Abstract

Species of the basidiomycetous genus Tomentella are widely distributed throughout temperate forests. Numerous studies on the taxonomy and phylogeny of Tomentella have been conducted from the temperate zone in the Northern hemisphere, but few have been from subtropical forests. In this study, four new species, T. casiae, T. guiyangensis, T. olivaceomarginata and T. rotundata from the subtropical mixed forests of Southwestern China, are described and illustrated based on morphological characteristics and phylogenetic analyses of the internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS) and the large subunit of the nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (LSU). Molecular analyses using Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian analysis confirmed the phylogenetic positions of these four new species. Anatomical comparisons among the closely related species in phylogenetic and morphological features are discussed. Four new species could be distinguished by the characteristics of basidiocarps, the color of the hymenophoral surface, the size of the basidia, the shape of the basidiospores and some other features.

1. Introduction

The genus Tomentella Pers. ex Pat. belongs to the family Thelephoraceae Chevall. (Thelephorales, Basidiomycota). Due to Pseudotomentella Svrček being merged in Polyozellus Murrill recently [1], the Thelephoraceae family comprises the genera Amaurodon J. Schröt., Odontia Pers., Polyozellus, Tomentella and Tomentellopsis Hjortstam [2,3]. This family mainly presents thin, effused, flabelliform, pileate or resupinate basidiocarps [4]. Amaurodon has bluish basidiocarps when fresh that become yellow-green when dry. Odontia has a granulose or hydnoid hymenophoral surface and verruculose basidiospores. Tomentellopsis is characterized by a dimitic hyphal system with simple-septate generative hyphae and echinulate basidiospores less than 6 µm in length and with an ellipsoidal frontal face [3]. Polyozellus has resupinate to erected basidiocarps with matt-appearance hymenia [1,5,6,7]. Tomentella produces resupinate basidiocarps that form cottony or spider web-like layers on fallen wood, leaf litter, soil and other substrates [1,2,6,8].

Ectomycorrhizal fungi (EMF) play a significant role in recycling nutrients, digesting plant and insect remnants and maintaining biodiversity in natural ecosystems. EMF produce obviously different types of basidiocarps, which are conspicuous or inconspicuous basidiocarps. The genus Tomentella is a widely distributed ectomycorrhizal lineage [9,10] and can form ectomycorrhiza with different host tree families, e.g., Asteropeiaceae, Dipterocarpaceae, Fabaceae, Gnetaceae, Pinaceae, Proteaceae, Sapotaceae, Sarcolaenaceae and Phyllanthaceae [2,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Since the first finding of an ectomycorrhiza formed by a Tomentella species [11], many studies have confirmed the Tomentella-Thelephora to play an important role in receiving energy and transporting nutrients to their host plants [11,12,13,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Tomentella play a protective and promoting role for growth and development in extreme environments [28]. In addition, the Tomentella-Thelephora lineage reading from the mycorrhizal root tips of Betulaceae, Fagaceae, Pinaceae and Tiliaceae account for 38.2% of the total EMF [29]. The Tomentella-Thelephora lineages are also common in pine forests and nurseries and are intensively studied as they are often used for seedling inoculation in reforestation programs [30]. Although these studies have revealed the presence of a large number of Tomentella OTUs in different type of forests, most sequences are difficult to identify at the species level.

There are many studies on species diversity and taxonomy of Tomentella reported in temperate forests, but few have been conducted in subtropical and tropical regions [1,2,6,30]. Guizhou Province, known as the “Karst Province”, is located on the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau, Southwestern China, and has a subtropical humid monsoon climate [31]. The unique terrain, landforms, climate and vegetation create excellent conditions for the growth of macrofungi [32,33]. In 2023, dozens of Tomentella specimens were collected from two subtropical forests in Guiyang, Guizhou Province. Changpoling National Forest Park is mainly dominated by coniferous trees such as Pinus spp., and a number of broad-leaved trees are scattered in the forests [34]. Qianlingshan Park is the area characterized by karst landform, and dominated by a subtropical evergreen secondary broad-leaved forest, with the domination of Broussonetia popyifera, Cunninghamia lanceolate, Pinus massoniana, Platycladus orientalis, Polygonum barbatum and Quercus acutissima [35].

In this study, four new species were described using morphological and phylogenetic analyses of DNA sequences. The main aim of this study is to update the species diversity of Tomentella in subtropical forests of China.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Collections

Specimens were collected from Changpoling National Forest Park (106°39′10″ E–106°40′10″ E, 26°38′45″ N–26°40′00″ N, Altitude: 1202–1370 m) and Qianlingshan Park (106°41′32″ E, 26°35′53″ N, Altitude: 1100–1396 m), Guizhou Province, Southwestern China. The regions belong to the subtropical humid monsoon climate with the obvious precipitations in summer. The average annual temperature is 13.6 °C, with average annual precipitation of 1200 mm. The specimen information, host trees, ecological habits, collector and date were recorded, and the photos of the basidiocarps and growth environment were taken. Then, the specimens were dried and bagged in time for preservation. The specimens were deposited at the herbarium of the Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IFP).

2.2. Morphological Studies

Macromorphological characteristics, including the color, texture and thickness of basidiocarps, hymenophoral surface and sterile margin, were examined under a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ 1000: Tokyo, Japan) at 4× magnification. The color terms follow Kornerup and Wanscher [36] for the macromorphological description. The microscopic procedure follows Lu [37] with some minor amendments. Microscopic measurements were made from thin sections of basidiocarps mounted in Cotton Blue (abbreviated as CB): 0.1 mg aniline blue dissolved in 60 g pure lactic acid; cyanophilous or acyanophilous reactions were assessed using CB. Amyloid and dextrinoid reactions were tested in Melzer’s reagent (IKI): 1.5 g KI (potassium iodide), 0.5 g I (crystalline iodine), 22 g chloral hydrate, aq. dest. 20 mL, inamyloid = neither amyloid nor dextrinoid reaction. Micromorphological descriptions were studied at magnifications up to 1000× with a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse E600: Tokyo, Japan) with phase contrast illumination, and dimensions were estimated subjectively with an accuracy of 0.2 mm. The following abbreviations are used: L = mean spore length (arithmetical average of all spores), W = mean spore width (arithmetical average of all spores), Q = extreme values of the length/width ratios among the studied specimens and n = the number of spores measured from a given number of specimens. Drawings were made with the aid of a drawing tube. The surface morphology for the basidiospores was observed with a QUANTA 250 scanning electron microscope (ESEM, QUANTA 250, FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at an accelerating voltage of 25 kV. The working distance was 12.2 mm. A thin layer of gold was coated onto the samples to avoid charging.

