Abstract

Humans are constantly exposed to micromycetes, especially filamentous fungi that are ubiquitous in the environment. In the presence of risk factors, mostly related to an alteration of immunity, the non-dermatophyte fungi can then become opportunistic pathogens, causing superficial, deep or disseminated infections. With new molecular tools applied to medical mycology and revisions in taxonomy, the number of fungi described in humans is rising. Some rare species are emerging, and others more frequent are increasing. The aim of this review is to (i) inventory the filamentous fungi found in humans and (ii) provide details on the anatomical sites where they have been identified and the semiology of infections. Among the 239,890 fungi taxa and corresponding synonyms, if any, retrieved from the Mycobank and NCBI Taxonomy databases, we were able to identify 565 moulds in humans. These filamentous fungi were identified in one or more anatomical sites. From a clinical point of view, this review allows us to realize that some uncommon fungi isolated in non-sterile sites may be involved in invasive infections. It may present a first step in the understanding of the pathogenicity of filamentous fungi and the interpretation of the results obtained with the new molecular diagnostic tools.

1. Introduction

It is estimated that there are between 1.5 and 5 million fungal species on Earth, and about 100,000 species are currently described [1,2]. Of these species, only a few hundred have the capacity to infect humans [3]. Humans are constantly exposed to potential fungal pathogens, as they are part of their normal flora and that of soil, water and air [3]. Moulds are a part of the vast kingdom of fungi alongside yeasts, mushrooms, polypores, plant parasitic rusts and smuts, microsporidia and Pneumocystis. Filamentous fungi are ubiquitous in the environment and can lead to opportunistic diseases presenting as superficial, invasive or disseminated infections. The number of described species is constantly increasing, probably due to the popularisation of DNA-based diagnostic tools, which now allow the distinction between close taxa and the identification of fungi, even in small quantities [1,4]. The taxonomy of fungi is also in constant evolution with the “one fungus, one name” nomenclature and integrative taxonomy approach combining genomics, morphology and ecology [1,5]. In recent years, epidemiological changes in invasive fungal diseases have been observed, new risk factors have emerged, and the number of patients at risk of developing these infections is also increasing [6,7]. Medical mycology is, therefore, a constantly evolving dynamic. Aspergillus, Penicillium, mucorales and dematiaceous fungi are the main filamentous fungi taxa involved in human diseases. Current reviews mainly focused on these taxa [3,8,9]. However, other, rarer species of moulds can emerge in specific infection sites, such as Paecilomyces variotii or Purpureocillium lilacinum in sino-pulmonary fungal infections, and should not be overlooked [10].

In this review, we offer an overview, as of 16 June 2020, of the filamentous fungi identified in humans by culture and nucleotide analyses associated or not with histopathology. We also provide information on the organs where these micromycetes are isolated and on the semiology of the infections. We have chosen to divide our review into two approaches. First, we describe the taxa of interest and indicate their preferred site of infection. We then described which filamentous fungi were involved at each major anatomical site.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Review and Database Creation

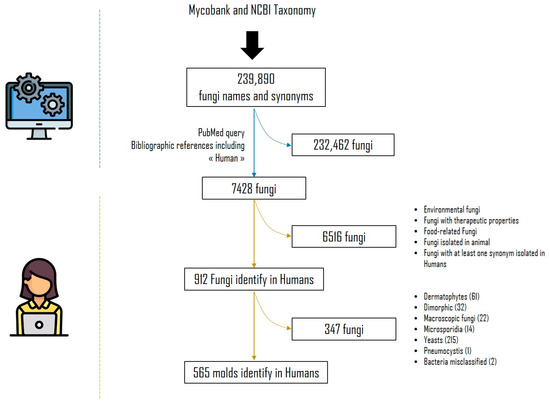

First, all fungi names and synonyms were collected on both Mycobank (https://www.mycobank.org/, accessed on 15 November 2019) and NCBI Taxonomy (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/taxonomy, accessed on 15 November 2019) that represent the state of the art of taxonomy of microfungi, updated on 15 November 2019. From Mycobank, the downloaded fungi taxon names and synonyms were provided in the worksheet https://www.MycoBank.org/images/MBList.zip accessed on 15 November 2019. From NCBI Taxonomy, the query used was Fungi[subtree] AND species[rank] AND specified[prop]. Python script using the Biopython package [11] was also implemented to fetch synonyms from NCBI Taxonomy. We have aggregated and deduplicated these two fungi name listings in order to obtain a single list of 239,890 fungi taxa and corresponding synonyms, if any (Figure 1). For each fungus name in the list, we used a Python script and Biopython package [11] to query PubMed to find bibliographic references that mention the fungi name or its synonyms associated with the term “human” in the article title (TI), abstract (AB), author-supplied keywords (Other Term (OT)) or the Medical Subject Headings' (MeSH) terms. The syntax of the queries was dynamically built using this pattern (fungi_name_or_synonyms [TIAB] OR fungi_name_or_synonyms[OT] OR fungi_name_or_synonyms[MeSH]) AND (“Human”[TIAB] OR “Human”[OT] OR “Humans”[MeSH]). Based on the query performed on 15 November 2019, 7428 fungi taxa were found with at least one PubMed reference.

Figure 1.

Systematic literature review flowchart.

An MS Access® database (Access 2013, Microsoft) was set up on 16 June 2020, with these 7428 recorded fungi names. Using this relational database management system, a link for each taxa corresponding to the query described above gave access to the relevant PubMed references and made it possible to study them one by one in order to identify and collect the relevant information.

2.2. Manual Database Incrementation

In the MS Access database (MS Access 2013 TM, Microsoft), each of the 7428 fungi had a record from a page linked to the PubMed-relevant references. For each PubMed reference, an analysis of the title and/or abstract and/or whole paper was performed manually to ensure that it was isolated from humans. This process was time-consuming. Only references present in PubMed before 16 June 2020 were taken into account in order to have the same PubMed content for each fungal species.

After analysis, 6516 fungal taxa that were ultimately not found in humans were excluded. They included fungi of food, therapeutic or environmental interest, or those involved in domesticated animal diseases. Synonyms, when not isolated from humans but associated with a species involved in humans, were also excluded. We focused on non-dermatophytes moulds. In fact, yeasts, microsporidia, dimorphic fungi, dermatophytes and Pneumocystis isolated in humans were also excluded.

We analysed the titles and/or abstracts and/or full paper and/or supplementary data, when available, of 565 moulds fungal names and synonyms isolated in humans to complete information on the anatomical site involved and the semiologies of the associated infection by filling in the PubMed Unique Identifier (PMID) of the publication concerned. Only identifications by direct diagnosis were taken into account, including culture (followed by morphological, Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry or DNA sequence-based identification) associated or not with histopathological findings and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Publications reporting a species-level diagnosis based solely on histopathological examination or indirect methods results were excluded. The date of first publication, last publication and the name used was also reported in the software.

The anatomical sites included: systemic (isolated from blood, bone marrow, blood vessels/arteries or lymph nodes), central nervous system (isolated from cerebrospinal fluid or brain biopsy); ophthalmic systems (isolated from ocular samples, such as vitreous humour, corneal scrapings or lacrimal fluid); heart (isolated from cardiac specimens, e.g., valve or pericardial fluid); osteo-articular system (isolated from joint or bone samples); skeletal muscles (isolated from muscles); soft-tissue (isolated from soft-tissue); endocrine glands (isolated from adrenal, pituitary gland or thyroid); skin system (isolated from cutaneous or subcutaneous samples); otorhinolaryngeal sphere (isolated from nasal specimens, including sinuses, and throat specimens, including mouth, tongue, oesophagus, larynx, pharynx or trachea); auditory system (isolated from ear samples); dental (isolated from tooth root, dental pulp or anatomical structures directly in contact with the tooth in case of periodontitis, gingivitis, implant infection or abscess); pulmonary (isolated from the upper respiratory tract, e.g., sputum, lower respiratory tract, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, lung biopsy, bronchial brushing, bronchoscopic needle aspiration and bronchial aspirate, pleural fluid and mediastinal specimen); breast; urinary tract (isolated from the urinary tract including kidneys, ureters, bladder, urinary meatus and the prostate); genital (isolated from genitalia or related body fluids, both male and female, including penile and urethral samples); digestive system (isolated from stool samples or organs of the digestive system, including peritoneum, intestines, pancreas, spleen, gallbladder or appendix, but excluding the liver); hepatic (liver biopsy); and pregnancy (isolated from the placenta or foetus). When information on the anatomical site was provided, we added a degree of accuracy by specifying anatomical details or semiology of the associated infection (e.g., endophthalmitis for ocular sphere) by filling in the PMIDs. In brief, for each fungus with publications reporting having been identified in humans, the current name and dates of the first and last publications were completed by filling in a list of PMID for each anatomical site and the semiology of the associated infection.

2.3. Data Analysis

The MS Access® database (Access 2013, Microsoft) was converted into two Excel files (Excel 2013, Microsoft). In the first file, the number of PMIDs per taxa was calculated by the anatomical site where the fungi were isolated. In the second, the number of PMIDs per fungus was given for six major fungal categories (i.e., Aspergillus, dematiaceous, Fusarium, mucorales, Penicillium and Pseudallescheria/Scedosporium) according to the infections associated with the isolation of the fungus, as stated by the authors of the article. If more than one case was described in a publication with the same anatomical site, it counted as one publication because of a single PMID.

2.4. Taxonomy

Taxa were organised at the high-level classification into sections or species complexes based on https://www.aspergilluspenicillium.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2022) for Aspergillus spp. [12] and Penicillium spp. [13,14] and relevant publications for Fusarium spp. [15,16]. Mucorales and dematiaceous fungi were classified by genus [17,18].

2.5. Synonyms

We referred to the “current name” in Mycobank to identify the current name and the synonyms. The current name/synonym association was then checked by querying the PubMed database.

