Simple Summary

This study investigated heart rate variability (HRV) as a non-invasive method to monitor the emotional state of a donkey involved in Animal-Assisted Services (AAS). By applying a heart rate monitor, we recorded parameters indicating the emotional state of the donkey suitable for sessions of Animal-Assisted Therapy, without causing stress or discomfort. The finding suggests that HRV spectral analysis may provide valuable insight into the welfare of donkeys during therapeutic activities, supporting animal well-being and the effectiveness of animal-assisted interventions.

Abstract

Background: Only a limited number of studies have investigated objective indicators to assess donkey welfare during Animal-Assisted Services. Objective: The present research follows a single-subject design and its objective is to evaluate the neurovegetative indicators of the well-being of a donkey through spectral analysis of the R-R signal in the frequency domain. Methods: The experimental protocol of the Animal-Assisted Therapy project involved one donkey, previously selected through behavioral protocol evaluation, and ten patients with a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia. Spectral analysis of the R-R signal in the frequency domain was performed, providing objective data on the activity of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems of the donkey (before, during, and after the sessions). Results: The significance of the variations, both statistically significant and not, supports the hypothesis that the affiliative human–donkey interaction within the context of AAS is associated with modifications in the neurovegetative components of the donkey involved in AAT. Conclusions: These findings highlight the importance of objective and non-invasive monitoring tools to detect early signs of discomfort in donkeys involved in AAT, supporting the development of selection and management strategies that safeguard animal welfare.

1. Introduction

Research on animal emotions during Animal-Assisted Service (AAS) is a new focus of animal welfare science, and the correlation of ethological and physiological parameters provides new and significant elements to measure animal empathic involvement [1,2,3,4]. Measuring animals’ emotions presents some inherent difficulties [5,6,7]), such as the wide variety of behavioral patterns among species [5].

Recent literature has increasingly explored affective and affiliative processes in equids, particularly in the context of animal-assisted interventions (AAS). Although the interpretation of discrete emotional states in donkeys remains limited, several studies have shown that equids display behavioral and physiological patterns consistent with variations in affective valence and arousal. For example, Mendonça et al. (2019) [8] reported that horses involved in equine-assisted therapy exhibit changes in heart rate variability (HRV) and behavioral indicators that reflect their level of comfort, alertness, or challenge during human–animal interactions. Similarly, Seganfreddo et al. (2023) [4] demonstrated that donkeys show measurable behavioral adjustments and HRV variations when exposed to situations with different emotional relevance, suggesting that non-invasive physiological measures can be informative for assessing affective responses in this species.

More broadly, research on affective states in domestic ungulates supports the feasibility of investigating emotional valence using physiological markers. Ramirez Montes de Oca et al. (2024) [9] identified thermographic asymmetries associated with positive and negative affective conditions in calves, reinforcing the view that animals can exhibit measurable physiological correlates of affective processing. Furthermore, qualitative research in the AAS field emphasizes the importance of considering the animal’s behavioral engagement and social motivation during therapeutic sessions [10], highlighting that affiliative tendencies and social responsiveness contribute to the quality of human–animal interactions. These findings collectively support the relevance of examining changes in arousal and affiliative behavior in donkeys during AAS, without assuming complex emotional intentionality.

Species-specific ethograms, animal proxemics, and the analysis of posture, attitudes, and vocalizations [11,12,13,14] are often used, because they are rapid and harmless; however, no single indicator can provide a complete picture of an animal’s emotional status. Yet, the need for multiple indicators entails the risk of their non-concordance [11]. Another ethological parameter is facial emotional expression, which must be based on reliable, scientifically validated, and non-invasive measurement methodologies [15,16].

Facial expressions are widely studied in humans as a parameter of psychological and emotional experiences. However, they are rarely used in animal studies, with the exception of the emerging field of research concerning postural attitudes and ongoing facies of painful symptomatology in mice [17], rabbits [18], horses [19], cats [20], and donkeys [21,22,23].

In the study of animal emotions, positive emotion states have received less empirical consideration than negative emotions; however, awareness of the importance of positive experiences is increasing, as is the characterization of what constitutes a positive experience for an animal [24,25,26,27,28].

Facial expressions, posture analysis, and vocalizations, as manifestations of an animal’s emotional state, require an objective evidence base; for example, the evaluation of heart rate variability (HRV) can provide evidence for the involvement of the central neurophysiological processes underlying the responses to stress or the different levels of well-being of both farm and companion animals [29,30,31,32].

Heart rate variability (HRV) is an indicator of altered states of emotional homeostasis, which can occur in situations of emotional stress in humans [33] and non-human animals [29,31,32,34,35,36]. HRV assessment has also been used in autonomic nervous system research on animals [34]. In donkeys, it has been studied as an indicator of stress [4], with one study comparing HRV parameters with two different training methods [37] and another with HRV analysis before, during, and after an AAS session [38]; these studies support the use of heart rate variability as a reliable indicator of emotional activation and stress response in equids exposed to different types of human interaction and training conditions.

HRV assessment has also been applied to study the functioning of the autonomic nervous system [39], to analyze changes in the sympatico vagal balance linked to diseases and psychological and environmental stressors [40,41,42,43,44,45,46] or to analyze individual characteristics such as temperament and coping strategies [47,48,49,50,51,52].

