Abstract

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) is widely used at the laboratory level for monitoring/diagnostics of battery cells, but the design and validation of in situ, online measurement systems based on EIS face challenges due to complex hardware–software interactions and non-idealities. This study aims to develop an integrated co-simulation framework to support the design, debugging, and validation of EIS measurement systems devoted to the online monitoring of battery cells, helping to predict experimental results and identify/correct the non-ideality effects and sources of uncertainty. The proposed framework models both the hardware and software components of an EIS-based system to simulate and analyze the impedance measurement process as a whole. It takes into consideration the effects of physical non-idealities on the hardware–software interactions and how those affect the final impedance estimate, offering a tool to refine designs and interpret test results. For validation purposes, the proposed general framework is applied to a specific EIS-based laboratory prototype, previously designed by the research group. The framework is first used to debug the prototype by uncovering hidden non-idealities, thus refining the measurement system, and then employed as a digital model of the latter for fast development of software algorithms. Finally, the results of the co-simulation framework are compared against a theoretical model, the real prototype, and a benchtop instrument to assess the global accuracy of the framework.

1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have become one of the crucial components for the modern automotive sector. This technology entered into scene years ago, outperforming other energy storage solutions mainly thanks to its high energy density and reduced memory effects [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. However, LIB cells still suffer from numerous degradation/aging mechanisms, from thermal and mechanical stress-induced effects to internal chemical deterioration (e.g., electrode/binder/SEI degradation, formation of dendrites, loss of ion inventory, etc.), which affect the correct operation, safeness, and lifetime of the battery cell itself [8]. For this reason, automotive companies heavily invest in the research and development towards safer and cheaper batteries that can last for a longer time in efficient operation. In this context, other than improving the chemical and material properties of the battery cell, the development of in-situ and in-operando (i.e., online) monitoring techniques for LIBs can contribute to the progress of energy storage systems. In particular, sensing the state parameters down to the cell level allows a deeper control on the overall battery pack and enables the possibility to actively react to degradation events by implementing smart procedures within the battery management system (BMS), with the final goal of improving safety, operation efficiency and extend the lifetime of each cell [9,10,11].

A non-invasive diagnostic technique generally employed to characterize batteries and extract useful diagnostic data is represented by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) [12,13,14,15]. This is a well-assessed measurement technique traditionally employed in laboratory set-ups by means of accurate but bulky instrumentation [16]. Still, it has recently attracted significant research activity towards its in situ and in operando implementation, demonstrating promising results [17,18,19,20]. EIS online monitoring requires the measurement of voltage and current vectors directly on the battery pack/module/cell [21,22,23] and the embedded implementation of post-processing algorithms for the final estimation of the impedance in the bandwidth of interest. Even though the technique is quite standard and well-known in the technical community when carried out at laboratory level, the realization of in operando EIS sensors with embedded algorithms poses many scientific and technological challenges, from understanding the effect of non-stationarity on the measurement result [24] to the consequent definition of proper methodologies capable of minimizing the measurement time [25,26]. Moreover, the in situ implementation of the technique requires the design of application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) that should be integrated at the very battery cell level. As far as the design, analysis, and validation steps for a given EIS integrated system are concerned, the tight interdependency between the hardware part developed in the ASIC and the software impedance reconstruction algorithm complicates the design of the ASIC as well as the development of novel and more efficient algorithms. Any minimal non-ideality in the hardware (HW) system can transform into an unforeseen high-uncertainty source in the final impedance estimation, while software (SW) algorithms may fail or produce wrong results when coupled with real hardware affected by noise and non-idealities. Current simulation approaches rely on the separate analysis of the HW scheme to be realized in the ASIC and SW algorithms that run on digital platforms. This approach can identify non-idealities but it is not able to define their impact as sources of uncertainty in the final impedance estimate. Indeed, even though many EIS hardware architectures are proposed in the literature [17,19,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33], they are still far from a widespread industrial application. This suggests that a single, integrated numerical framework should be developed and exploited during the design/analysis/performance evaluation phases of the EIS-based system to account not only for the independent non-idealities and sources of uncertainty in each sub-block of the hardware/software architecture, but also those generated due to the inherent interrelations between hardware and software in a global and comprehensive way. For example, the noise levels at the output of the excitation source and at the input of the A/D acquisition channels can be quite easily predicted by CAD analyses on the HW only, but the actual dynamic range in the vector estimation of voltage/current at each test frequency can be assessed only by including into the numerical analyses the SW algorithms (e.g., DFT-like) exploited to translate the sample records into the impedance complex value. Conversely, by inverting the point of view of the example, the choice of the optimal time-window to be used in the DFT-based algorithms in order to solve the trade-off between spectral leakage suppression and minimization of the noise floor can be made by consideration on the SW only (e.g., exploiting the side-lobe parameters and the equivalent noise bandwidth of the window), but the actual performance of the overall EIS investigation can be assessed only when the actual noise spectral densities at the input of the ADCs are available from CAD analysis on the HW architecture.

In this paper, an integrated co-simulation framework is proposed, which simulates the EIS system as a whole. It is made of a CAD circuit simulator directly linked to a numerical environment executing the impedance estimation algorithms. In this way, the effect of the non-idealities of the hardware design on the final impedance estimate can be identified. A model of the battery pack/module/cell can be included as well, to allow for a complete simulation. The purpose of such a simulation framework is to design both HW and SW according to an integrated approach, analyze the performance of an existing EIS-based prototype, or investigate sources of uncertainty (and correctly locate them within either the HW architecture or the SW algorithms) that otherwise are difficult, or even impossible, to be separately characterized when only experimental tests on the prototype are carried out. Given the completeness of the co-simulation framework and its capability to emulate HW–SW interrelations, it can also be used as the main simulator within a digital twin of the sensorized battery. Therefore, the final goal of the co-simulation framework is to emulate as accurately as possible the real implementation of the EIS system when connected and operating on the DUT, whatever the battery under test. In the literature, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there are no similar simulation frameworks that provide a complete overview of the entire EIS-based system with insights into HW–SW interactions.

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 reports the general structure of the co-simulation framework with more details than [34], and Section 3 details how to implement an EIS-based sensor in it, taking the architecture presented in [25] as an example. Then, Section 4 reports three different applications of the framework. Finally, Section 5 compares the results of the co-simulation framework with ideal models and experimental measurements obtained from a real prototype of the EIS-based sensor in the case of a simple RC circuit and a real battery cell. Conclusions are drawn in Section 6.

