Sol–Gel Engineered MXene/Fe3O4 as an Efficient Mediator to Suppress Polysulfide Shuttling and Accelerate Redox Kinetics

Abstract

1. Introduction

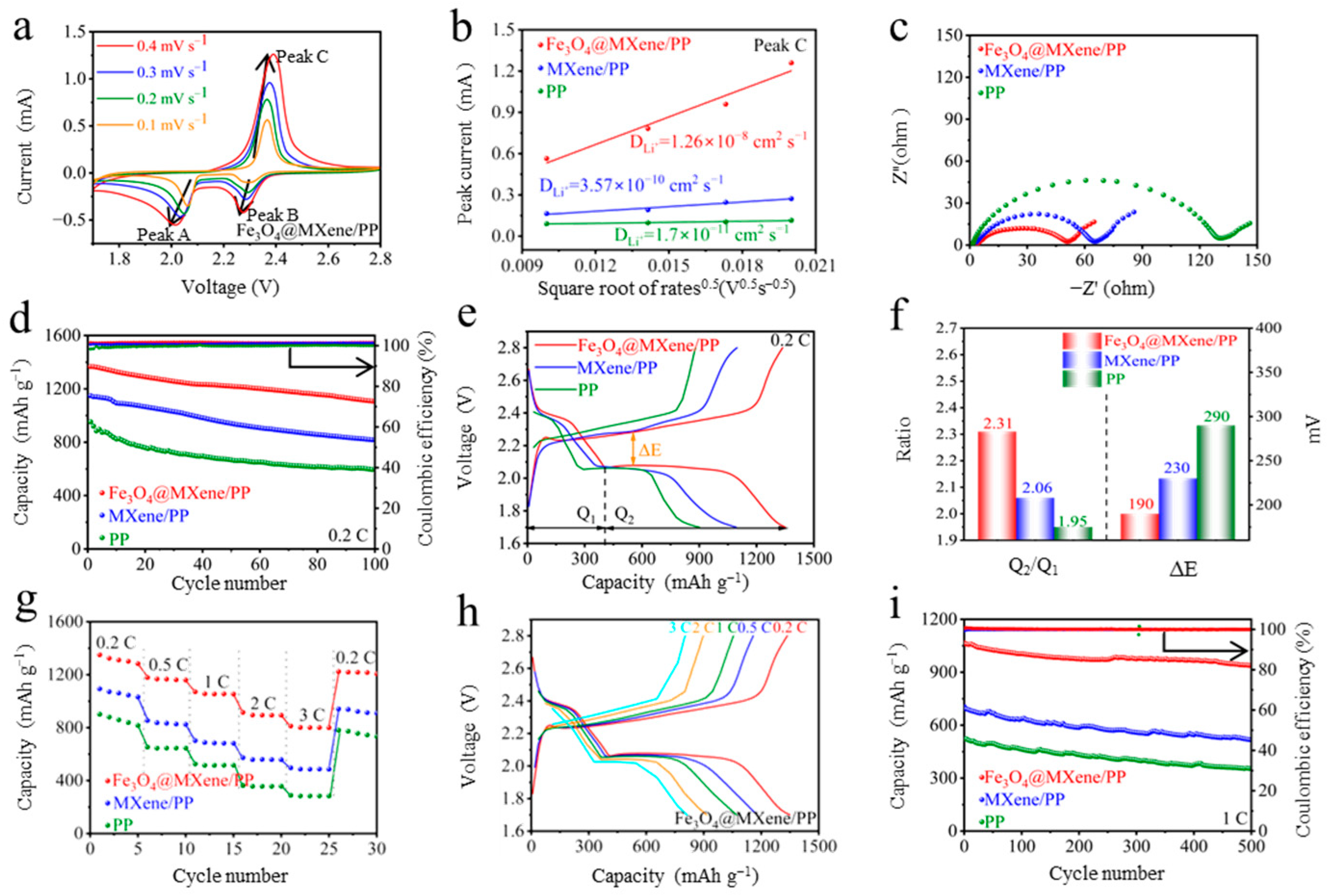

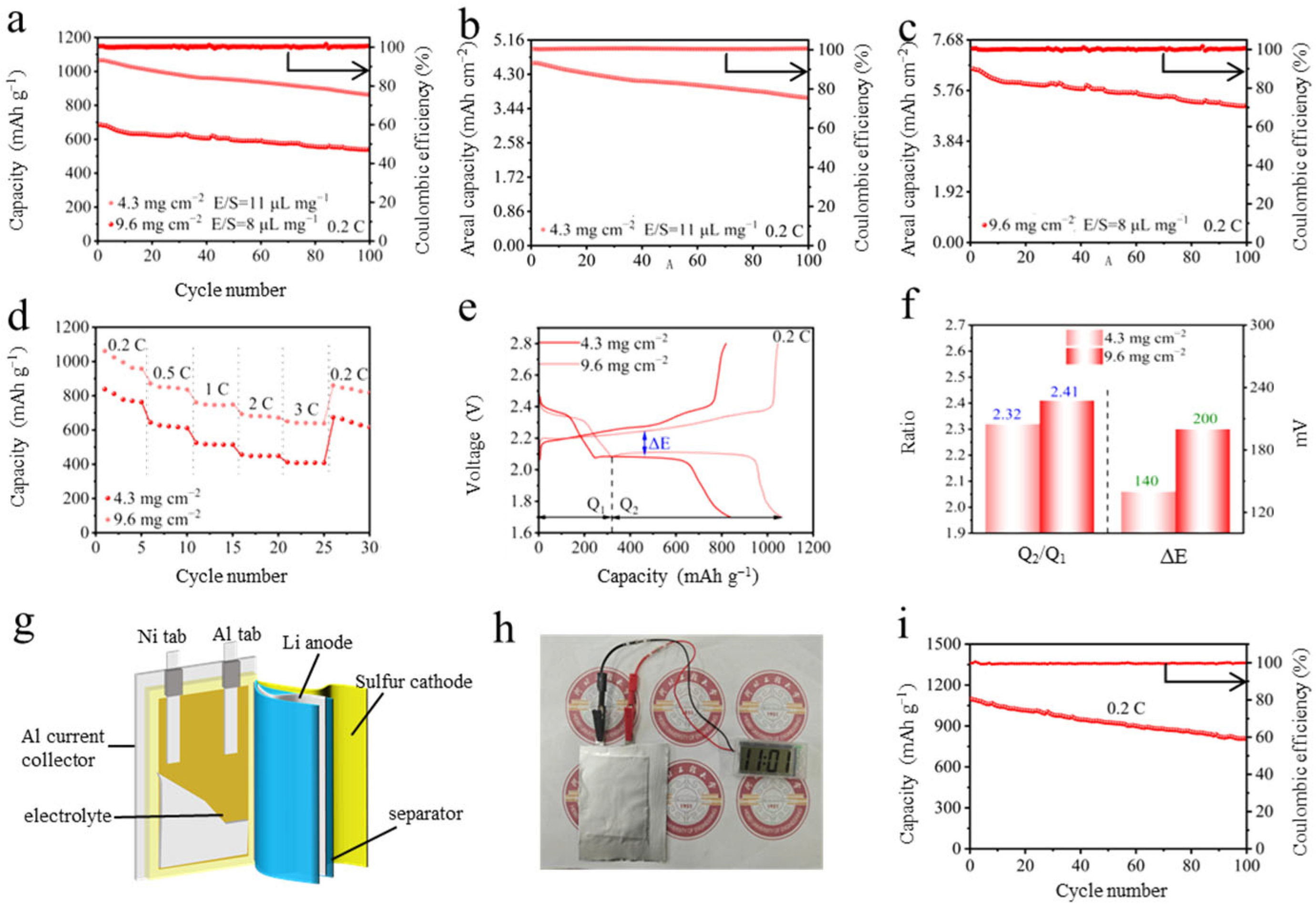

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation

4.3. Assembling the Battery

4.4. Material Characterization

4.5. Electrochemical Properties

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leckie, T.J.; Robertson, S.D.; Brightman, E. Recent Advances in in Situ/Operando Characterization of Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. Energy Adv. 2024, 3, 2479–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yari, S.; Conde Reis, A.; Pang, Q.; Safari, M. Performance Benchmarking and Analysis of Lithium-Sulfur Batteries for next-Generation Cell Design. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.T.; Rao, A.; Nie, H.-Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, W.; Zhao, F.; Deng, S.; Hao, X.; Fu, J.; Luo, J.; et al. Manipulating Li2S2/Li2S Mixed Discharge Products of All-Solid-State Lithium Sulfur Batteries for Improved Cycle Life. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzedine, M.; Jardali, F.; Florea, I.; Cojocaru, C.-S. Nanostructured S@VACNTs Cathode with Lithium Sulfate Barrier Layer for Exceptionally Stable Cycling in Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171, 050531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doñoro, Á.; Muñoz-Mauricio, Á.; Etacheri, V. High-Performance Lithium Sulfur Batteries Based on Multidimensional Graphene-CNT-Nanosulfur Hybrid Cathodes. Batteries 2021, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.; Fathy, H.K. A Reduced-Order Model of Lithium–Sulfur Battery Discharge. Batteries 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Li, H.; Guo, Y.; Li, B.; Li, F.; Parks, H.C.W.; Bird, L.R.; Miller, T.S.; Shearing, P.R.; Jervis, R.; et al. A Quasi-Solid-State High-Rate Lithium Sulfur Positive Electrode Incorporating Li10GeP2S12. Commun. Mater. 2025, 6, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xie, R.; Cai, D.; Fei, B.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Q.; Sa, B.; Zhan, H. Engineering Defect-Rich Bimetallic Telluride with Dense Heterointerfaces for High-Performance Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2315012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Chen, M.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, C.; Wang, N.; Lei, W.; Guo, Y.; Li, L. Engineering Spin State in Spinel Co3O4 Nanosheets by V-Doping for Bidirectional Catalysis of Polysulfides in Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2402114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Qi, Z.; Song, G.; Huang, S.; Du, Z.; Dong, J.; Guan, C.; Luo, P.; Gan, P.; Yu, B.; et al. α-MnO2/RuO2 Heterostructure-Modified Polypropylene Separator for High-Performance Lithium–Sulfur Battery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2403101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhang, X.; Yang, D.