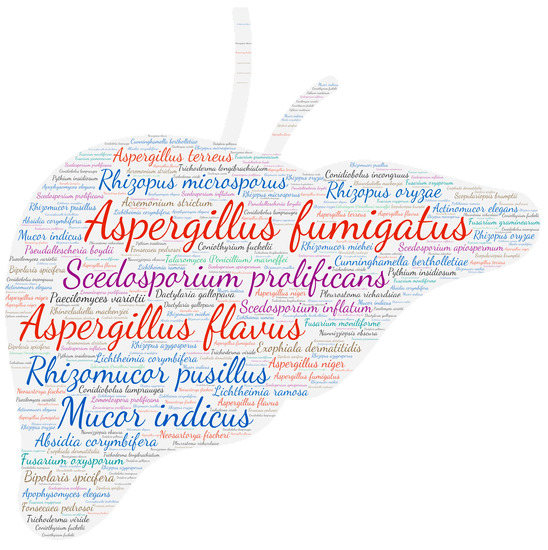

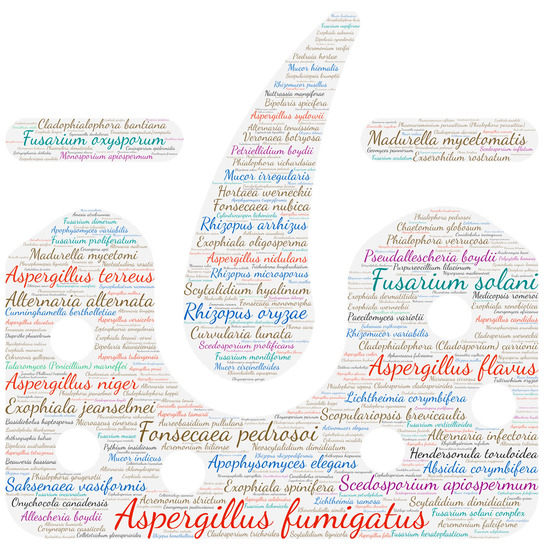

2.6. Figures

All figures were produced using the online tool, Wordart (https://wordart.com/). The size of the name of each species was proportional to the number of times it occurred in the database. The genus Aspergillus is represented in red, the dematiaceous fungi in brown, the mucorales in blue, the genus Fusarium in turquoise, the Scedosporium/Lometospora species complex in purple, the genus Penicillium in green and the others in black.

3. Results

3.1. Fungal Location by Focusing on the Predominant Genus

In total, 6913 articles/PMIDs were included. This bibliographical research identified 565 fungal species of 192 genera, which had been reported at least once in humans. The list of theses taxa is detailed in Table 1, with their former and current scientific name, if applicable. Briefly, there were 204 dematiaceous fungi, 81 Aspergillus spp., 25 Penicillium spp., 35 Fusarium spp., 45 mucorales, 14 of to the Scedosporium/Lomentospora complex, and 161 to other mould species distributed in 103 genera. The results obtained for each of these taxa will be presented below. Regarding the publications reporting the isolation of these micromycetes at all anatomical sites (a publication can be counted multiple times due to the possible report of multiple anatomical sites in the same publication), the leading genus was Aspergillus (total: 4401). The Fumigati and Flavi sections were the most recorded into this genus (total: 2671 and 865, respectively). In second place come the dematiaceous fungi (total: 1976), followed by the Scedosporium/Lomentospora complex (total: 1222), mucorales (total: 1089) and Fusarium (total: 713). Penicillium was rarely reported in human infections (total: 163).

Table 1.

Number of publications found by anatomical site and species. In the same publication (PMID), several anatomical sites of isolation could be found.

3.1.1. Aspergillus

Aspergillus species were the most frequent moulds isolated in human clinical samples. In this repertoire, the 81 Aspergillus species identified at least once in humans belong to 14 sections of the 20 described [19], as follows: Aspergillus, Candidi, Circumdati, Clavati, Cremei, Flavi, Flavipedes, Fumigati, Nidulantes, Nigri, Polypaecilum, Restricti, Terrei and Usti. As reported in the literature, the filamentous fungus mostly isolated from humans is Aspergillus fumigatus [20], followed by Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus terreus. The lung and respiratory tracts were the most common anatomical sites of infection, with a total of 1180 publications for A. fumigatus, 174 for A. flavus, 102 for A. niger and 81 publications for A. terreus. These fungi are indeed ubiquitous in the environment and are transmitted by the airways [21]. The results will be approached in terms of the Aspergillus section to rule out potential misidentifications related to morphological identification [4]. The anatomical site in the second position and concerning all the sections was the skin system. Cutaneous aspergillosis can be primary and can affect immunocompetent patients or can be secondary in cases of disseminated infection, predominantly in immunosuppressed patients [22,23,24]. The Nigri section has a tropism for the auditory system, with 79 publications, which has already been noted in the literature [25]. Regarding the clinical presentations involving the central nervous system or heart, the Fumigati section was predominantly represented (194 and 118 publications, respectively). The Fumigati, Flavi and Nigri sections had a predominantly ocular involvement, with 140, 93, and 36 publications, respectively.

3.1.2. Fusarium

The genus Fusarium includes at least 200 species, grouped into about ten phylogenetic species complexes [15,16,26]. In this review of the literature, only eight species complexes were found to have been isolated from humans: F. chlamydosporum species complex (FCSC), F. dimerum species complex (FDSC), F. incarnatum–F. equiseti species complex (FIESC), F. oxysporum species complex (FOSC), F. sambucinum species complex (FSAMSC), F. solani species complex (FSSC), F. fujikuroi species complex (FFSC) and Gibberella fujikuroi species complex (GFSC). Interestingly, looking at the Fusarium genus as a whole, three anatomical sites stand out: the ocular system (190 publications), the cutaneous system (233 publications) and systemic involvement (134 publications). This is consistent with the data in the literature reporting superficial cases, mainly keratitis and onychomycosis in immunocompromised or immunocompromised patients and disseminated infections in immunocompromised patients [27,28,29,30]. Species belonging to the FSSC are predominantly represented, which has previously been shown to be the most virulent Fusarium species complex in animal models [31].

3.1.3. Penicillium

The genus Penicillium is ubiquitous in the environment and is rarely involved in human infections. When found in superficial and aerial samples, they are often considered contaminants. In this literature review, only 163 publications reporting the isolation of these hyaline hyphomycetes in humans were found. One species has emerged since the 1990s and mainly affects humans with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): Talaromyces marneffei [32,33], and this is the predominant species within the genus Penicillium representing 54% of the publications (89/164). The members of the genus Penicillium are mostly reported in three anatomical sites: the pulmonary sphere (48 publications), the cutaneous system (23 publications) and systemic involvement (36 publications).

3.1.4. Mucorales

The order of the mucorales (previously Zygomyces) includes the hyaline pauciseptated filamentous fungi group, comprising 13 genera: Mucor, Lichtheimia, Rhizomucor, Rhizopus, Absidia, Syncephalastrum, Cunninghamella, Apophysomyces, Mycocladus, Saksenaea, Actinomucor, Thamnostylum and Thermomucor. All of these are implicated in human infections [34]. In this literature review, Rhizopus was the genus mostly involved in human infections, with Rhizopus oryzae (121 publications) (plus its synonym and current appellation Rhizopus arrhizus (53 publications)) leading the way, followed by Rhizopus microsporus (90 publications). Mucorales can be classified according to the primary route of infection: airborne, direct contact with contaminated devices or by trauma [34,35]. Here, we compare the number of publications reporting isolation in the skin system versus the respiratory system, including from the oto-rhino-laryngological sphere and pulmonary sphere: The genera Apophysomyces (54 versus 26 publications, respectively), Mucor (40 versus 18 publications, respectively) and Saksenaea (45 versus eight publications, respectively) are mostly isolated from the skin system and therefore transmitted by contact; the genera Cunninghamella (12 versus 52 publications, respectively), Rhizopus (75 versus 134 publications, respectively) and Rhizomucor (8 versus 31 publications, respectively) are mostly isolated from the oto-rhino-laryngological sphere and pulmonary system and are, therefore, airborne; finally, Lichtheimia (77 versus 74 publications, respectively) had a less obvious tropism for one or the other of these two systems. The cutaneous or respiratory tropism can be explained by the differences found in the sporangia of these genera [35]. In fact, the wet spores of the Mucor, Apophysomyces and Saksenaea species are probably not primarily dispersed by the air and transmitted by trauma [35,36]. On the contrary, the sporangiospores of Rhizopus and Rhizomucor species are small (less than 4 µm in diameter), dry and therefore easily airborne [37,38]. This morphological hypothesis does not explain everything because, similar to Mucor, Lichteimia have wet spores and yet they are equivalently reported in the lung and skin in this review.

3.1.5. Dematiaceous moulds

Dematiaceous fungi are also known as “black fungi” due to the predominance of melanin in their cell walls, which likely acts as a virulence factor. These darkly pigmented fungi are found on the soil surface, where they live as saprophytes but also sometimes as parasites of plants [39]. This review has highlighted 204 dematiaceous fungi species isolated from humans, belonging to 19 genera: Alternaria, Exophiala, Cladophialophora, Scopulariopsis, Curvularia, Phialemoniopsis, Phialemonium, Exserohilum, Microascus, Bipolaris, Chaetomium, Cladosporium, Ochroconis, Phaeoacremonium, Rhinocladiella, Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Phoma and Madurella. The genus Exophiala is the most represented. Contamination most often takes place through infection of a wound by a telluric strain or during a transcutaneous traumatism by means of a plant [40]. This explains the predominantly cutaneous location found in this review (1043 publications). Among the cutaneous affections, melanised fungi are responsible for chromoblastomycosis, which mainly affect individuals performing soil-related tasks [41], phaeohyphomycosis [42] and eumycotic myetoma [43]. Two synonyms species stand out for their tropism for the central nervous system, Cladiophialophora bantiana and Cladosporium trichoides, for which 51 publications and 30 publications, respectively, were found in this location.

