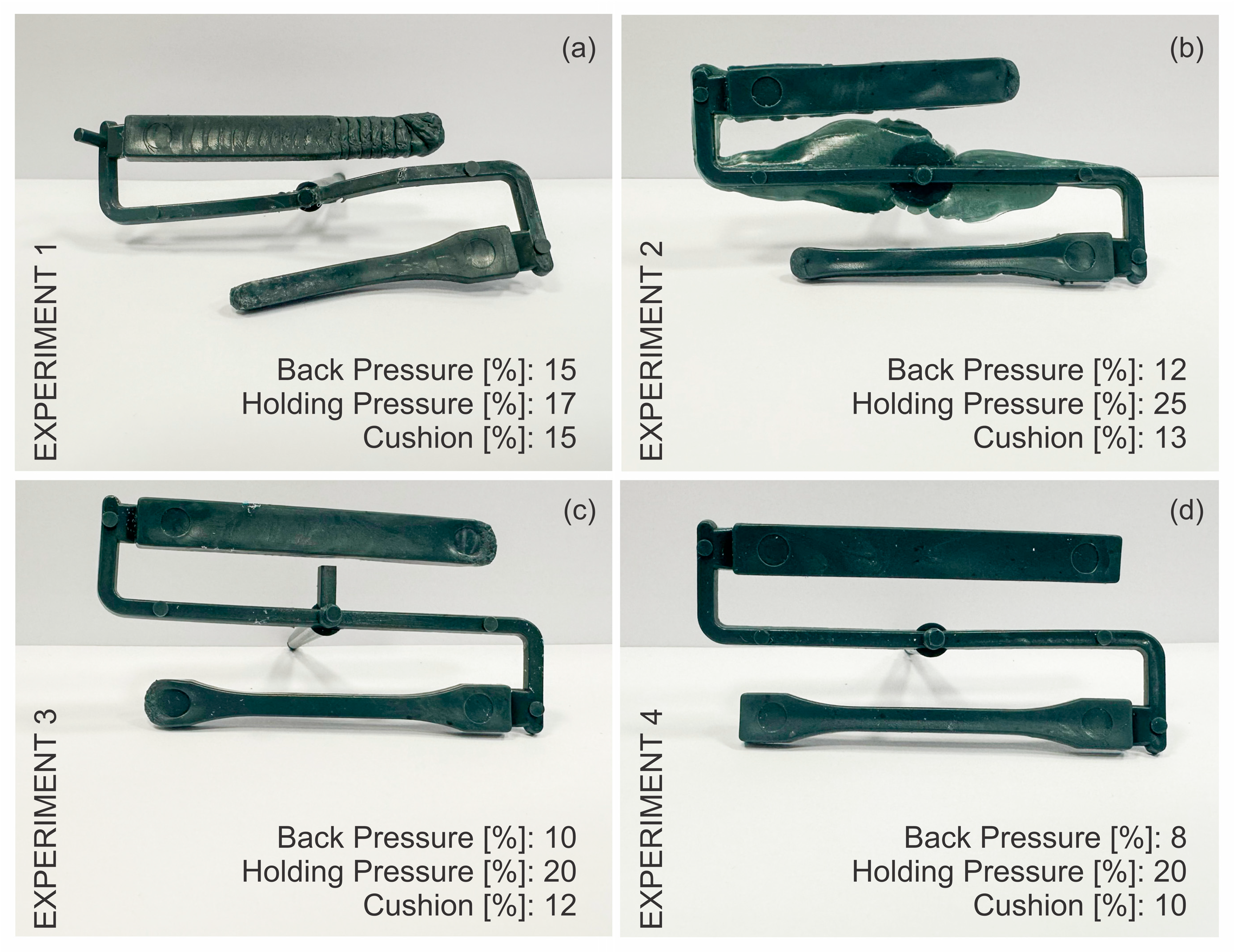

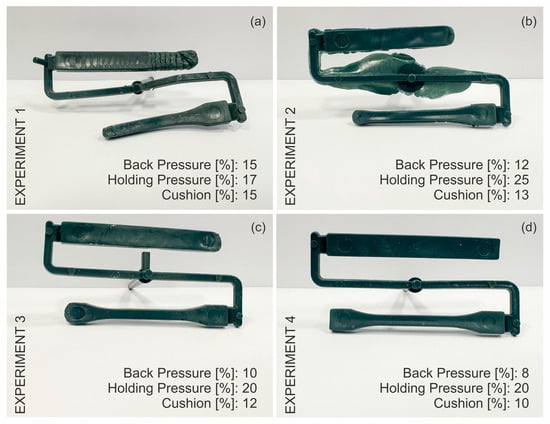

To achieve stable processing, a series of 4 injection molding experiments was conducted to optimize process parameters (Figure 4) and improve flow behavior, melt consistency, and specimen quality.

Figure 4.

Sequential adjustment of injection-molding parameters to optimize the processing of recycled HDPEw: (a) initial conditions (Experiment 1), (b) modified back and holding pressures (Experiment 2), (c) refined settings to improve flow (Experiment 3), and (d) final optimized conditions yielding complete mold filling (Experiment 4).

- Experiment 1 (Figure 4a): Standard parameters for virgin HDPE were applied. These conditions resulted in incomplete mold filling and shrinkage defects, demonstrating that industrial settings optimized for virgin resin are not directly transferable to mixed waste recyclates.

- Experiment 2 (Figure 4b): Back pressure was reduced to facilitate screw recovery, and holding pressure was increased to compensate for volumetric shrinkage. While filling improved, flashing and instability persisted.

- Experiment 3 (Figure 4c): Holding pressure was adjusted to reduce flashing, and back pressure was further lowered. These changes yielded better uniformity, but minor voids remained.

- Experiment 4 (Figure 4d): Achieving a final reduction in back pressure yielded optimal results, eliminating defects and ensuring complete filling.

2.2.2. Industrial Implications

The progressive reduction of back pressure proved to be the key factor for stabilizing the process. Unlike virgin materials, where higher back pressure is often used to enhance mixing, lower back pressure was essential for this heterogeneous HDPEw to reduce excessive shear heating and screw slip [31,32]. This adjustment minimized the thermal degradation of sensitive impurities and ensured a consistent “cushion” (the material remaining in the barrel after injection). In industrial practice, cushion stability is the primary indicator of process robustness; its stabilization in Experiment 4 confirms that the process had reached a steady state suitable for continuous production [33].

