Abstract

This study examined the impact of various treatments on the storage quality of sugar-cored ‘Fuji’ apples, with the objective of establishing a theoretical foundation for extending the retention period of these apples and augmenting their commercial worth. This experiment utilized three distinct treatments for sugar-cored ‘Fuji’ apples, with the combination of 1-methylcyclopropene and polyethylene self-sealing bag treatment (1-M+PE) demonstrating the most effective prolongation of the storage duration for the sugar-cored apples. The 1-M+PE treatment significantly mitigated the reduction of sugar-cored in ‘Fuji’ apples and extended the onset of cellular rupture, postponing the loss of firmness and preserving the concentrations of sorbitol and sucrose throughout the storage duration. The 1-M+PE treatment effectively prolonged the storage duration of sugar-cored apples in cold storage. ‘Fuji’ apples subjected to 1-M+PE treatment were stored in cold storage for 120 days. The sugar-cored apple rate was 38.9%. The firmness was 14.8% greater than that of the control group. The soluble solid concentration in the sugar-cored part was 3.83% higher than that of the control group. The reducing sugar content in the sugar-cored part was 16.2% higher than that of the control group, and the titratable acid content in the sugar-cored part was 1.86 times greater than that of the control group. The correlation study of the indicators during the storage period revealed a robust association between the rate of sugar-cored apple and the content of sorbitol, potassium, phosphorus, and calcium. Experimental findings demonstrate that the concurrent application of 1-M+PE significantly inhibits the disappearance of sugar-cored.

1. Introduction

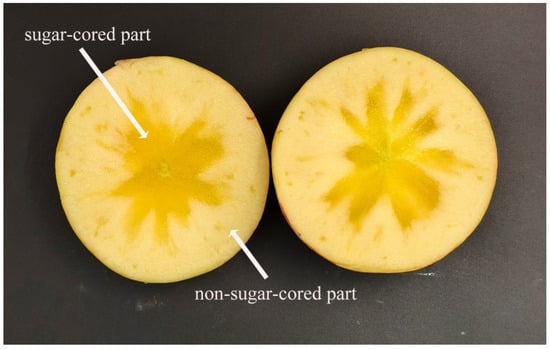

Apple (Malus pumila Mill.) is a perennial deciduous tree in the genus Malus of the Rosaceae family, indigenous to Europe and west-central Asia, with a long history of cultivation. The Aksu ‘Fuji’ apple from Xinjiang, China, is renowned for its crisp texture, sweetness, juiciness, and robust fruit flavor [1]. The distinctive geographical conditions of Aksu, characterized by ample sunlight, significant diurnal temperature variation, and abundant light and thermal resources [2], result in a higher sugar content in apples from this region compared to others, rendering them favored by consumers [3,4]. The tissue adjacent to the core is saturated with water and radiates outward along the apple’s ventricle rays. The interstitial spaces of the flesh cells are filled with a translucent, glassy-looking substance that accumulates, resulting in a water-soaked appearance and a high sugar content, particularly in sorbitol [5]; it is consequently referred to as the sugar-cored apple. Apples with a sugar core (Figure 1). However, as the storage period increases, the sugar concentration in the fruit decreases, and the flesh softens, thereby affecting the quality of the apples and reducing their commercial value [6]. Preserving superior characteristics and enhancing fruit quality has become a pressing concern necessitating urgent investigation and resolution.

Figure 1.

Sugar-cored ‘Fuji’ apple.

1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) directly obstructs ethylene by hindering its perception at the binding site [7]. Research [8,9] indicates that 1-MCP administration can markedly suppress the respiration rate of climacteric fruits, hence postponing or impeding post-ripening senescence. Tian et al. [10] demonstrated that treatment with 1 μL/L 1-MCP significantly suppressed the respiration rate and ethylene release of ‘Granny Smith’ apple fruit during storage. Peng et al. [11] discovered that 1-MCP-treated apples significantly preserved fruit firmness over extended storage, ensuring they retained favorable taste and marketability upon take from the warehouse. Zhang et al. [12] discovered that 1 μL·L−1 1-MCP enhanced apple quality during storage, reduced respiration intensity and fruit decay rate, and elevated fruit firmness and total soluble solids content (SSC). Zhang et al. [13] administered 1.0 μL·L−1 1-MCP to ‘Yue Shuai’ fruits, resulting in a notable enhancement in storage resistance, a reduction in ethylene production, a significant drop in respiration rate, and a postponement of the respiration peak’s onset. The combination of 1-MCP treatment with other interventions yielded positive results. Nock et al. [14] applied 1-MCP therapy to two apple varieties, Mcintosh and Empire, before air-conditioned storage, indicating that early 1-MCP treatment may delay the senescence deterioration of Mcintosh apples and the core browning of Empire apples. Mubarok et al. [15] applied 1-MCP in conjunction with antifolate to tomatoes, resulting in a notable extension of their shelf life.

Polyethylene (PE) self-sealing bags utilized for packing can modulate the microenvironmental gases surrounding fruits, hence improving freshness preservation. The sealing characteristics of PE film enhance CO2 concentration, hence inhibiting fruit respiration and reducing the metabolic depletion of sugar [16]. Chu et al. [17] effectively maintained the sugar content of fresh pomegranate kernels by utilizing polyethylene self-sealing bags for packaging. PE self-sealing bags effectively minimized water loss [18]. Chen et al. [19] discovered that self-sealing bags markedly decreased the cumulative quality degradation of passion fruit. Sun et al. [20] examined the influence of packaging materials on the storage quality of Wenzhou mandarin oranges and discovered that polyethylene (PE) film significantly preserved the organoleptic quality of the fruit, minimized water loss, and maintained a lower CO2 concentration compared to polypropylene film. In this work, we employed 1-MCP treatment in conjunction with a PE self-sealing bag to treat sugar-cored apples, aiming to investigate the alterations in sugar-cored apples during storage and their correlation with relevant indices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The gathering of experimental materials occurred on 9 November 2024, at a commercial farm in the Aksu region of Xinjiang (41°22′ N, 80°48′ E), characterized by significant diurnal temperature variation, abundant sunlight, minimal precipitation, and an arid climate. Subsequent to sampling, the specimens were conveyed to the Xinjiang Production & Construction Group Key Laboratory of Agricultural Products Processing in Xinjiang South at Tarim University. Fruits measuring 80–84 mm in diameter, exhibiting uniform coloration, and devoid of pests and physical damage were chosen for the examination. Place the apples in a cold storage (BF8, BITZER Refrigeration Technology (Shanghai) Co., Shanghai, China) at 4 °C. 1-Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP, C4H6, ≥99.0%) was supplied by Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The permeability coefficients of O2 and CO2 of 0.02 mm PE bag (PE20, 40 60 cm, Jindi Zehao Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) were 1.29 104/(m2·d·atm) and 5.29 104/(m2·d·atm).