3.1.6. Pseudallescheria/Scedosporium Species Complex (PSC)

Among the PSC, six genera were represented: Allescheria, Lomentospora, Monosporium, Petriellidium, Pseudallescheria and Scedosporium. These fungi are ubiquitous in the environment and can be found in soil, compost and polluted water [44]. Regarding current nomenclature and taxonomy, the Pseudallescheria/Scedosporium species complex includes the three major species isolated from humans: Scedosporium apiospermum, Scedosporium boydii, and Lomentospora prolificans, and four distinct species, namely Scedosporium aurantiacum (29 publications), Scedosporium dehoogii (2 publications), Scedosporium inflatum (86 publications) and Scedosporium minutisporum (1 publication) [45]. By grouping the publications concerning the main species and their synonyms, we find 468 publications reporting the isolation of Scedosporium apiospermum, 275 publications reporting the isolation of Scedosporium boydii and 261 publications concerning the isolation of Lomentospora prolificans in humans. In regard to locations, S. boydii and S. apiospermum are found in all anatomical sites, with a greater prevalence in the pulmonary sphere (72 and 94 publications, respectively) and the cutaneous system (79 and 110 publications, respectively). Scedosporium prolificans is mainly found in the pulmonary sphere (56 publications) and in systemic infections (52 publications).

3.1.7. Others

Among the moulds not classified in the five major genera, some present in the environment stands out for their ability to affect multiple organs, such as the members of the genus Acremonium, with Acremonium strictum (35 publications) and Acremonium kiliense (27 publications) in the lead, members of the genus Paecilomyces, with Paecilomyces variotii (53 publications), and members of the Trichoderma genus, with Trichoderma longibrachiatum in the lead (40 publications). Others have a cutaneous tropism. Hendersonula toruloidea is an opportunistic fungus which is almost exclusively responsible for skin infections (34/35 publications). Onychocola canadensis is found only on the skin system (17 publications) and is mostly responsible for onychomycosis (16 publications). Finally, some rarely reported species were exclusively found in the ocular area, often secondary to trauma, such as Arthrobotrys oligospora (one publication), Beauveria alba (one publication), Carpoligna pleurothecii (one publication), Cephaliophora irregularis (one publication), Cephalosporium niveolanosum (one publication), Colletotrichum coccodes (one publication), Colletotrichum dematium (seven publications), Edenia gomezpompae (one publication), Epicoccum nigrum (one publication), Glomerella cingulate (one publication), Laetisaria arvalis (one publication), Metarhizium robertsii (one publication), Microcyclosporella mali (one publication), Paecilomyces viridis (one publication), Papulaspora equi (one publication), Pestalotiopsis clavispora (one publication), Phaeoisaria clematidis (one publication), Podospora austroamericana (one publication), Pseudopestalotiopsis theae (one publication), Roussoella solani (one publication), Setosphaeria holmii (one publication), Stachybotrys eucylindrospora (one publication), Tintelnotia destructans (one publication) and Tritirachium roseum (one publication).

3.2. Fungal Location by Focusing on the Anatomical Site

Within the 19 anatomical sites, the semiology of infection was detailed for the six major categories of fungi involved in human pathologies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Anatomical sites and nosological framework of the different taxa. CNS: central nervous system; and ORL: oto-rhino-laryngological. The numbers in the table correspond to PMIDs.

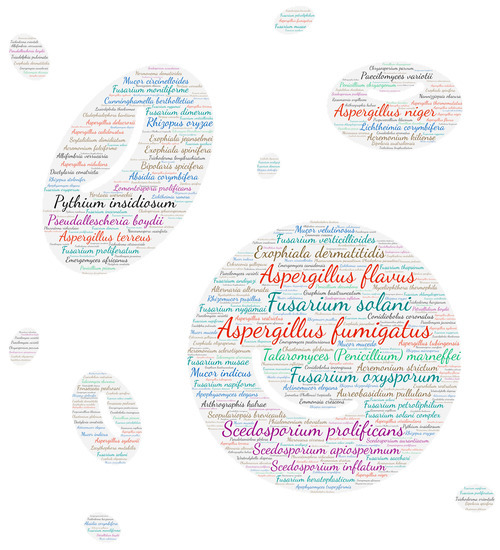

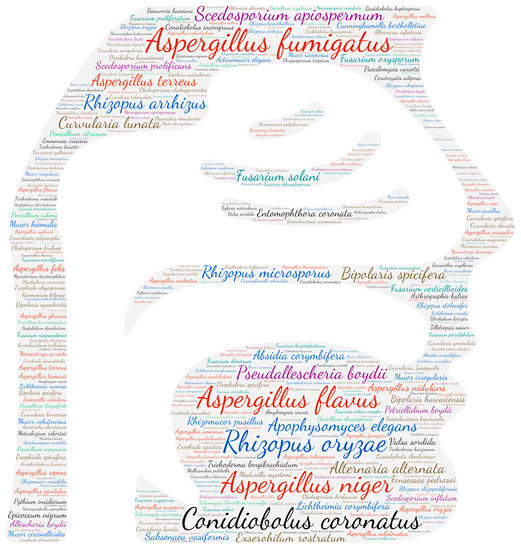

3.2.1. Systemic

Regarding systemic localisation (comprising fungaemia, aortitis, vasculitis, lymph node infection and bone marrow infection), there is a large majority of fungaemias. The genus Aspergillus was predominantly isolated from blood samples, with Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus predominating (Figure 2). It should be noted that the genus Fusarium was in second place with Fusarium solani. Aspergillus is rarely isolated from blood cultures and is usually in the case of infective endocarditis. This predominance of Aspergillus detection in systemic infections is explained by the use of new detection tools, including PCR.

Figure 2.

Wordcloud represents the species name involved in systemic infections. The size of the name of each species is proportional to the number of times it occurs in the repertoire.

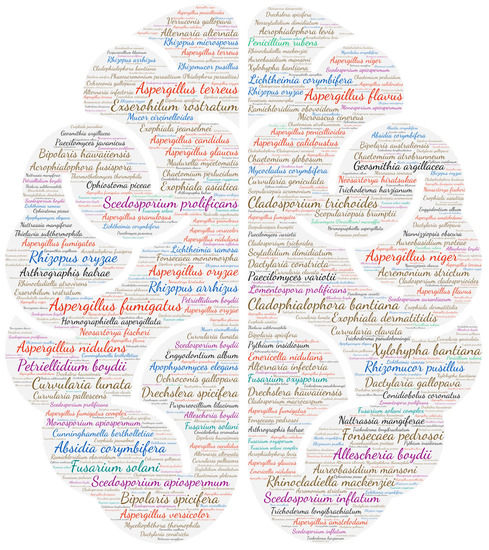

3.2.2. Central Nervous System

Three genera are mostly represented in central nervous system infections: Aspergillus, dematiaceous fungi and Pseudallescheria/Scedosporium species complex (Figure 3). The majority of infections occur as brain abscesses or meningitis. Figure 2 highlights several species of dematiaceous fungi. Exserohilum rostratum has been involved in iatrogenic meningitis outbreaks secondary to the use of contaminated injectable corticosteroids [46,47,48,49,50,51]. Cladophialophora bantiana is a dematiaceous mould that may infect immunocompetent patients (mainly farmers or residents of agricultural regions), whose reservoirs and modes of transmission are still poorly known [52]. Its neurotropism is highlighted by 51 publications concerning the CNS among a total of 84 in this review. Its synonym, Cladosporium trichoides, causes brain abscesses for which we have recovered 30 publications. Both are responsible for 81 publications reporting CNS involvement.

Figure 3.

Wordcloud represents the species name isolated in the central nervous system. The size of the name of each species is proportional to the number of times it occurs in the repertoire.

3.2.3. Ocular System

All categories of fungi can cause ocular damage. Indeed, as filamentous fungi are ubiquitous in the environment, this type of infection is frequently observed during injuries with plants. The genera Aspergillus with Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus terreus and Aspergillus niger and Fusarium with Fusarium solani and Fusarium oxysporum are predominant (Figure 4). In most cases, it can be keratitis (623 publications) or endophthalmitis (240 publications). The most described species that can cause both keratitis and endophthalmitis are Fusarium solani (85 and 21 publications, respectively), Aspergillus fumigatus (63 and 44 publications, respectively), Aspergillus flavus (52 and 16 publications, respectively), Scedosporium apiospermum (35 and 13 publications, respectively), Aspergillus niger (12 and 13 publications, respectively) and Pseudallescheria boydii (10 and 10 publications, respectively). The other species mostly involved in keratitis are Pythium insidiosum (31 publications), Fusarium oxysporum (21 publications), Lasiodiplodia theobromae (11 publications), Alternaria alternata (10 publications) and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (10 publications). It should be noted that ten species have been found in conjunctival infections: Aspergillus flavus (one), Aspergillus fumigatus (one), Aspergillus niger (four), Cephalosporium niveolanosum (one), Exophiala jeanselmei (one), Fonsecaea pedrosoi (one), Monosporium apiospermum (one), Neocucurbitaria keratinophila (one), Pseudallescheria boydii (one) and Scedosporium apiospermum (one).

Figure 4.

Wordcloud represents the species name isolated in the ocular system. The size of the name of each species is proportional to the number of times it occurs in the repertoire.

3.2.4. Auditory System

The genus Aspergillus is predominantly isolated from the auditory system, with Aspergillus niger in the lead, a member of the Nigri section known for its tropism for the auditory meatus [25]. Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus fumigatus come in second place (Figure 5). These fungi are responsible for fungal otomycosis in the majority of cases [53]. Interestingly, 29 publications reported the identification of Pseudallescheria/Scedosporium complex in the auditory system, including 18 reporting otomycosis. Scedosporium apiospermum was predominant, with ten publications reporting otomycosis, including two cases of malignant otitis externa [54,55] and one otitis complicated with temporomandibular arthritis [56]. Other species stand out in Figure 4, such as Absidia corymbifera, of which five publications report the involvement in otomycosis, including one case of malignant otitis externa [57] and a few cases of Penicillium otomycosis (six publications).

