Abstract

The vegan diet, often known as a plant-rich diet, consists primarily of plant-based meals. This dietary approach may be beneficial to one’s health and the environment and is valuable to the immune system. Plants provide vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals, and antioxidants, components that promote cell survival and immune function, allowing its defensive mechanisms to work effectively. The term “vegan diet” comprises a range of eating patterns that prioritize nutrient-rich foods such as fruits and vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds. In comparison to omnivorous diets, which are often lower in such products, the vegan diet has been favorably connected with changes in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk markers such as reduced body mass index (BMI) values, total serum cholesterol, serum glucose, inflammation, and blood pressure. Reduced intake of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), saturated fat, processed meat, and greater consumption of fiber and phytonutrients may improve cardiovascular health. However, vegans have much smaller amounts of nutrients such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), selenium, zinc, iodine, and vitamin B12, compared to non-vegans, which may lead to detrimental cardiovascular effects. This review aims to present the effect of plant-based diets (PBDs), specifically vegan diets, on the cardiovascular system.

Keywords:

vegan diet; plant-based; health benefits; nutrients; cardiovascular health; CVD; risk factors 1. Introduction

Plant-based diets, which include semi-vegetarian and vegetarian diets, emphasize cereals, fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts while limiting animal-based foods such as meat, dairy products, and eggs. In a plant-based diet, the level of animal food limitation varies greatly. There are several types of vegetarian diets, such as the vegan diet, which excludes all animal products, including eggs, milk, and milk derivatives, ovo-vegetarians who consume no animal meat or bioproducts besides eggs, and the lacto-ovo vegetarian diet, in which eggs, milk, and milk products are included, but no meat is consumed. There are also pescatarians, or people who eat plant-based diets that include dairy and fish [1,2].

Veganism seems to be the most stringent of all the plant-based diets since it excludes all animal-related substances [3]. A whole-food plant-based diet (WFPBD) is another sort of vegan diet that has demonstrated substantial advancements in cardiovascular health, diabetes, and cancer types [4]. More specifically, WFPBD features many fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and natural soy products while eliminating animal products, processed carbs, fat, and sugar.

The long-term impacts of plant-based diets on health outcomes may be difficult to disentangle from plant-based diet-associated behaviors (e.g., regular exercise, avoidance of tobacco and alcohol). However, according to observational research, lower risks of coronary artery disease, obesity, arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and some or perhaps all malignancies are linked with plant-based and vegetarian diets [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Randomized experiments have indicated that vegetarian and especially vegan diets have a positive influence on a variety of cardiovascular (CV) events [13].

The nutritional sufficiency and quality of plant-based and vegetarian diets should be evaluated individually, not based on how they are labeled, but on the type, amount, and diversity of nutrients ingested [14]. For instance, some studies, although not all [15,16], show that vegans may have poorer bone mineral density and a greater fracture risk due to reduced calcium intake. Individuals who follow a vegan diet may also fail to consume sufficient vitamin B12 and require vitamin B12 supplements [17,18]. The aim of this review is to summarize the contemporary evidence regarding the effect of a vegan diet on human health, underline the links between a vegan diet and cardiovascular diseases (CVD), including both the positive and negative effects of veganism on the CV system, and provide information regarding the potential therapeutic implications of a vegan diet in CVD.

This article summarizes what is known about the impact of a vegan diet on the cardiovascular system. To the best of our knowledge, our article provides a novel insight into this topic by up-to-date information, detailed tables as well as dynamic and more extensive figures. The effect of a vegan diet on the cardiovascular system is also compared to other diets.

2. Assessment of Vegan Nutrition concerning Health

Vegetarianism and veganism, which are defined in terms of a low frequency of consumption of animal foods, have grown in popularity and exposure over the last decade due to reasons ranging from environmental to animal welfare concerns, as well as possible health advantages. Vegans, whose numbers are rising in high-income countries across the Western world, make up an increasing fraction of the overall population. Moreover, even though the prevalence of vegans in Europe is estimated to be between 1 and 10%, the precise figure varies in each country, since veganism is primarily associated with religious and ethical views, environmental concerns, and cultural and social values [19].

Many health professional organizations have issued statements on vegan diets. Vegan diets should be properly designed and should be able to offer appropriate nourishment throughout life [20,21]. Even though it was once considered risky to be vegan throughout infancy, childhood, pregnancy, and lactation, it is now established that well-planned vegan diets may provide appropriate and balanced nutrition. Yet, the nutrients consumed on a vegan diet are not always beneficial. Vegans, for example, might eat plant-based meals that are heavy in sugar, salt, or harmful fats [22].

Furthermore, according to current data, the protein ratio of daily calorie consumption is greater in omnivores than in vegans [23]. Nevertheless, a well-planned vegan diet can meet general protein needs. Vegans should boost their protein consumption to 10% of their calorie intake [24]. Amino acids determine protein quality. Plant proteins include all necessary amino acids. While one research study found that combining different protein sources for each meal is not necessary if different plant foods are consumed throughout the day [25], other studies show that ingesting grains (methionine) and legumes (lysine) together delivers better effects on the bioavailability of key amino acids [26,27]. Vegan diets meet protein requirements through nuts, grains, seeds, legumes, green leafy vegetables, pseudo cereals (buckwheat, quinoa), soy, and other derivative products [28].

Vegan diets are beneficial in terms of fiber, beta-carotene, vitamin C and K, folic acid, magnesium, and potassium consumption, making them high-quality diets [29]. Such diets are often rich in ω-6 fatty acids as well [30]. Despite these advantages, they usually tend to feature insufficient intake of vitamin B12, vitamin D, calcium, selenium, zinc, and iodine and fewer accessible ω-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)), which can result in energy, nutritional, and micronutrient deficiencies. Therefore, supplementation of these nutrients is essential [31]. The recommended daily intake and supplementation of certain micronutrients in a vegan diet are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summarized daily intake and supplementation of vitamins and minerals in a vegan diet.

For instance, in a vegan diet, long-chain ω-3 fatty acids, which are critical for retina, brain, and cell membrane function, can only be consumed as a-linolenic acid (ALA), and it is therefore recommended that vegans take an algae-based DHA dietary supplement in addition to regular dietary intake of ALA sources [32]. Most significantly, approximately 5% to 6% of the daily energy requirement in vegan diets should come from saturated fat, mostly tropical or high-fat foods, according to the American Heart Organization [33].

