Abstract

Mucilage extracted from cladodes of Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. has attracted growing interest as a natural food additive due to its gelling and nutritional properties. In this study, the chemical characteristics of Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage were comparatively evaluated against commercial pectin, with particular emphasis on volatile compounds, mineral composition, and monosaccharide profiles by 13C-NMR spectroscopic analysis. The volatile components were analysed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), revealing distinct aromatic profiles between the two matrices, with the mucilage showing a significant presence of methoxypyrazines, but not detected in the powdered pectin studied. These compounds could negatively affect the sensory perception of mucilage. Mineral analysis demonstrated significantly higher levels of calcium, magnesium, and potassium, supporting its potential contribution to nutritional enrichment. The spectroscopic analysis, used to identify monosaccharide composition of polysaccharide chains, highlighted the presence of arabinose, galactose, glucose, and rhamnose in the mucilage sample compared to the predominantly glucose/galacturonic acid-based structure of pectin. Overall, the results indicate that Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage represents a promising alternative to pectin, offering unique chemical properties that may expand its application as a multifunctional, natural food additive.

1. Introduction

1.1. Opuntia ficus-indica Mucilage: Source and Potential

Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. (OPI), known as the prickly pear, is cultivated in arid and semi-arid regions due to its adaptability and high biomass productivity [1]. Cladodes are abundant and a potential source of mucilage biopolymers, a complex heteropolysaccharide that has attracted growing interest for food, pharmaceutical, and biotechnological applications. The functional potential of OPI mucilage has been associated with its water-binding capacity, emulsifying properties and rheological behaviour, which are often compared to those of commercial hydrocolloids such as pectin [2]. Moreover, the production potential of OPI cladode gel is very high given the extent and widespread distribution of the cultivated and wild species [3]. Chemically, OPI mucilage is characterized by a high content of polysaccharides composed of galacturonic acid, arabinose, galactose, rhamnose, and xylose, arranged in branched structures [4] that differ significantly from the backbone structure of pectin [5]. The technological behaviour of OPI cladode mucilage is strongly governed by its heterogeneous polysaccharide composition, where the lower galacturonic acid content and higher arabinogalactan branching, compared to commercial pectins, favour enhanced water-holding capacity and emulsifying properties rather than strong gel formation [2,6,7].

1.2. Pectin as a Reference Gelling Polymer

Comparative studies with pectin, one of the most widely used polysaccharides in the food industry, could be interesting to evaluate the potential technological advantages of mucilage extracts. In fact, the pectin market is expected to grow from USD 1.07 billion in 2025 to USD 1.13 billion in 2026 and is forecast to reach USD 1.52 billion by 2031 at 6.05% CAGR over 2026–2031, while demand surges for recognizable ingredients [8,9]. The uronic acids concentration and degree of esterification in commercial pectins correlate positively with elastic gel strength and pH- and ion-dependent network formation, highlighting how subtle differences in polysaccharide structure dictate their functional performance as food additives [5,10,11]. Beyond polysaccharide structure, the presence of minerals, proteins, and minor lipid fractions plays a critical role in determining the functional performance of OPI mucilage compared to commercial pectins. Divalent cations such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ naturally associated with mucilage can promote weak ionic cross-linking within uronic acid regions, influencing viscosity, thermal stability, and gel-like behaviour, albeit less efficiently than purified low-methoxyl pectins [2,5]. These differences influence not only functional properties, but also interactions with minerals, volatile compounds, and low molecular weight sugars, which remain less explored than classic plant hydrocolloids.

1.3. Rationale and Novelty of the Study

Although numerous studies have focused on the extraction yield, rheological behaviour, and centesimal composition of OPI mucilage [4,12], data on mineral composition and detailed sugar compositions [13,14] are less available, while studies on volatile profiles are completely absent, despite their relevance for aromatic interactions. In a previous study [15] mucilage from OPI cladodes and pectins was compared, by considering their gelling and rheological properties. The results highlighted the potential applications of OPI cladode mucilage solutions as gelling agents in industrial food processes. Therefore, the aim of this study is to characterize the chemical properties of OPI mucilage, emphasizing its volatile composition, its sugar profiles by 13C-NMR spectroscopy, and the mineral composition. A comparative analysis with commercial pectin is also conducted to highlight similarities and differences in chemical composition, contributing to a deeper understanding of the potential of OPI mucilage as an alternative or complementary hydrocolloid for food applications.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Centesimal Composition

The water content of the mucilage after freeze-drying was 2.7%, while in commercial pectin it was 10.6% (Table 1). The titratable acidity values (56 mg/g), measured in mucilage extracted from one-year-old cladodes, were consistent with those found elsewhere [16], by evaluating the variations in titratable acidity of 10 varieties of “nopalito” (edible cladodes of flat-stemmed prickly cacti). Generally, younger cladodes have lower acid levels then older cladodes. The pectin with a high methoxyl (HM) content, (esterification degree ≥ 50) here used, had an acidity value of about 22 mg/g. In HM pectins the free acidity values are typically 44.8–83.6 mg equivalents of citric acid/g, depending on source and extraction conditions [17]. Mucilage’s protein fraction makes it a dual-function hydrocolloid, both thickener and emulsifier, meaning it may reduce dependency on external surfactants in products such as dressings or beverages [18]. The protein content in OPI mucilage was found to be 0.61% on a dry basis, which is lower than that reported by other authors (0.82 to 6.8%) in a similar sample [19,20]. Different chemical compositions of cladodes, including mucilage proteins, can be explained by soil type, growing season, plant age, cultivar used, cladode age, mucilage extraction and purification conditions. Moreover, OPI mucilage contains protein–polysaccharide complexes that can be partially removed or retained depending on extraction conditions [20]. The protein content of around 1.2% in commercial pectin is consistent with its nature as a highly purified polysaccharide, since the extraction and purification of pectin aims to isolate high molecular weight polysaccharides. The fat content of the mucilage of freeze-dried cladodes was 12.5%, a value comparable to that reported elsewhere [21] (<2% fat on fresh weight), with lipid content generally decreasing as cladodes mature. Fat levels are usually higher in freeze-dried samples, which is the technique used here [22]. Residual lipids and proteins in cactus mucilage enhance interfacial activity, contributing to improved emulsifying capacity and emulsion stability through protein–polysaccharide and lipid–polysaccharide interactions, a feature largely absent in highly purified commercial pectins [6,10]. The lipid content of the commercial pectin was about 0.4% (Table 1). These latter are highly purified polysaccharide products with negligible lipid content because extraction and purification procedures (acid extraction followed by alcohol precipitation) effectively remove non-polysaccharide components, including lipids. The presence of lipid within mucilage can influence functional properties such as emulsification and interfacial behaviour. The low lipid content in pectin means that their emulsifying and interfacial properties derive exclusively from their polysaccharide structure and not from effects associated with lipids.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the OPI mucilage and pectin samples.

