Abstract

Colombia is the Latin American country with the second-largest area planted with OxG hybrid cultivars, covering more than 120,000 hectares Various health problems can affect yield, especially those affecting fruit. Since 2021, white fruit rot has been reported in the northern, central, and southwestern palm-growing areas. Therefore, the objective of this study is to identify associated symptoms and their causal agent. To this end, a total of six locations in the three palm-growing regions were visited, and 36 samples of affected fruits were collected to obtain microorganisms. These microorganisms were inoculated into detached fruits under in vitro conditions, and seven isolates were inoculated into bunches in the field. They were morphologically and molecularly characterized by partial sequencing of the ITS and TEF1 regions. Symptoms of white rot were observed, starting from the base of the fruit to the apex, with the development of a cottony mycelial mass, followed by the formation of sclerotia. A total of 33 organisms were obtained, 30 isolates identified as Agroathelia rolfsii, one Fusarium sp., one Rhizoctonia sp., and one Pestalotiopsis sp. isolate. The Agroathelia isolates exhibited white, cottony growth adhering to the surface of the PDA culture medium. After four days of growth, they developed globose to ellipsoid sclerotia (average 1.00 ± 0.26 (0.46–2.20 mm)). These were initially white and turned brown as they developed, with the average number of sclerotia per plate ranging from 4 to 449 (n = 6). In the in vitro pathogenicity test, only A. rolfsii isolates were pathogenic, with a 100% incidence, an average severity ranging from 10 to 40% infection, and a range of 10 to 100%. In field inoculations, 100% of the inoculated bunches exhibited symptoms similar to those observed under natural field conditions. In all cases, the pathogen was recovered, fulfilling Koch’s postulates and confirming that A. rolfsii is the causal agent of white fruit rot. This constitutes the first record of Agroathelia rolfsii in oil palm in Colombia.

1. Introduction

Oil palm is currently the fastest-growing crop in Colombia, supplying most of the national oil and fat market and contributing 14% to the country’s agricultural GDP with more than 609,000 hectares planted by 2024. It is projected to reach an annual production of approximately 1.72 million tons of crude oil, ranking it as the world’s fourth-largest producer [1]. Due to phytosanitary problems, primarily bud rot and lethal wilt, the renewal of planted areas in the country has been achieved using interspecific OxG (Elaeis oleifera × E. guineensis) hybrid cultivars, which currently cover more than 90,000 hectares. These cultivars are being implemented in countries such as Ecuador, which currently has approximately 109,076 hectares planted (Ancupa, unpublished data), and Brazil, which has approximately 13,500 hectares planted (Gerson Gloria Agropalma, unpublished data).

As hybrid cultivars have become more widely planted in Colombia, phytosanitary problems have become visible, among which bunch rot has been observed. This disease has been recorded in three palm-growing oil regions of the country, North, Central, and Southwest, where temperatures over the past 30 years have fluctuated between 24.3 and 29.0 °C. The Southwest zone recorded the lowest average temperature with a value of 26.4 °C, while the Central (27.3 °C) and Northern (28.4 °C) zones presented higher averages [2,3]. In these regions, the disease typically begins with the initial rotting of some fruits and progresses to affect the entire bunch, which becomes covered with a white mycelial mass.

As pathogens associated with fruit bunches in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) cultivars, only Marasmius palmivorus has been reported [4,5,6]. Considering the findings of [4] and the current situation in Colombia, where few cases have been reported, the disease has been neglected and is often interpreted as having a limited economic impact. However, in other palms, such as the areca palm (Areca cathechu L.), fruit rot (FRD) caused by Phytophthora meadii is a significant limitation in areca nut production, with crop losses ranging from 10 to 90%. Reports estimate economic losses of up to 75% and destruction of palm areas [7]. In coconut crops (Cocos nucifera L.), fruit rot causes yield losses, as seen in southern Taiwan and Brazil due to Ceratocystis paradoxa rot. This occurs year-round but is more severe in warmer seasons [8].

The genus Agroathelia, includes species that cause a wide range of plant diseases. Among them, Agroathelia rolfsii (Sacc.) Redhead & Mullineux (Syn. Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc.) has been reported to cause collar-rot, sclerotium wilt, stem-rot, charcoal rot, seedling blight, damping-off, foot-rot, stem blight and root rot in more than 500 plant species, including tomato, chili, sunflower, cucumber, eggplant, soybean, maize, groundnut, beans, pumpkin, sugar beet, jackfruit, among other [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Significant yield losses have been associated with this pathogen, particularly under environmental conditions favorable for fungal development, such as high temperature and humidity [14].

Despite the threat of yield loss and the sustainability of oil palm crops in Colombia, the causal agent of the white fruit rot observed in different plantations across the northern, central, and southwestern regions since 2021 remains unidentified. Therefore, the objectives of this study were (i) to identify and describe the symptoms of this disease; (ii) to conduct pathogenicity tests with the microorganisms obtained; (iii) to identify the pathogen responsible for this phytosanitary problem through morpho-cultural characterization and DNA sequence analysis. These constitute crucial steps for implementing the necessary management practices to mitigate both the incidence and severity of the disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Symptom Description and Isolate Collection

To verify symptoms, commercial plantations with reports of bunch rot in OxG hybrid cultivars were visited in the Northern (Chigorodó, Carepa and Turbo, Antioquia; Banana Zone and Aracataca, Magdalena), Central (Barrancabermeja and Puerto Wilches, Santander), and Southwestern (Tumaco, Nariño) palm-growing regions (Table 1). These regions presented typical tropical climatic conditions, with annual rainfall ranging from 1104 to 3074 mm, minimum average temperature of 21.6 °C and a maximum of 32 °C and relative humidity values between 71 and 86%, depending on the sampling site. Fruits with white mycelium and areas of advanced internal damage were collected to obtain associated microorganisms. A total of 73 samples were collected from 21 palm oil plantations (8 municipalities). These samples were collected in plastic bags, labeled (plantation, lot, row, palm, cultivar), and transported refrigerated to the Plant Pathology laboratories of the Palmar de la Sierra Experimental Field in the northern zone and the Palmar de la Vizcaina Experimental Field in the central zone of the Oil Palm Research Center Corporation for processing. Sampling was covered by Individual Permit No. 2431 for the Collection of Wild Specimens of Biological Diversity, issued by the National Environmental Licensing Authority (ANLA) on 24 December 2018.

