Simple Summary

Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) is the major etiological agent of avian colibacillosis, a condition that significantly compromises poultry health and productivity, adversely affects animal welfare, and leads to substantial economic losses worldwide. This review explores the organism’s characteristics, genetic diversity, pathogenesis, and virulence factors. Additionally, we highlight the limitations of conventional diagnostic and control approaches and discuss emerging advanced technologies that enhance diagnostic accuracy and offer promising new strategies for disease management.

Abstract

Avian colibacillosis is a significant disease in poultry caused by avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC). APEC affects birds of all ages and leads to severe lesions in multiple organ systems, including the respiratory, digestive, and reproductive tracts. The disease imposes a substantial economic burden on poultry production due to increased mortality and decreased meat and egg production associated with the disease. Moreover, there is growing concern about the potential transmission of APEC to humans via contaminated poultry products, where it may cause extraintestinal infections. Given these implications for both animal welfare and public health, a thorough understanding of the pathogen is essential for developing effective control strategies. This review seeks to discuss the major facets of colibacillosis and outlines key considerations for advancing its diagnosis and effective management.

1. Introduction

Escherichia coli is a Gram-negative bacterium that belongs to the Enterobacteriaceae family and known to be a normal resident of the intestinal tract of the vertebrate [1]. Although they usually present as a component of the normal intestinal biota, some strains have acquired the ability to cause disease and thus are classified as pathogenic [2]. Pathogenic E. coli generally differ from their non-pathogenic counterparts in possessing certain pathogenicity determinants or virulence factors that allow them to establish infection [3,4]. Based on their predilection for a site of infection, pathogenic E. coli can be broadly classified into two categories: those that act inside the intestinal tract, i.e., intestinal pathogenic E. coli (IPEC), or diarrheagenic E. coli (DEC) and others which extend beyond the intestinal barrier known as extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) [5,6]. Deeper categorization is based on the virulence profile of the strain and the resulting clinical manifestation. For instance, enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), enterohaemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and diffusely adherent E. coli (DAEC) are all different pathotypes of the IPEC category [7,8].

Moreover, Clermont et al. clustered E. coli according to their genetic relatedness into seven phylogroups named A, B1, B2, C, D, E, and F [9,10], and, in a recent update, introduced a new intermediate phylogroup between the F and B2 phylogroups named the phylogroup G, expanding the total phylogroups to eight [11]. Virulent strains associated with extraintestinal infections usually belong to the phylogroups B2 and D [12,13]. On the other hand, the phylogroup A often contains the commensal E. coli [14]. APEC is a member of the extraintestinal category of pathogenic E. coli with potential to infect poultry of different ages and types, including broilers and layers, causing severe pathologies in different tissues collectively known as “avian colibacillosis”. The infection could be systemic resulting in airsacculitis, perihepatitis, pericarditis, peritonitis, and fatal septicemia [15]. Also, localized infections such as cellulitis and salpingitis could occur. The disease often results in high mortality and morbidity rates leading to severe economic losses. Furthermore, the zoonotic potential of APEC has been suggested, imposing a further burden on public health. This review focuses on different aspects of APEC including the pathogenesis of the disease, the involved virulence factors, and the zoonotic potential, and critically discusses the available control strategies.

2. APEC Pathogenesis and Pathological Picture

The widespread multiple lesions of avian colibacillosis affecting different organs indicate the systemic nature of the disease. The chicken gut constitutes a complex set of niches for a variety of bacterial species including E. coli [16,17,18]. The E. coli in the intestine of healthy chicken could have multiple virulence factors, rendering them as potential APEC able to initiate infection [19,20]. Being residents of the intestinal tract allows potential APEC to spread via chicken debris into the surrounding environment [21]. This highlights the role of free-living birds in the transmission of the disease. However, for intensive farming, bad housing conditions exacerbate the situation by increasing the E. coli counts in the surrounding environment with a bacterial load in the poultry house dust up to 106 CFU of E. coli per gram [15,22]. In turn, this constitutes a potential source of infection to chicken through contaminated feed, water, and equipment, as well as aerosol and dust [23].

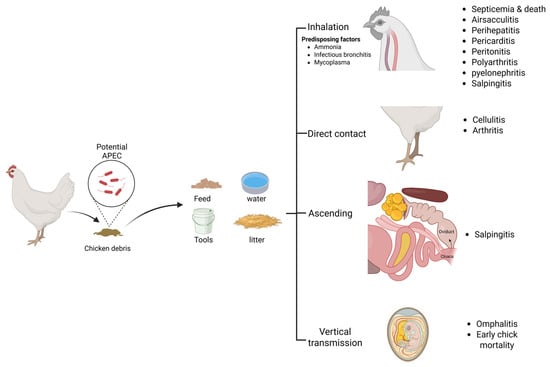

APEC can initiate either primary or secondary infection [24]. The pathogen can transmit to healthy birds either horizontally or vertically (Figure 1). The horizontal transmission is mainly through the respiratory route and usually results in the generalized form of the disease [25,26,27]. However, other routes of transmission that result in localized forms of the disease also occur, such as the ascending route from the cloaca to the oviduct leading to salpingitis [28,29], and the direct contact through skin leading to cellulitis [30]. APEC are also able to transmit vertically from diseased breeders to the yolk sac [29,31]. Therefore, the outcome of infection depends mainly on the route of transmission and the immune status of the bird. Several factors were found to predispose for APEC infection, such as elevated ammonia levels in the poultry house and the infection by other respiratory pathogens such as Mycoplasma and infectious bronchitis (IB) [32]. Ammonia is toxic and is known to damage epithelial cells, enabling APEC infection via the air sac and lung [32,33].

Figure 1.

Pathogenesis of APEC: transmission routes and lesions.

As mentioned above, the generalized (systemic) form of colibacillosis usually occurs through the respiratory route. Once the bacterium is inhaled, it establishes itself in the respiratory tract via adhesion to the lining epithelium [34,35]. This requires the bacteria to overcome the innate defensive barriers such as the lining mucous and the existing antimicrobial peptides [36]. The contact between APEC and the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract stimulates regulatory changes of the cells such as the upregulation of the toll-like receptors in lung and tracheal cells [33,37]. The toll-like receptors mediate pathogen recognition and pro-inflammatory cytokines production such as IL-1B, IL6, and IL8 [38,39]. The cytokines stimulate the chemotaxis of innate immune cells such as macrophages and heterophils to the site of infection [40]. A definitive characteristic of the avian lung-associated immunity is the scarcity of the resident immune cells such as heterophils and macrophages on the lining epithelium [41,42]. This feature, besides the large surface area and the very thin blood–gas barrier of the bird’s lower respiratory tract, may increase the susceptibility to infection by respiratory pathogens [43]. Innate immune cells such as heterophils and macrophages were found to increase in the lungs and spleen after experimental infection of chickens with APEC [44,45,46]. This indicates that the defense against bacterial infection in chicken lungs is mainly dependent on the recruitment of blood immune cells to the site of infection [33]. Alber et al. reported a higher heterophil than macrophage population in the lung six hours post inoculation with two different APEC serotypes, which suggests heterophils as the main early responder at the site of infection [46]. Both macrophages and heterophils are phagocytic cells that engulf the pathogen to contain the infection with additional antigen-presenting features for macrophages [47]. Upon activation of the antigen-presenting cells, the chemotaxis of more immune cells to the site of infection takes place mediated by cytokines [48,49,50]. Simultaneously with the activation of macrophages, other adaptive immune cells are activated, such as CD4+ T cells that recognize the presented antigen which indicates the synergy between the innate and the adaptive immune responses in the fight against APEC [50,51].

