Abstract

Considering the rapid increase in the population over the age of 65, there is increasing need to consider models of care for persons with dementia (PWD). One common deficit associated with dementia progression is difficulty with successful participation in mealtimes. Difficulty participating in mealtimes in PWD is not the result of one factor, but rather a confluence of biological, psychological, and social characteristics common in dementia. Factors leading to mealtime difficulties for PWD may include changes in cognitive status, altered sensorimotor functioning, and increased reliance on caregiver support. The complex nature of biological, psychological, and social factors leading to mealtime difficulty highlights the need for a pragmatic model that caregivers can utilize to successfully support PWD during mealtimes. Existing models of dementia and mealtime management were reviewed and collated to create a model of mealtime management that considers this complex interplay. The Biopsychosocial Model of Mealtime Management builds on past research around patient-centered care and introduces an asset-based approach to capitalize on a PWD’s retained capabilities as opposed to compensating for disabilities associated with dementia. We hope this model will provide a framework for caregivers to understand what factors impact mealtime participation in PWD and provide appropriate means on intervention.

1. Introduction

In 2017, 15.6% of the American population was 65 years or older, representing more than 1:7 Americans [1]. By the year 2060, the number of individuals in America over the age of 65 is expected to double [2]. An increasingly aging population generally reflects positive developments in healthcare leading to increased life-expectancy; however, this is accompanied by inevitable increases in biological and neurological decline seen in aging bodies. The natural degenerative aging process is the largest contributing factor to the development of non-communicable diseases [3].

Dementia, one of the most prevalent non-communicable diseases, is a term used to describe a cluster of symptoms that results from various neurodegenerative diseases. There are over 100 types of dementia, most commonly presenting as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and Frontotemporal dementia [4]. Worldwide, the number of persons with dementia (PWD) is estimated to be 47 million, a number expected to increase to 131 million by the year 2050 [5]. Cognitive decline is not the only symptom associated with a dementia diagnosis; behavioral and psychiatric symptoms (BPSD) oftentimes fall into the cluster of symptoms that hallmark the neurodegenerative disorder [6]. Thus, in order to maximize health and quality of life within this growing population, it may be crucial to consider both the biological as well as the psychosocial deficits when implementing a holistic approach to management of dementia.

One primary area of management in dementia care relates to nutritional intake, which is often complicated by the presence of oropharyngeal dysphagia (OD). The prevalence of OD varies greatly across settings, but up to 70% of all referrals for dysphagia assessment are for older adults [7]. OD is commonly seen in PWD, with 57–93% experiencing swallowing-related deficits [8,9]. Given the number of individuals expected to develop dementia, these statistics represent a potential 26.8 million individuals with dementia who will experience some degree of swallowing-related deficit. Yet, despite the high potential of OD in PWD, a consensus on the functional impact of swallowing-related deficits in this population is lacking.

OD among PWD likely results from many different factors that accompany the biological, cognitive, and psychosocial decline during the disease’s progression. OD results from disturbances in motor control, changes in cognition, and/or sensory issues, all of which are common in individuals with progressive neurological diseases [10]. The physiological causes of OD in PWD are varied, but likely related to age-related decline in motor and sensory functioning that is exacerbated by the progressive neurological decline characteristic of dementia [11]. Unfortunately, the consequences of OD can be severe. Even in otherwise healthy older adults, aging cognitive and neuromuscular processes increase the risk for malnutrition and the development of aspiration pneumonia, which puts these individuals at higher risk of mortality [12,13]. In addition to the physiological effects of dysphagia, including malnutrition, weight loss, and dehydration, OD can impact psychosocial domains, resulting in reduced social participation and quality of life (QoL) [12,14,15,16]. PWD, in particular, face a wide range of symptomology congruent with the deleterious effects of OD, including reduced sensory and motor function resulting in altered feeding ability [8,10], which may further reduce social participation and quality of life in PWD.

2. Current Models That Can Inform Mealtime Management

Prior to considering plans for mealtime management in PWD, it is crucial to consider what is known about mealtime management in both clinical and non-clinical populations. A number of current theoretical models of mealtime management exist that can help inform a new conceptualization of mealtime management of PWD. Three models will be discussed below, The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Function, Disability, and Health, Bisogni et al.’s Framework of Typical Mealtime Processes, and historical perspectives on the Biopsychosocial Model of Patient care. Each model presents with both strengths and limitations when considering successful mealtime management for PWD, as will be described further below. Building on the unique strengths of each, these three theoretical models were all used to inform the Biopsychosocial Model of Mealtime Management in PWD proposed here.

2.1. World Health Organization’s International Classification of Function, Disability, and Health

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Function, Disability, and Health (WHO-ICF) offers a conceptual model for describing an individual’s functional status within the context of disease or disorder [17]. Approved by all member states of the World Health Organization, the WHO-ICF model is one of the most widely accepted models for classification of disfunction within the context of health. The health condition (a disease or disorder) may impact functioning at three mutually interacting levels: in relation to the body, activity, and participatory capability within the context of an individual’s environmental and personal factors [17]. Significantly, the model explicitly recognizes, and draws attention to, the important role of contextual factors on functional outcomes given the presence of disease.

