Abstract

Plant seed number depends on ovule number initiated within the carpels, and it serves as a primary factor shaping fruit yield. Pomegranate trees exhibit bisexual flowers and functional male flowers. Pomegranate have anatropous ovules which are bitegmic and crassinucellate. Bisexual flowers possess the fertile pistil, while functional male flowers have abnormally developed ovules, a small ovary with few chambers, and a short style. The formation of functional male flowers is due to abnormal and stagnant development of ovule integument. Ovule number directly determines the yield of pomegranate seeds. Recent studies have highlighted the molecular mechanisms through which ovule-related genes regulate pomegranate ovule development. Pomegranate PgCRC and PgINO genes positively regulate the increase in the number of ovules, and PgBEL1 to synergistically regulate seed development. PgAGL11 (the SEEDSTICK orthologous gene) promotes ovule development in transgenic Arabidopsis. PgSEP protein can bridge interactions among PgBEL1, PgSTK and PgAG, which regulate ovule development. At the level of post-transcriptional regulation, PgmiRNA167, PgmiRNA164 and PgmiRNA160 are differentially expressed during pomegranate flower development, and PgmiR166a interacts with its target genes to affect ovule development. This review summarizes the key regulators of ovule development and their molecular pathways, integrating these interactions into a model that describes pomegranate ovule development.

1. Introduction

In flowering plants, the ovules upon fertilization develop into seeds. Understanding the mechanisms regulating ovule number and development is essential, as these factors ultimately determine seed number and, thus, yield. Pomegranate trees produce bisexual and functional male flowers [1]. Bisexual flowers have fully developed gynoecia with numerous anatropous ovules. But ovules in functional male flowers are rudimentary, shriveled and exhibit various stages of degeneration [1,2,3]. Previous research has shown that ovule primordia, along with the outer and inner integument primordia, are formed in bisexual flowers. The integuments initiate as circular ridges at the nucellus base and grow upward to encase it, and the outer integument rapidly grows to completely enclose the inner integument [3,4]. However, integument primordia are not observed in functional male flowers [3,4,5]. The number of ovules in flowers can influence the aril number and fruit size in pomegranate. The aril is the edible tissue of pomegranate, which is derived from the outer integument [5]. Therefore, investigating the mechanisms regulating ovule development has become a significant research area in plant science. The pomegranate genome has provided the data foundation for the ovule development research [6,7]. Based on previous findings, we constructed a regulatory network involving CRC (CRABS CLAW), INO (INNER NO OUTER), BEL1 (BELL1), and MADS-box genes that govern pomegranate ovule development [4]. Furthermore, microRNAs (miRNAs) have been implicated in pomegranate ovule sterility at the level of post-transcriptional regulation [8]. The functions of transcription factors and miRNAs in pomegranate flower and seed development and their regulatory relationships have been studied in previous research [3,4,6,7,8]. Ovule development determines ovule number and seed characteristics, and this research lays the foundation for breeding large-fruited pomegranate varieties with plump seeds and high juiciness. In this review, we summarize the current understanding of both molecular and hormonal mechanisms that regulate pomegranate ovule formation and development.

2. Overview of Ovule Development in Plants

Seed number depends on the number of ovules initiated within the carpels. Ovule number is determined by ovule spacing and the length of the placenta [9]. Flower fertility and ovule number are the crucial factors determining yield. Plant ovule development has been extensively studied in detail. Arabidopsis thaliana flower development is divided into 20 stages, with ovule development primarily occurring during stages 9–12 [10,11]. Plant ovule development includes ovule cell fate determination, the ovule primordium initiation and ovule morphogenesis [9,12,13]. Periclinal cell divisions within the placenta sub-epidermal tissue initiate ovule primordium formation at stage 9, megaspore mother cells (MMCs) are identified at stage 10, integument initiation and megasporogenesis are observed at stage 11, and the embryo sac develops at stage 12 [14,15]. In A. thaliana, ovule primordia are formed in carpel medial meristem (CMM) as lateral organs from the placenta [16,17]. The critical step in ovule development is to determine the number and position of ovule primordia in the CMM [9]. Ovule primordia arise from the placental tissue at stage 10. Ovules are finger shaped, and their number and shape at each placenta show only minor differences [11]. The outer and inner integuments develop from the chalaza. The outer integument presents asymmetrical growth by heightened cell divisions on the side facing the central septum. The outer and inner integuments grow upward, gradually enclosing the nucellus. By the stage of maturity, the outer integument has fully overgrown the inner integument. The faster growth of the abaxial integuments induces curvature in the developing ovules [18]. The integuments, of sporophytic origin, ultimately form the seed coat. While the ovules in petunia and tomato possess a single integument, Arabidopsis forms two integuments [19,20].

In recent decades, several research studies have identified genes involved in ovule initiation, ovule identity determination and development in some species, such as A. thaliana, petunia, rice, and tomato (Table 1) [11,21,22,23,24]. ANT (AINTEGUMENTA) has been verified to promote ovules and floral organ initiation [25,26]. CUC (CUP SHAPED COTYLEDON) transcription factors, CUC1, CUC2 and CUC3, are expressed in boundaries of aboveground organ primordia, and CUC2 has been verified to regulate ovule initiation [13,27]. OsPID (OsPINOID) plays a crucial role in the regulation of rice stigma and ovule initiation [28]. In Arabidopsis, EPFL1 (Epidermal Patterning Factor-Like1) and EPFL2 promote ovule initiation and nascent ovule elongation. EPFL1 and EPFL2 synergy with CUC boundary genes regulates ovule number and shape [9]. Key genes such as BELL1 (BEL1), SEEDSTICK (STK), SHATTERPROOF (SHP), and AGAMOUS (AG) have been identified as being involved in determining ovule identity [21,29]. Mutations in AG homologues, rice osmads13 mutant, petunia fbp7/fbp11 double mutant and stk/shp1/shp2 triple mutant in Arabidopsis, lead to homeotic transformation of ovules into carpels [21,22,29,30,31]. VvAGL11 (AGAMOUS-LIKE11, an ortholog of Arabidopsis STK), is negatively regulated by VvBPC1 (BASIC PENTACYSTEINE), and VvBPC1 protein interacts with VvBELL1, regulating grape seed development [32]. BEL1 interacts with the ovule identity MADS-box factors (STK and SHP) when they dimerize with SEPALLATA (SEP) proteins [33]. Ovule integument development is regulated by intricate genetic interactions, such as INO and ANT, and establishing their expression regions in early ovule primordia is crucial for integument formation [34,35,36]. CRC has been verified to play a vital role in ovule primordia initiation, differentiation and development [17,24,37,38]. Additionally, TCP4 protein interacts with AG, SEPALLATA3 (SEP3) and BEL1 to strengthen the connection of BEL1 with AG-SEP3 [39]. This research in model plants can be used as reference for ovule development of woody plants.

Table 1.

The list of key genes of ovule development in plants.

3. Key Genes Involved in Pomegranate Ovule Development

Pomegranate fruit bears many ovules, and can therefore serve as a representative system for ovule development studies in fruit trees. Previous studies have confirmed that INO, CRC, BEL1, NST, and MADS-box genes (such as STK, SEP and AG) are involved in regulating ovule development in pomegranate (Table 2) [4,83,84].

Table 2.

The list of key genes of ovule development in pomegranate.

3.1. BEL1—A Regulator of Pomegranate Ovule Development

BELL is a critical regulator of ovule development. BEL1 is expressed throughout the ovule primordia in the initial stages, and BEL1 is essential for INO expression [85]. Ovules of the bel1 mutant lack the inner integument and exhibit abnormal development of the outer integument. In ovule development, BEL1 negatively regulates AG gene expression [40], and the loss of AG regulation in the bel1 mutant results in the conversion of ovule into carpels [86,87]. In outer integument development, BEL1 forms the protein complex with AG and SEP to regulate INO expression [33]. BEL1 is required for proper morphogenesis of the ovule integuments.

Our previous studies have demonstrated that PgBEL1 was highly expressed in the inner and outer seed coat [88]. Specifically, when the bud vertical diameter was 5.1–12.0 mm, PgBEL1 expression levels were significantly higher in bisexual flowers than those in functional male flowers. The expression level of PgBEL1 in bisexual flowers was 16.6 times higher than that in functional male flowers at a bud vertical diameter of 5.1–8.0 mm, 2.4 times at 8.1–10.0 mm, and 1.8 times at 10.1–12.0 mm [89]. To investigate the function of PgBEL1, transgenic lines of overexpression PgBEL1 was constructed [90]. The siliques of overexpression PgBEL1 A. thaliana lines normally developed, and seed numbers were substantially lower than in the wild-type (WT). This result contradicts other findings reports [85,86,87], which may be due to the heterologous expression, species-specific interactions or altered meristem identity. So pomegranate transgenic is necessary to verify the gene’s function.

