Abstract

Surveys conducted in a nursery located in eastern Sicily, southern Italy, revealed the presence of plants of Vachellia nilotica (syn. Acacia arabica), V. farnesiana (syn. A. farnesiana) and Pithecellobium dulce showing symptoms of trunk and branch canker, shoot dieback and general decline. Laboratory fungal isolation from wood tissues showed high percentage of Diaporthe-like (60–62%) and Botryosphaeriaceae-like fungi (21–85%) constantly associated with the diseased samples. Subsequent molecular characterization of recovered isolates was based on sequencing of the complete internally transcribed spacer region (ITS), the translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1) and the beta-tubulin (tub2) regions, followed by multi-locus phylogenetic analyses. The isolates collected from symptomatic tissues were phylogenetically characterized as Diaporthe foeniculina and Neofusicoccum parvum. Pathogenicity tests were conducted on Acacia and P. dulce plants and results showed that both species were pathogenic, being able to induce necrotic lesions on the stem. To our knowledge this is the first report worldwide of D. foeniculina and N. parvum infecting A. arabica, A. farnesiana and P. dulce.

1. Introduction

Fabaceae (or Leguminosae) [1] is an economically and ecologically important plant family including close to 770 genera and over 19,500 species [2]. This family includes Acacia species, some of them re-ordered nowadays within the genus Vachellia—woody perennial trees native to Australia, with some of them naturalized and invasive [3]—and Pithecellobium dulce, an evergreen plant native to Mexico known for its nutritional and medicinal properties [4]. In Italy, Acacia and P. dulce are cultivated and widely distributed, especially in the southern regions, for ornamental purposes. No relevant diseases have been reported for P. dulce; in fact, only few fungal associations have been listed, most of which with no symptoms recorded [5]. Regarding Acacia species, many fungal diseases have been reported worldwide, especially in tropical regions [6]. Since nurseries represent a key location in the production of plants, particular attention needs to be given to all strategies for preventing diseases occurring during this phase. In fact, diseases occurring in the nursery, especially those caused by canker-causing pathogens, are not always immediately detectable. Symptomatology can remain hidden throughout the latency of canker pathogens, and diseases may only be fully expressed after transplanting in the field [7].

Major fungal diseases of Acacia spp. occurring in the nursery include foliar diseases such as Pestalotiopsis leaf spot, Phaeotrichoconis leaf spot, phyllode rust disease (Atelocauda digitata) and anthracnose (Colletotrichum sp.), as well as stem and root diseases including seedling dumping-off caused by species belonging to Pythium, Rhizoctonia and Fusarium and various agents of canker and dieback [8].

Moreover, extensive literature is focused on the canker and wilt pathogen Ceratocystis, considered an emerging and important threat for Acacia plantations around the world [9,10,11,12,13]. As previously mentioned, in Italy, Acacia species are cultivated for ornamental purposes, which is the reason why the ornamental nurseries represent a crucial point for the detection of diseases that could compromise the propagation processes as well as the longevity of the plants in urban landscapes. In Italy, phytopathological investigations have not been particularly extensive. In this regard, the first disease detected in Italy was in 2001 on A. retinoides, when symptomatic plants showed leaf spot and stem canker, caused by Calonectria pauciramosa (reported as Cylindrocladium pauciramosum) [14]. In 2022, new symptoms of necrotic sunken lesions and wood discoloration were observed at the stem level in both the rootstock and the scion, as well as at the graft union of young plants of A. dealbata grafted on A. retinodes in a nursery in eastern Sicily. Pathogenicity test revealed Lasiodiplodia citricola as the causal agent of the disease [15].

The Botryosphaeriaceae and Diaporthaceae families include important canker pathogens of numerous agricultural, forestry and ornamental crops [16,17]. Symptomatology includes twig and shoot dieback, stem and trunk cankers, bark cracking, gummosis, and tree decline. These pathogens are often defined as opportunistic, able to survive as endophytes within the host tissues until the onset of stress conditions [16,17].