As applied to mealtimes in dementia, the relationship between dementia (disease) and the eating process (activity) is multifaceted. Successful or unsuccessful mealtimes cannot be attributed to any one factor and, as the WHO-ICF model stipulates, multiple contextual factors, such as reliance on others for feeding assistance and altered cognitive functioning, affect the functional outcome. However, it must be recognized that this model of classification is born out of the identification of disability within the context of the person’s diagnosis and environment as opposed to an individual’s preserved abilities. The 2013 WHO Practical Manual for using the ICF framework mentions the word “disability” 270 times, and mentions the word “enable” in the context of human performance twice; the word “ability” is mentioned in the same context just once [18]. This deficit-based terminology may contribute to furthered disease-based treatment approaches that respond to a patient’s disfunction as opposed to a patient-centered approach which leverages the patient’s retained abilities for mealtime success. Combining the WHO-ICF, which highlights the important interconnected nature of disease, function, and environment, with a more asset-based approach to dementia management, which aims to leverage those retained abilities, may better encourage patient-centered care that frames PWD and caregivers as co-producers of positive health outcomes [19].

2.2. Bisogni et al.’s Framework of Typical Mealtime Processes

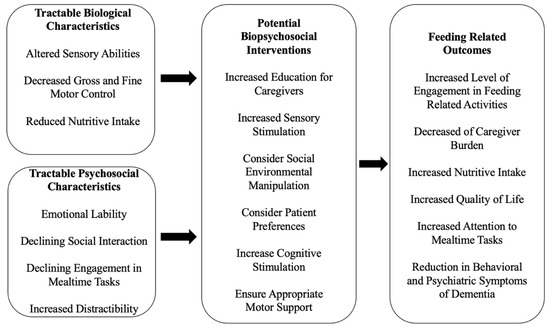

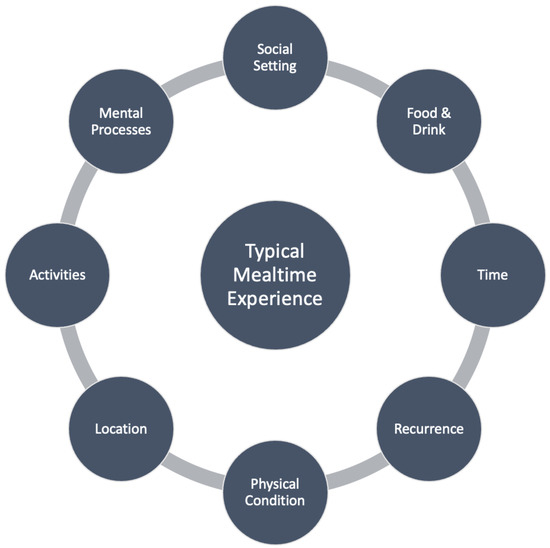

Moving toward a more asset-based approach to mealtime management for PWD requires a clear understanding of the environmental factors related to mealtimes. A 2007 review of eating habits in healthy adults revealed an intricate series of interconnected dimensions that form a framework to describe the typical mealtime process [20]. These dimensions include social setting, food and drink, time, recurrence, physical condition, location, activities, and mental processes (see Figure 1). Social setting describes the people present and their relationship to the participant. The food and drink domain details the type of material consumed, amount consumed, and how the food or drink was prepared (e.g., homemade or pre-prepared). The dimension of time is described as the time of day the meal was consumed, the chronological relation to other daily experiences (e.g., after exercise or before work), and the subjective experience of time (e.g., participants reported “I was in a rush”). The domain of recurrence was used to describe how repetitious the mealtime experience was (e.g., a meal eaten once a week versus once a year on special occasions). Physical condition refers to two main components, the appetite and hydration needs of the participant and the physical state of the participant such as presence of fatigue, illness, or disease. The location domain describes both the general location (e.g., at home vs. at a restaurant) as well as positionality within that location (e.g., at the dining room table versus in front of the television). Activities include anything that was happening during the mealtime (e.g., parental tasks) and how disruptive they were to the mealtime experience. Lastly, the mental processes domain includes two main features, food-related goals (e.g., eating so the food does not go bad) and associated emotions (e.g., stressed versus at ease).

Figure 1.

The eight interacting dimensions and features of eating and drinking episodes that characterize situational food and beverage consumption among working adults (based on [20]).

Within Bisogni et al.’s (2007) conceptual model, these dimensions come together to characterize a mealtime episode with each dimension describing a particular aspect of the mealtime. For example, mapping a typical dinnertime using this framework may include location (at home), people (with family), and time (after work and picking up children); each of these aspects color the eating experience and converge to define its success or failure. Mapping the mealtime experience of a PWD in a long-term care (LTC) facility may include location (in an isolated room), social setting (alone, without peers), and mental processes (confusion, frustration). Each of these dimensions influences the others, and the interconnected nature of these dimensions affects the ultimate mealtime experience.

