Simple Summary

With the increasing popularity of equestrian sports, proximal sesamoid bone fracture (PSBF) and flexor tendinitis in the forelimbs of sport horses have become increasingly common, often leading to musculoskeletal injuries. A 5-year-old horse developed swelling in the left fetlock joint and metacarpal region after exercise and was diagnosed with concurrent PSBF and flexor tendinitis. To promote recovery, the veterinarian administered non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in combination with low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) therapy. This treatment improved local microcirculation at the affected sites, accelerated tissue healing, and led to stable recovery of clinical parameters. This case highlights the effectiveness of LIPUS-assisted therapy in managing complex injuries of this kind, providing practical guidance for veterinarians and contributing to the health and sustainable development of equestrian sports.

Abstract

With the growing popularity of equestrian sports, the incidence of athletic injuries in horses has also risen. Among these injuries, proximal sesamoid bone fracture (PSBF) and flexor tendinitis are particularly common in the forelimbs of sport horses and represent major causes of musculoskeletal impairment. A 5-year-old horse presented with obvious symptoms such as swelling at the left fetlock joint and metacarpal region after exercise. Through lameness assessment, diagnostic imaging, and hematological testing, the horse was diagnosed with PSBF complicated by flexor tendinitis. The affected horse was treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs combined with low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) therapy. After treatment, local microcirculation at the fracture and flexor tendon sites was improved, tissue healing was accelerated, and clinical indicators were stabilized. This case report demonstrates the potential of LIPUS-assisted therapy in promoting the recovery of horses with PSBF and concurrent flexor tendinitis, providing a valuable clinical reference for the management of complex musculoskeletal injuries in veterinary practice.

1. Introduction

Fracture of the proximal sesamoid bone (PSB) is a serious and potentially life-threatening musculoskeletal injury in racehorses [1]. Proximal sesamoid bone fracture (PSBF) most frequently occurs in the forelimbs of racehorses and represents a major cause of fatal outcomes associated with musculoskeletal injuries [2,3,4]. The PSB is connected to the distal palmar and plantar surfaces of the third metacarpal (MC3) and metatarsal bones, serving as a fulcrum in the suspensory apparatus. Fracture of the PSB disrupts this support mechanism, leading to failure of the suspensory apparatus and, consequently, severe lameness or even euthanasia in affected racehorses [5,6,7,8,9].

Tendon injury is another common cause of lameness in racehorses. In particular, flexor tendinitis typically results in chronic lameness and requires prolonged healing and rehabilitation, causing significant economic losses in equestrian sports [10,11,12]. The treatment of equine flexor tendinitis is labor-intensive due to the slow regenerative capacity of tendon tissue. After injury, the composition, structure, and function of tendon fibers cannot be fully restored, which increases the risk of recurrence and limits the horse’s athletic performance [13,14,15].

Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) is a non-invasive therapeutic ultrasound modality that plays a crucial role in promoting fracture healing, enhancing wound repair, modulating immune regulation, and reducing inflammation [16]. As a form of physical therapy, LIPUS can stimulate the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts, and has a significant effect on promoting new bone formation and accelerating fracture repair [17]. In orthopedics and rehabilitation medicine, LIPUS is known to promote bone and soft tissue repair with significant therapeutic effects [18,19].

Currently, the main treatment regimens for PSBF include osteoclast inhibitors, e.g., tiludronate sodium, intra-articular injections, such as triamcinolone acetonide or platelet-rich plasma (PRP), into the metacarpophalangeal joint (MTPJ), orthopedic plate fixation, and radial pressure wave therapy [20]. Small bone fragments in PSBF cases may be removed surgically, and in some equine hospitals abroad, arthroscopic minimally invasive surgery is performed, but such procedures may damage the ligaments surrounding the sesamoid bones [21]. Cryotherapy has also been explored as a potential treatment for flexor tendinitis; however, standardized and evidence-based application protocols remain to be confirmed [22].

This paper reports a clinical case of a horse diagnosed with PSBF complicated by flexor tendinitis, providing details of its basic information, medical history, diagnostic methods, and treatment protocol. It aims to enhance the understanding of PSBF by equine veterinarians and to provide a reference for clinical diagnosis and therapy in equine practice. To our knowledge, this study is the first clinical report on the use of NSAIDs combined with LIPUS for treating flexor tendinitis secondary to PSBF in horses, and it highlights the key advantages of this combined approach, mechanistic complementarity, synergistic therapeutic effects, and practical safety, providing a valuable reference for future clinical applications.

2. Basic Information

A 5-year-old male Yili horse sustained an injury to its left forelimb due to continuous high-intensity exercise, resulting in obvious lameness. No immediate treatment was administered after the injury. One month later, the horse was referred to Tianma Cultural Park in Zhaosu County, Yili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (43°09′ N–43°15′ N) for clinical diagnosis and treatment.

