Abstract

Innovations in manual waste sorting have stagnated for decades, despite the increasing global demand for efficient recycling solutions. The recAIcle system introduces an innovative AI-powered assistance system designed to modernise manual waste sorting processes. By integrating machine learning, continual learning, and projection-based augmentation, the system supports sorting workers by highlighting relevant waste objects on the conveyor belt in real time. The system learns from the decision-making patterns of experienced sorting workers, enabling it to adapt to operational realities and improve classification accuracy over time. Various hardware and software configurations were tested with and without active tracking and continual learning capabilities to ensure scalability and adaptability. The system was validated in initial trials, demonstrating its ability to detect and classify waste objects and providing augmented support for sorting workers with high precision under realistic recycling conditions. A survey complemented the trials and assessed industry interest in AI-based assistance systems. Survey results indicated that 82% of participating companies expressed interest in supporting their staff in manual sorting by using AI-based technologies. The recAIcle system represents a significant step toward digitising manual waste sorting, offering a scalable and sustainable solution for the recycling industry.

1. Introduction

Waste sorting is the first and most important step towards subsequent recycling and is a fundamental part of the circular economy [1]. Even in the 21st century, manual sorting of waste is essential. There are two fundamental possibilities for sorting waste: sensor-based sorting (SBS) and manual sorting. Manual sorting plays a central role in facilities with a low degree of automation, while in highly automated facilities, it is primarily used for post-sorting and high-quality assurance tasks [2]. The main aim of manual sorting is to improve the quality of the preprocessed material, to sort unwanted material or impurities from the automatic sorting systems and to remove contaminants. For small sorting plants, manual sorting represents a cost-effective, flexible alternative to investment-intensive automatic sorting equipment. State-of-the-art SBS plays a major role in waste separation. Multiple kinds of sensors can be used. SBS-technologies separate materials into distinct fractions by detecting their unique material signatures. A wide range of sensors and detection methods are employed, including induction and eddy current systems, hyperspectral imaging, laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS), and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) [3]. Among these, near-infrared (NIR) hyperspectral imaging is the most widely applied approach for plastic identification and classification. Once the material type is determined, mechanical actuators, such as pneumatic ejectors or robotic manipulators, execute the sorting decision [4]. Despite their clear advantages, including reduced labour demand, improved process efficiency, and enhanced operational safety, SBS systems also entail considerable capital investments and maintenance costs and are unsuitable for some material streams [5]. Recent advances in artificial-intelligence-driven waste sorting enable systems to classify and divert materials such as plastics, metals, paper, and glass in real time using computer vision and machine learning algorithms, thereby improving the purity of recyclate streams and enhancing operational efficiency [6]. However, these artificial intelligence (AI)-based systems often share similar limitations with conventional SBS technologies, particularly due to the mechanical constraints and response times of the actuators involved.

Despite its necessity, manual sorting is only mentioned to a limited extent in the literature, even though it will remain an indispensable part of many processing and recycling plants in the coming years. Remarkably, the fundamental process of manual sorting has remained largely unchanged over the last century. The competence of employees significantly influences the quality of the output stream. At a belt speed of 0.1 to 0.2 m/s, staff must identify materials to be sorted based on visual and tactile characteristics and make a sorting decision based on these within fractions of a second [2]. At a belt speed of 0.1 m/s, one person performs an average of 30 grip movements per minute, while at a belt speed of 0.2 m/s, this figure rises to around 50 movements per minute. This grip rate corresponds to 1800 to 3000 picks per hour [7]. However, it is important to note that these values can vary significantly depending on the type of material being sorted and the degree of belt occupancy. For example, Fotovvatikhah et al. (2025) conducted a systematic review and reported that manual sorters typically process around 30–40 items per minute, which aligns with the lower end of the observed range [8]. These findings highlight the strong dependency of sorting rates on material type, belt speed, and line configuration.

Manual sorting in sorting cabins remains a “black box” offering significant potential for innovation. Digitalisation is already transforming various areas of waste management and is emerging as a key priority in the sector [9]. In order to digitalise a complex process such as waste sorting, every sub-step must be digitised. Integrating new technologies into the manual sorting process is essential for modernising manual waste sorting. Machine learning (ML) and AI have already demonstrated several times how they can revolutionise entire industries [10]. As a cornerstone of digital transformation, AI encompasses technologies and systems capable of solving complex tasks that previously required human intelligence [11].

The project “Recycling-oriented collaborative waste sorting by continual learning” (recAIcle), funded by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG), addresses the pressing need to enhance the manual sorting of non-hazardous waste through digitalisation and advanced technologies. The recAIcle system represents the first system in the waste management sector that learns directly from human sorting workers and is supported by a human–machine interface (HMI). This novel approach combines human expertise with machine intelligence, enabling the system to passively observe and learn from sorting decisions made by experienced workers. Additionally, the system integrates several advanced research concepts, such as learning from observation, data augmentation, and homography, which are being applied in the waste management sector for the first time. All of this is implemented on industrial-grade hardware, ensuring the system’s reliability and availability in real-world operational environments.

Manual sorting remains labour-intensive, with significant variations in procedures between facilities. This lack of standardisation and transparency hinders innovation, as a clear understanding of industry-specific requirements is crucial for developing and implementing new technologies. To address this challenge, a market study was conducted to identify stakeholders, gather their perspectives on relevant design options, and define potential technical and operational constraints.

This paper goes beyond the initial market analysis, building on the use cases and requirements outlined in Aberger et al. [12]. While the first publication mainly focused on identifying use cases and design requirements and exploring existing datasets, the present work concentrates on addressing open challenges in the development of an assistance system for manual waste sorting.

Based on the findings, an assistance system is developed to support sorting employees through the integration of AI, ML, and projector-based augmentation technologies. The system takes a novel approach by fostering collaboration between human expertise and machine intelligence. By passively learning from experienced sorting workers and observing their decisions, AI adapts its classification strategies to real-world sorting practices. In turn, the system supports workers by projecting targeted visual cues, implemented as light pulses, onto relevant waste objects, assisting them in their decision-making process.