On the adaptive side of coping, a higher use of active coping was associated with lower heart rate variability (HRV) in a sample of young healthy men, while there were no significant correlations between HRV and coping for women [53]). In another study, women who reported higher use of problem-focused techniques (i.e., seeking social support) had higher baseline systolic and diastolic blood pressure, as well as higher blood pressure reactivity, during a mental arithmetic task [54].

Recent literature highlights that HRV can be considered a useful physiological indicator associated with affective states in equines and other domestic species. For example, in some studies [4,8] discuss HRV within the framework of emotional assessment in horses and donkeys, and Ramirez Montes de Oca et al. (2024) [9] reports physiological indicators associated with affective valence in calves.

Changes in cardiac activity are considerably influenced by behavior; in particular, those related to motor activity (kinetic, exploratory, grazing, social activity, etc.) [55,56] can be compared with non-motor or psychological/emotional components. Another important aspect is that variations in cardiac activity can be anticipatory, occurring before the expression of any behavior. These anticipatory variations in cardiac activity have been observed in numerous animal species; for example, it is not rare to observe tachycardia several seconds before the emergence of a behavioral change, just as a cardiac response can be maintained beyond the expression of the specific behavioral event with which it was initially related.

These relationships can be considered as specific circulatory demands through which the cardiovascular components of affective-emotional responses are expressed.

For this reason, among the physiological indicators of animal reactivity or emotional stability, through its frequency and variability, the monitoring of cardiac activity constitutes a valid objective evaluation parameter to determine the level of emotional involvement in experimentally induced situations.

Exploring the underlying autonomic control activity of HRV through spectral analysis of the R-R signal in the frequency domain provides objective data reflecting the activities of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems [57,58,59,60].

Attempts to objectively identify stress from physiological signals have involved temporal [61], spectral [57], and nonlinear [62] measures; nevertheless, conventional algorithms have not been able to obtain a reliable and exact method to discern between stress states and rest.

The generic physiological response to combat stress, called “fight-or-flight,” is largely driven by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). However, the responses to stress are not exclusively sympathetic; the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) participates in the response to stress with manifestations such as crying or emptying the bladder.

In humans sympathetic activity tends to increase the heart rate (HR) and decrease the heart rate variability (HRV), while parasympathetic activity tends to decrease the HR and increase the HRV [39]. Through power spectral analysis of the HRV, it is possible to determine the low-frequency (LF) and high-frequency (HF) power of the HRV [41]. The LF power is primarily influenced by sympathetic nervous activity, as well as baroreceptor responses, and a correlation was observed between LF power and muscle sympathetic nerve activity in healthy subjects [58]. The HF power is influenced by respiratory fluctuations, enhanced by vagal stimulation, and attenuated by inhibiting muscarinic receptors or vagal blockades, suggesting that the HF power indicates parasympathetic processes. Hence, power spectral analysis of the HRV provides a means to indirectly investigate autonomic nervous system function, reliably detect the affective states of the subject under study, and provide comfort/discomfort indicators. The heuristic approach to monitoring animal affective state, using the methods and tools of applied veterinary ethology, involves the construction of an evaluation model with known input variables (neurovegetative parameters). Most contemporary approaches for investigating emotions in animals rely on interpreting behavioral patterns together with physiological indicators. Some of these measures—for example, changes linked to physiological stress responses—can reveal whether an animal is experiencing heightened arousal, although they provide limited information about the positive or negative valence of that state [63,64]. Other approaches, such as cognitive bias assessments, can offer insights into whether an animal is in a generally more positive or more negative affective condition [14]. The ethological variables were determined through the comparative semantic study of both the postures and facies of a horse [65], together with our previous investigations into the topic [38,66,67,68]. From the bibliographical review of the effects of assisted therapies with horses and donkeys [69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80], it emerged that, in AAS with a horse, the therapy aimed at achieving postural and kinetic physical benefits and, more generally, kinesics, while in AAS with a donkey, the therapy aimed at improving mental health and was used in co-therapeutic approaches for neurodiversity.

In AAS, the assessment of animals’ affiliative tendencies [10,37] is determined via the measurement of their activation state. In various sessions, modifications in the level of arousal [4,8,14]—facilitated by the autonomic nervous system (ANS), the hypothalamic–pituitary axis, and the adrenal gland (HPA)—can be evaluated through adaptive physiological reactions such as the heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), breath frequency (BF), pupil diameter, sweat, corticosteroids levels, and neurotransmitters [81]. These neurovegetative responses are analogous to those observed in humans [82]. Through the correlation of ANS physiological profiles and the ethological parameters of experience, it is possible to assess animal emotions. In humans, a meta-analysis of 22 ANS parameters proved that changes in cardiovascular parameters enable differentiation between positive and negative affective-emotional components of emotions [83]. Other studies have shown that 11 ANS parameters (cardiovascular, electrodermal, and respiratory) vary (with a precision of 85%) between fear, sadness, and neutral emotional responses [84].