Table 1.

Codes, location, identification, and GenBank accession numbers of the isolates of the Agroathelia rolfsii.

Fruits were collected at different stages of disease progression, and tissue samples were taken from the advanced lesion zone along with sclerotia. In the laboratory, the tissue samples were cut into 5 mm pieces, and sclerotia were collected, which were disinfected with 70% ethanol for 30 s, followed by 1% sodium hypochlorite (commercial NaClO product, 5.25%) for 1 min. Finally, they were washed three times with sterile distilled water and dried. The tissues were subsequently transferred to potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium supplemented with the antibiotic streptomycin (100 mg/L). The Petri dishes were incubated under laboratory conditions at 24 ± 2 °C until microorganisms appeared. These were then transferred to new dishes until pure colonies were obtained.

2.2. Pathogenicity Test

The pathogenicity of each isolate obtained was evaluated in vitro on detached fruit and in vivo on fruit from palms established in the field. For the in vitro test, 400 fruits were selected from seven healthy bunches of the hybrid OxG palm cultivar Coari × La Me at phenological stage 805 (approximately 75% oil accumulation) [16] from Lote 2 of the Palmar de la Vizcaina Experimental Field, located in the central zone of the Oil Palm Research Center Corporation. The fruits were washed with running water and Tween 20 for 1 h, then disinfected with 10% calcium hypochlorite (commercial CaClO2, 70%) for 30 min and finally rinsed three times with sterilized distilled water. They were then dried with sterilized towels. Finally, under extraction chamber conditions, disinfection was performed using chlorine gas, based on the methodology described by [17] with modifications in chemical concentrations and exposure time, as the original protocol was developed for seeds. In this study, the fruits were placed in individual containers exposed to the gas generated from a mixture of 30% HCl and 1% NaClO for 5 min. The experimental design was completely randomized, with each fruit serving as an experimental unit. The pathogenicity test included the 33 fungi isolated in this study plus a control, and each treatment consisted of 12 replicates. Each fruit was inoculated with a 5 mm disc of actively growing mycelium from each isolate at the base of the fruit, without making an artificial wound. The inoculated fruits were placed separately in sterilized humid chambers consisting of an aluminum tray, a paper towel moistened with 3 mL of water at the base of the tray to maintain high humidity, and a plastic lid to hold the fruit while preventing direct contact with moisture. For the controls, a disc of pathogen-free culture medium was placed on the surface of the fruit. They were then maintained under laboratory conditions, at a temperature of 24 ± 2 °C, with a photoperiod of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness for 30 days. Finally, the presence of lesions on the fruits and the affected area relative to the total fruit area were evaluated. For this, a longitudinal cut was made at the midpoint of the base of the fruit and a photograph was taken to measure the affected area using the ImageJ software 1.54r [18] which was used to calculate the percentage of internal damage. A nonparametric test (Kruskal–Wallis) was used to identify differences in responses between treatments and control.

Following the in vivo pathogenicity test, seven isolates from the first location where the disease was reported (CPSrZN02, CPSrZN03, CPSrZN04, CPSrZN05, CPSrZN06, CPSrZN07, and CPSrZN08), were inoculated in a field pathogenicity test in Lot PL-18 planted with the cultivar Coari × La Me, in a plantation located in the municipality of Chigorodó, Antioquia. Three healthy bunches with fruit at stage 805 of ripening [16] were selected per isolate for evaluation. For this test, twenty-day-old colonies of the fungi were used to prepare the inoculum. Mycelium was collected from culture plates using a bacteriological loop and transferred to a blender jar containing sterile distilled water. The suspension was homogenized by blending to fragment the mycelium until reaching a final concentration of 5.6 × 104 mycelial fragments/mL for each isolate. Then, the suspension was transferred to hand sprayers, and 60 mL was applied to each bunch. After inoculation bunches were immediately protected with polyester bag (PBS International, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, UK) to prevent contamination and maintain humidity. The bags are designed to facilitate gas exchange between the bunches and the environment. Control bunches were sprayed only with sterile distilled water. All bunches were monitored daily until symptoms appeared.

2.3. Morphological Characterization

Cultural and morphological characterization was performed on 12 isolates using PDA culture medium, selecting three for each area where isolates were recorded. Five-mm diameter discs were taken from the edge of the colony of each isolate, grown for 10 days on PDA medium, and placed in the center of a new Petri dish. Six replicates were performed for each isolate. The Petri dishes were incubated at 28 ± 2 °C in an incubator under a photoperiod of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness for 15 days. The growth rate was assessed through daily observations, recording the color and sclerotia formation. The number of sclerotia produced per isolate was counted manually for each Petri dish. Shape and size were recorded on 30 sclerotia from each Petri dish using a micrometer on an Olympus BX43 light microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Using the same equipment, fungal structures were observed, and micrographs were taken with an Olympus DP73 camera (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at magnifications of 40× and 100×. Biometric variables were estimated using CellSens® software V1.18 (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

2.4. Evaluation of Mycelial Compatibility

To determine mycelial compatibility among Agroathelia sp. isolates, the 12 isolates used in the morphological characterization were selected. Each isolate was paired with itself and with all other isolates [19] To accomplish this, a 5 mm disc of actively growing mycelium from each isolate was placed on the opposite side of a 90 mm diameter Petri dish containing 25 mL of PDA medium. A total of 66 interactions were performed with three replicates. They were incubated in the dark at 25 °C. The interactions were examined macroscopically after 5 and 10 days to detect the presence of an antagonism zone in the mycelial contact region. Interactions between isolates were classified according to the degrees of antagonism proposed by [20]: 0 = compatible, 1 = weak interaction, 2 = moderate interaction, and 3 = strong interaction.

