Abstract

The suction and discharge reed valves are critical components of reciprocating refrigeration compressors, as their dynamic behavior strongly affects the compressor performance. This study investigates the interaction mechanism between unsteady flow characteristics and valve dynamics in a reciprocating refrigeration compressor. A 3D fluid–structure interaction (FSI) simulation model was developed, and its reliability was validated by comparing the simulated in-cylinder pressure and suction valve lift with the corresponding experimental measurements. The validated model was subsequently utilized to analyze the evolution of unsteady flow characteristics and valve deformations. Furthermore, a series of FSI simulations was performed to examine the influence of suction pressure, rotational speed, clearance volume ratio, suction valve plate thickness, and discharge valve plate thickness on valve dynamics and compressor performance. The results indicated that suction pressure, rotational speed, and clearance volume ratio all exerted a significant influence on the dynamics of both the suction and discharge valves. Variations in suction valve plate thickness exhibited a minor influence on the dynamic behavior and flow resistance of the discharge valve, whereas adjustments to discharge valve plate thickness had almost no impact on those of the suction valve. This weak coupling characteristic provides flexibility for the independent optimization of the suction and discharge reed valves. The findings of this study lay a solid foundation for optimizing valve design and improving compressor performance.

1. Introduction

As a category of general mechanical equipment designed to increase gas pressure, compressors are extensively employed in fields such as vapor-compression refrigeration, industrial production, oil and gas storage and transport, and compressed air energy storage [1,2,3,4]. Reciprocating compressors, a common type of compressor, operate via a piston-cylinder mechanism in which a crankshaft-driven piston cyclically varies the chamber volume to compress the gas. The suction and discharge valves in a reciprocating compressor act as its “lungs”, as their opening and closing regulate the flow of gas entering and exiting the compression chamber. Reed valves are commonly used in low-pressure applications, such as reciprocating refrigerator compressors [5]. The operation of reed valves involves a fluid–structure interaction (FSI) problem. The flexible metal reed bends under the pressure differential of the fluid on its two sides, which in turn changes the boundary of the surrounding fluid. Therefore, studying the FSI characteristics of reed valves is essential to the optimal design of these components.

The theoretical investigation of thermodynamic processes as well as valve dynamics in reciprocating compressors has drawn much attention in the past decades. In 1949, Costagliola [6] proposed a mathematical model for reciprocating compressors that coupled the equation of motion of a 1DOF system with thermodynamic equations, and determined the valve motion and in-cylinder pressure simultaneously by solving the system of differential equations. Prakash and Singh [7] developed a theoretical model for refrigeration compressors that also considered heat transfer in the valve passages and within the cylinder. Rigola Serrano [8] proposed a mathematical model for reciprocating compressors employed in refrigeration systems, where the whole compressor domain was divided into strategically distributed control volumes and the fluid conservation equations in these control volumes were integrated. Wang et al. [9] established a theoretical model in which the flow coefficients at different valve lifts were obtained through numerical simulations, and studied the backflow of refrigerant through the valves in reciprocating compressors. Mu et al. [10] refined the theoretical model of reciprocating compressors by subdividing the valve motion process into two stages.

Significant research efforts have also been devoted to numerically simulating the operational cycle of reciprocating compressors utilizing reed valves. Kim et al. [11] developed a 2D FSI model of the suction valve in a hermetic refrigeration compressor via ADINA (https://www.bentley.com/software/adina/, accessed on 1 December 2025) software, validated the model by comparing simulated valve displacements with experimental data, and conducted shape optimization of the suction valve employing the response surface method. Wang et al. [12] employed ADINA software to construct a 3D FSI model for a hermetic compressor, studied the delayed closing of the suction valve, and analyzed the impacts of pressure ratio, operational speed, and valve thickness on its performance. Rowinski et al. [13] utilized CONVERGE software (https://convergecfd.com/, accessed on 1 December 2025) to establish a 3D FSI model for a small refrigeration compressor. Numerical simulations were performed under two distinct operating conditions and with two different working fluids, and the resulting data for pressure, temperature, valve lift, and mass flow rate exhibited strong consistency with experimental measurements. Bacak et al. [14] built a 3D FSI model employing CONVERGE software and thoroughly studied thermodynamic losses and pressure fluctuations. Gonzalez et al. [15] integrated a large eddy simulation model with a plate model to predict unsteady gas flow-valve dynamic interactions in compressors and analyzed the impacts of straight vs. tapered discharge port geometries using this model. Wu [16] established a 3D FSI model for a refrigerator piston compressor by using ANSYS CFX together with the Transient Structural module in ANSYS Workbench (https://www.ansys.com/products/ansys-workbench, accessed on 1 December 2025), and compared the fluid characteristics and valve dynamics during the start-up process and the stable process.

Some researchers have been devoted to the experimental study of valve dynamics in reciprocating compressors. To determine the displacement of the suction valve in a hermetic refrigeration compressor, Nagata et al. [17] acquired strain signals at the base of the valve plate and computed the corresponding displacement using the established linear correlation between the desired displacement values and the measured strain signals. This approach was adopted by some other researchers to measure valve motions [11,14,18,19]. Real and Pereira [20] and Wang [21] conducted non-contact measurements of valve displacements in refrigerator compressors using two fiber optic sensors installed in the cylinder head. A laser Doppler vibrometer has also been used by researchers to record valve movements in hermetic reciprocating compressors [22,23]. Some researchers have also adopted eddy current displacement sensors to quantify the displacement of reed valves in compressors [10,24,25].

However, the majority of existing studies focus exclusively on one of the two valves—either the suction or discharge valve—rather than investigating both simultaneously. Significant gaps remain in understanding the coordinated operation of the suction and discharge valves, as well as their coupling with the in-cylinder thermal processes and the overall compressor performance. To address these research gaps, this study investigated the interaction mechanism between unsteady flow characteristics and valve dynamics in a reciprocating refrigeration compressor using an FSI simulation model and parameter sensitivity study.

It is noteworthy that reed valves are also widely used in rotary compressors, and their FSI characteristics have been extensively studied [1,26,27,28,29,30]. However, rotary compressors are equipped only with a discharge valve and no suction valve, and their discharge stroke is typically longer than that of reciprocating compressors. Therefore, findings from studies on discharge reed valves in rotary compressors are not fully applicable to the design and optimization of reed valves in reciprocating compressors. This highlights the necessity for dedicated research into the FSI characteristics of reed valves in reciprocating compressors.

In this paper, a 3D two-way FSI simulation model for a hermetic reciprocating compressor was established using ADINA 9.7.2 software, with its reliability validated through experimental tests. The interactions among in-cylinder thermal processes, gas flow passing through the valve ports, and valve plate oscillations were analyzed. Furthermore, the effects of suction pressure, rotational speed, clearance volume ratio, suction valve thickness, and discharge valve thickness on the dynamic characteristics of both the suction and discharge valves, as well as the compressor performance, were investigated via numerical simulations.

2. Numerical Model

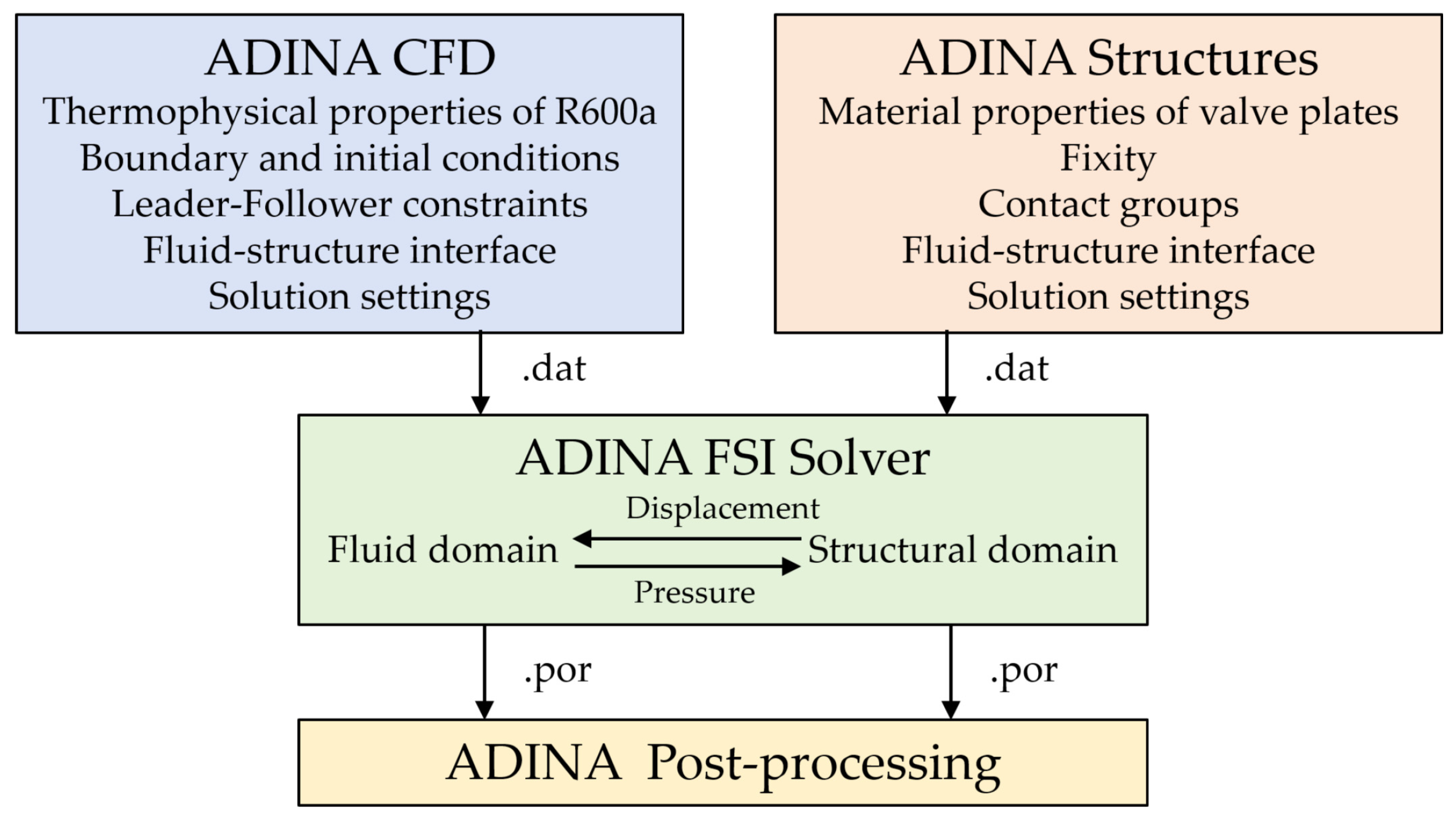

An FSI simulation model was established for a hermetic refrigeration compressor to investigate the interactions among in-cylinder thermal processes, unsteady flow around the reed valves, and valve movements. Mesh discretization of both the fluid and structural domains was accomplished via HyperMesh 2019 software. Subsequently, model setups for the two domains were completed using the ADINA CFD and Structure modules, respectively. Solution files for each domain were generated independently, following which the ADINA FSI solver was invoked to run the two-way FSI simulations.

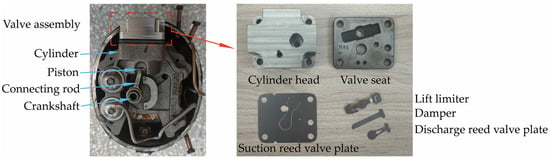

2.1. The Reciprocating Refrigeration Compressor

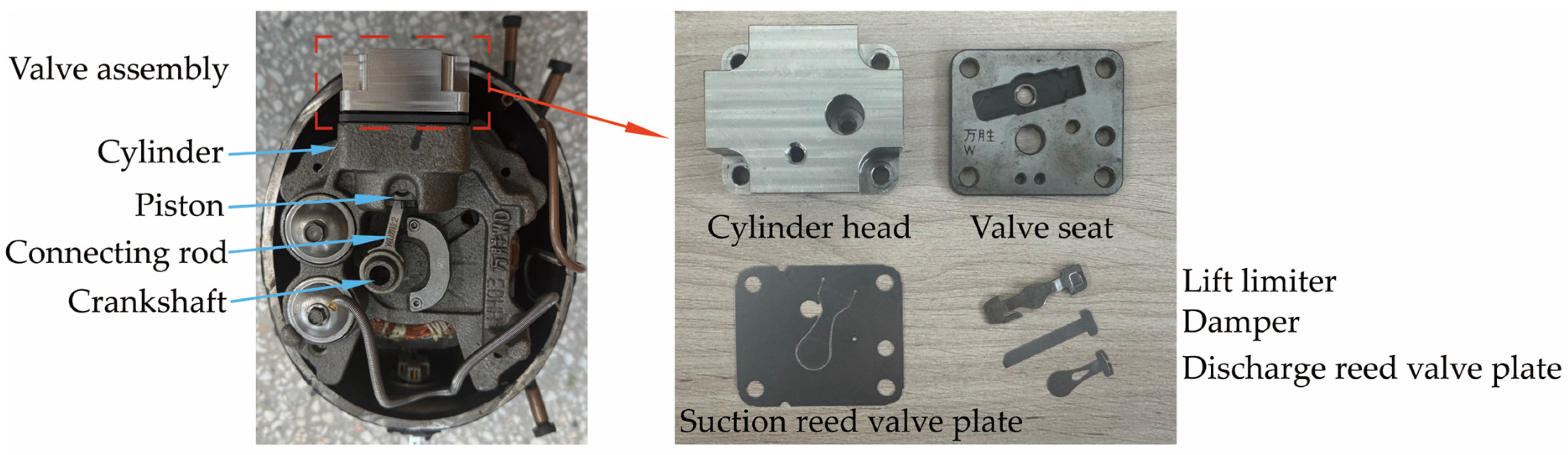

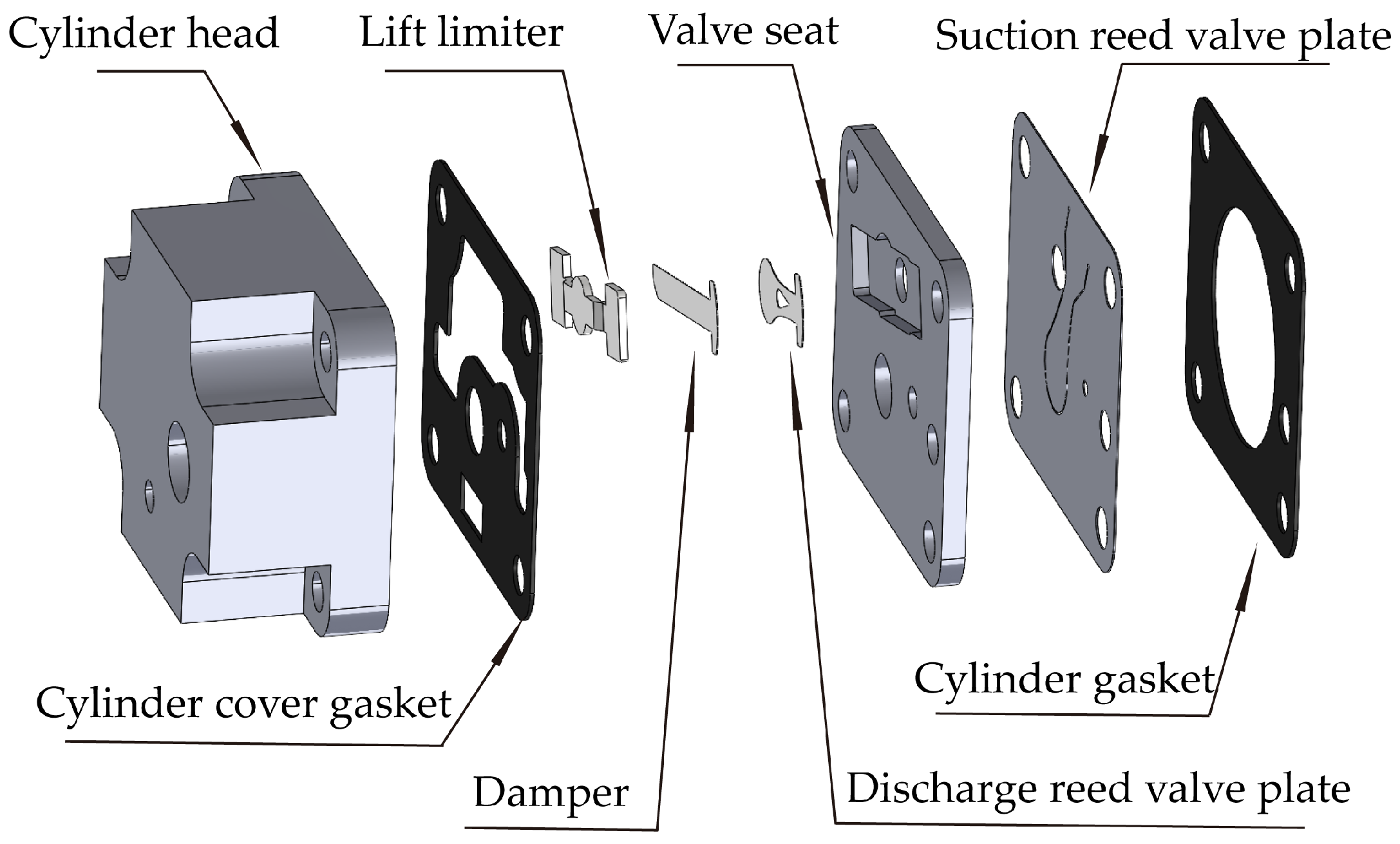

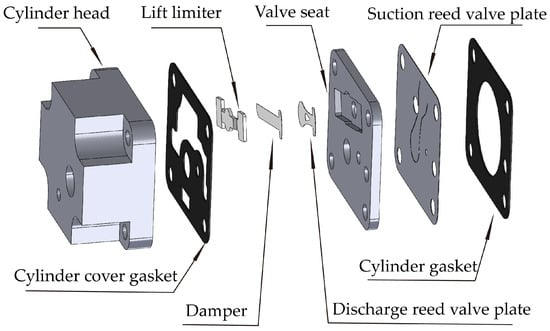

As illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2, the reciprocating refrigeration compressor analyzed in this paper comprises components such as a cylinder, piston, crankshaft, connecting rod, suction reed valve, and discharge reed valve. The cylinder diameter is 28.7 mm, the crank radius is 11.5 mm, the connecting rod length is 39.5 mm, the eccentricity between the cylinder centerline and the crankshaft’s rotation center is 2 mm, and the clearance volume ratio is 2.66%. This compressor uses R600a as the refrigerant and operates at a rated speed of 2950 rpm.

Figure 1.

The reciprocating refrigeration compressor.

Figure 2.

The reed valves in the compressor.

2.2. Governing Equations

In the FSI simulation of the reciprocating compressor, the governing equations for the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy within the fluid domain can be expressed as

respectively, where ρ is the density, t is the time, u is the velocity vector, τ is the stress tensor, f is the body force vector, E is the specific total energy, q is the heat flux vector, and Q is the rate of heat generation.

The dynamic response of the reed valves is governed by the equation of motion:

where M, C, and K are the mass, damping, and stiffness matrices, respectively; , , and are the nodal acceleration, velocity, and displacement vectors, respectively; R is the external load vector; F is the nodal force vector.

At the fluid–structure interfaces, the displacement compatibility condition

and the traction equilibrium condition

were applied, where df and ds are the fluid and solid displacements, respectively; τf and τs are the fluid and solid stresses, respectively; n is the unit boundary normal vector outwards from the computational domain. The underlining denotes that the values are defined on the fluid–structure interfaces only.

2.3. Fluid Domain

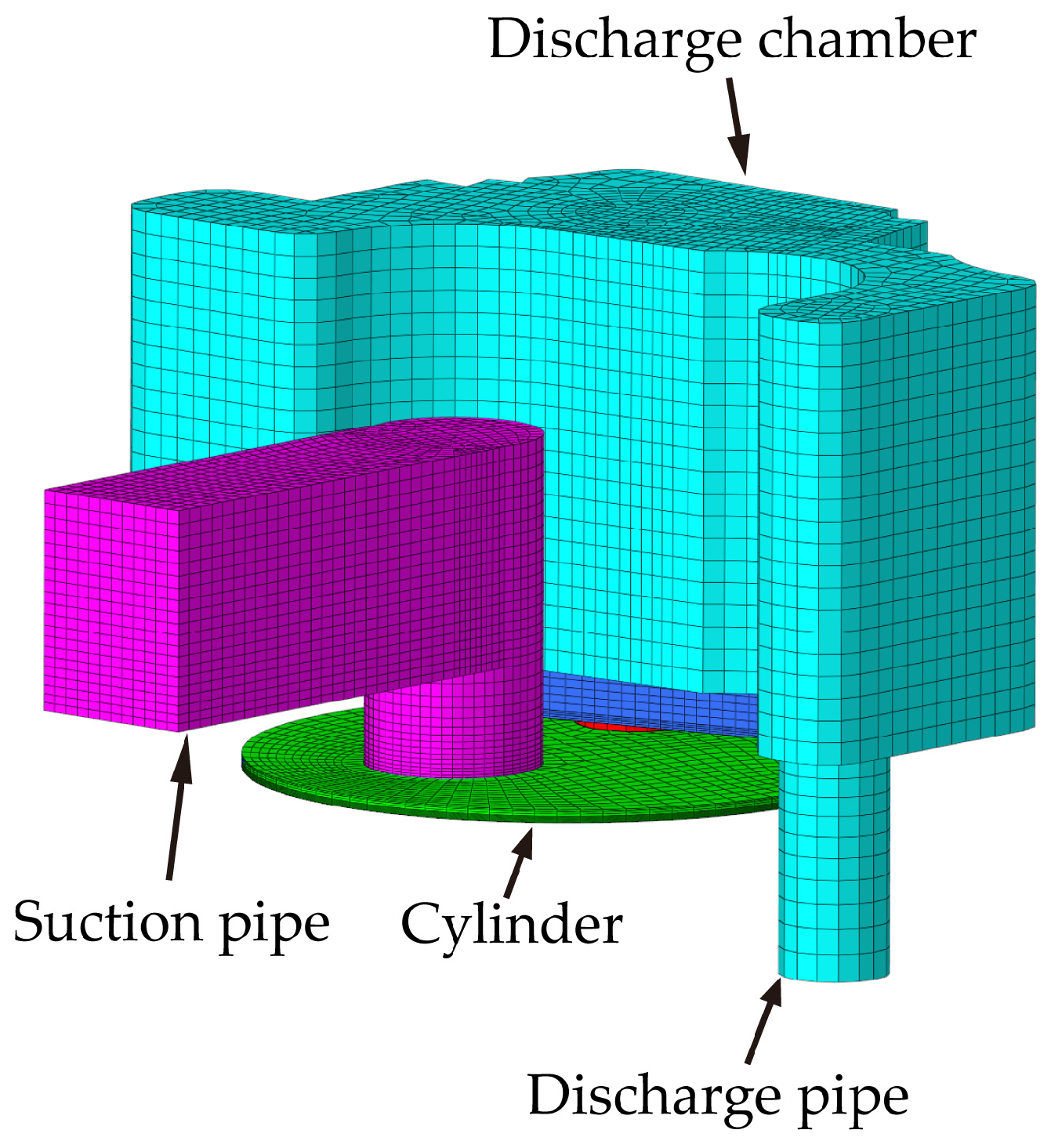

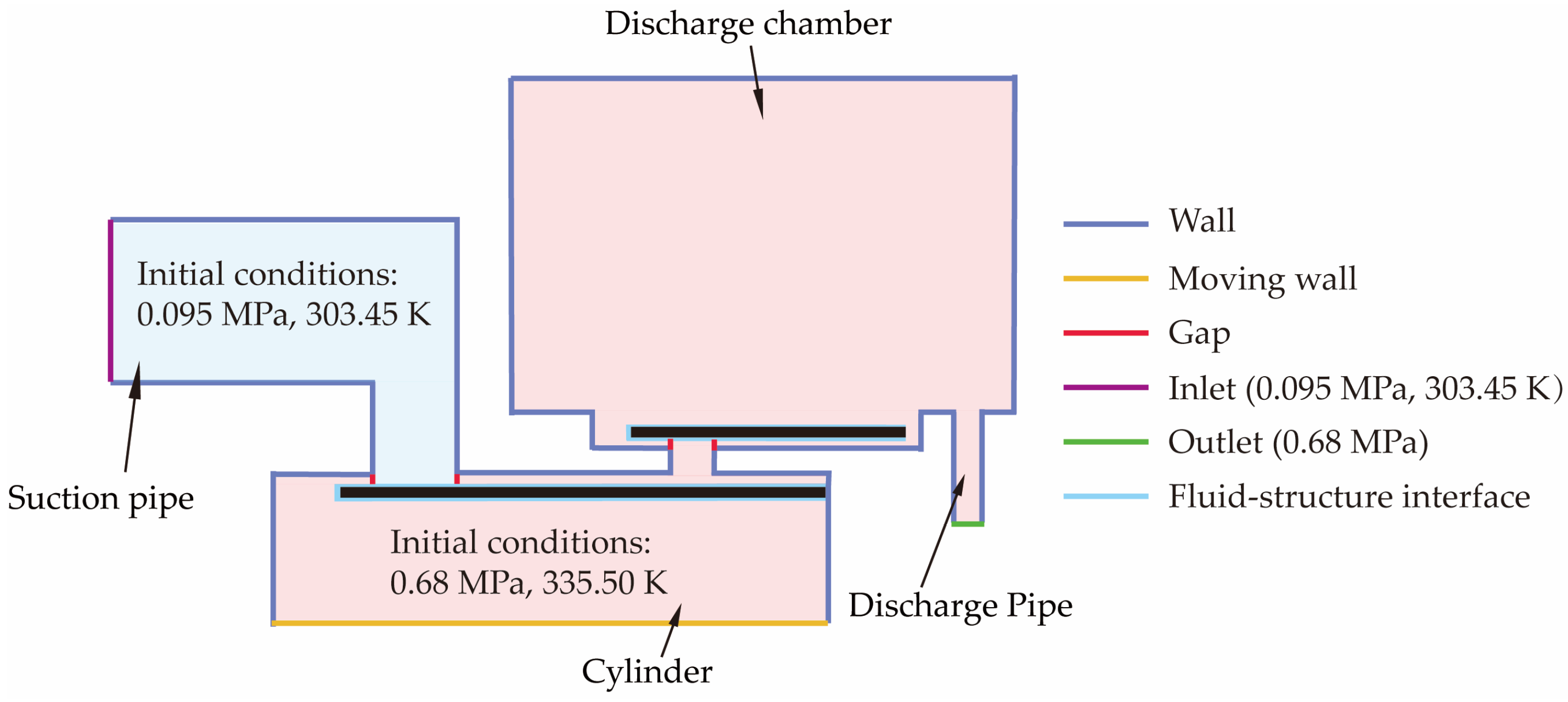

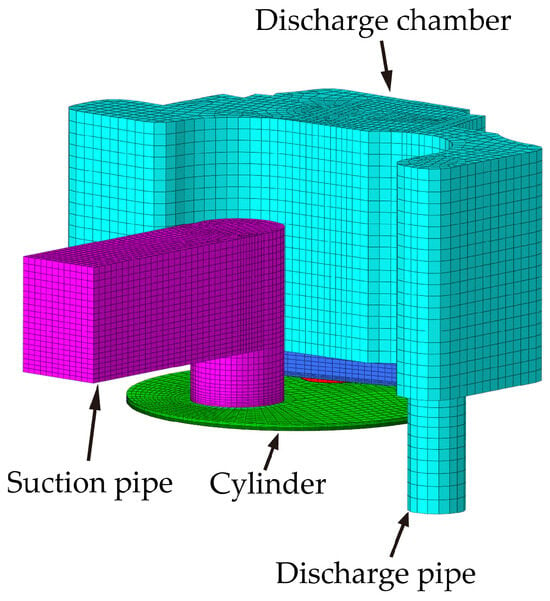

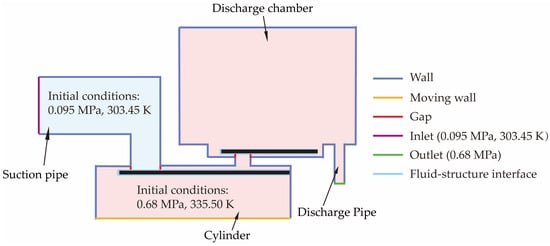

The fluid domain mainly consists of the gases within the cylinder, valve holes, and valve chambers, as shown in Figure 3. The mesh discretization of the fluid domain was accomplished via HyperMesh software and then imported into ADINA software for parameter configuration. Figure 4 is a schematic diagram illustrating the locations of the boundary and initial conditions applied within the fluid domain. Note that the geometry shown in Figure 4 is not drawn to scale, and the spatial angle between the centerlines of the suction and discharge reed valve plates is omitted (see Figure 1 and Figure 2 for the actual arrangement).