Recently, new surveys conducted in a nursery of eastern Sicily revealed the presence of plants of Acacia arabica (nowadays as Vachellia nilotica), A. farnesiana (V. farnesiana) and P. dulce showing symptoms of twig and shoot canker and dieback. For this reason, the aim of our study was to investigate the etiology of the disease by (i) characterizing the fungal isolates recovered from diseased wood samples based on phylogenetic analyses and (ii) testing their pathogenicity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Surveys and Fungal Isolation

Surveys were carried out in a nursery located in the eastern area of Sicily during 2022. Symptomatic woody samples were collected from ten Acacia plants (five A. arabica plants and five A. farnesiana plants) and five P. dulce plants consisting of necrotized shoot, branch and trunk tissues. After collecting, samples were brought to the laboratory of the Department of Agriculture, Food and Environment, University of Catania, for further analyses. Fungal isolation was conducted as follows: small sections (0.2 to 0.3 cm2) of symptomatic woody tissues were surface-sterilized for 1 min in 1.5% sodium hypochlorite, rinsed in sterile deionized water, dried on sterile absorbent paper under a laminar hood, placed on potato dextrose agar (PDA, Lickson, Vicari, Italy) amended with 100 mg L−1 of streptomycin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) (PDA-S) to prevent bacterial growth, and then incubated at 25 °C for 3–5 days until fungal colonies were large enough to be examined. The isolation frequency (IF) of the main fungal categories was calculated according to the formula IF = (Nfs/Nst) × 100, where Nfs is the number of samples from which the specific fungal category was isolated and Nst is the total number of samples on which fungal isolation was conducted. Subsequently, fungi were grouped according to the general genus-family morphology of the colony (shape, color, texture) and representative colonies of interest were transferred to PDA-S plates. Single-hyphal tip cultures were obtained from pure cultures and maintained on PDA-S at 25 °C. From this preliminary grouping, representative isolates were chosen for molecular characterization.

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification and Sequencing

Fungal isolates were grown on PDA for seven days for the genomic DNA extraction. Mycelium was collected and processed using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit® (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Extracted DNA was stored at 4 °C until use. The following gene regions were selected for amplification and sequencing: the complete internally transcribed spacer region (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2) rDNA gene region with primers ITS5 and ITS4 [18], the translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1) with primers EF1-728F and EF1-986R [19] and EF1-688F and EF1-1251R [20], and the beta-tubulin (tub2) region with primers Bt-2a and Bt-2b [21]. PCR conditions were set as follows: 30 s at 94 °C; 35 cycles each of 30 s at 94 °C; 1 min at 52 °C (ITS) or 55 °C (tef1 and tub2); 1 min at 68 °C; and a final cycle for 5 min at 68 °C. PCR products were visualized on 1% agarose gels (90 V for 40 min) stained with GelRed® Nucleic Acid GelStain (Biotium) to confirm the presence and size of PCR products. PCR amplicons were purified and sequenced in both direction by Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea). The sequencing products were edited with Lasergene SeqMan Pro (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA) and deposited in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Isolates characterized in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Isolates collected from symptomatic Acacia spp. and Pithecellobium dulce plants used in the molecular analyses.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

The sequences obtained in this study were compared with the NCBI GenBank nucleotide database using the standard nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi (accessed on 7 May 2024)). The newly generated sequences of each genomic region were aligned to reference sequences retrieved from recent and comprehensive phylogenetic studies for isolates in the genera Diaporthe [22] and Neofusicoccum [23] and downloaded from GenBank (Table 2). Sequence alignments for phylogenetic analyses were produced with the server version of MAFFT (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/ (accessed on 10 June 2025)) and checked and refined using BioEdit Sequence alignment Editor 7.7.1.0 [24]. Isolates in both genera were used for phylogenetic analyses within a combined matrix of ITS rDNA, tef1 and tub2 sequences. The loci were concatenated to a combined matrix using Phyutility v. 2.2 [25] (Smith and Dunn 2008). Sequences of Botryosphaeria dothidea and B. fabicerciana served as outgroup taxa in phylogenetic analyses of the family Botryosphaeriaceae, and Diaporthella corylina served as the outgroup taxon in phylogenetic analyses of the family Diaporthaceae. Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were performed with RAxML [26], as implemented in raxmlGUI 2.0 [27], using the ML + rapid bootstrap setting and the GTRGAMMA+I substitution model which was selected as the most appropriate model by Modeltest. The matrix was partitioned for the different gene regions, and bootstrap analyses were performed with 1000 bootstrap replicates. For evaluation and interpretation of bootstrap support, values between 70% and 90% were considered moderate, above 90% as high, and 100% as the maximum. Maximum parsimony (MP) bootstrap analyses were performed with Phylogenetic Analyses Using Parsimony (PAUP) v. 4.0a169 [28]. A total of 1000 bootstrap replicates were implemented using five rounds of heuristic search with random sequence addition, followed by tree-bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch swapping. The MULTREES option was enabled, the steepest descent option was disabled, the COLLAPSE command was set to MINBRLEN, and each replicate was limited to 1 million rearrangements. All molecular characters were treated as unordered and assigned equal weight, with gaps considered as missing data. The COLLAPSE command was set to MINBRLEN.

