Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of water–fertilizer coupling on the water and fertilizer use efficiency, yield, and quality of fresh common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in high-latitude and high-altitude regions. For field water-saving, in 2022, six treatments were established, with irrigation rates of 100% FC (W1), 90% FC (W2), 80% FC (W3), 70% FC (W4), 60% FC (W5), and 50% FC (W6). Based on the experiment in 2022, a two-factor experiment (irrigation and fertilizer application rate) was implemented in 2023, and three fertilizer (N−P2O5−K2O) gradients were established: F1 (260−192−255 kg/ha), F2 (195−144−192 kg/ha), and F3 (131−97−127 kg/ha). Based on 2022, three irrigation rates were established at percentages of FC: W7 (100% FC), W8 (80% FC), and W9 (60% FC). Experiments in both years revealed a quadratic relationship (parabola equation) between yield and the rates of both irrigation and fertilization. Excessive fertilization did not consistently enhance yield, and reduced fertilizer application resulted in higher fertilizer partial factor productivity (PFP). Both years of experiments indicated that maintaining soil moisture at 80%~90% field capacity (FC) significantly improved fresh pod yield and water use efficiency (WUE) compared to other treatments. Under the same fertilizer level, reduced irrigation increased key fresh pod quality indicators, such as single-pod weight and soluble sugar content. In contrast, across varying fertilizer rates, these same indicators showed a positive correlation with the amount of fertilizer applied. Vitamin C (VC), soluble protein (SP), soluble solids content (SSC), and nitrate content (NC) reached their highest levels under high fertilizer treatment (N−P2O5−K2O: 260−192−255 kg/ha). Based on the differential comprehensive evaluation models, the study concluded that maintaining soil moisture at 80%~90% FC and applying fertilizer between N−P2O5−K2O: 195−144−192 kg/ha and N−P2O5−K2O: 260−192−255 kg/ha was the optimal strategy. This approach can alleviate the water scarcity pressure in high-latitude and high-altitude regions, and facilitate the selection of common bean management practices that maintain yield while improving quality and PFP, thereby offering theoretical and practical guidance for adapting water–fertilizer regimes to local climatic conditions.

1. Introduction

The common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) belongs to the Leguminosae family of annual herbaceous plants, recognized for its nutritional density and elevated mineral concentrations, with almost twice the protein content of that in cereal grains [1,2]. Under different agricultural ecological conditions, beans are grown on all continents, and China in Asia is one of the world‘s important producers [3]. Globally, the common bean contributes to 46% of the total legume production and serves as a critical nutritional resource for approximately 300 million individuals in developing nations, forming a dietary staple for socioeconomically vulnerable populations [4]. It has demonstrated positive effects in the prevention and treatment of diabetes, cardiovascular protection, and cancer prevention [5].

Common beans demonstrate heightened sensitivity to water deficit across their phenological stages, exhibiting maximum vulnerability during flowering and pod development stages. Water stress significantly reduces the number of pods and seeds per pod, leading to substantial yield reduction in beans [6,7,8,9,10]. Studies confirm that water stress negatively impacts photosynthetic efficiency and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, yield, and yield components of beans [11,12,13]. However, other evidence showed that deficit irrigation promoted nitrogen, amino acid, and soluble sugar accumulation in common bean [14]. Under adequate irrigation, dry bean yields can reach 4 t/ha [15]. However, irrigation rates exceeding crop requirements reduce yield, as well as provide favorable conditions for the spread of diseases [16,17]. In addition to the irrigation rate, irrigation frequency also influences the growth of beans. Existing studies indicate that increased irrigation frequency enhances bean yield [18,19], but experimental outcomes vary across studies. Hosseini et al. [20] established an 8-day irrigation interval as the optimal irrigation frequency for Phaseolus vulgaris L., while higher frequencies showed no significant improvements in yield or water use efficiency (WUE). However, Okasha et al. [21] demonstrated that drip irrigation systems with a 7-day interval could improve the yield, nutritional quality, and water use efficiency of beans. Therefore, appropriate irrigation levels can achieve improved crop nutritional quality and increased yield, but it is necessary to comprehensively consider multiple objective factors such as climate, soil type, crop variety, and irrigation water quality to determine the optimal irrigation strategy for high-quality and high-yield crop production. Common bean, characterized by shallow root systems, short growth cycles, and high nutrient demand, requires precise fertilizer management [22]. The application of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) fertilizers represents a key strategy for enhancing the yield and nutritional quality in legume production. Among these essential nutrients, nitrogen is the predominant macronutrient assimilated by common bean, and nitrogen has the strongest influence on crop productivity [23,24]. Nitrogen uptake during the flowering-pod filling stage constitutes approximately 60% of total N [25]. Although rhizobia symbiosis contributes partially to nitrogen acquisition, high crop yield mainly depends on exogenous nitrogen input owing to limited biological nitrogen fixation capacity [26,27,28,29]. Phosphorus fertilizer significantly enhances protein content, increasing stem biomass, pod number, and yield [30,31]. The traditional extensive management practices of agriculture, characterized by excessive water and fertilizer use, not only waste resources but also exacerbate environmental issues such as nitrate leaching and greenhouse gas emissions. Previous research on common beans has primarily focused on single factors like irrigation or fertilization, with limited studies on the coupled effects of both on the plant’s response. Nowadays, with the rapid development of green agriculture, integrated water and fertilizer management technology models have been applied in production practices. Research on comprehensive optimization strategies for water and fertilizer coupling is one of the key measures to improve crop yield and nutritional quality and enhance the ecological environment. Therefore, irrigation and fertilization are effective means to ensure high-quality yields of common beans, but the optimal irrigation amount combined with balanced nutrient application can guarantee yield, improve water and fertilizer use efficiency, and reduce environmental load.

High-latitude and high-altitude regions exhibit lower temperatures, longer daylight hours in summer, less precipitation, and windy-sandy conditions, resulting in soils with lower water-holding and nutrient-retention capacities [32]. Insufficient root water uptake or excessive transpiration rates impair physiological processes in common bean, reducing both pod yield and fresh pod production [33,34,35]. Therefore, it is urgent to explore efficient irrigation and fertilization patterns. Water–fertilizer coupling is achieved by precisely controlling irrigation and fertilizer application rates to optimize spatiotemporal allocation of water and nutrients [36]. Previous research has primarily focused on the application of single evaluation models such as principal component analysis, membership function analysis, and gray relational analysis in agricultural production practice [37]. Every single model has its own emphasis in terms of application scenarios, perspectives, and priorities, but they have limitations in explaining the mechanism of water–fertilizer coupling. To address the limitations of single models, some scholars have proposed combining multiple single models to form comprehensive evaluation models, where the models mutually verify each other, enhancing the robustness of research conclusions [38]. However, comprehensive models are rarely applied in agricultural production practice, and research on the applicability of water–fertilizer coupling optimization strategies under the unique soil-climatic conditions of high-latitude and high-altitude regions is particularly scarce. Therefore, this study introduced a comprehensive model for the first time to evaluate the applicability of water and fertilizer coupling optimization strategies in high-latitude and high-altitude cold climate regions.

