Simple Summary

Antibiotic resistance in companion animals is becoming a serious public health concern. When bacteria develop resistance to multiple antibiotics, they can spread from animals to humans, making infections harder to treat. This study examined urine samples from companion animals hospitalized with urinary tract infections over two years. Three types of bacteria were most commonly found: Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Alarmingly, nearly three-quarters of these bacteria were resistant to multiple antibiotics, including some “last-resort” antibiotics called carbapenems. Additionally, one E. coli strain carried a dangerous resistance gene called blaNDM-1, which makes bacteria extremely difficult to treat. These findings highlight why veterinarians must use antibiotics carefully and why companion animal owners should follow treatment instructions accurately. The health of companion animals and human families is connected, as what affects one can affect the other. Better infection control in veterinary hospitals and smarter antibiotic use can help protect both animal and human health.

Abstract

Emerging antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in companion animals represents a global health concern as they serve as potential reservoirs for multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, which can be transmitted to humans. Herein, we provide comprehensive surveillance data on resistance patterns in veterinary hospital settings, focusing on urinary tract infection. A total of 23 bacterial strains were isolated from urine specimens of hospitalized companion animals suspected of urinary tract infections (UTIs) between 2022 and 2024. 16S rRNA sequencing analysis revealed that Escherichia coli (47.8%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (21.7%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8.7%) were predominant uropathogens. Minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration tests were employed to analyze AMR patterns across different classes of antibiotics. Moreover, antimicrobial susceptibility test exhibited 73.91% MDR according to the standard definition given by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M100 guidelines. Most Gram-negative bacteria have been shown to be resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics, especially carbapenems. Notably, an E. coli strain was confirmed to possess the blaNDM-1 gene encoding the carbapenemase New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase. These findings support the implementation of targeted infection control measures and evidence-based treatment protocols to preserve antimicrobial efficacy in companion animal medicine to minimize potential public health risks through the One Health approach.

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most urgent global threats to both human and veterinary public health. In 2021, bacterial AMR was associated with approximately 4.71 million deaths worldwide, of which 1.14 million were directly attributable to drug-resistant infections [1]. To counter this escalating challenge, the World Health Organization (WHO) updated the Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (BPPL) in 2024 to guide research prioritization, policy development, and the discovery of novel antimicrobials. Within this framework, third-generation cephalosporin-resistant (3GCRE) and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) were classified as “critical” priority pathogens due to their limited therapeutic options and significant threat to global health [2].

Growing evidence indicates that companion animals can serve as reservoirs and potential disseminators of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, posing risks of zoonotic transmission to humans. Frequently reported MDR species in companion animals include Escherichia coli (E. coli), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (S. pseudintermedius), Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae), and Acinetobacter baumannii [3,4,5,6,7]. Many of these belong to the ESKAPE group—pathogens renowned for their remarkable ability to evade antimicrobial action and acquire resistance through genetic mutations and mobile genetic elements, including plasmids, transposons, and integrons [8]. Such mechanisms enable the rapid spread of resistance traits across bacterial populations and host species.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common bacterial infections in companion animals, representing one of the leading indications for antimicrobial prescription in veterinary practice and accounting for approximately 12% of all antibiotic use in dogs [9,10]. Inappropriate or empirical antibiotic use can lead to therapeutic failure, resistance development, and increased public health risks [11]. Gram-negative bacteria dominate as the causative agents of canine and feline UTIs, with uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) being the most prevalent pathogen in both uncomplicated and complicated infections. Other frequently isolated uropathogens include K. pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis (P. mirabilis), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), and S. aureus [12,13].

Fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins remain among the most frequently prescribed antimicrobials for UTIs; however, their extensive use accelerates the selection and dissemination of resistant strains [12,14]. Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) and carbapenemase genes plays a central role in conferring resistance to β-lactams and other antimicrobial classes [15]. Although carbapenems are rarely used in veterinary settings, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales have been increasingly reported in companion animals [14]. According to the Ambler classification system, β-lactamases are categorized into classes A, B, and D. The carbapenemases KPC (class A) [16,17], NDM (class B) [16,18,19], and OXA-48-like (class D) [16,20,21] β-lactamases have been detected in animal isolates, raising new challenges for treatment, infection control, and interspecies transmission.