Table 2.

GenBank accession numbers of isolates used in the phylogenetic analyses.

2.4. Pathogenicity Test

Two species of Acacia, including A. arabica and A. farnesiana, and the species P. dulce were selected to conduct pathogenicity tests in order to fulfill Koch’s postulates. Regarding A. arabica and A. farnesiana, a total of six plants for each plant species were inoculated with the fungal isolates. Specifically, three plants were inoculated with D. foeniculina isolate ACA 91, and three plants with N. parvum isolate ACA 82. Likewise, three plants of P. dulce were inoculated with D. foeniculina isolate ACA 113 and three with N. parvum ACA 105. Three plants served as controls. Stem wounds were made with a sterilized 5 mm diameter cork borer to remove the bark, and a 5 mm diameter mycelium plug from a seven-day-old culture of the selected isolates was placed upside down into the wound. Wounds were then sealed with Parafilm® to prevent desiccation. Controls were inoculated with sterile PDA plugs. Plants were regularly watered. Total lesion lengths were measured 60 days after inoculation. Re-isolations were conducted as described above and identification was based on morphological characteristics (color, texture, growth rate and eventually spore features) of the colonies.

3. Results

3.1. Surveys and Fungal Isolation

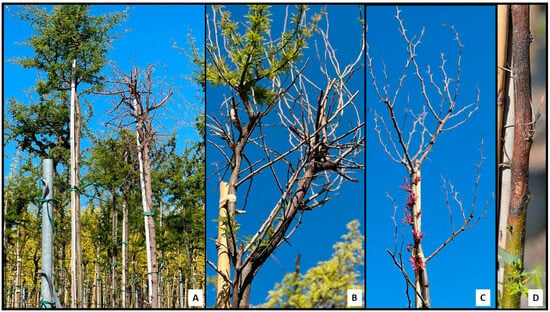

Disease incidence observed in the nursery was about 9% based on a total of 2000 cultivated plants. Specifically, about 6% was observed for Acacia plants and 3% for P. dulce plants. The symptomatology on Acacia spp. and P. dulce consisted of typical apical shoot dieback and general decline of the plants (Figure 1A–D), as well as necrotic patches and external and internal necrotic lesions along the trunks and shoots and at the insertion of the main branches. The isolation frequency from Acacia plants consisted of 62% of Diaporthe-like colonies from dieback symptoms and 21% of Botryosphaeriaceae-like colonies from necrotic lesions on trunks and branches. For P. dulce plants, the isolation frequency showed 85% of Botryosphaeriaceae-like colonies from necrotic lesions on trunks and branches and 60% of Diaporthe-like from twig dieback. From fungal isolation, a total of 46 isolates (32 Diaporthe-like and 14 Neofusicoccum-like) were collected and stored in the fungal collection of the Department of Agriculture, Food and Environment, Laboratory of Plant Pathology. The isolates collected belonging to each genus (Diaporthe and Neofusicoccum) did not show any morphological differences. Thus, a total of 31 representative isolates (23 Diaporthe-like and 8 Neofusicoccum-like) were selected for further molecular analyses.

Figure 1.

Symptomatology of Acacia spp. and Pithecellobium dulce. (A), Acacia spp. plant decline. (B), apical shoot dieback on Acacia plant. (C), P. dulce dieback and canopy defoliation. (D), stem canker and necrosis on Acacia plant.