2.2. Phenols and DPPH

The results for total polyphenol content confirm that mucilage extracted from OPI cladodes can serve as a valuable source of antioxidant compounds with potential health benefits [14,18]. In the present study, the total polyphenol content (TPC) was approximately 19.40 mg GAE (gallic acid equivalent)/g (Table 1). These values are consistent with those reported elsewhere [21], where a TPC of about 2.6 mg GAE/g fresh weight in prickly pear cladodes was found [23]. Several studies have reported significantly lower TPC values, such as 0.32 mg GAE/g dry matter in cladode flour [24], and TPC of 5.7 and 3.8 mg GAE/g dry matter in the OPI cultivars “Milpa” and “Atlixco”, respectively [25]. Thermal processing of OPI cladodes can markedly influence the chemical characteristics of the resulting extracts. Freeze-dried extracts obtained using ethanol and methanol exhibited the highest TPC values (11.6 mg GAE/g), likely due to the greater polarity of these solvents, which enhances the release of hydrolysable phenols [26]. Moreover, freeze-dried extracts retained superior antioxidant and antibacterial properties, making them particularly suitable for applications in functional foods and nutraceutical formulations [26]. TPC content in pectin (2.1 mg/g) was slightly lower than reported elsewhere [27]. In extracted apple pectin, a TPC content ranging from 0.59 to 2.41 mg GAE/g has been reported, depending on the extraction conditions and source [28,29]. The results of the TPC tests were supplemented by those of the DPPH test, used to evaluate the ability of plant extracts and polysaccharides to neutralise free radicals (antioxidants). OPI mucilage shows 27.8% scavenging activity, which is substantially higher than 0.65% for the commercial pectin. OPI mucilage samples reported in other studies have shown a DPPH antiradical power of approximately 35.5% [30], similar to our findings. The higher antioxidant activity found in OPI mucilage suggests it could contribute functional benefits, such as delaying lipid oxidation or protecting sensitive components in food matrices.

2.3. Ash and Minerals

The total ash in OPI mucilage (20.9%) was comparable to that reported elsewhere [31]. As with any other plant, the mineral content of OPI cladodes reflects the characteristics of the soil in which they are grown. The high ash values in the cladodes may result from the high soil salinity and mineral availability. The ash content can be considered a useful property for hydrocolloids, as it defines the degree of mineral interaction in the structure and promotes the functional properties of polysaccharides [32]. The ash was investigated in depth by analysing the main minerals present in it and comparing them with those of pectin (Table 2). Data show that mucilage has a high mineral content, particularly Ca (3130 mg/100 g), K (2940 mg/100 g) and Mg (2100 mg/100 g); these results are consistent with previous studies [33]. The minerals present in mucilage are an integral part of the structural and functional characteristics of the biopolymer. Divalent cations such as calcium, for example, can interact with polysaccharide chains, forming ordered ionic cross-links that influence the rheological behaviour of the mucilage. Moreover, calcium and magnesium, when bound in mucilage, contribute to its dietary value, particularly in functional foods and nutraceutical formulations [34]. Furthermore, the high ash and mineral contents in mucilage, particularly calcium, magnesium, and potassium ions, reflect its physiological role in the cladodes as a water-retention and ion-regulation matrix. The minerals present in the mucilage in smaller quantities include, in descending order, Na, P, Fe, and Zn, with values ranging from 11.4 to 2.1 mg/100 g (Table 2). The ash content in pectin is below 5%, consistent with its higher degree of purification. In the pectin samples analysed, the main minerals present are K and Ca, with approximately 200 mg/100 g, followed by Na and P (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mineral composition of Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage and pectin (mg/100 g).

2.4. Monosaccharide Compositions by 13C-NMR Analyses

Chemical characterization of mucilage involves the identification of its complex polysaccharide structure, dominated by sugars such as arabinose, galactose, rhamnose, xylose, fucose, and uronic acids (especially glucuronic acid) [35], as well as proteins, minerals, and other phytochemical compounds. By using techniques such as FT-IR, NMR, chromatography, and elemental analysis it is possible to understand its function as a hydrocolloid. Key aspects include monosaccharide composition, presence of specific functional groups (hydroxyl, carboxyl), molecular weight, and thermal/rheological properties [36]. In this work, the monosaccharide compositions of OPI mucilage and pectin were determined after classical acid hydrolysis [37]. The two solid residues obtained after hydrolysis were dissolved in deuterated water (D2O), and the monosaccharide units were identified and quantified by studying specific signals present in the 13C-NMR spectra. In particular, the peaks present between 90 and 100 ppm, the typical area of anomeric carbons; the C1 carbon in aldose sugars (or C2 in ketoses) that becomes a new chiral centre upon cyclization; and those of the carboxyl function of uronic acids, situated between 175 and 180 ppm, were identified and studied.

