Abstract

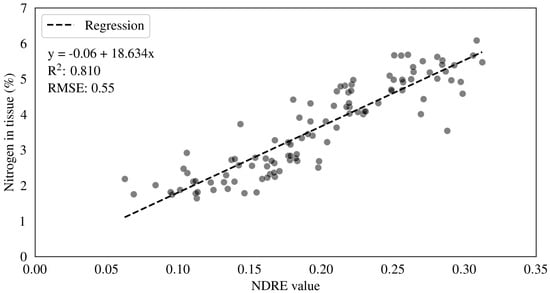

Potatoes are an economically important crop in Virginia, USA, where growers must balance planting dates, nitrogen (N) management, and variable crop prices. Early planting exposes crops to low temperatures that limit growth, whereas late planting increases pest pressure and nutrient inefficiency. This study evaluated the effects of planting dates, N rates, and application timing on potato growth, yield, and pest incidence. We also assessed whether soil physicochemical properties could predict the presence of wireworms and plant-parasitic nematodes (PPNs) using complementary on-farm samples collected across Eastern Virginia between March and July 2023. Three planting dates (early-March, late-March, and early-April) were combined with five N rates (0, 146, 180, 213, and 247 kg N·ha−1) under early- and late-application regimes. We collected data on plant emergence, flowering time, soil nitrate, biomass, tuber yield, pest damage, and UAS-derived metrics. Results showed that late-March planting with 180 kg N·ha−1 achieved the highest gross profit while maintaining competitive yields (25.06 Mg·ha−1), representing 24% and 6% improvements over traditional practices, respectively. Early-April planting produced the largest tubers, with a mean tuber weight 19% higher than the other planting dates. The Normalized Difference Red Edge Index (NDRE) was strongly correlated with N content in plant tissue (R2 = 0.81; r ≈ 0.90), and UAS-derived plant area accurately predicted tuber yield 4–6 weeks before harvest (R2 = 0.75). Wireworm damage was significantly higher in early-March plantings due to delayed insecticide application, while soil nitrate concentration and percent H saturation were identified as key predictors of wireworm presence. Although less effectively modeled due to limited sample size, PPN occurrence was influenced by potassium saturation and soil pH. Aligning planting dates and nitrogen applications with crop phenology, using growing degree days (GDD), enhanced nitrogen management, and yield prediction.

1. Introduction

Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) are the third-most-valuable vegetable crop in the USA, contributing billions of dollars annually to the agricultural sector. Virginia’s Eastern Shore plays a crucial role in this context, offering unique climatic and soil conditions that are ideal for potato production. However, these conditions pose significant challenges for optimizing planting dates, nutrient management, and pest control. The interactions among these factors directly influence crop yield, tuber quality, and environmental sustainability, underscoring the need for improved, integrated production strategies. Planting dates are a fundamental variable in potato cropping systems, dictating the crop’s physiological development in response to environmental conditions. Early planting typically captures high early-season market prices, but can present substantial risks in the Eastern USA [1]. Low soil and air temperatures during this period can reduce germination rates and delay plant emergence, thereby limiting early growth and yield potential [2,3]. Temperatures below 8 °C can reduce photosynthesis in potatoes, leading to reduced biomass accumulation [4]—conversely, late planting benefits from higher temperatures and accumulation of growing degree days (GDD), which accelerate emergence and canopy closure. However, late planting exposes crops to increased evapotranspiration and greater pest pressures, particularly during the tuber development phase [5,6]. Warmer, wetter conditions during this period have been linked to higher incidences of soil-borne diseases, such as Rhizoctonia solani [7,8,9]. These trade-offs highlight the complexity of determining optimal planting windows, as they require balancing physiological, environmental, and economic considerations. Nitrogen (N) is a key macronutrient that directly affects the growth, productivity, and quality of potatoes [10]. Application rate and timing are crucial components of the 4R nutrient stewardship. This nutrient management approach focuses on the rate, timing, source, and placement of nutrients, as well as their interdependencies [11].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that suboptimal N application rates can reduce tuber yield and quality, while excessive N application can lead to nitrate leaching and environmental degradation [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Nitrate leaching is particularly pronounced in sandy soils, such as those found on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, where high permeability can increase nutrient loss [18]. Recommendations for N rates and application timings are primarily specific to highly productive potato regions, rather than smaller markets such as Virginia and North Carolina. Nitrogen rate recommendations for Virginia potatoes typically range between 140 and 168 kg N·ha−1, with an expected yield of ~22,000 kg·ha−1. Noted exceptions include some farms that achieve yields of up to 34,000 kg·ha−1 by applying high N rates [19]. These recommendations are below the suggested N rates for other potato-producing regions in the USA [20,21,22,23]. Moreover, current guidelines for selecting N rates in Virginia do not account for changes in plant metabolism, weather patterns, or GDD accumulation resulting from selected planting dates (Table 1).

Table 1.

Nitrogen management recommendations and expected yields in potato production across various USA regions (2009–2023).

Additionally, the timing of N applications is crucial for improving nutrient use efficiency. For example, splitting N applications across early- and mid-growth stages enhances nutrient uptake and reduces the risk of losses [19,21,22,25,26]. However, planting date variability complicates this process by altering the physiological timing of nutrient demand, making it difficult to standardize application schedules. These limitations underscore the need for site-specific N management strategies that align with the crop’s developmental stages.

Traditional nutrient monitoring methods, such as soil and tissue analysis, are essential for crop assessment, but are often labor-intensive, time-consuming, and unsuitable for large-scale applications [27,28,29]. Remote sensing (RS) technologies, particularly unmanned aerial systems (UAS), have emerged as powerful, real-time, non-invasive, and high-resolution tools for monitoring nutrient and soil [30]. Vegetation indices, such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and the Normalized Difference Red Edge Index (NDRE), are widely recognized for their ability to estimate plant nitrogen (N) status, biomass, and yield potential. NDRE is highly sensitive to changes in canopy chlorophyll content, making it an effective indicator of nitrogen sufficiency in crops [31]. Despite their growing adoption, the application of vegetation indices in potato production remains limited, particularly in integrating planting date and N management practices. Establishing the predictive capacity of these indices under diverse agronomic conditions is critical for advancing precision agriculture.

Soil-borne pests also pose a significant threat to potato production, further complicating the optimization of planting and nutrient strategies. Wireworms (Coleoptera: Elateridae) are among the most damaging pests in potato systems, causing direct tuber damage and reducing marketable yield [32]. Their activity is influenced by soil moisture, temperature, and organic matter content, with higher populations typically observed in fields with prolonged soil wetness or minimal tillage [33,34]. Similarly, plant-parasitic nematodes (PPNs) can significantly affect root systems, reducing water and nutrient uptake and predisposing plants to secondary infections [35]. Research has suggested that soil physicochemical properties, including pH, organic carbon, and nutrient availability, can influence pest populations and the severity of damage [36,37]. However, few studies have systematically evaluated these relationships in potato production systems that integrate planting date and N management. Understanding how these factors interact is crucial for developing effective and sustainable pest management strategies. Despite substantial advances in individual components of potato production, such as planting date optimization, nitrogen management, and RS application, the lack of an integrated framework limits the potential for systemic improvements. A comprehensive approach that combines these elements is essential for addressing the challenges of modern potato production. Hence, this study evaluated the effects of planting dates, N rates, and pest dynamics on white potatoes in the Eastern Shore of Virginia, USA. Additionally, by leveraging advances in UAS technology, agronomic experimentation, and soil-pest interactions, this study aims to fill critical knowledge gaps regarding the integration of RS into monitoring plant, soil, and pest status and to provide actionable insights for sustainable and efficient potato cropping systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Experimental Design

A study was conducted at Virginia Tech’s Eastern Shore Agricultural Research and Extension Center (ESAREC, Painter, Virginia) between 9 March and 28 July 2023. The study site was classified as a Bojac sandy loam soil, characterized by a pH of 5.5, an organic matter content of 1.1%, and a nitrate concentration of 17 ppm. The experiment was set up in a split-plot design with planting dates as the main plot and N regimen as the sub-plot factor, with four replications. Experimental plots consisted of 80 plants arranged in two rows, each 9.14 m long.

