Abstract

Fermented vegetables host complex microbiomes that drive flavor and functionality. We compared cowpea pod fermentations produced by a Korean kimchi-style method (HG) versus a Sichuan paocai-style method (SC) to isolate technique-driven effects on community structure and functional potential. Cowpea pods were fermented for 10 days in triplicate, profiled by 16S rRNA (V3-V4) amplicon sequencing, analyzed in QIIME2, and functionally inferred with PICRUSt2. SC exhibited higher alpha diversity (Shannon, Chao1, Simpson) than HG (p < 0.05), and beta-diversity (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) showed clear separation by fermentation style (PERMANOVA p = 0.001), indicating method-dependent community assembly. Both styles were dominated by lactic acid bacteria, chiefly Leuconostoc, Lactobacillus, and Weissella, but their proportions differed: HG retained higher Leuconostoc/Weissella, whereas SC favored Lactobacillus. Predicted functions diverged accordingly: HG was enriched for carbohydrate-metabolism genes (e.g., β-galactosidase; dextransucrase), consistent with rapid sugar fermentation and possible exopolysaccharide formation; SC showed enrichment of amino-acid-related pathways (e.g., acetolactate synthase; glutamate dehydrogenase), heterolactic fermentation, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) biosynthesis, suggesting broader metabolic outputs relevant to flavor development and potential health attributes. Overall, fermentation technique substantially shapes both the microbiome and its predicted repertoire, with HG prioritizing carbohydrate catabolism and SC showing expanded metabolic potential; these insights can inform starter selection and process control for targeted product qualities.

1. Introduction

Fermenting vegetables is an ancient culinary practice that enhances food preservation, flavor, and nutritional value through the activity of live microorganisms [1]. Kimchi and paocai are two iconic fermented vegetable products from Korea and China, respectively, each prepared via distinct techniques rooted in their regional food cultures [2,3]. Kimchi typically refers to a broad variety of Korean fermented vegetables (most famously Napa cabbage) made by salting the vegetables and fermenting them with a mixture of seasonings such as chili pepper, garlic, ginger, and often seafood-based condiments [4]. Fermentation in kimchi is primarily driven by lactic acid bacteria (LAB) that naturally reside on the ingredients, leading to an anaerobic lactic acid fermentation that rapidly acidifies the product [5]. In contrast, paocai (traditional Sichuan pickled vegetables) is usually prepared by submerging vegetables in a brine (salty water often seasoned with spices like Sichuan pepper, chili, garlic, etc.) [6], sometimes with the addition of a starter (such as a portion of aged brine or a small amount of vinegar or alcohol) to initiate the pickling process [7]. While both kimchi and paocai involve salt-tolerant microbiota and result in sour, preserved vegetables, the fundamental difference lies in their fermentation processes: kimchi’s acidity arises from microbial metabolism (fermentation), whereas paocai often involves elements of pickling, where acidity can come from an external source (vinegar or pre-acidified brine) and the microbial growth conditions differ.

These process differences are known to influence the resulting microbial community and biochemical composition of the final product [8]. Korean kimchi fermentations are typically dominated by LAB such as Leuconostoc, Lactobacillus, and Weissella, which sequentially flourish during fermentation. Early in kimchi fermentation, heterofermentative LAB (e.g., Leuconostoc spp.) produce CO2, ethanol, and mannitol, creating an anaerobic environment and contributing to kimchi’s mild sweetness and carbonation; as fermentation progresses and acidity increases, homofermentative Lactobacillus spp. come to dominate, producing lactic acid as the principal metabolite [9]. This dynamic succession results in a tangy, well-acidified product typically within 1–2 weeks, depending on temperature. Sichuan paocai fermentations, on the other hand, often proceed under higher salt concentrations and sometimes with inhibitory factors (e.g., alcohol in some traditional brines), potentially resulting in slower or different microbial succession. Some studies have reported that total microbial counts and LAB counts increase more rapidly and reach higher levels in kimchi than in paocai under similar conditions. For example, Nugroho et al. found that kimchi fermentation led to a sharp pH drop and ~26-fold increase in LAB within 5 days, whereas paocai prepared with a high-salt, alcohol-containing brine showed a more modest (~3-fold) LAB increase and higher residual pH [10]. In some cases, LAB are not immediately dominant in paocai fermentations; instead, other bacteria (such as Pseudomonas and Enterobacter species) may proliferate in early stages until LAB eventually take over as the environment acidifies [11]. These differences can influence not only safety (e.g., risk of nitrite accumulation or spoilage organisms in paocai if LAB growth is insufficient) but also the flavor profile and functional properties of the fermented vegetables.

Fermented foods like kimchi are increasingly recognized for their potential health benefits [12]. The live LAB in kimchi/paocai can act as probiotics, and the fermentation process can increase levels of bioactive compounds. For instance, kimchi and related ferments naturally contain γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), a non-protein amino acid produced by certain LAB via glutamate decarboxylase, which has known anti-stress and blood pressure-lowering effects [13]. LAB-driven fermentation can also produce or preserve other beneficial metabolites such as vitamins, peptides, and short-chain fatty acids. Butyrate, acetate, and propionate are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) often associated with gut health; while these are primarily produced by gut microbes, fermentation of plant substrates may encourage growth of SCFA-producing bacteria or yield precursors that promote butyrate production upon consumption [14]. The organoleptic properties of fermented vegetables-aroma, taste, and texture-are likewise products of microbial metabolism. Heterolactic LAB produce CO2 (imparting a slight effervescence or crunch), ethanol, and volatile compounds like acetoin and diacetyl that add complexity (a buttery or tangy note) [15]. Amino acid catabolism during fermentation can release compounds such as bioamines and sulfur volatiles. For example, degradation of methionine can generate methanethiol, a sulfur compound contributing to the distinctive pungency of fermented cabbage, while arginine metabolism by LAB (via the arginine deiminase pathway) yields ornithine and ammonia, potentially influencing flavor and pH [16]. These metabolic pathways can differ between fermentation styles due to the differing dominant microbes and conditions [17].

Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) pods are a nutrient-rich legume vegetable not traditionally used in Korean kimchi, yet potentially well-suited for fermentation. They contain dietary fibers and sugars that fermenting microbes could utilize, and fermentation might reduce anti-nutritional factors common in legumes (e.g., raffinose-family oligosaccharides) to improve digestibility [18]. While cowpea and other bean pods are sometimes fermented or pickled in various cuisines, there is limited scientific literature on their fermentation microbiota. Comparing a Korean-style vs. Sichuan-style fermentation using the same raw ingredient (cowpea pods) provides a unique opportunity to isolate the effect of fermentation technique on microbial community development and functional outputs [5]. Previous comparative studies of kimchi and paocai have largely focused on the end-product chemistry or health effects, but few have examined the underlying microbiomes and their functional genes in parallel [10].