Close interactions between humans and companion animals facilitate the bidirectional transmission of bacteria. Such transmission can occur through both direct and indirect pathways. Direct transmission involves close physical contact, such as petting, kissing, or licking, whereas indirect transmission occurs via shared household environments or veterinary settings [5,6,22]. Previous studies have demonstrated the potential for bidirectional exchange of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria between humans and companion animals [3,23], underscoring the risk of zoonotic transmission associated with close human–animal contact. Therefore, continuous monitoring of AMR in companion animals, and human surveillance, is essential for an effective One Health approach, particularly within veterinary hospitals. Despite growing global attention to AMR in veterinary contexts, much of the existing research remains geographically limited, hindering a comprehensive understanding of resistance dynamics in companion animals.

In this study, bacterial isolates were obtained from urine specimens of hospitalized companion animals to characterize AMR patterns and assess the prevalence of resistant uropathogens. Understanding these AMR profiles is crucial for guiding evidence-based therapeutic decisions, supporting antimicrobial stewardship in veterinary medicine, underscoring the potential risk for zoonotic dissemination of resistant bacteria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Clinical Information

A total of 51 urinary specimens were collected between 2022 and 2024 from hospitalized companion dogs and cats at Chungnam National University Teaching Hospital in Daejeon, Republic of Korea. Urine samples were collected by cystocentesis from hospitalized dogs suspected of urinary tract infection, with careful attention to prevent cross-contamination. The samples were inoculated in LB broth (#244620; BD Difco™, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and then cultured aerobically at 37 °C overnight in a shaking incubator. From 51 specimens, 23 bacterial isolates were obtained and identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. All isolates were stored at −80 °C for future research. Each bacterial isolate was assigned a unique code consisting of the institutional abbreviation, Chungnam National University Teaching Hospital, the bacterial species name, and a sequential isolation number.

2.2. Identification of Bacterial Strains

Bacterial strains were identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing conducted by Macrogen sequencing facility (Macrogen Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea. Briefly, bacterial colonies were obtained from agar plates, and their DNA was extracted by the boiling method for analysis. PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene was performed using primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) [24]. Approximately 1400 base pairs of the amplified products were analyzed using the NCBI Nucleotide BLAST database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/, accessed on 7 January 2026) to determine bacterial species.

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

The Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method was used to determine the antibiotic susceptibility profile, employing Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA; MB-M1033; MBcell, Seoul, Republic of Korea). Discs of 29 different antibiotics (BD BBL™ Sensi-Disc™, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were used as follows: Amikacin (30 µg), Gentamicin (10 µg), Kanamycin (30 µg), Streptomycin (10 µg), Tobramycin (10 µg), Ampicillin (10 µg), Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid (20/10 µg), Ampicillin/Sulbactam (10/10 µg), Cefazolin (30 µg), Cefaclor (30 µg), Cefoxitin (30 µg), Cefuroxime (30 µg), Cefixime (5 µg), Cefotaxime (30 µg), Ceftazidime (30 µg), Ceftriaxone (30 µg), Cefepime (30 µg); Ertapenem (10 µg), Imipenem (10 µg), Meropenem (10 µg), Aztreonam (30 µg), Chloramphenicol (30 µg), Ciprofloxacin (5 µg), Nalidixic acid (30 µg), Colistin (10 µg), Doxycycline (30 µg), Tetracycline (30 µg), Tigecycline (15 µg), Azithromycin (15 µg). Clinical isolates from animals were first inoculated in nutrient broth (NB; #234000; BD Difco™) and incubated overnight aerobically at 37 °C in a shaking incubator. The bacterial suspension was adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard, then diluted in 11 mL of Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB; MB-M1034; MBcell, Yongin-si, Republic of Korea) to reach approximately 1.0 × 105 CFU/mL. The appropriate volume of inoculum was swabbed evenly onto the surface of MHA plates, following the CLSI guidelines [25]. Antibiotic discs were placed on the inoculated plates, which were then incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. Zones of inhibition were measured with a ruler or calipers, and susceptibility interpretations (resistant, intermediate, or susceptible) were made according to CLSI M100 breakpoint criteria. Isolates resistant to at least one agent in three or more antibiotic classes were classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR), based on criteria proposed by GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators [1].

2.4. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined using Sensititre™ Companion Animal Vet AST Plates (COMPGN1F; COMPGP1F; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, single colonies grown on agar were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the turbidity was adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard. This suspension was further diluted in 11 mL of MHB to achieve an approximate final concentration of 1.0 × 105 CFU/mL. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed against 19 antibiotics using a standardized dilution range as specified by the test plate. Plates were sealed with adhesive film and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. To determine the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC), 40 μL of broth from each well corresponding to the MIC value and the next higher concentration was inoculated onto MHA plates and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. The MBC was defined as the lowest concentration at which no visible bacterial growth was observed.

