Abstract

The maturity of Lentinus edodes directly affects its quality, taste, and market value. Currently, maturity assessment primarily relies on manual experience, making it difficult to ensure efficiency and consistency. To achieve efficient and accurate detection of Lentinus edodes maturity, this study proposes an improved lightweight object detection model, YOLOv8n-CFS. Based on YOLOv8n, the model integrates the SegNeXt Attention structure to enhance key feature extraction capabilities and optimize feature representation. A Feature Diffusion Propagation Network (FDPN) is designed to improve the expressive ability of objects at different scales through cross-layer feature propagation, enabling precise detection. The CSFCN module combines global cue reasoning with fine-grained spatial information to enhance detection robustness and generalization performance in complex environments. The CWD method is adopted to further optimize the model. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed model achieves 97.34% mAP50 and 84.5% mAP95 on the Lentinus edodes maturity detection task, representing improvements of 2.02% and 4.92% compared to the baseline method, respectively. It exhibits excellent stability in five-fold cross-validation and outperforms models such as Faster R-CNN, YOLOv5n, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, YOLOv10n, YOLOv11n, and YOLOv12. This study provides efficient and reliable technical support for Lentinus edodes maturity detection and holds significant implications for the intelligent production of edible fungi.

1. Introduction

Lentinula edodes holds a crucial position in China’s edible fungi industry, known as the “King of Mushrooms” in the country, and plays an indispensable role in the domestic edible fungi cultivation sector [1,2]. Renowned for its unique flavor and excellent taste among consumers, it features thick flesh, rich nutrition, and the property of integrating medicine and food, boasting extensive ethnic medicinal value as well as high edible and health-preserving values [3,4,5,6,7]. During the production and harvesting of Lentinula edodes, maturity level, as a phenotypic trait, serves as a key criterion for determining the optimal harvesting time. Traditional manual harvesting primarily relies on experience, which is prone to misjudgment, missed judgment of maturity, and low efficiency, thereby affecting the optimal harvesting window of Lentinula edodes. Accurate identification of Lentinula edodes maturity can effectively avoid improper harvesting, reduce costs, and improve harvesting efficiency. Developing efficient and accurate maturity detection technology for Lentinula edodes is of great significance for subsequent high-efficiency and precise harvesting [8].

Deep learning, with its end-to-end efficient recognition capability, has become an important research direction in agricultural intelligent detection [9]. Automatic image feature extraction overcomes the shortcomings of traditional methods in feature dependence and robustness, significantly improving the accuracy of fruit maturity detection [10,11,12]. The YOLO (You Only Look Once) series algorithms [13,14,15,16], as representative models of one-stage object detection, are based on convolutional neural network structures, unifying target classification and localization into a regression task while predicting target categories and bounding box coordinates. Benefiting from advantages such as fast detection speed and low computational cost, YOLO has been widely applied in real-time object detection tasks in the agricultural field [17,18,19].

Shi et al. [20] proposed a lightweight model OMC-YOLO based on YOLOv8n, combining Depthwise Separable Convolution (DWConv), Large Separate Kernel Attention (LSKA), and the Slim-Neck structure to improve the detection accuracy and efficiency of Pleurotus ostreatus. Wang et al. [21] improved YOLOv4 by integrating class-balanced data augmentation, the MobileNetV3 backbone network, and Depthwise Separable Convolution, enhancing the performance of plum detection in orchards and reducing the number of model parameters. Chen et al. [22] proposed MTD-YOLOv7, which improves the accuracy and efficiency of tomato fruit and cluster maturity detection through the design of a multi-task decoder and an improved Scale-Insensitive Intersection over Union (SIoU) loss function. Zhu et al. [23] constructed a lightweight YOLOv7-tiny model named YOLO-LM, introducing Cross Stage Attention (CCA), Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion (ASFF) module, and GSConv into the backbone network to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of Camellia oleifera fruit maturity detection while reducing model complexity and resource requirements. Wang et al. [24] improved YOLOv5 by combining the ShuffleNet v2 backbone, CBAM module, and optimized input size, improving the accuracy and efficiency of detecting lychee fruits at different maturity stages. Gai et al. [25] proposed the YOLOv4-dense model, fusing the DenseNet structure and optimizing anchor boxes to enhance cherry detection speed and feature extraction capability. Xu et al. [26] proposed the YOLO-RFEW model, combining RFAConv with the C2f-FE module and improving the WIoU loss function, which significantly improved muskmelon maturity detection accuracy. Although YOLO series models have shown excellent performance in fruit maturity detection, research focusing on Lentinula edodes maturity remains scarce [27]. Lentinula edodes maturity detection requires high precision and real-time performance, so constructing an accurate and efficient YOLO-based maturity detection model is particularly important for the development of the intelligent Lentinula edodes industry.

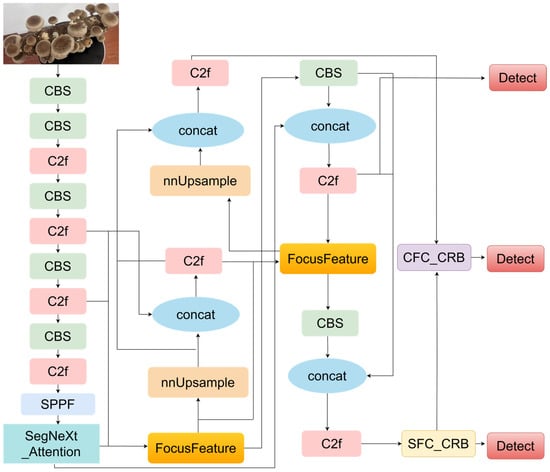

This study proposes a lightweight Lentinula edodes maturity detection model—YOLOv8n-CFS—with structural optimization and knowledge distillation to improve detection accuracy and efficiency. (1) After feature extraction by the backbone network, the SegNeXt-Attention mechanism is introduced to enhance the model’s attention to target regions and reduce background interference. (2) In the neck network, the FDPN module is adopted to optimize multi-scale feature fusion. (3) The CSFCN module is introduced to strengthen the ability of global and fine-grained feature extraction. (4) Finally, the CWD method is used for further optimization to improve detection accuracy. This study provides an efficient and accurate solution for Lentinula edodes maturity detection, with significant agricultural application value.

