Abstract

A series of diverse substituted 5-methyl-isoxazole-4-carboxylic acid amides, imide and esters in which the benzene ring is mono or disubstituted was prepared. Spectroscopic and conformational examination was investigated and a new insight involving steric interference and interesting downfield deviation due to additional diamagnetic anisotropic effect of the amidic carbonyl group and the methine protons in 2,6-diisopropyl-aryl derivative (2) as conformationaly restricted analogues Leflunomide was discussed. Individual substituent electronic effects through π resonance of p-substituents and most stable conformation of compound (2) are discussed.

1. Introduction

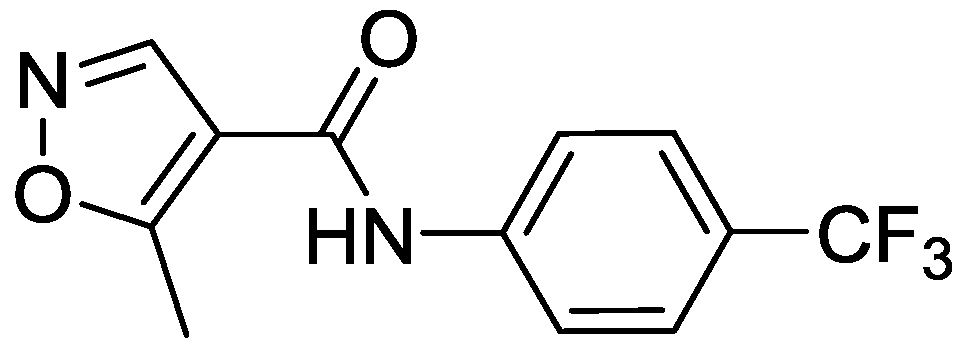

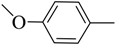

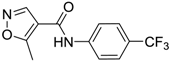

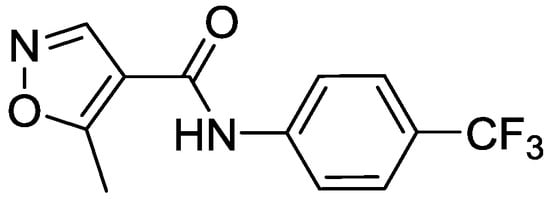

It is known that isoxazole derivatives show diverse biological activity and are known for their potential use against a broad array of diseases including infectious diseases, parasitic infection and for the area of oncology therapeutics [1]. For example, Leflunomide (Avara), is an immunomodulator which is used to treat the symptoms associated with rheumatoid arthritis RA and psoriatic arthritis (Figure 1) [2]. Leflunomide, as a small, low molecular-weight isoxazole derivative, is one of the most potent but associated with serious side effects [3].

Figure 1.

Leflunomide (Avara).

The importance of the amide group for living organisms can be correlated to some of its chemical properties such as planarity [4], relatively high barrier of rotation around the C–N bond, and its hydrogen bonding donor and acceptor properties. These are the key factors related to determining the conformations of protein-protein complexes, enzymes and other biopolymers like DNA and RNA. Studies on amide derivatives have led to many speculations [5]. As NMR provides one of the most sensitive biophysical techniques, NMR studies and utilization of chemical shift parameters are increasingly being used to tackle more challenging biological problems. It is well known that the chemical shift depends on electronic and molecular environments [6].

A high rotational barrier due to the partial double-bond character of tertiary amides leads to the geometric and magnetic nonequivalence of the nitrogen-attached groups even when both are the same. Amide and related functional groups are planar and exhibit E/Z (Rotational) isomerism [7].

There is a known preference of N-aryl amides to exist in an E (Ar and C=O anti) geometry. The N–Ar rotation barrier of a 2-phenylacetamide analog was reduced from 31 kcal mol−1 in the precursor to 17 kcal mol−1 in the enolate. This dramatic barrier reduction has implications of both N–Ar and amide C–N rotations [8].

Functional groups with ‘Nsp2–Ar’ as N-aryl amides often prefer twisted geometries. Both the geometry of the N–Ar bond and its rotation barrier are crucial features in areas as diverse as enzyme/substrate binding [9,10,11].

Selectively deshielded aromatic protons in some ortho-substituted acetanilides [12] exhibit signals at unusually low fields for the aromatic proton adjacent to the acetamido group and for the amido proton itself.

