Auxin-Amido Synthetase Gene ThGH3.1 Regulates Auxin Levels to Suppress Root Development in Transgenic Arabidopsis and Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Hairy Roots

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Gene Isolation and Sequence Analysis of ThGH3.1

2.3. Construction of ThGH3.1 Overexpression and ThGH3.1 RNA Interference Vectors

2.4. Agrobacterium Rhizogenes-Mediated Hairy Roots Transformation and Identification

2.5. Phenotype Analysis of the Transgenic Hairy Roots in T. hemsleyanum

2.6. Determination of Endogenous Phytohormones in Hairy Roots of T. hemsleyanum

2.7. Heterologous Expression of the ThGH3.1 Gene in Arabidopsis thaliana

2.8. Phenotype Analysis and Endogenous Phytohormones Determination of Transgenic Arabidopsis

2.9. Evaluation of Transgenic Arabidopsis Thaliana in Response to IAA

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cloning and Molecular Characterization of ThGH3.1

3.2. Induction and Identification of the Transgenic Hairy Roots in T. hemsleyanum

3.3. Overexpression of ThGH3.1 Inhibited the Total Length and Lateral Root Number of Hairy Roots and Significantly Increased Auxin Contents in T. hemsleyanum

3.4. RNA Interference of ThGH3.1 Promoted the Total Length and Lateral Root Number of Hairy Roots, and Significantly Decreased Auxin Contents in T. hemsleyanum

3.5. Acquisition of ThGH3.1-Overexpressing Lines and Screening of Pure Lines in Transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana

