Abstract

Floral induction in late-maturing litchi is vulnerable to warm, humid winters with insufficient chilling. The late cultivar ‘Ziniangxi’ was evaluated during January–February 2024 in an experimental orchard in Hainan, China, when chilling accumulation was very low, with only seven days having a mean air temperature ≤ 15 °C. Under this marginal-chill context, the effects of plant growth regulator (PGR) applications on bud fate were assessed using six single-agent and thirteen composite PGR–nutrient treatments plus a water control, applied as four foliar sprays during floral induction. In the untreated control, the final flowering proportion of tagged shoots was 0.33 in the single-agent trial and 0.05 in the composite trial. In contrast, ABA (3.33 mg L−1) increased flowering to 0.53, and ethephon- or brassinolide-based applications to 0.40–0.47. The most effective composite formulations raised flowering further to 0.50–0.63. These composite applications also increased leaf starch from about 4 mg g−1 FW in the control to approximately 8–9 mg g−1 FW (), whereas sucrose concentrations showed only small differences among treatments. Across trials, shoots that became floral consistently exhibited higher leaf starch than vegetative shoots. Gene-expression analyses indicated that floral buds had higher transcript abundance of LcFUL and lower transcript levels of LcFLC and other floral repressors than vegetative buds, consistent with their assignment to floral versus vegetative categories. Overall, the results suggest that appropriately timed ethephon–ABA-based PGR programs, supplemented with BR or 6-BA and nutrients, can partially improve floral induction in ‘Ziniangxi’ under warm, low-chill winters and provide a basis for designing PGR strategies for late litchi cultivars facing insufficient winter chilling.

1. Introduction

Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) is a major subtropical fruit crop whose yield and economic value depend heavily on regular and synchronous flowering [1,2]. Floral induction in litchi requires exposure to sufficiently low temperatures during autumn and winter, and when chilling accumulation is inadequate, terminal buds often fail to enter a stable floral pathway, resulting in weak or highly variable flowering and large fluctuations in yield [3,4]. Late-maturing cultivars are particularly vulnerable because their chilling requirement is relatively high and their exposure to low temperatures often overlaps with warm spells and rainfall events [5]. In South China and similar regions, warm, humid winters with low chilling have become more frequent in recent years, increasing the risk of flowering failure in late litchi cultivars and posing a growing challenge for orchard management.

Floral transition in tree crops is regulated by the interplay between environmental cues, carbohydrate supply, hormones and genetic regulators at the shoot apex [6,7]. Chilling is integrated with carbon status and hormone balances to determine whether a bud proceeds to floral initiation or resumes vegetative growth [8,9,10]. At the molecular level, seasonal control of meristem fate involves an integrated network in which FT-like signals produced in leaves act with FD in the apex to promote floral identity, while TFL1-like factors maintain indeterminacy and delay transition [11,12]. FLC-like repressors constrain flowering competence and are alleviated by sufficient chill, whereas downstream integrators such as SOC1, LFY and AP1/FUL-like genes commit the apex to reproductive development [13,14,15,16]. Previous work in woody perennials has shown that changes in starch and soluble sugar accumulation around the apex, together with altered expression of floral-promoting and floral-repressing genes such as FUL and FLC, are associated with differences in flowering behaviour under contrasting thermal applications [17,18]. Within this framework, upregulation of FUL is expected to accompany successful transition, whereas sustained FLC expression under insufficient chilling can cap the response to agronomic or chemical cues [15,16], providing a rationale for measuring FUL and FLC alongside carbohydrate traits in warm and humid winters. However, in late-maturing litchi cultivars exposed to genuinely warm–humid winters with marginal chill, it remains unclear how these regulatory layers respond in the field and how they are modified by plant growth regulator treatments.

To mitigate the impact of warm winters, various plant growth regulators (PGRs) have been used in litchi orchards to manipulate bud rest, canopy vigour and floral initiation [19,20]. Ethephon and other ethylene-releasing compounds [21,22] can help enforce bud rest and reduce vegetative flushes, abscisic acid (ABA) [23] is associated with bud maturation and stress readiness, growth retardants such as paclobutrazol and uniconazole [24] suppress excessive shoot elongation, and brassinosteroids (BR) [25] and cytokinins [26] can enhance meristem activity and inflorescence development. Several studies have reported that individual PGRs or simple combinations improve flowering and inflorescence quality in certain cultivars, often under winters with moderate or adequate chilling [27,28]. Nevertheless, most previous work, although conducted across various cultivars, has been carried out under winters with moderate or adequate chilling and has rarely tested composite PGR–nutrient regimes in genuinely warm, low-chill environments [19,29]. In addition, for late-maturing litchi cultivars under warm, low-chill winters, field data that simultaneously link flowering responses with carbohydrate status and the expression of key flowering-related genes are still limited.

Critical knowledge gaps therefore remain regarding how integrated PGR–nutrient programs perform under warm–humid, marginal-chill winters in late-maturing cultivars, and how such programs are associated with changes in leaf carbohydrates and in the expression of FUL, FLC and related regulators in buds. The late cultivar ‘Ziniangxi’ is known for its strong chilling requirement and high propensity for flowering failure and leafy admixture when winters are too warm, making it a sensitive and practically relevant model for evaluating chemical regulation of floral transition under insufficient chilling [1,2].

In this study, ‘Ziniangxi’ trees at an experimental orchard exposed to a warm–humid winter in 2024 with only seven chilling days provided a well-documented marginal-chill context. Climatic conditions, bud fate and associated leaf carbohydrate profiles in flowering and vegetative shoots were first quantified. A panel of single-agent PGR treatments and a broader set of composite PGR–nutrient applications were then applied to assess their ability to shift bud fate from vegetative to flowering under these conditions, and leaf starch and sucrose were analysed together with the expression of selected flowering-related genes, including FUL and FLC. The present work aimed to (i) characterise floral instability and bud fate in ‘Ziniangxi’ under a quantified warm–humid, marginal-chill winter; (ii) identify single and composite PGR applications that improve flowering proportion and inflorescence purity under these conditions; and (iii) relate flowering outcomes to changes in carbohydrate status and flowering-gene expression, thereby providing a field-based framework for designing PGR strategies for late litchi cultivars facing insufficient winter chilling.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The materials for this study were collected in the orchard of the Institute of Fruit Tree Research, Hainan Academy of Agricultural Sciences using late-cultivar ‘Ziniangxi’ trees of uniform vigor. Floral induction sprays were timed to the critical induction window, when terminal buds started growing and shoot elongation was less than 5 cm. Uniform shoots on different trees were selected to minimize vigor-related bias.