2.3. DNA Extraction, Amplification and Sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the dried specimens with a Thermo Scientific Phire Plant Direct PCR Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). PCR reactions were performed in 30 µL of reaction mixtures containing 15 µL of 2× Phire® Plant PCR buffer, 0.6 µL of Phire® Hot Start II DNA Polymerase, 1.5 µL of each PCR primer (10 mM), 10.5 µL of doubly deionized H2O (ddH2O) and 0.9 µL of template DNA. For initial species confirmation, the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region was sequenced for all specimens. The BLAST tool (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, accessed on 29 April 2024) was used to compare the resulting sequences with those in GenBank (Table 1). After confirmation of Tomentella species, additional gene region coding for the large subunit of nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (LSU) was sequenced. The ITS region was amplified with the primers ITS5 (5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) [38,39]. The LSU gene was amplified with the primers LROR (5′-ACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC-3′) and LR7 (5′-TACTACCACCAAGATCT-3′) [40,41]. The PCR thermal cycling program conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 39 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, × °C (the annealing temperatures for ITS4/ITS5 and LROR/LR7 were 54 °C and 48 °C, respectively) for 30 s [40,42], at 72 °C for 20 s and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. All amplified PCR products were estimated visually with 1.4% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide and sequenced at the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) with the same primers.

Table 1.

Species, vouchers, GenBank/UNITE accessions and localities of specimens used in this study.

2.4. Phylogenetic Analyses

The new sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank. These new sequences, together with the reference sequences of all samples used in the present study, are listed in Table 1. The sequences were edited and condensed with SeqMan v.7.1.0. The sequences generated in this study were supplemented with additional sequences obtained from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank, accessed on 29 April 2024) and UNITE (https://unite.ut.ee/index.php, accessed on 29 April 2024) based on blast searches and recent publications of the genus Tomentella. The sequences were aligned with MAFFT v.7, after which the alignments were manually corrected using MEGA v. 7.0 [43,44]. Phylogenetic analyses including Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods were conducted for the single gene sequence datasets of the ITS and LSU, and the combined dataset of two gene regions. ML analyses were conducted using RAxML-HPC BlackBox 8.2.10 on the CIPRES Science Gateway portal (https://www.phylo.org/portal2, accessed on 29 April 2024) [45], employing a GTRGAMMA substitution model with 1000 bootstrap replicates [46]. BI analyses were conducted using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm in MrBayes v.3.0 [47]. Two Markov chains were run from a random starting tree for 1,000,000 generations, resulting in a total of 10,000 trees. The first 25% of trees sampled were discarded as burn-in, and the remaining trees were used to calculate the posterior probabilities. Branches with significant Bayesian Posterior Probabilities (BPP > 0.9) were estimated in the remaining 7500 trees. Phylogenetic trees were viewed with FigTree v. 1.4 and processed by Adobe Illustrator CS5.

The ITS sequences of four new species ran UNITE SH matching analyses in PlutoF (https://plutof.ut.ee/, accessed on 29 April 2024) [48,49,50], and the corresponding UNITE SH (species hypothesis) numbers were assigned.

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analyses

The combined two-gene sequences dataset (ITS and LSU) was analyzed to determine the phylogenetic positions of the new samples obtained in this study. A total of 2217 characters, including gaps (811 for ITS and 1406 for LSU), were included in the dataset used in the phylogenetic analyses. Of these characters, 928 were constant, 470 were parsimony-uninformative variable and 819 were parsimony-informative. The multiple sequence alignment included the following: nine sequences of the four new species, 211 sequences of Tomentella species [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63] and one outgroup sequence of Odontia ferruginea from Estonia [38,64].

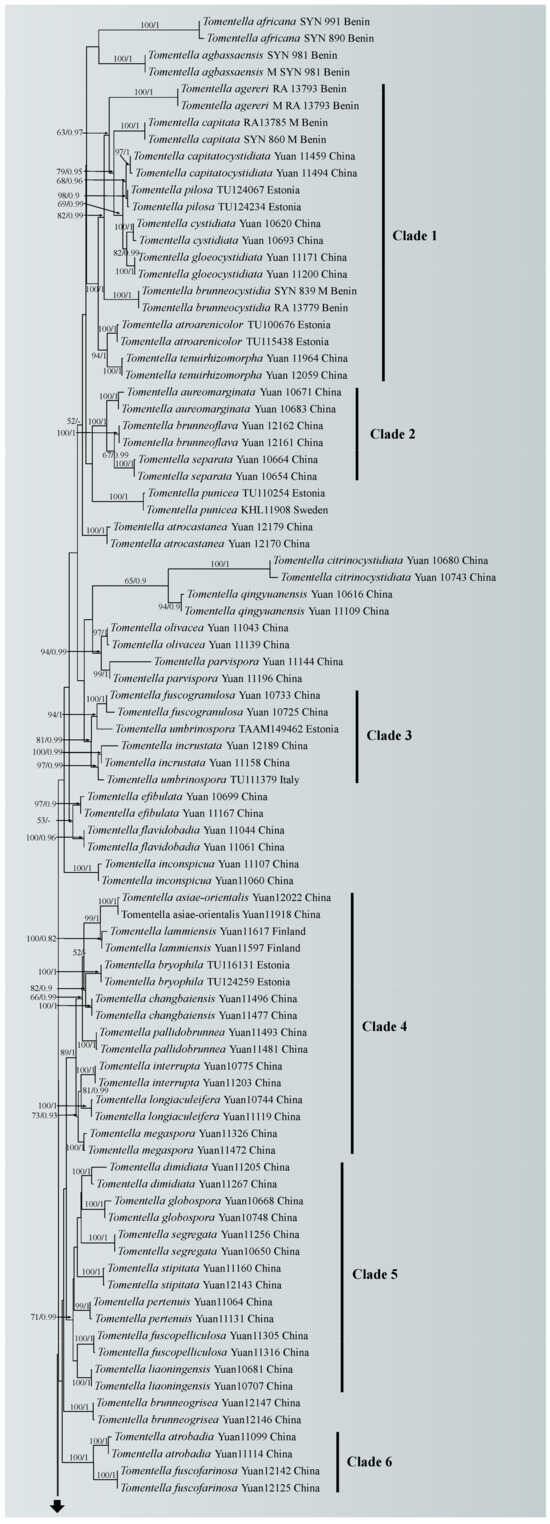

A similar topology was obtained using ML and Bayesian analyses with one sample of Odontia ferruginea as the outgroup [65], and only the ML tree is shown in Figure 1 with the ML bootstrap values and Bayesian posterior probabilities. In the phylogenetic tree, 18 clades with moderate to strong support were marked, of which six clades (clade 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 16) were consistent with the previous ITS + LSU phylogenetic analyses [65]. Five of the six clades were more strongly supported (100% ML/1.00 BPP for clade 2, 89% ML/1 BPP for clade 4, 100% ML/1.00 BPP for clade 6, 90% ML/0.98 BPP for clade 8 and 84% ML for clade10, respectively), and clade 16 lacked significant support. The phylogenetic tree shows that the nine specimens formed four single clades with strong support (100% ML/1.00 BPP for T. casiae, T. guiyangensis, T. olivaceomarginata and T. rotundata) and clustered in the clade that was composed of most species of Tomentella used in this study.