To date, no published studies have investigated heart rate variability (HRV) or other objective physiological indicators in donkeys involved in animal-assisted services, and no protocols exist for monitoring donkeys during AAT. For this reason, our work aims to provide an initial contribution in two directions:

(1) To support the preliminary selection of suitable subjects from a group of donkeys that are not yet experienced for AAT (AWIN welfare assessment protocol for donkeys), particularly with regard to behavioral aspects (Avoidance Test, Novel Object Tests, Unknown Person Test);

(2) To propose an approach based on objective physiological monitoring, which may help identify signs of stress in donkeys during AAT sessions, considering the limited knowledge of their behavioral signals and expressions of discomfort.

We aimed to evaluate the neurovegetative indicators of the well-being of a donkey used for AAS through spectral analysis of the R-R signal (cardiac beat-to-beat interval series) in the frequency domain, which could provide behavioral indicators of comfort/discomfort of the donkey. Ethically, it is crucial to ensure that AASs do not evolve into an advanced type of animal exploitation.

2. Materials

The present research follows a single-subject design, since our methodological approach involved repeated measurements and intra-subject comparisons across different therapy sessions. All procedures were conducted in strict accordance with the Italian legal requirements (National Directive n. 26/14–Directive 2010/63/UE) and followed the guidelines for the care of animals in behavioral research as established by the Association for the Study of Animal Behavior (ASAB). The study group comprised 8 healthy Sardinian donkeys: six females and two stallions, aged 6 ± 2.20 years, free housed on a social farm within the premises of a religious organization in Ragusa (Italy), without any experience in AAS. Although the animal had no prior experience with animal-assisted therapy (AAT), it was accustomed to human presence and daily interactions with its caregiver and other strange people. It is also important to clarify that the donkeys considered for selection were not used for zootechnical or productive purposes, but were kept for non-productive aims, in a context that allowed regular contact with people and positive human–animal interactions (social farm).

During the day, the animals were kept in a paddock of approximately 2000 m2 and transferred at night to an 800 m2 paddock with a collective box measuring 70 m2. Their daily rations consisted of a single distribution of hay (5.0 kg/animal/day) and commercial concentrate feed (2.5 kg/animal/day, labeled as containing crude protein 13.00%, ether extract oil 3.20%, crude fiber 13.00%, ashes 10.50%, sodium 0.50%, lysine 0.44%, and methionine 0.21%). The animals had continuous access to grazing on about 2000 m2, and water was available ad libitum.

Prior to collecting the ethological data, all animals underwent assessment using the “AWIN welfare assessment protocol for donkeys” [85], administered by the same veterinarian trained specifically in animal welfare. All donkeys participating in this preliminary part of the study received a score of 3 out of 5, exhibited a negative skin tent test, and showed no injuries. The evaluation protocol [38] resulted in the selection of one donkey, a seven-year-old female named Adalgisa, who was deemed suitable based on the behavioral assessments and therefore considered appropriate to be involved in the AAT sessions.

Before the experimental phase, the selected donkey underwent a three-month habituation period with the handler (animal coadjutor) involved in the project. During this stage, the animal was gradually accustomed to being led with a halter; it was already familiar with gentle handling and routine manipulation by the caregiver. Moreover, prior to HRV data collection, the donkey was progressively habituated to wearing the girth belt used to secure the heart rate monitor. This preparatory habituation process likely contributed to reducing potential stress during the experimental sessions.

The experimental protocol of the AAT project included 10 patients (5 men and 5 women), with an average age of 55.44 +/− 6.10, a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia (ICD-11 code, diagnostic code 295.8, according to the ICF classifier), and no previous experience of AAS. The AAT project was structured with 7 sessions for each patient on a weekly basis. The 70 sessions were video-recorded, and to ensure the validity and completeness of the spectral analysis of HRV, 38 were analyzed, as the remaining 32 had signal distortions that made spectral analysis unusable. The donkey was easily led during the sessions, using a nylon halter and a braided cotton lead rope approximately 2.5 m by its handler, and it was occasionally allowed to move freely within the working area. The AAT sessions were recorded, each including the animal’s approach, presentation, contact, hand control activity (brush and curry), hand conduct (using a lead wire with a snap hook in the halter), and detachment (grooming at the withers, vocalizations, and removal). Each session lasted 20 min for each patient, including approximately 10 min of hand control activity and approximately 10 min in which a short 20/30 m lap was performed with a lanyard. There were two intervention delivery areas: one of approximately 60 m2 with a roof and another of approximately 200 m2; the choice of the first or second depended on the current climatic conditions.

3. Methods

The heart rate (HR) was measured in real time using Polar S610i and Polar V800S Polar® heart rate monitors, scanning every 5 s. The Polar S610i heart rate monitor was placed on the cardiac auscultation area ichthys. Bluetooth technology was used by the operator, and a polar belt equine chest strap was fitted to the donkey. Data were transferred via infrared or Bluetooth port to a PC running the Polar Horse SW 4.0 or Polar Flow Sync software and then processed and graphed according to preset macros. The entire temporal session of the heart rate monitor data was compiled in a spreadsheet to calculate the descriptive statistics (average, minimum, and maximum bpm per group). The HR was recorded for 10 min before (T0), 20 min during (T1), and 10 min after (T2) the AAT session.

