A Simple, Rapid Assembly Method for Integrating Different Gene Order into Synthetic Operons

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Strains, Plasmids and Culture Conditions

2.2. Plasmid Construction

2.3. Fluorescence Analysis Methods

2.4. Analysis Method

3. Results

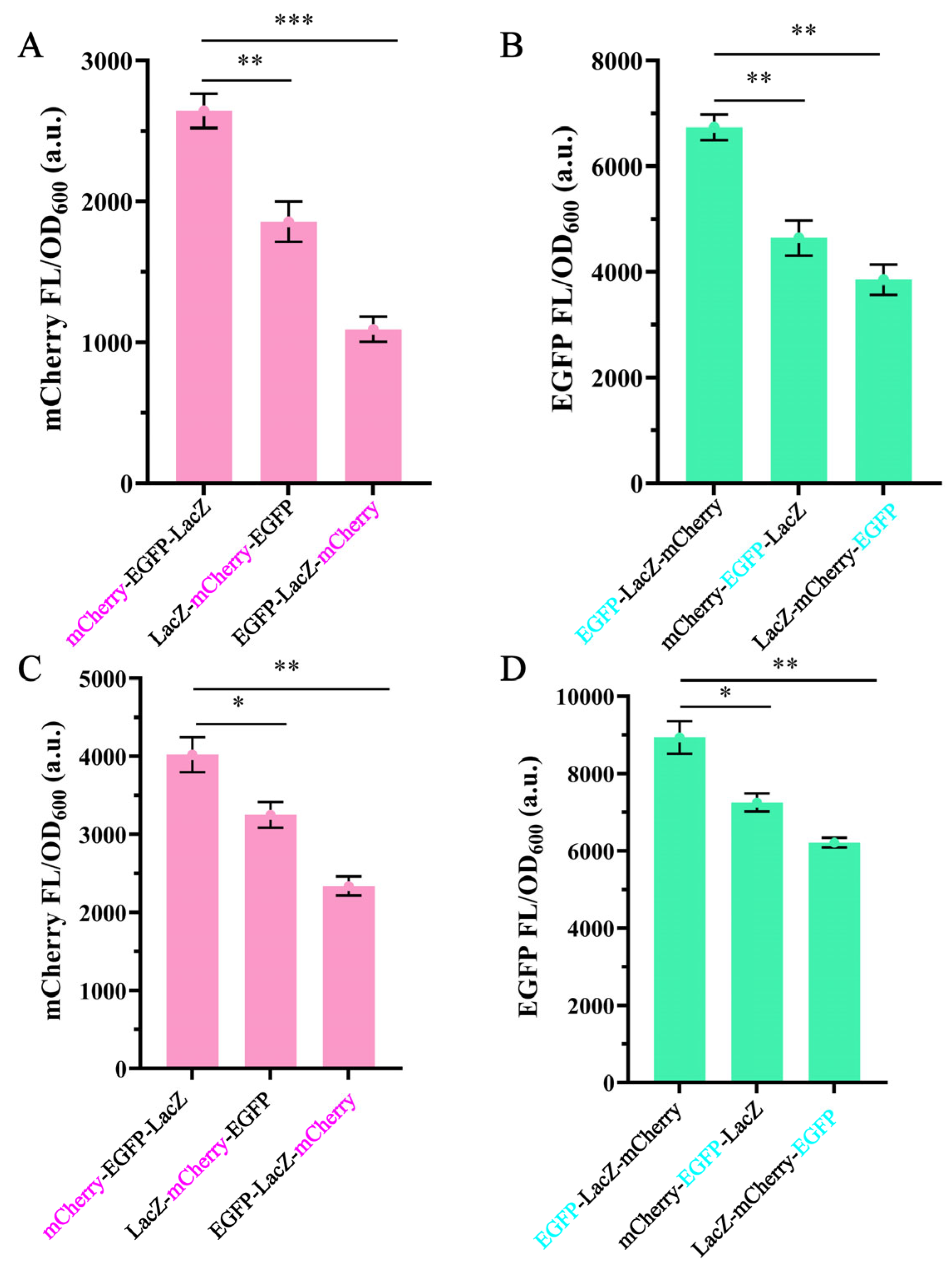

3.1. The Effect of Gene Position in Operons on Gene Expression

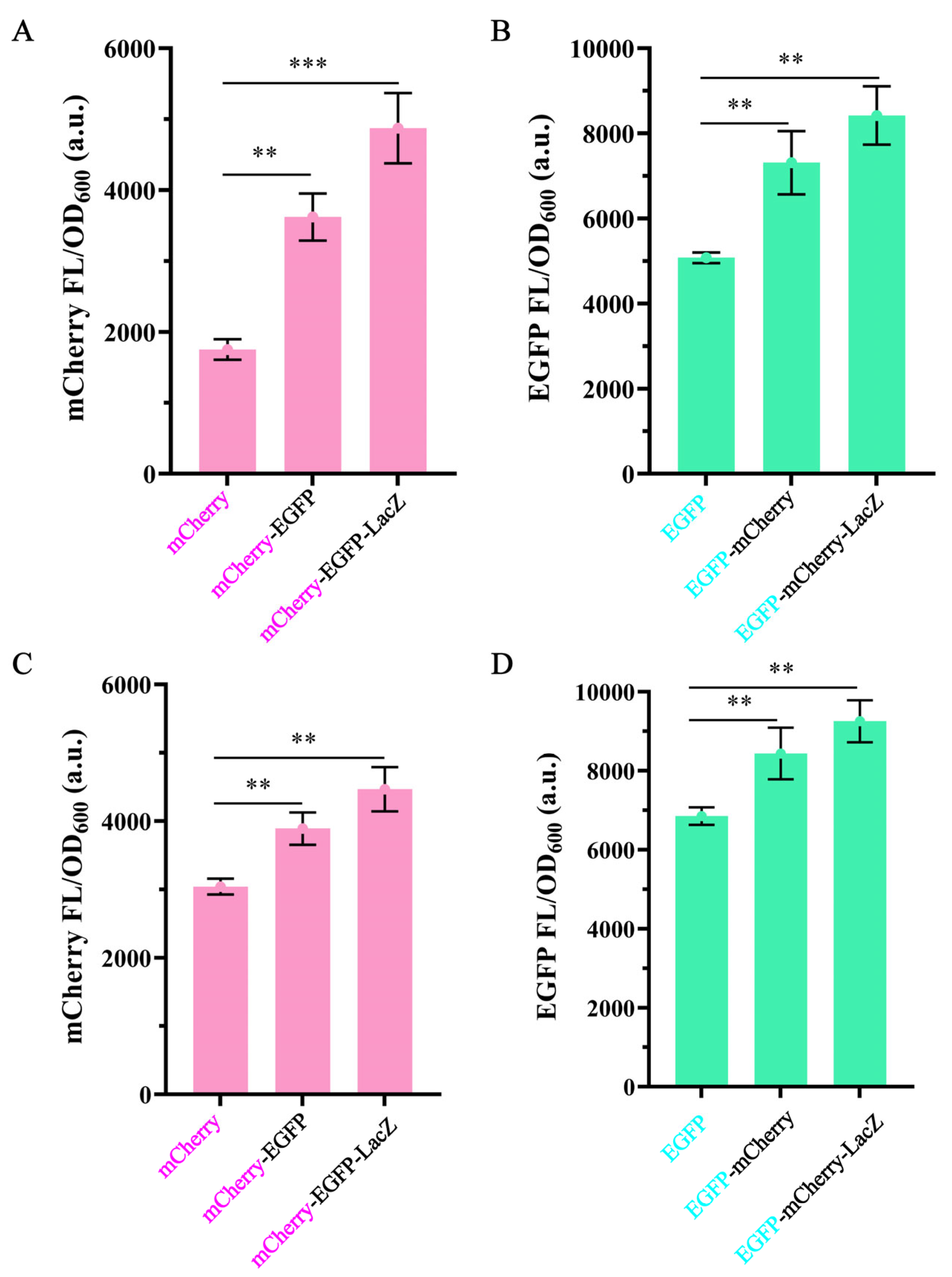

3.2. The Effect of Operon Length on Gene Expression

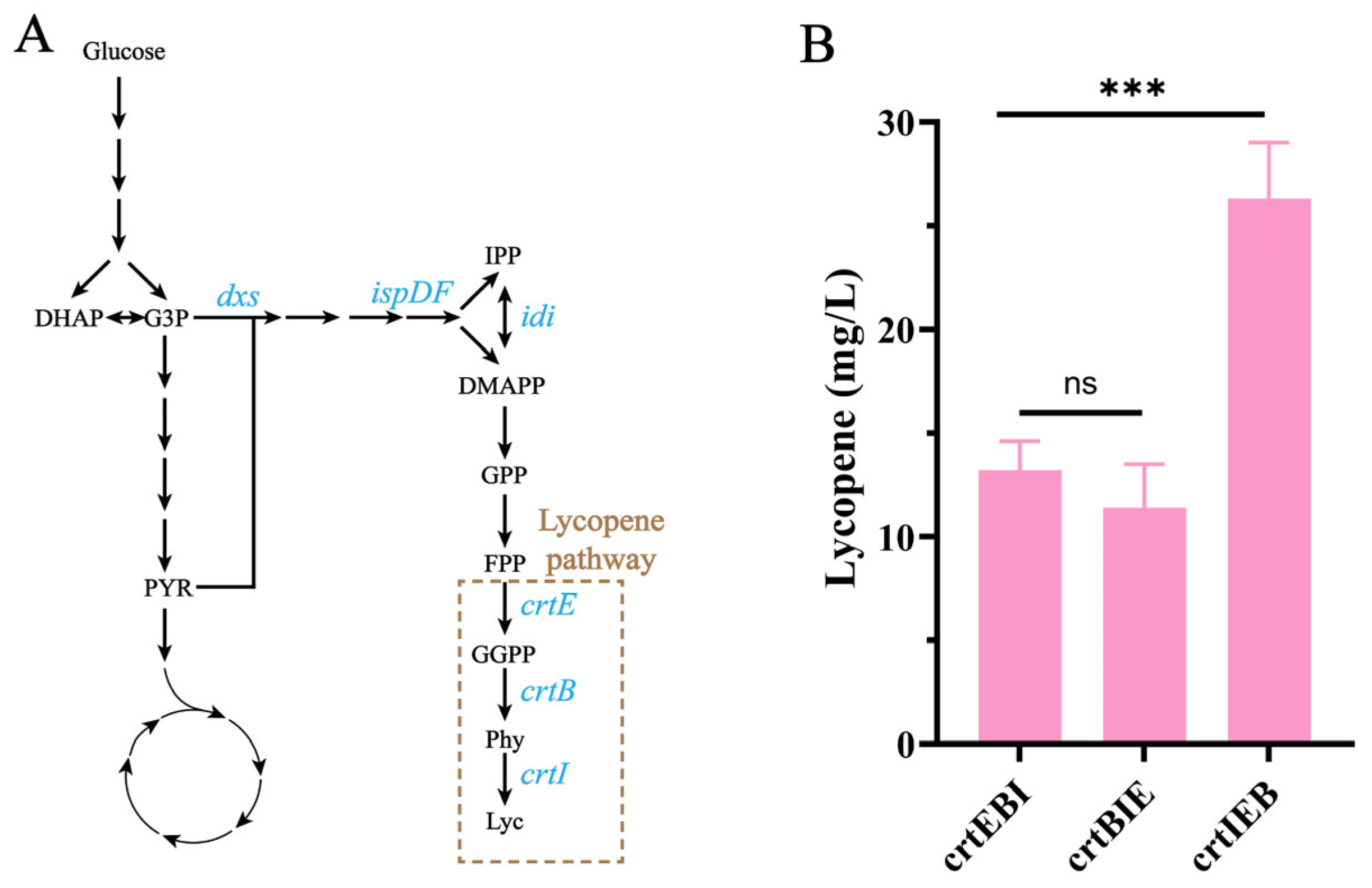

3.3. The Order of Key Lycopene Synthesis Genes Influences Lycopene Production

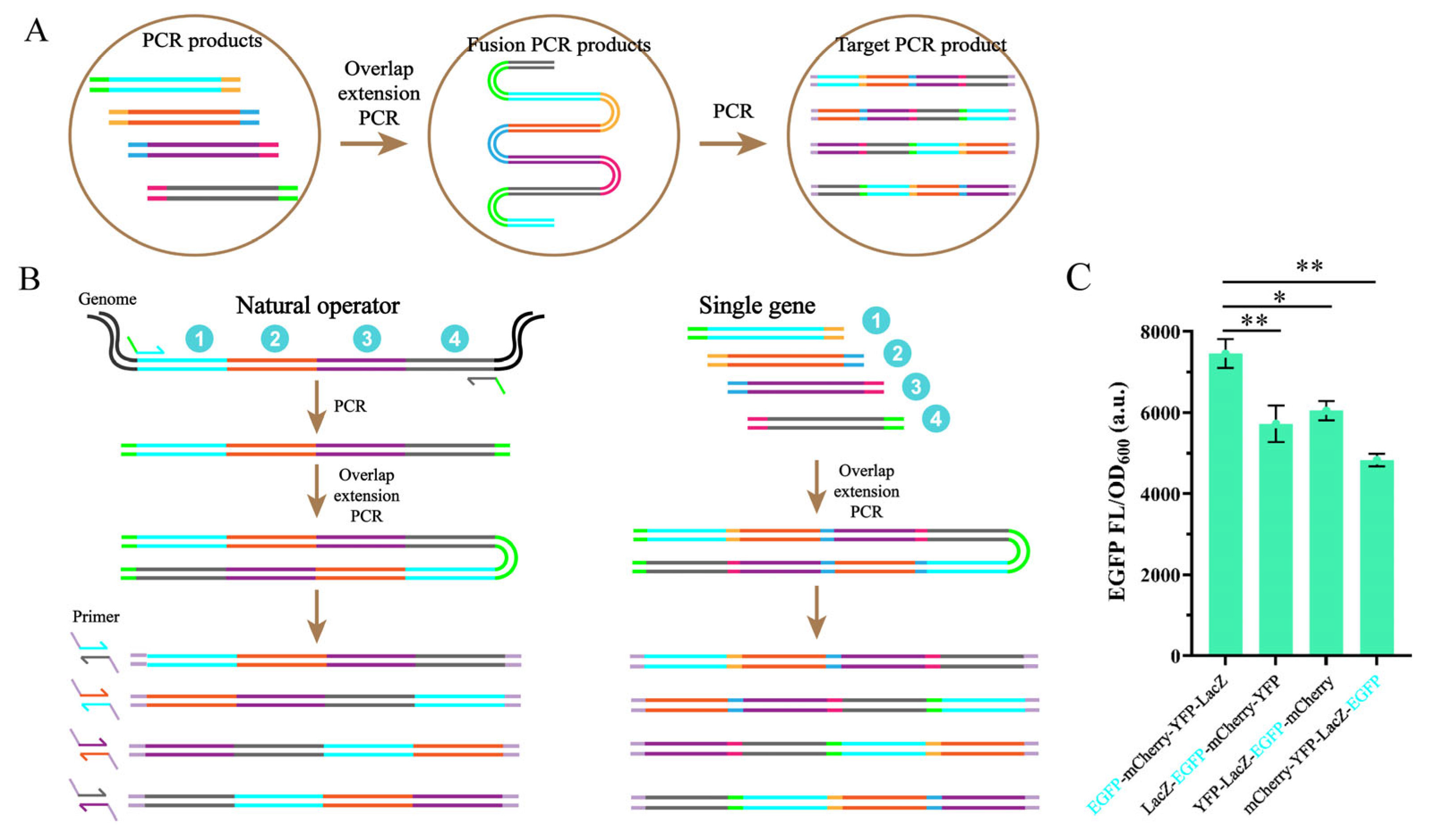

3.4. A PCR Method for Altering the Order of Operon

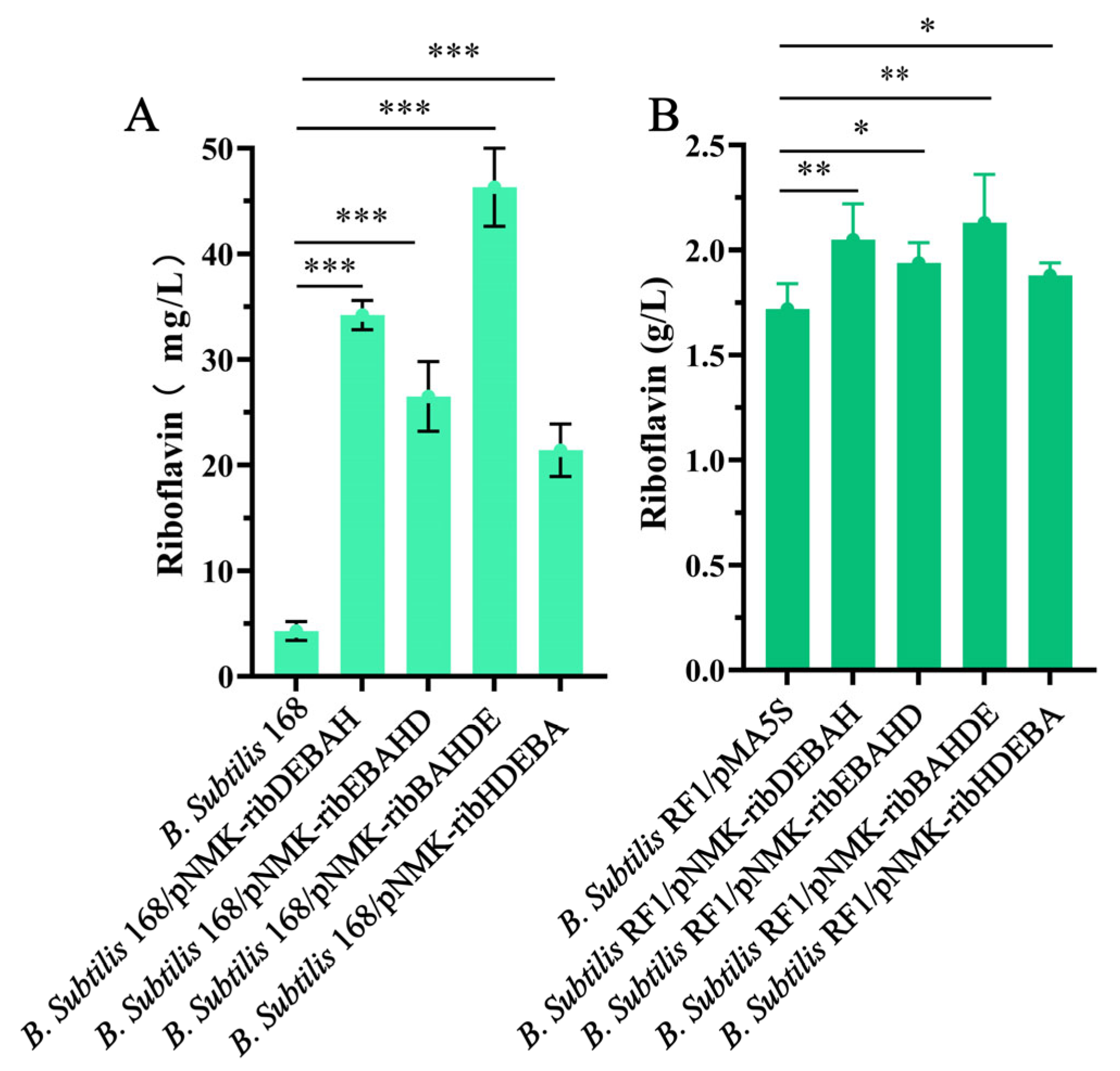

3.5. Construction of Synthetic Rib Operons Using HTPCR Methods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rocha, E.P. The organization of the bacterial genome. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2008, 42, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, M.N.; Arkin, A.P.; Alm, E.J. The life-cycle of operons. PLoS Genet. 2006, 2, e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, F.; Monod, J.L. On the Regulation of Gene Activity. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1961, 26, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, D.H.; Rouskin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.W.; Weissman, J.S.; Gross, C.A. Operon mRNAs are organized into ORF-centric structures that predict translation efficiency. eLife 2017, 6, e22037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Luo, H.; Gao, F. Position preference of essential genes in prokaryotic operons. