Abstract

This study investigated the effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), Trichoderma harzianum, and their combinations on yield and quality of strawberry fruits in a soilless cultivation system. Six treatments were applied, control (no biostimulants), T. harzianum (TH), Claroideoglomus etunicatum (CE), a multispecies mycorrhizal community (IP CS), TH + CE, and TH + IP CS, arranged in a randomized block design with four replicates. While total fruit yield was not significantly affected, the application of T. harzianum, either alone or in combination with AMF, enhanced cumulative fruit production. The use of C. etunicatum improved sugar content and the sugar/acid ratio by 28% and 31%, respectively, compared to the control. Biostimulant treatments also increased total phytochemical content, particularly with the multispecies inoculant IP CS (increased anthocyanin content by 39% compared to the control) and the combinations TH + CE (flavonoid content 41% higher than the control) and TH + IP CS (flavonoid content 39% higher than the control). Multivariate analysis grouped the treatments into two groups, with the control (no biostimulants) forming a distinct group. In conclusion, biostimulation of ‘San Andreas’ strawberry plants improved fruit quality without significantly increasing yield. The combined use of AMF and T. harzianum is proposed as a sustainable strategy for enhancing fruit quality in soilless strawberry cultivation systems.

1. Introduction

The transition from soil-based to soilless cultivation systems has aimed to optimize the horticultural performance of strawberry plants (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.), yet challenges remain, particularly regarding the reduction in chemical inputs (fertilizers and pesticides) to promote agroecosystem sustainability [1]. One promising approach involves the use of microbial biostimulants, notably arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and Trichoderma harzianum Rifai [2].

Recent research has explored the complex responses of strawberry plants to microbial biostimulants [3], while industry efforts have focused on developing and supplying inoculants for horticultural applications [4]. Concurrently, consumer demand for high-quality fruit [5] encourages producers to adopt AMF and T. harzianum in substrate-based strawberry cultivation. However, awareness of these biotools, particularly AMF, due to limited commercial availability, and the synergistic effects of combined biostimulant use remains low among producers. Thus, further research is needed to address gaps in the bioengineering of AMF and T. harzianum for soilless strawberry cultivation, especially regarding the development of a functional substrate microbiota [1].

In strawberry cultivation, AMF addition to the growing medium has shown to enhance the accumulation of macronutrients in plant tissues [6], stimulate root development [1], increase yield [7], and improve fruit phytochemical quality [8], particularly under stress conditions [9]. Similarly, T. harzianum has demonstrated benefits for yield and fruit quality [10] and serves as an effective biocontrol agent against strawberry diseases [11]. To date, only one study has examined the combined effects of AMF and T. harzianum on strawberry plants in terms of phyllochron, phenology, and fruit sugar and acidity levels [2]; therefore, a lack of literature on their joint impact on strawberry fruit yield potential and phytochemical quality throughout the cultivation cycle remains limited. This lack of research on co-inoculation consortia with microbial biostimulants is related to the low availability of commercial products, especially mycorrhizal inoculants, to the maintenance of their viability over time, and to the scarcity of management practices that enhance these microorganisms’ action, such as reducing the use of chemical inputs in favor of adding biostimulants in plant cultivation [1].

By integrating two microbial agents with biostimulant potential, this study aims to advance the development of more efficient, resilient, and sustainable strawberry production systems. The findings may also stimulate industry interests in developing mycorrhizal inoculants for either on-farm or commercial use, thereby promoting the adoption of AMF in horticultural systems in association with T. harzianum. Ultimately, this research seeks to strengthen the functional microbiota of the increasing substrate production systems.

Based on the hypothesis that T. harzianum enhances AMF activity, the objective of this study was to investigate the effects of AMF, T. harzianum, and their combinations on the yield and quality of strawberry fruits in a soilless cultivation system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

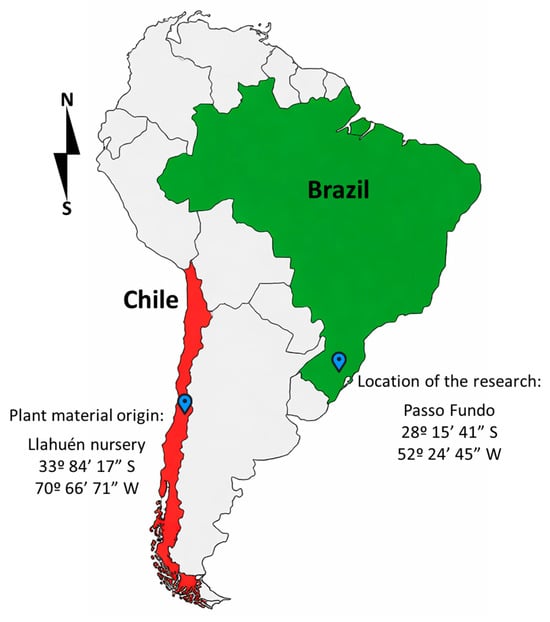

Bare-root, vegetatively propagated strawberry plants (‘San Andreas’, everbearing type) were purchased from the Llahuén nursery in Chilean Patagonia (33°84′17″ S; 70°66′71″ W). The experiment was conducted in Passo Fundo (28°15′41″ S; 52°24′45″ W), Rio Grande do Sul (RS), Brazil (Figure 1), from June 2024 (winter) to March 2025 (fall) in a 430 m2 greenhouse with a semicircular roof covered by a low-density polyethylene film (150 µm thick) and an anti-ultraviolet additive.