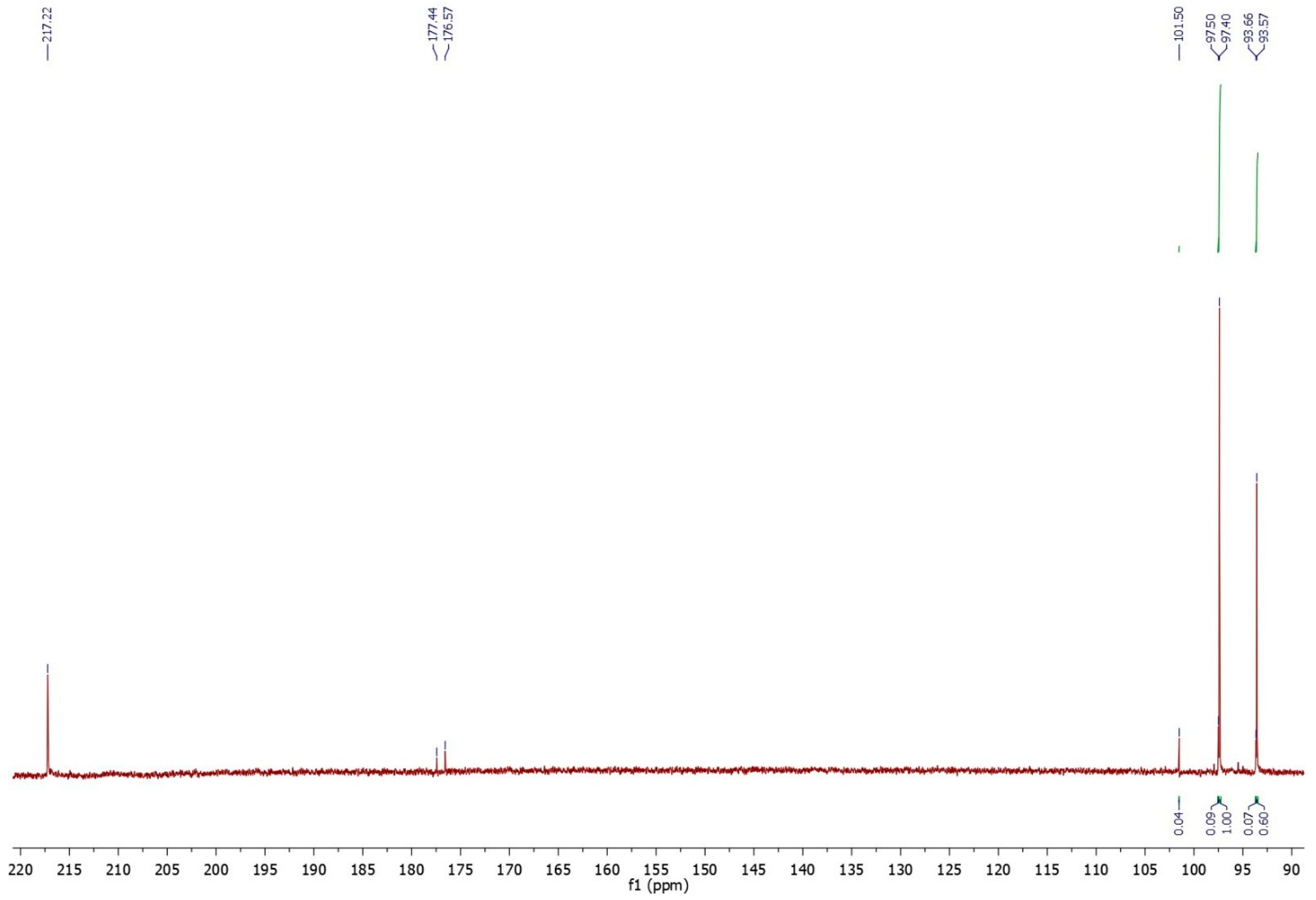

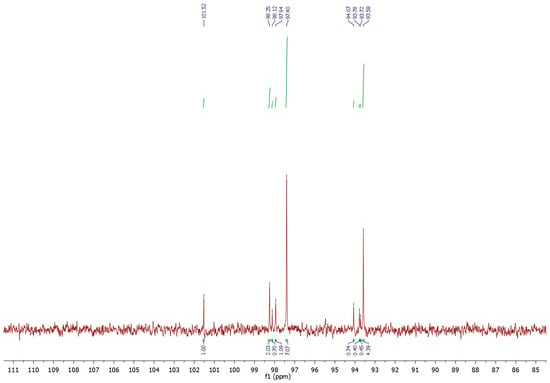

By comparing these signals with the literature data [38] the anomeric signals characteristic of the individual sugars can be identified, and subsequently the entire sugar portion present in both analysed samples. As can be observed in the 13C-NMR pectin spectrum (Figure 1) obtained after chemical hydrolysation, four well-separated anomeric signals (93.58, 93.66, 97.40, and 97.50 ppm) were identified and assigned to the anomers (α and β) of glucose and glucuronic acid. The presence of β- and α-glucuronic acids is also confirmed by the signals at 176.57 and 177.44 ppm relating to the carboxylic functional groups. Another peak was present at 101.50 ppm and is related to the anomeric carbon of unreduced and unhydrolyzed portion of maltose [39]. By integrating the peak areas of the anomeric carbons and comparing them to each other, the relative percentage of monomeric sugars present in the pectin sample was quantified (Table 3). The main sugar identified was glucose (88.89%); glucuronic acids were present in small amounts (8.89%), followed by smaller quantities (2.22%) of maltose non-reducing units.

Figure 1.

13C-NMR spectrum in D2O of the anomeric carbons and carboxylic functional groups of the sugar units composing the pectin.

Table 3.

Sugar unit composing the pectin and values of the anomeric carbons.