To explore the relationships between INO, CRC, BEL1, and SEP, their expression patterns in flowers, siliques, stems, and leaves of WT and overexpression PgBEL1 transgenic lines were investigated (Supplementary Figure S1). In flowers, AtCRC expression level in overexpression PgBEL1 lines were significantly higher than that in WT. During young leaf development, AtINO and AtCRC transcriptional levels in overexpression PgBEL1 were significantly higher than that in WT. In young siliques of overexpression PgBEL1 transgenic lines, the expression levels of AtINO and AtSEP3 were higher than those in WT. These results suggested that PgBEL1 enhances the expression of AtINO and AtSEP3 at the transcript level during early silique development.

3.2. MADS-Box Genes—The Regulators of Ovule Identity and Development in Pomegranate

In Arabidopsis, STK, SHP1, SHP2, and AG have been identified as key regulators of ovule identity, with AG, STK and SHP playing redundant roles in promoting ovule development [21]. Our previous studies demonstrated that PgSEP1, PgSEP3a, PgSEP3b, PgSTK, and PgSHP were highly expressed in both the functional male flower and bisexual flower [91]. AG showed differential expression pattern between functional male and bisexual flowers of pomegranate during key stages of ovule development [3]. Overexpression of PgAGL11 leads to phenotypes such as shortened stamens, a thicker style, and elongated mastoid cells on the stigma surface. PgAGL11 (STK orthologous gene) expression level is notably higher in bisexual flowers compared to that in functional male flowers, which suggested that PgAGL11 regulates ovule development in pomegranate [83]. RT-qPCR analysis further revealed that PgSTK expression levels in bisexual flowers were higher than those in functional male flowers (Supplementary Figure S2). At pomegranate ovule sterility stages (P3–P5, 8.1–14.0 mm), the expression level of PgSEPs in bisexual flowers is higher compared to that in functional male flowers. These results indicate that PgSTK and PgSEPs are involved in pomegranate ovule development.

The regulatory relationships between BEL1, AG and STK have been elucidated [33]. In addition, the interaction between BEL1 protein and the AG-SEP dimer is necessary to suppress the carpel identity function of AG during ovule integument development [33]. In pomegranate, PgBEL1 could not interact with PgAG and PgSTK at the protein level [4]. SEP is crucial for the ovule development; it is actively involved in the formation of MADS-box protein higher-order transcription factor complexes [92]. Without SEP proteins, the ovule identity complex fails to form, consequently preventing the initiation of the ovule identity pathway [93]. Our results confirmed that PgSEPs protein interacts with PgAG, PgSTK and PgBEL1 [4]. In pomegranate, there was no protein correlation between PgBEL1, PgSTK and PgAG. PgSEP functioned as the molecular interaction that bridged PgBEL1 and MADS-box genes to regulate pomegranate ovule development.

The stem cell maintenance gene WUS (WUSCHEL) plays a vital role in specifying nucellus identity and indirectly regulating integument formation [33,34,94,95]. The suppression of WUS by AG is primary for terminating floral meristem activity, and WUS can induce AG expression in developing flowers [96,97]. WUS is ectopically expressed in the chalaza of bel1 mutant, indicating that the AG-SEP-BEL1 complex restricts WUS expression domain [33]. In a previous study, we demonstrated that PgWUS expression was higher in bisexual flowers than in functional male flowers (bud vertical diameter: 5.1–10.0 mm), and PgWUS expression in pistils was 1.5 times that in the stamens of pomegranate flowers [89]. WUS expression serves as a marker for nucellus determination in the ovule, and the WUS protein acts non-cell autonomously to regulate integument growth [17,34]. In pomegranate, PgWUS protein could interact with PgBEL1 and PgAG [4]. These results suggest that PgWUS is involved in the regulation pathway of pomegranate flower and ovule development.

3.3. INO and CRC Genes—The Positive Regulator of Pomegranate Ovule Development

The Arabidopsis YABBY family member INO is essential for formation of the outer integument [44,98,99], and the ovules of ino mutants are without outer integument [85]. INO is specifically expressed in the abaxial layer of the outer integument [17]. During ovule development in Arabidopsis, the growth of the outer integument occurs primarily to the side of the ovule facing the gynoecium basal region. This asymmetry is regulated by SUP, which restricts INO expression to the basal side of the gynoecium [100]. CRC can substitute for INO in promoting integument development, but CRC does not respond to SUP regulation [101]. Recent research has confirmed that brassinosteroids (BRs) regulate the outer integument development partially by BZR1-mediated INO transcriptional regulation [102]. VviINO, a gene homologous to INO in Vitis vinifera, partially complements the asymmetric growth of outer integument in ino mutants [45]. In pomegranate, PgINO was expressed in the vital developmental stages (5.1–25.0 mm) of bisexual flowers [103]. INO showed down-regulation in functional male flowers at the key stage of ovule development cessation [3]. Functional studies have confirmed that PgINO is involved in the development of flower organs and seeds [4]. PgINO protein interacted with the ovule identity factors PgBEL1, whereas PgINO could not interacte with MADS-box proteins [4]. These results showed that PgINO plays a critical role in regulating the differentiation of ovule and seeds.

CRC functions as the transcriptional activator in carpel closure and nectary development, and is also involved in floral meristem termination by transcriptional repression [104]. It plays a critical role in proper gynoecium growth [105]. The crc mutation consistently reduces stylar growth and results in the carpels’ incomplete medial fusion [105,106]. Arabidopsis carpels of crc mutants are broader, shorter, and contain fewer ovules, indicating that CRC is involved in ovule primordia initiation [105,106,107]. In tomato, SlCRCa and SlCRCb operate as positive regulators of floral meristem determinacy [108]. CRC and INO, combined with KAN (KANADI) and ETT (ETTIN), regulate the adaxial–abaxial patterning of carpels [109]. PeDL1 (the gene homologous to CRC in orchids) overexpression causes ovules abnormal development [37]. The complex of CRC with members of the chromatin remodelling epigenetically represses WUS expression through histone deacetylation, to ensure the termination of floral stem cell activity [108]. Recent research has indicated that CRC is required for plant ovule differentiation and development [37,38]. In pomegranate, PgCRC are expressed in bisexual and functional male flowers [103]. PgCRC expression promotes seed and seed coat development, and PgCRC protein directly interacts with PgBEL1 [4]. These results reveal a role for PgCRC in ovule and seed development, as PgCRC participates in the BEL1-INO ovule regulatory pathway in the plant. Our findings confirmed that PgCRC protein interacts with PgBEL1 and they participate in the traditional INO-BEL1-MADS ovule development regulatory network in woody fruit trees [4].

4. MicroRNA Regulates Ovule Development in Pomegranate

The target genes of conserved microRNAs (miRNAs) are TF-coding (transcription factors, TF) involved in controlling developmental processes [110,111]. The regulation pairs of miRNA-target genes show significant negative correlations at transcriptional levels [111,112,113]. MiRNAs have been implicated in processes as diverse as flowering [114] and ovule development (Table 3) [115,116,117]. miR165 and miR166, which are highly expressed in the small regions of early ovule primordia, restrict the PHB expression domain to promote integument formation [118]. MiRNA-target genes have been identified in pomegranate [119]. PgmiR156, PgmiR157, PgmiR159, PgmiR160, PgmiR172, and PgmiR319 were highly expressed in leaves, functional male and bisexual flowers, and different fruit developmental stages of pomegranate [119,120]. MiR156 negatively regulated the expression of PgSPL5, PgSPL12 and PgSPL13 (SPOROCYTELESS5/12/13), which played roles in pomegranate flower development [121]. Combined analyses of small RNAs and mRNAs indicated that Pg-miR858b affect pomegranate pistil development, and Pg-miR444b.1, Pg-miRN11, Pg-miR166/165a-3p, and Pg-miR952b regulate pomegranate integument and embryo sac development [122]. Pg-miR166a-3p can interact with its targets (Gglean012177.1 (PHB orthologous gene) and Gglean013966.1 (PHAVOLUTA, PHV orthologous gene)), to affect ovule development [122]. Small RNA sequencing analysis also found that known miRNAs were differentially expressed during pomegranate flower development [8], such as miR167, miR164 and miR160, and that the target genes of these known miRNAs were predicted in pomegranate [119].

Table 3.

Conserved miRNAs, and their targets and functions in plant flower development.

4.1. MiR166—The Negative Regulator of Pomegranate Ovule Development

MiR166 targets the highly conserved class III homeodomain-leucine zipper (HD-ZIP III) family gene, which includes ATHB8, PHV, PHB, REVOLUTA (REV), and CORONA (CNA) in Arabidopsis thaliana [144,145]. Tight spatial regulation of PHB by miR165/166 is critical for proper ovule morphogenesis [118]. In phb-1d mutants that are insensitive to miR165/166 regulation, the outer integument development is disrupted, underscoring the necessity of miR165/166 activity in restricting PHB expression to specific domains within early ovule primordia to facilitate integument initiation [118,146].