Figure 1.

The research was conducted in the municipality of Passo Fundo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, from June 2024 to March 2025, using bare-root, vegetatively propagated strawberry plants from Chilean Patagonia.

2.2. Experimental Design

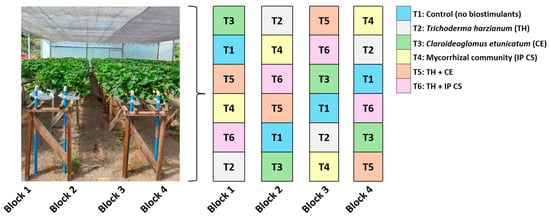

Six treatments were established: control (no biostimulants), Trichoderma harzianum (TH), Claroideoglomus etunicatum (CE), a multispecies mycorrhizal community (IP CS), TH + CE, and TH + IP CS. The treatments were arranged in a randomized block design with four replicates (Figure 2). Each plot consisted of six plants (24 plants per treatment; n = 144 plants).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram illustrating number of treatments and replicates and experimental layout.

AMF-based biostimulants were represented by on-farm inoculants. The monospecies inoculant C. etunicatum was sourced from the International Glomeromycota Culture Collection (CICG) at the Regional University of Blumenau (FURB), Blumenau, Santa Catarina (SC), Brazil. The multispecies inoculant (IP CS) was generated via a trap culture technique from agricultural soil collected at a reference strawberry site in Ipê, RS (28°49′20″ S; 51°16′32″ W) [12], composed of 14 AMF species [13]: Acaulospora colossica P.A. Schultz, Bever, & J.B. Morton; Acaulospora sp.; Cetraspora pellucida (T.H. Nicolson & N.C. Schenck), Oehl, F.A. Souza, & Sieverd.; Claroideoglomus etunicatum (W.N. Becker & Gerd.), C. Walker, & A. Schüßler; Dentiscutata erythropa (Koske & C. Walker); Dentiscutata heterogama (T. H Nicolson & Gerd.), Sieverd., F.A. Souza, & Oehl; Dentiscutata rubra (Stürmer & J.B. Morton); Funneliformis aff. geosporum; Funneliformis mosseae (T.H. Nicolson & Gerd.), C. Walker, & A. Schüßler; Gigaspora sp.; Glomus aff. caledonium; Glomus aff. manihotis; Glomus sp. (caesaris-like); and Glomus sp1. The T. harzianum-based biostimulant was the commercial product Trichodermil® (Koppert®, Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil).

2.3. On-Farm Production of Mycorrhizal Inoculants

Two AMF inoculants were produced using sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] as a host plant and the trap culture technique [14], with sterilized sand (120 °C, 20 min) as substrate. Inoculant production occurred in a 90 m2 greenhouse with a semicircular roof and UV-inhibited polyethylene film (150 µm). After five months of sorghum cultivation (January–May 2024), the inoculants consisted of fungal spores, root fragments, and sterile sand. The spore density (number per 50 g of on-farm inoculant) was 728 and 653 for C. etunicatum and IP CS, respectively.

2.4. Cultivation Techniques

Plants were transplanted in June 2024 into containers (1 m × 0.3 m, 30 L) filled with Dallemole® substrate (Vacaria, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil), composed of pine bark, rice husks, rice ash, and class A organic compost. Physical and chemical properties of the substrate are shown in Table 1. The plants were spaced 0.17 m apart, with one row of plants per container.

Table 1.

Physical and chemical characterization of the Dallemole® substrate.

For AMF treatments, 2 g of inoculant were applied monthly in the planting bed at the time of transplanting (June) and, in the following months, around the crown of the plants. For T. harzianum treatments, a solution of 2 mL·L−1 Trichodermil® was prepared monthly based on the product specifications, and 10 mL was applied to each plant at the crown base using a micropipette.

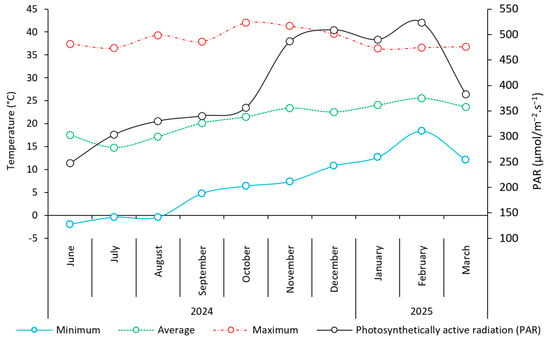

Irrigation was performed using an automated dripper system (flow rate of 1.4 L·h−1 per dripper). Nutrient solutions were applied weekly, with a 50% reduction in phosphorus [9]. Air temperature (minimum, average, and maximum) and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) inside the greenhouse were monitored throughout the experiment (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Minimum, average, and maximum (°C) monthly temperatures and photosynthetically active radiation inside the greenhouse during the experiment.

