Simple Summary

Heat stress causes significant economic loss due to its multiple adverse effects on the health and performance of rabbits, including gastrointestinal disturbances, impaired immunity, oxidative stress, and organ damage, leading to deteriorating production performance. Nutritional strategies, such as dietary supplements, have proven their effectiveness in mitigating the negative effects of heat stress on animals. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to evaluate the synergetic effect of adding Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis) and nano-encapsulated cumin oil to mitigate the impacts of heat stress on the performance and health of growing rabbits. Incorporating B. subtilis and nano-encapsulated cumin oil into rabbit diets may mitigate the negative effects of heat stress by improving growth performance and feed efficiency, increasing antioxidant capacity and digestive enzyme activity, and modifying gut microbiota and gene expression associated with gut health. Therefore, it represents a promising nutritional strategy for rabbits under high temperatures.

Abstract

The study evaluated the influence of dietary supplementation with nano-encapsulated cumin oil, B. subtilis, or a combination of both to mitigate the impacts of heat stress on the performance and health of growing rabbits. In the feeding trial, a total of eighty-four growing New Zealand White (35 days, 781.3 ± 1.8 g average body weight) were randomly distributed in a completely randomized design into four groups; each had 21 rabbits arranged in 7 replicates (3 rabbits each). The experiment lasted 42 days (35 days to 77 days). Growing rabbits received a basal diet (first group, CON) without additives, while the other groups were supplemented with nano-encapsulated cumin oil (NECO, 200 mg/kg), B. subtilis (BS, 500 mg/kg), or both (BSNO, 500 mg BS plus 200 mg/kg NECO). Adding BSNO significantly enhanced body weight gain, carcass weight, and feed conversion ratio and reduced mortality rate (p < 0.05). Additionally, the BSNO enhanced digestive system performance by increasing the secretion of trypsin enzymes, as well as nutrient digestibility, especially for protein and fiber (p < 0.05). Supplementing BSNO enhanced oxidative stability and immunity via higher levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD), IgA, IgG, triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4) and lower malondialdehyde (MDA) levels (p < 0.05), indicating a better ability to adapt to stress. During the examination of gut health, pathogenic bacteria counts decreased, as well as down-regulation of interleukin-6 (IL-6) gene expression and up-regulation of cationic amino acid transporter-1 (CAT-1), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and mucin-2 (MUC-2) gene expression (p < 0.05), supporting gut integrity. This study highlights the potential of mixing nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis in growing rabbits’ diets as an effective strategy to counteract the negative effects of heat stress caused by high ambient temperatures.

1. Introduction

Environmental stress is one of the constraints to animal production [1]. Among these pressures is heat stress, which causes numerous adverse health effects on rabbits, resulting in significant economic losses in the rabbit industry [2]. Rabbits are unable to dissipate excess heat due to their limited number of sweat glands, making them more susceptible to heat stress. Oxidative stress, impaired immunity, and endocrine deregulations [1], as well as reproductive disorders and organ damage [3], are among the most important symptoms of heat stress in rabbits, which decline in their production performance and an increase in the mortality rate [4]. Additionally, rabbit breeders suffer from some problems during the weaning period, including a high mortality rate, which is attributed to intestinal disorders and impaired immunity [5]. The transition of rabbits from liquid milk to solid feed during the weaning period can be one of the main causes of intestinal disorders such as flatulence, diarrhea, or constipation [6]. Recently, feeding strategies have been a major factor in mitigating heat stress and weaning problems [2,3,7]. Nutritional manipulation through the use of functionally effective additives has played a positive role in resolving many of the obstacles facing rabbit breeding, such as herbs, the addition of vitamins, minerals, essential oils, probiotics, organic acids, etc. [8,9,10,11].

Probiotics are among the feed additives that have become widely used in animal feed due to their many benefits [8,9]. B. subtilis is a key component of most probiotic formulas (withstands harsh conditions) due to its many properties, including antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, blood metabolic profile, and immunomodulatory properties [12,13], as well as the production of some enzymes that enhance feed efficiency [14]. Additionally, it modulates the metabolism of amino acids and vitamin B [13] and enhances disease resistance [12,15].

Several recent reports have revealed the benefits of incorporating medicinal and aromatic plants and their products (essential oils) as sustainable and natural alternatives to traditional feed additives in rabbit nutrition [14]. Analyses of various medicinal and aromatic plants have revealed a diverse array of biologically active compounds that play a key role in the numerous positive properties [8,16] that have the potential to enhance rabbit health. The proven properties of these biologically active compounds include antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties [14]. Cuminum cyminum L. is a distinctively flavored herb belonging to the Apiaceae family [17]. Cuminum cyminum L. and its essential oil contain Cuminaldehyde and p-Cymene, γ-Terpinen, the biologically active compound responsible for most of the oil’s properties [18], which include antibacterial, antioxidant, and antifungal properties [17].

In recent years, there has been an increased focus on nanotechnology due to its many benefits, including enhanced bioavailability, stability, cellular uptake of nutrients, and solubility [7,19], which make it more effective than the base material. This is similar to the case with essential oils, where numerous studies have documented the positive role of converting pure essential oils to nano-emulsified essential oils [17], making them more effective as animal feed additives [18,19] by enhancing the antioxidant and antibacterial properties of essential oils.

Nutritional manipulation through a feed additives strategy had a positive effect on mitigating environmental stress and disease resistance in animals. Therefore, this study aimed to use B. subtilis and nano-emulsified cumin essential oil to alleviate the effects of heat stress and weaning problems in weaned rabbits. This combination was selected to evaluate the potential synergistic effects in alleviating the impacts of heat stress in rabbits, as B. subtilis may enhance intestinal colonization and enzyme secretion [12,13], while essential oils provide antimicrobial and antioxidant protection [19], together supporting better intestinal integrity and metabolic function, as well as enhancing performance in rabbits under heat stress. Thence, the current study evaluated the effect of supplementing B. subtilis and nano-emulsified cumin oil and their blend on growth performance, carcass characteristics, hematological parameters, immune response, gut microbiota, and gene expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Materials

Bacillus subtilis was obtained from the Microbiology Department, Faculty of Agriculture, Ain Shams University, Egypt. Nano-encapsulated cumin essential oil was synthesized by the author from the National Research Centre, Egypt. From pure life for investment and agricultural development in Cairo, Egypt, cumin essential oil (CEO) was purchased. Tween 80 and sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) were purchased from Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO, USA.