At room temperature, four 1 m3 fumigation chambers were constructed using 0.045 mm thick PE film [21]. Sugar-cored apples were randomly divided into four groups, each containing 100 fruits. The fruits were first transferred to the fumigation chambers. Subsequently, two chambers were randomly selected and filled with a 1 µL·L−1 1-MCP solution (weighing 66.0 mg of 1-MCP into a small beaker. Once prepared, add 0.66 mL of water to obtain a 1-MCP gas environment of 1 µL·L−1), then seal. Remove after 24 h (h) of treatment. Two cohorts of unfumigated fruits were segregated into two divisions. One group was assigned to cold storage as the control group (CK), while the other group was packaged in PE20 bags and also kept in cold storage (PE). Subsequently, one set of 1-MCP fumigated fruits was placed straight into cold storage (1-M), whereas the other group was packaged in PE20 bags and then placed in cold storage (1-M+PE). The fruits were stored at refrigerated temperatures for 120 days (d). Samples were collected from fruits under different treatments every 30 d, totaling five cumulative sampling events. The sugary and non-sugary pulps of cubes, each with a side length of approximately 0.2 cm, were picked from six fruits in each replication group and subsequently frozen in liquid nitrogen. The sample is thereafter preserved in a −80 °C freezer (MD-86L718, Hefei Midea Biomedical Co., Ltd., Hefei, China) for future utilization. All measurements were performed on fresh samples, with data expressed as fresh weight (FW).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Fruit Firmness and Sugar-Cored Apple Rate

The GY-1 fruit firmness tester (Zhejiang Top Yunnong Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) was employed to assess fruit firmness. Three fruits were randomly selected, and the peel was cut open at the equatorial plane using a knife. The flesh hardness was measured at three locations on each fruit. The average value was calculated from three replicates [22].

For each processing batch, randomly select 18 fruit samples for cross-sectioning, divided into three replicates. Record and count the number of sugar-core fruits [23]. Apples exhibiting glassy or translucent flesh tissue on the cross-section are classified as sugar-core apples. The calculation formula is as follows:

2.2.2. Soluble Solids Concentration (SSC)

Use the PAL-1 digital refractometer (PAL-1, Atago Co., Tokyo, Japan) to determine the soluble solids concentration of the fruit [24]. Before use, calibrate the digital refractometer with purified water. Take apple pulp samples from three different locations on the fruit, squeeze out the juice by hand, and place a drop into the refractometer’s viewing window. Read and record the data, expressed as a percentage. Repeat the process three times and calculate the average value.

2.2.3. Observation of Paraffin Sections of Fruits

Sample processing was based on the methodology of Zhou et al. [25]. Fixation: fix fruit pulp sections in FAA fixative (70% ethanol: glacial acetic acid: formaldehyde = 90:5:5) for at least 24 h. Paraffin section dewaxing to water: sequentially place sections in xylene I for 20 min, xylene II for 20 min, anhydrous ethanol for 5 min, 75% ethanol for 5 min, then rinse with tap water. Hematoxylin staining: immerse sections in hematoxylin stain for 1–2 h. Rinse briefly with tap water to remove excess dye. Decolorization: decolorize sections in a gradient of 50, 70, and 80% ethanol. Golgi staining: immerse sections in Golgi stain solution for 30–60 s. Rinse in three vats of anhydrous ethanol to dehydrate. Clearing and mounting: Clear sections in n-butanol and xylene for 5 min each. Remove sections from xylene and air-dry briefly. Mount with neutral resin. Examine under a microscope, acquire and analyze images. Optical microscope (CX-21, OLYMPUS, Tokyo, Japan), Microscope Glass Scanner (PANNORAMIC MIDI, 3D HISTECH, Budapest, Hungary).

2.2.4. Titratable Acid Content (TA) and Reducing Sugar Content (RS)

The TA was assessed using acid-base titration [26]. Weigh 5.0 g of the apple sample, grind it, and transfer it to a 50 mL volumetric flask. Constant 50 mL volume, fully stirred. Upon settling, pipette 10 mL of the supernatant, 2–4 drops (10 g·L−1) of phenolphthalein indicator was added, and titrate with 0.01 mol·L−1 NaOH, expressing results as malic acid. The drop to the solution is slightly red; 30 s does not fade; this is the titration endpoint. The volume of 0.01 mol·L−1 NaOH solution consumed was recorded. Perform three replicates and calculate the average value. The unit is g·kg−1 FW.

Weigh 5.0 g of the apple sample, grind it, transfer it to a 250 mL volumetric flask, dilute to the mark, gently shake to ensure full mixing, prepare the test solution, and proceed with the analysis for RS [27]. When the blue color of the solution just faded as the endpoint, the consumption volume of the sample solution was recorded. Perform three replicates and calculate the average value. The unit is g·100 g−1 FW.

2.2.5. Mineral Elements and Monosaccharides

Mineral element contents were measured using an inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometer (AvioTM 200, PerkinElmer Instruments (Suzhou) Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China). Weigh 0.60–1.00 g of the apple sample for analysis. Introduce 3.00–5.00 mL of nitric acid, cover the container, and allow it to stand for one hour or overnight. Secure the vessel cap and execute digestion in accordance with the standard operating method for the microwave digestion system (digestion parameters: 120 °C, heating duration 5 min, isothermal duration 10 min; 150 °C, heating duration 5 min, isothermal duration 10 min; 190 °C, heating duration 5 min, holding duration 30 min). Upon cooling, extract the vessel, gradually open the lid to release gases, rinse the inner lid with a minimal quantity of water, position the digesting vessel in an ultrasonic water bath, and degas through ultrasonication for 2–5 min. Dilute to 50 mL with water, mix comprehensively, and reserve. Perform a concurrent blank test. The Analytical Testing Center of Tarim University conducted this experiment. The unit is mg·kg−1 FW.