In pomegranate, differential expression analysis between functional male flowers and bisexual flowers revealed 43 known and 14 novel miRNAs with significant expression changes, among which Pg-miR166a-3p was notably upregulated in functional male flowers [122]. This increase in Pg-miR166a-3p expression correlated with the downregulation of its predicted target genes, Gglean012177.1 and Gglean013966.1. Ectopic expression of Pg-miR166a-3p in transgenic lines led to a significant reduction in the number of ovule primordia, while simultaneously increasing the number of floral meristems [122]. These findings confirmed that Pg-miR166a-3p negatively regulates ovule development in pomegranate, likely through post-transcriptional repression of Gglean012177.1 and Gglean013966.1.

4.2. MiR167—The Putative Positive Regulator of Pomegranate Ovule Development

In Arabidopsis thaliana, miRNAs play a crucial role in modulating auxin signaling pathways, particularly through the post-transcriptional regulation of ARF genes [147]. Among these, miR167 specifically negatively targets ARF6 and ARF8. Transgenic Arabidopsis plants harboring miR167-resistant versions of ARF6 or ARF8 exhibit defects in ovule formation and anther dehiscence, highlighting the essential role of miR167 in reproductive organ development [148]. In this context, miR167a is the principal precursor gene responsible for establishing spatial restriction of ARF6 and ARF8 expression during floral organogenesis. Both ARF6 and ARF8 are necessary for female fertility in Arabidopsis, whereas jasmonic acid (JA) signaling, along with transcription factors MYB21 and MYB24, predominantly influences stamen and petal development [74,149,150]. Similarly, in tomato, ARF6 and ARF8 function in the coordinated development of the gynoecium, stamen, and petals [74]. Notably, in developing Arabidopsis flowers, ARF6 and ARF8 are expressed in stamen filaments, a major site of JA biosynthesis [73,151].

In the ‘Taishanhong’ pomegranate genome, 19 ARF genes have been identified, including three PgARF6 homologs [8]. Both PgmiR167a and PgmiR167d possess binding sites within the coding sequences of PgARF6 genes. Experimental evidence has confirmed a direct regulatory interaction between PgmiR167a and PgARF6a [8]. In bisexual flowers, a negative correlation was observed between PgmiR167d and PgARF6b expression levels, while in functional male flowers, PgmiR167d was inversely correlated with PgARF6a and PgARF6c expression (Supplementary Figure S3A).

Under treatment with exogenous indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) and 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA), the expression of PgARF6 genes was generally downregulated, with PgARF6c showing significant repression [8]. Moreover, transcriptomic analyses revealed negative correlations between PgARF6 expression and the levels of endogenous zeatin riboside (ZR), BR, gibberellins (GA), and abscisic acid (ABA). Conversely, JA content was positively correlated with PgARF6a and PgARF6c expression under IBA treatment [8]. Collectively, these findings indicate that PgmiR167 and PgARF6 genes are integral to the hormonal regulation of flower and ovule development in pomegranate.

4.3. MiR164—The Putative Positive Regulator of Pomegranate Ovule Development

Plant miR164 plays a multifaceted role in development by mediating the post-transcriptional regulation of transcription factors containing the NAC (NAM/ATAF/CUC) domain. In Arabidopsis thaliana, miR164a non-redundantly regulates leaf margin serration through repression of CUC2 transcripts [70]. Similarly, miR164c restricts supernumerary petal formation during early floral development by downregulating CUC1 and CUC2 in the second floral whorl [131]. Additionally, miR164a and miR164b facilitate auxin-mediated lateral-root emergence by targeting NAC1 for transcript cleavage [132]. In tomato, SlmiR164b is essential for the delineation of shoot and floral boundaries, while SlmiR164a contributes to fruit growth regulation [152]. In maize, five NAC family genes have been identified as putative targets of zma-miR164, with three of these expression patterns inversely correlated with zma-miR164 levels [113]. In Arabidopsis, CUC1 and CUC2 are also implicated in ovule development, in part through their activation of cytokinin biosynthetic pathways [153]. Disruption of miR164-mediated regulation of CUC1 and CUC2 significantly alters the number, positioning, and morphology of carpel margin meristems (CMMs), further emphasizing their importance in reproductive organogenesis [69].

PgNST is a homologous gene of NAC in the pomegranate, PgNST3 protein-binding PgMYB46 promoter, regulating the thickness of the inner seed coat; PgNST3A overexpression results in softer and smaller tomato seed coats [84]. In pomegranate, transcriptomic and small RNA sequencing analyses of bisexual and functional male flowers revealed that the expression levels of PgCUCa and PgCUCb, homologs of CUC genes, gradually declined in both flower types (Supplementary Figure S3B). In contrast, the expression of PgmiR164c-5p exhibited a dynamic pattern, increasing and subsequently decreasing in bisexual flowers, while showing the opposite trend in functional male flowers. These reciprocal expression patterns suggest a regulatory relationship between PgmiR164c-5p and PgCUC genes, consistent with a role for miR164 in promoting ovule development in pomegranate by fine-tuning the expression of CUC genes.

4.4. MiR160—The Predicted Positive Regulator of Pomegranate Ovule Development

Accumulating evidence indicates that miR160 plays a critical role in both vegetative and reproductive development by targeting members of the ARF gene family, particularly ARF10, ARF16 and ARF17 [128,129,154]. In tomato, suppression of sly-miR160 results in the upregulation of SlARF10a, SlARF10b and SlARF17, with SlARF10a exhibiting the most pronounced increase in expression [155,156]. Functional analyses further reveal that sly-miR160a promotes the development of leaves and floral organs through quantitative regulation of its primary target, SlARF10a. In Arabidopsis thaliana, ARF17 is essential for pollen wall formation, and loss-of-function mutants display male sterility, underscoring the role of miR160-targeted ARFs in reproductive organogenesis [157].

In pomegranate, expression profiling during bisexual flower development revealed a gradual decline in PgmiR160a-3p levels, coinciding with a progressive increase in PgARF10 transcript abundance (Supplementary Figure S3C). Similarly, during functional male flower development, the expression of PgARF10 and PgARF16a increased, whereas PgmiR160a-3p expression decreased. These inverse expression trends suggest that PgmiR160a-3p negatively regulates PgARF10 and, potentially, PgARF16a, and that this regulatory axis may be critical for floral and ovule development in pomegranate. Collectively, these findings support the hypothesis that miR160a-3p, through its interaction with ARF transcription factors, contributes to the regulation of ovule development, highlighting the broader role of miRNA-TF networks in coordinating reproductive development in pomegranate.

5. Implications for Fruit Production and Quality

Due to the effects of global climate change, the decreasing availability of arable land, and the continuous increase in global population, food security is becoming increasingly challenging [158,159,160]. Consequently, increasing crop yield remains a central objective in agricultural research and breeding programs [161]. Among the key determinants of yield is seed number, which is fundamentally dependent on the number of ovules initiated within the carpels by meristematic tissues [9]. As ovule number directly influences potential seed number, it serves as a primary factor shaping both reproductive success and fruit yield.

Ovules originate from meristematic tissue in the gynoecium, and, following successful fertilization, each ovule gives rise to a seed, while the gynoecium itself matures into the fruit [71,162]. As such, ovule number represents a key heritable trait with significant implications for crop improvement [163]. Ovule number per flower defines the theoretical maximum number of seeds that can be produced, while the final seed number is further constrained by the spatial and developmental limitations imposed by fruit structure, such as the size of the fruit [164]. Thus, coordinated regulation of ovule initiation and fruit development is critical for optimizing seed set and fruit quality.

Importantly, increases in ovule number must also be evaluated in the context of seed viability and quality. Therefore, elucidating the molecular mechanisms that govern ovule development is essential for advancing modern agricultural productivity. Ovule development is tightly regulated by complex gene regulatory networks involving transcription factors that control placenta patterning, ovule primordium initiation, and morphogenesis [12,13,165]. Given the positive correlation between ovule number and gynoecium size, several key genetic determinants of these traits have been identified [163,166]. A comprehensive understanding of these regulatory networks offers new avenues for enhancing crop yield through targeted genetic improvement. As seedlessness is a desirable trait that improves ease of consumption [167], developing new seedless varieties with large, high-quality fruits is a key objective in fruit breeding [79,168]. Seedlessness has been bred into many fruit species, including grape [168], litchi [169], citrus [170], watermelon [171], and pear [79]. Therefore, clarifying the development mechanism of the pomegranate ovule is the basis of exploring the characters of polyovule and functional male flowers in pomegranate.