Figure 3.

Fluid domain of the reciprocating compressor.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the boundary and initial conditions of the fluid domain.

To ensure the continuity of the fluid mesh across both sides of the valve plate, a thin layer of fluid was added between each of the valve plates and the associated valve seats. The thin layers of fluid would be stretched or flattened as the valve plates deform. Two GAP interfaces were defined to regulate the opening and closing behavior of the reed valves. Specifically, within the thin fluid layer above the suction valve plate, one GAP interface was assigned to the lateral surface of the small cylinder directly beneath the suction valve orifice; correspondingly, in the thin fluid layer below the discharge valve plate, the other GAP interface was designated to the lateral surface of the small cylinder directly above the discharge valve orifice. The GAP interface serves as a connectivity switch: it connects the adjacent fluid subdomains when its area exceeds a preset threshold and isolates them when the area falls below a specified threshold.

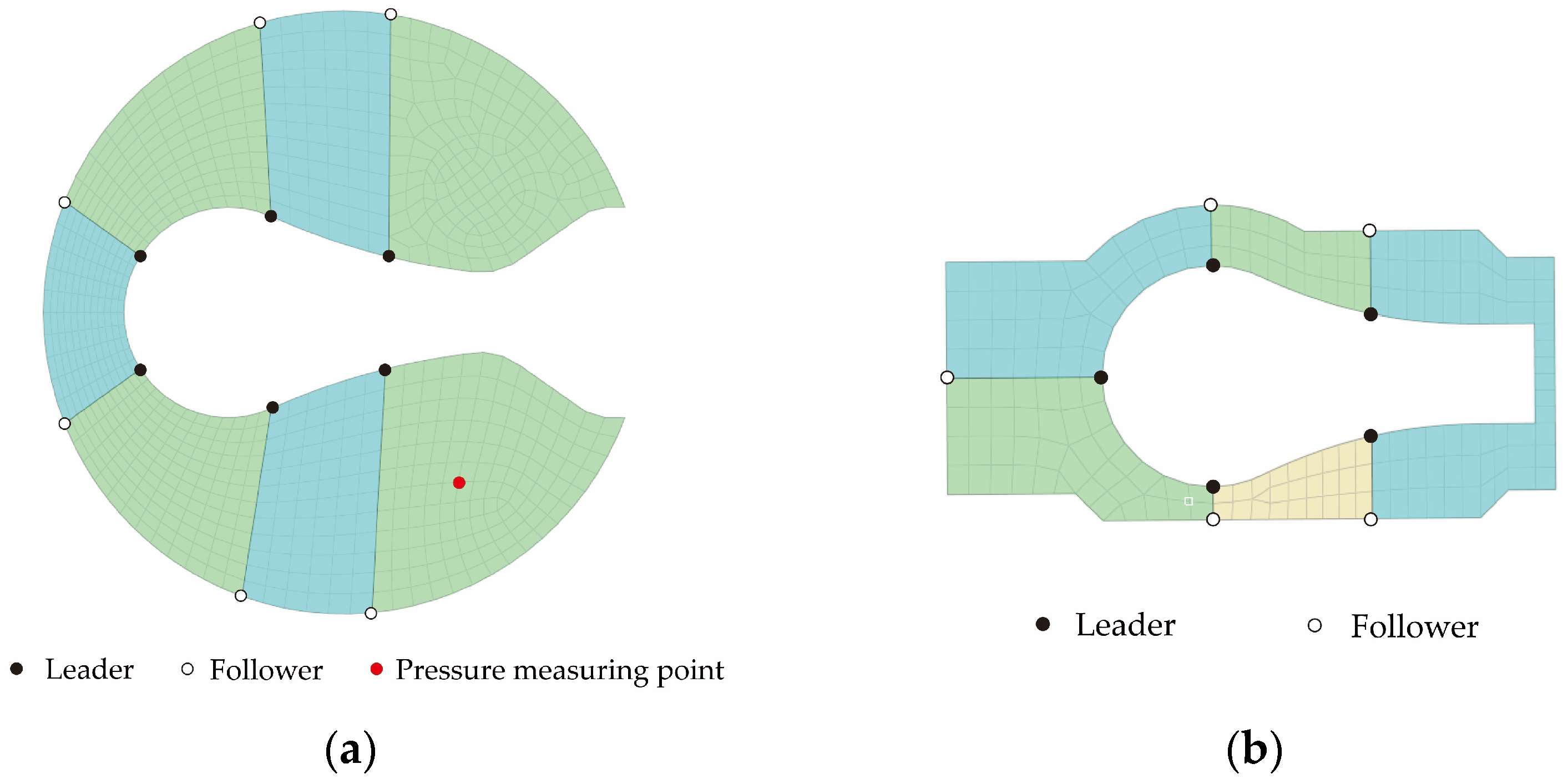

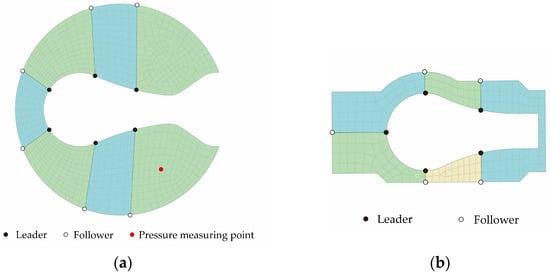

The wall surfaces corresponding to the outer surfaces of the suction and discharge valve plates were defined as the fluid–structure interfaces. Leader–Follower constraints were established to prevent excessive distortion of the fluid mesh near the valve plate when it undergoes large displacements. Specifically, pairs of leader and follower points were defined, with the movement of each follower point governed by its corresponding leader point. The leader points were positioned along the edges of the valve plate, while the follower points were located on the cylinder wall at the same axial height, as illustrated in Figure 5. As the suction or discharge valve plate deforms, the follower points move synchronously along the cylinder wall in accordance with the motion of their respective leader points. This coordinated motion effectively regulates the deformation of the fluid mesh elements surrounding the valve plate, thereby avoiding excessive mesh distortion.

Figure 5.

Arrangement of leader and follower points. (a) suction valve; (b) discharge valve.

The bottom surface of the cylinder was defined as a moving wall, with its displacement along the cylinder centerline, in the direction from the top dead center (TDC) to the bottom dead center (BDC), calculated by the following equation:

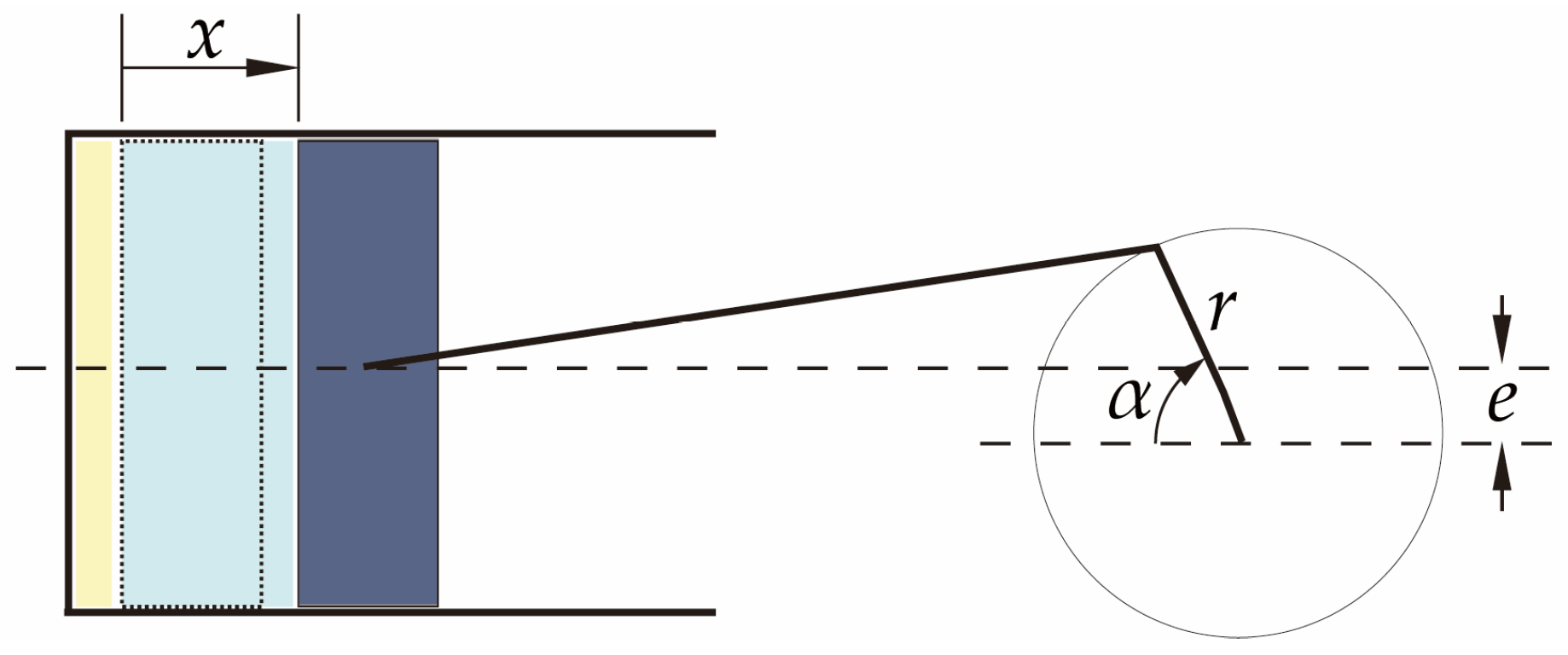

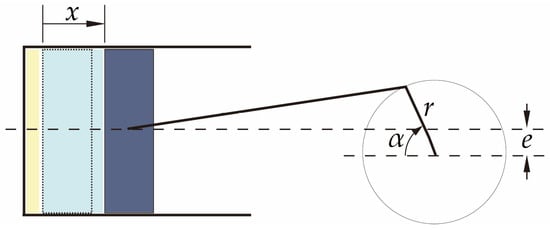

where x is the displacement of the moving wall, r is the crank radius, α is the crank angle, λ is the crank radius-connecting rod length ratio, and e is the eccentricity between the cylinder centerline and the crankshaft’s rotation center, as shown in Figure 6. The crank angle α, which varies from 0° to 360°, is determined by the computational time t and the angular velocity ω of the crankshaft. The angular velocity ω is calculated from the rotational speed N of the compressor.

x = r [(1 − cos α) + λ/4 (1 − cos 2α)] − eλ sin α,

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the motion mechanism of the reciprocating compressor.

The simulation began with the piston positioned at the TDC. At this point, the gas in the clearance volume and discharge chamber was at high temperature and pressure, while the gas in the suction pipeline was at low temperature and pressure. Initial pressure and temperature values were specified for each region. The nominal suction pressure and nominal discharge pressure were imposed on the end faces of the suction and discharge pipelines, respectively. The k-ε turbulence model was adopted to predict the flow characteristics within the fluid domain. The refrigerant used was R600a, with its thermophysical properties obtained from NIST REFPROP 8.0 software. These properties, which vary as functions of temperature and pressure, were extracted in tabulated form. The resulting data table, covering the relevant operational range, was then integrated into ADINA as a set of variable-dependent material property curves. During the simulation, ADINA interpolated these curves to update the fluid properties in each computational cell based on the local temperature and pressure.

2.4. Structural Domain

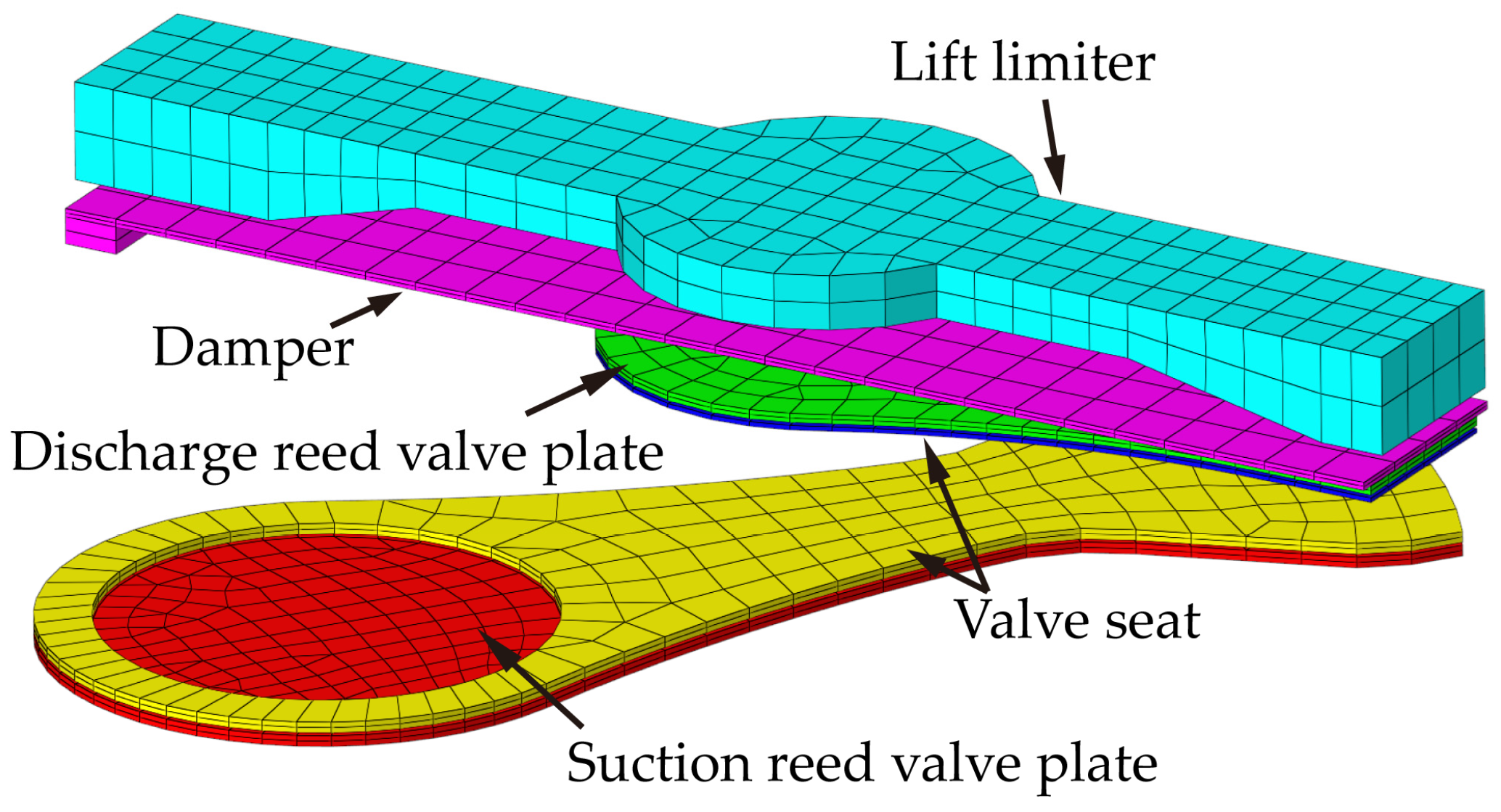

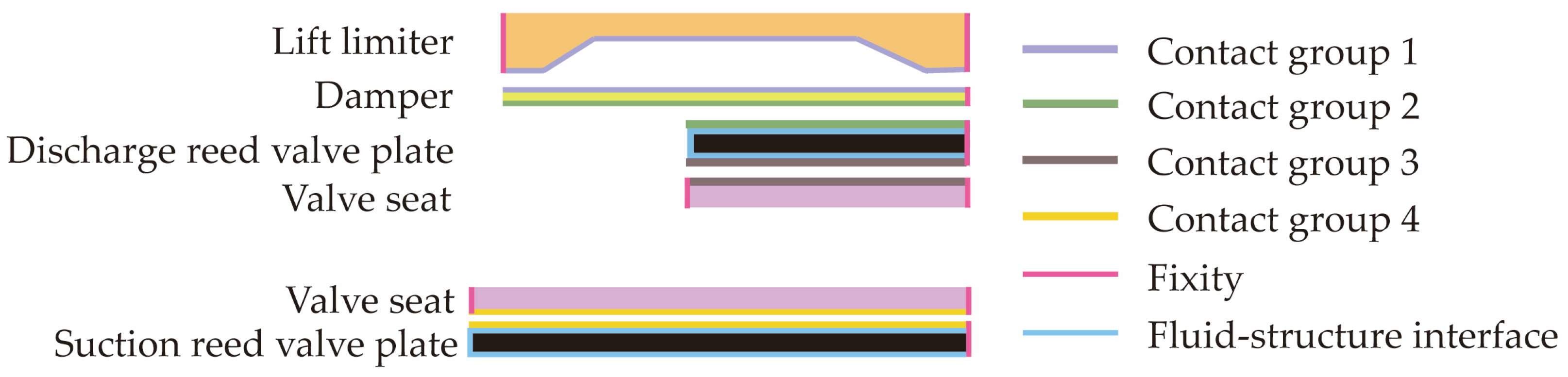

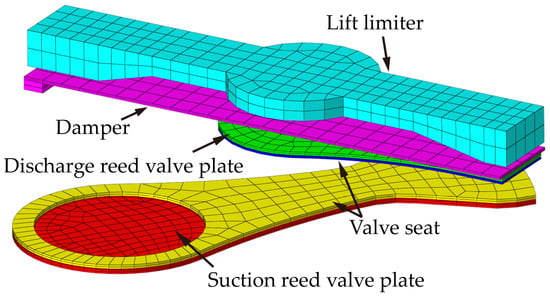

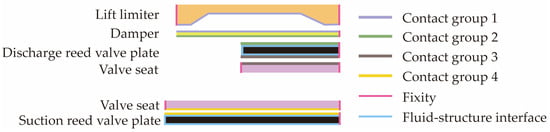

Figure 7 illustrates the structured mesh discretization of the suction valve plate, discharge valve plate, their respective valve seats, the lift limiter of the discharge valve, and the buffer sheet positioned between the discharge valve plate and its lift limiter. The thicknesses of the suction valve plate and discharge valve plate are 0.2 mm and 0.17 mm, respectively. The valve plates are made of Sandvik valve plate steel, which has an elastic modulus of 2.07 × 1011 Pa, a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3, a density of 7920 kg/m3, and a yield strength of 850 MPa.

Figure 7.

Structural domain of the reciprocating compressor.

Figure 8 shows a schematic (not to scale) of the boundary conditions applied within the structural domain. It does not depict the spatial angle between the centerlines of the suction and discharge reed valve plates (see Figure 1 and Figure 2 for the actual arrangement). Fixed constraints were applied to the roots of the valve plates, and the remaining surfaces of the valve plates were set as fluid–structure interfaces. The outer surfaces of the valve seats were also fixed. Frictional contact pairs were established between the contact surfaces of adjacent components, with a friction coefficient of 0.2. Large deformation effects were enabled.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the boundary conditions of the structural domain.

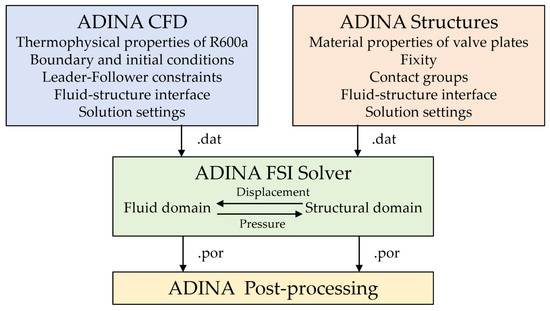

2.5. FSI Simulation

After completing the model setup in the ADINA CFD and ADINA Structures modules, the solution files for each domain were exported separately. In the ADINA FSI solver, both solution files were selected simultaneously, and the transient two-way FSI simulation was initiated. During the two-way FSI simulation, the gas force loads calculated in the fluid domain were transferred to the structural domain, while the displacements of the valve plates were transferred from the structural domain back to the fluid domain. The workflow of the two-way FSI simulation is illustrated in Figure 9. The primary solution settings used in the ADINA software are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 9.

Schematic workflow of the two-way FSI simulation.

Table 1.

Solution settings for the ADINA-based FSI simulation.

Upon completing the coupling computation, result files for both the fluid and structural domains were generated and analyzed using the ADINA Post-processing module. The instantaneous pressure within the cylinder was extracted and exported in a tabular format. Note that in this study, the in-cylinder pressure extraction point (see Figure 5) is located directly beneath the mounting position of the pressure sensor used in the experimental tests.