The immune response in the lungs of infected bird results in inflammation of the respiratory tissues such as air sacs and bronchi (i.e., airsacculitis and bronchitis, respectively), with congestion of blood capillaries, oedema, fibrinous deposits, and inflammatory cell infiltrations in the air sacs [27]. Loss of air sac transparency with yellowish white exudate could be seen. Despite the inflammatory response, APEC have multiple virulence factors that help the bacterium to overcome immunity and evade phagocytosis such as the capsule, fimbriae, and the surface LPS [22,52]. Furthermore, APEC were reported to invade the cells of the respiratory epithelium and the adjacent fibroblasts [35,53]. They are also able to actively invade, survive, and proliferate inside macrophages [46,52,54,55], or even induce apoptosis of the macrophages [38,56]. The invasive nature of APEC into the epithelia and phagocytes might explain the detection of the pathogen in the blood stream of the bird a few hours post inoculation through the trachea or air sac and accounts for the generalized pathological picture that follows the localized lesions in the respiratory tract [26,46,56]. However, the precise molecular mechanism of invasion by APEC still needs further studies. Once the bacterium reaches the circulatory system, the systemic form of infection is established. Systemically infected birds show lethargy and a decrease in water and feed intake, followed by sudden death due to septicemia [15]. The postmortem picture of the dead birds usually includes airsacculitis and inflammation of serous membranes, i.e., perihepatitis, pericarditis, and peritonitis that manifest as congested blood capillaries and fibrinous layers deposited on the liver and heart [57,58,59]. Moreover, other gross lesions are frequently encountered with the systemic form of colibacillosis, such as an enlarged and congested spleen, pyelonephritis, polyarthritis, and salpingitis [15,27,60].

Alternatively, salpingitis and cellulitis are two frequently encountered localized forms of colibacillosis. Salpingitis could occur as a consequence of the systemic course of the infection or as an ascending infection from the cloaca to the oviduct, leading to contaminating the egg yolk, which could be exacerbated into egg peritonitis if the yolk is released into the coelomic cavity, resulting in inflammation of the peritoneum [60,61]. Salpingitis has a drastic effect on egg productivity in layers, and also can result in mortalities of early-life chicks [15,60,61]. On the other hand, cellulitis usually results from infection through injured skin, severely impacting carcass quality by subcutaneous lesions and leading to a high rate of carcass disposal at abattoirs [15,60,62]. It is worth noting that the newly hatched chicks could be infected via vertical transmission from diseased breeders or through contaminated eggshell, leading to omphalitis and high mortality rates during the first week after hatching [29,63,64,65]. The overall outcomes of avian colibacillosis, including the high mortality rates of chicks, the reduced performance and meat production of broilers, the reduced egg production of layers, and the increased rate of carcass condemnation at abattoirs, account for the significant economic loss of the poultry industry associated with the disease.

3. Virulence Factors

The virulence factors described in this section are those for which strong evidence for their role during APEC pathogenesis has been gained.

3.1. Adherence

The first step of the pathogenesis of an infection is the attachment of the pathogen to the epithelial cells at the specific site of infection, typically mediated by adhesins. These are membrane proteins located on the bacterial surface that recognize and bind to certain receptors on the host cells [66]. Through this adhesin–receptor interaction, bacteria can colonize different host tissues either to initiate an infection or persist as a part of the commensal microbiota [67]. APEC express diverse adhesins that support their infection process [68]. Among these, type 1 fimbriae are the most commonly expressed and play a key role in colonizing the chicken respiratory tract. This fimbrial structure is produced by the fim gene cluster, which encodes the fimA, fimC, fimD, fimF, fimG, and fimH subunits. These subunits assemble into a proteinaceous appendage on the outer membrane of the bacterial cell that facilitates bacterial attachment to specific host cell receptors [69].

Type 1 fimbriae are mannose-sensitive, requiring mannose-containing receptors for effective binding [68]. APEC strains lacking type 1 fimbria exhibit reduced adherence abilities [70]. These fimbriae enable APEC to attach to tracheal epithelial cells during the early stages of infection [68,71]. In addition to mediating adherence, type 1 fimbriae aid immune evasion. Specifically, the FimH adhesin at the fimbrial tip binds to CD48 receptors on phagocytes, promoting internalization into macrophages. Within macrophages, vesicles containing FimH-positive bacteria supress the release of free radicals preventing vesicle acidification and helping the bacteria to survive inside the phagocyte [72]. Furthermore, these fimbriae may contribute to the antimicrobial resistance of APEC by enhancing bacterial internalisation and persistence within macrophages [73].

APEC also express another fimbrial adhesin: the P fimbriae [74]. Encoded by the pap operon—a cluster of eleven genes located on a pathogenicity island on the bacterial chromosome—these structures feature the PapG adhesin, which binds to glycolipid receptors containing Galα(1–4)Gal residues [75]. While being commonly distributed in E. coli strains associated with urinary tract infection (UTI) in humans [76,77], pap operon genes have also been frequently identified in the pathogenic E. coli from poultry [78,79,80]. Deletion of these genes significantly attenuates APEC virulence compared to wildtype strains [81]. P fimbriae are not typically expressed by APEC in the upper respiratory tract compared to air sacs and lungs, which suggests the role of such fimbriae during the advanced stages of APEC infection [68].

3.2. Iron Acquisition Systems

Iron is an indispensable element for all living organisms, including bacteria, essential for cell composition, growth, multiplication, and metabolism [82,83]. Bound iron is usually present in host’s biological fluids either included in hemoglobin or bound to certain carriers such as transferrin [83,84]. In addition, in aerobic environments, iron is typically found in its oxidized ferric form, which has low solubility and therefore limits its availability [84]. Under the pressure imposed by the iron-restricted environment of the animal body, bacteria face the challenge of obtaining iron required for their survival. To overcome iron limitation, bacteria secrete small molecules called siderophores that chelate and solubilise iron to be available for bacterial use [85,86]. Siderophores are important for bacterial pathogenesis. Reduced virulence was reported with strains that had a defective siderophore production [87]. E. coli can secrete a variety of siderophores, including aerobactin, salmochelin, and yersiniabactin [86,88]. An operon of five genes (iucD, B, A, C, and iutA) typically harboured on the colV plasmid is responsible for aerobactin synthesis in E. coli [89,90,91].

An APEC strain individually knocked out of the aerobactin genes showed a reduction in pathogenicity evidenced by reduced colonization and competitive growth with the wildtype strain, which indicates the importance of the aerobactin siderophore for APEC virulence [92,93]. Yersiniabactin, another key siderophore, was initially identified in Yersinia spp. It is encoded on a high pathogenicity island (HPI) by seven genes, all required for the synthesis of the siderophore [94,95,96]. The most notable of these genes are the irp1 and irp2 genes [97,98]. Generally, the Yersinia HPI is associated with increased virulence in ExPEC [99,100]. Blocking the uptake of the yersiniabactin by deleting the gene responsible for its receptor from an ExPEC strain resulted in virulence attenuation [101]. Furthermore, deleting the core HPI gene (irp2) or the yersiniabactin receptor gene (fuyA) reduced the virulence of the APEC knockout strains evidenced by attenuated adherence compared to the wildtype [102]. Salmochelin is another siderophore secreted by E. coli, encoded by the iroBCDEN gene cluster and found on virulence plasmids of the ExPEC [103,104]. The iroN gene encodes the outer membrane receptor for the salmochelin siderophore [105]. This gene, along with other iron receptor genes, is highly prevalent in APEC [106,107]. The absence of iroC, iroD, or iroN genes impaired the virulence of an APEC O78 strain [108,109]. The iroN receptor protein on its own was found to enhance biofilm formation in ExPEC [110]. Comparative studies show that iron acquisition systems are more frequently detected in APEC strains than in commensal E. coli [111]. These systems are important for pathogenic E. coli to establish infection by providing a competitive advantage in iron-restricted environments [109]. The possession of more than one iron-acquisition system by APEC appears to potentiate the bacterial virulence and survival [79].

3.3. Increased Serum Survival

Due to the invasive nature of APEC, it is necessary for the bacteria to survive in chicken serum to be able to establish a generalized infection. One important factor reported to significantly increase APEC resistance to chicken serum is the increased serum survival protein, Iss [112,113,114]. Iss is an outer membrane protein encoded by the iss gene, typically located on the ColV plasmid [114,115,116]. Previous studies have reported the prevalence of the iss gene in E. coli strains isolated from septicaemic birds [117,118,119]. The gene has also been identified in other ExPEC strains including the uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) and newborn meningitis-causing E. coli (NMEC) [120,121]. In one-day-old chicks, the presence of the iss gene resulted in a 20-times increase in serum resistance compared with other isogenic strains lacking this gene [115,122]. Although the mechanism of action of the Iss protein in protecting APEC in serum is not fully understood, it has been reported that the Iss protein is required for the synthesis of the group 4 capsule that envelops the bacterial cell and protects its membrane from the action of the membrane attack complex (MAC), helping the bacteria to survive in the serum [114,123]. Given its role in virulence and its strong association with ExPEC, and particularly with APEC, the presence of the iss gene represents a reliable marker for APEC identification [124].

