Abstract

Rhododendrons naturally inhabit acidic soils where aluminum (Al) toxicity severely restricts plant growth, yet the molecular basis underlying cultivar-dependent differences in Al tolerance remains poorly understood. In this study, we compared the transcriptional and physiological responses of an Al-resistant cultivar (Kangnaixin) and an Al-sensitive cultivar (Baijinpao) under Al stress. Transcriptome analysis was performed to identify Al-responsive differentially expressed genes (DEGs), followed by Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses to elucidate functional categories and metabolic pathways involved in stress adaptation. In addition, the Al tolerance-related gene RsALS3 was cloned and functionally characterized through heterologous overexpression in Arabidopsis thaliana. The two cultivars exhibited distinct transcriptional profiles in response to Al stress, with DEGs significantly enriched in abiotic stress responses, membrane-associated functions, and key metabolic pathways, including starch and sucrose metabolism, phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthesis, and photosynthesis-related processes. These results suggest that Al stress disrupts membrane integrity and alters carbon metabolism in Rhododendron. Functional validation demonstrated that RsALS3 overexpression moderately alleviated Al-induced toxicity in A. thaliana, as evidenced by reduced leaf damage and improved photosynthetic efficiency. Although the observed phenotypic differences were modest, and some chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics data did not reach strong statistical significance. The overall physiological trends support a potential role of RsALS3 in Al stress adaptation. Collectively, these findings provide insight into cultivar-specific Al stress responses in Rhododendron and identify RsALS3 as a promising candidate gene for further investigation aimed at improving adaptation to acidic soils.

1. Introduction

Acidic soils, predominantly distributed in tropical and subtropical regions, account for approximately 40–50% of the world’s potential arable land [1]. In China, such soils are mainly located in the southwestern region, covering an area of 2.03 × 108 hectares, which represents about 21% of the nation’s cultivable land [2,3,4]. One of the major constraints limiting plant growth in acidic soils is aluminum (Al) toxicity [5]. Under neutral or slightly acidic conditions, Al is primarily present as insoluble silicates and oxides that pose minimal risk to plant growth. However, under acidic conditions, Al is solubilized into its trivalent form (Al3+), a highly phytotoxic ion [6,7]. Al3+ inhibits root elongation, disrupts nutrient uptake and homeostasis, impairs photosynthesis, induces oxidative stress, and ultimately suppresses plant growth and development [6,8,9,10]. To cope with Al toxicity, plants have evolved diverse defense strategies, broadly classified into Al exclusion mechanisms at the root surface and internal detoxification mechanisms following Al uptake [2].

With the rapid development of high-throughput sequencing technologies, numerous studies have elucidated the molecular mechanisms underlying plant responses to Al stress. In rice, the transcription factor OsART1 regulates a network of Al-responsive genes involved in Al detoxification [11]. In maize, genes encoding enzymes of the citrate cycle and several specifically expressed genes positively regulate Al tolerance [12]. Al-activated malate transporters (ALMTs) mediate malate exudation into the rhizosphere, where malate chelates Al3+, thereby conferring Al resistance in species such as wheat [13], Arabidopsis [14], rye [15], and barley [16]. In addition, members of the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family, which encode citrate transporters, play a pivotal role in Al detoxification, with functional homologs identified in sorghum [17], barley [18], Arabidopsis [19], wheat [20], rye [21] and rice [22,23]. ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, which utilize ATP to transfer molecules across the plasma membrane, are crucial for Al tolerance. In Arabidopsis, ALS1 and ALS3 are ABC transporter genes involved in Al tolerance [24,25], while in rice, knockout mutants of STAR1 and STAR2 exhibit hypersensitivity to Al stress [26]. The natural resistance-associated macrophage protein (NRAMP) family further contributes to Al tolerance in cereals. For example, in rice, Nrat1, localized at the plasma membrane of root tip cells, functions in the retrieval of Al3+ from the cell wall and facilitates its sequestration into vacuoles to mitigate toxicity [27,28,29]. The transcription factor OsWRKY22 enhances Al-induced citrate exudation by activating OsFRDL4 expression through direct binding to W-box elements in its promoter region [30]. Furthermore, secondary metabolic pathways, particularly the phenylpropanoid pathway, are increasingly recognized for their roles in cell wall reinforcement and oxidative stress mitigation under Al exposure. In Neolamarckia cadamba, the expression of key lignin biosynthesis enzymes is elevated under Al stress [31], and in Pinus massoniana, upregulation of genes such as Pm4CL, PmCAD, and PmCOMT contributes to cellular adaptation during prolonged Al exposure [32].

The ALS3 (Aluminum sensitive 3) gene encodes an ABC transporter lacking a nucleotide-binding domain but containing seven predicted transmembrane domains and is primarily expressed in the phloem and root cortex [1]. In Arabidopsis, ALS3 forms a functional complex with STAR1 at the tonoplast to redistribute Al away from sensitive tissues [24,33]. In rice, the homologs OsSTAR1 and OsSTAR2 localize to vesicles and may be involved in the transport of UDP-glucose to the cell wall [26]. Rhododendron, a genus of the Ericaceae family, is widely distributed in acidic soils and holds significant ornamental and economic value [34]. China serves as a global center of Rhododendron diversity, harboring more than 571 species, accounting for 55% of the global total [35,36]. Most of these species are predominantly distributed in the acidified soils of southwestern China [37]. Their ability to thrive in Al-rich acidic soils suggests the presence of specialized tolerance mechanisms. In Rhododendron yunnanense, for instance, the Al transporter RyALS3;1 is localized to the vacuolar membrane, and its overexpression in Nicotiana tabacum enhances Al resistance [38]. Despite their natural adaptation to acidic environments, the molecular mechanisms underlying Al tolerance in Rhododendron remain poorly characterized [39]. In this study, we performed a comparative transcriptomic analysis of the Al-sensitive cultivar ‘Baijinpao’ and the Al-tolerant cultivar ‘Kangnaixin’ under Al stress. We identified the Al-responsive gene, RsALS3, and conducted functional validation through heterologous overexpression in A. thaliana. Our results provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms of Al stress responses in Rhododendron and identify candidate genes for improving tolerance to acidic soils.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Treatment

Rhododendron hybridum ‘Baijinpao’ (Al-sensitive) and ‘Kangnaixin’ (Al-tolerant) were obtained from Jiashan United Agricultural Technology Co., Ltd. (Jiaxing, China). 12 evenly uniform and healthy seedlings were selected for each cultivar (a total of 24 seedlings). All seedlings were transplanted into plastic pots (25 cm diameter) containing acidic red soil (pH 4.48) collected from Gaoligong Mountain region, Yunnan Province, China. Prior to treatment, plants were acclimated for 15 days in an artificial climate incubator under the following conditions: 25 °C/18 °C (day/night), 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod, 70% relative humidity, and a photosynthetic photon flux density of 600 µmol m−2 s−1. For each cultivar, the 12 seedlings were randomly divided into two groups with six biological replicates per group. Al stress was imposed by irrigating plants with 0.5 mM AlCl3 solution prepared in ultrapure water, while control plants received an equal volume of ultrapure water without Al addition. Treatments were applied every two days for a period of 10 days. After treatment, fully expanded leaves from the upper canopy were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for physiological measurements and RNA extraction. Samples were designated as CK14 (Baijinpao control), Al14 (Baijinpao Al-treated), CK16 (Kangnaixin control), and Al16 (Kangnaixin Al-treated). For transcriptome sequencing, three biological replicates were randomly selected from each treatment group to construct 12 cDNA libraries. For physiological and phenotypic analyses, three independent biological replicates per treatment were used.