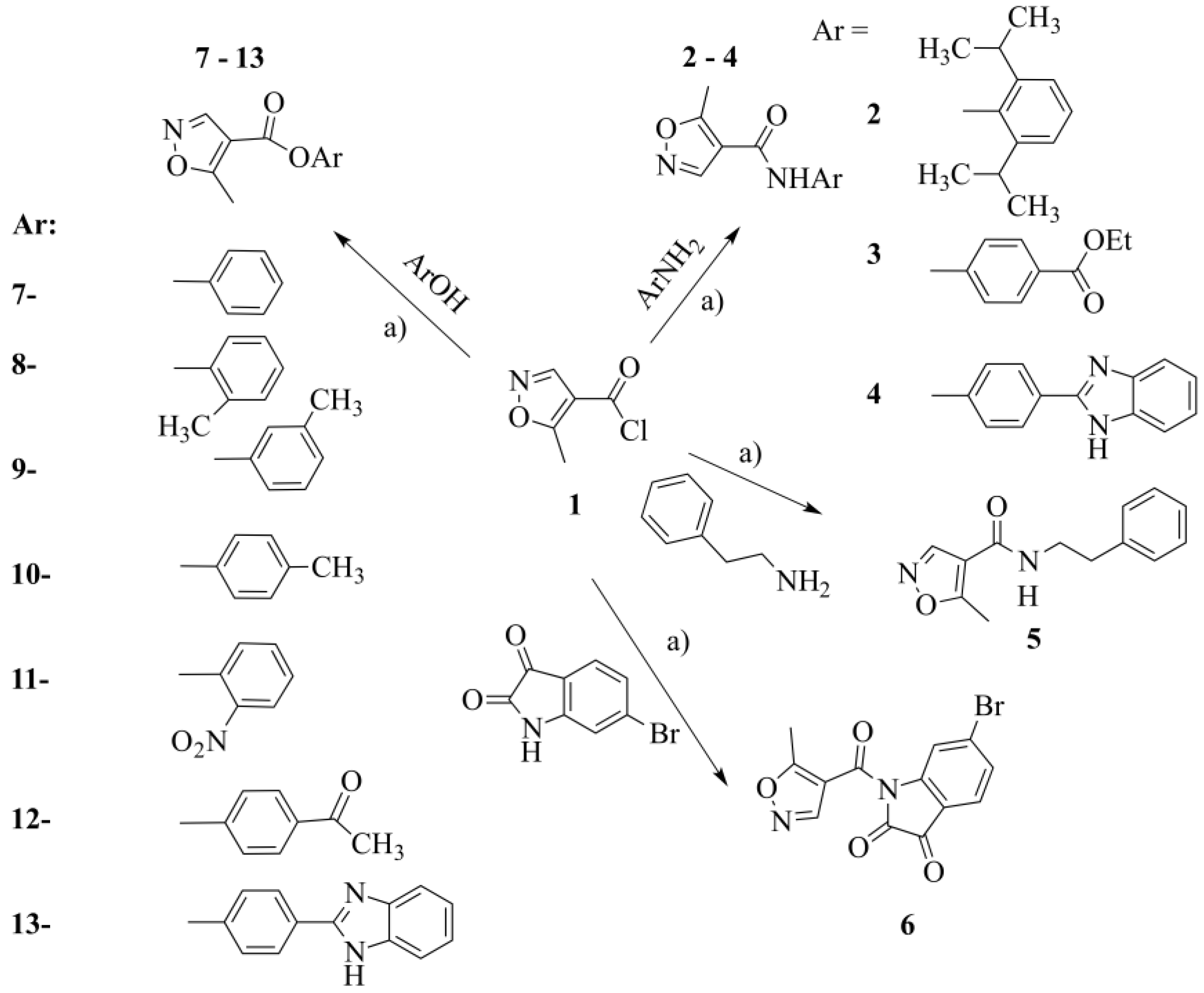

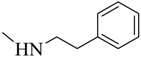

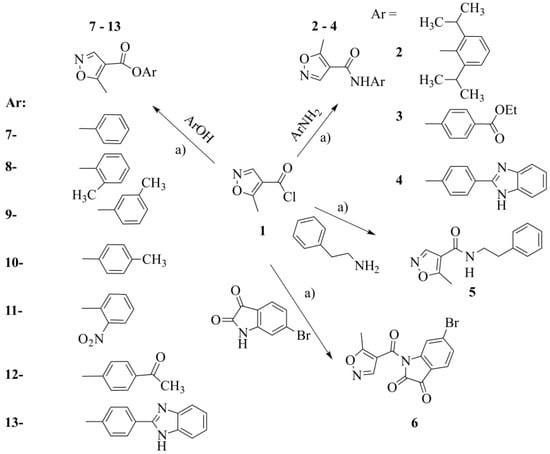

Based on these facts, in this study, we synthesized novel Leflunomides, which are based on bioisosterism [13], by changing the substitution pattern at the 4-position of isoxazole ring of Leflunomide to: confer different conformations and electronic environment at the amide group that would exert some effect on the lipophilicity and enhance the activity of the target molecules. New substituents are applied, like for example replacing the lipophilic p-CF3 group with the other electron withdrawing group, adding the electron donating group at either ortho or para position, replacing the entire ring with phenylethyl ring, or adopting hybrid pharmacophore like isatin and benzimidazole nucleus or isosteric replacement of amide by ester (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route for novel Leflunomide derivatives.

As part of our research aiming at the synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of diverse functionalized aryl amide and isosteric analogues of leflunomide, new compounds have been investigated for further structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies. Our first publication in this series indicated that many Leflunomide analogues showed better antifibrotic activity than Leflunomide [14].

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthetic Chemistry

In this study, the starting compounds assembled by coupling the key intermediate: 5-methylisoxazole-4-carbonyl chloride 7 and anilines, aryl ethylamine, isatin or phenols, in dichloromethane (DCM) using trimethylamine (TEA) as base [15] to afford the final products 2–13 in moderate to high yields (40–91%) (Scheme 1, Table 1). The desired benzimidazole derivative for preparation of 4 and 13 was obtained in a good yield starting from heating o-phenylenediamine (OPDA) with p-amino ethylbenzoate in the presence of a strong dehydrating agent such as polyphosphoric acid (PPA) [16] or with 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde in dimethyl formamide (DMF) using sodium metabisulfite as oxidizing agent [17], respectively. The structures of compounds 2–13 were approved on the basis of spectral data (IR, mass and NMR) and elemental analysis. All spectral data were in good agreement with the proposed structures.

Table 1.

Synthesis of 5-methyl-4-isoxazole derivatives (2–13).

2.2. Spectroscopic Examination

Dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 (DMSO) was the solvent of choice, not only for its excellent solvation properties, but also for the fact that amide proton chemical shifts in DMSO were clearly separable from the aromatic region. The downfield chemical shifts in DMSO (about 12.8 ppm in case of 2–5) are undoubtedly due to hydrogen bonding of the amide proton with solvent. The substituents exert relatively small influences on the δ of the N–H proton as the anisotropy effect depends on the spatial arrangement, but it is independent of the nuclei being observed [18].

The chemical shift of C5 CH3 and C3 H in 1H-NMR and C4 C=O in 13C-NMR having nearly the same chemical shift value meaning a similar special arrangement like 5-Methylisoxazole-4-carboxylic acid [19]. Due to planar delocalization, 13C-NMR chemical shifts for the amidic CON indicates (amidic sp2 carbon near 188 Hz) due to electronic interactions and steric effects over these atoms.

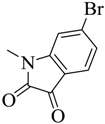

Amides 2–4 and 6 exert the same sign for angle Ө between carbonyl and isoxazole or aromatic ring like leflunomide (cis relation between isoxazole and aromatic rings). While, 5 and 7–13 exert one opposite signs (trans relation between isoxazole and aromatic rings) as shown in (Table 2). In compound 6, N is imidic so the lone pair of electrons are delocalized over 2 C=O groups and thus the aryl protons are more deshielded.

Table 2.

Dihedral angle between C=O and phenyl ring, and Dihedral angle between C–O and isoxazole ring.