Other than the virulence factors already described in this section, several additional putative virulence genes have been identified, for which confirmed roles in pathogenesis are less well defined. However, these genes have proven valuable in diagnostic screening and in the differentiation of APEC isolates, as their prevalence suggests an association with pathogenesis rather than a confirmed causal role (see the Diagnosis Section 5 below). Further information on other virulence-associated genes can be found in ref. [31].

4. APEC Zoonosis

In the context of the One Health concept, understanding the dynamics of interspecies transmission of pathogens is crucial. Animals constitute a source of a wide range of human pathogens, including E. coli. For instance, it is well established that cattle are the reservoir of the enterohaemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) O157, a strain that causes severe illness in humans while remaining harmless to the bovine host [125]. Moreover, poultry is also suggested as a probable source of ExPEC infection in humans, either via direct contact with birds or consumption of contaminated chicken products [126]. This association is supported by cumulative evidence of similarity between APEC and human UPEC and NMEC strains. Early studies highlighted the overlap in serotypes and virulence genotypes among E. coli strains isolated from diseased birds and human clinical cases [127,128]. Moreover, a number of fecal strains from healthy chicken and their environment exhibited virulence profiles resembling both outbreak-associated APEC and human ExPEC strains, suggesting the poultry intestine and their environment as potential sources of APEC and human ExPEC infections [21].

Other studies touched on more discriminatory approaches such as phylogenetic analysis of APEC and human ExPEC based on MLST and PCR-based phylogeny. Such studies showed host independence of clonal clustering of the strains with phylogroups composed of poultry and human isolates sharing the same traits [129,130]. In addition, findings from phylogenetic studies directed the attention to certain sequence types or clonal complexes as of a significant zoonotic potential such as clonal complexes ST131, ST95, ST23, ST117, and ST45 [131,132,133,134]. Most of these prominent ExPEC sequence types have been detected in poultry meat, suggesting a possible route of transmission to humans through the food chain [135,136]. Notably, some human ExPEC strains sharing the same phylogenetic subclusters and nearly the same virulence factors as poultry strains showed lethality to one-day-old chicks [137,138]. Conversely, strains of poultry origin were pathogenic to mouse models and infective to human tissue culture, which supports their potential pathogenicity to humans [19,139,140,141,142,143].

Advanced genome sequencing technologies with extensive in silico analysis have enabled deeper investigations into the genetic relatedness of bacterial isolates, uncovering relationships that might be overlooked using the classical phylogenetic methods such as ordinary MLST. The first genome sequence of an APEC strain (O1:K1:H7) was completed by Johnson et al. and revealed a significant similarity to ExPEC genomes [144]. A core genome MLST (cgMLST) study analyzing 2547 alleles that constitute the core genome of E. coli strains under study instead of the usual seven housekeeping genes revealed the relatedness of the ST131 strains collected from different sources, including humans, chicken, and chicken products [145]. Even higher resolution is achieved through single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data. For instance, Pietsch et al. identified significant genomic similarity among three E. coli isolates—one from poultry and two from human patients—based on SNP comparisons [145]. Additionally, WGS has reinforced the zoonotic relevance of specific APEC sequence types such as ST131 [146,147], ST95 [148], and ST117 [149], which are increasingly associated with extraintestinal infections in humans. Although direct evidence linking APEC to human infection outbreaks remains unavailable, the growing body of research supports their zoonotic potential, resting on three main pillars: (a) shared characteristics between human and poultry isolates—including serotypes, virulence factors, and resistance genes; (b) demonstrated genetic relatedness through high-resolution genomic tools; and (c) cross-species infectivity shown in animal model experiments.

5. Diagnosis and Identification Scheme

Despite the well-characterized picture of the disease, identification of the APEC pathotype is always a complicated process due to the genetic diversity of the pathogen [150]. Traditionally, serotyping and virulence genotyping were used to identify APEC isolates [30,151]. Serotyping is based on identification of the somatic O-antigen either via PCR or specific antibodies. The use of serotyping for APEC identification stemmed from the observation that certain E. coli serotypes such as O78, O1, and O2 were the most prevalent among E. coli isolated obtained from diseased birds [112,152,153]. Besides serotyping, several studies aimed at linking APEC to certain virulence genotypes. Several virulence determinants are required for APEC to establish infection and cause pathology in the avian host [154]. Some of these factors are important for epithelial adhesion and others are related to iron acquisition and serum resistance [117,154,155].

However, the same pattern of virulence factors is not always present in all pathogenic strains associated with any one clinical manifestation [156,157]. Usually, variable combinations of genes are found, which complicates the consideration of a certain virulence gene or gene set as the definitive pathogenicity determinant [158,159,160,161,162]. Previous studies suggested combinations of 4 to 10 genes as indicative of the APEC genotype. Combinations of four genes (iss, tsh, iucC, and cvi) [163], five genes (hlyF, iss, iutA, ompT and iroN) [124], six genes (iss, iucD, hylF, ompT, iroN and iutA) [161], eight genes (astA, vat, iss, irp2, iucD, papC, tsh, and cva/cvi) [164], and ten genes (iss, iutA, cvaC, iroN, fyuA, irp2, sitA, tsh, ompT and hlyF) [165] were all suggested for the identification of APEC. Furthermore, a recent comprehensive review suggested a compilation of ten virulence determinants, e.g., iss, tsh, iroN, ompT, iutA, cvaC, hlyF, iucD, papG, and papC, as an identifier of the potential APEC pathotype [166]. It is worth noting that using any of the previous combinations as the exclusive indicator of the APEC genotype is inadequate. Many APEC isolates recovered from diseased birds were positive for none of the aforementioned genes [16]. Equally, many of those virulence genes were found in commensal isolates from healthy birds [156,162,167]. Those could be referred to as potentially virulent or opportunistic, which may cause an infection upon immune suppression by environmental stressors or any other factors [19,156]. This dilemma was discussed in a recent study conducted by Kazimierczak et al., who combined in silico virulence genotyping with an in ovo embryonic lethality test to verify the pathogenicity of the strain collection under the study [168]. Commensal strains that were categorized as non-pathogenic depending on the source and the original Clermont classification were found pathogenic after the in ovo embryonic lethality test was included. The study suggested three genes, i.e., iroC and hlyF and the wzx gene encoding the O antigen flippase of the O78 serotype, as predictors of the APEC pathotype. However, the test had low specificity (64.71%) [168].

Although PCR-based scanning of virulence genes is an easy and useful method for identifying APEC, most of these genes are plasmid-borne [169,170], which are mobilizable between bacteria, leading to fluctuating prevalence of these genes across bacterial populations, making it difficult to rely solely on them for accurate APEC identification. Also, it was reported that the pathogenicity of E. coli in chicken is irrespective of plasmid carriage and more related to clonal relatedness with certain lineages such as ST23, ST131, and ST117 are dominating the pathotype [171]. This, in turn, reflects the necessity of a deeper investigation of the genetic features associated with APEC based on more stable and conserved chromosomal markers. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) technologies offer a high-throughput approach for analyzing large numbers of APEC isolates, providing comprehensive data on serotypes, sequence types, antimicrobial resistance genes, virulence factors, and phylogenetic relationships [172]. This approach has greatly enhanced our understanding of the genetic diversity among APEC serotypes and sequence types commonly associated with clinical disease [173,174,175].