2.5. Detection of AMF and T. harzianum in Roots

AMF colonization was assessed [15] and mycorrhizal colonization percentage (MC, %) was determined [16]. T. harzianum detection in plant roots was performed by taking roots from the substrate and washing them in running water. Approximately 30 portions of roots (2 mm in diameter) from each treatment were cut, and 70% alcohol were washed for 30 s. The roots were then subjected to asepsis in hypochlorite + water (1:1 v/v) for 2 min, rinsed with sterilized water, and dried on filter paper. Thereafter, they were transferred to potato-dextrose-agar culture medium and incubated in a growth chamber (25 °C, 12 h of light) for seven days.

2.6. Fruit Yield

From fruiting onwards, the total number of fruits per plant (TNF) and total fruit production per plant (TP, g) were recorded. Harvest started in August 2024 and finished in March 2025. Approximately seven harvests per month were performed. The fruits were harvested when fully ripe [1] and weighed on a digital scale. Average fresh fruit mass (AFFM, g) was calculated by dividing TP by TNF.

2.7. Fruit Quality

At peak production (November 2024), 20 fruits per treatment per replicate were analyzed for internal quality. Total soluble solids (TSS, %) were measured with a refractometer. Total titratable acidity (TTA, % citric acid) was determined by Adolfo Lutz Institute standards [17]. From each sample, 10 mL of fruit juice and 90 mL of distilled water were added to an Erlenmeyer flask. Then, 0.3 mL of phenolphthalein solution was added, and titration was carried out with sodium hydroxide solution (0.1 M) under constant stirring, until a persistent pink color was obtained for 30 s. The TSS/TTA ratio was calculated to assess sugar-to-acid balance.

In addition, 100 g of fruit from each repetition was used for analysis of total anthocyanins (TAs), total flavonoids (TFs), and total polyphenols (TPOs). The fruit was analyzed in fresh mass, consistent with its form of consumption.

TAs were carried out by pH differential [18]. Aliquots of extract were diluted in aqueous buffers of pH 1.0 and 4.5 and readings were taken at 510 nm and 700 nm by spectrophotometry (PerkinElmer Lambda 20, Perkin Elmer®, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). TA content was determined using Equation (1).

A = (Aλvis-max(510) − A700) pH 1.0 − (Aλvis-max(510) − A700) pH 4.5

Equation (2) was used to calculate monomeric anthocyanin concentration.

where MW = molecular weight of pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside (433.20); DF = dilution factor; ε = molar absorptivity coefficient (25.660). The results were expressed in mg of pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside equivalent per 100 g of fresh fruit (mg PE/100 g FF−1).

TFs were carried out according to Basílio et al. (2022) [19]. Absorbance readings were taken at 425 nm by spectrophotometry (PerkinElmer Lambda 20, Perkin Elmer®), and the results were calculated using a standard curve with rutin and expressed in mg of rutin equivalent per 100 g of fresh fruit (mg RE/100 g FF−1).

TPOs were determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent [20]. Absorbance readings were taken at 760 nm by spectrophotometry (PerkinElmer Lambda 20, Perkin Elmer®, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), and the results were calculated using a standard curve with gallic acid and expressed in mg of gallic acid equivalent per 100 g of fresh fruit (mg GAE/100 g FF−1).

2.8. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the treatment means were compared using Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05) in R version 4.5.2 [21]. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed after standardizing, with eigenvalues < 1 excluded [22]. Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed on z-score standardized variables using Euclidean distance, and dendrograms were generated using the ‘factoextra’ package in R version 4.5.2 [21]. Cluster analysis was validated by cophenetic correlation coefficient [23].

3. Results

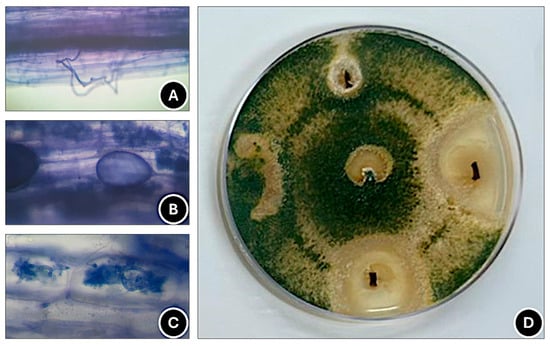

3.1. Detection of AMF and T. harzianum in Roots

Plants inoculated with C. etunicatum (CE) exhibited the highest mycorrhizal colonization (MC), followed by those treated with the IP CS community (IP CS), T. harzianum (TH) + CE, and TH + IP CS (Table 2). Notably, TH enhanced MC in the multispecies IP CS inoculant, indicating synergistic interaction (Table 2). Root structures observed included hyphae (Figure 4A), vesicles (Figure 4B), and arbuscules (Figure 4C). T. harzianum incidence (THI) was 68% in treated plants (Table 2 and Figure 4D), while biostimulant treatments TH + CE and TH + IP CS did not increase THI (Table 2).

Table 2.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Trichoderma harzianum detection in strawberry roots of cv. ‘San Andreas’.

Figure 4.

Hyphae (A), vesicles (B), and arbuscules (C) of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi observed under an optical microscope (400× magnification) and occurrence of Trichoderma harzianum (D) in strawberry roots of cv. ‘San Andreas’.