These results provide practical guidance for recyclers: when processing mixed polyolefin waste, standard “virgin” settings often lead to over-shearing and feed instability. Operators must prioritize back pressure reduction to accommodate the rheological sensitivity of mixed-waste streams, ensuring stable production even when MFR data suggests standard flow behavior [34,35,36].

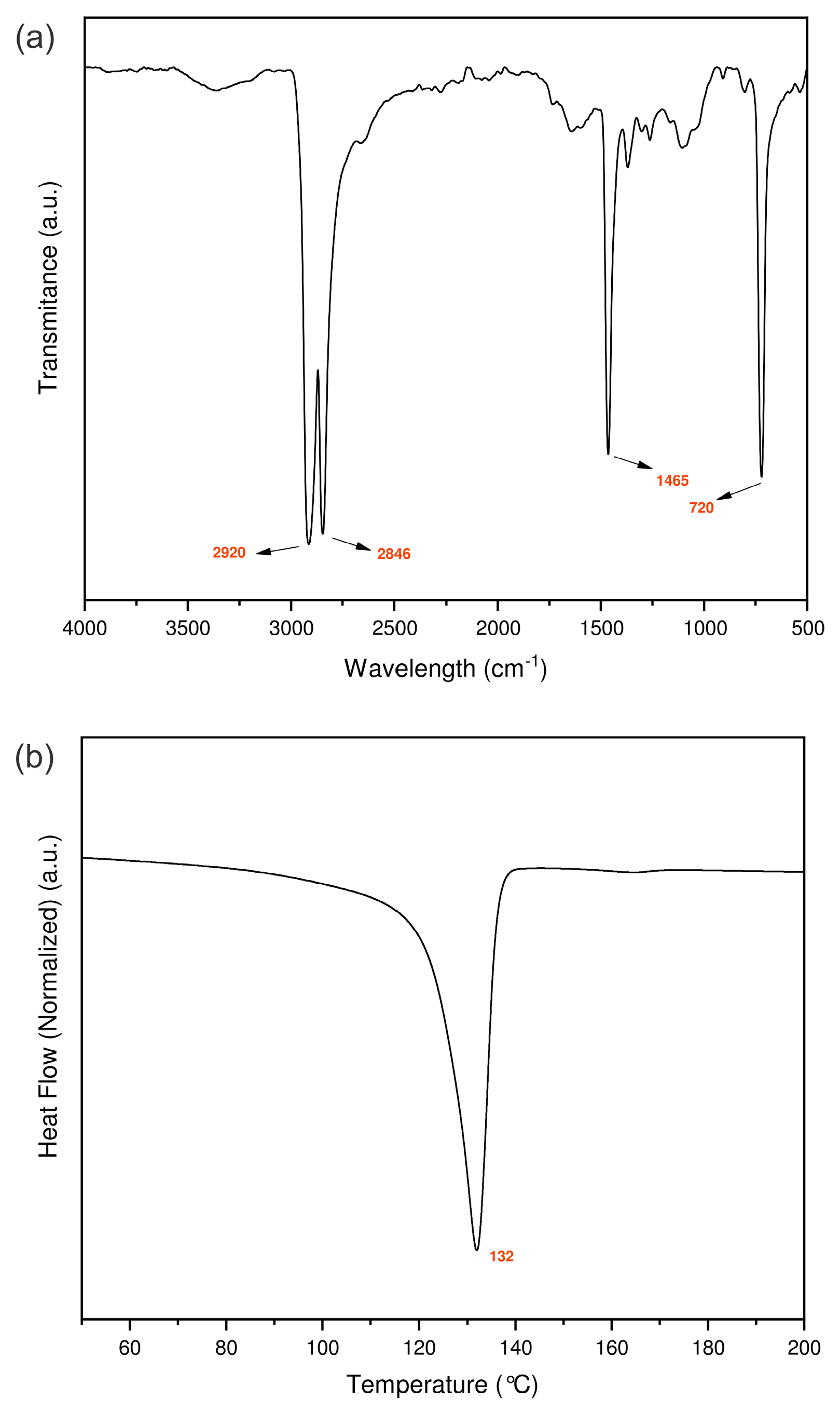

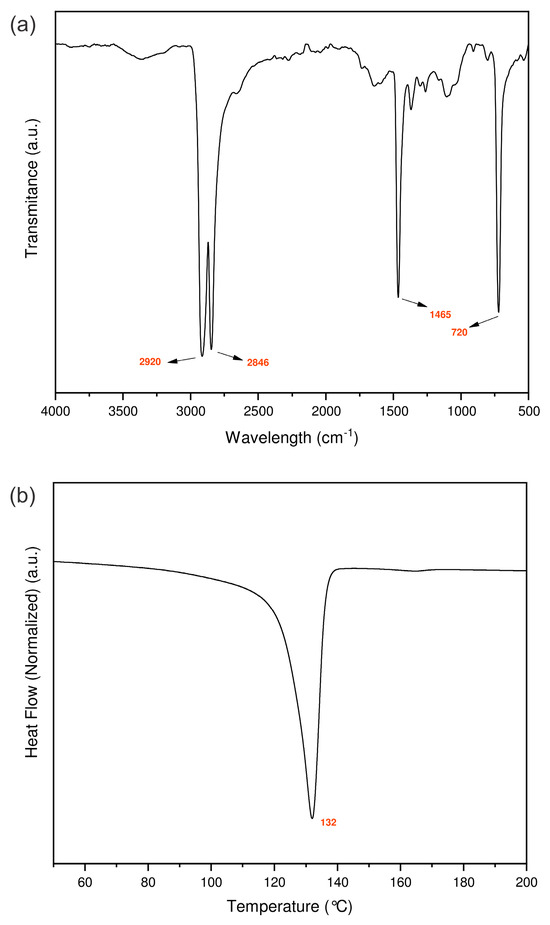

2.3. Chemical Structure and Thermal Properties

ATR-FTIR and DSC were used to analyze the HDPEw and assess its overall chemical composition and crystalline behavior (Figure 5). The FTIR spectrum displays the principal absorption bands characteristic of PE, including the C–H stretching vibrations at approximately 2915 and 2848 cm−1 and the bending and rocking modes at 1470 and 720 cm−1, respectively. These features closely match those observed in fragment 2 of the pre-selected waste samples (Figure 2a), confirming that PE remains as the main polymeric component after extrusion and injection molding. Minor differences in band intensity may be attributed to small fractions of other polymers, as previously identified by FTIR analysis of the individual fragments (Table 1), and to partial oxidation during reprocessing.