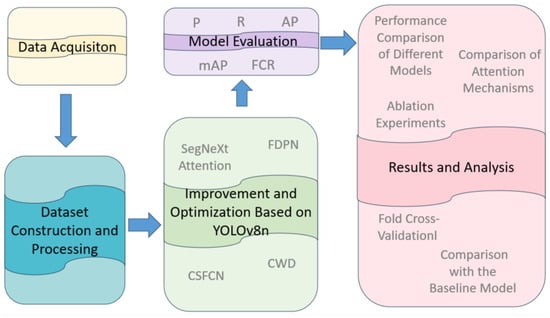

The main flowchart of this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Flowchart.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition

The dataset of Lentinula edodes at different maturity levels was collected at the National Modern Agricultural Science and Technology Demonstration Base located in Nanguan District, Changchun City, Jilin Province, China. The data collection period spanned from July 2024 to July 2025. During the cultivation of each batch of Lentinula edodes, image data were collected three times daily between 8:00 and 21:00, covering shooting scenarios under different lighting conditions and varying shooting distances to ensure sufficient data diversity.

All images were captured using a smartphone camera (iPhone 13 Pro Max, Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA), equipped with an f/1.5 aperture and a maximum image resolution of 4000 × 3000 pixels, enabling the acquisition of high-resolution images with rich visual details. Image acquisition was performed using the built-in Camera application provided by Apple Inc. (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA). The camera software version is integrated with the iOS operating system; therefore, no independent version number is available.

2.2. Dataset Construction and Processing

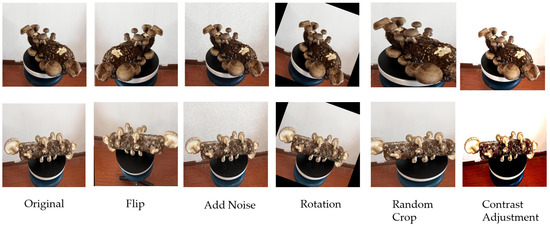

In this study, a “split-first, augment-later” strategy was adopted, where the dataset was randomly divided into a training set (2310 images), a test set (288 images), and a validation set (289 images) at a ratio of 8:1:1. To improve dataset quality and mitigate overfitting risks, various data augmentation techniques were applied to images in the training, test, and validation sets, including Gaussian noise addition, contrast adjustment, rotation, flipping, and random cropping. These operations enhance the model’s generalization ability and further expand the diversity and coverage of training samples. After processing, the dataset consists of 8663 images, including 6930 training set images, 866 test set images, and 867 validation set images. Examples of images augmented by different methods are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Images after data augmentation.

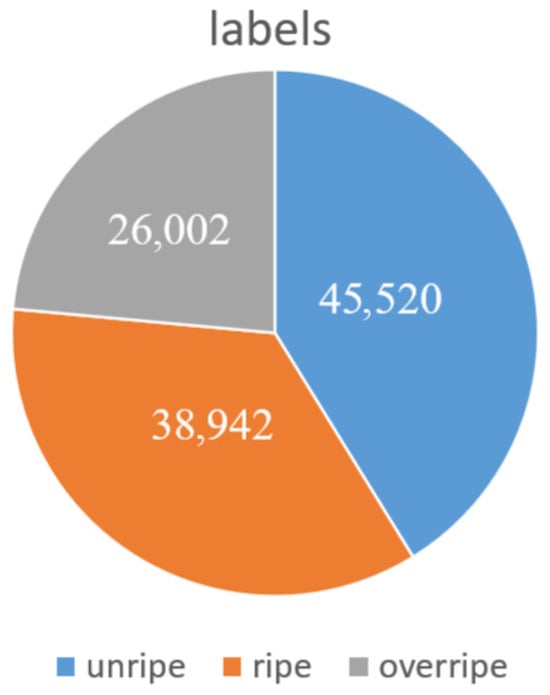

The dataset comprises three maturity categories (unripe, ripe, and overripe). As shown in Figure 3, the numbers of labeled instances for unripe, ripe, and overripe mushrooms are approximately 45,520, 38,942, and 26,002, respectively. Although there is a slight class imbalance, the distribution remains relatively balanced and does not exhibit extreme long-tail characteristics. The imbalance is primarily due to the lower number of overripe instances, which reflects real-world mushroom farming practices where overripe mushrooms are typically harvested before spore release—a condition mirrored in our data collection process.

Figure 3.

Label Counts in Datasets of Different Maturity Levels.

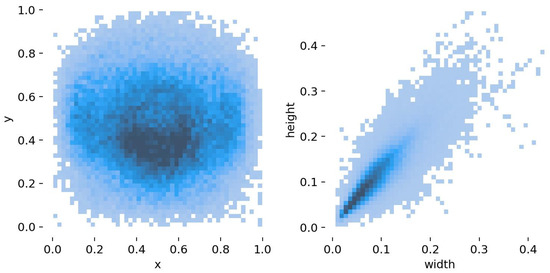

Figure 4 is the bounding box size distribution. It shows that most Lentinula edodes instances belong to small- and medium-scale objects, with normalized widths mainly ranging from 0.05 to 0.15 and heights from 0.05 to 0.20. This distribution indicates that the detection task is dominated by small targets, increasing the difficulty of accurate localization and highlighting the necessity of effective multi-scale feature representation.

Figure 4.

Distribution of bounding box centers and sizes in the Lentinula edodes dataset.

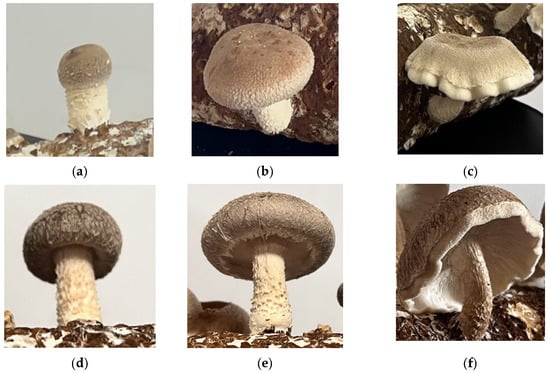

Annotations were performed using LabelImg software v4.6.0 [28], generating XML annotation files in VOC format, which were then converted to TXT files in YOLO format to meet the training requirements of the YOLOv8 model. Based on the maturity levels of Lentinula edodes, the detection targets were categorized into three classes: unripe Lentinula edodes, ripe Lentinula edodes, and overripe Lentinula edodes. Images of Lentinula edodes with different maturity levels are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Images of Lentinula edodes at different angles and maturity levels: (a,d) unripe; (b,e) ripe; (c,f) overripe.

The definitions of Lentinula edodes maturity are as follows:

- (1)

- Unripe Lentinula edodes: The cap is not fully expanded, presenting a hemispherical or ellipsoidal shape with non-exposed gills. The surface is smooth, the diameter is generally less than 2.5 cm, and the texture is firm with a light color.

- (2)

- Ripe Lentinula edodes: The cap is partially expanded, with exposed but undamaged gills. The surface has a good luster, the diameter is approximately 3–5 cm, and the color is uniformly brown. This is the optimal harvesting period.

- (3)

- Overripe Lentinula edodes: The cap is upturned with damaged edges, the gills are darkened, the diameter is greater than 5 cm, the stipe becomes thin or atrophied, the texture is loose with a dull color, and the quality declines.