2.5. Polymerase Chain Reaction

Isolates exhibiting carbapenem resistance were subjected to PCR to detect the presence of the blaKPC, blaNDM-1, blaIMP, and blaVIM genes. Individual colonies from each plate were suspended in 100 μL of distilled water and boiled at 100 °C for 10 min to obtain each template DNA. PCR amplification was conducted using AccuPower™ PCR PreMix (K-2016; Bioneer, Daejeon, Republic of Korea). The 20 μL reaction mixture contained 10 ng of template DNA, 2 μL of forward primer (20 μM), 2 μL of reverse primer (20 μM), and 14 μL of RNase-free water. The thermal cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 45 s, annealing at 60 °C for 45 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min; with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were stained using RedSafe™ Nucleic Acid Staining Solution (#21141; iNtRON Biotechnology, Sungnam, Republic of Korea) and visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel under UV light. The specific primers of targeted genes are listed in Table S1 [26,27,28].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

There is no statistical analysis of data in this manuscript. But, the illustration was performed using GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Bacterial Strains in Urine Specimens

Among 51 urine samples collected from dogs and cats, 21 Gram-negative and 2 Gram-positive bacterial strains were isolated exclusively from dogs (Table 1). The species with the highest prevalence were E. coli (47.8%) and K. pneumoniae (21.7%), both of which are Gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, P. aeruginosa, P. mirabilis, Shigella flexneri (S. flexneri), and Enterobacter hormaechei (E. hormaechei), which are also Gram-negative bacteria, were also isolated. In contrast, S. pseudintermedius, the Gram-positive bacterium, was isolated from only two specimens (8.6%).

Table 1.

Pathogenic bacterial isolates and the corresponding origins of their isolation are summarized.

3.2. Characterization of the Antibiotic Resistance Profile of the Gram-Negative Strains

Among the Gram-negative bacterial isolates, the highest rates of antibiotic resistance were observed for ampicillin (92.3%) and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (89.5%). In contrast, all Gram-negative isolates were susceptible to amikacin (100%), while high susceptibility was also observed for gentamicin (90.5%), imipenem (95.2%), and colistin (90.0%) (Table S2).

E. coli isolates exhibited higher resistance to ceftazidime and ceftriaxone, whereas K. pneumoniae showed complete resistance (100%) to ampicillin/sulbactam, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, and doxycycline (Table 2). Notably, all Gram-negative isolates remained susceptible to colistin (90.0%).

Table 2.

Antibiotic resistance profiles for each isolated species.

Additionally, several Gram-negative strains exhibited resistance to carbapenem antibiotics, including ertapenem (10.5%), imipenem (4.8%), and meropenem (19.0%). The emergence of carbapenem-resistant enterobacterales (CRE) is of particular concern, as these bacteria can rapidly disseminate carbapenemase genes that confer broad resistance. Conversely, the two P. aeruginosa isolates demonstrated similar resistance patterns to most Gram-negative antibiotics, except for azithromycin. Antibiotics for which intrinsic resistance is well established were excluded from the analysis of resistance rate for the AMR disc diffusion and MIC results.

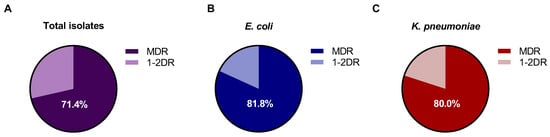

According to the definitions proposed, 71.43% of the 21 Gram-negative bacterial isolates were classified as MDR, with the remainder being 1–2 drug resistance (1-2DR) (Figure 1A). Notably, 81.81% of the 11 E. coli strains (Figure 1B) and 80% of the 5 K. pneumoniae strains (Figure 1C) were MDR. Most of the strains presented an MDR profile and did not show an extensive drug-resistance (XDR) profile.

Figure 1.

Proportion of MDR among Gram-negative isolates, E. coli; K. pneumoniae; P. aeruginosa; P. mirabilis; S. flexneri; and E. hormaechei. (A) Gram-negative isolates (n = 21); (B) E. coli isolates (n = 11); (C) K. pneumoniae isolates (n = 5).