2.2. Synthesis of Nano-Encapsulated Cumin Oil (NECO)

The nano-encapsulation of cumin essential oil (CEO) was carried out using the ionic gelation method according to López-Meneses et al. [20]. Chitosan (1 mg/mL; derived from crab shells) was dissolved in a water bath at 60 °C in 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution with constant stirring until complete dissolution to obtain a 1.0 mg/mL stock solution, and the pH was adjusted to 4.8 using a solution of NaOH (3 N), then Tween 80 was added into the chitosan solution under magnetic stirring (800 rpm) for 10 min. The CEO was then gradually incorporated into the mixture with continuous stirring for half an hour. Thereafter, dropwise (1 mL/min) addition of sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) solution (1.0 mg/mL in deionized water) was added at a 4:1 (w/w) chitosan: TPP ratio while being constantly stirred for 30 min/RT. To improve homogeneity and decrease particle size, the resultant suspension was sonicated for 10 min using an ultrasonic probe sonicator. To guarantee the nanoparticles’ suitability for dietary use in rabbits, every step of the preparation process was carried out in a sterile environment. The chemical composition of cumin essential oil (CEO) was investigated using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS), and specific constituents were identified by contrasting their mass spectra with reference spectra as per Bai et al. [21] (Table 1). A Nano-ZS ZEN analyzer (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) was used to characterize the generated nanoemulsion to measure the particle size, zeta potential, and polydispersity index (PDI). Having a zeta potential of +24.2 mV, a PDI of 0.183, and an average droplet size of 92.3 nm, the produced nanoparticles demonstrated satisfactory stability and uniform distribution at the nanoscale.

Table 1.

Chemical Composition of the CEO.

2.3. Rabbits, Experimental Design, and Diet

The experiment animals were provided from Ras Sadr Station, Desert Research Center, and the experiment was conducted in accordance with the Animal Care and Experimental Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Agriculture, Ain Shams University, and Desert Research Center, Egypt. All protocols were implemented in accordance with the International Guideline for the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes.

In a feeding experiment that started at 35 days of old (average body weight 781.3 g) and continued until 77 days of old, eighty-four growing New Zealand White (NZW) rabbits were divided into four groups (21 rabbits/group), and each of seven replicates (3 rabbits/replicate) was randomly assigned. The first group (control, CON) was fed on a basal diet, the second, third, and fourth groups were fed on the basal diet added with B. subtilis (BS, 500 mg/kg), nano-encapsulated cumin oil (NECO, 200 mg/kg), and a mixture of B. subtilis and nano-encapsulated cumin oil (BSNO, 500 mg and 200 mg/kg diet, respectively). The selected doses were based on previous studies showing beneficial effects of similar levels of B. subtilis [22] and essential oils [23] on growth performance, gut health, and antioxidant status in poultry. A pelleted diet and clean, fresh water were offered ad libitum. Growing rabbits were reared during the summer at Ras Sadr Station, Desert Research Center, Egypt. The nutritional needs of the experimental rabbits were met by formulating experimental diets according to the recommendations of the National Research Council [24] (Table 2). The required amount of nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis (1 × 106 CFU/g feed) spores was blended with a small portion of the basal feed to form a premix. This premix was then thoroughly mixed with the remaining feed using a mechanical mixer to ensure uniform distribution, before pelleting. The treated feed was prepared weekly to maintain the stability and activity of the additives and stored in airtight containers at room temperature under dry conditions. To calculate the temperature-humidity index (THI) [25], daily temperature and humidity were recorded at 10:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m. The THI was used to determine the rabbits’ stress levels: <27.8 indicates no heat stress, 27.8 to 28.9 indicates moderate heat stress, 29.0 to 30.0 indicates severe heat stress, and >30.0 indicates extremely severe heat stress. According to Shebl et al. [26] one rabbit or duplicate’s respiratory rate (RR/min) and pulse rate (PR/min) were determined by counting the movements of the chest fleece and using a finger to count the pulses in the femoral artery, respectively.

Table 2.

Composition of basal diet for rabbits and chemical analysis.

2.4. Performance Index

At 56 and 77 days of age, live body weight (LBW), Daily feed intake (DFI), and daily mortality were noted. Body weight gain (BWG) and feed conversion ratio (FCR) were computed. Mortality was monitored daily throughout the 6-week experimental period. Dead rabbits were immediately removed, and any signs of disease or injury were documented. The number of surviving rabbits in each pen was recorded weekly to calculate cumulative mortality and survival rates. In measuring performance and mortality rate, the pen was considered the experimental unit. One rabbit was chosen at random from each replicate in the experimental group (seven rabbits per group) at the end of the 6-week experiment, weighed separately, and slaughtered for carcass examination. At the end of the experiment (77 days), one rabbit was randomly selected from each replicate in the experimental group (five rabbits/group), weighed individually, and slaughtered to evaluate the targeted experimental parameters. The carcass, lungs, liver, kidneys, heart, and giblets were weighed, and the total edible parts were calculated based on Ghosh and Mandal [27]. Additionally, after the experiment concluded, one rabbit/replicate (seven from the group) was placed in metabolic cages. Before the collection period, the rabbits were kept for 24 h to acclimatize. After four days of collection, the feces were ground up, dried at 65 °C for 48 h, and kept in polyethylene bags at −10 °C until they could be subjected to chemical tests. In accordance with AOAC procedures, the feed and feces were examined for dry matter, crude fiber, ether extract, crude protein, and nitrogen-free extract [28]. Samples were obtained from the duodenum at 77 days of age at slaughter in order to measure the activity of digestive enzymes. According to Abdel Moneim et al. [29], specific commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) were used to measure the activities of trypsin, cellulase, and amylase.

2.5. Biochemical Analysis

Blood samples were taken in anticoagulant-free tubes during slaughtering (at 77 days of age), centrifuged for 15 min at 3000× g, and serum was taken and kept at −20 °C. High-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), cholesterol, glucose, triglycerides, total protein, and albumin levels were determined calorimetrically using an auto-analyzer system by using commercially available kits (Spinreact Co., Ltd., Girona, Spain). Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were measured to assess liver function. Thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) were assayed using radioimmunoassay (RIA) kits as described by Ibrahim et al. [30]. The commercial kits from Bio Diagnostic Company (Giza, Egypt) were used to specify the levels of glutathione peroxidase (GPx), malondialdehyde (MDA), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in the serum. In addition, using ELISA kits, blood concentrations of IgG, IgM, and IgA were estimated (Life Diagnostics Inc., West Chester, PA, USA).

2.6. Cecum Microbial Enumeration

At slaughter, 10 g of the cecum of seven experimental rabbits/group was collected, and the samples were stored at −20 °C after being placed in sterile bags until the required analysis. Necessary dilutions were made of the cecal samples and grown on agar suitable for each microbe under the required temperature and aerobic or anaerobic conditions. Lactobacillus, Escherichia coli (E. coli), and Clostridium perfringens (C. perfringens) bacteria were enumerated (MRS agar, Egg yolk emulsion (50%), and MacConkey agar, respectively). The microbiota count was calculated as log 10 colony-forming units per gram of cecal digesta.