In this study, we conducted a comparative microbiome analysis of cowpea pod fermentations prepared according to HG and SC methodologies. Using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, we profiled the microbial communities after 10 days of fermentation and assessed alpha and beta diversity differences between the two fermentation styles. We further utilized PICRUSt2 to predict metagenomic functional potential from the 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing data, focusing on KEGG Orthologs (KOs), Enzyme Commission (EC) categories, and MetaCyc metabolic pathways. We hypothesized that the different fermentation practices would lead to distinct microbial assemblages and functional profiles, which in turn could influence flavor metabolite production and potential health-promoting attributes of the fermented cowpea kimchi. The results of this work will advance our understanding of how traditional fermentation methods shape the microbiome of fermented foods and may guide the design of fermentations for improved flavor complexity and nutritional functionality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation and Fermentation Procedures

Fresh cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) pods were obtained and split into two batches for fermentation using two traditional methods: Fresh cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) pods were obtained from a local market and divided into two batches corresponding to two fermentation styles: a Korean kimchi-type fermentation (HG, Korean-style) and a Sichuan paocai-type fermentation (SC). All pods were washed under running tap water, drained, and trimmed to a uniform length of approximately 5-7 cm prior to use. For the HG fermentation, cowpea pods were first dry-salted with 2.5% (w/w) non-iodized NaCl (25 g salt per 1.0 kg pods) and then mixed thoroughly with a kimchi seasoning paste consisting, per kg of pods, of 50 g red chili powder, 30 g minced garlic, 20 g minced ginger, and 30 g salt-fermented seafood. This formulation approximates the composition of traditional kimchi seasonings and provides an initial inoculum of lactic acid bacteria. The seasoned cowpea pods were then packed firmly into sterile glass fermentation jars (approximately 1.0 kg pods per 1 L jar) so that the brine released from the salted pods was sufficient to immerse the vegetable material completely.

For the SC fermentation, cowpea pods were placed in sterile glass jars and completely submerged in a boiled and cooled brine prepared by dissolving 60 g non-iodized NaCl per liter of water (6% w/v) and flavoring the brine with 5 g Sichuan peppercorns, 10 g dried chili peppers, 20 g peeled garlic cloves, and 10 g fresh ginger slices per liter of brine to reproduce a typical paocai-style brine. No vinegar was added; thus, acidification in the SC treatment resulted solely from microbial fermentation. Immediately after assembling each jar (day 0), the initial pH of the brine in both HG and SC fermentations was measured in triplicate using a calibrated pH meter (model PHS-3C, manufacturer INASE Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The initial pH values were pH 6.15 ± 0.1 for HG and pH 6.15 ± 0.1 for SC, as reported in Section 3.1. In both fermentations, jars were filled so that the cowpea pods were fully covered by brine and were closed with fermentation airlocks or loosely sealed lids to allow CO2 to escape while limiting oxygen ingress, thereby maintaining an anaerobic pickling environment. Both HG and SC fermentations were carried out in triplicate (three independent jars for each treatment) at ambient temperature (~20–22 °C) for 10 days. The fermentation period of 10 days was chosen to allow substantial microbial development and acidification in both styles. During fermentation, jars were observed daily for signs of activity (e.g., bubbling of CO2 gas, brine turbidity) but were not opened until sampling to maintain anaerobic conditions. After 10 days, final pH was measured for each sample and samples of fermented cowpea pods and brine were collected aseptically for microbial analysis.

2.2. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

At each sampling time point, fermented cowpea samples were collected from each jar under aseptic conditions. Approximately 5.0 g of fermented cowpeas with adhering brine were transferred into a sterile stomacher bag and diluted with 45 mL of sterile 0.85% (w/v) NaCl solution. The mixture was vortexed vigorously for 2 min to detach microbial cells from the vegetable matrix and to obtain a uniform suspension.

Microbial genomic DNA was extracted from each fermented sample (combining solid and liquid phases) using a commercial DNA isolation kit suitable for complex food matrices (e.g., QIAGEN DNeasy PowerFood kit, Shanghai, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. This included bead-beating steps to ensure lysis of Gram-positive bacteria like LAB. The quality and concentration of extracted DNA were checked via agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry. The 16S rRNA gene V3–V4 region was amplified from each DNA sample using universal primers 341F and 806R which target the hypervariable regions 3 and 4 of the bacterial 16S gene. PCR amplification was performed in triplicate per sample, and amplicons were pooled, then purified using a PCR clean-up kit. Equimolar amounts of each sample’s amplicon were combined into a library and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform (paired-end 2 × 300 bp reads) at a commercial sequencing facility. Negative extraction control and a no-template PCR control were included through library preparation to check for reagent contamination. 16S rRNA gene (16S rDNA) amplicon libraries were prepared and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform (2 × 250 bp paired-end) by [Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China] following the manufacturer’s standard protocol for 16S metagenomic sequencing.

2.3. Sequence Data Processing and Microbial Community Analysis

Raw sequencing reads were processed using QIIME2 (v2022.8) for quality control and taxonomic assignment. Briefly, paired-end reads were merged and quality-filtered (discarding reads with Q < 20). Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were inferred using the DADA2 plugin in QIIME2, which denoises reads and removes chimeras. Representative sequences for each ASV were taxonomically classified by aligning to the SILVA 16S rRNA database (v138) with a 99% similarity threshold. Taxonomy was assigned at various ranks (phylum through genus); for consistency of comparison, we focused on genus-level composition in this study. The resulting ASV table was rarefied to an even depth (based on the sample with the fewest reads, approximately 25,000 reads per sample) to account for differences in sequencing depth when comparing diversity metrics.

Alpha diversity metrics including Shannon diversity index, Chao1 richness estimator, and Simpson’s index were calculated for each sample. Beta diversity was assessed by calculating Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between samples, which quantifies compositional differences based on relative abundances of ASVs. Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) was used to visualize beta diversity patterns. Statistical significance of beta-diversity clustering by fermentation type (HG vs. SC) was tested using PERMANOVA with 999 permutations. To identify genera driving differences between fermentations, we examined relative abundances of the top genera and visualized them in stacked bar plots and a heatmap. For the heatmap, genus abundances were log-transformed and Z-score normalized across samples to highlight high vs. low prevalence patterns, and hierarchical clustering was applied to both genera and samples.