2.3. Historical Perspectives of the Biopsychosocial Model of Patient Care

Bisogni et al.’s (2007) description of the mealtime experience as a dynamic process of environmental–social–personal interactions supports a more holistic approach to patient care, which is often framed within a biopsychosocial model. The biopsychosocial model of patient care was introduced as an alternative to the biomedical model of illness classification [21]. Engel’s Biopsychosocial model argued that a patient’s biological, social, psychological, and behavioral domains must be considered together in order to fully understand a patient’s diagnosis and prognosis [21]. Adaptation of the biopsychosocial model to describe dementia was first by described by Cohen-Mansfield, who proposed that the manifestation of dementia is the result of the convergence of biological, psychological, and environmental factors [22].

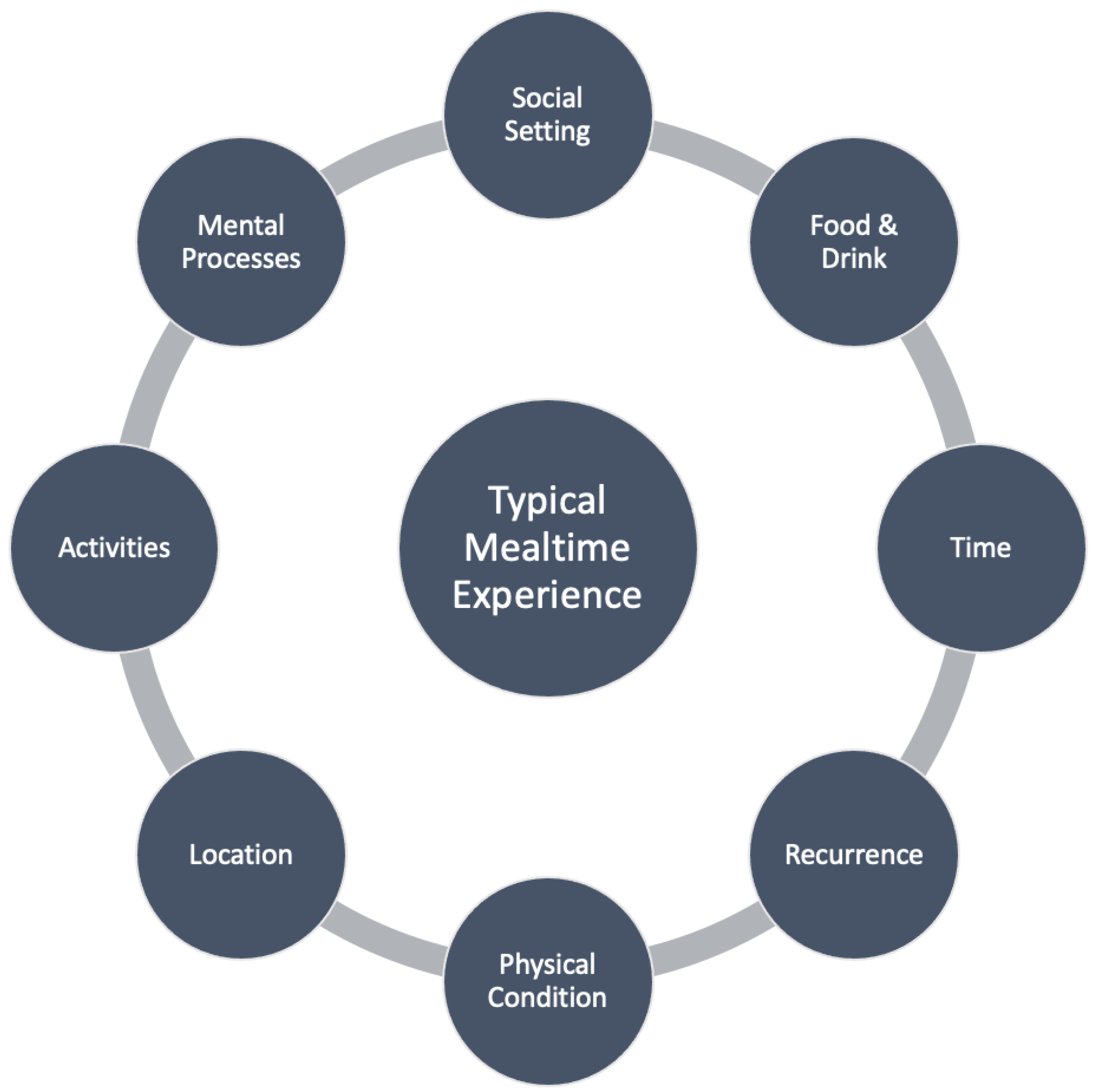

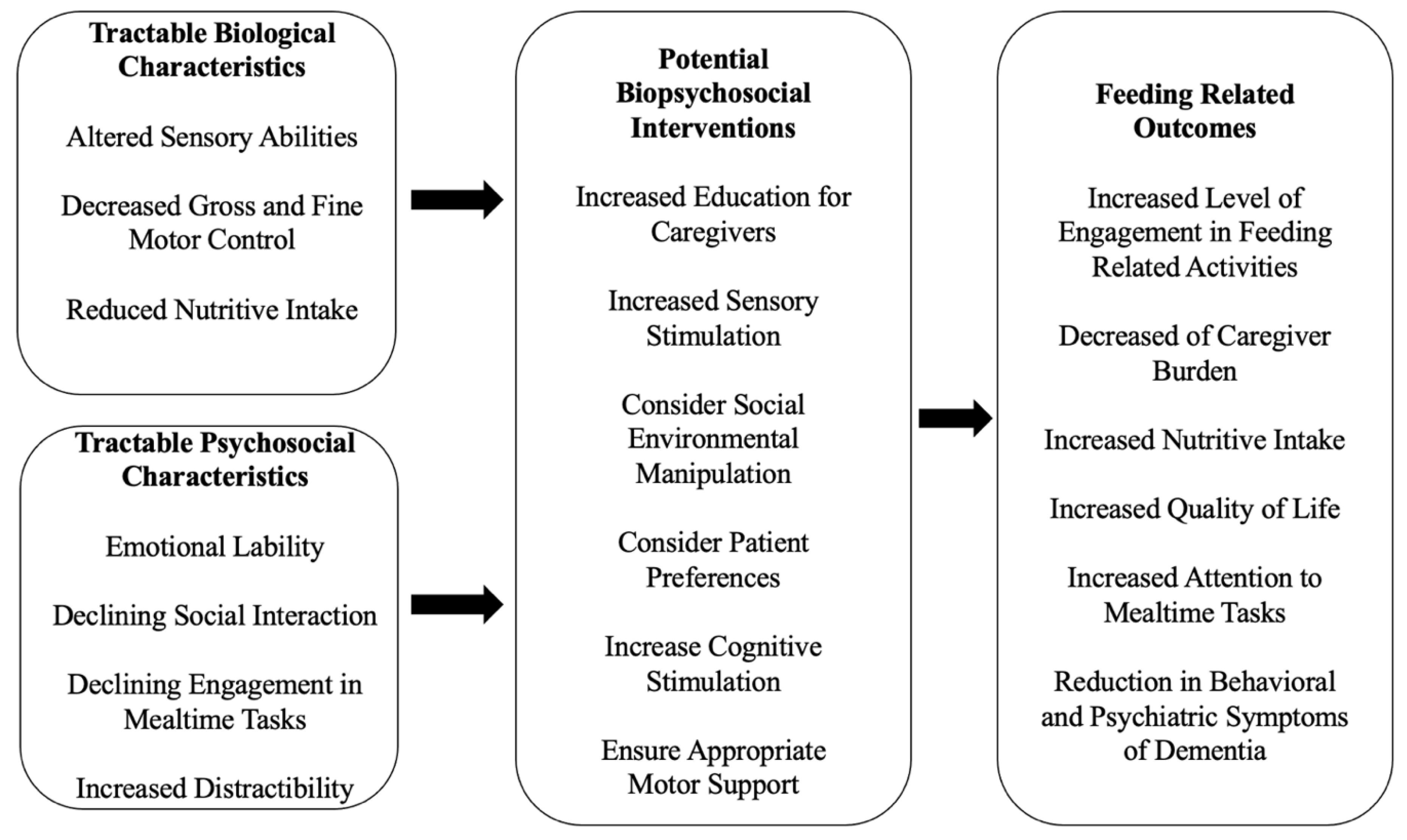

Considering the progressive nature of dementia, Spector and Orrell (2010) expanded on Cohen-Mansfield’s (2000) model by proposing that the impact of biological, psychological, social, and environmental domains change throughout disease progression [23]. In addition to highlighting the progressive nature of dementia-related symptomatology, the Spector-Orrell model identifies fixed and tractable biopsychosocial characteristics that a PWD experiences. Fixed characteristics are those that are not able to be altered. For example, fixed biological characteristics may be diagnosis or past medical history and fixed psychosocial characteristics may be personality traits or previous life events. Tractable characteristics are those that can be changed. For example, a tractable biological characteristic may be sensory impairment, and a tractable psychosocial characteristic may be environment or levels of mental stimulation. Identification of tractable biological and psychosocial characteristics may allow caregivers to better highlight modifiable personal and contextual factors that impact functional outcomes and leverage the PWD’s retained assets to enhance mealtime participation.