Figure 5.

Wordcloud represents the species name isolated in the auditory system. The size of the name of each species is proportional to the number of times it occurs in the repertoire.

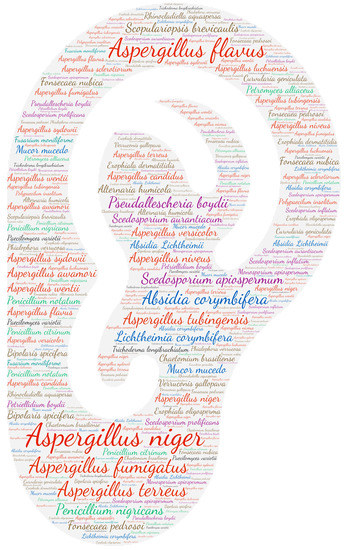

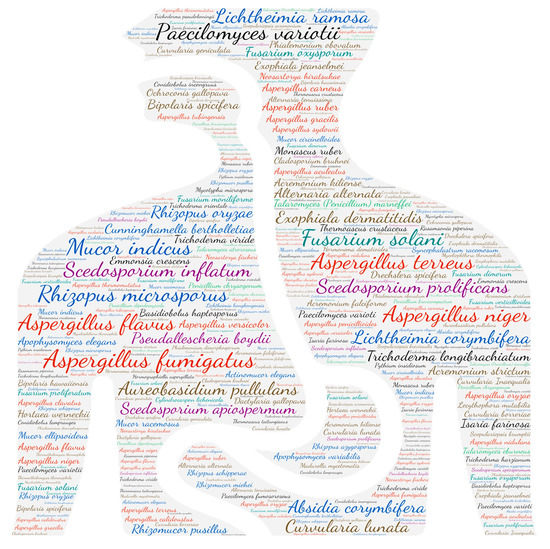

3.2.5. Oto-Rhino-Laryngeal System

It is not surprising that a majority of aspergillosis rhinosinusitis is recorded (282 publications) (Figure 6). This anatomical site also includes rhino-orbital, rhino-facial and rhino-orbito-cerebral involvement, which explains the strong representation of mucorales (170 publications). Rhizopus oryzae (heterotypic synonym Rhizopus arrhizus) is largely in the majority of the mucorales (38 publications), which is not surprising, given that it is the most common mucorale species worldwide [58]. Rhizopus oryzae is responsible for variable oto-rhino-laryngeal system infections, with a majority of rhino-orbito-cerebral infections (17 publications) followed by rhino-sinusitis (nine publications) and rhino-orbital involvement (seven publications). These rhino-orbito-cerebral lesions can also be caused by Aspergillus fumigatus (16 publications) and two other species of mucorales Rhizopus arrhizus (12 publications) and Apophysomyces elegans (11 publications). One fungus stands out, Conidiobolus coronatus, which is responsible for entomophthoromycosis and rhino-facial infections. C. coronatus is a widely distributed insect pathogenic fungus belonging to the class Zygomycetes and is rarely involved in human pathology. This mycosis is mainly tropical due to its tropism of plant detritus in very humid environments [59].

Figure 6.

Wordcloud represents the species name isolated in the oto-rhino-laryngeal sphere. The size of the name of each species is proportional to the number of times it occurs in the repertoire.

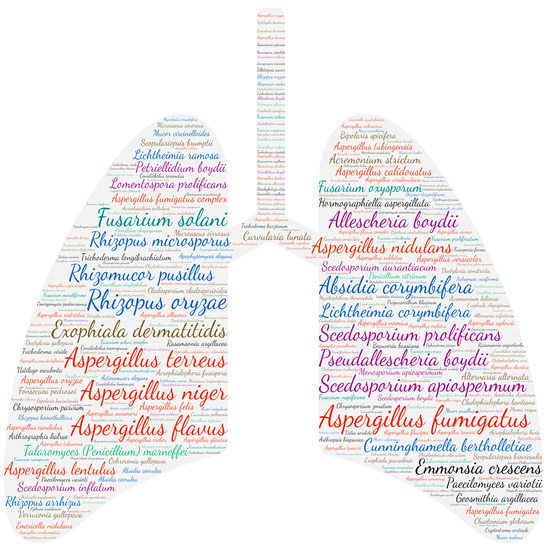

3.2.6. Pulmonary System

The respiratory system is the anatomical site most affected by fungal infections (4496 publications). It should be noted that no distinction was made between colonisation and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, which thus includes the respiratory isolation of Aspergillus species. Similar to Aspergilli, moulds are ubiquitous saprophytes in the environment. Their dispersion in the air is possible by the production of volatile spores, which ensures their presence in both indoor and outdoor environments [60,61]. Human contamination thus mainly occurs by inhaling the airborne conidia, with the lungs being the first to be exposed. We, therefore, note a wide variety of moulds responsible for lung damage (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Wordcloud represents the species name isolated in the pulmonary system. The size of the name of each species is proportional to the number of times it occurs in the repertoire.

3.2.7. Cardiac Involvement

Cardiac involvement was found among 13% (74/565) of the species described in this repertoire. These species belonged to the major taxa Aspergillus, Penicillium, Fusarium, mucorales, dematiaceous fungi and Scedosporium/Lomentospora complex, as well as the genera Acremonium sp, Arthrographis sp., Conidiobolus sp., Emericella sp., Engyodontium sp., Paecilomyces sp., Purpureocillium sp., Pythium sp., Rasamsonia sp., Thermothelomyces sp. and Trichoderma sp., with Aspergillus fumigatus being the most common species isolated (Figure 8). These infections are, however, rare with species belonging to the genus Penicillium, including only three publications (one endocarditis due to Penicillium chrysogenum [62] and two pericarditis due to P. citrinum and P. rubens [63,64]) being reported. Cardiac involvement was mainly in the form of endocarditis, whether native (105 publications) or on a prosthetic valve or implanted equipment (96 publications). Interestingly, in native valve endocarditis, mitral involvement seems to be the most frequent (41 publications) (Table 3). Pericarditis and myocarditis were described in 37 and 49 publications, respectively.

Figure 8.

Wordcloud represents the species name isolated in the cardiac system. The size of the name of each species is proportional to the number of times it occurs in the repertoire.

Table 3.

Details of cardiac sites affected by native valve endocarditis and associated species.

3.2.8. Digestive System

Concerning the digestive system, the two main diseases are fungal peritonitis (135 publications) and spleen disease (80 publications) (Figure 9). Micromycetes are known to be responsible for peritonitis during peritoneal dialysis between 1% and 3% of cases, which is indeed the situation we found in the majority of this review [162,163]. In this review, 77.8% of the publications reported peritonitis secondary to peritoneal dialysis (105/135). Other risk factors that emerged were prematurity [164,165,166,167,168] and solid organ transplantation, including the kidney [169,170,171,172,173], heart [174], small bowel [175] and liver [176,177]. Seven publications reported peritoneal involvement secondary to dissemination [174,178,179,180,181,182]. The species mostly found were Aspergillus fumigatus (18 publications), Aspergillus niger (9 publications) and Paecilomyces variotii (8 publications).

Figure 9.

Wordcloud represents the species name isolated in the digestive system. The size of the name of each species is proportional to the number of times it occurs in the repertoire.

Invasive bowel infections by Aspergillus and mucorales (14 and 9 publications, respectively) are mainly reported concomitantly with disseminated infection. Invasion of the gastrointestinal tract is rarely described individually [183].

Splenic involvement was, in the majority of cases, secondary to haematogenous dissemination of the pathogen, with the exception of three situations where splenic abscesses were described. One case of a splenic abscess caused by Aureobasidium pullulans in a patient with lymphoma [184] and one caused by Hortaea werneckii in a patient with acute myeloid leukaemia [185] were both diagnosed postmortem. The third case of splenic abscess caused by Paecilomyces variotii was described in a child with chronic granulomatous disease [186].

3.2.9. Liver Involvement

In terms of hepatic involvement (Figure 10), there is great variability in the forms found, including abscesses, hepatitis, ascites and lesions secondary to hematogenous dissemination (Table 2). The genus Aspergillus is mostly represented (41 publications) with a predominance of Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus.

Figure 10.

Wordcloud represents the species name isolated in the liver. The size of the name of each species is proportional to the number of times it occurs in the repertoire.

3.2.10. Urinary Tract

In terms of urinary tract involvement (Figure 11), the vast majority of infections are renal (185 publications), with a predominance of the genus Aspergillus (85 publications). These infections may be primary or secondary to the haematogenous dissemination of the fungus.

Figure 11.

Wordcloud represents the species name isolated in the urinary tract. The size of the name of each species is proportional to the number of times it occurs in the repertoire.

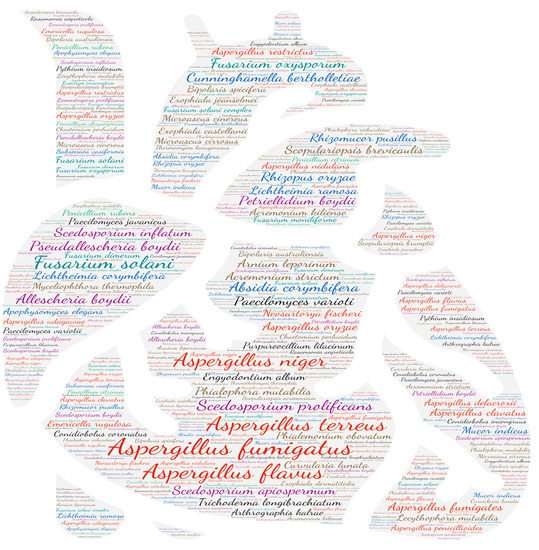

3.2.11. Osteo-Articular System

Among the osteoarticular diseases, osteomyelitis is the most frequent (266 publications). The second most common form is joint damage (164 publications), which includes arthritis (57 publications), bursitis (one publication), unspecified joint damage (60 publications) and synovitis (46 publications). Spondylodiscitis comes in third place (71 publications). Among the species involved in these infections are species of the genus Aspergillus (Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus terreus), the Scedosporium/Lomentospora complex (Pseudallescheria boydii, Scedosporium prolificans and Scedosporium apiospermum) and Fusarium solani (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Wordcloud represents the species name isolated in the osteo-articular system. The size of the name of each species is proportional to the number of times it occurs in the repertoire.