Figure 5.

(a) ATR-FTIR spectrum showing the characteristic absorption bands of polyethylene and (b) DSC thermogram displaying the melting behavior of injection-molded specimens produced from recycled HDPEw.

The DSC thermogram of the recycled HDPEw shows a single, well-defined endothermic peak centered at 132 °C, corresponding to the melting of HDPE crystalline lamellae. This temperature aligns with the typical melting range (120–135 °C) of HDPE reported in the literature [37]. The presence of a single melting event suggests that the material is predominantly HDPE, with limited co-crystallization with minor contaminants. The narrow melting peak and absence of additional transitions indicate that the crystalline phase is relatively homogeneous and that no significant miscibility occurred with non-polyolefinic impurities such as polypropylene (PP) or polyethylene terephthalate (PET), which would generally produce secondary peaks or shoulder transitions.

Nevertheless, visual inspection of the injection-molded specimens revealed black inclusions and localized surface irregularities (Figure 4), which evidenced incomplete dispersion of residual impurities or degradation by-products. These defects reflect once again the heterogeneous nature of the recycled feedstock and may act as stress concentrators, negatively affecting mechanical performance and visual appearance. Despite these imperfections, the combination of FTIR and DSC results confirms that the continuous matrix of the recycled material is HDPE and retains its fundamental crystalline structure. However, improving impurity removal and melt homogenization during recycling would be necessary to enhance the structural integrity and reliability of the final product.

2.4. Mechanical Characterization, Rheological Characterization (Melt Flow Rate—MFR), and Density Determination

The mechanical, rheological, and physical properties of the recycled HDPEw are summarized in Table 3. These results provide insight into the combined effects of reprocessing, contamination, and processing optimization on the performance of HDPE derived from mixed polyolefin waste.

Table 3.

Summary of mechanical properties, melt flow rate (MFR), and density measurements obtained for recycled HDPEw after injection molding.

Compared to virgin HDPE, which typically exhibits tensile strengths on the order of 30–40 MPa, tensile modulus between 600 and 1500 MPa, and elongations well above 100%, with densities around 0.94–0.96 g cm−3 [38,39,40], the recycled HDPEw retains a similar tensile strength but exhibits a decrement in the tensile modulus, and a marked loss of ductility. Stiffness is the property associated with the tensile modulus, and its decrease could be related to the immiscibility of phases. Additionally, the reduction in elongation at break reflects the presence of immiscible contaminants and structural heterogeneities detected by FTIR and DSC analyses. Impurities such as PET, PP, and PU introduce rigid domains and interfacial discontinuities that restrict chain mobility, leading to premature crack initiation during tensile deformation. The black inclusions observed in the molded specimens (Figure 4) and the irregular fracture surface in FESEM images (Section 2.5) confirm the presence of such inhomogeneities. These inclusions act as stress concentrators, resulting in a more brittle response typical of recycled polyolefins, which exhibit limited compatibility among their constituent phases [20]. Despite these limitations, the recycled HDPEw maintained satisfactory tensile strength, indicating that the continuous HDPE matrix remains mechanically dominant. The polymer network likely preserves sufficient chain entanglement to transfer stress efficiently through the matrix, even in the presence of impurities. This behavior suggests that the recycling process did not significantly degrade the primary molecular framework of HDPE, although the reduction in elongation confirms partial deterioration of the molecular weight. These findings highlight the critical role of upstream sorting strategies for high-performance applications [41]. However, mechanical performance indicates that HDPEw remains suitable for applications with lower mechanical requirements, rather than being discarded. Applications such as plastic lumber, outdoor profiles, pallets, and other non-structural products represent an interesting, promising, and realistic route for valorization. In these applications, durability, environmental resistance, and cost-effectiveness are often more critical than maximum mechanical performance [42,43,44].

Regarding MFR, its value was approximately 10 g 10 min−1, which supports this interpretation. MFR is inversely correlated with molecular weight; thus, the higher value compared to typical virgin HDPE (usually 2–8 g 10 min−1) [45] implies chain scission during reprocessing or previous life cycles. Such degradation enhances melt flowability, facilitating injection molding but simultaneously diminishing toughness and elongation. The need for back-pressure optimization during processing is consistent with this observation, as degraded or heterogeneous materials often display unstable flow behavior within the screw channel.

The density value of 0.89 g cm−3, which is lower than that of standard HDPE, further indicates compositional variability and the presence of lower-density polyolefins, such as PP. This compositional dilution is consistent with FTIR findings of PP and PP/PET blends within the waste stream. A reduced density generally reflects lower crystallinity and imperfect packing of molecular chains, which, in turn, contribute to decreased stiffness and mechanical uniformity.

The microstructural analysis of cryo-fractured specimens (discussed in the following section) revealed a heterogeneous morphology characterized by dispersed inclusions and microvoids within the HDPE matrix. The lack of smooth fracture surfaces and the presence of interfacial gaps suggest poor adhesion between HDPE and the contaminant phases, confirming the incompatibility among components. These morphological irregularities are directly correlated with the lower ductility and moderate tensile strength observed, as interfacial debonding and void formation are typical failure mechanisms in heterogeneous recycled systems.

The obtained results emphasize the strong influence of impurity type and dispersion on the mechanical behavior of recycled HDPEw. Although optimization of the injection molding parameters, notably reduction of back pressure, improved processability and mold filling, it could not fully compensate for compositional inhomogeneity. The preservation of tensile strength despite reduced ductility demonstrates that mechanical recycling of HDPEw can still achieve suitable materials for less demanding applications [46,47,48]. However, to extend its usability to higher-performance products, additional treatments, such as compatibilization, selective filtration, or reactive extrusion, are recommended to enhance interfacial adhesion and minimize phase segregation.