High-performance liquid chromatography (LC-20A, Shimadzu Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used for the major monosaccharides, and sample preparation and determination methods were referred to Adila et al. [28]. Take 5.0 g each of the sugar-core and non-sugar-core parts, dilute to 100 mL in an ultra-pure water volumetric flask, sonicate for 30 min, centrifuge at 6500× g for 15 min, aspirate the supernatant, then filter using a needle filter to prepare the sample. Chromatographic conditions: chromatographic column ECOSIL NH2 120A 5 μm (250 mm × 4.6 mm, Guangzhou Lubex Scientific Instrument Co., LTD, Guangzhou, China), the differential refractive index detector (RID), column temperature of 30 °C, injection volume of 10 μL. The flow rate was 1.0 mL·min−1, and the mobile phase acetonitrile to water ratio was 75:25 (v/v). The standard curve was established with the chromatographic peak area as the vertical coordinate and the concentration of monosaccharides as the horizontal coordinate. The unit is mg·g−1 FW. Stability testing and other information can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

2.2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were systematically organized using Excel 2019. Analysis was performed using SPSS 27.0.1 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data visualization was conducted with Origin 2021 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Fruit Firmness and Sugar-Cored Apple Rate

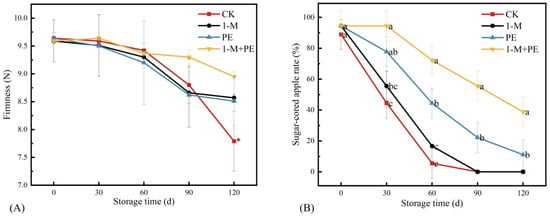

The firmness of apples serves as a crucial indicator for evaluating their storage quality, indicating the degree of softening the fruit undergoes during storage [29]. As the fruit ripens, its internal pectin and cellulose disintegrate, resulting in a steady loss in firmness. Figure 2A illustrates that stiffness consistently diminished with prolonged storage duration. No significant differences were observed among the treatments at the same storage duration. At 120 d, the average firmness of the control group (CK) was lower than that of the other treatment groups, confirming that the three treatments had a certain effect on fruit firmness. The study’s results indicated that the retention of sugar-cored apples diminished over the storage period. In the CK group, the sugar-cored apple rate declined rapidly before 60 d. Compared to the CK, the 1-M treatment influenced the sugar-cored apple rate within the first 30 d. However, this effect diminished in the subsequent period (30–60 d). The 1-M+PE group had the least variation in the percentage of sugar-cored apples, decreasing from 94.4 to 72.2% throughout a storage period of 0 to 60 d, and stabilizing at 38.9% after 120 d of storage. Consequently, it may be inferred that all three treatment groups were effective in mitigating the deterioration rate of sugar-cored apples.

Figure 2.

Firmness (A) and sugar-cored apple rate (B). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among samples at the same time point (p < 0.05). * p < 0.05. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. n = 3.

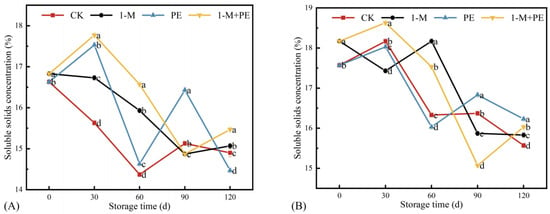

3.2. SSC of Sugar-Cored Apples

Soluble solid concentration (SSC) is a significant quality attribute of fruits [30], and its concentration profoundly influences the nutritional value, flavor, texture, and storage longevity of the fruit. Figure 3 illustrates that the SSC in all groups had a declining trend relative to the measurement at 0 d. During the measurement of the sugar-cored part, at a storage duration of up to 30 d, the groups exhibited significant differences; the 1-M+P, P, and 1-M groups were 13.7, 12.2, and 7.04% higher than the CK group, respectively. At 60 d of storage, the 1-M+P, P, and 1-M groups were 15.3, 10.9, and 1.80% higher than the CK group, respectively.

Figure 3.

Soluble solid concentration in the sugar-cored part (A) and non-sugar-cored part (B). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among samples at the same time point (p < 0.05). Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. n = 3.

The non-sugar-cored part exhibited an accelerated decrease in SSC from 60 to 90 d in the 1-M and 1-M+PE groups. The SSC of the CK group continued to exhibit a fast decrease during the whole storage duration. This outcome resembled the conclusions of Xie et al. [22]. These treatments can affect the SSC during storage, and these contents are different from those of the CK group at 120 d.

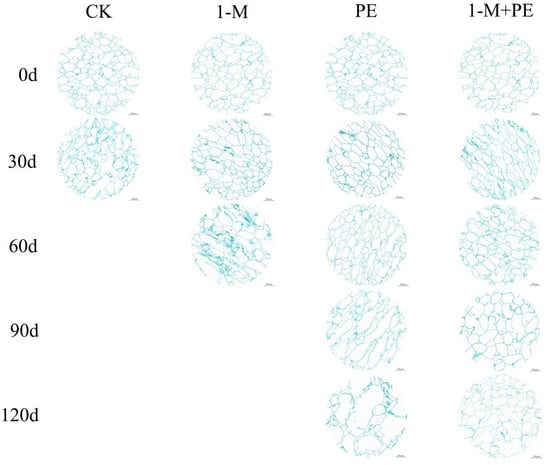

3.3. Observation of Microstructure of Paraffin Sections

The integrity of cell walls and membranes directly influences the resilience of sugar-cored apples [31]. Figure 4 illustrates that at 0 d of storage, the cell morphology across all treatment groups exhibited uniform size and regular organization, with no instances of continuous cell rupture. However, beginning at 30 d of storage, variations in cell size emerged among the treatment groups. After 30 d of storage, the cell morphology in the CK group exhibited enlargement, accompanied by cell rupture, with the fragmented cell walls aggregating into blue cluster-like formations of varying sizes; the 1-M group also displayed enlarged cell morphology, yet without any rupture; the PE group showed an increase in cell size; conversely, the 1-M+PE group did not exhibit obvious changes, maintaining consistent size and regular arrangement of cell morphology. During fruit senescence, the cells transformed from consistently spherical to irregular shapes and altered the intercellular spaces [32]. At 60 d of storage, all sugar-cored in the CK group samples had vanished, meaning the translucent glassy appearance vanished; in the 1-M group, cells in the sugar-cored part had elongated into ellipsoidal shapes and ruptured at cell junctions, exhibiting an irregular arrangement; in the PE group and the 1-M+PE group, cell morphology varied, with some cells enlarging and becoming ellipsoidal, yet maintaining an orderly arrangement without obvious rupture. At 90 d of storage, the sugar-cored part in the samples of the 1-M group had completely vanished. The cell morphology in the PE group exhibited obvious enlargement, with numerous elongated cell strands observed microscopically, indicative of complete disruption of intercellular junctions, leading to the fusion of multiple cells into a larger cell with pronounced gaps. At 120 d of storage, the PE group samples exhibit virtually no sugar-cored parts; at this stage, large cells appear with indistinct forms, irregular cell wall folds, and obvious cell rupture. In contrast, the 1-M+PE group samples show similar cell morphology and size to those observed after 90 d of storage, yet they display increased cell breakage and chaotic arrangement. All three treatments may influence cell stability, with the 1-MCP+PE treatment demonstrating the most obvious effect on the stabilization of fruit cell structure.