Spectral Analysis of the HRV Frequency Domain

In the frequency-domain analysis method, a spectrum evaluation is computed for the adjacent R-wave (R-R interval or R-R) of the QRS complex of the electrocardiogram (ECG) signal. Spectral analysis of the variations in the R-R time series, carried out using the Kubios Premium software®, allows for determination of the fundamental oscillatory components, i.e., the frequency bands. In the software, the spectrum is estimated using an autoregressive model and can be partitioned into different spectral components by applying spectral factorization [86,87]. Kubios HRV 2.1 supports the file format of Polar HRM (*.hrm). Spectrum assessments are then partitioned into very-low-frequency (VLF), low-frequency (LF), and high-frequency (HF) bands. The usually employed limits for these bands in normal human subjects are as follows: 0–0.04 Hz (VLF) and 0.04–0.15 Hz (LF), representing sympathetic and vagal modulation, with sympathetic predominance, and 0.15–0.4 Hz (HF), which represents vagal modulation. The software calculates the peak frequencies of the VLF, LF, HF, LF/HF power ratio, and total spectral power. We made the spectral analysis even more reliable by subjecting the time-series to the Welch protocol for spectral periodograms (Hamming window).

Although the interpretation of HRV indices is mainly based on human studies, our aim was to apply these established analytical approaches to donkeys in order to provide new preliminary species-specific data.

4. Statistics

The experimental heart rate (HR) data obtained were analyzed using the Friedman test for repeated measures and, subsequently, the Wilcoxon test, in order to identify statistically significant comparisons.

5. Results

The following section reports the obtained results in Table 1 and Table 2 and in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The mean basal HR values were equal to 42.62 ± 3.63, in agreement with the literature [38,88,89,90,91,92], with average Fcmin values equal to 31.87 ± 3.07 and average Fcmax values equal to 55.19 ± 4.53.

Table 1.

Monitoring of the average values of the heart rate parameters of the donkey involved for the AAT session with patients with schizophrenic spectrum disorders.

Table 2.

Monitoring of the average values of the spectral analysis of heart rate parameters of the donkey involved for the AAT session with patients with schizophrenic spectrum disorders.

Figure 1.

The donkey’s heart parameters in the animal-assisted therapeutic (AAT) session with patients with schizophrenic spectrum disorder.

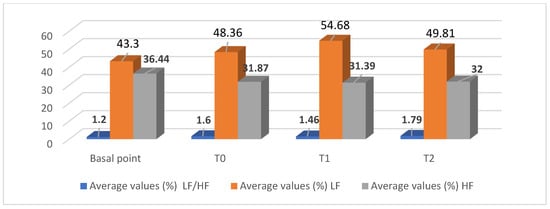

Figure 2.

Average values of the spectral analysis of the donkey’s heart parameters in the animal-assisted therapeutic (AAT) session with patients with schizophrenic spectrum disorders.

We found statistically significant variations in the mean values during the AAT sessions with patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (ICD-11): there were higher mean values of the Fcmax at T1 equal to 75.55 ± 18.44 and, at T2, which were equal to 72.60 ± 14.70 (p < 0.05), as well as the mean values of the mean Fcmax at T2, which were equal to 47.60 ± 3.47 (p < 0.05).Our previous investigations highlighted such significant variations in the donkey’s HRV during the sessions [35,86]. In terms of the other available literature on the topic, the investigations appear mostly demoscopic [93] or refer to the influence on the salivary cortisol levels of the donkey of the familiarity of contact with normal young people, aged between 18 and 23 [94].

6. Discussions

The results relating to the determination of the most important oscillatory components of HRV in the frequency domain represent an original contribution to the determination of the spectral components of the donkey’s R-R time series. The average percentage basal values of the high-frequency component (HF) of the power spectrum reached 36.44 ± 4.72, and those of the low-frequency component (LF) reached 43.30 ± 4.29, with an average value of the LF/HF ratio of 1.20 ± 0.17. The average percentage values of the HRV spectral parameters of the donkey participating in the AAT session showed insignificant increases in the LF/HF ratio and the average percentage value of LF and, conversely, decreases in the average percentage value of HF.

The significance of the set of variations, whether statistically significant or not, of the monitoring indicators of the effects of the AAT session on the temporal trend of HRV, supports the hypothesis that, through the creation of the patient/animal dyad, the care relationship induces variations in the neurovegetative components that express the emotional involvement of the donkey participating in AAT. This suggests the need for adequate rest times between sessions. On the other hand, the percentage increase in the average Fc average values from 42.62 at baseline to 75.55 at time T1 with a +77.26% testifies to emotional distress, which demonstrates a lower variability in the HRV due to the predominance of the sympathetic neurovegetative component.

The AAT session in this study may be a potential context of emotional distress in the donkey, due to the donkey’s high affiliative tendencies. This should lead to adequate attention to its management before and after the session, identifying activities that are most effective in balancing and buffering the effects that the AAT session induces.

It is usually mandatory to interpret experimental results conditionally, as they can be influenced by the quantity of variables, the operational difficulties, and the complexity of the context. Despite the small sample size (one subject), it is appropriate to highlight, once again, that the path of scientific validation of investigations in the context of the potential therapeutic or educational effects or repercussions on animals of HAIs is just beginning and, until non-parametric statistical tools or principal component analyses are common, there will still be a debate as to the necessary sample size and the need for multi-center and randomized studies that researchers apply to the effects of AAS.