2. Structure of the Integrated Co-Simulation Framework

2.1. General Implementation of the Co-Simulation Framework

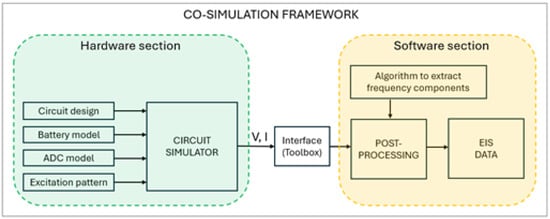

Figure 1 shows the general structure of the proposed simulation framework. It is made of two main core parts, namely, the circuit simulator of the overall HW architecture (incorporating the model of the battery cell) and the software part, which is the numerical simulation environment for the post-processing of raw data provided by the HW.

Figure 1.

Block structure of the proposed integrated co-simulation framework.

The former part has many inputs: the description of the analog circuit, the description of the analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) used in the architecture, and the battery model. They can be provided to the simulator by a SPICE netlist or a behavioral model in a suitable language, like Verilog-A or VHDL. Those models and netlists can be either the result of a custom transistor-level design, in the case of ASIC development, or the behavioral representation of commercial components, increasing the flexibility and usability of the framework. The excitation signal is digitally generated and provided in the form of a digital pattern to a DAC modeled in the circuit simulator. Furthermore, the framework enables the user to select the desired output signals from the circuit simulator, which can be either analog voltages and currents ideally sampled and digitally converted with infinite resolution or real digital signals sent out from the ADC model. In this way it is possible to embed/de-embed non-idealities of the ADC.

The numerical framework has a single external input, which is the algorithm used to estimate the impedance spectrum at selected frequency bins based on the raw data provided by the HW simulator. An essential role is played by the interface that connects the two core parts, which can be achieved by using a specific Toolbox or via a programming interface. The interface must allow the loading of electrical signals (i.e., voltages and currents as well as digital data) from the circuit simulator to the numerical environment.

2.2. Specific Implementation of the Co-Simulation Framework

The proposed simulation methodology can be implemented by using any combination of suitable software tools that meet the specifications described above. In this paper, the framework is realized by exploiting Cadence ic 6.17 as the circuit simulator and Matlab 2024b as the numerical environment. Cadence is the gold-standard software for ASIC design and allows mixed-signal simulations of analog and digital sub-systems described using either transistor-level circuits or hardware description languages (HDLs). For instance, it is possible to describe the ADC in Verilog-A, making the simulation faster and independent of the transistor-level implementation of the ADC, which could be provided by external companies with no access to the transistor-level design. Matlab is a flexible and easy-to-use numerical environment that provides different methods to import data efficiently from Cadence (e.g., through the command “mixedSignalAnalyzer” or the Toolbox Spectre/RF, which is the resource used in [34]) into the numerical software for the execution of the post-processing algorithms [35,36]. Those software suites are powerful and provide accurate and reliable results. They can run on a rather standard workstation, but they are expensive. In the following, all the simulations run on a Intel Xeon Silver 4310 with 12 cores, and the simulation parameters are set to maximize the accuracy. In this configuration, a single simulation takes about one hour, which is reasonable for offline simulations used for assessment of the EIS architecture or algorithm development.

3. Implementation of an EIS Architecture in the Co-Simulation Framework

From a theoretical perspective, the co-simulation framework can be used to model any kind of EIS-based sensor, even commercial architectures. However, the framework was originally conceived for informed ASIC design. Moreover, accurate simulations require an in-depth knowledge of both circuit architecture and software algorithms, which is not possible for commercial EIS sensors. For this reason, the proposed simulation framework was validated and tested throughout the numerical simulation and evaluation of the EIS-based integrated sensor–node prototype proposed in [25] for the online monitoring of lithium-ion battery cells. This was used in this work as the “Circuit Design” input in Figure 1. The algorithm used for impedance estimation, which is the external input to the numerical framework, is a custom algorithm based on the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and characterized by a peak search algorithm to identify the harmonic components of interest, as described in [25]. Although the simulation framework can theoretically work at any frequency band, the tests presented in this work are limited to the frequency range investigated by the real prototype proposed in [25] (i.e., from 1 Hz to 200 Hz) so as to have a direct comparison between the simulation and the real prototype. The selected frequency range is adequate for online monitoring of battery cells, since main battery features are still visible while the measurement time is limited with regard to laboratory-level measurement systems [10,17,18,19,37].

Linearity and stationarity of the measurement must be guaranteed by the measurement procedure realized by the HW architecture and SW algorithm, which are considered as input of the co-simulation framework. Those assumptions hold true for the EIS-based sensor node used as the example to validate the co-simulation framework in this work [17,25,26]. Linearity is ensured by applying a small excitation current, while the time-invariance condition is satisfied by relying on broadband excitation.