The present study employs entropy-weighted supplemental irrigation scheduled by real-time soil moisture monitoring to establish irrigation scheduling, which aims to formulate an optimized irrigation and fertilization strategy and improve water–fertilizer use efficiency and economic benefits in high-latitude and high-altitude regions by coupling the irrigation with fertilizer application rates. The research contents include (1) identifying the interactions between fertilization and irrigation practices on the yield, nutritional quality, WUE, and fertilizer partial factor productivity (PFP) of common bean pods and (2) establishing efficient water and fertilizer management modes suitable for common bean pod production with high yield and nutritional quality in high-latitude and high-altitude regions, using a different combination evaluation model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Site and Materials

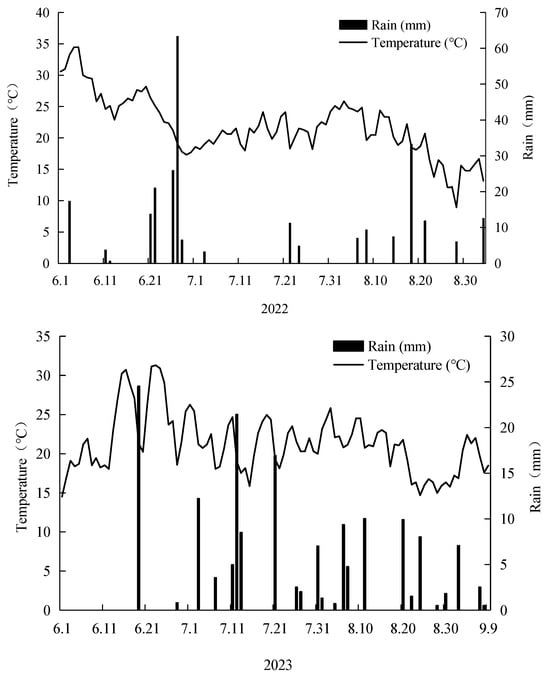

The two-year (2022–2023) field experiment was conducted at the Zhangbei Experimental Station (41°10′25″ N, 114°51′48″ E; elevation: 1407 m), Hebei Agricultural University, Zhangbei County, Zhangjiakou City, Hebei Province, China. The experimental site has a typical cold temperate semi-arid continental monsoon climate with sufficient sunshine and pronounced diurnal temperature differences. The average annual temperature is 10.1 °C, with the highest temperature of 33.4 °C and the lowest temperature of −34.8 °C. The frost-free period is 105 days, with an average annual precipitation of about 400 mm, mainly concentrated from June to September, and a multi-year average evaporation rate of 850–1200 mm. Growing-season precipitation and temperature were obtained from the historical records of the experimental site meteorological station, as shown in Figure 1. The soil type at the experimental site is Kastanozems, and the basic physical and chemical properties of the soil (0–20 cm soil layer) before planting are shown in Table 1. The common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivar ‘Lv’ao 707’ (This variety has the advantages of high purity, early marketing, and flat and straight commercial pods. Medium and early maturing and creeping, the plant grows vigorously, the branching power is strong, the first inflorescence is low node position, there are many inflorescences, the pod grafting power is strong, and the yield potential is great. The manufacturer is Inner Mongolia Luao Seed Industry Co., Ltd. Baotou, China) was used, with fertilizers including urea (46% N) and compound fertilizers, Jinsan’an (N−P2O5−K2O: 18−18−18) and stanley (N−P2O5−K2O: 18−5−27), and potassium sulfate (50% K2O), all commercially sourced.

Figure 1.

Rainfall amount and temperature during the common beans growing seasons of 2022 and 2023.

Table 1.

Basic physical and chemical properties of the soil (0–20 cm) in the experimental plots.

2.2. Experimental Design

Six treatments were established in the 2022 experiment, with irrigation rates of 100% FC (W1), 90% FC (W2), 80% FC (W3), 70% FC (W4), 60% FC (W5), and 50% FC (W6). Each treatment was replicated three times, resulting in a total of 18 plots, with each plot covering an area of 40 m2 (8.0 m × 5.0 m). The irrigation rate was quantified volumetrically using flow meters. The irrigation water source was groundwater. Common beans were irrigated five times throughout their growth period. Pre-planting irrigation was administered on 4 June 2022 with consistent application depth (25 mm) for all treatment groups. From 4 June to 15 July 2022, no water gradient treatments were applied to prevent seedling stress. During this period, cumulative rainfall totaled 155.2 mm, meeting crop water requirements. The experimental water gradient protocol commenced on 15 July 2022. Soil moisture content was determined using the drying method, and irrigation was triggered when soil moisture fell below treatment-specific thresholds. During the early growth phase (4 June–28 July 2022), irrigation volumes were calculated using a 0.5 m ridge width to suit the growth of small common bean seedlings. From 10 August 2022, the ridge width was adjusted to 0.75 m for the common bean seedlings’ growth.

All plots received uniform fertilization rates (N−P2O5−K2O: 195−144−192 kg/ha). The basal fertilizer was JinSan’an compound fertilizer applied at 750 kg/ha. Topdressing was used at three stages: (1) pre-flowering and pod-formation stages: 150 kg/ha JinSan’an compound fertilizer and 60 kg/ha urea; (2) flowering and pod-development stage: 195 kg/ha Stanley compound fertilizer; (3) post-flowering and pod-maturation stage: 75 kg/ha Stanley compound fertilizer. The top dressing was fertigated Via a drip irrigation system. The common beans were planted on 5 June 2022 and harvested three times between 12 August and 3 September, 2022.

Based on the experiment in 2022, a two-factor experiment (irrigation and fertilizer application rate) was implemented in 2023, adopting a randomized block design. Nine treatments were designed in the experiment with three replicates each, with individual plot dimensions of 30 m2 (10.0 m × 3.0 m). Three fertilizer (N−P2O5−K2O) gradients were established: F1 (260−192−255 kg/ha), F2 (195−144−192 kg/ha), and F3 (131−97−127 kg/ha). Based on 2022, three irrigation rates were established at percentages of FC: W7 (100% FC), W8 (80% FC), and W9 (60% FC).