Patient-centered treatment requires consideration of both tractable biological and psychosocial characteristics when managing feeding and swallowing impairments in PWD to ensure that the mealtime is as successful as possible. Central to a biopsychosocial approach is patient-centered, as opposed to, disease-centered care. For example, consider a patient with dementia in an isolated room who is exhibiting heightened levels of agitation. As they throw their lunch tray off the table, is this truly an example of BPSD? Or perhaps the patient is full, and the caregiver did not recognize cues to stop feeding? The caregiver’s response to this behavior may depend on the caregiver’s view of the behavior [24]. Coming from a disease-based perspective, the caregiver may view these behaviors as a result of the neurodegenerative disease process and disregard this attempted communication, potentially resulting in increased frustration for both the caregiver and the PWD [25]. Alternatively, by utilizing a person-centered approach, the caregiver can better recognize this behavior as a reaction to the interplay between biological, social, and environmental factors resulting in an attempt to communicate an unmet need [20,26]. By utilizing a person-centered perspective, the PWD’s needs may be better met, thereby alleviating further frustration for both the PWD and the caregiver. It is crucial for caregivers to look at how these individuals are attempting communication, both with verbal cues and non-verbal behavior. To view the patient and their retained abilities holistically, clinicians must consider how PWD are framed within the context of a degenerative disease. By combining aspects of the three theoretical models described above (WHO-ICF, Bisogni’s conceptual model of mealtime management, and the tractable characteristics of the Spector-Orrell model biopsychosocial model of dementia management) caregivers can utilize a person-centered biopsychosocial model of mealtime management for PWD that views patients’ actions as a result of not only the disease, but also the social and environmental processes.