2.2. Climate Conditions During the Experimental Period

Weather data (air temperature and relative humidity) during the experimental period were obtained from an automatic meteorological station located within the orchard.

Chilling accumulation was expressed as the number of days with mean daily air temperature ≤ 15 °C. Between 1 January and 26 February 2024, only seven chilling days occurred: five days between 23 and 28 January 2024 and two days between 9 and 10 February 2024. Thus, by the time of the first PGR application on 26 January 2024, only five chilling days had accumulated, and a total of seven chilling days had accumulated by the end of the observation period. These conditions were insufficient to satisfy the full chilling requirement of late-maturing litchi cultivars and are representative of marginal-chill, warm–humid winters in this region.

2.3. Single-Agent Plant Growth Regulator Applications

Field trials were conducted under orchard conditions at the experimental station of the Hainan Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Yongfa Town, Chengmai County, Hainan Province, China, during January–February 2024. A set of plant growth regulators (PGRs) including Ethephon, abscisic acid, cytokinins, and Oxyfluorfen was evaluated for their ability to promote the vegetative-to-reproductive transition (Table 1). In total, six single-PGR treatments were tested, and water sprays served as the untreated control (CK). Because the number of trees that could be dedicated to PGR treatments was limited, a split-canopy design was adopted in order to maintain three replicates per treatment while using trees with highly uniform growth. In each selected tree, the canopy was visually divided into three contiguous sectors of approximately equal area, following the main azimuthal orientations (e.g., east-, south-, and west-facing) at comparable height and distance from the trunk. Each sector served as one experimental unit. For each PGR treatment, three replicate sectors were established by assigning one sector on each of three different trees, with sectors placed on different canopy orientations as far as possible to account for variation in light and wind exposure. Across all treatments, a total of seven uniform trees were used.

Table 1.

Single agent plant growth regulator (PGR) treatments and concentrations applied during warm winter conditions in early 2024.

Foliar sprays were applied to runoff with a hand-held sprayer at the designated concentrations, and each treatment was administered four times (26 and 30 January and 3 and 5 February 2024) within the floral-induction window. Within each treated sector, 6–7 shoots of similar vigor were tagged for repeated observations. Tagged shoots were selected away from the boundaries between adjacent treated sectors to avoid potential edge effects and were chosen from branches with comparable growth status. This resulted in approximately 20 tagged shoots per treatment distributed across three trees. The morphological status of each tagged shoot was recorded as baseline (pre-treatment) and 2–3 days after each application, including bud status, presence of inflorescences (presence of terminal inflorescences), and vegetative stage. At each observation, shoots were classified according to apex morphology as vegetative (bud swelling or leafy flush without a visible inflorescence) or floral (visible inflorescence primordia or emerging inflorescence). Final flowering status was assessed when inflorescences had elongated to approximately 2–3 cm (white millet stage). The four application dates were chosen according to prevailing weather conditions and visible tree responses during the induction period. Leaf samples for carbohydrate and flowering-related gene analyses were collected on 2 and 7 February 2024 to capture treatment-induced changes during floral induction. The primary outcome was the proportion of floral to vegetative stage per treatment and observation date, calculated as the number of tagged shoots in floral stage divided by the total number of tagged terminal shoots.

2.4. Composite Plant Growth Regulators and Key Nutrient Appications

To assess potential synergistic effects under warm–humid winter conditions, composite foliar sprays were formulated by combining PGRs (for example, ethephon, uniconazole, cytokinins, gibberellins, abscisic acid, brassinosteroids) with key nutrients and elements relevant to source–sink balance (for example, phosphorus and potassium sources and selected micronutrients) (Table 2). Applications followed the same phenological timing, tree selection, canopy division, randomization, and tagging scheme as described in Section 2.3. In total, thirteen composite PGR–nutrient applications were tested, with water sprays serving as the control (CK).

Table 2.

Composite PGR treatments and concentrations applied during warm winter conditions in early 2024.

Foliar sprays were applied at the designated concentrations to runoff on the same application dates and within the same floral-induction window as described above. Within each treated sector, 6–7 shoots of similar vigor were tagged and monitored as described for the single-PGR trial, and pre- and post-treatment observations were recorded as above. Treatments were compared to identify composite formulas that most effectively increased the flowering proportion and reduced vegetative shoots.

2.5. Quantification of Starch and Sucrose

Terminal buds, leaves, and terminal shoot samples were collected on 2 and 7 February 2024 to determine carbohydrate levels to capture treatment-induced changes during floral induction. For each treatment and sampling date, four biological replicates were taken, each consisted of material pooled from several tagged terminal shoots. Terminal buds were excised individually from the shoot apex, and a separate stem segment of approximately 2 cm in length was cut from the internode immediately below each sampled terminal bud to represent the terminal shoot sample. Leaf samples consisted of fully expanded leaves on the current-season flush at the 4th–6th leaf position below the terminal bud on the same tagged shoots. Starch content was measured using the Solarbio BC0700 assay kit (Solarbio Science Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Leaf sucrose content was measured using the Solarbio BC2465 assay kit (Solarbio Science Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), also according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Carbohydrate concentrations were expressed on a fresh-weight basis (mg g−1 FW).