Therefore, this paper focuses on the system’s hardware configuration, software pipeline, deployment options, how the system learns from employees and incorporates continual learning, and projection-based augmentation, its validation, and scalability.

2. Results

The following section presents the key findings of this study, structured to provide a comprehensive overview of the results. Each subsection focuses on a specific aspect of the research, including the outcomes of the market survey, the different hard- and software configurations, learning from observation, performance evaluation of the recAIcle augmentation system, and its scalability in real-world applications.

2.1. Market Survey

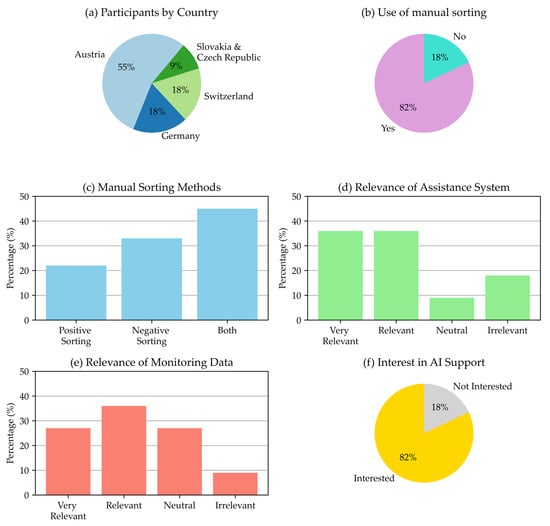

The survey was open for participation in the DACH region (Germany (D), Austria (A), and Switzerland (CH)) from 18 June 2024 to 12 July 2024 inclusive. A total of 41 companies were invited to participate, of which three declined due to internal restrictions. Eleven companies completed the questionnaire, representing a response rate of 27%. Among the companies that participated in the survey,

- 55% were based in Austria,

- 18% in Germany,

- 18% in Switzerland and

- 9% in Slovakia and the Czech Republic.

The companies were asked if they use manual sorting in their process and how they implement it. Nine out of the eleven participating companies confirmed using manual sorting.

- 22% of these companies employ positive sorting to extract desired fractions,

- 33% use negative sorting to remove impurities, and

- 45% combine both positive and negative sorting for the aforementioned purposes as well as for quality assurance.

The participants were asked how relevant an assistance system for supporting sorting workers would be to them. This question was framed in the context of the capabilities of the recAIcle assistance system, aiming to assess its perceived business value. Respondents were asked to rate their answers on a scale from 1 (very relevant) to 5 (not relevant). The results were as follows:

- 36% of respondents considered the system to be very relevant,

- 36% considered the system to be a relevant endeavour,

- 9% were neutral about it, and

- 18% considered it to be irrelevant.

Subsequently, participants were asked about the potential relevance of collecting monitoring data (e.g., input and output streams from manual sorting) using the recAIcle system. The respondents had the opportunity to rate the project on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (very relevant) to 5 (not relevant). The option of collecting monitoring data using the recAIcle system was considered

- 27% of respondents found it to be very relevant,

- 36% to be relevant,

- 27% to be neither relevant nor irrelevant, and

- 9% to be irrelevant.

Finally, the participants were asked if they were interested in supporting their sorting workers with AI, like the recAIcle assistance system. Overall, 82% of the companies surveyed can imagine supporting their staff in manual sorting by using AI-based technologies.

The survey results were visualised in a series of diagrams in Figure 1 to provide a clear overview of participants’ distribution, manual sorting use, the relevance of an assistance system, and the interest in AI-supported technologies.

Figure 1.

Overview of the survey results. The diagrams illustrate (a) the geographical distribution of participating companies, (b) the use of manual sorting, (c) the methods of manual sorting, (d) the relevance of an assistance system, (e) the relevance of monitoring data streams, (f) the interest in AI-supported technologies.

2.2. Hardware and Software Configurations

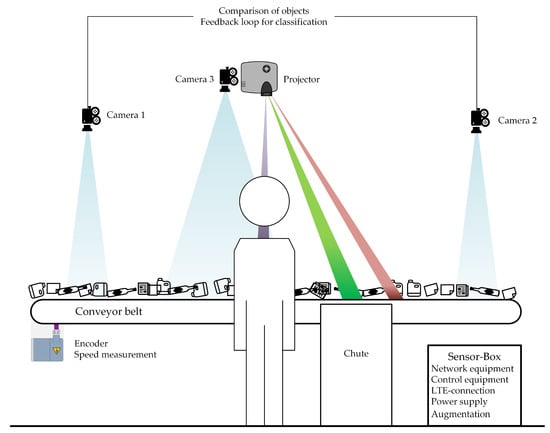

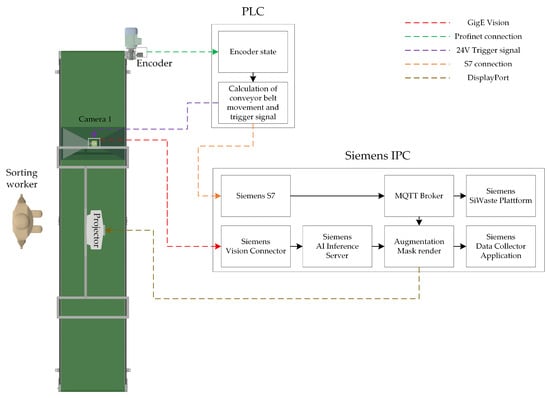

The concept of the recAIcle prototype is shown in Figure 2. All components used in the prototype are industrial-grade, high-availability parts. Networking was implemented using switches from the Siemens Scalance XC100 (Siemens AG, Munich, Germany) series. A Siemens Scalance W700 WiFi router (Siemens AG, Munich, Germany) was deployed for shopfloor access, and a Siemens Scalance M876-4 4 G router (Siemens AG, Munich, Germany) was used for remote and cloud access. The prototype was set up for testing and verification experiments in the Digital Waste Research Lab (DWRL) of the Chair of Waste Utilisation Technology and Waste Management (AVAW) at the Technical University of Leoben in St. Michael. This facility serves as a testing ground for evaluating and further developing the system. The DWRL is an innovative, modular test facility for large-scale tests and digital waste analysis. It includes several conveyor systems and sensors, enabling the sorting and characterisation of various bulk materials [13].

