Drug Discovery and Repurposing for Coccidioides: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

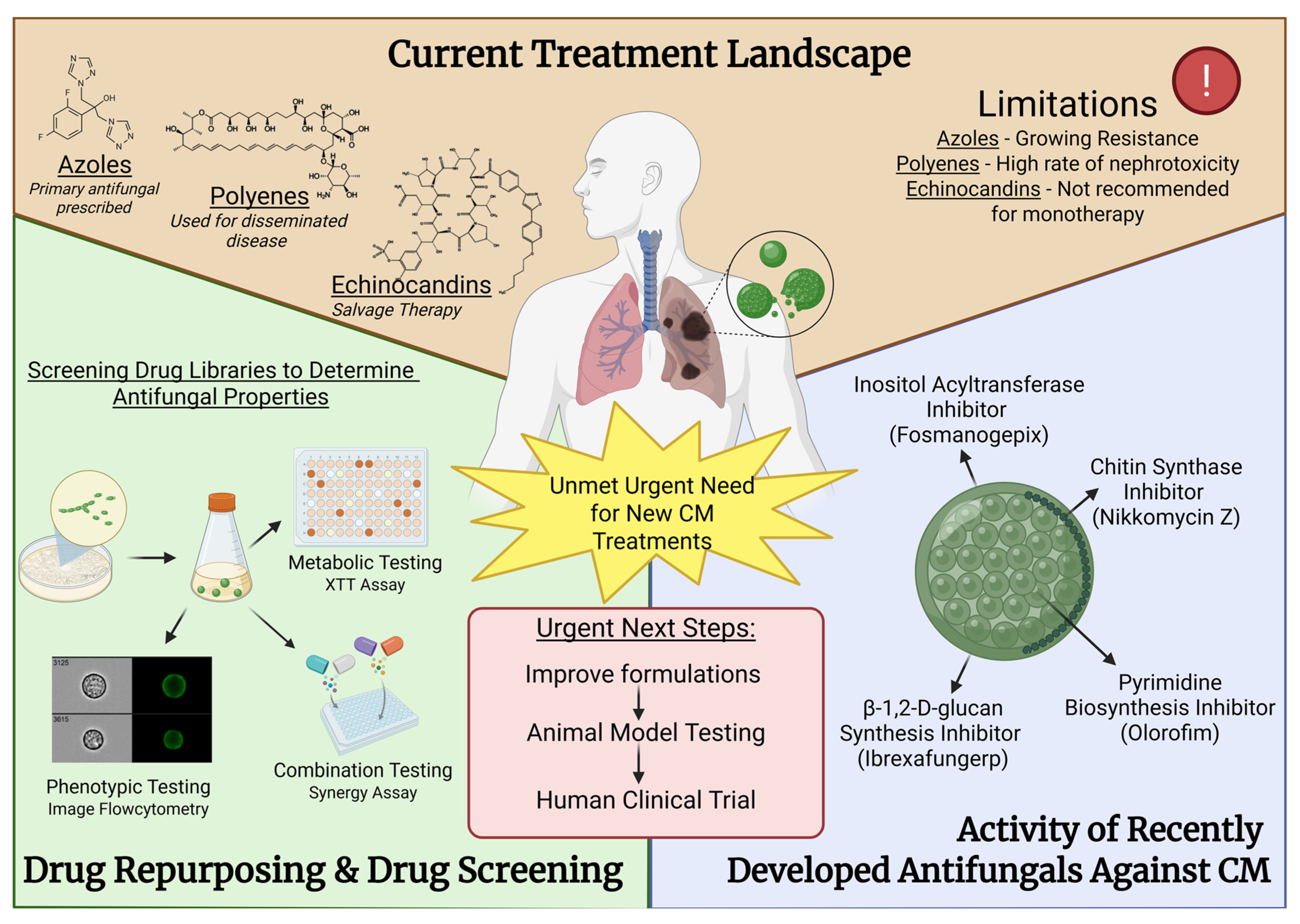

2. The Current Treatment Landscape

2.1. Azoles

2.2. Polyenes

2.3. Echinocandins

2.4. Pyrimidines

2.5. Unmet Needs

3. Discovery and Development of Novel Chemotherapies for CM

3.1. Chitin Synthase Inhibitors

3.2. Olorofim

3.3. Ibrexafungerp

3.4. Fosmanogepix

4. Emerging Drug Discovery Strategies

4.1. Drug Repurposing and Drug Screening

4.2. Anti-Infective Agents

4.3. Antineoplastic Agents

4.4. Anti-Inflammatory Agents

4.5. Neurologic Agents

4.6. Analgesics and Miscellaneous

5. In Vivo Models and Translational Tools

6. Challenges and Opportunities

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List to Guide Research, Development and Public Health Action. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060241 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Areas with Valley Fever. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/valley-fever/areas/index.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Laniado-Laborin, R. Expanding Understanding of Epidemiology of Coccidioidomycosis in the Western Hemisphere. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1111, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Reportable Fungal Diseases by State. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/php/case-reporting/index.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Gorris, M.E.; Ardon-Dryer, K.; Campuzano, A.; Castañón-Olivares, L.R.; Gill, T.E.; Greene, A.; Hung, C.Y.; Kaufeld, K.A.; Lacy, M.; Sánchez-Paredes, E. Advocating for Coccidioidomycosis to Be a Reportable Disease Nationwide in the United States and Encouraging Disease Surveillance across North and South America. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.L.; Chiller, T. Update on the Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camponuri, S.K.; Heaney, A.K.; Cooksey, G.S.; Vugia, D.J.; Jain, S.; Swain, D.L.; Balmes, J.; Remais, J.V.; Head, J.R. Recent and Forecasted Increases in Coccidioidomycosis Incidence Linked to Hydroclimatic Swings, California, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 1028–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Reported Cases of Valley Fever. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/valley-fever/php/statistics/index.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- California Department of Public Health. Substantial Rise in Coccidioidomycosis in California: Recommendations for California Healthcare Providers. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/OPA/Pages/CAHAN/Substantial-Rise-in-Coccidioidomycosis-in-California-Recommendations-for-California-Healthcare-Providers.aspx (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- U.S. Census Bureau. 65 and Older Population Grows Rapidly as Baby Boomers Age. Available online: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/65-older-population-grows.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Cole, G.T.; Sun, S.H. Arthroconidium-Spherule-Endospore Transformation in Coccidioides immitis. In Fungal Dimorphism: With Emphasis on Fungi Pathogenic for Humans; Szaniszlo, P.J., Harris, J.L., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 281–333. [Google Scholar]