2.2. RNA Extraction, Library Construction, and Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from frozen leaf tissues using EASYspin Plus Complex Plant RNA Kit (Aidlab, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and RNA integrity was evaluated with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). cDNA libraries were constructed using poly(A) mRNA enrichment, fragmentation, and double-stranded cDNA synthesis. High-throughput sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Hangzhou Huanran Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China).

2.3. Read Processing, Mapping, and Transcriptome Data Analysis

Raw sequencing reads were processed using Cutadapt v2.10 to remove adapter sequences, low-quality reads (average Phred quality score < Q20), and reads containing more than 5% ambiguous bases (N). The resulting high-quality clean reads were used for subsequent analysis. Clean reads were aligned to the Rhododendron simsii reference genome using Tophat2 v2.1.1 with parameters: --microexon-search and --library-type=fr-firststrand. For reads mapped to annotated transcripts or genes, Bowtie2 v2.5.4 was employed with default parameters to ensure accurate alignment. DEGs between pairwise comparisons were identified using DESeq2 (v1.38.3). Genes with |log2FoldChange| > 1 and adjusted p-value (padj) < 0.05, were considered significantly differentially expressed, with multiple testing correction performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) method to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Functional annotation of DEGs was conducted using eggNOG-mapper v5.0 for Gene Ontology (GO) annotation and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS) using the bi-directional best hit (BBH) method for KEGG pathway annotation. Pearson correlation analysis for DEGs involved in phenypropanoid biosynthesis and flavonoid biosynthesis was performed using cnsknowall online platform (https://www.cnsknowall.com/, accessed on 10 September 2025).

2.4. qRT-PCR Validation

To validate the RNA-seq results, eight DEGs were randomly selected for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. Reactions were performed on a LightCycler® 480 II instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) using a commercial MonAmpTM SYBR® Green qPCR Mix kit (Monad Biotech Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China). The reaction procedure was carried out as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, followed by melting curve analysis. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (GAPDH) was selected as the internal reference gene based on previous studies demonstrating its stable expression in Rhododendron species [40,41,42]. Primer sequences are shown in Table S1. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method. Each reaction was performed with three technical replicates.

2.5. Bioinformatics and Cloning of RsALS3

The structural domains of the RsALS3 gene were predicted using the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/, accessed on 15 October 2025). Physicochemical properties were analyzed with the ExPASy—ProtParam tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 15 October 2025), and subcellular localization was predicted using WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/, accessed on 15 October 2025). Homologous RsALS3 sequences from related plant species were retrieved from the NCBI database using BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, accessed on 15 October 2025), aligned with DNAMAN (v 6.0), and used to construct a phylogenetic tree in MEGA5.0 using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Conserved motifs were identified using the MEME 5.5.1 suite (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme, accessed on 15 October 2025) and visualized with TBtools (v1.120). The full-length coding sequence of RsALS3 was amplified from cDNA of the CK14 using gene-specific primers (Table S2) and TransStart® FastPfu Fly DNA Polymerase (TransGen, Beijing, China). The amplified fragment was subsequently cloned into the pCAMBIA1300-GFP vector to generate the overexpression construct.

2.6. Arabidopsis Transformation and Phenotypic Analysis

The RsALS3 overexpression construct was introduced into wild-type (WT) A. thaliana via Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101)-mediated floral dip. Transgenic T1 plants were selected on kanamycin/ rifampicin-containing medium. Homozygous T3 lines were confirmed by PCR and qRT-PCR. WT and transgenic (OE-RsALS3) plants were treated with 100 mL of 0.5 mM AlCl3 solution or sterile water (control). Phenotypic and photosynthetic parameters were measured at 0, 24, and 48 h using a Li-6400 XT portable photosynthesis system (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) and a Multifunctional Plant Efficiency Analyzer (M-PEA, Hansatech Instruments, Pentney, UK).

3. Results

3.1. Transcriptome Sequencing and Assembly

High-quality transcriptome sequencing generated 33.81 Gb of raw data from 12 cDNA libraries. After stringent quality filtering, the clean reads exhibited GC contents ranging from 46.15% to 46.57%. The average percentages of bases with Phred quality scores ≥ Q20 and ≥Q30 exceeded 97.5% and 93.0%, respectively, indicating high sequencing accuracy and data reliability. Clean reads were mapped to the Rhododendron reference genome (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_047301955.1/, accessed on 10 September 2025), yielding an average mapping rate of 82.92% across all samples (Table S3). These quality metrics demonstrate that the sequencing data were of sufficient quality to support subsequent transcriptomic analyses.

3.2. DEGs Analysis

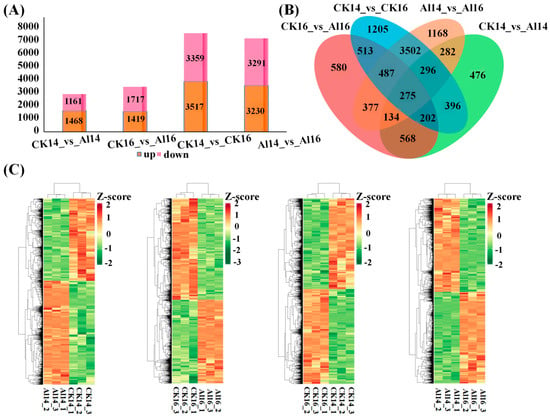

To characterize transcriptional responses to Al stress, pairwise comparisons were conducted to identify DEGs among the sample groups. A total of 2629 DEGs were identified in the CK14 vs. Al14 comparison, including 1468 upregulated and 1161 downregulated genes. In CK16 vs. Al16 comparison, 3136 DEGs were detected, comprising 1419 upregulated and 1717 downregulated genes. Comparisons between cultivars revealed 6876 DEGs (3517 upregulated and 3359 downregulated) in CK14 vs. CK16 and 6521 DEGs (3230 upregulated and 3291 downregulated) in Al14 vs. Al16 (Figure 1A). Across all the comparison groups, the number of upregulated genes exceeded that of downregulated genes. Notably, 275 core DEGs were commonly identified in both cultivars in response to Al stress. In addition, cultivar-specific DEGs were detected, including 470 in CK14 vs. Al14, 580 in CK16 vs. Al16, 1205 in CK14 vs. CK16, and 1168 in Al14 vs. Al16 (Figure 1B). Hierarchical clustering analysis further revealed distinct expression patterns among the different treatment groups and cultivars (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Change in DEG expression. (A) Number of upregulated and downregulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified in pairwise comparisons. (B) Venn diagram showing the overlap of DEGs significantly altered by aluminum (Al) stress in both cultivars (core DEGs) and cultivar-specific DEGs. (C) Heatmap depicting expression patterns of DEGs across all samples and comparison groups. The color scale indicates log2 (fold change).