Figure 2.

Conceptual design of the recAIcle prototype.

The recAIcle assistance system consists of a camera system, an augmentation system and a mobile sensor box that contains all relevant information processing systems. This modular design ensures flexibility and adaptability to various operational needs. These components can be considered the foundational building blocks for a sorting station and are designed to be scalable. With relatively minimal effort, the system can be extended to additional sorting stations by adding more cameras and projectors, and potentially increasing computing power as needed. The camera system includes three 5 MP Basler ace2pro (Basler AG, Ahrensburg, Germany) industrial cameras paired with Tamron M117FM06-RG 6 mm f2.4 lenses (Tamron Co., Ltd., Saitama, Japan), which are connected to the Industrial PC (IPC) and other equipment in the mobile sensor box via an Ethernet network interface.

- Camera 1 is located in front at the beginning of the conveyor belt; therefore, it is before the sorting worker, and it is used to recognise and classify the waste objects on the belt.

- Camera 2 is located at the end of the conveyor belt; therefore, it is after the sorting worker and is used to determine whether a waste object has been removed from the sorting belt or not. This data is used as a feedback loop for the classification model.

- Camera 3 is located next to the projector and provides object tracking data to highlight the waste objects to be sorted out in colour for sorting staff using the projector.

The camera system, in conjunction with the programmable logic controller (PLC) (Siemens Simatic ET 200SP (Siemens AG, Munich, Germany)) and conveyor belt speed measured by the encoder (Siemens PROFINET FS15 (Siemens AG, Munich, Germany)), ensures precise synchronisation and efficient data capture. The PLC triggers Cameras 1 and 2 simultaneously every 600 mm of conveyor belt length. This approach minimises data volume (frame rate < 1.5 Frames Per Second (FPS)) by ensuring each object is captured only once, thereby optimising real-time performance. As a result, the system operates more efficiently in real time and requires no intervention by sorting workers. This setup represents the fully configured system; however, the system is modular and adaptable. It can be deployed in different configurations to suit various hardware and integration requirements. These configurations and the corresponding software pipelines and hardware setups are shown below.

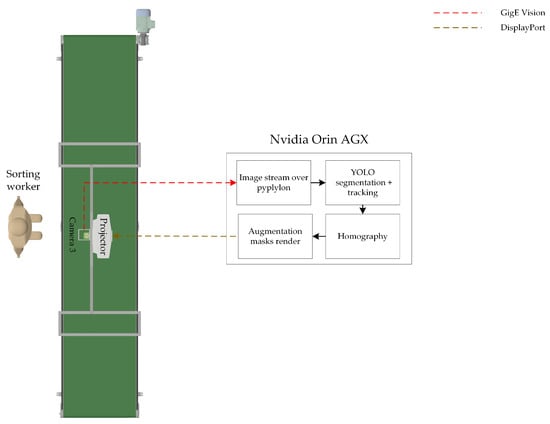

2.2.1. Standalone Orin AGX Configuration

In this setup, all computer vision tasks, including image acquisition via GigE Vision using the pypylon library [14], You Only Look Once (YOLO) segmentation [15] and tracking, homography transformation, and augmentation mask rendering, are executed directly on the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin 64 GB (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (see Figure 3). A single camera positioned above the sorting worker is used for tracking and classification tasks. Homography transformation is a mathematical technique in computer vision used to map points between two planes. It is particularly useful for correcting perspective distortions or aligning images from different viewpoints [16]. In the context of the recAIcle system, homography transformation is used to accurately overlay masks, calculated from camera images, and project them onto waste objects on the conveyor belt, even as their orientation or position changes. The augmentation masks are rendered and transmitted via DisplayPort to the projector, offering real-time visual guidance to the sorting worker. This variant minimises latency and hardware complexity.

Figure 3.

Standalone Orin AGX Configuration of the recAIcle assistance system.

The standalone system is best suited for material streams where the appearance of waste objects remains relatively consistent, as significant changes in appearance could reduce classification accuracy and system performance. Additionally, tracing is necessary because sorting workers alter the orientation and position of the waste objects during the sorting process.

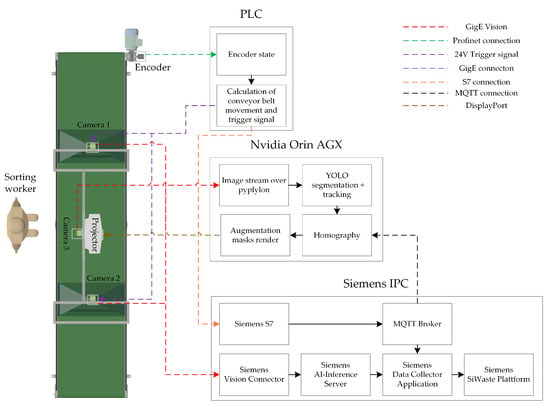

2.2.2. Hybrid Orin–IPC Configuration

As shown in Figure 4, the NVIDIA Orin AGX performs low-latency image processing, detection, and augmentation mask rendering as seen in the Standalone Orin AGX Configuration. In the fully integrated system, a Siemens IPC manages communication with a Siemens S7 PLC, the Vision Connector, and the SiWaste platform. Data exchange between the Orin and IPC is handled via Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT), enabling integration with industrial data collection and monitoring systems. The PLC calculates the trigger points for cameras 1 and 2 using data from the encoder, which is connected via a Profinet connection. The cameras are triggered via a 24-volt signal. The position of the conveyor belt is also communicated to the IPC via the S7 PLC and transmitted over MQTT to Orin. The triggered cameras provide simultaneously acquired images to the IPC via the Siemens Vision Connector using GigE Vision. These images are processed by the Siemens AI Inference Server, where a model is deployed to check whether an object was removed and to label it accordingly. All the so-generated training data is collected via the Siemens Data Collector and then uploaded to the cloud for further processing or saved in the local SiWaste instance for monitoring and analytics. This system is recommended for applications where the waste stream and the appearance of waste objects are volatile, requiring continual learning to adapt to changes in real time. The fully integrated system enables real-time tracking of augmented waste objects, comprehensive monitoring, and continual learning, making it ideal for dynamic and volatile waste streams.