- Deresinski, S.; Mirels, L.F. Coccidioidomycosis: What a long strange trip it’s been. Med. Mycol. 2019, 57, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, F.M.; Shubitz, L.; Powell, D.; Orbach, M.; Frelinger, J.; Galgiani, J.N. Early Events in Coccidioidomycosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 33, e00112-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, S.M.; Koirala, J. Coccidioidomycosis; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia, L.; Nix, D.; Wright, M.; Lindberg, E.; Fagan, T.; Lieberman, D.; Stoffer, T.; Ampel, N.M.; Galgiani, J.N. Coccidioidomycosis as a common cause of community-acquired pneumonia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 958–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgiani, J.N.; Ampel, N.M.; Blair, J.E.; Catanzaro, A.; Geertsma, F.; Hoover, S.E.; Johnson, R.H.; Kusne, S.; Lisse, J.; MacDonald, J.D.; et al. 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2016, 63, e112–e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Clinical Overview of Valley Fever. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/valley-fever/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Barnes, R.A. Early diagnosis of fungal infection in immunocompromised patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 61, i3–i6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman Weiss, Z.; Leon, A.; Koo, S. The Evolving Landscape of Fungal Diagnostics, Current and Emerging Microbiological Approaches. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozel, T.R.; Wickes, B. Fungal diagnostics. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a019299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Testing Algorithm for Coccidioidomycosis. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/valley-fever/hcp/testing-algorithm/index.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Donovan, F.M.; Zangeneh, T.T.; Malo, J.; Galgiani, J.N. Top Questions in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2017, 4, ofx197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valley Fever Center for Excellence. Order the Right Tests. Available online: https://vfce.arizona.edu/valley-fever-people/order-right-tests (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Mitchell, M.; Dizon, D.; Libke, R.; Peterson, M.; Slater, D.; Dhillon, A. Development of a Real-Time PCR Assay for Identification of Coccidioides immitis by Use of the BD Max System. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saubolle, M.A.; Wojack, B.R.; Wertheimer, A.M.; Fuayagem, A.Z.; Young, S.; Koeneman, B.A. Multicenter Clinical Validation of a Cartridge-Based Real-Time PCR System for Detection of Coccidioides spp. in Lower Respiratory Specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e01277-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, G.R.; Sharma, S.; Bays, D.J.; Pruitt, R.; Engelthaler, D.M.; Bowers, J.; Driebe, E.M.; Davis, M.; Libke, R.; Cohen, S.H.; et al. Coccidioidomycosis: Adenosine Deaminase Levels, Serologic Parameters, Culture Results, and Polymerase Chain Reaction Testing in Pleural Fluid. Chest 2013, 143, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ampel, N.M. The treatment of Coccidioidomycosis. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2015, 57 (Suppl. 19), 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valley Fever Center for Excellence. Antifungal Therapy. Available online: https://health.ucdavis.edu/valley-fever/about-valley-fever/treatment-antifungal-therapy/index.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Thompson, G.R., 3rd; Barker, B.M.; Wiederhold, N.P. Large-Scale Evaluation of In Vitro Amphotericin B, Triazole, and Echinocandin Activity against Coccidioides Species from U.S. Institutions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02634-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hof, H. A new, broad-spectrum azole antifungal: Posaconazole–mechanisms of action and resistance, spectrum of activity. Mycoses 2006, 49, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mølgaard-Nielsen, D.; Pasternak, B.; Hviid, A. Use of Oral Fluconazole during Pregnancy and the Risk of Birth Defects. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); European Chemicals Agency (ECHA); European Environment Agency (EEA); European Medicines Agency (EMA); European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC). Impact of the use of azole fungicides, other than as human medicines, on the development of azole-resistant Aspergillus spp. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.E.; Sumabat, L.G.; Melie, T.; Mangum, B.; Momany, M.; Brewer, M.T. Evidence for the agricultural origin of resistance to multiple antimicrobials in Aspergillus fumigatus, a fungal pathogen of humans. G3 (Bethesda) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, R.; Montoya, L.; Head, J.R.; Campo, S.; Remais, J.; Taylor, J.W. Coccidioides undetected in soils from agricultural land and uncorrelated with time or the greater soil fungal community on undeveloped land. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, F.M.; Fernández, O.M.; Bains, G.; DiPompo, L. Coccidioidomycosis: A growing global concern. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, i40–i49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizzle, A.J.; Wilson, L.; Nix, D.E.; Galgiani, J.N. Clinical and Economic Burden of Valley Fever in Arizona: An Incidence-Based Cost-of-Illness Analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofaa623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.; Ting, J.; Lin, H.; Shah, R.; MacLean, M.; Peterson, M.W.; Stockamp, N.; Libke, R.; Brown, P. The Rise of Valley Fever: Prevalence and Cost Burden of Coccidioidomycosis Infection in California. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutserimpas, C.; Naoum, S.; Raptis, K.; Vrioni, G.; Samonis, G.; Alpantaki, K. Skeletal Infections Caused by Coccidioides Species. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galgiani, J.N.; Catanzaro, A.; Cloud, G.A.; Johnson, R.H.; Williams, P.L.; Mirels, L.F.; Nassar, F.; Lutz, J.E.; Stevens, D.A.; Sharkey, P.K.; et al. Comparison of Oral Fluconazole and Itraconazole for Progressive, Nonmeningeal Coccidioidomycosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000, 133, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamberi, P.; Sobel, R.A.; Clemons, K.V.; Waldvogel, A.; Striebel, J.M.; Williams, P.L.; Stevens, D.A. Comparison of Itraconazole and Fluconazole Treatments in a Murine Model of Coccidioidal Meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spec, A.; Thompson, G.R.; Miceli, M.H.; Hayes, J.; Proia, L.; McKinsey, D.; Arauz, A.B.; Mullane, K.; Young, J.-A.; McGwin, G.; et al. MSG-15: Super-Bioavailability Itraconazole Versus Conventional Itraconazole in the Treatment of Endemic Mycoses—A Multicenter, Open-Label, Randomized Comparative Trial. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofae010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Vanderwyk, K.A.; Donnelley, M.A.; Thompson Iii, G.R. SUBA-itraconazole in the treatment of systemic fungal infections. Future Microbiol. 2024, 19, 1171–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). New Drug Application (NDA): 208901 (Tolsura/Itraconazole). Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=208901 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Pappas, P.G.; Spec, A.; Miceli, M.; McGwin, G.; McMullen, R.; Thompson, G.R.R., III. 120. An open-label comparative trial of SUBA-itraconazole (SUBA) versus conventional itraconazole (c-itra) for treatment of proven and probable endemic mycoses (MSG-15): A pharmacokinetic (PK) and adverse Event (AE) analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipp, H.P. Clinical pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the antifungal extended-spectrum triazole posaconazole: An overview. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 70, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.M.; Vikram, H.R.; Kusne, S.; Seville, M.T.; Blair, J.E. Treatment of Refractory Coccidioidomycosis with Voriconazole or Posaconazole. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, D.A.; Rendon, A.; Gaona-Flores, V.; Catanzaro, A.; Anstead, G.M.; Pedicone, L.; Graybill, J.R. Posaconazole Therapy for Chronic Refractory Coccidioidomycosis. Chest 2007, 132, 952–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, G.M. In vitro activities of isavuconazole against Opportunistic filamentous and Dimorphic fungi. Med. Mycol. 2009, 47, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.S.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Hakki, M.; Thompson, G.R. New Perspectives on Antimicrobial Agents: Isavuconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0017722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Quinlan, M.; Benjamin, D.J.; Laurence, B.; Mu, A.; Ngai, T.; Hoffman, W.J.; Cohen, S.H.; McHardy, I.; Johnson, R.; et al. Isavuconazole in the Treatment of Coccidioidal Meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02232-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Sharma, R.; Shakir, Q.; Shah, M.; Clement, J.; Donnelley, M.A.; Reynolds, T.; Trigg, K.; Jolliff, J.; Kuran, R.; et al. Isavuconazole in the Treatment of Chronic Forms of Coccidioidomycosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 2196–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.R., III; Rendon, A.; Ribeiro dos Santos, R.; Queiroz-Telles, F.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Azie, N.; Maher, R.; Lee, M.; Kovanda, L.; Engelhardt, M.; et al. Isavuconazole Treatment of Cryptococcosis and Dimorphic Mycoses. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). New Drug Application (NDA): 207500 (Cresemba/Isavuconazonium Sulfate). Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=207500 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Kovanda, L.L.; Sass, G.; Martinez, M.; Clemons, K.V.; Nazik, H.; Kitt, T.M.; Wiederhold, N.; Hope, W.W.; Stevens, D.A. Efficacy and Associated Drug Exposures of Isavuconazole and Fluconazole in an Experimental Model of Coccidioidomycosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e02344-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Patterson, H.P.; Tran, B.H.; Yates, C.M.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Garvey, E.P. Fungal-specific Cyp51 inhibitor VT-1598 demonstrates in vitro activity against Candida and Cryptococcus species, endemic fungi, including Coccidioides species, Aspergillus species and Rhizopus arrhizus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, E.P.; Sharp, A.D.; Warn, P.A.; Yates, C.M.; Atari, M.; Thomas, S.; Schotzinger, R.J. The novel fungal CYP51 inhibitor VT-1598 displays classic dose-dependent antifungal activity in murine models of invasive aspergillosis. Med. Mycol. 2019, 58, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, E.P.; Sharp, A.D.; Warn, P.A.; Yates, C.M.; Schotzinger, R.J. The novel fungal CYP51 inhibitor VT-1598 is efficacious alone and in combination with liposomal amphotericin B in a murine model of cryptococcal meningitis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2815–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Break, T.J.; Desai, J.V.; Healey, K.R.; Natarajan, M.; Ferre, E.M.N.; Henderson, C.; Zelazny, A.; Siebenlist, U.; Yates, C.M.; Cohen, O.J.; et al. VT-1598 inhibits the in vitro growth of mucosal Candida strains and protects against fluconazole-susceptible and -resistant oral candidiasis in IL-17 signalling-deficient mice. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2089–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Lockhart, S.R.; Najvar, L.K.; Berkow, E.L.; Jaramillo, R.; Olivo, M.; Garvey, E.P.; Yates, C.M.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Catano, G.; et al. The Fungal Cyp51-Specific Inhibitor VT-1598 Demonstrates In Vitro and In Vivo Activity against Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02233-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, K.; Spitz, R.; Hammett, E.; Jaunarajs, A.; Ghazaryan, V.; Garvey, E.P.; Degenhardt, T. Safety and pharmacokinetics of antifungal agent VT-1598 and its primary metabolite, VT-11134, in healthy adult subjects: Phase 1, first-in-human, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of single-ascending oral doses of VT-1598. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, S.R.; Degenhardt, T.P.; Person, K.; Sobel, J.D.; Nyirjesy, P.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Tavakkol, A. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of orally administered VT-1161 in the treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 624.e1–624.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, M.G.; Maximos, B.; Degenhardt, T.; Person, K.; Curelop, S.; Ghannoum, M.; Flynt, A.; Brand, S.R. Phase 3 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of oteseconazole in the treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis and acute vulvovaginal candidiasis infections. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 227, 880.e1–880.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimoto, A.T.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Flowers, S.A.; Zhang, Q.; Kelly, S.L.; Morschhäuser, J.; Yates, C.M.; Hoekstra, W.J.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Garvey, E.P.; et al. In Vitro Activities of the Novel Investigational Tetrazoles VT-1161 and VT-1598 Compared to the Triazole Antifungals against Azole-Resistant Strains and Clinical Isolates of Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e00341-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schell, W.A.; Jones, A.M.; Garvey, E.P.; Hoekstra, W.J.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Alexander, B.D. Fungal CYP51 Inhibitors VT-1161 and VT-1129 Exhibit Strong In Vitro Activity against Candida glabrata and C. krusei Isolates Clinically Resistant to Azole and Echinocandin Antifungal Compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e01817-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, T.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Fothergill, A.W.; Garvey, E.P.; Hoekstra, W.J.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Patterson, T.F.; Filler, S.G.; Ibrahim, A.S. VT-1161 Protects Immunosuppressed Mice from Rhizopus arrhizus var. arrhizus Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 7815–7817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elewski, B.; Brand, S.; Degenhardt, T.; Curelop, S.; Pollak, R.; Schotzinger, R.; Tavakkol, A.; Alonso-Llamazares, J.; Ashton, S.J.; Bhatia, N.; et al. A phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of VT-1161 oral tablets in the treatment of patients with distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis of the toenail. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubitz, L.F.; Roy, M.E.; Trinh, H.T.; Hoekstra, W.J.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Garvey, E.P. Efficacy of the Investigational Antifungal VT-1161 in Treating Naturally Occurring Coccidioidomycosis in Dogs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00111-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shubitz, L.F.; Trinh, H.T.; Galgiani, J.N.; Lewis, M.L.; Fothergill, A.W.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Barker, B.M.; Lewis, E.R.G.; Doyle, A.L.; Hoekstra, W.J.; et al. Evaluation of VT-1161 for Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis in Murine Infection Models. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 7249–7254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, J.D.; Nyirjesy, P. Oteseconazole: An Advance in Treatment of Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Future Microbiol. 2021, 16, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, R.J. Amphotericin B Formulations: A Comparative Review of Efficacy and Toxicity. Drugs 2013, 73, 919–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, S.M. 3 Biological Activity of Polyene Antibiotics. In Progress in Medicinal Chemistry; Ellis, G.P., West, G.B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; Volume 14, pp. 105–179. [Google Scholar]