2.5. Molecular Characterization, DNA Extraction, and Amplification

The biomass development of all the isolates was achieved in Potato Dextrose Broth (DIFCO) with shaking at 110 rpm for 7 days. Subsequently, the mycelium was dried in an oven 180 °C overnight. Total genomic DNA was extracted from 200 mg of mycelium using the NucleoSpin™ Plant II Mini Kit (Macherey-Nagel™, Düren, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was stored at −20 °C until it was used. The ITS gene region was amplified using primers ITS1 and ITS4 [21], and the TEF1-α region was amplified with primers EF1-983F and EF1-1567R [22]. PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 25 µL, containing: 12.5 µL of GoTaq® Green Master Mix (Promega), 0.5 µL of each primer (10 µM), 2 µL of DNA (200 ng/µL), and 9.5 µL of nuclease-free water. The amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, the annealing temperature at 58 °C for ITS and at 55 °C for TEF1-α, extension at 72 °C for 1 min and with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, a 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to visualize the amplification of the regions of interest under conditions of 90 V for 30 min. The positive PCR products were sent to the SSiGmol-Instituto de Genética de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia, located on the Bogotá campus, for sequencing.

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

The obtained sequences were edited using Chromas software (Chromas version 2.0, 2023, Technelysium Pty Ltd., South Brisbane, QLD, Australia, www.technelysium.com.au, accessed on 25 November 2025), and consensus sequences were constructed using Sequencher 5.4.6 (Sequencher® version 5.4.6 DNA sequence analysis software, Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, http://www.genecodes.com, accessed on 25 November 2025). Once the sequences were refined, their identity was confirmed by comparing them with the GenBank database using BLASTn software 2.17.0 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST, accessed on 25 November 2025). The cleaned sequences were then aligned, analyzed, and manually edited using MEGAX (University Park, PA 16802 USA) (Table 1) [23]. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the maximum likelihood (ML) method with RAxML 8.2.12 software [24], and the internal reliability of the nodes was determined using the bootstrap method with 1000 iterations. The species Rhizoctonia endophytica (CBS 257.60) was used as an external group for the ITS phylogenetic tree, and R. solani (KACC 48426) for the TEF1-α phylogenetic tree (Table 2).

Table 2.

Morphological characterization of Agroathelia rolfsii isolates from different localities, including the number of sclerotia, sclerotia size (mean ± SD, (min–max)) in µm, and mycelial growth rate (mean ± SD) in mm/day on PDA medium.

3. Results

3.1. Symptom Description

White fruit rot (WFR) was observed in plantations with interspecific hybrid OxG cultivars in the central, northern, and southwestern regions of Colombia. The disease develops mainly from the onset of fruit and bunch ripening, a process that begins with the drastic color change (stage 803), and exhibited greater severity as ripening progressed. As ripening progressed, fungal colonization increase became more evident in stages 805 to 809, which corresponded to the phase of increasing relative oil potential, reaching its maximum value at stage 809 [25,26]. Initial symptoms are small, moist, irregularly growing spots at the base of the fruit that affect the exocarp and progressively advance, presenting the development of white mycelial growth. This mycelium eventually presents small, crystalline beige watery dots or droplets, which, as they progress, turn ivory beige, followed by a caramel to brown color in the more mature stages (Figure 1). This mycelial growth, along with the presence of small sclerotia, colonizes the fruit from the base to the apex as they develop, covering a large part of the bunch. Internally, aqueous degradation of the mesocarp tissue is observed, which subsequently affects the endocarp, ultimately leading to the complete loss of the fruit’s integrity (Figure 2). Under high humidity conditions, the development of mycelium and sclerotia was observed in dry or senescing petiole base tissues (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

External symptoms observed in oil palms affected by White fruit rot in the field in Colombia. (A,B) Initial development of white mycelial growth from the base to the apex of the fruit. (C,D) Development of sclerotia as small, crystalline beige watery dots or droplets, which become ivory beige as they mature. (E) More mature sclerotia, ranging from caramel to brown in the most mature stages. (F) Under high humidity conditions, mycelial and sclerotial development was observed in dry or senescing petiole base tissues.

Figure 2.

Internal development of symptoms of Agroathelia rolfsii in oil palm hybrids in Colombia.

3.2. Isolated Microorganisms

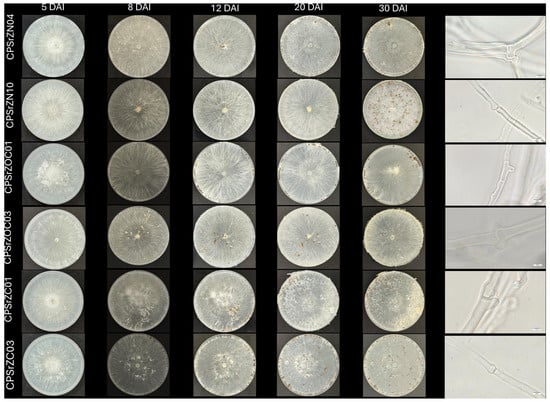

A total of 36 samples were collected from which 33 microorganisms were obtained, corresponding to 30 isolates identified as Agrothelia rolfsii, one Fusarium sp., one Rhizoctonia sp., and one Pestalotiopsis sp. These isolates were stored under the codes from the Cenipalma microorganism bank described in Table 1. The Agroathelia isolates presented colonies with abundant white mycelial growth, initially adhering to the surface of the PDA culture medium, then becoming cottony and aerial, with a daily growth rate ranging from 19 ± 0.26 to 31.4 ± 0.84 mm/day. After four days of growth, they developed globose to ellipsoid sclerotia with a diameter of 1.03 mm (0.458–2.2 mm) (n = 30). These were initially white, and as they developed, they turned brown, with an average of 4 to 449 sclerotia per plate (n = 6) (Figure 3, Table 2).

Figure 3.

Morphological characteristics and micromorphology of isolates CPSrZN04, CPSrZN10, CPSrZOC01, CPSrZOC03, CPSrZC01, and CPSrZC03 on potato dextrose agar after 5, 8, 12, 20, and 30 days in incubation at 25 °C.