3.3. Functional Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

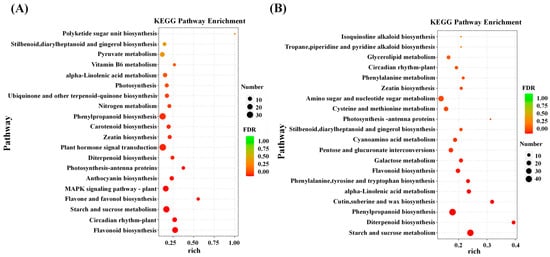

To elucidate the biological functions of Al-responsive genes, GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed. In CK14 vs. Al14, 5362 GO terms were identified, including 3593 biological processes (BP), 490 cellular components (CC), and 1279 molecular functions (MF) terms. Similarly, 5579 GO terms were obtained for CK16 vs. Al16, comprising 3871 BP, 435 CC, and 1273 MF terms (Table S4). In both cultivars, DEGs were significantly enriched in BP categories associated with abiotic stress responses and rhythmic processes, as well as in CC categories related to membrane-associated components (Figure S1). These results indicate that Al stress strongly affects stress-responsive processes and membrane-related cellular structures. To further investigate the metabolic pathways involved in Al stress responses, DEGs were mapped to the KEGG database (Table S5). A total of 105 and 112 KEGG pathways were significantly enriched in CK14 vs. Al14 and CK16 vs. Al16, respectively. Notably, several photosynthesis-related pathways, including photosynthesis (ko00195), photosynthesis–antenna proteins (ko00196), and carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms (ko00710), were significantly enriched, suggesting that Al stress markedly influences photosynthetic processes (Table S6). In addition, DEGs were significantly enriched in pathways related to starch and sucrose metabolism, diterpenoid biosynthesis, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and flavonoid biosynthesis (Figure 2), reflecting extensive alterations in energy metabolism and secondary metabolic processes under Al stress.

Figure 2.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs. Bubble plots showing significantly enriched KEGG pathways (p < 0.05) for DEGs in (A) CK14 vs. Al14 and (B) CK16 vs. Al16.

3.4. Expression Profiles of Genes Involved in Phenylpropanoid and Flavonoid Biosynthesis

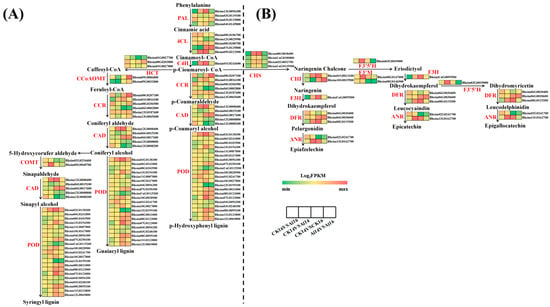

The phenylpropanoid (ko00940) and flavonoid (ko00941) biosynthesis pathways were consistently enriched across comparisons, although enrichment intensity varied between cultivars. A total of 49 DEGs associated with the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway were identified. In the CK16 vs. Al16, 11 genes were upregulated, including two PAL, one 4CL, two HCT, three CCR, two POD and one CCoAOMT. In CK14 vs. Al14, 14 genes were upregulated, with additional induction of C4H, COMT, and CAD. Comparisons between cultivars revealed that prior to Al treatment, ‘Kangnaixin’ exhibited 23 upregulated and 14 downregulated phenylpropanoid-related genes relative to ‘Baijinpao’, whereas after Al treatment, 17 upregulated and seven downregulated genes were detected. For flavonoid biosynthesis, 18 DEGs were identified. In CK16 vs. Al16, three genes (DFR, LAR, ANR) were upregulated, while in CK14 vs. Al14, 11 genes were upregulated, including multiple CHS, CHI, and F3H genes. These expression patterns indicate that transcriptional regulation of phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthetic genes is cultivar-dependent and may contribute to differential Al stress responses (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Heatmaps showing expression levels of key genes in (A) phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and (B) flavonoid biosynthesis pathways under CK16 vs. Al16 and CK14 vs. Al14 comparisons. PAL, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase; 4CL, 4-coumarate -CoA ligase; C4H, trans-cinnamate4-monooxygenase; HCT, shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase; CCoAOMT, caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase; CCR, cinnamoyl-CoA reductase; COMT, caffeic acid 3 Omethyltransferase; CAD, cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase; POD, peroxidase; CHS, chalcone synthase; CHI, chalcone isomerase; F3′5′H, flavonoid 3′,5′ hydroxylase; F3′M, flavonoid 3′ monooxygenase; F3H, naringenin 3-dioxygenase; DFR, bi-functional dihydroflavonol 4 -reductase; ANR, anthocyanidin reductase.

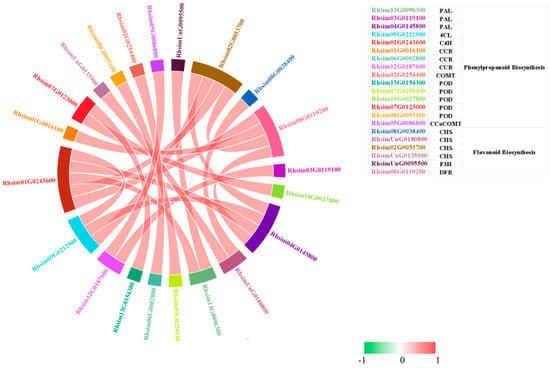

To further explore regulatory interactions among these pathways under Al stress, Pearson correlation analysis was conducted for DEGs involved in phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthesis. This analysis revealed strong intergene correlations and identified 21 highly correlated hub genes (Figure 4). Among these, 15 DEGs were associated with the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway, including PAL (Rhsim13G0096300, Rhsim03G0119100, Rhsim04G0145800), CCR (Rhsim01G0016100, Rhsim06G0002800, Rhsim12G0187600), POD (Rhsim13G0154300, Rhsim07G0250100, Rhsim10G0027800, Rhsim07G0123000, Rhsim08G0095100), and one gene each encoding 4CL (Rhsim09G0212900), C4H (Rhsim01G0243600), COMT (Rhsim02G0254400), and CCoAOMT (Rhsim05G0086800). Additionally, six DEGs involved in the flavonoid biosynthesis were identified, including four CHS genes (Rhsim08G0038400, RhsimUnG0180800, Rhsim02G0053700, RhsimUnG0135900), one F3H gene (RhsimUnG0095500), and one DFR gene (Rhsim08G0119200). These genes are likely represent key regulatory nodes associated with Al stress responses.