Potatoes were planted on 9 March, 21 March, and 4 April (early-, late-March, and early-April). Each planting date was fertilized with N rates of 0, 146, 180, 213, or 247 kg ha−1. Two N application proportions (early- and late-regimens) for each rate were also evaluated. In the early regimen, N rates were distributed at 50%, 30%, and 20% at 0, 30, and 60 days after planting (DAP), respectively. In the late-timing regimen, application rates were 30%, 50%, and 20% of the total N rate. Both regimens were used only for N rates > 180 kg ha−1 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Nitrogen fertilization treatment description for white potato production from March to August 2023 (Painter, Virginia). All treatments received a total of 56 kg ha−1 of P2O5 and 112 kg ha−1 of K2O during the season.

2.2. Cultivation Practices

The selected potato cultivar for the study was ‘Envol’, a white, early-season, fresh market potato. Seeds were manually cut to about 100 mm in diameter and treated with ethylene-bis-dithiocarbamate (Mancozeb, Potato Seed Treater PS, Loveland, CO, USA) at a rate of 1:100 kg−1∙kg−1 before planting. Seed pieces were mechanically planted in double rows, with 22.85 cm between plants and 91 cm between rows. At planting, seeds were also treated with mefenoxam (Ridomil Gold SL, Syngenta, Greensboro, NC, USA) at a rate of 420 g∙ha−1, azoxystrobin (Quadris, Syngenta, Greensboro, NC, USA) at 420 g∙ha−1, and acetamiprid (Assail, UPL, Cary, NC, USA) at 840 g∙ha−1, except of the first planting date (early-March), that was not applied with acetamiprid due to a planter malfunction.

Throughout their growth cycle, potato plants were hilled, vine-killed, and harvested at 30, 100, and 110 DAP, respectively. Vine-killing was accomplished using diquat dibromide (Diquat, Alligare, Opelika, AL, USA) at a rate of 2.8 L∙ha−1. Fertilization was performed using a mechanized base application of liquid Urea containing 30% N, supplemented by manual granular Urea (46-0-0) applications. In addition, to fulfill phosphorus (P2O5) and potassium (K2O) requirements, triple superphosphate (0-46-0) and potash (0-0-60) were applied at rates of 56 and 112 kg∙ha−1, respectively. The complete rate of P2O5 and K2O fertilizer was fully applied at planting.

2.3. Environmental Conditions, Soil, and Plant Measurements

Meteorological data were continuously recorded throughout the growing season to assess the environmental conditions that influenced potato growth at each planting date. The GDDs were calculated to quantify heat accumulation, a critical factor for crop development and phenological modeling. GDD was determined using the following formula:

where Tmax,30 represents the daily maximum air temperature, capped at 30 °C, and Tmin denotes the daily minimum air temperature. Tbase is the base temperature equal to 8 °C [38]. Air temperature, precipitation, and evapotranspiration (ET) were measured using a DAVIS Vantage Pro 2 weather station approximately 400 m from the study site. ET data was used to estimate crop water requirements and guide irrigation scheduling. Irrigation was applied to fully compensate for accumulated daily ET (100%), ensuring adequate soil moisture levels throughout the experiment. A boom irrigation system achieved uniform water distribution across all experimental plots. Soil nutrient availability, plant development, and biomass accumulation were comprehensively assessed as follows: Soil nitrate analysis was performed by collecting soil samples before planting, at 4 weeks after planting (WAP), and before the second N application, for each planting date. Sampling was conducted using a soil probe inserted at a depth of 30 cm at the center of each planted row. This process was repeated two to three times per experimental plot, in three replications, and the resulting subsamples were combined into a composite sample per plot. The composite samples were sent to a third-party soil laboratory (AgroLab Inc., Delaware, USA) for analysis of their nutrient content. Plant emergence and flowering were monitored throughout the experiment to track crop development. Plant emergence was recorded at 30 and 45 DAP for each planting date.

Additionally, the days to first flower and to reach 50% flowering were determined through regular plot inspections conducted every 2 to 3 days after reaching 40 DAP. Data collection included all plants within each experimental plot to ensure an accurate representation of growth patterns across treatments. Plant biomass and tissue samples were collected biweekly from 6 to 12 WAP, with two plants randomly selected per plot, stored in paper bags, and dried in a hot-air dryer at 65 °C for 3 weeks. After drying, the foliar and root biomass components were weighed and recorded separately. Plant tissue samples for N analysis were collected at 6, 8, and 12 WAP. Three to five randomly selected adult leaves per plot were carefully sampled and dried under the same conditions described above.

2.4. Remote Sensing (RS)

Aerial imaging was collected biweekly from 4 to 14 WAP using a DJI Mavic 3M Enterprise (DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) drone equipped with RGB and multispectral sensors. Four narrow bands centered at 560 ± 16 nm (green), 650 ± 16 nm (red), 730 ± 16 nm (red edge), and 860 ± 26 nm (near-infrared) were collected, along with RGB images, using the multispectral system. Flights were conducted at 46 m above ground, and the orthorectified imagery had, on average, a ground sampling distance (GSD) of ~2.3 cm per pixel, enabling fine-scale crop monitoring. Image processing was performed according to a standardized routine to ensure radiometric and geometric accuracy. Two-dimensional reconstruction, georeferencing, and orthorectification were performed using Pix4D Fields software (version 2.9.2), and radiometric calibration was performed using the drone’s included irradiance sensor to compensate for temporal changes in irradiance. These reflectance and RGB maps were then co-registered in QGIS to maintain the spatial consistency between the datasets. Agronomic descriptors were obtained from additional analyses performed in Python, which included min–max normalization of RGB bands and soil removal using binary vegetation masks. The canopy chlorophyll- and nitrogen-status-sensitive vegetation indices, including CIG, CVI, GNDVI, NDRE, and NDVI, were calculated and used to assess vegetation performance and predict nitrogen uptake, biomass accumulation, and yield potential (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multispectral vegetation indices, formula, and abbreviations used for UAS-based potato monitoring for planting date by nitrogen regimen interactions in potato production in 2023 (Painter, Virginia).

The average plant area per plant was estimated using a two-stage process. First, the total plant-covered area (Areatotal) for each plot was calculated from the UAS-derived RGB imagery. Vegetation pixels were segmented from the soil using binary vegetation masks. The resulting count of “green” pixels was then converted from pixels to a real-world area (in m2) by multiplying it by the squared GSD. The GSD for these flights was approximately 0.023 m pixel−1.

Second, this total area was normalized by the number of plants present in the plot at the time of image capture to determine the average area per plant (Areaplant).

The ‘Plant Count’ was not a static number. It was based on an initial planting density of 80 plants per plot and dynamically adjusted throughout the season to account for plants removed during the biweekly destructive biomass sampling events. This ensured the ‘Area per Plant’ calculation remained an accurate representation of the remaining plants. The integration of UAS-based imaging with multispectral analysis provided valuable insights into crop development, enabling the early detection of physiological changes and stress conditions associated with nitrogen availability and effects of planting date.