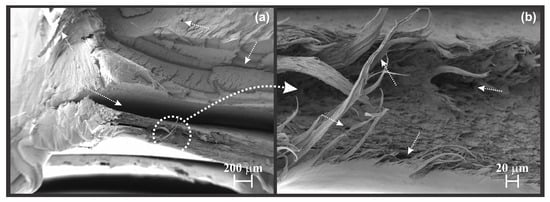

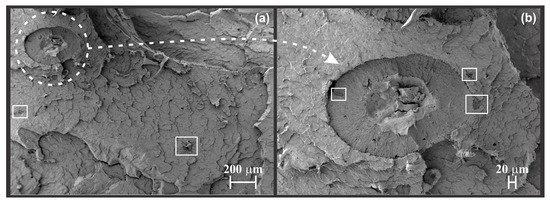

2.5. Microstructure and Morphology

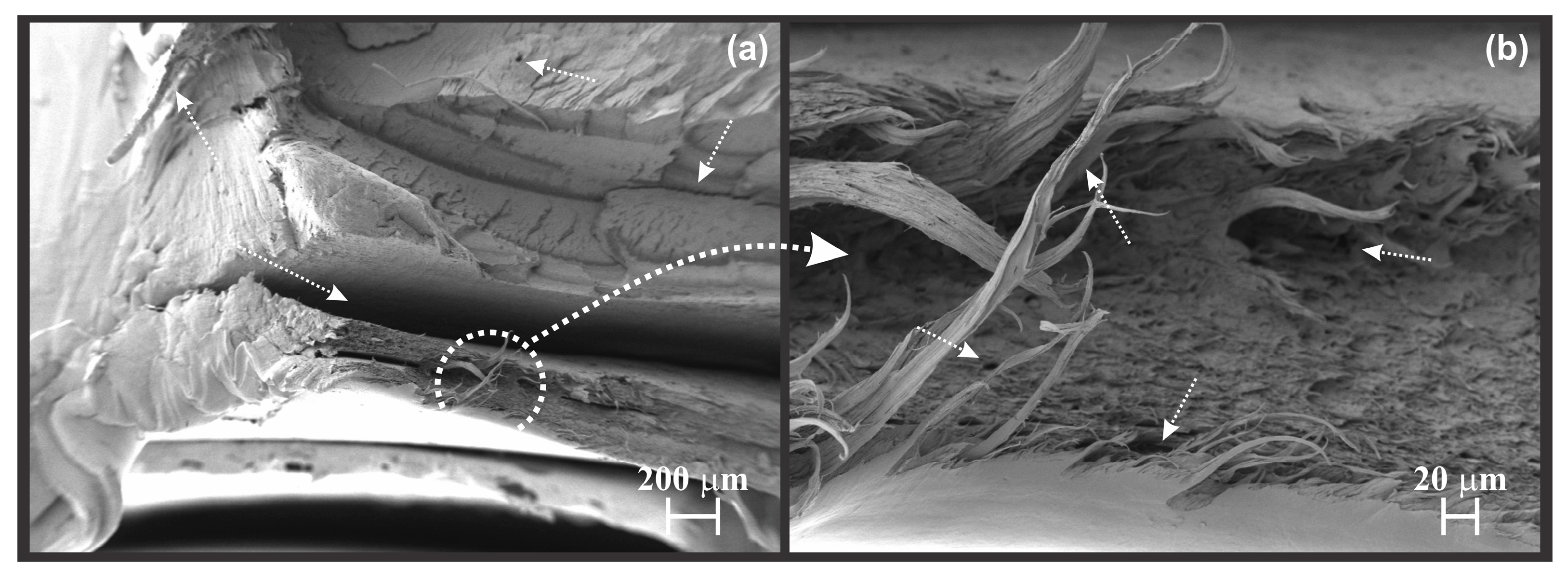

The microstructure of the recycled HDPEw was analyzed by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) to examine fracture surface morphology and correlate structural features with the observed mechanical behavior. Within this regard, Figure 6 shows representative micrographs with arrows indicating fracture surface irregularities, such as phase separation, black dots corresponding to impurities, cracks, stretched phase, among others.

Figure 6.

FESEM images of recycled HDPEw: (a) low-magnification (36×) view showing overall fracture morphology and (b) higher-magnification (256×) view revealing inclusions and surface irregularities associated with impurities. Arrows indicate irregularities such as phase separation, impurities (black dots), and cracks. The dotted circle marks the area magnified in (b).

At low magnification (Figure 6a), the cryo-fractured surface exhibits a heterogeneous texture, consistent with the visual imperfections observed in the molded specimens. Morphological irregularities indicate poor interfacial adhesion and localized, stretched, and deformed surface fragments, consistent with partial phase separation. These facts suggest a lack of miscibility and poor dispersion during processing, despite the use of optimized injection parameters. A small part, indicated with a dotted circle, was magnified (Figure 6b), and the aforementioned facts became more evident. Also, the fracture surface reveals voids and microcracks, consistent with weak interfacial adhesion between HDPE and the contaminant. These interfacial gaps act as stress concentrators, facilitating crack initiation and propagation under tensile load, thereby explaining the reduced elongation at break and moderate tensile strength observed in the mechanical characterization. Similar features have been described for mechanically recycled polyolefins containing incompatible polymer domains, where the lack of miscibility or compatibilization results in less ductile fracture behavior [20,21].