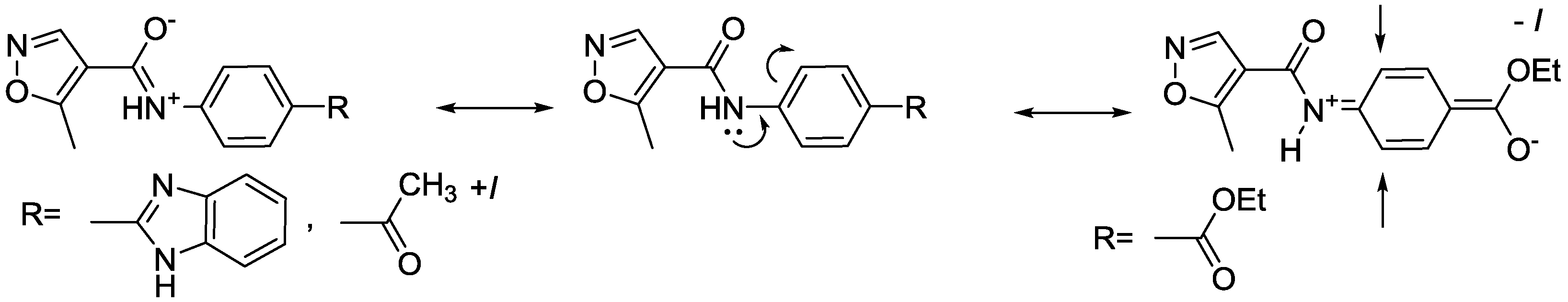

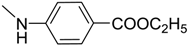

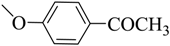

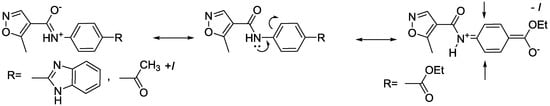

The contributions for different anilide groups in the surroundings of our system is relative to corresponding chemical shift- for Hbase of acetanilide. For example, compound 3 which has substitution in p-position creates a push and pull effect which leads to more relevant long-range effect on the chemical shift and makes extra stability of the negative charge due to extended resonance (highlighted by arrows, as O atom stabilize –ve charge more than N atom in indicated R groups). As the presence of conjugation normally leads to upfield shift of o-protons (Figure 1). While in 4 the o-protons is more deshielded due to the –I effect of the positively charged nitrogen. The added para- group should not significantly affect either barriers or rotamer populations, and it is present simply as an analogue of leflunomide (Figure 2). It is reported that the 1H chemical shift is not as sensitive as 15N or 13C to conjugation, and presence of the amide group at the end of the conjugation in this case can have the higher hand in effect on the 1H chemical shift value.

Figure 2.

Effect of conjugation and para-substitution on the barrier or rotamer population.

Structures 3, 4, 10, 12 and 13 have magnetically equivalents p-substituted phenyl with high ortho coupling (J value between 8 and 8.4 Hz) like leflunomide. While the others have magnetically non-equivalent phenyl or substituted phenyl. Structure 11 contains NO2 group which may have a small anisotropic effect similar to that of C=O group in Structure 12, with a deshielding region in the plane of aromatic ring. The ortho proton(s) relative to nitro or acetyl group is strongly downfield, in part due to this interaction.

Structure 2 has symmetrically ortho disubstitited but contains magnetically non-equivalent meta aryl protons (aromatic protons is away from the carbonyl, and is shifted downfield by 0.3 ppm which is generally proposed by dispersion interactions. In addition, the 2-ortho di-isopropyl methine protons are non-equivalent (no plane of symmetry); chemical shift is indicated at two multiplets at 4.84 and 5.15. The spectrum shows how dramatic the effect can be, indicating a quite large downfield shift relative to the corresponding known practical range or calculated values. The prediction of chemical shift of the isopropyl CH group was calculated using the Curphy-Morrison Additivity Constants for Proton NMR [20].

The predicted 1H-NMR chemical shift = 1.55 + 1.45 = 3 ppm. The actual value was 4.84–5.15. So in case of the upfield value, ∆δ = 4.84 − 3 = 1.84, while in case of the downfield value, ∆δ = 5.15 − 3 = 2.15. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first spectacular report of such deviation and further study in this area is needed. In addition, examination of anticancer activity of compound 2 using Swiss Target Prediction software [21] indicated a very high susceptibility to cytochrome P450.