Annotation protocol for maturity labeling: In this study, the maturity stages of Lentinula edodes were annotated based on visual characteristics under controlled image acquisition conditions rather than direct physical measurement from images. All images were captured at a fixed shooting distance of approximately 25 cm using the same imaging device, ensuring relatively consistent imaging scale across samples. The diameter ranges (e.g., <2.5 cm, 3–5 cm, and >5 cm) described above correspond to biological reference standards commonly used in mushroom cultivation and harvesting practice. During annotation, these thresholds were used as qualitative guidelines in combination with morphological cues such as cap expansion, gill exposure, edge deformation, and texture appearance. Therefore, the maturity labels reflect visually distinguishable growth stages under a fixed-distance imaging setup, rather than precise metric measurements inferred directly from images.

2.3. Network Model and Improvements

2.3.1. The Improved Model: YOLOv8n-CFS

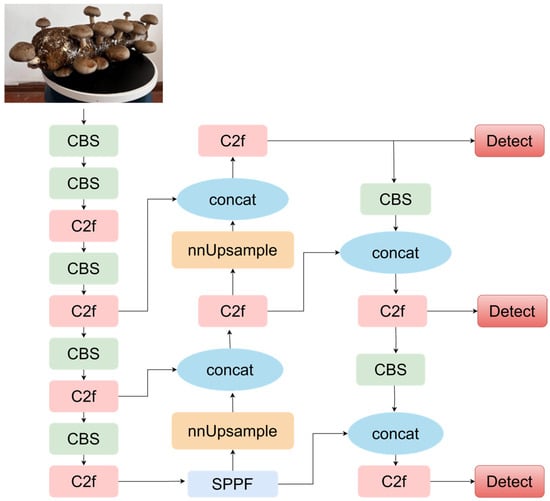

YOLOv8 was released by Ultralytics in 2023 [29] and has been widely applied in object detection tasks. Integrating the advantages of YOLOx, YOLOv6, and YOLOv7 [30,31,32], YOLOv8 offers five model scales (n, s, m, l, x) [33,34,35]. Among these, YOLOv8n features the lightest structure and fastest speed, making it more suitable for real-time detection tasks. Thus, YOLOv8n was selected as the baseline model in this study, Figure 6 shows the network structure of YOLOv8n.

Figure 6.

Structure diagram of the YOLOv8n model.

However, YOLOv8n still faces challenges in Lentinula edodes maturity detection, such as variable morphologies, similar textures and colors, overlapping occlusion, and illumination changes. To address these issues, improvements were made based on YOLOv8n: (1) The SegNeXt-Attention [36] module was introduced into the Backbone to enhance key region features and suppress background interference; (2) The Feature Diffusion Propagation Network (FDPN) [37] was designed in the Neck to optimize multi-scale feature fusion and improve small target detection accuracy; (3) The CSFCN [38], module was integrated to achieve contextual and spatial feature calibration, enhancing illumination robustness; (4) Channel-Wise Distillation (CWD) [39] was adopted to optimize model lightweighting, enabling the student model to inherit fine-grained feature representations from the teacher model. The improved YOLOv8n achieves simultaneous improvements in accuracy and speed for Lentinula edodes maturity detection. The framework of Lentinula edodes maturity detection is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Structure diagram of the YOLOv8n-CFS model.

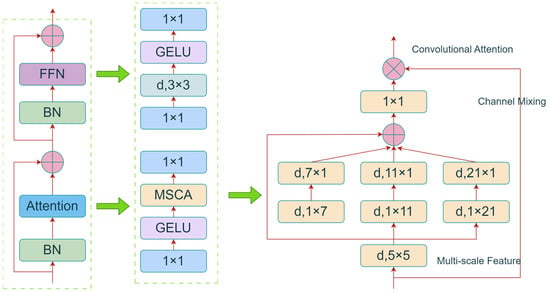

2.3.2. SegNeXt_Attention

The SegNeXt_Attention module combines multi-scale feature extraction and attention mechanism to optimize feature representation and improve detection performance. Figure 8 shows its network structure. Lightweight multi-scale convolution operations perform joint modeling on spatial and channel dimensions to enhance the ability to focus on target regions and effectively suppress irrelevant background information. In the feature extraction stage, a multi-scale convolution structure is adopted, which can be expressed as

Among them, denotes the depthwise convolution operation with different kernel sizes , represents the input feature map, and is the multi-scale fused feature. The 1 × 1 convolution can model the interdependencies between channels to generate channel attention weights:

Channel-wise weighting is performed to obtain the optimized output feature:

Among them, denotes the Sigmoid activation function, and represents the element-wise multiplication.

Multi-scale feature extraction and channel-wise weighting enable the capture of contextual information details. The SegNeXt_Attention module can enhance the ability to capture key features of Lentinula edodes, such as caps, textures, and colors, thereby improving the model’s robustness and detection accuracy in complex environments.

Figure 8.

Structure diagram of the SegNeXt_Attention model.

2.3.3. FDPN

The Focusing Diffusion Pyramid Network (FDPN) integrates a feature focusing module and a feature diffusion mechanism to improve the performance of multi-scale object detection. Its core idea is to utilize parallel convolutions to capture multi-scale contextual information and cross-layer feature diffusion to achieve semantic enhancement and feature sharing. The feature focusing module extracts local and global features through convolutions of different scales (e.g., 1 × 1, 3 × 3, 5 × 5), and the process can be expressed as

Subsequently, the FDPN utilizes the feature diffusion mechanism to fuse high-level semantic information with low-level detailed information, and its expression is as follows:

The final output feature is the weighted fusion of multi-scale features:

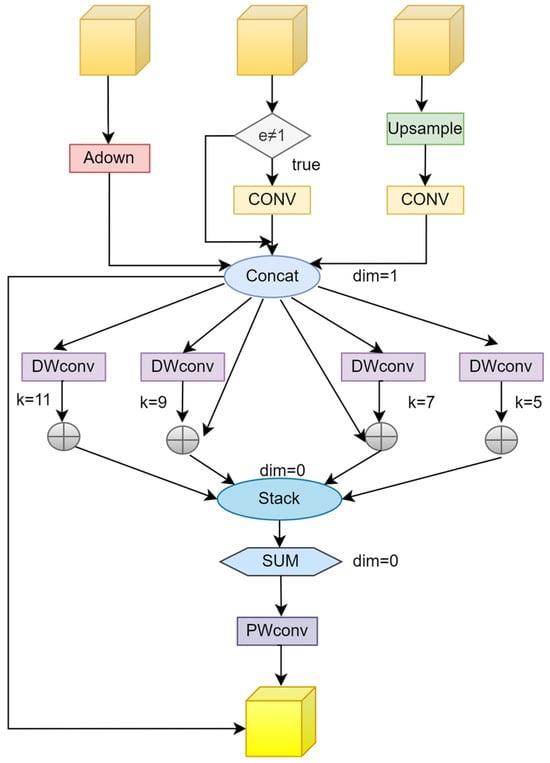

The combination of focusing and diffusion enables FDPN to effectively enhance the expressive ability of cross-scale features, improving the model’s detection accuracy and robustness in complex scenarios. As shown in Figure 9, FDPN significantly improves the accuracy and robustness of multi-scale object detection, and this module exhibits excellent performance in the task of Lentinula edodes maturity detection.