The robustness of the experimental data obtained in ethological investigations applied to AAS cannot be derived from the aseptic application of the validation methods of clinical studies. It would be ideal to demonstrate the validity of a research study in the AAS context by attempting to determine how much the results of the study participants represent those of similar individuals outside the study, or by suggesting that its internal validity can be guaranteed by an adequately representative sample population.

It will be interesting to investigate any correlations between the observed asinine facial expression, a relevant ethological parameter, and the parameters obtained through spectral analysis in the frequency domain. Correlating the expression of discomfort or compliance with the corresponding values of the LF/HF ratio could provide a valid indicator for ethological monitoring in the field.

7. Considerations

The founding value of Animal-Assisted Services (AAS) lies in the evident and recognized benefit that the human participant (user/patient) derives from the care or educational relationship (dyad human and animal). However, the growing enthusiasm for these integrative therapeutic approaches should not compromise the coherence of the methodology, nor overlook the affective state assessment of the other partner—the four-legged one.

The ethics of the interspecific relationship require balancing the costs and benefits for both protagonists of the dyad, even when supported, directed, or guided by a human intervention representative or the animal’s handler.

Donkeys are often selected for interventions without standardized behavioral criteria, and inexperienced animals may show subtle signs of discomfort that are easily overlooked due to the scarce knowledge of the species’ ethological, postural, and expressive repertoire compared with horses or dogs. For this reason, inadequate selection procedures or poorly structured AAT sessions may expose donkeys to stress that is not immediately identifiable through observation alone.

We ensure the protection of the rights of animals involved in AAS only when we verify that their affiliative involvement is ethically acceptable, and we provide them with adequate opportunities for rest and refreshment. The ethical threshold not to be crossed is precisely defined by the scientific evidence that enables us to design Animal-Assisted Therapy and Animal-Assisted Education sessions with prudence, considering the animal’s arousal level. Ignoring these aspects would result in a subtle yet sophisticated form of animal exploitation. Scientific evidence defines the ethical threshold we must respect when designing Animal-Assisted Therapy and Animal-Assisted Education sessions. This evidence guides us to act with prudence and to consider the animal’s arousal level at every stage. Failing to take these aspects into account risks turning the intervention into a subtle yet sophisticated form of animal exploitation.