2.6. qPCR Analysis of Flowering-Related Genes

Terminal buds for flowering-related gene analyses were collected on 2 and 7 February 2024 to capture treatment-induced changes during floral induction. Total RNA was extracted from frozen leaf tissue using standard protocols suitable for phenolic-rich tissues with a Quick RNA isolation kit (Huayueyang Biotech Co. Ltd., Beijing, China), followed by DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg total RNA using a reverse transcription kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Yeasen Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed for flowering-related genes, including LcFLC, LcAP2, LcTFL1-1, LcLFY, LcFD, and LcFUL, for primer design logic and assay conditions [30]. qPCR reactions were carried out using the Hieff UNICON® ColorGPS qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Yeasen Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the annealing temperature set to 55 °C. Gene-specific primer sequences are listed in (Table 3), and amplification efficiency for each primer pair was verified from standard curves generated from serial dilutions of pooled cDNA. For each sample, four biological replicates were analyzed, each with three technical replicates. Expression levels were normalized to the Cp values of the reference gene LcActin (HQ615689.1). For each sample, was calculated as , and relative transcript abundance was then obtained using the method, where was calculated by subtracting the mean of the calibrator sample. Depending on the analysis, either vegetative buds or the water control (CK) served as the calibrator, as specified in the corresponding figure legends. The PCR reactions and measurements were carried out using a LightCycler® 480 II system (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Rotkreuz, Switzerland).

Table 3.

Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR expression.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The experiment followed a split-canopy randomized complete block design, with tree as block and canopy sector as the experimental unit for treatment comparisons. Unless otherwise stated, data are presented as means ± standard error of four biological replicates ().

For comparisons between two categories (e.g., floral vs. vegetative buds or shoots), differences were evaluated using Student’s t-test. For comparisons among more than two treatments (single and composite PGR applications), data were analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and, where significant treatment effects were detected, means were separated using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test at . All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Climate Conditions and Carbohydrate Profiles Associated with Bud Fate in ‘Ziniangxi’

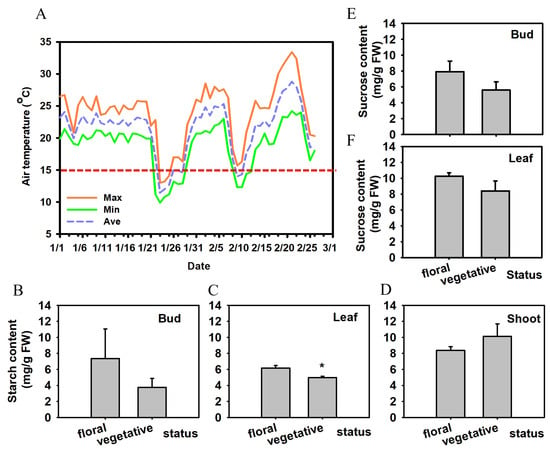

Weather conditions during the experimental period, as recorded by the automatic weather station at the experimental base, confirmed that ‘Ziniangxi’ trees experienced a warm and humid winter with very limited chilling (Section 2.2). Daily mean air temperature remained above 18 °C throughout January–February 2024, with an overall mean of 21.38 °C, and only seven days with mean temperature ≤ 15 °C (Figure 1A). Mean daily relative humidity exceeded 90%, indicating persistently moist conditions. These data show that the trial was conducted under a typical marginal-chill, warm–humid winter.

Figure 1.

Climate conditions and carbohydrate profiles associated with bud fate in ‘Ziniangxi’. (A) Daily air temperature in Chengmai, Hainan (January–February 2024); the red dashed line marks 15 °C, and the season featured short, late cold spells with prolonged rainy, overcast conditions. (B–D) Starch content in terminal buds, leaves, and terminal shoots, comparing shoots that proceeded to floral transition (Floral) versus those that reverted to vegetative growth (Vegetative). (E,F) Sucrose content in buds and leaves for the same stages as described for B–D. “Floral” denotes buds that developed into inflorescences, whereas “vegetative” denotes buds that reverted to leafy (vegetative) growth. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Asterisks indicate significant differences (* p < 0.05; Student’s t-test, n = 4).

To evaluate how bud fate was associated with carbon status under these conditions, buds on tagged shoots were classified into two categories. In the following analyses, “floral” and “vegetative” refer to two alternative fates of buds: floral buds proceeded to inflorescence development, whereas vegetative buds reverted to leafy growth after the induction period. Carbohydrate contents in buds, leaves, and current-season shoots differed between these two bud fates (Figure 1B–F). In buds, starch content tended to be higher in floral than in vegetative buds (Figure 1B), although this difference was not statistically significant (). In contrast, leaves subtending floral buds contained significantly more starch than leaves associated with vegetative buds (; Figure 1C), whereas current-season shoots showed slightly higher starch in vegetative than in floral shoots (Figure 1D). Because sucrose can function both as a nutrient and as a signaling molecule during floral transition, sucrose levels were profiled in both buds and leaves. Sucrose showed a similar but weaker trend: bud sucrose content was numerically higher in floral than in vegetative buds (Figure 1E), and leaf sucrose was also higher in floral than in vegetative shoots (Figure 1F); however, these sucrose differences were not significant at . Together, these patterns may suggest that leaf starch, rather than sucrose, was more strongly associated with floral buds under the warm–humid conditions of this study.

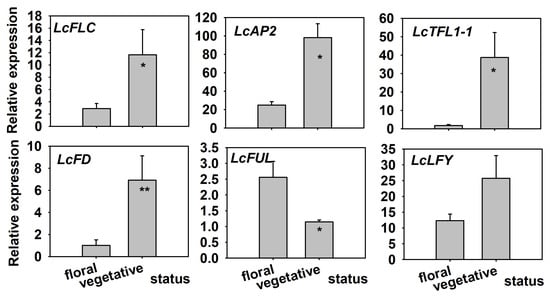

Expression of flowering-related genes also differed consistently between floral and vegetative buds (Figure 2). The floral repressor FLC showed markedly higher transcript abundance in vegetative than in floral buds (approximately three- to fourfold; ), and similar patterns were observed for LcAP2, LcTFL1-1, LcFD, and LcLFY, which all exhibited significantly greater expression in vegetative buds ( or , as indicated in Figure 2). In contrast, the floral integrator LcFUL was significantly upregulated in floral buds, with transcript levels roughly two- to threefold higher than in vegetative buds ().

Figure 2.

Relative expression of key floral regulators (LcFLC, LcAP2, LcTFL1-1, LcFD, LcLFY, LcFUL) in terminal buds during floral transition and vegetative reversion. Expression values were normalized to LcActin and expressed as fold change relative to vegetative buds (). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Asterisks indicate significant differences (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; Student’s t-test, n = 4).