3.2.12. Skin System

Concerning the involvement of the cutaneous system, four affections stand out: superficial cutaneous infection (1195 publications), subcutaneous infection (610 publications), onychomycosis (394 publications) and mycetoma (282 publications). Aspergillus fumigatus is mostly represented (Figure 13) and is mainly responsible for superficial (84 publications) and subcutaneous (37 publications) infections. The subcutaneous infections are mainly due to dematiaceous fungi (338 publications), with Exophiala jeanselmei coming in first position (47 publications). Melanised fungi are responsible for chronic infections, such as chromoblastomycosis, or phaeohyphomycosis, which can evolve towards an invasive character [43]. Eumycotic mycetoma are subcutaneous infections that we have chosen to put aside, mainly due to the species Madurella mycetomatis (67 publications) and Madurella mycetomi (25 publications). Among the agents mainly responsible for onychomycosis, we found Scopulariopsis brevicaulis (50 publications), Hendersonula toruloidea (28 publications), Fusarium oxysporum (22 publications), Scytalidium dimidiatum (20 publications), Aspergillus niger (18 publications) and Fusarium solani (17 publications). These species are responsible for distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis, the most common type of onychomycosis mainly affecting the toenails [187].

Figure 13.

Wordcloud represents the species name isolated in the skin system. The size of the name of each species is proportional to the number of times it occurs in the repertoire.

3.2.13. Endocrine Glands

Among the endocrine glands, the thyroid is the most frequently affected (66 publications/84). In the majority of cases, the disease is secondary to systemic dissemination of the pathogen, diagnosed postmortem [188]. In fact, infiltration of the thyroid with Aspergillus organisms occurs in approximately 20% of autopsies in patients dying from a disseminated disease [189]. However, a few rare cases of primary thyroid infections have been reported with Aspergillus fumigatus: two cases of thyroid suppuration in lupus patients treated with corticosteroids [190,191], two cases described in HIV patients [192,193] and one case in a child with chronic granulomatous disease [194]. Scedosporium apiospermum was reported to cause multiple thyroid abscesses in a patient with cirrhosis and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, presenting swelling in the neck [195].

3.2.14. Rarely Involved Anatomical Sites

Dental location: Endodontic infections were rarely found in this review and manifested themselves in the form of root involvement [196,197], granuloma [198,199] or gingival infections [200,201]. No species seemed to have a particular tropism for this sphere.

Genital sphere: Interestingly, the male genital sphere seems to be mostly affected, with 71.4% of the publications (15/21) reporting testicular, epididymal or glans involvement. Only three publications reported vaginitis [202,203,204], two reported labial involvement [190,205] and one tubo-ovarian abscess [206]. No species seemed to have a particular tropism for this sphere.

Breast: A majority of Aspergillus was isolated from this particular site. It should be noted that the Aspergillus glaucus and Aspergillus niger complexes have already been isolated from milk samples [207,208]. Interestingly, four publications reported fungal infections following breast implant surgery, a situation that is not well-known in this field, due to Aspergillus niger [209,210], Paecilomyces variotii [211] and Scedosporium apiospermum [212].

Placental infection: a single case of placental aspergillosis due to Aspergillus niger was found in this literature review [213].

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to establish as exhaustive a catalogue as possible of filamentous fungi identified in humans by culture and molecular biology, whether or not they were associated with histopathological findings. We found 565 filamentous fungi identified in humans, for which we specified the organs where these fungi had been found and the semiology of the infections. This repertoire thus helps to understand the pathogenic potential of certain fungi and can also alert clinicians that the isolation of certain rare fungi, such as Trichoderma longibrachiatum (from stool specimens), can lead to disseminated infection. One of the limitations of this work, however, is the lack of distinction between colonisation and infection, mainly for fungi isolated from non-sterile sites (i.e., the cutaneous system, pulmonary system, digestive system and ENT sphere). Fungi isolated from sterile sites were considered infections (i.e., the heart, liver and ocular system and CNS). The use of new powerful molecular tools, such as pan-fungal PCR, metagenomic and next-generation sequencing, now means it is possible to detect pathogens even in samples containing extremely low levels of nucleic acids [214,215] and to diagnose mixed infections [216]. However, the application of these tools to medical mycology can lead to interpretation difficulties [217,218,219]. This problem is particularly encountered with filamentous fungi, which are ubiquitous in the environment and for which it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between colonisation, infection and environmental contamination. It is now necessary to go further in our work for each anatomical site in order to distinguish colonisations from infections, in order to help clinicians interpret positive results and to assist with the diagnostic management of patients. Similarly, we did not distinguish between diagnosis by molecular biology and macroscopic identification, although it has been shown that potential errors were found in macroscopic identifications, mostly between close species within a section or species complex [4]. More, even in molecular identification, it was pointed out that 20% of the sequences available in public databases are unreliable [220,221]. We have based our repertoire according to state of the art at the time of reported publications. Therefore, in Table 1, we have chosen to group species by sections, sharing morphological similarities, in order to bypass this limitation.

Finally, one of the limitations of this publication is its temporality. As explained in Section 2, only references present in PubMed before 16 June 2020 were taken into account in order to have the same PubMed content for all fungi species. However, medical mycology is dynamic, and new organisms constantly need to be accounted for by both clinicians and microbiology laboratories [222]. Moreover, with the COVID-19 pandemic, a new risk factor has emerged [223]. Publications reporting the detection of filamentous fungi in humans have multiplied, reporting, for example, the emergence of mucormycosis and COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis throughout the world [224,225]. It will therefore be necessary to update this data regularly.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R. and C.L.; methodology, E.M., Q.F. and. J.-C.D.; software, Q.F. and. J.-C.D.; formal analysis, E.M. and C.L.; data curation, E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M., C.L. and J.-C.D.; supervision, S.R. and C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Blackwell, M. The Fungi: 1, 2, 3 … 5.1 Million Species? Am. J. Bot. 2011, 98, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, H.E.; Parrent, J.L.; Jackson, J.A.; Moncalvo, J.-M.; Vilgalys, R. Fungal Community Analysis by Large-Scale Sequencing of Environmental Samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 5544–5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köhler, J.R.; Casadevall, A.; Perfect, J. The Spectrum of Fungi That Infects Humans. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a019273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balajee, S.A.; Nickle, D.; Varga, J.; Marr, K.A. Molecular Studies Reveal Frequent Misidentification of Aspergillus fumigatus by Morphotyping. Eukaryot. Cell 2006, 5, 1705–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stengel, A.; Stanke, K.M.; Quattrone, A.C.; Herr, J.R. Improving Taxonomic Delimitation of Fungal Species in the Age of Genomics and Phenomics. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 847067. [Google Scholar]