3. Diagnosis

3.1. Clinical Examination

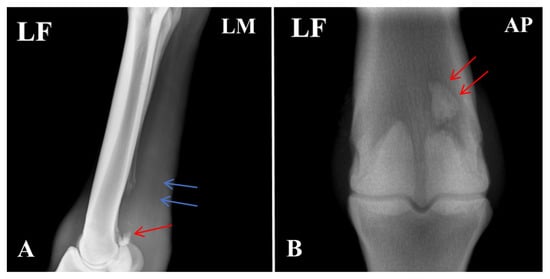

The affected horse was 5 years old and weighed 397 kg, with a body temperature of 38.9 °C and a heart rate of 46 beats per minute. The circumference of the left fetlock joint was 28 cm, compared with 24 cm on the right; while the left cannon bone measured 25 cm and the right 22 cm. Lameness was graded based on previously described criteria [23] (Table 1), with the horse scoring Grade VI. When standing, the horse frequently stamped the ground with its left forelimb. While leading and walking, severe lameness was observed in the left forelimb, accompanied by marked swelling of the fetlock joint and metacarpal region. A distinct pain response was noted when the affected area was palpated (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Lameness grades and scores of horses given exercise.

Figure 1.

Condition of the affected horse. (A–C) Proximal sesamoid bone fracture with marked swelling of the fetlock joint and flexor tendons. (D) Comparison between the affected and contralateral fetlock joints and flexor tendons. The arrows indicate the specific lesions.

3.2. Imaging Examination

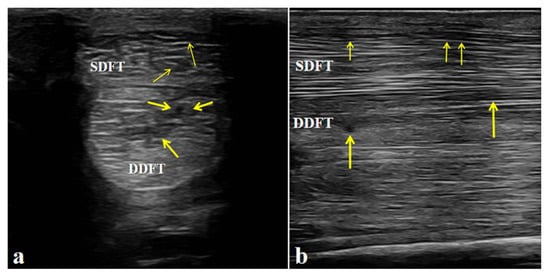

3.2.1. X-Ray Examination

Radiographic evaluation was performed to assess the type of lesion and to determine whether flexor tendinitis was present. Images were taken of the left forelimb (LF) in lateromedial (LM) and dorsopalmar/anteroposterior (AP) projections. The radiographs showed a clear fracture line at the proximal apex of the left proximal sesamoid bone, with separation of the fracture margins and the presence of a small free bone fragment. The fragment had an irregular shape and was displaced away from the main sesamoid body. Local cortical continuity was disrupted, and the trabecular pattern appeared disorganized. An increase in soft-tissue density was also noted in the flexor tendon region, raising suspicion of concurrent flexor tendinitis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Radiographic features of the affected horse with PSBF. (A) Fracture at the apex of the proximal sesamoid bone (red arrow: bone fragments; blue arrow: increased radiodensity in the flexor tendon region). (B) Fracture fragments of the proximal sesamoid bone. The arrows indicate the specific lesions.

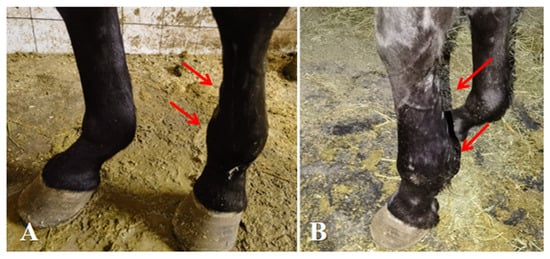

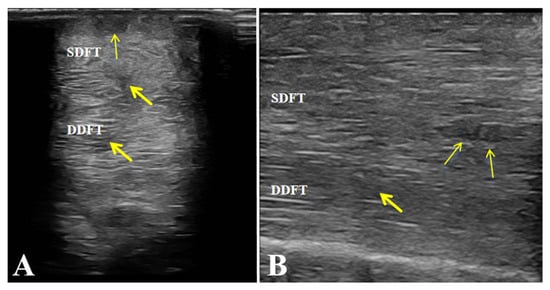

3.2.2. Ultrasound Examination

Ultrasonographic examination of the affected limb (left forelimb) showed a marked increase in the cross-sectional area of both the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) and the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) compared with the contralateral side. The tendon margins were still visible, although slightly roughened. The normal parallel fibrillar echogenic pattern was almost completely lost and replaced by a diffuse, heterogeneous, mildly hypoechoic appearance. These findings indicate mild injury to both the SDFT and DDFT and are consistent with the diagnosis of flexor tendinitis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Ultrasonographic features of the affected horse with flexor tendinitis. (a) Transverse sonograms of the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) and deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) (yellow arrow: lesion sites). (b) Longitudinal sonograms of the SDFT and DDFT (yellow arrow: lesion sites). Arrows indicate the sites of tendon injury.

3.3. Blood Physiological Examination

Blood physiological analysis was performed on the affected horse using automated analyzer BC-5300VET (Mindray Animal Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). The results showed elevated levels of inflammatory indicators, including neutrophils (NEU), white blood cells (WBC), and lymphocytes (LYM), indicating a systemic inflammatory response. In contrast, red blood cells (RBC) count, hemoglobin (HGB), mean platelet volume (MPV), and hematocrit (HCT) were decreased, suggesting potential bone marrow suppression, anemia, or dehydration (Table 2).

Table 2.

Routine blood test results of the affected horse.

3.4. Blood Biochemical Examination

Blood biochemical analysis was performed on the affected horse using automated analyzer BS-240VET (Mindray Animal Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). The results showed elevated levels of creatine kinase (CK) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), indicating muscle and soft-tissue injury accompanied by inflammation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Blood biochemical test results of the affected horse.