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

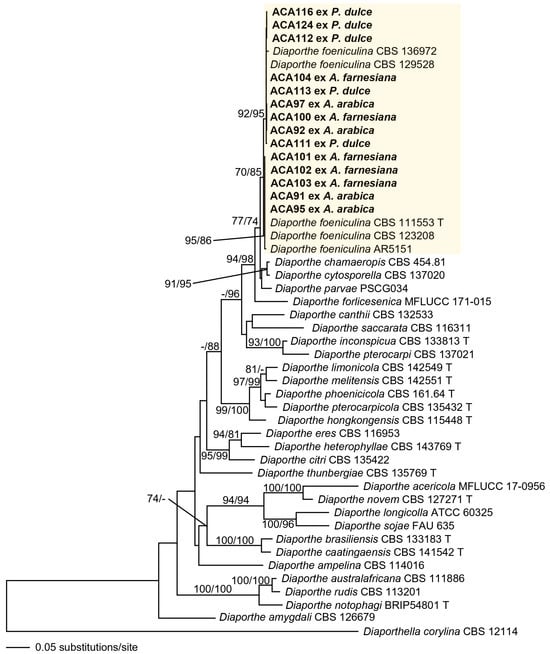

Since the Diaporthe isolates revealed identical sequences for the analyzed loci (ITS, tef1, tub2), except for some ITS polymorphisms, 14 representative isolates were selected for the phylogenetic analyses. The dataset used for the phylogenetic analyses of Diaporthe consisted of 48 taxa, including the isolates from Acacia spp. and P. dulce and the outgroup (D. corylina CBS 121124). The combined matrix of ITS-tef1-tub2 included 1610 characters (597 ITS, 428 tef1, 585 tub2), of which 871 were constant (399 ITS, 132 tef1, 340 tub2), 233 were variable but parsimony-uninformative (85 ITS, 62 tef1, 86 tub2) and 506 were parsimony informative (113 ITS, 134 tef1, 159 tub2). The ML tree (−lnL = 12,314.431617) obtained by RAxML is shown in Figure 2. The isolates ACA 91, ACA92, ACA 95, ACA97, ACA100-104, ACA 111-113, ACA 116 and ACA124 were collected from the symptomatic plants clustered with D. foeniculina with medium support (70% ML, 85% MP). However, two strongly supported lineages were distinguished within this clade, suggesting an intraspecific variability within D. foeniculina isolates.

Figure 2.

Phylogram of the best ML tree (−lnL = 12,314.431617) revealed by RAxML from an analysis of the combined ITS-tef1-tub2 matrix of Diaporthe, showing the phylogenetic position of isolates from diseased Acacia arabica, A. farnesiana and Pithecellobium dulce plants (bold), with Diaporthella corylina (CBS 12114) selected as outgroup to root the tree. Maximum likelihood (ML) and maximum parsimony (MP) bootstrap support above 70% are given at first and second position, respectively, above or below the branches. T = ex-type.

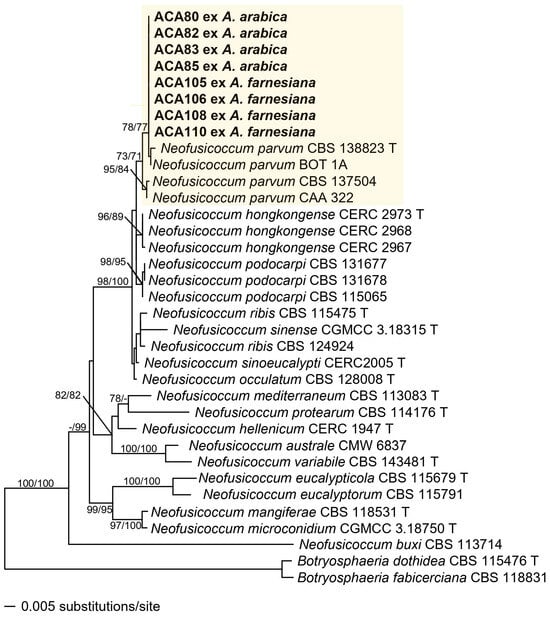

The dataset of Neofusicoccum contained 40 taxa including the isolates from Acacia spp. and P. dulce and the outgroups (Botryosphaeria dothidea CBS 115476 and B. fabicerciana CBS 118831). The alignments included 1255 characters (534 ITS, 306 tef1, 415 tub2) of which 989 were constant (450 ITS, 196 tef1, 343 tub2), 84 were variable but parsimony-uninformative (29 ITS, 30 tef1, 25 tub2) and 182 parsimony informative (55 ITS, 80 tef1, 47 tub2). The ML tree (−lnL = 3893.049301) obtained by RAxML is shown in Figure 3. Maximum likelihood analyses resulted in a tree topology similar to that revealed by MP bootstrap analysis. Phylogenetic analyses did not show intraspecific variability among the ACA isolates, which were all resolved inside the N. parvum s. str. clade with moderate (73% ML, 71% MP) support. However, they were strongly supported (98% ML, 100% MP) within the N. parvum species complex, which includes N. hongkongense, N. occulatum, N. parvum, N. podocarpi, N. ribis and N. sinoeucalypti.

Figure 3.

Phylogram of the best ML tree (−lnL = 3893.049301) revealed by RAxML from an analysis of the combined ITS-tef1-tub2 matrix of Neofusicoccum, showing the phylogenetic position of isolates from diseased Acacia arabica, A. farnesiana and Pithecellobium dulce plants (bold), with Botryosphaeria dothidea (CBS 115476) and B. fabicerciana (CBS 118831) selected as outgroup to root the tree. Maximum likelihood (ML) and maximum parsimony (MP) bootstrap support above 70% are given at first and second position, respectively, above or below the branches. T = ex-type.