Figure 9.

Diagram of the FDPN architecture.

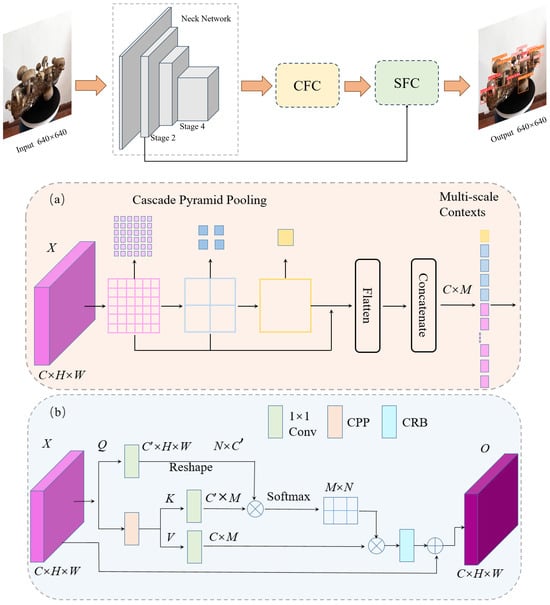

2.3.4. CSFCN

The Cross-Stage Fully Connected Network (CSFCN) is a detection enhancement module that integrates multi-stage feature aggregation and channel-spatial calibration mechanisms. It aims to improve the model’s global feature representation and fine-grained spatial perception capabilities, thereby enhancing adaptability to multi-scale targets and complex backgrounds. The module consists of two serially connected components: Contextual Feature Calibration (CFC) and Spatial Feature Calibration (SFC) (as shown in Figure 10). The CFC module acquires global contextual information through Cascaded Pyramid Pooling Module (CPPM) and fuses multi-scale pooling results to generate semantically enhanced features. Its calculation process can be expressed as

The output feature is fed into the SFC module. By generating a spatial attention weight map, the SFC module achieves redistribution and optimization of spatial information, and its calculation process can be expressed in the following equation:

The SFC module performs element-wise weighting between the generated weight map and the input feature to highlight target regions and suppress background interference, and the process can be described using the equation

The output results of the CFC and SFC modules are fused, followed by channel compression via 1 × 1 convolution to achieve global feature integration. The final output of CSFCN is defined as follows:

Through the joint modeling of context and space, the CSFCN achieves the synergistic enhancement of global and local features, demonstrating excellent performance in both object detection and image segmentation tasks.

Figure 10.

The structure of CSFCN (a) CFC (b) SFC.

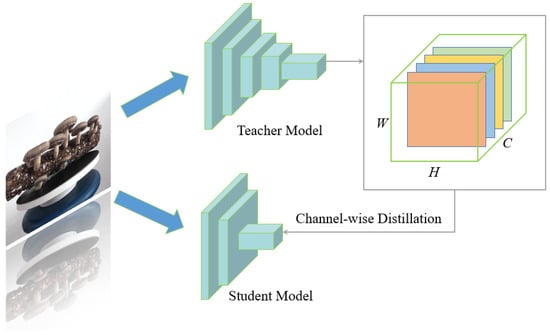

2.3.5. CWD

Knowledge Distillation (KD) is a model compression and optimization technique that enables smaller student models to learn knowledge from complex teacher models, thereby reducing model size or improving efficiency while ensuring performance. Proposed by Hinton et al. [40] in 2015, this method is an important extension of supervised learning. Channel-wise Knowledge Distillation (CWD) is further improved based on this, with its core idea being to guide the student model to learn the information distribution of the teacher model across feature channels, enhancing the representational capacity of lightweight models. As shown in Figure 11, the input image generates feature maps with dimensions (C × H × W) through the teacher model, which is the improved YOLOv8l, while the improved YOLOv8n serves as the student model. Traditional distillation methods mostly impose constraints on the overall feature map or pixel space, which easily leads to insufficient local feature learning. In contrast, CWD is applied to the multi-scale feature maps (P3, P4, and P5) in the neck network, which are crucial for mushroom maturity detection at different spatial scales.

Figure 11.

The Structure of Channel-Wise Distillation.

Assuming the feature maps output by the teacher and student models at a certain layer are , CWD performs normalization on each channel as follows:

The distillation loss is defined via channel-wise KL divergence as follows:

The total loss is composed of the distillation loss and the detection loss :

where λ denotes the balance coefficient and is set to 0.5 in all experiments. Following the original CWD design, no temperature scaling is applied. Both teacher and student models are trained using the same dataset, data augmentation strategies, and training schedule, while the teacher model remains fixed during distillation. This mechanism enables the student model to more accurately capture key channel-wise information from the teacher model and improve detection performance.

2.4. Experimental Platform and Parameter Settings

Table 1 shows the hardware environment required for training includes an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6246R CPU @ 3.40 GHz, an NVIDIA Quadro RTX 8000 (48 GB GPU memory), and 128 GB of RAM. The software environment adopts the Windows 10 operating system, with the deep learning model built based on PyTorch 2.1 and CUDA 11.7.

Table 1.

Experimental Environment Parameters.

During training, the input image size is set to 640 × 640, the batch size is 32, the number of epochs is 200, the learning rate is 0.01, the optimizer is SGD, and the weight decay coefficient is 0.005.

2.5. Evaluation Indicators

In this experiment, the model is evaluated using the metrics of Precision (P), Recall (R), Average Precision (AP), mean Average Precision (mAP), and model size. The definitions of P, R, AP, and mAP are as follows:

True Positive (TP) refers to positive samples predicted as positive. True Negative (TN) denotes negative samples predicted as negative. False Positive (FP) represents negative samples incorrectly predicted as positive, i.e., false detection results. False Negative (FN) indicates positive samples incorrectly predicted as negative. It stands for the total number of categories. Precision is an evaluation metric based on prediction results, representing the proportion of actual positive samples among those predicted as positive. Recall measures the proportion of all positive samples that are correctly identified. Average Precision (AP) refers to the area under the Precision–Recall (P-R) curve for a single category, which comprehensively evaluates the model’s precision and recall. Generally, a higher AP value indicates better model performance. mean Average Precision (mAP) is the average of AP values across all categories, used to assess the overall detection accuracy of the model and is one of the most important performance metrics.