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood tree illustrating the phylogeny of Tomentella casiae, T. guiyangensis, T. olivaceomarginata and T. rotundata related taxa based on ITS + LSU nuclear rDNA sequences dataset. Branches are labeled with Maximum likelihood bootstrap equal to or higher than 50% and Bayesian posterior probabilities equal to or higher than 0.9. Vouchers and regions are indicated after the species names. New species in bold (black).

3.2. Taxonomy

Fungal Names: FN 571968

Diagnosis: Hymenophoral surface grayish to gray; sterile margin grayish. Hyphae system monomitic, generative hyphae clamped. Rhizomorphs present, single hypha clamped and rarely simple-septate. Basidiospores subglobose to lobed, echinuli up to 1 µm long.

Type: CHINA. Guizhou Province, Guiyang City, Qianlingshan Park, on fallen angiosperm branch, 21 August 2023, Yuan 18263 (holotype IFP 019963), UNITE SH: SH0917753.10FU.

Etymology: Casiae (combinated by CAS and IAE), commemorating the 70th anniversary of the Institute of Applied Ecology (IAE), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

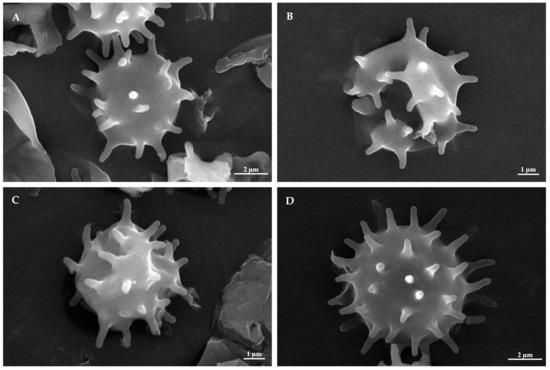

Basidiocarps: annual, resupinate, separable from the substrate, mucedinoid, without odor or taste when fresh, 0.5–1 mm thick, continuous. Hymenophoral surface granulose, grayish to gray (7D1–7E1) and concolorous with the subiculum; sterile margin often indeterminate, byssoid, lighter than hymenophore, light gray.

Rhizomorphs: present in subiculum and margins, 20–55 µm diam; rhizomorphic surface more or less smooth; hyphae in rhizomorph monomitic, undifferentiated, of type B (according to Agerer, 1987–2008), compactly arranged and uniform; single hypha clamped and rarely simple-septate, thick-walled, unbranched, 1.5–2 µm diam, grayish brown in KOH, acyanophilous, inamyloid.

Subicular hyphae: monomitic; generative hyphae clamped, thick-walled, 3–6 µm diam, without encrustation, brown in KOH and distilled water, cyanophilous, inamyloid. Subhymenial hyphae clamped, slightly thin-walled, 2.5–5 µm diam, without encrustation; hyphal cells more or less uniform, brown in KOH and in distilled water, cyanophilous, inamyloid.

Cystidia: absent.

Basidia: 30–55 µm long, 4–6.5 µm diam at apex and 3–4.5 µm at base, with a clamp connection at base, utriform, not stalked, sinuous, pale brown in KOH and distilled water, 4-sterigmata; sterigmata 2–4 µm long and 1–1.5 µm diam at base.

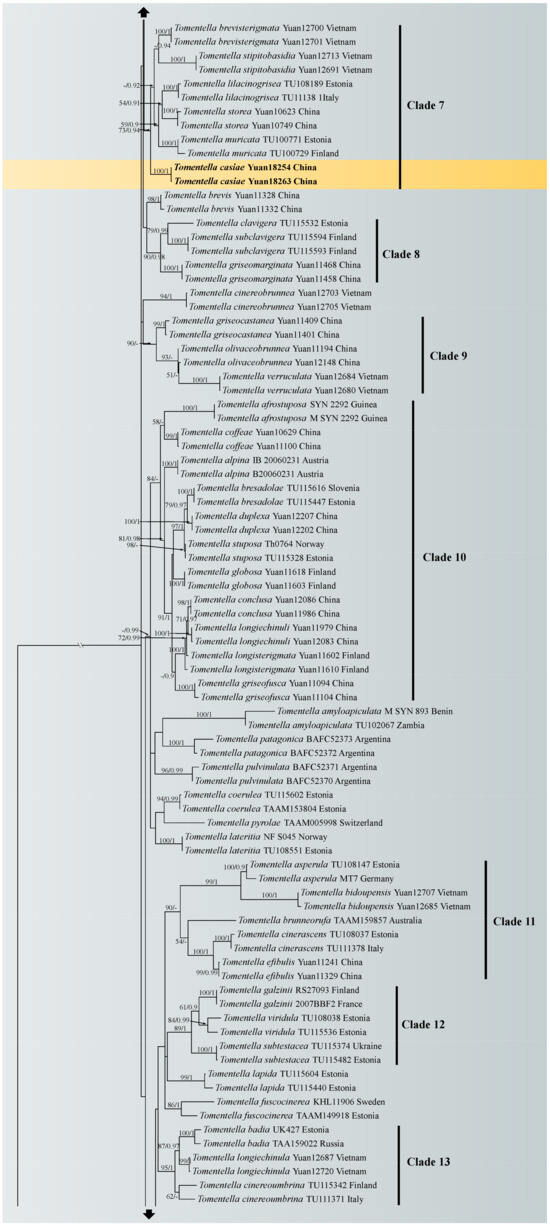

Basidiospores: (7.4–)7.8–10.1(–10.5) × (6.3–)6.7–8.8(–9.1) µm, L = 8.85 µm, W = 7.86 µm, Q = 1.01–1.30 (n = 60/2), subglobose to bi-, tri- or quadra-lobed in frontal and lateral face, echinulate, pale brown in KOH and distilled water, acyanophilous, inamyloid; echinuli usually grouped in 2 or more, up to 1 µm long.

Additional specimen (paratype) examined: CHINA. Guizhou Province, Guiyang City, Qianlingshan Park, on fallen angiosperm branch 21 August 2023, Yuan 18254 (IFP 019960).

Notes: In the phylogenetic tree (Figure 1), Tomentella casiae, T. brevisterigmata, T. muricata, T. storea and T. lilacinogrisea clustered together with moderate support (73% in ML). Among these species, T. casiae possesses large size basidiospores, bigger than those of the other species. T. casiae also possesses rhizomorphs that are the same as those of T. brevisterigmata, but T. casiae differs by its mucedinoid basidiocarps [65]. T. casiae presents two obvious different characteristics comparing with T. muricata: the presence of rhizomorphs in the subiculum and margins and the absence of elongated cystidia [66]. T. casiae is differentiated from T. storea by its mucedinoid basidiocarps and larger basidia [67]. T. casiae can be distinguished from T. lilacinogrisea by separable basidiocarps [68].

Figure 2.