3.3. Pathogenicity Test

Results of pathogenicity test proved that both fungal species are pathogenic to Acacia plants as well as to P. dulce although with some slight differences (Figure 4). In particular, D. foeniculina isolate ACA 91 and N. parvum isolate ACA 82 induced lesions on A. arabica with an average length of 5.6 (standard deviation ± 2.4) cm and 5.1 (±2.2) cm, respectively. On A. farnesiana, D. foeniculina isolate ACA 91 induced lesions of an average of 7.5 (±4.7) cm, and N. parvum isolate ACA 82 of 5.7 (±4.1) cm. On P. dulce, D. foeniculina isolate ACA 113 and N. parvum isolate ACA 105 induced lesions of an average of 1.9 ± 1.0 cm and 1.9 ± 0.3 cm, respectively. Of note, gum production was observed from the inoculation point of A. farnesiana plants. Control plants did not produce any lesions, but a superficial discoloration that did not extend beyond the inoculation point was observed due to the oxidation of wounded tissue. Re-isolations from all inoculated plants confirmed the presence of the Diaporthe- and Neofusiccocum-like colonies, with cultural characteristics matching those of the inoculated isolates. No colonies resembling Diaporthe or Neofusicoccum were isolated from control plants.

Figure 4.

Pathogenicity test. From left to right: non-inoculated control plant; external lesion caused by Diaporthe foeniculina isolate ACA 91 on Acacia arabica; gummosis starting from inoculation point of D. foeniculina isolate ACA 91 on Acacia farnesiana; internal lesion caused by D. foeniculina isolate ACA 91 on Acacia arabica; internal lesion on Acacia arabica inoculated with Neofusicoccum parvum isolate ACA 82.

4. Discussion

The results of this study revealed the presence of D. foeniculina and N. parvum, causing cankers and dieback, on A. arabica, A. farnesiana and P. dulce in a nursery located in Sicily, southern Italy. These plant species are cultivated in Italy mainly for ornamental purposes, and some Acacia spp. are also recognized as alien and invasive species. For example, A. saligna was introduced for reforestation purposes and for dune stabilization, but it quickly became an invasive species across the entire national territory [29]. The attention to Acacia is testified in Italy by reforestation programs conducted during the 1950s–1960s in southern Italy with the species A. melanoxylon for its appreciable wood and botanical characteristic in preventing the spread of wildfire [30].

Wood diseases are increasingly becoming the subject of investigation of plant pathologists around the world due to the increasing complexity of their etiology and their wide host range and challenging management [31]. In our study, N. parvum (Botryosphaeriaceae) was consistently isolated from symptomatic tissues of A. arabica and A. farnesiana. This species is widely distributed around the world and well known to be a highly aggressive canker-causing pathogen on many different crops, including ornamental trees [32,33]. Its wide distribution, probably a result of the repeated introductions of agricultural and ornamental plant material [34], and its ability to attack many different hosts, characteristic of several Botryosphaeriaceae [17], make the report of this pathogen significant for the growers. In Sicily, N. parvum has been repeatedly reported in recent decades, demonstrating its highly polyphagous behavior for ornamental [35,36,37,38] and agricultural crops [39,40,41]. This species, with identification based only on the ITS gene region, was reported in Sicily on A. melanoxylon causing canker and dieback in 2016 [30]. However, for a proper identification of Neofusicoccum species, a multi-gene phylogenetic analysis is necessary, especially in the case of N. parvum, which is part of a cryptic species complex [23].

Similarly, the presence of D. foeniculina on both Acacia species is not unusual. Diaporthaceae are recognized as another important group of fungi causing wood diseases on several fruit and nut crops [31], and many associations of Diaporthe species with Acacia have been recorded [42]. Although D. foeniculina is reported worldwide as a primary canker-causing pathogen [43,44], some studies considered it as a weak pathogen, less aggressive compared to other fungal species [41,45,46,47]. On the contrary, in our study, lesions on A. arabica and A. farnesiana caused by D. foeniculina are similar, in terms of length, to those produced by N. parvum. Thus, results of our study do not suggest a clear demarcation between the two identified species in disease development. Discrepancies regarding the observed aggressiveness of the same fungal species around the world may be quite normal and can be attributed to different factors such as differences in isolate virulence and host response.