2.7. mRNA Gene Expression

At the end of the experimental period, 28 growing rabbits (7 rabbits per group, injected with sodium pentobarbital) were sacrificed for cecal tissue sampling to estimate the effect of experimental supplementation on the gene expression of both cationic amino acid transporter-1 (CAT-1) and mucin-2 (MUC-2), in addition to cytokines including interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-10 (IL-10). Total RNA suspension was extracted from the cecal membranes and then homogenized, visualized, and quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (BMG Lab Tec. GmbH, Offenburg, Germany); all procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After the amplification of cDNA, the specificity of the amplification was assessed by performing a dissociation curve of the real-time polymerase chain reaction (7500 Fast Real-time PCR) products. The forward and reverse primers for CAT-1 were F: CCAGTCTATTAGGTTCCATGTTCC and R: CGATTATTGGCGTTTTGGTC (Accession number XM_002721425.3); MUC-2, F: TATACCGCAAGCAGCCAGGT and R: GCAAGCAGGACACAGACCAG (Accession number L41544.1); IL-10, F: AAAAGCTAAAAGCCCCAGGA and R: CGGGAGCTGAGGTATCAGAG (NM_001082045.1) for IL-6, F: ACGATCCACTTCATCCTGCG and R: GGATGGTGTGTTCTGACCGT (NM_001082064.2). Additionally, GAPDH, F: TGTTTGTGATGGGCGTGAA and R: CCTCCACAATGCCGAAGT (DQ403051.1). The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to determine the relative expression levels of MUC-2, CAT-1, IL-6, and IL-10 genes [31].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed by ANOVA using the general linear model procedure of SPSS (19.0) as randomized complete design (CRD). Following a significant F-test, Tukey’s post hoc test was employed to determine the statistically significant differences between the experimental groups under heat stress. Survival data were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier estimates and compared among treatments with a log-rank test, while pen-level mortality proportions were evaluated using the Kruskal–Wallis test, considering the pen as the experimental unit. Shapiro–Wilk tests were used to assess homogeneity and normality between experimental groups, respectively. Since p < 0.05, these differences were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Rabbit Welfare

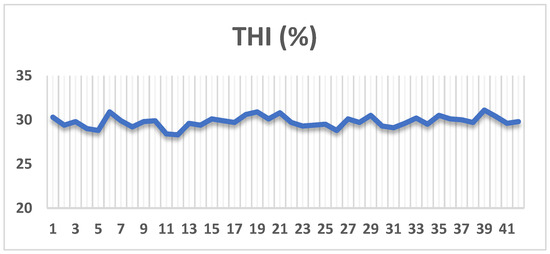

The rabbits were exposed to heat stress, as indicated by the THI value, which varied between 29.2 and 30.3 during the entire experimental period (Figure 1). The HR and RR analysis was performed on 24 male rabbits (7 rabbits/group), with the range for HR was 152 to 197 beats/min, while the range for RR was 81 to 106 breaths/min.

Figure 1.

Temperature-humidity index (THI).

3.2. Performance

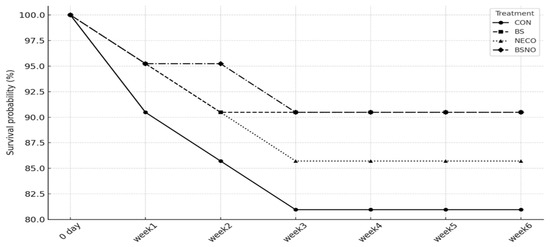

Results of the performance index (growth and carcass traits) of rabbits fed B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture during heat stress are shown in Table 3 and Table 4. During all experimental phases, BWG decreased and FCR deteriorated (p < 0.05), while daily feed intake was unaffected in rabbits that did not receive experimental supplements under heat stress (Table 3). During the periods from 35 to 56 days, DFI was not affected, while BWG tended to increase in the BS, NECO, and BSNO groups (p < 0.05) compared to the control group. However, FCR significantly decreased in the BSNO group compared to the other groups. During the periods of 57–77 days, BWG increased in the BS, NECO, and BSNO groups (p < 0.05) compared to the control groups, while the highest BWG was in the BSNO group. In the same context, FCR significantly decreased in rabbits receiving BS and BSNO compared to the NECO and control groups (p < 0.05), while DFI was not affected. During the total experimental period (35–77 d), BWG significantly increased in the BS and BSNO groups (p < 0.05) compared to the control and NECO groups, while DFI remained unchanged between the experimental groups (p < 0.05). In addition, FCR was significantly decreased in rabbits receiving BS, NECO, and BSNO compared to the control group; however, the best FCR was in rabbits receiving BSNO. Additionally, carcass weight increased in rabbits receiving BSNO compared to the other groups (p < 0.05); however, other carcass characteristics, such as heart, kidney, lung, liver, giblets, and TEP, were not affected by the experimental treatments (Table 4). Furthermore, the mortality rate was significantly (p < 0.05) reduced in rabbits receiving BS and BSNO during the entire rearing period compared to the control group (Figure 2). Cumulative mortality over six weeks ranged from 9.5% to 19.0% (CON 19.0%; NECO 14.3%; BS 9.5%; BSNO 9.5%; n = 21/treatment). Kaplan–Meier survival at week 6 was 81.0% (CON), 85.7% (NECO), and 90.5% (BS and BSNO). Survival curves did not differ significantly among treatments (log-rank χ2 = 1.52, df = 3, p = 0.6765). Pen-level mortality proportion also showed no treatment effect (Kruskal–Wallis H = 3.40, df = 3, p = 0.3340). Directionally, CON had the highest losses, whereas BS and BSNO showed the lowest losses, with NECO intermediate.

Table 3.

Effect of B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture supplementation on growth performance of growing rabbits.

Table 4.

Effect of B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture supplementation on carcass characteristic of growing rabbits at 77 d.

Figure 2.

Effect of B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture supplementation on mortality percentages of growing rabbits. CON: rabbits fed a basal diet without a feed additive (control diet), BS: control diet plus B. subtilis (500 mg/kg), NECO: control diet plus nano-encapsulated cumin oil (200 mg/kg), BSNO: control diet plus B. subtilis and nano-encapsulated cumin oil. Kaplan–Meier survival over six weeks for CON, BS, NECO, and BSNO. No overall difference among curves (log-rank χ2 = 1.52, df = 3, p = 0.6765).