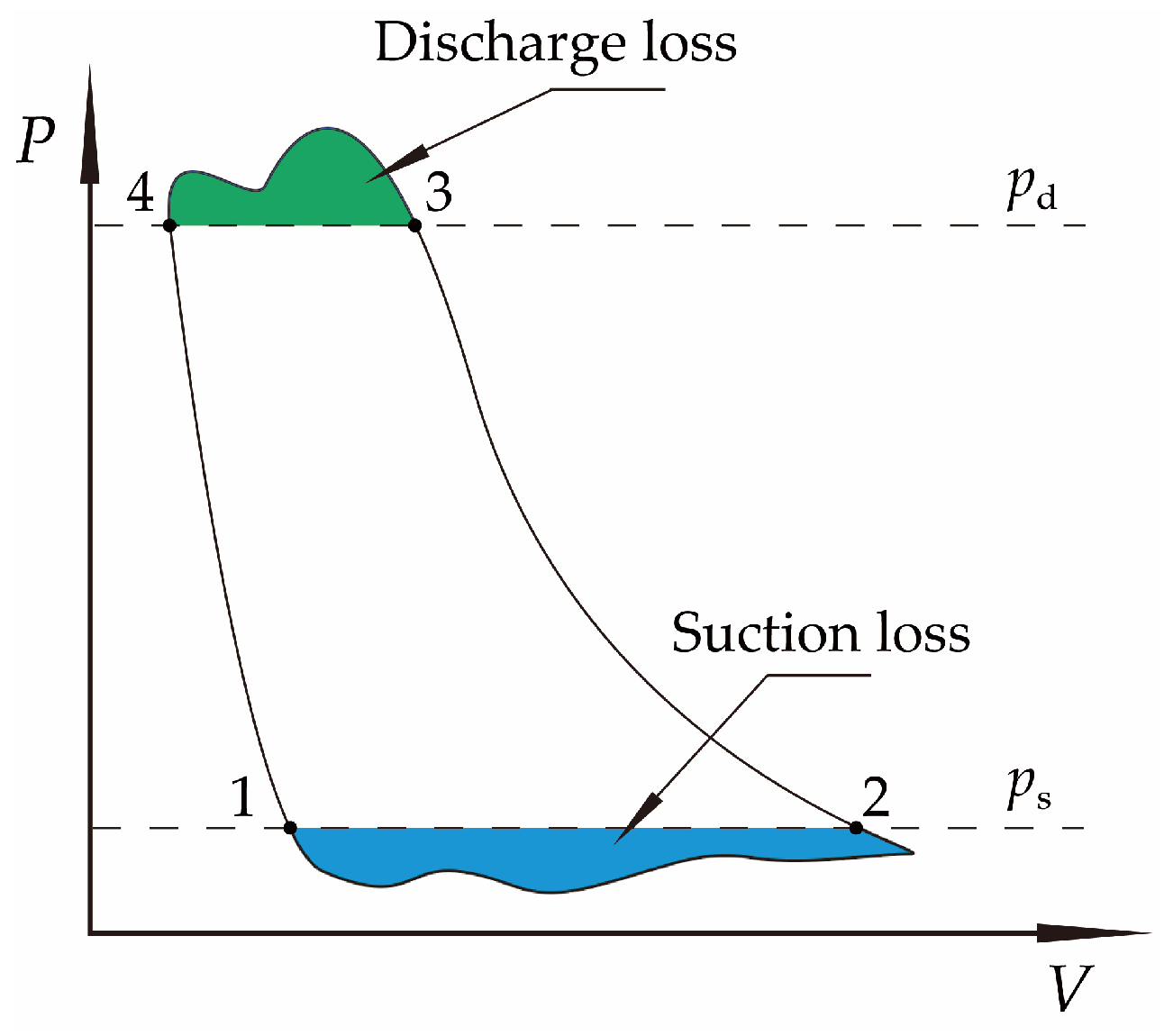

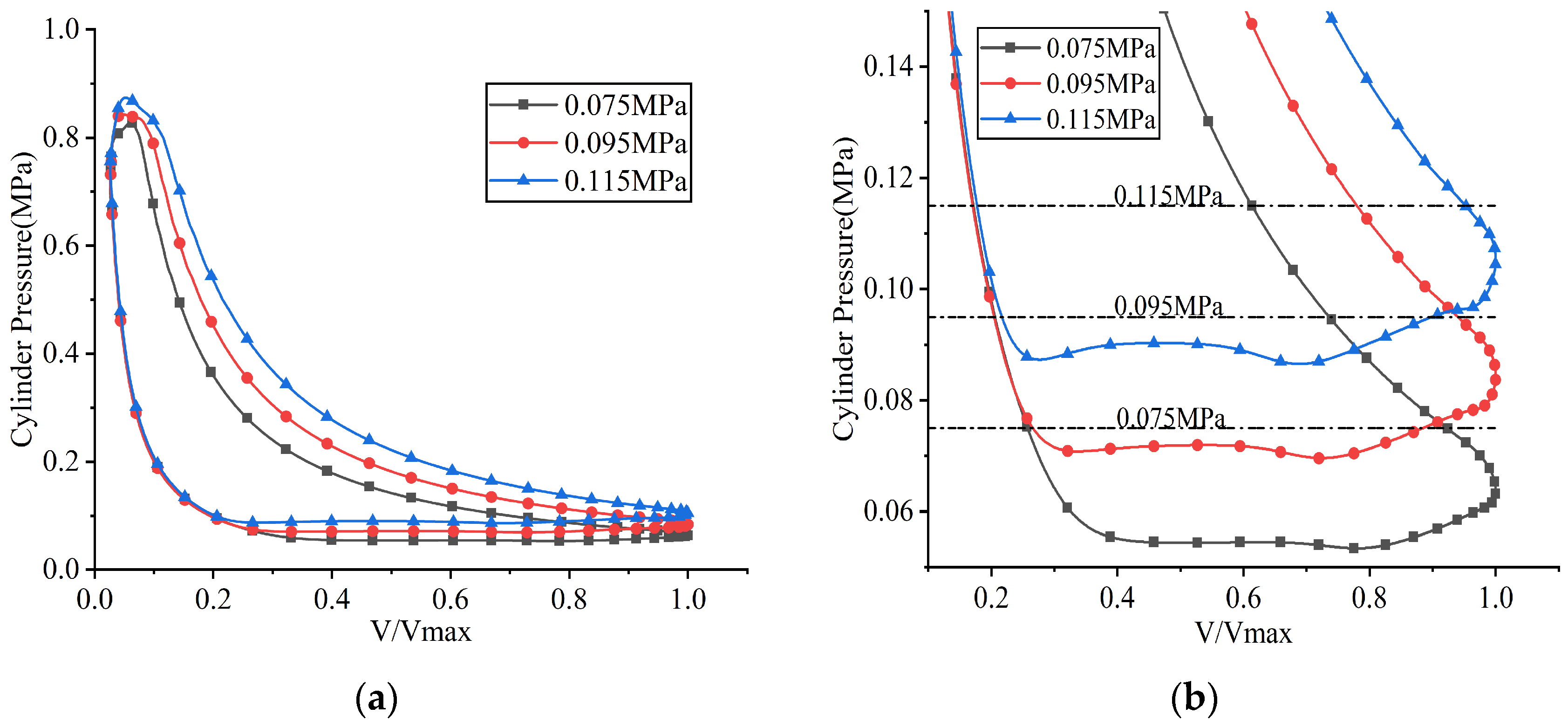

The indicated work per cycle, Wi, is obtained by integrating the pressure-volume (p–V) diagram of the compression chamber over a single operating cycle:

where p is the instantaneous pressure within the compression chamber, and V is the corresponding chamber volume.

The indicated power Pi is then calculated from the indicated work per cycle and the rotational speed of the compressor:

where N denotes the compressor rotational speed in revolutions per minute (rpm).

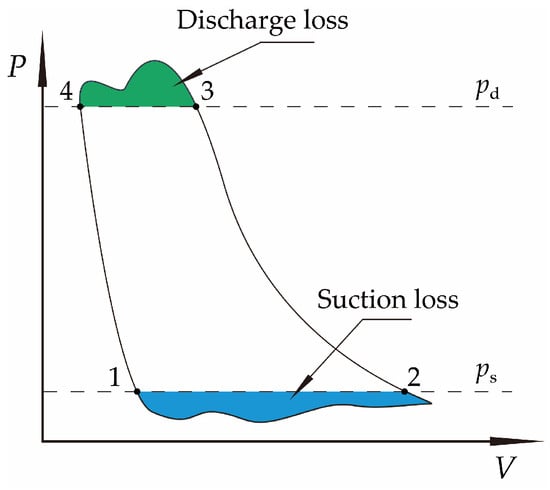

In a single operating cycle, the indicated work losses associated with the suction and discharge processes, denoted as Ws,loss and Wd,loss, respectively, are quantified by the areas enclosed between the instantaneous pressure curve and the nominal suction or discharge pressure lines in the p-V diagram (see Figure 10). Their calculation formulas are given by

and

where ps and pd are the nominal suction and discharge pressures, respectively.

Figure 10.

Schematic representation of the p-V diagram.

The corresponding indicated power losses are obtained by:

and

To evaluate computational convergence, four compressor operating cycles were simulated, and the simulation results of each cycle were compared. At 2950 rpm, the compressor operates with a piston motion cycle of 20.3 ms. A time step of 0.01 ms was employed, in conjunction with the computational meshes depicted in Figure 3 (62,968 elements) and Figure 7 (1928 elements). The simulations yielded indicated powers of 127.2986 W, 126.3498 W, 126.4070 W, and 126.4536 W for the four cycles, accompanied by refrigerant mass flow rates through the suction valve of 4.3904 kg/h, 4.3570 kg/h, 4.3601 kg/h, and 4.3621 kg/h, respectively. The simulation results of the third and fourth cycles showed good consistency. Therefore, the results from the third cycle were used in all subsequent analyses.

Table 2 presents the results of the mesh and time step independence study. The deviations in indicated power and mass flow rate through the suction valve were below 1% when comparing simulation results obtained with the medium mesh scheme (62,968 fluid elements and 1928 structural elements) against those from the fine reference mesh (132,451 fluid elements and 5456 structural elements). Similarly, deviations in the same performance parameters were under 1% when shortening the time step from 0.01 ms to 0.005 ms. Based on these results, the medium mesh scheme (62,968 fluid elements and 1928 structural elements) combined with a time step of 0.01 ms was adopted for all subsequent numerical analyses.

Table 2.

Mesh and time step independence verification for the FSI simulation model.

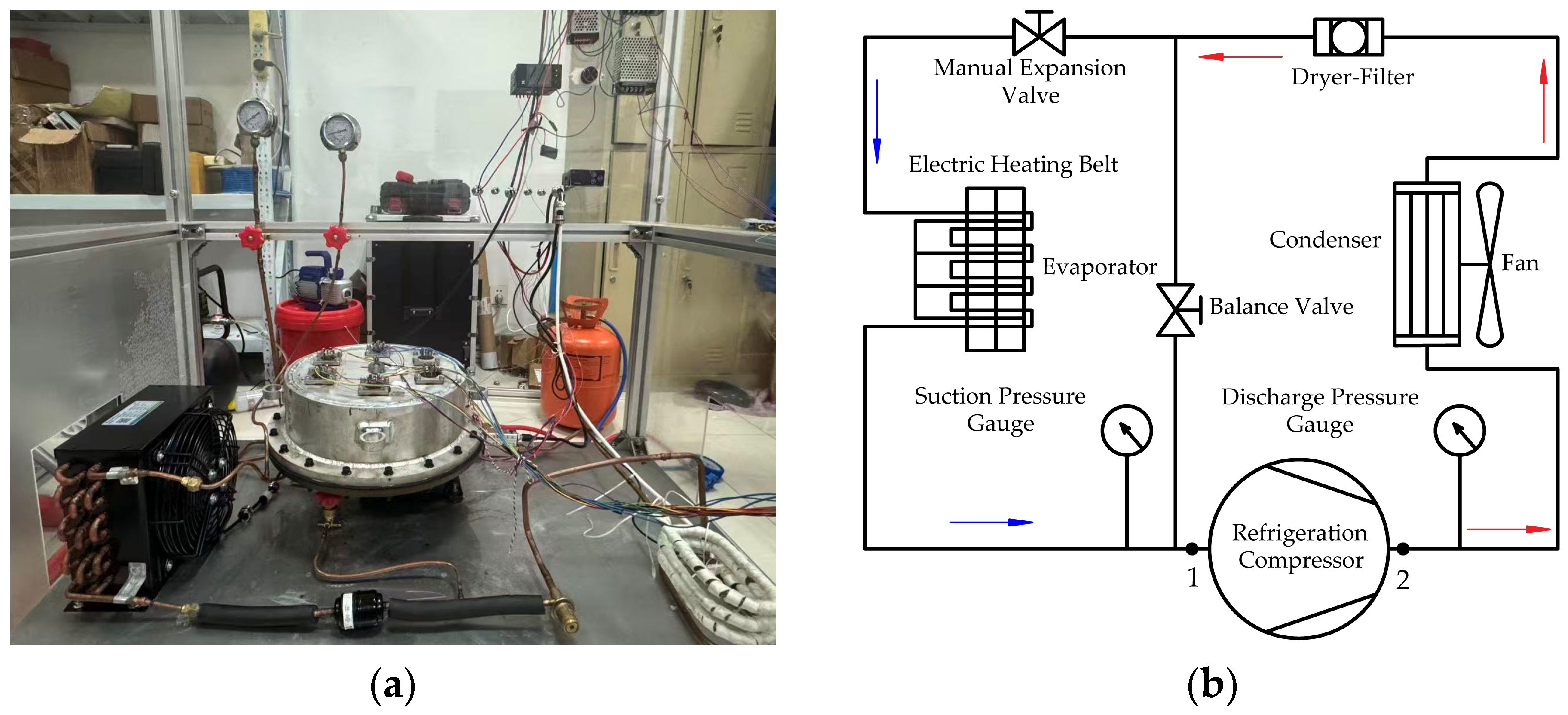

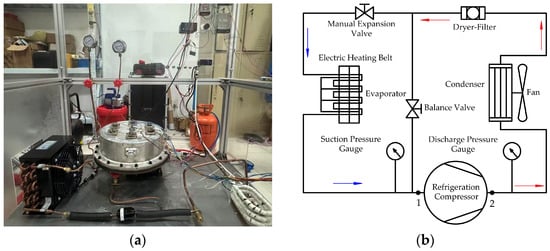

3. Experimental System

An experimental system was constructed to verify the reliability of the simulation results (see Figure 11). The reciprocating compressor under test, along with the condenser, expansion valve, and evaporator, forms a refrigeration system circulating R600a refrigerant. During operation, the gas exiting the evaporator at low pressure and low temperature is drawn into the compressor, where it is pressurized and subsequently discharged as high-pressure gas into the condenser. The operating conditions of the compressor can be adjusted by regulating the speed of the condenser fan, adjusting the expansion valve opening, and controlling the power of the evaporator heating belt. Pressure gauges and thermocouples were installed on the compressor’s suction and discharge pipelines. Specifically, the thermocouples were located at positions 1 and 2, as shown in Figure 11b.

Figure 11.

Experimental system. (a) laboratory setup; (b) schematic diagram.

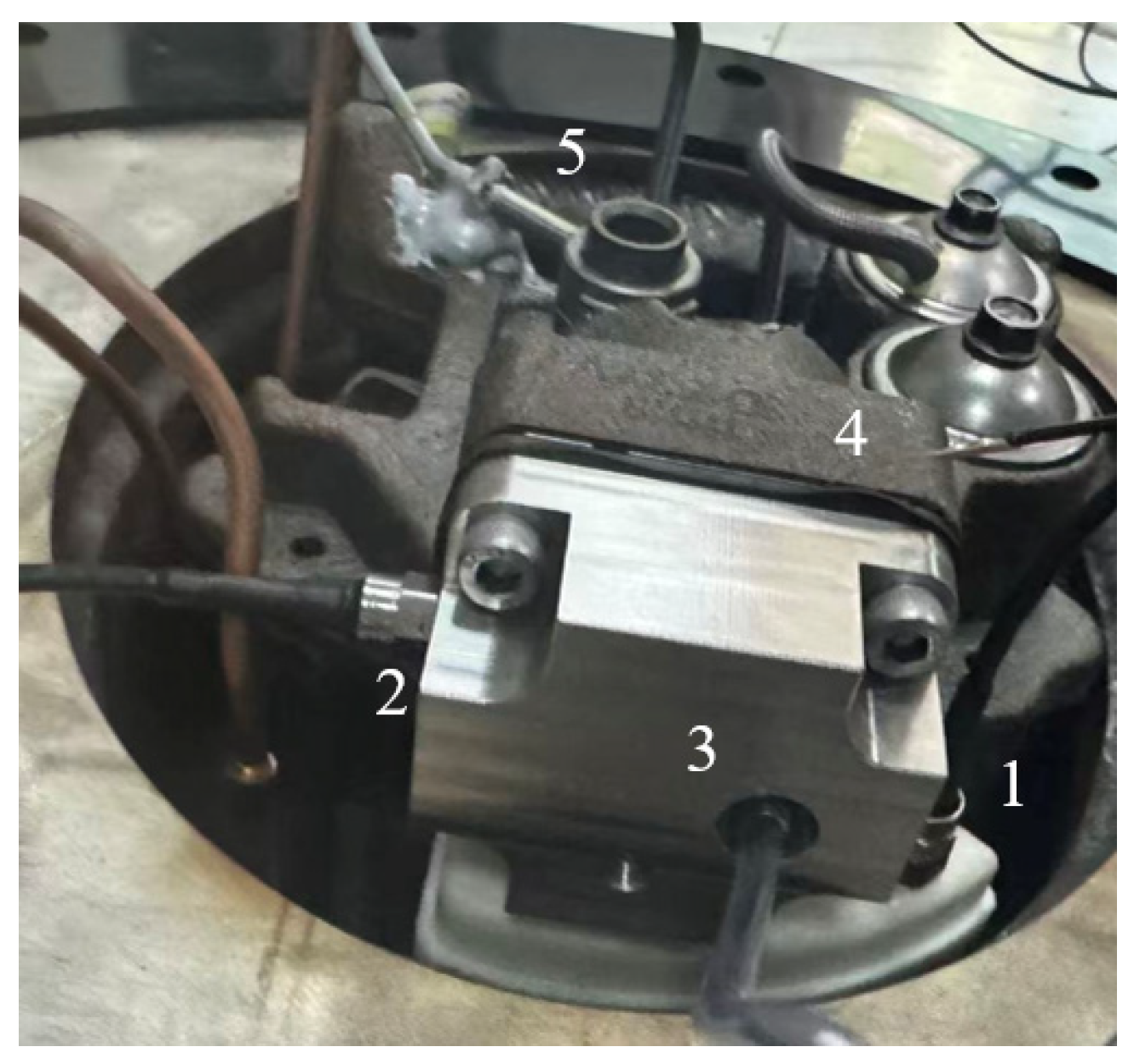

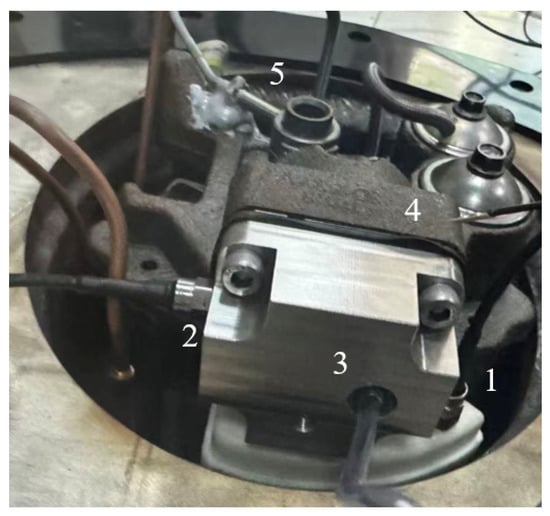

As shown in Figure 12, three pressure measurement ports were positioned on the cylinder head and suction muffler at locations (1), (2), and (3). Kulite miniature pressure transducers were installed at these points to simultaneously measure pressure fluctuations in the suction pipe, discharge chamber, and cylinder during compressor operation. To record the lift curve of the suction valve plate, a strain gauge was affixed at position (4). Additionally, an OMRON proximity switch was mounted at position (5) on the cylinder base. When the crankshaft passed this point, the switch generated a trigger signal that served as the reference for the crank angle.

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of sensor placement in the compressor test system.

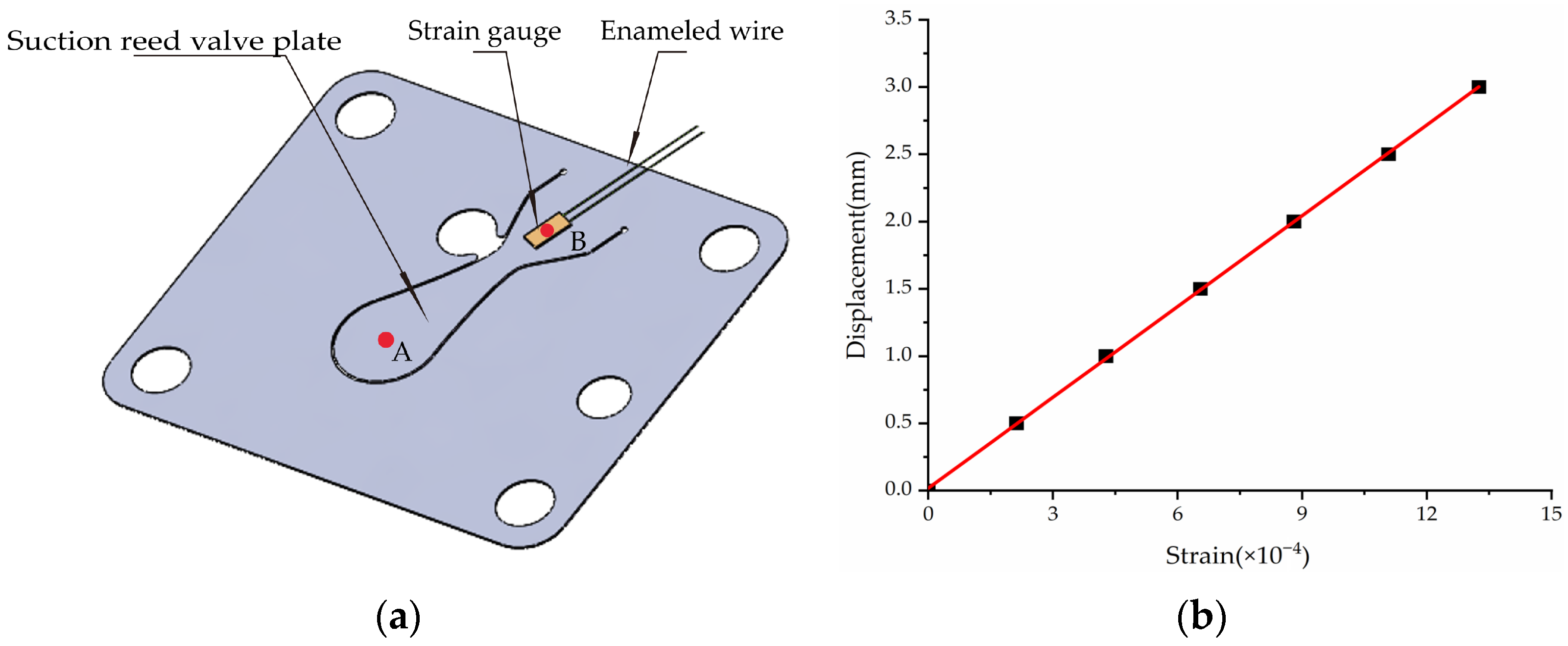

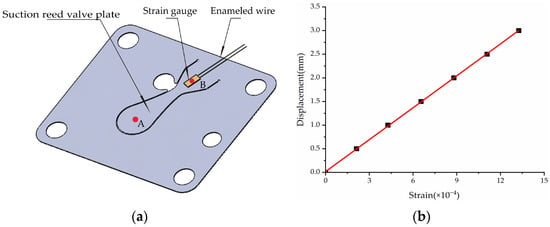

The installation position of the strain gauge on the suction valve plate is shown in Figure 13a. To establish the relationship between the required valve lift (displacement of point A shown in Figure 13a) and the experimentally measured strain signals, the calibration device described in reference [14] was utilized. Specifically, the suction valve plate was taken out of the compressor, the deformation at point A (see Figure 13a) was measured using a micrometer, and the strain at point B (see Figure 13a) under different valve lifts was recorded with a strain gauge. The relationship between the deformation at the center of the valve plate head (point A shown in Figure 13a) and the measured strain signals was obtained, and the results indicated that the displacement at point A increased linearly with the strain at point B, as shown in Figure 13b.

Figure 13.

Measurement of suction valve displacement. (a) Strain gauge arrangement schematic; (b) Relationship between the measured strain at point B and the required displacement at point A.

During the experiments, the voltage outputs from the pressure transducers and the strain measurements obtained from the strain gauge were first amplified and conditioned via a data acquisition system, then converted into digital signals for real-time visualization and storage on a computer. Signal acquisition was performed using three National Instruments (NI) modules: the NI 9237, NI 9205, and NI cDAQ-9189. Specifically, the strain at point B (see Figure 13a) was collected through the NI 9237 module, while the voltage signals from the pressure transducers and the pulse signal from the proximity switch were acquired via the NI 9205 module. Responses from all five sensors were recorded simultaneously during the operation of the compressor. All signals were transmitted to the computer through the NI cDAQ-9189 chassis, and the real-time display and data storage were implemented using LabVIEW 2020 software.

Based on uncertainty propagation theory, the combined uncertainty of a calculated quantity is given by

where σy represents the uncertainty of the calculated quantity, and xi denotes the independent directly measured variables. The uncertainties of the instantaneous pressure inside the compression chamber, reed valve displacement, and indicated power are 0.5%, 1.0%, and 2.23%, respectively.