In addition to the above accuracy-oriented metrics, an error-centric reliability indicator is introduced to further evaluate the operational robustness of the model. Following recent agricultural detection failure analysis studies [41], the Failure Case Rate (FCR) is defined as

where FP and FN denote false positives and false negatives, respectively. FCR explicitly quantifies the proportion of failure cases at a given operating point, simultaneously reflecting both missed detections and false alarms. Compared with mAP or F1-score, which may mask concentrated failure patterns under specific confidence thresholds, FCR provides a more intuitive measure of model reliability in practical agricultural detection scenarios. A lower FCR indicates higher operational reliability of the detection system.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Performance Comparison of Different Models

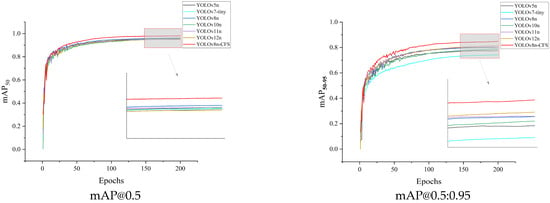

In this study, mainstream object detection models (including Faster R-CNN, YOLOv5n, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, YOLOv10n, YOLOv11n, and YOLOv12n) were selected for comparative analysis of model performance. YOLOv8n exhibited the optimal comprehensive performance among lightweight models and was therefore chosen as the baseline model for improvement. The YOLOv8n-CFS model built on YOLOv8n and all comparative models were trained for 200 epochs under the same dataset and parameter settings, with the experimental results shown in Table 2 and Figure 12.

Table 2.

Performance Comparison of Different Models.

Figure 12.

mAP@0.5 Comparison Curves of Different Models.

YOLOv8n-CFS demonstrated significant advantages in both precision and inference efficiency. Its mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 reached 97.34% and 84.50%, respectively, representing improvements of 2.02% and 4.92% compared to YOLOv8n; 2.59% and 7.33% compared to YOLOv5n; and 39.91% and 44.07% compared to Faster R-CNN. The computational complexity of this model is only 32.7% of YOLOv8s, with parameters accounting for approximately 27%, yet its detection performance is almost comparable to or even partially exceeds that of YOLOv8s (mAP@0.5 = 97.54%, mAP@0.5:0.95 = 83.87%).

Against the significantly optimized YOLOv12n (mAP@0.5 = 95.01%, mAP@0.5:0.95 = 81.44%), YOLOv8n-CFS still maintained a leading edge, outperforming it by 2.33% and 3.06%, respectively. Overall, the YOLOv8n-CFS model is significantly superior to similar models in multiple metrics such as Precision, Recall, and mAP. While maintaining a lightweight structure and low computational cost, it achieves a good balance between detection accuracy and inference speed, demonstrating high engineering practical value and promotion potential.

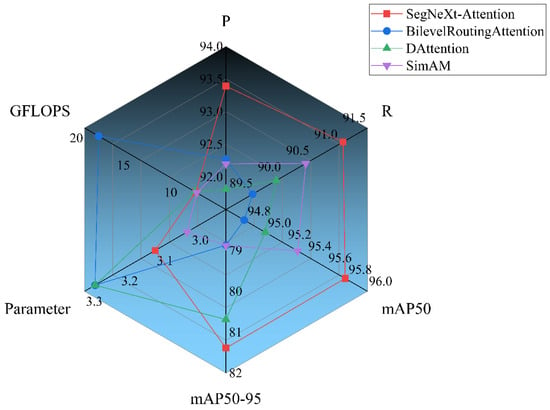

3.2. Comparison of Attention Mechanisms

The effectiveness of various attention mechanisms in Lentinula edodes maturity detection was compared, including DAttention, SimAM, BilevelRoutingAttention, and SegNeXt-Attention. These comparative experiments were conducted on the YOLOv8n model, with all other training settings—such as input image size, batch size, learning rate, optimizer, number of epochs, and data augmentation strategies—kept consistent with those described elsewhere in this study. DAttention enhances the model’s focusing capability through dynamic weight adjustment; SimAM strengthens feature representation with a lightweight structure; BilevelRoutingAttention adopts a hierarchical routing mechanism to improve multi-scale feature perception. In contrast, SegNeXt-Attention combines multi-scale convolutions with spatial-channel modeling, effectively suppressing background interference and highlighting target features.

As shown in Figure 13, the radar chart presents the comparative results of each attention mechanism across six dimensions: Precision (P), Recall (R), mAP@50, mAP@50–95, Parameters, and computational complexity (GFLOPs). Combined with the results in Table 3, SegNeXt-Attention achieves the optimal performance in Precision and Recall, and attains higher detection performance while maintaining low computational complexity. Therefore, SegNeXt-Attention was ultimately selected as the attention module for the improved model.

Figure 13.

Comparison diagram of model performance with different attention mechanisms added.

Table 3.

Performance Comparison of Four Different Attention Mechanisms.

3.3. Ablation Experiments

To evaluate the contribution of each improved module to YOLOv8n-CFS in Lentinula edodes maturity detection, ablation experiments were conducted by gradually introducing SegNeXt-Attention, FDPN, CSFCN, and CWD. The results indicate that each module enhances the model’s feature representation capability and detection performance at different levels.

Specifically, SegNeXt-Attention strengthens the focus on key features through multi-scale convolutions and channel-wise weighting, endowing the model with superior performance in texture and morphological recognition; FDPN combines feature focusing and diffusion mechanisms to improve multi-scale feature fusion and small target detection ability; CSFCN reinforces semantic modeling under complex backgrounds by leveraging contextual and spatial feature calibration; CWD achieves feature distribution alignment via channel-wise distillation, further enhancing the overall model precision.

With the sequential introduction of each module, the model’s mAP50 and mAP95 continuously increased, ultimately improving by 2.02% and 4.92% compared to the baseline YOLOv8n, respectively. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed improvement strategies achieve a good balance between detection accuracy, inference efficiency, and computational cost, effectively enhancing the real-time detection capability of Lentinula edodes maturity.

The inference speed (FPS) reported in Table 4 is measured under a unified experimental setting. All models are evaluated on the same hardware platform using a single NVIDIA GPU. The batch size is set to 1, and inference is performed using FP32 precision. The reported FPS includes both the forward inference and the non-maximum suppression (NMS) process, while excluding data loading and image preprocessing time. To ensure stable measurement, each model is warmed up for 50 iterations before testing, and the final FPS is obtained by averaging the inference time over 200 consecutive runs. Although the proposed model introduces additional modules and slightly increases FLOPs and parameters, the inference speed is not degraded. This is mainly because the improved feature fusion and channel-wise calibration reduce redundant computations and improve GPU utilization efficiency, resulting in faster end-to-end inference.

Table 4.