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.P.; Formal analysis, Investigation, and Resources, A.S.; Data curation, M.P. and A.S.; Writing—Original draft preparation, A.S.; Review and editing, M.P. and A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, because the procedure was non-invasive (the application of a heart rate monitor to donkeys already accustomed to use a girth).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not required, because the donkeys involved in the study were not privately owned; they were hosted in a social farm within the premises of a religious organization.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The dataset is not public available because it is part of an ongoing research program, and additional analyses are planned for future publications.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Burden, F.A.; Thiemann, A. Donkeys Are Different. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2015, 35, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-De Cara, C.A.; Perez-Ecija, A.; Aguilera-Aguilera, R.; Rodero-Serrano, E.; Mendoza, F.J. Temperament Test for Donkeys to Be Used in Assisted Therapy. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 186, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegatheesan, B.; Beetz, A.; Ormerod, E.; Johnson, R.; Fine, A.; Yamazaki, K.; Dudzik, C.; Garcia, R.M.; Winkle, M.; Choi, G. The IAHAIO Definitions for Animal-Assisted Intervention and Guidelines for Wellness of Animals Involved in AAI. In IAHAIO Whitepaper; International Association of Human–Animal Interaction Organizations: Seattle, WA, USA, 2014; Updated 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Seganfreddo, S.; Fornasiero, D.; De Santis, M.; Mutinelli, F.; Normando, S.; Contalbrigo, L. A Pilot Study on Behavioural and Physiological Indicators of Emotions in Donkeys. Animals 2023, 13, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Désiré, L.; Boissy, A.; Veissier, I. Emotions in Farm Animals: A New Approach to Animal Welfare in Applied Ethology. Behav. Process. 2002, 60, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendl, M.; Burman, O.H.P.; Paul, E.S. An Integrative and Functional Framework for the Study of Animal Emotion and Mood. Proc. R. Soc. B 2010, 277, 2895–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panksepp, J. The Basic Emotional Circuits of Mammalian Brains: Do Animals Have Affective Lives? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 1791–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, T.; Bienboire-Frosini, C.; Menuge, F.; Leclercq, J.; Lafont-Lecuelle, C.; Arroub, S.; Pageat, P. The Impact of Equine-Assisted Therapy on Equine Behavioral and Physiological Responses. Animals 2019, 9, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Oca, M.A.R.M.; Mendl, M.; Whay, H.R.; Held, S.D.E.; Lambton, S.L.; Telkänranta, H. An exploration of surface temperature asymmetries as potential markers of affective states in calves experiencing or observing disbudding. Anim. Welf. 2024, 33, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dixon, D.; Jones, C.; Green, R. Understanding the role of the animal in animal-assisted therapy: A qualitative study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2025, 60, 101983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, G.; Mendl, M. Why Is There no Simple Way of Measuring Animal Welfare? Anim. Welf. 1993, 2, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, M.S. Using Behaviour to Assess Animal Welfare. Anim. Welf. 2004, 13 (Suppl. S1), S3–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormède, P.; Andanson, S.; Aupérin, B.; Beerda, B.; Guémené, D.; Malmkvist, J.; Manteca, X.; Manteuffel, G.; Prunet, P.; van Reenen, C.G.; et al. Exploration of the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Function as a Tool to Evaluate Animal Welfare. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendl, M.; Burman, O.H.P.; Parker, R.M.A.; Paul, E.S. Cognitive Bias as an Indicator of Animal Emotion and Welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 118, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansade, L.; Nowak, R.; Lainé, A.L.; Leterrier, C.; Bonneau, C.; Parias, C.; Bertin, A. Facial Expression and Oxytocin as Possible Markers of Positive Emotions in Horses. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descovich, K. Facial Expression: An Under-Utilised Tool for the Assessment of Welfare in Mammals. ALTEX 2017, 34, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford, D.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Chanda, M.L.; Clarke, S.E.; Drummond, T.E.; Echols, S.; Glick, S.; Ingrao, J.; Klassen-Ross, T.; Lacroix-Fralish, M.L.; et al. Coding of Facial Expressions of Pain in the Laboratory Mouse. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, M.C.; Klaus, K.; Miller, A.L.; Scotto di Perrotolo, M.; Sotocinal, S.G.; Flecknell, P.A. The Assessment of Post-Vasectomy Pain in Mice Using Behaviour and the Mouse Grimace Scale. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleerup, K.B.; Forkman, B.; Lindegaard, C.; Andersen, P.H. An Equine Pain Face. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2015, 42, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, M.C.; Watanabe, R.; Leung, V.S.Y.; Monteiro, B.P.; O’Toole, E.; Pang, D.S.J.; Steagall, P.V. Facial Expressions of Pain in Cats: The Feline Grimace Scale. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, E.K.; Navas González, F.J.; Iglesias Pastrana, C.; Berger, J.M.; Jeune, S.S.L.; Davis, E.W.; McLean, A.K. Development of a Donkey Grimace Scale to Recognize Pain in Donkeys Post-Castration. Animals 2020, 10, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dierendonck, M.C.; Burden, F.A.; Rickards, K.; van Loon, J.P.A.M. Monitoring Acute Pain in Donkeys with the EQUUS-DONKEY-COMPASS and EQUUS-DONKEY-FAP. Animals 2020, 10, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.G.C.D.; Paula, V.V.D.; Mouta, A.N.; Lima, I.D.O.; Macêdo, L.B.D.; Nunes, T.L.; Trindade, P.H.E.; Luna, S.P.L. Validation of the Donkey Pain Scale (DOPS). Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 671330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissy, A.; Manteuffel, G.; Jensen, M.B.; Moe, R.O.; Spruijt, B.; Keeling, L.J.; Winckler, C.; Forkman, B.; Dimitrov, I.; Langbein, J.; et al. Assessment of Positive Emotions in Animals to Improve Their Welfare. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgdorf, J.; Panksepp, J. The Neurobiology of Positive Emotions. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2006, 30, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, S.D.E.; Spinka, M. Animal Play and Animal Welfare. Anim. Behav. 2011, 81, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krachun, C.; Rushen, J.; de Passillé, A.M. Play Behaviour in Dairy Calves Is Reduced by Weaning and Low Energy Intake. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 122, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.D.; Waterman-Pearson, A.E. Pain and Distress Responses to Castration in Young Lambs. Res. Vet. Sci. 1999, 66, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiveldinger, L.; Veissier, I.; Boissy, A. Behavioural and Physiological Responses of Lambs to Aversive Events. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, E.K.; Ueda, Y.; Walker, A.L.; Hart, L.A.; Simas, S.; Stern, J.A. Heart Rate Variability in Cats: ECG vs. Polar Monitors. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 741583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maros, K.; Dóka, A.; Miklósi, Á. Behavioural Correlation of Heart Rate Changes in Dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 109, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gácsi, M.; Maros, K.; Szakadát, S.; Miklósi, Á. Owner Safe Haven Effect in Dogs. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58475. [Google Scholar]