Analysis of WGS data derived from APEC O78 isolates allowed the separation of this serotype into two phylogenetically distinct lineages, i.e., ST23 clonal complex and ST117, that belong to two different phylogroups, i.e., C and G respectively [30]. This underscores the high resolution of WGS technologies, enabling deeper identification of APEC beyond traditional serotyping [30]. Moreover, genomic data allowed for the clustering of APEC based on single nucleotide differences—i.e., single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)—which further subdivided phylogenetic clusters into subclusters [176]. Despite the deeper clustering of APEC provided via WGS, the association of a certain virulence profile with a specific phylogroup or sequence type or even with a certain lesion—such as acute or chronic salpingitis—remains, as yet, still unobtainable [30,170,177]. For instance, a study that linked virulence factors to certain phylogroups such as B1 and A [178] was contradicted by another study conducted by Chen et al. that associated virulence genes with different phylogroups such as B2, D, and F [175]. Therefore, a more precise comparison of E. coli WGS data from chickens—beyond standard phylogenetic analysis and presence/absence screening of virulence determinants—could aid in identifying characteristic pathogenic traits. An extensive genome-wide association study (GWAS) utilized the pangenome of E. coli isolated from healthy and symptomatic birds to investigate allelic variation in core and accessory genes, independent of their clonal relatedness [179]. Interestingly, the study reported the shortage of phylogeny and plasmid-associated gene screening for pathotype identification and suggested, via the GWAS approach, a panel of 143 genes involved in different functions in E. coli, such as heat shock response, lipopolysaccharide synthesis, metabolism, antimicrobial resistance, and toxicity, as pathogenicity-associated genes [179]. This highlights the substantial contribution of WGS studies to understand APEC and expands our vision about the definitive characteristics of the pathogen beyond its virulome.

6. Control Strategies of APEC

Due to the significant health and economic impact of APEC, various control strategies have been deployed to control the pathogen and limit the burdens of the disease. Managemental measures, vaccination, antibiotics, and antimicrobial alternatives such as probiotics and bacteriophages are used to control, with varying degrees of success, the disease on poultry farms.

6.1. Management and Biosecurity Measures

As a first step in reducing the incidence of colibacillosis on poultry farms, addressing the predisposing factors of the disease is essential. These factors may include biological causes, such as primary viral infections like infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) [180], or environmental stressors such as elevated ammonia levels [181]. Both types of factors can damage the ciliated epithelium of the chicken’s respiratory tract, making it a liable entry for APEC [32,33]. Maintaining good ventilation, regular change of the litter, consistent removal of the debris, and adjusting the bird density can help keep the ammonia level inside the poultry house low and consequently protect the integrity of the bird’s respiratory epithelium [182]. Vaccinating the birds against viral diseases such as IBV can protect the bird against the primary viral infections and lower the probability of any secondary bacterial infections, including APEC. In addition, proper nutrition enhances the bird’s overall health, boosts immunity, potentiates the resistance of the bird against infection, and improves the clearance of the pathogen from the body [183].

APEC is a major cause of early chick mortality, often resulting from vertical transmission of the pathogen to chicken embryos upon oviduct infection or via contaminated eggshell. Several measures can be implemented to prevent both routes of the vertical transmission of APEC, such as raising breeds that are genetically more immune to APEC or ensuring high eggshell quality [28,31]. Good eggshell hygiene could be maintained by minimizing the percentage of floor eggs, which are more prone to contamination, as well as through proper cleaning and disinfection of the eggs and general decontamination and sanitization of the poultry house [28,31]. Establishing a proper biosafety system to restrict the unnecessary entry of vehicles and workers to the poultry house, besides the control of rodents, insects, and wild birds, can further reduce the risk of contaminating the poultry premises [23,29].

6.2. Antibiotics

Antibiotics form an essential control strategy for bacterial infections in the livestock [184]. They are used to treat a broad spectrum of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including APEC. Antibiotics can be applied in feed or drinking water or through parenteral administration—such as subcutaneous or intramuscular—for larger animals [185]. Several antimicrobial agents from various classes have been used to treat and control avian colibacillosis. These include aminoglycosides (e.g., gentamycin and neomycin), penicillins (ampicillin and amoxicillin), tetracyclines, sulfonamides, quinolones (e.g., enrofloxacin), cephalosporins (e.g., ceftiofur), phenicols (e.g., chloramphenicol), lincosamides (e.g., lincomycin), macrolides (e.g., erythromycin), and polymexin (e.g., colistin) [31,186]. Previous studies discussed the efficacy of some of these antibiotics for curing APEC and suggested quinolones (e.g., enrofloxacin and norofloxacin), tetracyclines (e.g., oxytetracycline and doxycycline), and sulfonamides (e.g., sulfadimethoxin) as effective candidates for controlling the disease [187,188,189,190]. However, the uncontrolled use of antibiotics in animal production has resulted in a mounting resistance to antimicrobials within microbial communities [191]. On poultry farms antibiotics are extensively used as a prophylactic measure to prevent infections and promote growth despite the legislation to reduce the use of the antimicrobial growth promoters (AGPs) [192,193,194]. This, in turn, has contributed to the spread of resistance on poultry farms [195]. APEC strains with multidrug resistant profiles were frequently reported in the cases of avian colibacillosis [80,161,196,197,198].

The resistance observed in APEC is against multiple antibiotics such as penicillin, cephalosporins, tetracyclines, quinolones and aminoglycosides [199,200]. The multidrug resistant phenotype of APEC is indicative of a genome rich in resistance determinants. For instance, genes conferring the resistance to quinolones (e.g., qnrA, qnrB, and qnrS), tetracycline (e.g., tetA and tetB), sulfonamides (e.g., sul1 and sul2), aminoglycosides (e.g., aadA), and the β-Lactam antibiotics (e.g., blaTEM) are prevalent in E. coli isolated from both healthy and diseased chickens [31,152,201,202,203,204]. Importantly, antibiotic resistance genes are usually carried on mobile genetic elements (MGEs) such as plasmids, insertion sequences, and transposons [205,206]. The association of antibiotic resistance with various plasmid replicons such as incP, incI1, incA/C, and incFI has been previously reported in APEC [207,208]. IncF plasmids such as FIA, FIB, and FIC were previously linked to quinolone resistance in APEC [209]. Furthermore, the class 1 and 2 integrons have been associated with multiple antibiotic resistance genes such as trimethoprim (dfrA), streptomycin (aadA), and erythromycin (ereA), aminoglycosides, and sulfonamides in E. coli isolated from healthy and diseased birds [210,211,212,213].

The association between antimicrobial resistance and MGEs promotes the horizontal spread of the resistance among bacteria [214,215]. It also could exacerbate the infection in case resistance genes and virulence determinants were genetically linked, leading to the potential spread of both resistant and virulent strains [117,216,217]. Hence, the daunting antimicrobial resistance in poultry production imposes a serious challenge to the antibiotics as a control strategy of the disease on poultry farms by drastically decreasing the efficacy of the antibiotics, leading not only to the failure of the treatment but also the selection for resistant pathogens within the microbial populations [216,218,219]. This provides the drive toward alternative and innovative solutions.

6.3. Phytochemicals

Phytochemicals, also known as phytobiotics, are bioactive compounds extracted from plants and supplied in animal feeds to enhance productivity [220]. Due to their antimicrobial activity, they have been suggested as promising alternatives to antibiotics for tackling antibiotic-resistant bacteria [221,222]. Around 1340 plant species with known antimicrobial activity are available [223]. Various antimicrobial compounds from plants such as thyme, chicory, coriander, aloe vera, and turmeric have been incorporated into production of livestock including poultry, pigs, and ruminants as alternatives to antibiotics and for promoting growth [224,225]. Phytochemicals are classified into various categories based on their chemical structures and properties, including alkaloids, flavonoids, phenolic compounds, saponins, and essential oils (EOs) [226]. Extensive efforts have been made to isolate and purify these bioactive compounds to enable their proper identification and application [227]. They exert their antimicrobial effects through various mechanisms, including inhibition of DNA supercoiling, interference with protein synthesis and efflux pump activity, disruption of bacterial cell membranes, and interaction with key bacterial enzymes [222].

Phytochemicals have been used frequently for the treatment of multiple avian pathogens such as APEC [228,229], Salmonella [230], Campylobacter [231], Clostridia [232], Staphylococcus aureus [233,234], and Coccidia [235]. Despite their benefits in controlling pathogens and promoting animal growth, the use of phytochemicals in animal production faces several critical challenges. One major hurdle is the poor understanding of their pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and biotransformation, which complicates their usage and commercialization [236,237,238]. Other limitations relate to animal performance; for instance, when administered at high concentrations, some phytochemicals may exert an anti-nutritional effect represented by decreasing the digestion of certain nutrients and limiting the availability and absorption of some trace elements like zinc and iron [239,240,241]. Furthermore, some EOs can adversely affect the palatability of the animal ration, leading to reducing feed intake and lowering the performance [242]. Also, the use of EOs can be economically burdensome due to the difficulty in determining their effective dosage in animal feed, largely attributable to their highly volatile nature [243,244], and their high minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), which decreases their cost-effectiveness [245]. The potential toxicity of phytochemicals should be considered carefully [246,247,248], and a precise qualitative and quantitative analysis of the plants and their bioactive compounds is a must to ensure their safety before use [249]. However, the complex composition of phytochemicals poses some difficulties for the systematic evaluation of their safety and efficacy [245].