4. Results

4.1. Validation of the Numerical Model

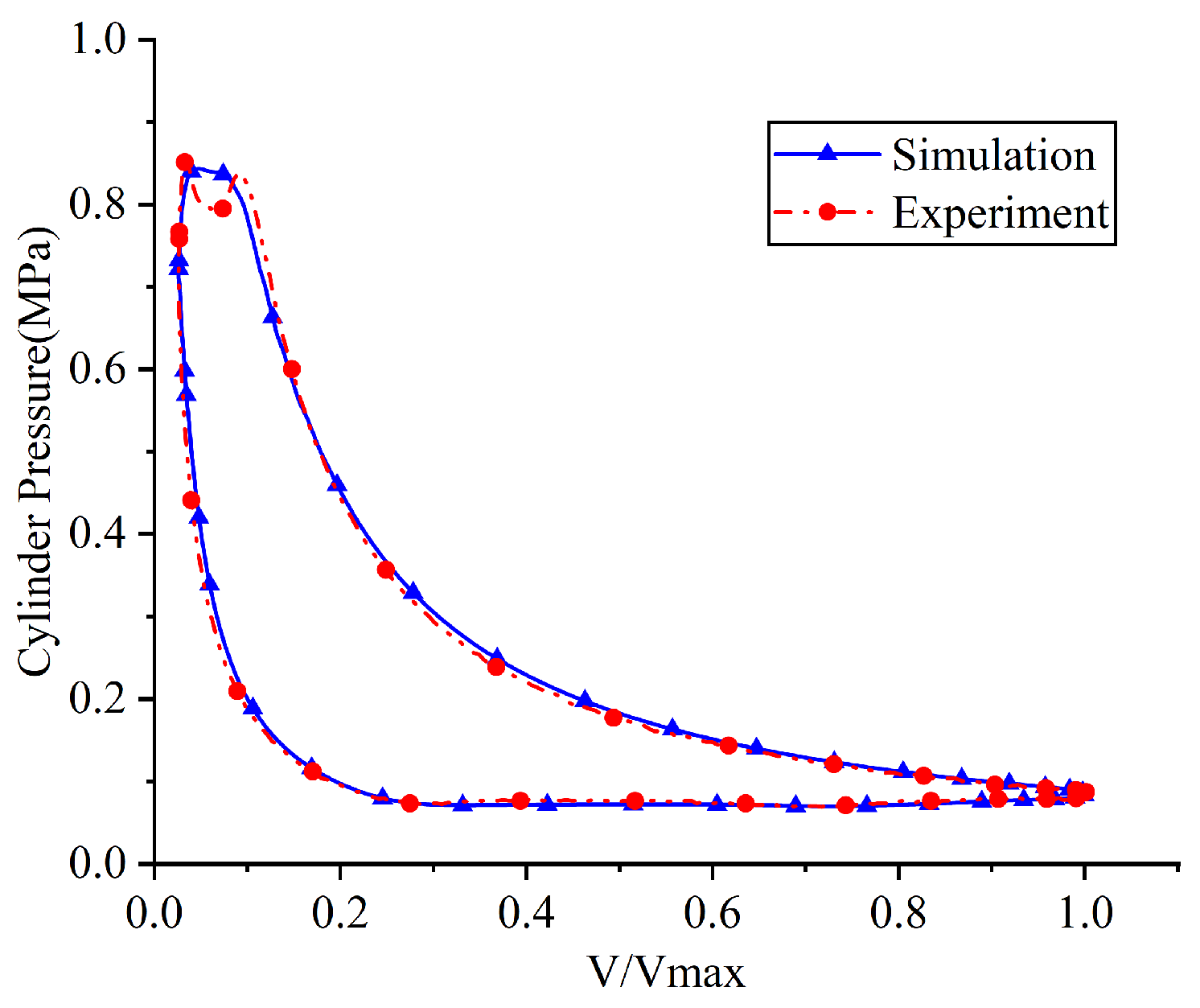

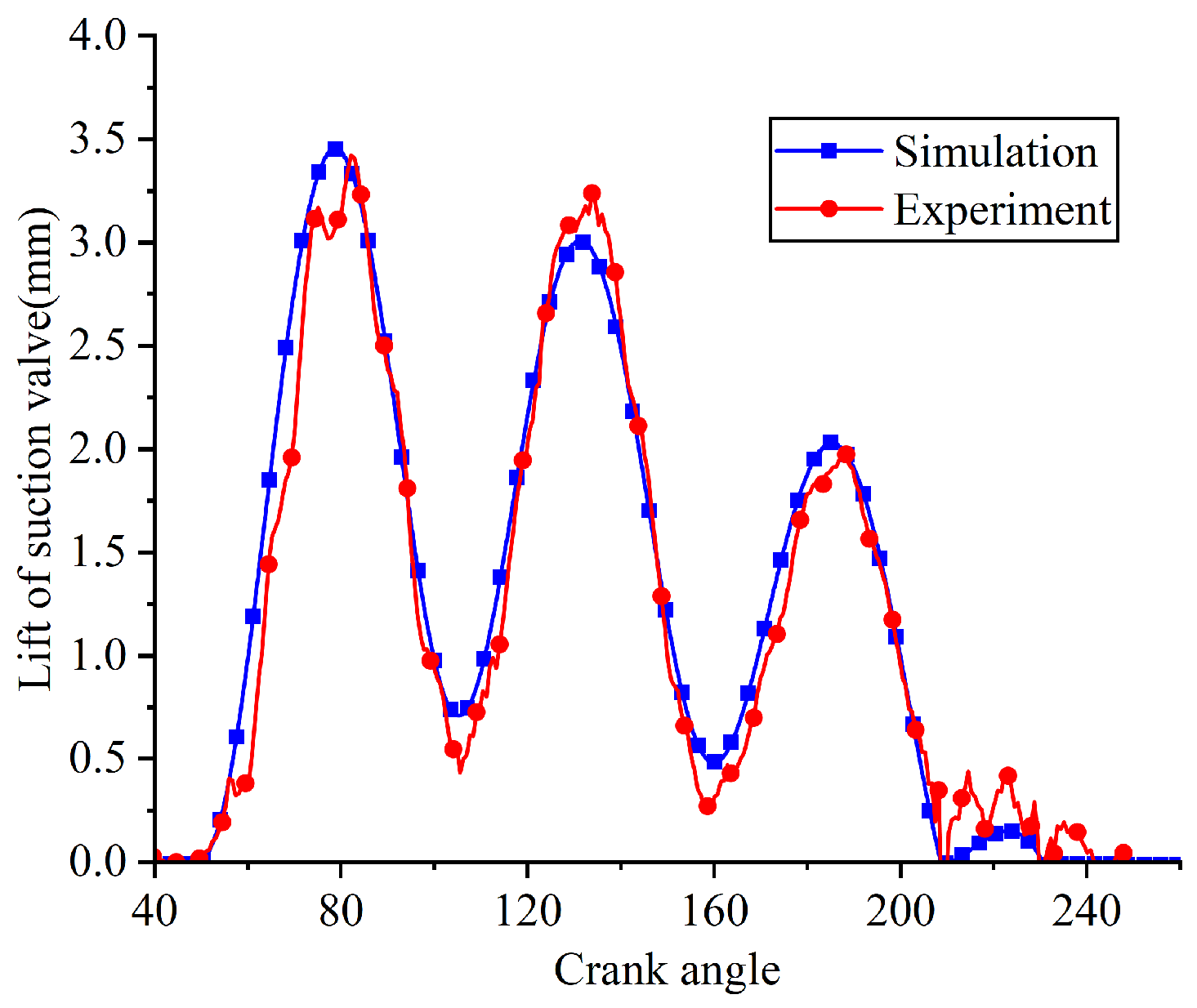

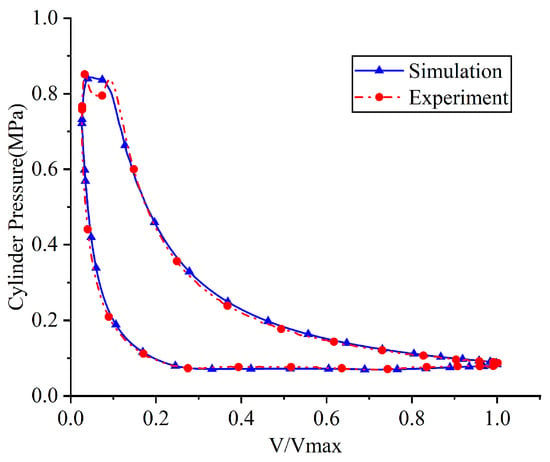

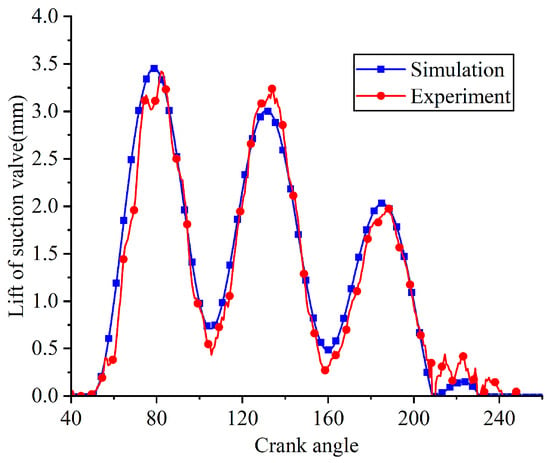

Figure 14 and Figure 15 compare the in-cylinder pressure and suction valve lift (i.e., the displacement of point A in Figure 13a) from numerical simulations and experimental measurements under the following operating conditions: a suction pressure of 0.095 MPa, a suction temperature of 30.3 °C, and a discharge pressure of 0.68 MPa.

Figure 14.

Comparison of the simulated and measured p-V diagrams of the compressor.

Figure 15.

Comparison of the simulated and measured lift curves of the suction valve.

The simulated indicated power of 126.407 W showed good agreement with the experimental value of 121.83 W, resulting in a relative error of 3.76%. The indicated power was calculated by integrating the p-V indicator diagram (Figure 14), which charts the chamber pressure against its instantaneous volume throughout the cycle and also allows for quantification of energy losses attributable to the gas valves. As illustrated in Figure 15, the experimental and simulated lift curves of the suction reed valve showed strong consistency, both exhibiting four oscillations. The key parameters compared are as follows: opening angles (experiment: 49.56°, simulation: 49.596°, relative error: 0.07%), closing angles (experiment: 242.136°, simulation: 230.49°, relative error: 4.81%), and maximum lift (experiment: 3.42 mm, simulation: 3.453 mm, relative error: 0.96%). The good agreement between the simulation and experimental data demonstrates the validity of the FSI model.

4.2. FSI Characteristics of the Suction Reed Valve

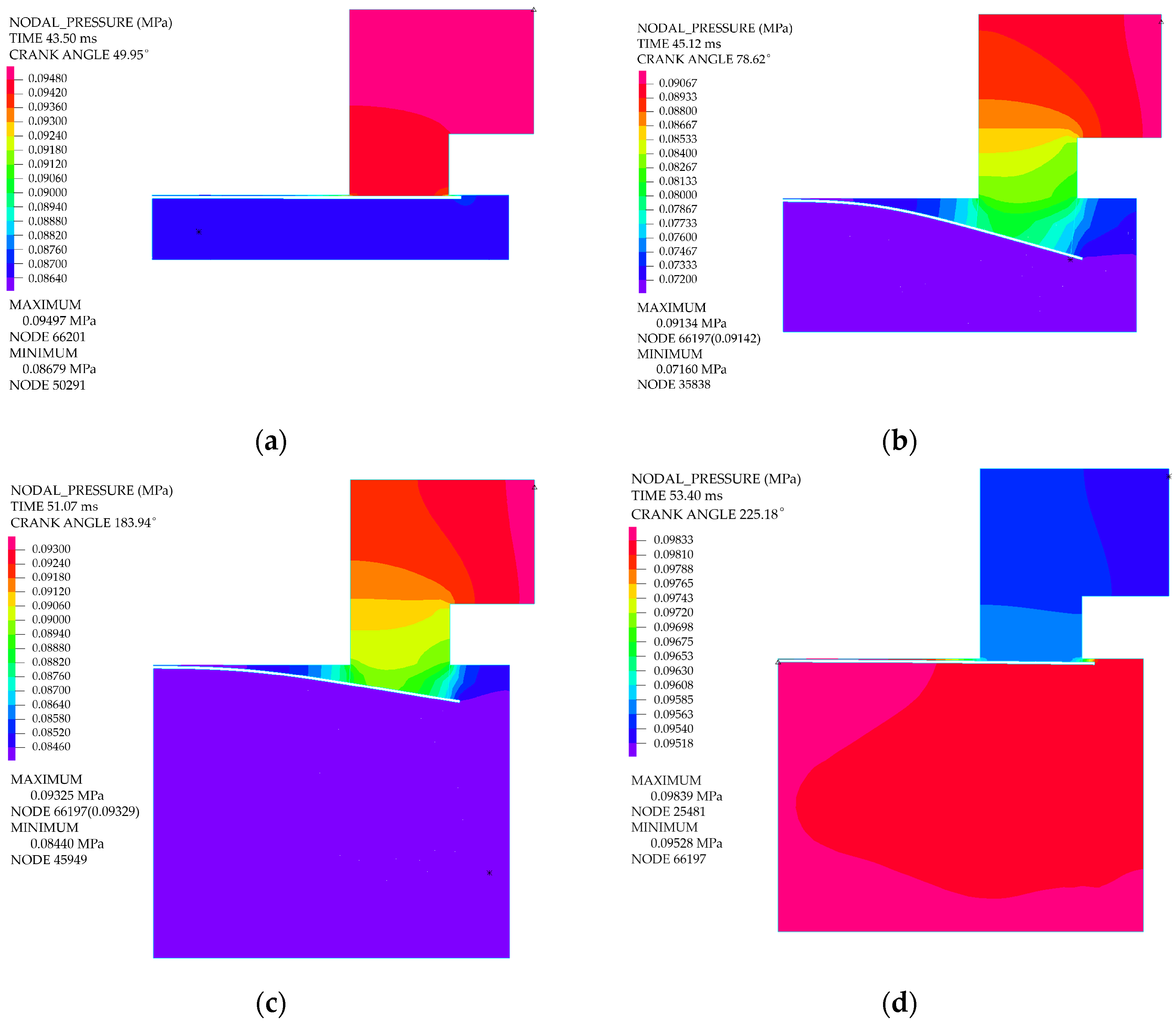

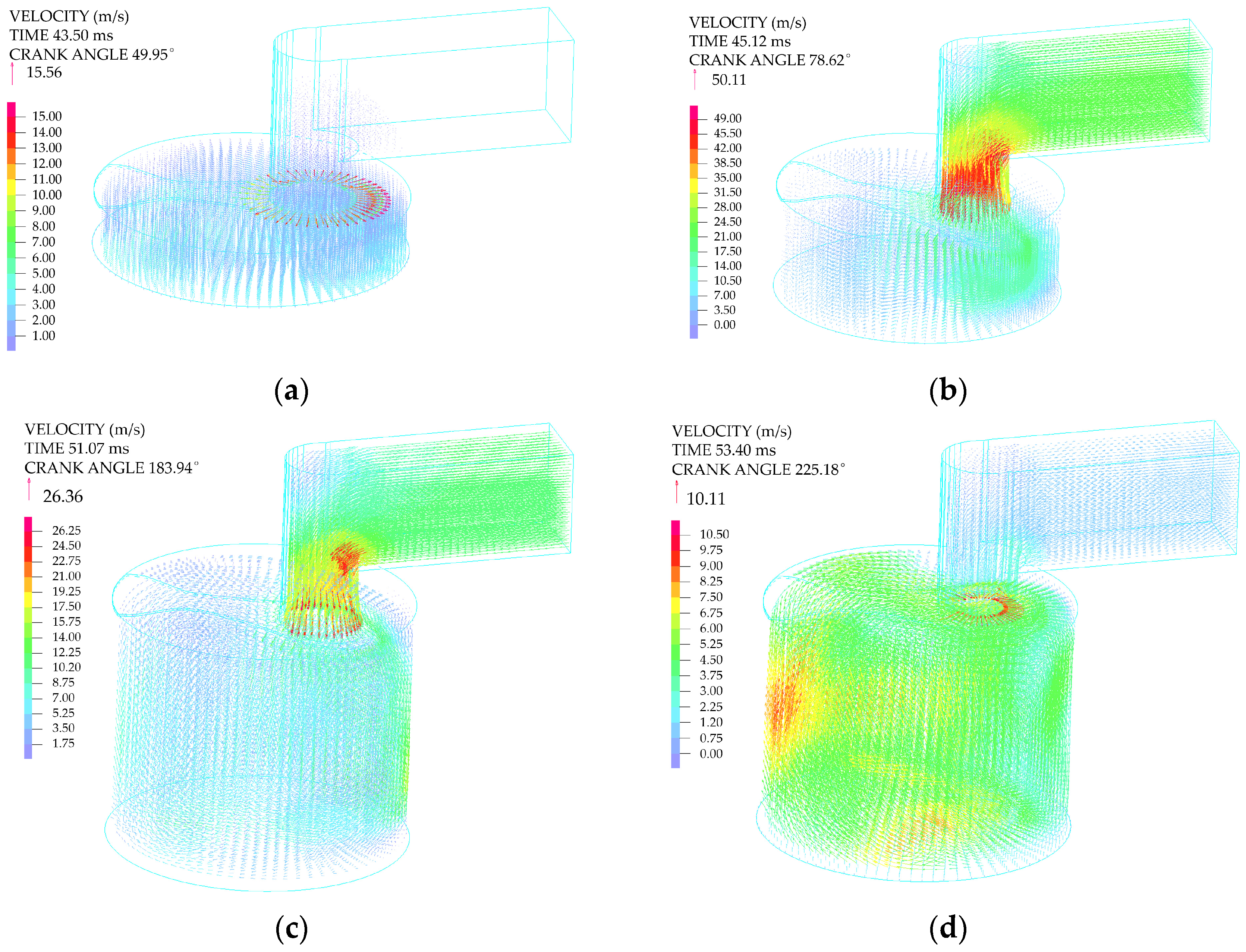

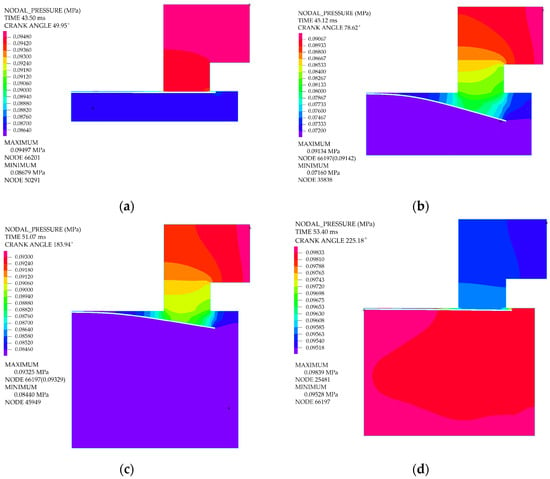

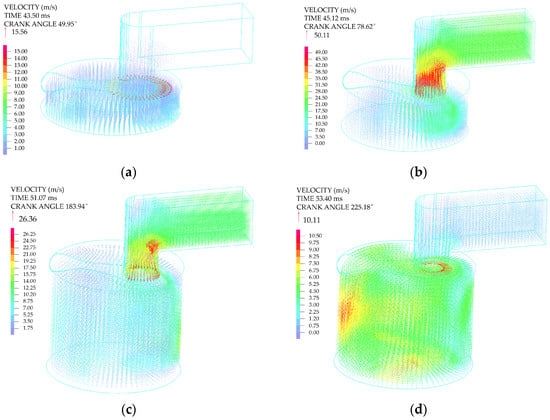

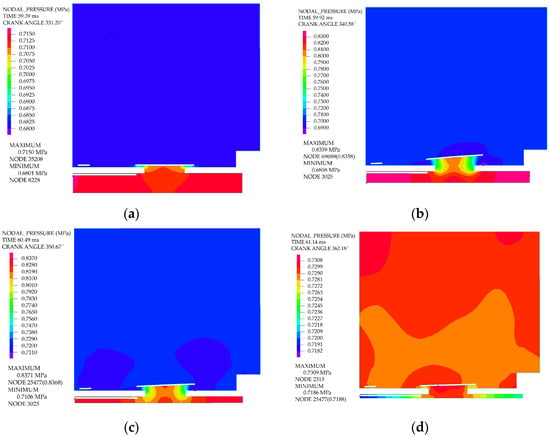

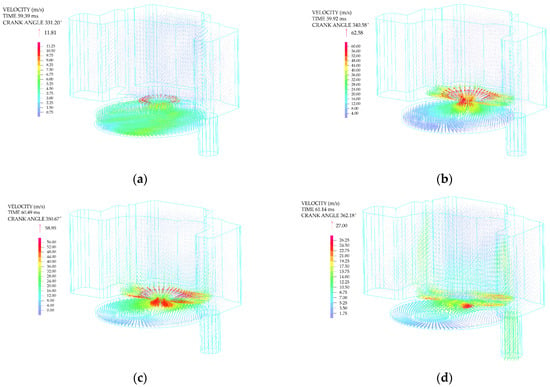

Figure 16 and Figure 17 show snapshots of the unsteady flow characteristics at four distinct time instants during the suction process. The evolution of the gas flow field was associated with the piston kinematics and the deformation of the valve plate. The deflection of the valve plate was governed by the dynamic balance among its inertial force, elastic restoring force, and the instantaneous surface pressure load.

Figure 16.

Pressure contours of the fluid domain during the suction process at different crank angles: (a) 49.95°; (b) 78.62°; (c) 183.94°; (d) 225.18°.

Figure 17.

Velocity vectors of the fluid domain during the suction process at different crank angles: (a) 49.95°; (b) 78.62°; (c) 183.94°; (d) 225.18°.

Upon completion of the expansion stroke, the in-cylinder pressure dropped just below the suction pipe pressure, prompting the opening of the suction valve and the initiation of gas intake. During the initial stage of suction, the restricted flow area at the valve gap led to a progressive decrease in the in-cylinder pressure as the piston advanced, concurrently causing a gradual accumulation of the pressure differential across the valve plate. As the valve lift increased, the enlarged flow area through the valve gap allowed a greater inflow of gas into the cylinder, raising the in-cylinder pressure and thereby reducing the pressure differential across the valve plate. Meanwhile, the elastic restoring force of the valve plate intensified. Once the pressure differential became insufficient to counteract the restoring force, the valve plate began to return toward the valve seat. The subsequent reduction in valve lift decreased the elastic restoring force; when the gas-induced thrust again exceeded this reduced force, the valve lift resumed increasing. These periodic fluctuations between gas thrust and elastic restoring force induced sustained oscillations of the valve plate.

As the piston reached its lowest position at BDC, the suction valve plate did not fully rest on the valve seat. As the piston moved from BDC back toward TDC, a small amount of gas flowed back into the suction pipe, as illustrated in Figure 17d.

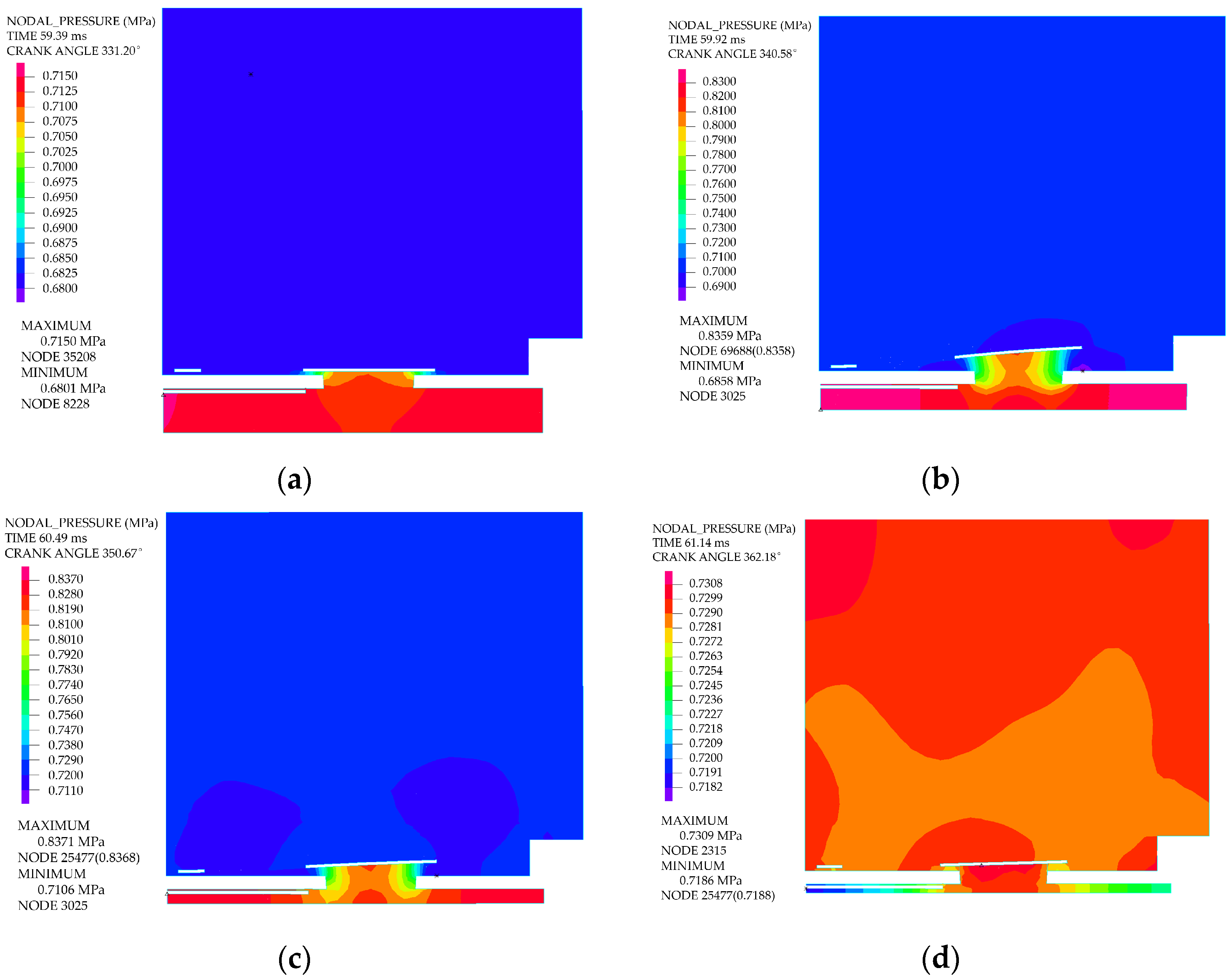

4.3. FSI Characteristics of the Discharge Reed Valve

Figure 18 and Figure 19 illustrate the evolution characteristics of the flow field captured at four distinct time instants during the discharge process. The upward stroke of the piston drove a rapid rise in the in-cylinder pressure during the compression process. When the pressure within the cylinder marginally surpassed that of the discharge chamber, the discharge valve plate actuated, thereby initiating the discharge process.