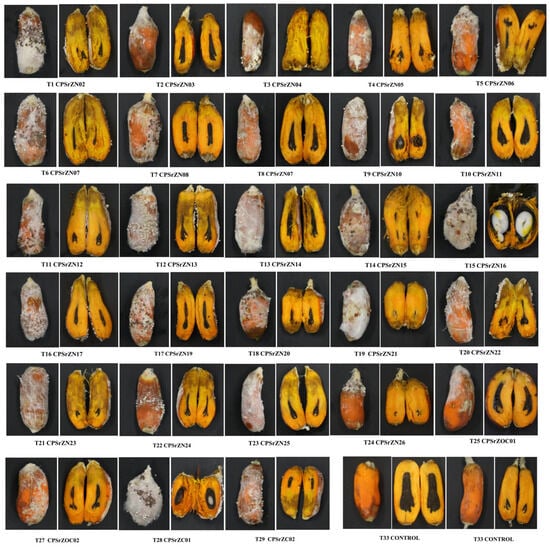

3.3. Pathogenicity Tests

All Agroathelia isolates were pathogenic compared to the control, with a range of 47.1% to 100% of isolates that were pathogenic. The affected area ranged from 1% to 47% of the fruit area with positive pathogenicity (Figure 4). A Kruskal–Wallis test showed differences between groups (p < 0.001), with a test statistic of H = 91.524 and 32 degrees of freedom (df). The effect size was moderate (ε2 = 0.151; η2[H] = 0.164). The analysis was based on 396 observations distributed across 33 groups (k = 33). These results confirm that the variability in the affected area is not random but depends on the treatment applied (Table 3). Isolates T2, T7, T16, and T26 did not show significant differences, with the percentage of affected areas ranging from 11% to 13.5%. However, strain CPSrZn03, CPSrZN08, CPSrZN17, and CPSrZOC003 had an incidence of 50% or greater. In contrast, T5—CPSrZN06 had the highest percentage of affected area (47.1%), followed by isolates T3 (CPSrZN04), T21 (CPSrZN23), T14 (CPSrZN15), T19 (CPSrZN21), and T28 (CPSrZC01), with infection rates above 36%. In field inoculations, all inoculated strains were pathogenic, displaying symptoms similar to those observed in naturally infected palms (Figure 5). In all cases, the pathogen was isolated again, fulfilling Koch’s postulates and thus confirming that Agroathelia rolfsii is the causal agent of white fruit rot. This constitutes the first record of this pathogen in oil palm in Colombia.

Figure 4.

In vitro development of symptoms in detached fruits inoculated with Agroathelia rolfsii isolates from oil palm fruits affected by white rot in the northern, central, and southwestern zones of Colombia.

Table 3.

Dunn’s post hoc test of the area of the fruit inoculated with different isolates of Agroathelia rolfsii compared to the control.

Figure 5.

Symptoms development in oil palm bunches inoculated in the field with seven isolates of Agroathelia rolfsii obtained from oil palms fruit affected by WFR the northern zone of Colombia.

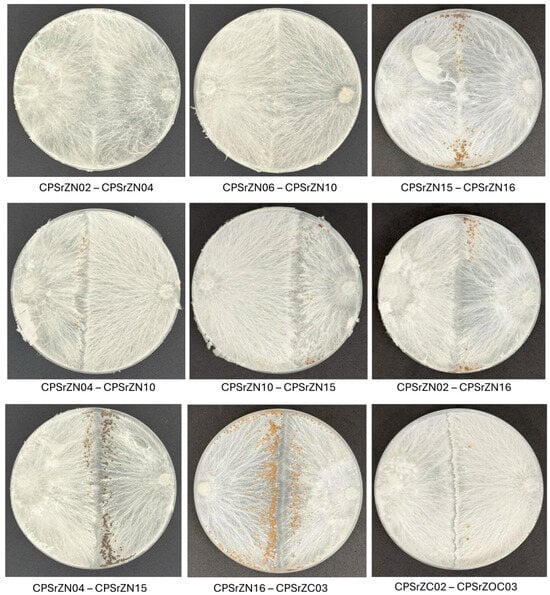

3.4. Mycelial Compatibility Assessment

Moderate to strong incompatible (antagonistic) reactions were observed in most isolate pairings, primarily those from different geographical areas. Compatible reactions occurred mainly between isolates from the same or nearby locations (Table 4). Incompatibility reactions became evident on the tenth day of incubation and were characterized by well-defined zones in both hyphal growth and sclerotia distribution. Of the 66 interactions evaluated, 49 cases of strong incompatibility (grade 3) were recorded, in which lines of growth inhibition, a clear separation in mycelial development, and the formation of larger sclerotia, concentrated toward the edge of mycelial growth before the contact zone, were observed. In cases of moderate incompatibility (grade 2), distinct separation lines were observed, accompanied by visible color changes in the mycelium on the back of the Petri dishes, as well as partial separation during sclerotia formation. Weak incompatibility reactions (grade 1) were characterized by faint demarcation lines, with mycelia growing very close together and minimal separation between sclerotia. Finally, four compatible interactions (grade 0) were observed, in which no separation lines were detected, and the colonies were fused entirely, consistent with the self-crosses (Figure 6, Table 5).

Table 4.

Somatic compatibility between Agroathelia rolfsii isolates obtained from bunches affected with withe fruit rot from the oil palm plantation of Colombia.

Figure 6.

Mycelial compatibility reactions between isolates of Agroathelia rolfsii. Normal intermingling and barrage formation between compatible interaction (First line), moderate interaction (Second line) and incompatible interaction (Third line) isolates. 0 = compatible, 1 = weak interaction, 2 = moderate interaction, 3 = strong interaction.

Table 5.

Information on the species used in the phylogenetic analysis.