3.5. Serum Inflammatory Markers Measured by ELISA

Serum inflammatory cytokines were measured using equine-specific ELISA kits for TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Yancheng Maiji Biomedical Testing Service Center, Yancheng, China). The results showed elevated levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, suggesting a strong inflammatory response likely associated with the PSBF and concurrent injuries to the SDFT and DDFT (Table 4).

Table 4.

Serum ELISA test results of the affected horse.

3.6. Diagnostic Results

In summary, based on the horse’s clinical signs, medical history, imaging findings, and laboratory test results (hematology, biochemistry, and serum cytokine assays), the horse was diagnosed with PSBF complicated by inflammation of SDFT and DDFT and in the soft tissue surrounding the fractured bone.

4. Treatment and Outcome

4.1. Treatment Plan

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy combined with low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) adjuvant therapy was adopted for the affected horse. The detailed treatment protocol was as follows.

Treatment started with cold therapy. The affected limb was cooled with either an ice pack or cold-water soaking once daily for 30 min to help reduce acute swelling and inflammation and to prepare the tissues for the following interventions (days 1–7).

Local intra-articular medication was then administered to the fetlock joint. After flexing the limb and disinfecting the area with 75% alcohol, the joint was accessed through the lateral sesamoid–third metacarpal space. Procaine penicillin (6.4 million IU) was injected into the joint cavity to provide local antibacterial and analgesic effects. Through the same entry point, sodium hyaluronate (4 mL per injection) was given every other day for a total of five treatments to improve joint lubrication and protect the articular cartilage (days 1–10).

Precise medications were given according to the horse’s body weight. Flunixin meglumine (1.1 mg/kg) was administered intramuscularly once a day for pain control. Ampicillin sodium (20 mg/kg), dissolved in 4000 mL of 0.9% saline, was given once daily by intravenous infusion to provide systemic anti-inflammatory support, fluid supplementation, and infection prevention. These medications were continued until the acute inflammatory signs had clearly subsided (days 1–7).

LIPUS treatment started at the same time as the medications using HORSELIPUSPRO (transducer model OFS-20257, Beijing Zhouquan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China;) was used. A coupling gel was applied to ensure good contact between the probe and the skin. Using the ED-1001 mode, ultrasound was applied over the fetlock and the injured flexor tendon. The settings were: frequency 1.5 MHz, intensity 50–100 mW/cm2, once daily for 15 min. Treatments were carried out for 5 consecutive weeks, completing 35 sessions in total. The aim was to improve the local joint and tendon environment and support tissue repair (days 1–35).

4.2. Therapeutic Effect

4.2.1. Post-Treatment Clinical Examination

After five treatment courses over 35 days, the affected horse exhibited the following average indicators: body temperature 37.9 °C, heart rate 36 beats per minute, metacarpophalangeal joint circumference 25 cm (left forelimb) vs. 24 cm (right forelimb), and cannon bone circumference 23 cm (left forelimb) vs. 22 cm (right forelimb). Clinically, the horse maintained a normal state and exhibited no lameness when standing (Figure 4). Lameness during movement was significantly improved. Swelling of the metacarpophalangeal joint had completely subsided, and no tenderness was observed upon palpation. Swelling of the flexor tendons was alleviated, and the lameness grade was improved to Grade II.

Figure 4.

Post-treatment conditions of affected horse. (A,B) Complete healing of medial and lateral proximal sesamoid bone fractures, with resolution of swelling in the metacarpophalangeal joint and flexor tendons. The arrows indicate the specific lesions.

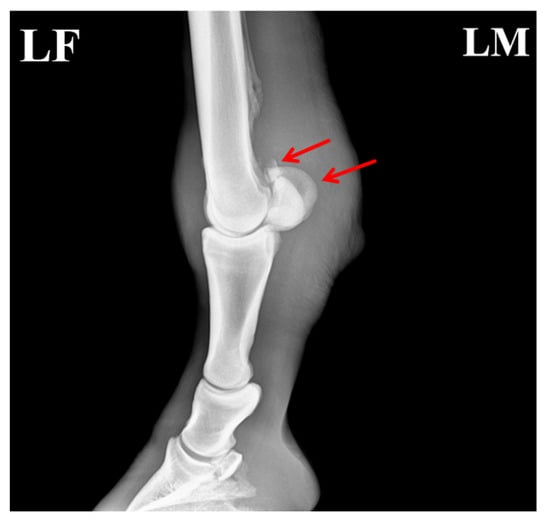

4.2.2. Post-Treatment Radiographic Examination

Due to the unique structure and function of the equine sesamoid bones, their healing process is typically more prolonged than that of other fractures. As shown in Figure 5, the proximal apex of the sesamoid bone exhibited a fracture with indistinct and blurred fracture margins, along with a localized area of increased soft-tissue density surrounding the fracture site. This homogeneous, cloud-like appearance indicated activation of the early repair response. Further imaging analysis revealed that the fracture gap was filled with a soft cartilaginous callus composed of collagen fibers and cartilaginous matrix synthesized by proliferating and differentiating fibroblasts and chondrocytes. This soft callus presented as a typical soft-tissue-density structure without signs of mineralization, and its contour conformed to the anatomical shape of the fracture ends, achieving initial bridging and stabilization of the fracture. Additionally, no significant bone resorption or necrosis was observed in the main fracture fragments. The gap between the small free fragment and the main sesamoid body had narrowed slightly compared with the pre-treatment images, with no evidence of displacement or malunion. These findings indicated that the healing process was in the critical stage of soft-callus formation, consistent with the physiological characteristics of sesamoid bone fracture repair in horses.