3. Links between a Vegan Diet and Cardiovascular Diseases

3.1. Inflammatory Response as a Result of Unhealthy Dietary Patterns

Chronic Inflammation of the Vessel Walls Due to Unhealthy Diet

The standard diet that has become widely embraced in many countries over the past 40 years is rather unhealthy, containing relatively high amounts of alcohol [34] and processed foods [35], especially those with additives [36], and only a few fruits and vegetables and other meals rich in fiber and prebiotics [37,38]. An unhealthy diet can alter the structure and function of the gut microbiota and has been linked to increased gut permeability [39,40,41] and epigenetic modifications in the immune system [39], which can lead to low-grade endotoxemia and systemic chronic inflammation (SCI) of the vessel walls [39,40,41]. Similarly, foods with a high glycemic index, such as pure sugars and refined grains, which play an important role in most ultra-processed foods, can lead to increased oxidative stress and thus activate inflammatory genes [42].

Within this framework, uncontrolled alcohol consumption that triggers various reactions in the body causes chronic inflammation to increase over time rather than resolve. In the gut, for example, excess alcohol can lead to the proliferation of bacterial waste products, particularly endotoxins, substances that cause inflammation by activating proteins and immune cells. With more endotoxin production, the inflammation worsens instead of improving [40].

Trans fats, which raise low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and reduce high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and dietary salt (NaCl) are two other components of an unhealthy diet known to be pro-inflammatory. As stated by a recent cohort study of 44,551 French people, a 10 percent increase in the proportion of highly processed food consumption was associated with a 14 percent higher risk of all-cause mortality, consistent with the predicted adverse health outcomes of eating foods high in trans fats and sodium [43].

In this context, according to another observational study of 80,082 women in the Nurses’ Health Study cohort, it was revealed that higher consumption of trans fats, or to a lesser extent saturated fats, is correlated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), while higher consumption of polyunsaturated (non-hydrogenated) and monounsaturated fats is associated with a reduced risk [44]. The relationship to CHD risk can only partially be explained by the unfavorable effect of trans fats on the lipid profile.

At the same time, in a cross-sectional study of 730 women from the same patient cohort, markers of endothelial activation such as CRP (C-reactive protein), E-selectin, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM-1), and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1) were higher, suggesting that increased trans fatty acid intake may promote inflammation and adversely affect endothelial function. CRP levels were 73% higher in women in the highest quintile of trans fat intake than in the lowest quintile [45].

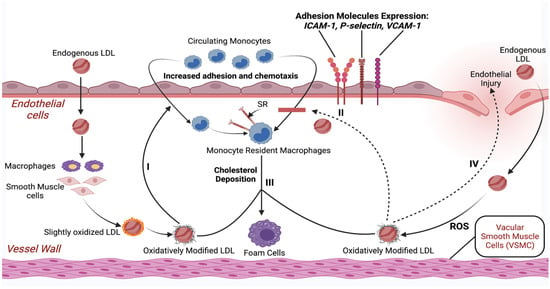

Endothelial dysfunction contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), which is a chronic inflammatory disease of the arterial wall mediated mostly by phagocytic (eating) leukocytes (white blood cells) such as monocytes and macrophages. This initiates a complicated pathogenic cascade that starts with the accumulation of circulating LDL in the subendothelial layer of the arteries [46,47,48,49]. Following an endothelial injury, LDL becomes mildly oxidized [50]. Further oxidation of LDL leads to fully oxidized LDL (ox-LDL), which is then avidly taken up by macrophages via scavenger receptors (SR) and ultimately transformed into foam cells (the hallmark of early fatty streak lesions) [51].

The expression and detachment of adhesion glycoproteins on the endothelium regulates leukocyte attachment to endothelial cells. The leukocyte binding to endothelial tissue is mediated by the aforementioned types of adhesion molecules (ICAM-1), (VCAM-1), as well as selectins (e.g., P-selectin and E-selectin) [52]. The pathophysiology of endothelial damage and atherosclerosis due to higher LDL levels resulting from an unhealthy diet is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of endothelial damage and initiation of the atherosclerotic process with only higher LDL levels as a risk factor. Abbreviations: LDL—low-density lipoprotein; ROS—reactive oxygen species; SR—scavenger receptor; ICAM-1—intercellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1—vascular cell adhesion protein-1. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 17 April 2021).

Overall, dietary patterns that are high in sugar, alcohol, saturated and trans fatty acids, and refined starches and low in natural antioxidants and fiber from fruits, vegetables, and whole grains may activate the innate immune system, most likely through an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines and a decrease in anti-inflammatory cytokines. This imbalance may stimulate the formation of a pro-inflammatory state, which causes endothelial dysfunction at the vascular level, resulting in a predisposition to atherosclerotic plaque formation. This can lead susceptible people to an increased prevalence of CHD.

It is vital to understand that both an unhealthy diet and a vegan diet can initiate chronic inflammation if a vegan diet contains inadequate amounts of essential vitamins and nutrients as well as omega-3 fatty acids [31].

3.2. Benefits/Risks of a Vegan Diet for the Cardiovascular System

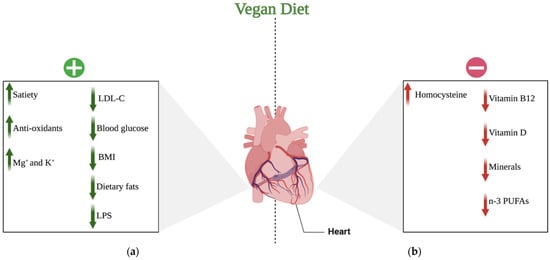

CVD is the leading cause of mortality, currently accounting for one-third of all deaths worldwide and growing in prevalence. Examples of CVDs include CHD, peripheral artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, rheumatic and congenital heart disease, and venous thromboembolism. In this context, vegan diets are considered to improve health and decrease the risk of CVD. On the other hand, according to some studies, a vegan diet may be related to reduced intake of protein, vitamins, or minerals, and thus should also be evaluated in terms of harmful effects. The research on veganism is contradictory and inadequately evaluated [53]. The vast majority of studies on health effects of vegan and plant-based diets were short term and cannot give accurate data on cardiovascular outcomes, which has mostly been estimated based on the changes in biomarker concentrations. More studies with hard endpoints such as major adverse cardiovascular events are required to fully understand the effects of vegan and vegetarian diet on the cardiovascular system. The potential positive and negative impacts of a vegan diet on the CV system discussed in the following paragraphs are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Potential effects of a vegan diet on the cardiovascular system: (a) positive effects of a vegan diet on the cardiovascular system; (b) negative effects of a vegan diet on the cardiovascular system. Abbreviations: (+) positive; (−) negative; ↑ increase; ↓ decrease; LDL-C—low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; BMI—body mass index; LPS—lipopolysaccharide; K+—potassium cations; Mg+—magnesium cations; n-3 PUFAs—n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 17 April 2021).