Common beans received five irrigation events during the growing season. Pre-planting irrigation was applied on 8 June 2023 with consistent application depth (25 mm) for all treatment groups. From 8 June to 17 July 2023, no water gradient treatments were applied to prevent seedling stress. During this period, cumulative rainfall (75.9 mm) meets crop water requirements. The experimental water gradient protocol commenced on 17 July 2023. Soil moisture content was determined using the drying method, and irrigation was triggered when soil moisture fell below treatment-specific thresholds. During the early growth phase (8 June–29 July 2023), irrigation volumes were calculated using a 0.5 m ridge width to suit the growth of small common bean seedlings. From 7 August 2023, the ridge width was adjusted to 0.75 m for the common bean seedlings’ growth. The common beans were planted on 8 June 2023 and harvested five times between 3 August and 8 September 2023.

The two-year experiment maintained consistent agronomic practices (planting configuration, management protocols, and fertilizer formulations). Potassium sulfate was used to supplement the potassium deficiency in the 2023 trial. The subsurface drip irrigation (SSDI) system delivered fertilizers in three phases: an initial 25% clear water, 50% fertilizer solution, and final 25% clear water flushing to optimize root-zone delivery. Each plot was equipped with flow meters recording irrigation timing and amounts. The SSDI system comprised a centrifugal pump, labyrinth-channel emitters (16 mm diameter, 2 L/h flow rate, 100 cm spacing), a fertilizer injector, and 0.01 mm black polyethylene mulch. Common beans were mechanically ridged (100 cm spacing, 25 cm ridge depth) and direct-seeded 3 cm deep, 10 cm from ridge edges, at a density of 33,000 plants/ha. Pre-plant irrigation (25 mm) ensured uniform emergence, with supplemental irrigation volumes calculated using gravimetric soil moisture monitoring and water balance principles. The irrigation plan is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The common bean irrigation rate per plot for 2022 and 2023.

2.3. Measurements and Calculations

2.3.1. Soil Moisture Content

At intervals of about every 10 days during the common bean plant’s growth period, the soil moisture content from 0 to 80 cm is measured using the drying method in 10 cm layers, a total of eight layers, and three sampling points are randomly selected for each treatment.

- (1)

- Irrigation rate (I, m3) was calculated as follows [39]:

- (2)

- Evapotranspiration (ET, mm) was calculated as follows using the water balance method [40]:

- (3)

- Water use efficiency (WUE, kg/m3) was calculated as follows [41]:

- (4)

- Soil water storage (SWS, mm) was calculated as follows:

2.3.2. Fresh Pod Yield and Nutritional Quality

During the harvest, pick the fresh pods of common beans from each plot that have not bloomed and have a pod width of ≥1.5 cm (actual production commodity pod collection standards), and weigh them to determine their yield. The yield of the entire planting was then calculated based on the yield of each plot.

In the peak fruiting period, randomly select 15 pole beans from each community for whole plant sampling, and mix and crush the samples for nutritional quality determination. Vitamin C (VC) is determined by the 2,6-dichlorophenol titration method (fresh sample); soluble protein (SP) is determined by the Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 staining method; crude fiber (CF) is determined by the acid-base digestion method; nitrate content (NC) is determined by the ultraviolet spectrophotometric method; and soluble solids content (SSC) is measured using the PAL-1 digital sweetness tester (Atago, Tokyo, Japan) [21].

2.3.3. Fertilizer Partial Factor Productivity (PFP, kg/kg) Was Calculated as Follows [42]:

2.4. Comprehensive Evaluation

2.4.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is a statistical method that reduces the dimensionality of high-dimensional data through linear transformation while retaining the most significant variance information in the data and was used to integrate multiple agronomic, physiological, and quality indicators into composite treatment scores.

Perform centralized processing on the original data matrix, calculate the covariance matrix of the standardized data, perform eigenvalue decomposition on the covariance matrix, obtain the eigenvalues and their corresponding eigenvectors, select the eigenvectors corresponding to the top k largest eigenvalues, and calculate the contribution rate of each principal component [37].

2.4.2. Membership Function Method (MFM)

MFM indicators with different properties and different scales to obtain the subordination degree values of each indicator between 0 and 1. Calculate the subordination degree values of each indicator, the weight, and the comprehensive score for each treatment [37].

2.4.3. Weighted TOPSIS Method (W-TOPSIS)

The W-TOPSIS method ranks all solutions by calculating the distance of each actual solution from the positive ideal solution and the negative ideal solution. A solution that is closer to the positive ideal solution and farther from the negative ideal solution demonstrates better overall performance.

Perform data normalization processing, calculate the normalized matrix and weight it, calculate the positive ideal distance D+ and the negative ideal distance D− between each target value and the ideal point, as well as the relative closeness Ci of each target to the ideal point, based on the weighted matrix [37].

2.4.4. Gray Relational Analysis Method (GRA)

Gray relational analysis is primarily used in agricultural science to identify key factors affecting crop yield or nutritional quality and to optimize strategies or make agronomic decisions based on their correlation with target traits. Perform dimensionless processing on the original data, and calculate the correlation coefficient, degree of relevance, weighted relevance, and rank by order [37].

2.4.5. Rank-Sum Ratio (RSR)

The RSR (Rank-Sum-Ratio) method comprehensively ranks and categorizes irrigation and fertilization programs using multiple indicators, thereby selecting the optimal options or classifying them into superior and inferior tiers.

2.4.6. Comprehensive Evaluation Model

Methods such as PCA, MFM, W-TOPSIS, GRA, and RSR are used to establish a comprehensive evaluation model. The higher the comprehensive score, the better the synergistic effect of this water–fertilizer combination [37].

2.5. Data Analysis

All experimental data were calculated and plotted using Microsoft Excel and Origin 2024 software, and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22 software (v22.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Multiple comparisons were made using the LSD method, and differences between treatments were significant at p < 0.05 and extremely significant at p < 0.01; statistical comparisons were conducted within each year.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Water–Fertilizer Coupling Regulation on Water Consumption During the Growth Period of Common Bean

Water application, consumption, and soil storage throughout the common bean growth period were significantly influenced by the target field capacity (FC) (Table 3). In 2022, W1 treatment showed the highest irrigation rate, while W2~W6 showed 14.61% to 82.36% reductions relative to W1. Actual evapotranspiration was highest in W1, exceeding other treatments by 7.46%~73.59% and decreasing gradually with lower FC. Soil storage water of the W1 treatment was significantly higher than that in the W5 and W6 treatments, but it showed no significant difference from the remaining treatments. In 2023, W8 and W9 applied 31.38% and 63.67% less water than that in W7, respectively. Actual evapotranspiration showed dependence on FC but was unaffected by fertilization rates, with the highest value in W7F1. The soil water storage was the highest in W7F3 and the lowest in W9F1, while soil water storage increased with decreasing fertilizer rate at constant FC levels.

Table 3.

Irrigation rate and water consumption of common bean during the growth period.