- Thayer, J.F.; Ahs, F.; Fredrikson, M.; Sollers, J.J., 3rd; Wager, T.D. Meta-Analysis of HRV and Neuroimaging. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012, 36, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Borell, E.; Langbein, J.; Després, G.; Hansen, S.; Leterrier, C.; Marchant, J.; Marchant-Forde, R.; Minero, M.; Mohr, E.; Prunier, A.; et al. HRV and Stress in Farm Animals. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhne, F.; Hößler, J.; Struwe, R. Human–Horse Interactions on HR and Behaviour. J. Vet. Behav. 2014, 9, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lanata, A.; Valenza, G.; Scilingo, E.P. EDA–HRV Multimodal Index for Emotion Recognition. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 82. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, A.K.; Heleski, C.R.; Yokoyama, M.T.; Wang, W.; Doumbia, A.; Dembele, B. Improving Working Donkey Welfare in Mali. J. Vet. Behav. 2012, 7, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzera, M.; Alberghina, D.; Statelli, A. Ethological and Physiological Parameters in Donkeys Used in AAI. Animals 2020, 10, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntson, G.G.; Bigger, J.T., Jr.; Eckberg, D.L.; Grossman, P.; Kaufmann, P.G.; Malik, M.; Nagaraja, H.N.; Porges, S.W.; Saul, J.P.; Stone, P.H.; et al. HRV Origins and Methods. Psychophysiology 1997, 34, 623–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Task Force of the ESC & NASPE. Heart Rate Variability Standards. Eur. Heart J. 1996, 17, 354–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendra Acharya, U.; Paul Joseph, K.; Kannathal, N.; Lim, C.M.; Suri, J.S. HRV: A Review. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2006, 44, 1031–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ravenswaaij-Arts, C.M.; Kollée, L.A.; Hopman, J.C.; Stoelinga, G.B.; van Geijn, H.P. Heart Rate Variability. Ann. Intern. Med. 1993, 118, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Camm, A.J. Components of HRV. Am. J. Cardiol. 1993, 72, 821–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumprla, J.; Howorka, K.; Groves, D.; Chester, M.; Nolan, J. Functional assessment of heart rate variability: Physiological basis and practical applications. Int. J. Cardiol. 2002, 84, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achten, J.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Heart Rate Monitoring. Sports Med. 2003, 33, 517–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelhans, B.M.; Luecken, L.J. HRV as Emotional Regulation Index. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2006, 10, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S.W. Cardiac Vagal Tone. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1995, 19, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, S.W. Polyvagal Theory. Physiol. Behav. 2003, 79, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S.W.; Doussard-Roosevelt, J.A.; Portales, A.L.; Greenspan, S.I. Infant regulation of the vagal "brake" predicts child behavior problems: A psychobiological model of social behavior. Dev. Psychobiol. 1996, 29, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doussard-Roosevelt, J.A.; Porges, S.W.; Scanlon, J.W.; Alemi, B.; Scanlon, K.B. Vagal regulation of heart rate in the prediction of developmental outcome for very low birth weight preterm infants. Child Dev. 1997, 68, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, B.H.; Thayer, J.F. Anxiety and Autonomic Flexibility. Biol. Psychol. 1998, 47, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpeggiani, C.; Emdin, M.; Bonaguidi, F.; Landi, P.; Michelassi, C.; Trivella, M.G.; Macerata, A.; L’Abbate, A. Personality traits and heart rate variability predict long-term cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 1612–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaekers, D.; Ector, H.; Demyttenaere, K.; Rubens, A.; Van de Werf, F. Association between cardiac autonomic function and coping style in healthy subjects. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 1998, 21, 1546–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.; McLaughlin, M. Coping, Stress, and HRV in Women. Behav. Med. 1998, 24, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopster, H.; van der Werf, J.T.N.; Blokhuis, H.J. Milking Parlour Behaviour and HR. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1998, 55, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, B.; Mohr, E.; Krzywanek, H. Aqua-Treadmill Effects in Horses. J. Vet. Med. A 2002, 49, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montano, N.; Ruscone, T.G.; Porta, A.; Lombardi, F.; Pagani, M.; Malliani, A. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability to assess the changes in sympathovagal balance during graded orthostatic tilt. Circulation 1994, 90, 1826–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagani, M.; Montano, N.; Porta, A.; Malliani, A.; Abboud, F.M.; Birkett, C.; Somers, V.K. Relationship between spectral components of cardiovascular variabilities and direct measures of muscle sympathetic nerve activity in humans. Circulation 1997, 95, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porta, A.; Tobaldini, E.; Guzzetti, S.; Furlan, R.; Montano, N.; Gnecchi-Ruscone, T. Assessment of cardiac autonomic modulation during graded head-up tilt by symbolic analysis of heart rate variability. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 293, H702–H708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. Overview of HRV Metrics. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar]