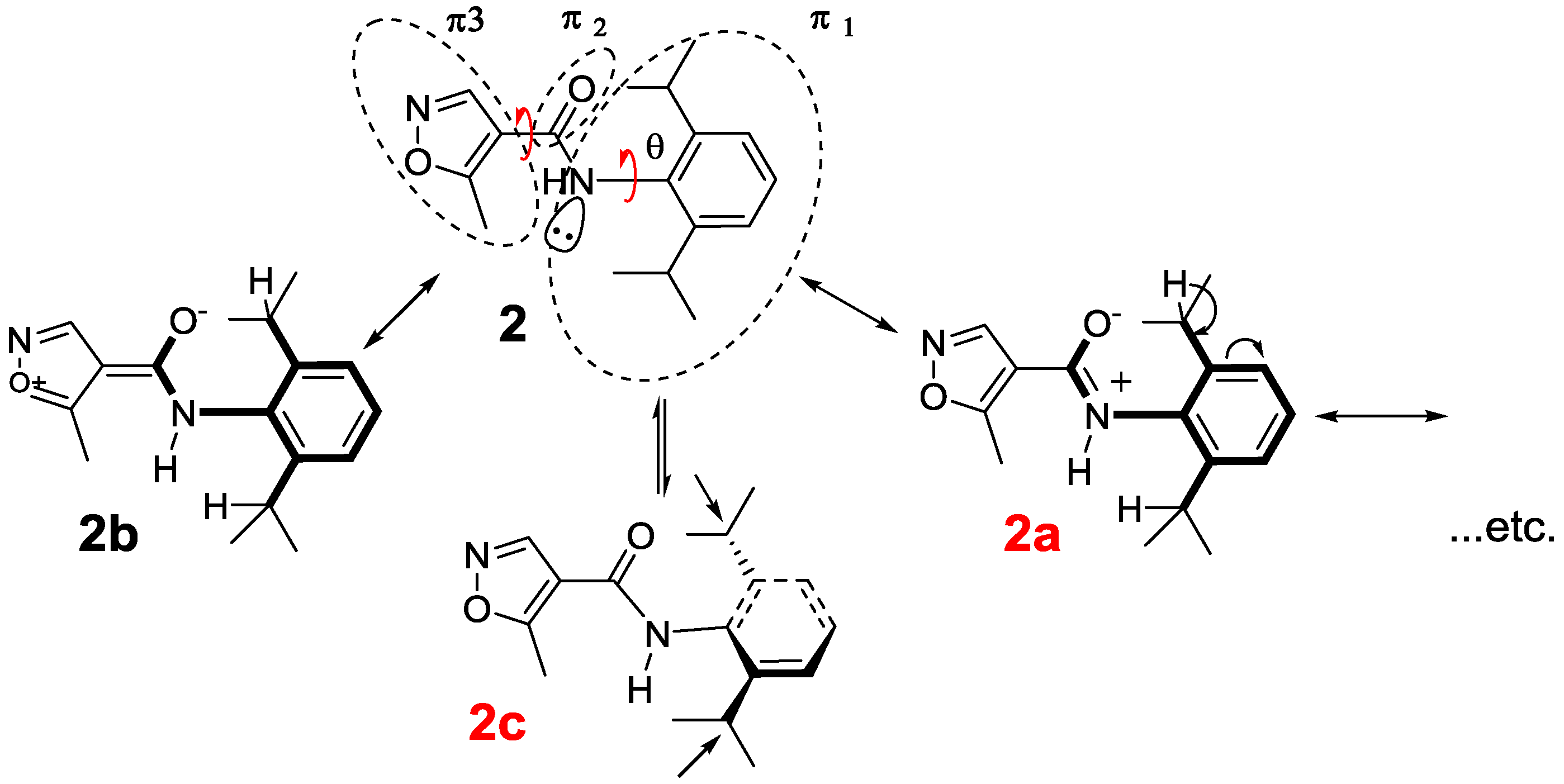

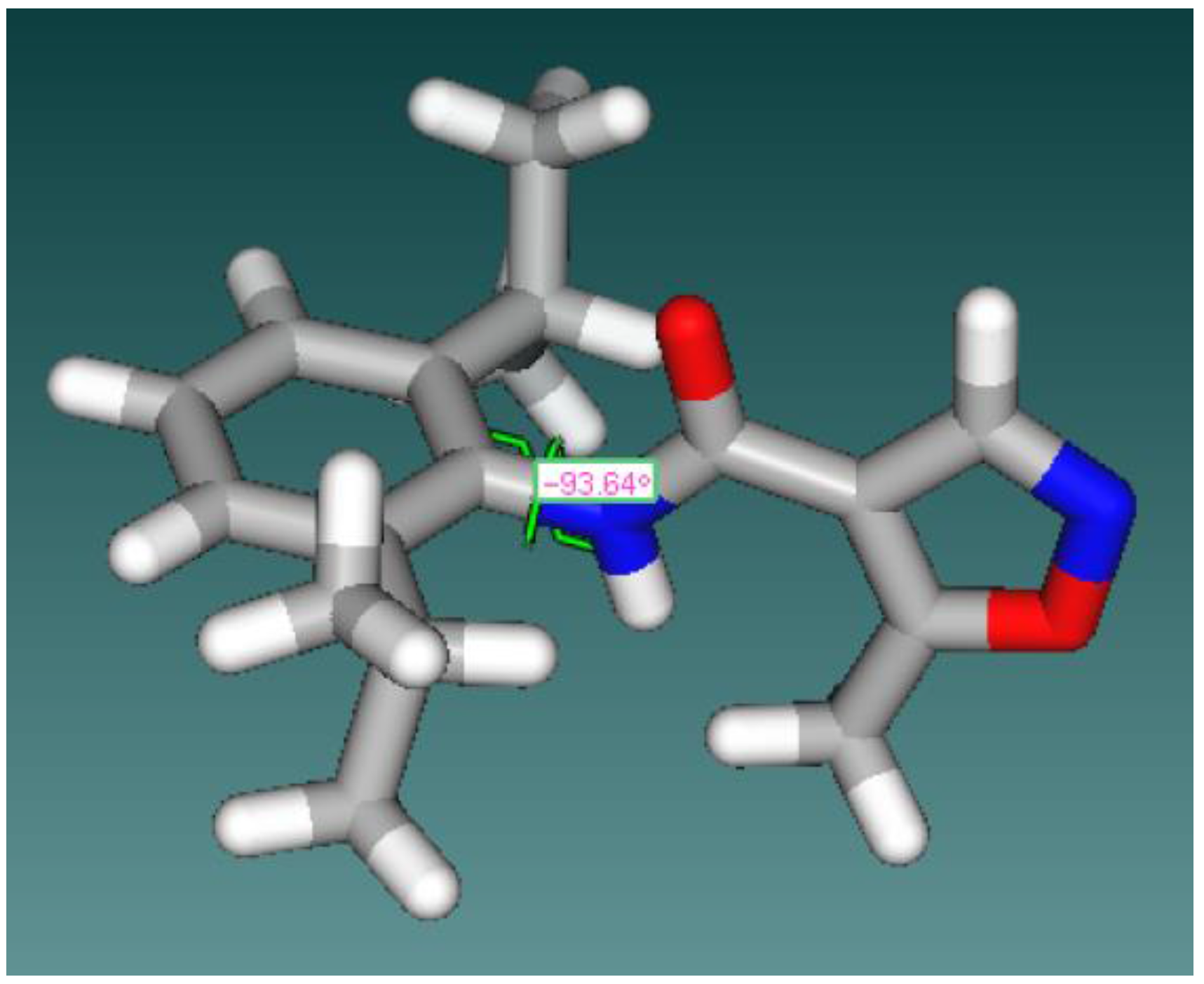

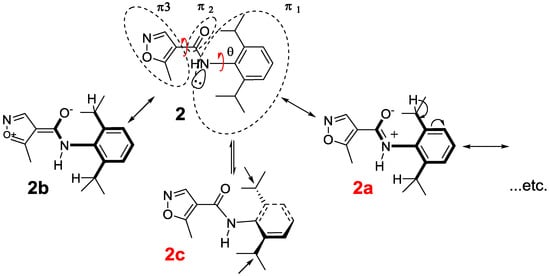

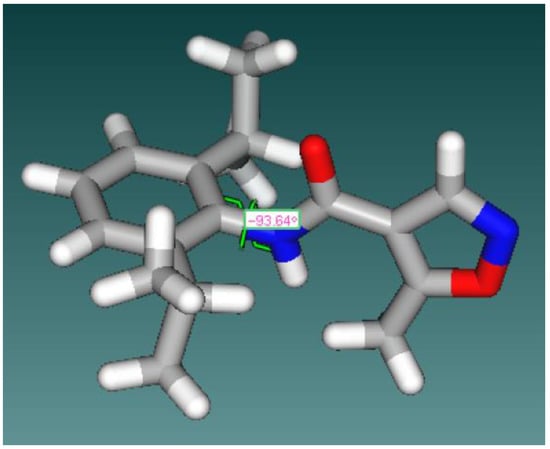

The secondary amide is adopting trans conformation, this means more rigidity and conformational stability [22] Conformational analysis of compound 2 using Marven Suit software (Marvin 16.7.18.0, 2016, ChemAxon, http://www.chemaxon.com) showed dihedral angle between the plane of the aromatic ring and C=O is −93.64°.