Figure 4.

Hybrid Orin–IPC Configuration of the recAIcle assistance system.

2.2.3. Full IPC Inference Configuration

In this configuration, image acquisition from the GigE Vision camera is routed directly to the Siemens IPC (see Figure 5). The Siemens AI Inference Server processes detections and the IPC also handles the rendering of the augmentation mask and the homography transformation. Although this configuration may introduce higher inference latency, it allows seamless integration into existing Siemens automation and analytics ecosystems. Object tracking is realised using data from the encoder. The augmentation masks are adjusted based on the time between projected frames and the distance measured by the encoder. This adjustment ensures that the movement of the augmentation masks is synchronised with the speed of the conveyor belt and, therefore, with the speed of the waste objects. These masks are projected for a fixed amount of time. While this synchronisation ensures alignment with the conveyor belt speed, a key limitation is that the mask remains projected even after the sorting worker removes the augmented object. However, the encoder-based system represents the most cost-effective variation. This configuration requires only a single camera to capture the waste stream before it enters the sorting cabin, making it a cost-effective solution for simpler setups.

Figure 5.

Full IPC Inference Configuration of the recAIcle assistance system.

2.3. Learning from Sorting Workers

The expert-driven learning framework demonstrated effectiveness in capturing and replicating the decision-making patterns of experienced sorting workers. In operational trials, the synchronisation between the encoder and the PLC ensured that waste objects appearing in the first camera’s image could be matched with high accuracy to their corresponding positions in the second camera’s image. Positional deviations were consistently maintained well below one object length. This precise synchronisation enabled reliable Intersection over Union (IoU) calculations for object matching, even under varying belt speeds and lighting conditions.

The previously described PLC setup ensures that the synchronised cameras are triggered in such a way that an object appearing in an image from the first camera appears at nearly the same location in the corresponding image from the second camera, with only a constant frame offset. Using this synchronisation, IoU calculations of bounding boxes from the two cameras allowed the detection of objects removed by workers between the two capture points. The removal events identified in this manner were stored via the Data Collector Application on a File Transfer Protocol (FTP) server, providing ground truth data for retraining the classification model, enabling learning from observation and continual learning.

Initially, a one-class object detection model was trained exclusively on synthetic data and deployed to a Siemens Industrial Edge device running the AI Inference Server. This model achieved robust object localisation, enabling accurate identification of removed items. Building on this foundation, a binary classification model was developed by adding a classification head to the one-class object detection model. The binary classification task was further enhanced by integrating the model into the Siemens Vision Engineering Portal (VEP), formerly known as Vision Quality Inspection.

The Siemens VEP serves as a development and configuration environment for integrating machine vision systems into industrial automation workflows. Within the projection-assisted sorting prototype context, the VEP was used to configure camera connections, define vision jobs, and manage data flow between the image acquisition hardware and the Siemens AI Inference Server. Its graphical interface allows engineers to specify image preprocessing steps and communication protocols without requiring extensive low-level programming. By providing a unified platform for vision configuration and industrial communication, the VEP ensures that the camera and detection modules can be rapidly deployed, maintained, and updated in alignment with factory automation standards.

Active learning techniques were implemented within the VEP to improve classification accuracy. Low-confidence predictions were flagged during upload, corrected by human reviewers, and reintegrated into the training dataset. This feedback loop enabled continuous learning and incremental accuracy gains over successive retraining cycles. Several AutoML methods were also integrated to automate hyperparameter tuning, further optimising the model’s performance.

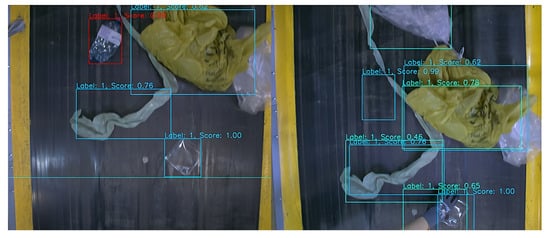

Qualitatively, the system demonstrated adaptability to subtle operator-specific sorting criteria that were not explicitly part of the original training set. This highlights the system’s capability to evolve toward alignment with the operational priorities and implicit decision rules applied by experienced sorting workers. An example of this binary classification process is illustrated in Figure 6, where waste objects on the conveyor belt are shown before and after manual sorting. Bounding boxes, which delineate the detected object, are used to characterise the area in which each object is located. The red bounding box marks an object that was sorted out and is no longer visible in the post-sorting image. This removed object was subsequently assigned to the material class or target fraction, such as Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET). The proposed framework offers a scalable and adaptable solution for improving material-specific recognition accuracy in recycling applications by integrating active learning, precise synchronisation, and advanced vision systems. The continuous feedback loop ensures that the system evolves in response to operational needs, aligning with the priorities of experienced sorting workers while maintaining compliance with industrial automation standards.

Figure 6.

Visualisation of the Sorting Process with Bounding Boxes Before and After Manual Sorting.

2.4. Continual Learning

Most AI models are trained once and used for their respective purposes. These static models lack the ability to learn or adapt. For the recAIcle system, this would mean that if a new type of waste object is recognised on the sorting belt, the system would probably not be able to classify it correctly. This limitation would compromise the system’s longevity as the waste composition changes significantly over time and depends on many factors, such as the region under consideration, local events, global trends, and demographics [17]. Therefore, continuous learning was integrated into the classification model of the recAIcle system. This means that the ML model can access data from past decisions, learn from it and use this generated knowledge for its subsequent decisions. As a result, the model continues to evolve after each decision and associated feedback [18]. In the case of recAIcle, the system learns from the sorting workers as described above by comparing which objects were taken from the sorting belt and which it predicted. After certain time intervals, the system is retrained with the feedback received. This is intended to increase the system’s accuracy over time, recognise new objects and ensure the system’s longevity. While the results of continual, federated, and federated continual learning trials are beyond the scope of this publication, they are detailed in a separate study [19]. In the previously conducted experiments, A biweekly strategy was the most successful, using an initial batch of 10,000 images followed by 25 batches of 5600 images, combining 1600 new images with 4000 randomly selected images from previous batches to reduce catastrophic forgetting.