Ablation Experiment Results.

In addition, the proposed YOLOv8n-CFS achieves a lower FCR compared with the baseline, indicating reduced false detections and missed detections under the same operating conditions.

3.4. 5-Fold Cross-Validation

In the 5-fold cross-validation, the original dataset is first partitioned into five mutually exclusive subsets. In each fold, four subsets are used for training and the remaining one for validation. Data augmentation is applied only after the split and is performed online during training, ensuring that augmented samples from the same original image do not appear across different folds. To further verify the robustness of YOLOv8n-CFS, 5-fold cross-validation was performed for training and testing [42], as shown in Table 5. The detection metrics of YOLOv8n-CFS (Precision, Recall, mAP50, and mAP95) exhibited slight fluctuations across different folds. The Precision values for each fold were 93.05%, 95.26%, 93.44%, 94.39%, and 94.75%, with an average of 94.18% and a standard deviation of 0.89%; the average Recall was 93.71%; the average mAP50 and mAP95 were 97.33% and 84.37%, with standard deviations of 0.38% and 0.40%, respectively. These results indicate that the model achieves highly consistent detection performance under different data partitions

Table 5.

5-Fold Cross-Validation Results.

Table 6 further reports the per-class average AP values with standard deviations across the five folds. The results show that YOLOv8n-CFS maintains stable and consistent detection performance for all maturity categories, indicating strong robustness at the category level.

Table 6.

Per-class AP results (mean ± SD) across 5-fold cross-validation.

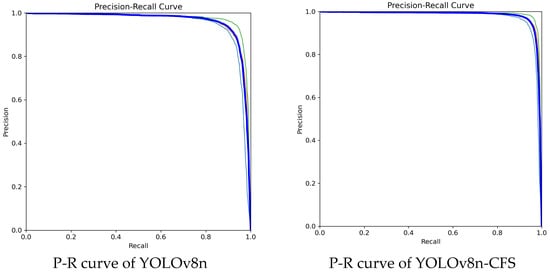

3.5. Comparison with the Baseline Model

Figure 14 presents the Precision–Recall (P-R) curves of the baseline model and the improved model. As observed from the figure, the P-R curve of YOLOv8n-CFS is overall closer to the top-right corner: under the same Recall, its Precision is higher than that of YOLOv8n; under the same Precision, it covers a wider range of Recall. The increase in the Area Under the Curve (AUC) further verifies the optimization of the model’s comprehensive performance. In the high Recall interval (e.g., 0.8–1.0), the Precision of YOLOv8n-CFS shows a gentler downward trend, indicating that the improved model has stronger detection capability for hard samples. It effectively reduces the missed detection risk of unripe small mushroom buds, exhibits better performance at the balance point between Precision and Recall, and the improved algorithm has more reasonable selection of key thresholds.

Figure 14.

Precision–Recall (P-R) Curves of the Baseline Model and the Improved Model (light blue is class unripe; orange is class ripe; green is class overripe; blue is all classes).

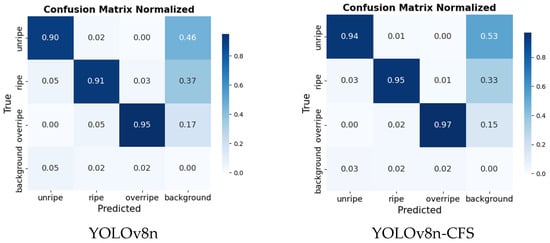

As indicated by the confusion matrix in Figure 15, the improved YOLOv8n-CFS model exhibits significantly higher classification accuracy for the unripe, ripe, and overripe categories. The values on the main diagonal are higher than those of the original model, enabling more accurate distinction between Lentinula edodes of different maturity levels. The misclassification rate is notably reduced: The confusion between unripe and ripe mushrooms is reduced, while uncertain unripe samples are more conservatively assigned to the background category, and the confusion between ripe and overripe mushrooms is also significantly minimized, demonstrating the improved model’s stronger ability to distinguish category-specific features. Additionally, the misclassification of background categories is reduced. YOLOv8n-CFS can more precisely detect the mushroom itself, is less susceptible to background noise interference, and improves the stability of detection.

Figure 15.

Confusion Matrices of the Baseline Model and the Improved Model (the confusion matrix is column-normalized).

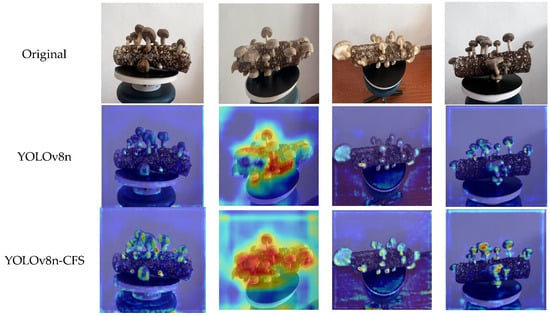

The heatmaps before and after improvement were compared. As shown in Figure 16, heatmaps of Lentinula edodes detection from four different angles are presented. YOLOv8n-CFS more accurately focuses on the key regions of Lentinula edodes in the detection task. The heatmaps generated by the original YOLOv8n model exhibit omissions or uneven attention distribution in some images, while the YOLOv8n-CFS method demonstrates more stable and clear detection capability. It shows more uniform and precise attention to the target regions of Lentinula edodes, with the attention areas in some heatmaps being more concentrated on the mushroom body. The improved method enhances the accuracy of target detection.

Figure 16.

Heatmap Comparison of the Baseline Model and the Improved Model.

The detection performance of different models was evaluated and compared, as shown in Figure 17. “Original” refers to the raw images without any algorithmic processing under different angles and lighting conditions; The detection accuracy of the baseline YOLOv8n model is lower than that of the improved model. It exhibits insufficient discrimination ability in scenarios with complex backgrounds, occlusions, or similar targets, leading to false detections and missed detections. The improved model YOLOv8n-CFS not only enhances the recognition accuracy for single targets but also performs excellently in multi-target recognition scenarios, significantly reducing false and missed detections and improving the overall detection effectiveness.

Figure 17.

Comparative Diagram of Detection Results between YOLO v8n and YOLOv8n-CFS (blue circles indicate missed detections; green circles indicate false detections).