4. Discussion

Successfully assisted mealtimes are a critical component of caring for PWD as mealtimes have large impacts on QoL, maintenance of nutrition, feelings of autonomy, and socialization [12,15,16,73,84,85,86]. Additionally, considerations for mealtime management must reflect the dynamic relationship between the biological and psychosocial characteristics that impact the ability of PWD to participate in mealtimes. Biopsychosocial interventions that utilize an asset-based approach to mealtime management have been shown to increase nutritive intake, increase QoL, and decrease BPSD in PWD [44,45,56,67,75,83].

The Biopsychosocial Model of Mealtime Management proposed here may be a crucial component in designing person-centered mealtime interventions. However, in order to create meaningful, functional treatment options for PWD, future research in the area of dietary management must consider the perspectives of PWD. While it is understood that a progressive neurological disease will change the way an individual communicates, research has shown that PWD retain the ability to communicate their choices and opinions regarding mealtime management [85]. Unfortunately, however, many PWD report feelings of loss of agency and control when they are not provided opportunities to make choices [85]. Given the importance that recognition of choice and preference has on mealtime participation and maintenance of nutrition [67,83], it is crucial that future research surrounding mealtime management considers the perspectives of PWD. The capacity for an individual with decreased cognitive ability to participate in research may be difficult to ascertain, often resulting in clinical practices that position the PWD as a passive participant of intervention [87,88]. This “default view” needs to be re-examined. Future research must challenge this deficit-based perspective to identify areas where PWD can be integrated into research and clinical practice to better understand where mealtimes can be enhanced. The first step to ensuring truly person-centered care is to consider the perspective of, and minimize compromises to, the dignity of PWD [88]. Utilization of an asset-based biopsychosocial framework may guide the caregiver’s perspective away from an orientation that highlights areas of breakdown in mealtime and instead asks the caregiver to consider capitalizing on retained assets to promote successful mealtimes.