Concerning P. dulce, this study provides the first report of cankers and dieback caused by D. foeniculina and N. parvum. Until now, only a few diseases have been reported on this host, of which none seemed to be relevant in terms of limitation to its cultivation [5]. The results of our investigation highlight the need to not underestimate the risks derived by the development of wood diseases, especially in nurseries. Canker-causing pathogens, in fact, are characterized by phases of latency during the infection cycle [17] that make it almost impossible to ascertain their presence within the host, unless molecular techniques such as qPCR [48] are used. Latent infections of canker-causing pathogens establishing without notice in the nursery represent the initial inoculum from which further epidemics could develop in new fields [7], especially when plants are subjected to different types of stress like injuries, heat and drought [17]. This epidemiological statement was also evidenced, for example, in the cases of apple canker caused by Nectria galligena, Botryosphaeriaceae diseases on almond and prune, and grapevine infected by several wood pathogens [7,49,50]. In this regard, especially in nurseries and greenhouses, it is crucial to maintain high standards of hygiene during all delicate processes of propagation. Routine sanitation does not guarantee the complete absence of inoculum in plants but could be very helpful in keeping the potential inoculum under control. Monitoring of pathogen populations in diversified environments, like nurseries, where many plant species co-inhabit is crucial to avoid dangerous host jumps and intensification of disease levels.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of D. foeniculina and N. parvum causing canker and dieback on Acacia species and P. dulce worldwide, and these species also should be monitored in other areas where their hosts are planted to evaluate their spread and impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P. and D.A.; methodology, G.R.L., H.V. and L.V.; software, H.V. and G.R.L.; formal analysis, G.R.L. and G.G.; investigation, G.P. and D.A.; resources, G.P.; data curation, G.R.L., H.V. and G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G. and G.R.L.; writing—review and editing, G.P., D.A., G.R.L., G.G., H.V. and L.V.; funding acquisition, G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Piano di incentivi per la ricerca di Ateneo DIME-SIECO 2024–2026 University of Catania (Italy) and by the University of Catania, a PhD grant to Giuseppa Rosaria Leonardi and mobility grants: Erasmus+ project “UNIVERSITIES FOR INNOVATION” (2022-1-IT02-KA131-HED-000055839) and “ERASMUS MOBILITY NETWORK” (2022-1-IT02-KA130-HED-000061416).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yahara, T.; Javadi, F.; Onoda, Y.; de Queiroz, L.P.; Faith, D.P.; Prado, D.E.; Akasaka, M.; Kadoya, T.; Ishihama, F.; Davies, S.; et al. Global Legume Diversity Assessment: Concepts, Key Indicators, and Strategies. Taxon 2013, 62, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.P.; Schrire, B.D.; Mackinder, B.A.; Rico, L.; Clark, R. A 2013 Linear Sequence of Legume Genera Set in a Phylogenetic Context—A Tool for Collections Management and Taxon Sampling. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2013, 89, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, C.; Giovanetti, M.; Foggi, B.; Mariotti Lippi, M. Two Alien Invasive Acacias in Italy: Differences and Similarities in Their Flowering and Insect Visitors. Plant Biosyst.—Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2016, 150, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, S.; Lakshmanan, D.K.; Arumugam, V.; Alexander, R.A. Nutritional and Therapeutic Benefits of Medicinal Plant Pithecellobium Dulce (Fabaceae): A Review. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 9, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boa, E.; Lenn’e, J.M. Diseases of Nitrogen Fixing Trees in Developing Countries: An Annotated List; Natural Resources Institute, Overseas Development Administration: Chatham, UK, 1994; ISBN 0859543757. [Google Scholar]