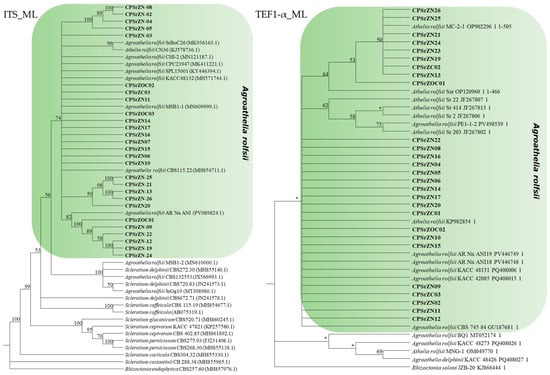

3.5. Molecular Identification

The length of the gene sequences of the ITS and TEF1-α regions of the isolates obtained in this study was approximately 643 and 505 bp, respectively. The corresponding accession numbers for both regions are presented in Table 1. A comparative analysis using BLAST, based on the GenBank database, identified isolates with identity levels ranging from 97% to 100% for the ITS region, which coincided with the species Agroathelia rolfsii (Sacc.) Redhead & Mullineux, 2023 (syn. Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc., 1911). Similarly, the TEF1-α region showed identity levels ranging from 99% to 100% with the same species. For the construction of the phylogenetic tree, reference sequences available at NCBI were compiled (Table 5). Phylogenetic analysis based on the ITS region revealed that the isolates obtained in this study clustered within a well-supported monophyletic clade corresponding to the A. rolfsii (=S. rolfsii) species complex. These isolates are closely grouped with multiple reference sequences from GenBank, such as CBS 115.22, SPL15001, KACC48132, and CPC23947, with bootstrap support greater than 74% confirming their taxonomic identity within this complex (Figure 7). However, several distinct subclades were observed among the isolates, indicating notable intraspecific genetic diversity. Similarly, the sequences of the TEF1-α region showed consistent clustering with different isolates of Agroathelia rolfsii, which reinforces the molecular identification of the isolates. Notable sub-clades were also observed, suggesting moderate intraspecific variation. It should be noted that for this gene region, there were not enough sequences available in the NCBI database to perform a more robust comparison. The TEF1-α data support the ITS results, confirming the taxonomic placement of the isolates within S. rolfsii/A. rolfsii and highlighting underlying genetic variability within the group.

Figure 7.

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic trees based on the ITS and TEF1-α regions of rDNA from species of the genus Agroathelia. Isolates obtained in this study are indicated in bold. Bootstrap support values greater than 50% are indicated at the nodes, whereas values lower than 50% are represented with “*”. Rhizoctonia endophytica (MH857976.1) was used as the outgroup for the ITS tree, and Rhizoctonia solani (KJ866444.1) for the TEF tree.

4. Discussion

Through this study, the pathogenic association was confirmed, and 30 isolates of Agroathelia rolfsii (Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc. 1911) from the northern, central, and southwestern regions of Colombia were identified by their morphological, molecular, and pathogenic characteristics. This pathogen was identified as the causal agent of white fruit rot disease (WFR) in interspecific hybrid OxG cultivars. This microorganism is a cosmopolitan soil-borne pathogen with a broad host range, including vegetables, legumes, forest cereals, and flowers [27]. They generally cause root, stem, and fruit diseases under warm and humid conditions, especially in semiannual crops [11]. Environmental conditions were characterized by high temperatures (27–35 °C), relative humidity above 60%, acidic soils, and intermediate soil moisture levels close to 70% [28], similar to those recorded at the sampling sites, which favor the development of the microorganism [28,29]. In bananas, a long-cycle crop, it has been reported to cause rot in the corm, pseudostem, and pods, as well as leaf yellowing [30] The effects of the pathogen on yield losses depend on the crop, age, disease incidence, and severity. Yield losses of up to 60% have been recorded in tomatoes [11], 15 to 70% in peanuts [31], 4 to 76% in beans [32], and more than 50% in sugar beets [33]. Although losses caused by WFR have not been documented in oil palm, it is known that they can be favored by deficiencies in pollination, favorable climatic conditions, poor drainage [4] and deficiencies in harvest cycles. Therefore, knowledge of the causal agent is essential to establish effective management strategies.

Although the genus Agroathelia is generally associated with root and stem diseases that cause rot and wilting symptoms [31,32,34] the observations of the fungus Agroathelia rolfsii causing fruit rot are consistent with previous reports in crops such as jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus Lamarck) and squash (Cucurbita sp.) [9,13]. In these crops, disease development begins with an initial degradation of the fruit tissues, followed by white mycelial growth, and subsequently, the formation of white to brown sclerotia; however, these fruits are in direct contact with the soil, which likely facilitated infection. In contrast, oil palm bunches do not have direct contact with the soil, suggesting that other factors may contribute to pathogen dissemination. Agronomic activities such as artificial pollination, leaf pruning, and harvesting involve tools that could act as mechanical vectors because these have direct contact with the soil, enabling the spread of the pathogen [11,15]. Additionally, wind may contribute to dissemination by lifting and dispersing sclerotia [15].

Morphologically, under in vitro conditions, the pathogen exhibited characteristic features including white, cottony mycelium and abundant brown sclerotia, measuring 1.03 mm in diameter, in PDA culture medium, a finding similar to that observed by [31,35,36]. However, silky white or white to pale brown mycelia have been observed [35,36] Various sources have reported variations in sclerotia production, size, and shape [32,37,38,39]. In our study, it was observed that isolates from the Northern Palm Zone exhibited a higher number of sclerotia, ranging from 100 to 449 per plate, indicating some morphological differences compared to isolates from the other two palm zones. This coincides with the differences reported by [31] in Arachis hypogaea L. and [32,40] in beans. The production of sclerotia, specialized resistance structures, is a key aspect of the pathogen’s biology, enabling it to survive under adverse conditions and persist in the soil for extended periods due to its nutritional reserves [27,35,36]. These sclerotia also act as primary inoculum for the establishment of new infections in crops [36,41].

Furthermore, based on its morphological characteristics, the pathogen was preliminarily identified as a species of the genus Agroathelia [42,43]. The microscopic observations of A. rolfsii development revealed sterile mycelium with clamp connections, thicker hyphae, and subsequent development of sclerotia that were initially white to beige in color, and in more mature stages, caramel to brown. This is consistent with reports from other authors, who describe it as having the typical characteristics of fungi previously called Agonomycetes or sterilia mycelium: hyaline, septate, with the formation of clamp connections, followed by the formation of differential sclerotia resulting from the union of melanized hyphae [33,44].

The mycelial compatibility interactions observed in this study among all paired isolates (except self-pairs) indicate that isolates of Agroathelia rolfsii from oil palm exhibit different levels of compatibility, demonstrating a high frequency of strong incompatibility interaction, particularly among isolates from geographically distant locations. In contrast, isolates from the same or nearby areas showed greater mycelial compatibility. This trend is consistent with observations reported in other studies on genetic variability and compatibility in S. rolfsii (syn. A. rolfsii) populations, where divergence in mycelial compatibility groups (MCGs) has frequently been associated with geographic distance, although not always in a strict manner [12]. Such studies have documented diversity among Sclerotium isolates from very widely geographic areas and diverse host sources, where many of the reported MCGs were unique, single-member groups and isolates from different MCGs were genetically distant [19,45]. This genetic variation has also been reported among isolates from a restricted region with multiple hosts [46,47]. Furthermore, even within a single region and a single host, different MCGs have been identified, and most isolates within the same MCG were clonal [10,48,49]. Similar patterns have been reported across different regions when only a single host was considered [12]. Even though the primary aim of this study was to identify the causal agent, further research is required to evaluate the compatibility among all isolates obtained and to increase the number of isolates from different localities in order to determine their relevance in the epidemiology of the disease.