3.3. Carbapenemase Gene-Harboring Isolates

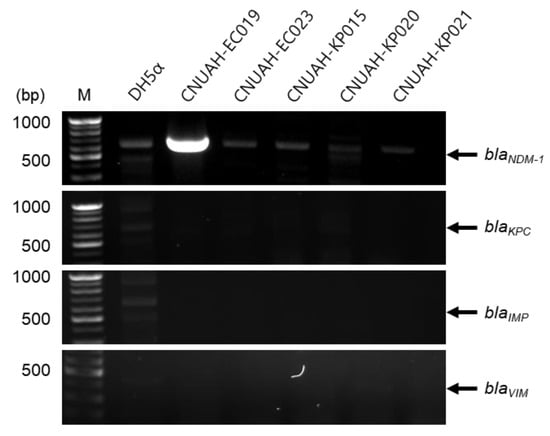

To investigate the presence of specific resistance genes, five clinical isolates initially identified as carbapenem-resistant by AMR disc diffusion testing were further analyzed using PCR (Figure 2). Unexpectedly, most isolates did not harbor known carbapenemase genes, including blaNDM-1, blaKPC, blaIMP, and blaVIM. However, isolate EC019 carried the blaNDM-1 gene and exhibited strong resistance to all three carbapenem antibiotics, ertapenem, imipenem, and meropenem (Figure 2 and Figures S1–S4). Although the blaNDM-1 gene is well known to be horizontally transmitted between germs via plasmids, recent studies have reported that it can also exist on the chromosome [29,30]. Since genomic DNA was extracted using a boiling method, it was not possible to determine whether blaNDM-1 gene is located on a plasmid or chromosome. Further experiments are needed to determine which of the plasmids or chromosomes harbors this gene.

Figure 2.

Detection and plasmid confirmation of the blaNDM-1 gene in carbapenem-resistant isolates by PCR. DNA templates from each isolate were amplified using specific primers by PCR. DH5α was used as a negative control. The expected amplicon sizes and primer sequences for each target gene are provided in Table S1.

In addition, to investigate the strain type and potential virulence of EC019, strains with high sequence similarity to EC019 based on 16S rRNA sequencing were analyzed. The results revealed that EC019 shares 99.72% sequence identity with previously reported Enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7 (GenBank accession: CP038319.1) or Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (GenBank accession: CP091018.1) according to NCBI BLAST analysis [31,32]. These findings speculate that EC019 is a highly virulent pathogen to humans and animals. However, further studies using WGS are required for in-depth analysis.

3.4. MIC and MBC of All Bacterial Strains

MIC or MBC of antibiotics against Gram-negative and Gram-positive isolates was presented in Table 3 or Table S3 and Table 4 or Table S4, respectively. Consistent with the AMR profiles obtained from the disc diffusion test, many isolates exhibited resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics. Notably, a high prevalence of resistance was observed against β-lactam antibiotics, including β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations and cephalosporins. Although fluoroquinolones were not included in the AMR disc test, MIC analysis revealed relatively high levels of resistance, with fewer than half of the isolates remaining susceptible. These findings collectively indicate that most isolates displayed broad-spectrum AMR.

Table 3.

MIC of antibiotics against Gram-negative isolates.

Table 4.

MIC of antibiotics against Gram-positive isolates.

Among the isolates, S. pseudintermedius strains were identified to show resistance to oxacillin. Specifically, isolate SI027 exhibited resistance in both the AMR disc diffusion and MIC tests based on the CLSI M100 breakpoint criteria. In contrast, isolate SI017 was resistant only in the disc diffusion test but not in the MIC test. Cefoxitin is typically used as a surrogate marker for detecting oxacillin resistance in Staphylococcus spp., and isolates demonstrating resistance to either cefoxitin or oxacillin are categorized as methicillin (oxacillin)-resistant. However, both isolates were susceptible to penicillinase-labile penicillins, such as ampicillin, suggesting that they may behave similarly to methicillin-susceptible staphylococci, which are generally susceptible to most β-lactam antibiotics, β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, and cephalosporins. Given these inconsistent results, further molecular analysis, including PCR detection of mecA and mecC genes, are warranted to confirm methicillin resistance.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that bacterial isolates obtained from companion animals with urinary tract infections exhibited diverse AMR profiles, with a substantial proportion meeting the criteria for MDR. These findings highlight not only the growing concern of MDR bacteria circulating among companion animals, which have been increasingly recognized as potential reservoirs, but also the importance of accurate diagnosis, continuous surveillance, and the implementation of effective control and prevention strategies, as essential factors to help mitigate the spread of AMR in both veterinary and public health sectors.