3.2. Single-Agent Effects on ‘Ziniangxi’ Bud Fate in Warm, Humid Winters

Under the warm–humid, marginal-chill winter described above, the late cultivar ‘Ziniangxi’ was used as plant material because it has a relatively strong chilling requirement and is prone to flowering failure and leafy admixture within developing inflorescences. These characteristics make ‘Ziniangxi’ a sensitive and practical model for evaluating chemical regulation of floral transition under insufficient chilling. Across the single PGR applications, tagged terminal shoots were at a uniform early flush stage at baseline (Pre-treatment), with newly emerged vegetative shoots approximately 2–3 cm long and bearing expanding leaves, and then displayed two typical developmental trajectories (Figure 3). In the “successful” trajectory, buds that were vegetative at the baseline stage (Pre-treatment) progressed, after repeated PGR applications (Post-T1 and Post-T2), to clear inflorescence development. In the “unsuccessful” trajectory, buds swelled but remained on a vegetative path, producing leafy flushes and mixed rather than pure inflorescence. These contrasting outcomes illustrate the criteria used to classify bud fate as floral or vegetative in subsequent quantitative analyses.

Figure 3.

Representative shoot outcomes of ‘Ziniangxi’ under warm and humid conditions. Top row: successful floral transition. Bottom row: vegetative outcome (unsuccessful). Columns show Baseline (pre-treatment; early vegetative flush stage with terminal shoots approximately 2–3 cm long and expanding leaves), Post-T1 (30 January 2024; 3 days after the second application), and Post-T2 (5 February 2024; 2 days after the fourth application).

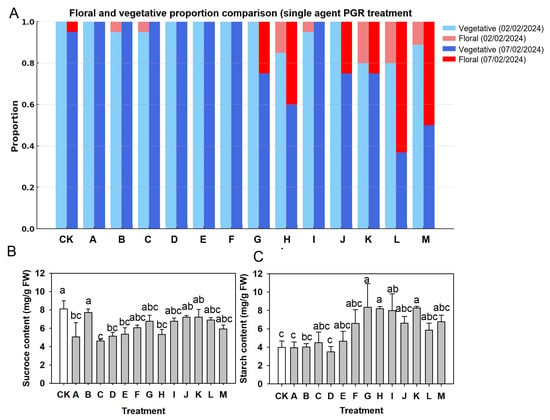

For the single-agent trial, six PGR treatments (6-BA, ABA, BR, ETH0.2, ETH0.8, and Oxy) and a water control (CK) were imposed (Table 1). At the population level, the proportions of floral and vegetative shoots under these treatments are summarized in Figure 4A for two assessment dates, 2 February (after the second application) and 7 February (after the fourth application). On 2 February, flowering remained low across treatments, ranging from 0.00 to 0.27. The control (CK) and the BR and 6-BA treatments each had flowering proportions of 0.27, ETH0.2 (26.67 mg/L) and ETH0.8 (80.00 mg/L) gave 0.20, ABA gave 0.13, and Oxy showed no floral shoots (0.00). By 7 February, floral proportions had increased in all treatments. The control reached 0.33, whereas ETH0.2, ETH0.8, BR, and 6-BA each reached 0.40–0.47, and ABA showed the highest flowering proportion at 0.53. In contrast, Oxy remained low at 0.07, with most shoots still classified as vegetative (0.93).

Figure 4.

Floral outcomes and leaf carbohydrates after single-agent PGR treatments in ‘Ziniangxi’. (A) Proportion of shoots in vegetative versus floral states across six single treatments (6-BA, ABA, BR, ethephon 26.67 mg/L, ethephon 80 mg/L, oxyfluorfen) and the water control (CK). Colors denote phenological stage and observation date: vegetative on 2 February (light blue), floral on 2 February (light red), vegetative on 7 February (dark blue), floral on 7 February (dark red). (B) Leaf sucrose concentrations after single-agent PGR treatments. (C) Leaf starch concentrations after single-agent PGR treatments. Bars above the columns indicate standard error of means; Same letters above columns denote no significant differences between treatments according to Tukey (HSD) test at .

Single PGR treatments had limited effects on leaf sucrose but did influence leaf starch content (Figure 4B,C). On 7 February, leaf sucrose concentrations ranged from about 18 to 25 mg g−1 FW across treatments, and no clear treatment effect was detected; all single PGRs and the water control (CK) showed comparable sucrose levels (Figure 4B). In contrast, leaf starch content varied markedly among treatments (Figure 4C). BR produced the highest starch content (around 9 mg g−1 FW), which was significantly higher than both CK (approximately 4 mg g−1 FW) and 6-BA (about 5 mg g−1 FW). ETH0.2, ETH0.8, ABA and Oxy gave intermediate starch levels that did not differ significantly from either BR or CK, as indicated by the letter groupings in Figure 4C.

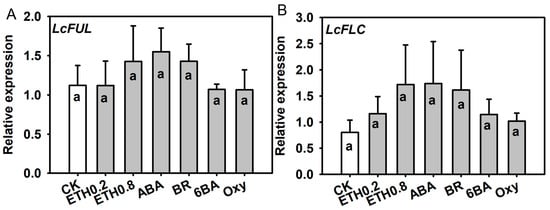

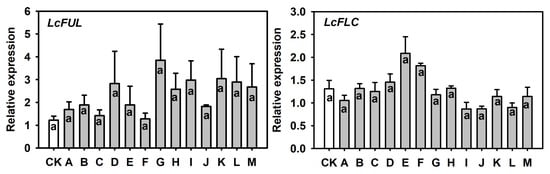

Based on the relative expression results obtained in the comparison between floral and vegetative buds (Figure 2), and to examine whether single PGR treatments altered the expression of flowering-related genes, we quantified the transcript levels of LcFUL and LcFLC in buds treated with PGR and the control (Figure 5). Relative LcFUL expression showed a slight numerical increase in PGR-treated buds compared with the control (means approximately 1.1–1.5 vs. 1.0 on a relative scale), and LcFLC also tended to be numerically higher in PGR-treated buds than in the control (means around 1.1–1.8 vs. 0.9). However, for both genes, one-way ANOVA detected no significant differences among treatments ().