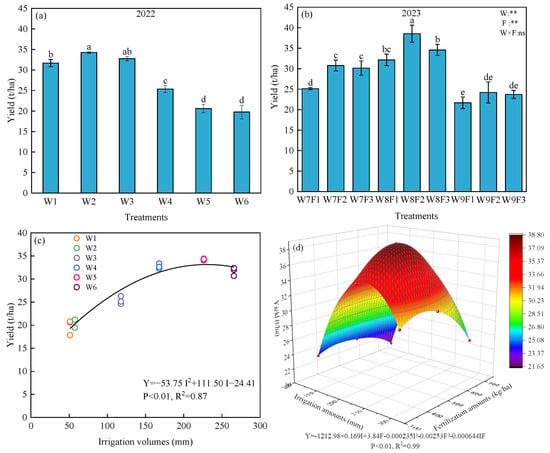

3.2. Effect of Water–Fertilizer Coupling Regulation on Fresh Common Bean Yield

The 2022–2023 experiments showed that high irrigation volume does not necessarily result in high fresh common bean yield (Figure 2). In 2022, the highest yield of common beans occurred at 90% FC (W2: 34.29 t/ha), showing no significant difference from W3 and an increase of 4.67% to 73.53% compared to other treatments. In 2023, common bean yield was significantly affected by irrigation and fertilization, but no significant interaction was observed. W8F2 produced maximum yield, exceeding other treatments by 11.48~77.68%. It can be seen that the yield of W8F2 in 2023 is comparable to that under similar irrigation treatment (W3) in 2022, indicating that the optimal treatment has stability under interannual variability. In addition, this study found that common bean yield is related to irrigation and fertilization amounts in a quadratic parabola relationship (Figure 2). By taking irrigation and chemical fertilizer use as independent variables and common bean yield as the dependent variable, a regression model was constructed and fitted using data from 2022 and 2023. The F-value for the 2022 model was 45.64, p < 0.01, with an R2 value of 0.87; the F-value for the 2023 model was 38.38, p < 0.01, with an R2 value of 0.99, indicating a good fit of the model. The regression model illustrated that increasing irrigation and fertilizer application benefited common beans’ high yield, but yield began to decline once it exceeded the critical point. All those further illustrated that the W8F2 treatment was optimal for the common bean.

Figure 2.

Effects of irrigation and fertilization on common bean yield and regression model of its relationship with yield from 2022 to 2023. (a–d) represent 2022 yield, 2023 yield, fitting relationship between yield and irrigation, and regression models of irrigation, fertilization, and yield, respectively. Note: Different lowercase letters in the same column indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05). W, F, and W × F mean effects of irrigation, fertilizer, or water–fertilizer interaction by two-way ANOVA analysis, with ** indicating extremely significant at the 1% level (p < 0.01). The ns means no significant difference.

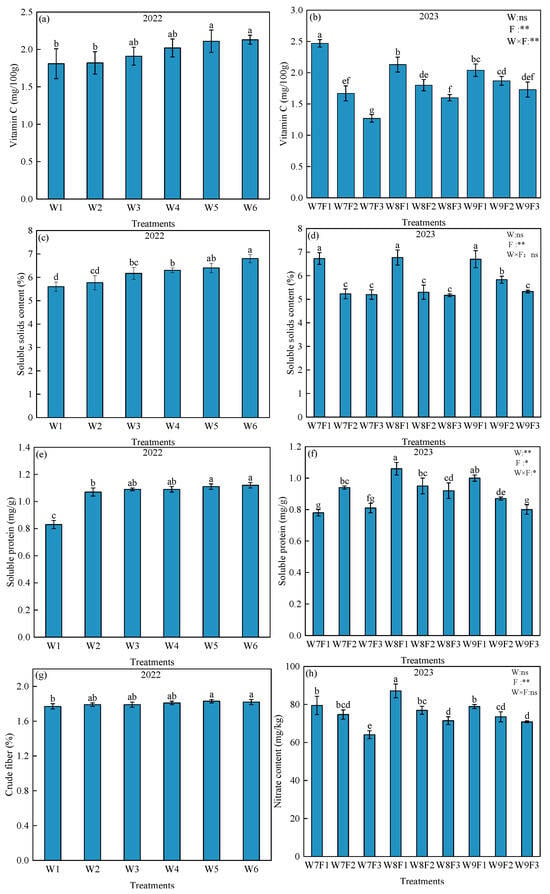

3.3. Effect of Water–Fertilizer Coupling Regulation on Common Bean Quality

In 2022, vitamin C (VC), soluble solids content (SSC), soluble protein (SP), and crude fiber (CF) in common beans increased with the reduction in irrigation rate (Figure 3). The nutritional quality indicators of the W5 and W6 treatments were the best, showing no significant difference between them, but both were higher than those in the other treatments. In 2023, the fertilizer rate had a substantial effect on the content of VC, SSC, SP, and nitrate content (NC) in common beans, while the interaction of irrigation and fertilizer application rates only had a significant effect on the SP and VC content. The VC content in common beans increased with the fertilizer application rates, with W7F1 being the highest at 2.47 mg/100 g. The SSC and NC increased with the fertilizer rate increasing under the same irrigation rate. The SP content exhibited a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing with the decrease in fertilization amount, with the W8F1 treatment being the highest but not significantly different from the W7F2, W8F2, and W9F1 treatments.

Figure 3.

Effects of irrigation and fertilization on the nutritional quality of common beans. (a–h) represent vitamin C content in 2022, vitamin C content in 2023 (fresh weight), soluble solids content in 2022, soluble solids content in 2023, soluble protein content in 2022, soluble protein content in 2023, crude fiber content in 2022, and nitrate content in 2023, respectively. Note: Different lowercase letters in the same column indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05). W, F, and W × F mean effects of irrigation, fertilizer, or water–fertilizer interaction by two-way ANOVA analysis, with * indicating statistical significance at the 5% level (p < 0.05) and ** indicating extremely significant at the 1% level (p < 0.01). The ns means no significant difference.

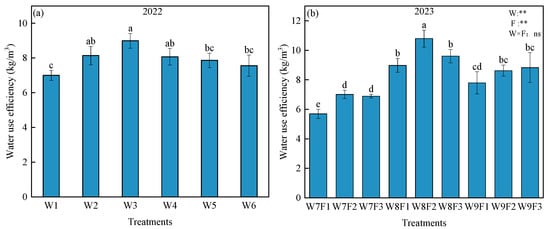

3.4. Effect of Water–Fertilizer Coupling Regulation on Water Use Efficiency

Water use efficiency in 2022 responded solely to FC levels, whereas in 2023 it was influenced by both FC and fertilization rates (Figure 4). In 2022, the WUE peaked at 80% FC (W3), exceeding other treatments by 10.44%~28.43%, while W1 exhibited the lowest values. The 2023 trial revealed significant main effects of irrigation and fertilization on WUE, though their interaction remained non-significant. Post hoc analysis revealed that the W8F2 treatment achieved the highest WUE, demonstrating 89.63% higher WUE than W7F1, surpassing W8F1 and W8F3 by 20.20% and 12.40%, respectively. Under the same fertilization conditions, W8 maintained significantly higher WUE than W7 and W9.