Agroathelia rolfsii is a fungus of the Basidiomycota division, Agaricomycetes class, Amylocorticiales order, and Amylocorticiaceae family [44]. It was initially described as Sclerotium rolfsii by Pier Saccardo in 1911, constituting its basionym. Later, in its teleomorphic state, it was called Corticium rolfsii and subsequently renamed Athelia rolfsii [50,51] However, recent phylogenetic analysis has confirmed its belonging to the Amylocorticiales order, not to Atheliales, as proposed by Patrick Talbot [52].

Despite having defined morphological characteristics, they are not sufficient for identification to the species level. For this reason, the use of molecular tools is essential to complement identification, through partial sequencing of conserved DNA regions, a strategy that has proven effective for the correct characterization of various phytopathogens [53]. Phylogenetic analysis of ITS-rDNA and TEF1-α sequences revealed that the fungal isolates obtained in this study were grouped into a common clade with reference sequences of Agroathelia rolfsii retrieved from GenBank (Figure 7), thus confirming their identity as A. rolfsii (=S. rolfsii), based on morphological, cultural, and molecular information. Molecular characterization of S. rolfsii through ITS region sequencing has been previously reported in various crops [9,30,32,34,37,54] Furthermore, intraspecific variability has been documented in the ITS, TEF1-α, and RPB2 regions, supporting the use of multiple markers for more accurate identification [10,55,56,57].

In the pathogenicity assay of A. rolfsii, performed on detached tissue, inoculated oil palm fruits developed symptoms like those observed on naturally affected plants. The reisolates showed the same morphological characteristics as the original isolates from the diseased plants, thus fulfilling Koch’s postulates. This result is consistent with that reported in other studies involving this pathogen [13,56,58]. However, although all isolates were pathogenic, variability in their aggressiveness was evident, reflected in the number of affected fruits and the area involved. This behavior is consistent with that described by [59] and [60] in inoculations with different S. rolfsii isolates in Jerusalem artichoke and peanut crops, respectively. The findings of these studies showed that the incidence rate varied among isolates, suggesting that this pathogen exhibits a wide range of virulence. Additionally, the CPSrZN06 isolate with the greater severity observed is one of the isolates with a larger sclerotia size, which coincides with that reported by [32], where it suggests a direct proportional relationship between sclerotia size and disease severity. The identification of Agroathelia rolfsii obtained from fruits affected by white fruit rot in oil palm is the first step toward continuing the evaluation of management strategies and reducing the spread of the problem in the oil palm production system.

In addition, it is advisable to continue conducting studies to elucidate the pathogenesis of Agroathelia rolfsii in oil palm, with emphasis on the role of oxalic acid, considering its involvement in the degradation of the host cell wall and the suppression of defense responses [61]. Further research should also clarify molecular interactions between the pathogen and host [45,47,48] and identify the epidemiology of this pathogen in order to design a sustainable management strategy against this destructive fungal pathogen.