2.4. Functional Profile Prediction (PICRUSt2) and Differential Analysis

To infer the functional potential of the microbial communities, we employed PICRUSt2 (Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States) on the 16S rRNA gene (16S rDNA) amplicon sequencing data. PICRUSt2 uses evolutionary modeling to predict genomic content (e.g., gene families) of the microbiota based on the taxa present. The ASV sequences were placed into a reference phylogenetic tree via the PICRUSt2 pipeline using EPA-NG and GAPP, and the abundances were normalized by predicted 16S copy number. From the predicted metagenomes, we extracted the following functional profiles for each sample: KEGG Orthologs (KOs), Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers, and MetaCyc metabolic pathways. The KO profiles provide specific gene functions, the EC profiles group genes by enzyme function, and the MetaCyc pathways aggregate functions into broader metabolic pathways.

For each of these functional categories (KO, EC, Pathway), we summed or averaged the predicted counts across replicate samples within the HG and SC groups to compare overall differences. We then performed differential abundance analysis to identify functions significantly enriched in one fermentation style vs. the other. For each KO, EC, and pathway entry, the mean proportion in HG vs. SC was compared using statistical tests and corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR). Features with an adjusted p-value < 0.1 were considered differentially abundant (given the exploratory nature of this analysis, a 10% FDR threshold was used to allow detection of potentially relevant trends). The log2 fold-change (log2[HG/SC]) for each feature was also calculated to indicate the direction and magnitude of differences. Results were visualized with volcano plots (for pathways) where each point represents a pathway’s log2 fold-change vs. its statistical significance (−log10 of adjusted p-value). Points were colored to denote enrichment in HG (blue) or SC (red) based on the direction of the difference. Additionally, we compiled a table of selected pathways that showed notable differences in abundance to highlight functional themes distinguishing the two fermentation styles.

All data analysis was conducted in R (v4.2) using packages phyloseq for microbial data handling, vegan for diversity analyses, and ggplot2 for visualization. Sequence data were deposited in a public sequence read archive, and the PICRUSt2 predicted profiles are provided in Supplementary Files.

3. Results

3.1. Microbial Diversity in Korean vs. Sichuan Fermentations

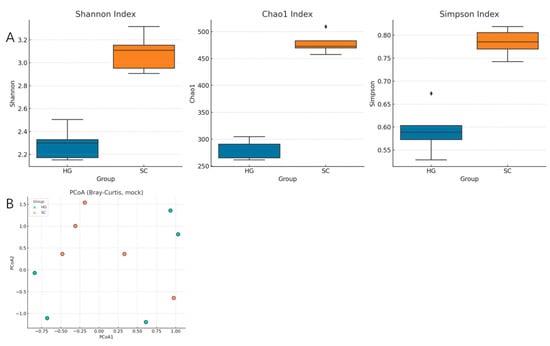

After 10 days of fermentation, clear differences in the microbial diversity were observed between the HG and SC cowpea kimchi. Alpha diversity indices (Shannon, Chao1, and Simpson) clearly differed between the two-fermentation style. Alpha diversity metrics were significantly different between the two groups (Figure 1A). Notably, the SC samples exhibited higher species diversity and richness compared to the HG samples. The Shannon diversity index of SC fermentations was significantly greater than that of HG (p < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank-sum test), indicating a more diverse and evenly distributed microbiota in the paocai-style cowpea. Similarly, Chao1 richness in SC was higher, suggesting that more distinct bacterial taxa were present in the Sichuan fermentation. Conversely, the Simpson index reflected that HG communities were more dominated by a few very abundant organisms, whereas SC communities were less dominated by single taxa. These results imply that the paocai method maintained a broader array of microorganisms, whereas the Korean kimchi method led to the dominance of a narrower selection of bacteria.

Figure 1.

Alpha and beta diversity of microbial communities in fermented cowpea pickles prepared using Sichuan (SC) and Korean (HG) fermentation processes. (A) Alpha diversity indices (Shannon, Chao1, and Simpson) showing richness and evenness differences between SC and HG samples. (B) Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity illustrating distinct clustering patterns between SC and HG microbial communities.

For beta diversity, in the PCoA based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities, PC1 explained 35.5% of the variance and PC2 explained 19.6%, with HG and SC samples forming two partially separated clusters (Figure 1B). The first two principal coordinates explained a substantial portion of the variance (PCo1 and PCo2 together >50% variance), and samples clearly clustered by fermentation type. All HG samples clustered tightly in one region of the ordination plot, while SC samples formed a distinct cluster apart from HG. This indicates that the overall community composition in Korean-style vs. Sichuan-style fermented cowpeas was markedly different. A PERMANOVA test confirmed that the differences in microbial profiles between HG and SC were statistically significant (PERMANOVA F-model = 5.21, p = 0.001), with fermentation method (HG vs. SC) explaining a major share of the community variation. These beta diversity results demonstrate that the choice of fermentation technique has a strong influence on the resulting microbiome. The tighter clustering of HG samples also suggests that the Korean method might produce more consistent communities compared to the SC method, which showed slightly more dispersion.

3.2. Microbial Community Composition and Key Taxa

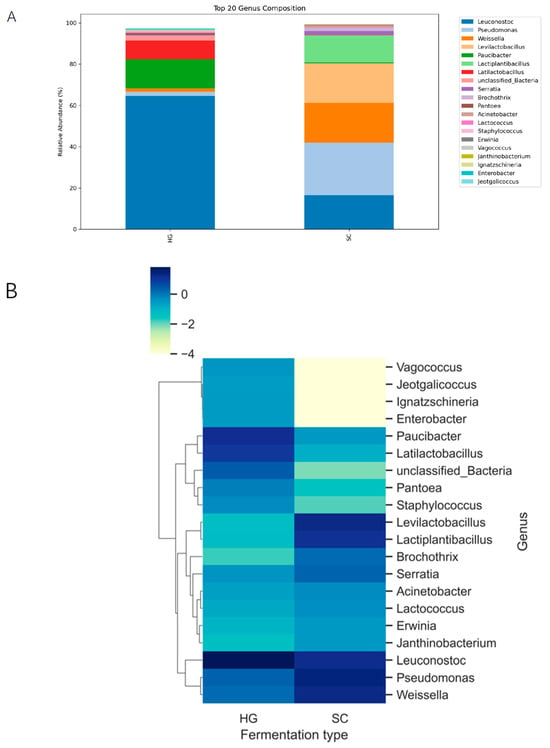

Despite differences in diversity, both fermentation styles were dominated by lactic acid bacteria (LAB), consistent with fermentation of plant material in saline conditions. Across all samples, the vast majority of sequencing reads (>90%) belonged to the phylum Firmicutes, primarily the family Leuconostocaceae and Lactobacillaceae. In the HG fermentations, the community was dominated by Leuconostoc, with Paucibacter and lactiplantibacillus as the next most abundant genera, whereas in the SC fermentations the microbiota was dominated by Levilactobacillus, Weissella and Pseudomonas (Figure 2A). These LAB genera are well-known core members of kimchi and other vegetable fermentations. However, the relative abundance of each genus varied significantly between the two styles. In the Korean-style cowpea kimchi (HG samples), Leuconostoc was particularly prominent in many samples, often comprising a large fraction of the community. Paucibacter was also abundant in HG. Actually, HG samples were dominated by Leuconostoc (up to ~50–60% of the reads), whereas in the SC group, Leuconostoc often rivaled or exceeded Lactobacillus in abundance. The differences suggest that the successional balance of LAB differed: HG fermentations may have been in a mid-fermentation stage where Leuconostoc was still abundant, while SC fermentations either allowed Lactobacillus to establish dominance or had environmental conditions favoring Lactobacillus.