Figure 5.

Post-treatment radiograph of the affected horse showing formation of callus at the fracture site. The arrows indicate the specific lesions.

4.2.3. Post-Treatment Ultrasonographic Examination

After completing the medication combined with LIPUS-assisted therapy, ultrasonographic examination revealed marked improvement in the overall echogenicity of the affected SDFT and DDFT. Both tendons exhibited uniformly increased echogenicity, with no diffuse hypoechoic areas or regions of heterogeneous echotexture within the tendon substance. The internal homogeneity had become comparable to that of the contralateral healthy tendons. In the sagittal scans, the normal parallel, fibrillar echotexture was largely restored, showing well-organized, continuous fibers aligned with the longitudinal axis of the tendon, without evidence of disruption or fiber-pattern irregularity (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Post-treatment ultrasonographic images of the affected horse. (A,B) Increased echogenicity and uniform fibrillar alignment of the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) and deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT), without fibrosis or adhesions. Arrows indicate the repaired areas of the tendon post-treatment.

4.2.4. Post-Treatment Hematological and Physiological Examinations

Hematological and physiological examinations were performed on the affected horse after drug and LIPUS therapy. The results showed that all hematological parameters returned to normal ranges, indicating resolution of inflammation and recovery of systemic function (Table 5).

Table 5.

Hematological and physiological examination results of the affected horse after treatment.

4.2.5. Post-Treatment Blood Biochemical Examinations

Blood biochemical examinations were conducted on the affected horse after drug and LIPUS therapy. The results showed that the levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), calcium (Ca), inorganic phosphorus (P), and calcium–phosphorus product (Ca × P) were all increased, indicating enhanced osteoblast activity, which promoted calcium salt deposition and was beneficial for fracture healing (Table 6).

Table 6.

Blood biochemical examination results of the affected horse after treatment.

4.2.6. Post-Treatment Inflammatory Cytokine Detection

Serum inflammatory cytokine assays were performed on the affected horse after drug and LIPUS therapy. The results showed that the levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) returned to normal ranges, indicating that the inflammatory response caused by the fractures and tendon injuries was resolved, which accelerated fracture healing (Table 7).

Table 7.

Serum inflammatory cytokine levels of the affected horse after treatment.

Overall, after combined treatment with NSAIDs, antibiotics, intra-articular therapy, and LIPUS, the affected horse showed radiographic and ultrasonographic evidence of healing, as well as normalization of hematological and biochemical parameters, with no recurrence of flexor tendinitis. Radiographs demonstrated progressive healing of the proximal sesamoid bone fracture, confirming the therapeutic effectiveness of LIPUS-assisted therapy.

5. Discussion

Treatment options for minor fractures in racehorses include rest, external fixation, therapeutic cauterization, systemic administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), resection of the suspensory ligament at the apex of the affected sesamoid bones, neurectomy, surgical removal of fracture fragments, and autologous cancellous bone grafting [24,25,26]. Typically, the proximal sesamoid bones of horses play a supportive role in the contraction of the flexor tendons behind the metacarpophalangeal joint. During intense exercise, the joint flexes excessively, and the sesamoid bones are subjected to compressive forces between the third metacarpal bone, proximal phalanx, and adjacent soft tissues. Consequently, pressure can increase on the suspensory ligaments, particularly at the apex and lateral margins of the sesamoid bones, which may impair local blood circulation, reduce bone mineral density, and thereby increase the risk of PSBF and secondary flexor tendinitis [27,28,29]. Forelimb flexor tendinitis has been reported to account for 6–13% of all musculoskeletal injuries in racehorses, with most studies linking its occurrence to racing or other high-intensity athletic activities [30,31]. The Yili horse in this study developed lameness and swelling of flexor tendons due to high-intensity competition and was subsequently diagnosed with flexor tendinitis secondary to PSBF based on clinical and imaging examinations.

Preliminary diagnosis of flexor tendinitis secondary to PSBF can usually be achieved through medical history review, visual inspection during rest and movement, palpation, and local nerve block tests, among which, local nerve block helps accurately identify the lesion [32]. In this case, radiography and ultrasonography played a key role in confirming the diagnosis, supported by hematological and biochemical analyses. The imaging findings showed a fracture at the apex of the proximal sesamoid bone, accompanied by inflammation of the SDFT and DDFT. Blood tests revealed elevated NEU, WBC, and LYM, indicating a systemic inflammatory response secondary to fracture and tendon injury, whereas RBC and HGB levels were decreased, suggesting bone marrow suppression.