SEM of basidiospores of Tomentella species. (A) T. casiae (holotype Yuan 18263); (B) T. guiyangensis (holotype Yuan 18281); (C) T. olivaceomarginata (holotype Yuan 18268); (D) T. rotundata (holotype Yuan 18269).

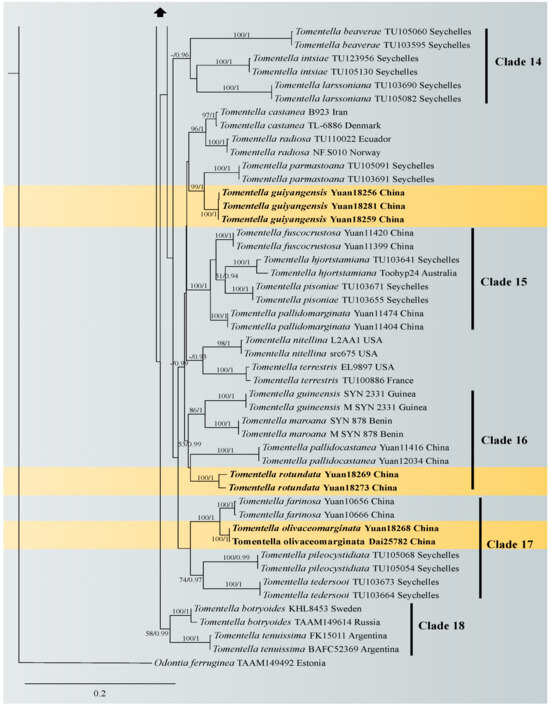

Figure 3.

A basidiocarp of Tomentella casiae (Holotype Yuan 18263). Photos by Hai-Sheng Yuan.

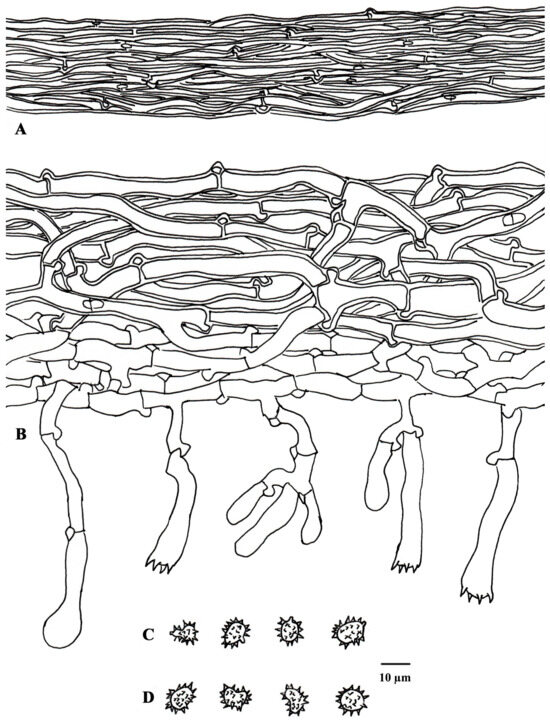

Figure 4.

Microscopic structures of Tomentella casiae (drawn from holotype Yuan 18263). (A) Hyphae from a rhizomorph. (B) A section through a basidiocarp. (C) Basidiospores in lateral view. (D) Basidiospores in frontal view.

Fungal Names: FN 571969

Diagnosis: Hymenophoral surface dark brown to chestnut; sterile margin dark brown. Hyphae in rhizomorphs clamped and rarely simple-septate. Basidia short sterigmata. Basidiospores echinuli up to 2 µm long.

Type: CHINA. Guizhou Province, Guiyang City, Qianlingshan Park, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 21 August 2023, Yuan 18281 (holotype IFP 019967), UNITE SH: SH0920617.10FU.

Etymology: Guiyangensis (Lat.), named after the collection site of the type specimen, Guiyang City.

Basidiocarps: annual, resupinate, separable from the substrate, mucedinoid, without odor or taste when fresh, 0.6–1.0 mm thick, continuous. Hymenophoral surface smooth, dark brown to chestnut (6E7–6F7) and turning darker than the subiculum when dry; sterile margin often indeterminate, farinaceous, concolorous with hymenophore.

Rhizomorphs: present in subiculum and margins, 10–30 µm diam; rhizomorphic surface more or less smooth; hyphae in rhizomorph: monomitic, undifferentiated, of type B (according to Agerer, 1987–2008), compactly arranged and uniform; single hypha: clamped and rarely simple-septate, thick walled, unbranched, 2–5 µm diam, pale brown in KOH, cyanophilous, inamyloid.

Subicular hyphae: monomitic; generative hyphae: clamped and rarely simple-septate, thick-walled, 3–6 µm diam, with encrustation and grayish brown in KOH and distilled water, acyanophilous, inamyloid. Subhymenial hyphae clamped and rarely simple-septate, thick-walled, 4–6 µm diam, without encrustation; hyphal cells more or less uniform, pale to dark brown in 2.5% KOH and in distilled water, cyanophilous, inamyloid.

Cystidia: absent.

Basidia: 35–55 µm long, 5–9 µm diam at apex and 4–5 µm at base, with a clamp connection at base, clavate, not stalked, sinuous, rarely transverse septa, pale brown in KOH and distilled water, 4-sterigmata; sterigmata 2–3.5 µm long and 1–1.5 µm diam at base.

Basidiospores: (6.3–)6.6–8.5(–8.8) × (4.5–)5.0–7.0(–7.5) µm, L = 7.3 µm, W = 6.1 µm, Q = 1.01–1.67 (n = 60/2), subglobose to bi-, tri- or quadra-lobed in frontal and lateral face, echinulate to aculeate, pale brown in KOH and distilled water, acyanophilous, inamyloid; echinuli usually grouped in 2 or more, up to 2 µm long.

Additional specimens (paratype) examined: CHINA. Guizhou Province, Guiyang City, Qianlingshan Park, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 21 August 2023, Yuan 18256 (IFP 019961); on fallen branch of Quercus, 21 August 2023, Yuan18259 (IFP 019962).

Notes: In the phylogenetic tree (Figure 1), Tomentella guiyangensis and T. parmastoana clustered together with significant support (100% in ML and 1.00 BPP). They exhibit some similar characteristics: mucedinoid basidiocarps, more or less similar color of the hymenophoral surface (brown, grayish brown or dark brown), monomitic rhizomorphs and size of basidiospores [58]. However, T. guiyangensis differs from T. parmastoana by separable basidiocarps and larger basidia (35–55 µm).

Figure 5.

A basidiocarp of Tomentella guiyangensis (Holotype Yuan18281). Photos by Ya-Quan Zhu.

Fungal Names: FN 571971

Diagnosis: Hymenophoral surface pale brown to brown; sterile margin olivaceous. Hyphae in rhizomorphs simple-septate; generative hyphae clamped. Basidiospores subglobose to bi-, tri- or quadra-lobed in frontal and lateral face.