Figure 4.

Cross-sectioned apple flesh cells from the sugar-cored part during storage. After the sugar core disappears, sampling becomes impossible, resulting in missing image data. n = 6. Scale bar: 200 μm.

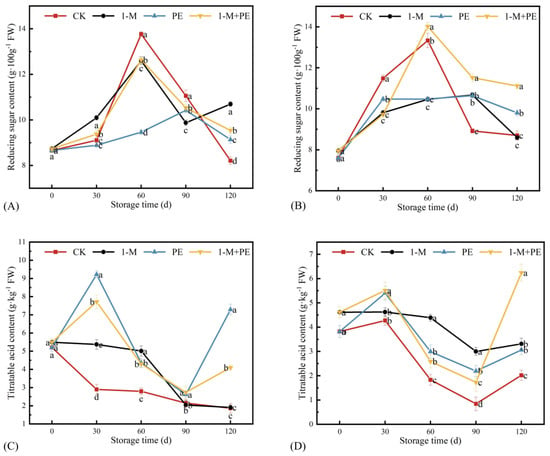

3.4. RS and TA of Sugar-Cored Apples

The alterations in RS among various treatment groups throughout the prolonged storage duration are illustrated in Figure 5A,B. As storage duration increased, the RS of each group initially rose and subsequently declined, aligning with the results reported by Sun et al. [33]. In the sugar-cored part, the RS of the 1-M group was markedly elevated compared to the other three treatment groups at 30 d of storage, while the RS of the CK group was significantly greater than that of the other three treatment groups at 60 d of storage. Subsequently, the RS decreased rapidly in the CK group. The RS of the CK group was markedly lower than that of the other three treatment groups at 120 d of storage. At 120 d storage, the RS were ranked as follows: 1-M group > 1-M+PE group > PE group > CK group. The application of 1-MCP treatment effectively preserves the RS in the sugar-cored part during the later stages of storage. In the non-sugar-cored part, the RS of the CK group was considerably elevated compared to the other treatment groups at the 60 d storage period. Following a storage duration of 60 d, the RS diminished swiftly, reaching a concentration of 8.70 g·100 g−1 FW after 120 d of storage. At the 120 d storage part, the RS were ranked as follows: 1-M+PE group > PE group > CK group > 1-M group. The 1-MCP+PE treatment efficiently maintains the RS in the non-sugar-cored part during the late storage phase. Variations in TA among various treatment groups throughout prolonged storage duration are illustrated in Figure 5C,D. In the sugar-cored part, the contents of the PE and 1-M+PE groups exhibited a pattern of increase, decrease, and subsequent increase relative to the CK group, while the TA of the PE and 1-M+PE groups was considerably elevated compared to the CK group at 120 d of storage. In the non-sugar-cored part, the CK, 1-M, and PE groups exhibited analogous patterns; however, the 1-M+PE group had a considerable increase in TA from 90 to 120 d of storage, with the final TA significantly surpassing that of the other groups. In conclusion, the TA of all treatment groups exceeded that of the control group after 120 d of storage. The PE treatment mitigated the reduction of TA in the sugar-cored part, while the 1-MCP, PE, and 1-MCP+PE treatments inhibited the decline of TA in the non-sugar-cored part, consistent with the findings of Park et al. [34].

Figure 5.

Reducing sugar content in the sugar-cored part (A) and non-sugar-cored part (B). Titratable acid content in the sugar-cored part (C) and non-sugar-cored part (D). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among samples at the same time point (p < 0.05). Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. n = 3.