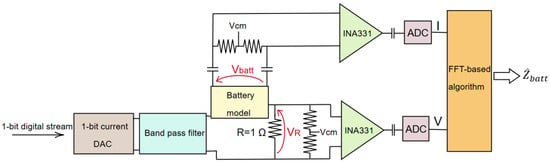

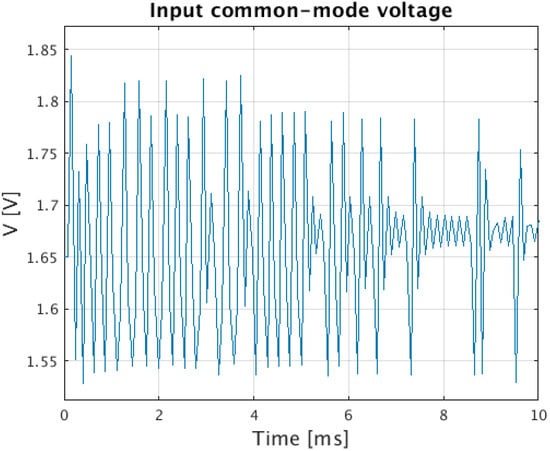

3.1. Hardware System

The circuit presented in [25] and reported in Figure 2 consists of the 1-bit delta-sigma digital-to-analog converter (DAC) combined with a voltage-to-current converter and a bandpass filter [18] for the generation of the current test signals, and two identical channels of measurement: one used to sense the voltage drop across the battery cell and the other used to sense the voltage across a 1- reference resistance. The EIS system exploits multisine excitation to reduce the measurement time. This multisine signal is synthesized in Matlab and modulated following a delta-sigma approach to create a 1-bit digital stream used as input (excitation pattern in Figure 1) to the DAC. The DAC output is then converted to a binary current signal (+Iref and −Iref) corresponding to bits 1 and 0. The exact value of Iref can be set by the final user; however, a fixed nominal current of 1 mA is considered in this work. Then, the bandpass filter (BPF) removes the high-frequency noise typical of sigma-delta-modulated signals. This approach allows for the generation of a current excitation signal with a good signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). After the filter, the measurement architecture consists of two acquisition channels acquiring the voltage drop across the battery cell and a reference resistor, respectively. The two voltages are then amplified by a factor of 900 using the Texas Instruments INA331 instrumentation amplifier (INA), whose SPICE model is provided by the manufacturer and used as input to the framework. One channel is AC connected to the terminals of the battery cell via high-value capacitors to filter out the inherent DC voltage component of the battery, even though the DC voltage of the battery is not modeled in the following tests. Polarization of the instrumentation amplifier is then assured by a resistive network made of high-value resistors. The other channel is DC connected to the reference resistor; however, the resistive polarization circuit is still present to force the instrumentation amplifier to work on the same biasing region, improving the symmetry of the system. In both cases, the input impedance of the acquisition channel is very high, making the burden current negligible. From these two direct measurements, it is possible to estimate the battery impedance following the two-voltage measurement approach [38]. At the end of each estimation channel, an ideal ADC models the acquisition channel of the high-resolution digitizer used in the prototype. The input capacitor of the ADC represents the AC coupling of the digitizer.

Figure 2.

Hardware circuit design proposed in [25] and used as the circuit design input to the simulation framework.

3.2. Software Algorithm

Assuming a negligible current flowing into the acquisition circuit and according to Ohm’s law, the voltage across the reference resistance R can be used to estimate the excitation current as follows:

Then, the battery impedance can be estimated by dividing the voltage measured across the battery cell and the estimated current value:

The post-processing algorithm implements the above theory as follows. The digitized voltages at the output of the measurement channels are imported into Matlab using the SpectreRF Toolbox. The voltage values are centered to zero to perfectly null the DC component and are referred back to the INA input by dividing for the INA DC gain. The FFT algorithm is then applied to the estimated voltage producing three distinct vectors containing the magnitude, phase, and corresponding frequencies. By applying Equation (1) for each frequency point, it is possible to estimate the magnitude and phase of the excitation current . Through the Matlab findpeaks function, it is possible to localize the values of the peaks in the magnitude vectors, thus defining the frequency bins corresponding to the multisine excitation. This vector will be used as the basis to localize the phase values. The same procedure is applied to obtain the magnitude and phase estimates of the voltage drop across the battery cell . Finally, the magnitude and phase of the battery impedance at the test frequencies is computed as follows:

The frequencies considered in this work are a subset of those used for the prototype developed in [25] (i.e., 4.64, 6.18, 7.73, 9.27, 13.91, 16.99, 20.09, 27.82, 72.63, 86.54, 100.45, and 120.54 Hz). This choice shortens the computation time without loss of generalization. Those particular numbers are set by the implementation of the system on a microcontroller-based prototype [25].

4. Applications of the Co-Simulation Framework

4.1. Exploiting the Co-Simulation Framework as a Debugger for EIS-Based Prototypes

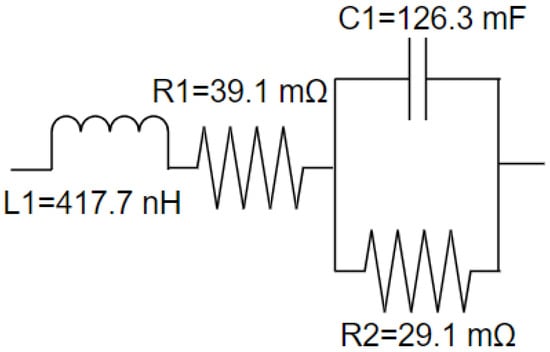

In this section, the proposed simulation framework is exploited to debug the EIS system already developed; therefore, to simplify the argumentation and focus on the modeling of the EIS measurement system only, a simplified RCL-based equivalent circuit model (ECM) of the battery cell is used, as reported in Figure 3. This simple ECM does not precisely reproduce the battery impedance, and the physical interpretation of the battery model is out of scope in this paper. However, it can be conveniently implemented in Cadence using ideal components, thereby facilitating the verification of the simulation framework. The values of passive elements used in the ECM are experimentally extracted from a real fully charged cylindrical battery cell Samsung ICR18650-26J 2600 mAh (Samsung SDI Co., Ltd., Yongin, South Korea) by using the Hioki IM3590 Chemical Impedance Analyzer (Hioki corp., Nagano, Japan). In this way, though the model is approximated, the impedance value of the ECM is in a meaningful range.

Figure 3.

Simplified equivalent circuit model of the fully charged battery cell Samsung ICR18650-26J used in the simulation framework for the preliminary analysis. Values of the parameters were experimentally extracted using the benchtop Hioki IM3590 Chemical Impedance Analyzer.