Figure 2.

Genus-level taxonomic profiles of microbial communities in SC and HG fermented cowpea pickles. (A) Relative abundance of the top 20 bacterial genera across kimchi samples (bar plot). Each stacked bar represents an individual sample from either Korean kimchi (HG) or Sichuan kimchi (SC), with colors denoting different bacterial genera. The plot displays the top 20 genera ranked by overall abundance, expressed as a percentage of total sequencing reads. Distinct differences in microbial composition were observed between HG and SC groups. Notably, Leuconostoc, Lactobacillus, and Weissella were dominant in most samples, yet their relative proportions varied markedly between the two kimchi types, indicating divergent fermentation microbiota shaped by geographic and cultural practices. (B) Heatmap of the top 20 bacterial genera across kimchi samples (z-score normalized). The heatmap illustrates the distribution patterns of the top 20 bacterial genera across all samples. Each row corresponds to a genus and each column to a sample, with color intensity representing z-score normalized relative abundance. Clustering analysis reveals distinct microbial community structures between Korean and Sichuan kimchi, suggesting region-specific fermentation processes. The visualization highlights potential biomarker genera associated with each kimchi type and offers insights into fermentation ecology.

Besides these top three genera, minor differences in other bacterial groups were noted. The heatmap of the top 20 genera (Figure 2B) revealed some taxa present predominantly in one style or the other. Some low-abundance, salt-tolerant lactic acid bacteria were detected at low levels and appeared somewhat more in SC samples, possibly reflecting adaptation to the higher salt brine. Conversely, some Bacillus species (spore-forming fermenters) were occasionally observed in HG samples but remained at low abundance. Enterobacteriaceae counts decreased from approximately 2.1 × 103 CFU/g at the beginning of fermentation to below the detection limit (<101 CFU/g) in most jars by day 10. In the remaining positive samples, counts were reduced to 0.8 × 101 CFU/g, indicating that spoilage-associated Enterobacteriaceae were strongly suppressed in both HG and SC fermentations by the end of the process. In the genus-level heatmap (Figure 2B), HG and SC samples formed two main clusters. HG samples tended to group together, driven primarily by higher relative abundances of the dominant heterofermentative LAB shown, whereas SC samples clustered separately and were characterized by relatively higher levels of Lactobacillus and a distinct combination of minor genera. These microbial fingerprints suggest each fermentation style yields a characteristic microbiome composition, shaped by factors such as salt concentration, oxygen exposure, and ingredients (spices or starter microbes). Importantly, all dominant genera identified are lactic acid bacteria, underlining that both kimchi and paocai styles ultimately rely on LAB fermentation-though the particular LAB species and their proportions differ between Korean vs. Sichuan techniques.

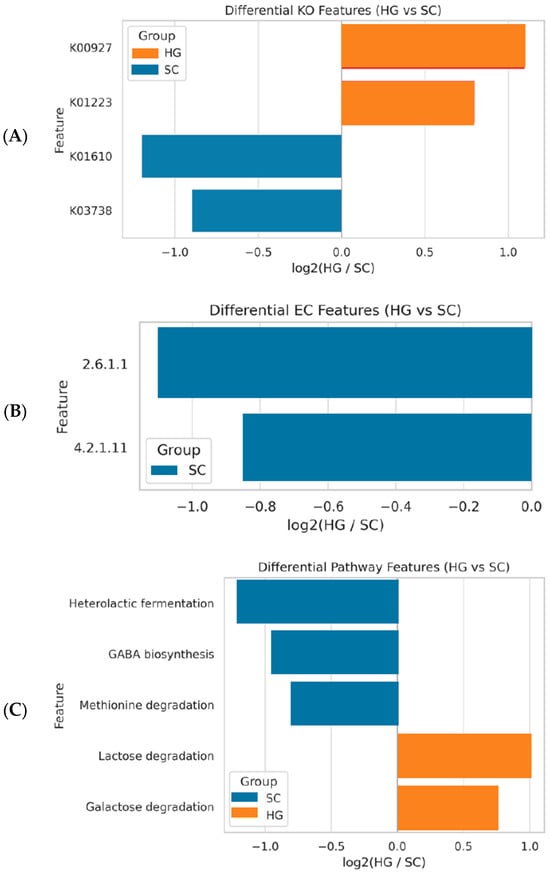

3.3. Predicted Functional Profiles (PICRUSt2) Reveal Metabolic Differences

We next examined whether the divergent microbiomes of HG and SC translate into different functional potentials, using PICRUSt2 to predict gene content. A total of 5992 KEGG Ortholog (KO) functions, 436 Enzyme Commission (EC) categories, and 369 MetaCyc pathways were predicted across all samples (including many core metabolic functions common to most bacteria). We focused on functions that showed the largest differences in relative abundance between the two fermentation styles. Figure 3 summarizes the key functional differences in terms of KOs (panel A), enzyme categories (B), and metabolic pathways (C) that were enriched in one group versus the other. Several clear trends emerged. Carbohydrate metabolism genes were more enriched in the Korean-style HG fermentation. HG samples showed higher abundance of genes annotated as glucosyltransferases (KO K00927) and β-galactosidase (lactase, KO K01223) compared to SC. Glucosyltransferases include enzymes like dextransucrase which certain Leuconostoc strains use to convert sugars (sucrose) into exopolysaccharides (dextran). β-Galactosidase is an enzyme that breaks down lactose or galactosyl-oligosaccharides. The enrichment of these in HG suggests that microbes in the Korean fermentation had greater capacity for breaking down complex sugars and possibly producing polysaccharides. This aligns with the observation that Leuconostoc (more prevalent in HG) often carries dextransucrase genes for slime production in fermentations, and some Lactobacillus in kimchi can utilize plant-derived galactosides.