Figure 5.

Relative expression of LcFUL and LcFLC in terminal buds of ‘Ziniangxi’ after single-agent PGR treatments. (A) Relative expression of LcFUL. (B) Relative expression of LcFLC. Expression values were normalized to LcActin and expressed as fold change relative to CK (). Bars represent mean ± SE (). Same letters above columns denote no significant differences between treatments according to Tukey (HSD) test at .

3.3. Composite PGRs Effects on ‘Ziniangxi’ Bud Fate in Warm, Humid Winters

To further probe chemical regulation of floral transition under warm–humid, marginal-chill conditions, thirteen composite PGR–nutrient applications were tested together with a water control (CK) (Table 2). These composite applications combined ethephon with different growth regulators (e.g., uniconazole, DA-6, 6-BA, BR), carbohydrates including glucose, trehalose and sucrose, and nutrient components such as KH2PO4, and boric acid in various formulations coded as groups A–M.

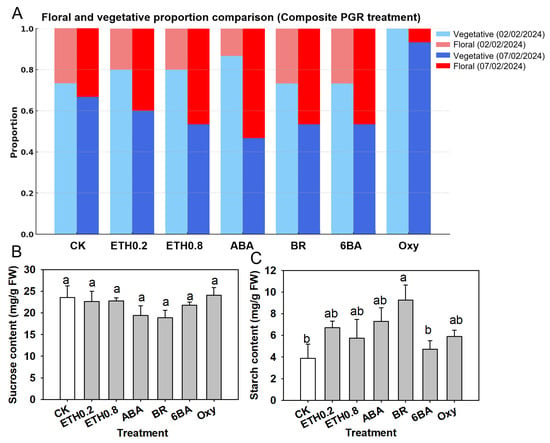

Composite treatments generated a wider range of flowering rate responses than single-agent PGRs (Figure 6A). On 2 February, flowering rate remained scarce in most groups: treatments A, D, E, F, G, J and CK showed no floral shoots, whereas treatment B, C and I reached only 0.05, M reached 0.11, and H, K and L reached 0.15 and 0.20, respectively. By 7 February, flowering proportions had diverged more clearly among treatments. Groups A to F and I still had no floral shoots, and the control reached only 0.05, indicating that almost all tagged shoots remained vegetative. In contrast, several composite applications shifted a substantial fraction of shoots into the floral category: group G reached 0.25, H, J and K each reached 0.25 to 0.40, treatment M reached 0.50, and treatment L reached the highest flowering proportion of 0.63. Thus, only a subset of composite PGR–nutrient formulations, particularly groups G (Ethephon 26.67 mg/L + Uniconazole 33.33 mg/L + ABA 0.06 mg/L + Oxyfluorfen 1.80 mg/L), H (DA-6 0.40 g/L + KH2PO4 1.00 g/L), J (6-BA 13.33 mg/L + Triacontanol 0.67 mg/L + Boric acid 0.67 g/L + KH2PO4 1.00 g/L), K (BR 0.05 mg/L + ABA 0.06 mg/L + KH2PO4 1.00 g/L+ Boric acid 0.67 mg/L), L (BR 0.05 mg/L + ABA 0.06 mg/L + KH2PO4 1.00 g/L) and M (6-BA 13.33 mg/L + Triacontanol 0.67 mg/L + KH2PO4 1.00 g/L), noticeably redirected bud fate from vegetative to floral under the warm–humid, marginal-chill conditions of this study.

Figure 6.

Floral/vegetative outcomes and leaf carbohydrate responses to composite PGR treatments in ‘Ziniangxi’. (A) Proportion of shoots in vegetative versus floral states across 13 composite treatments and the water control (CK). Colors denote phenological stage and observation date: vegetative on 2 February (light blue), floral on 2 February (light red), vegetative on 7 February (dark blue), floral on 7 February (dark red). (B) Leaf sucrose concentrations after the composite PGR treatments. (C) Leaf starch concentrations after the composite treatments. Bars above the columns indicate standard error of means; Same letters above columns denote no significant differences between treatments according to Tukey (HSD) test at .

Composite PGR applications also modified leaf carbohydrate status (Figure 6B,C). On 2 February, leaf sucrose concentrations ranged from about 4 to 8 mg g−1 FW. The control and group B showed the highest sucrose contents, close to 8 mg g−1 FW, whereas groups C was at the lower end, around 4 mg g−1 FW. The letter groupings in Figure 6B indicate that sucrose in several compositestreatments (A, C, D, E, H and M) were significantly lower than in the control at , whereas B, F, G, I, J, K and L did not differ significantly from CK.

Leaf starch content showed the opposite tendency and was generally higher in many composite treatments than in the control (Figure 6C). Starch concentrations spanned roughly 4 to 9 mg g−1 FW. Groups G, H and K had significantly higher starch contents (about 8–9 mg g−1 FW) than the control (CK), which, together with groups A and D, formed the low-starch tier at around 4 mg g−1 FW (). The remaining composites, including B, C, E, F, I, J, L and M, showed intermediate starch levels that did not differ significantly from either the high-starch or low-starch groups, as indicated by the letter groupings in Figure 6C.

Expression of LcFUL and LcFLC in terminal buds under composite PGR applications showed numerical differences among treatments but no statistically significant differences relative to the control (Figure 7). Nevertheless, composite treatments with very low or no inflorescence formation, such as E and F, tended to have the lowest LcFUL and highest LcFLC transcript levels, whereas applications associated with higher flowering proportions (e.g., H, K, L and M) generally showed higher LcFUL and slightly reduced LcFLC expression. These qualitative trends are consistent with the contrasting floral versus vegetative outcomes observed among composite treatments.

Figure 7.

Relative expression of LcFUL and LcFLC in terminal buds of ‘Ziniangxi’ after composite PGR treatments. Expression values were normalized to LcActin and expressed as fold change relative to CK (). Bars represent mean ± SE (). Same letters above columns denote no significant differences between treatments according to Tukey (HSD) test at .