Type: CHINA. Guizhou Province, Guiyang City, Qianlingshan Park, on fallen angiosperm branch, 21 August 2023, Yuan 18268 (holotype IFP 019964), UNITE SH: SH0921288.10FU.

Etymology: Olivaceomarginata (Lat.), referring to the brown hymenophoral surface and olive sterile margin.

Basidiocarps: annual, resupinate, separable from the substrate, arachnoid or mucedinoid, without odor or taste when fresh, 1.5–3 mm thick, continuous. Hymenophoral surface smooth, pale brown to brown (5D4–6E7) and turning darker than subiculum when dry; sterile margin often indeterminate, farinaceous, paler than hymenophore, olivaceous.

Rhizomorphs: present in subiculum and margins, 30–45 µm diam; rhizomorphic surface: more or less smooth; hyphae in rhizomorph: monomitic, undifferentiated, of type B (according to Agerer, 1987–2008), compactly arranged and uniform; single hypha: simple-septate, thick walled, unbranched, 3–5 µm diam, brown in KOH, acyanophilous, inamyloid.

Subicular hyphae: monomitic; generative hyphae clamped, slightly thick walled, 4–8 µm diam, with encrustation, pale to dark brown in KOH and distilled water, acyanophilous, inamyloid. Subhymenial hyphae clamped, thin-walled, 4–6 µm diam, without encrustation; hyphal cells more or less uniform, pale to dark brown in 2.5% KOH and in distilled water, acyanophilous, inamyloid.

Cystidia: absent.

Basidia: 15–35 µm long, 6–8 µm diam at apex and 3–5 µm at base, with simple septa at base, clavate, not stalked, without transverse septa, pale brown in KOH and distilled water, 4-sterigmata; sterigmata: 3–4 µm long and 1.5–2 µm diam at base.

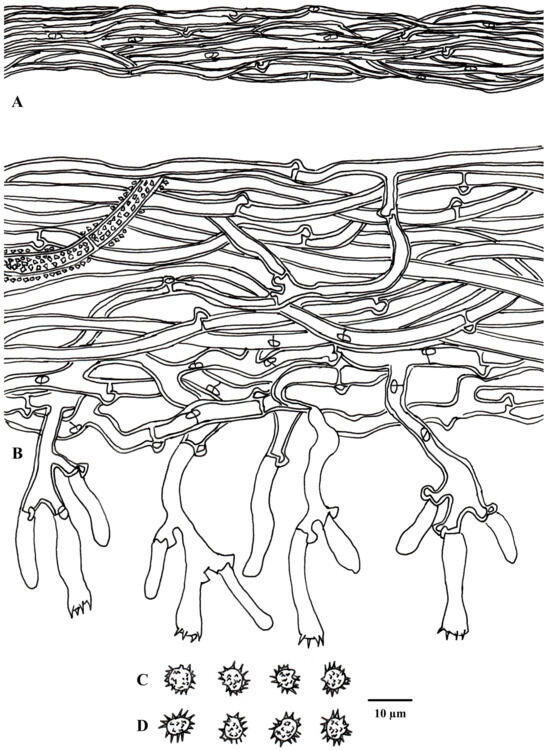

Figure 6.

Microscopic structures of Tomentella guiyangensis (drawn from holotype Yuan 18281). (A) Hyphae from a rhizomorph. (B) A section through a basidiocarp. (C) Basidiospores in lateral view. (D) Basidiospores in frontal view.

Basidiospores: (5.1–)6–7.7 (–8.1) × (4.5–)4.8–7(–7.5) µm, L = 6.75 µm, W = 5.74 µm, Q = 1.01–1.60 (n = 60/2), subglobose to bi-, tri- or quadra-lobed in frontal and lateral face, echinulate to aculeate, grayish brown in KOH and distilled water, cyanophilous, inamyloid; echinuli or aculei usually grouped in 2 or more, up to 1 µm long.

Additional specimen (paratype) examined: CHINA. Guizhou Province, Guiyang City, Qianlingshan Park, on rotten wood of Pinus massoniana, 21 August 2023, Dai 25782.

Notes: Tomentella olivaceomarginata and T. farinosa showed a close relationship with significant support (100% in ML and 0.99 BPP) in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 1), and continuous basidiocarps separable from the substrate, indeterminate sterile margin, clamped hyphae, absence of cystidia, the pale brown to brown hymenophoral surface and the basidiospores of approximately the same shape and size are their common characteristics [67]. However, T. olivaceomarginata is differentiated from T. farinosa by mucedinoid basidiocarps and the presence of rhizomorphs (3–5 µm in diam) [67]. The subclade of the tree also contains T. pileocystidiata, and larger basidiospores and the presence of cystidia can be obviously distinguished from those of T. olivaceomarginata [58].

Figure 7.

A basidiocarp of Tomentella olivaceomarginata (Holotype Yuan 18268). Photos by Hai-Sheng Yuan.

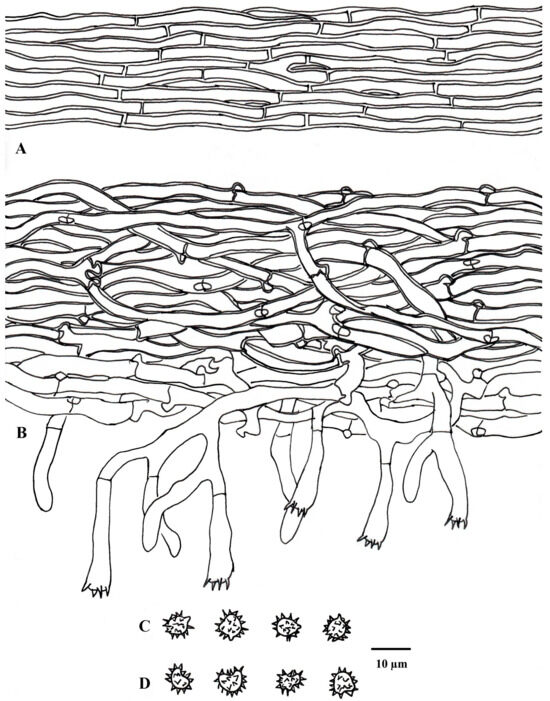

Figure 8.

Microscopic structures of Tomentella olivaceomarginata (drawn from holotype Yuan 18268). (A) Hyphae from a rhizomorph. (B) A section through a basidiocarp. (C) Basidiospores in lateral view. (D) Basidiospores in frontal view.

Fungal Names: FN 571972

Diagnosis: Hymenophoral surface gray to gray brown; sterile margin gray. Rhizomorphs absent; basidia with simple septa at base. Basidiospores echinuli or aculei up to 4 µm long.

Type: CHINA. Guizhou Province, Guiyang City, Qianlingshan Park, on fallen angiosperm branch, 21 August 2023, Yuan 18269 (holotype IFP 019965), UNITE SH: SH0918315.10FU.

Etymology: Rotundata (Lat.), referring to the round basidiospores.