Figure 3.

Differential functional features between Korean kimchi (HG) and Sichuan paocai (SC) as predicted by PICRUSt2. (A) KEGG Orthologs (KOs): HG samples were enriched in glucosyltransferase (K00927) and β-galactosidase (K01223), indicating enhanced carbohydrate metabolism, whereas SC samples showed enrichment in acetolactate synthase (K01610) and glutamate dehydrogenase (K03738), related to amino acid metabolism and flavor biosynthesis. (B) Enzyme Commission (EC) Numbers: SC samples showed elevated abundance of aspartate aminotransferase (EC 2.6.1.1) and fumarase (EC 4.2.1.11), suggesting enhanced organic acid and amino acid metabolism. (C) MetaCyc Pathways: SC samples were enriched in heterolactic fermentation, GABA biosynthesis, and methionine degradation pathways, while HG samples showed elevated lactose and galactose degradation pathways, indicating differential carbohydrate fermentation capacities. X-axis indicates the log2 fold change (HG vs. SC). Positive values indicate enrichment in HG; negative values indicate enrichment in SC.

Amino acid metabolism genes were comparatively enriched in the Sichuan-style SC fermentation. For example, SC samples had significantly higher levels of acetolactate synthase (KO K01610) and glutamate dehydrogenase (KO K03738) gene markers. Acetolactate synthase (ALS) is involved in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids (valine, leucine, isoleucine) and also in the formation of acetoin and diacetyl (flavor compounds) via the pyruvate metabolism pathway. Its higher representation in SC implies these microbes might produce more acetoin/diacetyl, contributing to buttery or malty notes. Glutamate dehydrogenase is involved in amino acid catabolism by converting glutamate to α-ketoglutarate; its enrichment in SC could reflect heightened turnover of amino acids such as glutamate, which may tie into GABA production or other pathways. Overall, the SC microbiome appears geared toward amino acid transformations and possibly secondary fermentative pathways that produce flavor metabolites.

Examining differences at the enzyme (EC) level further supported these patterns. Two enzyme functions were significantly higher in SC: aspartate aminotransferase (EC 2.6.1.1) and fumarase (EC 4.2.1.11). Aspartate aminotransferase interconverts aspartate and oxaloacetate (linked to amino acid and organic acid metabolism), suggesting SC microbes may more actively recycle nitrogen and participate in the malate-aspartate shuttle or related pathways. Fumarase, an enzyme of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle converting fumarate to malate, being higher in SC indicates greater engagement of the TCA cycle or related anaplerotic sequences by the SC community. This could correlate with the production of organic acids beyond lactic acid, such as succinate or malate fermentation pathways often seen in heterolactic fermentation. On the other hand, no EC was dramatically higher in HG than SC aside from those linked to sugar metabolism. This suggests that the metabolic scope of the HG microbiome was somewhat narrower, whereas SC had a broader metabolic activity including aspects of amino acid and organic acid metabolism.

At the pathway level, PICRUSt2 predicted notable differences in entire metabolic pathways between HG and SC fermentations (Figure 3C). The SC samples were enriched in pathways associated with heterolactic fermentation, GABA production, and sulfur-containing amino acid degradation, among others. Specifically, the pathway for heterolactic fermentation (sugar fermentation yielding lactic acid, ethanol/acetic acid, and CO2) had a higher abundance in SC, consistent with the higher presence of heterofermentative LAB like Leuconostoc and Weissella in some SC samples. This is somewhat intriguing, as heterofermentative LAB were also abundant in HG; the difference might be due to SC conditions favoring sustained heterolactic metabolism. Additionally, GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) biosynthesis via the glutamate decarboxylation pathway was enriched in SC fermentations relative to HG. Many LAB, such as Lactobacillus plantarum, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, etc., have a glutamate decarboxylase enzyme to produce GABA, especially under acidic stress. The higher potential for GABA production in SC suggests that those microbes were either under conditions that induce this pathway (e.g., higher salt or lower pH prompting acid resistance mechanisms) or that SC harbored species particularly proficient at GABA production. GABA is a health-promoting compound that can act as a neurotransmitter modulator; its presence is a valued functional property in fermented foods. Another pathway with greater representation in SC was methionine degradation (MetaCyc pathway for methionine to volatile sulfur compounds). LAB and some other fermenters can degrade the amino acid methionine to compounds like methanethiol and other sulfur volatiles, which contribute to the characteristic pungent, savory aroma in fermented and aged foods. The enrichment of methionine catabolic pathways in SC suggests a potential for more complex flavor development (sulfur notes) in the paocai-style cowpea, possibly due to a more diverse microbiome including microbes that metabolize amino acids.

In contrast, HG samples showed elevated pathway abundance for lactose and galactose degradation. Even though lactose was not a major sugar in the vegetable substrate, this result likely reflects the presence of pathways like the Leloir pathway for galactose utilization or β-galactosidase activity in the HG microbiota. It indicates a strong capacity to break down galactose or galactosides, which could be relevant if any galactose-containing sugars (e.g., raffinose, stachyose from cowpeas) are present; efficient fermentation of those sugars could make the final product less flatulence-inducing and more digestible. The emphasis on lactose/galactose utilization in HG aligns with the above-mentioned KO results (β-galactosidase enrichment) and suggests the HG LAB were attuned to ferment available carbohydrates thoroughly. Meanwhile, fewer amino acid or alternate pathways were highlighted in HG, implying that the HG community might rely predominantly on simple carbohydrate fermentation, with less metabolic branching into amino acid transformations.

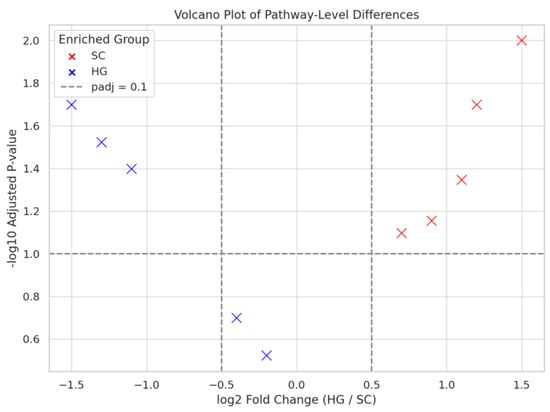

3.4. Differential Pathway Analysis and Key Metabolic Insights

To identify the most statistically significant functional differences, we performed a differential abundance analysis on the predicted MetaCyc pathways and visualized the results in a volcano plot (Figure 4). Each point in the volcano represents a metabolic pathway; those towards the extremes of the x-axis have large differences in abundance between HG and SC, and those high on the y-axis are supported by low p-values after FDR correction. Using a cutoff of adjusted p < 0.1 and log2 fold-change > 0.5 in magnitude as thresholds for noteworthy differences, a number of pathways stood out. The majority of pathways passing these criteria were enriched in the SC group (plotted as red points in Figure 4), reinforcing that SC had a broader array of upregulated functions compared to HG. In fact, more pathways were higher in SC even if not all reached significance, whereas relatively fewer pathways were higher in HG and significant.