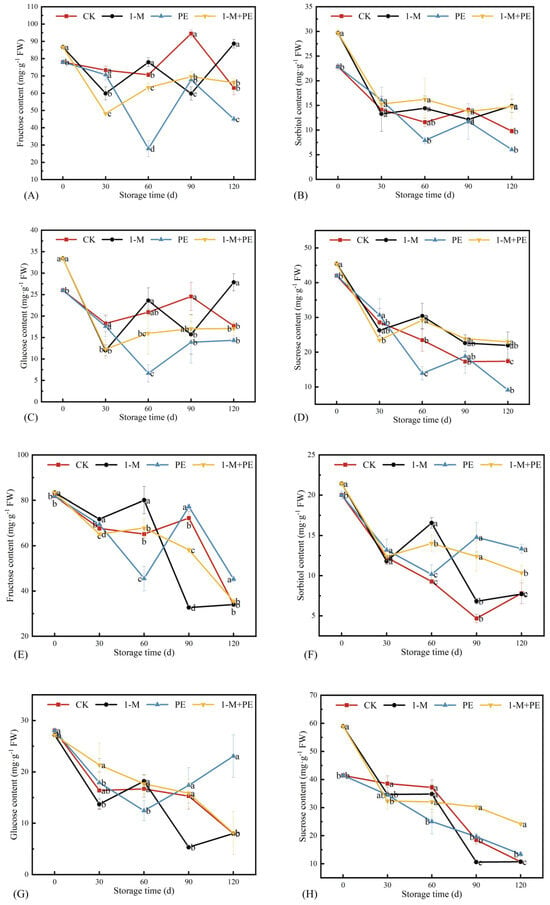

3.5. Monosaccharide Content

Figure 6 illustrates that the concentrations of different monosaccharides in both sugar-cored and non-sugar-cored parts exhibited a declining tendency over extended storage durations, corroborating other research findings [35,36]. The sugar-cored part exhibited a trend of varying concentrations of monosaccharides, initially dropping, followed by an increase, and then dropping again. The fructose levels in each treatment group differed after 30 d of storage, with the CK and PE groups exhibiting significantly increased fructose content compared to the 1-M and 1-M+PE groups (p < 0.05). Upon reaching a storage duration of 60 d, the fructose concentration in the PE group fell significantly by 60.5%. Figure 6A illustrates that the fructose level in the 1-M+PE group exhibited a more gradual variation during the storage period of 60 to 120 d, whereas the fructose content in the CK, PE, and 1-M groups demonstrated more pronounced fluctuations, particularly in the PE group. Sorbitol content varied significantly across groups from 0 to 30 d, exhibiting a reduction of 38.1% in the CK group, 55.3% in the 1-M group, 29.7% in the PE group, and 48.5% in the 1-M+PE group. Following a storage duration of 30 d, distinct tendencies emerged among the treatment groups: the CK and PE groups exhibited a pattern of decline, followed by an increase, and then another decline, whereas the 1-M and 1-M+PE groups demonstrated an initial increase, followed by a decrease, and ultimately a resurgence, maybe attributable to the 1-MCP treatment. The sorbitol contents in the two groups following 1-MCP treatment exhibited a more gradual shift compared to the other two groups. The sorbitol content in the 1-M+P group was 14.7 mg·g−1 FW after a storage duration of 120 d, whereas the CK group exhibited a sorbitol content of only 9.79 mg·g−1 FW. It has been noted that the absence of sorbitol transfer led to water saturation in the tissues around the core, resulting in the vascular bundles exhibiting transparent and glassy appearances around the core [37,38]. At a concentration of 9–11 mg·g−1 FW of sorbitol in the fruit, a large number of sugar cores appeared in the fruit, suggesting that stable and elevated levels of sorbitol may facilitate the preservation of the sugar-cored structure [39]. The maximum glucose concentration of 27.9 mg·g−1 FW was observed in the 1-M group after 120 d of storage. A greater concentration of sucrose was observed in the aqueous nuclear tissues [40]. The sucrose concentration in the 1-M+PE group consistently exceeded that of the other three groups over the storage duration, measuring 23.0 mg·g−1 FW after 120 d of storage. At this time, the 1-M group was 21.9 mg·g−1 FW, the CK group was 17.4 mg·g−1 FW, PE group was 9.1 mg·g−1 FW.

Figure 6.

Changes in fructose (A), sorbitol (B), glucose (C), and sucrose (D) content in the sugar-cored part during storage. Changes in fructose (E), sorbitol (F), glucose (G), and sucrose (H) content in the non-sugar-cored part during storage. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among samples at the same time point (p < 0.05). Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. n = 3.

In the non-sugar-cored part, the general trend of monosaccharide content exhibited an initial decline, followed by an increase, and ultimately a reduction, mirroring the trend observed in the sugar-cored part. Each treatment group exhibited substantial alterations at 30 d storage. Between 30 d and 60 d, the fructose levels in the CK and PE groups commenced a decline, whereas the fructose levels in the 1-M and 1-M+PE groups exhibited a modest increase. Following a 60 d storage period, the fructose levels in the 1-M and 1-M+PE groups began to decline, whereas the fructose content in the CK and PE groups exhibited an increase. Following 120 d of storage, no substantial variation in fructose content was seen across the three groups, with the exception of the PE group (p > 0.05). In the comparison of sorbitol content, the CK group exhibited a declining tendency for the majority of the storage time, while the other three groups demonstrated an initial decrease, followed by an increase, and ultimately a decrease again. The sorbitol concentration in the 1-M+PE group exhibited minimal variation from 30 to 120 d. The sorbitol concentration in the 1-M+PE group remained steady, exhibiting an overall variation of no more than 17%, whereas the PE group had a 45.3% increase from 60 to 90 d. The 1-M group had a sharp increase from 30 to 60 d, succeeded by a fast decline from 60 to 90 d, culminating in a maximum reduction of 58.9%, ultimately stabilizing at 7.7 mg·g−1 FW by 120 d. The glucose levels in the 1-M+PE group consistently declined, while the other three groups exhibited a pattern of initial decrease, followed by an increase, and ultimately a decline. Following 120 d of storage, the PE group exhibited the highest glucose concentration of 23.1 mg·g−1 FW, with no significant differences observed among the glucose levels of the other three groups. The sucrose concentration in the 1-M+PE group consistently exceeded that of the other three groups throughout the entire storage duration. The variation in sucrose content remained relatively stable during the 30 to 120 d storage period, whereas the sucrose levels in the other three groups progressively diminished, with a decline rate surpassing that of the 1-M+PE group. Following 120 d of storage, the 1-M+PE group exhibited the greatest sucrose concentration at 24.2 mg·g−1 FW. The sucrose concentration in the non-sugar-cored part of the 1-M group remained consistently lower during the storage duration, and Xie et al. [41] demonstrated in their research that the 1-MCP treatment inhibited the sucrose levels in apple fruits.

In summary, the 1-MCP+PE treatment effectively preserved the sorbitol and sucrose levels in the fruit, with minimal impact on fructose and glucose. The 1-MCP treatment exhibited an analogous effect on the sorbitol and sucrose levels in the sugar-cored part as the 1-MCP+PE treatment; however, it expedited the reduction of sorbitol and sucrose in the non-sugar-cored part and exerted a more pronounced influence on fructose and glucose in the fruit. The PE treatment expedited the decrease of various monosaccharide levels in the sugar-cored part.

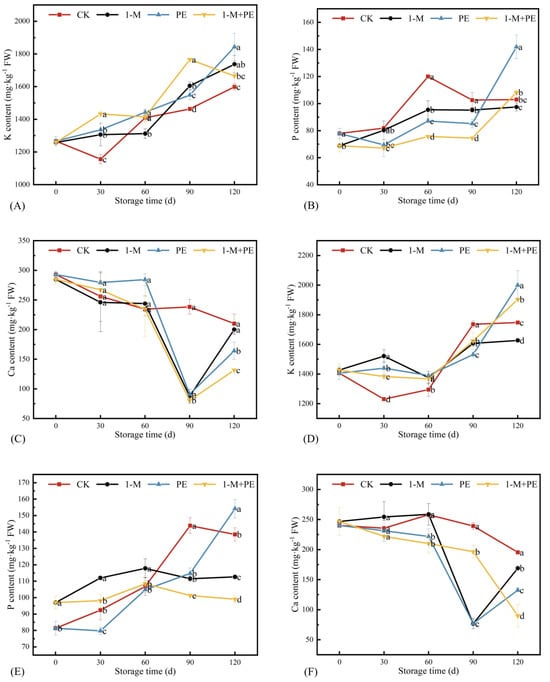

3.6. Potassium (K), Phosphorus (P), and Calcium (Ca) Content

The K content in the 1-M, PE, and 1-M+PE groups exceeded that of the CK group, exhibiting a general upward trend with extended storage duration. Figure 7 illustrates that after a storage period of 60 d, the K content in the PE and 1-M+PE groups was not significantly different from that of the CK group. During the 60 d–120 d storage period, the K content in the PE and 1-M+PE groups was significantly elevated compared to the CK group, although no significant difference was seen with the 1-M group. The K content of the non-sugar-cored parts in the 1-M, PE, and 1-M+PE groups was significantly elevated compared to the CK group during the 30 to 60 d of storage. Specifically, at 30 d of storage, the increases were 23.6, 17.0, and 12.4%, respectively, and at 60d of storage, the increases were 6.21, 7.39, and 5.62%, respectively.