- Old, K.M.; See, L.S.; Sharma, J.K.; Yuan, Z.Q. A Manual of Diseases of Tropical Acacias in Australia, South-East Asia, and India; Center for International Forestry Research: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2000; ISBN 9798764447. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Niederholzer, F.; Camiletti, B.X.; Michailides, T.J. Survey on Latent Infection of Canker-Causing Pathogens in Budwood and Young Trees from Almond and Prune Nurseries in California. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjahjono, B. Minimising Disease Incidence in Acacia in the Nursery. In Heart Rot and Root Rot in Tropical Plantations; Potter, K., Ed.; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Canberra, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nasution, A.; Glen, M.; Beadle, C.; Mohammed, C. Ceratocystis Wilt and Canker—A Disease That Compromises the Growing of Commercial Acacia-Based Plantations in the Tropics. Aust. For. 2019, 82, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, M.; Roux, J.; Van Wyk, M.; Tjahjono, B.; Wingfield, M.J. A New Wilt and Dieback Disease of Acacia mangium Associated with Ceratocystis manginecans and C. acaciivora sp. nov. in Indonesia. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2011, 77, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, M.; Wingfield, B.; Warburton, P.; Japarudin, Y.; Lapammu, M.; Abdul Rauf, M.; Boden, D.; Barnes, I. Ceratocystis wilt of Acacia mangium in Sabah: Understanding the disease and reducing its impact. J. Trop. For. Sci. 2023, 35, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, J.; Wingfield, M. Ceratocystis Species: Emerging Pathogens of Non-Native Plantation Eucalyptus and Acacia Species. South. For. A J. For. Sci. 2009, 71, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syazwan, S.A.; Mohd-Farid, A.; Wan-Muhd-Azrul, W.-A.; Syahmi, H.M.; Zaki, A.M.; Ong, S.P.; Mohamed, R. Survey, Identification, and Pathogenicity of Ceratocystis fimbriata Complex Associated with Wilt Disease on Acacia mangium in Malaysia. Forests 2021, 12, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzi, G.; Catara, V. First Report of Leaf Spot Caused by Cylindrocladium pauciramosum on Acacia retinodes, Arbutus unedo, Feijoa sellowiana, and Dodonaea viscosa in Southern Italy. Plant Dis. 2001, 85, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.B.; Gusella, G.; Fiorenza, A.; Leonardi, G.R.; Aiello, D.; Polizzi, G. Lasiodiplodia citricola, a New Causal Agent of Acacia Spp. Dieback. New Dis. Rep. 2022, 45, e12094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, R.R.; Glienke, C.; Videira, S.I.R.; Lombard, L.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Diaporthe: A Genus of Endophytic, Saprobic and Plant Pathogenic Fungi. Persoonia—Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2013, 31, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slippers, B.; Wingfield, M.J. Botryosphaeriaceae as Endophytes and Latent Pathogens of Woody Plants: Diversity, Ecology and Impact. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2007, 21, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Michael, A., Innis, D.H., Gelfand, J.J., Sninsky, T.J., Eds.; White Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A Method for Designing Primer Sets for Speciation Studies in Filamentous Ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Crous, P.W.; Correia, A.; Phillips, A.J.L.; Alves, A. Morphological and Molecular Data Reveal Cryptic Speciation in Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Fungal Divers. 2008, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of Primer Sets Designed for Use with the PCR to Amplify Conserved Genes from Filamentous Ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnaccia, V.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Woodhall, J.; Armengol, J.; Cinelli, T.; Eichmeier, A.; Ezra, D.; Fontaine, F.; Gramaje, D.; Gutierrez-Aguirregabiria, A.; et al. Diaporthe Diversity and Pathogenicity Revealed from a Broad Survey of Grapevine Diseases in Europe. Persoonia—Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2018, 40, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Lombard, L.; Schumacher, R.K.; Phillips, A.J.L.; Crous, P.W. Evaluating Species in Botryosphaeriales. Persoonia—Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2021, 46, 63–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.A.; Dunn, C.V. Phyutility: A phyloinformatics tool for trees, alignments and molecular data. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 715–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum Likelihood-Based Phylogenetic Analyses with Thousands of Taxa and Mixed Models. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 2688–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestro, D.; Michalak, I. RaxmlGUI: A Graphical Front-End for RAxML. Org. Divers. Evol. 2012, 12, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swofford, D.L. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods), Version 4.0a165; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Izzi, C.F.; Acosta, A.; Carranza, M.L.; Ciaschetti, G.; Conti, F.; Martino, L.D.; D’orazio, G.; Frattaroli, A.; Pirone, G.; Stanisci, A. Il Censimento Della Flora Vascolare Degli Ambienti Dunali Costieri Dell’Italia Centrale. Fitosociologia 2007, 44, 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sidoti, A. Canker and Decline Caused by Neofusiccocum parvum on Acacia melanoxylon in Italy. For.