Author Contributions

G.A.S., L.d.M.A.-S. and L.F.Z.-P. planned and designed the study. G.A.S., L.d.M.A.-S., Y.A.M.-G., L.F.Z.-P., H.C.M.-C., J.L.P., A.M.-R., C.S.O.-S. and D.A.G.-R. performed sequence assembly and evaluation tests. L.E.V.-M. performed experimental design and data analysis. G.A.S., L.d.M.A.-S., Y.A.M.-G. and A.M.-R. wrote the manuscript, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by The Oil Palm Promotion Fund FFP, grant number 2020205, administered by Fedepalma.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Cenipalma and the Palm Oil Promotion Fund (FFP), administered by Fedepalma, for funding this work. We thank the Colombian professionals, technicians, and palm growers for their support in conducting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- SISPA Producción y Rendimiento, Historico. Available online: https://sispaplus.fedepalma.org/Reportes_Publicos/Produccion_Rendimiento (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Bojacá, C.R. Parte 1 Variabilidad Climática En Las Zonas Palmeras de Colombia ¿cómo Se Ha Comportado La Temperatura Durante Los Últimos 30 Años. Available online: https://elpalmicultor.com/variabilidad-climatica-zonas-palmeras-colombia/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- IDEAM Sistema de Información Para La Gestión de Datos Hidrológicos y Meteorológicos. Available online: https://www.ideam.gov.co/dhime (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Maizatul-Suriza, M.; Suhanah, J.; Madihah, A.Z.; Idris, A.S.; Mohidin, H. Phylogenetic and Pathogenicity Evaluation of the Marasmioid Fungus Marasmius palmivorus Causing Fruit Bunch Rot Disease of Oil Palm. For. Pathol. 2021, 51, e12660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pong, V.M.; Zainal Abidin, M.A.; Almaliky, B.S.A.; Kadir, J.; Wong, M.Y. Isolation, Fruiting and Pathogenicity of Marasmiellus palmivorus (Sharples) Desjardin (comb. prov.) in Oil Palm Plantations in West Malaysia. Pertanika J. Trop. Agric. Sci. 2012, 35, 37–48. Available online: http://psasir.upm.edu.my/id/eprint/19208/1/80.%20Isolation%2C%20Fruiting%20and%20Pathogenicity%20of%20Marasmiellus%20palmivorus.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Almaliky, B.S.A.; MiorAhmad, Z.A.; Kadir, J.; Mui, W. Pathogenicity of Marasmiellus palmivorus (Sharples) Desjardin Comb. Prov. on oil palm Elaeis guineensis. Wulfenia 2012, 19, 144–160. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263582258_Pathogenicity_of_Marasmiellus_palmivorus_Sharples_Desjardin_comb_Prov_on_Oil_Palm_Elaeis_guineensis (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Balanagouda, P.; Sridhara, S.; Shil, S.; Hegde, V.; Naik, M.K.; Narayanaswamy, H.; Balasundram, S.K. Assessment of the Spatial Distribution and Risk Associated with Fruit Rot Disease in Areca catechu L. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, P.H.D.; Mussi-Dias, V.; Freire, M.D.; Carvalho, B.M.; da Silveira, S.F. Diagrammatic Scale of Severity for Postharvest Black Rot (Ceratocystis paradoxa) in Coconut Palm Fruits. Summa Phytopathol. 2017, 43, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevakumar, S.; Yadav, V.; Tejaswini, G.S.; Janardhana, G.R. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Sclerotium rolfsii. Associated with Fruit Rot of Cucurbita maxima. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2015, 145, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, I.; Matsumoto, N. Population Structure of Sclerotium rolfsii in Peanut Fields. Mycoscience 2000, 41, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kator, L.; Yula Hosea, Z.; Daniel Oche, O. Sclerotium rolfsii; Causative Organism of Southern Blight, Stem Rot, White Mold and Sclerotia Rot Disease. Sch. Res. Libr. Ann. Biol. Res. 2015, 6, 78–89. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343268195_Sclerotium_rolfsii_Causative_organism_of_southern_blight_stem_rot_white_mold_and_sclerotia_rot_disease (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Remesal, E.; Jordán-Ramírez, R.; Jiménez-Díaz, R.M.; Navas-Cortés, J.A. Mycelial Compatibility Groups and Pathogenic Diversity in Sclerotium rolfsii Populations from Sugar Beet Crops in Mediterranean-Type Climate Regions. Plant Pathol. 2012, 61, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, F.E.; Islam, M.; Alam, M.; Islam, N.; Tipu, M.M.H.; Khatun, F.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Sarker, S. First Report of Athelia rolfsii on Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus). Australas. Plant Dis. Notes 2021, 16, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdary, G.B.S.M.; Jameema, G.; Charishma, K.V. Collar and Stem Pathogen Sclerotium rolfsii: A Review. Plant Arch. 2024, 24, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okon, O.G.; Uwaidem, Y.I.; Rhouma, A.; Antia, U.E.; Okon, J.E.; Archibong, B.F. Unraveling the Biology, Effects and Management Methods of Sclerotium rolfsii Infection in Plants for Sustainable Agriculture. Eur. J. Biol. Res. 2025, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, D.C.; Hormaza, P.A.; Moreno, L.P.; Ruíz, R. Generalidades Sobre La Morfología y Fenología de La Palma de Aceite; Centro de Investigación en Palma de Aceite: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012; ISBN 978-958-8360-40-9. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, D.; Tunali, B.; Nelson, L.R. Occurrence of Fungal Endophytes in Species of Wild Triticum. Crop Sci. 1999, 39, 1507–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punja, Z.K. Hyphal Interactions and Antagonism Among Field Isolates and Single-Basidiospore Strains of Athelia (Sclerotium) rolfsii. Phytopathology 1983, 73, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaskaveg, J.E.; Gilbertson, R.L. Vegetative Incompatibility between Intraspecific Dikaryotic Pairings of Ganoderma lucidum and G. Tsugae. Mycologia 1987, 79, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. ISBN 0-12-372180-6. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A Method for Designing Primer Sets for Speciation Studies in Filamentous Ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edler, D.; Klein, J.; Antonelli, A.; Silvestro, D. RaxmlGUI 2.0: A Graphical Interface and Toolkit for Phylogenetic Analyses Using RAxML. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 12, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, A.F.; Millan, E.S.; Ruiz, R.; Romero, H.M. Criterios de Cosecha En Cultivares Híbrido: Características Que Evalúan El Punto de Cosecha En Palma de Aceite, 2nd ed.; Federación Nacional de Cultivadores de Palma de Aceite de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020; ISBN 978-958-8360-75-1. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, H.M.; Ruiz-Romero, R.; Caicedo-Zambrano, A.F.; Ayala-Diaz, I.; Rodríguez, J.L. Determining the Optimum Harvest Point in Oil Palm Interspecific Hybrids (O × G) to Maximize Oil Content. Agronomy 2025, 15, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, P.; Shrestha, S.M.; Manandhar, H.K.; Marahatta, S. Morphology and Cross Infectivity of Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc. Isolated from Different Host Plants in Nepal. J. Agric. Environ. 2022, 23, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablormeti, F.K.; Souza, P.G.C.; Awuah, R.T.; Kwoseh, C.K.; Agbetiameh, D.; Kena, A.W.; Aidoo, K.A.S.; Lutuf, H.; Sossah, F.L.; da Silva, R.S.; et al. Modeling Global Habitat Suitability of Agroathelia rolfsii Causing Sclerotium Wilt Disease of Tomato with Emphasis on Ghana. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z.; Cai, G.; Zhang, F.; Yang, S.; Cheng, M.; Lu, W.; Chen, Y. First Report of Agroathelia (syn. Sclerotium) rolfsii Associated with Southern Blight Disease of Daphne tangutica (Gansu Ruixiang) in China. Plant Dis. 2025, 109, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acabal, B.D.; Dalisay, T.U.