Such AMR poses serious challenges to both veterinary and human medicine, as pathogens exhibiting MDR are often associated with increased morbidity, prolonged hospitalization, treatment failure, and even mortality. The occurrence of MDR bacteria in animals was associated with the abuse of antibiotic prescriptions and antibiotic treatment [33,34,35]. Recently, there have been few antibiotic options for referral cases from primary animal hospitals. Indeed, AMR analysis exhibited MDR of more than 70% in all isolates, more than 80% in E. coli or K. pneumoniae.

Since intrinsic resistance is a species-specific characteristic shared by all or nearly all isolates and is independent of prior antimicrobial exposure (e.g., K. pneumoniae is intrinsically resistant to ampicillin) [36,37], antimicrobial agents to which a species is intrinsically resistant are considered clinically ineffective, even when in vitro susceptibility is observed. E. hormaechei demonstrates intrinsic resistance to multiple antibiotic classes through constitutive expression of chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase, conferring natural resistance to ampicillin, amoxicillin, and first-generation cephalosporins as determined by MIC analysis [38,39]. Similarly, consistent with our results, P. mirabilis exhibits substantial antibiotic resistance to approximately 50% of clinical isolates, complicating clinical therapeutic options [40]. Therefore, susceptible results for intrinsically resistant organisms should be interpreted with caution when considering prescription, as they may reflect errors in organism identification or susceptibility testing rather than true antimicrobial activity [36]. Accordingly, in this study, antibiotics for which intrinsic resistance is well established were excluded from the resistance rate analysis to avoid misinterpretation of antimicrobial susceptibility results.

The WHO List of Medically Important Antimicrobials classifies carbapenems as highest-priority critically important antimicrobials (HPCIAs) and authorizes their use exclusively in human medicine [41]. A carbapenem resistance gene was detected in a urine sample from a dog. Its presence in a companion animal isolate is unlikely to be driven by direct antimicrobial selective pressure in veterinary settings. Nevertheless, the use of antibiotics approved for human medicine is common in companion animal clinical practice. Broad-spectrum antibiotics and critically important antimicrobials (CIAs) account for more than 70% of veterinary antimicrobial prescriptions [6]. Previous studies evaluating antimicrobial use in South Korea reported the 15 most frequently prescribed antibiotics across 100 companion animal clinics. Among these, cefalexin (19.75%), amoxicillin–clavulanate (18.08%), metronidazole (11.72%), amoxicillin (6.74%), cefazolin (2.61%), ampicillin (2.31%), and clindamycin (1.60%) were commonly prescribed to both humans and companion animals [42]. This practice may facilitate the development of antimicrobial resistance and interspecies transmission.

Although some carbapenem resistance genes were detected in resistant isolates, further research is needed to identify other types of carbapenem resistance genes and genes conferring resistance to the other classes of antibiotics. blaNDM-1 is usually harbored in plasmids; therefore, we attempted to determine whether blaNDM-1 was located on the chromosome or plasmids. However, we were unable to separate plasmid DNA from chromosomal DNA during plasmid extraction, and thus the precise genetic location of blaNDM-1 could not be conclusively determined in this study. Currently, no veterinary-specific imipenem resistance breakpoints are available for companion-animal-derived isolates. Therefore, antimicrobial susceptibility was interpreted based on human clinical breakpoints, which may lead to discrepancies between disk-diffusion-based AMR profiles and MIC results. Importantly, the presence of the blaNDM-1 gene does not necessarily correlate with phenotypic carbapenem resistance. Previous study reported the existence of “silent” blaNDM-1-harboring K. pneumoniae isolates that remain susceptible to carbapenems (e.g., imipenem, meropenem) [43]. Silent antimicrobial resistance genes refer to resistance genes harbored by bacteria that do not confer phenotypic resistance under standard susceptibility testing conditions. Consistent with this concept, previous studies have reported that certain pathogens may harbor antimicrobial resistance genes while remaining phenotypically susceptible to the corresponding antibiotics. Such discrepancies can arise from various factors, including silencing of antibiotic resistance by mutation (SARM), promoter region effect, presence of integrons, regulatory factors, and epigenetic changes [44]. Future work should focus on clarifying whether these mechanisms underlie the observed genotype–phenotype discrepancies and on precisely determining the genetic locations of antimicrobial resistance genes, which would allow a more comprehensive and detailed characterization of resistance determinants and their roles in antimicrobial resistance.