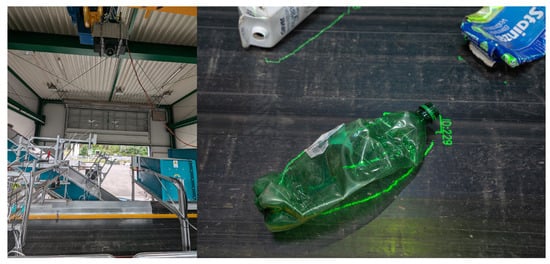

2.5. Augmentation

In order to support and interact with sorting workers, a human–machine interface (HMI) is required to bridge the recAIcle system and the sorting workers. The augmentation system visually indicates whether an object should be sorted out by displaying different coloured borders around the waste objects. The objects are highlighted using a high-intensity projector (Optoma ZU820T) (Optoma Corporation, Hemel Hempstead, UK) mounted vertically above the sorting belt (see Figure 7, left). The projected markings follow the objects in real time, as shown in Figure 7 (right). The results focus on the Standalone Orin AGX Configuration. The projected markings follow the objects in real time.

Figure 7.

The image illustrates the projector setup in the DWRL on the left. On the right, it showcases an example of an augmentation mask used to visually highlight target objects on the conveyor belt for sorting assistance.

Image data from camera 3 is used for object tracking and processed with the NVIDIA Orin AGX. The proposed system achieved stable real-time operation at approximately 30 FPS, with an average interference latency of less than 15 ms. The YOLO-based segmentation model reliably detected and segmented the target object within the camera’s field of view. The perspective transformation accurately mapped detected object contours to the physical projection space, ensuring precise alignment between the visual overlay and the actual object location.

Operational trials were conducted on a conveyor belt operating continuously at 0.5 m/s, with a heterogeneous mixture of PET and beverage carton (BC) objects. Therefore, the model was trained to segment and classify BC and PET. It achieved a precision of 92.996%, a recall of 88.823%, and a mean Average Precision (mAP50) of 92.407%. The mean Average Precision at Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 (mAP50-95) was 82.621%. Additionally, the F1 score was 90.79%. For the individual classes, the model achieved a precision of 94.121%, a recall of 89.997%, and an F1-score of 91.9% for BC. For PET, the model achieved a precision of 92.996%, a recall of 88.823%, and an F1-score of 89.9%. The projection-assisted guidance successfully highlighted target objects for human operators. Colour-coded overlays were clearly visible under typical recycling facility lighting conditions. An example of the augmented objects on the conveyor belt is shown in Figure 7. The tracking system maintained consistent object identification across frames, even in the presence of partial occlusions or overlapping items.

The integration of multi-threaded image acquisition, real-time YOLO inference, and synchronised projector output enabled uninterrupted guidance during continuous conveyor belt operation, demonstrating the system’s applicability for industrial recycling workflows.

2.6. Deployment Strategies and Adaptability

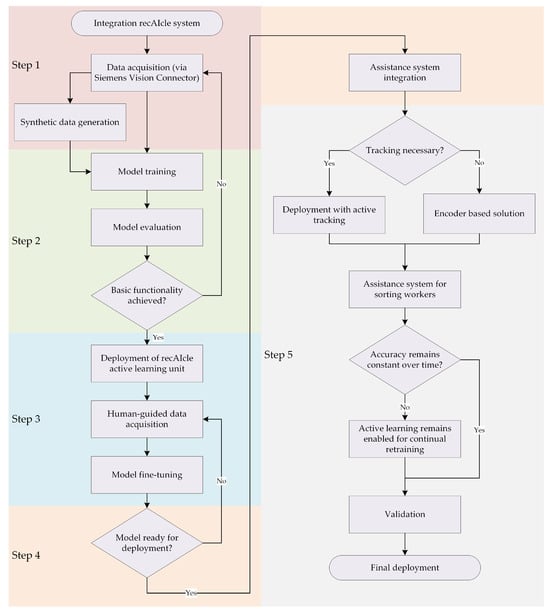

The recAIcle system is modular, as shown before, has multiple configurations, and is adaptable to different material streams. In the experiments presented, the system was deployed for plastic packaging waste. Figure 8 illustrates a decision diagram that outlines the migration and deployment process for introducing the system to a new material stream.

Figure 8.

Deployment workflow of the recAIcle system, from data acquisition and model training to assistance system setup and continual learning.

The first step in any deployment is data acquisition for the selected material stream, which can be supplemented by synthetic data generation. In the second step, different models are trained, tested, and evaluated until they achieve a basic level of functionality. This workflow was demonstrated in an experiment with steel scrap from an incineration treatment plant with copper-contaminated objects. Once this functionality is established (Step 3), the active learning unit is deployed, allowing the basic model to be improved by observing the actions of expert sorting workers. Over time, the model’s performance is periodically evaluated. When an acceptable level of accuracy is reached (Step 4), the assistance system is deployed.

At this stage, the system can be configured for deployment with either active or encoder-based tracking, as shown in the right-hand branch of Figure 8. In Step 5, a decision is made on whether continual learning is required. If so, the active learning unit remains active, and whenever model accuracy decreases over time, the model is retrained with newly acquired and operator-labelled data. This feedback loop, visualised in Figure 8, ensures the deployed model maintains reliable performance across different material streams and operational conditions.