Figure 7.

Changes in K (A), P (B), and Ca (C) content in the sugar-cored part during storage. Changes in K (D), P (E), and Ca (F) content in non-sugar-cored part during storage. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among samples at the same time point (p < 0.05). Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. n = 3.

At 30 d of storage, the P content in the sugar-cored part was much lower in the PE group and the 1-M+PE group compared to the CK group and the 1-M group, and this condition persisted until 90 d. At 90 to 120 d of storage, the P content in the sugar-cored part of the PE group and the 1-M+PE group grew, greatly surpassing that of the CK group at 120 d, with values of 37.8% and 5.08%, respectively. Consequently, it was posited that the P content would influence the sugar-cored, aligning with the findings of the study conducted by Jia et al. [42].

Ca is a crucial constituent of the plant cell wall, providing significant protection for the integrity of the cell membrane and reducing oxidative damage. The Ca content of the sugar-cored part exceeded that of the non-sugar-cored part, corroborating the results of Jia et al. [42]. As storage duration increased, there was a general decline in the Ca content of the sugar-cored part. Throughout the storage duration of 0 to 60 d, no notable variation in Ca content was seen across the treatment groups. Throughout the 60 d–90 d storage period, the Ca content in the 1-M group, PE group, and 1-M+PE group exhibited substantial differences from the CK group, with a notable drop compared to the CK group. Despite the increase in Ca content during the storage period of 90 to 120 d, the Ca content in the PE group and the 1-M+PE group remained significantly lower than that in the CK group. The Ca content of the PE and 1-M+PE groups was 21.9% and 37.4% lower than that of the CK group after a storage period of 120 d, respectively. Upon examining the Ca content in the non-sugar-cored part after a 30 d storage period, distinct variations were noted among the three treatment groups. The Ca content in the 1-M, PE, and 1-M+PE groups was considerably lower than that in the CK group from 60 to 120 d. At 120 d of storage, the Ca content in the 1-M, PE, and 1-M+PE groups was reduced by 13.5, 32.2, and 54.0%, respectively, compared to the CK group. After a 90 d storage period, the Ca content in the 1-M and PE groups was considerably lower than that in the 1-M+PE group. Specifically, when comparing the alterations in Ca content between the PE and 1-M+PE groups during the 60 to 90 d of storage, the trend in the sugar-cored part was consistent across both groups. However, in the non-sugar-cored part, the Ca content in the 1-M+PE group exhibited greater stability and was significantly elevated compared to the PE group, while the pronounced fluctuations in Ca content within the PE group could potentially influence the changes in its sugar-cored part. At 120 d of storage, the Ca content in the 1-M+PE group was considerably lower than that in the PE group for both sugar-cored and non-sugar-cored parts. With regard to the trend of Ca content, all treatment groups, excluding the control group, had a similar pattern.

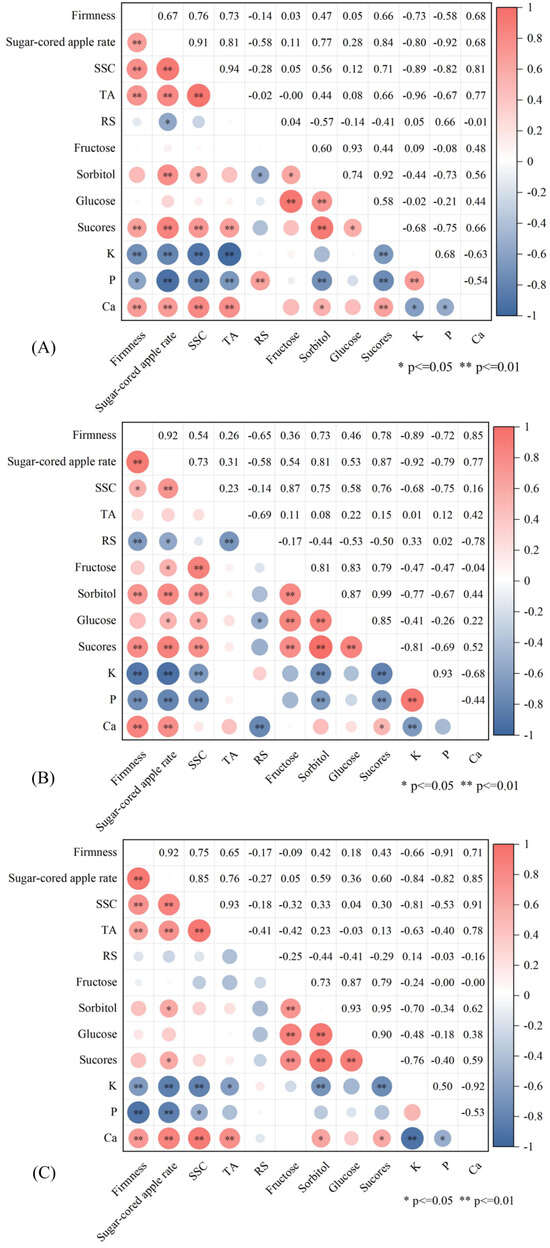

3.7. Correlation Analysis

The analysis of correlations among indicators demonstrates substantial linkages between numerous factors. For indicators exhibiting elevated correlation coefficients in the 1-M group (Figure 8A): The correlation coefficient between sugar-cored apple rate and P was −0.92. The sugar-cored apple rate and SSC were 0.91. The SSC and TA were 0.94. TA and K were −0.96. Sorbitol and sucrose were 0.92. The correlation coefficient in the PE group (Figure 8B) between firmness and sugar-cored apple rate was 0.92; sugar-cord apple rate and K were −0.92; sorbitol and sucrose were 0.99; K and P were 0.93. In the 1-M+PE group (Figure 8C), the correlation coefficient between firmness and sugar-cored apple rate was 0.92; firmness and P was −0.91; SSC and TA was 0.93; SSC and Ca was 0.91; sorbitol and fructose was 0.93; sorbitol and sucrose was 0.95; fructose and sucrose was 0.90; K and Ca was −0.92. Of the four principal monosaccharides, sorbitol and sucrose had elevated correlation coefficients with the sugar-cored apple rate. In the three treatment groups, the association between sorbitol and sucrose was notably strong, with values above 0.90. The correlation coefficients for the sugar-cored apple rate in relation to SSC, Ca, P, and K exceeded 0.70, whereas those for RS and fructose were very low.