3.2. Fruit Yield

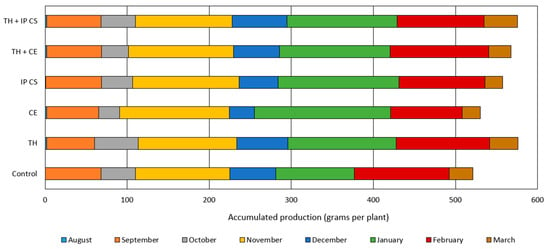

Biostimulant treatment did not affect total fruit yield (Table 3). However, monthly yield analyses revealed that T. harzianum, alone or in combination with AMF, improved cumulative fruit production (Figure 5). Control plants (no biostimulants) had lowest cumulative yield (Figure 5).

Table 3.

Strawberry yield of cv. ‘San Andreas’ grown with and without biostimulants.

Figure 5.

Monthly strawberry yield of cv. ‘San Andreas’ grown without and with biostimulants. TH: Trichoderma harzianum; CE: monospecies inoculant formed by Claroideoglomus etunicatum; IP CS: multispecies inoculant from cultivated soil (CS) collected in Ipê (IP), RS, Brazil.

3.3. Fruit Quality

The monospecies inoculant (C. etunicatum) improved TSS and the TSS/TTA ratio by 28% and 31%, respectively, compared to the control (Table 4). Biostimulant treatment generally enhanced total phytochemical content (Table 4), with the multispecies IP CS inoculant (increased TA and TF content by 39% and 41%, respectively, compared to the control) and the associations between TH + CE (TF content 41% higher than the control) and TH + IP CS (TF content 39% higher than the control).

Table 4.

Strawberry quality of cv. ‘San Andreas’ in the absence and presence of biostimulants.

3.4. Multivariate Analysis

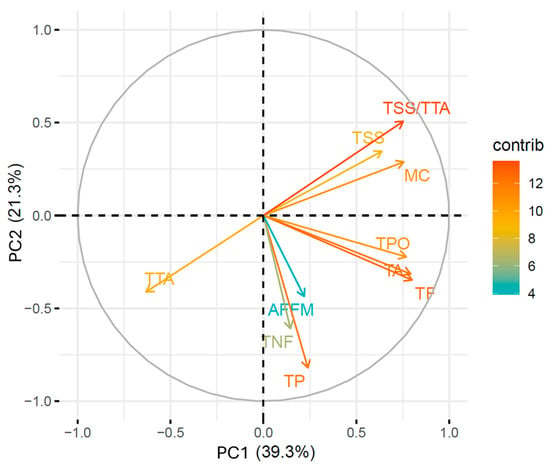

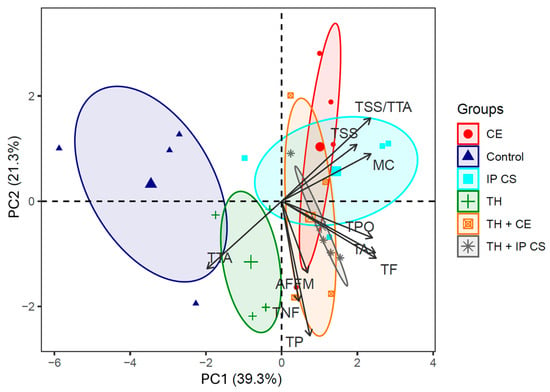

Principal component analysis (PCA) indicated that the first two principal components (PCs) accounted for 60.66% of the total variance (Figure 6). Attributes contributing most to PC1 included MC, TSS, TTA, TSS/TTA, TA, TF, and TPO (96.75%) (Table 5). For PC2, the attributes TSS/TTA, TP, and TNF contributed 60.96%. In PC3, the attributes TP, TNF, and AFFM represented 72.20% of the total variation (Table 5). PCA formed two groups, one of which included only the control (Figure 7). This treatment had fruits with the lowest total flavonoid and polyphenol content (Table 4). The second group was formed by the other five treatments containing biostimulants, either alone or in combination (Figure 7), which mainly corroborated the results of the total phytochemical content of the fruits (Table 4).

Figure 6.

Principal component analysis with the percentage contribution of yield and quality attributes. MC: Mycorrhizal colonization; TSS: total soluble solids; TTA: total titratable acidity; TSS/TTA: fruit flavor; TA: total anthocyanin; TF: total flavonoid; TPO: total polyphenol; TNF: total number of fruits; TP: total production; AFFM: average fresh fruit mass.

Table 5.

Attributes, principal components (PCs), autovalues (λi), proportion of variance (PV), and accumulated proportion of variance (APV) of strawberry plants cultivated with two biostimulants.

Figure 7.

Clustering relationships through principal component analysis. MC: Mycorrhizal colonization; TSS: total soluble solids; TTA: total titratable acidity; TSS/TTA: fruit flavor; TA: total anthocyanin; TF: total flavonoid; TPO: total polyphenol; TNF: total number of fruits; TP: total production; AFFM: average fresh fruit mass. TH: Trichoderma harzianum; CE: monospecies inoculant formed by Claroideoglomus etunicatum; IP CS: multispecies inoculant from cultivated soil (CS) collected in the municipality of Ipê (IP), RS, Brazil.