Figure 4.

Differential abundance analysis of predicted pathways between SC and HG samples.

Among the significantly enriched pathways in SC were those related to arginine and ornithine metabolism, and butyrate production. For example, the arginine degradation pathway, which converts arginine to ornithine, ammonia, and ATP, showed higher relative abundance in SC samples (log2 fold-change SC/HG > 1, p < 0.05). This pathway is utilized by many LAB as a secondary energy-generating mechanism, and its enrichment suggests that SC LAB might be actively using arginine. The by-products of this pathway, such as ornithine and ammonia, can affect flavor. Its presence in SC might contribute to a different flavor profile or slight moderation of acidity in paocai-style fermentations.

Another notable trend was the higher predicted abundance of pathways for glutamate fermentation to butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids in SC. While classical LAB do not typically produce butyrate, the PICRUSt2 results suggest that SC communities might include or be functionally akin to some obligate anaerobes capable of butyric acid fermentation. It is possible that certain anaerobic spore-formers were present at low levels in SC due to the environmental conditions, such as anoxic, vegetable-rich medium, perhaps introduced from the raw materials or brine. The detection of a butyrate-producing pathway is intriguing because butyrate is a beneficial compound for human gut health. If the paocai-style fermentation indeed harbors butyrate-producing bacteria, consuming such fermented cowpea might confer added prebiotic or postbiotic benefits by delivering those organisms or their metabolites to the gut. In contrast, this butyrate pathway was not enriched in HG, implying it was either absent or in lower abundance, likely because the HG environment might inhibit butyrate-producing clostridia or because the community was overwhelming LAB.

On the flip side, pathways that were more abundant in HG (blue points in Figure 4) tended to be related to carbohydrate metabolism, as previously noted, and none of them showed extremely large fold-changes. One pathway that appeared slightly enriched in HG was mannitol fermentation, which consistent with LAB like Leuconostoc producing mannitol from fructose, common in kimchi, though this difference was not as statistically significant given that some SC microbes also can produce mannitol. Overall, significant HG-enriched pathways were few, reinforcing that HG communities mainly differ in degree rather than presence/absence of most core fermentative functions.

In addition to statistically significant features, we also compiled biologically relevant pathway differences that might not meet the strict FDR cutoff but are important for understanding the fermentation differences (Table 1). The table summarizes top pathway-level features showing potential biological trends, even if not meeting strict significance thresholds. These trends suggest functional differences between the SC and HG fermentation processes, including short-chain fatty acid production and flavor-related amino acid metabolism. This includes pathways for various flavor-related compounds. For instance, diacetyl biosynthesis (via the acetolactate pathway) was higher in SC in tandem with the acetolactate synthase gene finding, suggesting SC fermentations might yield more diacetyl, a compound contributing a buttery aroma. Similarly, ethanol production pathways were relatively higher in SC, aligning with the heterolactic pathway enrichment and possibly contributing to the aromatic profile of SC ferments. Another trend was the biogenesis of exopolysaccharides, such as dextran from sucrose, being higher in HG, which correlates with the presence of glucosyl transferase genes in HG Leuconostoc; this could influence the texture of the kimchi brine, as dextran can thicken liquids.

Table 1.

Key PICRUSt2-predicted MetaCyc pathways differentiating SC and HG cowpea fermentations at day 10. Exact log2 fold-change and adjusted p-values are shown in Figure 4; here we summarize the direction of enrichment and biological interpretation.

Positive log2FC(HG vs. SC) indicates higher predicted pathway abundance in HG; negative values indicate higher abundance in SC, consistent with the definition used in Figure 4. All pathways listed as “Meets volcano threshold” satisfy |log2FC(HG vs. SC)| > 0.5 and FDR-adjusted p < 0.10 in the PICRUSt2 differential-abundance analysis; trend-level pathways are biologically relevant but fall outside this strict cutoff.

Collectively, the functional analysis highlights that fermentation type not only changes which microbes are present but also what they are potentially doing metabolically. The Sichuan paocai-style fermentation showed a richer functional potential, especially in pathways tied to flavor generation and health-related metabolites, such as GABA or butyrate. The Korean kimchi-style fermentation displayed a strong focus on efficient sugar utilization and lactic acid production, which ensures rapid acidification and preservation, possibly at the cost of some flavor complexity.

The volcano plot illustrates the differential abundance of predicted functional pathways between SC and HG samples. Each point represents a pathway, with red circles indicating enrichment in SC and blue circles indicating enrichment in HG. Dashed lines mark the threshold for log2 fold change > 0.5 and adjusted p-value < 0.1

4. Discussion

This study compared the microbiota of cowpea pod fermentations prepared using a Korean kimchi-type process (HG) and a Sichuan paocai-type process (SC), providing a microbiome-level view of how two culturally distinct brining practices shape community structure. After 10 days of fermentation, both processes yielded stable, lactic acid bacteria–dominated communities, but they differed in alpha diversity, beta diversity and the relative contributions of key genera. These patterns indicate that process parameters such as salt concentration, presence or absence of a seasoning paste, and use of a pre-acidified brine act as strong ecological filters that select different but reproducible microbial assemblages.

In terms of within-sample diversity, SC fermentations exhibited higher richness and/or evenness than HG, as reflected by alpha-diversity indices (Observed ASVs, Chao1, Shannon and Simpson). This suggests that the paocai-style brine, with its higher salt content and simpler initial matrix, can support a broader range of taxa than the kimchi-style treatment. The principal coordinates analysis further showed a clear separation between HG and SC samples, indicating that the two fermentation styles occupy distinct regions of compositional space. Despite these differences, replicate jars within each group clustered closely together, underscoring the robustness of both fermentation protocols.

At the taxonomic level, both processes were dominated by lactic acid bacteria, but the balance among genera differed between HG and SC. SC fermentations were characterized by a higher relative abundance of Lactobacillus (sensu lato), consistent with previous reports that paocai brines often favor lactobacilli after the early stages of fermentation [37]. In contrast, HG fermentations maintained appreciable proportions of Leuconostoc and Weissella alongside Lactobacillus, in line with the heterofermentative LAB consortia frequently reported in kimchi. These differences likely reflect the distinct physicochemical trajectories created by the two processes (e.g., different salt levels, buffering capacity and release of plant nutrients), which in turn modulate competitive interactions and succession among LAB and minor taxa.