- Abelcet. Abelcet® (Amphotericin B Lipid Complex Injection). Available online: https://leadiant.com/products/abelcet/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- AmBisome. Turn to the Liposomal Amphotericin B Agent That Can Be Kinder to the Kidneys. Available online: https://www.ambisome.com/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Groll, A.H.; Rijnders, B.J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; Adler-Moore, J.; Lewis, R.E.; Brüggemann, R.J.M. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, Safety and Efficacy of Liposomal Amphotericin B. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2019, 68, S260–S274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.; Preuss, C.V. Amphotericin B; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro, R.A.; Brilhante, R.S.N.; Rocha, M.F.G.; Fechine, M.A.B.; Costa, A.K.F.; Camargo, Z.P.; Sidrim, J.J.C. In vitro Activities of Caspofungin, Amphotericin B and Azoles Against Coccidioides posadasii Strains from Northeast, Brazil. Mycopathologia 2006, 161, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakai, T.; Uno, J.; Ikeda, F.; Tawara, S.; Nishimura, K.; Miyaji, M. In vitro antifungal activity of Micafungin (FK463) against dimorphic fungi: Comparison of yeast-like and mycelial forms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 1376–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramani, R.; Chaturvedi, V. Antifungal susceptibility profiles of Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii from endemic and non-endemic areas. Mycopathologia 2007, 163, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, G.M.; Gonzalez, G.; Najvar, L.K.; Graybill, J.R. Therapeutic efficacy of caspofungin alone and in combination with amphotericin B deoxycholate for coccidioidomycosis in a mouse model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, G.M.; Tijerina, R.; Najvar, L.K.; Bocanegra, R.; Luther, M.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Graybill, J.R. Correlation between antifungal susceptibilities of Coccidioides immitis in vitro and antifungal treatment with caspofungin in a mouse model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 1854–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, E.R.; McCarty, J.M.; Shane, A.L.; Weintrub, P.S. Treatment of pediatric refractory coccidioidomycosis with combination voriconazole and caspofungin: A retrospective case series. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2013, 56, 1573–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermes, A.; Guchelaar, H.-J.; Dankert, J. Flucytosine: A review of its pharmacology, clinical indications, pharmacokinetics, toxicity and drug interactions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000, 46, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigera, L.S.M.; Denning, D.W. Flucytosine and its clinical usage. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, 20499361231161387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelty, M.T.; Miron-Ocampo, A.; Beattie, S.R. A series of pyrimidine-based antifungals with anti-mold activity disrupt ER function in Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e01045-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dähn, U.; Hagenmaier, H.; Höhne, H.; König, W.A.; Wolf, G.; Zähner, H. Stoffwechselprodukte von mikroorganismen. 154. Mitteilung. Nikkomycin, ein neuer hemmstoff der chitinsynthese bei pilzen. Arch. Microbiol. 1976, 107, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larwood, D.J. Nikkomycin Z—Ready to Meet the Promise? J. Fungi 2020, 6, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hector, R.F.; Pappagianis, D. Inhibition of chitin synthesis in the cell wall of Coccidioides immitis by polyoxin D. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 154, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sass, G.; Larwood, D.J.; Martinez, M.; Chatterjee, P.; Xavier, M.O.; Stevens, D.A. Nikkomycin Z against Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis in a Murine Model of Sustained-Release Dosing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0028521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Najvar, L.K.; Jaramillo, R.; Olivo, M.; Larwood, D.J.; Patterson, T.F. Evaluation of nikkomycin Z with frequent oral administration in an experimental model of central nervous system coccidioidomycosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0135624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubitz, L.F.; Roy, M.E.; Nix, D.E.; Galgiani, J.N. Efficacy of Nikkomycin Z for respiratory coccidioidomycosis in naturally infected dogs. Med. Mycol. 2013, 51, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubitz, L.F.; Trinh, H.T.; Perrill, R.H.; Thompson, C.M.; Hanan, N.J.; Galgiani, J.N.; Nix, D.E. Modeling nikkomycin Z dosing and pharmacology in murine pulmonary coccidioidomycosis preparatory to phase 2 clinical trials. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, 1949–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiederhold, N.P. Review of the Novel Investigational Antifungal Olorofim. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, J.D.; Sibley, G.E.M.; Beckmann, N.; Dobb, K.S.; Slater, M.J.; McEntee, L.; du Pré, S.; Livermore, J.; Bromley, M.J.; Wiederhold, N.P.; et al. F901318 represents a novel class of antifungal drug that inhibits dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12809–12814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Najvar, L.K.; Jaramillo, R.; Olivo, M.; Birch, M.; Law, D.; Rex, J.H.; Catano, G.; Patterson, T.F. The Orotomide Olorofim Is Efficacious in an Experimental Model of Central Nervous System Coccidioidomycosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e00999-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenigl, M.; Sprute, R.; Egger, M.; Arastehfar, A.; Cornely, O.A.; Krause, R.; Lass-Florl, C.; Prattes, J.; Spec, A.; Thompson, G.R., 3rd; et al. The Antifungal Pipeline: Fosmanogepix, Ibrexafungerp, Olorofim, Opelconazole, and Rezafungin. Drugs 2021, 81, 1703–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallow, S.; Govender, N.P. Ibrexafungerp: A First-in-Class Oral Triterpenoid Glucan Synthase Inhibitor. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, G.T.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L. Investigational Agents for the Treatment of Resistant Yeasts and Molds. Curr. Fungal. Infect. Rep. 2021, 15, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, E.; Yasinskaya, Y.; Dixon, C.; Higgins, K.; Moore, J.; Reynolds, K.; Ampel, N.M.; Angulo, D.; Blair, J.E.; Catanzaro, A.; et al. FDA Public Workshop Summary—Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever): Considerations for Development of Antifungal Drugs. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 74, 2061–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, D. Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever): Considerations for Development of Antifungal Drugs. In Proceedings of the Development Considerations for Coccidioidomycosis, Virtual, 5 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, M.; Horii, T.; Hata, K.; Watanabe, N.-a.; Nakamoto, K.; Tanaka, K.; Shirotori, S.; Murai, N.; Inoue, S.; Matsukura, M.; et al. In Vitro Activity of E1210, a Novel Antifungal, against Clinically Important Yeasts and Molds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4652–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukahara, K.; Hata, K.; Nakamoto, K.; Sagane, K.; Watanabe, N.-a.; Kuromitsu, J.; Kai, J.; Tsuchiya, M.; Ohba, F.; Jigami, Y.; et al. Medicinal genetics approach towards identifying the molecular target of a novel inhibitor of fungal cell wall assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 48, 1029–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.-a.; Miyazaki, M.; Horii, T.; Sagane, K.; Tsukahara, K.; Hata, K. E1210, a New Broad-Spectrum Antifungal, Suppresses Candida albicans Hyphal Growth through Inhibition of Glycosylphosphatidylinositol Biosynthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 960–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, K.J.; Ibrahim, A.S. Fosmanogepix: A Review of the First-in-Class Broad Spectrum Agent for the Treatment of Invasive Fungal Infections. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viriyakosol, S.; Kapoor, M.; Okamoto, S.; Covel, J.; Soltow, Q.A.; Trzoss, M.; Shaw, K.J.; Fierer, J. APX001 and Other Gwt1 Inhibitor Prodrugs Are Effective in Experimental Coccidioides immitis Pneumonia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01715-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Cheng, L.W.; Chan, K.L.; Tam, C.C.; Mahoney, N.; Friedman, M.; Shilman, M.M.; Land, K.M. Antifungal Drug Repurposing. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Thorne, N.; McKew, J.C. Phenotypic screens as a renewed approach for drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeger, S.; West-Jeppson, K.; Liao, Y.-R.; Campuzano, A.; Yu, J.-J.; Lopez-Ribot, J.; Hung, C.-Y. Discovery of novel antifungal drugs via screening repurposing libraries against Coccidioides posadasii spherule initials. mBio 2025, 16, e0020525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Rodriguez, A.; Yu, J.-J.; Hung, C.-Y.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Development and Optimization of Multi-Well Colorimetric Assays for Growth of Coccidioides posadasii Spherules and Their Application in Large-Scale Screening. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, C.L.; Esqueda, M.; Yu, J.-J.; Wall, G.; Romo, J.A.; Vila, T.; Chaturvedi, A.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L.; Wormley, F.; Hung, C.-Y. Development of an Imaging Flow Cytometry Method for Fungal Cytological Profiling and Its Potential Application in Antifungal Drug Development. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, H.L.; Valentine, M.; Yin, H.; III, G.R.T.; Keim, P.; Engelthaler, D.M.; Barker, B.M. In vitro small molecule screening to inform novel Candidates for use in fluconazole combination therapy in vivo against Coccidioides. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0100824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biersack, B. The Antifungal Potential of Niclosamide and Structurally Related Salicylanilides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, G.E. The Pharmacology of Halogenated Salicylanilides and Their Anthelmintic Use in Animals. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 1999, 70, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Paes, R.; de Andrade, I.B.; Ramos, M.L.M.; Rodrigues, M.V.A.; do Nascimento, V.A.; Bernardes-Engemann, A.R.; Frases, S. Medicines for Malaria Venture COVID Box: A source for repurposing drugs with antifungal activity against human pathogenic fungi. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2021, 116, e210207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preuett, B.; Leeder, J.S.; Abdel-Rahman, S. Development and Application of a High-Throughput Screening Method to Evaluate Antifungal Activity against Trichophyton tonsurans. SLAS Discov. 2015, 20, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, M.O.; Williams Iii, R.O. The challenge of repurposing niclosamide: Considering pharmacokinetic parameters, routes of administration, and drug metabolism. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 81, 104187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafiz, S.; Kyriakopoulos, C. Pentamidine. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). New Drug Application (NDA): 019887 (Nebupent/Pentamidine Isethionate). Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- de Oliveira, H.C.; Castelli, R.F.; Alves, L.R.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Salama, E.A.; Seleem, M.; Rodrigues, M.L. Identification of four compounds from the Pharmakon library with antifungal activity against Candida auris and species of Cryptococcus. Med. Mycol. 2022, 60, myac033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionakis, M.S.; Chamilos, G.; Lewis, R.E.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Raad, I.I.; Samonis, G.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Pentamidine Is Active in a Neutropenic Murine Model of Acute Invasive Pulmonary Fusariosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, F.; Schmitt, T.; Schwarz, M. Pentamidine, an inhibitor of spinal flexor reflexes in rats, is a potent N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist in vivo. Neurosci. Lett. 1993, 155, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihisa, K.; Takashi, A.; Rei, I.; Taiji, S.; Yasuyuki, N. Inhibition of constitutive nitric oxide synthase in the brain by pentamidine, a calmodulin antagonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995, 289, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 50248, Triclabendazole. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Triclabendazole (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Roskoski, R. The role of small molecule platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) inhibitors in the treatment of neoplastic disorders. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 129, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.W.; Tay, S.T. The inhibitory effects of aureobasidin A on Candida planktonic and biofilm cells. Mycoses 2013, 56, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wåhlén, E.; Olsson, F.; Raykova, D.; Söderberg, O.; Heldin, J.; Lennartsson, J. Activated EGFR and PDGFR internalize in separate vesicles and downstream AKT and ERK1/2 signaling are differentially impacted by cholesterol depletion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 665, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu-Lowe, D.D.; Grazzini, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, W.-Z.; Laird, D.; Patyna, S. SU014813 is a novel multireceptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor with potent antiangiogenic and antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 475. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.D.; Kaufman, M.D.; Lu, W.-P.; Gupta, A.; Leary, C.B.; Wise, S.C.; Rutkoski, T.J.; Ahn, Y.M.; Al-Ani, G.; Bulfer, S.L.; et al. Ripretinib (DCC-2618) Is a Switch Control Kinase Inhibitor of a Broad Spectrum of Oncogenic and Drug-Resistant KIT and PDGFRA Variants. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 738–751.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabjohns, J.L.A.; Park, Y.-D.; Dehdashti, J.; Sun, W.; Henderson, C.; Zelazny, A.; Metallo, S.J.; Zheng, W.; Williamson, P.R. A High-Throughput Screening Assay for Fungicidal Compounds against Cryptococcus neoformans. SLAS Discov. 2014, 19, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzdar, A.U.; Hortobagyi, G.N. Tamoxifen and toremifene in breast cancer: Comparison of safety and efficacy. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngan, N.T.T.; Thanh Hoang Le, N.; Vi Vi, N.N.; Van, N.T.T.; Mai, N.T.H.; Van Anh, D.; Trieu, P.H.; Lan, N.P.H.; Phu, N.H.; Chau, N.V.V.; et al. An open label randomized controlled trial of tamoxifen combined with amphotericin B and fluconazole for cryptococcal meningitis. eLife 2021, 10, e68929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iba, M.; Kim, C.; Kwon, S.; Szabo, M.; Horan-Portelance, L.; Peer, C.J.; Figg, W.D.; Reed, X.; Ding, J.; Lee, S.-J.; et al. Inhibition of p38α MAPK restores neuronal p38γ MAPK and ameliorates synaptic degeneration in a mouse model of DLB/PD. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eabq6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidhu, G.; Preuss, C.V. Triamcinolone; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Juliana, C.; Fernandes-Alnemri, T.; Wu, J.; Datta, P.; Solorzano, L.; Yu, J.W.; Meng, R.; Quong, A.A.; Latz, E.; Scott, C.P.; et al. Anti-inflammatory compounds parthenolide and Bay 11-7082 are direct inhibitors of the inflammasome. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 9792–9802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Frezza, M.; Schmitt, S.; Kanwar, J.; Dou, Q.P. Bortezomib as the first proteasome inhibitor anticancer drug: Current status and future perspectives. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2012, 11, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Preuss, C.V. Bortezomib; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Diep, A.L.; Hoyer, K.K. Host Response to Coccidioides Infection: Fungal Immunity. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 581101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Kumar, S.; Singh, B.; Jain, P.; Kumari, A.; Pahuja, I.; Chaturvedi, S.; Prasad, D.V.R.; Dwivedi, V.P.; Das, G. The 1,2-ethylenediamine SQ109 protects against tuberculosis by promoting M1 macrophage polarization through the p38 MAPK pathway. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, P.; Bajpai, M.; Dastidar, S.G.; Ray, A. Development of a cell death-based method for the screening of nuclear factor-κB inhibitors. J. Immunol. Methods 2008, 335, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, J.W.; Schoenleber, R.; Jesmok, G.; Best, J.; Moore, S.A.; Collins, T.; Gerritsen, M.E. Novel Inhibitors of Cytokine-induced IκBα Phosphorylation and Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule Expression Show Anti-inflammatory Effects in Vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 21096–21103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watamoto, T.; Egusa, H.; Sawase, T.; Yatani, H. Screening of Pharmacologically Active Small Molecule Compounds Identifies Antifungal Agents Against Candida Biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajetunmobi, O.H.; Wall, G.; Vidal Bonifacio, B.; Martinez Delgado, L.A.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Najvar, L.K.; Wormley, F.L.; Patterson, H.P.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Patterson, T.F.; et al. High-Throughput Screening of the Repurposing Hub Library to Identify Drugs with Novel Inhibitory Activity against Candida albicans and Candida auris Biofilms. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, L.; Piovesan, P.; Ghirardi, O.; Salmona, M.; Forloni, G. ST1859 reduces prion infectivity and increase survival in experimental scrapie. Arch. Virol. 2009, 154, 1539–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, S.; Mortimer, R.B.; Mitchell, M. Sertraline demonstrates fungicidal activity in vitro for Coccidioides immitis. Mycology 2016, 7, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breuer, M.R.; Dasgupta, A.; Vasselli, J.G.; Lin, X.; Shaw, B.D.; Sachs, M.S. The Antidepressant Sertraline Induces the Formation of Supersized Lipid Droplets in the Human Pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhein, J.; Huppler Hullsiek, K.; Tugume, L.; Nuwagira, E.; Mpoza, E.; Evans, E.E.; Kiggundu, R.; Pastick, K.A.; Ssebambulidde, K.; Akampurira, A.; et al. Adjunctive sertraline for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 19, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 8567, Meglumine. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Meglumine (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Retore, Y.I.; Lucini, F.; Simionatto, S.; Rossato, L. Synergistic Antifungal Activity of Pentamidine and Auranofin Against Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris. Mycopathologia 2025, 190, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Patterson, T.F.; Srinivasan, A.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Fothergill, A.W.; Wormley, F.L.; Ramasubramanian, A.K.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Repurposing auranofin as an antifungal: In vitro activity against a variety of medically important fungi. Virulence 2017, 8, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu Almeida, M.; Baeza, L.C.; Silva, L.B.R.; Bernardes-Engemann, A.R.; Almeida-Silva, F.; Coelho, R.A.; de Andrade, I.B.; Corrêa-Junior, D.; Frases, S.