Figure 18.

Pressure contours of the fluid domain during the discharge process at different crank angles: (a) 331.20°; (b) 340.58°; (c) 350.67°; (d) 362.18°.

Figure 19.

Velocity vectors of the fluid domain during the discharge process at different crank angles: (a) 331.20°; (b) 340.58°; (c) 350.67°; (d) 362.18°.

At the onset of discharge, the upward motion of the piston caused a continuous rise in cylinder pressure. Although gas outflow moderated the pressurization rate within the cylinder, it remained faster than that of the discharge chamber. Consequently, the difference in gas pressure acting on the two sides of the valve plate gradually amplified, and the valve displacement increased.

Upon impact with the lift limiter, the rebound force imparted a reverse acceleration to the valve plate, compelling it to fall back toward the seat. The rebounding motion of the discharge valve plate altered the gas flow rate and flow resistance through the valve port, resulting in transient pressure fluctuations across it. The displacement of the discharge valve plate exhibited dynamic fluctuations influenced by the interaction among the in-cylinder pressure, the pressure within the valve chamber, and the elastic restoring force and inertial force of the valve plate.

As the piston approached TDC, its upward velocity gradually diminished to zero. The gas discharge rate from the cylinder slowed, the in-cylinder pressure began to decline, and the net gas pressure force exerted on the valve plate progressively decreased. As the piston began its descent from TDC, the cylinder pressure dropped sharply, inducing the rapid seating of the discharge valve plate.

5. Discussion

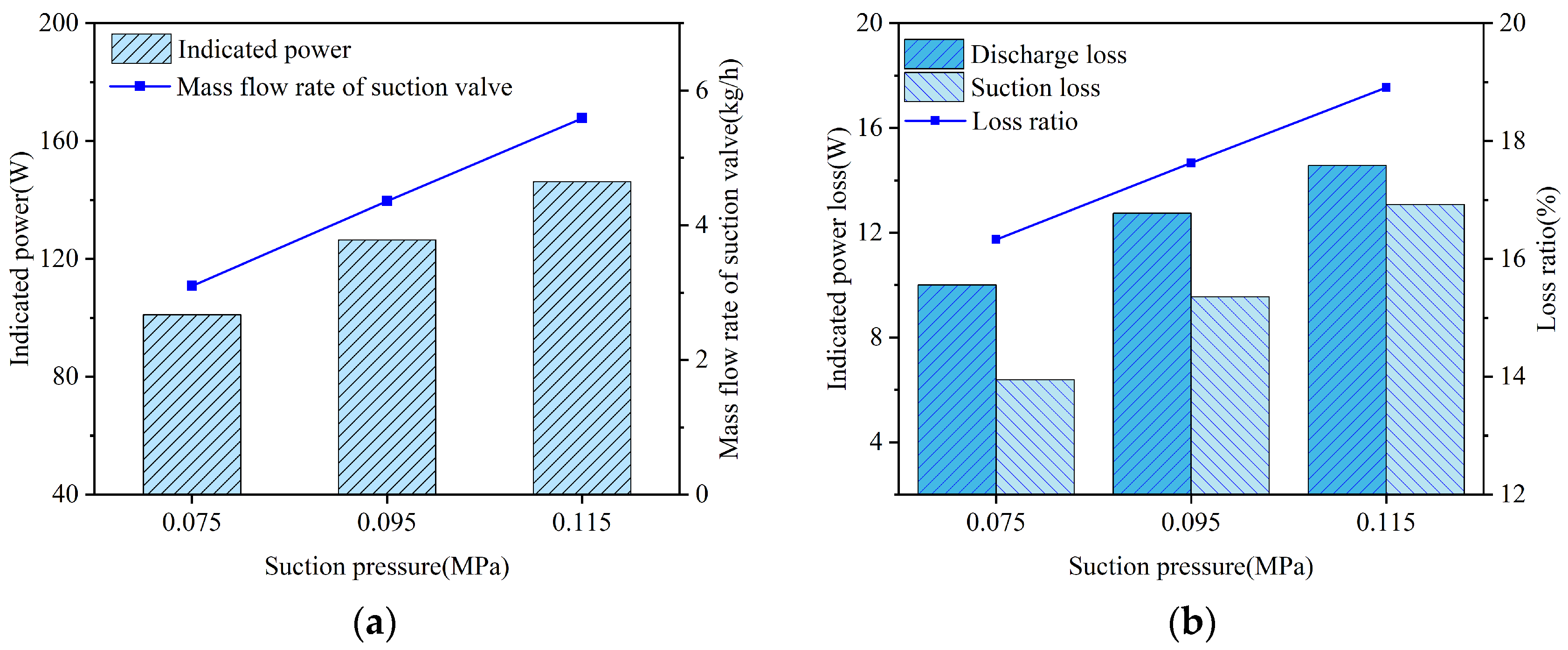

To investigate the influence of the FSI characteristics of reed valves on the overall performance of the compressor, a systematic parameter study was conducted. The operating parameters (suction pressure, rotational speed) and geometric parameters (clearance volume, thicknesses of the suction and discharge valve plates) were varied sequentially, as shown in Table 3. The effects of these variations were analyzed by comparing the resulting valve dynamics, energy losses during the suction and discharge processes, indicated power, and mass flow rate.

Table 3.

Case matrix.

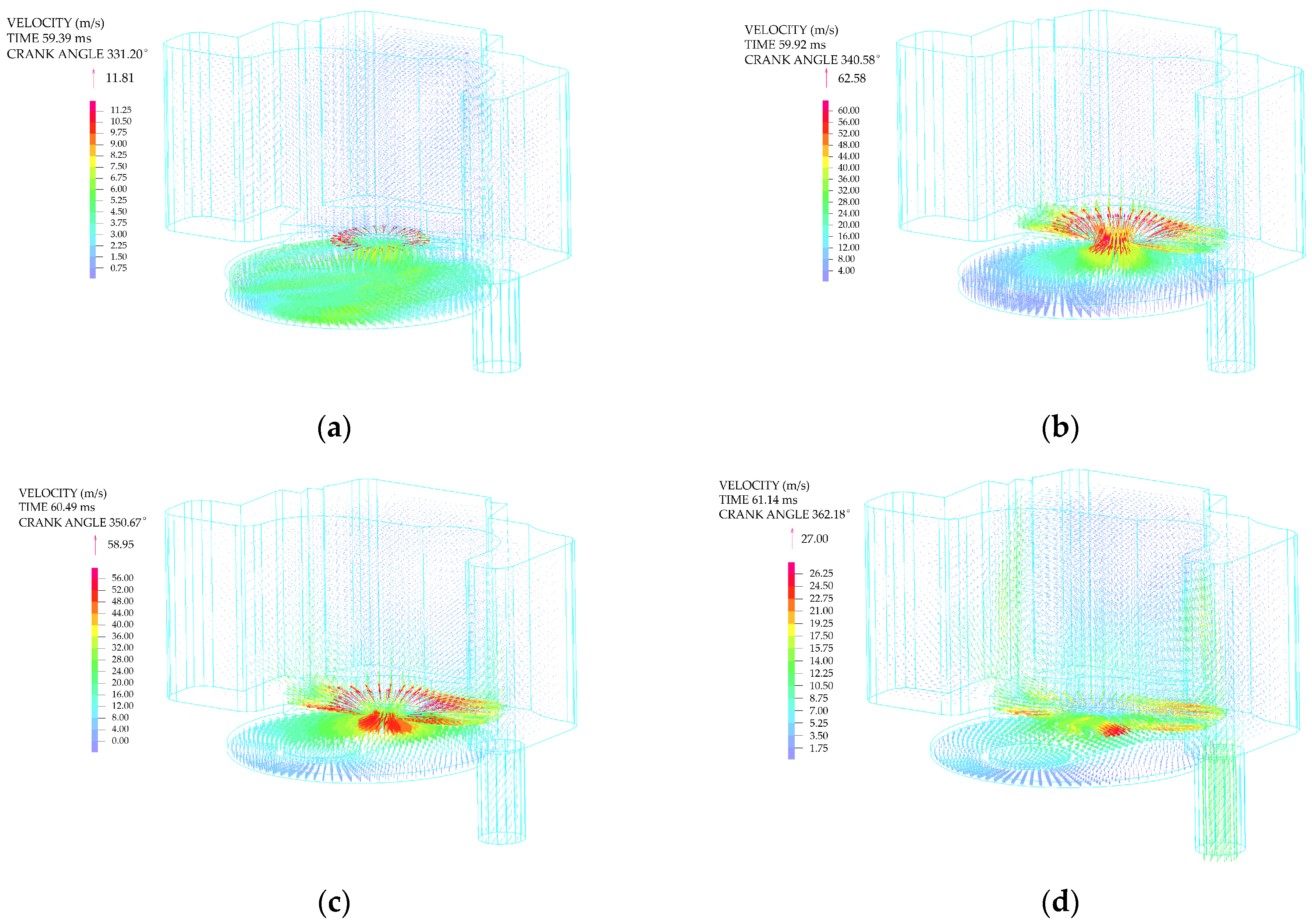

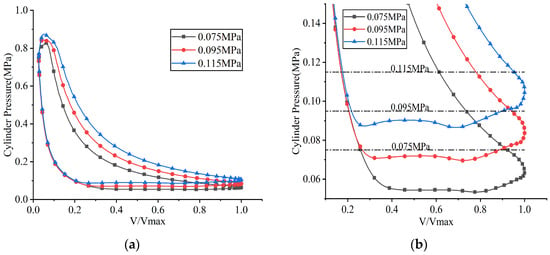

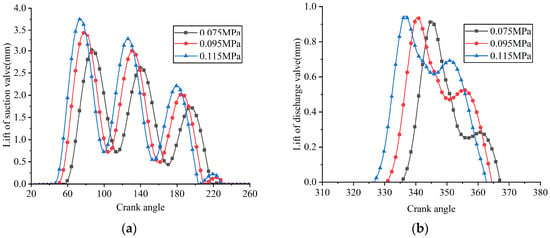

5.1. Suction Pressure

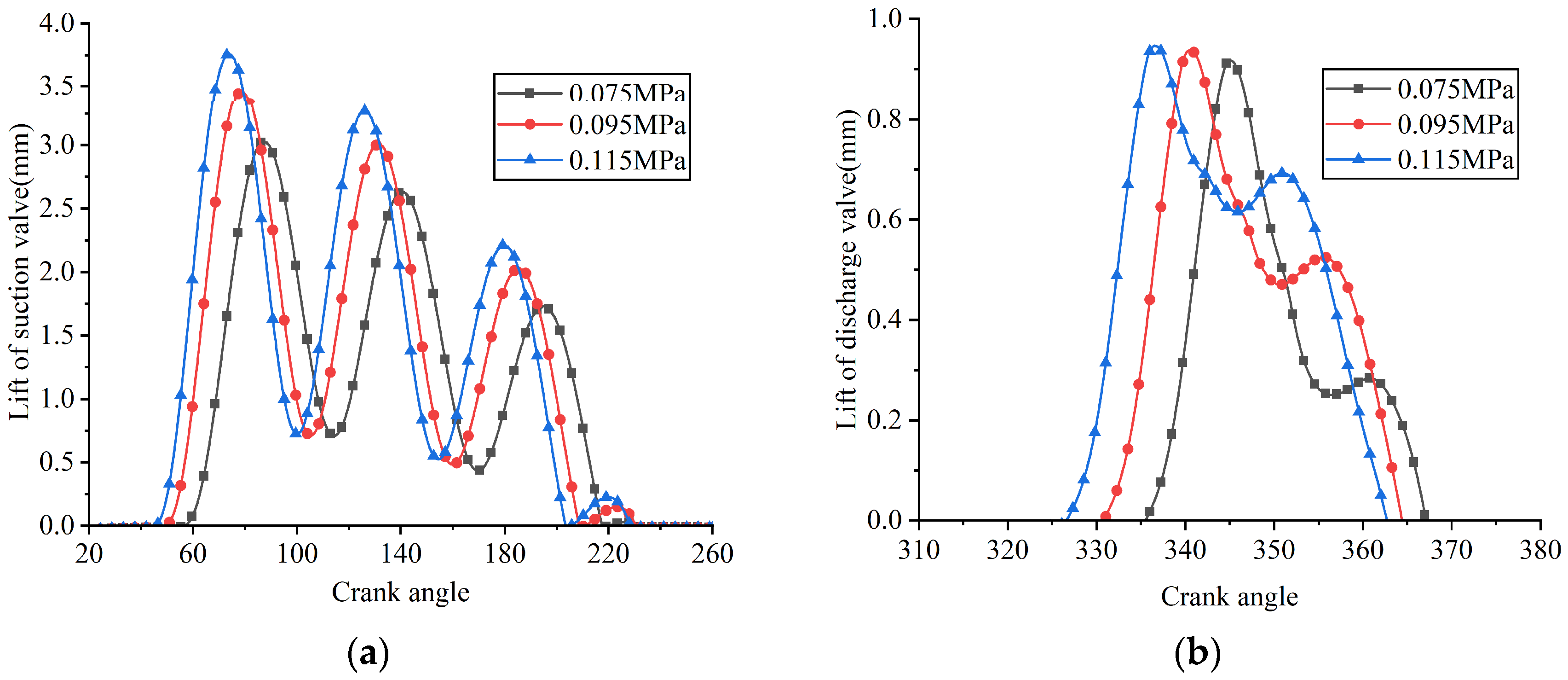

A series of FSI simulations was performed by adjusting the suction pressure while keeping other operating parameters constant. The simulated results, including the in-cylinder pressure, valve lifts, and instantaneous flow rates passing through the valve ports, are illustrated in Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22, respectively. Here, valve lift is defined as the vertical displacement at the center of the valve plate head (Point A on the suction valve plate, see Figure 13a, and the corresponding point on the discharge valve plate). Additionally, the indicated power losses during the suction and discharge processes, as well as the total indicated power and average flow rate, were computed (see Figure 23).

Figure 20.

p–V indicator diagrams under different suction pressures: (a) overall view; (b) partial enlarged view.

Figure 21.

Lifts of the suction and discharge valve plates under different suction pressures: (a) suction reed valve; (b) discharge reed valve.

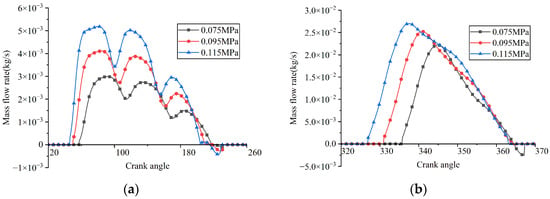

Figure 22.

Instantaneous flow rates through the valve ports under different suction pressures: (a) suction reed valve; (b) discharge reed valve.

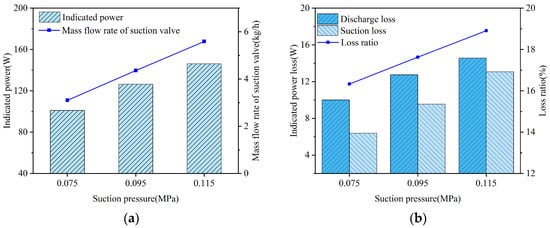

Figure 23.

Key performance parameters of the compressor and reed valves under different suction pressures: (a) indicated power and mass flow rate; (b) suction and discharge losses.

At suction pressures of 0.075 MPa, 0.095 MPa, and 0.115 MPa, the corresponding opening angles of the suction valve were predicted to be 56.853°, 49.596°, and 45.525°, respectively, while the maximum lifts of the suction valve plate were 3.025 mm, 3.453 mm, and 3.756 mm, respectively. An increase in suction pressure caused the gas within the clearance volume to expand more rapidly to reach pressure equilibrium, thereby shortening the expansion process and causing the suction valve plate to open earlier. Additionally, the increased suction pressure amplified the pressure differential across the suction valve plate, consequently increasing its maximum lift.

At the same suction pressure levels, the opening angles of the discharge valve plate were 335.451°, 330.849°, and 326.601°, respectively, while its maximum lifts were 0.917 mm, 0.939 mm, and 0.947 mm, respectively. As the compression process shortened with rising suction pressure, the discharge valve opened earlier (see Figure 21a). The observed increase in the maximum displacement at the center of the valve plate head was attributed to the greater pressure differential across the discharge valve, which resulted from the elevated suction pressure.

The average flow rate through the suction valve was determined to be 3.097 kg/h at a suction pressure of 0.075 MPa, 4.360 kg/h at 0.095 MPa, and 5.589 kg/h at 0.115 MPa. Two factors contributed to the increase in flow rate: first, the effective suction volume expanded due to the earlier opening time of the valve; second, the density of the suction gas increased as a result of the increased suction pressure.

Regarding the indicated power, simulations yielded values of 100.995 W at a suction pressure of 0.075 MPa, 126.407 W at 0.095 MPa, and 146.165 W at 0.115 MPa. The total indicated power increased with suction pressure. This trend was attributed to the dominant role of the increased mass flow rate (resulting from higher suction pressure), which outweighed the decrease in specific power consumption caused by the lower pressure ratio.

The indicated power losses during the suction process at the aforementioned suction pressure levels were 10.109 W, 12.742 W, and 14.568 W, respectively. This increase in suction loss was attributed to the increased velocity and density of the gas passing through the suction valve.

The indicated power losses during the discharge process were 6.382 W, 9.547 W, and 13.071 W, respectively, while the maximum in-cylinder pressures were 0.828 MPa, 0.843 MPa, and 0.874 MPa, respectively, at the corresponding suction pressures. An increase in suction pressure led to a decreased pressure ratio, a lower discharge temperature, and a higher density of the discharged gas. However, the increase in mass flow rate induced by the increased suction pressure played a dominant role. Thus, the volumetric flow rate through the discharge valve increased, leading to a higher gas velocity at the discharge valve port and, consequently, an increase in the energy loss of the discharge valve.

5.2. Rotational Speed

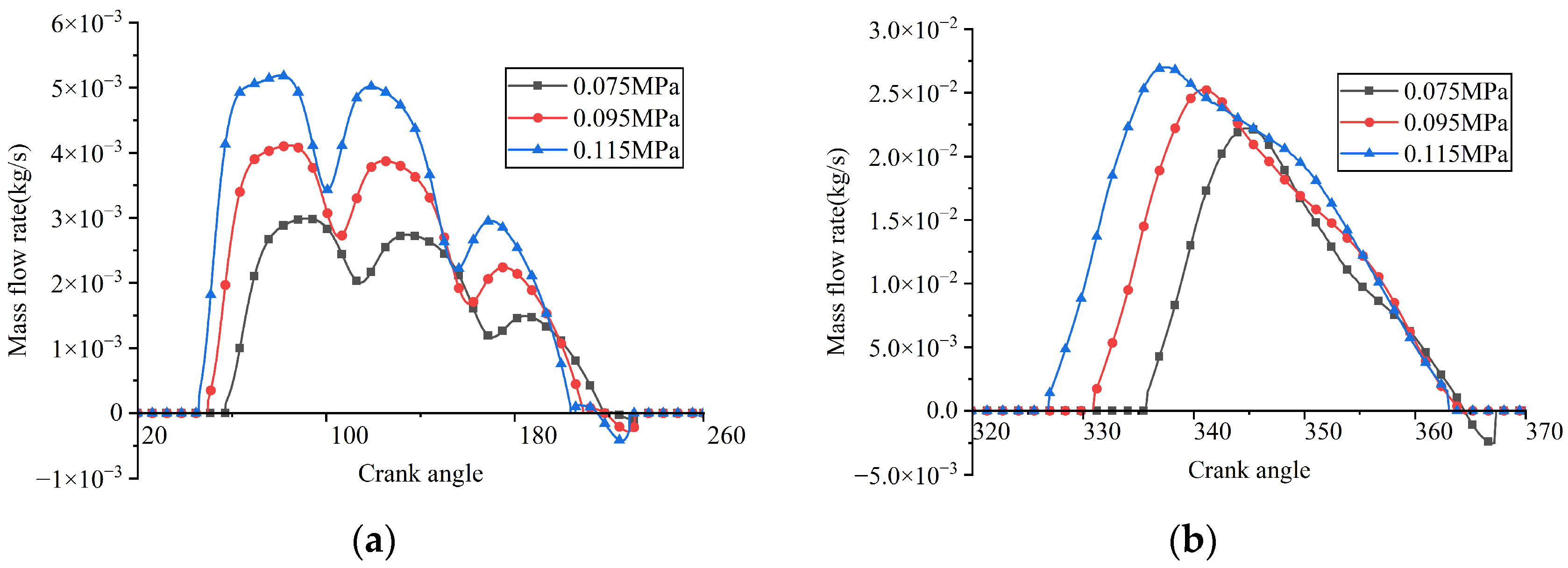

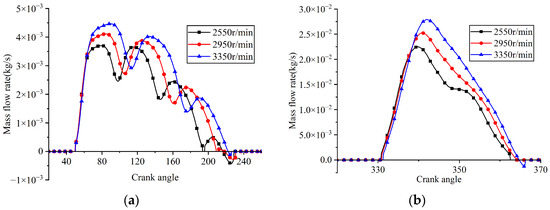

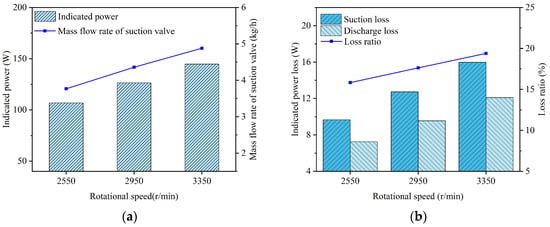

A series of FSI simulations was conducted with the rotational speed varied while other parameters remained constant. The simulated results, including the in-cylinder pressure, valve lifts, and instantaneous flow rates passing through the valve ports, are illustrated in Figure 24, Figure 25 and Figure 26, respectively. Additionally, the indicated power losses during the suction and discharge processes, as well as the total indicated power and average flow rate, were computed (see Figure 27).

Figure 24.

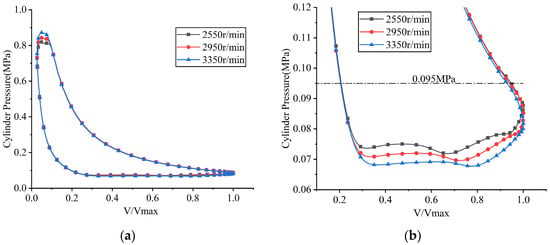

p–V indicator diagrams at different rotational speeds: (a) overall view; (b) partial enlarged view.

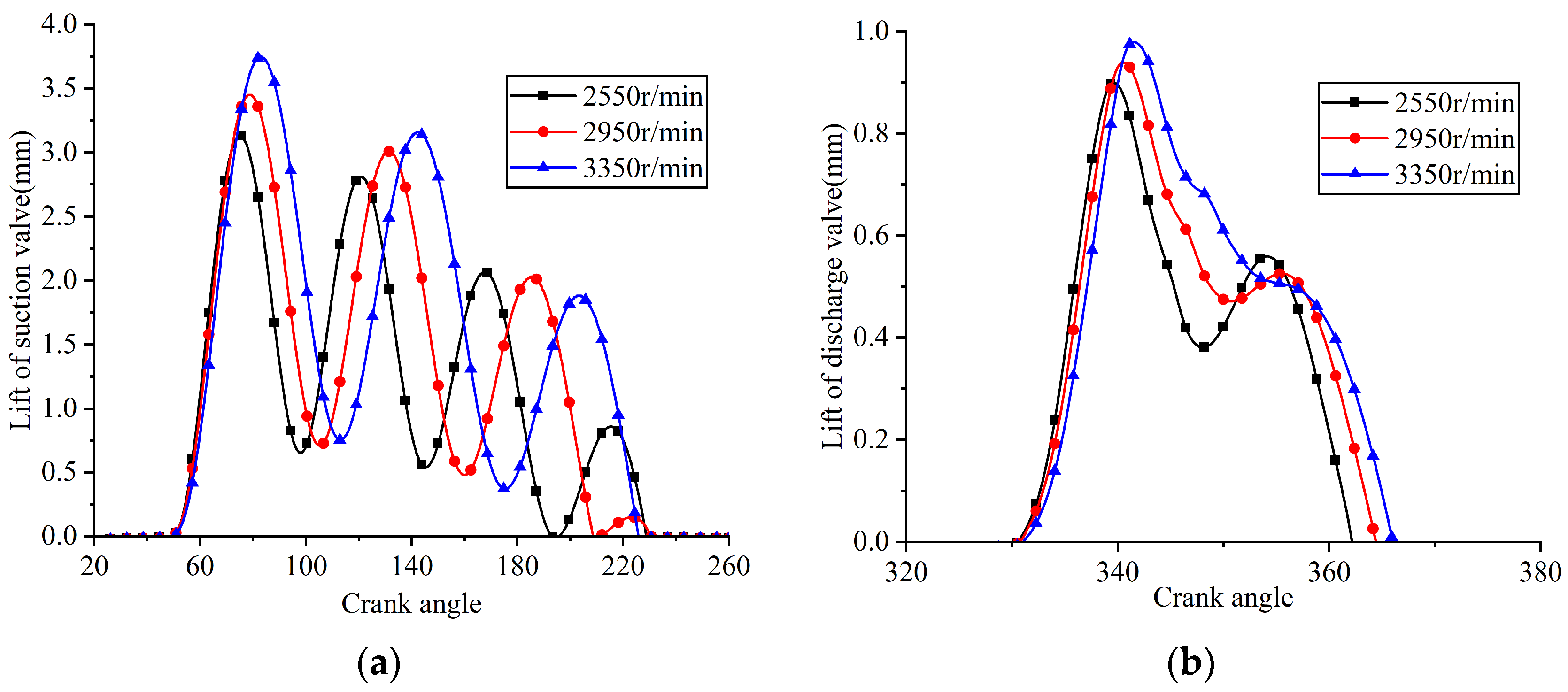

Figure 25.