Figure 4.

Effects of irrigation and fertilization on WUE of common beans. (a,b) represent water use efficiency in 2022 and water use efficiency in 2023, respectively. Note: Different lowercase letters in the same column indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05). W, F, and W × F mean effects of irrigation, fertilizer, or water–fertilizer interaction by two-way ANOVA analysis, with ** indicating extremely significant at the 1% level (p < 0.01). The ns means no significant difference.

3.5. Effect of Water–Fertilizer Coupling Regulation on Fertilizer Partial Factor Productivity

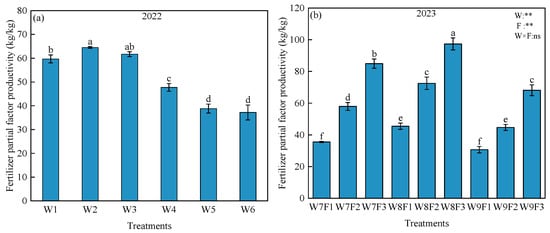

In 2022, fertilizer partial factor productivity peaks at an intermediate FC (90%), with slightly lower but non-significant values at 80% FC, and decreases at both higher and lower FC levels. At 90% FC, PFP reached its maximum value of 64.52 kg/kg, but there was no significant difference in PFP at 80% FC. The PFP of the common bean was significantly affected by irrigation rate and fertilization amount (Figure 5). In 2023, the PFP of the W8F3 treatment achieved a maximum value, exceeding that of other treatments by 14.70% to 217.51%. Under the same field water-holding conditions, the PFP decreases with increasing fertilizer application, and it is high at low fertility levels. Under the same fertilizer application conditions, the PFP shows a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing with increasing water application, reaching its highest value at 80% FC.

Figure 5.

Effects of irrigation and fertilization on PFP of common beans. (a,b) represent fertilizer partial factor productivity in 2022 and fertilizer partial factor productivity in 2023, respectively. Note: different lowercase letters in the same column indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05). W, F, and W × F mean effects of irrigation, fertilizer, or water–fertilizer interaction by two-way ANOVA analysis, with ** indicating extremely significant at the 1% level (p < 0.01). The ns means no significant difference.

3.6. Multi-Objective Decision-Making and Evaluation Based on the Overall Difference Combination Evaluation Model

PCA, MFM, W-TOPSIS, GRA, and RSR are all widely used comprehensive evaluation methods for crops. Based on the data of common bean production, including pod yield, PFP, WUE, ET, VC, SSC, SP, and NC. It can be seen from Table 4 that different evaluation methods do not rank the various fertilization and irrigation measures consistently. At the same time, the same method showed great differences in the evaluation of similar treatments between the two years. The comprehensive index of common beans was evaluated using the PCA, MFM, W-TOPSIS, GRA, and RSR. The results showed that the results and rankings of the same treatment under different comprehensive evaluation methods varied. W3 and W2 ranked first and second, respectively, in 2022, while W8F1 and W8F2 ranked first and second, respectively, in 2023.

Table 4.

Results of multi-objective decision-making and evaluation based on the comprehensive evaluation model. Note: PCA, MFM, W-TOPSIS, GRA, and RSR mean Principal component analysis, Membership function method, Weighted TOPSIS method, Gray Relational Analysis method, Rank-sum ratio, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Water–Fertilizer Optimization Strategies on Yield and Quality of Common Beans

Regression models and yield data from this study in 2022 and 2023 indicated a quadratic relationship between irrigation rate and crop yield: excessive or insufficient irrigation and fertilization levels reduce crop yield. This is mainly because when FC was low, water stress induced morphological, physiological, and biochemical changes in plants, damaging their normal physiological activities and decreasing common bean yield [43]. Low irrigation rates could decrease chlorophyll content in common bean leaves, directly affecting biomass accumulation [44]. High FC led to excessive root-zone water, which hindered aeration, caused plant physiological abnormalities, and reduced microbial activity. These effects resulted in losses of nutrients and water available to plants, ultimately decreasing yield [45]. Besides water, fertilizers significantly impact plant growth and yield. In this study, both irrigation and fertilization application rates significantly impacted common bean yield. The yield increased initially and then decreased with increasing irrigation and fertilization application rates, and excessive or insufficient levels of either input reduce yield [46,47]. Under conditions of water or nutrient deficiency, root nutrient uptake is limited. Over-irrigation induces local root hypoxia and damage [48,49]. Over-fertilization promotes excessive vegetative growth, inhibiting fruit formation. High irrigation and fertilization application rates not only enhance nutrient leaching but also cause ecological imbalance due to nutrient overload, deteriorating the plant growth environment and inducing yield decline [50,51]. The study by Zhong et al. [52] demonstrated that irrigation, fertilization, and their interactions significantly affected pumpkin yield, which differed slightly from the findings of the present study. The water–fertilizer coupling had no significant effect on common bean yield. This was because the plants used different mechanisms to absorb water and nutrients under drought and sufficient water conditions. However, the exact reasons for this observation need more research.

The nutritional quality of common beans is also one of the important indicators affecting their commerciality. In this study, as irrigation decreased, common bean SP content increased, with the highest value (1.12 mg/g) observed in the W6 treatment. This phenomenon differs from the case where underwater stress, nitrogen allocation, and fixation decrease, reducing legume protein content [53,54]. This may be due to water stress limiting seed size without restricting nitrogen transport, leading to nitrogen accumulation in pods and increased common bean SP content. Additionally, in 2022, VC, SSC, and CF also increased with the reduction in irrigation. This resulted from water stress inducing plants to regulate metabolic activities by breaking down polysaccharides into monosaccharides, increasing SSC, and accelerating the conversion of organic acids such as malic acid, citric acid, and ascorbic acid, thereby improving common bean nutritional quality [55,56]. Common bean nutritional quality is also closely related to fertilization, with the protein content exhibiting a linear increase with nitrogen fertilizer application [57]. Under different fertilization levels, common bean VC content responded differently to irrigation: under low and medium fertilization, the VC content decreased with increased irrigation [58], because excessive irrigation dilutes fruit nutrients, negatively impacting fruit quality [59]. Under high fertilization, VC content increased with irrigation, possibly due to the synergistic effect of high fertilization and irrigation, which enhances the photosynthetic enzyme activity and chlorophyll synthesis, promotes common bean reactive oxygen metabolism, and boosts VC content. Additionally, the NC increased with the fertilizer rate increasing under the same irrigation rate. For example, long-term intake of nitrates may increase the risk of developing digestive system tumors such as gastric cancer and esophageal cancer.