Basidiocarps: annual, resupinate, adherent to the substrate, mucedinoid, without odor or taste when fresh, 0.5–0.8 mm thick, continuous. Hymenophoral surface smooth, gray to gray brown (8D3–8E4) and concolorous with the subiculum; sterile margin: often indeterminate, byssoid, concolorous with hymenophore.

Rhizomorphs: absent.

Subicular hyphae: monomitic; generative hyphae clamped and rarely simple-septate, thick-walled, 2–6 µm diam, without encrustation, grayish brown in KOH and distilled water, cyanophilous, inamyloid. Subhymenial hyphae clamped, slightly thick-walled, 4–7 µm diam, without encrustation; hyphal cells short (1–2 µm), brown in KOH and in distilled water, cyanophilous, inamyloid. Cystidia: absent.

Basidia: 15–45 µm long and 5–8 µm diam at apex, 3–4 µm at base, with simple septa at base, utriform, not stalked, sinuous, rarely with transverse septa, pale brown in KOH and distilled water, 4-sterigmata; sterigmata: 9–10 µm long and 2–3 µm diam at base.

Basidiospores: (9.8–)10.2–13.1(–13.5) × (9.2–)9.5–12.1(–12.4) µm, L = 11.8 µm, W = 10.7 µm, Q = 1.00–1.30 (n = 60/2), subglobose to globose in frontal and lateral face, echinulate to aculeate, pale brown in KOH and distilled water, cyanophilous, inamyloid; echinuli or aculei usually isolated, up to 4 µm long.

Additional specimen (paratype) examined: CHINA. Guizhou Province, Guiyang City, Qianlingshan Park, on root of living angiosperm tree, 21 August 2023, Yuan 18273 (IFP 019966).

Notes: Tomentella rotundata and T. pallidocastanea formed a clade with moderate support (67% in ML) in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 1) and then clustered with T. guineensis and T. maroana (54% in ML and 0.99 BPP) [69]. Their common features are basidiocarps adherent to the substrate, clamped generative hyphae, utriform basidia and the absence of cystidia. However, T. rotundata is distinguished by larger basidiospores (10–13 µm) with longer echinuli (4 μm).

Figure 9.

A basidiocarp of Tomentella rotundata (Holotype Yuan 18269). Photos by Hai-Sheng Yuan.

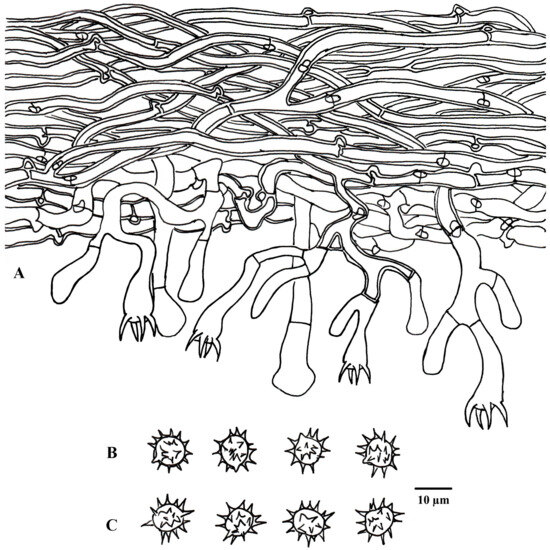

Figure 10.

Microscopic structures of Tomentella rotundata (drawn from holotype Yuan 18269). (A) A section through a basidiocarp. (B) Basidiospores in lateral view. (C) Basidiospores in frontal view.

4. Discussion

In this study, four new Tomentella species distributed in Guizhou of Southwestern China were identified by morphological characteristics and phylogenetic analyses combining ITS and LSU sequences. Phylogenetic analyses and morphological features allowed distinguishing the four new species from other known species.

In the phylogenetic tree, 18 clades with moderate to strong support were obtained. Some of these clades were consistent with the previous ITS + LSU phylogenetic analyses [65]. The new species in the clade with high support may share some consistent characteristics. For instance, Tomentella casiae fell in clade 7, and the basidiocarps of the species in this clade have an indeterminate sterile margin; T. rotundata clustered in clade 16, and species in this clade have clamped and rarely simple-septate subicular hyphae; T. olivaceomarginata clustered in clade 17, and species in this clade have separable basidiocarps with an arachnoid surface.

The forests investigated in this study are dominated by coniferous trees Pinus massoniana and P. armandii, and broad-leaved trees mainly included Bothrocaryum controversum, Celtis sinensis, Ligustrum lucidum and Robinia pseudoacacia. The specimens of these four new species were collected from rotten angiosperm wood debris, and their symbiotic plant hosts could not yet be determined. However, the development of resupinate basidiocarps represents an adaptive advantage for species of Tomentella growing in primary successional habitats.

In recent years, high-throughput sequencing technology has made it possible to explore unculturable taxa from environmental samples, for example soil or plant root tips, in different regions of the world. However, the BLAST of Tomentella species by the ITS sequences in the international gene database (NCBI and UNITE) normally results in a large number of unidentified environmental samples as best matches. It may result from insufficient taxonomic study of this group of fungi. Many studies by high-throughput sequencing have revealed that there are a large number of Tomentella spp. in China [62,70,71,72,73,74], and the ectomycorrhizal samples of Tomentella have been collected and reported in a previous study from Guizhou Province [75]. Therefore, the species diversity of Tomentella in the Karst subtropical forests of Guizhou needs further exploration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-S.Y. and Y.-L.W.; methodology, Y.-Q.Z.; software, Y.-Q.Z.; validation and formal analysis, Y.-Q.Z. and X.-L.L.; investigation, D.-X.Z., Y.-L.W. and H.-S.Y., resources, H.-S.Y.; data curation, Y.-Q.Z. and X.-L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.-S.Y. and Y.-Q.Z.; visualization, H.-S.Y. and Y.-Q.Z.; supervision, project administration and funding acquisition, H.-S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project nos. U2102220 and 31970017).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The sequences from the present study were submitted to the NCBI website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 29 April 2024), and the accession numbers were listed in Table 1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Svantesson, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Wurzbacher, C.; Saar, I.; Larsson, K.H.; Larsson, E. Polyozellus vs. Pseudotomentella: Generic delimitation with a multi-gene dataset. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2021, 8, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, M.J. A Contribution to the Taxonomy of the Genus Tomentella; Mycologia Memoir 4.; New York Botanical Garden in Collaboration with The Mycological Society of America: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 1–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kõljalg, U. Tomentella (Basidiomycota) and Related Genera in Temperate Eurasia; Synopsis Fungorum 9.; Tõravere Trükikoda and Greif: Tartu, Estonia, 1996; pp. 1–213. [Google Scholar]

- Agerer, R. Fungal relationships and structural identity of their ectomycorrhizae. Mycol. Prog. 2006, 5, 7–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svrček, M. Příspěvek k taxonomii resupinátních rodů celidi Thelephoraceae s. s. Ceská Mykol. 1958, 12, 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, M.J. Tomentelloid fungi of North America; State University College of Forestry at Syracuse University Technical Publication: Syracuse, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 1–157. [Google Scholar]