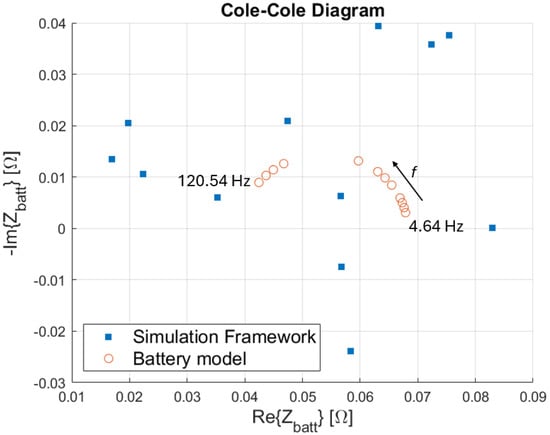

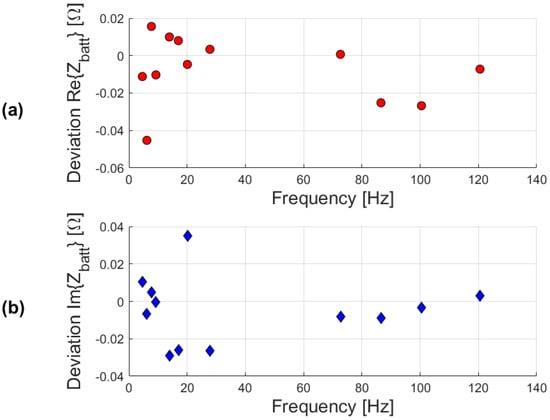

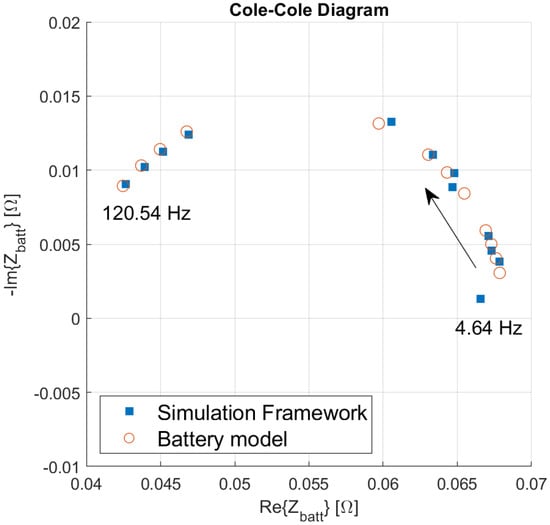

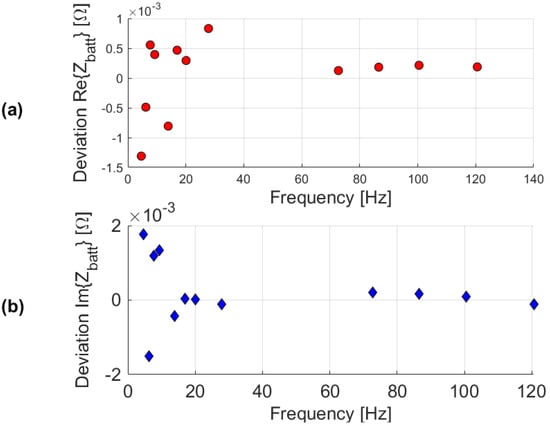

As a preliminary test, the impedance spectrum predicted through the co-simulation framework, which integrates the implementation of the full HW+SW corresponding to the prototype EIS system, is compared in Figure 4 to the reference analytical values provided by the simplified ECM described in Section 3. In Figure 5a and Figure 5b, the deviations between the simulation results and the battery model are reported for the real and imaginary parts of the impedance, respectively. The overall root mean squared deviation is 18.5 mΩ for the real part of the impedance and 17.8 mΩ for the imaginary part. These values are estimated as follows:

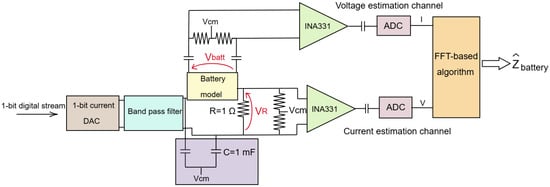

where is the reference impedance provided by the ECM and is the impedance predicted by the simulation framework. It is observed that the simulation results are significantly dispersed with regard to the reference impedance of the battery cell ECM, pointing out an unforeseen design issue in the EIS system HW. By exploiting the co-simulation framework it is possible to analyze all the electrical quantities of interest along the entire acquisition chain, and in this way not only identify unexpected non-idealities in the HW architecture, as with conventional eCAD tools, but also highlight their impact on the final impedance estimates thanks to the integration into the framework of the numerical algorithms devoted to the processing of electrical data. Specifically, the framework showed that the input common-mode (CM) voltage of the INA331s suffered from an important high-frequency noise, generating distortion at the INA331 output. This high-frequency CM noise derives from the high-frequency operation of the delta-sigma DAC, whose output is not completely filtered by the BPF. Indeed, while the BPF was designed to remove the high-frequency noise from the output current, a residual CM voltage noise passed through it and affected the CM input of the INAs. Time-domain simulation of the HW circuit reports clear glitches on the common mode voltage at the INA input, with peak values of around 1.85 V, as observed in Figure 6. Yet, the analysis only at the circuit level, using an eCAD tool, does not provide a direct link between the CM noise and the dispersion observed in the impedance estimates of Figure 4. This kind of correlation can be identified only by an integrated simulation approach like the proposed co-simulation framework. The presence of the high-frequency CM noise at the input of the INA331 was then experimentally verified on the prototype by using the Keysight CX3324A Device Current Waveform Analyzer (Keysight Technologies, Santa Rosa, CA, USA). The results between the simulation framework and the measurements obtained in the lab are consistent but not identical, given the impossibility of perfectly modeling all the parasitic components and their effects. However, the co-simulation framework demonstrated to be an effective debugging tool capable of locating and explaining misbehavior in a complex real prototype, which is otherwise rather impossible to detect.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the cell impedance at test frequencies, estimated by the implementation of the EIS-based prototype design into the co-simulation framework, with the analytical values predicted by the battery cell model.

Figure 5.

Deviations of the real (a) and imaginary (b) part of impedance when comparing simulation results with the battery model.

Figure 6.

Simulation of the common mode voltage at the input of the INA331 within the EIS-based sensor node modeled in the co-simulation framework.

4.2. Benefits of the Co-Simulation Framework in the Design Phase

Other than that, the simulation framework can also be exploited in the design phase, which is its original purpose. For instance, it can be used to design and optimize an architectural solution to the issue described above.

To eliminate the CM noise, two capacitors were added to the circuit after the bandpass filter (as shown in Figure 7) so as to force the CM voltage to stay equal to the reference value of 1.65 V by providing a low-impedance path for the high-frequency noise. A parametric analysis of the system in the simulation framework defined the optimal value of 1 mF for the filtering capacitances. With these two capacitors, the input CM voltage of the INAs stays in the allowed voltage range, and the differential voltage signals are correctly amplified. Even though the presence of the capacitors alters the amplitude and phase of the excitation current, the actual current flowing through the battery cell is monitored by the current estimation channel, and correctly estimated by Equation (2), following the two-voltage measurement approach.

Figure 7.

Refined architecture of the EIS-based system implementing the cancellation of the common-mode high-frequency noise, which was generated by the delta-sigma modulation of the excitation current.

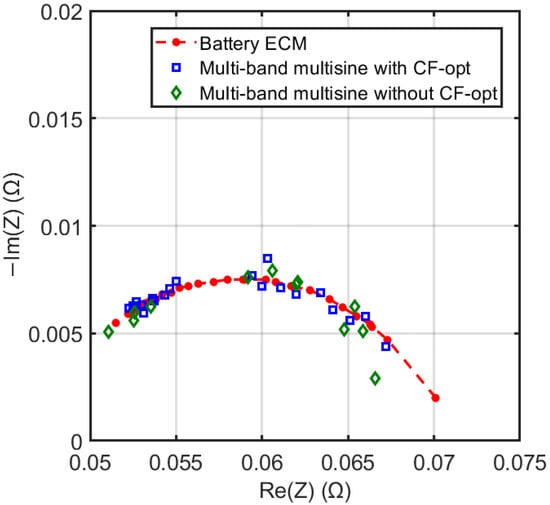

The Cole–Cole plot in Figure 8 shows the impedance values estimated at the test frequencies after the HW architecture refinement. The results of the simulator (blue squares) are now in good accordance with the ECM model (red circles) over the entire frequency band of interest. Residual discrepancies at the very low frequencies suggest the presence of other non-idealities that should be better investigated for further refinements of the EIS system. However, this test demonstrated the potentialities of the co-simulation framework in both the non-ideality search and correction phases, and a satisfactory accuracy level was achieved. Figure 9a and b report the deviations of the real and imaginary parts of the impedance after the refinement, respectively. The root mean square deviation is now strongly reduced to 0.59 mΩ for the real part and 0.86 mΩ for the imaginary part of the impedance.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the impedance estimated by the co-simulation framework after the modification of the EIS-based system architecture (compare Figure 7 with Figure 2), with the corresponding analytical values predicted by the battery cell model. The analyses carried out by means of the proposed integrated framework allowed for a refined design of the EIS-based system, in which a subtle source of uncertainty was successfully corrected.