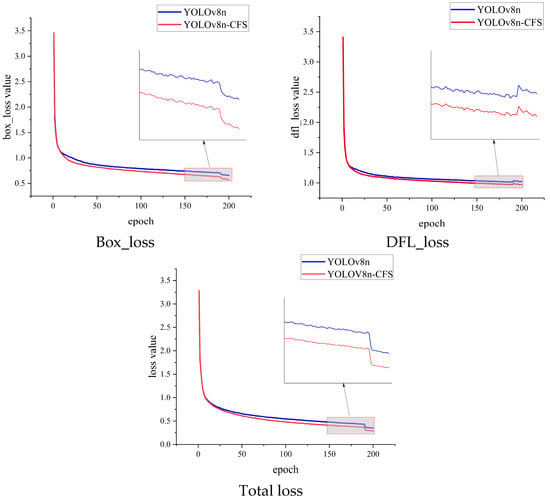

The performance optimization of the model was evaluated by comparing the three loss function curves during the training process of the baseline YOLOv8n and the improved YOLOv8n-CFS model (Figure 18)—Box Loss, Distribution Focal Loss (DFL Loss), and Total Loss. Experimental results show that although both models underwent a rapid learning phase within the first 50 epochs, where the loss values decreased significantly, in the subsequent iterations, the improved YOLOv8n-CFS model exhibited lower values in all three losses. This model possesses stronger learning capability and achieved better overall performance in bounding box prediction and classification accuracy.

Figure 18.

Evaluation of loss performance.

4. Discussion

Real-time maturity detection is of great practical significance for Lentinula edodes due to its rapid growth cycle and high harvesting frequency in industrial cultivation environments. In real production scenarios, mushrooms may transition between maturity stages within short time intervals. Delayed or offline analysis can therefore lead to suboptimal harvesting decisions, resulting in quality degradation and economic losses. Consequently, on-device real-time perception is crucial for timely maturity judgment and intelligent harvesting decision-making.

In practical application scenarios, the proposed YOLOv8n-CFS model can be deployed on greenhouse monitoring terminals to continuously monitor the maturity distribution of mushrooms across cultivation shelves, assisting growers in optimizing harvesting schedules. When integrated into intelligent picking robots, the model enables selective harvesting of mushrooms at the optimal maturity stage while avoiding unripe or overripe samples, thereby improving harvesting efficiency and product consistency. In addition, embedding the model into mobile inspection devices can support rapid field assessment, yield estimation, and production management.

From a hardware deployment perspective, the lightweight design of YOLOv8n-CFS makes it suitable for edge computing platforms such as NVIDIA Jetson series devices, ARM-based embedded systems, and industrial PCs equipped with low-power GPUs. With further optimization techniques, including model pruning and quantization, the proposed model has the potential to be adapted to more resource-constrained edge nodes, supporting stable long-term operation in real agricultural environments.

Technically, YOLOv8n-CFS is built upon the lightweight YOLOv8n architecture and integrates SegNeXt Attention, the Feature Diffusion Pyramid Network (FDPN), and the Cross-Stage Fully Connected Network (CSFCN). This integrated design enhances feature extraction capability, semantic aggregation, and multi-scale feature fusion, which is particularly beneficial for maturity detection under complex backgrounds, occlusion, and scale variation commonly encountered in mushroom cultivation scenarios.

As demonstrated by the experimental results, YOLOv8n-CFS achieves clear performance improvements over the baseline YOLOv8n while maintaining a compact model size and low inference latency. Compared with two-stage detection methods such as Faster R-CNN, the proposed model exhibits a significant advantage in inference speed. It also outperforms other lightweight detectors, including YOLOv11n and YOLOv12n, in terms of the trade-off between detection accuracy and computational efficiency, making it well suited for real-time deployment in resource-constrained agricultural environments.

To address concerns regarding potential performance inflation caused by test set augmentation, supplementary experiments were conducted using the original, non-augmented test set, as summarized in Table 7. Although the absolute detection accuracy decreases slightly due to the increased difficulty of unprocessed real-world images, the proposed YOLOv8n-CFS model consistently outperforms the baseline YOLOv8n under all evaluation settings. These results indicate that data augmentation enhances model robustness and generalization without altering the relative performance ranking among different model variants. More importantly, the consistent performance advantage confirms that the reported improvements primarily stem from the proposed architectural enhancements rather than from test-time data augmentation.

Table 7.

Performance comparison on the non-augmented test set.

Compared with recent agricultural detection models, such as OMC-YOLO proposed by Shi et al. [20] and YOLO-RFEW proposed by Xu et al. [42], YOLOv8n-CFS demonstrates competitive performance while maintaining faster inference speed and a more compact model structure. While existing methods achieve notable accuracy gains through lightweight convolutions or feature enhancement strategies, they remain limited in terms of deployment efficiency. In contrast, the proposed model achieves simultaneous improvements in precision and efficiency through multi-level feature fusion and refined feature calibration. The effectiveness of each module has been further verified through ablation experiments, highlighting the strong portability and engineering applicability of the proposed approach.

Despite its promising performance in Lentinula edodes maturity detection, YOLOv8n-CFS still has certain limitations. Although designed with lightweight considerations, the integration of multiple feature enhancement modules may impose computational and energy constraints on extremely resource-limited devices, such as microcontroller-based platforms or ultra-low-power edge nodes. In addition, the self-built dataset used in this study is limited in sample diversity, as data were collected under specific cultivation conditions. The robustness of the model under varying mushroom stick types, lighting conditions, planting layouts, and viewing angles has not yet been fully validated. Moreover, the current model is specifically tailored for Lentinula edodes maturity detection, and its generalization to other agricultural tasks has not been explored.

Future work will focus on further lightweight optimization through pruning, quantization, and hardware-aware design to reduce computational and storage requirements. Expanding the dataset and incorporating transfer learning and cross-domain adaptation strategies will help improve robustness and generalization in complex real-world environments. In addition, integrating temporal information and multi-modal data will be investigated to support more stable and reliable recognition of the mushroom maturation process, providing stronger technical support for intelligent harvesting and refined agricultural production management.

5. Conclusions

To address the efficiency and accuracy challenges in determining the maturity of Lentinus edodes fruiting bodies, this study conducts research on maturity detection and proposes an improved YOLOv8n-CFS detection model. The model integrates the SegNeXt-Attention module into the backbone to enhance the extraction of critical morphological features and improve robustness under complex imaging conditions. An FDPN is introduced into the neck to optimize multi-scale feature fusion and strengthen the detection capability for targets of varying sizes. In addition, a CSFCN is incorporated to achieve contextual–spatial feature calibration, increasing adaptability to cluttered backgrounds. Channel-wise knowledge distillation (CWD) is further employed to transfer discriminative capability from the teacher model to the lightweight student model, thereby boosting detection accuracy.