3.2.1. The Positive Effects of Veganism on the Cardiovascular System

PBDs, especially vegan diets, have been shown to provide several health benefits [54]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the benefits of a vegan diet on human health are due to increased daily consumption of fresh fruits, vegetables, cereal grains, nuts, legumes, and seeds, indicating that vegans make healthier lifestyle choices than those who follow other dietary patterns [55]. Some of the potential health merits include a decreased rate of certain conditions, such as CVD. Vegan diets have been reported to be low-risk therapies for decreasing BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP), and LDL levels, minimizing the incidence of coronary heart disease events by 40% [56].

Additionally, the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies, which were eventually drawn from the analyses of only two studies, indicated that greater adherence to the PBDs was significantly associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality (10%) (HR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.82, 0.99; I2 = 90.7%, pheterogeneity < 0.001), and CHD mortality (23%). Based on the same study, it was also found that among vegan diets, compliance with a usual vegetarian diet might protect against CVD and CHD mortality [57].

Because of its low saturated fatty acid (SFAs) and high fiber content, the vegan diet is characterized by low energy intake. Dietary fibers are a diverse group of plant molecules (carbohydrate polymers with ten or more monomer units) with varying physical and chemical characteristics [58]. Water-soluble (SFs) and insoluble fibers (IFs) are the two most common types. Because these fibers are not hydrolyzed by digestive enzymes, they are not completely digested in the human gut [59]. They alter intestinal function by regulating intestinal motions, increasing fecal bulk, and avoiding constipation, among other things. SF, for instance, dissolves in water and forms thick solutions (gels) in the intestinal lumen, delaying or partially reducing carbohydrate, lipid, and cholesterol absorption. These viscous gels can also delay emptying of the stomach and prolong food absorption, enhancing satiety and altering insulin and glycemic post-prandial responses [60].

Moreover, we know that meals of vegetable origin are high in polyphenols, which are natural bioactive chemicals generated by plants as secondary metabolites [61]. Polyphenols may also benefit CV health by inhibiting platelet aggregation, reducing inflammation of the vessel walls, modulating apoptotic processes, lowering LDL oxidation, and improving the lipid profile [62]. Several in vitro investigations have revealed that polyphenols have a high antioxidant capacity due to their ability to neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS). Their antioxidant properties, presumably paired with their ability to modify nitric oxide (NO) synthesis, allow them to protect endothelial function [63].

Other antioxidant minerals found in a vegan diet include vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene, potassium, and magnesium. Potassium has been proven to decrease blood pressure and the risk of stroke due to its favorable effects on endothelial function and vascular homeostasis [64]. Furthermore, magnesium has been linked to better cardiometabolic outcomes due to its effect on glucose metabolism as well as its anti-inflammatory, vasodilatory, and antiarrhythmic characteristics [65].

The influence on cholesterol metabolism is another important way that a vegan diet might benefit CV health. The low SFA concentration and high unsaturated fat content can enhance the lipid profile. SFAs have been found to activate the pro-inflammatory toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) signaling pathway, resulting in the production of cytokines capable of triggering a chronic inflammatory state [66,67]. SFAs can also interact with the gut microbiota by facilitating the transfer of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is a powerful endotoxin, a mediator of systemic inflammation, and a driver of septic shock [68].

Various studies, however, have revealed that polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) activate several anti-inflammatory pathways. As a result, a diet high in unsaturated fats and low in SFAs can lower the risk of CVDs through its potential anti-inflammatory effects [69,70].

A meta-analysis of observational studies that compared the vegan diets to omnivorous diets observed that the vegan diet has less energy and saturated fat as a result it protects against cardiometabolic conditions. The authors discovered a decrease in fasting blood glucose and BMI and an improvement in the lipid profile [71].

3.2.2. The Negative Effect of Veganism on the Cardiovascular System

In contrast, lower intake of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (i.e., DHA and EPA), vitamins (i.e., vitamin B12 and D), specific nutrients, including selenium, zinc, iodine, and calcium, as well as higher levels of essential amino acids (i.e., homocysteine), may explain some of the unfavorable CV effects associated with vegan diets, such as the potential increased risk of ischemic stroke [72]. One study has found that vegans and vegetarians had a higher risk of ischemic stroke than people who ate animal products (HR, 1.54; 95 percent CI, 0.95–2.48) [53].

Nevertheless, systematic reviews and meta-analyses that compared vegetarians and vegans to nonvegetarians has shown no clear association with stroke or subtypes of stroke for vegans and vegetarians [73,74]. At the same time and as specified by a meta-analysis, with a large-scale study design of 657,433 participants, the incidence of total stroke was lower among vegetarians in studies conducted in Asia than nonvegetarians (HR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.45–0.95; I2 = 54%, n = 3). Furthermore, the same review found that although there is no strong association between vegetarian diets and a reduced risk of stroke in young adults, there is evidence that older participants aged 50–65 years following a vegetarian pattern exhibited a lower incidence of stroke than nonvegetarians [74].

Although a plant-based diet and especially a vegan diet is believed to be healthy, it can nonetheless result in a higher level of essential amino acids. The most important molecule in this study is homocysteine (Hcy), which has been identified as a risk factor for atherosclerotic vascular disease and hypercoagulability. Given that, there is evidence of a link between hyperhomocysteinemia arising from a vegan diet and CVD, such as heart attacks and strokes [75].

In this regard, and as previously stated, while plant foods provide various nutrients, including dietary fiber and phytochemicals, they do not contain enough vitamin B12 to meet the needs of their consumers, leading to severe deficiency. Deficiency in vitamin B12 will eventually result in hyperhomocysteinemia [76]. Subsequently, because it lowers vascular flexibility and alters homeostasis, elevated homocysteine will induce vascular endothelial impairment. It may also aggravate the negative consequences of risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, cholesterol, and lipoprotein metabolism [77]. Most critically, Hcy has been recognized as a significant CVD risk factor [78].