Figure 9.

Deviations of the real (a) and imaginary (b) part of impedance when comparing simulation results and battery cell model after the refinement of the EIS-based architecture.

This result is a first significant example of exploitation of the proposed co-simulation framework for the identification/location of sources of uncertainty, which are hardly identifiable by means of experimental data only, and the successive informed refinement of the EIS-based system.

4.3. Using the Co-Simulation Framework for Software Validation

Considering that the simulation framework represents a complete model of the entire measurement system, it can be exploited for the studying and rapid development of novel circuits and impedance estimation algorithms, without spending time setting up a real demonstrator. This is very critical for the study and development of efficient excitation signals, mainly for the online EIS measurement approach. In this context, the co-simulation framework is exploited to analyze the effect of the crest factor optimization of multisine excitation signals on the accuracy of the final impedance estimate. To this end, the multisine signal was divided into three sub-bands following the multiband approach described in [26], then, each sub-band underwent the Van der Ouderaa crest factor optimization algorithm [39], creating a CF-optimized excitation pattern. The optimized and non-optimized multisine multiband patterns are used as input to the co-simulation framework, which implements the battery ECM of Figure 3. Figure 10 compares Cole–Cole plots obtained through the simulation framework with either the CF-optimized multiband or the non-optimized multiband multisine sequences, along with the ECM reference. The Cole–Cole plot derived from the sequence without CF-optimization shows an RMSE of 0.47 mΩ in module and 12.2 mrad in phase, while the Cole–Cole plot derived from the optimized sequence shows an RMSE of 0.40 mΩ in module and 4.9 mrad in phase. It is clear that the CF-optimized pattern leads to a lower dispersion of the impedance estimate around the ECM ideal response, translating into better accuracy. This study demonstrated the capabilities and potentialities of the co-simulation framework as a valuable representation of the real measurement system in all its aspects and non-idealities, allowing for fast validation of novel algorithms. As a further support, the framework has been extensively used in [26] for assessing the advantages of the multiband multisine approach. It is important to emphasize that such an analysis cannot be performed using a purely numerical simulator. Indeed, the effectiveness of crest factor optimization in concentrating the limited power of the excitation signal into the sine tones is inherently dependent on the practical implementation of the signal generator.

Figure 10.

Exloitation of the co-simulation framework for the comparison of different multiband multisine excitation patterns as proposed in [26]. Blue squares represent the impedance estimate when the excitation pattern is optimized following the VdO crest factor optimization, while green diamonds represent the impedance estimate when the excitation pattern does not undergo the same optimization algorithm. Red dots delineate the ideal expected impedance.

5. Experimental Validation of the Co-Simulation Framework

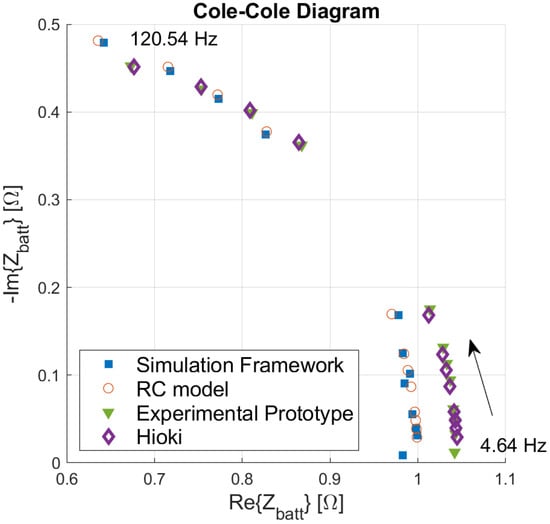

In this Section, the co-simulation framework is experimentally validated against the refined (see previous Section) EIS-based measurement prototype in operating conditions as well as the impedance estimates given by the benchtop reference instrument Hioki IM3590 (Hioki Corp., Nagano, Japan). Specifically, the experimental impedance measurements are carried out with the EIS sensor-node prototype described in Section 3 together with the FFT algorithm; both are presented and explained in detail in [25]. The hardware architecture of the prototype is modified according to the optimization solution explained in the previous Section and represented in Figure 7. To maximize the control of the test conditions, a first test was carried out using a simple RC circuit made of the parallel connection of a 1- resistor with a 1 mF capacitor as the physical device under test (DUT) connected to the measurement system, so as to de-embed the results from inaccuracies in the modeling of an actual battery cell. This reference DUT was used both in the co-simulation framework as well as in the experimental investigation.

The results of this test are reported in Figure 11. The simulation framework (blue squares) adequately predicts the ideal behavior of a pure RC parallel circuit, demonstrating the accuracy of the design for the HW/SW EIS architecture as well as the reliability of the results provided by the framework. This is in agreement with the previous test discussed in Section 3. The empirical data, provided by the reference instrument (purple diamonds) and by the experimental prototype (green triangles), slightly differ from the simulation results but are in very good mutual agreement, validating the prediction capability of the co-simulation framework. The discrepancy between simulation prediction and experimental data can be ascribed to the technological dispersion in the actual values of R and C parameters with regard to the nominal ones, as well as the presence of parasitic elements in the interconnection between the DUT and the EIS measurement system that are not taken into account in this iteration of the simulation framework. In addition, the accuracy limitations of the models for passive and active components exploited in the CAD should always be recalled when evaluating the origins of these residual discrepancies. For these reasons, the simulation would be expected to strongly further converge onto the empirical reference data if a “perfect” model of the R-C and all the HW components (including the access network) is implemented into the numerical framework.

Figure 11.

Comparison of impedance at test frequencies among the results predicted by the co-simulation framework including a pure RC parallel as DUT, the analytical values of the pure RC model, the estimates of the experimental prototype applied to the corresponding physical DUT, and the results provided by the Hioki reference instrument.