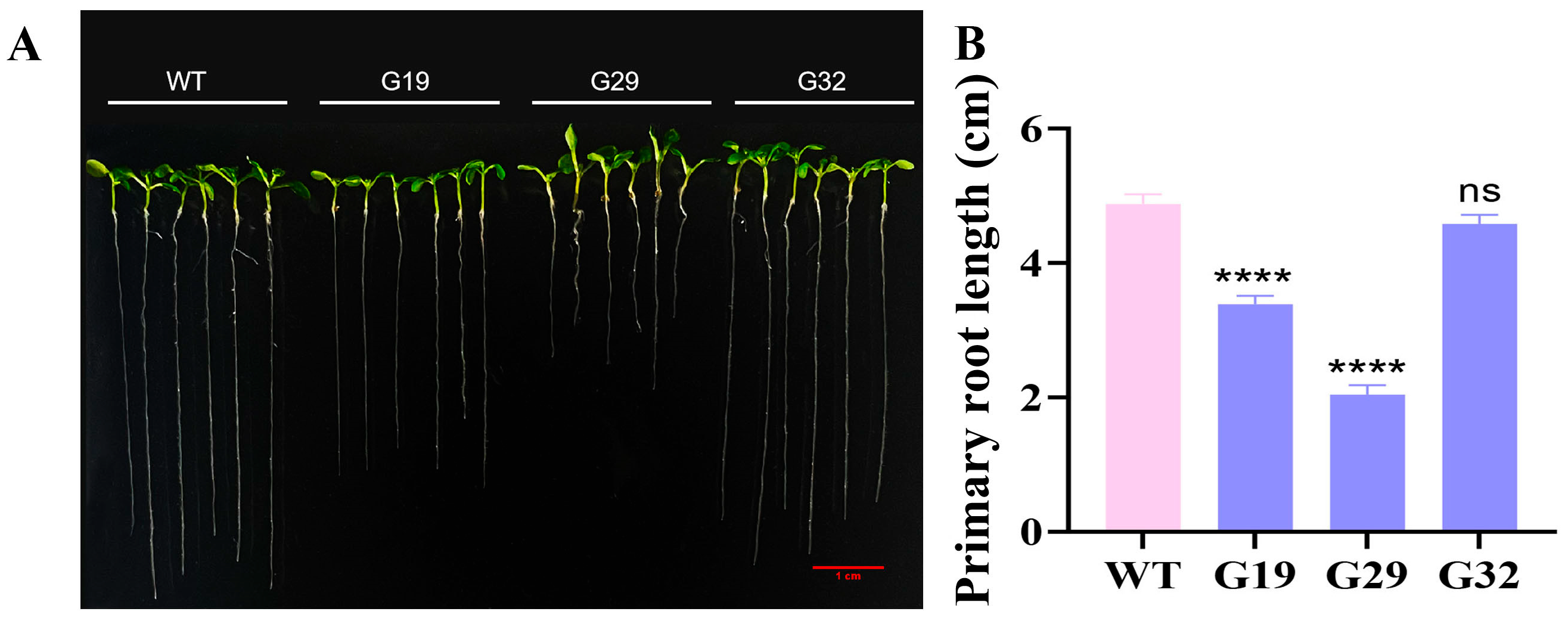

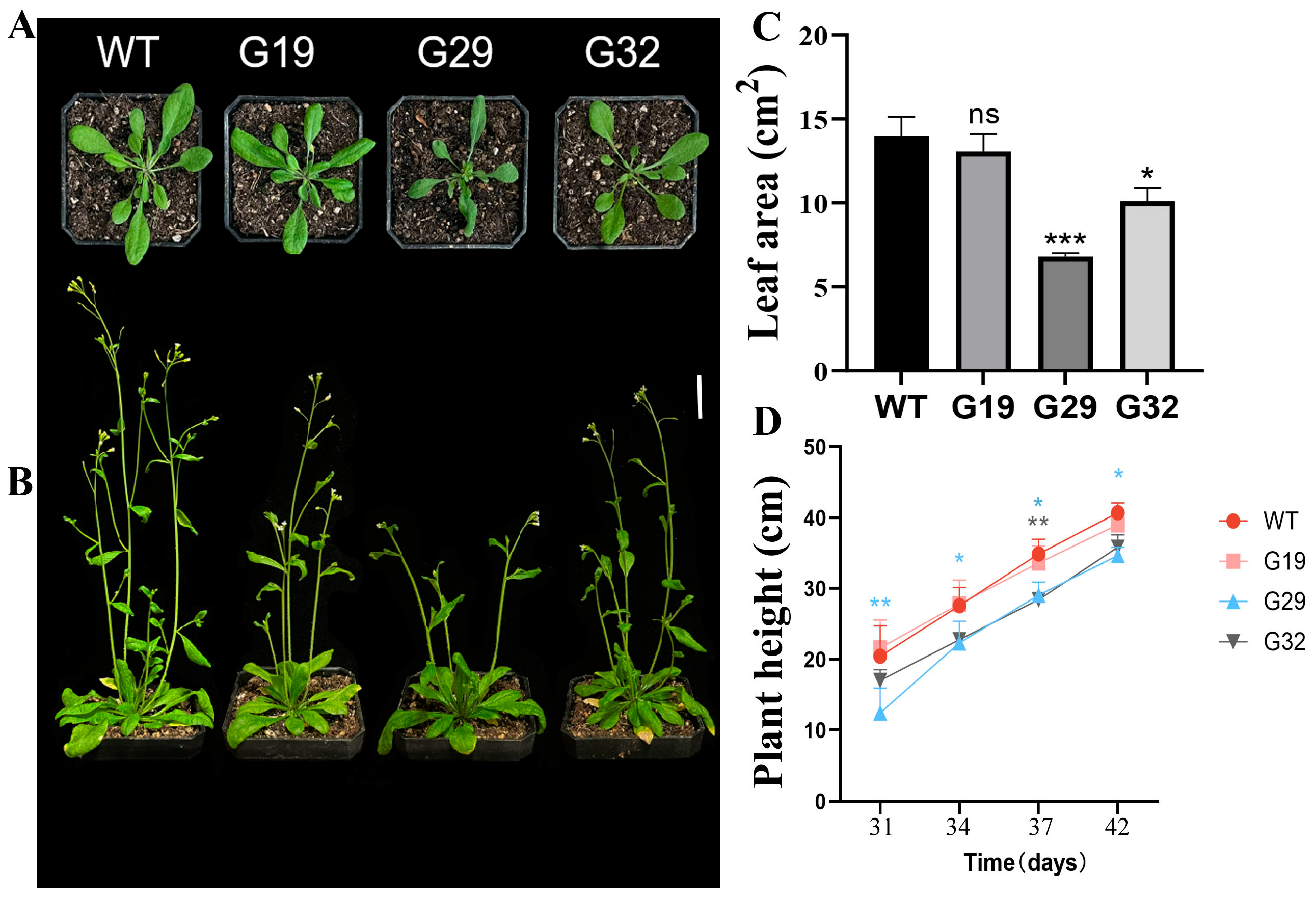

3.6. Phenotypic Analysis of Transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana Overexpressing ThGH3.1

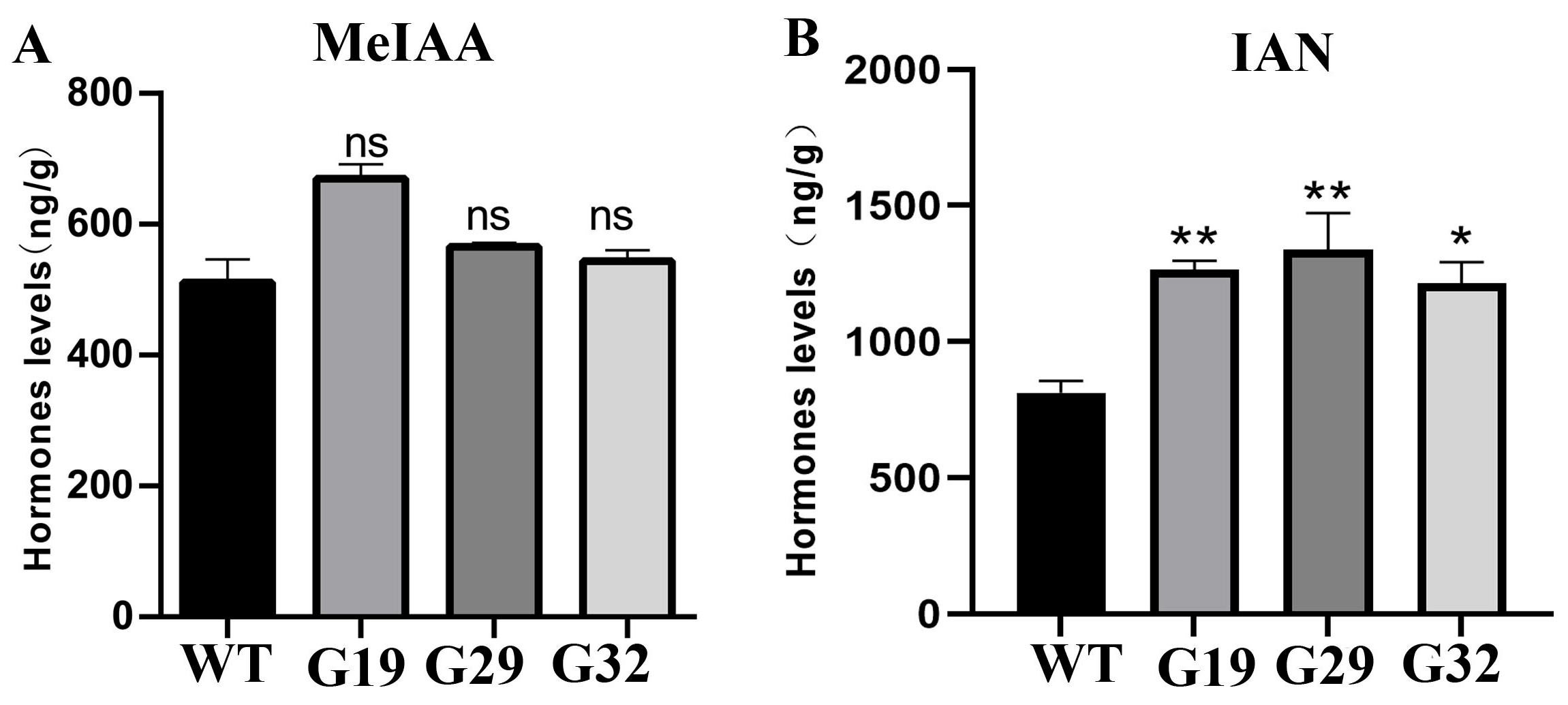

3.7. Hormone Levels of Transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana Overexpressing ThGH3.1

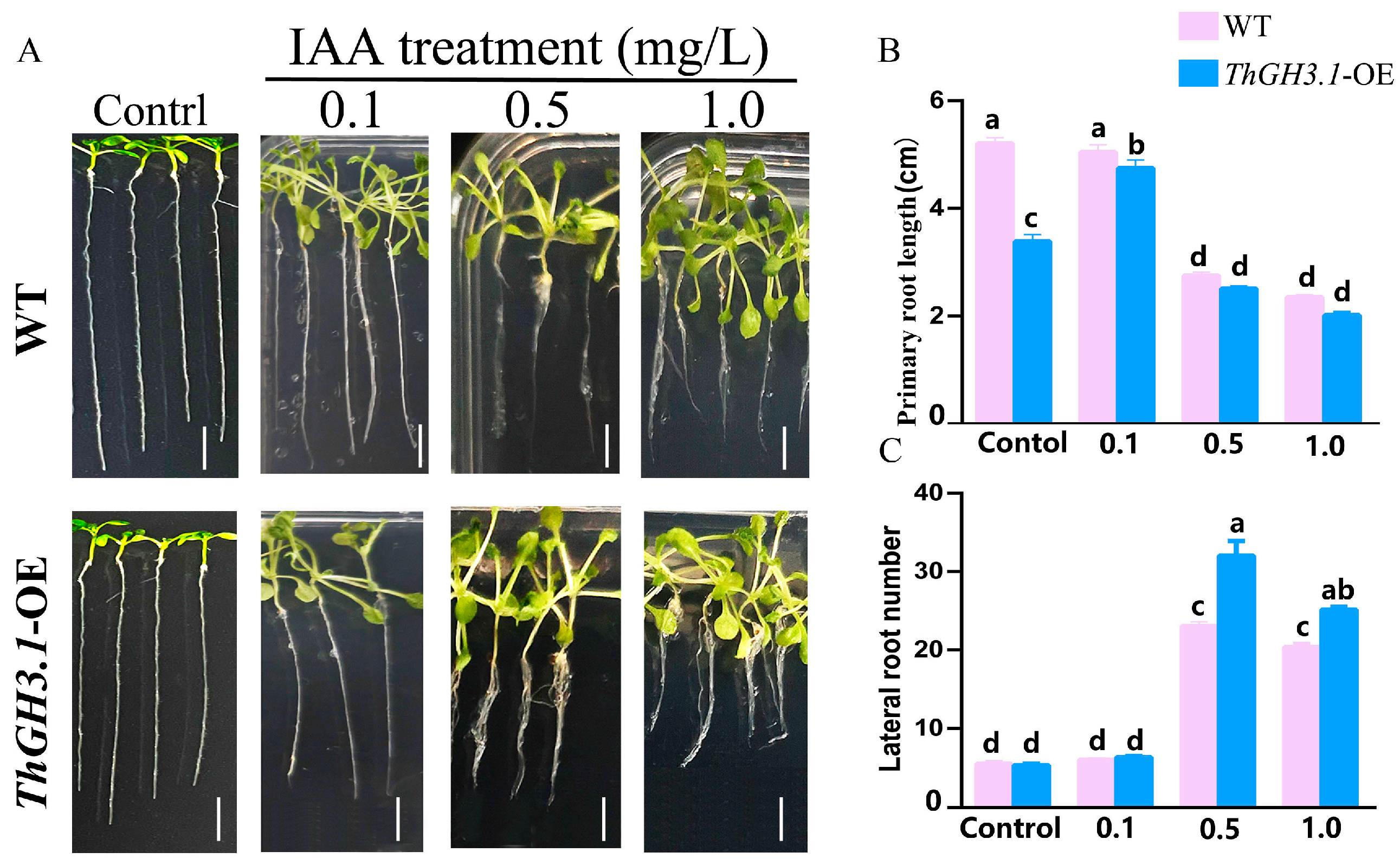

3.8. Hormone Response of Transgenic ThGH3.1-Expressing Arabidopsis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Z.; Ye, W.; Feng, L. Bioactives and metabolites of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum root extract alleviate DSS-induced ulcerative colitis by targeting the SYK protein in the B cell receptor signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 322, 117563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Ye, W.; Fu, C.; Gitzendanner, M.A.; Soltis, P.S.; Soltis, D.E.; Qiu, Y. Evolutionary insights from comparative transcriptome and transcriptome-wide coalescence analyses in Tetrastigma hemsleyanum. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.X.; Wu, H.; Peng, X.; Qiu, D.; Tao, Z.F.; Qiu, W.Y. Reference genes selection and system establishment for RT-qPCR of T. hemsleyanum in root development stages. Mol. Plant Breed. 2020, 18, 6785–6792. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Qian, L.; Zhu, W.; Qiu, J.; Lu, Q.; Wang, X.; Wu, Q.; Ruan, S.; Huang, Y. Integrated analysis of the transcriptome and metabolome of purple and green leaves of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum reveals gene expression patterns involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, T.; Tong, X.; Li, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Bao, S.; Li, C. Effect of rhizosphere soil on flavonoid metabolism in roots of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 57, 615–622. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Wu, P.; Li, Y.; Tong, X.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Xiang, T. Effect of endophytic fungi on the host plant growth, expression of expansin gene and flavonoid content in Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Diels & Gilg ex Diels. Plant Soil 2017, 417, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zierer, W.; Rüscher, D.; Sonnewald, U.; Sonnewald, S. Tuber and tuberous root development. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2021, 72, 551–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.H.; Xing, W.; Wang, H.; Chu, M.Y.; Liu, D.L. Development and bulking mechanism of storage organs in root and tuber crops. Plant Physiol. J. 2024, 60, 1726–1736. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, L.; Lei, J.; Chai, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X. Integrated transcriptional and metabolomic analysis of factors influencing root tuber enlargement during early sweet potato development. Genes 2024, 15, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondhare, K.R.; Kumar, A.; Patil, N.S.; Malankar, N.N.; Saha, K.; Banerjee, A.K. Development of aerial and belowground tubers in potato is governed by photoperiod and epigenetic mechanism. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 1071–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, L. Regulation of storage organ formation by long-distance tuberigen signals in potato. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, M.; Torres-Pérez, R.; Wahl, V.; Cruz-Oró, E.; Rodríguez-Buey, M.L.; Zamarreño, A.M.; Martín-Jouve, B.; García-Mina, J.M.; Oliveros, J.C.; Prat, S.; et al. Spatial control of potato tuberization by the TCP transcription factor Branched1b. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.A.; Lee, H.S.; Huh, E.J.; Huh, G.H.; Paek, K.H.; Shin, J.S.; Bae, J.M. SRD1 is involved in the auxin-mediated initial thickening growth of storage root by enhancing proliferation of metaxylem and cambium cells in sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas). J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 1337–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.A.; Lee, H.S.; Huh, G.H.; Oh, M.J.; Paek, K.H.; Shin, J.S.; Bae, J.M. A sweet potato SRD1 promoter confers strong root-, taproot-, and tuber-specific expression in Arabidopsis, carrot, and potato. Transgenic Res. 2012, 21, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, E.; Kloosterman, B.; Oortwijn, M.; Kohlen, W.; Bouwmeester, H.J.; Visser, R.G.; Bachem, C.W. The effects of auxin and strigolactones on tuber initiation and stolon architecture in potato. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 4539–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Zhao, K.; Lei, H.; Shen, X.; Liu, Y.; Liao, X.; Li, T. Genome-wide analysis of the GH3 family in apple (Malus × domestica). BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Park, S.; Im, J.H.; Yi, H. Genome-wide identification of GH3 genes in Brassica oleracea and identification of a promoter region for anther-specific expression of a GH3 gene. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Lin, P.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, D.; Qin, L.; Xu, F.; Su, Y.; Wu, Q.; Que, Y. Genome-wide identification of auxin-responsive GH3 gene family in Saccharum and the expression of ScGH3-1 in stress response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa, M.; Yabe, N.; Ichikawa, T.; Yamamoto, Y.Y.; Yoshizumi, T.; Hasunuma, K.; Matsui, M. DFL1, an auxin-responsive GH3 gene homologue, negatively regulates shoot cell elongation and lateral root formation, and positively regulates the light response of hypocotyl length. Plant J. 2001, 25, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takase, T.; Nakazawa, M.; Ishikawa, A.; Kawashima, M.; Ichikawa, T.; Takahashi, N.; Shimada, H.; Manabe, K.; Matsui, M. ydk1-D, an auxin-responsive GH3 mutant that is involved in hypocotyl and root elongation. Plant J. 2004, 37, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, L.; Mongelard, G.; Floková, K.; Pacurar, D.I.; Novák, O.; Staswick, P.; Kowalczyk, M.; Pacurar, M.; Demailly, H.; Geiss, G.; et al. Auxin controls Arabidopsis adventitious root initiation by regulating jasmonic acid homeostasis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2515–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherp, A.M.; Westfall, C.S.; Alvarez, S.; Jez, J.M. Arabidopsis thaliana GH3.15 acyl acid amido synthetase has a highly specific substrate preference for the auxin precursor indole-3-butyric acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 4277–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.I.; Arai, K.; Aoi, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Hira, H.; Guo, R.; Hu, Y.; Ge, C.; Zhao, Y.; Kasahara, H.; et al. The main oxidative inactivation pathway of the plant hormone auxin. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Stone, J.M. Arabidopsis thaliana GH3.9 influences primary root growth. Planta 2007, 226, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Cao, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhao, J.; Xu, C.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Activation of the indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase GH3-8 suppresses expansin expression and promotes salicylate- and jasmonate-independent basal immunity in rice. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xia, Y.; Sun, D.; Sun, Y. Altered architecture and enhanced drought tolerance in rice via the down-regulation of indole-3-acetic acid by TLD1/OsGH3.13 activation. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 1889–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Wu, N.; Fu, J.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Xiong, L. A GH3 family member, OsGH3-2, modulates auxin and abscisic acid levels and differentially affects drought and cold tolerance in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 6467–6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yang, D.; Sun, L.; Li, Q.; Mao, B.; He, Z. The systemic acquired resistance regulator OsNPR1 attenuates growth by repressing auxin signaling through promoting IAA-amido synthase expression. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, G.; Huang, R.; Zhang, D.; Li, M.; Li, G.; Li, W.; Ahiakpa, J.K.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, J. SlGH3.15, a member of the GH3 gene family, regulates lateral root development and gravitropism response by modulating auxin homeostasis in tomato. Plant Sci. 2023, 330, 111638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, Y.; Feng, C.; Wei, Y.; Peng, X.; Guo, X.; Guo, X.; Zhai, Z.; Li, J.; Shen, X.; et al. Overexpression of MsGH3.5 inhibits shoot and root development through the auxin and cytokinin pathways in apple plants. Plant J. 2020, 103, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jiao, M.; Huang, X.; Liang, W.; Ma, Z.; Lu, Z.; Tian, S.; Gao, X.; Fan, L.; He, X.; et al. The auxin-responsive CsSPL9-CsGH3.4 module finely regulates auxin levels to suppress the development of adventitious roots in tea (Camellia sinensis). Plant J. 2024, 119, 2273–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, T.H.; Li, J.S.; Bao, S.Y.; Xu, Z.X.; Wang, L.Z.; Long, F.Z.; He, C.J. Digital RNA-seq transcriptome plus tissue anatomy analyses reveal the developmental mechanism of the calabash-shaped root in Tetrastigma hemsleyanum. Tree Physiol. 2021, 41, 1729–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for the rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvaud, S.; Gabella, C.; Lisacek, F.; Stockinger, H.; Ioannidis, V.; Durinx, C. Expasy, the Swiss Bioinformatics Resource Portal, as designed by its users. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W216–W227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, S.; Croning, M.D.; Apweiler, R. Evaluation of methods for the prediction of membrane spanning regions. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Xiang, T.; Song, Y.; Huang, L.; Sun, Y.; Han, Y. Transgenic hairy roots of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum: Induction, propagation, genetic characteristics and medicinal components. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. 2015, 122, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.Q.; Welti, R.; Wang, X.M. Quantitative analysis of major plant hormones in crude plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2010, 5, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Q.F.; Zong, Y.; Qian, M.J. Simultaneous quantitative determination of major plant hormones in pear flowers and fruit by UPLC/ESI-MS/MS. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 1766–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xia, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, L.; Tan, S. Indole-3-propionic acid regulates lateral root development by targeting auxin signaling in Arabidopsis. iScience 2024, 27, 110363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Enhebayaer Qi, Y.H. Research Advances in Biological Functions of GH3 Gene Family in Plants. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2023, 58, 770–782. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher, C.; Keyzers, R.A.; Boss, P.K.; Davies, C. Sequestration of auxin by the indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase GH3-1 in grape berry (Vitis vinifera L.) and the proposed role of auxin conjugation during ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 3615–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, P.; Li, T.; Shi, W.; Ma, Q.; Di, D. The roles of Gretchen Hagen 3 (GH3)-dependent auxin conjugation in the regulation of plant development and stress adaptation. Plants 2023, 12, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, S.; Jin, L.; Yu, X.; Yang, C.; Liu, X.M.; Zhang, Z.J.; Liu, Y.S.; Li, C.; Ma, F.W. Silencing of early auxin responsive genes MdGH3-2/12 reduces the resistance to Fusarium solani in apple. J. Integr. Agr. 2024, 23, 3012–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, B.; Wu, J.Q.; Han, X.Q.; Bian, X.X.; Xu, Z.J.; Sun, C.; Wang, R.Y.; Zhang, W.Y.; Liang, F.; Zhang, H.M.; et al. Auxin homeostasis is maintained by sly-miR167-SlARF8A/B-SlGH3.4 feedback module in the development of locular and placental tissues of tomato fruits. New Phytol. 