Besides causing hyperhomocysteinemia, a vitamin B12 deficiency caused by avoiding animal-based meals can also contribute to an increased risk of cardiac conditions via its function in macrocytosis [79]. To be more specific, a deficiency in vitamin B12 can increase the risk of macrocytic anemia, a condition arising from the abnormal growth of red blood cells. In this way, it leads to various diseases, such as heart failure (HF), coronary artery disease, and stroke. It can additionally decrease oxygen delivery and the carrying capacity of blood vessels, undermining circulation’s primary role.

Similarly, vitamin D deficiency, which can be caused by veganism, increases the risk of CVD and is linked to other well-known risk factors for heart diseases such as high blood pressure, obesity, and diabetes [80,81,82]. In particular, low levels of the vitamin may initially predispose the body to congestive heart failure and chronic blood vessel inflammation (associated with hardening of the arteries). It might also change hormone levels, increasing insulin resistance and thus raising the risk of diabetes [83].

To date, certain cross-sectional studies have connected vitamin D deficiency to an increased risk of CVD, such as hypertension, heart failure, and ischemic heart disease [84]. Simultaneously, other prospective studies have found that vitamin D deficiency increases the risk of incident hypertension or sudden cardiac death in individuals who already have CVD [83].

Not only vitamin deficiencies, but other dietary components found in vegan diets can promote an inflammatory response and hence contribute to the development of chronic inflammation [6,85]. These include micronutrient deficiencies, such as zinc and selenium, caused by eating processed or refined foods low in vitamins and minerals, as well as insufficient omega-3 levels, notably EPA and DHA, which impact the resolution phase of inflammation. Eventually, inflammation will induce an atherogenic response, resulting in serious health problems, including arrhythmias, heart failure, and CHD [86].

4. Therapeutic Implications

CVD prevention is a major public health concern. It has long been known that vegetarians, and specifically vegans, experience occurrences of chronic CVD, including ischemic heart disease, less frequently [87]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that incidences of risk factors and comorbidities such as angina and heart failure, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and obesity, as well as hypertension, can be reduced due to a plant-based diet [56,88]. Even in cases of endothelial damage, a vegan diet is beneficial in slowing or stopping the advancement of coronary atheroma [11,89,90]. These observations have sparked an investigation into the possibility of adopting a vegan diet as a therapeutic tool in preventing or treating CVDs. A summary of clinical studies evaluating relevant outcomes associated with the CV system in patients following a vegan diet is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of relevant outcomes and main findings in the included studies.

The Role of a Vegan Diet in the Prevention of CVD

As reported by evidence from interventional trials, a low-fat vegetarian and vegan diet has been effective in treating coronary artery disease (CAD) for over 45 years. Research has suggested that a well-planned plant-based diet is equally as successful at lowering cholesterol as statin medications and a highly advantageous alternative to other treatment strategies [102]. At the same time, it has the distinct benefits of having no side effects or contraindications, is affordable, and has high patient compliance [103].

As aforementioned, vegetarians, particularly vegans, have a decreased incidence of hypercholesterolemia, primarily total and LDL cholesterol [104]. The chief reason for this is that they have increased insulin sensitivity and thus lowered cholesterol production [105]. The fact that vegans have lower cholesterol levels indicates a reduction in the risk of atherogenesis, and consequently CAD. Furthermore, due to their efficiency in eliminating potentially atherogenic remnants, the metabolisms of vegans have been discovered to have superior control of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins [106], thereby exerting protective effects against obesity and the incidence of diabetes.

A study that compared the weight change between patients on a Mediterranean diet and those on a vegan diet discovered that the vegan diet resulted in a 6.0 kg decrease in mean body weight, compared to no change on the Mediterranean diet (treatment effect 6.0 kg (95% CI 7.5 to 4.5); p 0.001). Most of the weight loss during the vegan diet was due to the decline in fat mass and visceral fat volume (treatment effect 3.4 kg (95% CI 4.7 to 2.2); p 0.001; and 314.5 cm3 (95% CI 446.7 to 182.4); p 0.001, respectively). In the end, of the 52 study participants, only 26 lost weight on the Mediterranean diet, compared to 48 following the vegan diet [107].

Meanwhile, a recent case report described the effects of a plant-based diet on a 79-year-old patient with diagnosed triple vessel disease (80–95% narrowing) and left ventricular systolic failure (ejection fraction = 35%), all in the setting of worsening dyspnea. Two months on a plant-based diet resulted in clinically significant weight and cholesterol reductions, as well as enhanced exercise tolerance and ejection fraction (+15%) [108]. Other systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that vegan diets enhance glycemic management, with substantial reductions in HbA1c levels [109], lowering the chance of developing type 2 diabetes.

Likewise, a systematic review, which assessed how effective the PBDs are for treating obesity and related cardiometabolic health outcomes, stated that plant-based diets demonstrate improved weight control and cardiometabolic outcomes related to lipids, cardiovascular end points, blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, A1C, and fasting glucose, and a lower risk of diabetes compared with usual diets and in some cases standard health-oriented diets such as the American Heart Association (AHA), American Diabetic Association (ADA), and Mediterranean diets. This study suggested that plant-predominant diets practiced as part of sustained lifestyle interventions can stabilize or even reverse DM 2 and CVD [110].

The impact of a vegan diet on blood pressure is important because arterial hypertension is the most common CVD risk factor [111]. The study by Pettersen et al. showed that vegans, lacto-ovo vegetarians, and partial vegetarians had lower estimated odds of arterial hypertension (OR = 0.37; 95% CI: 0.19–0.74; OR = 0.57; 95% CI: 0.36–0.92 and OR = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.50–1.70) than non-vegetarians [112]. In a meta-analysis by Gibbs et al., a vegan diet was not significantly associated with systolic blood pressure (−1.30 mmHg; 95% CI: −3.90,1.29) [113]. In addition, in a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials by Termannsen et al., no significant effect of a vegan diet on blood pressure was found [114]. In a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials by Lopez et al., more optimistic results were obtained. A vegan diet was found to significantly reduce systolic (−4.10 mmHg; 95% CI: − 8.14 to − 0.06) and diastolic (−4.01 mmHg; 95% CI: −5.97 to −2.05) blood pressure in subjects with baseline systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg. In subjects with baseline systolic blood pressure < 130 mmHg, no significant antihypertensive effect of a vegan diet was observed [115]. The results of these studies indicate that the adoption of a vegan diet should be seen as more important in supporting the treatment, rather than the prevention, of arterial hypertension.