This study appears somewhat limited in that it analyzed only samples obtained from a single tertiary veterinary hospital. Furthermore, considering that only about 50 urine samples were collected from animals with suspected UTIs over a two-year period, resulting in 23 strains, the results of the AMR profiling analysis are not generalizable. Nevertheless, the isolated strains and overall proportions are quite similar to previous reports conducted in clinical settings. E. coli was shown to be the predominant species that accounted for nearly half of all bacterial isolates, emphasizing its clinical significance as a major uropathogen in companion animals [3,45,46,47]. Moreover, despite the small sample size, the results demonstrate that AMR is a very critical crisis. Further studies involving larger sample sizes, diverse animal populations, and multicenter collaboration are warranted to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of AMR in companion animals. Monitoring antibiotic resistance profiles and the rational use of antibiotics in companion animals are essential for collecting data that aids in treating animal diseases. Furthermore, systematic testing of bacteria and periodic reporting of drug resistance patterns in companion animals continue to be needed for public health.

High prevalence of AMR, particularly multidrug resistance and ESBL production, among hospitalized companion animal uropathogens poses significant therapeutic challenges and potential zoonotic risks. The increasing trends in resistance to critically important antimicrobials underscore the urgent need for enhanced antimicrobial stewardship programs, diagnostic-guided therapy, and comprehensive surveillance systems in veterinary healthcare. These findings support the implementation of targeted infection control measures and evidence-based treatment protocols to preserve antimicrobial efficacy for the treatment of UTIs in companion animal medicine while minimizing public health risks through a One Health approach.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/vetsci13010070/s1, Figure S1: PCR image of blaNDM-1 (621 bp); Figure S2: PCR image of blaKPC (785 bp); Figure S3: PCR image of blaIMP (587 bp); Figure S4: PCR image of blaVIM (389 bp); Table S1: Primer sequences used are listed; Table S2: Antibiotic resistance profiles for total Gram-negative isolates; Table S3: MBC results for total Gram-negative isolates; Table S4: MBC results for total Gram-positive isolates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-H.K.; methodology, S.P. and C.H.; validation, S.P. and C.H.; formal analysis, S.P. and C.H.; investigation, S.P. and C.H.; resources, J.-H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P. and C.H.; writing—review and editing, S.-M.K. and T.-H.K.; visualization, S.P. and C.H.; supervision, T.-H.K.; project administration, T.-H.K.; funding acquisition, T.-H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the 2025 Daejeon RISE Project (DJR2025-12), funded by the Ministry of Education and Daejeon Metropolitan City, in the Republic of Korea, and research fund of Chungnam National University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the owners of all animals involved in the study. This study primarily used urine samples collected from animals during routine diagnostic and therapeutic procedures at the hospital. As no additional samples were collected solely for research purposes, the study did not violate the basic principles outlined in the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) standard operating guidelines. Therefore, the requirements for ethical review and approval were waived.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Perplexity, Generative AI search engine, for the purposes of light English correction. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| CLSI | Clinical and laboratory standards institute |

| CRE | Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales |

| ESBL | Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase |

| HGT | Horizontal gene transfer |

| MBC | Minimum bactericidal concentration |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MHA | Mueller-Hinton agar |

| MHB | Mueller-Hinton broth |

| 3GCRE | Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant |

| UTIs | Urinary tract infections |

| UPEC | Uropathogenic E. coli |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| XDR | Extensive drug-resistance |