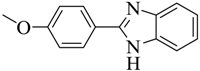

The compound (2) has three different systems. The 2 can be conjugated with 1 as anilide (2a), loss of conjugation between nitrogen and aryl leads to the fact that the compound behaves as amide rather than anilide due to the bulky ortho 2,6-diisopropyl groups, or 3 as carbonyl moiety (2b), very unstable, has possibility of diverse dipolar interactions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Diverse possible dipolar interaction (2a and 2b) and the most stable conformation with planar carbonyl group ┴ the o-diisopropyl phenyl ring (2c).

In addition, the relatively 1H-NMR deshielded methine proton on 3° isopropyl carbon (indicated by →) in 2 cannot be explained by co-planarity or private dipolar structure 2a & 2b or by hyperconjugation of methine proton as indicated by curved arrow in 2a. The diamagnetic anisotropy of the conjugated plannar carbonyl group which is nearly perpendicular to the aromatic ring, as indicated by 2c which creates two additive environments of diamagnetic anisotropy, is in close contact to the 2 methine protons. Conformational analysis of compound 2 using 3D molecular model examination resulted in a better insight (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

3D structure of compound 2, showing the dihedral angle between C=O group and the benzene ring.

The very small difference of Ө angle 3.46° is responsible for the non-equivalence and difference in chemical shift of the two methine protons. The added ortho-diisopropyl groups serves as the lock by raising the N–Ar rotation barrier; and is proposed [23,24]. Therefore, individual substituent electronic effects through well-defined π–resonance units indicate that these units behave both as isolated and as conjugated fragments, depending on the substituents.