Exercise and weight loss are first-line treatments for hypertension at all stages. However, a cross-sectional study indicated that a vegan diet is the most important intervention. This study compared the blood pressure of inactive vegans, endurance athletes consuming a Western diet and running an average of 48 miles per week, and inactive participants that were only consuming a Western diet. Based on the findings of the study, blood pressure was remarkably lower in the vegan group [54].

The positive results associated with the preceding study are most likely attributable to the abundance of antioxidant minerals prevalent in a vegan diet, such as magnesium and potassium. Because of their beneficial effects on endothelial function, and their antiarrhythmic and vasodilatory properties, both potassium and magnesium have been proven to lower blood pressure and thus contribute to the electrical stability of the heart, resulting in better cardiometabolic outcomes [65].

At this point, it is crucial to indicate some of the characteristics and potential differences between pure veganism and other diets with regard to cardiovascular effects. The main differences are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison between vegan diet and other diets with respect to CV system.

5. Outlook and Conclusions

PBDs, particularly vegan diets, which exclude all animal-based foods, reflect a feeding pattern that groups have followed for many years, primarily for ethical, ideological, and environmental reasons [19]. Extensive research has been carried out to show the positive as well as negative impacts of a vegan diet on the CV system. Vegan diets are thought to improve health and reduce the risk of CVDs, including CAD, arrhythmias, and heart failure [53]. However, according to some studies, a vegan diet may be associated with lower intake of protein, vitamins, or minerals [116], inducing chronic inflammation and, thus, an atherogenic response.