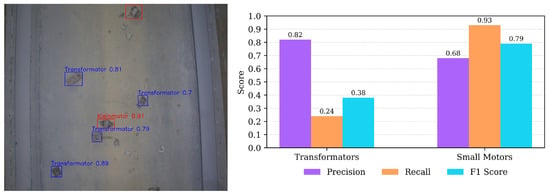

Evaluation after training on a dedicated test set containing 101 real-world images from a scrap fraction obtained after incineration slag processing demonstrated that the AI model, trained on a small dataset enhanced with synthetic data using the Alpha Matting-Modell ViTMatte, was able to detect electrical components such as small motors and transformers within the mixed metal stream. Manual review of the detection results confirmed correct identification in a substantial proportion of cases, although some misclassifications occurred, particularly in situations with strong occlusion or partial visibility of the target objects. These results illustrate the feasibility of synthetic-to-real transfer in this context but also highlight the need for additional domain adaptation and real-world data refinement to improve robustness.

Figure 9 summarises the quantitative evaluation for the two object classes. The model achieved a high precision of 0.82 for transformers, but recall was limited to 0.24, resulting in a modest F1 score of 0.38. In contrast, small motors were detected with a recall of 0.93 and a precision of 0.68, leading to an F1 score of 0.79. These results indicate that while the model can successfully generalise to certain object types, performance varies strongly by category. In particular, transformer detection suffers from a high false-negative rate, whereas small motors can be identified with comparatively high reliability.

Figure 9.

Quantitative evaluation results (red = small motors, blue = transformers) corresponding to Step 2 of the deployment process (model training and evaluation).

Evaluation on the test set of 101 real-world images containing mixed metal and electrical components demonstrated that the AI model, trained on a mix of real data and synthetic data, was able to detect electrical items such as small motors and transformers within the scrap stream. These findings indicate that the performance of an assistance system is insufficient, but the model is ready to enter the human-guided learning phase (step 3).

3. Discussion

The survey results show that manual waste sorting remains relevant and necessary in the 21st century. Remarkably, all participants who use manual sorting expressed interest in assisting their sorting workers with AI-based solutions. For these participants, assistance was deemed more relevant than monitoring. The survey primarily targeted companies in the DACH region, but companies from Slovenia and the Czech Republic also participated. This was most likely due to DACH-based parent companies encouraging their subsidiaries to participate.

The different hardware and software configurations demonstrate that the developed system is adaptable to the end user’s needs. From a sustainability and longevity perspective, deploying the hybrid configuration is recommended, as it offers the most flexibility and scalability.

The presented setup allows the system to learn from sorting workers without interrupting their workflow. However, the selection of sorting workers and their individual sorting habits could introduce biases into the model. To minimise this risk, the model should not rely on data from a single individual. The more workers contribute to AI training, the less influence a person’s biases will have on the trained model.

During the operation of the augmentation system, it was observed that projecting segmentation masks directly onto the sorting belt could introduce visual artefacts into the camera’s input stream. These artefacts occurred because the projected overlays were visible in the captured frames, potentially altering the appearance of waste objects and affecting detection accuracy. The projection masks were programmed to blink at a controlled frequency to mitigate this issue. Frames used for detection were captured when no overlays were projected, while projection frames were displayed only after the inference step was complete. This timing strategy significantly reduced the risk of projection-induced artefacts in the input data while providing operators with clear and timely visual cues.

Additionally, it was observed that the augmentation mask lagged behind the objects on the conveyor belt by approximately 10–20 mm. This effect resulted from object movement between frames and the overall image-to-projection latency. The issue can be mitigated by applying interpolation between consecutive camera frames in combination with a static projection offset to compensate for the motion.

The experiments with scrap demonstrate that the recAIcle system can already achieve a basic level of functionality with only a small number of training images, particularly when complemented by synthetic data. The inaccuracies with transformers, which are often misclassified as small motors, do present a challenge; however, this is not problematic, as both classes are intended to be removed from the material stream. Although the performance was insufficient for deployment as a standalone assistance system, the results confirm the feasibility of establishing an initial working model with limited real-world data. This foundational capability is crucial, as it enables the subsequent transition to Step 3 of the deployment process, where the model can be iteratively improved through human-guided learning by observing and incorporating the decisions of expert sorting workers.

4. Materials and Methods

The following section describes the materials, hardware, software, and experimental methodology in detail. Most experiments and the development of the assistance system were conducted using separately collected plastic waste. The specific methods used for each experiment are outlined below.

4.1. Market Survey

To collect the data, an online questionnaire was created using the Google Forms platform and made available to potential participants via email. The survey was targeted at recycling companies and operators of sorting facilities to gather insights into current practices, technological adoption, and perceived challenges in material separation, regardless of the material stream. The survey consisted of twelve questions that could be answered either as free text or by multiple-choice or single-choice selection. To maximise participation rates, efforts were made to design the questionnaire as compact as possible, requiring only three to five minutes to complete. A total of 41 companies from Germany, Austria and Switzerland were invited by email to participate in the survey. The sample included small, medium-sized, and large companies to ensure diverse representation. The questionnaire was divided into two sections:

The Company data section requested information on the company’s location, field of activity, types of waste present and the forms of manual sorting used. In order to prevent multiple voting, the company name was also requested.

The Assistance system recAIcle section focused on the relevance of the recAIcle system from the company’s perspective. It also provided an opportunity for respondents to.

The survey design prioritised simplicity and clarity to encourage participation. The collected data provided insights into industry needs and expectations, forming the basis for refining the development of the recAIcle assistance system.

4.2. System Development and Use-Case-Specific Variants

The system variants described in this work were derived directly from the requirements and use cases outlined by Aberger et al. [12]. These prior analyses identified the operational constraints, performance targets, and integration needs for projection-assisted sorting systems in industrial recycling environments. Building on this foundation, the present study adapted the architecture to address specific deployment scenarios, ranging from standalone embedded inference to hybrid and fully integrated industrial configurations, while maintaining compliance with the functional and interoperability requirements specified in the earlier work. This approach ensured that each variant aligns with proven operational workflows and supports current and anticipated use cases in waste sorting while also providing flexibility for future scalability and adaptation to other material streams.