2023, 241, 1177–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkryl, Y.; Vasyutkina, E.; Gorpenchenko, T.; Mironova, A.A.; Rusapetova, T.V.; Velansky, P.V.; Bulgakov, V.P.; Yugay, Y.A. Salicylic acid and jasmonic acid biosynthetic pathways are simultaneously activated in transgenic Arabidopsis expressing the rolB/C gene from Ipomoea batatas. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 208, 108521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lore, G.; Evi, C.; Nicolás, P.M.; Jhon, V.M.; Ana Cristina, J.M.; Savio, D.R.; Liesbeth, D.M.; Veronique, J.; Marc, V.M.; Barbara, D.C.; et al. Rhizogenic Agrobacterium protein RolB interacts with the TOPLESS repressor proteins to reprogram plant immunity and development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2210300120. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, X.; Yu, H.; Jiang, J.; Zheng, R.; Li, F.; Yu, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chen, T.; Wang, L.; et al. Auxin-Amido Synthetase Gene ThGH3.1 Regulates Auxin Levels to Suppress Root Development in Transgenic Arabidopsis and Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Hairy Roots. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121512

Huang X, Yu H, Jiang J, Zheng R, Li F, Yu Z, Zeng Z, Chen Z, Chen T, Wang L, et al. Auxin-Amido Synthetase Gene ThGH3.1 Regulates Auxin Levels to Suppress Root Development in Transgenic Arabidopsis and Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Hairy Roots. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121512

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Xiaoping, Hao Yu, Jie Jiang, Ruyi Zheng, Fangzhen Li, Zhiming Yu, Zhanghui Zeng, Zhehao Chen, Tao Chen, Lilin Wang, and et al. 2025. "Auxin-Amido Synthetase Gene ThGH3.1 Regulates Auxin Levels to Suppress Root Development in Transgenic Arabidopsis and Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Hairy Roots" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121512

APA StyleHuang, X., Yu, H., Jiang, J., Zheng, R., Li, F., Yu, Z., Zeng, Z., Chen, Z., Chen, T., Wang, L., & Xiang, T. (2025). Auxin-Amido Synthetase Gene ThGH3.1 Regulates Auxin Levels to Suppress Root Development in Transgenic Arabidopsis and Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Hairy Roots. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121512