After a fracture, osteoblast activity increases, leading to the secretion of ALP, which elevates the concentration of local inorganic phosphorus, thereby promoting calcium salt deposition and hydroxyapatite remodeling—key process in fracture healing [33]. Calcium (Ca) and phosphorus (P) in the serum interact with each other, and their product (Ca × P) is maintained within a certain range. When Ca × P exceeds the saturation point of Ca3(PO4)2 and CaCO3, calcium phosphate begins to nucleate and form a precipitate which subsequently becomes mineralized as Ca3(PO4)2 and CaCO3, which are deposited in the bone as inorganic components of bone [34]. Therefore, ALP, Ca, P, and Ca × P can be used as reliable biochemical markers to evaluate osteoblast activity and fracture healing progression. Similarly, CK and LDH are recognized as markers of muscle injury, reflecting the extent of tissue damage and repair [35].

In this case, treatment with NSAIDs combined with adjuvant LIPUS therapy led to notable increases in ALP, Ca, P, and Ca × P levels compared with their pre-treatment values, indicating enhanced osteoblast metabolism and accelerated fracture healing. Meanwhile, serum CK and LDH levels decreased significantly compared with pre-treatment, implying reduced muscle activity based on lameness. Together, these findings suggest that LIPUS, when combined with NSAIDs, can stimulate bone metabolism, improve tissue regeneration, and mitigate inflammatory responses.

Proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, play central roles in fracture-associated inflammation and bone metabolism regulation [36]. Specifically, TNF-α is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that binds to tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 (TNFR-1), thereby promoting the production of other cytokines. IL-1β, primarily produced by macrophages and endothelial cells, stimulates the activation of T lymphocytes and secretion of B-cell antibodies, thereby amplifying inflammation. IL-6, as a pro-inflammatory cytokine, recognizes and binds to IL-6 receptors on the surface of target cells to form a signal-transducing complex that regulates cytokine expression [37,38].

In this study, the serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 of the affected horse were raised before treatment, indicating that these cytokines are involved in the early inflammatory response associated with PSBF and tendon injury. After treatment, their levels returned to referenced ranges, suggesting that NSAIDs combined with LIPUS effectively reduced inflammatory cytokine expression, alleviated fracture-related inflammation, and accelerated and tendon healing.

Currently, clinical management of PSBF-related flexor tendinitis varies widely and includes the use of osteoclast inhibitors, intra-articular injection into the MTPJ, orthopedic plate fixation, and radial pressure wave therapy [39]. In instances with small free bone fragments, surgical excision may be considered, and arthroscopic minimally invasive procedures have been adopted in some international equine clinics. However, such invasive techniques may cause secondary injury to the suspensory ligaments and tendon structures surrounding the sesamoid bone [20]. To avoid the risks of secondary trauma and infection associated with surgery, this study employed a non-invasive strategy consisting of NSAID blockade therapy combined with LIPUS intervention, offering both safety and effectiveness.

Previous studies have confirmed the central role of LIPUS in promoting fracture repair. According to Rawool et al. [40], LIPUS significantly increases vascular perfusion at the fracture region, an essential determinant of the healing process. Older horses, due to vascular sclerosis and reduced metabolic activity, typically have markedly poorer perfusion than younger horses. Clinical observations suggest that LIPUS combined with NSAIDs may help improve blood supply at lesion sites, thereby providing enhanced nutritional support for bone healing, and may offer potential adjunctive benefits in alleviating the delayed healing commonly observed in aged horses. Moreover, LIPUS enhances integrin expression, facilitates osteoblast adhesion and proliferation at the fracture site, and modulates bone-repair-related gene expression, thereby accelerating the healing process [41]. As a continuously advancing biophysical therapy, LIPUS optimizes bone healing while minimizing thermal effects, achieving precise regulation of bone formation through molecular, cellular, and biomechanical interactions [42]. In the field of tendon repair, LIPUS has demonstrated clear advantages as well, including improvement of the early healing microenvironment of flexor tendon tears, reduction in inflammatory cell infiltration, and enhancement of functional range of movement at the repair site [43,44]. In clinical practice, LIPUS is often incorporated as part of a combination therapy in tendon repair interventions, with its therapeutic effects being closely dependent on the synergy of the overall treatment regimen.

It is important to note that single therapy has inherent limitations in the management of PSBF-associated flexor tendinitis. NSAIDs effectively alleviate inflammatory pain symptoms, yet they lack direct regenerative effects on bone and tendon tissue; long-term use may also increase the risk of chronic injury, resulting in a “treating the symptoms but not the cause” dilemma [45]. Conversely, LIPUS can effectively promote tissue regeneration but is insufficient for rapid suppression of acute inflammatory cascades, creating a “treating the cause but with delayed effect” limitation [46]. The combined therapy proposed in this study offers an innovative solution to these clinical pain points. First, to reconcile the adverse-effect risks of prolonged NSAID use and the slower onset of LIPUS, we adopted an optimized design of “short-term, moderate-dose NSAIDs + full-course LIPUS repair.” This allows the duration of NSAID administration to be reduced while maintaining adequate anti-inflammatory efficacy, thereby significantly lowering the risk of gastrointestinal or renal complications. Moreover, NSAID-mediated inflammation control may act synergistically with low-intensity pulsed ultrasound to promote the initiation of tissue repair, helping to initiate the healing process at an earlier stage [47,48]. Second, to address the high risk of chronic flexor tendinitis associated with fractures at the base of the metacarpal bones, the combined therapy simultaneously promotes cartilaginous callus formation and the orderly remodeling of tendon collagen, thereby enhancing fracture healing outcomes, reducing tendon adhesions, and overcoming the traditional therapeutic limitation in which symptoms are readily alleviated but functional recovery remains difficult [49,50,51]. Third, the non-invasive nature of LIPUS combined with oral NSAIDs provides a dual bone-tendon repair strategy without requiring surgical intervention, offering an attractive alternative for mild cases unsuitable for surgery or for postoperative rehabilitation, thereby expanding treatment options for musculoskeletal injuries [52,53].