2.5. On-Farm Soil Pest Field Estimations

A field assessment was conducted across the Research Station (ESAREC) and six commercial farms in Accomack, Northampton, and Richmond counties. Three of these farms were sampled once during the 2022 growing season. The ESAREC and three different commercial farms were sampled during the 2023 growing season. At each farm, three randomly selected sampling points were designated, from which 3 m of killed vines (~10 plants) were manually harvested to assess tuber damage caused by wireworms. The harvested tubers were counted, weighed, and individually inspected for wireworm injury (presence or absence of wireworm injury per tuber was recorded), ensuring site consistency. Simultaneously, soil samples were collected at each sampling point for physicochemical analysis and PPN detection (Table 4). Each composite soil sample consisted of two to three subsamples, extracted using a soil probe inserted to a depth of 30 cm at the center of the planted rows.

Table 4.

Summary of analyzed soil physicochemical properties, including nutrient concentrations, pH, CEC, organic matter, and texture (Mehlich 3 Extraction Method) across seven potato farms in Eastern Virginia, USA.

To preserve sample integrity, soil samples designated for nematode analysis were carefully stored at or below 7 °C and analyzed within 5 days of collection by the Virginia Tech Tidewater AREC Nematode Diagnostic Lab. A total of 11 nematode species were identified and quantified per 500 cc of soil (Table 5). Results were reported as the total nematode count per 500 cc of soil per species.

Table 5.

Identified PPN species from soil samples collected in 2022 and 2023, including the median of regional soybean nematode economic thresholds used as reference for seven farms in Eastern Virginia, USA.

2.6. Yield Assessment

Tuber yield was assessed by classifying tubers into predefined size categories according to USDA standards and measuring the total number and weight of tubers in each category per experimental plot. Tubers were mechanically sorted into four size groups based on diameter: A3 (>8 cm), A2 (7–8 cm), A1 (5.5–6.99 cm), and B (4.5–5.49 cm). Once categorized, tubers were manually counted and weighed using a precision scale (0.02 kg accuracy). Following the yield measurements, tuber wireworm injury percentage (based on the presence and absence of wireworm injury per tuber) was evaluated by estimating the rate of affected tubers using subsamples per plot. This assessment was conducted through visual inspection, examining 10 to 20 randomly selected tubers per experimental plot and counting the total number with wireworm damage. This process was repeated across three replications for each nitrogen rate and planting date treatment to ensure statistical robustness and minimize sampling bias.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The collected data, including soil nitrate levels at 30 DAP, tuber yield, and UAS-derived plant area, were analyzed using R (version 4.4.0) and Python (version 3.12.2) within the Visual Studio Code (version 1.89) software environment. For soil nitrate levels at 30 DAP and tuber yield, a split-plot ANOVA was applied to account for the experimental design, with whole-plot (planting date) and subplot (N rate) factors tested against their appropriate error terms. Whenever significant effects were detected, post hoc analyses were conducted using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test at a 5% significance level (p < 0.05) to differentiate means. To identify predictors of key agronomic responses, Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to examine relationships among dry biomass, nitrogen percentage in plant tissue, total yield, and wireworm injury percentage. Based on these correlations, regression models were developed for the variables with the strongest associations.

Additionally, GDD accumulation was used as a predictor in regression analyses involving vegetation indices and plant area measurements to evaluate the impact of thermal time on crop development. Classification models were developed to assess whether soil physicochemical properties could predict wireworm injury and PPN presence. Wireworm injury percentage was categorized as low or high, with a threshold of 15% of the total number of injured tubers, determined from the distribution of injury percentages in the collected samples. PPN presence was classified as high if the total count exceeded 100 PPN per 500 cc of soil, which corresponds to the median of regional soybean nematode thresholds. Since potato-specific thresholds are not defined in the USA, these values provide a reference for presence classification. Two classification models were constructed for wireworm injury and PPN presence. The datasets were divided into training (70%) and test (30%) subsets for model development and validation. Model performance was evaluated using precision, recall, F1 score, accuracy, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Additionally, the predictor variables’ importance rankings were reported in descending order of significance.

3. Results

3.1. Weather and Plant Physiological Events

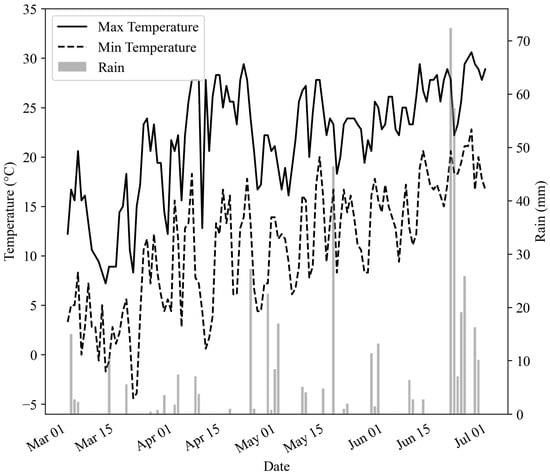

During the 2023 season, several heavy precipitation events (exceeding 25 mm day−1) were observed throughout the growing season, particularly towards the end. This uneven rainfall distribution resulted in the early-April planting date receiving significantly more precipitation than the other planting dates. Additionally, temperatures rose steadily from late March to early July (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Daily maximum and minimum temperatures and total daily precipitation recorded from late February to early July 2023 in Painter, Virginia. Temperature data are represented by solid (maximum) and dashed (minimum) lines, while precipitation is shown as gray bars.

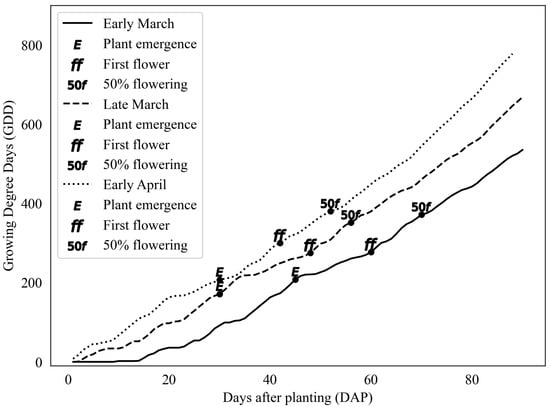

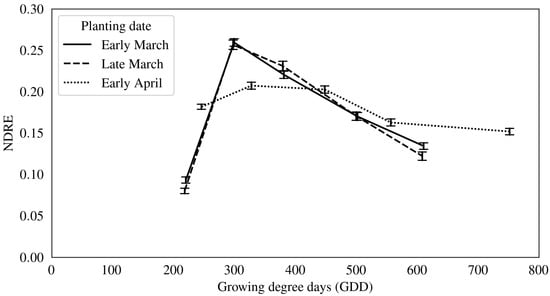

This trend was reflected in the accumulation of GDD for each planting date, with early-April planting accumulating more GDD than the other planting date treatments. The average daily rate of GDD accumulation for early-March, late-March, and early-April planting dates was 7.29, 8.13, and 8.83 GDD day−1, respectively. A distinctive observation is the occurrence of physiological events at specific GDD ranges. For instance, plant emergence occurred between 180 and 210 GDD, the first flowering between 250 and 300 GDD, and 50% flowering was observed between 350 and 400 GDD (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Accumulation of growing degree days (GDD) and key potato physiological events (plant emergence, first flower, and 50% flowering) for each planting date (Early-March, Late-March, and Early-April) during the 2023 season at Painter, Virginia.