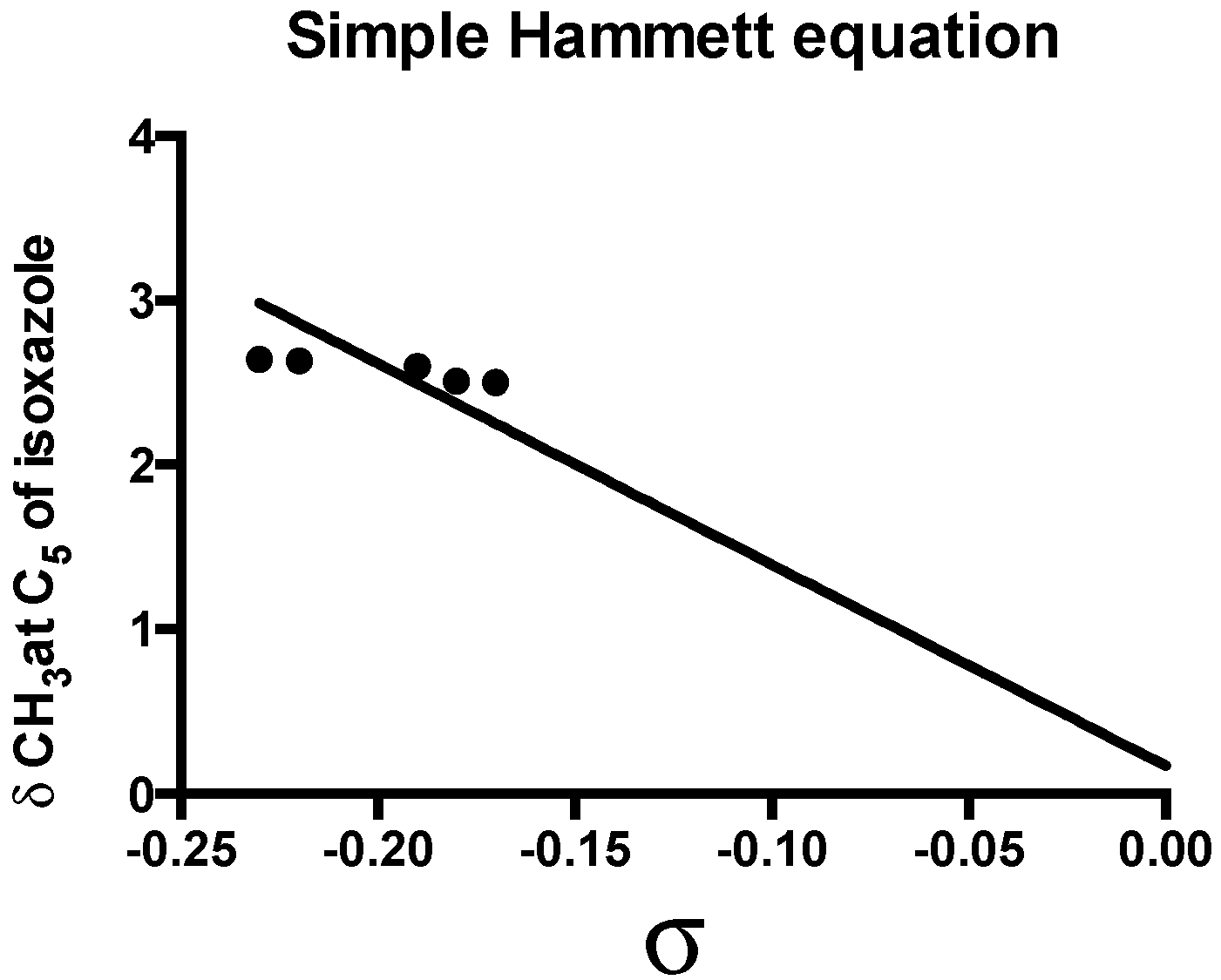

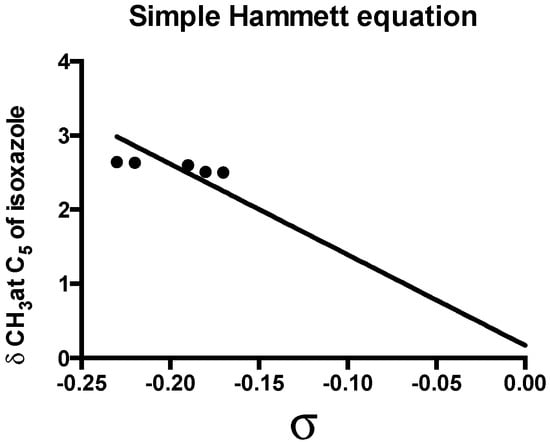

Linear free energy relationships (LFER) were applied to the 1H-NMR spectral data of compounds 7–13 and IR spectral. A variety of substituents were employed for phenyl substitution and fairly good correlations were obtained using the simple Hammett and the Hammett–Taft dual substituent parameter equations [25,26]. The correlation results of the substituent induced 1H-NMR chemical shifts (SCS) of the CH3 at C5 isoxazole spins indicated different sensitivity with respect to electronic substituent effects. The following equation was applied.

S = ρσ + h

S is substituent dependent value (absorption frequency in cm−1, or chemical shift), ρ is the proportionality constant, σ is Hammett constant, h is the intercept (Table 3 and Figure 5).

Table 3.

Summary of results of simple Hammett equation fit.

Figure 5.

Hammett equation fit of the chemical shift of CH3 at C5 of isoxazole of compounds 7–12.

Detailed studies of this new observation with other o-substituted anilines and conformational determination is essential for biological correlations.

2.3. Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant activity of the final compounds 2–13 had been tested using L-ascorbic acid as reference assay in triplicate and average values were considered. The ABTS antioxidant assay [26] is applied as follows:

- 900 µL of (ABTS/MnO2 mix) was transferred to cuvette of spectrophotometer (SPEKOL11) and the absorbance (Acontrol) was measured at 734 nm against blank (methanol/phosphate buffer (1:1); reading ca. 0.2.

- 900 µL of mix was transferred to 100 µL standard ascorbic acid in cuvette and the absorbance was measured against blank (methanol/phosphate buffer (1:1) + 100 µL of ascorbic acid).

- 900 µL of mix to 100 µL of sample was transferred in cuvette and the absorbance (Atest) was measured against blank (methanol/phosphate buffer (1:1) + 100 µL of sample).

- % Inhibition was calculated using the following equation; % Inhibition = ([Acontrol − Atest]/Acontrol) × 100.

The results of the preliminary qualitative antioxidant screening of 21 compounds are listed in (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of the preliminary qualitative antioxidant screening.

Most of compounds beside Leflunomide showed moderate antioxidant activity. In general:

- Changing the amide linkage with ester linkage decreased the antioxidant activity more than most of the amide Leflunomide analogues.

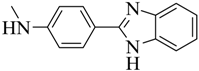

- The benzimidazole derivatives of Leflunomide 4 and 13 showed higher % of inhibition of radical production than Leflunomide. Benzimidazole derivatives are considered to be good chelating agents [27,28], therefore, our finding can pave the way for further in vivo studies of compounds 4 and 13. In addition, this also shows the linkage between antifibrotic and antioxidant activity which has been reported in literature [29].

3. Experimental Section

General

Melting points were recorded using a Mel-Temp 3.0 melting point apparatus (Barnstead, Dubuque, IA, USA). IR spectra were performed on a Mattson 5000 FT-IR spectrometer (Fremont, CA, USA) in KBr disks at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Mansoura University. 1H and 13C-NMR spectra were obtained using a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer (Billerica, MA, USA) and DMSO-d6 as solvent. Mass spectra (m/z) were obtained from the Cairo University Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, Cairo, Egypt. High resolution mass (HRMS) were obtained from Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 30303-3083, USA. Elemental analysis was done at the Microanalysis Centre, Cairo University, Egypt from a CHNS Elemental Analyser. The major chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and Fluka (St. Louis, MO, USA).

5-Methylisoxazole-4-carbonyl chloride (1). [18,30]. Thionylchloride (3.53 g, 0.0278 mol) was added to a solution of 5-Methylisoxazole-4-carboxylic acid (2.7 g, 0.0185 mol) in anhydrous dichloromethane (50 mL) with catalytic drops of DMF. The reaction was heated under reflux for 12 h then followed by removing the solvent under reduced pressure. DCM (20 mL) was added and evaporated 3 times to produce a brown oil that was used directly in the next step.

General procedure for the synthesis of compounds (2–13). To a stirred solution of the amines or phenols (0.0024 mol) and trimethylamine (0.0025 mol) in dichloromethane (40 mL), 5-methylisoxazole-4-carbonyl-chloride (0.003 mol) was added dropwise at 0–5 °C. Then, reaction mixture was refluxed at 40 °C for 24 h. After completion of the reaction as indicated from the TLC, the solvent was evaporated under vacuum and the residue was purified using preparative TLC.

N-(2,6-Diisopropylphenyl)-5-methylisoxazole-4-carboxamide (2). Using 2,6-diisopropylaniline. IR (KBr) υ/cm−1: 3268, 1606, 1532; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 1.31 (br t, 12H), 2.64 (s, 3H), 4.84–5.15 (2q, 2H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (s, 1H), 8.77 (s, 1H), 12.8 (br s, 1H, D2O exchangeable); m/z: Calcd. for C17H23N2O2: 287.1754; Found: 287.1756 [M + H]+; Anal. Calcd. For C17H22N2O2 (286.37): C, 71.30; H, 7.74; N, 9.78, Found: C, 71.23; H, 7.79; N, 9.75.

Ethyl 4-(5-methylisoxazole-4-carboxamido)benzoate (3). Using ethyl aniline p-carboxylate. IR (KBr) υ/cm−1: 3307, 1713, 1639, 1547; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 1.25 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 2.64 (s, 3H), 4.18–4.12 (m, 2H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.64 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H) Compare with previous 2a, 8.77 (s, 1H), 12.8 (br s, 1H, D2O exchangeable). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): δ 24.52, 46.06, 61.27, 110.36, 119.91, 120.23, 130.76, 131.41, 141.99, 166.75, 174.26, 187.71; ESI-HRMS: m/z Calcd. For C14H15N2O4: 275.1105; Found: 275.1107 [M + H]+. Anal. Calcd. For C14H14N2O4 (274.27): C, 61.31; H, 5.14; N, 10.21, Found: C, 61.35; H, 5.24; N, 10.11.