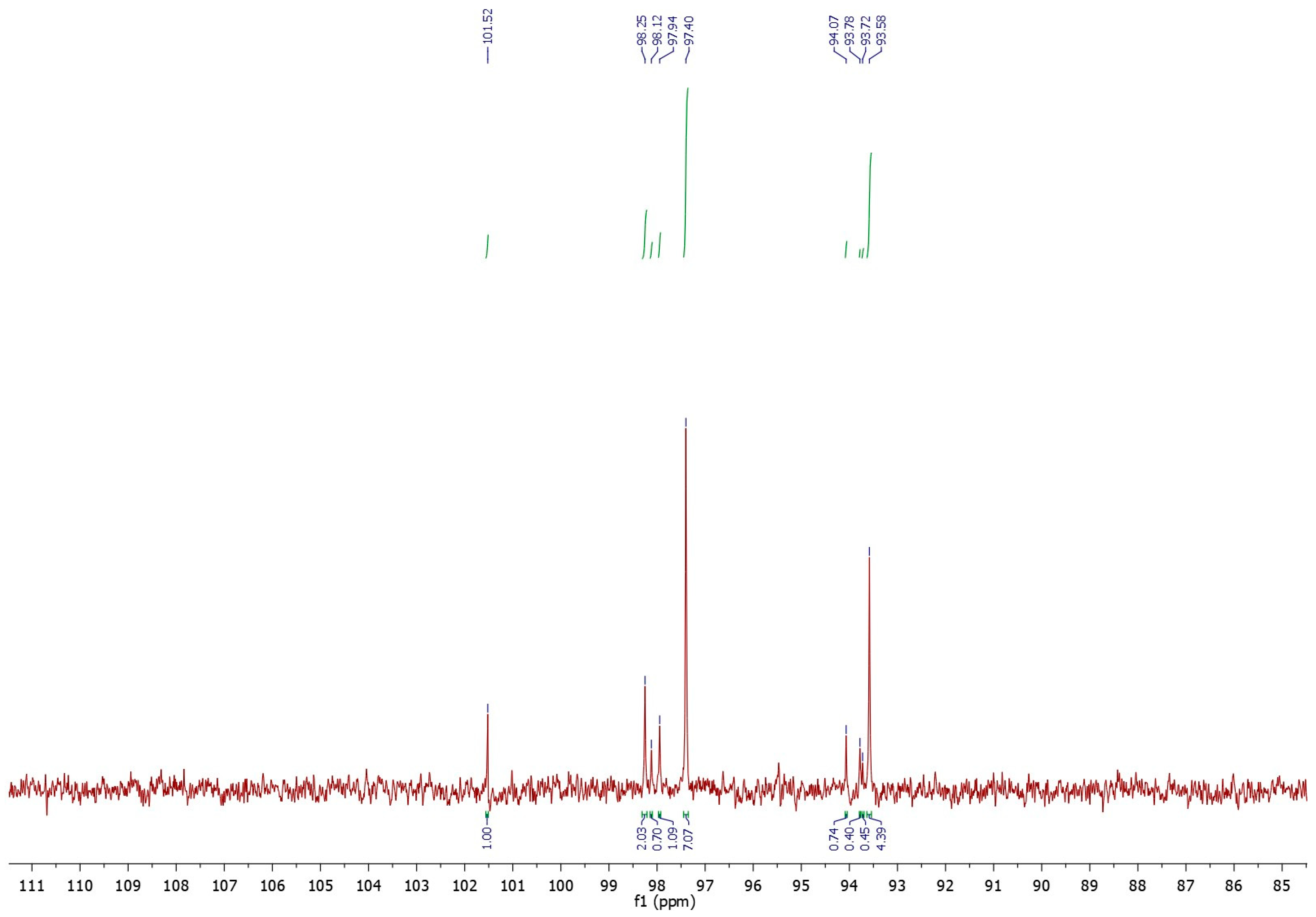

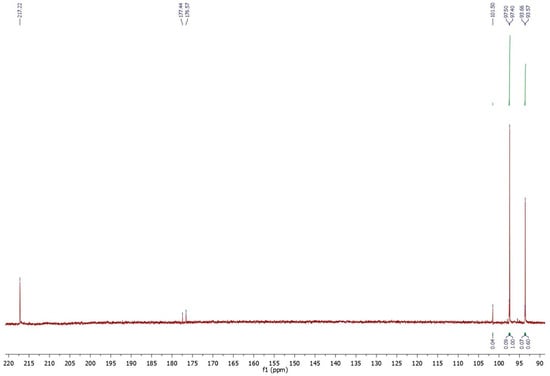

The same experiment was conducted for the OPI mucilage. From the analysis of the carbon spectrum (Figure 2) it emerged that, also in this case, the amount of glucose anomers contribute significantly (64.13%) to the total chemical composition of the sample (Table 4). Unlike pectin, mucilage exhibited characteristic peaks of the two α- and β-isomers of arabinose (15.50%), xylose (6.43%), and galactose (8.34%). Finally, a minor presence of non-reduced maltose (5.60%) was detected in OPI mucilage.

Figure 2.

13C-NMR spectrum in D2O of the anomeric carbons of the sugar units composing the OPI mucilage.

Table 4.

Sugars composition of the Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage and values of the anomeric carbons.