3.2. Soil Nitrate Levels

At 30 DAP, nitrogen rate significantly affected soil nitrate concentration (F(1, 39) = 34.6, p < 0.001). However, there was no significant effect for planting date (F(2, 39) = 3.1, p = 0.057) or the planting date by nitrogen rate interaction (F(2, 39) = 0.2, p = 0.862) (See Table S1 for full ANOVA results). N rates of 247 and 213 kg∙ha−1 resulted in a higher soil nitrate concentration at 4 WAP at 30 cm depth. There was no difference between the 146 and 180 kg ha−1 rates in soil nitrate concentration, with an average of 42.8 ppm. The control treatment with no N application resulted in the lowest soil nitrate concentration (Table 6).

Table 6.

Influence of nitrogen rate on soil nitrate levels at 30 cm depth at 4 weeks after planting in the 2023 growing season at Painter, Virginia.

3.3. Plant Emergence

Planting dates produced a significant difference in plant emergence at 30 DAP (F(2, 90) = 3167.7, p < 0.001), while emergence was not significantly influenced by the N rate (F(1, 90) = 0.8, p = 0.362) or the interaction between N rate and planting date (F(2, 90) = 0.9, p = 0.392). Similarly, emergence at 45 DAP was not affected by any of the individual factors or their interactions (See Table S2 for full ANOVA results). Late-March planting resulted in 13% higher plant emergence than early-April planting. Additionally, early April resulted in 63% higher plant emergence than early March at 30 DAP (Table 7).

Table 7.

Effect of planting dates on potato emergence 30 and 45 days after planting during the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

An average of all N-treated plots in the late-March planting group was also compared to the control (no N applied) and a reference control with an equal distribution of N. Data showed no significant difference among treatments, with an average of 72.1 plants emerging at 30 days and 72.7 at 45 days (see Table S3 for the complete comparison). The exact emergence percentage could not be determined, as the number of seeds planted per plot was not precisely counted. Although the planting setup estimated 80 plants per plot, variations in seed size likely led to irregular planting densities, resulting in variable numbers of plants per plot.

3.4. Wireworm Damage Evaluation and Prediction

The ANOVA test for wireworm damage percentage in tubers showed significant differences for both the N rate (F(1, 66) = 4.4, p = 0.041) and planting date (F(2, 66) = 53.3, p < 0.001) factors (See Table S4 for full ANOVA results). Only the maximum N rate (247 kg N ha−1) showed significantly higher wireworm damage than treatments without N applications. Treatments without N application showed no significant difference compared to other evaluated N rates. Early March planting had significantly higher wireworm damage than the different planting dates, likely due to the accidental omission of wireworm insecticide during planting. On the early March planting date, the planter malfunctioned, and the insecticide was not appropriately applied. Conversely, subsequent planting dates exhibited no significant difference in wireworm damage (Table 8).

Table 8.

Effect of Nitrogen and planting date on potato tuber wireworm (WW) damage during the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

Injury estimates across tubers sourced from our study and six commercial farms were combined to assess potential correlations with soil properties. Pearson’s coefficients indicated that soil physicochemical properties showed positive (>0.4) and negative (<−0.4) correlations with wireworm damage in tubers. Soil nitrate concentration and hydrogen (H) saturation percentage were positively correlated with wireworm damage. Conversely, sodium (Na) saturation percentage, calcium (Ca) saturation percentage, and soil pH showcased negative correlations (Table 9).

Table 9.

Pearson’s correlation index values for variables highly correlated (>0.4 or <−0.4) with potato tuber wireworm injury percentage and injury level for the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

Predicting wireworm injury levels using decision tree and random forest classification algorithms yielded AUC scores of 0.80 and 0.88 on the training dataset, and 0.54 and 0.75 on the test dataset, respectively. This indicates a superior fit for the random forest model. However, the intricate relationships among soil properties are more easily explained using a decision tree model (as depicted in Figure S1). Nevertheless, both models prioritized Ca and H saturation percentages in their computations, although in varying orders of importance. In the random forest model, soil nitrate was found to have the highest importance, accounting for 30% of the model (Table 10) (See Table S5 for full feature importance of both classification models).

Table 10.

Performance on training and test data of wireworm injury level classification models for the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

3.5. Plant Area Estimations

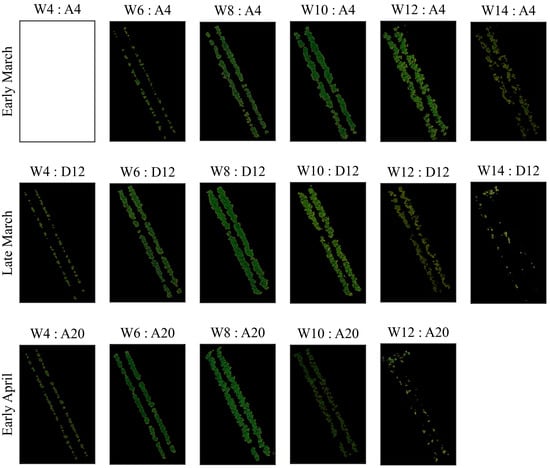

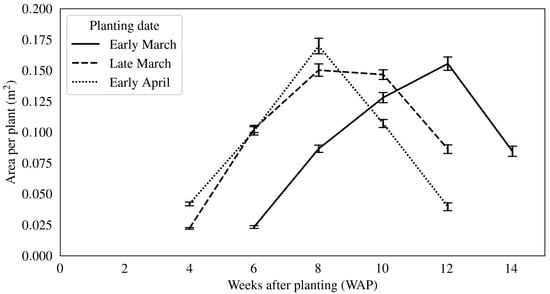

The analysis of aerial imaging provided significant insights into variations in plant growth across different planting dates. Visual assessments revealed apparent differences in the green-covered area across planting dates, indicating differences in plant growth. The timing of plant emergence and the onset of senescence-induced foliar biomass reduction varied with planting date and the number of WAP (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Biweekly aerial images of specific potato plots per planting date with soil values removed in 2023 at Painter, Virginia.

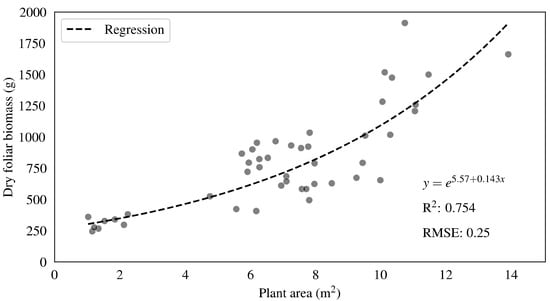

Although biomass measurements were collected biweekly throughout this period, a malfunction in the drying equipment caused damage and the loss of most samples. The remaining samples were insufficient for robust statistical comparisons but were still used to explore potential predictors of plant biomass from 4 to 14 WAP. Pearson’s correlation analysis indicated that plant area estimates from aerial imagery were strongly correlated with above-ground biomass (Table 11). This relationship was further evaluated through regression analysis (R2 = 0.75) (Figure 4), demonstrating the potential of aerial imaging for biomass estimation.

Table 11.

Pearson correlation values of variables highly correlated (>0.6) with potato foliar, root, and total dry biomass measurements collected in 2023 at Painter, Virginia.

Figure 4.

Regression for potato dry foliar biomass collected from 4 to 14 WAP as a function of plant area measured using aerial images collected in 2023 at Painter, Virginia.