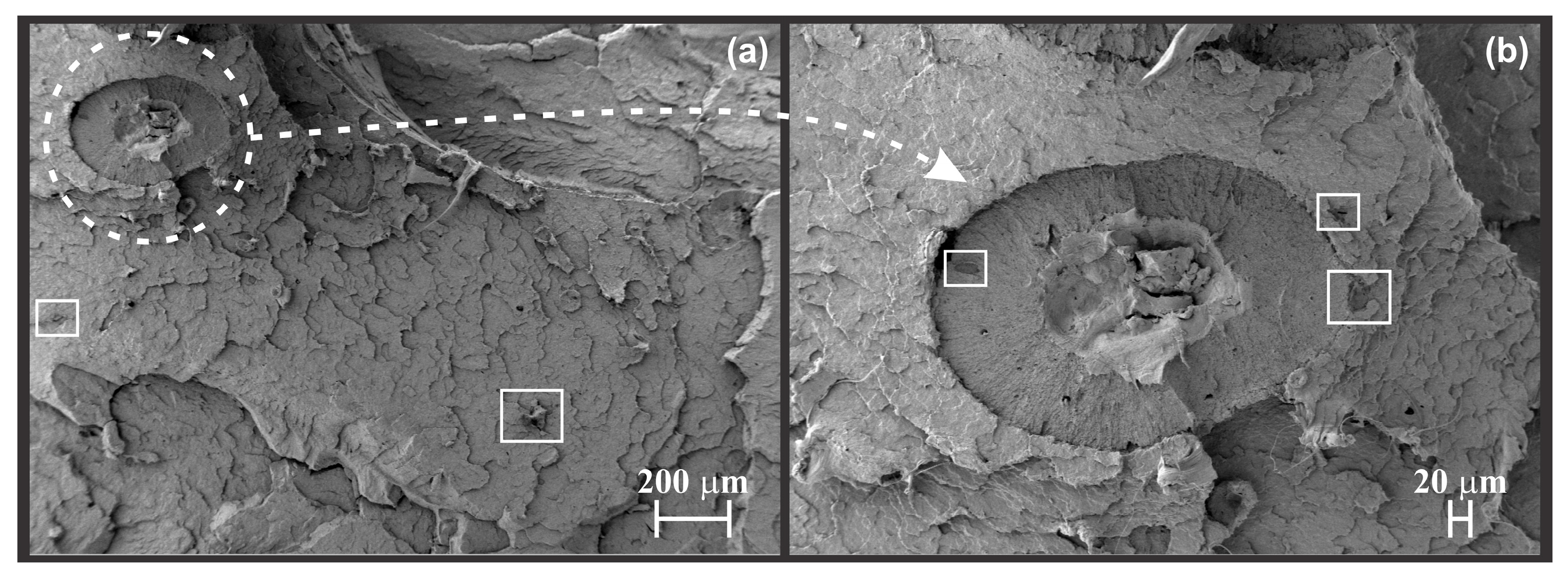

Figure 7 includes FESEM micrographs from another sector of the cryo-fractured surface. These images reveal dispersed inclusions and darker regions, corresponding to impurities or unmelted domains within the HDPE matrix. These inclusions are remnants of non-polyolefinic polymers, such as PET, PP, and PU, previously identified by FTIR and DSC analyses. In particular, a circular domain embedded in the HDPE matrix is indicated by a white dotted circle in Figure 7a and is shown in greater detail in Figure 7b. In this domain, various fractured behaviors attributed to the aforementioned contaminants can be observed. These results also agree with the DSC analysis, since the melting behavior of contaminants is quite different from that of the corresponding HDPE matrix, evidencing a clear unmelted region along the fracture surface [22,49]. Other smaller domains, indicated with a white line square, show the same behavior, corroborating poor interfacial adhesion and, consequently, the observed mechanical behavior.

Figure 7.

FESEM images of recycled HDPEw: (a) low-magnification (55×) view evidencing the presence of unmelted domains and (b) higher-magnification (150×) amplified view of the big domain with more minor inclusions. The white dotted circle in (a) indicates a circular domain with different fracture behavior, magnified in (b). The white square in (a) highlights smaller domains showing poor interfacial adhesion.

The overall morphology indicates that the recycled HDPEw maintains a continuous HDPE phase but incorporates dispersed secondary phases of lower compatibility. The limited interfacial bonding between these phases prevents effective stress transfer across the matrix and promotes localized failure mechanisms. Furthermore, the presence of microvoids and irregular particle boundaries indicates incomplete melting or insufficient shear mixing during extrusion, both of which are typical consequences of heterogeneous feedstock composition.

In summary, the FESEM observations corroborate mechanical and rheological results: while the HDPE matrix retains its primary structure, impurities and immiscible components introduce microstructural discontinuities that compromise final performance in general and ductility in particular. These findings underscore the importance of enhancing feedstock purity and investigating compatibilization or reactive extrusion strategies to achieve improved phase dispersion and interfacial integrity in recycled HDPE products.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Ecoembes supplied high-density polyethylene waste (HDPEw) used in this study. The material came from rigid packaging sources and was delivered in shredded form.

3.2. Sample Preparation

To obtain a representative portion of the mixed polyolefin waste, a quartering procedure was applied to a 25 kg batch of HDPEw. This methodology was employed to ensure statistical representativeness, accounting for the heterogeneity of post-consumer polyolefin waste in terms of particle size, color, and polymer composition. The material was first thoroughly mixed on a flat surface, then spread into a square layer and divided into four equal sections. Two opposite sections were discarded, and the remaining material was remixed. This process was repeated iteratively until the desired sample size was reached. A final 0.5 kg subsample was collected, providing sufficient material for subsequent extrusion, injection molding, and physicochemical characterization, while remaining suitable for laboratory-scale processing.

3.3. Processing

The HDPEw sample was dried in a ventilated oven at 40 °C for 12 h prior to processing. This drying temperature was selected to minimize thermal oxidation, which can begin at 50 °C or even under ambient conditions when exposed to light. After drying, the material was processed in a co-rotating twin-screw extruder (L/D = 24) from Dupra S.L. (Alicante, Spain), equipped with a 3.6 mm die. The extrusion was carried out with a temperature profile of 180–190–200 °C from the feed zone to the die. The screw rotational speed was set to 100 rpm and maintained throughout processing to ensure reproducible conditions. Material feeding was performed manually, and therefore, the mass flow rate was not gravimetrically controlled. The extruder was equipped with two co-rotating screws with simple, non-configured geometry, without kneading or mixing elements. The extrudate was subsequently cooled and ground into flakes with an approximate size of 4 mm per side for further molding. The reprocessed HDPEw was then shaped into standardized test specimens via injection molding using a Sprinter 11 machine from Erinca S.L. (Barcelona, Spain), equipped with a screw diameter of 18 mm and a nozzle diameter of 4 mm. Dog-bone–shaped tensile specimens of type 1BA (80 × 10 × 4 mm) were produced in accordance with ISO 527-2 for mechanical testing [50]. The injection unit is divided into three heating zones: T1 (hopper), T2, and T3 (nozzle). Accordingly, the temperature profile was set to 190–195–200 °C from hopper to nozzle. The injection process was carried out with a screw speed of 45% and an injection speed of 65%, selected to ensure proper mold filling and minimize material stress during molding. The injection time was set to 3.5 s, and the mold temperature was maintained at 20 °C throughout all experiments. Injection molding parameters (e.g., injection speed, screw speed, back pressure, and holding pressure) are reported as percentages of the maximum settings of the laboratory-scale injection molding machine, as the system does not provide absolute values for these parameters. In contrast, mold and barrel temperatures are reported in absolute units.