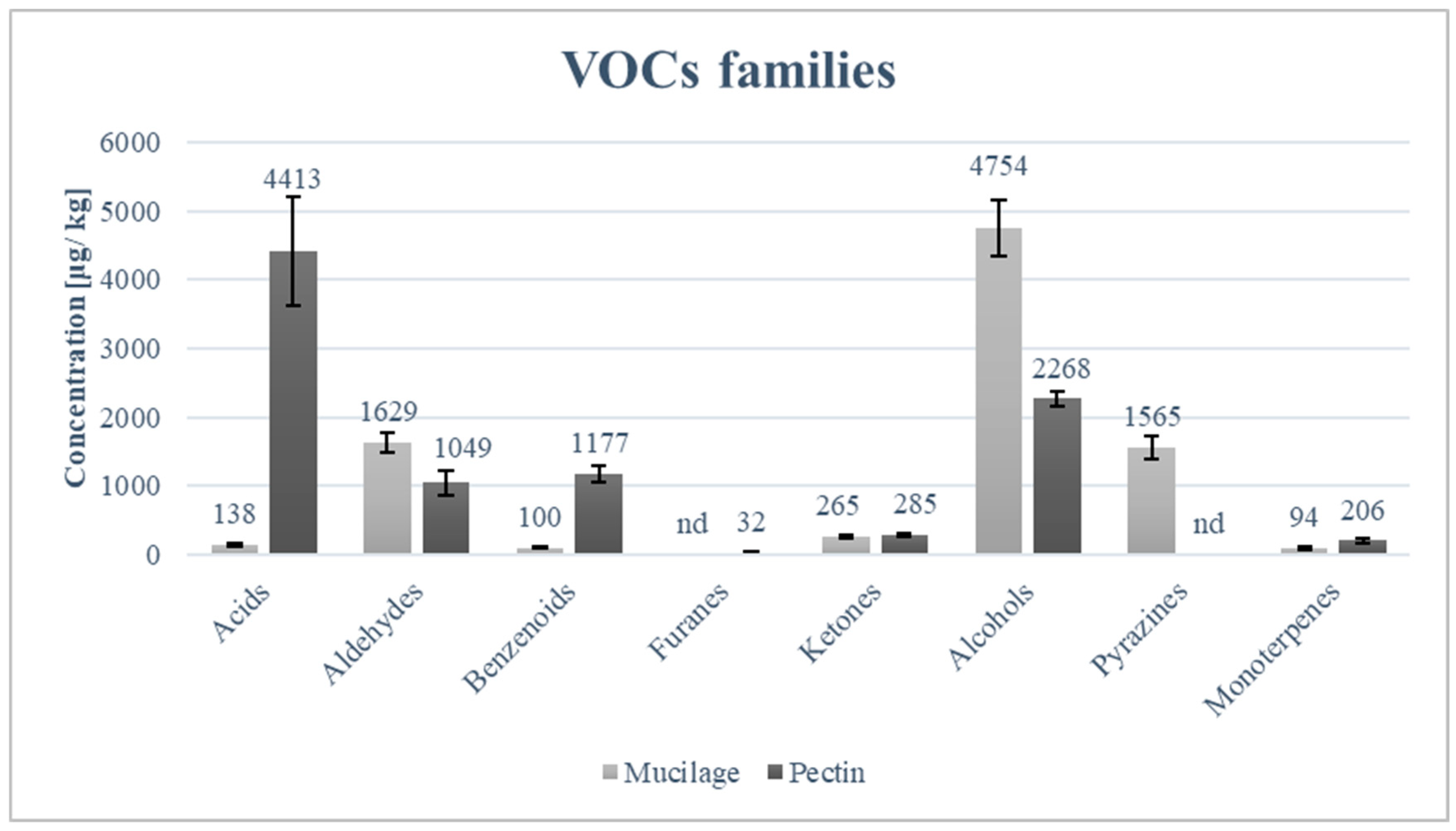

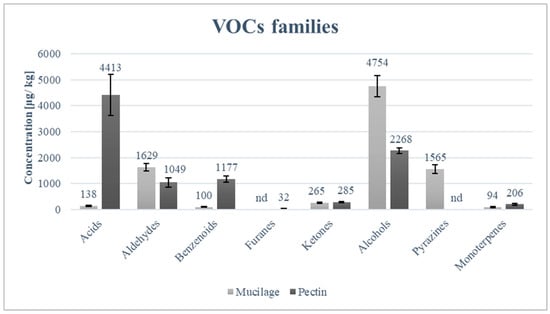

2.5. Volatile Compounds

The volatile compound profiles of freeze-dried mucilage and that of powdered pectin are markedly different, as can be seen in Table 5. The most technologically relevant differences are those related to methoxypyrazines, which are highly abundant in freeze-dried mucilage but were not detected in the studied powdered pectin. The three methoxypyrazines identified (3-isopropyl-2-methoxypyrazine, 3-sec-butyl-2-methoxypyrazine, and 3-isobutyl-2-methoxypyrazine) are potent volatile compounds with olfactory descriptors associated with green bell pepper and unripe vegetable notes [40,41]. Their behaviour varies depending on the matrix and their consequent ionization, as they can form methoxypyrazinium cations more abundantly at low pH. The protonated forms are less volatile in polar media than the neutral forms; consequently, these compounds are more perceptible in polar matrices with high pH [42]. The main ‘negative effect’ of these molecules is sensory discomfort, which translates into aversion or rejection of products due to their unpleasant smell/taste. Therefore, the use of mucilage from cladodes in food formulations would require their total or partial removal. Most strategies aim to reduce their presence below the sensory threshold or to mask their perception; however, since these compounds have extremely low olfactory thresholds (ppt-ppb) and are chemically stable, their complete removal is difficult. Methoxypyrazines responsible for green/off-flavours in OPI cladode mucilage can be effectively reduced through thermal treatments (blanching or mild heating) combined with aqueous–alcoholic extraction, which promote volatilization and diffusion of these low-molecular-weight aroma compounds without significantly degrading polysaccharide functionality [43,44]. Alternatively, adsorptive approaches (e.g., activated carbon or food-grade resins) have been reported to decrease methoxypyrazine perception by selective binding while simultaneously improving sensory acceptance of plant-derived hydrocolloids [45]. Acids were significantly more concentrated in pectin than in mucilage (Table 5). Aldehydes showed a variable situation: compounds such as (E)-2-hexenal were present at significantly higher concentrations in mucilage, whereas hexanal and octanal were more abundant in pectin. Nevertheless, the total aldehyde concentration was higher in mucilage (Figure 3). Benzenoid compounds were significantly more concentrated in pectin, driven by higher levels of p-cymene and benzaldehyde, while furans were detected exclusively in pectin. Ketones did not differ significantly in total concentration between the two matrices, although pronounced differences were observed at the level of individual compounds, with several ketones occurring only in one of the two fractions. Alcohols represented the most abundant class in both matrices and were significantly higher in mucilage, mainly due to elevated concentrations of C6 alcohols such as (E)-2-hexen-1-ol and 1-hexanol. In contrast, pectin showed higher concentrations of alcohols such as 3,5-octadien-2-ol, 3,5-octadien-2-ol, and 1-octanol. Monoterpenes were detected in both matrices but were overall more concentrated in pectin, with significantly higher levels of α-terpineol and eucalyptol.

Table 5.

Volatile compounds of mucilage and pectin samples.

Figure 3.

Main classes of volatile compounds in mucilage and pectin samples.