3.3. Digestive System Performance

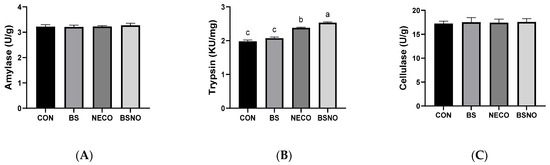

Results of the digestive system performance (digestibility coefficients and digestive enzyme activity) of rabbits fed B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture during heat stress are shown in Table 5 and Figure 3A–C. Dry matter digestibility increased in rabbits receiving BS and BSNO compared to rabbits receiving CON and NECO groups (p < 0.05). Additionally, crude protein and crude fiber digestibility increased (p < 0.05) in rabbits receiving BSNO, BS, and NECO compared to the control group; whereas, the best digestibility of crude protein and crude fiber was in rabbits receiving BS and BSNO (p < 0.05). However, the digestion of ether extract and NFE was not affected (p < 0.05) among rabbits in the experimental groups. The activity of digestive enzymes, such as cellulase and amylase, was not affected by the experimental treatments (p < 0.05), except for trypsin, which significantly increased in rabbits receiving NECO and BSNO compared to those receiving CON and BS.

Table 5.

Effect of B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture supplementation on digestibility coefficients (%) of growing rabbits at 77 d.

Figure 3.

Effect of B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture supplementation on digestive enzyme activity (amylase (A), trypsin (B), and cellulase (C)) of growing rabbits at 77 d. CON: a basal diet without a feed additive (control diet), BS: control diet plus B. subtilis (500 mg/kg), NECO: control diet plus nano-encapsulated cumin oil (200 mg/kg), BSNO: control diet plus B. subtilis and nano-encapsulated cumin oil. Values with different superscript letters are statistically different.

3.4. Serum Biochemistry

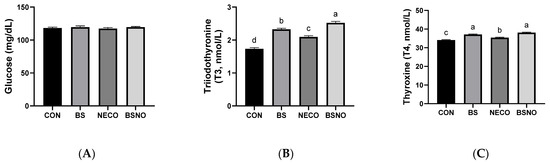

Results of the biochemical analysis (lipid profile, liver integrity, and stress index) of rabbits fed B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture during heat stress are shown in Table 6 and Figure 4A–C. Total protein levels increased in rabbits fed NECO and BSNO compared to the other groups (p < 0.05). Likewise, HDL levels also increased in rabbits fed BS, NECO, and BSNO compared to the control group (p < 0.05), while triglycerides and cholesterol levels decreased in rabbits fed BS, NECO, and BSNO compared to the control group (p < 0.05, Table 6). Nevertheless, albumin and LDL levels were unaffected between experimental treatments. To assess liver health, ALT and AST levels were measured; our results showed a decrease in AST levels in rabbits receiving BSNO, NECO, and BS compared to the control groups; however, the lowest AST level was in the BSNO group. However, ALT levels were not affected among experimental treatments (p < 0.05, Table 6). Among the stress markers that showed improvement with the addition of experimental supplements were thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). The results showed an increase in T4 and T3 levels in rabbits fed BS, NECO, and BSNO compared to the control group, while glucose levels were unaffected between the experimental groups (p < 0.05, Figure 4).

Table 6.

Effect of B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture supplementation on blood biochemical profile (%) of growing rabbits at 77 d.

Figure 4.

Effect of B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture supplementation on glucose and thyroid activity (glucose (A), triiodothyronine (T3, (B)), and thyroxine (T4, (C)) of growing rabbits at 77 d. CON: a basal diet without a feed additive (control diet), BS: control diet plus B. subtilis (500 mg/kg), NECO: control diet plus nano-encapsulated cumin oil (200 mg/kg), BSNO: control diet plus B. subtilis and nano-encapsulated cumin oil. Values with different superscript letters are statistically different.

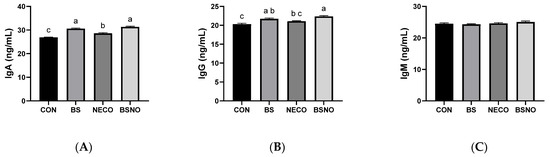

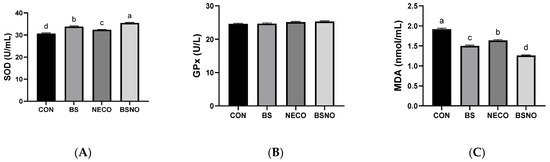

3.5. Immuno-Antioxidant Status

Figure 5 and Figure 6 show the effect of B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture on immune status and oxidative stress indicators. IgA levels increased in the BS, NECO, and BSNO groups compared to the control group (p < 0.05, Figure 5A). Similarly, IgG levels increased in the BS and BSNO groups compared to the control and NECO groups (p < 0.05); however, IgM levels were not affected among the experimental groups (Figure 5B,C). Additionally, SOD activity significantly increased and MAD levels decreased in rabbits fed a diet containing BS, NECO, and BSNO compared to rabbits fed a control diet (p < 0.05), while GPx levels were unaffected by the experimental treatments (Figure 6A,B). Rabbits receiving BSNO also showed higher SOD activity and lower MAD levels than the other groups (p < 0.05, Figure 6C).

Figure 5.

Effect of B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture supplementation on immune status (IgA (A), IgG (B), and IgM (C)) of growing rabbits at 77 d. CON: a basal diet without a feed additive (control), BS: control diet plus B. subtilis (500 mg/kg), NECO: control diet plus nano-encapsulated cumin oil (200 mg/kg), BSNO: control diet plus B. subtilis and nano-encapsulated cumin oil. Values with different superscript letters are statistically different.

Figure 6.

Effect of B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture supplementation on oxidative stress indicators (superoxide dismutase (SOD, (A)), glutathione peroxidase (GPx, (B)), and malondialdehyde (MDA, (C)) of growing rabbits at 77 d. CON: a basal diet without a feed additive (control diet), BS: control diet plus B. subtilis (500 mg/kg), NECO: control diet plus nano-encapsulated cumin oil (200 mg/kg), BSNO: control diet plus B. subtilis and nano-encapsulated cumin oil. Values with different superscript letters are statistically different.

3.6. Microbial Enumeration

Table 7 shows the effect of experimental supplements on the intestinal microbial content of rabbits exposed to heat stress. Lactobacillus counts increased and E. coli counts decreased in the BS, NECO, and BSNO groups compared to the control group (p < 0.05), while the lowest E. coli counts and highest Lactobacillus content were in the BSNO group (p < 0.05). Similarly, C. perfringens counts decreased (p < 0.05) in the BS and BSNO groups compared to the control and NECO groups.

Table 7.

Effect of B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture supplementation on cecum microbial enumeration (Log10 CFU g−1) of growing rabbits at 77 d.