- Stalpers, J.A. The Aphyllophoraceous Fungi I: Key to the species of the Thelephorales. Stud. Mycol. 1993, 35, 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, M.J. The genus Pseudotomentella. Nova Hedwig. 1971, 22, 599–619. [Google Scholar]

- Tedersoo, L.; May, T.W.; Smith, M.E. Ectomycorrhizal lifestyle in fungi: Global diversity, distribution, and evolution of phylogenetic lineages. Mycorrhiza 2010, 20, 217–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedersoo, L.; Smith, M.E. Lineages of ectomycorrhizal fungi revisited: Foraging strategies and novel lineages revealed by sequences from belowground. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2013, 27, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, R.M.; Pruden, M. The ectomycorrhizal status of urban spruce. Mycologia 1989, 81, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erland, S.; Taylor, A.F.S. Resupinate ectomycorrhizal fungal genera. In Ectomycorrhizal Fungi: Key Genera in Profile; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 347–363. [Google Scholar]

- Jakucs, E.; Erős-Honti, Z. Morphological-anatomical characterization and identification of Tomentella ectomycorrhizas. Mycorrhiza 2008, 18, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, F. Ektomykorrhizen an Fagus sylvatica: Charakterisierung und Identifizierung, ökologische Kennzeichnung und unsterile Kultivierung. Lib. Bot. 1991, 2, 1–228. [Google Scholar]

- Danielson, R.M.; Zak, J.C.; Parkinson, D. Mycorrhizal inoculum in a peat deposit formed under a white spruce stand in Alberta. Can. J. Bot. 1984, 62, 2557–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakucs, E.; Kovács, G.M.; Agerer, R.; Romsics, C.; Erős, Z. Morphological-anatomical characterization and molecular identification of Tomentella stuposa ectomycorrhizae and related anatomotypes. Mycorrhiza 2005, 15, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakucs, E.; Kovács, G.M.; Szedlay, G.; Erős-Honti, Z. Morphological and molecular diversity and abundance of tomentelloid ectomycorrhizae in broad-leaved forests of the Hungarian Plain. Mycorrhiza 2005, 15, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köljalg, U.; Dahlberg, A.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Larsson, E.; Hallenberg, N.; Stenlid, J.; Larsson, K.H.; Fransson, P.M.; Kårén, O.; Jonsson, L. Diversity and abundance of resupinate thelephoroid fungi as ectomycorrhizal symbionts in Swedish boreal forests. Mol. Ecol. 2000, 9, 1985–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.L.; Bruns, T.D. Independent, specialized invasions of ectomycorrhizal mutualism by two nonphotosynthetic orchids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 4510–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedersoo, L.; Suvi, T.; Beaver, K.; Kõljalg, U. Ectomycorrhizal fungi of the Seychelles: Diversity patterns and host shifts from the native Vateriopsis seychellarum (Dipterocarpaceae) and Intsia bijuga (Caesalpiniaceae) to the introduced Eucalyptus robusta (Myrtaceae), but not Pinus caribea (Pinaceae). New Phytol. 2007, 175, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidartondo, M.I.; Burghardt, B.; Gebauer, G.; Bruns, T.D.; Read, D.J. Changing partners in the dark: Isotopic and molecular evidence of ectomycorrhizal liaisons between forest orchids and trees. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2004, 271, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selosse, M.A.; Richard, F.; He, X.; Simard, S.W. Mycorrhizal networks: Des liaisons dangereuses? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006, 21, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedersoo, L.; Suvi, T.; Beaver, K.; Saar, I. Ectomycorrhizas of Coltricia and Coltriciella (Hymenochaetales, Basidiomycota) on Caesalpiniaceae, Dipterocarpaceae and Myrtaceae in Seychelles. Mycol. Prog. 2007, 6, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Köljalg, U.; Hallenberg, N.; Larsson, K.H. Fine scale distribution of ectomycorrhizal fungi and roots across substrate layers including coarse woody debris in a mixed forest. New Phytol. 2003, 159, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, D.J.; Perez-Moreno, J. Mycorrhizas and nutrient cycling in ecosystems—A journey towards relevance? New Phytol. 2003, 157, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakucs, E.; Erős-Honti, Z.; Seress, D.; Kovács, G.M. Enhancing our understanding of anatomical diversity in Tomentella ectomycorrhizas: Characterization of six new morphotypes. Mycorrhiza 2015, 25, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouhra, E.; Pastor, N.; Becerra, A.; Areitio, E.S.; Geml, J. Greenhouse seedlings of Alnus showed low host intrageneric specificity and a strong preference for some Tomentella ectomycorrhizal associates. Microb. Ecol. 2015, 69, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Wu, S.; Pan, H.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L. Cortinarius and Tomentella fungi become dominant taxa in taiga soil after fire disturbance. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, N.N.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, L.; Wubet, T.; Bruelheide, H.; Both, S.; Buscot, F.; Ding, Q.; et al. Community assembly of ectomycorrhizal fungi along a subtropical secondary forest succession. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colpaert, J.V. Thelephora. In Ectomycorrhizal Fungi. Key Genera in Profile; Cairney, J.W.G., Chambers, S.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 245–325. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.P.; Xiao, F.; Wu, H.Z.; Mo, S.G.; Zhu, S.Q.; Yu, L.F.; Xiong, K.N.; Lan, A.J. Combating the Fragile Karst Environment in Guizhou, China. Ambio 2006, 35, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Castlebury, L.A.; Miller, A.N.; Huhndorf, S.M.; Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Rogers, J.D.; Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B.; Sung, G. An overview of the systematics of the Sordariomycetes based on a four-gene phylogeny. Mycologia 2006, 98, 1076–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorbushina, A. Microcolonial fungi: Survival potential of terrestrial vegetative structures. Astrobiology 2003, 3, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Long, J.; Li, P.; Chen, X.M.; Jiang, Y.C.; Wang, Y.R. Spatial structure of secondary forest in Changpoling Forest Farm of Guiyang. J. Zhejiang Forest. Sci. Technol. 2018, 38, 37–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Lu, Z.Y.; Li, D.; Wang, Q.; Su, H.J. Population dynamics of semi-free-ranging rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) in Qianlingshan Park, Guizhou, China. Acta Theriol. Sin. 2019, 39, 630–638. [Google Scholar]