Mealtime management is a crucial component in considering care for PWD. The multifaceted nature of the mealtime experience for PWD, including increased reliance on caregivers, decreased opportunities for socialization, and changes in sensorimotor function, highlight the need for a dynamic approach to mealtime care. Moreover, the interconnected features of eating and drinking episodes suggest that single-component interventions, such as increasing the contrast of food or playing calming music, may not be enough to fully support PWD during mealtimes. Rather, as we propose here, successful mealtimes may be reliant on the consideration and explicit targeting of sensorimotor functioning, dining environment, cognitive status, and preferences of PWD as integral parts of mealtime management. PWD should remain active participants in their care. Utilizing an asset-based biopsychosocial model of mealtime management, that requires centering on the unique strengths and capabilities of each PWD, yields the potential to improve a broad range of mealtime outcomes more effectively, including mealtime engagement, autonomy, and nutrition maintenance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.F.B. and S.E.S.; methodology, D.F.B. and S.E.S.; formal analysis, D.F.B. and S.E.S.; investigation, D.F.B. and S.E.S.; resources, D.F.B. and S.E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.F.B. and S.E.S.; writing—review and editing, D.F.B. and S.E.S.; supervision, S.E.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Administration of Community Living. 2019 Profile of Older Americans; Administration of Community Living: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- U. C. Bureau. “2012 National Population Projections Table: Table 2. Projections of the Population by Selected Age Groups and Sex for the United States: 2015 to 2060,” Washington D.C.; 2012. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2012/demo/popproj/2012-summary-tables.html (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Jin, K.; Simpkins, J.W.; Ji, X.; Leis, M.; Stambler, I. The Critical Need to Promote Research of Aging and Aging-related Diseases to Improve Health and Longevity of the Elderly Population. Aging Dis. 2015, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2014 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014, 10, e47–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.; Comas-Herrera, A.; Knapp, M.; Guerchet, M.; Karagiannidou, M. World Alzheimer Report 2016: Improving Healthcare for People Living with Dementia: Coverage, Quality and Costs Now and in the Future. 2016. Available online: http://www.alz.co.uk/ (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Ismail, Z.; Smith, E.E.; Geda, Y.; Sultzer, D.; Brodaty, H.; Smith, G.; Agüera-Ortiz, L.; Sweet, R.; Miller, D.; Lyketsos, C.G.; et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: Provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioral impairment. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015, 12, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, S.B.; Suiter, D.M. An Epidemiologic Study on Aging and Dysphagia in the Acute Care Hospitalized Population: 2000–2007. Gerontology 2009, 55, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagiakrishnan, K.; Bhanji, R.A.; Kurian, M. Evaluation and management of oropharyngeal dysphagia in different types of dementia: A systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 56, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Val, M.C.; Martín-Martínez, A.; Graupera, M.; Arias, O.; Elvira, A.; Cabré, M.; Palomera, E.; Bolívar-Prados, M.; Clavé, P.; Ortega, O. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Complications of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Older Patients with Dementia. Nutrients 2020, 12, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, G.N.; O’Rourke, F.; Ong, B.S.; Cordato, D.J.; Chan, D.K.Y. Dysphagia: Causes, assessment, treatment, and management. Geriatrics 2008, 63, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Easterling, C.S.; Robbins, E. Dementia and Dysphagia. Geriatr. Nurs. 2008, 29, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namasivayam, A.M.; Steele, C.M. Malnutrition and Dysphagia in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebihara, S.; Sekiya, H.; Miyagi, M.; Ebihara, T.; Okazaki, T. Dysphagia, dystussia, and aspiration pneumonia in elderly people. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-H.; Golub, J.S.; Hapner, E.; Johns, M.M. Prevalence of Perceived Dysphagia and Quality-of-Life Impairment in a Geriatric Population. Dysphagia 2009, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.; Speyer, R.; Kertscher, B.; Denman, D.; Swan, K.; Cordier, R. Health-Related Quality of Life and Oropharyngeal Dysphagia: A Systematic Review. Dysphagia 2018, 33, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plowman-Prine, E.K.; Sapienza, C.M.; Okun, M.; Bs, S.L.P.; Jacobson, C.; Wu, S.S.; Rosenbek, J.C. The relationship between quality of life and swallowing in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 1352–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostanjsek, N. Use of The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a conceptual framework and common language for disability statistics and health information systems. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. How to use the ICF A Practical Manual for Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Exposure Draft for Comment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerlanad, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, T.; Rippon, S.; Tait, M. Head, Hands and Heart: Asset-Based Approaches in Health Care A Review of the Conceptual Evidence and Case Studies of Asset-Based Approaches in Health, Care and Wellbeing, London. 2015. Available online: www.alignedconsultancy.co.uk (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Bisogni, C.A.; Falk, L.W.; Madore, E.; Blake, C.E.; Jastran, M.; Sobal, J.; Devine, C.M. Dimensions of everyday eating and drinking episodes. Appetite 2007, 48, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G. The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J. Heterogeneity in Dementia: Challenges and Opportunities: Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2000, 14, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spector, A.; Orrell, M. Using a biopsychosocial model of dementia as a tool to guide clinical practice. Int. Psychogeriatrics 2010, 22, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitlin, L.N.; Piersol, C.; Hodgson, N.; Marx, K.; Roth, D.L.; Johnston, D.; Samus, Q.; Pizzi, L.; Jutkowitz, E.; Lyketsos, C.G. Reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with dementia and associated burden in family caregivers using tailored activities: Design and methods of a randomized clinical trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2016, 49, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duxbury, J.; Pulsford, D.; Hadi, M.; Sykes, S. Staff and relatives’ perspectives on the aggressive behaviour of older people with dementia in residential care: A qualitative study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 20, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitwood, T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Aliev, G.; Ashraf, G.; Kaminsky, Y.G.; Sheikh, I.A.; Sudakov, S.; Yakhno, N.; Benberin, V.V.; Bachurin, S.O. Implication of the Nutritional and Nonnutritional Factors in the Context of Preservation of Cognitive Performance in Patients with Dementia/Depression and Alzheimer Disease. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2013, 28, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paula, J.J.; Albuquerque, M.R.; Lage, G.M.; Bicalho, M.A.; Romano-Silva, M.A.; Malloy-Diniz, L.F. Impairment of fine motor dexterity in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease dementia: Association with activities of daily living. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2016, 38, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drenth, H.; Zuidema, S.; Bautmans, I.; Marinelli, L.; Kleiner, G.; Hobbelen, H. Paratonia in Dementia: A Systematic Review. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 78, 1615–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautmans, I.; Demarteau, J.; Cruts, B.; Lemper, J.-C.; Mets, T. Dysphagia in elderly nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment: Feasibility and effects of cervical spine mobilization. J. Rehabil. Med. 2008, 40, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taragano, F.E.; Allegri, R.F.; Krupitzki, H.; Sarasola, D.R.; Serrano, C.M.; Loñ, L.; Lyketsos, C.G. Mild Behavioral Impairment and Risk of Dementia: A Prospective Cohort Study of 358 Patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2009, 70, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, H.E.; Fries, B.E.; Verbrugge, L.M. Windows to Their World: The Effect of Sensory Impairments on Social Engagement and Activity Time in Nursing Home Residents. J. Gerontol. Soc. Sci. 1997, 52, 35–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanowski, A.; Litaker, M. Social Interaction, Premorbid Personality, and Agitation in Nursing Home Residents with Dementia. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2006, 20, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Boltz, M.; Lee, H.; Algase, D.L. Does Social Interaction Matter Psychological Well-Being in Persons with Dementia? Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2017, 32, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Dakheel-Ali, M.; Marx, M.S. Engagement in Persons with Dementia: The Concept and Its Measurement. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 17, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.H.; Martin, L.S.; Dupuis, S.; Reimer, H.; Genoe, R. Strategies to support engagement and continuity of activity during mealtimes for families living with dementia; a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Perkhounkova, E.; Williams, K.; Batchelor, M.; Hein, M. Food intake is associated with verbal interactions between nursing home staff and residents with dementia: A secondary analysis of videotaped observations. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 109, 103654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, L.L.; van Harten, A.C.; Pijnenburg, Y.A.L.; Koedam, E.L.G.E.; Bouwman, F.H.; Sistermans, N.; Reuling, I.E.W.; Prins, N.D.; Lemstra, A.W.; Scheltens, P.; et al. Trajectories of cognitive decline in different types of dementia. Psychol. Med. 2014, 45, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nell, D.; Neville, S.; Bellew, R.; O’Leary, C.; Beck, K.L. Factors affecting optimal nutrition and hydration for people living in specialised dementia care units: A qualitative study of staff caregivers’ perceptions. Australas. J. Ageing 2016, 35, E1–E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.G.; Rose, K.M.; Taylor, A.G. A descriptive study of the nutrition-related concerns of caregivers of persons with Dementia. J. Aging Res. Lifestyle 2016, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salva, A.; Andrieu, S.; Fernandez, E.; Schiffrin, E.J.; Moulin, J.; Decarli, B.; Rojano-i-Luque, X.; Guigoz, Y.; Vellas, B.; The Nutrialz Group. Health and nutrition promotion program for patients with dementia (NutriAlz): Cluster randomized trial. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2011, 15, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staedtler, A.V.; Nunez, D. Nonpharmacological Therapy for the Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease: Linking Evidence to Practice. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2015, 12, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, C.E.; Ismail, Z.; A Schweizer, T. Impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on caregiver burden in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2012, 2, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, K.A.; Creery, J.; Florczak, S.M.; Weintraub, S.; Mesulam, M.-M.; Reber, P.J.; Kiragu, J.; Rooks, J.; Safron, A.; Morhardt, D.; et al. Benefits of Mindfulness Training for Patients with Progressive Cognitive Decline and Their Caregivers. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2015, 30, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.; Hickson, M.; Frost, G. Eating together is important: Using a dining room in an acute elderly medical ward increases energy intake. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2006, 19, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batchelor-Murphy, M.A.P.F. Supportive handfeeding in dementia: Establishing evidence for three handfeeding techniques. In Proceedings of the Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing 27th International Research Congress, Cape Town, South Africa, 24 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor-Murphy, M.K.; McConnell, E.S.; Amella, E.J.; Anderson, R.A.; Bales, C.W.; Silva, S.; Barnes, A.; Beck, C.; Colon-Emeric, C.S. Experimental Comparison of Efficacy for Three Handfeeding Techniques in Dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, e89–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D.M.; Sparrow, B.; Winerman, L. Vicarious Agency: Experiencing Control Over the Movements of Others. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks-Moore, S.L. Relaxing Music at Mealtime in Nursing Homes. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2005, 31, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.W.; Smith, M. The Effect of Music on Caloric Consumption Among Nursing Home Residents with Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type. Act. Adapt. Aging 2009, 33, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, N.; Beck, A.M. The Influence of Aquariums on Weight in Individuals with Dementia. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2013, 27, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, T.E.; Neargarder, S.A.; Cipolloni, P.; Cronin-Golomb, A. Visual contrast enhances food and liquid intake in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 23, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulmont-Rossé, C.; Gaillet, M.; Raclot, C.; Duclos, M.; Servelle, M.; Chambaron, S. Impact of Olfactory Priming on Food Intake in an Alzheimer’s Disease Unit. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 66, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Jao, Y.; Williams, K. Factors influencing the pace of food intake for nursing home residents with dementia: Resident characteristics, staff mealtime assistance and environmental stimulation. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curle, L.; Keller, H. Resident interactions at mealtime: An exploratory study. Eur. J. Ageing 2010, 7, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick, R.; Lin, T.-F.; Shune, S.E. Visual Modeling: A Socialization-Based Intervention to Improve Nutritional Intake Among Nursing Home Residents. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2021, 30, 2202–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, K.A.N.D.; De Graaf, C.; Kok, F.J.; Van Staveren, W.A. Effect of family style mealtimes on quality of life, physical performance, and body weight of nursing home residents: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2006, 332, 1180–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HReimer, H.D.; Keller, H.H. Mealtimes in Nursing Homes: Striving for Person-Centered Care. J. Nutr. Elder. 2009, 28, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shune, S.E.; Linville, D. Understanding the dining experience of individuals with dysphagia living in care facilities: A grounded theory analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 92, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A. The Logic of Care: Health and the Problem of Patient Choice, 1st ed.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shune, S.; Barewal, R. Redefining the value of snacks for nursing home residents: Bridging psychosocial and nutritional needs. Geriatr. Nurs. 2022, 44, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, J.A.; Camp, C.J. Using Spaced Retrieval as an Intervention During Speech-Language Therapy. Clin. Gerontol. 1998, 19, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-C.; Huang, Y.-J.; Su, S.-G.; Watson, R.; Tsai, B.W.J.; Wu, S.-C. Using spaced retrieval and Montessori-based activities in improving eating ability for residents with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgeois, M.S.; Camp, C.; Rose, M.; White, B.; Malone, M.; Carr, J.; Rovine, M. A comparison of training strategies to enhance use of external aids by persons with dementia. J. Commun. Disord. 2003, 36, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, S.; Zizzo, G.; Robertson, J.; Goodwin-Smith, I. Positive Interactive Engagement (PIE): A pilot qualitative case study evaluation of a person-centred dementia care programme based on Montessori principles. Dementia 2018, 19, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.-C.; Huang, Y.-J.; Watson, R.; Wu, S.-C.; Lee, Y.-C. Using a Montessori method to increase eating ability for institutionalised residents with dementia: A crossover design. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 3092–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartwright, J.; Roberts, K.; Oliver, E.; Bennett, M.; Whitworth, A. Montessori mealtimes for dementia: A pathway to person-centred care. Dementia 2022, 21, 1098–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, E.; Stott, J.; Charlesworth, G.; Noone, D.; Payne, J.; Patel, M.; Spector, A. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) programme for depression in people with early stages of dementia: Study protocol for a randomised controlled feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2017, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rogus-Pulia, N.; Malandraki, G.A.; Johnson, S.; Robbins, J. Understanding Dysphagia in Dementia: The Present and the Future. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation Rep. 2015, 3, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherder, E.; Dekker, W.; Eggermont, L. Higher-Level Hand Motor Function in Aging and (Preclinical) Dementia: Its Relationship with (Instrumental) Activities of Daily Life —A Mini-Review. Gerontology 2008, 54, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mse, V.K.R.; Siemionow, V.; Sahgal, V.; Yue, G.H. Effects of Aging on Hand Function. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, E.; Patish, H.; Coleman, R. The Aging Hand. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2003, 58, M146–M152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Roberts, B.L. Feeding difficulty in older adults with dementia. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 2266–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, M.B.; Nielson, K.A.; Beth, R.E.; Shankle, W.; Cotman, C. Acquisition and Long-Term Retention of a Fine Motor Skill in Alzheimers-Disease. Brain Cogn. 1995, 29, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, M.B.; Hsieh, S.; Bricker, J.; Dick-Muehlke, C. Facilitating acquisition and transfer of a continuous motor task in healthy older adults and patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology 2003, 17, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnaby, G.D.; Harenberg, L. What is ‘usual care’ in dysphagia rehabilitation: A survey of usa dysphagia practice patterns. Dysphagia 2013, 28, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sura, L.; Madhavan, A.; Carnaby, G.; Crary, M.A. Dysphagia in the elderly: Management and nutritional considerations. Clin. Interv. Aging 2012, 7, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.M.; Kjaersgaard, A.; Hansen, T.; Poulsen, I. Systematic review and evidence based recommendations on texture modified foods and thickened liquids for adults (above 17 years) with oropharyngeal dysphagia—An updated clinical guideline. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1980–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, D.; Barewal, R.; Shune, S.E. Sensory-Enhanced, Fortified Snacks for Improved Nutritional Intake Among Nursing Home Residents. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 41, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, L.C.; Ersek, M.; Gilliam, R.; Carey, T.S. Oral Feeding Options for People with Dementia: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristou, I.; Giatras, N.; Ussher, M. Impact of Dementia Progression on Food-Related Processes. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2013, 28, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, A.; Battjes-Fries, M.C.E.; van de Rest, O.; Patijn, O.N.; van der Lee, M.; Wijma-Idsinga, N.; Pot, G.K.; Voshol, P. Fingerfoods: A feasibility study to enhance fruit and vegetable consumption in Dutch patients with dementia in a nursing home. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyet, V.; Giboreau, A.; Benattar, L.; Cuvelier, G. Attractiveness and consumption of finger foods in elderly Alzheimer’s disease patients. Food Qual. Preference 2014, 34, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.L.; Teno, J.M.; Kiely, D.K.; Shaffer, M.L.; Jones, R.; Prigerson, H.G.; Volicer, L.; Givens, J.L.; Hamel, M.B. The Clinical Course of Advanced Dementia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1529–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milte, R.; Shulver, W.; Killington, M.; Bradley, C.; Miller, M.; Crotty, M. Struggling to maintain individuality—Describing the experience of food in nursing homes for people with dementia. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 72, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.; Byers, S.; Nay, R.; Koch, S. Guiding design of dementia friendly environments in residential care settings: Considering the living experiences. Dementia 2009, 8, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsawy, S.; Mansell, W.; McEvoy, P.; Tai, S. What is good communication for people living with dementia? A mixed-methods systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatrics 2017, 29, 1785–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, J.; Ryan, T.; Ingleton, C.; Clarke, A. ‘You have to be mindful of whose story it is’: The challenges of undertaking life story work with people with dementia and their family carers. Dementia 2013, 14, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).