6. Conclusions

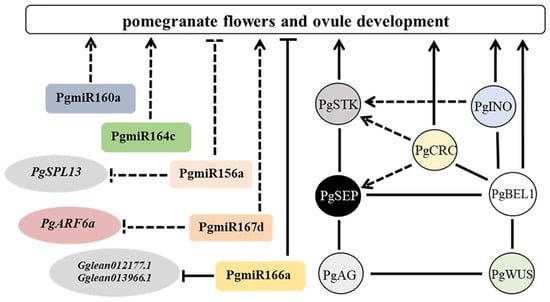

Diverse factors and genetic networks in ovule development indicate that different pathways act cooperatively to ensure the proper establishment and progression of seed through the regulation of hub factors. We propose a model for pomegranate ovule development that explains how the ovule is regulated by the INO, CRC, BEL1, and MADS-box homeodomain protein complex, and miRNAs (Figure 1). PgAGL11 promotes ovule development in transgenic Arabidopsis. PgCRC, PgINO and PgBEL1 regulate ovule development and seed determination. As a protein molecular bridge, the PgBEL1 protein combines with PgCRC, PgINO and PgSEP proteins, which are involved in regulating pomegranate ovule and seed development. The PgARF6s protein function in the cell nucleus and PgmiR167a directly targets PgARF6a and affects its expression. PgmiR166a could interact with its target genes (Gglean013966.1 and Gglean012177.1) to affect ovule development. In addition to these factors regulating ovule development, recent studies have revealed that plant hormones brassinosteroids and cytokinin, as well as the post-translational modifications of proteins (such as acetylation and S-sulfenylation modifications), are also involved in the regulation of ovule development in A. thaliana [44,165,172,173], which provides insights into exploring the mechanisms of pomegranate ovule development from multiple perspectives. This review lays the foundation for elucidating polyovule development and ovule sterility for functional male flowers in pomegranate.

Figure 1.