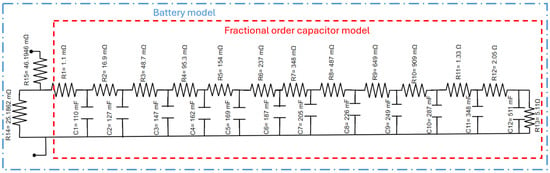

5.1. Battery Cell Model Based on Fractional-Order Capacitor

To fully test the accuracy of the results provided by the simulation framework as a digital representation of the EIS-based measurement system used to monitor battery cells, it is fundamental to implement in it an adequately accurate model of the battery cell. Fractional-order, CPE-based ECMs have been demonstrated to be highly accurate models already at reduced complexity levels [17,40,41]. Even a simple modified Randles model consisting of a resistor in series to the parallel connection of another resistor with a CPE demonstrated good prediction capabilities for the impedance of a lithium battery cell when compared to data collected from the real field [42]. For this reason, the simple battery cell model of Figure 3 is substituted with a more accurate version that incorporates a CPE, whose impedance is defined as follows [43]:

where is the fractional order and Q is the pseudo-capacitance [44].

Fractional-order circuits have found widespread use in different applications, such as biochemistry and medicine, to model diffusive phenomena like the double-layer effect at solid–liquid interfaces [45,46,47]. Detailed studies about the relationship between the EIS response and the physical phenomena occurring in the battery cell can be found in [48,49,50]. For the test reported in the following, the values of the two resistors and the parameters characterizing the CPE were experimentally extracted by means of measurements carried out with the Hioki Chemical Impedance Analyzer connected to a fully charged lithium-ion battery cell.

To implement the CPE in e-CAD software, either active or passive circuit components can be exploited, which allow one to reproduce the behavior of the CPE in a target frequency band. The active circuits involve the use of operational amplifiers and emerged as a promising method for developing tunable characteristics of the CPE, such as the order, the impedance value, and the bandwidth of operation [51,52]. However, the complexity of the circuit involved is a significant drawback of this approach [53]. For this reason, in this study, the behavior of the CPE is modeled by means of a purely passive circuit (Figure 12). Equation (5) is approximated by applying the continued fraction expansion (CFE) technique, which allows one to achieve a rational approximation of the complex function [45,54,55,56]. After the rational approximation, Equation (5) is re-formulated in order to derive the values of the components of an RC ladder topology named Cauer I [45,57]. By means of AC analyses, the approximation of the CPE demonstrated to be accurate within the frequency range of interest [4 Hz–120 Hz], with a maximum relative deviation from the ideal fractional model of less than 1%. The application of the CFE method and Cauer I was carried out by means of the code proposed in [58].

Figure 12.

Fractional-order ECM of a battery cell, including a CPE (highlighted in red) approximated by a ladder of purely passive elements in the frequency range [4 Hz–120 Hz].

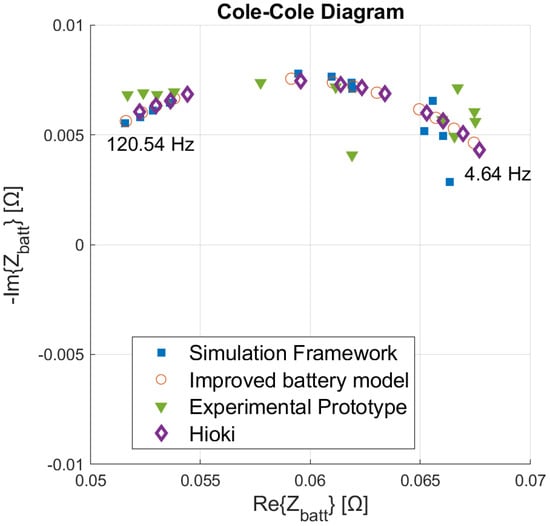

5.2. Results After Improving the ECM of the Cell

After the implementation of an improved battery cell ECM, it was possible to compare the predictions provided by the co-simulation framework with the experimental results obtained by the prototype of the EIS-based monitoring system applied to a real fully charged lithium-ion battery, as shown in Figure 13. Even in this case, the agreement between the co-simulation framework predictions and the ECM analytical values is high, with minimal discrepancies at the very low frequencies, which can be related to inaccuracies of the HW/SW design architecture and point out possible improvement directions. The simulation results are in good agreement also with the experimental prototype. The differences between the results of the simulation and the experimental prototype can be ascribed to non-idealities and parasitic effects not yet modeled in the co-simulation framework, as discussed in Section 3. For instance, connection impedances are not modeled in the simulation, while it is known that their effect is not negligible when monitoring devices with very low-value impedances, like the battery cells. Moreover, there is an inherent technological dispersion of the parameters of the EIS system with respect to those used in the models for the components employed in the CAD. To exploit the simulation framework within a digital twin, those dispersive effects should be experimentally evaluated, and their estimate should be added to the system model.

Figure 13.

Comparison of impedance at test frequencies among the co-simulation framework predictions, the enhanced battery model, the refined experimental prototype estimates, and the Hioki reference data.

As a further reference, the same battery cell was measured using the reference instrument Hioki IM3590, assessing the absolute accuracy of the results provided by the prototype and the framework. The enhanced fractional-order ECM of the battery cell (red circles) well fits the impedance shape provided by the reference instrument (purple diamonds), demonstrating the very good quality of the model.

In summary, this test supplements the previous ones, by demonstrating the capability of the co-simulation framework to predict the operation and results of a complete HW/SW EIS-based monitoring system applied to a commercial battery cell.

6. Conclusions

In this work, a numerical co-simulation framework was proposed for the design, analysis, and support during the validation of complex EIS-based measurement systems devoted to the online monitoring of battery cells. The framework allows for the analysis of the measurement system as a whole, taking into consideration the interrelationships between the hardware circuit parts and the algorithms implemented at the software level for the estimation of the impedance spectrum from the bare voltage/current measurements.

This approach makes the proposed simulation framework useful during both the design phase of novel systems and the experimental phase, where it can be used as a digital model of a preliminary prototype for supporting the performance assessment, and/or to better investigate and correctly locate sources of uncertainty within either the HW architecture or the SW algorithms and allow for a refinement of the design. Moreover, it can be used as the simulation core within the digital twin of the sensorized battery cell. The co-simulation framework was proposed without any relation to specific software, while an implementation using Cadence Virtuoso and Matlab was described and used to validate the approach. The implemented co-simulation framework can run on a standard workstation without particular issues, yet the simulations take approximately one hour at the maximum accuracy level, limiting this implementation to offline analysis. In order to employ the co-simulation framework in a digital twin, a simplified implementation should be realized.

To demonstrate the capabilities of the proposed framework, three different applications are presented and discussed. Firstly, the framework has been used to debug a sensor–node prototype based on the EIS architecture presented in [25]. This allowed for the identification of a subtle non-ideality in the hardware architecture that is highlighted as a small distortion effect in the HW simulation alone, but caused the signal processing algorithm to provide totally wrong estimates of the battery impedance. Then, the same co-simulation framework has been used as a design tool for the definition of a correction to the circuit architecture to cope with such a source of uncertainty, taking into consideration the effects on the software algorithms. Finally, the co-simulation framework has been used as a comprehensive model of the EIS-based sensor for studying the effect of crest factor optimization on the excitation pattern on the accuracy of the final impedance estimate, without the need to practically realize the demonstrator while taking into account all the HW/SW non-idealities.