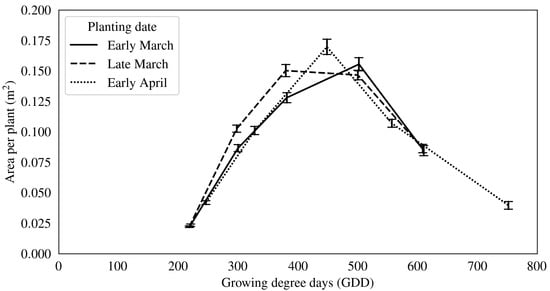

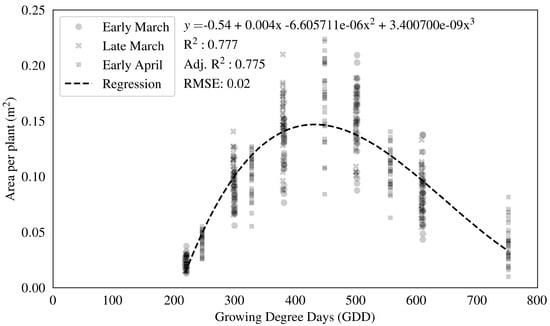

Plant area growth curves per planting date were separated when evaluated based on weeks after planting (WAP) (Figure 5). The early-April planting exhibited a steeper, higher growth curve than earlier planting dates, indicating a higher growth rate. On average, early-April planting resulted in a 14% higher growth rate than late-March planting and a 64% higher growth rate than early-March planting. Furthermore, when plant area accumulation was evaluated against GDD accumulation, the curves converged across planting dates (Figure 6). A third-degree polynomial regression described the relationship between plant area growth and GDD accumulation (Figure 7). The peak of this function, at 432 GDD, marks the transition point at which above-ground biomass begins to decline, signaling the onset of plant senescence.

Figure 5.

Biweekly potato plant area growth curves per planting date from 4 to 14 weeks after planting for the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

Figure 6.

Potato plant area growth curves per planting date by accumulating growing degree days for the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

Figure 7.

Regression for potato plant area measured with aerial images as a function of growing degree days for the 2023 season at Painter, Virginia.

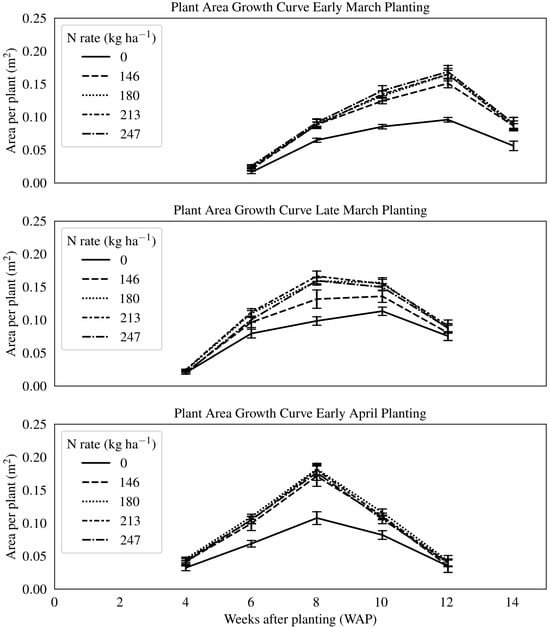

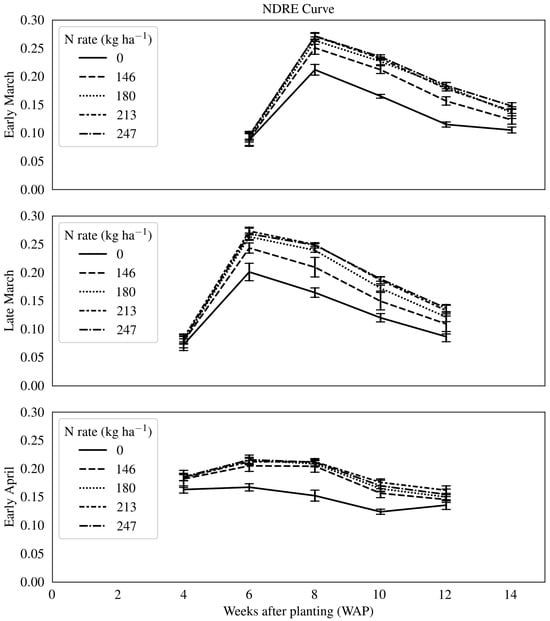

Regarding N applications, the absence of N led to a significant reduction in plant area across all planting dates (Figure 8). The timing of the N application also affected the plant area distinctly for the early-April planting date at both 6 and 8 WAP. Early N applications resulted in a higher plant area than late applications for potatoes planted in early April.

Figure 8.

Potato plant area growth curves per N rate and planting date in 2023 at Painter, Virginia.

3.6. Vegetation Indices

Correlation analysis using Pearson’s coefficient identified the NDRE as the most significant predictor of nitrate content in plant tissue (r = 0.9). Notably, all other indices also exhibited high correlations (NDVI = 0.86, GNDVI = 0.86, CIg = 0.89, CVI = 0.72). Subsequent regression analysis revealed a linear relationship between NDRE and nitrate percentage in plant tissue (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Regression for nitrogen percentage in potato plant tissue as a function of Normalized Difference Red Edge (NDRE) value for the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

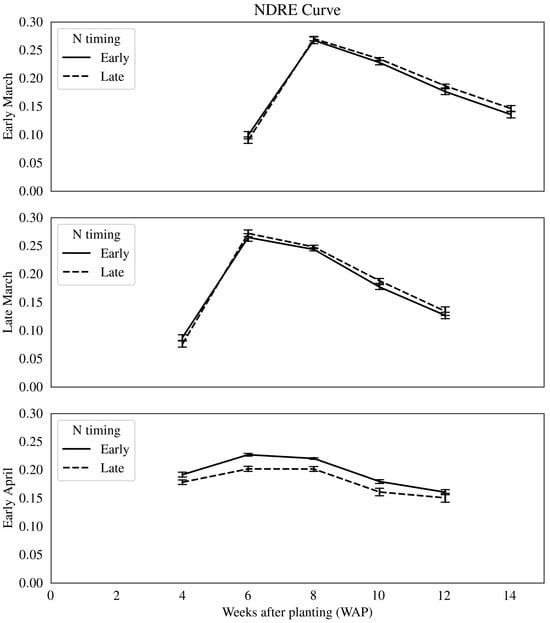

NDRE values for early planting dates were significantly lower at the start of the season, indicating reduced nitrate uptake and assimilation in plant tissue (Figure 10). Treatments with no N-fertilization exhibited significantly lower NDRE values across planting dates than N-applied treatments, showing an average reduction of 24% (Figure 11). In addition, NDRE values were considerably higher for early-applied N treatments in the April planting than late-applied N treatments, resulting in an average increase of 10% (Figure 12).

Figure 10.

Normalized Difference Red Edge (NDRE) by accumulated growing degree days (GDD) per planting date for the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

Figure 11.

Effect of planting date and nitrogen rate on potato Normalized Difference Red Edge (NDRE) curve for the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

Figure 12.