4.2. Effect of Water–Fertilizer Optimization Strategies on WUE and PFP

This study demonstrated that the irrigation rates significantly influenced common bean WUE, which increased initially and then declined with increasing irrigation. Across the two-year experiments, the highest WUE occurred at 80% FC. Bozkurt et al. [60] confirmed that, at 55 mm irrigation, WUE reached 5.1 kg/m3, whereas it dropped to 4.0 kg/m3 under the highest irrigation (I = 328 mm). Higher irrigation rates increased water evaporation and loss. The amount of water needed to maintain high field capacity (FC) was greater than that needed to increase common bean yield. As a result, higher water consumption by common beans led to lower WUE [61]. Fertilization level also significantly influenced common bean WUE, with a more pronounced effect under low and medium irrigation rates. In this study, fertilizer application had a stronger impact on WUE under low or medium irrigation conditions, possibly because low or medium irrigation rates combined with fertilization did not substantially reduce yield. In contrast, high irrigation rate was no longer a limiting factor for increased production of common beans, diminishing the marginal yield benefit of fertilization. Excessive water and fertilizer might even induce nutrient leaching and excessive vegetative growth, lowering WUE.

At the same irrigation rate, the PFP of low fertilization treatment exceeded that of medium and high fertilization, though medium fertilization yielded higher than low or high fertilization treatments. This phenomenon represents a survival adaptation strategy in low-nutrient environments. By improving metabolic efficiency, plants maintained basic growth. However, under limited resource conditions, they struggled to exceed yield thresholds. Therefore, a higher PFP did not always lead to higher yield [62]. Additionally, PFP exhibited a unimodal response to increasing irrigation, peaking at the W8 irrigation rate under each fertilization treatment. This occurred because excessive irrigation induced root-zone nutrient leaching, which impaired root nutrient uptake and thereby reduced PFP [63,64].

4.3. Evaluating the Adaptability of Water–Fertilizer Optimization Strategies and Comprehensive Evaluation Model in Common Bean Cultivation at High-Altitude and High-Latitude Regions

This study employs a comprehensive evaluation model to assess the fertilizer-water optimization strategies. The model integrates multi-dimensional information, coordinates conflicts between different evaluation methods, and generates robust ranking results. The results indicate that there is no obvious pattern in the rankings of different treatments across various evaluation methods. However, the treatments at 80% field water holding capacity (W8F1, W8F2) proved to be the most stable and delivered the best overall performance, indicating an optimal synergistic balance. However, the two-year trial results show that appropriate irrigation amounts are beneficial for runner bean growth and improve water–fertilizer use efficiency, leading to higher overall rankings and revealing the threshold effects and intrinsic interaction mechanisms within the fertilizer-water system. The maximum comprehensive evaluation based on consensus provides key thresholds for management, offering both theoretical insights and direct practical guidance for optimizing field practices.

In high-latitude and high-altitude regions, water-fertilization coupling optimization strategies are valued for their ability to overcome key environmental challenges. These areas often have low soil temperatures, which limit nutrient availability. The growing season is short, and there is not enough accumulated heat for optimal plant growth. This restricts biomass production. Additionally, rainfall is unevenly distributed, and strong solar radiation increases water loss. As a result, water-use efficiency is reduced. Nationally, Chinese common bean yields averaged 28.70 t/ha and 28.96 t/ha in 2022 and 2023, respectively, under fertilizer application rates of 538.50 kg/ha and 531.30 kg/ha [65]. In this study, optimized water-fertilization coupling treatments exceeded these national averages by 34.29% and 35.09% in 2022 and 2023. Notably, at comparable fertilization rates in 2023, the PFP of common beans increased by up to 33.13% relative to the national benchmark. These results demonstrate that the optimization strategies significantly enhance yield and resource-use efficiency by modifying soil hydraulic properties, optimizing rhizosphere nutrition, mitigating region-specific evaporative stress, and improving nutrient activation kinetics in cold soils [66,67,68,69]. While long-term effects require further validation, current data substantiate water-fertilization coupling as an effective technical pathway for overcoming agricultural constraints in these marginal environments.

5. Conclusions

This study aims to analyze the effects of different irrigation amounts and fertilizer coupling on the yield, nutritional quality, water use efficiency, and fertilizer use efficiency of common beans. The results show that the highest yield and water use efficiency occur at 80–90% field capacity and a fertilizer application rate of N−P2O5−K2O: 195−144−192 kg/ha. The best quality indicators of common beans appear at 50–60% field capacity. Additionally, the highest fertilizer partial factor productivity was observed at 80% field capacity. Simply increasing the irrigation amount does not effectively improve fertilizer use efficiency; instead, it wastes water resources and even exacerbates fertilizer leaching and loss. CEM analysis of common bean yield, quality, water use efficiency, fertilizer partial factor productivity, and feasibility over two years indicates that the suitable irrigation rate for common beans in high-latitude and high-altitude regions is 80–90% field capacity, i.e., 1009.95–1333.46 m3/ha, with fertilizer application rates of F1–F2, N: 195–260 kg/ha, P2O5: 144–192 kg/ha, and K2O: 192–255 kg/ha. In summary, this study obtained an irrigation and fertilization scheme suitable for common bean production in high-latitude and high-altitude regions, providing valuable technical support for high-yield, high-quality, and efficient irrigation and fertilization management in similar ecological regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W.; methodology, C.A. and Z.W.; software, H.W. and X.W.; formal analysis, S.J.; investigation, R.S.; data curation, B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L. and S.L.; writing—review and editing, X.C. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Projects (2022YFE0199500), the Demonstration Program of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences (20191201), the Key Research and Development Projects of Hebei Province (21327005D), Hebei North University Doctoral Research Initiation Fund (BSJJ202429), and Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department (QN2023202).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PFP | Fertilizer partial factor productivity |

| FC | Field capacity |

| WUE | Water use efficiency |

| VC | Vitamin C |

| SP | Soluble protein |

| SSC | Soluble solids content |

| NC | Nitrate content |

| SSDI | Subsurface drip irrigation |

| I | Irrigation rate |

| SWC | Soil water content |

| ET | Evapotranspiration |

| SWS | Soil water storage |

| CF | Crude fiber |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| W-TOPSIS | Weighted TOPSIS method |