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, S.; Qiu, J.; Ma, T.; Ba, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Defect-Engineered VS2 Electrocatalysts for Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 7411–7418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; He, J.; Zhu, Z.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, J.; Lu, B.; Wu, Y. Heterostructures Regulating Lithium Polysulfides for Advanced Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2303520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Vijayan, V.; Lee, J.S.; Park, S.S.; Cui, X.; Chung, I.; Lee, J.; Ahn, S.-K.; Kim, J.R.; et al. ROS- and pH-Responsive Polydopamine Functionalized Ti3C2Tx MXene-Based Nanoparticles as Drug Delivery Nanocarriers with High Antibacterial Activity. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Beyene, T.T.; Zheng, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, K. Review and Perspectives on Preparation Strategies and Applications of Ti3C2 MXene for Li Metal Batteries/Li–S Batteries. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 14866–14890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Li, S.; Peng, X.; Yuan, L.; Lu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, H. Highly Stable and Active Cerium Single-Atom Immobilized Ti3C2Tx MXene for High-Stability Lithium-sulfur Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 521, 166774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Wang, S.; Lu, X.; Jia, X.; Yang, J.; Liang, F.; Xie, Q.; Yang, C.; Qian, J.; Song, H.; et al. High-Entropy MXene as Bifunctional Mediator toward Advanced Li–S Full Batteries. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 2395–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, R.; He, T.; Xiang, L.; Wu, X.; Piao, Z.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; et al. Fe3O4-Doped Mesoporous Carbon Cathode with a Plumber’s Nightmare Structure for High-Performance Li-S Batteries. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Cui, G.; Li, M.; Bakenov, Z.; Wang, X. Defect-Rich Multishelled Fe-Doped Co3O4 Hollow Microspheres with Multiple Spatial Confinements to Facilitate Catalytic Conversion of Polysulfides for High-Performance Li–S Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 12763–12773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, H.; Hong, M.J.; Chang, H.; Moon, J.; Kim, Y.; Mun, J.; Kim, K.J. Stable