To further validate the reliability of the proposed architecture, five-fold cross-validation was conducted, and YOLOv8n-CFS was compared with the original YOLOv8n and several mainstream detection models. Experimental results demonstrate that the improved model outperforms the baseline YOLOv8n across all detection metrics and significantly exceeds the performance of Faster R-CNN, YOLOv5n, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv10n, YOLOv11n, and YOLOv12n. Overall, the model exhibits superior real-time performance and robustness. Future work will focus on extending YOLOv8n-CFS to multi-species edible mushroom maturity detection and deploying the model on mobile platforms to support intelligent harvesting applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.X., J.W., Z.W. and S.W.; Methodology, X.X., J.W. and Z.W.; Software, X.X., J.W. and Z.W.; Validation, X.X., J.W. and Z.W.; Formal analysis, X.X., J.W. and Z.W.; Investigation, J.W. and Z.W.; Resources, J.W. and Z.W.; Data curation, J.W. and Z.W.; Writing—original draft, J.W. and Z.W.; Writing—review & editing, J.W., Z.W. and J.L.; Visualization, J.W. and Z.W.; Supervision, J.W., Z.W. and S.W.; Project administration, J.W. and Z.W.; Funding acquisition, J.W., Z.W. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Development Program Project, grant number 20250601062RC.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the privacy policy of the organization.

Acknowledgments

The main author sincerely thanks the School of Information Technology at Jilin Agricultural University for providing the essential equipment, without which this study would not have been possible. We also wish to express our gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yu, P.; Ma, C.; Gao, Q.; Yan, D.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zong, X.; Wang, S.; Fan, Y. Genome-wide identification and expression profiles of the superoxide dismutase (SOD) genes in Lentinula edodes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 322, 147032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, Y. Sustainability perspectives for future continuity of mushroom production: The bright and dark sides. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1026508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, B. Holistic evaluation of shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes): Unraveling its medicinal and therapeutic potentials. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e01244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, M.; Choi, J.Y.; Kim, M.-S. Metabolic profiles, bioactive compounds, and antioxidant capacity in Lentinula edodes cultivated on log versus sawdust substrates. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindequist, U. Medicinal mushrooms as multicomponent mixtures—Demonstrated with the example of Lentinula edodes. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugajewski, M.; Angerhoefer, N.; Pączek, L.; Kaleta, B. Lentinula edodes as a source of bioactive compounds with therapeutic potential in intestinal inflammation and colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Arif, M.; Xu, M.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Y.; Lyu, F. Therapeutic values and nutraceutical properties of shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes): A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 134, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, S. YOLOv8-CBSE: An enhanced computer vision model for detecting the maturity of chili pepper in the natural environment. Agronomy 2025, 15, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Ji, Z.; Hu, S.; Huang, X.; Yang, J.; Li, W. Tomato maturity recognition model based on improved YOLOv5 in greenhouse. Agronomy 2023, 13, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadnia, R.; Fouladi, S.; Jahanbakhshi, A. Intelligent detection and waste control of hawthorn fruit based on ripening level using machine vision system and deep learning techniques. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badeka, E.; Karapatzak, E.; Karampatea, A.; Bouloumpasi, E.; Kalathas, I.; Lytridis, C.; Tziolas, E.; Tsakalidou, V.N.; Kaburlasos, V.G. A deep learning approach for precision viticulture, assessing grape maturity via YOLOv7. Sensors 2023, 23, 8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Zhou, K.; Hu, Y. Apple maturity detection based on improved YOLOv8. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Computer Vision, Application, and Algorithm (CVAA 2024), Chengdu, China, 11–13 October 2024; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2025; Volume 13486, pp. 539–544. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Parambil, M.M.A.; Ali, L.; Swavaf, M.; Bouktif, S.; Gochoo, M.; Aljassmi, H.; Alnajjar, F. Navigating the YOLO landscape: A comparative study of object detection models for emotion recognition. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 109427–109442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olisah, C.C.; Trewhella, B.; Li, B.; Smith, M.L.; Winstone, B.; Whitfield, E.C.; Fernández, F.F.; Duncalfe, H. Convolutional neural network ensemble learning for hyperspectral imaging-based blackberry fruit ripeness detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 132, 107945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, G.; Piani, M.; Gullino, M.; Mengoli, D.; Franceschini, C.; Grappadelli, L.C.; Manfrini, L. A computer vision system for apple fruit sizing by means of low-cost depth camera and neural network application. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 2740–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1506.02640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, faster, stronger. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7263–7271. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An incremental improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wei, Z.; You, H.; Wang, J.; Bai, Z.; Yu, H.; Ji, R.; Bi, C. OMC-YOLO: A Lightweight Grading Detection Method for Oyster Mushrooms. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Lan, Y. Precision detection of dense plums in orchards using an improved YOLOv4 model. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 839269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, M.; Zhao, C.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. MTD-YOLO: Multi-task deep convolutional neural network for cherry tomato fruit bunch maturity detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 216, 108533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, F.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, C.; Peng, X. Detection of Camellia oleifera fruit maturity based on modified lightweight YOLO. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Lan, Y. Fast and precise detection of litchi fruits for yield estimation based on the improved YOLOv5 model. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 965425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, R.; Chen, N.; Yuan, H. A detection algorithm for cherry fruits based on the improved YOLO-v4 model. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 13895–13906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Ren, R.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, S. Intelligent detection of muskmelon ripeness in greenhouse environment based on YOLO-RFEW. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Fang, M.; Li, Y.; Gao, M. Deep learning based research on quality classification of shiitake mushrooms. LWT 2022, 168, 113902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Wang, K.; Li, Z.; Song, C.; Tang, X.; Song, J. Real-time monitoring of strawberry fruit growth based on an improved YOLO model. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 124363–124372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Qiu, J.; Chaurasia, A. Ultralytics YOLO, version 8; 2023. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Sun, J. YOLOX: Exceeding YOLO series in 2021. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.08430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, F.; Rehman, M.; Anjum, M.; Hussain, A. Optimized YOLOv8: An efficient underwater litter detection using deep learning. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Rong, J. Research on Fruit Spatial Coordinate Positioning by Combining Improved YOLOv8s and Adaptive Multi-Resolution Model. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Xiong, W.; Li, B. Improved lightweight rebar detection network based on YOLOv8s algorithm. Adv. Comput. Signals Syst. 2023, 7, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.-H.; Lu, C.-Z.; Hou, Q.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, M.-M.; Hu, S.-M. SegNeXt: Rethinking convolutional attention design for semantic segmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 1140–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, F.; Kwong, S.; Zhu, G. Feature pyramid network for diffusion-based image inpainting detection. Inf. Sci. 2021, 572, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Geng, Q.; Wan, M.; Cao, X.; Zhou, Z. Context and spatial feature calibration for real-time semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 5465–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Yan, Z.; Shen, C. Channel-wise knowledge distillation for dense prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Hensel, O.; Nasirahmadi, A. From Vineyard to Vision: Multi-Domain Analysis and Mitigation of Grape Cluster Detection Failures in Complex Viticultural Environments. Results Eng. 2025; 108833, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, L.; Yu, H.; Sun, G.; Fei, S.; Zhu, J.; Ma, Y. Winter wheat ear counting based on improved YOLOv7x and Kalman filter tracking algorithm. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1346182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.