6.4. Vaccines

Vaccines have always been a very effective immunological means of controlling microbial infections throughout the animal production process [250]. In poultry, various kinds of vaccines, including killed, live-attenuated, and subunit vaccines, are available for controlling bacterial and viral diseases [251]. The live-attenuated vaccines are based on introducing well-characterized mutations into the genome of the wildtype strain, rendering it unfit for initiating an infection [252,253]. On the other hand, the subunit vaccine uses a specific part of the pathogen, typically a certain purified antigen, which is delivered via various carriers such as liposomes [254]. Delivering this antigenic molecule via another attenuated bacterium is referred to as recombinant vaccine technology [254].

Continuous efforts have been ongoing to find a good vaccine candidate for controlling avian colibacillosis [255,256,257,258,259,260,261]. Table 1 summarizes some of the experimental attempts of testing several types of potential APEC vaccines in poultry.

A smart technology that has been tested for immunizing chicken against colibacillosis is the bacterial ghost vaccine. This type of vaccine is based on emptying the content of the bacterial cell through a pore created in the cell membrane. This process is accomplished through the controlled expression of the lysis gene E of the phage φX174 and retaining the cell membrane intact with its surface antigens [262,263]. As a result, ghost vaccines combine the advantages of strong immunogenicity because they keep the membrane-associated epitopes and safety because they are unable to replicate [263]. Either an APEC or a non-APEC strain (e.g., lab strain) exogenously expressing specific APEC proteins can be used for ghost vaccine preparation [264,265]. Although most vaccine types share the advantage of being highly immunogenic and able to stimulate humoral immunity, important challenges need to be addressed when they are used. These challenges could be summarized in three key aspects: (a) protection, (b) safety, and (c) applicability. Regarding protection, a major limitation that faces most potential vaccine candidates is their failure to confer cross-protection against heterologous APEC strains or serotypes [256,259,266]. Therefore, autogenous vaccines prepared from the respective field strains may be more effective; however, they impose restrictions on the vaccine’s applicability and production process [259,267,268].

Despite some previous studies reporting either failed or weak protection in the vaccinated birds [269,270,271], successful vaccines develop immunity in a few-week period of time during which the birds are liable to infection especially during the first few days after hatching [260,261,272]. This, in turn, underscores the importance of the passive immunity transferred from the breeder hens to the hatchlings in protecting chicks during their early life [273]. However, failure of maternal immunity transfer to the offspring or the inability to protect the newly hatched chicks by the vertically transmitted antibodies may occur [260,261,268,273]. The safety of the vaccine exemplified by the reversion of the vaccine avirulent or live-attenuated strain to the virulent phenotype and the side effects from large vaccination doses must be considered carefully [255,256,274,275]. In terms of vaccine applicability, mass vaccination of the entire flock requires an easy administration route, such as spray or in drinking water. However, some vaccines could be more effective when administered through a method that is not very practical for mass vaccination programs such as injection or better still in ovo inoculation [265]. Furthermore, many vaccines may require a booster dose to elicit a strong immune response, which imposes a financial burden on the vaccination program.

Finally, despite the numerous attempts to develop a potent avian colibacillosis vaccine, only a few candidates have reached the market and become commercially available, such as the ∆aroA live-attenuated vaccine (Poulvac® E. coli, Zoetis, U.S.) [276], the inactivated vaccine (Nobilis E. coli Inac., MSD Animal health, U.S.) [277], and the Δcrp live-attenuated vaccine (Gall N tect CBL, Nisseiken Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) [278]. These vaccines are based on the APEC O78 serotype, and although they have been proven to be effective and safe, they provide weak immunity against heterologous serotypes. However, the most studied commercial vaccine, i.e., the ∆aroA Poulvac vaccine, showed variable results regarding cross-protection [279,280,281,282]. It is worth noting that the failure to protect offspring via passive immunity from parents vaccinated with Nobilis or Poulvac vaccines has been previously reported [268,283]. Collectively, the shortage of potent commercial vaccines against avian colibacillosis and the inefficient cross-protection against APEC serotypes other than the progenitor strains of the vaccines represent the primary challenges that face APEC control via vaccination.

Table 1.

Vaccine trials to control APEC.

Table 1.

Vaccine trials to control APEC.

| Inactivated/Killed vaccine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine strain serotype | Inactivation | Vaccination route | Bird | Reference |

| APEC (strain KAI-2/O78) | Formalin inactivated | Eye drop and coarse spray | Chicken | [257] |

| Monovalent (E. coli O78 or O1) | Formalin inactivated | Subcutaneous | Chicken | [267] |

| Multivalent (O18, O78 and O111) | Unclear | Intramuscular | Chicken | [259] |

| O157 | Formalin inactivated | Subcutaneous | Chicken | [272] |

| Bivalent (E. coli 19-381 and 19-383-M1) | Formaldehyde inactivated | Intramuscular | Chicken | [273] |

| Live-attenuated vaccine | ||||

| Vaccine strain serotype | Mutation | Vaccination route | Bird | Reference |

| O2 | carAB operon mutation | Oral | Turkeys | [284] |

| O78 and O2 | ∆cya and ∆cya∆crp | - | [255] | |

| O78 O2 | ∆cya∆crp ∆cya∆crp | Spray | Chicken | [269] |

| O78 | ∆galE, ∆purA, and ∆aroA (single mutation) | Spray | Chicken | [256] |

| O78 | ∆aroA | Spray and oral | Chicken | [266] |

| O78 | Crp deletion | Spray, eye drop, and in ovo | Chicken | [278] |

| Subunit vaccine | ||||

| Strain serotype | Antigen | Route | Bird | reference |

| O1 | Pili protein | Subcutaneous | Chicken | [285] |

| O1, O2, and O78 | Pili proteins of the three serotypes (Multivalent) | Subcutaneous | Chicken | [286] |

| Unclear | Sugar-binding domain of FimH (FimH156) | Intramuscular or intranasal | Chicken | [270] |

| Unclear | Sugar-binding domain of PapGII (PapGII196) | Intramuscular | Chicken | [271] |

| Unclear | Iss protein fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST-iss) | Subcutaneous | Chicken | [287] |

| Unclear | Liposome-encapsulated mixture of rough LPSs of core types R1, R2, R3 and R4. | Intramuscular | Chicken | [288] |

| Unclear | Iss protein, fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST-iss) | intramuscular | Chicken | [274] |

| APEC O78 and NEMC O18 | Recombinant antigens (rAg) including (EtsC, OmpA, OmpT, and TraT) | Subcutaneous | Chicken | [48] |

| Unclear | Enterobactin | Subcutaneous | Chicken | [260,261] |

| Recombinant vaccine | ||||

| Recombinant strain | Exogenous genes of E. coli | Route | Bird | Reference |

| ∆lon ∆cpxR ∆asdA16 S. Typhimurium (JOL912) | P-fimbriae (papA and papG) Aerobactin receptor (iutA) CS31A surface antigen (clpG) | Orally | Chicken | [275] |

| S. Typhimurium, ∆cya-27, ∆crp-27, ∆asdA16 | Ecp operon encoding E. coli pilus | Orally | Chicken | [289] |

| Lactobacillus saerimneri M-11 | Fimbrial subunit A (fimA) Outer-membrane protein C (ompC) | Orally | Chicken | [290] |