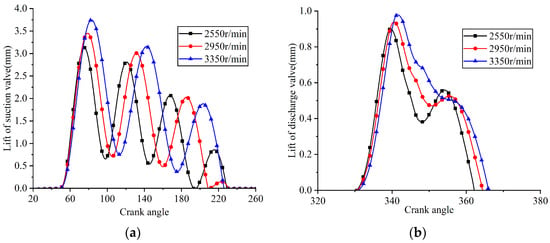

Lifts of the suction and discharge valve plates at different rotational speeds: (a) suction reed valve; (b) discharge reed valve.

Figure 26.

Instantaneous flow rates through the valve ports at different rotational speeds: (a) suction reed valve; (b) discharge reed valve.

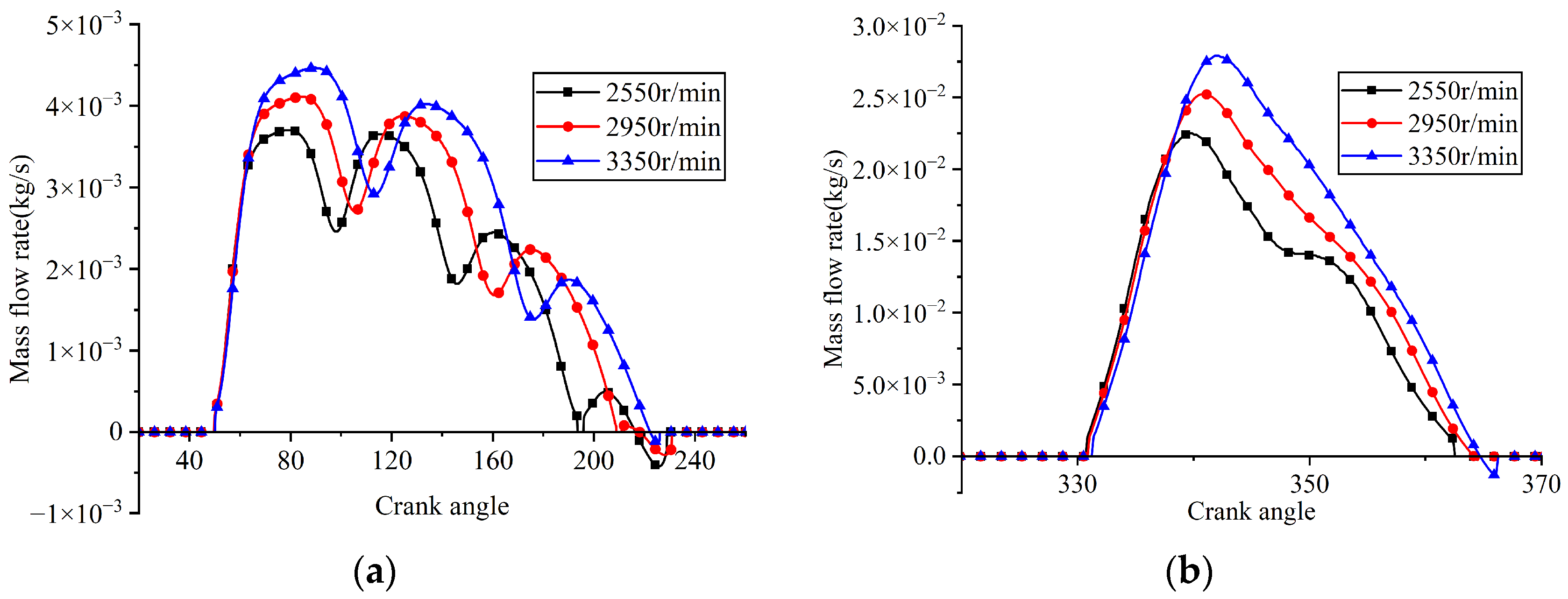

Figure 27.

Key performance parameters of the compressor and reed valves at different rotational speeds: (a) indicated power and mass flow rate; (b) suction and discharge losses.

The crank angle at which the suction valve began to open remained almost unchanged with increasing rotational speed, as the piston stroke required to expand the residual gas within the clearance volume was nearly constant. Simulated results showed that the maximum lift of the suction valve plate was 3.129 mm at a rotational speed of 2550 rpm, 3.453 mm at 2950 rpm, and 3.747 mm at 3350 rpm. The observed increase in the maximum lift of the suction valve plate with increasing rotational speed was primarily attributed to the increased pressure differential across the valve plate, which was caused by increased flow resistance at higher gas velocities. The average pressure inside the cylinder during the suction process demonstrated a decreasing trend as the rotational speed increased, with computed values of 0.0749 MPa at 2550 rpm, 0.0720 MPa at 2950 rpm, and 0.0692 MPa at 3350 rpm. Meanwhile, the indicated power loss during the suction process increased with rotational speed, with values of 9.668 W at 2550 rpm, 12.742 W at 2950 rpm, and 15.973 W at 3350 rpm.

When the rotational speeds were 2550 rpm, 2950 rpm, and 3350 rpm, the crank angles at which the discharge valve began to open were 330.672°, 330.849°, and 331.025°, respectively, and the maximum displacements at the center of the discharge valve plate head were 0.9 mm, 0.939 mm, and 0.979 mm, respectively. The minor change in the opening angle of the discharge valve with increasing rotational speed was attributed to the close similarity of the pressure-crank angle variation law during the compression process as rotational speed rose. The increase in the maximum lift of the discharge valve plate with increasing rotational speed was primarily due to the increased differential in gas pressures exerted on either side of the discharge valve plate, which was caused by increased flow resistance at higher gas velocities. The average in-cylinder pressure during the discharge process showed an increasing trend as the rotational speed increased, with computed values of 0.796 MPa at 2550 rpm, 0.814 MPa at 2950 rpm, and 0.831 MPa at 3350 rpm. Meanwhile, the indicated power loss during the discharge process also increased with rotational speed, with values of 7.249 W at 2550 rpm, 9.547 W at 2950 rpm, and 12.100 W at 3350 rpm.

When the rotational speeds were 2550 rpm, 2950 rpm, and 3350 rpm, the average flow rates passing through the suction valve port were 3.768 kg/h, 4.360 kg/h, and 4.882 kg/h, respectively, and the indicated power values were 106.836 W, 126.407 W, and 144.735 W, respectively. The mass flow rate through the suction valve increased with rotational speed due to the higher frequency of suction events per unit time. The indicated power increased with rotational speed due to a rise in both the work consumed per cycle and the number of cycles per unit time.

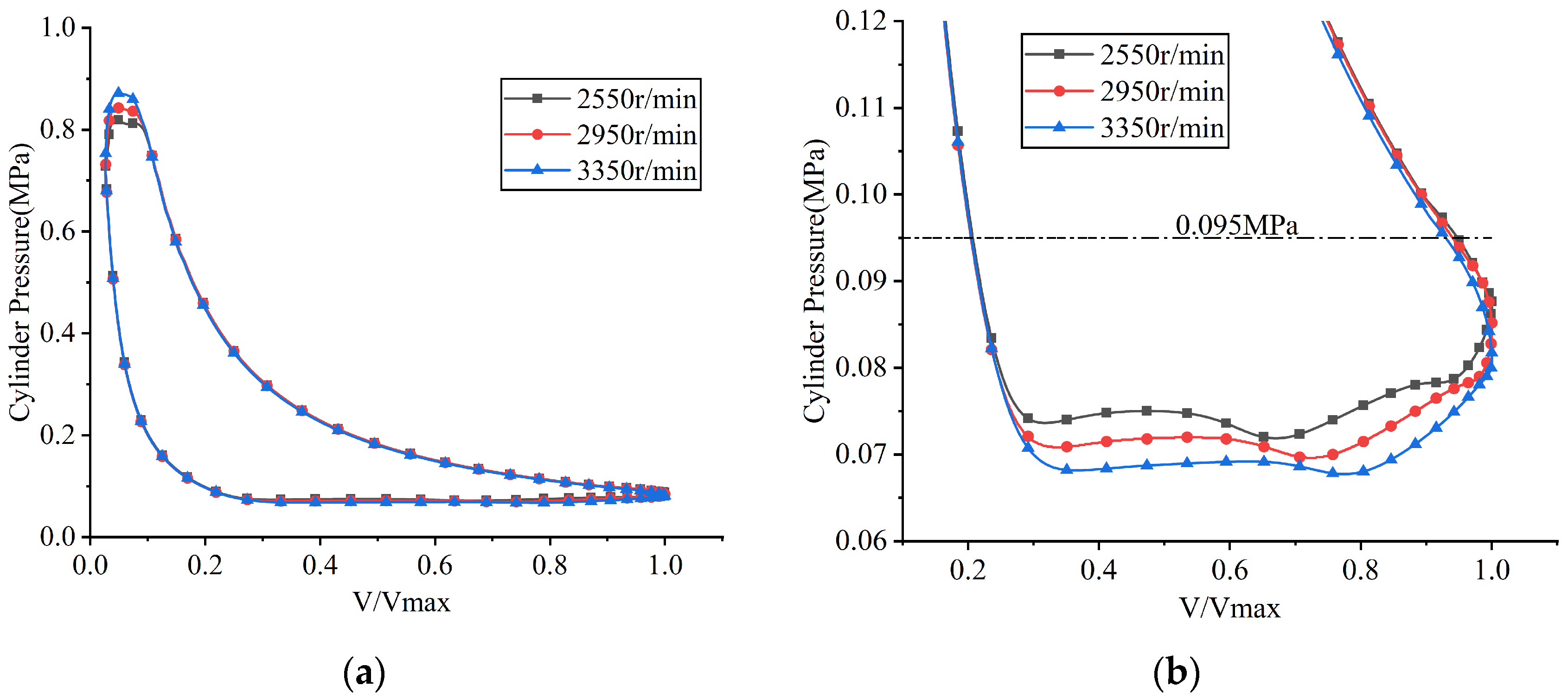

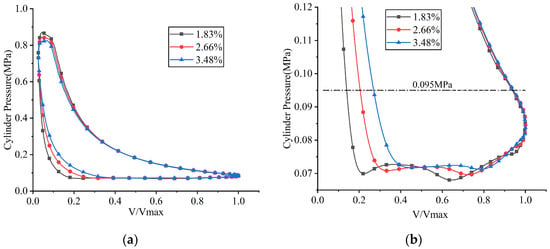

5.3. Clearance Volume

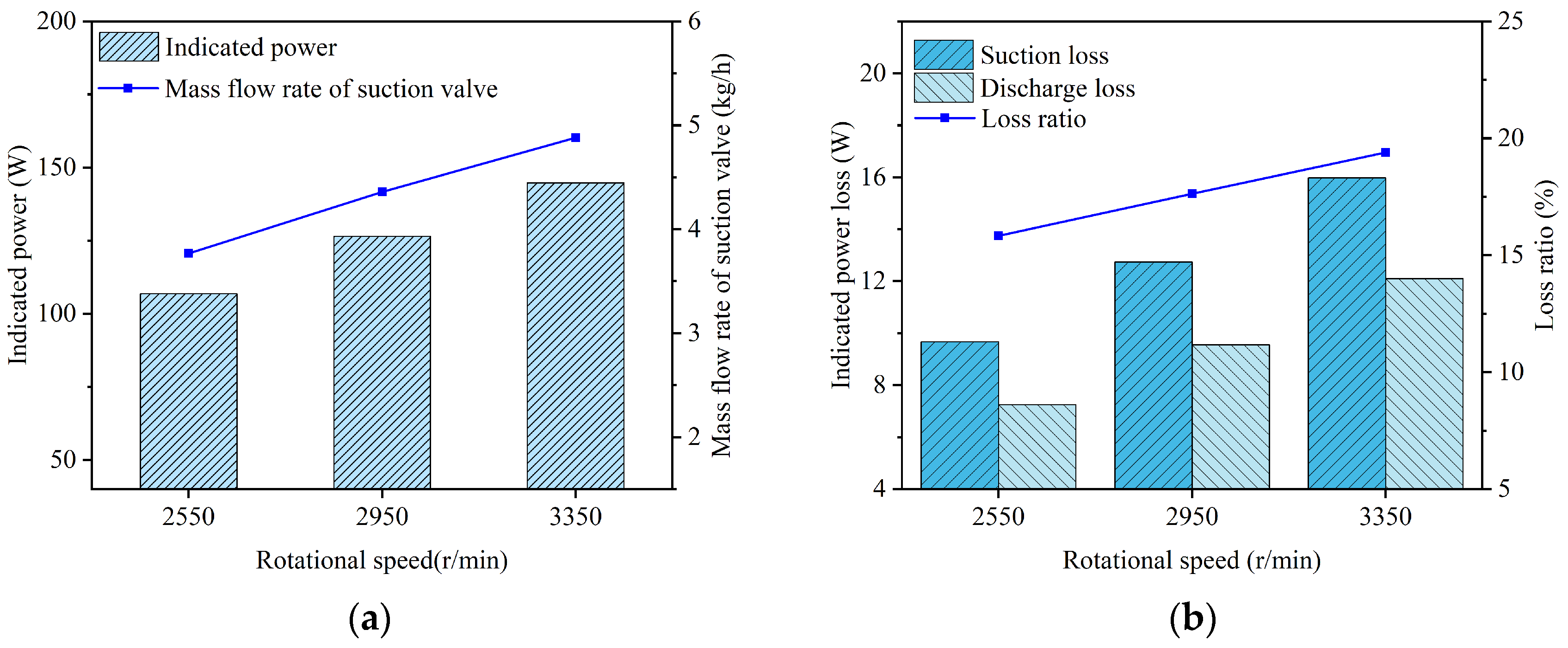

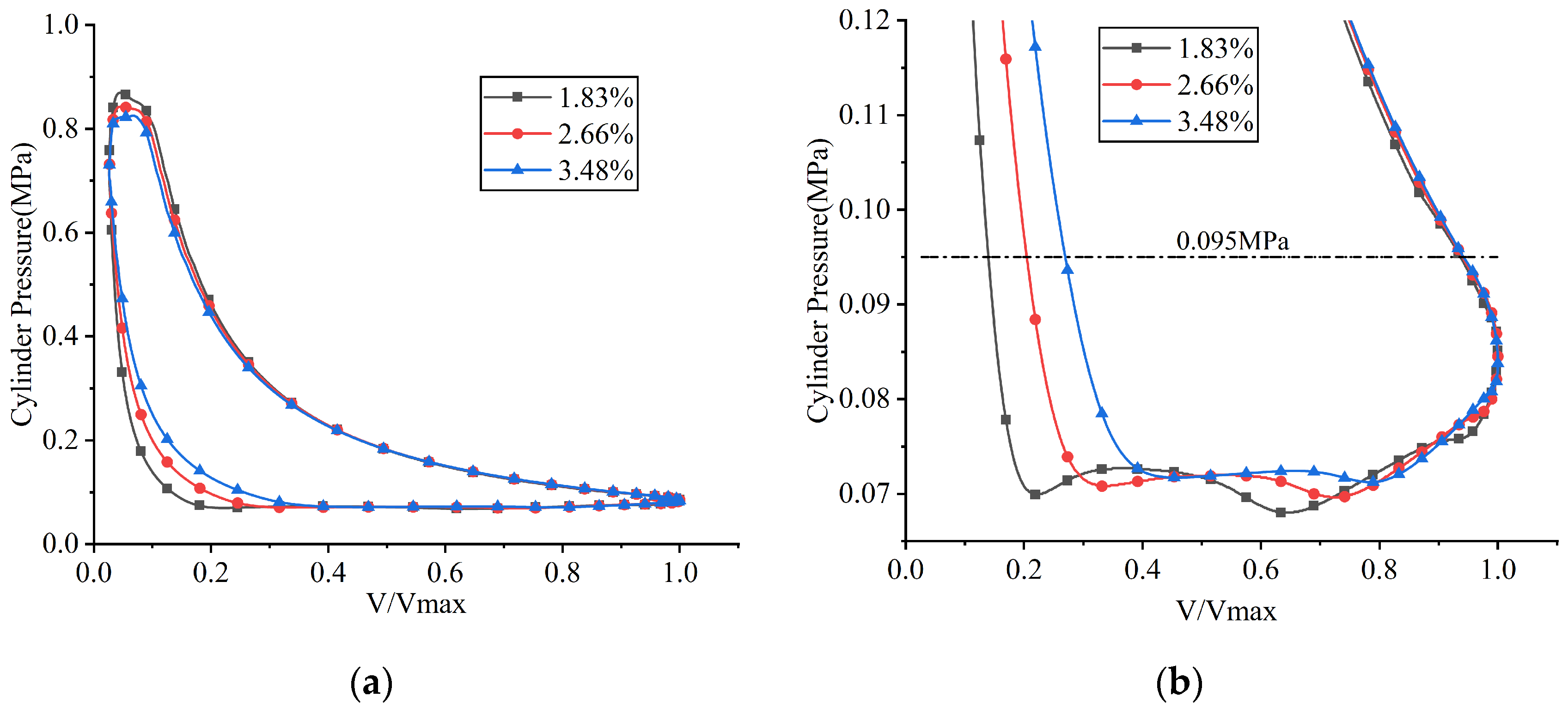

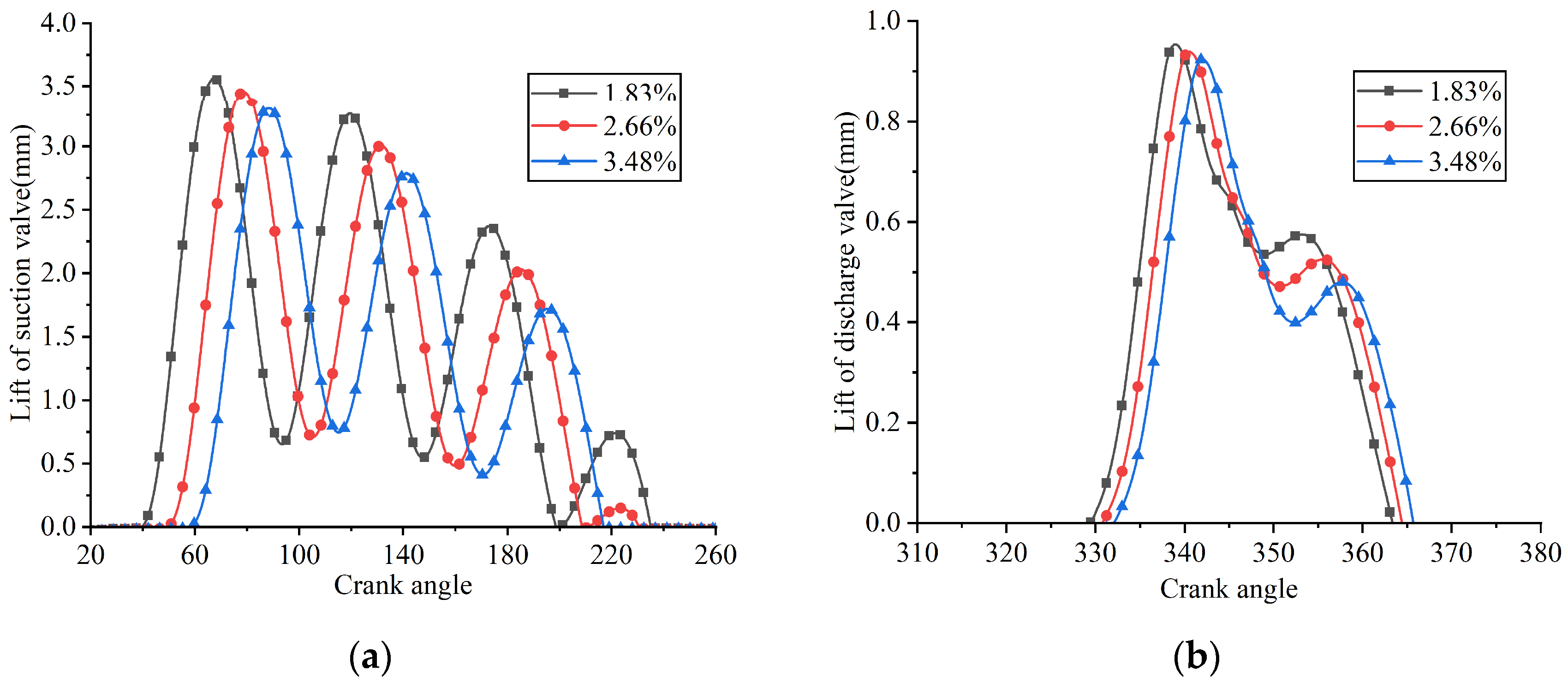

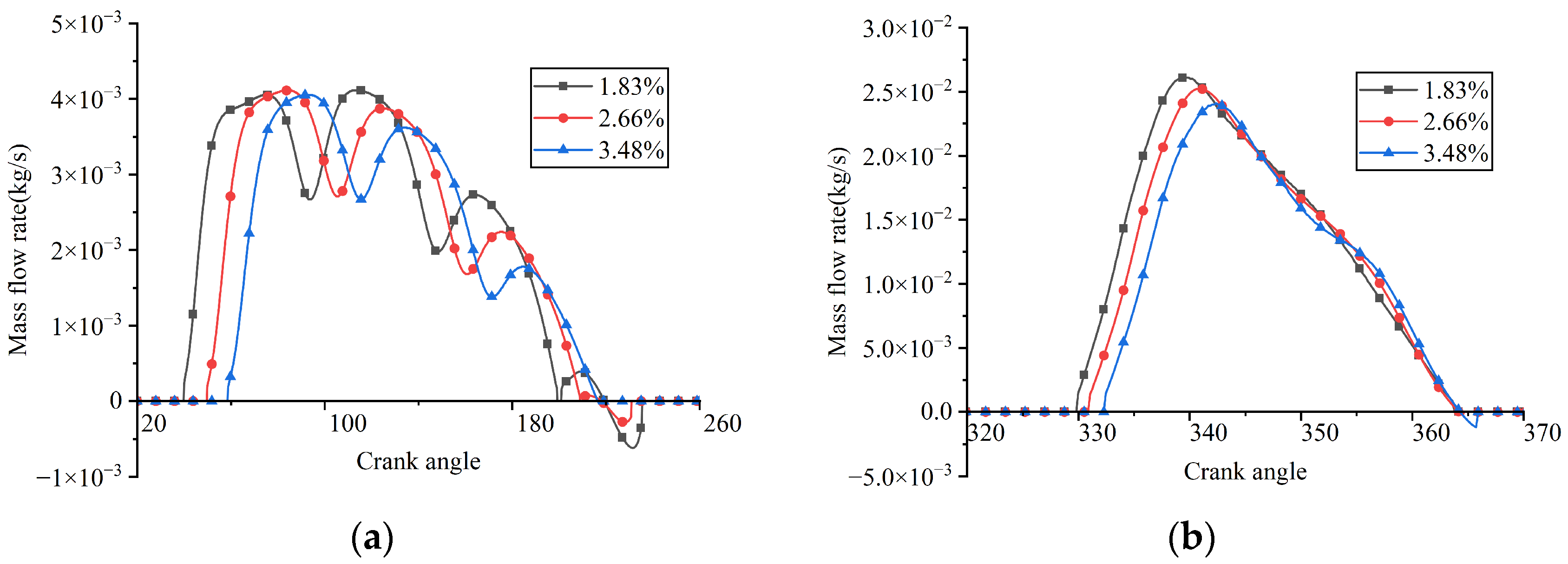

In the numerical model, the clearance volume was adjusted by varying the cylinder height at the initial moment of the simulation. The simulated results, including the in-cylinder pressure, valve lifts, and instantaneous flow rates passing through the valve ports, are illustrated in Figure 28, Figure 29 and Figure 30, respectively. Additionally, the indicated power losses during the suction and discharge processes, as well as the total indicated power and average flow rate, were computed (see Figure 31).

Figure 28.

p–V indicator diagrams under different clearance volume ratios: (a) overall view; (b) partial enlarged view.

Figure 29.

Lifts of the suction and discharge valve plates under different clearance volume ratios: (a) suction reed valve; (b) discharge reed valve.