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M.; et al. Auranofin is active against Histoplasma capsulatum and reduces the expression of virulence-related genes. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, B.B.; RajaMuthiah, R.; Souza, A.C.; Eatemadpour, S.; Rossoni, R.D.; Santos, D.A.; Junqueira, J.C.; Rice, L.B.; Mylonakis, E. Inhibition of bacterial and fungal pathogens by the orphaned drug auranofin. Future Med. Chem. 2016, 8, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangamani, S.; Maland, M.; Mohammad, H.; Pascuzzi, P.E.; Avramova, L.; Koehler, C.M.; Hazbun, T.R.; Seleem, M.N. Repurposing Approach Identifies Auranofin with Broad Spectrum Antifungal Activity That Targets Mia40-Erv1 Pathway. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Yang, J.; Jin, Y.; Lu, C.; Feng, Z.; Gao, F.; Chen, Y.; Wang, F.; Shang, Z.; Lin, W. In vitro antifungal and antibiofilm activities of auranofin against itraconazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Med. Mycol. 2023, 33, 101381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaakoub, H.; Cindy, S.; Sara, M.; Charlotte, G.; Maxime, F.; Jean-Philippe, B.; Calenda, A. Repurposing of auranofin and honokiol as antifungals against Scedosporium species and the related fungus Lomentospora prolificans. Virulence 2021, 12, 1076–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roder, C.; Thomson, M.J. Auranofin: Repurposing an old drug for a golden new age. Drugs R D 2015, 15, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 4621, Oxethazaine. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Oxethazaine (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Jemel, S.; Guillot, J.; Kallel, K.; Botterel, F.; Dannaoui, E. Galleria mellonella for the Evaluation of Antifungal Efficacy against Medically Important Fungi, a Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marena, G.D.; Thomaz, L.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Taborda, C.P. Galleria mellonella as an Invertebrate Model for Studying Fungal Infections. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Barker, M.; Saeger, S.; Campuzano, A.; Yu, J.-J.; Hung, C.-Y. Galleria mellonella Model of Coccidioidomycosis for Drug Susceptibility Tests and Virulence Factor Identification. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, A.; Binder, U.; Kavanagh, K. Galleria mellonella Larvae as a Model for Investigating Fungal—Host Interactions. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 893494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.F.Q.; Dragotakes, Q.; Kulkarni, M.; Hardwick, J.M.; Casadevall, A. Galleria mellonella immune melanization is fungicidal during infection. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, K.; Sheehan, G. The Use of Galleria mellonella Larvae to Identify Novel Antimicrobial Agents against Fungal Species of Medical Interest. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, E.; Hörtnagl, C.; Lackner, M.; Grässle, D.; Naschberger, V.; Moser, P.; Segal, E.; Semis, M.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Binder, U. Galleria mellonella as a model system to study virulence potential of mucormycetes and evaluation of antifungal treatment. Med. Mycol. 2018, 57, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhoffelen, E.; Michiels, L.; Brock, M.; Lagrou, K.; Reséndiz-Sharpe, A.; Velde, G.V. Powerful and Real-Time Quantification of Antifungal Efficacy against Triazole-Resistant and -Susceptible Aspergillus fumigatus Infections in Galleria mellonella by Longitudinal Bioluminescence Imaging. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0082523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giammarino, A.; Bellucci, N.; Angiolella, L. Galleria mellonella as a Model for the Study of Fungal Pathogens: Advantages and Disadvantages. Pathogens 2024, 13, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemons, K.V.; Capilla, J.; Stevens, D.A. Experimental Animal Models of Coccidioidomycosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1111, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkland, T.N.; Fierer, J. Inbred mouse strains differ in resistance to lethal Coccidioides immitis infection. Infect. Immun. 1983, 40, 912–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shubitz, L.F.; Powell, D.A.; Butkiewicz, C.D.; Lewis, M.L.; Trinh, H.T.; Frelinger, J.A.; Orbach, M.J.; Galgiani, J.N. A Chronic Murine Disease Model of Coccidioidomycosis Using Coccidioides posadasii, Strain 1038. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 223, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.; Chen, X.; Selby, D.; Hung, C.Y.; Yu, J.J.; Cole, G.T. A genetically engineered live attenuated vaccine of Coccidioides posadasii protects BALB/c mice against coccidioidomycosis. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 3196–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graybill, J.R. The role of murine models in the development of antifungal therapy for systemic mycoses. Drug Resistance Updates 2000, 3, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson-Löfmark, R.; Hjorth, S.; Gabrielsson, J. Does In Vitro Potency Predict Clinically Efficacious Concentrations? Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 108, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Gao, W.; Hu, H.; Zhou, S. Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it? Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 3049–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangeneh, T.T.; Lainhart, W.D.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Al-Obaidi, M.M. Coccidioides species antifungal susceptibility testing: Experience from a large healthcare system in the endemic region. Med. Mycol. 2023, 61, myad104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi; Approved Standard, 2nd ed.; CLSI Document M38A2; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, N.; Hoyer, K.K. Coccidioidomycosis Granulomas Informed by Other Diseases: Advancements, Gaps, and Challenges. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, T.; Sampson, N.S. Hit Generation in TB Drug Discovery: From Genome to Granuloma. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1887–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | System Type | Use in CM Research | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro MICs | Cell-based | Primary screen | High-throughput, stage-specific assays | Poor predictor of in vivo efficacy |