4. Discussion

4.1. Partial Recovery of Flowering Under Warm–Humid, Marginal-Chill Winters

The effects of appropriately timed PGR programs on the stability of floral induction in the late litchi cultivar ‘Ziniangxi’ were evaluated under warm–humid, marginal-chill winter conditions. During the experimental period, only seven chilling days with mean temperature ≤ 15 °C were recorded, and flowering remained unstable, with frequent floral reversion among tagged shoots (Figure 1A). Against this background, the single and composite applications (Table 1 and Table 2) evaluated here provide a quantitative, though exploratory, assessment of how chemical cues may partly compensate for insufficient chilling in a late-maturing cultivar.

The flowering responses observed in ‘Ziniangxi’ are broadly consistent with earlier reports that inadequate winter chill suppresses flowering competence and destabilizes bud fate in litchi and other evergreen fruit trees [1,2,31,32]. Under the marginal-chill conditions of this study, even the more effective programs increased the flowering proportion only to about one third to two thirds of tagged shoots, and a substantial fraction of buds still reverted to vegetative growth (Figure 4A and Figure 6A). This partial response agrees with field observations that late cultivars show large year-to-year variation in flowering under warm winters, and it underscores the relatively strong chilling demand of ‘Ziniangxi’ [2,5]. At the same time, the clear ranking among treatments, particularly in the composite trial where groups H (DA-6 0.40 g/L+ KH2PO4 1.00 g/L), L (BR 0.05 mg/L + ABA 0.06 mg/L + KH2PO4 1.00 g/L) and M (6-BA 13.33 mg/L + Triacontanol 0.67 mg/L + KH2PO4 1.00 g/L) reached floral proportions of 0.63 and 0.50, respectively, indicates that chemical applications can meaningfully shift the balance between floral and vegetative fates under suboptimal climatic cues (Figure 6A).

The performance of individual PGRs and composites is aligned with their known physiological roles in woody perennials [23,27,31]. Among single agents, ethephon at 80 mg/L and ABA at 3.33 mg/L produced the clearest numerical gains in floral proportion compared with the water control (Figure 5A). By contrast, oxyfluorfen at 1.80 mg L−1 did not markedly change the proportion of shoots scored as floral relative to CK. In this field trial, flowering status was recorded at the shoot level based on the presence of an inflorescence primordium and did not distinguish between pure and leafy inflorescences; therefore, any potential influence of oxyfluorfen on floral purity was not quantified and can only be inferred qualitatively from shoot phenotypes. These patterns are consistent with previous findings that ethylene releasers can reinforce bud rest and improve flowering after marginal chill, that ABA promotes bud maturation and readiness for floral transition, and that leaf-removal herbicides primarily refine inflorescence purity [24,28,33]. Composite formulations that combined ethephon and ABA with growth retardants, such as uniconazole, DA-6, 6-BA or BR, together with KH2PO4 and micronutrients such as boron (groups G, H, J, K, L and M), further increased flowering proportions and leaf starch contents relative to the control, suggesting that such regulator–nutrient mixtures can partly compensate for insufficient chilling [18,34] (Table 2 and Figure 6A).

4.2. Hormonal Crosstalk, Carbohydrate Status and Floral Gene Expression

The ranking of single and composite treatments is consistent with the roles of ethylene, ABA and brassinosteroids in bud regulation outlined in the Introduction. In the present experiment, ethephon and ABA based programs shifted a greater fraction of shoots into the flowering category than the control, and several composite applications that combined ethephon, ABA, BR and KH2PO4 (G, H, J, K, L and M) further increased flowering proportions (Figure 6A). Under warm–humid, marginal-chill conditions, these responses suggest that exogenous ethylene and ABA helped reinforce a rest- and maturation-like status at the shoot apex, while low doses of BR together with KH2PO4 and boron (applied as KH2PO4 and boric acid in the composite formulations) supported subsequent differentiation and inflorescence development [21,23,35]. This pattern is consistent with current concepts of hormonal crosstalk, in which ethylene- and ABA-mediated stress and dormancy signalling interact with BR-mediated growth promotion to modulate meristem fate under suboptimal chilling [22,23]. In this view, PGR–nutrient programs do not replace winter chill but strengthen and prolong developmental cues that were only weakly supplied by the prevailing climate.

Carbohydrate measurements are consistent with this interpretation. Across bud fates, flowering shoots were associated with higher leaf starch, and composite applications with the strongest flowering responses tended to show both increased starch and moderate sucrose levels, rather than very high sucrose alone [36] (Figure 1B–D, Figure 4B,C and Figure 6B,C). Figure 1 characterizes baseline differences in carbohydrate status between shoots that, in the absence of PGR applications, naturally proceeded to floral transition and those that reverted to vegetative growth under marginal-chill conditions. In contrast, Figure 4 and Figure 6 show how single and composite PGR applications subsequently modified both bud fate and carbohydrate profiles relative to the water control at defined sampling dates. In both settings, shoots that ultimately became floral tend to have higher leaf starch than vegetative shoots, whereas sucrose differences are smaller and more transient, consistent with sucrose being a more labile carbon pool (Figure 1B–F). Thus, Figure 1 reflects the underlying carbohydrate bias associated with bud fate under the prevailing climate, while Figure 4 and Figure 6 illustrate how PGR–nutrient applications can partly reinforce or mimic this bias. This pattern points to strengthened carbon buffering around the apex as a positive correlate of floral commitment under marginal chill, while sucrose differences at single time points remained modest (Figure 1B–F).