Finally, a vegan diet is mostly used to improve body weight and composition [117]. Accordingly, this dietary pattern seems to be a feasible and reliable approach to preventing and treating CVD and its risk factors [53] since it minimizes the risk of hypercholesterolemia, hypertension and CAD, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. Especially considering that CAD is such a widespread cause of disability and mortality [118], a well-planned vegan diet combined with appropriate nutritional supplementation might be considered preventative for patients at high CVD risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.; methodology, M.K., S.S., K.J.F. and A.G.; software, A.G.; validation, S.R. and S.S.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, M.K. and S.S.; resources, M.K., S.S., K.J.F. and A.G.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, S.R., S.S., K.J.F. and A.G.; visualization, S.S. and K.J.F.; supervision, K.J.F. and A.G.; project administration, A.G. and S.S.; funding acquisition, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Appleby, P.N.; Key, T.J. The Long-Term Health of Vegetarians and Vegans. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlich, M.J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Sabaté, J.; Fan, J.; Singh, P.N.; Fraser, G.E. Patterns of Food Consumption among Vegetarians and Non-Vegetarians. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 1644–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdowsian, H.R.; Barnard, N.D. Effects of Plant-Based Diets on Plasma Lipids. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009, 104, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ornish, D.; Scherwitz, L.W.; Billings, J.H.; Lance Gould, K.; Merritt, T.A.; Sparler, S.; Armstrong, W.T.; Ports, T.A.; Kirkeeide, R.L.; Hogeboom, C.; et al. Intensive Lifestyle Changes for Reversal of Coronary Heart Disease. JAMA 1998, 280, 2001–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V.; Al-Weshahy, A. Plant-Based Diets and Control of Lipids and Coronary Heart Disease Risk. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2008, 10, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.J. Health Effects of Vegan Diets. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1627S–1633S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, N.D.; Katcher, H.I.; Jenkins, D.J.; Cohen, J.; Turner-McGrievy, G. Vegetarian and Vegan Diets in Type 2 Diabetes Management. Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.; Sabaté, J. Beyond Meatless, the Health Effects of Vegan Diets: Findings from the Adventist Cohorts. Nutrients 2014, 6, 2131–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlich, M.J.; Singh, P.N.; Sabaté, J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fan, J.; Knutsen, S.; Beeson, W.L.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian Dietary Patterns and Mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Caulfield, L.E.; Rebholz, C.M. Healthy Plant-Based Diets Are Associated with Lower Risk of All-Cause Mortality in US Adults. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Vegetarian, Vegan Diets and Multiple Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3640–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segovia-Siapco, G.; Sabaté, J. Health and Sustainability Outcomes of Vegetarian Dietary Patterns: A Revisit of the EPIC-Oxford and the Adventist Health Study-2 Cohorts. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 72, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satija, A.; Hu, F.B. Plant-Based Diets and Cardiovascular Health. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 28, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, E.H.; Tanzman, J.S. What Do Vegetarians in the United States Eat? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 626S–632S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho-Pham, L.T.; Vu, B.Q.; Lai, T.Q.; Nguyen, N.D.; Nguyen, T.V. Vegetarianism, Bone Loss, Fracture and Vitamin D: A Longitudinal Study in Asian Vegans and Non-Vegans. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Pham, L.T.; Nguyen, P.L.T.; Le, T.T.T.; Doan, T.A.T.; Tran, N.T.; Le, T.A.; Nguyen, T.V. Veganism, Bone Mineral Density, and Body Composition: A Study in Buddhist Nuns. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 20, 2087–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dary, O. Establishing Safe and Potentially Efficacious Fortification Contents for Folic Acid and Vitamin B12. Food Nutr. Bull. 2008, 29, S214–S224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malouf, R.; Grimley Evans, J. Folic Acid with or without Vitamin B12 for the Prevention and Treatment of Healthy Elderly and Demented People. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 4, CD004514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allès, B.; Baudry, J.; Méjean, C.; Touvier, M.; Péneau, S.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Comparison of Sociodemographic and Nutritional Characteristics between Self-Reported Vegetarians, Vegans, and Meat-Eaters from the NutriNet-Santé Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menal-Puey, S.; Marques-Lopes, I. Development of a Food Guide for the Vegetarians of Spain. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2017, 117, 1509–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, C.; Baroni, L.; Bertini, I.; Ciappellano, S.; Fabbri, A.; Papa, M.; Pellegrini, N.; Sbarbati, R.; Scarino, M.L.; Siani, V.; et al. Position Paper on Vegetarian Diets from the Working Group of the Italian Society of Human Nutrition. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 1037–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyett, P.A.; Sabaté, J.; Haddad, E.; Rajaram, S.; Shavlik, D. Vegan Lifestyle Behaviors: An Exploration of Congruence with Health-Related Beliefs and Assessed Health Indices. Appetite 2013, 67, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobiecki, J.G.; Appleby, P.N.; Bradbury, K.E.; Key, T.J. High Compliance with Dietary Recommendations in a Cohort of Meat Eaters, Fish Eaters, Vegetarians, and Vegans: Results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition–Oxford Study. Nutr. Res. 2016, 36, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baroni, L.; Goggi, S.; Battaglino, R.; Berveglieri, M.; Fasan, I.; Filippin, D.; Griffith, P.; Rizzo, G.; Tomasini, C.; Tosatti, M.; et al. Vegan Nutrition for Mothers and Children: Practical Tools for Healthcare Providers. Nutrients 2018, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitzmann, C. Vegetarian Nutrition: Past, Present, Future. Am. Soc. Nutr. 2014, 100 (Suppl. S1), 496S–502S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosh, S.M.; Yada, S. Dietary Fibres in Pulse Seeds and Fractions: Characterization, Functional Attributes, and Applications. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, R.; Hughes, T.; Chung, H.J.; Liu, Q. Composition, Molecular Structure, Properties, and Modification of Pulse Starches: A Review. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Tomar, M.; Punia, S.; Dhakane-Lad, J.; Dhumal, S.; Changan, S.; Senapathy, M.; Berwal, M.K.; Sampathrajan, V.; Sayed, A.A.S.; et al. Plant-Based Proteins and Their Multifaceted Industrial Applications. LWT 2022, 154, 112620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüpbach, R.; Wegmüller, R.; Berguerand, C.; Bui, M.; Herter-Aeberli, I. Micronutrient Status and Intake in Omnivores, Vegetarians and Vegans in Switzerland. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, A.V.; Davis, B.C.; Garg, M.L. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Vegetarian Diets. Med. J. Aust. 2012, 1, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Winckel, M.; vande Velde, S.; de Bruyne, R.; van Biervliet, S. Clinical Practice: Vegetarian Infant and Child Nutrition. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2011, 170, 1489–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, R.A.; Muhlhausler, B.; Makrides, M. Conversion of Linoleic Acid and Alpha-Linolenic Acid to Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (LCPUFAs), with a Focus on Pregnancy, Lactation and the First 2 Years of Life. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2011, 7, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hever, J. Plant-Based Diets: A Physician’s Guide. Perm. J. 2016, 20, 15-082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, B.F.; Chou, S.P.; Saha, T.D.; Pickering, R.P.; Kerridge, B.T.; Ruan, W.J.; Huang, B.; Jung, J.; Zhang, H.; Fan, A.; et al. Prevalence of 12-Month Alcohol Use, High-Risk Drinking, and DSM-IV Alcohol Use Disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Steele, E.; Baraldi, L.G.; Louzada, M.L.d.C.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Mozaffarian, D.; Monteiro, C.A. Ultra-Processed Foods and Added Sugars in the US Diet: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassaing, B.; van de Wiele, T.; de Bodt, J.; Marzorati, M.; Gewirtz, A.T. Dietary Emulsifiers Directly Alter Human Microbiota Composition and Gene Expression Ex Vivo Potentiating Intestinal Inflammation. Gut 2017, 66, 1414–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrera-Bastos, P.; O’Keefe, F.; Lindeberg, S.; Cordain, L. The Western Diet and Lifestyle and Diseases of Civilization. Res. Rep. Clin. Cardiol. 