3. Conclusions

The comparative evaluation of mucilage extracted from OPI cladodes and commercial pectin highlighted marked differences in their chemical profiles, with relevant implications for their potential use as food additives. Volatile compound analysis revealed the presence of methoxypyrazines in mucilage, which negatively affected its sensory acceptance due to characteristic green and earthy notes, representing a potential limitation for direct application in aroma-sensitive food systems. In contrast, pectin exhibited a more neutral volatile profile. Mineral analysis demonstrated that mucilage contained significantly higher levels of nutritionally relevant elements, particularly calcium, magnesium, and potassium, supporting its potential role as a functional ingredient with added nutritional value. Monosaccharide characterization by NMR spectroscopy evidenced substantial structural differences between the two matrices: the main sugar present in pectin was glucose (88.89%), while in OPI mucilage the glucose anomers contribute to about (64.13%) of the total chemical composition of the sample. Unlike pectin, OPI mucilage exhibited characteristic peaks of the two α- and β-isomers of arabinose (15.50%), xylose (6.43%), and galactose (8.34%). These compositional features are likely responsible for the distinct functional and textural properties observed. Overall, while sensory challenges related to volatile compounds must be addressed, OPI mucilage represents a promising alternative to pectin, combining mineral richness and unique polysaccharide structures that could be exploited in targeted food applications following appropriate processing or formulation strategies.

4. Materials and Methods

One-year cladodes were collected from Sicilian (Italy) OPI plant as elsewhere reported [15]. According to the method of extraction with some modification reported [46], the chlorenchyma was removed manually, and all parenchyma were cut into little cubes. To ease the extraction of mucilage, the cubes were subjected to microwaves at 900 W for 5 min and grinded by a homogenizer (Omni-Mixer. 17, 107, Dupont Instruments Sorvall, Texas City, TX, USA). Then the homogenized material was centrifuged at 12,500 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C (6K15, Sigma Laborzentrifugen GmbH, Osterode am Harz, Germany) to separate the fibrous phase from the aqueous phase. This last part was collected in a plastic container and stored in a freezer at −20 °C until lyophilisation occurred. Freeze drying was performed with a SCANVAC Coolsafe 55-9 instrument produced by Labogene ApS (DK-3450 Lynge, Denmark). Pectin (E 440) amide standardised with dextrose, degree of esterification 30–40%, degree of amidation 15–20%, was supplied by Ruffini Distillerie (Tavarnelle Val di Pesa, FI, Italy).

4.1. Centesimal Composition

The AOAC methods [47,48] were used for the following analyses: moisture content (method 934.06); protein content using the Kjeldahl method with a conversion factor of 6.25 (method 960.52); lipid content using Soxhlet extraction (method 960.39); ash content by muffle furnace combustion at 550 °C (method 923.03); and total carbohydrate and fibre content by difference between 100 and the sum of the percentages of moisture, lipid, protein and ash content.

4.2. Ash and Minerals

Macro and trace elements were determined in all samples using an acid digestion procedure [49], with minor modifications. Samples (1 mL) were mixed with 5 mL of nitric acid (65%) and 1 mL of bi-distilled water and digested in a microwave system (MARS 6, CEM, Matthews, NC, USA) with a maximum temperature of 210 °C. After digestion, solutions were diluted with bi-distilled water and analysed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES; iCAP 6200 DUO, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The concentrations of Na, Mg, K, Ca, Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu, and Al were determined.

Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s multiple range test using JMP software (version 18). Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

4.3. Volatile Compounds

Volatile compounds were isolated using headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) and subsequently separated, identified and semi-quantified by gas chromatography single quadrupole mass spectrometry (GC–SQMS) employing an Agilent 6890 GC system connected to an Agilent 5973N single quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For the analysis, 1 g of powdered sample of mucilage or pectin was introduced into a 20 mL glass vial containing 1 g of sodium chloride, 8 mL of deionized water, and 0.25 mL of an internal standard solution (1-heptanol, 38.22 mg L−1, prepared in 10% v/v absolute ethanol). The mixture was equilibrated in a thermostatically controlled bath at 53 °C for 30 min. In parallel, the SPME fibre (50/30 μm DVB/Car/PDMS; Supelco Inc., Bellefonte, PA, USA) was conditioned at 250 °C for 15 min. Extraction was performed by exposing the fibre to the vial headspace for 60 min at 53 °C. Thermal desorption was carried out in the GC injector operating in splitless mode at 250 °C for 2 min. Chromatographic separation was achieved using a DB-WAX capillary column (Agilent Technologies; 30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness), with helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The oven temperature program was as follows: initial temperature of 40 °C held for 2 min; increase to 60 °C at 30 °C min−1 and hold for 2 min; ramp from 60 to 190 °C at 2 °C min−1; increase from 190 to 230 °C at 5 °C min−1; and finally hold at 230 °C for 15 min. The transfer line temperature was set at 230 °C. The mass spectrometer operated under electron impact ionization at 70 eV, acquiring data in full scan mode over an m/z range of 30–350.

4.4. Monosaccharide Compositions by 13C-NMR Analyses

In order to characterize the monosaccharide component of mucilage and pectin, an aliquot of both samples (50 mg) was hydrolysed by adding 5.0 mL of 2 M H2SO4 solution, keeping first the solution at 80 °C for 12 h and then heating at 130 °C for 1.5 h. After hydrolysis, each solution was neutralized at pH 7 by adding 14 M NH4OH. The solution was evaporated by rotavapor (Buchi R-200 Rotavapor System, BUCHI Italia S.r.l., 20007 Cornaredo, Italy), and then methanol was added to extract the simple sugars obtained via hydrolysis. The methanolic solution was filtered, evaporated, and the remaining solid was solubilized in D2O for NMR analysis.