In conclusion, when combined with an accurate model of the battery cell, like a fractional-order ECM based on CPEs, the co-simulation framework accurately predicted the experimental response of the refined prototype, in agreement with reference data provided by a gold-standard benchtop instrument. Further improvements of the co-simulation framework are needed to take into account other important elements of the EIS-based monitoring system, like the fixture for connecting the ASIC to the battery cell, which is affected by important non-ideality effects. Moreover, for very accurate results, the current co-simulation framework requires a refinement/calibration step to take into account the process variability and dispersion of the main circuit parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. and P.A.T.; methodology, N.L.; software, N.L.; validation, N.L. and R.R.; formal analysis, P.A.T.; investigation, N.L.; resources, M.C.; data curation, N.L. and R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, N.L.; writing—review and editing, M.C. and P.A.T.; visualization, N.L.; supervision, M.C. and P.A.T.; funding acquisition, M.C. and P.A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Electronic Components and Systems for European Leadership (ECSEL) Joint Undertaking (JU) under Grant number 101007247; the JU receives support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme and from Finland, Germany, Ireland, Sweden, Italy, Austria, Iceland, and Switzerland. The work was also co-funded by the European Union-NextGenerationEU- under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), Mission 4 Education and Research Component 2 from Research to Business, Investment 1.1, Call for Proposals PRIN 2022 titled “A Cyber-Physical System for In-operando Monitoring and Diagnostics of Battery Cells” project code 2022KB2HZM 002 CUP J53D23000780006.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hannan, M.A.; Hoque, M.M.; Hussain, A.; Yusof, Y.; Ker, P.J. State-of-the-Art and Energy Management System of Lithium-Ion Batteries in Electric Vehicle Applications: Issues and Recommendations. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 19362–19378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzetti, S.; Mariasiu, F. Electric vehicle battery technologies: From present state to future systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 51, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.F.; Mei, J.; Zhu, Y.R. Key strategies for enhancing the cycling stability and rate capacity of LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 as high-voltage cathode materials for high power lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2016, 316, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrosati, B.; Garche, J. Lithium Batteries: Status, Prospects and Future. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 2419–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramilli, R.; Crescentini, M.; Traverso, P.A. Sensors for Next-Generation Smart Batteries in Automotive: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Automotive (Metroautomotive), Bologna, Italy, 1–2 July 2021; pp. 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.L.; Cano, Z.; Yu, A.; Lu, J.; Chen, Z. Automotive Li-Ion Batteries: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2019, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masias, A.; Marcicki, J.; Paxton, W. Opportunities and Challenges of Lithium Ion Batteries in Automotive Applications. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xu, L.; Lin, X.; Pecht, M. Battery Lifetime Prognostics. Joule 2020, 4, 310–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Pan, D.; Chen, C. Intelligent Prognostics for Battery Health Monitoring Using the Mean Entropy and Relevance Vector Machine. Syst. Man, Cybern. Syst. IEEE Trans. 2014, 44, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallemans, N.; Widanage, W.D.; Zhu, X.; Moharana, S.; Rashid, M.; Hubin, A.; Lataire, J. Operando electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and its application to commercial Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2022, 547, 232005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Widanage, W.D.; Yang, S.; Liu, X. Battery digital twins: Perspectives on the fusion of models, data and artificial intelligence for smart battery management systems. Energy AI 2020, 1, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroe, D.I.; Swierczynski, M.; Stroe, A.I.; Knap, V.; Teodorescu, R.; Andreasen, S. Diagnosis of Lithium-Ion Batteries State-of-Health based on Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Technique. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 14–18 September 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barai, A.; Uddin, K.; Dubarry, M.; Somerville, L.; Mcgordon, A.; Jennings, P.; Bloom, I. A comparison of methodologies for the non-invasive characterisation of commercial Li-ion cells. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2019, 72, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meddings, N.; Heinrich, M.; Overney, F.; Lee, J.S.; Ruiz, V.; Napolitano, E.; Seitz, S.; Hinds, G.; Raccichini, R.; Gaberscek, M.; et al. Application of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy to commercial Li-ion cells: A review. J. Power Sources 2020, 480, 228742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsoukov, E.; Macdonald, J.R. Impedance Spectroscopy: Theory, Experiment, and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Radogna, A. Towards Ultra-fast Time-based Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy of Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on IC Design and Technology (ICICDT), Tokyo, Japan, 25–28 September 2023; p. xxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescentini, M.; De Angelis, A.; Ramilli, R.; De Angelis, G.; Tartagni, M.; Moschitta, A.; Traverso, P.A.; Carbone, P. Online EIS and Diagnostics on Lithium-Ion Batteries by Means of Low-Power Integrated Sensing and Parametric Modeling. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Angelis, A.; Ramilli, R.; Crescentini, M.; Moschitta, A.; Carbone, P.; Traverso, P.A. In-situ Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy of Battery Cells by means of Binary Sequences. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), Glasgow, UK, 17–20 May 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gupta, K.; Silva, C.D.; Liu, T.; Zheng, Z.H.; Zhang, W.P.; Lammeren, J.P.V.; Bergveld, H.J.; et al. IC for online EIS in automotive batteries and hybrid architecture for high-current perturbation in low-impedance cells. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), San Antonio, TX, USA, 4–8 March 2018; pp. 1922–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramilli, R.; Romano, P.; Giuliano, M.; Li Pira, N.; Crescentini, M.; Traverso, P.A. On the feasibility of EIS-Based Online Battery Monitoring Assessed in Automotive Grade Environment. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Automotive (MetroAuto), Parma, Italy, 25–27 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Arbizzani, C.; Kjelstrup, S.; Xiao, J.; Xia, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Belharouak, I.; Zawodzinski, T.; Myung, S.T.; et al. Good practice guide for papers on batteries for the Journal of Power Sources. J. Power Sources 2020, 452, 227824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemiss, L.; Rennie, A.; Sayers, R.; West, A. Characterisation of batteries by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Pulido, Y.; Blanco, C.; Anseán, D.; Garcia, V.; Martin, F.J.; Valledor, M. Determination of suitable parameters for Battery Analysis by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Measurement 2017, 106, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallemans, N.; Howey, D.; Battistel, A.; Mantia, F.L.; Widanalage, D.; Hubin, A.; Lataire, J. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Beyond Linearity and Stationarity. In ECS Meeting Abstracts; The Electrochemical Society, Inc.: Pennington, NJ, USA, 2024; p. 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramilli, R.; Santoni, F.; Angelis, A.; Crescentini, M.; Carbone, P.; Traverso, P.A. Binary Sequences for Online Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy of Battery Cells. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramilli, R.; Lowenthal, N.; Crescentini, M.; Traverso, P.A. Multiband Multisine Excitation Signal for Online Impedance Spectroscopy of Battery Cells. Batteries 2025, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, E.; Clark, D.; Gollapalli, R.; Russ, S.; Kerrigan, B. A System on Chip design for fast time domain impedance spectroscopy. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 60th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Boston, MA, USA, 6–9 September 2017; pp. 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.A.; Wu, W.J.; Wei, C.L.; Darling, R.B.; Liu, B.D. Novel 10-Bit Impedance-To-Digital Converter for Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Measurements. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2017, 11, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, G.; Ria, A.; Bruschi, P.; Gerevini, L.; Vitelli, M.; Molinara, M.; Piotto, M. An ASIC-Based Miniaturized System for Online Multi-Measurand Monitoring of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batteries 2021, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciani, G.; Ramilli, R.; Romani, A.; Tartagni, M.; Traverso, P.; Crescentini, M. A miniaturized low-power vector impedance analyser for accurate multi-parameter measurement. Measurement 2019, 144, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Qin, W.; Ye, J.; Ma, S.; Sheng, Y.; Hong, Z.; Xu, J. A 14-Cell Battery Monitoring AFE with 1mV Total Measurement Error and Integrated Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conference (CICC), Boston, MA, USA, 13–17 April 2025; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Pan, J.; Chen, Q.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, K.; Zhao, M.; Song, S. An Adaptive Input Voltage Current-Balanced Analog Frontend System for Multiple Cell Li-ion Battery Electrochemical Impedance Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), London, UK, 25–28 May 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Ling, Q.; Yang, M.; Bao, C.; Zhong, X.; Wang, P. A High-Precision and Fast Measurement Method for Li-Ion Battery EIS. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, N.; Ramilli, R.; Crescentini, M.; Traverso, P.A. Development of a numerical framework for the analysis of a multi-tone EIS measurement system. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Automotive (MetroAutomotive), Modena, Italy, 28–30 June 2023; pp. 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cadence. Product Version 6.1 June 2006, Spectre/RF Matlab Toolbox Application Note; Cadence Design Systems: San Jose, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cadence. LNA Design Using SpectreRF Application Note; Cadence Design Systems: San Jose, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Varnosfaderani, M.A.; Strickland, D. Online impedance spectroscopy estimation of a dc–dc converter connected battery using a switched capacitor-based balancing circuit. J. Eng. 2019, 2019, 4681–4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegaro, L. Electrical Impedance: Principles, Measurement, and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ouderaa, E.; Schoukens, J.; Renneboog, J. Peak factor minimization of input and output signals of linear systems. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 1988, 37, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Villanueva, J.A.; Rodríguez-Iturriaga, P.; Parrilla, L.; Rodríguez-Bolívar, S. A compact model of the ZARC for circuit simulators in the frequency and time domains. AEU Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2022, 153, 154293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagneur, L.; Driemeyer-Franco, A.; Forgez, C.; Friedrich, G. Modeling of the diffusion phenomenon in a lithium-ion cell using frequency or time domain identification. Microelectron. Reliab. 2013, 53, 784–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, P.; de Angelis, A.; Marracci, M.; Tellini, B.; Traverso, P.A.; Crescentini, M.; Brunacci, V.; Santoni, F.; Moschitta, A. Modeling the Battery Pack in an Electric Car Based on Real-Time Time-Domain Data. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), Glasgow, UK, 20–23 May 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Agambayev, A.; Patole, S.; Farhat, M.; Bagci, H.; Salama, K. Ferroelectric Fractional-Order Capacitors. ChemElectroChem 2017, 4, 2807–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoulea, S.; Psychalinos, C.; Elwakil, A.S. Simple Implementations of the Cole-Cole Models. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd Novel Intelligent and Leading Emerging Sciences Conference (NILES), Giza, Egypt, 24–26 October 2020; pp. 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirimokou, G. A systematic procedure for deriving RC networks of fractional-order elements emulators using MATLAB. AEU Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2017, 78, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gateman, S.M.; Gharbi, O.; Gomes de Melo, H.; Ngo, K.; Turmine, M.; Vivier, V. On the use of a constant phase element (CPE) in electrochemistry. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2022, 36, 101133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhang, K.; Ravey, A.; Gao, F.; Miraoui, A. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis for Fractional-Order Modeling of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energies 2016, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Evans, T.A.P.; Weddle, P.J.; Colclasure, A.M.; Chen, B.R.; Tanim, T.A.; Vincent, T.L.; Kee, R.J. Extracting and Interpreting Electrochemical Impedance Spectra (EIS) from Physics-Based Models of Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171, 050512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurilli, P.; Brivio, C.; Wood, V. On the use of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy to characterize and model the aging phenomena of lithium-ion batteries: A critical review. J. Power Sources 2021, 505, 229860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Choi, J. Impedance Spectroscopy-Based Parameter Identification of Lithium-Ion Batteries for Degradation Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2020 Korean Society of Industrial and Applied Mathematics, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 8–9 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Swief, R.; El-Amary, N.H.; Kamh, M. A novel implementation for fractional order capacitor in electrical power system for improving system performance applying marine predator optimization technique. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 1543–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semary, M.S.; Fouda, M.E.; Hassan, H.N.; Radwan, A.G. Realization of fractional-order capacitor based on passive symmetric network. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 18, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoulea, S.; Psychalinos, C.; Elwakil, A.S. Simple implementations of fractional-order driving-point impedances: Application to biological tissue models. AEU Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2021, 137, 153784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, G.; Halijak, C. Approximation of Fractional Capacitors (1/s)1/n by a Regular Newton Process. IEEE Trans. Circuit Theory 1964, 11, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Moore, K.L. Discretization schemes for fractional-order differentiators and integrators. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Fundam. Theory Appl. 2002, 49, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koton, J.; Kubanek, D.; Vrba, K.; Shadrin, A.; Ushakov, P. Universal voltage conveyors in fractional-order filter design. In Proceedings of the 2016 39th International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP), Vienna, Austria, 27–29 June 2016; pp. 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagonotte, P.; Soulier, F.; Thomas, A.; Martemianov, S. Classified Foster and Cauer Circuits for the Choice of a Model. Adv. Theor. Comput. Phys. 2023, 5, 324–331. [Google Scholar]

- cpe2rc. MATLAB Central File Exchange. 2023. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/134077-cpe2rc (accessed on 15 November 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).