Effect of planting date and nitrogen application timing on potato Normalized Difference Red Edge (NDRE) curve for the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

3.7. Tuber Yield and Quality

There were significant differences in tuber yield based on N rate (F(1, 78) = 43.9, p < 0.001) and planting date (F(2, 78) = 4.8, p = 0.011) factors (see Table S6 for full ANOVA). The absence of N-fertilization resulted in the lowest yield. However, when N was applied, the differences in yield across N rates were not statistically significant. Similarly, the timing of N application did not significantly affect tuber yield. The detailed effects of N rate and planting date on yield and tuber characteristics are presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

Influence of planting date, nitrogen rate, and application timing on potato tuber yield and wireworm damage during the 2023 growing season in Painter, Virginia.

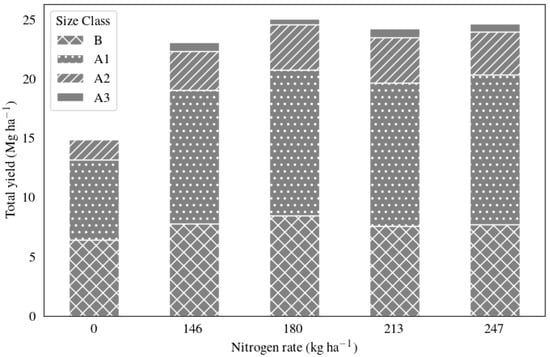

The absence of N-fertilization resulted in the lowest yield (14.98 Mg ha−1). While all N-fertilized treatments performed significantly better, there were no statistically significant differences in total yield among the 146, 180, 213, and 247 kg ha−1 rates. This pattern also held for the total number of tubers and average tuber weight. For planting date, late-March produced the highest total yield (24.96 Mg ha−1), while early-April produced tubers with the highest average weight (106.45 g), a 19% increase over the other planting dates. Additionally, the N rate affected the distribution of tuber size classes. The higher average weight in N-fertilized plots is supported by a larger proportion of A-sized tubers (A1, A2, and A3) than in the control (0 N rate), which was dominated by smaller B-sized tubers (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Effect of N rate on total potato tuber yield per size class for the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

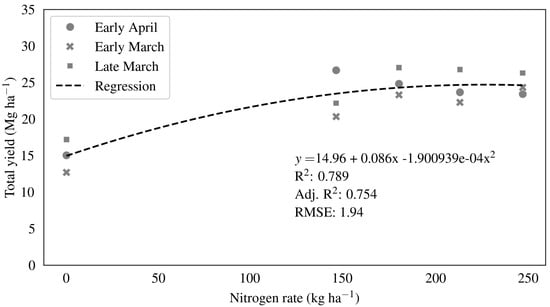

To model the optimal nitrogen level, a regression analysis was performed on total yield as a function of N rate. The regression model suggested that 227 kg N ha−1 optimizes tuber yield across all planting dates. However, given the lack of statistical difference above 146 kg ha−1, the analysis suggests that planting in late March with a N application rate of 180 kg ha−1 represents the optimal combination, as it maximizes yield with the minimum required inputs (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Regression for total tuber yield as a function of nitrogen rate for the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

The tuber yield results for treatments with N application fell within the expected yield range for this region (22.4-26.9 Mg ha−1), reinforcing the validity of previous regional N rate recommendations [19]. The resulting tuber wireworm damage levels per planting date were consistent with prior research evaluating the efficacy of several insecticide wireworm controls in the Eastern Shore of Virginia [44]. However, while previous findings suggest that larger tubers are more susceptible to wireworm damage, our early-April planting, which produced the largest tubers, did not exhibit higher damage levels. A plausible explanation could be rooted in the interplay of evaluating wireworm damage, tuber size class, and planting dates, which was not assessed in this study. Additionally, NDRE values indicated that applying N early in the season may enhance N content in plant tissue, particularly in the early-April planting date. Moreover, this optimized planting and fertilization strategy resulted in the highest estimated gross profit per hectare compared to conventional practices (Table 13).

Table 13.

Evaluation of proposed traditional planting dates, nitrogen rate, and application timing combination on tuber total weight and estimated gross profit between March and July 2023 at Painter, Virginia.

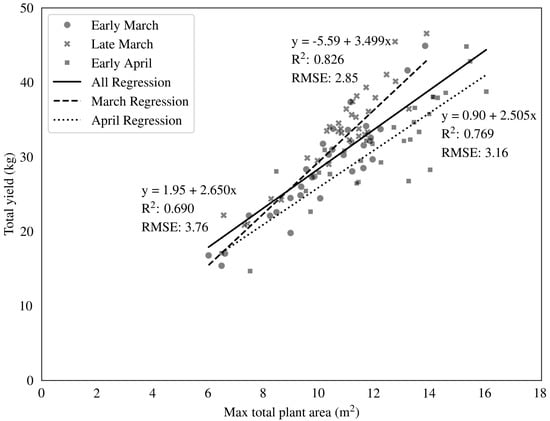

Furthermore, a correlation analysis segmented by planting date using Pearson’s coefficient identified the total plant area as the strongest predictor of tuber yield (r > 0.87) (Figure S2). While the total plant area was consistently the primary correlator across all planting dates, the peak correlation was reached at different WAP. These peaks aligned with the WAP corresponding to the maximum observed plant area in the plant area curves. Based on this, subsequent regression analyses utilized maximum plant area as the primary predictor variable (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Regression for total potato tuber yield as a function of maximum plant area measured with aerial images collected in 2023 in Painter, Virginia.

Applications of the resulting yield-prediction models, which use plant-area measurements, can accurately predict tuber yield 4 to 6 weeks before harvest. However, given our methodology’s sensitivity to extraneous green vegetation, such as weeds, the actual plant area estimates could be skewed in more complex agricultural settings. Additionally, the relationships depicted may be specific to the Envol cultivar. Therefore, applying these models in real-world settings requires additional scrutiny and fine-tuning.

3.8. PPN Presence Level Prediction

Evaluating decision trees and random forest classification algorithms on PPN presence using soil physiochemical properties resulted in an AUC score of 0.88 and 0.73 on the training dataset and 0.58 for both algorithms on the test dataset. This indicates a superior fit for the decision tree model (further detailed in Figure S3). Although the decision tree model outperformed the random forest model on the training dataset, both models performed poorly (AUC < 0.7) on the test dataset, rendering them unsuitable for use on unseen data or in real-world scenarios. However, both models assigned the highest importance score to the K saturation percentage. The decision tree model assigned this factor a significance level of over 60%. Meanwhile, in the random forest model, K saturation percentage and soil pH accounted for 50% of the model’s significance (Table 14) (See Table S7 for the full feature importance of both classification models).

Table 14.

Performance on training and test data of PPN presence level classification models for the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia.

4. Discussion

The integration of planting date, nitrogen (N) management, and spectral indicators revealed strong interactions among environmental conditions, plant physiology, and yield formation in potato cropping systems of Eastern Virginia. The results highlight that the physiological timing of crop events, expressed through accumulated growing degree days (GDD), provides a more reliable framework for interpreting crop performance than calendar-based management. The consistent synchronization of emergence and flowering stages with specific GDD thresholds demonstrates that temperature-driven development strongly determines nutrient uptake efficiency and yield potential. Consequently, adopting GDD as a basis for scheduling N applications could improve the temporal alignment between nutrient supply and plant demand, thereby minimizing inefficiencies observed when N is applied at fixed days after planting (DAP).

Late-March planting showed superior yield and emergence performance compared with early-March, suggesting that moderate soil and air temperatures during this period favored rapid emergence and canopy closure while avoiding the low-temperature stress that limited early planting. Early-April planting, despite accumulating more GDD, resulted in fewer but larger tubers, reflecting a shift in assimilate partitioning from the number of sink organs to their size. These results demonstrate a trade-off between total yield and marketable tuber size, reinforcing that intermediate thermal and photoperiodic conditions optimize source–sink relationships.