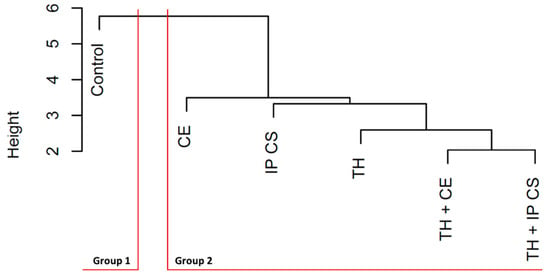

This same grouping was formed in the dendrogram (Figure 8). These dissimilarities among the six treatments (Figure 8) had adjustment to the data distance matrix, calculated by the cophenetic correlation coefficient, of 89%, which indicated adequacy of the grouping.

Figure 8.

Dendrogram of the six treatments in strawberry plants of cv. ‘San Andreas’. TH: Trichoderma harzianum; CE: monospecies inoculant formed by Claroideoglomus etunicatum; IP CS: multispecies inoculant from cultivated soil (CS) collected in the municipality of Ipê (IP), RS, Brazil.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that the application of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and Trichoderma harzianum, either individually or in combination, can significantly influence the horticultural performance of strawberry cv. ‘San Andreas’ cultivated in a soilless system. The most notable effects were observed in the enhancement of fruit phytochemical content (anthocyanins and flavonoids) and sugar levels, rather than total yield. These results underscore the functional roles of AMF and T. harzianum in modulating plant physiology and fruit quality and suggest that their coordinated action facilitates adaptation of strawberry to soilless cultivation environments.

A key finding was the synergistic interaction between T. harzianum and the multispecies AMF inoculant (IP CS), which resulted in an ~10% increase in mycorrhizal colonization compared to the use of the inoculant alone (Table 2). This synergy is likely T. harzianum’s ability to modulate the rhizosphere through the release of volatile organic compounds, siderophores, and hydrolytic enzymes [24]. These compounds can alter root architecture and improve the physical and chemical properties of the growth medium, thereby facilitating AMF hyphae penetration and colonization [25]. Furthermore, the combined application of T. harzianum with AMF inoculants (IP CS and Claroideoglomus etunicatum) led to increased flavonoid content in fruits (Table 4), reinforcing the role of T. harzianum as an inducer of plant defense responses and secondary metabolite biosynthesis [26].

Although dual inoculation with AMF and T. harzianum has been reported to benefit horticultural crops [27], the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Previous studies have shown that T. harzianum can enhance enzymatic activity in the rhizosphere of AMF-colonized plants [28], and that the association between these fungi can modulate the host plant’s hormonal profile (salicylic acid and jasmonic acid) and key enzymes involved in secondary metabolism [29,30]. Indirectly, AMF and Trichoderma spp. can promote plant health under stress conditions by secreting secondary metabolites, accumulating osmolytes, and improving water and nutrient uptake [31,32,33,34]. Enhanced nutrient acquisition, particularly phosphorus and zinc, may contribute to increased biosynthesis of phytochemicals such as flavonoids [8,35], which aligns with the higher flavonoid content observed in strawberries treated with both AMF and T. harzianum (Table 4).

While the overall effect on yield was not statistically significant, cumulative fruit production was higher in plants treated with T. harzianum, either alone or in combination with AMF (Figure 5). This suggests a gradual physiological improvement in resource use efficiency, likely attributable to the beneficial effects of both microbial groups [2]. However, further research is needed to elucidate the biochemical and metabolomic interactions underlying yield enhancement in co-inoculated plants [36]. Long-term studies monitoring the ecological persistence and functional dynamics of these microbial consortia across multiple production cycles will be essential to validate their effectiveness and clarify their impact on rhizosphere microbiota and plant performance.

A major challenge for producers is to simultaneously achieve high yield and superior fruit quality, particularly in response to consumer demands for strawberries with enhanced functional properties. Our findings indicate that AMF are the primary microbial agents responsible for improving fruit quality, with C. etunicatum increased sugar content and flavor, and the IP CS community intensifying the biosynthesis of phytochemicals, especially anthocyanins and flavonoids (Table 4). AMF are known to modulate the host plant metabolome through various pathways, influencing the synthesis of health-promoting phytochemicals [37].

In greenhouse strawberry cultivation, which typically relies on commercial substrates, on-farm mycorrhizal inoculants offer a promising alternative for reducing chemical inputs, enhancing plant resilience to abiotic stress, and fostering the development of a beneficial substrate microbiota [1]. These inoculants are compatible with organic or regenerative agriculture certification programs [38], and their viability is supported by low production costs, simplicity of the trap cultivation technique, and adaptability to local agroecosystem conditions [39]. The effectiveness of AMF inoculation depends on the appropriate combination of fungal species, host plant, substrate, and cultivation technology [40]. Thus, the only two studies about AMF surveys in strawberry [12,41] are important to select AMF that have an affinity with this horticultural crop. The use of AMF compatible with the host commonly provides more satisfactory results [42]. Indicated as a generalist species in strawberry cultivation [12], C. etunicatum was more effective in colonizing its roots [43], in addition to improving root development and strawberry yield [44]. C. etunicatum symbiosis can promote plant growth by increasing P uptake, regulating plant hormone signal transduction, photosynthesis, and glycerophospholipid metabolism pathways [45]. This may explain why C. etunicatum increased sugar content and flavor of strawberries (Table 4).