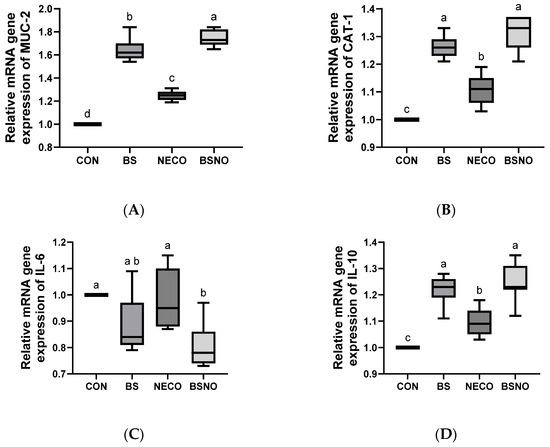

3.7. Gene Expression

Experimental supplements showed a positive effect on intestinal gene expression in rabbits exposed to heat stress, as shown in Figure 7A–D. Gene expression of MUC-2, CAT-1, and IL-10 increased in the BS, NECO, and BSNO groups compared to the control group (p < 0.05), while MUC2 gene expression was highest in the BSNO group, also CAT-1 and IL-10 gene expression was highest in the BS and BSNO groups (p < 0.05). Additionally, IL-6 gene expression decreased in the BSNO groups compared to the control, BS, and NECO groups (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Effect of B. subtilis, nano-encapsulated cumin oil, and their mixture supplementation on intestinal gene expression (mucin-2 (MUC-2, (A))), cationic amino acid transporter-1 (CAT-1, (B)), interleukin-6 (IL-6, (C)) and interleukin-10 (IL-10, (D)) of growing rabbits at 77 d. CON: a basal diet without a feed additive (control diet), BS: control diet plus B. subtilis (500 mg/kg), NECO: control diet plus nano-encapsulated cumin oil (200 mg/kg), BSNO: control diet plus B. subtilis and nano-encapsulated cumin oil. Values with different superscript letters are statistically different.

4. Discussion

Recently, there has been increased interest in nutritional manipulation as a novel strategy to improve the health, performance, and efficiency of rabbits against the effects of heat stress [3]. Feed additives such as a mixture of B. subtilis and nano-encapsulated cumin oil could be an effective additive to alleviate the harmful effects of heat stress in rabbits. In particular, the results of the current study showed that rabbits were exposed to heat stress through increased THI values, accompanied by increased respiratory and pulse rates. Notably, both RR and PR increased significantly during periods of high THI, reflecting the rabbits’ thermal sensitivity to high ambient temperature and humidity, which puts them at risk for heat stress. It is interesting to note that the addition of B. subtilis and nano-encapsulated cumin oil mixture alleviated the harmful effects of heat stress in rabbits, which may be due to their multiple biological properties, including interaction with the gut environment, immunomodulatory activities, antioxidant system, and antimicrobial activity.

The results of the current study showed a significant improvement in growth performance in rabbits receiving a mixture of B. subtilis and nano-encapsulated cumin oil during heat stress via increased BWG and decreased FCR. Consistent with our study, growth performance was enhanced in rabbits fed a diet including probiotics [32]. Likewise, feeding rabbits a diet containing essential oils significantly improved body weight and feed conversion ratio and decreased the mortality rate [19,33,34]. In a similar study, Alimohamadi et al. [35] found that adding cumin powder and probiotics to the diet significantly improved broilers’ growth performance. The improved growth of heat-stressed rabbits fed essential oils can be attributed to the role of bioactive compounds (such as cuminaldehyde, γ-terpinene, and β-pinene) in nano-encapsulated cumin oil [17]. This can be attributed to several mechanisms, including the stimulation of digestive enzyme secretion and the production of bile acids, which enhance digestion and nutrient absorption [17,18,36]. Furthermore, they have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [33,37], promote the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut [18], modify intestinal morphology [19], and enhance the activity of digestive enzymes [8,23], thereby increasing feed utilization and improving growth. Additionally, several previous reports have shown that adding B. subtilis to the diets of animals alters the balance of intestinal microbes, modifies and stimulates immune function [16,38], competes for chemicals and adhesion sites on epithelial cells [12,39], as well as produces compounds that inhibit the growth of pathogenic microbes [17], thus enhancing rabbit health and performance. However, some reports purport that essential oils did not affect growth performance in broiler chickens [40,41]. This discrepancy between study results may be attributed to the chemical composition of the essential oils used, the extraction method, the amounts added, the conditions of addition, the animal type and age, and the experimental conditions. From the above, it is clear that the synergistic effect of nano-encapsulated cumin oil with B. subtilis supplementation in enhancing intestinal integrity, oxidative stability, immune response, and intestinal microbial modification is evident, which increases the availability of nutrients and the activity of digestive enzymes. Therefore, the addition of the mixture can play an effective role in enhancing antioxidant defenses, gut health, and nutrient efficiency, supporting the animals’ ability to adapt to heat stress, leading to improved growth performance and significantly reduced mortality rates in growing rabbits exposed to heat stress.

Despite the significant improvement in growth performance, this study found that carcass characteristics were not affected except for carcass weight, which increased in rabbits fed a diet containing a mixture of nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis. Yilmaz and Gul [35] found an increase in carcass weight in stressed broilers fed a diet including cumin essential oil, which is in agreement with our results. Additionally, Fathi et al. [42] and Mohamed et al. [43] indicated that carcass characteristics of rabbits receiving dietary probiotics, whether B. subtilis or a mixture of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum, improved; however, Tufarelli et al. [44] did not find an effect of probiotic supplements on carcass characteristics. Variations in essential oil type, concentration, and experimental conditions may explain the inconsistent findings. Some reports indicate that the positive role of probiotic supplements in enhancing carcass weight may be due to their effect on the weight and function of the digestive system [33], as well as the cecum microbial fermentation pattern in rabbits [13], which increases nutrient availability, as well as adding essential oil enhancing activity of digestive enzymes and digestion of nutrients [17,37], thus supporting carcass weight gain.