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W.; Cumagun, C.J.R. Athelia rolfsii (=Sclerotium rolfsii) Infects Banana in the Philippines. Australas. Plant Dis. Notes 2019, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, P.N.; Meena, A.K.; Ram, C. Morphological and Molecular Diversity in Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc., Infecting Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Discov. Agric. 2023, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparu, P.; Acur, A.; Kato, F.; Acam, C.; Nakibuule, J.; Nkuboye, A.; Musoke, S.; Mukankusi, C. Morphological and Pathogenic Characterization of Sclerotium rolfsii, the Causal Agent of Southern Blight Disease on Common Bean in Uganda. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 2130–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhaoui, A.; Legrifi, I.; Taoussi, M.; Mokrini, F.; Tahiri, A.; Lahlali, R. Sclerotium rolfsii-Induced Damping off and Root Rot in Sugar Beet: Understanding the Biology, Pathogenesis, and Disease Management Strategies. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 134, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Huang, J.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Q. First Report of Southern Blight Caused by Athelia rolfsii on Pepper in Yiyang, China. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, C.N.; Mendes, R.; Kruijt, M.; Raaijmakers, J.M. Genetic and Phenotypic Diversity of Sclerotium rolfsii in Groundnut Fields in Central Vietnam. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Huang, C.H.; Vallad, G.E. Mycelial Compatibility and Pathogenic Diversity among Sclerotium rolfsii Isolates in the Southern United States. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 1685–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.K.; Mahmud, N.U.; Gupta, D.R.; Surovy, M.Z.; Rahman, M.; Islam, M.T. Characterization of Sclerotium rolfsii Causing Root Rot of Sugar Beet in Bangladesh. Sugar Tech 2021, 23, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, I.; Chiharu, M.; Naoyuki, M.; Kazunari, Y. Variation in Sclerotium rolfsii Isolates in Japan. Mycoscience 1998, 39, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepero de García, M.C.; Restrepo, S.; Franco-Molano, A.E.; Vargas, N. Biología de Hongos; Ediciones Uniandes-Universidad de los Andes: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012; ISBN 978-958-695-701-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Sun, F.; Deng, D.; Zhu, X.; Duan, C.; Zhu, Z. First Report of Southern Blight of Mung Bean Caused by Sclerotium rolfsii in China. Crop Prot. 2020, 130, 105055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamja, T.; Bora, S.; Tabing, R.; Basar, E.; Kotoky, U. Incidence, Symptomology, Morpho-Molecular Characterization of Agroathelia rolfsii (Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc.): The Causal Agent of Basal Rot in Chabaud Carnation. Indian J. Agric. Res. 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, J. Southern Blight, Southern Stem Blight, White Mold. Plant Health Instr. 2001, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordue, J.E.M. Corticium rolfsii. [Descriptions of Fungi and Bacteria]; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 1974; p. Sheet 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevakumar, S.; Savitha, A.S.; Danteswari, C.; Sarma, P.V.S.R.N.; Renuka, M.; Ajithkumar, K.; Mahesh, M.; Sampath Kumar, P.T.S. Morpho-Molecular Characterization of Agroathelia rolfsii Causing Leaf Blight of Sacred Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 140, 102899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punja, Z.K.; Sun, L.J. Genetic Diversity among Mycelial Compatibility Groups of Sclerotium rolfsii (Teleomorph Athelia rolfsii) and S. delphinii. Mycol. Res. 2001, 105, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, A.J.; Herselman, L.; Pretorius, Z.A. Genetic Variability within and among Mycelial Compatibility Groups of Sclerotium rolfsii in South Africa. Phytopathology 2000, 90, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, A.J.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Van Wyk, P.S. Mycelial Compatibility Groups of Sclerotium rolfsii in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2002, 68, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adandonon, A.; Aveling, T.A.S.; Van Der Merwe, N.A.; Sanders, G. Genetic Variation among Sclerotium Isolates from Benin and South Africa, Determined Using Mycelial Compatibility and ITS RDNA Sequence Data. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2005, 34, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalim, F.A.; Starr, J.L.; Woodard, K.E.; Segner, S.; Keller, N.P. Mycelial Compatibility Groups in Texas Peanut Field Populations of Sclerotium rolfsii. Phytopathology 1995, 85, 1507–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlton, C.E.; Levesque, C.A.; Punja, Z.K. Genetic Diversity in Sclerotium (Athelia) rolfsii and Related Species. Phytopathology 1995, 85, 1269–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.C.; Kimbrough, J.W. Systematics and Phylogeny of Fungi in the Rhizoctonia Complex. Bot. Gaz. 1978, 139, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, J.; Quesada-Ocampo, L.M. Diagnostic Guide for Sclerotial Blight and Circular Spot of Sweetpotato. Plant. Health. Prog. 2024, 25, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Harrington, T.C.; Gleason, M.L.; Batzer, J.C. Phylogenetic Placement of Plant Pathogenic Sclerotium Species among Teleomorph Genera. Mycologia 2010, 102, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevakumar, S.; Janardhana, G.R. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Sclerotium rolfsii Associated with Leaf Blight Disease of Psychotria nervosa (Wild Coffee). J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 98, 351–354. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301589890_Morphological_and_molecular_characterization_of_Sclerotium_rolfsii_associated_with_leaf_blight_disease_of_Psychotria_nervosa_Wild_coffee (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Okabe, I.; Arakawa, M.; Matsumoto, N. ITS Polymorphism within a Single Strain of Sclerotium rolfsii. Mycoscience 2001, 42, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Qiu, H.; Meng, X.; Li, S.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cai, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M.; Duan, Y. Risk Assessment and Molecular Mechanism of Sclerotium rolfsii Resistance to Boscalid. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 200, 105806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejaswini, G.S.; Mahadevakumar, S.; Sowmya, R.; Deepika, Y.S.; Meghavarshinigowda, B.R.; Nuthan, B.R.; Sharvani, K.A.; Amruthesh, K.N.; Sridhar, K.R. Molecular Detection and Pathological Investigations on Southern Blight Disease Caused by Sclerotium rolfsii on Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata): A New Record in India. J. Phytopathol. 2022, 170, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.E.; Dey, T.K.; Hossain, D.M.; Nonaka, M.; Harada, N. First Report of White Mould Caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum on Jackfruit. Australas. Plant Dis. Notes 2015, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennoi, R.; Jogloy, S.; Saksirirat, W.; Patanothai, A. Pathogenicity Test of Sclerotium rolfsii, a Causal Agent of Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.) Stem Rot. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2010, 9, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivalingappa, H.; Ashtaputre, S.A.; Jahagirdar, S.; Rao, M.S.L.; Motagi, B.N.; Jones, P.; Mahesha, H.S.; Raghunandhan, A.; Shivakumara, K.T. Deciphering the Morphological and Pathogenic Variability among Sclerotium rolfsii: A Causal Agent of Groundnut Stem Rot Disease. Phytoparasitica 2025, 53, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Lal, M.; Sagar, S.; Sharma, S.; Meena, A.L.; Singh, R.K. Variability in Morphology, Oxalic Acid Production and Mycelial Compatibility Grouping Among Sclerotium rolfsii Isolates Causing Southern Blight Disease. Plant Pathol. 2025, 74, 2272–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.