Immobilization of Lithium Polysulfides Using Three-dimensional Ordered Mesoporous Mn2O3 as the Host Material in Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. Carbon Energy 2024, 6, e487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Jiang, H.; Yu, M.; Li, X.; Dai, Y.; Zheng, W.; Jiang, X.; He, G. Sandwich-Structured Flexible Interlayer with Co3O4 Nanoboxes Strung along Carbon Nanofibers on Both Sides for Fast Li+ Transport and High Redox Activity in High-Rate Li-S Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 449, 137777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, S.; Kanwal, A.; Zubair Iqbal, M.; Yousaf, M.; Mahmood, A.; Rizwan, S. Multivalent Metal-Ions Intercalation for Enhanced Structural Stability and Pseudocapacitance in Titanium Carbonitride (Ti3CNTₓ) MXenes for Asymmetric Supercapacitor Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmasiri, B.; Usman, K.A.S.; Qin, S.A.; Razal, J.M.; Tran, N.T.; Coia, P.; Harte, T.; Henderson, L.C. Ti3C2Tx MXene Coated Carbon Fibre Electrodes for High Performance Structural Supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 476, 146739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.M.; Fouad, O.A.; Eliwa, A.S.; Mohamed, G.G.; Hosny, W.M.; Hefnawy, M.A. Chemical and Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Use as an Electrocatalyst for Water Splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 159, 150536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhosh Kumar, R.; Sidra, S.; Poudel, M.B.; Kim, D.H.; Yoo, D.J. Scrutinizing the Redox Activity of MOF-Derived Fe–Se–C and P@Fe–Se–C Species to Improve Overall Water Electrolysis and Alkaline Zinc–Air Batteries. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 23087–23099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, W.; Wu, H.; Wu, Y.; Shi, K.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Q. 3d-Orbital High-Spin Configuration Driven From Electronic Modulation of Fe3O4/FeP Heterostructures Empowering Efficient Electrocatalyst for Lithium−Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2409303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Duan, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. MXene-Derived Nano N-TiO2 @MXene Loaded with Fe3O4 for Photo-Fenton Synergistic Degradation of Phenol. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 20653–20664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhou, P.