—Riv. Di Selvic. Ed Ecol. For. 2016, 13, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnaccia, V.; Kraus, C.; Markakis, E.; Alves, A.; Armengol, J.; Eichmeier, A.; Compant, S.; Gramaje, D. Fungal Trunk Diseases of Fruit Trees in Europe: Pathogens, Spread and Future Directions. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2023, 61, 563–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatković, M.; Keča, N.; Wingfield, M.J.; Jami, F.; Slippers, B. Botryosphaeriaceae Associated with the DieBack of Ornamental Trees in the Western Balkans. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2016, 109, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.N.; Roux, J.; Slippers, B.; Drenth, A.; Pennycook, S.R.; Wingfield, B.D.; Wingfield, M.J. Occurrence and Pathogenicity of Neofusicoccum parvum and N. mangiferae on Ornamental Tibouchina Species. For. Pathol. 2011, 41, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalidis, M.L.; Slippers, B.; Wingfield, B.D.; Hardy, G.S.J.; Burgess, T.I. The Challenge of Understanding the Origin, Pathways and Extent of Fungal Invasions: Global Populations of the Neofusicoccum parvum–N. ribis Species Complex. Divers. Distrib. 2013, 19, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusella, G.; Costanzo, M.B.; Aiello, D.; Polizzi, G. Characterization of Neofusicoccum parvum Causing Canker and Dieback on Brachychiton Species. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 161, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusella, G.; Aiello, D.; Polizzi, G. First Report of Leaf and Twig Blight of Indian Hawthorn (Rhaphiolepis indica) Caused by Neofusicoccum parvum in Italy. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 102, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusella, G.; Di Pietro, C.; Leonardi, G.R.; Aiello, D.; Polizzi, G. Canker and Dieback of Camphor Tree (Cinnamomum camphora) Caused by Botryosphaeriaceae in Italy. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 105, 1675–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, D.; Gusella, G.; Fiorenza, A.; Guarnaccia, V.; Polizzi, G. Identification of Neofusicoccum parvum Causing Canker and Twig Blight on Ficus carica in Italy. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2020, 59, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorenza, A.; Gusella, G.; Vecchio, L.; Aiello, D.; Polizzi, G. Diversity of Botryosphaeriaceae Species Associated with Canker and Dieback of Avocado (Persea americana) in Italy. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2023, 62, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnaccia, V.; Vitale, A.; Cirvilleri, G.; Aiello, D.; Susca, A.; Epifani, F.; Perrone, G.; Polizzi, G. Characterisation and Pathogenicity of Fungal Species Associated with Branch Cankers and Stem-End Rot of Avocado in Italy. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 146, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusella, G.; Leonardi, G.R.; La Quatra, G.; Aiello, D.; Voglmayr, H.; Polizzi, G. Re-Evaluating the Etiology of Citrus “Dothiorella Gummosis” in Italy. Plant Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fungal Database. Available online: https://Fungi.Ars.Usda.Gov (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Annesi, T.; Luongo, L.; Vitale, S.; Galli, M.; Belisario, A. Characterization and Pathogenicity of Phomopsis theicola Anamorph of Diaporthe foeniculina Causing Stem and Shoot Cankers on Sweet Chestnut in Italy. J. Phytopathol. 2016, 164, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathioudakis, M.M.; Tziros, G.T.; Kavroulakis, N. First Report of Diaporthe foeniculina Associated with Branch Canker of Avocado in Greece. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusella, G.; Gugliuzzo, A.; Guarnaccia, V.; Martino, I.; Aiello, D.; Costanzo, M.B.; Russo, A.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W.; Polizzi, G. Fungal Species Causing Canker and Wilt of Ficus carica and Evidence of Their Association by Bark Beetles in Italy. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 2136–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, M.; Berbegal, M.; Rodríguez-Reina, J.M.; Elena, G.; Abad-Campos, P.; Ramón-Albalat, A.; Olmo, D.; Vicent, A.; Luque, J.; Miarnau, X.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Diaporthe Spp. Associated with Twig Cankers and Shoot Blight of Almonds in Spain. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnaccia, V.; Crous, P.W. Emerging Citrus Diseases in Europe Caused by Species of Diaporthe. IMA Fungus 2017, 8, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Gu, S.; Felts, D.; Puckett, R.D.; Morgan, D.P.; Michailides, T.J. Development of QPCR Systems to Quantify Shoot Infections by Canker-Causing Pathogens in Stone Fruits and Nut Crops. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 122, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Jaime, A.; Aroca, A.; Raposo, R.; García-Jiménez, J.; Armengol, J. Occurrence of Fungal Pathogens Associated with Grapevine Nurseries and the Decline of Young Vines in Spain. J. Phytopathol. 2006, 154, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, A.R.; Berrie, A.; Barbara, D.J.; Locke, T.; Cooke, L.R.; Phelps, K.; Swinburne, T.R.; Brown, A.E.; Ellerker, B.; Langrell, S.R.H. Relative Significance of Nursery Infections and Orchard Inoculum in the Development and Spread of Apple Canker (Nectria galligena) in Young Orchards. Plant Pathol. 2003, 52, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).