| Galleria mellonella | Invertebrate | Initial in vivo model | Cost-effective, dose–response model | Lacks organs associated with ADME * |

| Murine (lung) | Mammalian | Pulmonary model | Mimics primary CM site | Ethical cost, variable strain virulence |

| Murine (disseminated) | Mammalian | CNS/Spleen dissemination | Assesses systemic spread | Requires complex endpoints |

| Murine (CNS) | Mammalian | Treatment of CNS infection | Specifically assesses drug efficacy in CNS infections | Requires expertise in CNS inoculation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saeger, S.; Lozano, S.; Wiederhold, N.; Yu, J.-J.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L.; Hung, C.-Y. Drug Discovery and Repurposing for Coccidioides: A Systematic Review. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120875

Saeger S, Lozano S, Wiederhold N, Yu J-J, Lopez-Ribot JL, Hung C-Y. Drug Discovery and Repurposing for Coccidioides: A Systematic Review. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):875. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120875

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaeger, Sarah, Sofia Lozano, Nathan Wiederhold, Jieh-Juen Yu, Jose L. Lopez-Ribot, and Chiung-Yu Hung. 2025. "Drug Discovery and Repurposing for Coccidioides: A Systematic Review" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120875

APA StyleSaeger, S., Lozano, S., Wiederhold, N., Yu, J.-J., Lopez-Ribot, J. L., & Hung, C.-Y. (2025). Drug Discovery and Repurposing for Coccidioides: A Systematic Review. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120875