| GRA | Gray Relational Analysis method |

| RSR | Rank-sum ratio |

| MFM | Membership function method |

References

- Kutoš, T.; Golob, T.; Kač, M.; Plestenjak, A. Dietary fibre content of dry and processed beans. Food Chem. 2003, 80, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiq, M.; Ravi, R.; Harte, J.B.; Dolan, K.D. Physical and functional characteristics of selected dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) flours. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P. Common bean improvement in the twenty-first century. Springer Sci. Bus. Media 1999, 7, 405. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Lucero, E.; Rodríguez-Hernández, A.A.; Ortega-Amaro, M.A.; Jiménez-Bremont, J.F. Differential expression of genes for tolerance to salt stress in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 32, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.D.; Brick, M.A.; McGinley, J.N.; Thompson, H.J. Chemical composition and mammary cancer inhibitory activity of dry bean. Crop Sci. 2009, 49, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouhouche, B.; Ruget, F.; Delécolle, R. Effects of water stress applied at different phenological phases on yield components of dwarf bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Agronomie 1998, 18, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, P.H.; Ranalli, P. Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Field Crops Res. 1997, 53, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.G.D.; Ribeiro, R.V.; Oliveira, R.F.D.; Pimentel, C. Gas exchange and yield response to foliar phosphorus application in Phaseolus vulgaris L. under drought. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 16, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mejía, E.G.; Martínez-Resendiz, V.; Castaño-Tostado, E.; Loarca-Piña, G. Effect of drought on polyamine metabolism, yield, protein content and in vitro protein digestibility in tepary (Phaseolus acutifolius) and common (Phaseolus vulgaris) bean seeds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2003, 83, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutraa, T.; Sanders, F.E. Influence of water stress on grain yield and vegetative growth of two cultivars of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2001, 187, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathobo, R.; Marais, D.; Steyn, J.M. The effect of drought stress on yield, leaf gaseous exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence of dry beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 180, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asemanrafat, M.; Honar, T. Effect of water stress and plant density on canopy temperature, yield components and protein concentration of red bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. cv. Akhtar). Int. J. Plant Prod. 2017, 11, 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Sezen, S.M.; Yazar, A.; Akyildiz, A.; Dasgan, H.Y.; Gencel, B. Yield and quality response of drip irrigated green beans under full and deficit irrigation. Sci. Hortic. 2008, 117, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Veneklaas, E.; Polania, J.; Rao, I.M.; Beebe, S.E.; Merchant, A. Field drought conditions impact yield but not nutritional quality of the seed in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, S.E.; Rao, I.M.; Blair, M.W.; Acosta-Gallegos, J.A. Phenotyping common beans for adaptation to drought. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Sharma, V.; Heitholt, J. Dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) growth and yield response to variable irrigation in the arid to semi-arid climate. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efetha, A.; Harms, T.; Bandara, M. Irrigation management practices for maximizing seed yield and water use efficiency of Othello dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in southern Alberta, Canada. Irrig. Sci. 2011, 29, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizana, C.; Wentworth, M.; Martinez, J.P.; Villegas, D.; Meneses, R.; Murchie, E.H.; Pinto, M. Differential adaptation of two varieties of common bean to abiotic stress: I. Effects of drought on yield and photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Desoky, E. Influencing of water stress and micronutrients on physio-chemical attributes, yield and anatomical features of Common Bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Egypt. J. Agron. 2017, 39, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Shahrokhnia, M.A. The effect of irrigation interval on yield, yield components and water productivity of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) cultivars in a semi-arid area. Ann. Biol. 2020, 36, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Okasha, E.M.; El-Metwally, I.M.; Taha, N.M. Impact of drip and gated pipe irrigation systems, irrigation intervals on yield, productivity of irrigation water and quality of two common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L) cultivars in heavy clay soil. Egypt. J. Chem. 2020, 63, 5103–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, R.D.; Araujo, A.P. Variability of root traits in common bean genotypes at different levels of phosphorus supply and ontogenetic stages. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2014, 38, 1170–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscaro, G.A.; Freitas Junior, N.A.D.; Soratto, R.P.; Kikuti, H.; Goulart Junior, S.A.R.; Aguirre, W.M. Nitrogen sidedressing and molybdenum leaf application on irrigated common bean in cerrado soil. Acta Sci. Agron. 2011, 33, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascente, A.S.; Carvalho, M.D.C.S.; Melo, L.C.; Rosa, P.H. Nitrogen management effects on soil mineral nitrogen, plant nutrition and yield of super early cycle common bean genotypes. Acta Sci. Agron. 2017, 39, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soratto, R.P.; Fernandes, A.M.; Santos, L.A.D.; Job, A.L.G. Nutrient extraction and exportation by common bean cultivars under different fertilization levels: I-macronutrients. Rev. Bras. Ciência Solo 2013, 37, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Campo, R.J.; Mendes, I.C. Benefits of inoculation of the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) crop with efficient and competitive Rhizobium tropici strains. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2003, 39, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korir, H.; Mungai, N.W.; Thuita, M.; Hamba, Y.; Masso, C. Co-inoculation effect of rhizobia and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on common bean growth in a low phosphorus soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, E. The rhizobium/Bradyrhizobium-legume symbiosis. In Molecular Biology of Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, M.W.; Grusak, M.A.; Pinto, E.; Gomes, A.; Ferreira, H.; Balázs, B.; Iannetta, P. The biology of legumes and their agronomic, economic, and social impact. Plant Fam. Fabaceae 2020, 7, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bildirici, N.; Oral, E. The effect of phosphorus and zinc doses on yield and yield components of beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Van-gevaş, Turkey. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2020, 18, 2539–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Baligar, V.C. Growth, yield and yield components of dry bean as influenced by phosphorus in a tropical acid soil. J. Plant Nutr. 2016, 39, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Q.; Tong, B.X.; Jia, M.Y.; Xu, H.S.; Wang, J.Q.; Sun, Z.M. Integrated management strategies increased silage maize yield and quality with lower nitrogen losses in cold regions. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1434926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, K.; Schwember, A.R.; Machado, D.; Ozores-Hampton, M.; Gil, P.M. Physiological and yield responses of green-shelled beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) grown under restricted irrigation. Agronomy 2021, 11, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Noemani, A.A.; Aboellil, A.A.A.; Dewedar, O.M. Influence of irrigation systems and water treatments on growth, yield, quality and water use efficiency of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2015, 8, 248–258. [Google Scholar]