N-(4-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)phenyl)-5-methylisoxazole-4-carboxamide (4). Using 4-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)aniline. IR (KBr) υ/cm−1: 3420, 3345, 1602, 1548; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 2.51 (s, 3H), 6.57 (s, 2H), 7.23–7.25 (m, 1H), 7.65 (s, 1H), 8 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.34 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.76 (s, 1H), 12.8 (brs, 1H, D2O exchangeable).; (MS-EI): m/z 318 [M+, 49.64%]. Anal. Calcd. For C18H14N4O2 (318.33): C, 67.91; H, 4.43; N, 17.60, Found: C, 67.85; H, 4.46; N, 17.68.

Methyl-N-phenethylisoxazole-4-carboxamide (5). Using phenylethyl amine. IR (KBr) υ/cm−1: 3345, 1593, 1555; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 2.51 (s, 3H), 3.11 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.72 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.23–7.31 (m, 5H), 8.77 (s, 1H), 12.8 (br s, 1H, D2O exchangeable); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): δ 22.26, 35.14, 41.14, 116.76, 126.69, 128.84, 129.08, 138.83, 139.36, 169.29, 188.79; (MS-EI): m/z 230 [M+, 39.46%]; ESI-HRMS: m/z Calcd. for C13H13N2O2Na2: 275.0772; Found: 275.0769 [M − H + Na2]+; Anal. Calcd. For C13H14N2O2 (230.26): C, 67.81; H, 6.13; N, 12.17, Found: C, 67.88; H, 6.23; N, 12.19.

Bromo-1-(5-methylisoxazole-4-carbonyl)indoline-2,3-dione (6). Using isatin. IR (KBr) υ/cm−1: 3307, 1650, 1639, 1547; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 2.64 (s, 3H), 8.11 (s, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.76 (s, 1H,), 8.83 (s, 1H). Anal. Calcd. For C13H7BrN2O4 (335.11): C, 46.59; H, 2.11; N, 8.36, Found: C, 46.69; H, 2.17; N, 8.3.

Phenyl 5-methylisoxazole-4-carboxylate (7). Using phenol. IR (KBr) υ/cm−1: 1688, 1575; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 2.64 (s, 3H), 6.58 (s, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (s, 1H), 7.7 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.9 (s, 1H), 8.77 (s, 1H).13C-NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): δ 22.84, 116.57, 119.25, 122.45, 126.58, 129.9, 150.73, 163.64, 188.98; (MS-EI): m/z 203 [M+, 5.71%]; Anal. Calcd. For C11H9NO3 (203.19): C, 65.02; H, 4.46; N, 6.89, Found: C, 64.90; H, 4.33; N, 6.84.

o-Tolyl 5-methylisoxazole-4-carboxylate (8). Using o-cresol. IR (KBr) υ/cm−1: 1683, 1570; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 2.13 (s, 3H), 2.5 (s, 3H), 7.08 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.15-7.25 (m, 2H), 7.29 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 8.77 (s, 1H); (MS-EI): m/z 217 [M+, 13.88%]; Anal. Calcd. For C12H11NO3 (217.22): C, 66.35; H, 5.10; N, 6.45, Found: C, 66.45; H, 5.19; N, 6.50.

m-Tolyl 5-methylisoxazole-4-carboxylate (9). Using m-cresol. IR (KBr) υ/cm−1: 1721, 1602; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 2.32 (s, 3H), 2.5 (s, 3H), 6.92–7.03 (m, 2H), 7.08 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.77 (s, 1H); (MS-EI): m/z 217 [M+, 13.3%]; Anal. Calcd. For C12H11NO3 (217.22): C, 66.35; H, 5.10; N, 6.45, Found: C, 66.30; H, 5.08; N, 6.41.

p-Tolyl 5-methylisoxazole-4-carboxylate (10). Using p-cresol. IR (KBr) υ/cm−1: 1676, 1596; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 2.3 (s, 3H), 2.51 (s, 3H), 7.01 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.2 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.77 (s, 1H); (MS-EI): m/z 217 [M+, 12.65%]; Anal. Calcd. For C12H11NO3 (217.22): C, 66.35; H, 5.10; N, 6.45, Found: C, 66.21; H, 5.05; N, 6.48.

2-Nitrophenyl 5-methylisoxazole-4-carboxylate (11). Using 2-nitrophenol. IR (KBr) υ/cm−1: 1703, 1528, 1348; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 2.6 (s, 3H), 7.61 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.34 (s, 1H), 8.73 (s, 1H); (MS-EI): m/z 248 [M+, 1.61%]; Anal. Calcd. For C11H8N2O5 (248.19): C, 53.23; H, 3.25; N, 11.29, Found: C, 53.32; H, 3.28; N, 11.34.

4-Acetylphenyl 5-methylisoxazole-4-carboxylate (12). Using p-hydroxyacetophenone. IR (KBr) υ/cm−1: 1702, 1679, 1591; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 2.63 (s, 3H), 2.64 (s, 3H), 8 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.09 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.77 (s, 1H). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): δ 22.71, 26.91, 115.97, 119.92, 122.56, 126.58, 132, 154.75, 163.97, 187.3, 197.1; (MS-EI): m/z 245 [M+, 3.88%]; Anal. Calcd. For C13H11NO4 (245.23): C, 63.67; H, 4.52; N, 5.71, Found: C, 63.52; H, 4.44; N, 5.59.

4-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)phenyl 5-methylisoxazole-4-carboxylate (13). Using 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)benzimidazole (0.5 g, 0.0024 mol) as phenol; IR (KBr) υ/cm−1: 3307, 1639, 1547; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): δ 2.64 (s, 3H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 2H), 7.54 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 2H), 8.01 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 8.78 (s, 1H). Anal. Calcd. For C18H13N3O3 (319.31): C, 67.71; H, 4.10; N, 13.16, Found: C, 67.74; H, 4.19; N, 13.13.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for Mohamed M. Abu Habib, Pharmacognosy Department, Mansoura University, Egypt, for his valuable help in performing the antioxidant assay.