To ensure reproducibility and statistical consistency, four injection molding experiments (Experiments 1–4) were conducted under distinct parameter settings, as illustrated in Figure 3. For each condition, at least 5 specimens were molded and evaluated. The reported processing parameters and resulting sample characteristics represent average values obtained from these replicates. In cases where quantitative measurements were derived (e.g., melt flow rate, density, and mechanical tests), results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, based on at least three consistent measurements per condition. The relatively low dispersion of results confirms good repeatability under the optimized processing conditions.

3.4. Chemical and Thermal Characterization

Chemical and Thermal Characterization was conducted on the distinct HDPEw fragments identified in the initial waste stream and the standardized test specimens obtained after reprocessing. This dual-stage analysis enables evaluation of changes in material composition and structure resulting from processing. Chemical characterization was carried out using Attenuated Total Reflectance–Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR–FTIR) with a PerkinElmer Spectrum BX spectrometer. Spectra were collected at a resolution of 4 cm−1 over 4000–450 cm−1, with 16 scans per sample to enhance signal quality. All fragments and processed specimens were analyzed under identical conditions to enable direct comparison.

Thermal behavior was analyzed by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) using a Discovery Series DSC 25 instrument (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). Before testing, samples were dried to eliminate moisture interference. Analyses were conducted in hermetically sealed aluminum pans under a nitrogen atmosphere (flow rate: 50 mL/min) to prevent oxidative degradation. The thermal protocol consisted of a first heating scan from 0 to 280 °C to remove any previous thermal history, followed by a cooling step to 0 °C and a second heating cycle up to 280 °C. A constant heating/cooling rate of 10 °C/min was applied. The second heating scan was used to determine key thermal transitions, such as melting and glass transition temperatures.

3.5. Mechanical Characterization, Rheological Characterization (Melt Flow Rate—MFR) and Density Assessment

Tensile tests were performed at room temperature using a universal test machine, Duotrac-10/1200 from Iberest (Madrid, Spain), according to ISO 527-1 [51], at a crosshead rate of 10 mm/min and a 10 kN load cell. The injected molded specimens were placed between the clamps with an initial gap of 50 mm. Five specimens of recycled material were tested, and the corresponding tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and elongation at break were determined, according to ISO 527-1.

Melt flow rate (MFR) was assessed according to ISO 1133-1 [52] at 230 °C under a 5.00 kg load using a plastometer from Metrotec–ATSFAAR S.p.A. (Vignate, Italy). These conditions were selected because the recycled HDPEw has a heterogeneous composition, including minor polypropylene fractions. Approximately 6–8 g of material was introduced into the preheated barrel and allowed to equilibrate for 1 min before testing. The extrudate was collected at 30 s intervals, and each segment was weighed. MFR was calculated as shown in Equation (1)

where m is the mass of the extrudate (g), and t is the extrusion time (s). Reported values are the average of at least 3 consistent measurements.

Density was determined at 23.5 °C by the hydrostatic weighing method according to ISO 1183 [53], using a Sartorius Cubis® analytical balance equipped with a density determination kit (YDK04MS, Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany). Individual flakes (obtained by shredding extruded HDPEw) were weighed in air () and then immersed in deionized water at 23.5 °C (). To avoid air entrapment, samples were gently agitated until no bubbles were observed. Density () was calculated using Archimedes’ principle as shown in Equation (2)

where is the density of water at 23.5 °C (0.9975 g cm−3). Reported values correspond to the mean of ten measurements.

3.6. Microstructural Characterization

Morphology of cryo-fractured surfaces was analyzed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) using a ZEISS ULTRA55 microscope (Abingdon, UK). Before analysis, samples were metallized to enable electrical conduction with a gold-palladium alloy using an EMITECH sputter coater. SC7620 Quorum Technologies Ltd. (Lewes, UK). Samples were analyzed at an accelerating voltage of 2 kV.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the strong influence of impurities on the processability and final performance of recycled high-density polyethylene waste (HDPEw) obtained from mixed polyolefin streams. Analytical results confirmed HDPE as the main polymer, containing minor fractions of polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and polyurethane (PU) detected as contaminants.

The recycled HDPEw exhibited a tensile strength of 38.7 ± 1.7 MPa, elongation at break of 34.8 ± 5.7%, density of 0.89 ± 0.08 g cm−3, and melt flow rate (MFR) of 9.9 ± 0.6 g 10 min−1. Compared with typical virgin HDPE, the recycled material maintained similar strength but showed markedly lower ductility and density. This reduced density is attributed to lower-density polyolefin fractions (primarily PP) and to microvoids resulting from interfacial incompatibility. Simultaneously, the elevated MFR reflects the combined effects of contamination and partial molecular degradation.

Regarding processability, optimizing injection-molding parameters was critical. Specifically, progressively reducing back pressure proved to be an effective strategy to stabilize melt flow and improve mold filling consistency, thereby mitigating processing instabilities caused by material heterogeneity. These results highlight that adapting conventional processing parameters, rather than relying on standard virgin settings, enables the use of heterogeneous recycled streams under realistic industrial conditions.