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, J.; Miao, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhuo, S. Fe3O4@Ti3C2 MXene Hybrids with Ultrahigh Volumetric Capacity as an Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 11189–11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Sheng, H.; Dou, W.; Su, Q.; Zhou, J.; Xie, E.; Lan, W. Fe2O3 Nanoparticles Anchored on the Ti3C2Tx MXene Paper for Flexible Supercapacitors with Ultrahigh Volumetric Capacitance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 41410–41418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Kempa, K.; Wang, X. Boosting the Electrochemical Performance of Lithium/Sulfur Batteries with the Carbon Nanotube/Fe3O4 Coated by Carbon Modified Separator. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 327, 134843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, G.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, D.; Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Mo, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. Multi-Dimensional Composite Frame as Bifunctional Catalytic Medium for Ultra-Fast Charging Lithium–Sulfur Battery. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Han, Y.; Rong, L.; Yao, H.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Mei, T. Engineering TiO2/ZnS@MXene Three-Phase Heterostructure for Enhanced Polysulfide Capture and Sulfur Kinetics in High-Performance Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2026, 703, 139101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulakhsmi, N.; Sundar, S.; Karthik, N.; Kathiresan, M.; Santhosh Kumar, R.; Yoo, D.J.; Stephan, A.M. Enhanced Cycling Performance of Li–S Cells by Mitigation of Lithium Polysulfides Encompassing Palladated Porous Aromatic Polymer-Coated Membranes. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shan, Z.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Sun, G.; Geng, Y.; Chang, G. Sol–Gel Engineered MXene/Fe3O4 as an Efficient Mediator to Suppress Polysulfide Shuttling and Accelerate Redox Kinetics. Gels 2025, 11, 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120959

Shan Z, Li X, Li Y, Wang Y, He Y, Sun G, Geng Y, Chang G. Sol–Gel Engineered MXene/Fe3O4 as an Efficient Mediator to Suppress Polysulfide Shuttling and Accelerate Redox Kinetics. Gels. 2025; 11(12):959. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120959

Chicago/Turabian StyleShan, Zhenzhen, Xiaoxiong Li, Yalei Li, Yong Wang, Yusen He, Guangyu Sun, Yamin Geng, and Guoqing Chang. 2025. "Sol–Gel Engineered MXene/Fe3O4 as an Efficient Mediator to Suppress Polysulfide Shuttling and Accelerate Redox Kinetics" Gels 11, no. 12: 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120959

APA StyleShan, Z., Li, X., Li, Y., Wang, Y., He, Y., Sun, G., Geng, Y., & Chang, G. (2025). Sol–Gel Engineered MXene/Fe3O4 as an Efficient Mediator to Suppress Polysulfide Shuttling and Accelerate Redox Kinetics. Gels, 11(12), 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120959