Most commercial mycorrhizal inoculants consist of a single species from widely distributed genera such as Funneliformis, Glomus, and Rhizophagus [46]. However, multispecies inoculants derived from locally adapted communities, such as IP CS, provide greater robustness and sustainability, promoting efficient root colonization and agroecosystem resilience [47,48]. The diversity of the IP CS inoculant (14 species) likely contributed to the physiological and biochemical stability observed in the soilless strawberry system, particularly in terms of anthocyanin accumulation. Large-scale multiplication of AMF for an inoculant formulation can be performed in aeroponic, hydroponic, or in vitro systems [49]. However, one option for increasing the use and acceptance of an AMF-based biostimulant is to develop an inoculant produced by the on-farm method, obtained on site where it will later be used, in order to avoid the costs associated with buying a commercial product [50]. On-farm inoculant can be developed under natural environmental conditions, multiplying mycorrhizal species indigenous to a given ecosystem, and/or with known efficiency [51].

Overall, the functional synergy between AMF and T. harzianum identified in this study suggest that their combined application may serve as an efficient and sustainable management strategy for strawberry cultivation in substrate and greenhouses. Given the increasing demand for nutraceutical foods free of chemical residues, the adoption of these microbial biostimulants can add value both to the strawberry production chain and benefit consumer health. A deeper understanding of the interactions among AMF, T. harzianum, and host plants within ecosystem processes is essential for maximizing plant development and health [37]. Finally, our results point to future research directions that include (1) molecular characterization of co-inoculation consortia to assess the functional diversity of microbial biostimulants using molecular markers and (2) the development of public policies and incentives to support on-farm inoculant production, thereby promoting producer autonomy and the widespread adoption of sustainable biostimulation practices.

5. Conclusions

Biostimulation of ‘San Andreas’ strawberry plants with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and Trichoderma harzianum enhances fruit quality, particularly by increasing sugar content and the accumulation of phytochemicals such anthocyanins and flavonoids but does not significantly increase total yield. The monospecies mycorrhizal inoculant (Claroideoglomus etunicatum) improves sugar content and fruit flavor by 28% and 31%, respectively, compared to the control. The multispecies IP CS inoculant (composed of 14 fungal species) enhances phytochemical biosynthesis, especially the anthocyanin content (39% higher compared to the control). T. harzianum further stimulates the action of both AMF inoculants, increasing cumulative fruit production and flavonoid content. These findings support the combined use of AMF and T. harzianum as a sustainable tool for soilless cultivation of strawberries, aiming to enhance the performance of this important horticultural crop.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.T.C., N.A.M., A.J.S.E., and M.W.; methodology, J.L.T.C., N.A.M., A.J.S.E., M.W., H.D., M.A.L.O., and B.J.; software, J.L.T.C., F.W.R.J., M.P.B., R.R., and T.d.S.T.; validation, J.L.T.C., N.A.M., A.J.S.E., M.W., H.D., M.A.L.O., B.J., F.W.R.J., M.P.B., R.R., T.d.S.T., and A.S.; formal analysis, J.L.T.C., N.A.M., A.J.S.E., M.W., H.D., M.A.L.O., and B.J.; investigation, J.L.T.C., N.A.M., A.J.S.E., M.W., H.D., M.A.L.O., B.J., F.W.R.J., M.P.B., R.R., T.d.S.T., and A.S.; resources, J.L.T.C.; data curation, N.A.M., A.J.S.E., and M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.T.C., N.A.M., A.J.S.E., M.W., F.W.R.J., M.P.B., R.R., T.d.S.T., and A.S.; writing—review and editing, J.L.T.C., F.W.R.J., M.P.B., R.R., T.d.S.T., and A.S.; visualization, J.L.T.C., N.A.M., A.J.S.E., M.W., H.D., M.A.L.O., B.J., F.W.R.J., M.P.B., R.R., T.d.S.T., and A.S.; supervision, J.L.T.C.; project administration, J.L.T.C.; funding acquisition, J.L.T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thanks the University of Passo Fundo, Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for granting scientific initiation scholarships. We also thank Bioagro Comercial Agropecuária Ltd., for the supply of ‘San Andreas’, Koppert for the supply of the Trichodermil®, and the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO) for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

AMF that were used in this work are regulated by the Sistema Nacional de Gestão do Patrimônio Genético e do Conhecimento Tradicional Associado (SisGen) of the Ministry of the Environment, Brazil, according to the registration number A198F50.