Figure 8.

Correlation analysis among results of group 1-M (A), group PE (B), and group 1-M+PE (C). n = 3.

The fructose content in Fuji apples is comparatively elevated [43]; however, studies demonstrate that fluctuations in fructose levels exert little influence on the sugar-cored apple rate. Ca, an essential element of plant cell walls, significantly contributes to the preservation of cell membrane integrity and the reduction of oxidative damage [44], a conclusion strongly supported by the correlation study between Ca and firmness. Jia et al. [42] research indicates that P is essential for the production of sugar cores. The results demonstrate a substantial negative association between P and the sugar-cored apple rate. Variations in P inside the sugar-cored part significantly affect sugar-cored development. Consequently, P is considered a key factor in sugar-cored elimination during storage. Nonetheless, the exact mechanisms regulating the impacts of these mineral constituents within fruit have yet to be clarified. The accumulation of sorbitol in the core region results in sugar-cored apples [45]. During storage, sorbitol in the fruit is predominantly enzymatically transformed into fructose and glucose, leading to elevated concentrations of these sugars over time. We assume that the disappearance of sugar cores correlates with sorbitol metabolism, in accordance with the research conducted by Bai [46]. Our results demonstrate a robust link between sorbitol and sucrose. The examination of variations in sorbitol and sucrose contents inside the sugar-cored region indicates a substantial correlation with the occurrence of sugar-core fruit. Therefore, this study suggests that sorbitol metabolism and sucrose metabolism may play roles in sugar-cored disappearance. This study indicates that further research on sugar metabolism may be necessary to prolong the storage time of sugar-cored apples and postpone the loss of the sugar core.

4. Conclusions

Experimental results indicate that all three treatment groups could delay the disappearance of the “sugar-cored.” The 1-MCP+PE treatment demonstrated better substantial advantages, with the sugar-cored apple rate reaching 38.9% following 120d of storage. This treatment preserved cellular morphological integrity, delayed cellular rupture in apple tissues, and enhanced fruit firmness. However, the TA and RS showed varying results across different treatments at different time points. Compared with the CK group, 1-M+PE treatment maintained lower Ca and P content throughout the storage period. Based on the analysis of experimental and correlational data, this study proposes that sugar metabolism may reduce the sugar-cored apple rate. Furthermore, the contents of K, P, and Ca appear to influence sugar-cored apple rate, although their precise mechanisms require further research. In summary, the application of 1-MCP+PE to sugar-cored ‘Fuji’ apples improved their quality, augmented storage resilience, and prolonged freshness duration.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12010030/s1, Table S1: Stability Testing. n = 5; Table S2: Recovery Test. n = 5; Table S3: Standard curve. LOD, S/N = 3; LOQ, S/N = 10.

Author Contributions

K.L.: Writing—original draft and data curation. Y.W.: Software, Data curation. Y.P.: Visualization, Investigation. B.X.: Visualization, Investigation. L.W.: Visualization, Investigation. Y.H.: Visualization, Investigation. X.H.: Writing-review and editing, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Industrial Technology Innovation Team Support Program (Apple Storage and Deep Processing Position System) grant (XJLGCYJSTX04-2024-14), Tarim University Graduate Student Scientific Research Innovation Project (TDGRI202310), President’s Fund Project of Tarim University (TDZKBS202305), and Xinjiang Autonomous Region Talent Development Fund-“Tianchi Elite” Recruitment Program for Young Doctoral Scholars (524313001).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, X.; Li, B.; Du, R.; Hou, X.; Li, J.; Xie, B. Effects of Temperature on Storage Quality and Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism of Postharvest Aksu “Red Fuji” Apples. North. Hortic. 2024, 9, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, H.; Okumura, T.; Miyazaki, Y.; Amano, S. Seasonal changes in cellular compartmentation and membrane permeability to sugars in relation to early or high temperature-induced watercore in ’Orin’ apples. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2006, 81, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Dong, C.; Ji, H.; Chen, C.; Yu, J.; Zhang, N.; Liang, L. Effect of precise temperature control on postharvest physiological quality of Aksu apples. Food Ferment. Ind. 2023, 49, 284–289. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Lin, Q.; Luo, Z.; Ban, Z.; Li, X.; Reiter, R.J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Liang, Z.; Qi, M. Ongoings in the apple watercore: First evidence from proteomic and metabolomic analysis. Food Chem. 2023, 402, 134226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L. Assay on Sugars, Acid and Polyphenols of Red Fuji Apple in Chinese Main ProductionArea and Models of Reginal Authenticate. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2023, 44, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Yuan, J.; Zheng, Y.; Duan, L.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y. Heat shock pretreatment and low temperature fluctuation cold storage maintains flesh quality and retards watercore dissipation of watercored ‘Fuji’ apples. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 323, 112492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisler, C.E.; Dupille, E.; Serek, M. Effect of 1-methylcyclopropene and methylenecyclopropane on ethylene binding and ethylene action on cut carnations. In Plant Hormone Signal Perception and Transduction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Sisler, C.E.; Serek, M. Compounds Interacting with the Ethylene Receptor in Plants. Plant Biol. 2003, 5, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Blankenship, S.M.; Mattheis, J.P. 1methylcyclopropene inhibits apple ripening. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1999, 124, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Wu, H.; Wang, L.; Tian, X.; Li, R.; Qi, Y.; Ren, X. Effect of 1- MCP treatment on chlorophyll degradation in postharvest ‘Granny Smith’ apple fruit. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 37, 734–742. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z.; Ye, Q.; Xu, X.; Fu, D. Effect of 1-methylcyclopropene treatment on storage quality of red Fuji apple. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Agric. Life Sci.) 2020, 46, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Du, M.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Ban, Z.; Jiang, Y. Practical 1-Methylcyclopropene Technology for Increasing Apple (Malusdomestica Borkh) Storability in the Aksu Region. Foods 2024, 13, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Yi, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G. Effects of 1-MCP on Respiratory Rate and Storage Quality of “Yueshuai” Apples. North. Hortic. 2011, 20, 160–162. [Google Scholar]