Data from the current study indicated a decrease in the digestibility of nutrients in rabbits with increasing ambient temperature, which is confirmed by many previous reports [3]. Moreover, the results of the current study showed that adding a nano-encapsulated cumin oil with B. subtilis mixture increased the digestibility of fiber and protein and secretion of trypsin enzymes. Consistent with these findings, Elbaz et al. [8] and Phuoc and Jamikorn [16] reported significantly increased digestibility of crude fiber and protein in chickens fed a diet including essential oils or probiotics. The positive effect of the mixture may be attributed to the role of the probiotic in promoting gut health by modifying the microbial content, reducing inflammation, and enhancing oxidative stability and intestinal morphology [33,45]. In agreement with our findings, some reports indicate that essential oils, through their bioactive compounds, stimulate the secretion of digestive enzymes, which enhances nutrient digestibility [46,47]. These compounds stimulate the secretion of digestive hormones (such as cholecystokinin (CCK) and secretin), which activate pancreatic exocrine function, enhance enzyme synthesis, and bile acids, improving lipid and carbohydrate digestion [19,48]. Improving gut health (improving gut morphology, reducing pathogenic bacteria, and oxidative stress) and enhancing nutrient signaling also stimulates the pancreas to increase digestive enzyme production [46,49], creating a more favorable environment for nutrient digestion and absorption. Additionally, its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties protect intestinal and pancreatic tissue, contributing to overall gut health and stimulating pancreatic activity, which together increase the synthesis and secretion of digestive enzymes [48,49]. This demonstrates the effective effect of adding a combination of nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis to enhance nutrient digestion, thus improving feed utilization and performance in heat-stressed rabbits.

The results of the current study indicate that the addition of nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis has a significant effect on protein, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism in heat-stressed rabbits. Nano-encapsulated cumin oil with B. subtilis mixture reduced lipid metabolism, while enhancing protein metabolism, as demonstrated by increased serum total protein and HDL levels and decreased triglycerides and cholesterol levels. A similar study demonstrated that the addition of essential oils had a significant effect on decreasing levels of LDL, triglycerides, and cholesterol [10,34,35]. Moreover, Tufarelli et al. [50] reported that the addition of probiotics played an effective role in modifying fat metabolism in poultry during heat stress by reducing levels of triglycerides and cholesterol. The lipid-lowering effects of the blend of probiotic and essential oil can be attributed to the blend’s ability to improve lipid metabolism and digestion [37] through several mechanisms, like negatively impacting the activity of enzymes involved in cholesterol synthesis and metabolism (cholesterol 7-alpha-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR) [46,47]. Additionally, heat stress leads to an increase in free radicals and a decrease in antioxidant defenses, causing oxidative damage that harms the liver [2]. To confirm the impact of heat stress and experimental supplements on liver function and health, levels of liver enzymes such as AST and ALT were measured. Our results showed decreased AST levels in rabbits that received a nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis mixture. On the other hand, adding experimental supplements in the current study mitigated these harmful effects on the liver by reducing plasma AST levels [50]. In the same context, Moustafa et al. [51] found that adding essential oils reduced the AST level in chickens subjected to heat stress. The lower AST levels in poultry receiving essential oils may be attributed to the beneficial effects of bioactive compounds, including preventing protein degradation, increasing the production of antioxidant enzymes, and improving the functions and integrity of tissues and organs [16,19]. Moreover, the bioactive compounds in essential oils possess strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that exert hepatoprotective effects by stabilizing cell membranes, reducing oxidative damage in the liver, and thereby preventing the leakage of intracellular enzymes such as AST into the bloodstream [52]. These findings indicate that the addition of the mixture may have a positive effect on hepatic function and health.

Additionally, the many negative effects of heat stress on glandular performance reduce thyroid activity and consequently reduce the production of its hormones, namely triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4), which leads to a decrease in energy production and metabolic rate [53], which contributes to weakening immune function, deterioration of general health, and decreased growth. This is part of a physiological adaptation: reducing basal metabolic rate to decrease internal heat production [3]. The results are consistent with previous reports, where T3 and T4 levels were decreased in rabbits exposed to heat stress and fed a diet without additives [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54], as in the present study. However, T3 and T4 levels increased in rabbits that received nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis mixture. Several previous reports support the beneficial effect of probiotic supplements and essential oils in maintaining thyroid function by increasing the production of thyroid hormones [22,54], which enhances nutrient metabolism and improves growth performance. Combining probiotics with essential oils may have synergistic effects in supporting endocrine function, including the thyroid. Probiotics may help maintain or restore thyroid hormone levels by mitigating these effects by reducing stress (e.g., corticosterone) [29,38], improving gut health, and enhancing nutrient absorption. Besides that, essential oils reduce oxidative and inflammatory damage, protect cellular integrity (including thyroid tissue), and support metabolic function [19,33,35]. Some studies combining probiotics with essential oils show improvements in metabolic biomarkers, growth performance, and overall health in chickens [5,55].

One of the most significant harms of heat stress is the decrease in antioxidant defenses and the increase in free radicals, which cause oxidative damage that affects many organs, including the liver and intestines, as well as lipid peroxidation [33,36]. Antioxidant enzymes are the primary line of defense to reduce the damage caused by oxidative stress. The results of the current study showed that adding a nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis mixture increased the activity of antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD. In agreement with our results, several studies have reported that the addition of probiotics or essential oils enhanced the oxidative status by increasing antioxidant enzymes, including SOD, GPx, and TAC [22,56]. In addition, previous studies have shown that several experimental supplements, including essential oils and probiotics, had a beneficial effect in maintaining cell integrity during heat stress in rabbits or chickens, as indicated by decreased MDA levels [44,56,57], which is consistent with our results. Cumin essential oil is rich in bioactive compounds with powerful free radical scavenging properties [17]. These compounds directly neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS), as well as stimulate the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway, which regulates gene expression encoding antioxidant enzymes [58,59,60], improving oxidative stability and the rabbit’s ability to tolerate heat stress conditions. Meanwhile, B. subtilis improves gut health and nutrient absorption, enhancing rabbits’ oxidant stress by suppressing harmful microbes, thereby reducing reactive oxygen species. Furthermore, B. subtilis can produce several compounds (such as exopolysaccharides, short-chain fatty acids, and certain enzymes) [12,29] that stimulate antioxidant activity in rabbits. The addition of nano-encapsulated cumin oil with B. subtilis mixture may have a protective role against heat stress by supporting oxidative stability in growing rabbits.