At the gene-expression level, floral buds showed higher LcFUL transcript abundance and vegetative buds showed higher LcFLC, LcAP2, LcTFL1-1, LcFD and LcLFY, indicating that changes in the balance of the LcFT/LcTFL1/LcFLC module accompany the divergence between floral and vegetative fates [33] (Figure 2). At the same time, LcFLC remained relatively high even in successful treatments, and none of the applications produced a clear repression of LcFLC at the whole-bud level (Figure 5B and Figure 7). In the single-agent trial, both LcFUL and LcFLC tended to be numerically higher in PGR-treated buds than in the control, yet differences among treatments were not statistically significant. Under marginal chill, buds classified as “flowering” may contain a mixture of floral and vegetative primordia, so whole-bud qPCR measurements are likely to reflect composite signals from tissues with different developmental identities [37,38]. The relatively high LcFLC signal observed even in treatments that increased the proportion of flowering buds is consistent with this possibility and with the frequent occurrence of inflorescences with leafy admixture in ‘Ziniangxi’, suggesting that many apices may occupy an intermediate state in which promotive and repressive influences coexist [30,33]. However, the present data set does not resolve the internal structure of the apices and no histological information on floral meristems is available, so these patterns should be interpreted as correlative rather than mechanistic. They are compatible with mechanistic models of hormonal crosstalk and sugar signalling in floral control, but the qPCR data alone does not provide definitive evidence for causal links between specific PGR-induced changes, LcFUL/LcFLC activity and floral transition in litchi.

4.3. Limitations of the Present Study and Implications for Practice

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, all trials were conducted in a single winter at one site on a single late-maturing cultivar, so the responses observed here may not fully represent other years, locations or genotypes. Second, flowering was assessed at the shoot level with a limited number of tagged shoots per treatment, which constrains statistical power for detecting moderate treatment effects on flowering proportions and Section 2.4. In addition, floral purity (leafless versus leafy inflorescences) was not quantified in this experiment; leafy admixture within inflorescences was recorded qualitatively rather than as a systematic count at full flowering. Third, carbohydrate and gene-expression measurements were restricted to a small set of tissues and two sampling dates; more resolved temporal profiles and additional signalling components would be needed to delineate causal sequences. Fourth, the study did not extend to fruit set, yield, quality or residue analyses, which are essential for translating candidate programs into recommendations for commercial orchards. These limitations mean that the current work should be viewed as an exploratory field study that identifies promising combinations and patterns, rather than a definitive test of mechanisms.

Despite these constraints, the study provides a coherent framework for interpreting how PGR–nutrient applications interact with marginal winter chill in a late litchi cultivar. The convergence of flowering outcomes, carbohydrate signatures and LcFUL/LcFLC expression patterns suggests that carefully timed programs based on ethephon and ABA, complemented by BR, 6-BA and KH2PO4/micronutrients, can partially stabilize floral induction in ‘Ziniangxi’ under warm–humid winters. At the same time, the persistent high expression of LcFLC and the incomplete recovery of flowering remind us that there is a climatic ceiling beyond which chemical intervention alone is unlikely to restore full flowering. Future multi-year and multi-site trials that integrate chill modelling, detailed physiological measurements and fruiting and residue assessments will be required to convert these exploratory findings into robust agronomic recommendations.

5. Conclusions

Under the warm, low-chill conditions of winter 2023–2024 in Hainan, only a subset of the tested PGR applications substantially improved floral induction in the late-maturing litchi cultivar ‘Ziniangxi’. Single-agent applications of ABA, ethephon and brassinolide and several ethephon–ABA–nutrient application programs increased the proportion of flowering shoots and shifted bud carbohydrate status towards higher leaf starch, but did not fully compensate for the lack of winter chilling. Whole-bud expression patterns of LcFUL and LcFLC indicated that promotive and repressive floral signals remained in partial balance under marginal chill, supporting the view that PGR applications can modulate but not override the underlying chill requirement.