While the results confirm that recyclate quality depends strongly on waste-stream purity—underscoring the need for improved design-for-recycling and sorting—this study shows that mixed HDPEw should not be discarded. Instead, it can be valorized as a secondary raw material for applications with lower mechanical requirements. Non-structural products such as plastic lumber, outdoor profiles, and pallets represent realistic valorization routes. For these applications, matching the mechanical properties of virgin HDPE is less critical than ensuring processability, durability, and cost-effectiveness. This approach supports a practical and sustainable solution to reduce plastic waste accumulation through mechanical recycling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization M.D.S. and Y.V.V.; methodology, Y.V.V. and J.V.M.G.; validation, C.P.; formal analysis, C.P. and Y.V.V.; investigation, Y.V.V. and J.V.M.G.; resources, M.D.S. and J.L.-M.; data curation, Y.V.V.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.V.V.; writing—review and editing, C.P.; visualization, M.D.S.; supervision, M.D.S.; project administration, J.L.-M.; funding acquisition, M.D.S. and J.L.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union “NextGenerationEU”/PRTR through the grant PID2023-152869OB-C22 and PID2024-157368NB-C33, and by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 through the TED-AEI Project (grant TED2021-129920A-C43) and “ERDF A way of making Europe”.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Cristina Pavon thanks Universitat Politécnica de València for her post-doctoral PAID-10–23 grant. Yamila V. Vazquez thanks Juan López-Martínez and Samper Madrigal for the opportunity to carry out a research stay at the Instituto Universitario de Investigación y Tecnología de Materiales of Universitat Politécnica de València.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HDPE | High-density polyethylene |

| HDPEw | High-density polyethylene waste |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PU | Polyurethane |

| ATR-FTIR | Attenuated total reflectance–Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| FESEM | Field emission scanning electron microscopy |

| MFR | Melt flow rate |

| Tg | Glass transition temperature |

| Tm | Melting temperature |

| C=O | Carbonyl group |

| CH2 | Methylene group |

| CH3 | Methyl group |

References

- Landuzzi, A.; Ghosh, J. Improving Functionality of Polyolefin Films Through the Use of Additives. J. Plast. Film Sheeting 2003, 19, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Zhu, H. The Key to Solving Plastic Packaging Wastes: Design for Recycling and Recycling Technology. Polymers 2023, 15, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Wang, H.; Meng, F.; Chen, S.; Du, B.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, K.; Gao, H.; Pan, L.; et al. Upcycling of Polyethylene/Polypropylene Mixtures Promoted by Well-Controlled Multiblock Olefin Copolymers. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 155003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Edman Tsang, S.C. Recent Advances in Polyolefin Plastic Waste Upcycling via Mild Heterogeneous Catalysis Route from Catalyst Development to Process Design. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 102075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xiang, X.; Qu, P.; Zhu, M. Recent Developments in Recycling of Post-Consumer Polyethylene Waste. Green. Chem. 2025, 27, 4040–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messiha, M.; Geier, J.; Barretta, C.; Bredács, M.; Oreski, G.; Kratochvilla, T.; Hruszka, P.; Arbeiter, F.; Pinter, G. How Impurities Affect the Lifetime of Plastic Products—A Circularity Case Study on Polymer Pipes. Polym. Test. 2025, 151, 108952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L.; Rajapakse, N.; Andrady, A.L.; Rajapakse, N.; Takada, H.; Karapanagioti, H.K. Additives and Chemicals in Plastics. In Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 78, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeisinger, C. Material Recycling of Post-Consumer Polyolefin Bulk Plastics: Influences on Waste Sorting and Treatment Processes in Consideration of Product Qualities Achievable. Waste Manag. Res. 2017, 35, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, K.; Kaseem, M.; Deri, F. Recycling of Waste from Polymer Materials: An Overview of the Recent Works. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2013, 98, 2801–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G Schyns, Z.O.; Shaver, M.P.; G Schyns, Z.O.; Shaver, M.P. Mechanical Recycling of Packaging Plastics: A Review. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2021, 42, 2000415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipp, A.M.; Blasenbauer, D.; Stipanovic, H.; Koinig, G.; Tischberger-Aldrian, A.; Lederer, J. Technical Evaluation and Recycling Potential of Polyolefin and Paper Separation in Mixed Waste Material Recovery Facilities. Recycling 2025, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distaso, M. Potential Contribution of Nanotechnology to the Circular Economy of Plastic Materials. Acta Innov. 2020, 37, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidakis, N.; Petousis, M.; Maniadi, A. Sustainable Additive Manufacturing: Mechanical Response of High-Density Polyethylene over Multiple Recycling Processes. Recycling 2021, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Murphy, R.J.; Narayan, R.; Davies, G.B.H. Biodegradable and Compostable Alternatives to Conventional Plastics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2127–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.; Mattos, G.; Sitton, N.; Barros, J.; Miranda, D.; Luciano, R.; Pinto, J.C.; Carvalho, L.; Mattos, G.; Sitton, N.; et al. A Survey on the Chemical Recycling of Polyolefins into Monomers. Processes 2025, 13, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boz Noyan, E.C.; Boldizar, A. Blow Molding of Mechanically Recycled Post-Consumer Rigid Polyethylene Packaging Waste. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2024, 64, 5968–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.F.; Zhang, H.R.; Li, Z.K.; Hu, C.Y.; Wang, Z.W. Effect of Mechanical Recycling on Crystallization, Mechanical, and Rheological Properties of Recycled High-Density Polyethylene and Reinforcement Based on Virgin High-Density Polyethylene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaagac, E.; Koch, T.; Archodoulaki, V.M. The Effect of PP Contamination in Recycled High-Density Polyethylene (RPE-HD) from Post-Consumer Bottle Waste and Their Compatibilization with Olefin Block Copolymer (OBC). Waste Manag. 2021, 119, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, L.P.; Koch, T.; Krempl, N.; Archodoulaki, V.M. Rethinking PE-HD Bottle Recycling—Impacts of Reducing Design Variety. Recycling 2025, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, M.; Freudenthaler, P.J.; Fischer, J.; Lang, R.W. Characterization of Composition and Structure–Property Relationships of Commercial Post-Consumer Polyethylene and Polypropylene Recyclates. Polymers 2021, 13, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, M.; Berghofer, M.; Fischer, J.; Mager, M.; Berghofer, M.; Fischer, J. Polyolefin Recyclates for Rigid Packaging Applications: The Influence of Input Stream Composition on Recyclate Quality. Polymers 2023, 15, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnoffo, C.; Arrigo, R.; Frache, A. Mechanical Recycling of HDPE-Based Packaging: Interplay between Cross Contamination, Aging and Reprocessing. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 236, 111290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zięba-Palus, J. The Usefulness of Infrared Spectroscopy in Examinations of Adhesive Tapes for Forensic Purposes. Forensic. Sci. Criminol. 2017, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, D.J.; Wiebeck, H. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Combined with Chemometric Methods for the Classification of Polyethylene Residues Containing Different Contaminants. J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 30, 3031–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecozzi, M.; Nisini, L. The Differentiation of Biodegradable and Non-Biodegradable Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Samples by FTIR Spectroscopy: A Potential Support for the Structural Differentiation of PET in Environmental Analysis. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2019, 101, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Huang, W.M.; Li, C.; Chor, J.H. Effects of Moisture on the Glass Transition Temperature of Polyurethane Shape Memory Polymer Filled with Nano-Carbon Powder. Eur. Polym. J. 2005, 41, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šudomová, L.; Doležalová Weissmannová, H.; Steinmetz, Z.; Řezáčová, V.; Kučerík, J. A Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Approach for Assessing the Quality of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Waste for Physical Recycling: A Proof-of-Concept Study. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2023, 148, 10843–10855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellati, A.; Boufassa, S. Evaluation of the Role of Ethylene Vinyl Acetate on the Thermo-Mechanical Properties of PET/HDPE Blends. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2022, 12, 9546–9550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, S.; Islam, M.R.; Wasiuddin, N.M.; Peters, A. A Thermodynamic Approach to Investigate Compatibility of HDPE, LDPE, and PP Modified Asphalt Binders Using Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 476, 140904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei Lun Lee, A.; Ying Chung, S.; Shee Tan, Y.; Mun Ho Koh, S.; Feng Lu, W.; Sze Choong Low, J. Enhancing the Environmental Sustainability of Product through Ecodesign: A Systematic Review. J. Eng. Des. 2023, 34, 814–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.D.; Schyns, Z.O.G.; Franklin, T.W.; Shaver, M.P. Defining Quality by Quantifying Degradation in the Mechanical Recycling of Polyethylene. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, P.; Kleinsorge, J.; Hopmann, C. Influence of the Recyclate Content on the Process Stability and Part Quality of Injection Moulded Post-Consumer Polyolefins. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2025, 2025, 7570978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman Jan, Q.M.; Habib, T.; Noor, S.; Abas, M.; Azim, S.; Yaseen, Q.M. Multi Response Optimization of Injection Moulding Process Parameters of Polystyrene and Polypropylene to Minimize Surface Roughness and Shrinkage’s Using Integrated Approach of S/N Ratio and Composite Desirability Function. Cogent Eng. 2020, 7, 1781424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, A. Injection Moulding: The Role of Back-Pressure | Prospector. Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/knowledge/7804/pe-injection-moulding-backpressure/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Jmerson, L. Holding Pressure and Holding Time In Injection Molding. Available online: https://firstmold.com/guides/holding-pressure-and-holding-time/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Hansen Plastics Corporation How to Control Shrinkage During Injection Molding. Available online: https://www.hansenplastics.com/how-to-control-shrinkage-during-injection-molding/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Harland, W.G.; Khadr, M.M.; Peters, R.H. High-Density Polyethylene: Thermal History and Melting Characteristics. Polymers 1972, 13, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeen, L.W. Introduction to Use of Plastics in Food Packaging. In Plastic Films in Food Packaging: Materials, Technology and Applications; William Andrew Publishing/Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 1–15. ISBN 9781455731121. [Google Scholar]