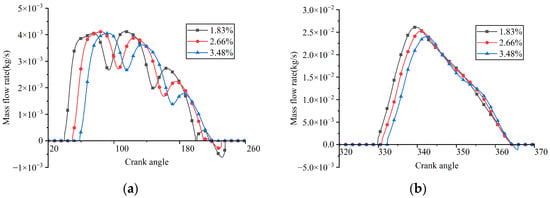

Figure 30.

Instantaneous flow rates through the valve ports under different clearance volume ratios: (a) suction reed valve; (b) discharge reed valve.

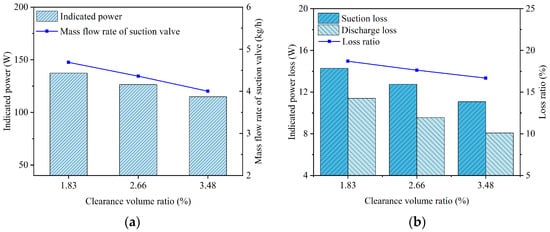

Figure 31.

Key performance parameters of the compressor and reed valves under different clearance volume ratios: (a) indicated power and mass flow rate; (b) suction and discharge losses.

When the clearance volume ratios were 1.83%, 2.66%, and 3.48%, the crank angles at which the suction valve began to open were 39.507°, 49.596°, and 58.269°, respectively; the maximum lifts of the suction valve plate were 3.562 mm, 3.453 mm, and 3.304 mm, respectively. The delay in the suction valve’s opening was attributed to the prolonged duration of the expansion process with increasing clearance volume. The decrease in the maximum lift of the suction valve plate was attributed to the reduced pressure differential across the valve plate as the clearance volume increased. The average in-cylinder pressure during the suction process was calculated as 0.0712 MPa at a clearance volume ratio of 1.83%, 0.0720 MPa at 2.66%, and 0.0731 MPa at 3.48%.

When the clearance volume ratios were 1.83%, 2.66%, and 3.48%, the average flow rates passing through the suction valve port were 4.688 kg/h, 4.360 kg/h, and 4.003 kg/h, respectively. The decrease in mass flow rate with increasing clearance volume was attributed to the reduction in the effective suction volume of the reciprocating compressor.

When the clearance volume ratios were 1.83%, 2.66%, and 3.48%, the crank angles at which the discharge valve began to open were 329.433°, 330.849°, and 332.088°, respectively; the maximum displacements at the center of the discharge valve plate head were 0.953 mm, 0.939 mm, and 0.924 mm, respectively. As the mass flow rate decreased with increasing clearance volume, the flow velocity through the discharge valve was reduced. This reduction led to a decrease in both the discharge loss and the average in-cylinder pressure during the discharge process. The average in-cylinder pressure during the discharge process was calculated as 0.827 MPa at a clearance volume ratio of 1.83%, 0.814 MPa at 2.66%, and 0.803 MPa at 3.48%.

When the clearance volume ratios were 1.83%, 2.66%, and 3.48%, the indicated power values were 137.319 W, 126.407 W, and 114.886 W, respectively; the indicated power losses during the suction process were 14.279 W, 12.742 W, and 11.083 W, respectively; and the indicated power losses during the discharge process were 11.396 W, 9.547 W, and 8.076 W, respectively. As the clearance volume increased, the expansion work increased, while the suction loss, compression work, and discharge loss decreased owing to the reduction in mass flow rate. Consequently, the total indicated work decreased.

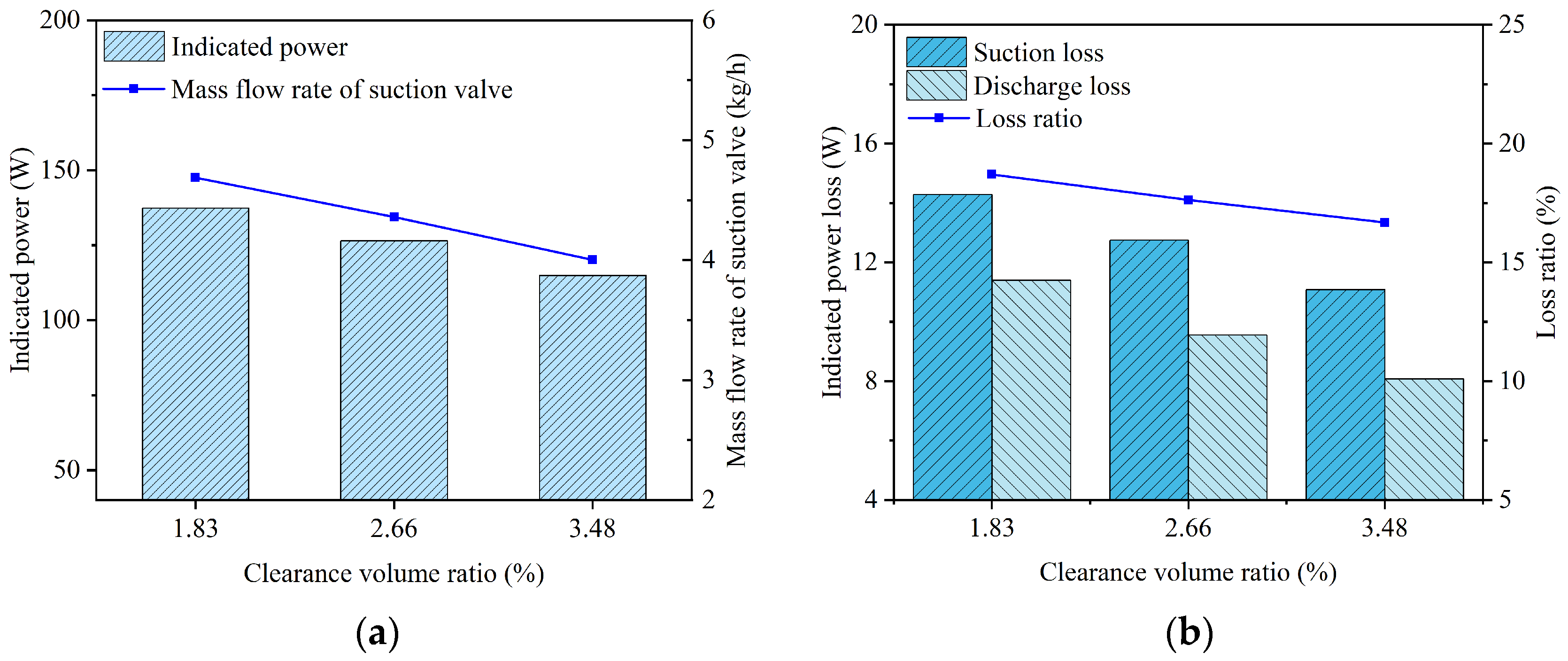

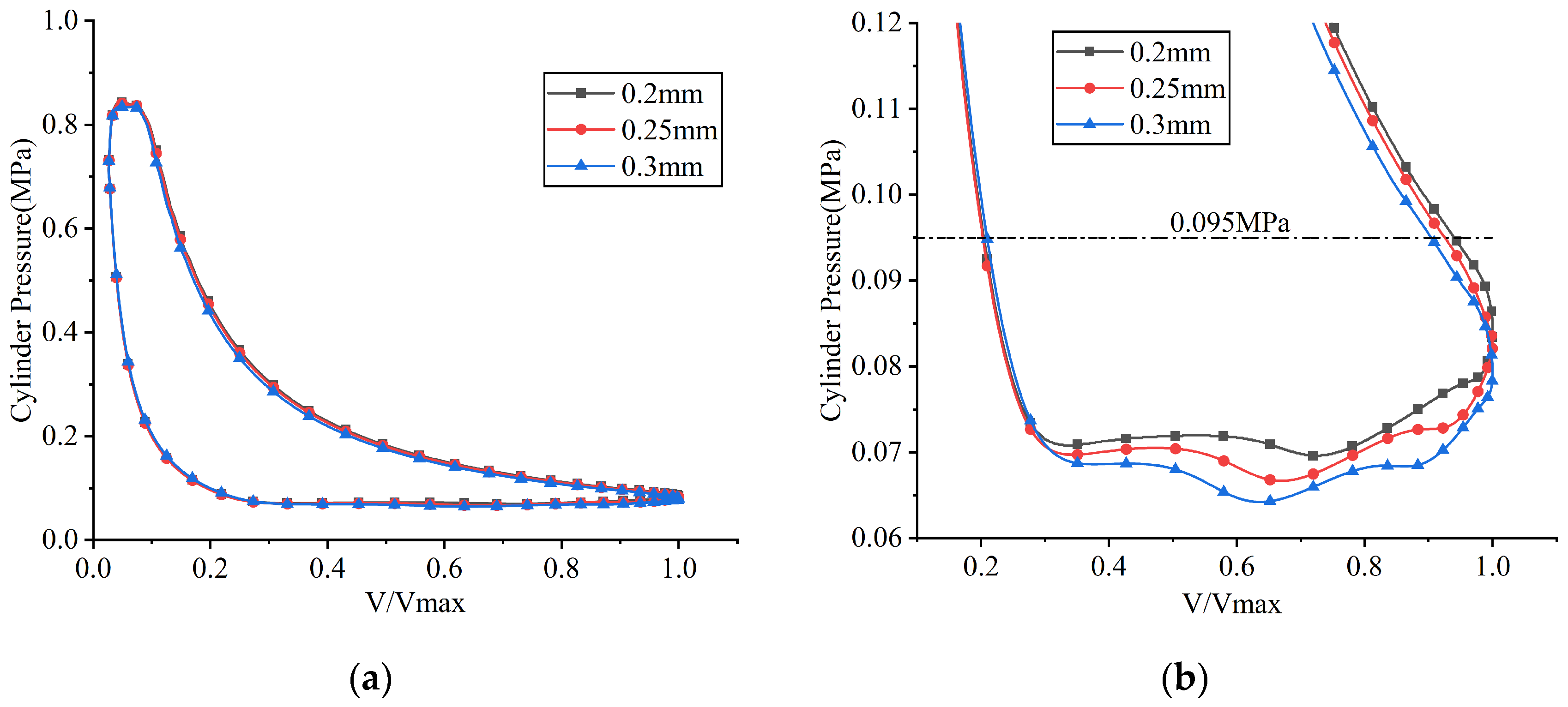

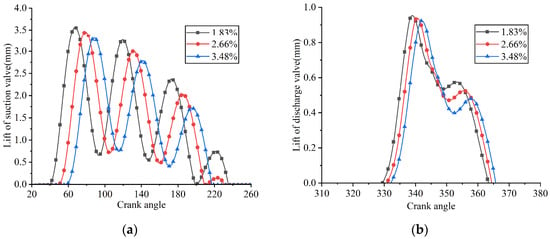

5.4. Suction Valve Plate Thickness

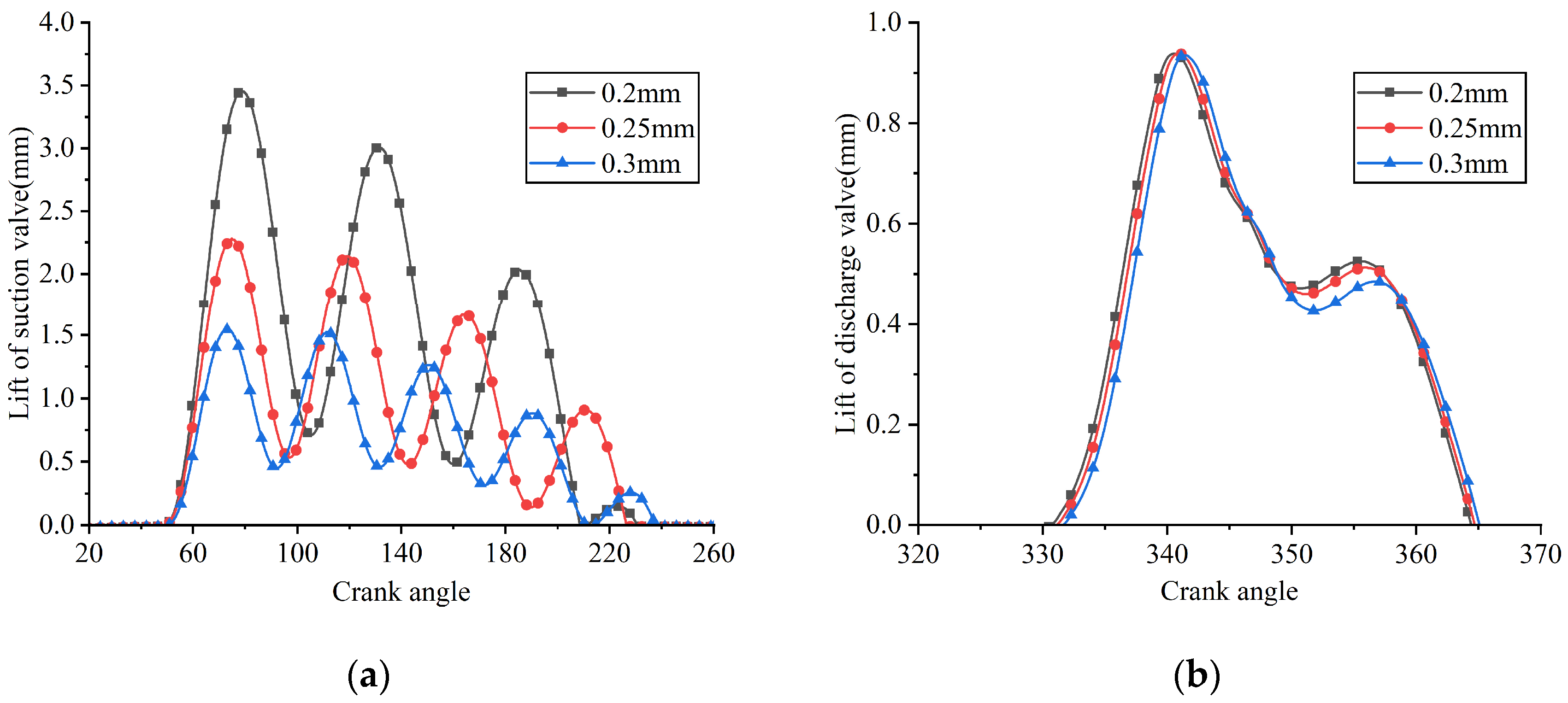

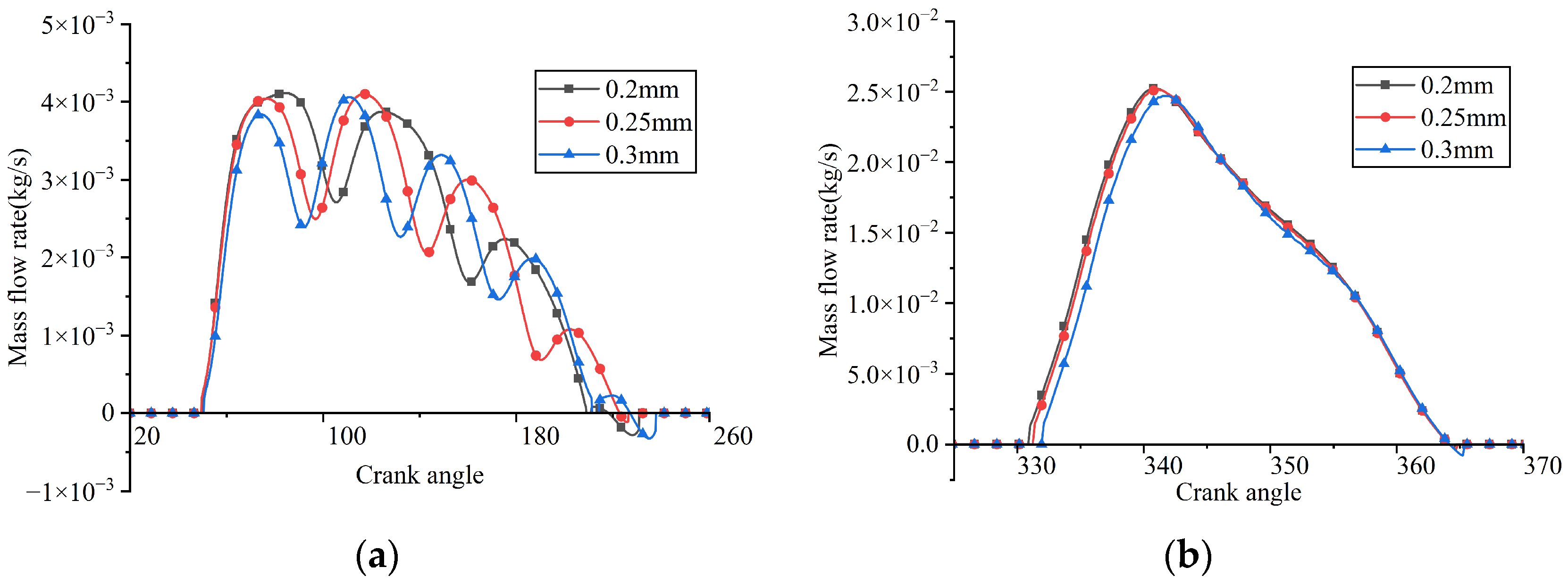

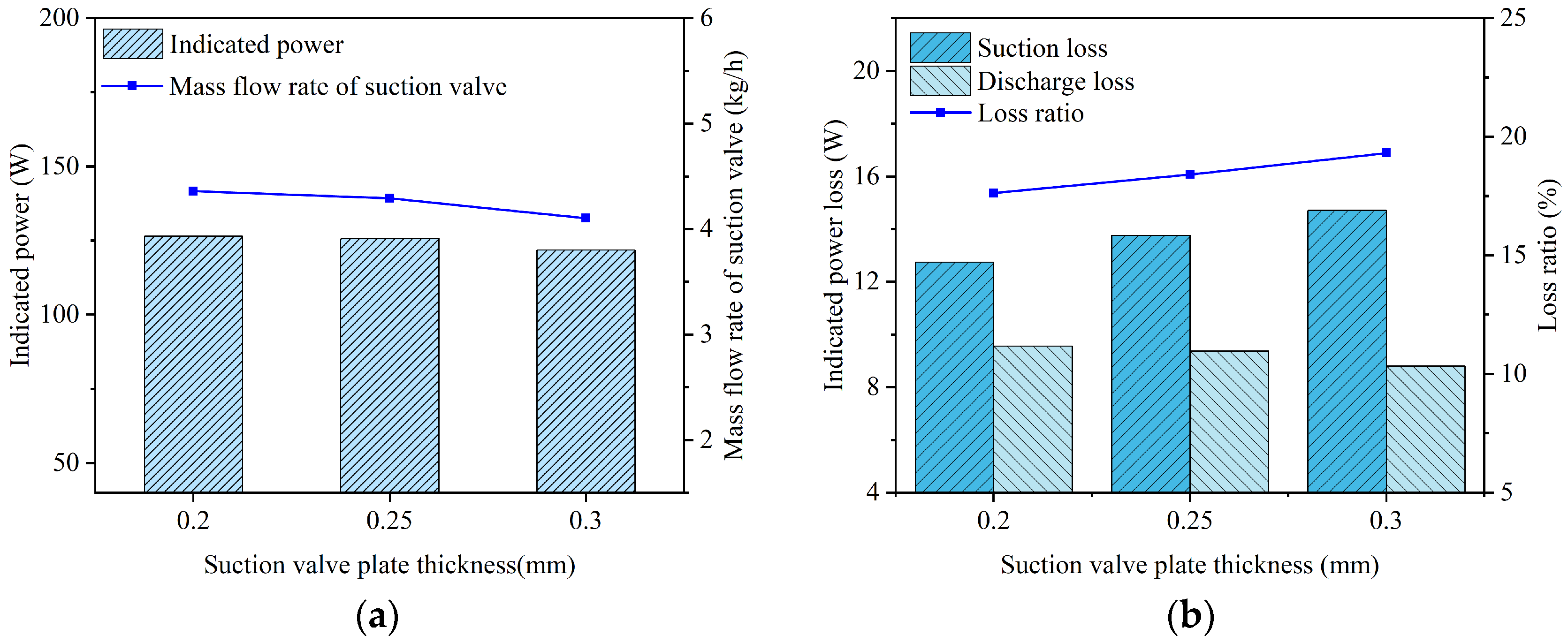

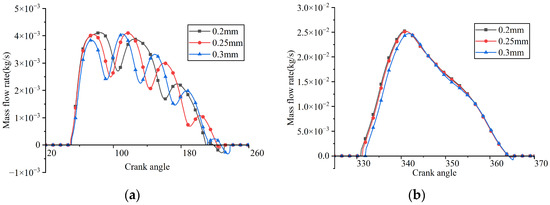

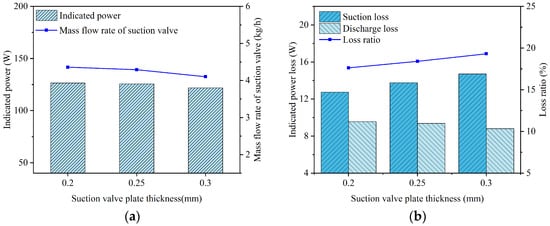

A series of FSI simulations were conducted with the thickness of the suction valve plate varied while other parameters remained constant. The simulated results, including the in-cylinder pressure, valve lifts, and instantaneous flow rates passing through the valve ports, are illustrated in Figure 32, Figure 33 and Figure 34, respectively. Additionally, the indicated power losses during the suction and discharge processes, as well as the total indicated power and average flow rate, were computed (see Figure 35).

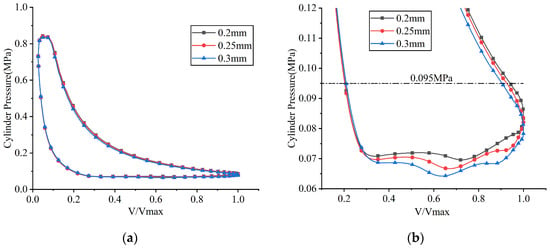

Figure 32.

p–V indicator diagrams under different suction valve plate thicknesses: (a) overall view; (b) partial enlarged view.

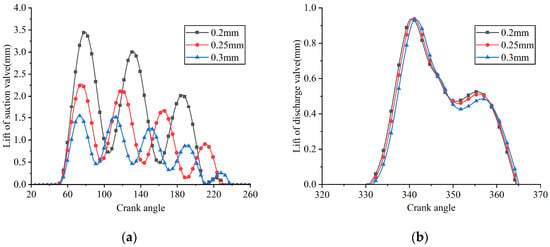

Figure 33.

Lifts of the suction and discharge reed valves under different suction valve plate thicknesses: (a) suction reed valve; (b) discharge reed valve.

Figure 34.

Instantaneous flow rates through the valve ports under different suction valve plate thicknesses: (a) suction reed valve; (b) discharge reed valve.

Figure 35.

Key performance parameters of the compressor and reed valves under different suction valve plate thicknesses: (a) indicated power and mass flow rate; (b) suction and discharge losses.

As the thickness of the suction valve plate increased, its stiffness correspondingly increased, resulting in a reduction in the maximum displacement at the center of the suction valve plate head. This caused a reduction in the mass flow rate through the valve port, an increase in suction loss, and a decrease in the average in-cylinder pressure during the suction process. When the thicknesses of the suction valve plate were 0.2 mm, 0.25 mm, and 0.3 mm, its maximum lifts were 3.453 mm, 2.275 mm, and 1.544 mm, respectively; the average flow rates passing through the suction valve port were 4.360 kg/h, 4.291 kg/h, and 4.102 kg/h, respectively; the indicated power losses during the suction process were 12.742 W, 13.759 W, and 14.700 W, respectively; and the average in-cylinder pressures during the suction process were 0.0720 MPa, 0.0697 MPa, and 0.0669 MPa, respectively.

When the thicknesses of the suction valve plate were 0.2 mm, 0.25 mm, and 0.3 mm, the corresponding opening angles of the discharge valve were predicted to be 330.849°, 331.203°, and 331.734°, respectively. Simultaneously, the indicated power losses during the discharge process were calculated as 9.547 W, 9.373 W, and 8.801 W, respectively. Additionally, the average in-cylinder pressures during the discharge process were observed to be 0.814 MPa, 0.813 MPa, and 0.810 MPa, respectively. The observed slight delay in the opening of the discharge valve was due to a marginally lower in-cylinder pressure present at the beginning of the compression stroke. The slight reduction in discharge loss was mainly caused by the decrease in mass flow rate.

The increase in suction loss with the thickness of the suction valve plate was accompanied by a reduced mass flow rate. This lower flow rate decreased both the compression work and discharge loss, resulting in a net reduction in the total indicated power. The indicated power of the compressor was calculated as 126.407 W at a suction valve plate thickness of 0.20 mm, 125.672 W at 0.25 mm, and 121.709 W at 0.30 mm.