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandekar, T.; Snel, B.; Huynen, M.; Bork, P. Conservation of gene order: A fingerprint of proteins that physically interact. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998, 23, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro, E.M.; Mah, N.; Moreno-Hagelsieb, G.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A. The pseudogenes of Mycobacterium leprae reveal the functional relevance of gene order within operons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, K.; Hurst, L.D.; Papp, B. Stochasticity in protein levels drives colinearity of gene order in metabolic operons of Escherichia coli. PLoS Biol. 2009, 7, e1000115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, D.; Singh, A.K.; Pakrasi, H.B.; Wangikar, P.P. A global analysis of adaptive evolution of operons in cyanobacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2013, 103, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.S.; Ghai, R.; Rashmi; Kalia, V.C. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 87, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, C.M.; Sargent, F. Design and characterisation of synthetic operons for biohydrogen technology. Arch. Microbiol. 2017, 199, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Wang, H.; Tang, J.; Bi, C.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X. Coordinated Expression of Astaxanthin Biosynthesis Genes for Improved Astaxanthin Production in Escherichia coli. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 14917–14927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Luan, J.; Cui, Q.; Duan, Q.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Li, R.; Li, A.; Shen, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Enhanced Heterologous Spinosad Production from a 79-kb Synthetic Multioperon Assembly. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Xia, M.; Fang, H.; Xu, F.; Wang, S.; Zhang, D. De novo engineering riboflavin production Bacillus subtilis by overexpressing the downstream genes in the purine biosynthesis pathway. Microb. Cell Factories 2024, 23, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, M.; Zheng, T.; Wang, Z.; Lai, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; Meng, S.; Xu, W.; Zhao, C.; et al. PHB production from food waste hydrolysates by Halomonas bluephagenesis Harboring PHB operon linked with an essential gene. Metab. Eng. 2023, 77, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroe, A.; Tsuge, K.; Nomura, C.T.; Itaya, M.; Tsuge, T. Rearrangement of gene order in the phaCAB operon leads to effective production of ultrahigh-molecular-weight poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate] in genetically engineered Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 3177–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochrein, L.; Machens, F.; Gremmels, J.; Schulz, K.; Messerschmidt, K.; Mueller-Roeber, B. AssemblX: A user-friendly toolkit for rapid and reliable multi-gene assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Enghiad, B.; Zhao, H. New tools for reconstruction and heterologous expression of natural product biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; You, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, M.; Rao, Z. Continuous