- Enoch, D.A.; Yang, H.; Aliyu, S.H.; Micallef, C. The Changing Epidemiology of Invasive Fungal Infections. In Human Fungal Pathogen Identification; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 17–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jenks, J.D.; Cornely, O.A.; Chen, S.C.-A.; Thompson, G.R.; Hoenigl, M. Breakthrough Invasive Fungal Infections: Who Is at Risk? Mycoses 2020, 63, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.R.; Hube, B.; Puccia, R.; Casadevall, A.; Perfect, J.R. Fungi That Infect Humans. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, 5.3.08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.K.K.; Padmavathi, A.R.; Nancharaiah, Y.V. Fungal Infections: Pathogenesis, Antifungals and Alternate Treatment Approaches. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2022, 3, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.E.; Wengenack, N.L.; Walsh, T.J. Non-Aspergillus Hyaline Molds: Emerging Causes of Sino-Pulmonary Fungal Infections and Other Invasive Mycoses. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 41, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, P.J.; Antao, T.; Chang, J.T.; Chapman, B.A.; Cox, C.J.; Dalke, A.; Friedberg, I.; Hamelryck, T.; Kauff, F.; Wilczynski, B. Biopython: Freely Available Python Tools for Computational Molecular Biology and Bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1422–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, R.A.; Visagie, C.M.; Houbraken, J.; Hong, S.-B.; Hubka, V.; Klaassen, C.H.W.; Perrone, G.; Seifert, K.A.; Susca, A.; Tanney, J.B.; et al. Phylogeny, Identification and Nomenclature of the Genus Aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 78, 141–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visagie, C.M.; Houbraken, J.; Frisvad, J.C.; Hong, S.-B.; Klaassen, C.H.W.; Perrone, G.; Seifert, K.A.; Varga, J.; Yaguchi, T.; Samson, R.A. Identification and Nomenclature of the Genus Penicillium. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 78, 343–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houbraken, J.; Kocsubé, S.; Visagie, C.M.; Yilmaz, N.; Wang, X.-C.; Meijer, M.; Kraak, B.; Hubka, V.; Bensch, K.; Samson, R.A.; et al. Classification of Aspergillus, Penicillium, Talaromyces and Related Genera (Eurotiales): An Overview of Families, Genera, Subgenera, Sections, Series and Species. Stud. Mycol. 2020, 95, 5–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Diepeningen, A.D.; Al-Hatmi, A.; Brankovics, B.; de Hoog, G.S. Taxonomy and Clinical Spectra of Fusarium Species: Where Do We Stand in 2014? Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2014, 1, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarro, J. Fusariosis, a Complex Infection Caused by a High Diversity of Fungal Species Refractory to Treatment. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 32, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revankar, S.G.; Sutton, D.A. Melanized Fungi in Human Disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 884–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, G.; Wagner, L.; Kurzai, O. Updates on the Taxonomy of Mucorales with an Emphasis on Clinically Important Taxa. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubka, V.; Nováková, A.; Kolařík, M.; Jurjević, Ž.; Peterson, S.W. Revision of Aspergillus Section Flavipedes: Seven New Species and Proposal of Section Jani Sect. Nov. Mycol. 2015, 107, 169–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakhage, A.A.; Langfelder, K. Menacing Mold: The Molecular Biology of Aspergillus fumigatus. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2002, 56, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latge, J.-P. Aspergillus fumigatus, a Saprotrophic Pathogenic Fungus. Mycologist 2003, 17, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Burik, J.A.; Colven, R.; Spach, D.H. Cutaneous Aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998, 36, 3115–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, T.J. Primary Cutaneous Aspergillosis—An Emerging Infection among Immunocompromised Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 27, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avkan-Oğuz, V.; Çelik, M.; Satoglu, I.S.; Ergon, M.C.; Açan, A.E. Primary Cutaneous Aspergillosis in Immunocompetent Adults: Three Cases and a Review of the Literature. Cureus 2020, 12, e6600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali Sarvestani, H.; Seifi, A.; Falahatinejad, M.; Mahmoudi, S. Black Aspergilli as Causes of Otomycosis in the Era of Molecular Diagnostics, a Mini-Review. J. Mycol. Med. 2022, 32, 101240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Sutton, D.A.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Sarver, B.A.J.; Balajee, S.A.; Schroers, H.-J.; Summerbell, R.C.; Robert, V.A.R.G.; Crous, P.W.; Zhang, N.; et al. Internet-Accessible DNA Sequence Database for Identifying Fusaria from Human and Animal Infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 3708–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, M.; Anaissie, E. Fusarium Infections in Immunocompromised Patients. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabasse, D.; Pihet, M. Onychomycoses due to molds. J. Mycol. Med. 2014, 24, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarro, J.; Gené, J. Opportunistic Fusarial Infections in Humans. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1995, 14, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Aguas, M.; Khoo, P.; Watson, S.L. Infectious Keratitis: A Review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 50, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayayo, E.; Pujol, I.; Guarro, J. Experimental Pathogenicity of Four Opportunist Fusarium Species in a Murine Model. J. Med. Microbiol. 1999, 48, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanittanakom, N.; Cooper, C.R.; Fisher, M.C.; Sirisanthana, T. Penicillium marneffei Infection and Recent Advances in the Epidemiology and Molecular Biology Aspects. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, C.; Xi, L.; Chaturvedi, V. Talaromycosis (Penicilliosis) Due to Talaromyces (Penicillium) Marneffei: Insights into the Clinical Trends of a Major Fungal Disease 60 Years After the Discovery of the Pathogen. Mycopathologia 2019, 184, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolás, F.E.; Murcia, L.; Navarro, E.; Navarro-Mendoza, M.I.; Pérez-Arques, C.; Garre, V. Mucorales Species and Macrophages. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, G.; Wagner, L.; Kurzai, O. Outbreaks of Mucorales and the Species Involved. Mycopathologia 2020, 185, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelievre, L.; Garcia-Hermoso, D.; Abdoul, H.; Hivelin, M.; Chouaki, T.; Toubas, D.; Mamez, A.-C.; Lantieri, L.; Lortholary, O.; Lanternier, F.; et al. Posttraumatic Mucormycosis: A Nationwide Study in France and Review of the Literature. Medicine 2014, 93, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribes, J.A.; Vanover-Sams, C.L.; Baker, D.J. Zygomycetes in Human Disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 236–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.Z.R.; Lewis, R.E.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Mucormycosis Caused by Unusual Mucormycetes, Non-Rhizopus, -Mucor, and -Lichtheimia Species. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 411–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabasse, D. Mycoses à Champignons Noirs: Chromoblastomycoses et Phæohyphomycoses; Elsevier Masson: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 2-84299-508-2. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, H.A.; Bruce, S.; Rosen, T.; McBride, M.E. Evidence for Percutaneous Inoculation as the Mode of Transmission for Chromoblastomycosis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1991, 25, 951–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, A.; Siqueira, N.P.; Nery, A.F.; Cavalcante, L.R.D.S.; Hagen, F.; Hahn, R.C. Chromoblastomycosis in Latin America and the Caribbean: Epidemiology over the Past 50 Years. Med. Mycol. 2021, 60, myab062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcobello, J.T.; Revankar, S.G. Phaeohyphomycosis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 41, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, D.M.; Polak-Wyss, A. The Medically Important Dematiaceous Fungi and Their Identification. Mycoses 1991, 34, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luplertlop, N. Pseudallescheria/Scedosporium Complex Species: From Saprobic to Pathogenic Fungus. J. Mycol. Med. 2018, 28, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronnimann, D.; Garcia-Hermoso, D.; Dromer, F.; Lanternier, F.; Dorothée, C. Characterization of the Isolates at the NRCMA Boullié Anne Gautier Cécile Hessel Audrey Hoinard Damien Raoux-Barbot Dorothée. Scedosporiosis/Lomentosporiosis Observational Study (SOS): Clinical Significance of Scedosporium Species Identification. Med. Mycol. 2021, 59, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gade, L.; Grgurich, D.E.; Kerkering, T.M.; Brandt, M.E.; Litvintseva, A.P. Utility of Real-Time PCR for Detection of Exserohilum rostratum in Body and Tissue Fluids during the Multistate Outbreak of Fungal Meningitis and Other Infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvintseva, A.P.; Hurst, S.; Gade, L.; Frace, M.A.; Hilsabeck, R.; Schupp, J.M.; Gillece, J.D.; Roe, C.; Smith, D.; Keim, P.; et al. Whole-Genome Analysis of Exserohilum rostratum from an Outbreak of Fungal Meningitis and Other Infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 3216–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andes, D.; Casadevall, A. Insights into Fungal Pathogenesis from the Iatrogenic Epidemic of Exserohilum rostratum Fungal Meningitis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2013, 61, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Perlin, D.S.; Roilides, E.; Walsh, T.J. What Can We Learn and What Do We Need to Know amidst the Iatrogenic Outbreak of Exserohilum rostratum Meningitis? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadevall, A.; Pirofski, L.-A. Exserohilum rostratum Fungal Meningitis Associated with Methylprednisolone Injections. Future Microbiol. 2013, 8, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Petraitiene, R.; Walsh, T.J.; Perlin, D.S. A Real-Time PCR Assay for Rapid Detection and Quantification of Exserohilum rostratum, a Causative Pathogen of Fungal Meningitis Associated with Injection of Contaminated Methylprednisolone. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 1034–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Góralska, K.; Blaszkowska, J.; Dzikowiec, M. Neuroinfections Caused by Fungi. Infection 2018, 46, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanatha, B.; Sumatha, D.; Vijayashree, M.S. Otomycosis in Immunocompetent and Immunocompromised Patients: Comparative Study and Literature Review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2012, 91, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, O.; Potter, C. Scedosporium apiospermum: A Rare Cause of Malignant Otitis Externa. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016, bcr2016217015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Messner, A.H. Fungal Malignant Otitis Externa Due to Scedosporium apiospermum. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2001, 110, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huguenin, A.; Noel, V.; Rogez, A.; Chemla, C.; Villena, I.; Toubas, D. Scedosporium apiospermum Otitis Complicated by a Temporomandibular Arthritis: A Case Report and Mini-Review. Mycopathologia 2015, 180, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, P.J.; Marshall, S.R.; Shaw, B.; Kendra, J.R.; Ethel, M.; Kibbler, C.C.; Prentice, H.G.; Potter, M. Fatal Invasive Cerebral Absidia Corymbifera Infection Following Bone Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2000, 26, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiada, A.; Pavleas, I.; Drogari-Apiranthitou, M. Epidemiology and Diagnosis of Mucormycosis: An Update. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelet, J.-T.; Buiret, G.; Chevallier, M.; Bergerot, J.-F.; Ory, L.; Gleizal, A. Conidiobolus coronatus infections revealed by a facial tumor. Rev. Stomatol. Chir. Maxillofac. Chir. Orale 2014, 115, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.; Kokki, M.H.; Anderson, K.; Richardson, M.D. Sampling of Aspergillus Spores in Air. J. Hosp. Infect. 2000, 44, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagenais, T.R.T.; Keller, N.P. Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in Invasive Aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upshaw, C.B. Penicillium Endocarditis of Aortic Valve Prosthesis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1974, 68, 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guevara-Suarez, M.; Sutton, D.A.; Cano-Lira, J.F.; García, D.; Martin-Vicente, A.; Wiederhold, N.; Guarro, J.; Gené, J. Identification and Antifungal Susceptibility of Penicillium-Like Fungi from Clinical Samples in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 2155–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, T.; Koehler, A.P.; Yu, M.Y.; Ellis, D.H.; Johnson, P.J.; Wickham, N.W. Fatal Penicillium Citrinum Pneumonia with Pericarditis in a Patient with Acute Leukemia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997, 35, 2654–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, M.E.; McManus, M.; Dietz, J.; Camitta, B.M.; Szabo, S.; Havens, P. Absidia Corymbifera Endocarditis: Survival after Treatment of Disseminated Mucormycosis with Radical Resection of Tricuspid Valve and Right Ventricular Free Wall. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010, 139, e71–e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo, A.; McGinnis, M.R.; Malloch, D.; Porras, A.; Giraldo, N.; Villegas, A.; Herrera, J. Fungal Endocarditis Caused by Arnium leporinum Following Cardiac Surgery. Sabouraudia 1984, 22, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Diego Candela, J.; Forteza, A.; García, D.; Prieto, G.; Bellot, R.; Villar, S.; Cortina, J.M. Endocarditis Caused by Arthrographis Kalrae. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2010, 90, e4–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opal, S.M.; Reller, L.B.; Harrington, G.; Cannady, P. Aspergillus clavatus Endocarditis Involving a Normal Aortic Valve Following Coronary Artery Surgery. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1986, 8, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, W.C.; Buchbinder, N.A. Right-Sided Valvular Infective Endocarditis. A Clinicopathologic Study of Twelve Necropsy Patients. Am. J. Med. 1972, 53, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschstein, R.L.; Sidransky, H. Mycotic Endocarditis of the Tricuspid Valve Due to Aspergillus flavus; Report of a Case. AMA Arch. Pathol. 1956, 62, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, G.L.; Wood, R.P.; Shaw, B.W. Aspergillus Endocarditis in Patients without Prior Cardiovascular Surgery: Report of a Case in a Liver Transplant Recipient and Review. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1989, 11, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, H.F.; Simpson, E.M.; Wilson, N.; Richardson, M.D.; Michie, J.R. Aspergillus flavus Endocarditis in a Child with Neuroblastoma. J. Infect. 1998, 36, 126–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Saha, V. Medical Management of Aspergillus flavus Endocarditis. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2000, 17, 425–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsobayeg, S.; Alshehri, N.; Mohammed, S.; Fadel, B.M.; Omrani, A.S.; Almaghrabi, R.S. Aspergillus flavus Native Valve Endocarditis Following Combined Liver and Renal Transplantation: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2018, 20, e12891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaria, R.G.; Dürrleman, N.; Rispail, P.; Margueritte, G.; Macia, J.C.; Aymard, T.; Frapier, J.M.; Albat, B.; Chaptal, P.A. Aspergillus flavus Mitral Valve Endocarditis after Lung Abscess. J. Heart Valve Dis 2000, 9, 786–790. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Z.U.; Sanyal, S.C.; Mokaddas, E.; Vislocky, I.; Anim, J.T.; Salama, A.L.; Shuhaiber, H. Endocarditis Due to Aspergillus flavus. Mycoses 1997, 40, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irles, D.; Bonadona, A.; Pofelski, J.; Laramas, M.; Molina, L.; Lantuejoul, S.; Brenier-Pinchart, M.P.; Bagueta, J.P.; Barnoud, D. Aspergillus flavus endocarditis on a native valve. Arch. Mal. Coeur Vaiss. 2004, 97, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J.F.; Mullany, D.; Natani, S.; Chinthamuneedi, M.; Hovarth, R. Aspergillus flavus Endocarditis--to Prevaricate Is to Posture. Crit. Care Resusc. 2006, 8, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, D.; Bal, A.; Singhal, M.; Vijayvergiya, R.; Das, A. Fibrosing Mediastinitis Due to Aspergillus with Dominant Cardiac Involvement: Report of Two Autopsy Cases with Review of Literature. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2014, 23, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, T.; Ergenoglu, M.U.; Ekinci, A.; Tanrikulu, N.; Sahin, M.; Demirsoy, E. Aspergillus flavus Endocarditis of the Native Mitral Valve in a Bone Marrow Transplant Patient. Am. J. Case Rep. 2015, 16, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto Cuadra, J.D.; Grande Prada, D.; Morcillo Hidalgo, L.; Hierro Martín, I. Cardiac Aspergillosis: An Atypical Case of Haematogenous Disseminated Endocarditis. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, J.T.; Hendrickson, M.; Sholes, W.M.; Portnoy, D.A.; Bell, W.H.; Kerstein, M.D. Acute Aortic Occlusion Secondary to Aspergillus Endocarditis in an Intravenous Drug Abuser. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 1991, 5, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassiloyanakopoulos, A.; Falagas, M.E.; Allamani, M.; Michalopoulos, A. Aspergillus fumigatus Tricuspid Native Valve Endocarditis in a Non-Intravenous Drug User. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 55, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Meensel, B.; Meersseman, W.; Bammens, B.; Peetermans, W.E.; Herregods, M.-C.; Herijgers, P.; Lagrou, K. Fatal Right-Sided Endocarditis Due to Aspergillus in a Kidney Transplant Recipient. Med. Mycol. 2007, 45, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pozo, J.L.; van de Beek, D.; Daly, R.C.; Pulido, J.S.; McGregor, C.G.A.; Patel, R. Incidence and Clinical Characteristics of Ocular Infections after Heart Transplantation: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin. Transpl. 2009, 23, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vohra, S.; Taylor, R.; Aronowitz, P. The Tell-Tale Heart: Aspergillus fumigatus Endocarditis in an Immunocompetent Patient. Hosp. Pract. 2013, 41, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishniavsky, N.; Sagar, K.B.; Markowitz, S.M. Aspergillus fumigatus Endocarditis on a Normal Heart Valve. South Med. J. 1983, 76, 506–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henochowicz, S.; Mustafa, M.; Lawrinson, W.E.; Pistole, M.; Lindsay, J. Cardiac Aspergillosis in Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol. 1985, 55, 1239–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.N.; di Dió, F.; Pizzolato, G.P.; Lerch, R.; Pochon, N. Aspergillus Endocarditis and Myocarditis in a Patient with the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). A Review of the Literature. Virchows Arch. A Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 1990, 417, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotanidou, A.N.; Zakynthinos, E.; Andrianakis, I.; Zervakis, D.; Kokotsakis, I.; Argyrakos, T.; Argiropoulou, A.; Margariti, G.; Douzinas, E. Aspergillus Endocarditis in a Native Valve after Amphotericin B Treatment. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2004, 78, 1453–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, M.; Fieguth, H.-G.; Aybek, T.; Ujvari, Z.; Moritz, A.; Wimmer-Greinecker, G. Disseminated Aspergillus fumigatus Infection with Consecutive Mitral Valve Endocarditis in a Lung Transplant Recipient. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2005, 24, 2297–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, P.; Clarke, B.; Dunning, J. Aspergillus Endocarditis of the Mitral Valve in a Lung-Transplant Patient. Tex Heart Inst. J. 2007, 34, 95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pemán, J.; Ortiz, R.; Osseyran, F.; Pérez-Bellés, C.; Crespo, M.; Chirivella, M.; Frasquet, J.; Quesada, A.; Cantón, E.; Gobernado, M. Native valve Aspergillus fumigatus endocarditis with blood culture positive and negative for galactomannan antigen. Case report and literature review. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2007, 24, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morio, F.; Treilhaud, M.; Lepelletier, D.; Le Pape, P.; Rigal, J.-C.; Delile, L.; Robert, J.-P.; Al Habash, O.; Miegeville, M.; Gay-Andrieu, F. Aspergillus fumigatus Endocarditis of the Mitral Valve in a Heart Transplant Recipient: A Case Report. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008, 62, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayad, G.; Legout, L.; Colombie, V.; Modine, T.; Senneville, E.; Leroy, O. Aspergillus fumigatus Mitral Native Valve Endocarditis. J. Heart Valve Dis. 2009, 18, 472–473. [Google Scholar]