2011, 2, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, J.U.S. Trends in Food Availability and a Dietary Assessment of Loss-Adjusted Food Availability, 1970–2014. Econ. Inf. Bull. 2017, 166, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.L.; Yap, Y.A.; McLeod, K.H.; Mackay, C.R.; Mariño, E. Dietary Metabolites and the Gut Microbiota: An Alternative Approach to Control Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2016, 5, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishehsari, F.; Magno, E.; Swanson, G.; Desai, V.; Voigt, R.M.; Forsyth, C.B.; Keshavarzian, A. Alcohol and Gut-Derived Inflammation. Alcohol Res. 2017, 38, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, A.; Matthias, T. Changes in Intestinal Tight Junction Permeability Associated with Industrial Food Additives Explain the Rising Incidence of Autoimmune Disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2015, 14, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, S.; Hancock, D.P.; Petocz, P.; Ceriello, A.; Brand-Miller, J. High-Glycemic Index Carbohydrate Increases Nuclear Factor-B Activation in Mononuclear Cells of Young, Lean Healthy Subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1188–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnabel, L.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Touvier, M.; Srour, B.; Hercberg, S.; Buscail, C.; Julia, C. Association Between Ultraprocessed Food Consumption and Risk of Mortality Among Middle-Aged Adults in France. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rank, F.; Eir, M.; Tampfer, J.S.; Nn, J.O.A.; Anson, E.M.; Imm, R.R.; Olditz, R.A.C.; Osner, E.A.R.; Harles, C.; Ennekens, H.H.; et al. Dietary Fat Intake and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Garcia, E.; Schulze, M.B.; Meigs, J.B.; Manson, J.E.; Rifai, N.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Nutritional Epidemiology Consumption of Trans Fatty Acids Is Related to Plasma Biomarkers of Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionescu, N.; Vasile, E.; Lupu, F.; Popescu, G. Prelesional Events in Atherogenesis. Accumulation of Extracellular Cholesterol-Rich Liposomes in the Arterial Intima and Cardiac Valves of the Hyperlipidemic Rabbit. Am. J. Pathol. 1986, 123, 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, C.J.; Valente, A.J.; Sprague, E.A.; Kelley, J.L.; Nerem, R.M. The Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis: An Overview. Clin. Cardiol. 1991, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R. Atherosclerosis: A Problem of the Biology of Arterial Wall Cells and Their Interactions with Blood Components. Arteriosclerosis 1981, 1, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virmani, R.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Burke, A.P.; Farb, A.; Schwartz, S.M. Lessons from Sudden Coronary Death. Arter. Thromb Vasc. Biol. 2000, 20, 1262–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Haberland, M.E.; Jien, M.L.; Shih, D.M.; Lusis, A.J. Endothelial Responses to Oxidized Lipoproteins Determine Genetic Susceptibility to Atherosclerosis in Mice. Circulation 2000, 102, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golia, E.; Limongelli, G.; Natale, F.; Fimiani, F.; Maddaloni, V.; Pariggiano, I.; Bianchi, R.; Crisci, M.; D’Acierno, L.; Giordano, R.; et al. Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Target. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2014, 16, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panés, J.; Perry, M.; Granger, D.N. Leukocyte-Endothelial Cell Adhesion: Avenues for Therapeutic Intervention. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 126, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, J.; van Daalen, K.R.; Thayyil, A.; Cocco, M.T.d.A.R.R.; Caputo, D.; Oliver-Williams, C. A Systematic Review of the Association Between Vegan Diets and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1539–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, L.; Meyer, T.E.; Klein, S.; Holloszy, J.O. Long-Term Low-Calorie Low-Protein Vegan Diet and Endurance Exercise Are Associated with Low Cardiometabolic Risk. Rejuvenation Res. 2007, 10, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Giovannucci, E.; Boffetta, P.; Fadnes, L.T.; Keum, N.N.; Norat, T.; Greenwood, D.C.; Riboli, E.; Vatten, L.J.; Tonstad, S. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease, Total Cancer and All-Cause Mortality—A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, F.M.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Wu, J.H.Y.; Appel, L.J.; Creager, M.A.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Miller, M.; Rimm, E.B.; Rudel, L.L.; Robinson, J.G.; et al. Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 136, e1–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.; Hezaveh, E.; Jalilpiran, Y.; Jayedi, A.; Wong, A.; Safaiyan, A.; Barzegar, A. Plant-based diets and risk of disease mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 62, 7760–7772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holscher, H.D. Dietary Fiber and Prebiotics and the Gastrointestinal Microbiota. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, D.; Michael, M.; Rajput, H.; Patil, R.T. Dietary Fibre in Foods: A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervik, A.K.; Svihus, B. The Role of Fiber in Energy Balance. J. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 2019, 4983657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.B.; Rizvi, S.I. Plant Polyphenols as Dietary Antioxidants in Human Health and Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2009, 2, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habauzit, V.; Morand, C. Evidence for a Protective Effect of Polyphenols-Containing Foods on Cardiovascular Health: An Update for Clinicians. Ther. Adv. Chronic. Dis. 2012, 3, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, C.C.; Rasmussen, H.E. Polyphenols, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2013, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Rosell, M.S. Health Effects of Vegetarian and Vegan Diets. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2006, 65, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, R.; Bradlee, M.; Singer, M.; Moore, L. Higher Intakes of Potassium and Magnesium, but Not Lower Sodium, Reduce Cardiovascular Risk in the Framingham Offspring Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, L.A.J. Targeting Signal Transduction as a Strategy to Treat Inflammatory Diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2006, 5, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.H.; Kim, J.A.; Lee, J.Y. Mechanisms for the Activation of Toll-like Receptor 2/4 by Saturated Fatty Acids and Inhibition by Docosahexaenoic Acid. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 785, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, K.L. The Science of Fatty Acids and Inflammation. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 293S–301S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.C. The Role of Dietary N-6 Fatty Acids in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2007, 8, S42–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, H.; Basu, S.; Cederholm, T.; Risérus, U. Serum Fatty Acid Composition and Indices of Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase Activity Are Associated with Systemic Inflammation: Longitudinal Analyses in Middle-Aged Men. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 1186–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benatar, J.R.; Stewart, R.A.H. Cardiometabolic risk factors in vegans; A meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabri, A.; Kumar, A.; Verghese, E.; Alameh, A.; Kumar, A.; Khan, M.S.; Khan, S.U.; Michos, E.D.; Kapadia, S.R.; Reed, G.W.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Effect of Vegetarian Diet on Ischemic Heart Disease and All-Cause Mortality. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 7, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dybvik, J.S.; Svendsen, M.; Aune, D. Vegetarian and vegan diets and the risk of cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease and stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 62, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.-W.; Yu, L.-H.; Tu, Y.-K.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Chen, L.-Y.; Loh, C.-H.; Chen, T.-L. Risk of Incident Stroke among Vegetarians Compared to Nonvegetarians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenoy, V.; Mehendale, V.; Prabhu, K.; Shetty, R.; Rao, P. Correlation of Serum Homocysteine Levels with the Severity of Coronary Artery Disease. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2014, 29, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankar, A.; Bhimji, S.S. Vitamin B12 Deficiency; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022.