Figure 4.

Pearson correlation network of DEGs involved in phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthesis. Correlation network constructed based on Pearson correlation coefficients (|r| > 0.9, p < 0.01). Edge width reflects correlation strength; red edges indicate positive correlations, whereas green edges indicate negative correlations.

3.5. qRT-PCR Verification

Eight DEGs related to Al stress responses were selected for qRT-PCR validation. The expression patterns determined by qRT-PCR were consistent with the RNA-seq results, confirming the reliability and reproducibility of the transcriptomic data (Figure S2).

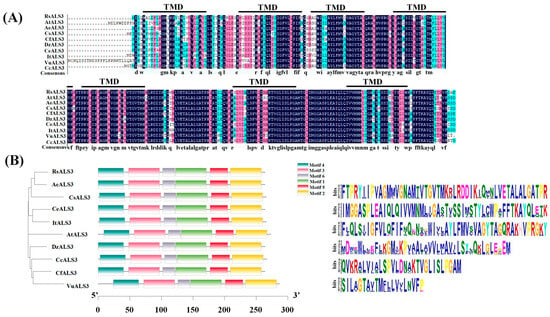

3.6. Identification and Characterization of the RsALS3

Several Al-responsive genes homologous to known Al tolerance-related genes, including STOP1, STOP2, FDH, ALS3, and RPI2, were identified from the transcriptome dataset (Table S7). Among these candidates, Rhsim05G0184400 (RsALS3) encodes an aluminum-induced ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter and was significantly induced in two Rhododendron cultivars under Al stress, indicating its potential involvement in Al stress responses. The full-length coding sequence of RsALS3 was successfully cloned (Figure S3A) and was found to encode a protein of 264 amino acids. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that RsALS3 clustered most closely with AeALS3 from Actinidia eriantha (Figure S3B). Multiple sequence alignment demonstrated a high degree of conservation among ALS3 proteins from different plant species (Figure 5A). Conserved motif analysis showed that RsALS3 and its homologs from nine other plant species shared identical conserved motifs (Figure 5B). Subcellular localization prediction showed that RsALS3 was localized to the tonoplast.

Figure 5.

Sequence conservation and motif analysis of RsALS3. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of RsALS3 with ALS3 homologs from related plant species. (B) Distribution of conserved protein motifs identified by MEME analysis in RsALS3 and orthologs. Motifs are represented by colored boxes.

3.7. RsALS3 Confers Al Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis

To assess the role of RsALS3 in Al tolerance, transgenic A. thaliana lines overexpressing RsALS3 (OE-RsALS3) were generated. The overexpression construct was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens and transferred into Arabidopsis via the floral dip method. Transgenic T1 plants were initially screened by PCR and gel electrophoresis (Figure S4A), and two independent lines were advanced to the homozygous T3 generation. qRT-PCR confirmed stable and elevated expression of RsALS3 in T3 plants (Figure S4B). Phenotypic responses to Al stress were evaluated at 0, 24, and 48 h after treatment. After 48 h of exposure to Al, WT plants exhibited leaf curling and chlorosis, whereas OE-RsALS3 plants showed comparatively milder symptoms, indicating improved Al tolerance conferred by RsALS3 overexpression (Figure S5).

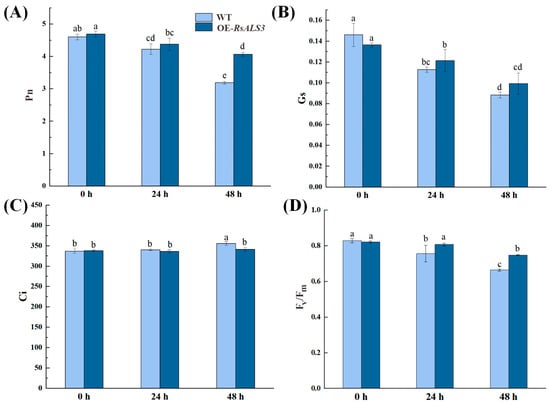

After 48 h of Al treatment, WT plants showed significant reductions in net photosynthetic rate (Pn) and stomatal conductance (Gs) by 30.7% and 39.5%, respectively, accompanied by a 5.6% increase in intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci). In contrast, OE-RsALS3 plants displayed less severe decreases in Pn (25.3%) and Gs (27.2%), as well as a smaller increase in Ci (0.99%) (Figure 6A–C). Moreover, the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) (Fv/Fm) decreased by 20.0% in WT but only 8.9% in OE-RsALS3, indicating a better preservation of photosynthetic efficiency in the transgenic lines under Al stress (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in response to Al stress. Changes in (A) net photosynthetic rate (Pn), (B) stomatal conductance (Gs), (C) intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), and (D) maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) (Fv/Fm). Note: Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences among groups at p < 0.05 according to one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Bars sharing the same letter are not significantly different.

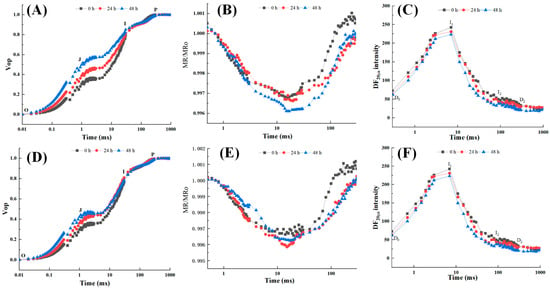

Both WT and OE-RsALS3 plants exhibited typical OJIP chlorophyll fluorescence transients. However, after 48 h of Al treatment, WT plants showed more pronounced alterations in OJIP curves, particularly at the J and P phases, compared with OE-RsALS3 plants (Figure 7A,D). Consistently, modulated reflection at 820 nm (MR820 nm) curves revealed greater changes in WT, with a more pronounced decline at the lowest point relative to OE-RsALS3 (Figure 7B,E). Delayed fluorescence (DF) signals decreased in both genotypes following Al exposure; however, the magnitude of reduction was greater in WT plants. Specifically, DF values decreased by 36.0% (D0), 17.0% (I1), and 28.0% (I2) in WT plants, whereas reductions of 14.1%, 7.8%, and 25.3% were observed in OE-RsALS3 plants, respectively (Figure 7C,F). These findings suggest that RsALS3 overexpression partially mitigates Al-induced impairment of photosynthetic performance, likely by maintaining PSII activity and electron transport efficiency.