The carbon spectra (13C-NMR) of the two hydrolysed samples obtained from mucilage and pectin were acquired in heavy water (D2O) using the Brucker Avance II spectrometer (Bruker Italia S.r.l., 20158 Milan, Italy) present at the CGA (Centro Grandi Apparecchiature) of the University of Palermo, operating at a frequency of 100 MHz for the acquisition of 13C-NMR. The chemical shifts reported in Table 4 and Table 5 are referenced to an external standard solution exploiting the anomeric carbon signal of β-D-glucopyranose (97.40 ppm) and the relative peak of the acetone carbonyl (217.22 ppm).

4.5. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3), with the exception of mineral determinations, which were carried out using six replicates (n = 6). Data are presented as mean values with their corresponding standard deviations. Depending on the dataset, statistical evaluation was conducted either by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or by an independent-samples t test. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and statistical significance was established at α = 0.05.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C.; methodology, F.T.; software, N.B. and M.P.; validation, N.B. and L.C.; formal analysis, N.B., F.M. (Francesca Malvano) and F.M. (Francesca Mazza); investigation, N.B., F.T. and F.M. (Francesca Mazza); resources, N.B. and M.B.; data curation, N.B. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, N.B. and L.C.; writing—review and editing M.P., N.B. and L.C.; visualization, L.C. and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Code P2022H573K implemented under PRIN 2022 PNRR—Funded by the European Union—Next Generation EU, Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.1, Innovative solutions in the wine sector (IN-WINE), CUP B53D23032670001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Griffith, M.P. The origins of an important cactus crop, Opuntia ficus-indica (Cactaceae): New molecular evidence. Am. J. Bot. 2004, 91, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Torres, L.; Brito-De La Fuente, E.; Torrestiana-Sanchez, B.; Katthain, R. Rheological properties of the mucilage gum (Opuntia ficus-indica). Food Hydrocoll. 2000, 14, 417–424. [Google Scholar]

- Maaoui, A.; Hassen Trabelsi, A.B.; Hamdi, M.; Chagtmi, R.; Jamaaoui, F.; Lopez, G.; Cortazar, M.; Olazar, M. Towards local circular economy through Opuntia Ficus Indica cladodes conversion into renewable biofuels and biochars: Product distribution and kinetic modelling. Fuel 2023, 332, 126056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.L.; Pérez Zamora, C.M.; Michaluk, A.G.; Nuñez, M.B.; Gonzalez, A.M.; Torres, C.A. Physicochemical and functional characterization of the mucilage obtained from cladodes of two Opuntia species. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voragen, A.G.J.; Coenen, G.J.; Verhoef, R.P.; Schols, H.A. Pectin, a versatile polysaccharide present in plant cell walls. Struct. Chem. 2009, 20, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz, C.; Sepúlveda, E.; Matsuhiro, B. Opuntia spp. mucilage’s chemical characterization and functional properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2004, 57, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, M.; Costa, T.M.H.; Gomaa, A.; Subirade, M.; de Oliveira Rios, A.; Flôres, S.H. Edible films based on Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 99, 105316. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/pectin-market (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- European Commission. New Rules for a More Sustainable and Competitive Packaging Economy Come into Force. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20240419IPR20589/new-eu-rules-to-reduce-reuse-and-recycle-packaging (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Morris, G.A.; Kök, S.M.; Harding, S.E.; Adams, G.G. Polysaccharide solutions: Molecular properties and rheological behavior. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 88, 158–164. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, B.R.; Singh, R.K.; Handa, A.K.; Rao, M.A. Chemistry and uses of pectin—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1997, 37, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannai, F.; Elhleli, H.; Yılmaz, M.; Khiari, R.; Mohamed Belgacem, N.B.; Moussaoui, Y. Precipitation solvents effect on the extraction of mucilaginous polysaccharides from Opuntia ficus-indica (Cactaceae): Structural, functional and rheological properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 202, 117072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooyen, B.; De Wit, M.; Osthoff, G.; Van Niekerk, J. Cactus Pear Mucilage (Opuntia spp.) as a Novel Functional Biopolymer: Mucilage Extraction, Rheology and Biofilm Development. Polym. J 2024, 16, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.; Paula, C.D.d.; Lahbouki, S.; Meddich, A.; Outzourhit, A.; Rashad, M.; Pari, L.; Coelhoso, I.; Fernando, A.L.; Souza, V.G.L. Opuntia spp.: An Overview of the Bioactive Profile and Food Applications of This Versatile Crop Adapted to Arid Lands. Foods 2023, 12, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torregrossa, F.; Pollon, M.; Liguori, G.; Gargano, F.; Albanese, D.; Malvano, F.; Cinquanta, L. Rheological and Physical Properties of Mucilage Hydrogels from Cladodes of Opuntia ficus-indica: Comparative Study with Pectin. Gels 2025, 11, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales-García, J.; Peña-Valdivia, C.B.; Razo-Martínez, Y.; Sánchez-Hernández, M. Acidity changes and pH-buffering capacity of nopalitos (Opuntia spp.). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2004, 32, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belén la Borde, M.; Tasca, J.E.; Barreto, G.P.; Pagano, A.M. Physicochemical characterization of pectin of rose grape Red Globe variety. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 59, 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, M.; Bordes, C.; Ariba, D.; Majdoub, M.; Majdoub, H.; Chevalier, Y. Emulsifying properties of biopolymer extracts from Opuntia ficus indica cladodes. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 683, 133005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebresamuel, N.; Gebre-Mariam, T. Comparative physico-chemical characterization of the mucilages of two cactus pears (Opuntia spp.) obtained from Mekelle, Northern Ethiopia. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2012, 3, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, A.; De Wit, M.; Hugo, A. Cultivar and Harvest Month Influence the Nutrient Content of Opuntia spp. Cactus Pear Cladode Mucilage Extracts. Molecules 2018, 23, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Procacci, S.; Bojórquez-Quintal, E.; Platamone, G.; Maccioni, O.; Vecchio, V.L.; Morreale, V.; Alisi, C.; Balducchi, R.; Bacchetta, L. Opuntia ficus-indica Pruning Waste Recycling: Recovery and Characterization of Mucilage from Cladodes. Nat. Resour. 2021, 12, 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Nawar, W.W. Lipids. In Food Chemistry, 3rd ed.; Fennema, O.R., Ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 225–319. [Google Scholar]