To gain insight into the potential functional consequences of these taxonomic differences, we applied PICRUSt2 to infer metagenome functions from 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing data. The resulting predicted profiles suggested that SC communities may be relatively enriched in pathways related to amino acid metabolism and certain energy-related routes, whereas HG communities showed higher predicted contributions from glycolysis and other core carbohydrate-fermentation pathways. These trends imply that the SC microbiota could harbor a broader repertoire of enzymes for transforming amino acids and related substrates, while the HG microbiota may channel a larger fraction of its activity into primary carbohydrate conversion. However, it is important to emphasize that these are inferred functional capacities based on reference genomes rather than directly measured gene content or metabolic fluxes.

Accordingly, the PICRUSt2 results in this study should be regarded as hypothesis-generating rather than definitive evidence of functional activity. In particular, although some predicted pathways are consistent with metabolic routes associated with the formation of organic acids or amino acid–derived compounds in fermented vegetables, our data do not demonstrate that these compounds were produced, nor do they quantify any specific metabolites. We did not measure GABA, short-chain fatty acids, volatile compounds or texture-related polymers in the cowpea fermentations, and therefore we cannot make claims about actual metabolite levels, sensory profiles or health effects. Any potential implications for flavor, texture or host physiology must be tested in future work using targeted metabolomics, texture analysis, sensory evaluation and appropriate in vitro or in vivo models.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the functional analysis relies on 16S rRNA gene sequencing coupled with PICRUSt2, which cannot capture strain-level variation, horizontal gene transfer, or actual gene expression and therefore provides only an approximate picture of functional potential. Second, physicochemical measurements were limited to pH and basic fermentation conditions; more detailed monitoring of parameters such as organic acid profiles, residual sugars and salt gradients would help to link community dynamics to the evolving environment. Third, we focused on a single vegetable substrate (cowpea pods) and a single fermentation time point per process; additional substrates, time-course sampling and replicate batches from different production sites would be needed to generalize the findings more broadly.

Despite these limitations, the present work provides a useful starting point for understanding how Korean-style and Sichuan-style fermentations structure the microbiota of cowpea-based products. By combining community profiling with cautiously interpreted functional predictions, our data highlight that distinct, yet lactic acid–dominated, ecosystems can be established on the same substrate simply by altering brining style and seasoning strategy. Future studies that integrate metagenomics, metabolomics and detailed physicochemical characterization will be needed to verify the predicted functions, to quantify key metabolites and to evaluate how different process parameters influence the sensory and potential health-related properties of cowpea fermentations.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully compared the effect of two distinct fermentation techniques—Korean kimchi-style (HG) and Sichuan paocai-style (SC)-on the cowpea-based microbial ecosystem and its associated functional potential.

Fermentation Technique Shapes the Microbiome: The fermentation technique served as a strong determinant of microbial structure. The SC method resulted in a significantly higher microbial diversity (alpha diversity) than the HG method, and beta diversity analysis confirmed that the communities clustered separately based on the fermentation style.

Dominant Microbes Differ: The SC fermentation was characterized by the dominant presence of Pediococcus and Lactobacillus, while the HG fermentation was mainly driven by the genus Leuconostoc. These differences indicate that the specific fermentation parameters (e.g., salt concentration, accessories) act as powerful selection pressures.

Functional Potential Highlights Health and Flavor: Functional inference (PICRUSt2) revealed significant metabolic differences between the two styles. Specifically, the SC-fermented cowpea kimchi showed a clear enrichment of pathways related to the biosynthesis of Butanoate (Butyrate) and GABA. These findings suggest that SC fermentation potentially offers enhanced gut health benefits compared to the HG style.

Novel Application: This research not only elucidates the ecological differences induced by culturally distinct techniques but also successfully establishes cowpea as a viable substrate for producing functional fermented foods rich in beneficial metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and GABA.

In summary, this work provides crucial molecular evidence linking traditional fermentation practices to distinct microbial structures and associated health-promoting functions, offering valuable insights for the targeted development of probiotic starter cultures and novel functional foods.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation12010010/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.L., B.S. and S.-o.K.; methodology, L.W., B.S., and R.L.; software, L.W.; validation, L.W. and R.L.; formal analysis, B.S. and S.-o.K.; investigation, L.W. and R.L.; resources, R.L.; data curation, L.W. and R.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W., B.S., and R.L.; writing—review and editing, B.S., and R.L.; visualization, L.W.; supervision, R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HG | Korean-style (Korean kimchi-style fermentation) |

| SC | Sichuan paocai-style fermentation |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| 16S rRNA | 16S ribosomal RNA |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| QIIME2 | Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2 |

| DADA2 | Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm 2 |

| ASV | Amplicon sequence variant |

| SILVA | SILVA 16S rRNA database (v138) |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinates Analysis |

| PERMANOVA | Permutational multivariate analysis of variance |

| PICRUSt2 | Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States 2 |

| KO | KEGG Ortholog |

| EC | Enzyme Commission |

| MetaCyc | MetaCyc metabolic pathways |

| FDR | False discovery rate (Benjamini–Hochberg) |

| GABA | γ-Aminobutyric acid |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

References

- Yadav, S.; Saini, P.; Iqbal, U.; Ahmed, M. Fermented Fruits and Vegetables. In Fruits and Vegetables Technologies: Postharvest Processing and Packaging; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 343–393. [Google Scholar]