Figure 7.

Chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics in response to Al stress. Changes in (A,D) prompt fluorescence (OJIP transients), (B,E) modulated reflection at 820 nm (MR820nm), and (C,F) delayed fluorescence (DF) kinetics in WT (Upper panels) and OE-RsALS3 (Lower panels) plants after 48 h of 0.5 mM AlCl3 treatment.

4. Discussion

Rhododendrons are widely valued not only for their ornamental appeal but also for their medicinal and ecological importance. For instance, Rhododendron dauricum synthesizes daurichromenic acid, a compound with strong anti-HIV activity [43], which has stimulated increasing interest in Rhododendron research [44]. With the global expansion of acidic soils, Al toxicity has emerged as a major abiotic stress factor severely restricting plant growth and development [2]. Although Rhododendron species are naturally adapted to acidic environments, the molecular mechanisms underlying cultivar-specific differences in Al tolerance remain poorly understood. In this study, transcriptomic analysis of the Al-tolerant ‘Kangnaixin’ and Al-sensitive ‘Baijinpao’ revealed substantial differences in gene expression patterns under Al stress, reflecting divergent tolerance strategies. Previous study has shown that Al stress can damage the chloroplast envelopes, reduce chlorophyll content, and inhibit photosynthetic enzyme activity, ultimately leading to reduced photosynthetic capacity [45]. Consistent with these findings, genes associated with photosynthesis were strongly affected by Al stress in the present study. Notably, all nine photosynthesis-related DEGs identified in ‘Baijinpao’ were down-regulated following 10 days of Al treatment, whereas only two DEGs were detected in ‘Kangnaixin’. Most of these genes were associated with PSII, photosystem I (PSI) and F-type ATPase (Table S6), indicating that these components may be particularly vulnerable to Al stress in Rhododendrons. Light-harvesting complexes (LHCs), which are located on the chloroplast thylakoid membrane and play a central role in capturing and transferring light energy to reaction centers, are essential for maintaining photosynthetic efficiency [46,47]. In the photosynthesis-antenna proteins pathway, 10 LHC-related DEGs were identified in both cultivars. Following Al treatment, most LHC-related genes in ‘Baijinpao’ were downregulated, while all corresponding genes in ‘Kangnaixin’ were upregulated (Table S6). This contrasting expression pattern suggests that ‘Kangnaixin’ may better maintain light capture and energy transfer under Al stress, thereby supporting a more stable photosynthetic apparatus compared with ‘Baijinpao’.

The plant cell wall represents a major site for heavy metal binding and serves as the first barrier limiting metal uptake and translocation [48,49]. Al3+ ions readily bind to pectin and hemicellulose residues in the apoplast, altering cell wall properties and affecting root elongation [50]. In this study, Al stress markedly induces the expression of genes involved in the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway. Lignin, a major structural component of the plant cell wall, contributes to metal immobilization and cell wall stiffening, thereby enhancing tolerance to metal stress [51,52]. Previous studies have shown that the overexpression of 4CL in Arabidopsis improves drought tolerance by enhancing antioxidant capacity and reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation [53]. Similarly, CCoAOMT-mediated lignin biosynthesis is essential for copper stress resistance in rice [51]. In Pinus radiata, silencing of the HCT reduces lignin content and alters lignin composition [54], while antisense overexpression of MsCOMT in tobacco affects both lignin and total phenolic content [55]. Furthermore, upregulation of 4CL and CAD promotes lignin accumulation, secondary cell wall thickening, and enhanced tolerance to salt and osmotic stress in birch and apple [56,57]. We also found that under Al stress, a large number of POD gene expressions are upregulated [58]. Consistent with these findings, we observed significant upregulation of multiple phenylpropanoid-related genes, including PAL, 4CL, C4H, HCT, CCoAOMT, COMT, CCR, CAD and POD, across all four comparison groups under Al stress (Figure 3A). Flavonoids are widely distributed secondary metabolites with diverse physiological functions, including antioxidative defense, UV protection, and pigmentation [59]. In response to Al stress, three and 11 flavonoid biosynthesis genes were upregulated in CK16 vs. Al16 and CK14 vs. Al14, respectively. The stronger induction of flavonoid biosynthetic genes in ‘Baijinpao’ suggests that Al stress may elicit a more pronounced oxidative challenge in the sensitive cultivar, triggering a compensatory antioxidant response. Thus, activation of flavonoid biosynthesis likely contributes to alleviating oxidative damage under Al stress, particularly in Al-sensitive genotypes.

To further explore the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying Al stress responses, we identified and functionally validated the gene RsALS3. In Arabidopsis, ALS3 encodes an ABC transporter that participates in redistributing Al away from sensitive tissues, thereby contributing to Al tolerance [24]. Bioinformatic analyses revealed that RsALS3 shares conserved amino acid domains with homologs from Actinidia eriantha, Camellia sinensis, Coffea eugenioides, Ipomoea triloba and other species (Figure 5), indicating functional conservation. Subcellular localization prediction indicated that RsALS3 is localized to the tonoplast, consistent with previous observations in Rhododendron delavayi [38]. Functional validation in a heterologous system showed that transgenic A. thaliana plants overexpressing RsALS3 exhibited milder Al-induced damage than WT plants (Figure S5), suggesting that RsALS3 contributes to Al stress adaptation. Abiotic stress often triggers physiological alterations prior to visible phenotypic changes, and photosynthesis is particularly sensitive to Al toxicity [60]. In this study, both WT and OE-RsALS3 plants exhibited reduced Pn and Gs, accompanied by increased Ci, indicating that non-stomatal limitations, likely associated with chloroplast disturbance, played a major role in photosynthetic inhibition. These changes were more pronounced in WT plants, suggesting greater physiological disruption (Figure 6A–C). Furthermore, Fv/Fm, a widely used indicator of PSII photoinhibition [61,62], declined in both genotypes after 48 h of Al treatment, with a greater reduction observed in WT plants (Figure 6D). This indicates that although both genotypes suffered Al-induced damage, OE-RsALS3 plants maintained comparatively higher photosynthetic efficiency, supporting a potential role of RsALS3 in alleviating Al stress. Chlorophyll fluorescence is widely used as an indicator of photosynthetic performance and indirectly reflects the fluctuations of photosynthetic electron transport [63]. The simultaneous measurement of prompt fluorescence (PF), DF and MR820nm has been extensively applied in various fields [64,65,66]. The rise in chlorophyll fluorescence from the O point to the P point following dark adaptation primarily reflects changes in the initial photochemical reactions of PSII [67,68]. Under Al stress, both WT and OE-RsALS3 plants showed increases in the J and I phases of the OJIP transient, with a more pronounced rise at the J phase in WT plants (Figure 7A,D), implying stronger inhibition of electron transfer at the QA site [69]. MR820nm measurements, which reflect the redox state of plastocyanin (PC) and P700 [62,70], showed a larger decline in WT plants than in OE-RsALS3 plants (Figure 7B,E), indicating more severe disruption of electron transport from PSII to PSI [60,71]. Additionally, DF signals, which depend on reverse electron transport in PSII reaction centers (RCs) [72,73], decreased more markedly in WT plants, as evidenced by larger reductions in the D0, I1, and I2 points (Figure 7C,F). Collectively, these findings indicate that photosynthetic electron transport was more severely impaired in WT plants than in OE-RsALS3 plants, providing further support for the potential involvement of RsALS3 in Al stress response.