The regulation model of ovule development in pomegranate. The solid lines indicate the confirmed interaction relationships. The dashed lines represent regulatory relationships which are predicted or at the transcriptional level. Arrows indicate positive regulation or activation, and strings represent negative regulation or repression.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12010026/s1, Supplementary Figure S1: Expression patterns of ovule identify genes in PgBEL1 transgenic Arabidopsis lines. Several pre-bloom flowers were collected for each transgenic line. Stem, leaf, and young siliques were collected at the same time. Mature siliques were collected when the seed coat turned yellow. Data were means ± SD of three technical replicates. ∗ represents the level of significance difference p < 0.05, ∗∗ represents the level of significance difference p < 0.01 in independent-samples t-test. Supplementary Figure S2: Relative expression of PgAG (A), PgSTK (B), PgSEP1 (C) and PgSEP4 (D) in pomegranate flowers at different development stages. Buds are divided into eight developmental stages, according to Zhao Y.J. (2023) [90]. Data are means ± SD of three technical replicates. Supplementary Figure S3: (A) Relative expression of PgmiR167d and target genes PgARF6s in bisexual and functional male flowers, respectively. (B): Relative expression of PgmiR164c-5p and target genes PgCUCs in bisexual and functional male flowers, respectively. (C): Relative expression of PgmiR160a-3p and target genes PgARF10, PgARF16s, and PgARF17 in bisexual and functional male flowers, respectively. Supplementary Data.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., H.S. and J.J.; validation and formal analysis, M.L., Y.M., X.Z. (Xiaoyan Zhu), K.Z., P.H., R.W., L.C., Y.S., Y.L., M.W., J.S., S.S. and T.B.; funding acquisition, Z.Y., J.J. and X.Z. (Xianbo Zheng); the corresponding authors supervised the entire experimental process. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the China Scholarship Council (CSC, 202008320482), the Initiative Project for Talents of Nanjing Forestry University (GXL2014070), the fund for modern agricultural industrial technology systems of Henan province (HARS-22-09-G3), Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project (242102110284), and the Basic Research Program of Key Scientific Research Projects of Henan Province Universities (25B210005).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Pomegranate flower transcriptome data (PRJNA754480) and microRNA sequencing data (PRJNA793612) can be downloaded from the NCBI database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wetzstein, H.Y.; Ravid, N.; Wilkins, E.; Martinelli, A.P. A morphological and histological characterization of bisexual and male flower types in pomegranate. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2011, 136, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engin, H.; Gokbayrak, Z. Micromorphology of pollen grains from bisexual and functional male flowers of pomegranate. AGROFOR Int. J. 2017, 2, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.N.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.X.; Niu, J.; Xue, H.; Liu, B.B.; Wang, Q.; Luo, X.; Zhang, F.H.; Zhao, D.G.; et al. Transcriptomic analysis reveals candidate genes for female sterility in pomegranate flowers. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Wang, Y.Y.; Yan, M.; Liu, C.Y.; Yuan, Z.H. BELL1 interacts with CRABS CLAW and INNER NO OUTER to regulate ovule and seed development in pomegranate. Plant Physiol. 2023, 191, 1066–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzstein, H.Y.; Yi, W.G.; Porter, J.A.; Ravid, N. Flower position and size impact ovule number per flower, fruitset, and fruit size in pomegranate. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2013, 138, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Li, H.X.; Wu, Z.K.; Yao, W.; Zhao, P.; Cao, D.; Yu, H.Y.; Li, K.D.; Poudel, K.; Zhao, D.G.; et al. The pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) draft genome dissects genetic divergence between soft- and hard-seeded cultivars. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.H.; Fang, Y.M.; Zhang, T.K.; Fei, Z.J.; Han, F.M.; Liu, C.Y.; Liu, M.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, W.J.; Wu, S.; et al. The pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) genome provides insights into fruit quality and ovule developmental biology. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 16, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhao, X.Q.; Yan, M.; Ren, Y.; Yuan, Z.H. ARF6s identification and function analysis provide insights into flower development of Punica granatum L. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 833747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overholt, A.M.; Pierce, C.E.; Paleologos, C.S.; Shpak, E.D. ERECTA family signaling controls cell fate specification during ovule initiation in Arabidopsis. bioRxiv, 2024; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, D.R.; Bowman, J.L.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Early flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1990, 2, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.X.; Zhou, L.W.; Hu, L.Q.; Jiang, Y.T.; Zhang, Y.J.; Feng, S.L.; Jiao, Y.L.; Xu, L.; Lin, W.H. Asynchrony of ovule primordia initiation in Arabidopsis. Development 2020, 147, 196618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Olalde, J.I.; Zuñiga-Mayo, V.M.; Montes, R.A.C.; Marsch-Martinez, N.; de Folter, S. Inside the gynoecium: At the carpel margin. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barro-Trastoy, D.; Carrera, E.; Baños, J.; Palau-Rodriguez, J.; Ruiz-Rivero, O.; Tornero, P.; Alonso, J.M.; López-Díaz, I.; Gómez, M.D.; Pérez-Amador, M.A. Regulation of ovule initiation by gibberellins and brassinosteroids in tomato and Arabidopsis: Two plant species, two molecular mechanisms. Plant J. 2020, 102, 1026–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, J.L.; Drews, G.N.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Expression of the Arabidopsis floral homeotic gene AGAMOUS is restricted to specific cell types late in flower development. Plant Cell 1991, 3, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, A.H.; Yanofsky, M.F. Fruit development in Arabidopsis. Arab. Book 2006, 4, e0075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneitz, K.; Baker, S.C.; Gasser, C.S.; Redweik, A. Pattern formation and growth during floral organogenesis: HUELLENLOS and AINTEGUMENTA are required for the formation of the proximal region of the ovule primordium in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 1998, 125, 2555–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, R.; Colombo, M.; Kater, M.M. The ins and outs of ovule development. Fruit Development and Seed Dispersal. Annu. Plant Rev. 2009, 38, 70–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, M.; Colombo, L.; Roig-Villanova, I. Ovule development, a new model for lateral organ formation. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Folter, S.; Shchennikova, A.V.; Franken, J.; Busscher, M.; Baskar, R.; Grossniklaus, U.; Angenent, G.C.; Immink, R.G.H. A Bsister MADS-box gene involved in ovule and seed development in petunia and Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2006, 47, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Barg, R.; Arazi, T. Tomato agamous-like6 parthenocarpy is facilitated by ovule integument reprogramming involving the growth regulator KLUH. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinyopich, A.; Ditta, G.S.; Savidge, B.; Liljegren, S.J.; Baumann, E.; Wisman, E.; Yanofsky, M.F. Assessing the redundancy of MADS-box genes during carpel and ovule development. Nature 2003, 424, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreni, L.; Jacchia, S.; Fornara, F.; Fornari, M.; Ouwerkerk, P.B.F.; An, G.; Colombo, L.; Kater, M.M. The D-lineage MADS-box gene OsMADS13 controls ovule identity in rice. Plant J. 2007, 52, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, N.; Carpio, D.P.D.; Hofmann, A.; Mizuta, Y.; Kurihara, D.; Higashiyama, T.; Uchida, N.; Torii, K.U.; Colombo, L.; Groth, G.; et al. A peptide pair coordinates regular ovule initiation patterns with seed number and fruit size. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 4352–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.Q.; Li, P.X.; Zhu, D.Y.; Ma, H.C.; Li, M.; Lai, Y.X.; Peng, Y.X.; Li, H.X.; Li, S.; Wei, J.B.; et al. SlCRCa is a key D-class gene controlling ovule fate determination in tomato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 1966–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losa, A.; Colombo, M.; Brambilla, V.; Colombo, L. Genetic interaction between AINTEGUMENTA (ANT) and the ovule identity genes SEEDSTICK (STK), SHATTERPROOF1 (SHP1) and SHATTERPROOF2 (SHP2). Sex. Plant Reprod. 2010, 23, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Apice, G.; Moschin, S.; Nigris, S.; Ciarle, R.; Muto, A.; Bruno, L.; Baldan, B. Identification of key regulatory genes involved in the sporophyte and gametophyte development in Ginkgo biloba ovules revealed by in situ expression analyses. Am. J. Bot. 2022, 109, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, B.; Hasson, A.; Belcram, K.; Cortizo, M.; Morin, H.; Nikovics, K.; Vialette-Guiraud, A.; Takeda, S.; Aida, M.; Laufs, P.; et al. A conserved role for CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON genes during ovule development. Plant J. 2015, 83, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Tang, D.; Cheng, X.J.; Zhang, J.X.; Tang, Y.J.; Tao, Q.D.; Shi, W.Q.; You, A.Q.; Gu, M.H.; Cheng, Z.K.; et al. OsPINOID regulates stigma and ovule initiation through maintenance of the floral meristem by auxin signaling. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 952–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaro, R.; Pinyopich, A.; Battaglia, R.; Kooiker, M.; Borghi, L.; Ditta, G.; Yanofsky, M.F.; Kater, M.M.; Colombo, L. MADS-box protein complexes control carpel and ovule development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 2603–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angenent, G.C.; Franken, J.; Busscher, M.; Van Dijken, A.; Van Went, J.L.; Dons, H.J.; Van Tunen, A.J. A novel class of MADS-box genes is involved in ovule development in petunia. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 1569–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, L.; Franken, J.; Van der Krol, A.R.; Wittichy, P.E.; Donsy, H.J.M.; Angenenta, G.C. Downregulation of ovule-specific MADS-box genes from petunia results in maternally controlled defects in seed development. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.L.; Zhong, H.X.; Zhang, F.C.; Zheng, J.L.; Zhang, C.; Vivek, Y.; Zhou, X.M.; Nocker, S.V.; Wu, X.Y.; Wang, X.P. Identification of grapevine BASIC PENTACYSTEINE transcription factors and functional characterization of VvBPC1 in ovule development. Plant Sci. 2025, 356, 112491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, V.; Battaglia, R.; Colombo, M.; Masiero, S.; Bencivenga, S.; Kater, M.M.; Colombo, L. Genetic and molecular interactions between BELL1 and MADS-box factors support ovule development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2544–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross-Hardt, R.; Lenhard, M.; Laux, T. WUSCHEL signaling functions in interregional communication during Arabidopsis ovule development. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, P.; Gheyselinck, J.; Gross-Hardt, R.; Laux, T.; Grossniklaus, U.; Schneitz, K. Pattern formation during early ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Dev. Biol. 2004, 273, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, D.R.; Skinner, D.J.; Gasser, C.S. Roles of polarity determinants in ovule development. Plant J. 2009, 57, 1054–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Hsiao, Y.Y.; Li, C.I.; Yeh, C.M.; Mitsuda, N.; Yang, H.X.; Chiu, C.C.; Chang, S.B.; Liu, Z.J.; Tsai, W.C. The ancestral duplicated DL/CRC orthologs, PeDL1 and PeDL2, function in orchid reproductive organ innovation. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 5442–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, P.C.; Song, C.J.; Liu, H.Y.; Li, P.G.; Zhang, M.S.; Zhang, J.S.; Zhang, S.H.; He, C.Y. Physalis floridana CRABS CLAW mediates neofunctionalization of GLOBOSA genes in carpel development. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 6882–6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.Q.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.T.; Jiang, Y.D.; Yu, H.; Cao, X.F.; Qin, G.J. Arabidopsis TCP4 transcription factor inhibits high temperature-induced homeotic conversion of ovules. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, T.L.; Haughn, G.W. BELL1 and AGAMOUS genes promote ovule identity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1999, 18, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.W.; Klocko, A.L.; Brunner, A.M.; Ma, C.; Magnuson, A.C.; Howe, G.T.; An, X.M.; Strauss, S.H. RNA interference suppression of AGAMOUS and SEEDSTICK alters floral organ identity and impairs floral organ determinacy, ovule differentiation, and seed-hair development in Populus. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 923–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osnato, M.; Lacchini, E.; Pilatone, A.; Dreni, L.; Grioni, A.; Chiara, M.; Horner, D.; Pelaz, S.; Kater, M.M. Transcriptome analysis reveals rice MADS13 as an important repressor of the carpel development pathway in ovules. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 398–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, L.; Franken, J.; Koetje, E.; Van Went, J.; Dons, H.J.; Angenent, G.C.; Van Tunen, A.J. The petunia MADS-box gene FBP11 determines ovule identity. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 1859–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.X.; Shang, E.L.; Hawar, A.; Ito, T.; Sun, B. Brassinosteroid signaling represses ZINC FINGER PROTEIN11 to regulate ovule development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 5004–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- di Rienzo, V.; Imanifard, Z.; Mascio, I.; Gasser, C.S.; Skinner, D.J.; Pierri, C.L.; Marini, M.; Fanelli, V.; Sabetta, W.; Montemurro, C.; et al. Functional conservation of the grapevine candidate gene INNER NO OUTER for ovule development and seed formation. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, D.J.; Brown, R.H.; Kuzoff, R.K.; Gasser, C.S. Conservation of the role of INNER NO OUTER in development of unitegmic ovules of the Solanaceae despite a divergence in protein function. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lora, J.; Hormaza, J.I.; Herrero, M. Transition from two to one integument in Prunus species: Expression pattern of INNER NO OUTER (INO), ABERRANT TESTA SHAPE (ATS) and ETTIN (ETT). New Phytol. 2015, 208, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Xu, Y.F.; Wee, W.Y.; Ichihashi, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Shibata, A.; Shirasu, K.; Ito, T. Regulation of floral meristem activity through the interaction of AGAMOUS, SUPERMAN, and CLAVATA3 in Arabidopsis. Plant Reprod. 2018, 31, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Franks, R.G.; Klink, V.P. Regulation of gynoecium marginal tissue formation by LEUNIG and AINTEGUMENTA. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 1879–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.K.; Skinner, D.J.; Gallagher, T.L.; Gasser, C.S. Integument development in Arabidopsis depends on interaction of YABBY protein INNER NO OUTER with coactivators and corepressors. Genetics 2017, 207, 1489–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, H.; Kalve, S.; Wolabu, T.W.; Nakashima, J.; Golz, J.F.; Tadege, M. Control of leaf blade outgrowth and floral organ development by LEUNIG, ANGUSTIFOLIA3 and WOX transcriptional regulators. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 2024–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, A.N.; Seaman, A.A.; Jones, A.L.; Franks, R.G. Novel functional roles for PERIANTHIA and SEUSS during floral organ identity specification, floral meristem termination, and gynoecial development. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azhakanandam, S.; Nole-Wilson, S.; Bao, F.; Franks, R.G. SEUSS and AINTEGUMENTA mediate patterning and ovule initiation during gynoecium medial domain development. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.; Ito, T.; Wellmer, F.; Vernoux, T.; Dedieu, A.; Traas, J.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Floral stem cell termination involves the direct regulation of AGAMOUS by PERIANTHIA. Development 2009, 136, 1605–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.T.; Stehling-Sun, S.; Wollmann, H.; Demar, M.; Hong, R.L.; Haubeiß, S.; Weigel, D.; Lohmann, J.U. Dual roles of the bZIP transcription factor PERIANTHIA in the control of floral architecture and homeotic gene expression. Development 2009, 136, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, D.J.; Baker, S.C.; Meister, R.J.; Broadhvest, J.; Schneitz, K.; Gasser, C.S. The Arabidopsis HUELLENLOS gene, which is essential for normal ovule development, encodes a mitochondrial ribosomal protein. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 2719–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Jiang, W.B.; Hu, Y.W.; Wu, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Liang, W.Q.; Wang, Z.Y.; Lin, W.H. BR signal influences Arabidopsis ovule and seed number through regulating related genes expression by BZR1. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadhvest, J.; Baker, S.C.; Gasser, C.S. SHORT INTEGUMENTS 2 promotes growth during Arabidopsis reproductive development. Genetics 2000, 155, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.A.; Broadhvest, J.; Kuzoff, R.K.; Gasser, C.S. Arabidopsis SHORT INTEGUMENTS 2 is a mitochondrial DAR GTPase. Genetics 2006, 174, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugouvieux, V.; Blanc-Mathieu, R.; Janeau, A.; Paul, M.; Lucas, J.; Xu, X.C.; Ye, H.L.; Lai, X.L.; Hir, S.L.; Guillotin, A.; et al. SEPALLATA-driven MADS transcription factor tetramerization is required for inner whorl floral organ development. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 3435–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Hu, X.W.; Wei, H.; Cheng, Y.Q.; Liu, J.F. Identification of ChSEP genes in the whole genome of hazelnut, preparation of polyclonal antibody and expression in ovules. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2023, 45, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoong, L.; Ireland, H.S.; Tomes, S.; Gunaseelan, K.; Ruslan, M.; McKenzie, C.; Hallett, I.; David, K.M.; Schaffer, R.J. Overexpression of the apple SEP1/2-like gene MdMADS8 promotes floral determinacy and enhances fruit flesh tissue and ripening. Planta 2025, 261, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.H.; Wu, J.; Hong, L.; Liang, J.J.; Ren, Y.M.; Guan, P.Y.; Hu, J.F. MADS-box protein complex VvAG2, VvSEP3 and VvAGL11 regulates the formation of ovules in Vitis vinifera L. cv. ‘Xiangfei’. Genes 2021, 12, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditta, G.; Pinyopich, A.; Robles, P.; Pelaz, S.; Yanofsky, M.F. The SEP4 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana functions in floral organ and meristem identity. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 1935–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, K.; Bhide, A.S.; Tekleyohans, D.G.; Wittkop, B.; Snowdon, R.J.; Becker, A. The MADS Box Genes ABS, SHP1, and SHP2 are essential for the coordination of cell divisions in ovule and seed coat development and for endosperm formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Baum, S.F.; Alvarez, J.; Patel, A.; Chitwood, D.H.; Bowman, J.L. Activation of CRABS CLAW in the nectaries and carpels of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Q.; Tan, F.Q.; Chung, C.H.; Slavkovic, F.; Devani, R.S.; Troadec, C.; Marcel, F.; Morin, H.; Camps, C.; Roldan, M.V.G.; et al. The control of carpel determinacy pathway leads to sex determination in cucurbits. Science 2022, 378, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieber, P.; Petrascheck, M.; Barberis, A.; Schneitz, K. Organ polarity in Arabidopsis. NOZZLE Physically Interacts with Members of the YABBY Family. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 2172–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiuchi, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Furutani, M.; Tasaka, M.; Aida, M. The CUC1 and CUC2 genes promote carpel margin meristem formation during Arabidopsis gynoecium development. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikovics, K.; Blein, T.; Peaucelle, A.; Ishida, T.; Morin, H.; Aida, M.; Laufs, P. The balance between the MIR164a and CUC2 genes controls leaf margin serration in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 2929–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, M.; Manrique, S.; Cuesta, C.; Benkova, E.; Novak, O.; Colombo, L. CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON1 (CUC1) and CUC2 regulate cytokinin homeostasis to determine ovule number in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 5169–5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Wang, W.; Qin, W.Q.; Men, S.Z.; Li, H.L.; Mitsuda, N.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Wu, A.M. Transcription factors KNAT3 and KNAT4 are essential for integument and ovule formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2023, 191, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.F.; Tian, Q.; Reed, J.W. Arabidopsis microRNA167 controls patterns of ARF6 and ARF8 expression, and regulates both female and male reproduction. Development 2006, 133, 4211–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Wu, S.; Van Houten, J.; Wang, Y.; Ding, B.; Fei, Z.J.; Clarke, T.H.; Reed, J.W.; van der Knaap, E. Down-regulation of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORS 6 and 8 by microRNA 167 leads to floral development defects and female sterility in tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 2507–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, M.; Hooper, L.C.; Johnson, S.D.; Rodrigues, J.C.M.; Vivian-Smith, A.; Koltunow, A.M. Expression of aberrant forms of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 stimulates parthenocarpy in Arabidopsis and Tomato. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.Q.; Chang, J.H.; Yu, S.X.; Jiang, Y.T.; Li, R.H.; Zheng, J.X.; Zhang, Y.J.; Xue, H.W.; Lin, W.H. PIN3 positively regulates the late initiation of ovule primordia in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrella, R.; Gabrieli, F.; Cavalleri, A.; Schneitz, K.; Colombo, L.; Cucinotta, M. Pivotal role of STIP in ovule pattern formation and female germline development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 2022, 149, dev201184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, M.D.; Ventimilla, D.; Sacristan, R.; Perez-Amador, M.A. Gibberellins regulate ovule integument development by interfering with the Transcription Factor ATS. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 2403–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.B.; Zhang, H.Q.; Liang, F.F.; Cong, L.; Song, L.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Zhai, R.; Yang, C.Q.; Wang, Z.G.; Ma, F.W.; et al. PbEIL1 acts upstream of PbCysp1 to regulate ovule senescence in seedless pear. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.C.; Lin, J.Y.; Hsu, W.H.; Kung, C.T.; Dai, S.Y.; Yang, J.Y.; Tan, C.M.; Yang, C.H. OAF is a DAF-like gene that controls ovule development in plants. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Q.; Li, P.X.; Li, M.; Zhu, D.Y.; Ma, H.C.; Xu, H.M.; Li, S.; Wei, J.B.; Bian, X.X.; Wang, M.Y.; et al. Heat stress impairs floral meristem termination and fruit development by affecting the BR-SlCRCa cascade in tomato. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Deka, M.; Sebastian, D.; Rosanna, P.; Veronica, G.; Li, J.R.; Wu, L.; Sonia, G. Spatiotemporal restriction of FUSCA3 expression by Class I BPCs promotes ovule development and coordinates embryo and endosperm growth. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 1886–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.N.; Zhang, J.; Niu, J.; Li, H.X.; Xue, H.; Liu, B.B.; Xia, X.C.; Zhang, F.H.; Zhao, D.G.; Cao, S.Y. Cloning and functional verification of gene PgAGL11 associated with the development of flower organs in pomegranate plant. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2017, 44, 2089–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.N.; Wang, H.; Xu, T.T.; Liu, R.T.; Zhu, J.L.; Li, H.X.; Zhang, H.W.; Tang, L.Y.; Jing, D.; Yang, X.W.; et al. A telomere-to-telomere gap-free assembly integrating multi-omics uncovers the genetic mechanism of fruit quality and important agronomic trait associations in pomegranate. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 2852–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Schneitz, K. NOZZLE links proximal distal and adaxial abaxial pattern formation during ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 2002, 129, 4291–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrusan, Z.; Reiser, L.; Feldmann, K.A.; Fischer, R.L.; Haughn, G.W. Homeotic transformation of ovules into carpel-like structures in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Robinson-Beers, K.; Ray, S.; Baker, S.C.; Lang, J.D.; Preuss, D.; Milligan, S.B.; Gasser, C.S. Arabidopsis floral homeotic gene BELL1 (BEL1) controls ovule development through negative regulation of AGAMOUS gene (AG). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 5761–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Zhao, Y.J.; Yan, M.; Zhao, H.L.; Zhang, X.H.; Yuan, Z.H. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of TALE gene family in pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). Agronomy 2020, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Liu, C.Y.; Zhao, X.Q.; Wang, Y.Y.; Yan, M.; Yuan, Z.H. Cloning and spatiotemporal expression analysis of PgWUS and PgBEL1 in Punica granatum. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2021, 48, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.J. Study on the Mechanism of Pomegranate Ovule Development and the Function of Key Transcription Factors. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Zhao, H.L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.H.; Zhao, X.Q.; Yuan, Z.H. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of MIKC-Type MADS-box gene family in Punica granatum L. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbussche, M.; Zethof, J.; Souer, E.; Koes, R.; Tornielli, G.B.; Pezzotti, M.; Ferrario, S.; Angenent, G.C.; Gerats, T. Toward the analysis of the petunia MADS box gene family by reverse and forward transposon insertion mutagenesis approaches: B, C, and D floral organ identity functions require SEPALLATA-like MADS-box genes in petunia. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 2680–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immink, R.G.H.; Tonaco, I.A.N.; de Folter, S.; Shchennikova, A.; van Dijk, A.D.J.; Busscher-Lange, J.; Borst, J.W.; Angenent, G.C. SEPALLATA3: The ‘glue’ for MADS-box transcription factor complex formation. Genome Biol. 2009, 10, R24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoof, H.; Lenhard, M.; Haecker, A.; Mayer, K.F.X.; Jürgens, G.; Laux, T. The stem cell population of Arabidopsis shoot meristems is maintained by a regulatory loop between the CLAVATA and WUSCHEL genes. Cell 2000, 100, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, S.; Kramer, E.M. The evolution of reproductive structures in seed plants: A re-examination based on insights from developmental genetics. New Phytol. 2012, 194, 910–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhard, M.; Bohnert, A.; Jürgens, G.; Laux, T. Termination of stem cell maintenance in Arabidopsis floral meristems by interactions between WUSCHEL and AGAMOUS. Cell 2001, 105, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.G.; Kim, Y.J.; Müller, R.; Yumul, R.E.; Liu, C.Y.; Pan, Y.Y.; Cao, X.F.; Goodrich, J.; Chen, X.M. AGAMOUS terminates floral stem cell maintenance in Arabidopsis by directly repressing WUSCHEL through recruitment of Polycomb Group Proteins. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3654–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S.C.; Robinson-Beers, K.; Villanueva, J.M.; Gaiser, J.C.; Gasser, C.S. Interactions among genes regulating ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 1997, 145, 1109–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, J.M.; Broadhvest, J.; Hauser, B.A.; Meister, R.J.; Schneitz, K.; Gasser, C.S. INNER NO OUTER regulates abaxial-adaxial patterning in Arabidopsis ovules. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 3160–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, R.J.; Kotow, L.M.; Gasser, C.S. SUPERMAN attenuates positive INNER NO OUTER autoregulation to maintain polar development of Arabidopsis ovule outer integument. Development 2002, 129, 4281–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, T.L.; Gasser, C.S. Independence and interaction of regions of the INNER NO OUTER protein in growth control during ovule development. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.D.; Chen, L.G.; Yin, G.M.; Yang, X.R.; Gao, Z.H.; Guo, Y.; Sun, Y.; Tang, W.Q. Brassinosteroids regulate outer ovule integument growth in part via the control of INNER NO OUTER by BRASSINOZOLE-RESISTANT family transcription factors. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 1093–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Liu, C.Y.; Ge, D.P.; Yan, M.; Ren, Y.; Huang, X.B.; Yuan, Z.H. Genome-wide identification and expression of YABBY genes family during flower development in Punica granatum L. Gene 2020, 752, 144784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, T.; Broholm, S.; Becker, A. CRABS CLAW acts as a bifunctional transcription factor in flower development. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, J.; Smyth, D.R. CRABS CLAW and SPATULA, two Arabidopsis genes that control carpel development in parallel with AGAMOUS. Development 1999, 126, 2377–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, J.L.; Smyth, D.R. CRABS CLAW, a gene that regulates carpel and nectary development in Arabidopsis, encodes a novel protein with zinc finger and helix-loop-helix domains. Development 1999, 126, 2387–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.; Smyth, D.R. CRABS CLAW and SPATULA genes regulate growth and pattern formation during gynoecium development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2002, 163, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, L.; Giménez, E.; Pineda, B.; García-Sogo, B.; Ortiz-Atienza, A.; Micol-Ponce, R.; Angosto, T.; Capel, J.; Moreno, V.; Yuste-Lisbona, F.J.; et al. Tomato CRABS CLAW paralogues interact with chromatin remodelling factors to mediate carpel development and floral determinacy. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablowski, R. Control of patterning, growth, and differentiation by floral organ identity genes. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axtell, M.J. Evolution of microRNAs and their targets: Are all microRNAs biologically relevant? Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Regul. Mech. 2008, 1779, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Cao, D.; Zhang, J.F.; Chen, L.; Xia, X.C.; Li, H.X.; Zhao, D.G.; Zhang, F.H.; Xue, H.; Chen, L.N.; et al. Integrated microRNA and mRNA expression profiling reveals a complex network regulating pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) seed hardness. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, Biogenesis, Mechanism, and Function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; An, X.L.; Zhu, T.T.; Yan, T.W.; Wu, S.W.; Tian, Y.H.; Li, J.P.; Wan, X.Y. Discovering and constructing ceRNA-miRNA-target gene regulatory networks during anther development in Maize. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, V.; Dean, C.; Simpson, G.G. Regulated RNA processing in the control of Arabidopsis flowering. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2005, 49, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdurakhmonov, I.Y.; Devor, E.J.; Buriev, Z.T.; Huang, L.Y.; Makamov, A.; Shermatov, S.E.; Bozorov, T.; Kushanov, F.N.; Mavlonov, G.T.; Abdukarimov, A. Small RNA regulation of ovule development in the cotton plant, G. hirsutum L. BMC Plant Biol. 2008, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.M.; Xue, W.; Dong, C.J.; Jin, L.G.; Bian, S.M.; Wang, C.; Wu, X.Y.; Liu, J.Y. A comparative miRNAome analysis reveals seven fiber initiation-related and 36 novel miRNAs in developing cotton ovules. Mol. Plant 2012, 4, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrella, R.; Cucinotta, M.; Mendes, M.A.; Underwood, C.J.; Colombo, L. The emerging role of small RNAs in ovule development, a kind of magic. Plant Reprod. 2021, 34, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, K.; Miyashima, S.; Sato-Nara, K.; Yamada, T.; Nakajima, K. Functionally diversified members of the MIR165/6 gene family regulate ovule morphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Huang, J.Y.; Li, M.; Ren, H.F.; Jiao, J.; Wan, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.M.; Shi, J.L.; Zhang, K.X.; et al. Exploring microRNAs associated with pomegranate pistil development: An identification and analysis study. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saminathan, T.; Bodunrin, A.; Singh, N.V.; Devarajan, R.; Nimmakayala, P.; Jeff, M.; Aradhya, M.; Reddy, U.K. Genome-wide identification of microRNAs in pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) by high-throughput sequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.B.; Zhao, Y.J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.H.; Wang, Y.W.; Shen, Y.; Yuan, Z.H. Genome-wide identification, gene cloning, subcellular location and expression analysis of SPL gene family in P. granatum L. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.N.; Luo, X.; Yang, X.W.; Jing, D.; Xia, X.C.; Li, H.X.; Poudel, K.; Cao, S.Y. Small RNA and mRNA sequencing reveal the roles of microRNAs involved in pomegranate female sterility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, R.; Palatnik, J.F.; Rieater, M.; Schommer, C.; Schmid, M.; Weigel, D. Specific effects of microRNAs on the plant transcriptome. Dev. Cell 2005, 8, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nodine, M.D.; Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs prevent precocious gene expression and enable pattern formation during plant embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 2678–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palatnik, J.F.; Allen, E.; Wu, X.; Schommer, C.; Schwab, R.; Carrington, J.C.; Weigel, D. Control of leaf morphogenesis by microRNAs. Nature 2003, 425, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achard, P.; Herr, A.; Baulcombe, D.C.; Harberd, N.P. Modulation of floral development by a gibberellin-regulated microRNA. Development 2004, 131, 3357–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.F.; Luo, Q.Z.; Zhang, X.Z.