In this study, we investigated whether adding nano-encapsulated cumin oil with B. subtilis mixture supplements could enhance immune responses in heat-stressed rabbits. Therefore, immunoglobulin levels were assessed as indicators of the effectiveness of these supplements on immune responses, especially since immunoglobulins are present in the mucosal regions of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts, which limits the colonization of pathogens. The current study showed that immunoglobulin levels increased significantly, particularly IgG and IgA, when supplemented with nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis mixture to rabbit diets under heat stress. Similar results were found by Abdel-Moneim et al. [57] and Humam et al. [60], with increased levels of IgA and IgG in the blood of rabbits receiving probiotics. Similarly, Elbaz et al. [22,61] found that chickens receiving a mixture of essential oils and probiotics increased IgG levels. Cumin essential oil is characterized by its potent bioactive compounds, which have immunomodulatory properties. They help neutralize ROS and reduce oxidative stress [58], thus preserving immune cell function. They also stimulate cytokine secretion and the activity of macrophages and lymphocytes, leading to improved humoral and cellular immune responses [12,14]. Additionally, B. subtilis acts as an effective probiotic immunomodulatory by improving intestinal microbial balance and stimulating the gut-associated lymphoid tissue [62,63], the primary site of immune regulation in poultry. The addition of B. subtilis also enhances B-lymphocyte proliferation and antibody synthesis, leading to increased levels of immunoglobulins (IgA, IgG, and IgM), as well as strengthening the intestinal mucosal barrier by increasing the production of secretory immunoglobulin (sIgA), which represents the first line of defense against intestinal pathogens [62]. From the above, the observed improvement in immune response may be attributed to the antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties of nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis mixture [14,39], which helps in providing nutrients and thus promoting the proliferation of lymphocytes in primary immune organs and enhancing intestinal integrity [64], thus stimulating the production of immunoglobulins and the immune response.

Heat stress damages the intestine by changing the microbial community (increasing harmful bacteria), immune response, and gene expression of the intestinal barrier [3], thus damaging the intestinal barrier, epithelial cells, and microstructure, which negatively affects the function of the digestive system in digesting and absorbing nutrients [65], leading to poorer rabbit performance. This is consistent with our results, where the number of harmful microbes (C. perfringens and E. coli) increased and the expression of intestinal integrity-related genes declined. Creating a healthy digestive environment is essential for rabbits to maintain their health and productive performance [3,9], as well as to resist intestinal disturbances and environmental changes through experimental supplements. Furthermore, several reports have indicated that experimental additives had a positive effect in maintaining intestinal health by modifying microbial content and gene expression [31,66]. Consistent with this, the current study showed that adding a nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis mixture led to an increase in Lactobacillus counts and gene expression of MUC-2, CAT-1, and IL-10, while decreasing E. coli and C. perfringens counts and gene expression of IL-6. The impacts of essential oils and probiotics on pathogenic microorganisms can be attributed to several distinct mechanisms, including altering their adhesion to the epithelium, altering the pH of the intestinal lumen, reducing the production of toxic compounds, preventing biofilm formation [37,44], and inhibiting the growth of pathogenic microbes [54] by interacting with microbial cell membranes, causing cell disruption. The antimicrobial activity of essential oils can also be attributed to their bioactive compounds, which disrupt nucleic acid synthesis and ATPase, altering cell membrane permeability [37] and thus exhibiting antibacterial effects against pathogens.

Identifying changes in gene expression patterns of genes that play a vital role in rabbit health and performance is a critical measure for assessing the impact of heat stress and experimental nutritional supplements on rabbit performance [8,67]. High ambient temperature has a gene-modifying effect, negatively impacting nutrient absorption and stimulating various defense activities to protect various tissue cells [66], including immune-related genes (cytokines). The current study demonstrated the impact of heat stress on the gene expression of several genes, decreased expression of MUC-2, CAT-1, and IL-10 gene, while increased expression of IL-6, indicating induced inflammation, consistent with many previous studies. Additionally, many previous reports have indicated the positive role of feed additives, including essential oils and probiotics, in modulating the expression of genes related to growth, inflammation, and immune response, as well as genes regulating digestion, absorption, and intestinal health and metabolism in chickens and rabbits [22,54]. Consistent with previous reports, the nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis mixture had a significant effect on gene expression, increasing expression of IL-10, CAT-1, and MUC-2 genes, while decreasing expression of IL-6. Similarly, previous reports found that adding essential oils had a modulatory effect on the MUC-2 and IL-10 genes [68]. Moreover, Yosi and Metzler-Zebeli [68], and Abdel-Raheem et al. [69] found increased MUC-2 and IL-10 gene expression in chickens fed a probiotic diet. The influence of essential oil and probiotic supplementation on gene expression in rabbits may be attributed to their antimicrobial activity, which positively alters the intestinal microbiome, promotes intestinal growth and immune function, maintains the integrity of the intestinal barrier, and reduces inflammation, all of which contribute to enhanced intestinal health and growth. Additionally, mucus is the first line of immune defense within the gastrointestinal tract, and enhancing its secretion has a beneficial effect in preventing the invasion of pathogenic microbes and their toxins [70]. Hence, the combination of nano-encapsulated cumin oil with B. subtilis could provide synergistic functions to enhance intestinal integrity by counteracting the inflammatory response and enhancing mucus secretion, providing a promising avenue for enhanced health benefits in rabbits.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that adding a mixture of nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis has a positive effect in reducing the impacts of heat stress in growing rabbits by enhancing oxidative stability and immune response, as well as improving lipid profile and thyroid gland performance. Meanwhile, the mixture enhanced gut health, including reducing inflammation and pathogenic microbes, and up-regulated the expression of the mucin-2 (MUC-2) gene. This mixture also contributed to increased nutrient digestibility and up-regulation of the cationic amino acid transporter-1 (CAT-1) gene expression, which enhanced feed utilization efficiency and carcass weight. Therefore, adding a mixture of nano-encapsulated cumin oil and B. subtilis to the diet of growing rabbits could be beneficial for improving growth performance as an effective anti-stress supplement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.E. (Ahmed M. Elbaz) and A.A.; methodology, A.Y.A., A.S. and A.M.E. (Ahmed M. Elbaz); software, A.S.A. and A.S.; validation, A.M.E. (Ahmed M. Elbaz), H.A., K.M.A. and A.A.; formal analysis, A.Y.A. and A.M.H.; investigation, A.M.E. (Ahmed M. Elbaz) and A.A.; resources, A.S., M.M. and A.S.A.; data curation, A.M.E. (Ahmed M. Elkanawaty) and A.Y.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.E. (Ahmed M. Elbaz); writing—review and editing, A.Y.A., A.M.E. (Ahmed M. Elkanawaty), S.S., A.I.E.S., S.M.A.-R. and A.A.; supervision, M.H.M., M.A.-R., S.M.A.-R., A.M.E. (Ahmed M. Elbaz) and S.A.A.-S.; funding acquisition, M.M. and H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Annual Funding track by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Proposal Number KFU253708]. This research is also supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R460), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal handling procedures complied with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Research Ethics Committee’s guidelines at the Faculty of Agriculture, Ain Shams University and Desert Research Center, Cairo, Egypt, which approved this study under protocol #0021-024-082.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia through the Annual Funding track [Proposal Number KFU253708]. The authors extend also their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R460), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BS | Growing rabbits received a basal diet with Bacillus subtilis |

| BSNO | Growing rabbits received a basal diet with Bacillus subtilis and nano-encapsulated cumin oil |