6.5. Bacteriophages

Bacteriophages (commonly referred to as phages or “bacteria eaters”) are viruses that specifically infect and lyse bacterial cells [291]. They were early recognized as a potential bactericidal tool for curing bacterial infections [292]. A bacteriophage could be either a lytic or lysogenic type. A lytic or virulent bacteriophage injects its genetic material into the bacterial cell, hijacks the cell, and replicates until the cell finally ruptures releasing progeny [293,294]. Conversely, a lysogenic or temperate bacteriophage integrates its genetic material into the bacterial chromosome and replicates concurrently with the bacterial genome without any lytic activity on the bacterial cell [293,294]. Due to their bactericidal nature, lytic bacteriophages are suitable as an antimicrobial solution for bacterial control [295], and have been applied for curing bacterial infections in humans [296,297], farm animals [298], aquaculture [299], and plants [300]. In poultry production, several trials have been conducted using bacteriophage for the control of significant poultry pathogens such as Salmonella and Campylobacter [301]. In most trials, one bacteriophage or a mixture of different bacteriophages (i.e., phage cocktail) was administered orally, resulting in a significant reduction in the viable counts of the target bacteria [301]. Considering avian colibacillosis, bacteriophage administration to chicks via different routes (i.e., intramuscular and intratracheal) resulted in reduction of various serotypes (i.e., O1, O2 and O78) of APEC [302,303,304]. The application of a phage cocktail has also showed successful control of APEC in a more efficient way than single-phage treatments [304]. Furthermore, applying bacteriophages to the litter or via spraying on hatching eggs could be used as a prophylactic measure to prevent colibacillosis as it helped reduce the mortality rate and enhance the body weight of the broiler chicks [305].

Bacteriophage therapy presents severe limitations: first, the high specificity of bacteriophage adsorption to bacteria, which results in targeting only one single species or a subset of susceptible bacterial strains within a single species [291,306]. As a consequence, precise diagnosis of the causative bacterial agent of the infection and its susceptibility is essential to selecting a suitable bacteriophage or bacteriophage cocktail, although even this is not a guarantee for efficiency [291,307]. A second important limitation is the rapid development of phage resistance in bacteria [308,309]. Mutations that block or alter the bacteriophage receptor, preventing the adsorption process and bacteriophage DNA restriction, which cuts and inactivates the bacteriophage genome, are two resistance mechanisms that render bacteriophage treatment ineffective [310,311]. A further consideration is the role of bacteriophages in transduction and genome reassortment that could contribute to the spread of antimicrobial resistance and virulence among bacterial strains in the animal [312,313,314].

6.6. Probiotics

Probiotics, or diet-fed microbials (DFMs), are non-pathogenic bacteria that, when administered to the animal host, exert a beneficial effect on its health [315]. Various bacterial species such as Bifidobacterium spp., Streptococcus spp., Bacillus spp., Lactococcus spp., and Lactobacillus spp., as well as yeasts, have been exploited as probiotics for animal production [316]. Probiotics are claimed to offer multiple benefits in farmed animal production, such as enhancing growth performance, improving host immunity, modulating the gut microbiome, and controlling pathogenic bacteria [317]. For poultry, birds that received DFM such as Bacillus subtilis or Lactobacillus spp. showed an improved immune response, represented by enhanced IgA secretion into the intestine and modulating intraepithelial lymphocytes (e.g., CD4 cells) [318]. Probiotic administration to newly hatched chicks introduces beneficial changes to the gut microbiome by promoting beneficial taxa and limiting harmful ones in the bird’s gut [319]. These diet-fed beneficial bacteria can compete with pathogenic strains, preventing them from colonizing the epithelial surfaces through competitive exclusion [320,321]. The inclusion of Bacillus subtilis or Lactobacillus-based probiotics in poultry feed has been shown to reduce the incidence of some bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella spp. and Clostridium perfringens [322,323,324]. Regarding APEC control, the probiotic candidate Enterococcus faecalis-1, administered to broiler chicken in drinking water, enhanced the immune response, improved growth, and reduced invasion by APEC O78 in the challenged birds [325]. Another probiotic mix containing Bacillus subtilis MORI 91, Clostridium butyricum M7, and Lactobacillus plantarum K34 also demonstrated a protective effect in the birds challenged with APEC O78 [326]. The administration of commercially available probiotics, such as Aviguard and Gro2MAX, reduced transmission and excretion of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli in treated chicks [327,328,329].

A critical challenge of probiotics usage is their potential to acquire and disseminate antimicrobial resistance [330]. Despite their avirulent genotype, strains of the probiotic species Enterococcus faecium, isolated from various commercial products intended for animal usage in the US, exhibited a multidrug-resistant phenotype to medically important antibiotics [331]. This consequently highlights the potential hazards associated with the probiotics in case successful transfer of resistance from a probiotic strain to a pathogenic one took place rendering them difficult to treat. Notably, balancing the use of both probiotics and antibiotics is critical, as the administration of enrofloxacin following the commercial probiotic Aviguard was shown to negate its beneficial effect and restore the enrofloxacin-resistant E. coli population in the treated chickens [332]. The safety of probiotics is also critical. The potential of a probiotic to induce infection, allergic reaction, or adverse metabolic effect is a significant risk that must be pondered carefully [330]. A study conducted in China to assess the safety of animal-use commercially available probiotics found that one-third of the 92 products tested were contaminated with life-threatening pathogens such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, and one of them contained an anthrax toxin-positive Bacillus cereus strain [333]. Hence, ensuring the safety of the proper probiotic strain is crucial [320,334]. There are many claims made for the efficacy of probiotics and, whilst in some cases there is evidence for marginal reduction of gastrointestinal pathogens, their antimicrobial effects are largely strain-specific, and the underlying mechanisms of action remain poorly understood [335].

6.7. Prospective APEC Control

6.7.1. Antimicrobial Nanoparticles

Nanoparticles are extremely small, with three nanometer-scale (1–100 nm) dimensions, and exhibit physical, chemical, and biological properties distinct from their bulk counterparts [336]. Based on their source, nanoparticles can be classified into two main types: organic and inorganic. Organic nanoparticles, such as ferritin and liposomes, come from carbon-based sources. In contrast, inorganic nanoparticles do not contain carbon such as metal-based and metal oxide-based nanoparticles [337]. Many metals such as aluminum, gold, silver, lead, copper, and iron are involved in the synthesis of both metal and metal oxide nanoparticles. The method used for producing nanoparticles varies depending on their type. However, in general, two main approaches are commonly considered: (a) the top-down approach and (b) the bottom-up approach [338]. In the top-down approach, nanoparticles are produced by breaking down bulk material into smaller particles until the desired nanoscale size is achieved. In contrast, the bottom-up approach involves building up the nanoparticles by assembling simpler atomic or molecular building blocks [339].

Either as vehicles for antibiotic delivery or as antimicrobial agents themselves, nanoparticles stand out as a promising solution in the fight against multidrug resistant bacteria [340]. Nanoparticles as drug carriers help overcome the pharmacokinetic/dynamic hurdles that could affect the efficacy of the antibiotic. For instance, nanocarriers could potentiate the ability of an antibiotic to cross biological barriers such as the blood–brain barrier and cell membranes, allowing the antibiotic to reach resistant intracellular infections such as Salmonella, Listeria, and Brucella [341]. The minute size of nanoparticles allows their efficient entry to the target cell via phagocytosis and endocytosis [342]. In addition, nanoparticles such as liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles improve the bioavailability of the drug by enhancing its solubility and prolonging its systemic circulation to achieve the maximum effect [343]. They also protect the antibiotic against enzymatic degradation, which enhances the efficacy of the antibiotic and reduces the dose required to exert an effect [344]. The aforementioned advantages encouraged scientists to use antibiotic-loaded nanoparticles for the treatment of many infectious pathogens such as E. coli, Pseudomonas, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Staphylococcus aureus [345].