- Rocchetti, G.; Pellizzoni, M.; Montesano, D.; Lucini, L. Italian Opuntia ficus-indica Cladodes as Rich Source of Bioactive Compounds with Health-Promoting Properties. Foods 2018, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Zea, L.; Gutierrez-Uribe, J.A.; Serna-Saldivar, S.O. Comparative analyses of total phenols, antioxidant activity, and flavonol glycoside profile of cladode flours from different varieties of Opuntia spp. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7054–7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Moreno, E.; Córdoba-Díaz, D.; de Cortes Sánchez-Mata, M.; Díez-Marqués, C.; Honi, I. Effect of boiling on nutritional, antioxidant and physicochemical characteristics in cladodes (Opuntia ficus-indica). LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 51, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruwa, E.; Amoo, S.O.; Kudanga, T. Extractable and macromolecular antioxidants of Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes: Phytochemical profiling, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 125, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqash, F.; Masoodi, F.A.; Gani, A.; Nazir, S.; Jhan, F. Pectin recovery from apple pomace: Physico-chemical and functional variation based on methyl-esterification. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 4669–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkova, A.A.; Lisitskaya, K.V.; Filimonov, I.S.; Glazunova, O.A.; Kachalova, G.S.; Golubev, V.N.; Fedorova, T.V. Physicochemical and functional properties of Cucurbita maxima pumpkin pectin and commercial citrus and apple pectins: A comparative evaluation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikiera, A.; Grabacka, M.; Byczyński, Ł.; Stodolak, B.; Mika, M. Enzymatically Extracted Apple Pectin Possesses Antioxidant and Antitumor Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todhanakasem, T.; Boonchuai, P.; Itsarangkoon Na Ayutthaya, P.; Suwapanich, R.; Hararak, B.; Wu, B.; Young, B.M. Development of Bioactive Opuntia ficus-indica Edible Films Containing Probiotics as a Coating for Fresh-Cut Fruit. Polymers 2022, 14, 5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, J.E.; Knox, L.A.; Donart, G.B.; Petersen, M.K. The nutritive quality of cholla cactus as affected by burning. J. Range Manag. 2001, 54, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Esparza, M.E.; Raigón, M.D.; García-Martínez, M.D.; Albors, A. Role of Hydrocolloids in the Structure, Cooking, and Nutritional Properties of Fiber-Enriched, Fresh Egg Pasta Based on Tiger Nut Flour and Durum Wheat Semolina. Foods 2021, 10, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.A.; Albuquerque, T.G.; Pereira, P.; Ramalho, R.; Vicente, F.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Costa, H.S. Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill.: A Multi-Benefit Potential to Be Exploited. Molecules 2021, 26, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintero-García, M.; Gutiérrez-Cortez, E.; Bah, M.; Rojas-Molina, A.; Cornejo-Villegas, M.d.l.A.; Del Real, A.; Rojas-Molina, I. Comparative Analysis of the Chemical Composition and Physicochemical Properties of the Mucilage Extracted from Fresh and Dehydrated Opuntia ficus-indica Cladodes. Foods 2021, 10, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, G.; Merra, R.; Badalamenti, N.; Lazzara, G.; Bruno, M.; Sottile, F. Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. and Opuntia stricta (Haw.) Haw. Mucilage-Based Painting Binders for Conservation of Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Olivos, A.; León-Martínez, F.M.; Soto-Castro, D.; Robles-Franco, E.; Álvarez-Bajo, O.; Felipe de Jesús Cano-Barrita, P. Functional, rheological, and physicochemical properties of Opuntia ficus indica and Opuntia undulata mucilages. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happi Emaga, T.; Rabetafika, N.; Blecker, C.S.; Paquot, M. Kinetics of the hydrolysis of polysaccharide galacturonic acid and neutral sugars chains from flaxseed mucilage. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2012, 16, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- King-Morris, M.J.; Serianni, A.S. Carbon-13 NMR studies of [1-13C] aldoses: Empirical rules correlating pyranose ring configuration and conformation with carbon-13 chemical shifts and carbon-13/carbon-13 spin couplings. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 3501–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslauriers, R.; Jarrell, H.; Byrd, R.A.; Smith, I.C.P. Observation by 13 C-NMR of metabolites in differentiating amoeba trehalose storage in encysted Acanthamoeba castellanii. FEBS Lett. 1980, 118, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.A.; Ryona, I.; Sacks, G.L. Behavior of 3-Isobutyl-2-hydroxypyrazine (IBHP), a Key Intermediate in 3-Isobutyl-2-methoxypyrazine (IBMP) Metabolism, in Ripening Wine Grapes. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 11901–11908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamolo, F.; Wüst, M. 3-Alkyl-2-Methoxypyrazines: Overview of Their Occurrence, Biosynthesis and Distribution in Edible Plants. ChemBioChem 2023, 24, e202300362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, P.J.; McNair, H.M.; Zoecklein, B.W. Measurement of 3-alkyl-2-methoxypyrazine by headspace solid-phase microextraction in spiked model wines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2002, 53, 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-López, A.J.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A.; García-Viguera, C. Volatile compounds and off-flavour reduction in cactus cladodes by thermal processing. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 55, 437–444. [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz, C.; Berger, H.; Rodríguez-Félix, A.; Galletti, L.; García, J.C.; Sepúlveda, E.; Varnero, M.T. Agro-Industrial Utilization of Cactus Pear; FAO Plant Production and Protection Paper: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Buttery, R.G.; Seifert, R.M.; Guadagni, D.G.; Ling, L.C. Characterization of methoxypyrazines and their removal in vegetable products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 412–418. [Google Scholar]

- du Toit, A. Selection, Extraction, Characterization and Application of Mucilage from Cactus Pear (Opuntia ficus-indica and Opuntia robusta) Cladodes. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Consumer Science, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2016; p. 370. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 21st ed.; AOAC International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 22nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima, L.M.; Valente Soares, L.M. Mineral profile of raw and cooked leafy vegetables consumed in Southern Brazil. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2003, 16, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.