Evolution of Protein through T7 RNA Polymerase-Guided Base Editing in Corynebacterium glutamicum. ACS Synth. Biol. 2025, 14, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Guo, Z.; Xu, M.; Rao, Z.; Zhang, X. Design-build-test of recombinant Bacillus subtilis chassis cell by lifespan engineering for robust bioprocesses. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2024, 9, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Cha, S.; Lee, J.H.; Lim, H.G.; Noh, M.H.; Kang, C.W.; Jung, G.Y. Plug-in repressor library for precise regulation of metabolic flux in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2021, 67, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, M.N.; Alm, E.J.; Arkin, A.P. Interruptions in gene expression drive highly expressed operons to the leading strand of DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 3224–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okochi, M.; Kurimoto, M.; Shimizu, K.; Honda, H. Increase of organic solvent tolerance by overexpression of manXYZ in Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 73, 1394–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Zhou, H.; Sun, H.; He, R.; Song, C.; Cui, T.; Luan, J.; Fu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, N.; et al. Establishing an efficient salinomycin biosynthetic pathway in three heterologous Streptomyces hosts by constructing a 106-kb multioperon artificial gene cluster. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 4668–4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Z.W.; Rao, Z.M.; Cheng, Y.P.; Yang, T.W.; Zhang, X.; Xu, M.J.; Xu, Z.H. Enhanced riboflavin production by recombinant Bacillus subtilis RF1 through the optimization of agitation speed. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 30, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Bhuvaneswari, T.V.; Joseph, C.M.; King, M.D.; Phillips, D.A. Roles for riboflavin in the Sinorhizobium-alfalfa association. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2002, 15, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.N.; Jain, A.; Eulenstein, O.; Friedberg, I. Tracing the ancestry of operons in bacteria. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2998–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kominek, J.; Doering, D.T.; Opulente, D.A.; Shen, X.X.; Zhou, X.; DeVirgilio, J.; Hulfachor, A.B.; Groenewald, M.; McGee, M.A.; Karlen, S.D.; et al. Eukaryotic Acquisition of a Bacterial Operon. Cell 2019, 176, 1356–1366.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, J.; Czarnecka, B.; Harmon, D.E.; Ruiz, C. The multidrug efflux pump regulator AcrR directly represses motility in Escherichia coli. mSphere 2023, 8, e0043023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, H.; Shimokawa, M.; Noguchi, K.; Tago, M.; Matsuda, H.; Takita, A.; Suzue, K.; Tajima, H.; Kawagishi, I.; Tomita, H. The PapB/FocB family protein TosR acts as a positive regulator of flagellar expression and is required for optimal virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1185804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, C.; Tang, W.; Zhang, D. Manipulation of Purine Metabolic Networks for Riboflavin Production in Bacillus subtilis. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 29140–29146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Shi, T.; Chen, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Guo, J.; Fu, J.; Feng, L.; Wang, Z.; et al. Integrated whole-genome and transcriptome sequence analysis reveals the genetic characteristics of a riboflavin-overproducing Bacillus subtilis. Metab. Eng. 2018, 48, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, T.; Ma, X.; Shen, Z.; Zhao, X. Enhancement of riboflavin production with Bacillus subtilis by expression and site-directed mutagenesis of zwf and gnd gene from Corynebacterium glutamicum. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 3934–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.N.; Lee, Y.; Hussein, R. Fundamental relationship between operon organization and gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 10626–10631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.P.; Brahmantio, B.; Bartoszek, K.; Lercher, M.J. Most bacterial gene families are biased toward specific chromosomal positions. Science 2025, 388, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabaria, S.R.; Bae, Y.; Ehmann, M.E.; Beitz, A.M.; Lende-Dorn, B.A.; Peterman, E.L.; Love, K.S.; Ploessl, D.S.; Galloway, K.E. Programmable promoter editing for precise control of transgene expression. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Xu, X.; Huang, H.; Yang, R.; Zhu, X.; Jin, K.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Lv, X.; et al. Construction of a plasmid-free Escherichia coli strain for lacto-N-neotetraose biosynthesis. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanufacturing 2024, 4, 965–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colloms, S.D.; Merrick, C.A.; Olorunniji, F.J.; Stark, W.M.; Smith, M.C.; Osbourn, A.; Keasling, J.D.; Rosser, S.J. Rapid metabolic pathway assembly and modification using serine integrase site-specific recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerenwinkel, N.; Panke, S. Systematic investigation of synthetic operon designs enables prediction and control of expression levels of multiple proteins. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

You, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X.; Du, Y.; Shao, M.; Li, Y.; Rao, Z. A Simple, Rapid Assembly Method for Integrating Different Gene Order into Synthetic Operons. Fermentation 2026, 12, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010011

You J, Zhang H, Wang K, Zhang X, Du Y, Shao M, Li Y, Rao Z. A Simple, Rapid Assembly Method for Integrating Different Gene Order into Synthetic Operons. Fermentation. 2026; 12(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleYou, Jiajia, Hengwei Zhang, Kang Wang, Xiaoling Zhang, Yuxuan Du, Minglong Shao, Yanan Li, and Zhiming Rao. 2026. "A Simple, Rapid Assembly Method for Integrating Different Gene Order into Synthetic Operons" Fermentation 12, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010011

APA StyleYou, J., Zhang, H., Wang, K., Zhang, X., Du, Y., Shao, M., Li, Y., & Rao, Z. (2026). A Simple, Rapid Assembly Method for Integrating Different Gene Order into Synthetic Operons. Fermentation, 12(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010011