Nitrogen rate and application timing influenced soil nitrate dynamics and canopy development, although timing effects on yield were not statistically significant. The absence of yield differences among N-applied treatments above 146 kg ha−1 suggests that the Envol cultivar reached saturation for N uptake, beyond which additional fertilization did not translate into higher productivity. Early applied N promoted higher NDRE and NDVI values, indicating enhanced chlorophyll content and nitrogen assimilation during the vegetative phase. The strong correlations observed between NDRE and foliar N content (R2 = 0.90) and between plant area and yield (R2 = 0.75) confirm that spectral and structural traits can serve as early indicators of crop performance. These findings validate the potential of UAS-based monitoring for assessing plant nutrition and predicting yield several weeks before harvest.

The relationship between NDRE dynamics and GDD accumulation provides mechanistic insights into canopy function. NDRE values increased sharply during the initial 250–400 GDD, coinciding with the rapid expansion of the photosynthetically active area, and stabilized after canopy closure. The subsequent decline beyond 430 GDD aligned with the onset of senescence. This pattern defines a clear thermal window for effective N uptake, supporting the use of NDRE and GDD as complementary tools for precision fertilization.

Soil properties exerted a significant influence on pest dynamics. Wireworm injury was highest in early-March plantings, primarily due to the lack of insecticide application, but also exacerbated by cooler, wetter soil conditions that favor larval survival. The positive correlation of wireworm injury with soil nitrate and hydrogen saturation, and its negative association with calcium and pH, suggest that chemical and structural soil factors contribute to pest incidence. The classification models further emphasized nitrate and calcium saturation as key predictors of injury risk, suggesting that soil fertility and cation balance may indirectly affect pest behavior or tuber susceptibility. PPN models also identified potassium saturation and pH as dominant predictors, though with limited robustness.

The convergence of plant area and NDRE as predictors of yield demonstrates that canopy structure and pigment status encapsulate most of the variability driven by planting date and N management. Plant area, particularly the maximum recorded before senescence, integrated the cumulative effects of emergence rate, vegetative growth, and photosynthetic efficiency, which collectively determine yield potential. The polynomial relationships between plant area or NDRE and GDD accumulation underscore the dynamic coupling between environmental forcing and canopy development.

Altogether, the results demonstrate that synchronizing N management with GDD-based phenological stages improves nutrient-use efficiency and yield stability. The integration of UAS-derived metrics, such as NDRE and plant area, offers a practical framework for real-time monitoring and early yield forecasting. Moreover, identifying soil chemical indicators associated with pest occurrence adds a complementary dimension for risk assessment within precision agriculture systems. This combined approach supports the transition toward sustainable, data-driven potato production in the Eastern USA by optimizing inputs, reducing losses, and improving grower profitability.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that aligning nitrogen (N) management with GDD-based phenological stages, rather than fixed days after planting (DAP), could significantly improve nutrient management in potato production. Our findings show that GDD is a reliable predictor for key growth stages, such as emergence and flowering, regardless of planting date. The essential, actionable finding for the ‘Envol’ cultivar in this region was that a late-March planting combined with an N rate of 180 kg ha−1 provided the highest tuber yield and gross profit. Furthermore, this research confirmed the high potential of UAS-based remote sensing for in-season monitoring. The Normalized Difference Red Edge Index (NDRE) was a strong predictor of N content in plant tissue (R2 = 0.81), and the maximum plant area accurately predicted final tuber yield 4–6 weeks before harvest. Finally, soil physicochemical properties, particularly calcium and hydrogen saturation, were identified as potential predictors for wireworm damage risk.