In this study, a single Yili horse diagnosed with PSBF-induced flexor tendinitis triggered by exercise overload underwent comprehensive evaluation, including lameness scoring, imaging examinations, and hematological testing. Based on the confirmed etiology and specific lesion location, a targeted treatment plan was made. After receiving combined NSAID and LIPUS therapy, the horse showed improved local blood supply and enhanced fracture healing, and it ultimately achieved a favorable clinical outcome. These observations suggest that LIPUS may have potential therapeutic utility in PSBF and associated flexor tendinitis, and that its combined application with NSAIDs may offer both efficacy and safety. As an initial attempt at integrating NSAIDs with LIPUS for this condition, this study provides a new exploratory direction, though its potential clinical value requires further validation in a larger sample size. In future studies, larger sample sizes and rigorously designed randomized controlled trials should be employed, with explicit exclusion of confounding interventions, appropriate control groups, extended follow-up periods, and standardized evaluation criteria and methodologies. These approaches will allow more scientific and objective validation of the independent efficacy of LIPUS, as well as the effectiveness and safety of combined NSAID–LIPUS therapy, thereby providing reliable evidence-based support for the clinical management of this condition.

Author Contributions

Z.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing; Y.Y.: Software, Validation; Y.M.: Validation, Resources; Z.M.: Resources, Writing—review and editing; H.F.: Software, Data curation; X.W.: Software, Validation; X.C.: Investigation, Data curation; T.L.: Formal analysis, Visualization; J.L.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization; Q.G.: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the project from the Department of Science and Technology of the Autonomous Region—Special Fund for Central Government-Guided Local Science and Technology Development: Integrated Innovation and Application of Key Technologies for the Prevention and Control of Major Equine Diseases in Xinjiang. Subproject: Integrated Innovation and Application of Key Technologies for the Prevention and Control of Common Equine Diseases in Xinjiang (Grant No. ZYYD2023C03-3, 202301–202412); the Major Science and Technology Special Project of the Autonomous Region: Key Technology Research and Development for the Xinjiang Horse Industry, subproject: Development of Diagnostic Methods and Comprehensive Prevention and Control Technologies for Common Equine Diseases (Grant Nos. 2022A02013-2-7, 20221201–20251231); Major Science and Technology Project of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2022A02013-2-7, 2024A02005-2-3); Central Government-guided Local Science and Technology Development Project (ZYYD2023C03-3).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Xinjiang Agricultural University (Approval Number: 2024028, date 27 December 2024). Informed consent was obtained from the owner of the horses. The horse described in this case report was not included in our previously published randomized controlled trial on LIPUS therapy (Scientific Reports, 2025). The datasets are completely independent.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the owner of the horse.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yuhui Ma was employed by the company Xingjiang Zhaosu County Xiyu Horse Industry Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Basran, P.S.; Gao, J.; Palmer, S.; Reesink, H.L. A Radiomics Platform for Computing Imaging Features from µCT Images of Thoroughbred Racehorse Proximal Sesamoid Bones: Benchmark Performance and Evaluation. Equine Vet. J. 2021, 53, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, S.E.; McDonough, S.P.; Mohammed, H.O. Reduction of Thoroughbred Racing Fatalities at New York Racing Association Racetracks Using a Multi-Disciplinary Mortality Review Process. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2017, 29, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stover, S.M.; Murray, A. The California Postmortem Program: Leading the Way. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 2008, 24, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.; Hawkins, D.L.; Scollay, M.C. Race-Start Characteristics and Risk of Catastrophic Musculoskeletal Injury in Thoroughbred Racehorses. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001, 218, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrice-West, A.V.; Thomas, M.; Wong, A.S.M.; Flash, M.; Whitton, R.C.; Hitchens, P.L. Linkage of Jockey Falls and Injuries with Racehorse Injuries and Fatalities in Thoroughbred Flat Racing in Victoria, Australia. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 11, 1481016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boden, L.A.; Anderson, G.A.; Charles, J.A.; Morgan, K.L.; Morton, J.M.; Parkin, T.D.H.; Slocombe, R.F.; Clarke, A.F. Risk of Fatality and Causes of Death of Thoroughbred Horses Associated with Racing in Victoria, Australia: 1989–2004. Equine Vet. J. 2010, 38, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brett, B.L.; Gardner, R.C.; Godbout, J.; Dams-O’cOnnor, K.; Keene, C.D. Traumatic Brain Injury and Risk of Neurodegenerative Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 91, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennet, E.D.; Parkin, T.D.H. Fifteen Risk Factors Associated with Sudden Death in Thoroughbred Racehorses in North America (2009–2021). J. Am. Vet. Med Assoc. 2022, 260, 1956–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.C.; Riggs, C.M.; Cogger, N.; Wright, J.; Al-Alawneh, J.I. Noncatastrophic and Catastrophic Fractures in Racing Thoroughbreds at the Hong Kong Jockey Club. Equine Vet. J. 2019, 51, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, A.; Asplund, K.; Bergh, A.; Hyytiäinen, H. Systematic Review of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine in Sport and Companion Animals: Therapeutic Ultrasound. Animals 2022, 12, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depuydt, E.; Broeckx, S.Y.; Van Hecke, L.; Chiers, K.; Van Brantegem, L.; van Schie, H.; Beerts, C.; Spaas, J.H.; Pille, F.; Martens, A. The Evaluation of Equine Allogeneic Tenogenic Primed Mesenchymal Stem Cells in a Surgically Induced Superficial Digital Flexor Tendon Lesion Model. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 641441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batson, E.L.; Paramour, R.J.; Smith, T.J.; Birch, H.L.; Patterson-Kane, J.C.; Goodship, A.E. Are the Material Properties and Matrix Composition of Equine Flexor and Extensor Tendons Determined by Their Functions? Equine Vet. J. 2003, 35, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.H.; Halper, J. Connective Tissue Disorders in Domestic Animals. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1348, 325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Forlizzi, J.M.; Ward, M.B.; Whalen, J.; Wuerz, T.H.; Gill, T.J. Core Muscle Injury: Evaluation and Treatment in the Athlete. Am. J. Sports Med. 2023, 51, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jann, H.; Stashak, T.S. Tendon and Paratendon Lacerations. In Equine Wound Management; Stashak, T.S., Theoret, C.L., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Ames, IA, USA, 2008; pp. 489–508. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W.; Liang, B.; Yan, K.; Zhang, G.; Zhuo, J.; Cai, Y. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound: A Physical Stimulus with Immunomodulatory and Anti-inflammatory Potential. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 52, 1955–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Wu, L.; Liu, J.; Qin, Y.; Li, B.; Zhou, Q. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Protects Subchondral Bone in Rabbit Temporomandibular Joint Osteoarthritis by Suppressing TGF-β1/Smad3 Pathway. J. Orthop. Res. 2020, 38, 2505–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ye, K.; Yin, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, D.; Gan, Y.; Peng, D.; Zhao, L.; Xiao, M.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Ameliorates erectile Dysfunction Induced by Bilateral Cavernous Nerve Injury Through Enhancing Schwann Cell-Mediated Cavernous Nerve Regeneration. Andrology 2023, 11, 1188–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Wu, S.; Lian, H.; Lin, Y.; Zhuang, R.; Thapa, S.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Y.; Lin, J. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Attenuates Cardiac Inflammation of CVB3-Induced Viral Myocarditis via Regulation of Caveolin-1 and MAPK pathways. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 1963–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Roux, C.; Carstens, A. Axial sesamoiditis in the horse: A review. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2018, 89, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothaug, P.G.; Boston, R.C.; Richardson, D.W.; Nunamaker, D.M. A Comparison of Ultra-High–Molecular Weight Polyethylene Cable and Stainless Steel Wire using Two Fixation Techniques for Repair of Equine Midbody Sesamoid Fractures: An In Vitro Biomechanical Study. Vet. Surg. 2002, 31, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermann, S.; Vollmar, B.; Thorlacius, H.; Menger, M.D. Surface Cooling Inhibits Tumor Necrosis Factor-α-Induced Microvascular Perfusion Failure, Leukocyte Adhesion, and Apoptosis in Striated Muscle. Surgery 1999, 126, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, E.J. Lameness Evaluation of the Athletic Horse. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 2018, 34, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fretz, P.B.; Barber, S.M.; Bailey, J.V.; McKenzie, N.T. Management of Proximal Sesamoid Bone Fractures in the Horse. J. Am. Vet. Med Assoc. 1984, 185, 282–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churchill, E.A. Surgical Removal of Fracture Fragments of the Proximal Sesamoid Bone. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1956, 128, 581–582. [Google Scholar]