Author Contributions

All Authors contributed equally to the work mentioned here and to the manuscript writing.

Conflicts of Interest

Some of the work mentioned here was extracted from the master thesis supervised by the 2nd author (Faculty of Pharmacy, Mansoura University, Egypt 2016). The authors confirm no conflict of interest.

References

- Kumar, K.A.; Jayaroopa, P. Isoxazoles: Molecules with potential medicinal properties. Int. J. Pharm. Chem. Biol. Sci. 2013, 3, 294–304. [Google Scholar]

- I Keen, H.; Conaghan, P.G.; Tett, S.E. Safety evaluation of leflunomide in rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2013, 12, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, A.-R.; Huang, W.-H.; Chen, B.; Palfey, B.; Shaw, J. Comparison of Two Molecular Scaffolds, 5-Methylisoxazole-3-Carboxamide and 5-Methylisoxazole-4-Carboxamide. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliel, E.L.; Wilen, S.H.; Mander, L.N. Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; ISBN 0471016705. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, C.; Lectka, T. Solvent Effects on the Barrier to Rotation in Carbamates. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2426–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, R.K.; Becker, E.D.; De Menezes, S.M.C.; Granger, P.; Hoffman, R.E.; Zilm, K.W. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Physical and Biophysical Chemistry Division Further Conventions for NMR Shielding and Chemical Shifts (IUPAC Recommendations 2008). Magn. Reson. Chem. 2008, 46, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, W.E.; Siddall, T.H. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of amides. Chem. Rev. 1970, 70, 517–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, J.; Pan, X.; Hay, E.B.; Geib, S.J.; Wilcox, C.S.; Curran, D.P. Rotational Isomers of N-Methyl-N-arylacetamides and Their Derived Enolates: Implications for Asymmetric Hartwig Oxindole Cyclizations. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 4083–4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, R.; Roussel, C.; Berg, U. The Quantitative Analysis of Steric Effects in Heteroaromatics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 173–299. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, C. Dynamic Stereochemistry of Chiral Compounds; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-85404-246-3. [Google Scholar]

- LaPlante, S.R.; Fader, L.D.; Fandrick, K.R.; Fandrick, D.R.; Hucke, O.; Kemper, R.; Miller, S.P.F.; Edwards, P.J. Assessing Atropisomer Axial Chirality in Drug Discovery and Development. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 7005–7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartels-Keith, J.R.; Cieciuch, R.F.W. Selective deshielding of aromatic protons in some ortho-substituted acetanilides. Can. J. Chem. 1968, 46, 2593–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, A. Medicinal Chemistry, 3rd ed.; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1970; p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi, A.; Said, E.; Farahat, A.A.; El-Bialy, S.A.A.; Massoud, M.A.M. Synthesis and in vivo Antifibrotic Activity of Novel Leflunomide Analogues. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2016, 13, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J. Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1992; ISBN 0471601802. [Google Scholar]

- Ayhan-Kilcigil, G.; Altanlar, N. Synthesis and antimicrobial activities of some new benzimidazole derivatives. Farmaco 2003, 58, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklaszewski, B.; Niememtowski, S. Vergleichendes studium der drei isomeren (β)-amino-phenylbenzimidazole. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1901, 34, 2953–2974. [Google Scholar]

- Klod, S.; Kleinpeter, E.; Kalder, L.; Koch, A.; Henning, D.; Kempter, G.; Benassi, R.; Taddei, F. Ab initio calculation of the anisotropy effect of multiple bonds and the ring current effect of arenes—Application in conformational and configurational analysis. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 2001, 403, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragher, R.J.; Motto, J.M.; Kaminski, M.A.; Schwan, A.L. A convenient synthesis of13C4-Leflunomide and its primary metabolite13C4-A77 1726. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2003, 46, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substituent R Alpha Shift Beta Shift. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/22461745/Substituent_R_Alpha_Shift_Beta_Shift (accessed on 4 December 2017).

- Gfeller, D.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. Shaping the interaction landscape of bioactive molecules. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 3073–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, C.; Henen, M.A.; Belnou, M.; Cantrelle, F.X.; Kamah, A.; Qi, H.; Giustiniani, J.; Chambraud, B.; Baulieu, E.E.; Lippens, G.; et al. A β-turn motif in the steroid hormone receptor’s ligand-binding domains interacts with the peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (PPIase) catalytic site of the immunophilin FKBP52. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 5366–5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.-P.; Sergeyev, S.; Franck, P.; Orru, R.V.A.; Maes, B.U.W. Amine Activation: Synthesis of N-(Hetero)arylamides from Isothioureas and Carboxylic Acids. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 4602–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinkovic, A.; Brkic, D.; Martinovic, J.; Mijin, D.; Milcic, M.; Petrovic, S. Substituent effect on IR, 1H and 13C-NMR spectral data in N-(substituted phenyl)-2-cyanoacetamides: A correlation study. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2013, 19, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahata, Y.; Chong, D.P. Estimation of Hammett sigma constants of substituted benzenes through accurate density-functional calculation of core-electron binding energy shifts. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2005, 103, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahab, B.F.; Awad, E.A.; Badria, F.A. Synthesis, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-hemolytic and cytotoxic evaluation of new imidazole-based heterocycles. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayhan-Kılcıgil, G.; Kus, C.; Özdamar, E.D.; Can-Eke, B.; Iscan, M. Synthesis and Antioxidant Capacities of Some New Benzimidazole Derivatives. Arch. Pharm. 2007, 340, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheswaran, N.; Saleshier, M.F.; Mahalakshmi, K.; Sureshkannan, V.; Parthiban, N.; Reddy, K.A. Synthesis and Characterization of 7-(1H-Benzimidazol-2-yl)-5-(Substituted Phenyl) Pyrido [2, 3-d] Pyrimidin-4-Amine for their Biological Activity. Int. J. Chem. Sci. 2012, 10, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Marian, A.J.; Senthil, V.; Chen, S.N.; Lombardi, R. Antifibrotic effects of antioxidant N-acetylcysteine in a mouse model of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shreenivas, M.T.; Kumara Swamy, B.E.; Manjunatha, J.G.; Chandra, U.; Srinivasa, G.R.; Sherigara, B.S. Synthesis, Antimicrobial Evaluation and Electrochemical Studies of some Novel Isoxazole Derivatives. Pharma Chem. 2011, 3, 224–234. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).