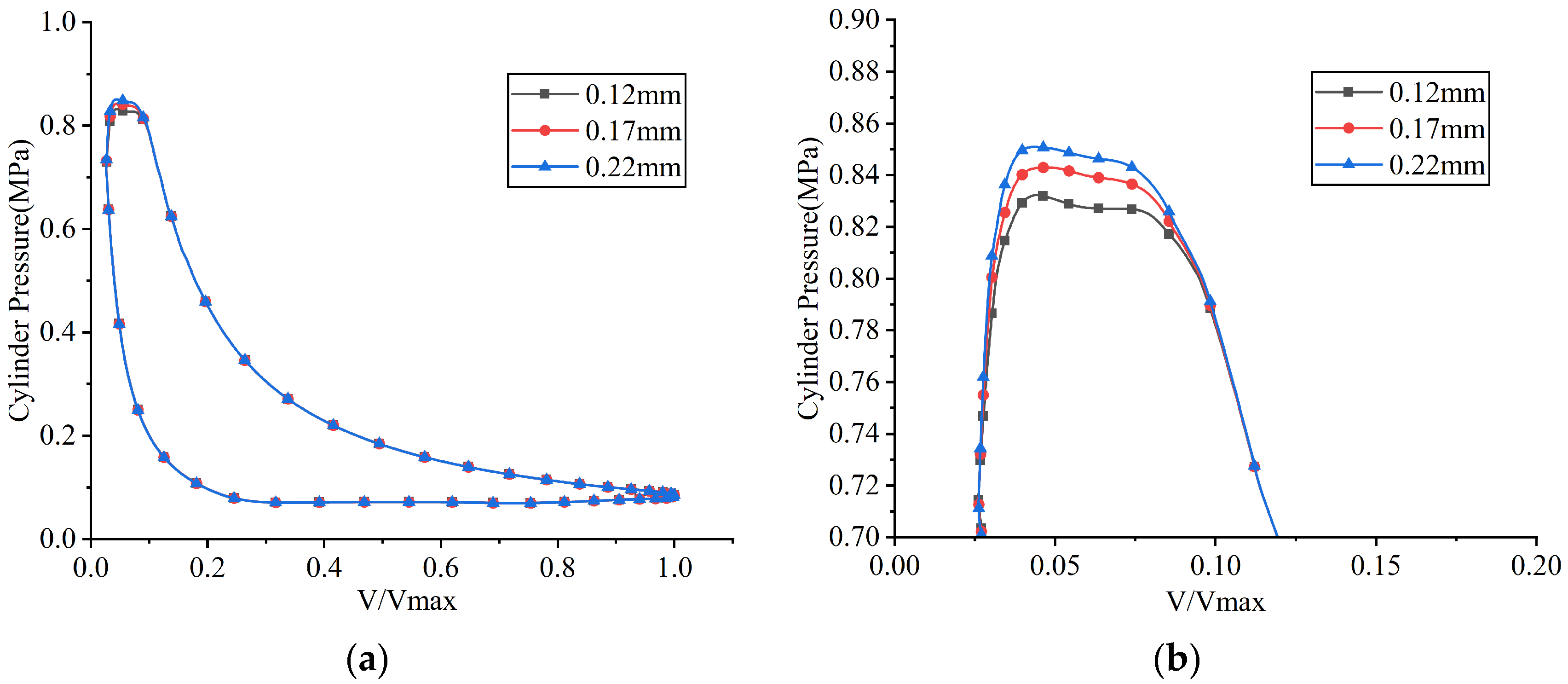

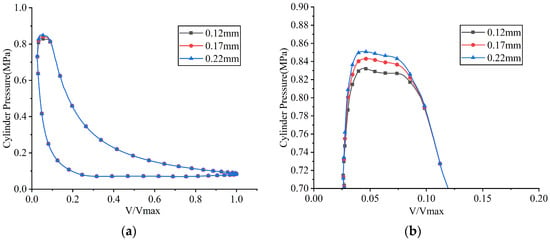

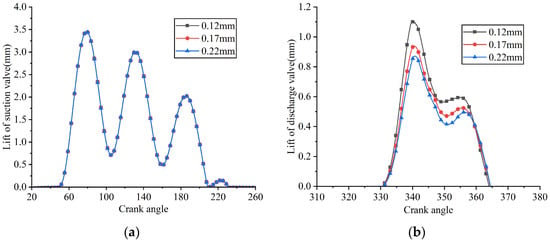

5.5. Discharge Valve Plate Thickness

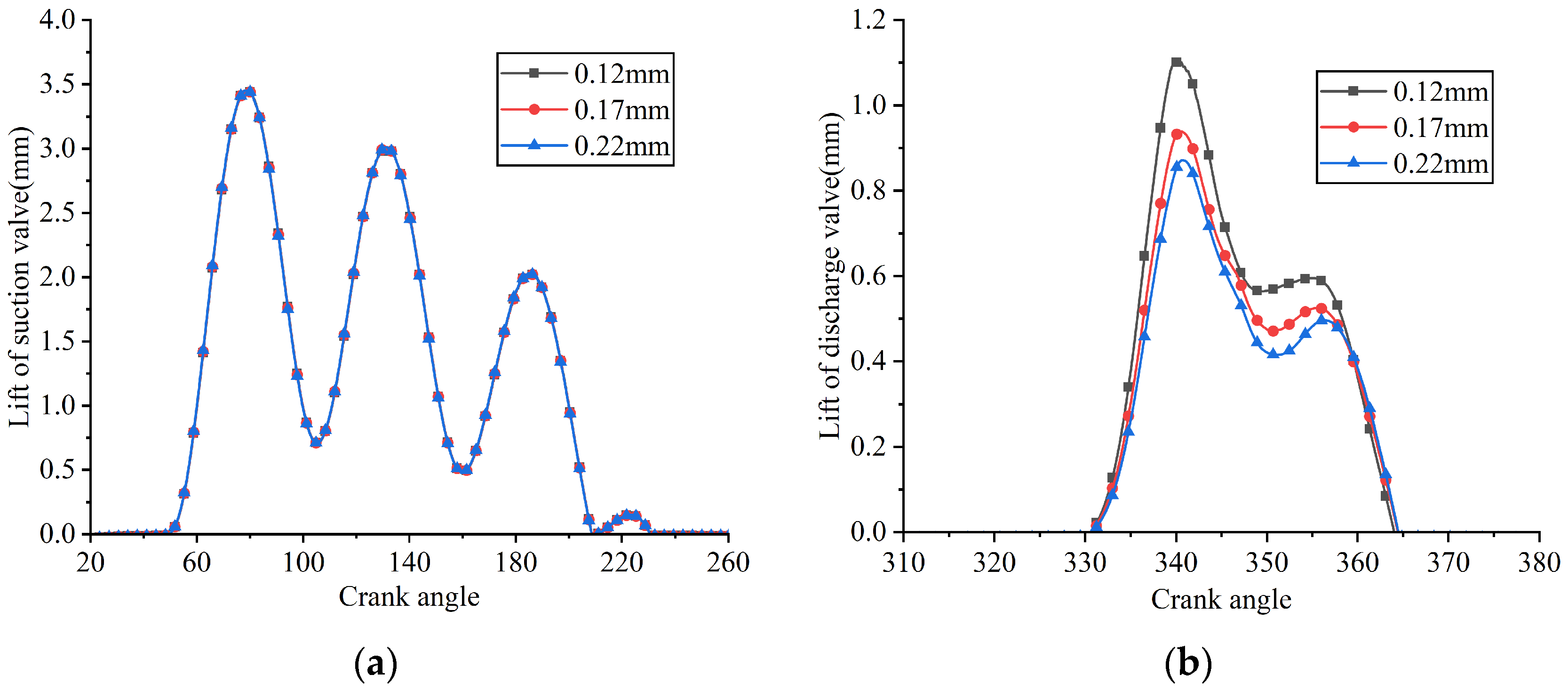

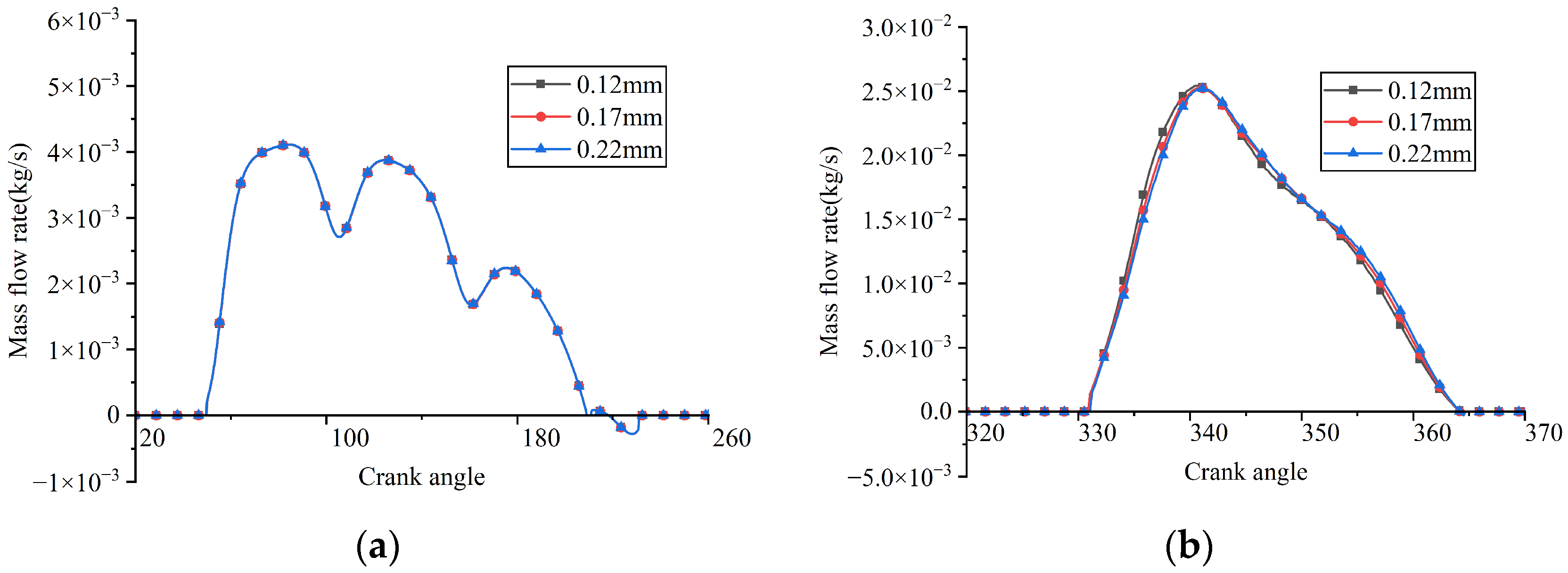

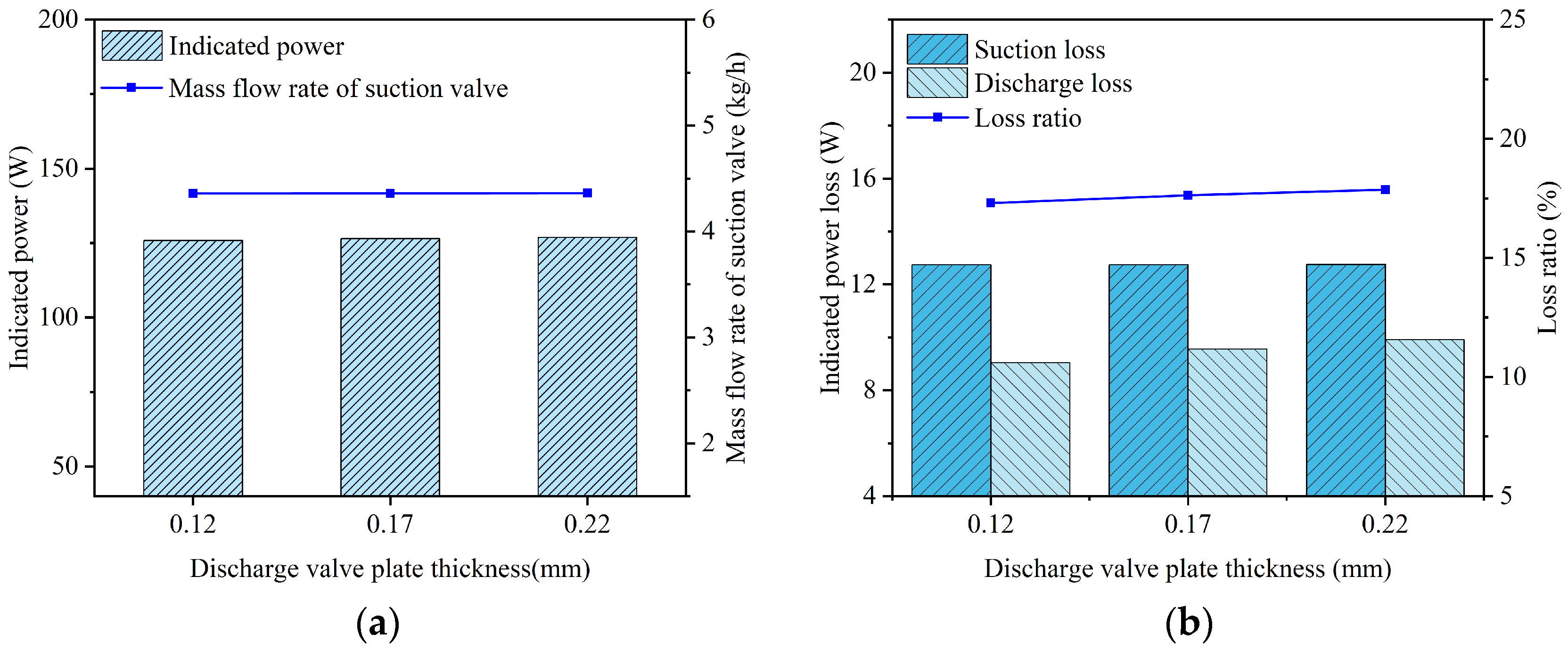

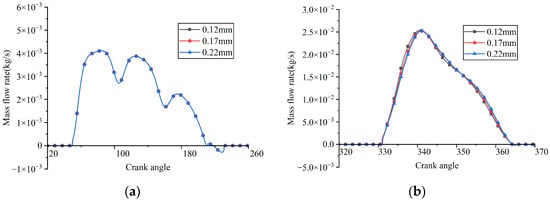

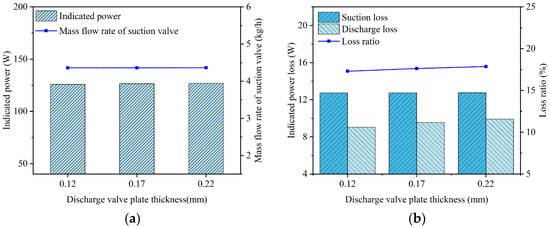

A series of FSI simulations were conducted with the thickness of the discharge valve plate varied while other parameters remained constant. The simulated results, including the in-cylinder pressure, valve lifts, and instantaneous flow rates passing through the valve ports, are illustrated in Figure 36, Figure 37 and Figure 38, respectively. Additionally, the indicated power losses during the suction and discharge processes, as well as the total indicated power and average flow rate, were computed (see Figure 39).

Figure 36.

p–V indicator diagrams under different discharge valve plate thicknesses: (a) overall view; (b) partial enlarged view.

Figure 37.

Lifts of the suction and discharge valve plates under different discharge valve plate thicknesses: (a) suction reed valve; (b) discharge reed valve.

Figure 38.

Instantaneous flow rates through the valve ports under different discharge valve plate thicknesses: (a) suction reed valve; (b) discharge reed valve.

Figure 39.

Key performance parameters of the compressor and reed valves under different discharge valve plate thicknesses: (a) indicated power and mass flow rate; (b) suction and discharge losses.

As the thickness of the discharge valve plate increased, its stiffness also rose, resulting in a decreased maximum displacement at the center of the discharge valve plate head. This led to higher discharge loss as well as lower average in-cylinder pressure during the discharge process. When the thicknesses of the discharge valve plate were 0.12 mm, 0.17 mm, and 0.22 mm, its maximum lifts were 1.102 mm, 0.939 mm, and 0.871 mm, respectively; the indicated power losses during the discharge process were 9.040 W, 9.547 W, and 9.905 W, respectively; and the average in-cylinder pressures during the discharge process were 0.807 MPa, 0.814 MPa, and 0.819 MPa, respectively.

As shown in Figure 37a, Figure 38a and Figure 39a, the suction valve plate motion, suction loss, and instantaneous flow rate remained nearly unchanged as the thickness of the discharge valve plate increased. When the thicknesses of the discharge valve plate were 0.12 mm, 0.17 mm, and 0.22 mm, the average flow rates passing through the suction valve port were 4.358 kg/h, 4.360 kg/h, and 4.362 kg/h, respectively; the indicated power losses during the suction process were 12.737 W, 12.742 W, and 12.751 W, respectively.

The indicated power of the compressor increased with the thickness of the discharge valve plate. The indicated power was calculated as 125.853 W at a discharge valve plate thickness of 0.12 mm, 126.407 W at 0.17 mm, and 126.822 W at 0.22 mm.

5.6. Limitations and Future Research

This study investigates the FSI characteristics of reed valves in a reciprocating compressor. However, certain aspects remain unaddressed: (1) the current FSI simulations assume adiabatic wall conditions and do not explicitly model conjugate heat transfer between solid components (e.g., cylinder, piston, and valve plates) and the working fluid; (2) gas leakage at sealing interfaces and assembly clearances is not accounted for in the present model. Future research will aim to incorporate these factors to improve the accuracy and broaden the applicability of the numerical model.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, the FSI characteristics of both the suction and discharge reed valves, as well as their influence on compressor performance, were investigated. Specifically, a 3D FSI simulation model was developed for a reciprocating refrigeration compressor, and experimental validation was conducted to verify its reliability. Subsequently, the FSI characteristics of the reed valves were analyzed based on numerical simulations. Furthermore, numerical investigations were performed to examine the effects of suction pressure, rotational speed, clearance volume ratio, suction valve plate thickness, and discharge valve plate thickness on the dynamic behavior of the reed valves and the overall performance of the reciprocating compressor. The following conclusions can be drawn:

First, the established 3D FSI model reliably predicted the operating characteristics of the reciprocating compressor. The simulated results for in-cylinder pressure, suction valve lift, and indicated power demonstrated strong agreement with the measured data, thereby validating the effectiveness of the proposed FSI model. This model serves as a reliable tool for the optimal design of reed valves and the determination of efficient operating parameters for the studied compressor.

Second, suction pressure and rotational speed, as two key operating parameters of the reciprocating refrigeration compressor, significantly affected its performance. An increase in either of these two parameters resulted in a higher mass flow rate; however, it also increased the maximum lifts of the suction and discharge valves, suction and discharge energy losses, and indicated power. In practical operation, it is recommended to keep these two parameters within optimal ranges to balance efficiency and valve reliability.

Third, the clearance volume ratio significantly impacted valve dynamics and the overall performance of the compressor. An increase in the clearance volume ratio delayed the opening of the suction and discharge valves, leading to a decrease in the mass flow rate. In compressor design, minimizing the clearance volume while ensuring manufacturability is suggested as an effective approach to enhance overall performance.

Fourth, variations in the thickness of the suction valve plate slightly affected the dynamics of the discharge reed valve, whereas variations in the thickness of the discharge valve plate exhibited a negligible impact on the dynamics of the suction valve plate. This weak coupling characteristic provides flexibility for the independent optimization of the suction and discharge reed valves. For valve design optimization, it enables engineers to individually tune the suction and discharge valves to achieve targeted improvements in efficiency and reliability, thereby streamlining the design process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z.; methodology, T.W.; software, T.W.; validation, Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.Z., H.X., F.F. and Q.Z.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. and H.X.; writing—review and editing, F.F.; visualization, H.X. and Q.Z.; supervision, Y.Z. and F.F.; project administration, Y.Z. and F.F.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. and F.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52206049), Joint Fund of the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. LZY23E060001), Quzhou Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant No. 2025K201), Central Government-Guided Local Science and Technology Development Fund Project (Grant No. 2025ZY01027), and Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Intelligent Manufacturing for Aerodynamic Equipment (Grant No. 2025E10033).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FSI | Fluid-Structure Interaction |

| DOF | Degree of Freedom |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| BDC | Bottom dead center |

| TDC | Top dead center |

References

- Zhong, H.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Gao, K.; Wu, J. Investigation of discharge valve in ultra-high-speed rotary compressors: An experimental and FSI simulation-based study. Int. J. Refrig. 2024, 168, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhong, Z.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, M.; Lu, X. Research on Internal Instability Characteristics of Centrifugal Impeller Based on Dynamic Mode Decomposition. Fluids 2025, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, J.M.; Guerrato, D.; Stosic, N.; Yan, Y. Suction Flow Measurements in a Twin-Screw Compressor. Fluids 2025, 10, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willich, C.; White, A.J. Heat transfer losses in reciprocating compressors with valve actuation for energy storage applications. J. Energy Storage 2017, 14, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Guo, T.; Peng, C.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, L.; He, Z. FSI simulation of the suction valve on the piston for reciprocating compressors. Int. J. Refrig. 2022, 137, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costagliola, M. Dynamics of a Reed Type Valve. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1949. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/12752 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Prakash, R.; Singh, R. Mathematical Modeling and Simulation of Refrigerating Compressors. In Proceedings of the 1974 International Compressor Engineering Conference, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 10–12 July 1974; Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/icec/132 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Rigola Serrano, J. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Validation of Hermetic Reciprocating Compressors. Integration in Vapour Compression Refrigerating Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Terrassa, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; He, Z.; Guo, J.; Peng, X. Investigation of the Thermodynamic Process of the Refrigerator Compressor Based on the m-θ Diagram. Energies 2017, 10, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, G.; Wang, F.; Mi, X.; Gao, G. Dynamic modeling and analysis of compressor reed valve based on movement characteristics. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 150, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Wang, S.; Park, S.; Ryu, K.; La, J. Valve Dynamic Analysis of a Hermetic Reciprocating Compressor. In Proceedings of the 18th International Compressor Engineering Conference at Purdue, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 17–20 July 2006; Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/icec/1805 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Wang, T.; Guo, Y.; He, Z.; Peng, X. Investigation on the delayed closure of the suction valve in the refrigerator compressor by FSI modeling. Int. J. Refrig. 2018, 91, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowinski, D.; Sadique, J.; Oliveira, S.; Real, M. Modeling a Reciprocating Compressor Using a Two-Way Coupled Fluid and Solid Solver with Automatic Grid Generation and Adaptive Mesh Refinement. In Proceedings of the 24th International Compressor Engineering Conference at Purdue, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 9–12 July 2018; Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/icec/2632 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Bacak, A.; Pınarbaşı, A.; Dalkılıç, A.S. A 3-D FSI simulation for the performance prediction and valve dynamic analysis of a hermetic reciprocating compressor. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 150, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, I.; Naseri, A.; Rigola, J.; Pérez-Segarra, C.D.; Oliva, A. Detailed prediction of fluid-solid coupled phenomena of turbulent flow through reed valves. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 604, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S. Research on Flow Induced Vibration and Flow Induced Noise During the Starting Process of a Refrigerator Piston Compressor. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science & Technology, Wuhan, China, 2023. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, S.; Nozaki, T.; Akizawa, T. Analysis of Dynamic Behavior of Suction Valve Using Strain Gauge in Reciprocating Compressor. In Proceedings of the 20th International Compressor Engineering Conference at Purdue, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 12–15 July 2010; Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/icec/1979 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Zhang, W.; Ji, L.; Xing, Z.; Peng, X. Investigation on the Suction Reed Valve Motion with Sticky Force in a Refrigerator Compressor. Energies 2018, 11, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Jian, Z.; Wang, T.; Li, D.; Peng, X. Investigation on the variation of pressure in the cylinder of the refrigerator compressor based on FSI model. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 232, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, M.A.; Pereira, E.A.G. Using PV Diagram Synchronized with the Valve Functioning to Increase the Efficiency on the Reciprocating Hermetic Compressors. In Proceedings of the 20th International Compressor Engineering Conference at Purdue, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 12–15 July 2010; Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/icec/1966 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Wang, Y. Research on Dynamic Characteristics and Stress Fatigue of Small Hermetic Compressor Valves. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China, 2020. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buligan, G.; Paone, N.; Revel, G.M.; Tomasini, E.P. Valve Lift Measurement by Optical Techniques in Compressors. In Proceedings of the 2002 International Compressor Engineering Conference at Purdue, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 16–19 July 2002; Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/icec/1556 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Nagy, D.; Almbauer, R.A.; Lang, W.; Burgstaller, A. Valve Lift Measurement for the Validation of a Compressor Simulation Model. In Proceedings of the 19th International Compressor Engineering Conference at Purdue, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 14–17 July 2008; Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/icec/1916 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; He, Z.; Sun, J.; Wang, T.; Liu, C. Investigation on Dynamic Characteristics of the Reed Valve in Compressors Based on Fluid-Structure Interaction Method. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, B.; Peng, X. Investigation on dynamic stress of the discharge valve in the transcritical CO2 compressor. Renew. Energy 2024, 220, 119589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Pan, S.; Feng, Q.; Yu, X.; Wang, Z. Fluid–structure interaction model of dynamic behavior of the discharge valve in a rotary compressor. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2015, 229, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yue, X.; Ba, D.; Che, S. Fluid–solid coupling numerical simulation for the performance prediction and valve dynamic analysis of a rotary compressor. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2019, 233, 6928–6938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kwon, M.; Heo, H. Design optimization for discharge valve in a rotary compressor. In Proceedings of the 25th International Compressor Engineering Conference at Purdue, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 24–28 May 2021; Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/icec/2651 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Xie, J.; Zeng, W.; Pan, X.; Chen, J.; Ye, J. FSI investigation on the discharge valve lift in a R32 rotary compressor and its verification. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 61, 105108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Pan, X.; Chen, J.; Xie, J. Investigation on a R32 rotary compressor with vapor injection by supplementary valve based on FSI simulation. Int. J. Refrig. 2026, 181, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.