4.3. Learning from Observation

As outlined, sorting workers represent an expert instance within the recycling process, possessing tacit knowledge and decision-making skills that are difficult to encode explicitly into automated systems. Therefore, our methodology was designed to enable the system to learn directly from their actions. By synchronising multiple cameras along the conveyor belt through an encoder-controlled PLC programme, the system ensures that an object detected in the first camera’s field of view is captured at nearly the same position in the second camera’s view, with only a constant frame offset. This setup allows us to identify whether a sorting worker has removed an object between the two capture points by calculating the IoU between the bounding boxes from both camera images.

Objects that disappear between camera positions are assumed to have been intentionally removed by the operator. These removal events, along with the corresponding first camera images, creating a labelled dataset. This dataset can then be used to (re)train the classifier, effectively transferring the operators’ decision-making patterns to the ML model. By incorporating this expert-driven feedback loop into the training process, the system is continuously adapted to reflect actual sorting priorities and operational realities, thereby bridging the gap between human expertise and automated classification.

4.4. Augmentation

The augmentation focuses on the real-time approach with tracking but without data from the encoder. This approach is in line with the presented standalone solution. A real-time object detection and projection-assisted sorting system was developed to support manual sorting processes in recycling facilities. The system integrates a Basler industrial camera (pypylon library) for image acquisition, a YOLO-based segmentation model for object detection, and a projector-based visual guidance system to highlight target objects for human operators.

The YOLOv8 segmentation model used in this system was trained on a custom dataset compiled from multiple video recordings of sorting workers performing their tasks in recycling facility environments. All data for the model were recorded at the DWRL using a standalone setup. During the data collection process, the conveyor belt speed was varied between 0.2 m/s and 0.5 m/s, different sorting workers were involved, and the working height of the employees was adjusted. In total, approximately 80 h of video footage were recorded. These variations were introduced to improve the model’s generalisation capabilities. The training data included various object categories relevant to the sorting process, annotated with pixel-level segmentation masks to enable precise contour detection. The data was semi-automatically annotated to ensure both efficiency and accuracy in the labelling process. For the final iteration of the model, a total of 8000 images were used.

After training, the model was optimised for deployment on the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin embedded platform. To leverage the device’s Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA) cores for maximum inference speed, the trained YOLOv8 model was converted to TensorRT format. This optimisation significantly reduced inference latency and enabled stable real-time performance under the computational constraints of the prototype hardware.

The image acquisition module uses the pypylon library to capture high-resolution RGB frames at a fixed network IP address. The camera is configured for continuous acquisition, with image frames converted to the OpenCV [20] BGR format for subsequent processing. Homography transformation parameters, determined in a calibration step, are used to map object contours from the camera’s coordinate system to the projector’s coordinate system.

The detection and segmentation pipeline is implemented using the Ultralytics YOLO framework. Each captured frame is processed in real-time to generate object bounding boxes, class predictions, segmentation masks, and track IDs. A multi-threaded architecture ensures low-latency operation:

- Thread 1 (Image Generator) acquires images from the camera, runs YOLO inference, extracts segmentation masks, applies perspective transformation, and renders the projected overlays.

- Thread 2 (Logic Processor) handles frame synchronisation and manages render commands to ensure stable projection timing.

- Main Thread uses PySDL2 [21] for high-performance display output to the projector.

Objects detected within pre-defined Regions of Interest (ROIs) are tracked over time using the YOLO. The segmentation masks of relevant objects are warped via homography into the projector’s display space and visualised in colour-coded overlays (e.g., green for class 0, red for class 1). These overlays are projected directly onto the sorting belt to highlight the physical location of the target objects.

A binary material mixture consisting of BC and PET objects was used for the sorting experiments. The material originated from separate collection streams and was sourced from multiple sampling locations to ensure variability in object shape, size, and surface properties. The class membership of each item was manually verified prior to the experiments to ensure accurate ground truth labelling. This heterogeneous composition was chosen to represent realistic sorting conditions in recycling facilities and to evaluate the system’s ability to detect and highlight different material categories under operational constraints.

4.5. Deployment Strategies

The first two steps of the deployment strategies were tested with electrical components within mixed metal scrap, recovered from thermal waste treatment slag. The image data were collected at a slag treatment facility in Austria, where the material was processed on a 1200 mm wide conveyor belt at a speed of approximately 0.3 m/s. The waste objects were fed onto the conveyor using a dosing bunker equipped with a vibratory feeder. In total, approximately 1–2 tons of material were recorded., The dataset comprised two classes: small electric motors (512 images) and transformers (287 images). Additionally, the dataset included images of the empty conveyor belt (417 images) and pure metal without electrical devices (3764 images). An extra 101 images containing a mixture of metal and electrical devices were used as a test set.

The training process followed a previously presented standard pipeline: synthetic data generation was performed to augment the dataset, followed by training the detection model entirely on these synthetic images. The trained model was subsequently evaluated on the real mixed-metal test set to assess its transferability from synthetic to real-world data.

5. Conclusions

The study introduces recAIcle, an AI-powered assistance system for manual waste sorting that combines machine learning, continual learning, and projection-based augmentation. The system learns from the actions of experienced sorting workers and provides real-time visual guidance via a projector, highlighting target objects on the conveyor belt. Trials demonstrated high detection precision (≈93%) and real-time operation under realistic recycling conditions. A market survey showed that 82% of participating companies were interested in AI-supported manual sorting. Overall, recAIcle represents a scalable and adaptable approach to modernising waste sorting and promoting digitalisation and efficiency in recycling operations. The recAIcle project successfully demonstrates the potential of AI-driven assistance systems to revolutionise manual waste sorting. The system bridges the gap between traditional manual sorting and modern digital solutions by combining human expertise with advanced ML and augmentation technologies. The integration of continual learning ensures that the system evolves alongside changing waste compositions, maintaining its relevance and accuracy over time. Experimental results validate the system’s ability to enhance sorting efficiency and accuracy while addressing challenges such as operator biases and projection artefacts.