- Castrillón, C.I.M.; Miranda, R.A.T.; Cabral-Santos, C.; Vanzella, L.M.; Rodrigues, B.; Vanderlei, L.C.M.; Lira, F.S.; Campos, E.Z. High-Intensity Intermittent Exercise and Autonomic Modulation: Effects of Different Volume Sessions. Int. J. Sports Med. 2017, 38, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Vuksanović, V.; Gal, V. Analysis of HR Variability. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2007, 64, 621–627. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hinde, R.A. Was ‘The expression of the emotions’ a misleading phrase? Anim. Behav. 1985, 33, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.S.; Harding, E.J.; Mendl, M. Measuring emotional processes in animals: The utility of a cognitive approach. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 469–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathan, J.; Burrows, A.M.; Waller, B.M.; McComb, K. EquiFACS. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innella, G.; Luigiano, G.; Di Rosa, A.; Panzera, M. Etogramma Neonatale diurno e materno dell’Asino Pantesco. In Proceedings of the 6th Convegno Nazionale Società Italiana di Fisiologia Veterinaria (SO. FI VET.), Stintino, Italy, 2–4 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Malara, L.; Luigiano, G.; Arcigli, A.; Innella, G.; Di Rosa, A.; Panzera, M. Etogramma notturno neonatale e materno dell’asino Pantesco. In Proceedings of the Atti II Convegno Nazionale sull’Asino. Istituto Zootecnico Sperimentale della Sicilia (IZSS), Palermo, Italy, 21–24 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Panzera, M.; Tropia, E.; Alberghina, D. Aptitude Assessment Test for Donkeys Used in AAI. In Proceedings of the IAHAIO Symposium, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 24–26 October 2018; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Bieber, N. Horseback riding for individuals with disabilities: A personal historical perspective. In Therapeutic Riding I: Strategies for Instruction, Part 1; Engel, B.T., Ed.; Barbara Engel Therapy Services: Durango, CO, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, E.G. Narha–Therapeutic riding in North America. In Therapeutic Riding I: Strategies for Instruction, Part 1; Engel, B.T., Ed.; Barbara Engel Therapy Services: Durango, CO, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lechner, H.E.; Kakebeeke, T.H.; Hegemann, D.; Baumberger, M. Effects of Hippotherapy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 88, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silkwood-Sherer, D.; Warmbier, H. Effects of hippotherapy on postural stability, in persons with multiple sclerosis: A pilot study. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2007, 31, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snider, L.; Korner-Bitensky, N.; Kammann, C.; Warner, S.; Saleh, M. Horseback riding as therapy for children with cerebral palsy: Is there evidence of its effectiveness? Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2007, 27, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterba, J.A. Does Hippotherapy Rehabilitate Children with CP? Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2007, 49, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, L. Walking the Way of the Horse; iUniverse: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, D.; Kahn-D’Angelo, L.; Gleason, J. The effect of hippotherapy on functional outcomes for children with disabilities: A pilot study. Pediatric Phys. Ther. 2008, 20, 264–270. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/pedpt/toc/2008/02030 (accessed on 23 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Debuse, D.; Gibb, C.; Chandler, C. Effects of Hippotherapy: Qualitative Study. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2009, 25, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, M.C.; Reese, N.B. Immediate Effects of Hippotherapy on Gait in CP. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2009, 21, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.-T.; Chen, H.-C.; Tam, K.-W. Systematic Review on EAAT for CP. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, M.; Coltabrigo, L.; Borgi, M.; Cirulli, F.; Luzi, F.; Redaelli, V.; Stefani, A.; Toson, M.; Odore, R.; Vercelli, C.; et al. Equine Assisted Interventions (EAIs): Methodological Considerations for Stress Assessment in Horses. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D. Understanding Animal Welfare: The Science in Its Cultural Context; Kirkwood, J.K., Hubrecht, R.C., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V.; Hager, J.C. Facial Action Coding System; Manual and Investigator’s Guide; Research Nexus: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Berntson, G.G.; Sheridan, J.F.; McClintock, M.K. Multilevel integrative analyses of human behavior: Social neuroscience and the complementing nature of social and biological approaches. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreibig, S.D.; Wilhelm, F.H.; Roth, W.T.; Gross, J.J. Cardiovascular and Emotional Patterns. Psychophysiology 2007, 44, 787–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AWIN. AWIN Welfare Assessment Protocol for Donkeys; University of Milan: Milan, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tarvainen, M.P.; Georgiadis, S.D.; Ranta-Aho, P.O.; Karjalainen, P.A. Time-varying analysis of heart rate variability signals with a Kalman smoother algorithm. Physiol Meas. 2006, 27, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarvainen, M.P.; Niskanen, J.P.; Lipponen, J.A.; Ranta-Aho, P.O.; Karjalainen, P.A. Kubios HRV--heart rate variability analysis software. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2014, 113, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canacoo, E.A.; Avornyo, F.K. Daytime Activities of Donkeys in Ghana. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1998, 60, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, E.D. The Professional Handbook of the Donkey, 4th ed.; Whittet Books: Epping, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Etana, M.; Endeabu, B.; Jenberie, S.; Negussie, H. Determination of reference physiological values forworking donkeys of Ethiopia. Ethiop. Vet. J. 2011, 15, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropia, E.; Alberghina, D.; Rizzo, M.; Alesci, G.; Panzera, M. Monitoring Changes in Heart Rate and Behavioral Observations in Donkeys during Onotherapy Sessions: A Preliminary Study. In Proceedings of the 51st Congress of the International Society for Applied Ethology, Aarhus, Denmark, 7–10 August 2017; ISBN 978-90-8686-311-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zakari, F.O.; Ayo, J.O.; Rekwot, P.I.; Kawu, M.U.; Minka, N.S. Diurnal rhythms of heart and respiratory rates in donkeysof different age groups during the cold-dry and hot-dryseasons in a tropical savannah. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galardi, M.; Contalbrigo, L.; Toson, M.; Bortolotti, L.; Lorenzetto, M.; Riccioli, F.; Moruzzo, R. Donkey assisted interventions: A pilot survey on service providers in North-Eastern Italy. Explore 2002, 18, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artemiou, E.; Hutchison, P.; Machado, M.; Ellis, D.; Bradtke, J.; Pereira, M.M.; Carter, J.; Bergfelt, D. Impact of human-animal interactions on psychological and physiological factors associated with veterinary school students and donkeys. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 701302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).