- Philippe, B.; Grenet, D.; Honderlick, P.; Longchampt, E.; Dupont, B.; Picard, C.; Stern, M. Severe Aspergillus Endocarditis in a Lung Transplant Recipient with a Five-Year Survival. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2010, 12, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rofaiel, R.; Turkistani, Y.; McCarty, D.; Hosseini-Moghaddam, S.M. Fungal Mobile Mass on Echocardiogram: Native Mitral Valve Aspergillus fumigatus Endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016, bcr2016217281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares, J.C.; Bernal, S.; Marín, M.; Holgado, V.P.; Castro, C.; Morales, W.P.; Martin, E. Molecular Diagnosis of Aspergillus fumigatus Endocarditis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 70, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, J.; Guinea, J.; Torres-Narbona, M.; Muñoz, P.; Peláez, T.; Bouza, E. Post-Surgical Invasive Aspergillosis: An Uncommon and under-Appreciated Entity. J. Infect. 2010, 60, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, T.M.; Carby, M.R.; Hall, A.V.; Banner, N.R.; Burke, M.M.; Dreyfus, G.D. Native Valve Aspergillus Endocarditis Complicating Lung Transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2008, 27, 910–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.G.; García-Fernández, M.A.; Sarnago Cebada, F. Aspergillus Endocarditis. Echocardiography 2005, 22, 623–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman-Weber, S.; Axelrod, P.; Suh, B.; Rubin, S.; Beltramo, D.; Manacchio, J.; Furukawa, S.; Weber, T.; Eisen, H.; Samuel, R. Infective Endocarditis Following Orthotopic Heart Transplantation: 10 Cases and a Review of the Literature. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2004, 6, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocqueloux, L.; Bruneel, F.; Pages, C.L.; Vachon, F. Fatal Invasive Aspergillosis Complicating Severe Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 30, 940–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbey, J.G.; Chalermskulrat, W.; Aris, R.M. Aspergillus Endocarditis in a Lung Transplant Recipient. A Case Report and Review of the Transplant Literature. Ann. Transpl. 2000, 5, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, H.I.; Frisch, E.; Houghton, J.D.; Climo, M.S.; Natsios, G.A. Aspergillus fumigatus Endocarditis. Report of a Case Diagnosed during Life. Ann. Intern. Med. 1968, 68, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Gómez, R.; Valdespino Estrada, A.; López Ortiz, R. Aspergillus Endocarditis. Report of a case treated surgically with success. Arch. Inst. Cardiol. Mex. 1981, 51, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bogner, J.R.; Lüftl, S.; Middeke, M.; Spengel, F. Successful drug therapy in Aspergillus Endocarditis. Dtsch Med. Wochenschr. 1990, 115, 1833–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijer, P.M.; Kuijper, E.J.; van den Tweel, J.G.; van der Lelie, J. Aspergillus fumigatus, a Rare Cause of Fatal Coronary Artery Occlusion. Infection 1992, 20, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, M.R.; Guerrero, M.A.; Daly, R.C.; Walker, R.C.; Davies, S.F. Transmission of Invasive Aspergillosis from a Subclinically Infected Donor to Three Different Organ Transplant Recipients. Chest 1996, 109, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Rahman, M.; Kundi, A.; Najeeb, M.A.; Samad, A. Aspergillus fumigatus Endocarditis. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 1990, 40, 95–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bozbuga, N.; Erentug, V.; Erdogan, H.B.; Kirali, K.; Ardal, H.; Tas, S.; Akinci, E.; Yakut, C. Surgical Treatment of Aortic Abscess and Fistula. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2004, 31, 382–386. [Google Scholar]