References

- Chiomento, J.L.T.; De Nardi, F.S.; Fante, R.; Dal Pizzol, E.; Trentin, T.S.; Borba, A.C.; Basílio, L.S.P.; Garcia, V.A.S.; Lima, G.P.P. Building the microbiota in strawberry soilless cultivation systems with on-farm AMF inoculants: Roles in yield, phytochemical profile, and root morphology. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 178, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiomento, J.L.T.; Fracaro, J.; Görgen, M.; Fante, R.; Dal Pizzol, E.; Welter, M.; Klein, A.P.; Trentin, T.S.; Suzana-Milan, C.S.; Palencia, P. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, Ascophyllum nodosum, Trichoderma harzianum, and their combinations influence the phyllochron, phenology, and fruit quality of strawberry plants. Agronomy 2024, 14, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobek, M.; Cybulska, J.; Frąc, M.; Pieczywek, P.; Pertile, G.; Chibrikov, V.; Nosalewicz, A.; Feledyn-Szewczyk, B.; Sas-Paszt, L.; Zdunek, A. Microbial biostimulants affect the development of pathogenic microorganisms and the quality of fresh strawberries (Fragaria ananassa Duch.). Sci. Hortic. 2024, 327, 112793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Rodríguez, A.M.; Parra Cota, F.I.; Cira Chávez, L.A.; García Ortega, L.F.; Estrada Alvarado, M.I.; Santoyo, G.; De Los Santos-Villalobos, S. Microbial inoculants in sustainable agriculture: Advancements, challenges, and future directions. Plants 2025, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Girones, S.; Ruizendaal, J.; Salas-Valderrama, X.; Munera, S.; Blasco, J.; Polder, G. Advanced evaluation of strawberry quality, consumer preference, and cultivar discrimination through spectral imaging and neural networks. Food Control 2025, 175, 111339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentin, T.S.; Dornelles, A.G.; Trentin, N.S.; Huzar-Novakowiski, J.; Calvete, E.O.; Chiomento, J.L.T. Addition of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and biochar in the cultivation substrate benefits macronutrient contents in strawberry plants. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 2980–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirdel, M.; Eshghi, S.; Shahsavandi, F.; Fallahi, E. Arbuscular mycorrhiza inoculation mitigates the adverse effects of heat stress on yield and physiological responses in strawberry plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 221, 109629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whyle, R.L.; Trowbridge, A.M.; Jamieson, M.A. Genotype, mycorrhizae, and herbivory interact to shape strawberry plant functional traits. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 964941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nardi, F.S.; Trentin, T.S.; Trentin, N.S.; Costa, R.C.; Calvete, E.O.; Palencia, P.; Chiomento, J.L.T. Mycorrhizal biotechnology reduce phosphorus in the nutrient solution of strawberry soilless cultivation systems. Agronomy 2024, 14, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, N.; Caira, S.; Troise, A.D.; Scaloni, A.; Vitaglione, P.; Vinale, F.; Marra, R.; Salzano, A.M.; Lorito, M.; Woo, S.L. Trichoderma applications on strawberry plants modulate the physiological processes positively affecting fruit production and quality. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoud, M.A.; Kordy, A.M.; Abdel-Mageed, A.A.; Heflish, A.I.A.; Sehier, M.M. Impact of chitosan, Trichoderma harzianum, thyme oil and jojoba extract against Fusarium wilt disease of strawberry. J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2020, 25, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiomento, J.L.T.; Stürmer, S.L.; Carrenho, R.; Costa, R.C.; Scheffer-Basso, S.M.; Antunes, L.E.C.; Nienow, A.A.; Calvete, E.O. Composition of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi communities signals generalist species in soils cultivated with strawberry. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 253, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redecker, D.; Schubler, A.; Stockinger, H.; Stürmer, S.L.; Morton, J.B.; Walker, C. An evidence based consensus for the classification of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomeromycota). Mycorrhiza 2013, 23, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutz, J.C.; Morton, J.B. Successive pot culture reaveal high species richness of arbuscular endomycorrhizal fungi in arid ecosystems. Can. J. Bot. 1996, 74, 1883–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.M.; Hayman, D.S. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1970, 55, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouvelot, A.; Kouch, J.; Gianinazzi-Pearson, V. Mesure du taux de mycorhization VA d’un système radiculaire: Recherche of method d’estimation ayant une signification fonctionelle. In Aspects Physiologiques et Génétiques des Mycorhizes; Gianinazzi-Pearson, V., Gianinazzi, S., Eds.; Inra Press: Paris, France, 1986; pp. 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Zenebon, O.; Pascuet, N.S.; Tiglea, P. Métodos Físico-Químicos para Análise de Alimentos, 4th ed.; Instituto Adolfo Lutz: São Paulo, Brasil, 2008; p. 1020. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, M.M.; Wrolstad, R.E. Anthocyanins: Characterization and measurement with UV-visible spectroscopy. In Current Protocols in Food Analytical Chemistry; Wrolstad, R.E., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Basílio, L.S.P.; Borges, C.V.; Minatel, I.O.; Vargas, P.F.; Tecchio, M.A.; Vianello, F.; Lima, G.P.P. New beverage based on grapes and purple-fleshed sweet potatoes: Use of non-standard tubers. Food Biosci. 2022, 47, 101626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybidic-phosphotungstic acid reagent. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika 1958, 23, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal, R.R.; Rohlf, F.J. The comparison of dendrograms by objective methods. Taxon 1962, 11, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reino, J.L.; Guerrero, R.F.; Hernández-Galán, R.; Collado, I.G. Secondary metabolites from species of the biocontrol agent Trichoderma. Phytochem. Rev. 2008, 7, 89–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Schmoll, M.; Esquivel-Ayala, B.A.; González-Esquivel, C.E.; Rocha-Ramírez, V.; Larsen, J. Mechanisms for plant growth promotion activated by Trichoderma in natural and managed terrestrial ecosystems. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 281, 127621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Etesami, H.; Santoyo, G. Trichoderma: A multifunctional agent in plant health and microbiome interactions. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covacevich, F.; Fernandez-Gnecco, G.; Consolo, V.F.; Burges, P.L.; Calo, G.F.; Mondino, E.A. Combined soil inoculation with mycorrhizae and Trichoderma alleviates nematode-induced decline in mycorrhizal diversity. Diversity 2025, 17, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, M.M.; César, S.; Azcón, R.; Barea, J.M. Interactions between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and other microbial inoculants (Azospirillum, Pseudomonas, Trichoderma) and their effects on microbial population and enzyme activities in the rhizosphere of maize plants. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2000, 15, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Medina, A.; Roldán, A.; Albacete, A.; Pascual, J.A. The interaction with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi or Trichoderma harzianum alters the shoot hormonal profile in melon plants. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Li, M.; Fang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Shi, W.; Pan, B.; Wu, K.; Shi, J.; Shen, B.; Shen, Q. Biological control of tobacco bacterial wilt using Trichoderma harzianum amended bioorganic fertilizer and the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi Glomus mosseae. Biol. Control 2016, 92, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, A.; Langrand, J.; Fontaine, J.; Sahraoui, A.L.H. Significance of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in mitigating abiotic environmental stress in medicinal and aromatic plants: A review. Foods 2022, 11, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Qin, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, S.; Zhao, W.; Huang, Z. The interactions between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Trichoderma longibrachiatum enhance maize growth and modulate root metabolome under increasing soil salinity. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Cartabia, A.; Lalaymia, I.; Declerck, S. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and production of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. Mycorrhiza 2022, 32, 221–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M.E.; Martinez, S.I.; Covacevich, F.; Consolo, V.F. Trichoderma harzianum enhances root biomass production and promotes lateral root growth of soybean and common bean under drought stress. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2024, 185, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Smith, F.A. Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizas in plant nutrition and growth: New paradigms from cellular to ecosystem scales. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2011, 62, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eftekhari, F.; Sarcheshmehpour, M.; Lohrasbi-Nejad, A.; Boroomand, N. Effects of mycorrhizal and Trichoderma treatment on enhancing maize tolerance to salinity and drought stress, through metabolic and enzymatic evaluation. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczałba, M.; Kopta, T.; Gastoł, M.; Sękara, A. Comprehensive insight into arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, Trichoderma spp. and plant multilevel interactions with emphasis on biostimulation of horticultural crops. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 630–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, N.P.; Ray, J.G. The inevitability of arbuscular mycorrhiza for sustainability in organic agriculture—A critical review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1124688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosling, A.; Eshghi-Sahraei, S.; Kalsoom-Khan, F.; Desirò, A.; Bryson, A.E.; Mondo, S.J.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Bonito, G.; Sánchez-García, M. Evolutionary history of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and genomic signatures of obligate symbiosis. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitterlich, M.; Rouphael, Y.; Graefe, J.; Franken, P. Arbuscular mycorrhizas: A promising component of plant production systems provided favorable conditions for their growth. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.C.; De Nardi, F.S.; Costa, R.C.; Antoniolli, R.; Stürmer, S.L.; Calvete, E.O. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in strawberry crop systems detected in trap cultures. Acta Hortic. 2017, 1170, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.E.; Bascompte, J.; Kahmen, A.; Niklaus, P.A. Plant choice between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal species results in increased plant P acquisition. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, 0292811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiomento, J.L.T.; De Paula, J.E.C.; De Nardi, F.S.; Trentin, T.S.; Magro, F.B.; Dornelles, A.G.; Anzolin, J.; Fornari, M.; Trentin, N.S.; Rizzo, L.H.; et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi influence the horticultural performance of strawberry cultivars. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, 45410716972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lúcio, A.D.C.; Calvete, E.O.; De Nardi, F.S.; Lambrecht, D.M.; Engers, L.B.O.; Chiomento, J.L.T. Multivariate relationships in strawberry cultivated with native communities of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Acta Sci. Agron. 2025, 47, 70712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Diao, F.; Hao, B.; Xu, L.; Jia, B.; Hou, Y.; Ding, S.; Guo, W. Multiomics reveals Claroideoglomus etunicatum regulates plant hormone signal transduction, photosynthesis and La compartmentalization in maize to promote growth under La stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 262, 115128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2008; p. 1377. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, N.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Deng, L.; Deng, L.; Chachar, M.; Chachar, Z.; Chachar, S.; Hayat, F.; Raza, A.; et al. Symbiotic synergy: How arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance nutrient uptake, stress tolerance, and soil health through molecular mechanisms and hormonal regulation. IMA Fungus 2025, 16, 144989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrassini, V.; Ercoli, L.; Paredes, A.V.A.; Pellegrino, E. Positive response to inoculation with indigenous arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as modulated by barley genotype. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 45, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijdo, M.; Cranenbrouch, S.; Declerck, S. Methods for large-scale production of AM fungi: Past, present, and future. Mycorrhiza 2011, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornari, M.; Pinzon, E.D.S.; Albrecht, G.E.; Deggerone, Y.S.; Trentin, T.S.; Chiomento, J.L.T. On-farm inoculants based on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on wheat performance. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2024, 59, 03662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadieline, C.V.; le Quéré, A.; Ndiaye, C.; Diène, A.A.; Do Rego, F.; Sadio, O.; Thioye, Y.I.; Neyra, M.; Mouhamed, C.; Kébé, F.; et al. Development of on-farm AMF inoculum production for sustainable agriculture in Senegal. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, 0310065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.