Future work will optimise the system’s performance, expand its application to additional waste streams, and foster broader adoption in industrial settings. Long-term studies will be conducted to evaluate the system’s scalability and adaptability under diverse operational conditions. While the current study does not quantitatively demonstrate the direct improvement in sorting performance, this limitation presents a significant opportunity for future research. Specifically, the lack of concrete data on how the recAIcle system enhances the speed, accuracy, efficiency, or convenience of the sorting process underscores the need for systematic user studies. These studies will be critical in providing empirical evidence of the system’s real-world benefits and its potential to revolutionise waste management practices. Furthermore, power calculations could be conducted to determine the number of picks per minute and shifts required to detect a 5% purity improvement at α = 0.05 and power = 0.8. This will ensure that future studies are statistically robust and capable of providing reliable evidence of the system’s benefits. Future work should therefore include systematic user studies to provide this evidence and further showcase the system’s real-world benefits.

The recAIcle system aims to further contribute to a more efficient and sustainable circular economy by addressing these areas.

Author Contributions

J.A.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Visualisation; L.B.: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Review and Editing; J.P.: Project Administration, Funding Acquisition, Writing—Review and Editing; G.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Software; B.H.: Resources, Software; M.H.: Resources, Software, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition; R.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Project Administration, Writing—Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The RecAIcle project (FFG project number: FO999892220) is funded by the FFG as part of the AI for Green 2021 (KP) call.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Benedikt Hacker works at Siemens AG Ostereich. Jesús Pestana works at Pro2Future GmbH (8010 Graz). Georgios Sopidis and Michael Haslgrübler work at Pro2Future GmbH (4040 Linz). The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AVAW | Chair of Waste Utilisation Technology and Waste Management |

| BC | Beverage Carton |

| CUDA | Compute Unified Device Architecture |

| DACH | Germany (D), Austria (A), and Switzerland (CH) |

| DWRL | Digital Waste Research Lab |

| FFG | Austrian Research Promotion Agency (Forschungsförderungsgesellschaft) |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| FTP | File Transfer Protocol |

| HMI | Human–Machine Interface |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| IPC | Industrial PC |

| LIBS | Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| PLC | Programmable Logic Controller |

| recAIcle | Recycling-oriented collaborative waste sorting by continual learning |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| SBS | Sensor-Based Sorting |

| VEP | Vision Engineering Portal |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- Plastics Europe. Plastics—The Facts 2021: An Analysis of European Plastic Production, Demand and Waste Data. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Plastics-the-Facts-2021-web-final.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Schlögl, S. Stand der Technik von Kunststoffsortieranlagen und Potentiale Durch Sensorische Stoffstromüberwachung. Master’s Thesis, Montanuniversität Leoben, Leoben, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cesetti, M.; Nicolosi, P. Waste processing: New near infrared technologies for material identification and selection. J. Inst. 2016, 11, C09002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julius, J.; Pretz, T. Sensor Based Sorting in Waste Processing. In Separating Pro-Environment Technologies for Waste Treatment, Soil and Sediments Remediation; Julius, J., Pretz, T., Gente, V., La Marca, F., Eds.; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2012; pp. 59–76. ISBN 9781608054725. [Google Scholar]

- Lubongo, C.; Alexandridis, P. Assessment of Performance and Challenges in Use of Commercial Automated Sorting Technology for Plastic Waste. Recycling 2022, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilts, H.; Garcia, B.R.; Garlito, R.G.; Gómez, L.S.; Prieto, E.G. Artificial Intelligence in the Sorting of Municipal Waste as an Enabler of the Circular Economy. Resources 2021, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchese, A.; Digiesi, S.; Mummolo, G. Human Performance of Manual Sorting: A Stochastic Analytical Model. In Industrial Engineering and Operations Management; Gonçalves dos Reis, J.C., Mendonça Freires, F.G., VieiraJunior, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 445–456. ISBN 978-3-031-47057-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fotovvatikhah, F.; Ahmedy, I.; Noor, R.M.; Munir, M.U. A Systematic Review of AI-Based Techniques for Automated Waste Classification. Sensors 2025, 25, 3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andeobu, L.; Wibowo, S.; Grandhi, S. Artificial intelligence applications for sustainable solid waste management practices in Australia: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 834, 155389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihsanullah, I.; Alam, G.; Jamal, A.; Shaik, F. Recent advances in applications of artificial intelligence in solid waste management: A review. Chemosphere 2022, 309, 136631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gethmann, C.F.; Buxmann, P.; Distelrath, J.; Humm, B.G.; Lingner, S.; Nitsch, V.; Schmidt, J.C.; Spiecker genannt Döhmann, I. Künstliche Intelligenz in der Forschung; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; ISBN 978-3-662-63448-6. [Google Scholar]

- Aberger, J.; Shami, S.; Häcker, B.; Pestana, J.; Khodier, K.; Sarc, R. Prototype of AI-powered assistance system for digitalisation of manual waste sorting. Waste Manag. 2025, 194, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandlbauer, L.; Sarc, R.; Pomberger, R. Großtechnische experimentelle Forschung im Digital Waste Research Lab und Digitale Abfallanalytik und -behandlung. Österr Wasser-Und Abfallw 2024, 76, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basler, A.G. pypylon API. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/basler/pypylon?tab=readme-ov-file (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Ultralytics. YOLO Segmentation. 2023. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/de/tasks/segment (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Szeliski, R. Computer Vision; Springer: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-1-84882-934-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.C.; Bhada-Tata, P.; van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4648-1329-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Z.; Liu, B.; Huang, X. Continual Learning of a Mixed Sequence of Similar and Dissimilar Tasks. In Proceedings of the 34th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2020), Online, 6–12 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shami, S.; Aberger, J.; Pestana, J.; Häcker, B.; Sarc, R.; Krisper, M. Federated continual learning for vision-based plastic classification in recycling. Waste Manag. 2025, 205, 114976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradski, G.; Kaehler, A. OpenCV: Open Source Computer Vision Library; GitHub: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- py-sdl Contributors. PySDL2: Python Ctypes Wrapper Around SDL2; GitHub: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).