Interestingly, nanoparticles could also be applied as antimicrobials on their own without requiring antibiotics to be conjugated. Generally, they exert their antimicrobial effect either by causing physical damage to cell membrane or changing the cellular chemistry, rendering it toxic to the bacterial cell [346,347]. The physicochemical characteristics of nanoparticles potentiate their role as antimicrobial agents [348]. In terms of physical characteristics, the size and shape of nanoparticles affect their antimicrobial activity. Previous reports discussed the superior antimicrobial activity of small, spherical nanoparticles compared to the triangular or rod-shaped ones [349,350]. The enhanced antimicrobial effect of these nanospheres is likely due to their increased surface area compared to other shapes, which fortifies their reactivity, release of toxic ions, attaching to bacterial cell membrane, penetration of the cell, and damaging of the DNA [349,350]. Furthermore, others reported that anisotropic nanoparticles with sharp edges are more able to penetrate the bacterial cell membrane, leading to cell rupture and release of content, and thus have a stronger bactericidal activity than nanoparticles with rounded edges [351]. Surface charge is another key factor influencing antimicrobial activity. Positively charged nanoparticles are particularly effective against Gram-negative bacteria, as they readily interact with the negatively charged bacterial membranes, leading to membrane disruption and bacterial death [352,353]. Additionally, the chemical composition of nanoparticles contributes to their bactericidal effect. Metal-based nanoparticles can actively release toxic metal ions within bacterial cells [353]. Once inside, they also generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anions, and hydroxyl radicals. These ROS, along with the released metal ions, cause DNA damage and disrupt essential enzymatic functions, ultimately leading to bacterial cell death [347,354,355]. Metal and metal oxide nanoparticles have been extensively studied for their effectiveness against a wide range of resistant pathogens, including Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli, Salmonella, Klebsiella, and Campylobacter [356,357,358,359,360], as well as Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium spp. [361,362,363]. The metal nanoparticles are effective individually; however, combinations of more than one type of metal nanoparticles exhibited an enhanced antimicrobial effect due to the synergism between them [364,365].

Although nanoparticles provide a promising solution as antimicrobials and antibiotic delivery vehicles, challenges that might delay the progress in this field need to be fully understood. As living organisms with adaptive capabilities, bacteria have managed to develop resistance against some antimicrobial nanoparticles [366]. Several mechanisms have been discussed that help the bacteria to resist the antimicrobial effect of nanoparticles, primarily by decreasing the entry or increasing the exit of the nanoparticles in and out of the bacterial cell. Reducing the numbers of porin molecules on the bacterial surface, especially OmpF, is one strategy adopted by bacteria to decrease the entry of small nanoparticles into the cell [367]. Furthermore, overexpression of the flagellin protein forms a matrix around the bacterial cell that aggregates the nanoparticles and prevents their contact with the cell membrane [367]. Sublethal doses of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles can stimulate the upregulation of efflux pumps which expel the metal and metal oxide ions out of the bacterial cell before killing it [368]. Therefore, ongoing research is essential to deepen our understanding of mechanisms of bacterial resistance to nanoparticles, which is critical for developing effective strategies to overcome this challenge. Conjugating the NPs with natural extracts could help suppress the mechanisms of bacterial resistance to NPs, thereby restoring their antimicrobial efficacy. For example, the pomegranate rind extract has been shown to suppress bacterial flagellin and restore the bacterial sensitivity to silver NPs [366].

Another significant challenge in applying nanoparticles as antimicrobials is their potential toxicity to non-target organisms, including beneficial microbiota and eukaryotic host cells. The mechanisms that make NPs effective against pathogens—such as ROS generation—may also harm other biological systems. For example, ROS produced by metal-based NPs can induce oxidative stress in eukaryotic cells, leading to DNA damage and destruction of organelles [369,370,371]. In vivo studies have shown that oral administration of NPs in mice can disrupt gut microbiota, causing dysbiosis, promoting the growth of opportunistic pathogens, and triggering intestinal inflammation [372,373]. These findings highlight the need for comprehensive safety assessment of NPs. With the growing production and widespread application of NPs, their potential environmental burden warrants serious consideration. Nanoparticles can enter the environment at various stages of their life cycle—during production, usage, and disposal—leading to contamination of soil and water [374]. This highlights the need for a comprehensive understanding of their environmental fate, impact, and the development of standardized methods for their detection and quantification. Once released, nanoparticles may persist in the environment or undergo various transformations, such as sulfidation, aggregation, sedimentation, dissolution, and adsorption, all of which can significantly influence their fate and toxicity [375,376]. While notable progress has been made in the risk assessment of nanoparticles, further research is essential to unravel the mechanisms of their toxicity in both humans and animals, as well as their interactions with environmental matrices. Such understanding is vital for ensuring the safe and sustainable application of these promising antimicrobial agents.

6.7.2. Enzybiotics (Endolysins)

Enzybiotics are enzymes capable of killing bacteria and thus act as antibiotics. They are primarily phage-encoded enzymes, used by bacteriophages during the late stage of their lytic cycle to lyse the bacterial cell and release the newly formed progeny [377,378]. The model enzybiotics are endolysins that act by digesting the peptidoglycan layer of the bacterial cell wall [379]. During the phage infection cycle, phage particles enter the bacterial cell, replicate, and ultimately burst the cell releasing more phage particles to infect neighboring bacterial cells. Endolysins play a crucial role in the final stage by intensely degrading the peptidoglycan layer, thereby perforating the cell wall resulting in osmotic rupture [380]. There are two different types of endolysins to adapt targeting different types of bacterial membranes: Gram-negative-targeting endolysins and Gram-positive-targeting endolysins [381]. The Gram positive-targeting endolysins typically consist of two domains connected together by a flexible linker. One domain at the C-terminal of the polypeptide chain acting as a cell wall binding domain (CBD), and the other at the N-terminal which is the catalytic domain or the enzymatic activity domain (EAD) [382,383]. On the other hand, most Gram negative-targeting endolysins often comprise only one globular catalytic domain [382,383]. Endolysins act on the peptidoglycan layer of the bacterial cell wall via different mechanisms, depending on the activity of their EAD domain. They can function as glycosidases, amidases, or endopeptidases—respectively breaking the glycosidic bond between residues of the glycan chain, the amide bond between the glycan chain and the peptide side chain, or the peptide bond between adjacent peptide side chains [384,385]. Thus, they have been exploited as promising next-generation antibiotics in the fight against the antimicrobial resistance [386]. A plethora of studies have demonstrated the potency of bacteriophage endolysins against a broad spectrum of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria affecting both animals and humans [387]. Among Gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus anthracis, and Streptococcus spp., such as S. agalactia, S. pneumoniae, and S. suis have shown susceptibility to endolysin-based treatments in animal models [388]. The efficacy of the endolysins against these pathogens was represented by lowering bacterial loads and improving survival rates of the treated animals [388]. Moreover, several Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were also susceptible to the antimicrobial activity of endolysins [389].

Endolysins, as antimicrobials, are considered superior to bacteriophages in terms of both activity spectrum and speed of action [390]. However, the most significant advantage of endolysins over bacteriophages is the lower probability of bacteria to develop resistance to endolysins than to bacteriophages [390,391,392]. This advantage is likely attributed to the cell wall binding domain (CBD) of endolysins, which specifically recognizes and binds to highly conserved and essential epitopes within the bacterial cell wall. Mutations in these regions are of low chance, as they would compromise bacterial viability [393,394]. This prevented the bacteria cultured on agar plates with low concentrations of endolysins from developing resistant clones even after several passages [393]. Therefore, the low propensity for resistance development makes endolysins particularly promising antimicrobials compared to bacteriophages and conventional antibiotics in the fight against resistant pathogens. Despite their advantages, endolysins have certain limitations. Due to their peptidoglycan-targeting mode of action, their bactericidal efficacy depends on the structural characteristics of the target bacteria. In the case of Gram-positive bacteria, the bacterial interface with the environment is an outer peptidoglycan layer, readily accessible to endolysins, rendering these bacteria easy targets for lysis. On the other hand, Gram-negative bacteria have an outer glycolipid membrane that hinders the accessibility of endolysins to the underlying peptidoglycan layer, thereby reducing their efficacy [395,396]. Consequently, only a limited number of endolysins with an intrinsic ability to lyse Gram-negative bacteria are available [389,396,397]. This presents a challenge either to find new endolysins that are naturally effective against Gram-negative bacteria or to develop strategies to make endolysins more penetrative.

One approach is combining endolysins with a membrane permeabilizer such as EDTA [398]. However, in some cases, the endolysin could counteract the effect of the permeabilizer as with Vibrio parahaemolyticus, where the bacterium used the proteinaceous endolysin as a nutritive substrate to boost its growth after the effect of the permeabilizer [399]. Another strategy to overcome the limitation in Gram-negative bacterial targeting by endolysins is via molecular engineering of the wildtype enzymes “Artilysins” [400,401]. For example, fusing endolysins with permeabilizer moieties, such as the polycationic nonapeptide (PCNP) or the sensitizer peptide KL-L9P, can disrupt the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. This allows the endolysins to reach the peptidoglycan layer, enhancing their ability to access and lyse the bacterial cell [402,403]. These engineered endolysins showed improved efficacies against multiple Gram-negative bacteria despite the extra effort required for their engineering [404]. Moreover, the continuous in vitro evolution of endolysins via molecular engineering produced enzymes that can target intracellular pathogens [405,406].