It should be noted that the functional validation in this study was conducted in a heterologous system. Although the observed physiological trends support a potential role for RsALS3 in Al stress adaptation, definitive evidence linking RsALS3 to the natural variation in Al tolerance between ‘Kangnaixin’ and ‘Baijinpao’ requires further investigation. Future studies should quantify RsALS3 expression in roots and shoots of these two cultivars under Al stress to establish a clear correlation with their differential tolerance. Moreover, detailed growth analyses, such as measuring primary root length and biomass on both Al-containing and Al-free media, would be necessary to conclusively demonstrate that RsALS3 overexpression alleviates growth inhibition. Thus, the present results position RsALS3 as a promising candidate gene involved in Al stress responses, warranting deeper investigation into its precise mechanism of action and its contribution to cultivar-specific tolerance in Rhododendron.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive analysis of the transcriptional and physiological responses to Al stress in two Rhododendron cultivars with contrasting Al tolerance. A large number of Al-responsive DEGs were identified, which were mainly involved in abiotic stress responses, membrane-associated functions, and critical metabolic pathways such as starch and sucrose metabolism, diterpenoid biosynthesis, phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthesis, and photosynthesis-antenna proteins. These results indicate that Al stress disrupts membrane integrity, alters secondary metabolism, and impairs photosynthetic performance in Rhododendron. Importantly, the Al-responsive gene RsALS3 was identified and functionally characterized in transgenic Arabidopsis. Overexpression of RsALS3 resulted in improved physiological performance under Al stress, suggesting its involvement in Al stress adaptation. Together, these findings enhance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying Al tolerance in Rhododendron and identify RsALS3 as a promising candidate for future studies aimed at improving adaptation to acidic soils.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12010022/s1, Figure S1: Bubble diagram of GO enrichment analysis. (A) CK14 vs. Al14. (B) CK16 vs. Al16; Figure S2: qRT-PCR analysis of of DEGs; Figure S3: Gene cloning and phylogenetic tree; Figure S4: Identification of OE-RsALS3 in Arabidopsis thaliana. (A) DNA identification; (B) Identification by qRT-PCR; Figure S5: Phenotypic change in response to Al stress; Table S1: qRT-PCR primer sequence; Table S2: Gene cloning primer sequence; Table S3: Transcriptome data quality evaluation analysis; Table S4: GO enrichment analysis of CK14 vs. Al14, CK16 vs. Al16, CK14 vs. Al16, Al14 vs. Al16; Table S5: KEGG enrichment analysis of CK14 vs. Al14, CK16 vs. Al16, CK14 vs. Al16, Al14 vs. Al16; Table S6: ko00195 (photosynthesis) pathway, ko00196 (photosynthesis-antenna proteins) pathway and ko00710 (Carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms) pathway; Table S7: Identification of homologous genes related to aluminum resistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L.; methodology, X.L. and J.Z.; software, Y.S.; validation, J.Z. and Z.W. (Zhongxu Wang); investigation, X.L., J.Z. and C.Y.; resources, C.Y.; data curation, Z.W. (Zhongxu Wang); writing—original draft preparation, X.L. and J.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.W. (Ziyun Wan) and S.J.; supervision, S.J.; project administration, Z.W. (Ziyun Wan); funding acquisition, S.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Project (2019YFE0118900).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive repository, accession number PRJNA1179657.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kochian, V.L.; Piñeros, A.M.; Liu, J.; Magalhaes, J.V. Plant adaptation to acid soils: The molecular basis for crop aluminum resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 571–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jipsi, C.; Singh, S.K. Mechanisms underlying the phytotoxicity and genotoxicity of aluminum and their alleviation strategies: A review. Chemosphere 2021, 278, 130384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, P.R.; Delhaize, E. The convergent evolution of aluminium resistance in plants exploits a convenient currency. Funct. Plant Biol. 2010, 37, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.L.; Xie, G.N.; Zhang, X.X.; Qiu, L.Q.; Wang, N.; Zhang, S.Z. Process and mechanism of plants in overcoming acid soil aluminum stress. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 24, 3003–3011. [Google Scholar]