- Vasile, C.; Pascu, M. Practical Guide to Polyethylene; Rapra Technology: Shrewsbury, UK, 2005; pp. 107, 128, 323–326, 385–387. ISBN 978-1-85957-493-5. [Google Scholar]

- Amjadi, M.; Fatemi, A. Tensile Behavior of High-Density Polyethylene Including the Effects of Processing Technique, Thickness, Temperature, and Strain Rate. Polymers 2020, 12, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiedler, A.M. Practicality of Single-Stream Recycling of High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) in the United States. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cecon, V.S.; Pham, T.; Curtzwiler, G.; Vorst, K. Assessment of Different Application Grades of Post-Consumer Recycled (PCR) Polyolefins from Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) in the United States. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 13065–13076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.J.; Ali, M.; Das, A.J.; Ali, M. Prospective Use and Assessment of Recycled Plastic in Construction Industry. Recycling 2025, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceolin, V.N.; Gomes, M.I.; Oliveira, F.; Louro, M. Application of Recycled High-Density Polyethylene for Construction of Non-Structural Wattle and Daub Walls. Interactions 2025, 246, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathner, R.; Roland, W.; Albrecht, H.; Ruemer, F.; Miethlinger, J. Applicability of the Cox-Merz Rule to High-Density Polyethylene Materials with Various Molecular Masses. Polymers 2021, 13, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanian-Moghaddam, D.; Asghari, N.; Ahmadi, M. Circular Polyolefins: Advances toward a Sustainable Future. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 5679–5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basalp, D.; Tihminlioglu, F.; Sofuoglu, S.C.; Inal, F.; Sofuoglu, A. Utilization of Municipal Plastic and Wood Waste in Industrial Manufacturing of Wood Plastic Composites. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2020, 11, 5419–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, R.; Domínguez, C.; Robledo, N.; Paredes, B.; García-Muñoz, R.A. Incorporation of Recycled High-Density Polyethylene to Polyethylene Pipe Grade Resins to Increase Close-Loop Recycling and Underpin the Circular Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Xie, X.M.; Guo, B.H. Compatibilization and Morphology Development of Immiscible Ternary Polymer Blends. Polymer 2011, 52, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNE-EN ISO 527-2:2012; Determinación de Las Propiedades En Tracción. Parte 2: Condiciones de Ensayo Para Plásticos de Moldeo y Extrusión. Asociación Española de Normalización (UNE): Madrid, Spain, 2012.

- UNE-EN ISO 527-1:2012; Determinación de Las Propiedades En Tracción. Parte 1: Condiciones de Ensayo Para Plásticos de Moldeo y Extrusión. Asociación Española de Normalización (UNE): Madrid, Spain, 2012.

- UNE-EN ISO 1133-1:2013; Determinación Del Índice de Fluidez de Masa (MFR) y Del Índice de Fluidez de Volumen (MVR) de Termoplásticos. Parte 1: Método Normalizado. Asociación Española de Normalización (UNE): Madrid, Spain, 2013.

- UNE-EN ISO 1183-1:2019; Métodos Para Determinar La Densidad de Plásticos No Celulares. Parte 1: Método de Inmersión, Método Del Picnómetro Líquido y Método de Valoración. Asociación Española de Normalización (UNE): Madrid, Spain, 2019.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.