- Attia, R.Q.; Nowell, J.L.; Roxburgh, J.C. Aspergillus Endocarditis: A Case of near Complete Left Ventricular Outflow Obstruction. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 14, 894–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzi, L.; Laifer, G.; Bremerich, J.; Vosbeck, J.; Mayr, M. Invasive Apergillosis with Myocardial Involvement after Kidney Transplantation. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2005, 20, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, I.M.; Leadbeatter, S.; Peters, T.J.; Mullins, J.; Philpot, C.M.; Salaman, J.R. An Outbreak of Disseminated Aspergillosis Associated with an Intensive Care Unit. Community Med. 1988, 10, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, D.A. Aspergillus Pancarditis Following Bone Marrow Transplantation for Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia. Chest 1989, 95, 1338–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, D.L.; Dominguez, E.A.; Chang, F.Y.; Snydman, D.R.; Singh, N. Infective Endocarditis in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 26, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlina, A.A.; Peacock, J.W.; Ranginwala, S.A.; Pavlina, P.M.; Ahier, J.; Hanak, C.R. Aspergillus Mural Endocarditis Presenting with Multiple Cerebral Abscesses. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lázaro, M.; Ramos, A.; Ussetti, P.; Asensio, A.; Laporta, R.; Muñez, E.; Sánchez-Romero, I.; Tejerina, E.; Burgos, R.; Moñivas, V.; et al. Aspergillus Endocarditis in Lung Transplant Recipients: Case Report and Literature Review. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2011, 13, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnicka, K.; Arendarczyk, A.; Hendzel, P.; Zdończyk, O.; Pruszczyk, P. An Unexpected Diagnosis in a Patient with 2 Left Atrial Pathological Masses Found by Echocardiography. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2018, 128, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comerio, G.; Ferratini, M.; Pezzano, A.; Racca, V.; Tavanelli, M.; Pirelli, L.; Fundarò, P.; Mattioli, R.; Donatelli, F. Resection of unusual atrial mass complicated with fungal endocarditis in a patient undergoing immunosuppressive treatment. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2003, 60, 166–169. [Google Scholar]

- Davutoglu, V.; Soydinc, S.; Aydin, A.; Karakok, M. Rapidly Advancing Invasive Endomyocardial Aspergillosis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2005, 18, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, B.; Wróblewska-Kałuzewska, M.; Kucińska, B.; Wójcicka-Urbańska, B. Clinical and therapeutic considerations in children with infective endocarditis. Med. Wieku Rozwoj. 2007, 11, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cesaro, S.; Toffolutti, T.; Messina, C.; Calore, E.; Alaggio, R.; Cusinato, R.; Pillon, M.; Zanesco, L. Safety and Efficacy of Caspofungin and Liposomal Amphotericin B, Followed by Voriconazole in Young Patients Affected by Refractory Invasive Mycosis. Eur. J. Haematol. 2004, 73, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, D.H.; Riordan, F.A.; Ladusens, E.J. Aspergillus Endocarditis in Chronic Granulomatous Disease. Acta Paediatr. 1996, 85, 758–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, D.; Barnes, R.; Poynton, C.; White, P.L.; Işik, N.; Cook, D. Polymerase Chain Reaction Aids in the Diagnosis of an Unusual Case of Aspergillus niger Endocarditis in a Patient with Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. J. Infect. 2003, 47, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chim, C.S.; Ho, P.L.; Yuen, S.T.; Yuen, K.Y. Fungal Endocarditis in Bone Marrow Transplantation: Case Report and Review of Literature. J. Infect. 1998, 37, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schett, G.; Casati, B.; Willinger, B.; Weinländer, G.; Binder, T.; Grabenwöger, F.; Sperr, W.; Geissler, K.; Jäger, U. Endocarditis and Aortal Embolization Caused by Aspergillus terreus in a Patient with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Remission: Diagnosis by Peripheral-Blood Culture. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998, 36, 3347–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verghese, S.; Maria, C.F.; Mullaseri, A.S.; Asha, M.; Padmaja, P.; Padhye, A.A. Aspergillus Endocarditis Presenting as Femoral Artery Embolism. Mycoses 2004, 47, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, P.-M.; Kamphoff, S.; Ansorg, R. Value of Different Methods for the Characterisation of Aspergillus terreus Strains. J. Med. Microbiol. 1999, 48, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, A.; Yoshida, A.; Matsuda, Y.; Kawata, M.; Nishimura, T.; Tanaka, J.; Misawa, Y.; Nakano, Y.; Asami, R.; Chida, K.; et al. Fatal Fungal Endocarditis by Aspergillus udagawae: An Emerging Cause of Invasive Aspergillosis. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2017, 28, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, N.N.; Romanelli, J.; Sutton, M.G.S.J. Native Aortic Valve Vegetative Endocarditis with Cunninghamella. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2004, 5, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, R.; Kerkmann, M.L.; Schuler, U.; Daniel, W.G.; Ehninger, G. Cunninghamella Bertholletiae Infection Mimicking Myocardial Infarction. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999, 29, 1580–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustinsky, J.; Kammeyer, P.; Husain, A.; deHoog, G.S.; Libertin, C.R. Engyodontium Album Endocarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990, 28, 1479–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.K.; Patel, K.K.; Darji, P.; Singh, R.; Shivaprakash, M.R.; Chakrabarti, A. Exophiala Dermatitidis Endocarditis on Native Aortic Valve in a Postrenal Transplant Patient and Review of Literature on E. Dermatitidis Infections. Mycoses 2013, 56, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Sutton, D.A.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Gueidan, C.; Crous, P.W.; Geiser, D.M. Novel Multilocus Sequence Typing Scheme Reveals High Genetic Diversity of Human Pathogenic Members of the Fusarium Incarnatum-F. Equiseti and F. Chlamydosporum Species Complexes within the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 3851–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman-Cottrill, J.A.; Zheng, X.; Chadwick, E.G. Fusarium Solani Endocarditis Successfully Treated with Liposomal Amphotericin B and Voriconazole. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2004, 23, 1059–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busemann, C.; Krüger, W.; Schwesinger, G.; Kallinich, B.; Schröder, G.; Abel, P.; Kiefer, T.; Neumann, T.; Dölken, G. Myocardial and Aortal Involvement in a Case of Disseminated Infection with Fusarium Solani after Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation: Report of a Case. Mycoses 2009, 52, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassar, O.; Charfi, M.; Trabelsi, H.; Hammami, R.; Elloumi, M. Fusarium Solani Endocarditis in an Acute Leukemia Patient. Med. Mal. Infect. 2016, 46, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inano, S.; Kimura, M.; Iida, J.; Arima, N. Combination Therapy of Voriconazole and Terbinafine for Disseminated Fusariosis: Case Report and Literature Review. J. Infect. Chemother. 2013, 19, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Stevens, R.; Konecny, P. Lomentospora Prolificans Endocarditis—Case Report and Literature Review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbeau, P.; McGough, D.A.; Fraser, H.; Shah, N.; Rinaldi, M.G. Fatal Disseminated Infection Caused by Myceliophthora Thermophila, a New Agent of Mycosis: Case History and Laboratory Characteristics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992, 30, 3019–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Naourès, C.; Bonhomme, J.; Terzi, N.; Duhamel, C.; Galateau-Sallé, F. A Fatal Case with Disseminated Myceliophthora Thermophila Infection in a Lymphoma Patient. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 70, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allevato, P.A.; Ohorodnik, J.M.; Mezger, E.; Eisses, J.F. Paecilomyces Javanicus Endocarditis of Native and Prosthetic Aortic Valve. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1984, 82, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, C.H.; Lendrum, J.L.; Wetherall, B.L.; Wesselingh, S.L.; Gordon, D.L. Phaeoacremonium Parasiticum Infective Endocarditis Following Liver Transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1997, 25, 1251–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavin, P.J.; Sutton, D.A.; Katz, B.Z. Fatal Endocarditis in a Neonate Caused by the Dematiaceous Fungus Phialemonium Obovatum: Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 2207–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, H.; Sutton, D.A.; García, D.; Fothergill, A.W.; Gené, J.; Cano, J.; Summerbell, R.C.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Guarro, J. Molecular and Phenotypic Characterization of Phialemonium and Lecythophora Isolates from Clinical Samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurini, J.A.; Carter, J.E.; Kahn, A.G. Tricuspid Valve and Pacemaker Endocarditis Due to Pseudallescheria Boydii (Scedosporium apiospermum). South Med. J. 2009, 102, 515–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffanti, S.P.; Fyfe, B.; Carreiro, S.; Sharp, S.E.; Hyma, B.A.; Ratzan, K.R. Native Valve Endocarditis Due to Pseudallescheria Boydii in a Patient with AIDS: Case Report and Review. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1990, 12, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morio, F.; Horeau-Langlard, D.; Gay-Andrieu, F.; Talarmin, J.-P.; Haloun, A.; Treilhaud, M.; Despins, P.; Jossic, F.; Nourry, L.; Danner-Boucher, I.; et al. Disseminated Scedosporium/Pseudallescheria Infection after Double-Lung Transplantation in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 1978–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolova, L.G.; Johnson, E.K.; Adams, H.P. Disseminated Pseudallescheria Boydii Infection Successfully Treated with Voriconazole. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76, 1741–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welty, F.K.; McLeod, G.X.; Ezratty, C.; Healy, R.W.; Karchmer, A.W. Pseudallescheria Boydii Endocarditis of the Pulmonic Valve in a Liver Transplant Recipient. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1992, 15, 858–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]