From a management perspective, PGR applications that combine ethephon and ABA, supplemented with brassinolide or 6-BA and nutrients, emerge as priority candidates for further refinement in late-maturing litchi under warm winters. Future optimization should explicitly account for the prevailing chilling regime by adjusting application timing and dose relative to accumulated chill and tree carbohydrate status, and by evaluating potential trade-offs between floral purity and overall flowering intensity. The present results highlight the need for multi-year, multi-site field experiments spanning a gradient of winter temperatures and cultivars to quantify how flowering responses to PGR application programs scale with chill accumulation, to include explicit scoring of floral purity (leafless versus leafy inflorescences) at full flowering, and to develop chill-sensitive guidelines for the use of PGRs in late-maturing litchi under a warming climate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Y., F.H. and X.W.; methodology, M.Y., F.H. and X.W.; investigation, M.Y., X.W., D.C. and Y.H.; resources, F.H. and X.W.; data curation, M.Y. and D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y.; writing—review and editing, M.Y.; visualization, M.Y. and Y.H.; supervision, M.Y., T.Y. and Z.C.; project administration, M.Y., F.H. and X.W.; funding acquisition, M.Y., F.H. and X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (No. 32402521), Hainan Academy of Agricultural Sciences Research Startup Fund for Introduced Talents (No. ITFT2024RCQD02), Hainan Provincial Science and Technology Talent Innovation Program (No. KJRC2023C17), the China Litchi and Longan Industry Technology Research System (No. CARS-32-21), and Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation (325QN479).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, H.; Yang, S.; Su, Z.; Ou, S.; Pan, W.; Peng, X. Analysis of the National Litchi Production in 2024 and Management Suggestions. China Trop. Agric. 2024, 3, 8–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G.; Yang, S.; Qi, W. Analysis of China’s Litchi Production in 2025 and Management Recommendations. China Trop. Agric. 2025, 2, 8–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.B.; Chen, H.B. A phase approach towards floral formation in lychee. Acta Hortic. 2005, 665, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Maurya, J.P.; Azeez, A.; Miskolczi, P.; Tylewicz, S.; Stojkovič, K.; Bhalerao, R.P. A genetic network mediating the control of bud break in hybrid aspen. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.C.; Wu, Z.C.; Chen, R.Y.; Abbas, F.; Hu, G.B.; Huang, X.M.; Wang, H.C. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing and mRNA hybridization indicate key bud events and LcFT1 and LcTFL1-2 mRNA transportability during floral transition in litchi. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 3613–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkie, J.D.; Sedgley, M.; Olesen, T. Regulation of floral initiation in horticultural trees. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 3215–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, N.; Pandey, S.K.; Nath, V. Effect of weather on panicle development, flower morphogenesis and fruit set in litchi cv. Shahi. Plant Physiol. Rep. 2025, 30, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Longan fruit tree physiology and its flowering induction. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Physiology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Shen, J.; Wei, Y.; Chen, H. Transcriptome profiling of litchi leaves in response to low temperature reveals candidate regulatory genes and key metabolic events during floral induction. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, H.; Zhou, B. Genome-wide transcriptome analysis reveals the molecular mechanism of high temperature-induced floral abortion in Litchi chinensis. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Klasfeld, S.; Jeong, C.W.; Jin, R.; Goto, K.; Yamaguchi, N.; Wagner, D. TERMINAL FLOWER 1–FD complex target genes and competition with FLOWERING LOCUS T. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhang, H.; Kong, Z.; Qian, D.; Liu, X.; Zhao, M.; Li, J. Cytokinin response factor LcARR11 promotes floral bud physiological differentiation by activating LcIPT3 and LcFT1 in litchi. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Q.; Wei, J.; Wu, Z.; Mo, X.; Qing, H.; Shi, Y.; Guo, H.; Sheng, J.; Ding, F.; Zhang, S. Litchi LcAP1-1 and LcAP1-2 Exhibit Different Roles in Flowering Time. Plants 2025, 14, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.M.; Zhang, H.F.; Tian, Q.; Wang, H.C.; Zhang, F.Y.; Tian, X.; Zeng, R.F.; Huang, X.M. MIKC type MADS-box transcription factor LcSVP2 is involved in dormancy regulation of the terminal buds in evergreen perennial litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balanzà, V.; Martínez-Fernández, I.; Ferrándiz, C. Sequential action of FRUITFULL as a modulator of the activity of the floral regulators SVP and SOC1. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 1193–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Li, X.; Du, L.; Manuela, D.; Xu, M. LEAFY and APETALA1 down-regulate ZINC FINGER PROTEIN 1 and 8 to release their repression on class B and C floral homeotic genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2221181120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Qie, M.; Feng, X.; Xie, J.; Cao, M.; He, S.; Jiang, Y.; Hou, Z. Sucrose participates in the flower bud differentiation regulation promoted by short pruning in blueberry. Fruit Res. 2025, 5, e025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.F.; Kim, H.J.; Chen, H.B.; Rahman, J.; Lu, X.Y.; Zhou, B.Y. Carbohydrate accumulation and flowering-related gene expression levels at different developmental stages of terminal shoots in Litchi chinensis. HortScience 2014, 49, 1381–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Purbey, S.K.; Sharma, S. Improving Flowering and Fruit Quality in Litchi: Applying PGRs and Chemical Regulants. In ICAR–National Research Centre on Litchi; EXCEL India Publishers: Delhi, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, S.L. Role of plant growth regulators in floriculture: An overview. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2019, 8, 789–796. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, B.; Deng, C.; Tian, Q.; Ouyang, J.; Zeng, R.; Wang, H.; Huang, X. Application of ethephon manually or via drone enforces bud dormancy and enhances flowering response to chilling in litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronje, R.B.; Hajari, E.; Jonker, A.; Ratlapane, I.M.; Huang, X.; Theron, K.I.; Hoffman, E.W. Foliar application of ethephon induces bud dormancy and affects gene expression of dormancy- and flowering-related genes in ‘Mauritius’ litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 276, 153768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, Z. Abscisic acid promotes flowering and enhances LcAP1 expression in Litchi chinensis Sonn. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2013, 88, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hu, F.; Fan, H.; Wang, X.; Han, B.; Lin, Y. Effects of five plant growth regulators on blooming and fruit-setting of ‘Feizixiao’ litchi. Southwest China J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 4, 915–919. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kutschera, U.; Wang, Z.Y. Brassinosteroid action in flowering plants: A Darwinian perspective. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 3511–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.S. Changes in cytokinins before and during early flower bud differentiation in lychee (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Plant Physiol. 1991, 96, 1203–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, T.; Wang, M.; Dong, Y.; Yang, M.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, R.; Chen, Z.; Hu, F.; Wang, X. Effect of compound plant growth regulators on the flowering and fruit setting in litchi. China Fruits 2024, 4, 83–95. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.Q.; Wu, W.D.; Yan, T.T.; Yang, M.; Hu, F. Regulation effect of different growth regulators on the flowering of ’Feizixiao’ litchi. China Trop. Agric. 2024, 2, 30–34, 29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian, K.; Arya, M.S.; Reshma, U.R.; Anaswara, S.J.; Thampi, S.S. Impact of plant growth regulators on fruit production. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8, 800–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Xiao, Q.; Qiu, H.; Chen, C.; Chen, H. Integrative effect of drought and low temperature on litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) Flor. Initiat. Reveal. Dyn. Genome-Wide Transcr. Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32005. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.X. Studies on the Relationship Between Flowering and Chilling Accumulation and Flowering Regulation in litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Master’s Thesis, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Dai, J.; Ranjitkar, S.; Yu, H.; Xu, J.; Luedeling, E. Chilling and heat requirements for flowering in temperate fruit trees. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2014, 58, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.N.; Wei, Y.Z.; Shen, J.Y.; Lai, B.; Huang, X.M.; Ding, F.; Chen, H.B. Transcriptomic analysis of floral initiation in litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) Based De Novo RNA Sequencing. Plant Cell Rep. 2014, 33, 1723–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Turabi, Z.M.A.; Trad, S.A.; Al-Zurfi, M.T.H. Effect of spraying with brassinolide and boric acid on growth and flowering of Osteospermum ecklonis. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1487, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, D. Gibberellins, brassinolide, and ethylene signaling were involved in flower differentiation and development in Nelumbo nucifera. Hortic. Plant J. 2022, 8, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, L.H.; Pasriga, R.; Yoon, J.; Jeon, J.S.; An, G. Roles of sugars in controlling flowering time. J. Plant Biol. 2018, 61, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.M.; Chen, H.B. Studies on shoot, flower and fruit development in litchi and strategies for improved litchi production. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1029, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Zhang, S.; Chen, H.; Su, Z.; Zhang, R.; Xiao, Q.; Li, H. Promoter difference of LcFT1 is a leading cause of natural variation of flowering timing in different litchi cultivars (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Plant Sci. 2015, 241, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).