- de Preux, M.; Precht, C.; Travaglini, A.T.; Propadalo, L.M.; Farra, D.; Vidondo, B.; Koch, C. Influence of the Vertek Aiming Device on the Surgical Accuracy of Computer-Assisted Drilling of the Equine Distal Sesamoid Bone—An Experimental Cadaveric Study. Vet. Surg. 2025, 54, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, E.D.; Clegg, P.D.; Senior, J.M.; Singer, E.R. Destructive Lesions of the Proximal Sesamoid Bones as a Complication of Dorsal Metatarsal Artery Catheterization in Three Horses. Vet. Surg. 2005, 34, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, B.; Rijkenhuizen, A.; Barneveld, A. The Arterial Shift Features in the Equine Proximal Sesamoid Bone. Vet. Q. 1996, 18, S110–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, B.P.M.; Rijkenhuizen, A.B.M.; Buma, P.; Barneveld, A. A Study on the Pathogenesis of Equine Sesamoiditis: The Effects of Experimental Occlusion of the Sesamoidean Artery. J. Vet. Med. Ser. A 2002, 49, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesen, A.B.; Dabareiner, R.M.; Chaffin, M.K.; Carter, G.K. Tendinitis of the Proximal Aspect of the Superficial Digital Flexor Tendon in Horses: 12 Cases. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2009, 234, 1432–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, B.A.; Dart, A.J.; Hodgson, D.R.; Smith, R.K.W. Superficial Digital Flexor Tendonitis in the Horse. Equine Vet. J. 2000, 32, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, C.T.; Clegg, P.D.; Birch, H.L. A Review of Tendon Injury: Why Is the Equine Superficial Digital Flexor Tendon Most at Risk? Equine Vet. J. 2010, 42, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schini, M.; Vilaca, T.; Gossiel, F.; Salam, S.; Eastell, R. Bone Turnover Markers: Basic Biology to Clinical Applications. Endocr. Rev. 2022, 44, 417–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijing Medical College. Biochemistry; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1978; p. 497. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.T.; Li, J.P. Changes in αB-Crystallin Protein in Skeletal Muscle of Rats after Exhaustive Eccentric Exercise and the Effect of Acupuncture. J. Shandong Sport Univ. 2014, 30, 63–67. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhizi, F.; Asoudeh, F.; Hamedi-Shahraki, S.; Asghari, S. Vitamin D Status Is Associated with Inflammatory Biomarkers and Clinical Symptoms in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Knee 2022, 36, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, M.F.; Finotto, S. IL-6 Signaling in Autoimmunity, Chronic Inflammation and Inflammation-Associated Cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011, 22, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Yang, H.; Yang, J.Y.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Kweon, M.N. Interleukin-1 Signaling in Intestinal Stromal Cells Controls KC/CXCL1 Secretion, Which Correlates with Recruitment of IL-22-Secreting Neutrophils at Early Stages of Citrobacter rodentium Infection. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 3257–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliye, S.; Voute, L.; Lund, D.; Marshall, J.F. An Inertial Sensor-Based System Can Objectively Assess Diagnostic Anaesthesia of the Equine Foot: Inertial Sensor-Based Objective Analysis of Diagnostic Anaesthesia of the Foot. Equine Vet. J. 2013, 45, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawool, N.M.; Goldberg, B.B.; Forsberg, F.; Winder, A.A.; Hume, E. Power Doppler Assessment of Vascular Changes During Fracture Treatment With Low-Intensity Ultrasound. J. Ultrasound Med. 2003, 22, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.-H.; Yang, R.-S.; Huang, T.-H.; Lu, D.-Y.; Chuang, W.-J.; Huang, T.-F.; Fu, W.-M. Ultrasound Stimulates Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression and Increases Bone Formation through Integrin, Focal Adhesion Kinase, Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase, and Akt Pathways in Osteoblasts. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 69, 2047–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, K.; Leven, R.M.; Mazhar, K.; Sumner, D.R.; Virdi, A.S. Early Gene Response to Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound in Rat Osteoblastic Cells. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2005, 31, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Cheuk, Y.; Chan, K.; Hung, L.; Wong, M.W. Is Cultured Tendon Fibroblast a Good Model to Study Tendon Healing? J. Orthop. Res. 2008, 26, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.-C.; Wong, Y.-P.; Cheuk, Y.-C.; Lee, K.-M.; Chan, K.-M. TGF-β1 Reverses the Effects of Matrix Anchorage on the Gene Expression of Decorin and Procollagen Type I in Tendon Fibroblasts. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2005, 431, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Sun, J.; Yu, X.; He, Y. Acupoint injection in improving pain and joint function of knee osteoarthritis patients: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e24997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Cheng, L.; Cheng, Q. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound promotes mesenchymal stem cell transplantation-based articular cartilage regeneration via inhibiting the TNF signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, F.; Yan, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhou, D.; Jiang, X.; Song, C.; Fu, Z.; Liu, Z. The Role of Persistent Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Infected Nonunion: A Narrative Review. Immunity Inflamm. Dis. 2025, 13, e70260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, T.; Hoshi, K.; Ando, T. Is the HAS-BLED score useful in predicting post-extraction bleeding in patients taking warfarin? A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, J.D.; Stride, M.; Scott, A. Tendons—Time to revisit inflammation? Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 47, 1553–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, D.; Tamaki, T.; Fukuzawa, T.; Natsume, T.; Yamato, I.; Uchiyama, Y.; Saito, K.; Okami, K. Peripheral Nerve Regeneration Using a Cytokine Cocktail Secreted by Skeletal Muscle-Derived Stem Cells in a Mouse Model. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-G.; Han, S.B.; Song, S.J.; Kim, T.J.; Ha, C.-W. Platelet-rich plasma therapy for knee joint problems: Review of the literature, current practice and legal perspectives in Korea. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2012, 24, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez-Sirvent, E.; Ibarzábal-Gil, A.; Rodríguez-Merchán, E.C. Treatment options for aseptic tibial diaphyseal nonunion: A review of selected studies. EFORT Open Rev. 2020, 5, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ruzbarsky, J.J.; Layne, J.E.; Xiao, X.; Huard, J. Stem Cells and Bone Tissue Engineering. Life 2024, 14, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.