- Nock, J.F.; Watkins, C.B. Repeated treatment of apple fruit with 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) prior to controlled atmosphere storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 79, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarok, S.; Kusumiyati, K.; Hamdani, S.J.; Wicaksana, N.; Jaya, I.H.M.; Budiarto, R.; Sugiarti, L.; Ariestanti, M.D.; Nuraini, A. Combination effect of 1-Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) and Ascorbic Acid (AsA) in maintaining postharvest life and quality of tomato fruit. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 19, 101580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Zhang, B.; Pan, L.; Tang, S.; Zhou, X.; Liang, J. Influence of Storage Containers and Packaging Materials on the Storage Quality of Passion Fruit at Room Temperature. Storage Process 2023, 23, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, L.; Wang, Q.; Wng, M.; Kou, L. Effect of PE Film Thickness on Preservative Effect of Ready-to-eat Pomegranate Seeds. Storage Process 2017, 17, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.; Man, J.; Zheng, L.; Jin, P.; Zhang, S. Effects of Different Packaging Materials on Preservation of Fresh-cut Celery. Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2020, 21, 224–227. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Xiong, Z.; Pang, T. Effects of modified atmosphere packaging on quality of passion fruit during storage. Food Sci. 2016, 37, 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Chen, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, J.; Shao, X.; Xia, B. Effects of packaging materials on storage quality of Citrus unshiu. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019, 21, 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, N.; Liu, R.; Zhang, N.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, R. Effect of 1-MCP Combined with Spontaneous Modified Atmosphere Bag on Postharvest Storage Quality of Passion Fruit. Packag. Food Mach. 2023, 44, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, S.; Bai, Y.; Du, L.; Ma, N.; Li, D.; Li, X. Effects of 1-MCP treatment on storage quality of Aksu Fuji apple in different harvest time. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2017, 38, 292–296+307. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Wang, W.; Hang, B.; Tong, W.; Wang, Z.; Jia, X. Relationship of Carbohydrate, Mineral Content, Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism and ‘Fuji’ Apple Watercore Occurred. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2015, 42, 2023–2030. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, L.; Yuan, S.; Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, L.; Cao, J. Study on storability of plums of different cultivars at low temperature storage. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2014, 35, 343–345+350. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, D.; Nu, M.; Xiong, C. Quality analysis of “Sugar Core” ‘Fuji’ apple in Aksu. J. Tarim Univ. 2019, 31, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Zan, J.; Hou, B.; Li, H.; Hu, D. Optimization of applee moldy core disease model by fusion of total soluble solids and titratable acidity with NIRS. Microchem. J. 2025, 217, 115065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Y.; Chai, L.; Lu, Z.; Shi, J.; Xu, Z. Analysis of physicochemical indexes, antioxidant activity and flavor characteristics of apple cider vinegar from different sources. China Brew. 2023, 42, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Adila, A.; Pu, Y.; Dang, Y. Simultaneous determination of fructose, sorbitol, glucose and sucrose in apple fruits by HPLC-RID. Agric. Prod. Process. 2021, 22, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Le, L.; Xia, X.; Long, Y.; Chen, D.; Gao, L.; Zeng, X.; Li, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, J.; He, H. Effects of ozone treatment on postharvest storage quality and sterilization of late-maturing citrus. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 40, 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Poonam; Rajnish, S.; Parul, S.; Sharma, N.C.; Kuldeep, K.; Nand, K.S.; Vinay, B.; Narender, N.; Neena, C. Exploring genetic diversity and ascertaining genetic loci associated with important fruit quality traits in apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2023, 29, 1693–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, H.J.; Jobling, J.J. Contrasting the structure and morphology of the radial and diffuse flesh browning disorders and CO2 injury of “Cripps Pink” apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2009, 53, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotsmans, W.; Verlinden, B.E.; Lammertyn, J.; Nicolai, B.M. The relationship between gas transport properties and the histology of apple. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2004, 84, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, J.; Paerhati, M.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J. Nutrient Composition Changes in Different Grades of Aksu Ice Sugar Heart Apples Under Low-Temperature Storage Conditions. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2023, 60, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.; Shoffe, Y.A.; Algul, E.B.; Engelgau, P.; Beaudry, M.R.; Watkins, B.C. Preharvest application of 1-methylcyclopropene and 1-aminoethoxyvinylglycine affects watercore severity and volatile profiles of ‘Fuji’ apples stored in air and controlled atmospheres. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 211, 112840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. Study on the Difference of Quality and ConsumerAcceptance of Fuji Apple under Different Storage Conditions. Master’s thesis, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J. Study on the Mechanism of the Disappearance of the Sugary Corein Aksu Sugary Core Apples during Postharvest Storag. Master’s thesis, Tarim University, Alar, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Marlow, G.C.; Loescher, W.H. Watercore. Horticulture 1984, 6, 189–251. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kang, I.K.; Nock, J.F.; Watkins, C.B. Effects of preharvest and postharvest applications of 1-methylcyclopropene on fruit quality and physiological disorders of ‘Fuji’ apples during storage at warm and cold temperatures. Hortscience 2019, 54, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. Study in the Formation Mechanism of “Sugar Core” Apple in Aksu. Master’s thesis, Tarim University, Alar, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, J.H.; Watkins, C.B. Fruit maturity, carbohydrate and mineral content relationships with watercore in ‘Fuji’apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1997, 11, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, S.; Bai, Y.; Du, L.; Ma, N.; Li, D.; Li, X. Effect of 1-MCP Treatment on Sugar Metabolism in Aksu Fuji Apples Harvested at Different Stages and Stored for Different Periods. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 111–121+214. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, P.; Wang, J. Aksu candied apple primary metabolites and mineral elements. J. Tarim Univ. 2021, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Gene for Important Differential Metabolites Between Sweet Core and Non Sweet Core of Aksu Fuji Apple. Master’s thesis, Tarim University, Alar, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Du, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Song, J.; Jia, X.; Wang, L. Effect of pulsed controlled atmosphere with CO2 on the quality of watercored apple during storage. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 278, 109854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shen, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, C. A sorbitol transporter gene plays specific role in the occurrence ofwatercore by modulating the level of intercellular sorbitol in pear. Plant Sci. 2022, 317, 111179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X. Study on the Regulation of Post-harvest Quality of Aksu Red FujiApples through Exogenous Calcium Treatment. Master’s thesis, Tarim University, Alar, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.