- Xian, S.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; He, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Shen, G.; Chen, A. Analysis of Physicochemical Characteristics, Flavor, and Microbial Community of Sichuan Industrial Paocai Fermented by Traditional Technology. Foods 2025, 14, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wei, W.; Tang, L.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, W. Characterization of Aroma and Bacteria Profiles of Sichuan Industrial Paocai by HS-SPME-GC-O-MS and 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surya, R. Fermented Foods of Southeast Asia Other than Soybean-or Seafood-Based Ones. J. Ethn. Foods 2024, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Whon, T.W.; Roh, S.W.; Jeon, C.O. Unraveling Microbial Fermentation Features in Kimchi: From Classical to Meta-Omics Approaches. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 7731–7744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ao, X.; Yan, J.; Chen, C.; Zhao, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, K.; Chen, S.; He, L. Isolation and Identification of the Spoilage Microorganisms in Sichuan Homemade Paocai and Their Impact on Quality and Safety. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 2939–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Qian, Y.; Tao, Y.; She, X.; Li, Y.; Che, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, L. Influence of Oxygen Exposure on Fermentation Process and Sensory Qualities of Sichuan Pickle (Paocai). RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 38520–38530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Jia, J.; Zhao, H.; Wu, C. Changes and Driving Mechanism of Microbial Community Structure during Paocai Fermentation. Fermentation 2022, 8, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.Y.; Bae, M.; Kim, M.J.; Jang, H.-Y.; Jung, S.; Lee, J.-H.; Hwang, I.M. Rapid Quantitative Analysis of Metabolites in Kimchi Using LC-Q-Orbitrap MS. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 3896–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, D.; Surya, R.; Nurkolis, F.; Surya, E.; Thinthasit, A.; Kamal, N.; Oh, J.-S.; Benchawattananon, R. Hepatoprotective Effects of Ethnic Cabbage Dishes: A Comparison Study on Kimchi and Pao Cai. J. Ethn. Foods 2023, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Yang, X.; Hu, C.; Wei, B.; Xu, F.; Guo, Q. Fermentation Performance Evaluation of Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains for Sichuan Radish Paocai Production. Foods 2024, 13, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.; Kim, Y.B.; Park, S.E.; Lee, S.H.; Roh, S.W.; Son, H.S.; Whon, T.W. Does Kimchi Deserve the Status of a Probiotic Food? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 6512–6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Jeon, H.S.; Yoo, J.Y.; Kim, J.H. Some Important Metabolites Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria Originated from Kimchi. Foods 2021, 10, 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Fan, Y.; Chen, H. Natural Flocculant Chitosan Inhibits Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production in Anaerobic Fermentation of Waste Activated Sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 403, 130892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Kharousi, Z.S. Highlighting Lactic Acid Bacteria in Beverages: Diversity, Fermentation, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Foods 2025, 14, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landaud, S.; Helinck, S.; Bonnarme, P. Formation of Volatile Sulfur Compounds and Metabolism of Methionine and Other Sulfur Compounds in Fermented Food. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 77, 1191–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.W.; Nguyen, Q.A.; Chanmuang, S.; Lee, S.B.; Kim, B.M.; Lee, H.J.; Jang, G.J.; Kim, H.J. Effects of Kimchi Intake on the Gut Microbiota and Metabolite Profiles of High-Fat-Induced Obese Rats. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacka, K.; Sozański, T.; Kucharska, A.Z. Fermented Fruits, Vegetables, and Legumes in Metabolic Syndrome: From Traditional Use to Functional Foods and Medical Applications. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Miao, K.; Niyaphorn, S.; Qu, X. Production of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid from Lactic Acid Bacteria: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogeswara, I.B.A.; Maneerat, S.; Haltrich, D. Glutamate Decarboxylase from Lactic Acid Bacteria—A Key Enzyme in GABA Synthesis. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.C.; Paramithiotis, S.; Thekkangil, A.; Nethravathy, V.; Rai, A.K.; Martin, J.G.P. Food Fermentation and Its Relevance in the Human History. In Trending Topics on Fermented Foods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Nami, Y.; Ranjbar, M.S.; Aval, M.M.; Haghshenas, B. Harnessing Lactobacillus-Derived SCFAs for Food and Health: Pathways, Genes, and Functional Implications. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 9, 100496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.; De Paepe, K.; Van de Wiele, T. Postbiotics and Their Health Modulatory Biomolecules. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zheng, J.; Han, X.; Yang, S.; Cheng, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, W.; Lu, Y. Advances in Low-Lactose/Lactose-Free Dairy Products and Their Production. Foods 2023, 12, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fara, A.; Sabater, C.; Palacios, J.; Requena, T.; Montilla, A.; Zárate, G. Prebiotic Galactooligosaccharides Production from Lactose and Lactulose by Lactobacillus Delbrueckii Subsp. Bulgaricus CRL450. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 5875–5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahala, M.; Ikonen, I.; Blasco, L.; Bragge, R.; Pihlava, J.M.; Nurmi, M.; Pihlanto, A. Effect of Lactic Acid Bacteria on the Level of Antinutrients in Pulses: A Case Study of a Fermented Faba Bean–Oat Product. Foods 2023, 12, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.M.; Mendes-Ferreira, A.; Benevides, C.M.; Melo, D.; Costa, A.S.; Mendes-Faia, A.; Oliveira, M.B.P. Effect of Controlled Microbial Fermentation on Nutritional and Functional Characteristics of Cowpea Bean Flours. Foods 2019, 8, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanalibaba, P.; Çakmak, G.A. Exopolysaccharides Production by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Open Access 2016, 2, 10–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Ahn, H.J.; Kim, S.; Chung, C.H. Dextran-like Exopolysaccharide-Producing Leuconostoc and Weissella from Kimchi and Its Ingredients. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 22, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorau, R.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Jensen, P.R.; Solem, C. Efficient Production of α-Acetolactate by Whole Cell Catalytic Transformation of Fermentation-Derived Pyruvate. Microb. Cell Factories 2019, 18, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, S.M.; Moreno-Ruiz, A.; Tres, A.; Moreno-Yerro, N.; Arrubla, P.; Gastón-Lorente, M.; Mohedano, M.L.; Virto, R.; Fratebianchi, D. Butter Aroma Compounds in Plant-Based Milk Alternatives through Fermentation: Screening of Potential Starter Cultures and Enhanced Production in Oat Milk with Lactococcus cremoris. LWT 2025, 223, 117754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Li, J.; Du, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Wan, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, N.; Li, Q.; Zhao, N.; et al. Aroma-Producing Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LYA31 and Wickerhamomyces anomalus YYB24: Insight into Their Contribution to Paocai Fermentation. LWT 2025, 220, 117541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Lv, M.; Shao, Z.; Hungwe, M.; Wang, J.; Bai, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Geng, W. Metabolism Characteristics of Lactic Acid Bacteria and the Expanding Applications in Food Industry. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 612285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Mbadinga, U.F.N.; Wen, S.; Hou, X.; Wang, J. Flavor Formation through Lactic Acid Bacteria Metabolism in Traditional Chinese Fermented Vegetable Products. J. Ethn. Foods 2025, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnarme, P.; Psoni, L.; Spinnler, H.E. Diversity of L-Methionine Catabolism Pathways in Cheese-Ripening Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 5514–5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Lee, J.-H. Characterization of Arginine Catabolism by Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Kimchi. Molecules 2018, 23, 3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, G.; Tang, Y.; Li, H.; Shen, W.; Wang, M.; Liu, S.; Qin, W.; Zhang, Q. Effects of Temperature on Paocai Bacterial Succession Revealed by Culture-Dependent and Culture-Independent Methods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 317, 108463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.