- Baszczuk, A.; Kopczyński, Z. Hyperhomocysteinemia in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw. 2014, 68, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybulska, B.; Kłosiewicz-Latoszek, L. Homocysteine—Is It Still an Important Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Disease? Kardiol. Pol. 2015, 73, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, R. Is Vitamin B12 Deficiency a Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Disease in Vegetarians? Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 48, e11–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fraser, G.E. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Status of Vegetarians, Partial Vegetarians, and Nonvegetarians: The Adventist Health Study-2. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1686S–1692S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, J.; Targher, G.; Smits, G.; Chonchol, M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Deficiency Is Independently Associated with Cardiovascular Disease in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Atherosclerosis 2009, 205, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, L.A.; Wood, R.J. Vitamin D Status and the Metabolic Syndrome. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 64, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheiri, B.; Abdalla, A.; Osman, M.; Ahmed, S.; Hassan, M.; Bachuwa, G. Vitamin D Deficiency and Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Narrative Review. Clin. Hypertens. 2018, 24, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brøndum-Jacobsen, P.; Benn, M.; Jensen, G.B.; Nordestgaard, B.G. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels and Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease, Myocardial Infarction, and Early Death: Population-Based Study and Meta-Analyses of 18 and 17 Studies. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 2794–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzel, J.; Jabakhanji, A.; Biemann, R.; Mai, K.; Abraham, K.; Weikert, C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the associations of vegan and vegetarian diets with inflammatory biomarkers. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, N.M.; Wang, L.; Herren, A.W.; Wang, J.; Shenasa, F.; Bers, D.M.; Lindsey, M.L.; Ripplinger, C.M. Atherosclerosis Exacerbates Arrhythmia Following Myocardial Infarction: Role of Myocardial Inflammation. Heart Rhythm. Off. J. Heart Rhythm. Soc. 2015, 12, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Yang, B.; Zheng, J.; Li, G.; Wahlqvist, M.L.; Li, D. Systematic Review Cardiovascular Disease Mortality and Cancer Incidence in Vegetarians: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 60, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrone, G.; Guerriero, C.; Palazzetti, D.; Lido, P.; Marolla, A.; di Daniele, F.; Noce, A. Vegan Diet Health Benefits in Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2021, 13, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esselstyn, C.B., Jr.; Gendy, G.; Doyle, J.; Golubic, M.; Roizen, M.F. A way to reverse CAD? J. Fam. Pract. 2014, 63, 356–364b. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, N.S.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Sabate, J.; Fraser, G.E. Nutrient Profiles of Vegetarian and Nonvegetarian Dietary Patterns. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaartinen, K.; Lammi, K.; Hypen, M.; Nenonen, M.; Hänninen, O. Vegan Diet Alleviates Fibromyalgia Symptoms. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2009, 29, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, N.D.; Scialli, A.R.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; Lanou, A.J.; Glass, J. The Effects of a Low-Fat, Plant-Based Dietary Intervention on Body Weight, Metabolism, and Insulin Sensitivity. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner-McGrievy, G.M.; Barnard, N.D.; Scialli, A.R. A Two-Year Randomized Weight Loss Trial Comparing a Vegan Diet to a More Moderate Low-Fat Diet. Obesity 2007, 15, 2276–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkan, A.C.; Sjöberg, B.; Kolsrud, B.; Ringertz, B.; Hafström, I.; Frostegård, J. Gluten-Free Vegan Diet Induces Decreased LDL and Oxidized LDL Levels and Raised Atheroprotective Natural Antibodies against Phosphorylcholine in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomized Study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2008, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, N.D.; Cohen, J.; Jenkins, D.J.A.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; Gloede, L.; Green, A.; Ferdowsian, H. A Low-Fat Vegan Diet and a Conventional Diabetes Diet in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized, Controlled, 74-Wk Clinical Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1588S–1596S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdowsian, H.R.; Barnard, N.D.; Hoover, V.J.; Katcher, H.I.; Levin, S.M.; Green, A.A.; Cohen, J.L. A Multicomponent Intervention Reduces Body Weight and Cardiovascular Risk at a GEICO Corporate Site. Am. J. Health Promot. 2010, 24, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Xu, J.; Agarwal, U.; Gonzales, J.; Levin, S.; Barnard, N.D. A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial of a Plant-Based Nutrition Program to Reduce Body Weight and Cardiovascular Risk in the Corporate Setting: The GEICO Study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, N.; Wilson, L.; Smith, M.; Duncan, B.; McHugh, P. The BROAD Study: A Randomised Controlled Trial Using a Whole Food Plant-Based Diet in the Community for Obesity, Ischaemic Heart Disease or Diabetes. Nutr. Diabetes 2017, 7, e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakše, B.; Pinter, S.; Jakše, B.; Bučar Pajek, M.; Pajek, J. Effects of an Ad Libitum Consumed Low-Fat Plant-Based Diet Supplemented with Plant-Based Meal Replacements on Body Composition Indices. Biomed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9626390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahleova, H.; Dort, S.; Holubkov, R.; Barnard, N.D. A Plant-Based High-Carbohydrate, Low-Fat Diet in Overweight Individuals in a 16-Week Randomized Clinical Trial: The Role of Carbohydrates. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, N.D.; Levin, S.M.; Gloede, L.; Flores, R. Turning the Waiting Room into a Classroom: Weekly Classes Using a Vegan or a Portion-Controlled Eating Plan Improve Diabetes Control in a Randomized Translational Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardiol, J.; Ther, C.; Rose, S.; Strombom, A. A Comprehensive Review of the Prevention and Treatment of Heart Disease with a Plant-Based Diet. J. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2018, 12, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Strombom, A. Preventing Stroke with a Plant-Based Diete. Open Access J. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 14, 027–034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Biase, S.G.; Fernandes, S.F.C.; Gianini, R.J.; Duarte, J.L.G. Vegetarian Diet and Cholesterol and Triglycerides Levels. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2007, 88, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banaszak, M.; Górna, I.; Przysławski, J. Non-Pharmacological Treatments for Insulin Resistance: Effective Intervention of Plant-Based Diets—A Critical Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, N.D.; Goldman, D.M.; Loomis, J.F.; Kahleova, H.; Levin, S.M.; Neabore, S.; Batts, T.C. Plant-Based Diets for Cardiovascular Safety and Performance in Endurance Sports. Nutrients 2019, 11, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, N.D.; Alwarith, J.; Rembert, E.; Brandon, L.; Nguyen, M.; Goergen, A.; Horne, T.; do Nascimento, G.F.; Lakkadi, K.; Tura, A.; et al. A Mediterranean Diet and Low-Fat Vegan Diet to Improve Body Weight and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Randomized, Cross-over Trial. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020, 41, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.Y.; Allen, K.; McDonnough, M.; Massera, D.; Ostfeld, R.J. A Plant-Based Diet and Heart Failure: Case Report and Literature Review. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuwamanya, S.; Lea, A.; Abraham, P.; Varghese, R.; Kendall, J. In Patients with Type II Diabetes, is a Vegan Diet Associated with Better Glycemic Control Compared with a Conventional Diabetes Diet? Evid. Based Pract. 2022, 25, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remde, A.; DeTurk, S.N.; Almardini, A.; Steiner, L.; Wojda, T. Plant-predominant eating patterns—How effective are they for treating obesity and related cardiometabolic health outcomes?—A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 80, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, B.J.; Anousheh, R.; Fan, J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian Diets and Blood Pressure among White Subjects: Results from the Adventist Health Study-2 (AHS-2). Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.; Gaskin, E.; Ji, C.; Miller, M.A.; Cappuccio, F.P. The Effect of Plant-Based Dietary Patterns on Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review Andmeta-Analysis of Controlled Intervention Trials. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termannsen, A.D.; Clemmensen, K.K.B.; Thomsen, J.M.; Nørgaard, O.; Díaz, L.J.; Torekov, S.S.; Quist, J.S.; Færch, K. Effects of Vegan Diets on Cardiometabolic Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, P.D.; Cativo, E.H.; Atlas, S.A.; Rosendorff, C. The Effect of Vegan Diets on Blood Pressure in Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 875–883.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Halloran, A.; Rippin, H.L.; Oikonomidou, A.C.; Dardavesis, T.I.; Williams, J.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Breda, J.; Chourdakis, M. Intake and Adequacy of the Vegan Diet. A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3503–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahleova, H.; Tura, A.; Hill, M.; Holubkov, R.; Barnard, N.D. A Plant-Based Dietary Intervention Improves Beta-Cell Function and Insulin Resistance in Overweight Adults: A 16-Week Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.C.; Gerhardt, T.E.; Kwon, E. Risk Factors For Coronary Artery Disease; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 1–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).