- Abebe, A.; Tsige, A.; Work, M.; Enyew, A. Optimizing irrigation frequency and amount on yield and water productivity of snap bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in NW Amhara, Ethiopia: A case study in Koga and Ribb irrigation scheme. Cogent Food Agric. 2020, 6, 1773690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, D.F.; Chen, H.Q.; Qin, A.Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Duan, A.W.; Wang, X.P.; Liu, Z.D. Optimizing irrigation and N fertigation regimes achieved high yield and water productivity and low N leaching in a maize field in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 301, 108945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, M.; Fu, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Shao, Y.; Wang, X. Coupling effects of irrigation amount and fertilization rate on yield, quality, water and fertilizer use efficiency of different potato varieties in Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 287, 108446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Fan, Y.; He, L.; Wang, S. Improving food system sustainability: Grid-scale crop layout model considering resource-environment-economy-nutrition. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 403, 136881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Guo, P.; Wang, Y. Effect of different supplemental irrigation strategies on photosynthetic characteristics and water use efficiency of wheat. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 77, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evaporation Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements; Irrigation and Drainage Paper; FAO-Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, J.E.; Alcon, F.; Diaz-Espejo, A.; Hernandez-Santana, V.; Cuevas, M.V. Water use indicators and economic analysis for on-farm irrigation decision: A case study of a super high density olive tree orchard. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 237, 106074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ierna, A.; Pandino, G.; Lombardo, S.; Mauromicale, G. Tuber yield, water and fertilizer productivity in early potato as affected by a combination of irrigation and fertilization. Agric. Water Manag. 2011, 101, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P.J.; O’Grady, A.P.; Tissue, D.T.; White, D.A.; Ottenschlaeger, M.L.; Pinkard, E.A. Drought response strategies define the relative contributions of hydraulic dysfunction and carbohydrate depletion during tree mortality. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Serna, R.; Kohashi-Shibata, J.; Acosta-Gallegos, J.A.; Trejo-López, C.; Ortiz-Cereceres, J.; Kelly, J.D. Biomass distribution, maturity acceleration and yield in drought-stressed common bean cultivars. Field Crops Res. 2004, 85, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.L.R.; Santana, M.J.; Pizolato Neto, A.; Pereira, M.G.; Vieira, D.D.S. Produtividade de feijão sobre lâminas de irrigação e coberturas de solo. Biosci. J. 2013, 29, 833–841. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C.; Zou, H.; Fan, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Sun, S.; Pulatov, A. Optimizing irrigation amount and fertilization rate of drip-fertigated spring maize in northwest China based on multi-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation model. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 257, 107157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Du, L.; Xing, Z.; Zhang, R.; Li, F.; Zhong, T.; Liu, X. Effects of dual mulching with wheat straw and plastic film under three irrigation regimes on soil nutrients and growth of edible sunflower. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 288, 108453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Lu, X.; Gu, S.; Guo, X. Improving nutrient and water use efficiencies using water-drip irrigation and fertilization technology in Northeast China. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Wang, J.; Mostofa, M.G.; Fornara, D.; Sikdar, A.; Sarker, T.; Jahan, M.S. Fine-tuning of soil water and nutrient fertilizer levels for the ecological restoration of coal-mined spoils using Elaeagnus angustifolia. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; He, Z.; Zhao, W.; Wang, C.; Ma, D. Fine soil texture is conducive to crop productivity and nitrogen retention in irrigated cropland in a desert-oasis ecotone, Northwest China. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. Enhancing soil health and crop yields through water-fertilizer coupling technology. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1494819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Zhang, J.; Du, L.; Ding, L.; Zhang, R.; Liu, X.; Li, X. Comprehensive evaluation of the water-fertilizer coupling effects on pumpkin under different irrigation volumes. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1386109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P. Drought resistance in the race Durango dry bean landraces and cultivars. Agron. J. 2007, 99, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamssi, N.N. Grain yield and protein of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) cultivars under gradual water deficit conditions. Res. J. Environ. Sci. 2011, 5, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardakani, L.G.; Farajee, H.; Kelidari, A. The effect of water stress on grain yield and protein of spotted bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), cultivar Talash. Int. J. Adv. Biol. Biomed. Res. 2013, 1, 940–949. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, M.M.; Alharbi, M.M.; Alsudays, I.M.; Alsubeie, M.S.; Almuziny, M.; Alabdallah, N.M.; Awad-Allah, M. Influence of super-absorbent polymer on growth and productivity of green bean under drought conditions. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soratto, R.P.; Catuchi, T.A.; Souza, E.D.F.C.D.; Garcia, J.L.N. Plant density and nitrogen fertilization on common bean nutrition and yield. Rev. Caatinga 2017, 30, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, H.; Gong, X.; Li, S.; Pang, J.; Chen, Z.; Sun, J. Optimizing irrigation and nitrogen management strategy to trade off yield, crop water productivity, nitrogen use efficiency and fruit quality of greenhouse grown tomato. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 245, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yang, Y.; Tan, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, T.; Yang, L.; Liang, S. Climate-smart drip irrigation with fertilizer coupling strategies to improve tomato yield, quality, resources use efficiency and mitigate greenhouse gases emissions. Land 2024, 13, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, S.; Mansuroglu, G.S. Responses of unheated greenhouse grown green bean to buried drip tape placement depth and watering levels. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 197, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, S.K.; Patel, R.A.; Patel, H.K. Role of irrigation and nitrogen levels on yield, nutrient content, uptake and economics of French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under middle Gujarat condition. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 10, 657–662. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.C.; Yan, F.L.; Fan, X.K.; Li, G.D.; Liu, X.; Lu, J.S.; Ma, W.Q. Effects of irrigation and fertilization levels on grain yield and water-fertilizer use efficiency of drip-fertigation spring maize in Ningxia. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2018, 34, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Xiang, Z.; Ma, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, Q.; Li, P.; Zheng, S. Effect of N fertilizer dosage and base/topdressing ratio on potato growth characteristics and yield. Agronomy 2023, 13, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.J.B.; Zotarelli, L.; Tormena, C.A.; Rens, L.R.; Rowland, D.L. Effects of water table management on least limiting water range and potato root growth. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 186, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (MARA). 2025. Available online: http://zdscxx.moa.gov.cn:8080/nyb/pc/search.jsp (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Nolz, R.; Cepuder, P.; Balas, J.; Loiskandl, W. Soil water monitoring in a vineyard and assessment of unsaturated hydraulic parameters as thresholds for irrigation management. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 164, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Luo, M.; Zhang, T.; Yan, S.; Wang, C.; Dong, Q.G.; Kisekka, I. Organic substitution improves soil structure and water and nitrogen status to promote sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) growth in an arid saline area. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 283, 108320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jin, M.; Zhou, N.; Huang, J.; Jiang, S.; Telesphore, H. Evaluation of evapotranspiration and deep percolation under mulched drip irrigation in an oasis of Tarim basin, China. J. Hydrol. 2016, 538, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, I.; Lv, J.Z.; Yang, L.; Ahmad, S.; Farooq, S.; Zeeshan, M.; Zhou, X.B. Low irrigation water minimizes the nitrate nitrogen losses without compromising the soil fertility, enzymatic activities and maize growth. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).