- Rout, G.; Samantaray, S.; Das, P. Aluminium toxicity in plants: A review. Agronomie 2001, 21, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, S.; Balaji, M.; Varalakshmi, S.; Jogeswar, G.; Sunita, M.S.L.; Prashanth, S.; Kishor, P.B.K. Toxicity and tolerance of aluminum in plants: Tailoring plants to suit to acid soils. Biometals 2016, 29, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Piñeros, M.A.; Kochian, L.V. The role of aluminum sensing and signaling in plant aluminum resistance. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2014, 56, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delisle, G.; Champoux, M.; Houde, M. Characterization of oxalate oxidase and cell death in Al-sensitive and tolerant wheat roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001, 42, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Devi, S.R.; Rikiishi, S.; Matsumoto, H. Oxidative stress triggered by aluminum in plant roots. Plant Soil 2003, 255, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.A.M.; Panda, B.B. Aluminium-induced DNA damage and adaptive response to genotoxic stress in plant cells are mediated through reactive oxygen intermediates. Mutagenesis 2010, 25, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Long, Y.; Huang, J.J.; Xia, J.X. Molecular mechanisms for coping with Al toxicity in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattiello, L.; Begcy, K.; da Silva, F.R.; Jorge, R.A.; Menossi, M. Transcriptome analysis highlights changes in the leaves of maize plants cultivated in acidic soil containing toxic levels of Al3+. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 8107–8116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ezaki, B.; Katsuhara, M.; Ahn, S.J.; Ryan, P.R.; Delhaize, E.; Matsumoto, H. A wheat gene encoding an aluminum-activated malate transporter. Plant J. 2004, 37, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevenstuk, T.; Romano, A. Aluminium speciation and internal detoxification mechanisms in plants: Where do we stand? Metallomics 2013, 5, 1584–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñeros, M.A.; Cançado, G.M.A.; Maron, L.G.; Lyi, S.M.; Menossi, M.; Kochian, L.V. Not all ALMT1-type transporters mediate aluminum-activated organic acid responses: The case of ZmALMT1—An anion-selective transporter. Plant J. 2008, 53, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, B.D.; Ryan, P.R.; Richardson, A.E.; Tyerman, S.D.; Ramesh, S.; Hebb, D.M.; Howitt, S.M.; Delhaize, E. HvALMT1 from barley is involved in the transport of organic anions. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 1455–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhaes, J.V.; Liu, J.; Guimarães, C.T.; Lana, U.G.P.; Alves, V.M.C.; Wang, Y.-H.; Schaffert, R.E.; Hoekenga, O.A.; Piñeros, M.A.; Shaff, J.E.; et al. A gene in the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family confers aluminum tolerance in sorghum. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, J.; Yamaji, N.; Wang, H.; Mitani, N.; Murata, Y.; Sato, K.; Katsuhara, M.; Takeda, K.; Ma, J.F. An aluminum-activated citrate transporter in barley. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007, 48, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.P.; Magalhaes, J.V.; Shaff, J.; Kochian, L.V. Aluminum-activated citrate and malate transporters from the MATE and ALMT families function independently to confer Arabidopsis aluminum tolerance. Plant J. 2009, 57, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, P.R.; Raman, H.; Gupta, S.; Horst, W.J.; Delhaize, E. A second mechanism for aluminum resistance in wheat relies on the constitutive efflux of citrate from roots. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokosho, K.; Yamaji, N.; Ma, J.F. Isolation and characterisation of two MATE genes in rye. Funct. Plant Biol. 2010, 37, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokosho, K.; Yamaji, N.; Ma, J.F. An Al-inducible MATE gene is involved in external detoxification of Al in rice. Plant J. 2011, 68, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, L.G.; Piñeros, M.A.; Guimarães, C.T.; Magalhaes, J.V.; Pleiman, J.K.; Mao, C.; Shaff, J.; Belicuas, S.N.J.; Kochian, L.V. Two functionally distinct members of the MATE (multi-drug and toxic compound extrusion) family of transporters potentially underlie two major aluminum tolerance QTLs in maize. Plant J. 2010, 61, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, P.B.; Geisler, M.J.B.; Jones, C.A.; Williams, K.M.; Cancel, J.D. ALS3 encodes a phloem-localized ABC transporter-like protein that is required for aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2005, 41, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, P.B.; Cancel, J.; Rounds, M.; Ochoa, V. Arabidopsis ALS1 encodes a root tip and stele localized half type ABC transporter required for root growth in an aluminum toxic environment. Planta 2007, 225, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.F.; Yamaji, N.; Mitani, N.; Yano, M.; Nagamura, Y.; Ma, J.F. A Bacterial-Type ABC transporter is involved in aluminum tolerance in rice. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famoso, A.N.; Zhao, K.; Clark, R.T.; Tung, C.-W.; Wright, M.H.; Bustamante, C.; Kochian, L.V.; McCouch, S.R. Genetic architecture of aluminum tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa) determined through genome-wide association analysis and QTL mapping. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Yamaji, N.; Kasai, T.; Ma, J.F. Plasma membrane-localized transporter for aluminum in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18381–18385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.Y.; Liu, J.; Dong, D.; Jia, X.; McCouch, S.R.; Kochian, L.V. Natural variation underlies alterations in Nramp aluminum transporter (NRAT1) expression and function that play a key role in rice aluminum tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 6503–6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.Z.; Wang, Z.Q.; Yokosho, K.; Ding, B.; Fan, W.; Gong, Q.Q.; Li, G.X.; Wu, Y.R.; Yang, J.L.; Ma, J.F.; et al. Transcription factor WRKY22 promotes aluminum tolerance via activation of OsFRDL4 expression and enhancement of citrate secretion in rice (Oryza sativa). New Phytol. 2018, 219, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, B.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Qaseem, M.F.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Wu, A.M. Physiological, biochemical, and transcriptomic responses of Neolamarckia cadamba to aluminum stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Hu, Y.; Chen, H.; Tan, J.; Xu, H.; Li, P.; Wu, D.; Jia, J.; Yang, Z. Transcriptome analysis of response to aluminum stress in Pinus massoniana. Forests 2022, 13, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Piñeros, M.A.; Li, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Murphy, A.S.; Kochian, L.V.; Liu, D. An Arabidopsis ABC Transporter mediates phosphate deficiency-induced remodeling of root architecture by modulating iron homeostasis in roots. Mol. Plant 2016, 10, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.X.; Zhang, J.; Wan, Z.Y.; Huang, S.X.; Di, H.C.; He, Y.; Jin, S.H. Physiological and transcriptome analyses provide new insights into the mechanism mediating the enhanced tolerance of melatonin-treated rhododendron plants to heat stress. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 2397–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Su, H.G.; Peng, X.R.; Bi, H.C.; Qiu, M.H. An updated review of the genus Rhododendron since 2010: Traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Phytochemistry 2023, 217, 113899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Skidmore, A.K.; Wang, T.; Huang, J.; Ma, K.; Groen, T.A. Rhododendron diversity patterns and priority conservation areas in China. Divers. Distrib. 2017, 23, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.H.; Zhang, K.L. Progresses and prospects of the research on soil erosion in Karst area of Southwest China. Adv. Earth Sci. 2018, 33, 1130–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.X.; Lei, Y.S.; Huang, S.X.; Zhang, J.; Wan, Z.Y.; Zhu, X.T.; Jin, S.H. Combined de novo transcriptomic and physiological analyses reveal RyALS3-mediated aluminum tolerance in Rhododendron yunnanense Franch. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 951003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Lu, K.; Gong, Z.; Weng, Z.; Shu, P.; Chen, Y.; Jin, S.; Li, X. Differences in gas exchange, chlorophyll fluorescence, and modulated reflection of light at 820 nm between two Rhododendron cultivars under aluminum stress conditions. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cai, Y.F.; Zhang, M.C.; Du, G.H.; Wang, J.H. Selection and evaluation of candidate reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in aboveground tissues and drought conditions in Rhododendron Delavayi. Front Genet. 2022, 13, 876482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.F.; Yu, B.; Huang, L.L.; Sun, Y.B. Screening and validation of reference genes of Camellia azalea by quantitative real-time PCR. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 2020, 47, 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z.; Li, X.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jin, S. Comprehensive genomic survey, structural classification, and expression analysis of WRKY transcription factor family in Rhododendron simsii. Plants 2022, 11, 2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H. Discovery and development of natural product-derived chemotherapeutic agents based on a medicinal chemistry approach. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 500–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, X. Poisonous delicacy: Market-oriented surveys of the consumption of Rhododendron flowers in Yunnan, China. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 265, 113320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampp, R.; Schnabl, H. Effect of aluminium ions on 14CO2 -fixation and membrane system of isolated spinach chloroplasts. Z. Pflanzenphysiol. 1975, 76, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzykowska, M.; Suorsa, M.; Semchonok, D.A.; Tikkanen, M.; Boekema, E.J.; Aro, E.M.; Jansson, S. The light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b binding proteins Lhcb1 and Lhcb2 play complementary roles during state transitions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 3646–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, T.; Wan, H.; Chen, J.; He, S.; Lujin, C.; Xia, M.; Wang, S.; Dai, X.; Zeng, C. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the chlorophyll a/b binding protein gene family in oilseed (Brassica napus L.) under salt stress conditions. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, L.; Zheng, L. Lignins: Biosynthesis and biological functions in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, R.; Pang, Y.; Qiu, X.; Yang, D. Microwave-assisted synthesis of high carboxyl content of lignin for enhancing adsorption of lead. Colloids Surf. A 2018, 553, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Riaz, M.; Wu, X.; Du, C.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, C. Ameliorative effects of boron on aluminum induced variations of cell wall cellulose and pectin components in trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliate (L.) Raf.) rootstock. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 240, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Ling, F.; Xing, A.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Deng, X.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Hu, Z.; et al. Lignin synthesis mediated by CCoAOMT enzymes is required for the tolerance against excess Cu in Oryza sativa. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 175, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Qiua, Y.; Wang, A. Integration of metabolomics and transcriptomics reveals the regulation mechanism of the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway in insect resistance traits in Solanum habrochaites. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhad277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, X.; Feng, H.; Zhu, Q.; Sun, J.; Li, Y. Characterization of the Gh4CL gene family reveals a role of Gh4CL7 in drought tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Ralph, J.; Akiyama, T.; Flint, H.; Phillips, L.; Torr, K.; Nanayakkara, B.; TeKiri, L. Exploring lignification in conifers by silencing hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA: Shikimate hydroxycinnamoyltransferase in Pinus radiata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 11856–11861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, E.S.; Yoo, J.H.; Lee, J.G.; Kim, H.Y.; Hwang, I.S.; Heo, K.; Kim, J.K.; Lim, J.D.; Sacks, E.J.; Yu, C.Y. Antisense-overexpression of the MsCOMT gene induces changes in lignin and total phenol contents in transgenic tobacco plants. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 1979–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, P.; Zhang, K.; Yang, C. BpNAC012 positively regulates abiotic stress responses and secondary sall biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2019, 179, 700–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Song, M.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Xue, H.; Dai, H.; Zhang, Z. MdMYB46 could enhance salt and osmotic stress tolerance in apple by directly activating stress-responsive signals. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 2341–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DíAz, J.; Bernal, A.; Pomar, F.; Merino, F. Induction of shikimate dehydrogenase and peroxidase in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) seedlings in response to copper stress and its relation to lignification. Plant Sci. 2001, 161, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Feng, Y.; Yu, S.; Fan, Z.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Yin, H. The flavonoid biosynthesis network in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, W.; Han, Y.; Wang, G.; Jin, S. Sexual differences in gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence of Torreya grandis under drought stress. Trees 2021, 36, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chee, C.W.; Goh, C.J. ‘Photoinhibition’ of Heliconia under natural tropical conditions: The importance of leaf orientation for light interception and leaf temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 19, 1238–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorska, B.; Romanowska, E. Photoinhibition and D1 protein degradation in mesophyll and agranal bundle sheath thylakoids of maize. Funct. Plant Biol. 2007, 34, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goltsev, V.N.; Kalaji, H.M.; Paunov, M.; Bąba, W.; Horaczek, T.; Mojski, J.; Kociel, H.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Variable chlorophyll fluorescence and its use for assessing physiological condition of plant photosynthetic apparatus. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 63, 869–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, P.; Baczewska-Dąbrowska, A.H.; Kalaji, H.M.; Goltsev, V.; Paunov, M.; Rapacz, M.; Wójcik-Jagła, M.; Pawluśkiewicz, B.; Bąba, W.; Brestic, M. Exploration of chlorophyll a fluorescence and plant gas exchange parameters as indicators of drought tolerance in Perennial Ryegrass. Sensors 2019, 19, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Escalona, J.M.; Evain, S.; Gulías, J.; Moya, I.; Osmond, C.B.; Medrano, H. Steady-state chlorophyll fluorescence (Fs) measurements as a tool to follow variations of net CO2 assimilation and stomatal conductance during water-stress in C3 plants. Physiol. Plant. 2002, 114, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalink, H.; van der Schoor, R.; Frandas, A.; van Pijlen, J.G.; Bino, R.J. Chlorophyll fluorescence of Brassica oleracea seeds as a non-destructive marker for seed maturity and seed performance. Seed Sci. Res. 2008, 8, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schansker, G.; Tóth, S.Z.; Strasser, R.J. Methylviologen and dibromothymoquinone treatments of pea leaves reveal the role of photosystem I in the Chl a fluorescence rise OJIP. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1706, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Gao, J.; Li, P.; Goltsev, V.; Ma, F. Thermotolerance of apple tree leaves probed by chlorophyll a fluorescence and modulated 820nm reflection during seasonal shift. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2015, 152, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, G.; Gao, H.; Zhang, L.; Yang, C.; Liu, P.; Meng, Q. Characterization of photosynthetic performance during senescence in stay-green and quick-leaf-senescence Zea mays L. inbred lines. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Lu, Y.; Goltsev, V.; Strasser, R.J.; Kalaji, H.M.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Qiang, S. Comparative effect of tenuazonic acid, diuron, bentazone, dibromothymoquinone and methyl viologen on the kinetics of Chl a fluorescence rise OJIP and the MR820 signal. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 156, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazár, D. Chlorophyll a fluorescence induction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1412, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Kan, X.; Chen, J.; Hua, H.; Li, Y.; Ren, J.; Feng, K.; Liu, H.; Deng, D.; Yin, Z. Drought-induced changes in photosynthetic electron transport in maize probed by prompt fluorescence, delayed fluorescence, P700 and cyclic electron flow signals. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 158, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oukarroum, A.; Goltsev, V.; Strasser, J.R. Temperature effects on pea plants probed by simultaneous measurements of the kinetics of prompt fluorescence, delayed fluorescence and modulated 820 nm reflection. PLoS ONE 2018, 8, e59433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.