The limitations of this study must be acknowledged. These findings are based on a single growing season (2023) and one potato cultivar (‘Envol’). Environmental conditions vary significantly year to year, which can affect GDD accumulation, pest dynamics, and nutrient availability. Therefore, the specific yield models and optimal N strategies presented may not be directly applicable to other cultivars or seasons. Future research should focus on validating these models by testing them across multiple growing seasons and under different environmental conditions. Expanding this work to include other commercially important potato cultivars is also necessary. This will help develop more robust, GDD-based nutrient management and yield-prediction models that provide resilient, data-driven recommendations for potato producers on the Eastern Shore of Virginia.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121451/s1, Table S1. Analysis of variance for soil nitrate levels during the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia. Table S2. Analysis of variance for plant emergence during the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia. Table S3. Effect of Nitrogen application on late-March planting date potato emergence at 30 and 45 days after planting during the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia. Table S4. Analysis of variance for potato tuber wireworm damage during the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia. Table S5. Feature importance of the decision tree and random forest classification models for potato tuber wireworm injury level for 2022 and 2023 data collected in North Hampton and Accomack counties, Virginia. Table S6. Analysis of variance for potato tuber yield during the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia. Table S7. Feature importance of the decision tree classification model for nematode presence level for 2022 and 2023 data collected in North Hampton and Accomack counties, Virginia. Figure S1. Decision tree classification model for potato tuber wireworm injury level using soil chemical properties measured from samples collected in 2022 and 2023 in North Hampton and Accomack counties, Virginia. Gini: probability of misclassification at a node. Figure S2. Correlation matrix heatmap of highly correlated (r > 0.6) variables with total tuber yield per planting date for the 2023 season in Painter, Virginia. Figure S3. Decision tree classification model for PPN presence level using soil chemical properties measured from samples collected in 2022 and 2023 in North Hampton and Accomack counties, Virginia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.T.-Q. and F.F.-P.; methodology, A.S., E.T.-Q. and L.L.; software, A.S.; validation, A.S., A.B. and F.F.-P.; formal analysis, A.S. and M.R.; investigation, A.S., L.L. and E.T.-Q.; resources, M.R. and A.B.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. and E.T.-Q.; writing—review and editing, F.F.-P., L.L. and A.B.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, E.T.-Q. and F.F.-P.; project administration, E.T.-Q.; funding acquisition, E.T.-Q. and F.F.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Virginia Specialty Crop Block Grant Program, U.S. Department of Agriculture, project award no. 2021B-568. Funding for this work was provided in part by the Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station and the Hatch program of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, US Department of Agriculture.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this research thank the Stress Mitigation in Agricultural Research for Targeted-crops (S.M.A.R.T.) international initiative, the International Initiative for Digitalization in Agriculture (IIDA), and Corporación de Tecnologías Avanzadas para la Agricultura Macrozona Centro-Sur (CTAA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- USDA. Specialty Crops Market News (Custom Report); United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Marketing Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Haverkort, A.J.; MacKerron, D.K.L. (Eds.) Potato Ecology and Modelling of Crops Under Conditions Limiting Growth: Proceedings of the Second International Potato Modeling Conference, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 17–19 May 1994; Springer Science+Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 978-94-010-4028-0. [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Tech. WeatherSTEM Data Mining Tool; Virginia Tech: Blacksburg, VG, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, G.R.; Stanley, C.D.; Grant, W.J.; Torrey, D.B. Potato top growth as influenced by temperatures. Am. Potato J. 1983, 60, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gonzalez, J.; Mehl, H.L.; Langston, D.B.; Rideout, S.L. Planting date and cultivar selection to manage southern blight in potatoes in the mid-Atlantic United States. Crop Prot. 2022, 162, 106077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Niu, S.; Zhang, G.; Chen, G.; Haroon, M.; Yang, Q.; Rajora, O.P.; Li, X.-Q. Physiological and growth responses of potato cultivars to heat stress. Botany 2018, 96, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M.S.H.; Hossain, S.M.M.; Islam, A.T.M.S.; Hannan, A.; Hossain, J.; Islam, M.R. Production of disease-free seed potato tuber through optimization of planting and haulm pulling time: Enhanced maximum photosynthesis and growth for higher seed potato yield. Bangladesh J. Agric. 2023, 48, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, S.; Jo, M.; An, S.; Kim, Y.; Yoon, J.; Jeong, M.-H.; Kim, E.Y.; Choi, J.; Kim, Y.; et al. Isolation and Identification of Alternaria alternata from Potato Plants Affected by Leaf Spot Disease in Korea: Selection of Effective Fungicides. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, A.H.; Forbes, G.A.; Hijmans, R.J.; Garrett, K.A. Climate change may have limited effect on global risk of potato late blight. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 3621–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, M.; Naumann, M.; Pawelzik, E.; Gransee, A.; Thiel, H. The importance of nutrient management for potato production Part I: Plant nutrition and yield. Potato Res. 2020, 63, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochmuth, G.; Mylavarapu, R.; Hanlon, E. The Four Rs of Fertilizer Management. Edis 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milroy, S.P.; Wang, P.; Sadras, V.O. Defining upper limits of nitrogen uptake and nitrogen use efficiency of potato in response to crop N supply. Field Crops Res. 2019, 239, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Meng, M.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, H.; Su, T. Quantitative Analysis of Source-Sink Relationships in Two Potato Varieties under Different Nitrogen Application Rates. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xiong, B.; Wang, S.; Deng, X.; Yin, L.; Li, H. Regulation Effects of Water and Nitrogen on the Source-Sink Relationship in Potato during the Tuber Bulking Stage. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, B.; Fan, J.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. A Systematic Study of Estimating Potato N Concentrations Using UAV-Based Hyper- and Multi-Spectral Imagery. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, R.; Paswan, S. Influence of higher levels of NPK fertilizers on growth, yield, and profitability of three potato varieties in Surma, Bajhang, Nepal. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann-Pfabe, S.; Dehmer, K.J. Evaluation of Wild Potato Germplasm for Tuber Starch Content and Nitrogen Utilization Efficiency. Plants 2020, 9, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, M.S.; Rideout, S.L.; Freeman, J.H. Nitrogen Fertilizer and Growth Regulator Impacts on Tuber Deformity, Rot, and Yield for Russet Potatoes. Int. J. Agron. 2012, 2012, 348754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reiter, M.S.; Phillips, S.B.; Warren, J.G.; Maguire, R. Nitrogen Management for White Potato Production; Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2009; Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/items/dd6a96e6-e70d-4777-895c-af1a3c712b0e/full (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Westermann, D.T. Nutritional requirements of potatoes. Am. J. Potato Res. 2005, 82, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehrson, L.; Mahler, R.L.; Bechinski, E.J.; Williams, C. Nutrient Management Practices Used in Potato Production in Idaho. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2011, 42, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.L.B.R.D.; Zotarelli, L.; Dukes, M.D.; Van Santen, E.; Asseng, S. Nitrogen fertilizer rate and timing of application for potato under different irrigation methods. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 283, 108312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, D.; Robinson, A.; Rosen, C. Fertilizing Potato in North Dakota; North Dakota State University: Fargo, ND, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Plant Nutrition for Food Security: A Guide for Integrated Nutrient Management; FAO Fertilizer and Plant Nutrition Bulletin 16; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zebarth, B.J.; Leclerc, Y.; Moreau, G. Rate and timing of nitrogen fertilization of Russet Burbank potato: Nitrogen use efficiency. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2004, 84, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, S.L.; Stark, J.C.; Salaiz, T. Response of four potato cultivars to rate and timing of nitrogen fertilizer. Am. J. Potato Res. 2005, 82, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Guérif, M.; Baret, F.; Skidmore, A.; Gitelson, A.; Schlerf, M.; Darvishzadeh, R.; Olioso, A. Simple and robust methods for remote sensing of canopy chlorophyll content: A comparative analysis of hyperspectral data for different types of vegetation. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 2609–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Huerta, R.; Guevara-Gonzalez, R.; Contreras-Medina, L.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Prado-Olivarez, J.; Ocampo-Velazquez, R. A Review of Methods for Sensing the Nitrogen Status in Plants: Advantages, Disadvantages and Recent Advances. Sensors 2013, 13, 10823–10843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Liu, N.; Wu, L.; Li, M.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, J. Estimation of Chlorophyll Content in Potato Leaves Based on Spectral Red Edge Position. IFAC-Pap. 2018, 51, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhaled, A.; Townsend, P.A.; Wang, Y. Remote Sensing for Monitoring Potato Nitrogen Status. Am. J. Potato Res. 2023, 100, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morier, T.; Cambouris, A.N.; Chokmani, K. In-Season Nitrogen Status Assessment and Yield Estimation Using Hyperspectral Vegetation Indices in a Potato Crop. Agron. J. 2015, 107, 1295–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herk, W.G.; Vernon, R.S.; Goudis, L.; Mitchell, T. Protection of Potatoes and Mortality of Wireworms (Agriotes obscurus) With Various Application Methods of Broflanilide, a Novel Meta-Diamide Insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol. 2022, 115, 1930–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, K.W.; Abney, M.R. Relative susceptibility of selected potato cultivars to feeding by two wireworm species at two soil moisture levels. Crop Prot. 2017, 101, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Racca, P.; Schmitt, J.; Kleinhenz, B. SIMAGRIO-W: Development of a prediction model for wireworms in relation to soil moisture, temperature and type. J. Appl. Entomol. 2014, 138, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, A.M.; Back, M.; Blok, V.C. Population dynamics of the potato cyst nematode, Globodera pallida, in relation to temperature, potato cultivar and nematicide application. Plant Pathol. 2019, 68, 962–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Lu, P.; Xu, T.; Pan, K. Three Preceding Crops Increased the Yield of and Inhibited Clubroot Disease in Continuously Monocropped Chinese Cabbage by Regulating the Soil Properties and Rhizosphere Microbial Community. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutassem, D.; Belabid, L.; Bellik, Y.; Rouag, N.; Abed, H.; Ziouche, S.; Baali, F. Role of soil physicochemical and microbiological properties in the occurrence and severity of chickpea’s Fusarium wilt disease. Eurasian J. Soil Sci. EJSS 2019, 8, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Reclamation AgriMet Growing Degree Days Algorithm. Available online: https://www.potatogrower.com/2023/06/calculating-growing-degree-days#:~:text=Daily%20GDD%20is%20calculated%20by,which%20potato%20growth%20is%20diminished (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Gitelson, A.A.; Gritz, Y.; Merzlyak, M.N. Relationships between leaf chlorophyll content and spectral reflectance and algorithms for non-destructive chlorophyll assessment in higher plant leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincini, M.; Frazzi, E.; D’Alessio, P. A broad-band leaf chlorophyll vegetation index at the canopy scale. Precis. Agric. 2008, 9, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.; Merzlyak, M.N. Quantitative estimation of chlorophyll-a using reflectance spectra: Experiments with autumn chestnut and maple leaves. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 1994, 22, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehl, H.L. Nematode Management in Field Crops; Virginia Tech: Blacksburg, VG, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhar, T.P.; Alvarez, J.M. Timing of injury and efficacy of soil-applied insecticides against wireworms on potato in Virginia. Crop Prot. 2008, 27, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).