Despite the efficiency of such engineered endolysins, they raise a concern about the eukaryotic cell interaction potential, i.e., cell toxicity. In addition, being of a proteinaceous nature, the immunogenicity and anaphylaxis potential of endolysins are always questionable, especially when seeking the control of systemic infections that require administration of the enzymes in the circulation. Some preclinical studies assured the safety of endolysins in terms of general toxicity and allergenicity [407,408,409]. However, the expanding arsenal of endolysins necessitates further studies to ensure their safety. Another aspect of the antimicrobial endolysins’ application is their short half-life in the circulation ranging from minutes to hours due to lysosomal degradation and kidney excretion [410]. This short half-life imposes further challenges to both application and production of endolysins, as it requires booster dosing to achieve an effect as well as high concentrations of the protein in the used formulation. Consequently, this increases the chance of side effects of multiple doses, reduces the stability of the protein in the formulation, and reduces cost-effectiveness [383,395,410]. Extensive research has been conducted to improve the characteristics of endolysins and prolong their serum half-life with promising results [411,412].

Although endolysins constitute a very promising solution to control the dilemma of antimicrobial resistance, a few products have reached the market—mainly as feed additives for veterinary use, such as FORC3 and Axitan. This limited commercialization could be attributed to several unresolved challenges, including difficulties in large-scale production, formulation stability, delivery methods, and the complex regulatory pathways for approval of biologically derived antimicrobials. Addressing these hurdles is critical to translate laboratory successes into clinically and commercially viable therapies.

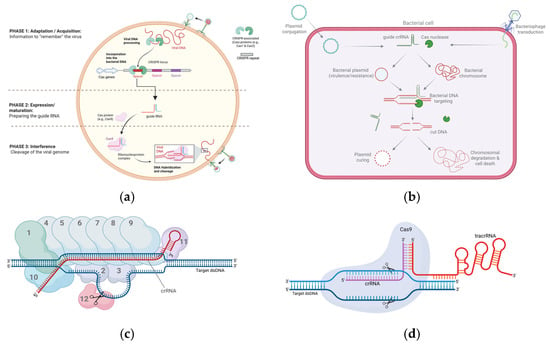

6.7.3. CRISPR-Based Antimicrobials

Bacteria have evolved different defense mechanisms to protect themselves against mobile genetic elements from the surrounding environment especially bacteriophages. The most recently described system of defense is CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats), an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes used to inactivate foreign genetic material that enters the bacterial cell [413,414]. CRISPR is an array of short, repeated DNA segments called CRISPR repeats separated from each other at regular intervals by variable sequences called spacers. Such arrays have been identified in the genomes of most archaea and nearly half of the known bacterial species [415,416]. The CRISPR-defense response consists of three key stages: (A) adaptation of the system by incorporating pieces from the invading genetic material known as spacers into the CRISPR array, effectively updating its memory of past threats; (B) expression of the CRISPR array and processing the transcripts into mature RNA guides; and (C) interference, where the mature RNAs guide the CRISPR-associated proteins to complementary regions in the foreign genetic material (known as protospacers), where they bind and neutralize the invader [417,418].

Differences among CRISPR loci in the composition of the Cas proteins and the effector modules allowed the classification of the CRISPR-Cas systems into two major classes: class 1 and class 2 [419,420]. Class 1 includes the CRISPR systems where the effector complex consists of multiple protein subunits such as the CRISPR types I, III, and IV [420,421]. On the other hand, the CRISPR systems of class 2 are defined by possessing a single-unit effector protein such as the CRISPR types II, V, and VI [420,422]. These six CRISPR types are further subdivided into 33 subtypes according to the composition and architecture of the Cas operon, as well as the Cas1 protein phylogeny [420,423]. Figure 2 illustrates the general CRISPR mechanism of action and a representative CRISPR type of each class.

Figure 2.

Representation of CRISPR mechanism of action and CRISPR-Cas classes I and II. (a) General CRISPR mechanism of action represented by three main stages: adaptation, expression, and interference. (b) CRISPR antimicrobial delivery into target bacteria via conjugation or transduction for either plasmid curing or bactericidal chromosomal targeting. (c) Class I of CRISPR-Cas, represented by CRISPR-Cas3 (type I-E). Numbers 1–11 represent components of the cascade complex (1 = CasA; 2, 3 = two units of CasB; 4–9 = 6 units of CasC; 10 = CasD; 11 = CasE). Number 12 represents the effector Cas3 protein which induces a nick in the displaced non-target strand. (d) Class II of CRISPR-Cas, represented by CRISPR-Cas9 (type II-A). Only one effector protein is involved in this system, the Cas9 protein. The guide crRNA is partially hybridized to an RNA molecule known as tracrRNA. The Cas9 protein induces double-stranded break in both target and non-target strands.

Both the expression and interference stages constitute the main pillars for the CRISPR-based antimicrobials. Delivering a CRISPR array that includes a self-targeting spacer besides the CRISPR-associated genes into the bacteria will target the bacterial own DNA, imposing a toxic stress on it. Bacteria do not tolerate self-targeting by CRISPR systems due to their inefficient DNA repair mechanisms which render chromosomal targeting lethal [424]. A strict requirement for CRISPR antimicrobials is to ensure the presence of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) flanking the targeted protospacer. PAM is a few-nucleotide sequence acting as a signal for Cas proteins to cut the genetic material upon the complementary binding between the guide RNA and the protospacer [425]. This criterion must be considered during the spacer selection process to guarantee the efficiency of targeting.

An early trial to prove this concept was conducted by Gomaa et al., who targeted the E. coli K-12 by transforming the bacterium with plasmids expressing the CRISPR-Cas proteins of the type I-E CRISPR system (i.e., cascade complex and Cas3) and a minimal CRISPR array containing a single spacer that was modified to target a different chromosomal gene each time [426]. Following this experiment, other trials tested different CRISPR-Cas systems and various delivery strategies. CRISPR-Cas9-based antimicrobials were delivered either via plasmid conjugation [427,428] or phage-based-delivery [429,430] to target different pathogens such as Salmonella Typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecalis. These trials and many others have proven the efficiency of different CRISPR-Cas systems to target several bacterial pathogens [431]. Furthermore, a key advantage of CRISPR technology is its high specificity, through which CRISPR-based antimicrobials can efficiently eliminate certain bacterial strains in mixed bacterial cultures, allowing to distinguish between pathogens and commensals [426,429,432,433].

Despite the auspicious future of the CRISPR-based antimicrobials, challenges have been outlined. An important prerequisite for successful application of CRISPR as an antimicrobial is to define a specific target site of the pathogen. Two approaches could be exploited; either a pathogen-focused approach or a gene-focused approach [434]. In the pathogen-focused approach, the target site must be located on the bacterial chromosome to ensure elimination of the pathogen. This target site could either be a virulence gene, a resistance gene, any pathogenicity determinant, or another unique DNA signature of the bacterial pathogen [435,436]. On the other hand, the gene-focused approach ensures the depletion of the gene from the bacterial population rather than the pathogen itself. Therefore, it focuses on targeting plasmid-carried resistance genes, leading to curing of the plasmid, depletion of the gene, and resensitizing of the host bacterium [437,438,439]. It is worth noting that knocking out plasmids that possess toxin/antitoxin addiction systems indicates that targeting plasmids may not only cure the plasmid but can also kill the host bacterium on occasion [440]. Regarding the control of APEC, the target selection process constitutes a major limitation. The precise identification of the APEC pathotype determinants remains vague, with variable combinations of virulence genes used as an indicative of the APEC genotype. Additionally, many virulence determinants are harbored on large virulence plasmids in the bacterium [166,441], which, as discussed before, may set a barrier against using them as targets. However, it is of interest that curing these large virulence-encoding plasmids may render the host bacterium either less pathogenic or even avirulent.