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Y.Q. Identification of vital candidate microRNA/mRNA pairs regulating ovule development using high-throughput sequencing in hazel. BMC Dev. Biol. 2020, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, A.C.; Bartel, D.P.; Bartel, B. MicroRNA-directed regulation of Arabidopsis AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR17 is essential for proper development and modulates expression of early auxin response genes. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1360–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Wang, L.J.; Mao, Y.B.; Cai, W.J.; Xue, H.W.; Chen, X.Y. Control of root cap formation by microRNA-targeted auxin response factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 2204–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufs, P. MicroRNA regulation of the CUC genes is required for boundary size control in Arabidopsis meristems. Development 2004, 131, 4311–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, C.C.; Sieber, P.; Wellmer, F.; Meyerowitz, E.M. The early extra petals1 mutant uncovers a role for microRNA miR164c in regulating petal number in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.S.; Xie, Q.; Fei, J.F.; Chua, N.H. MicroRNA directs mRNA cleavage of the transcription factor NAC1 to downregulate auxin signals for Arabidopsis lateral root development. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1376–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Grigg, S.P.; Xie, M.; Christensen, S.; Fletcher, J.C. Regulation of Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem and lateral organ formation by microRNA miR166g and its AtHD-ZIP target genes. Development 2005, 132, 3657–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.K.; Kubo, M.; Zhong, R.; Demura, T.; Ye, Z.H. Overexpression of miR165 affects apical meristem formation, organ polarity establishment and vascular development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007, 48, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsbecker, A.; Lee, J.Y.; Roberts, C.J.; Dettmer, J.; Lehesranta, S.; Zhou, J.; Lindgren, O.; Moreno-Risueno, M.A.; Vaten, A.; Thitamadee, S.; et al. Cell signalling by microRNA165/6 directs gene dose-dependent root cell fate. Nature 2010, 465, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, C.; Ravi, S.D.; Rachid, B.; Hao, Y.W.; Halima, M.; Fabien, M.; Marion, V.; Brahim, M.; Gwilherm, B.; Sylvie, C.; et al. The miR166-SlHB15A regulatory module controls ovule development and parthenocarpic fruit set under adverse temperatures in tomato. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.Z.; Chen, J.L.; Zhou, J.; Yu, H.; Ge, C.N.; Zhang, M.; Gao, X.H.; Dai, X.H.; Yang, Z.N.; Zhao, Y.D. An essential role for miRNA167 in maternal control of embryonic and seed development. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combier, J.P.; Frugier, F.; De Billy, F.; Boualem, A.; El-Yahyaoui, F.; Moreau, S.; Vernie, T.; Ott, T.; Gamas, P.; Crespi, M.; et al. MtHAP2-1 is a key transcriptional regulator of symbiotic nodule development regulated by microRNA169 in Medicago truncatula. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 3084–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. A microRNA as a translational repressor of APETALA2 in Arabidopsis flower development. Science 2004, 303, 2022–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauter, N.; Kampani, A.; Carlson, S.; Goebel, M.; Moose, S.P. MicroRNA172 down-regulates glossy15 to promote vegetative phase change in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9412–9417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollmann, H.; Mica, E.; Todesco, M.; Long, J.A.; Weigel, D. On reconciling the interactions between APETALA2, miR172 and AGAMOUS with the ABC model of flower development. Development 2010, 137, 3633–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, T.; Furutani, M.; Tasaka, M.; Ohme-Takagi, M. TCP transcription factors control the morphology of shoot lateral organs via negative regulation of the expression of boundary-specific genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schommer, C.; Palatnik, J.F.; Aggarwal, P.; Chetelat, A.; Cubas, P.; Farmer, E.E.; Nath, U.; Weigel, D. Control of jasmonate biosynthesis and senescence by miR319 targets. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.H.; Zhang, B.B.; Ma, R.J.; Yu, M.L.; Guo, S.L.; Guo, L. Isolation and expression analysis of four HD-ZIP III family genes targeted by microRNA166 in peach. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 14151–14161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigge, M.J.; Otsuga, D.; Alonso, J.M.; Ecker, J.R.; Drews, G.N.; Clark, S.E. Class III homeodomain-leucine zipper gene family members have overlapping, antagonistic and distinct roles in Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.F.; Ning, K.; Che, G.; Yan, S.S.; Han, L.J.; Gu, R.; Li, Z.; Weng, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.L. CsSPL functions as an adaptor between HD-ZIP III and CsWUS transcription factors regulating anther and ovule development in cucumber. Plant J. 2018, 94, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Small RNAs and their roles in plant development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009, 25, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.J.; Nagpal, P.; Villarino, G.; Trinidad, B.; Bird, L.; Huang, Y.B.; Reed, J.W. MiR167 limits anther growth to potentiate anther dehiscence. Development 2019, 146, 174375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, R.; Dobritzsch, S.; Gruber, C.; Hause, G.; Athmer, B.; Schreiber, T.; Marillonnet, S.; Okabe, Y.; Ezura, H.; Acosta, I.F.; et al. Tomato MYB21 acts in ovules to mediate Jasmonate-regulated fertility. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1043–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhao, Y.; McCaig, B.C.; Wingerd, B.A.; Wang, J.H.; Whalon, M.E.; Pichersky, E.; Howe, G.A. The tomato homolog of CORONATINE-INSENSITIVE1 is required for the maternal control of seed maturation, jasmonate-signaled defense responses, and glandular trichome development. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, S.; Kawai-Oda, A.; Ueda, J.; Nishida, I.; Okada, K. The DEFECTIVE IN ANTHER DEHISCIENCE gene encodes a novel phospholipase A1 catalyzing the initial step of jasmonic acid biosynthesis, which synchronizes pollen maturation, anther dehiscence, and flower opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 2191–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Vishwakarma, A.; Kenea, H.D.; Galsurker, O.; Cohen, H.; Aharoni, A.; Arazi, T. CRISPR/Cas9 mutants of tomato MICRORNA164 genes uncover their functional specialization in development. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 1636–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galbiati, F.; Roy, D.S.; Simonini, S.; Cucinotta, M.; Ceccato, L.; Cuesta, C.; Simaskova, M.; Benkova, E.; Kamiuchi, Y.; Aida, M.; et al. An integrative model of the control of ovule primordia formation. Plant J. 2013, 76, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.P.; Montgomery, T.A.; Fahlgren, N.; Kasschau, K.D.; Nonogaki, H.; Carrington, J.C. Repression of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR10 by microRNA160 is critical for seed germination and post-germination stages. Plant J. 2007, 52, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodharan, S.; Zhao, D.Z.; Arazi, T. A common miRNA160-based mechanism regulates ovary patterning, floral organ abscission and lamina outgrowth in tomato. Plant J. 2016, 86, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodharan, S.; Corem, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Arazi, T. Tuning of SlARF10A dosage by sly-miR160a is critical for auxin-mediated compound leaf and flower development. Plant J. 2018, 96, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Tian, L.; Sun, M.X.; Huang, X.Y.; Zhu, J.; Guan, Y.F.; Jia, Q.S.; Yang, Z.N. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR17 is essential for pollen wall pattern formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, R. Food security. Nature 2017, 544, S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, A.B.; Yadav, I.S.; Vikal, Y.; Praba, U.P.; Kaur, N.; Gill, A.S.; Joha, G.S. Transcriptional dynamics of maize leaves, pollens and ovules to gain insights into heat stress-related responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1117136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tilman, D.; Jin, Z.N.; Smith, P.; Barrett, C.B.; Zhu, Y.G.; Burney, J.; D’Odorico, P.; Fantke, P.; Fargione, J.; et al. Climate change exacerbates the environmental impacts of agriculture. Science 2024, 385, eadn3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martre, P.; Dueri, S.; Guarin, J.R.; Ewert, F.; Webber, H.; Calderini, D.; Molero, G.; Reynolds, M.; Miralles, D.; Garcia, G.; et al. Global needs for nitrogen fertilizer to improve wheat yield under climate change. Nat. Plants 2024, 10, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.Q.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, G.; Shi, J.; Wang, D.X.; Zhu, W.W.; Yang, X.J.; Dreni, L.; Tucker, M.R.; Zhang, D.B. MADS8 is indispensable for female reproductive development at high ambient temperatures in cereal crops. Plant Cell 2023, 36, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.J.; Tucker, M.R. Establishing a regulatory blueprint for ovule number and function during plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudall, P.J. Evolution and patterning of the ovule in seed plants. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, S.H.; Jiang, Y.T.; Chang, J.H.; Zhang, Y.J.; Xue, H.W.; Lin, W.H. Interaction of brassinosteroid and cytokinin promotes ovule initiation and increases seed number per silique in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, M.; Marzo, M.D.; Guazzotti, A.; de Folter, S.; Kater, M.M.; Colombo, L. Gynoecium size and ovule number are interconnected traits that impact seed yield. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 2479–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.Q.; Xie, M.Y.; Jiang, Y.M.; Yuan, T. Abortion occurs during double fertilization and ovule development in Paeonia ludlowii. J. Plant Res. 2022, 135, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.Y.; Liu, Q.Y.; Luo, Y.J.; Zhu, P.P.; Guan, P.Y.; Zhang, J.X. Study on influencing factors of embryo rescue and germplasm innovation in seedless grape. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2024, 157, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.C.; Lin, T.S.; Chang, J.C. Pollen effects on fruit set, seed weight, and shriveling of ‘73-S-20’ Litchi-with special reference to artificial induction of parthenocarpy. Hort. Sci. 2015, 50, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.W.; Li, Q.L.; Hu, G.B.; Qin, Y.H. Comparative transcriptional survey between self-incompatibility and self-compatibility in Citrus reticulata Blanco. Gene 2017, 609, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijesinghe, S.A.E.C.; Evans, L.J.; Kirkland, L.; Rader, R. A global review of watermelon pollination biology and ecology: The increasing importance of seedless cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 271, 109493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawar, A.; Chen, W.; Zhu, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.X.; Xiong, S.Q.; Ito, T.; Chen, D.J.; Sun, B. The histone acetyltransferase GCN5 regulates floral meristem activity and flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.N.; Jia, P.F.; Wang, W.; Chen, L.C.; Gong, X.R.; Lin, H.F.; Wu, R.; Yang, W.C.; Li, H.J.; Zuo, J.R.; et al. S-Sulfenylation-mediated inhibition of the GSNOR1 activity regulates ovule development in Arabidopsis. J. Genet. Genom. 2025, 52, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.