- Kornerup, A.; Wanscher, J. Methuen Handbook of Colour Fletcher, 3rd ed.; Eyre Methuen: Norwich, UK, 1981; pp. 1–252. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Mu, Y.H.; Yuan, H.S. Two new species of Tomentella (Thelephorales, Basidiomycota) from Lesser Xingan Mts., northeastern China. Phytotaxa 2018, 369, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Harend, H.; Buegger, F.; Pritsch, K.; Saar, I.; Kõljalg, U. Stable isotope analysis, field observations and synthesis experiments suggest that Odontia is a non-mycorrhizal sister genus of Tomentella and Thelephora. Fungal Ecol. 2014, 11, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Seven, J.; Polle, A. Host preferences and differential contributions of deciduous tree species shape mycorrhizal species richness in a mixed Central European forest. Mycorrhiza 2011, 21, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncalvo, J.M.; Rehner, S.A.; Vilgalys, R. Systematics of Lyophyllum section Difformia based on evidence from culture studies and ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycologia 1993, 85, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.L.; McCormick, M.K. Internal transcribed spacer primers and sequences for improved characterization of basidiomycetous orchid mycorrhizas. New Phytol. 2008, 177, 1020–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Toh, H. Parallelization of the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1899–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Pfeiffer, W.; Schwartz, T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. In Proceedings of the 2010 Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), New Orleans, LA, USA, 14 November 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 1572–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Larsson, K.-H.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Jeppesen, T.S.; Schigel, D.; Kennedy, P.; Picard, K.; Glöckner, F.O.; Tedersoo, L.; et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: Handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D259–D264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kõljalg, U.; Nilsson, H.; Abarenkov, K.; Tedersoo, L.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Bahram, M.; Bates, S.T.; Bruns, T.D.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Callaghan, T.M.; et al. Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 5271–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõljalg, U.; Nilsson, H.R.; Schigel, D.; Tedersoo, L.; Larsson, K.-H.; May, T.W.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Jeppesen, T.S.; Frøslev, T.G.; Lindahl, B.D.; et al. The taxon hypothesis paradigm—On the unambiguous detection and communication of taxa. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, K.H.; Larsson, E.; Kõljalg, U. High phylogenetic diversity among corticioid homobasidiomycetes. Mycol. Res. 2004, 108, 983–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Suvi, T.; Larsson, E.; Kõljalg, U. Diversity and community structure of ectomycorrhizal fungi in a wooded meadow. Mycol. Res. 2006, 110, 734–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.E.; Douhan, G.W.; Rizzo, D.M. Ectomycorrhizal community structure in a xeric Quercus woodland based on rDNA sequence analysis of sporocarps and pooled roots. New Phytol. 2007, 174, 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yorou, N.S.; Kõljalg, U.; Sinsin, B.; Agerer, R. Studies in African thelephoroid fungi: 1. Tomentella capitata and Tomentella brunneocystidia, two new species from Benin (West Africa) with capitate cystidia. Mycol. Prog. 2007, 6, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yorou, N.S.; Guelly, A.K.; Agerer, R. Anatomical and ITS rDNA-based phylogenetic identification of two new West African resupinate thelephoroid species. Mycoscience 2011, 52, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Smith, M.E.; Rizzo, D.M.; Rejmánek, M.; Bledsoe, C.S. Contrasting ectomycorrhizal fungal communities on the roots of co-occurring oaks (Quercus spp.) in a California woodland. New Phytol. 2008, 178, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorou, N.S.; Agerer, R. Tomentella africana, a new species from Benin (West Africa) identified by morphological and molecular data. Mycologia 2008, 100, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvi, T.; Tedersoo, L.; Abarenkov, K.; Beaver, K.; Gerlach, J.; Kõljalg, U. Mycorrhizal symbionts of Pisonia grandis and P. sechellarum in Seychelles: Identification of mycorrhizal fungi and description of new Tomentella species. Mycologia 2010, 102, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, F.; Roy, M.; Shahin, O.; Sthultz, C.; Duchemin, M.; Joffre, R.; Selosse, M.A. Ectomycorrhizal communities in a Mediterranean forest ecosystem dominated by Quercus ilex: Seasonal dynamics and response to drought in the surface organic horizon. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.W.; Smith, M.E.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Yang, Z.L. Two species of the Asian endemic genus Keteleeria form ectomycorrhizas with diverse fungal symbionts in Southwestern China. Mycorrhiza 2012, 22, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peintner, U.; Dämmrich, F. Tomentella alpina and other tomentelloid taxa fruiting in a glacier valley. Mycol. Prog. 2012, 11, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Nara, K.; Zong, K.; Wang, J.; Xue, S.G.; Peng, K.J.; Shen, Z.G.; Lian, C.L. Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities associated with masson pine (Pinus massoniana) and white oak (Quercus fabri) in a manganese mining region in Hunan Province, China. Fungal Ecol. 2014, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disyatat, N.R.; Yomyart, S.; Sihanonth, P.; Piapukiew, J. Community structure and dynamics of ectomycorrhizal fungi in a dipterocarp forest fragment and plantation in Thailand. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2016, 9, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wu, F.; Dai, Y.C.; Qin, W.M.; Yuan, H.S. Odontia aculeata and O. sparsa, two new species of tomentelloid fungi (Thelephorales, Basidiomycota) from the secondary forests of northeast China. Phytotaxa 2018, 372, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Cao, T.; Nguyễn, T.T.T.; Yuan, H.S. Six new species of Tomentella (Thelephorales, Basidiomycota) from tropical pine forests in Central Vietnam. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 864198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, E.M. Some species of Tomentella from North America. Mycologia 1960, 52, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.S.; Lu, X.; Dai, Y.C.; Hyde, K.D.; Kan, Y.H.; Kušan, I.; He, S.-H.; Liu, N.-G.; Sarma, V.V.; Zhao, C.-L.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 1277–1386: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 2020, 104, 1–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, E.M. Some extra-European species of Tomentella. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1966, 49, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorou, N.S.; Gardt, S.; Guissou, M.L.; Diabaté, M.; Agerer, R. Three new Tomentella species from West Africa identified by anatomical and molecular data. Mycol. Prog. 2012, 11, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.A.; Nara, K.; Ma, S.; Takano, T.; Liu, S.K. Ectomycorrhizal fungal community in alkaline-saline soil in northeastern China. Mycorrhiza 2009, 19, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Huang, J.; Long, D.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. Diversity and community structure of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Larix chinensis across the alpine treeline ecotone of Taibai Mountain. Mycorrhiza 2017, 27, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.W.; Gao, C.; Chen, L.; Buscot, F.; Goldmann, K.; Purahong, W.; Ji, N.N.; Wang, Y.L.; Lü, P.P.; Li, X.C.; et al. Host phylogeny is a major determinant of Fagaceae-associated ectomycorrhizal fungal community assembly at a regional scale. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; He, X.H.; Guo, L.D. Ectomycorrhizal fungus communities of Quercus liaotungensis Koidz of different ages in a northern China temperate forest. Mycorrhiza 2012, 22, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Taniguchi, T.; Xu, M.; Du, S.; Liu, G.B.; Yamanaka, N. Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities of Quercus liaotungensis along different successional stands on the Loess Plateau, China. J. For. Res. 2014, 19, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Q.; Yao, Q.Z. Morpho-anatomical characterization and phylogenetic analysis of five Tomentella ectomycorrhizae from Leigong Mountain, Guizhou. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2019, 21, 853–858. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).