References

- GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: A systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance, to Guide Research, Development, and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Marques, C.; Belas, A.; Aboim, C.; Cavaco-Silva, P.; Trigueiro, G.; Gama, L.T.; Pomba, C. Evidence of Sharing of Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains between Healthy Companion Animals and Cohabiting Humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 57, e01537-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, E.; Vila, A.; D’Ippolito, P.; Rico, A.J.; Rodon, J.; Roura, X. Prevalence and Characterization of Urinary Tract Infection in Owned Dogs and Cats From Spain. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2021, 43, 100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caddey, B.; Fisher, S.; Barkema, H.W.; Nobrega, D.B. Companions in antimicrobial resistance: Examining transmission of common antimicrobial-resistant organisms between people and their dogs, cats, and horses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2025, 38, e0014622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, H.I.G.; Silva, V.; de Sousa, T.; Calouro, R.; Saraiva, S.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P. Antimicrobial Resistance in European Companion Animals Practice: A One Health Approach. Animals 2025, 15, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Ramirez, S.; Aguilar-Vera, A.; Kumar, A.; Evans, B. Acinetobacter baumannii: Much more than a human pathogen. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e0080125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Forde, B.M.; Kidd, T.J.; Harris, P.N.A.; Schembri, M.A.; Beatson, S.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Walker, M.J. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00181-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rantala, M.; Holso, K.; Lillas, A.; Huovinen, P.; Kaartinen, L. Survey of condition-based prescribing of antimicrobial drugs for dogs at a veterinary teaching hospital. Vet. Rec. 2004, 155, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Briyne, N.; Atkinson, J.; Pokludova, L.; Borriello, S.P. Antibiotics used most commonly to treat animals in Europe. Vet. Rec. 2014, 175, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weese, J.S.; Blondeau, J.; Boothe, D.; Guardabassi, L.G.; Gumley, N.; Papich, M.; Jessen, L.R.; Lappin, M.; Rankin, S.; Westropp, J.L.; et al. International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases (ISCAID) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of bacterial urinary tract infections in dogs and cats. Vet. J. 2019, 247, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzariol, A.; Bazaj, A.; Cornaglia, G. Multi-drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria causing urinary tract infections: A review. J. Chemother. 2017, 29, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Walker, J.N.; Caparon, M.; Hultgren, S.J. Urinary tract infections: Epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, J.; Bartoletti, R.; Bruyere, F.; Cai, T.; Geerlings, S.; Koves, B.; Schubert, S.; Pilatz, A.; Veeratterapillay, R.; EWagenlehner, F.M.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Urological Infections: Summary of the 2024 Guidelines. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkey, J.; Wyres, K.L.; Judd, L.M.; Harshegyi, T.; Blakeway, L.; Wick, R.R.; Jenney, A.W.J.; Holt, K.E. ESBL plasmids in Klebsiella pneumoniae: Diversity, transmission and contribution to infection burden in the hospital setting. Genome Med. 2022, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.R.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, S.; Kang, K.S.; Ro, C.S.; Hyeon, J.Y. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Staphylococcus spp. and Escherichia coli isolated from dogs and cats in Seoul, South Korea during 2021–2023. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1563780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, A.Y.; Thompson, M.F.; Worthing, K.A.; Venturini, C.; Brookes, V.J.; Norris, J.M. Frequency and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of bacterial species isolated from canine and feline urine samples in Sydney, Australia, 2012–2021. Vet. Microbiol. 2025, 306, 110541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feuer, L.; Frenzer, S.K.; Merle, R.; Baumer, W.; Lubke-Becker, A.; Klein, B.; Bartel, A. Comparative Analysis of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius Prevalence and Resistance Patterns in Canine and Feline Clinical Samples: Insights from a Three-Year Study in Germany. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.M.D.; Menezes, J.; Marques, C.; Pomba, C.F. Companion Animals-An Overlooked and Misdiagnosed Reservoir of Carbapenem Resistance. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellera, F.P.; Fernandes, M.R.; Ruiz, R.; Falleiros, A.C.M.; Rodrigues, F.P.; Cerdeira, L.; Lincopan, N. Identification of KPC-2-producing Escherichia coli in a companion animal: A new challenge for veterinary clinicians. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2259–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyung, S.M.; Choi, S.W.; Lim, J.; Shim, S.; Kim, S.; Im, Y.B.; Lee, N.-E.; Hwang, C.-Y.; Kim, D.; Yoo, H.S. Comparative genomic analysis of plasmids encoding metallo-beta-lactamase NDM-5 in Enterobacterales Korean isolates from companion dogs. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Osman, M.; Green, B.A.; Yang, Y.; Ahuja, A.; Lu, Z.; Cazer, C.L. Evidence for the transmission of antimicrobial resistant bacteria between humans and companion animals: A scoping review. One Health 2023, 17, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.R.; Clabots, C.; Kuskowski, M.A. Multiple-host sharing, long-term persistence, and virulence of Escherichia coli clones from human and animal household members. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 4078–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Kim, S.B.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, S. Comparison of 16S rRNA Gene Based Microbial Profiling Using Five Next-Generation Sequencers and Various Primers. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 715500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 30th ed.; CLSI Supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, D.; Peirano, G.; Lascols, C.; Lloyd, T.; Church, D.L.; Pitout, J.D. Laboratory detection of Enterobacteriaceae that produce carbapenemases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 3877–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, J.; Widen, R.H.; Pignatari, A.C.; Kubasek, C.; Silbert, S. Rapid detection of carbapenemase genes by multiplex real-time PCR. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 906–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Revathi, G.; Bernabeu, S.; Nordmann, P. Detection of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Kenya. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 934–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, N.; Akeda, Y.; Sugawara, Y.; Takeuchi, D.; Motooka, D.; Yamamoto, N.; Laolerd, W.; Santanirand, P.; Hamada, S. Genomic Characterization of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae with Chromosomally Carried bla(NDM-1). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01520-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, N.; Akeda, Y.; Sugawara, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Motooka, D.; Iida, T.; Hamada, S. Role of Chromosome- and/or Plasmid-Located bla(NDM) on the Carbapenem Resistance and the Gene Stability in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0058722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majowicz, S.E.; Scallan, E.; Jones-Bitton, A.; Sargeant, J.M.; Stapleton, J.; Angulo, F.J.; Yeung, D.H.; Kirk, M.D. Global incidence of human Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections and deaths: A systematic review and knowledge synthesis. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2014, 11, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, C.M.; Sinclair, J.F.; Smith, M.J.; O’Brien, A.D. Shiga toxin of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli type O157:H7 promotes intestinal colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 9667–9672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, S.; Jordan, D.; Mitchell, T.; Wong, H.S.; Abraham, R.J.; Kidsley, A.; Turnidge, J.; Trott, D.J.; Abraham, S. Antimicrobial resistance in clinical Escherichia coli isolated from companion animals in Australia. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 211, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite-Martins, L.R.; Mahu, M.I.; Costa, A.L.; Mendes, A.; Lopes, E.; Mendonca, D.M.; Niza-Ribeiro, J.J.; de Matos, A.J.; da Costa, P.M. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in enteric Escherichia coli from domestic pets and assessment of associated risk markers using a generalized linear mixed model. Prev. Vet. Med. 2014, 117, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.; Bota, D.; Farbos, M.; Bernardin, F.; Ragetly, G.; Medaille, C. Risk factors for urinary tract infection with multiple drug-resistant Escherichia coli in cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2014, 16, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, R.; Canton, R.; Brown, D.F.; Giske, C.G.; Heisig, P.; MacGowan, A.P.; Mouton, J.W.; Nordmann, P.; Rodloff, A.C.; Rossolini, G.M.; et al. EUCAST expert rules in antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intra, J.; Carcione, D.; Sala, R.M.; Siracusa, C.; Brambilla, P.; Leoni, V. Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Enterobacter cloacae and Klebsiella aerogenes Strains Isolated from Clinical Specimens: A Twenty-Year Surveillance Study. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Fang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Huang, N.; Yu, K.; Zhou, C.; Cao, J.; Zhou, T. Characterization of resistance mechanisms of Enterobacter cloacae Complex co-resistant to carbapenem and colistin. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, T.K.; Lin, H.J.; Liu, P.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Hsueh, P.R. Antibiotic resistance in Enterobacter hormaechei. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2022, 60, 106650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafiz, T.A.; Alghamdi, G.S.; Alkudmani, Z.S.; Alyami, A.S.; AlMazyed, A.; Alhumaidan, O.S.; Mubaraki, M.; Alotaibi, F. Multidrug-Resistant Proteus mirabilis Infections and Clinical Outcome at Tertiary Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO’s List of Medically Important Antimicrobials: A Risk Management Tool for Mitigating Antimicrobial Resistance Due to Non-Human Use; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Kim, S.M.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.W.; Min, K.D. Assessment of Antimicrobial Use for Companion Animals in South Korea: Developing Defined Daily Doses and Investigating Veterinarians’ Perception of AMR. Animals 2025, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Shen, Z. Emergence of silent NDM-1 carbapenemase gene in carbapenem-susceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae: Clinical implications and epidemiological insights. Drug Resist. Updat. 2024, 76, 101123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deekshit, V.K.; Srikumar, S. ‘To be, or not to be’-The dilemma of ‘silent’ antimicrobial resistance genes in bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 2902–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, C.; Gama, L.T.; Belas, A.; Bergstrom, K.; Beurlet, S.; Briend-Marchal, A.; Broens, E.M.; Costa, M.; Criel, D.; Damborg, P.; et al. European multicenter study on antimicrobial resistance in bacteria isolated from companion animal urinary tract infections. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampacci, E.; Bottinelli, M.; Stefanetti, V.; Hyatt, D.R.; Sgariglia, E.; Coletti, M.; Passamonti, F. Antimicrobial susceptibility survey on bacterial agents of canine and feline urinary tract infections: Weight of the empirical treatment. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2018, 13, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, J.D.; Mavrides, D.E.; Graham, P.A.; McHugh, T.D. Results of urinary bacterial cultures and antibiotic susceptibility testing of dogs and cats in the UK. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2021, 62, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.