| BWG | Body weight gain |

| C. perfringens | Clostridium perfringens |

| CAT-1 | Cationic amino acid transporter-1 |

| CON | Growing rabbits received a basal diet |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| FCR | Feed conversion ratio |

| FI | Feed intake |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| IL-10 | Interleukin 10 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| LDL | low-density lipoprotein |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MUC-2 | Mucin 2 |

| NECO | Growing rabbits received a basal diet with nano-encapsulated cumin oil |

| PR | Pulse rate |

| RR | Respiratory rate |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| T3 | Triiodothyronine |

| T4 | Thyroxine |

| THI | Temperature-humidity index |

References

- Liang, Z.L.; Chen, F.; Park, S.; Balasubramanian, B.; Liu, W.C. Impacts of heat stress on rabbit immune function, endocrine, blood biochemical changes, antioxidant capacity and production performance, and the potential mitigation strategies of nutritional intervention. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 906084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladimeji, A.M.; Johnson, T.G.; Metwally, K.; Farghly, M.; Mahrose, K.M. Environmental heat stress in rabbits: Implications and ameliorations. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2022, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Moneim, A.M.E.; Shehata, A.M.; Khidr, R.E.; Paswan, V.K.; Ibrahim, N.S.; El-Ghoul, A.A.; Aldhumri, S.A.; Gabr, S.A.; Mesalam, N.M.; Elbaz, A.M.; et al. Nutritional manipulation to combat heat stress in poultry—A comprehensive review. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 98, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebeid, T.A.; Aljabeili, H.S.; Al-Homidan, I.H.; Volek, Z.; Barakat, H. Ramifications of heat stress on rabbit production and role of nutraceuticals in alleviating its negative impacts: An updated review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbaz, A.M.; Ashmawy, E.S.; Ali, S.A.; Mourad, D.M.; El-Samahy, H.S.; Badri, F.B.; Thabet, H.A. Effectiveness of probiotics and clove essential oils in improving growth performance, immuno-antioxidant status, ileum morphometric, and microbial community structure for heat-stressed broilers. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, M.; Mussard, E.; Barilly, C.; Lencina, C.; Gress, L.; Painteaux, L.; Gabinaud, B.; Cauquil, L.; Aymard, P.; Canlet, C.; et al. Developmental stage, solid food introduction, and suckling cessation differentially influence the comaturation of the gut microbiota and intestinal epithelium in rabbits. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, A.M.; Ashmawy, E.S.; Farahat, M.A.A.; Abdel-Maksoud, A.; Amin, S.A.; Mohamed, Z.S. Dietary Nigella sativa nanoparticles enhance broiler growth performance, antioxidant capacity, immunity, gene expression modulation, and cecal microbiota during high ambient temperatures. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, A.M.; Ashmawy, E.S.; Mourad, D.M.; Amin, S.A.; Khalfallah, E.K.M.; Mohamed, Z.S. Effect of oregano essential oils and probiotics supplementation on growth performance, immunity, antioxidant status, intestinal microbiota, and gene expression in broilers experimentally infected with Eimeria. Livest. Sci. 2025, 291, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, M.; Fathi, M.; El-Raffa, A.; Abd El-latif, G.; Abou-Emera, O.; Abd El-Fatah, M.; Rayan, G. Influence of probiotic supplementation and rabbit line on growth performance, carcass yield, blood biochemistry and immune response under hot weather. Anim. Biosci. 2025, 38, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, A.M.; Ashmawy, E.S.; Salama, A.A.; Abdel-Moneim, A.M.E.; Badri, F.B.; Thabet, H.A. Effects of garlic and lemon essential oils on performance, digestibility, plasma metabolite, and intestinal health in broilers under environmental heat stress. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adli, D.N.; Sjofjan, O.; Sholikin, M.M.; Hidayat, C.; Utama, D.T.; Jayanegara, A.; Natsir, M.H.; Nuningtyas, Y.F.; Pramujo, M.; Puspita, P.S. The effects of lactic acid bacteria and yeast as probiotics on the performance, blood parameters, nutrient digestibility, and carcase quality of rabbits: A meta-analysis. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 22, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Wu, F.; Hao, G.; Qi, Q.; Li, R.; Li, N.; Wei, L.; Chai, T. Bacillus subtilis improves immunity and disease resistance in rabbits. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tong, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhao, T.; Xia, X. Probiotic Bacillus subtilis contributes to the modulation of gut microbiota and blood metabolic profile of hosts. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 272, 109712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puvača, N.; Tufarelli, V.; Giannenas, I. Essential oils in broiler chicken production, immunity and meat quality: Review of Thymus vulgaris, Origanum vulgare, and Rosmarinus officinalis. Agriculture 2022, 12, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koné, A.P.; Desjardins, Y.; Gosselin, A.; Cinq-Mars, D.; Guay, F.; Saucier, L. Plant extracts and essential oil product as feed additives to control rabbit meat microbial quality. Meat Sci. 2019, 150, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, T.L.; Jamikorn, U. Effects of probiotic supplement (Bacillus subtilis and Lactobacillus acidophilus) on feed efficiency, growth performance, and microbial population of weaning rabbits. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 30, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, A.; Davati, N.; Emamifar, A. Effects of Cuminum cyminum L. essential oil and its nanoemulsion on oxidative stability and microbial growth in mayonnaise during storage. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 4781–4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathy, R.R.; Abaza, M.; Mohamed, Z.; Tantawy, A.H.; Abdallah, M.; Khalaf, N.M.; Mohamed, S. Antibacterial effects of nano-emulsified cumin oil on performance and carcass characteristics in weaning rabbits infected by Clostridium perfringens type A. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2025, 14, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Salem, H.M.; Ashry, N.M.; Ghanima, M.M.A.; Shukry, M.; Swelum, A.A.; Taha, A.E.; El-Tahan, A.M.; et al. Essential oils and their nanoemulsions as green alternatives to antibiotics in poultry nutrition: A comprehensive review. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Meneses, A.K.; Plascencia-Jatomea, M.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J.; Fernández-Quiroz, D.; Rodríguez-Félix, F.; Mouriño-Pérez, R.R.; Cortez-Rocha, M.O. Schinus molle L. essential oil-loaded chitosan nanoparticles: Preparation, characterization, antifungal and anti-aflatoxigenic properties. Lwt 2018, 96, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Mu, Q.; Qi, J.; Sa, C. The Chemical Composition of Cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) Analyzed by UPLC-Q-Orbitrap MS and GC-MS. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20, 1934578X251328280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, A.M.; El-Sonousy, N.K.; Arafa, A.S.; Sallam, M.G.; Ateya, A.; Abdelhady, A.Y. Oregano essential oil and Bacillus subtilis role in enhancing broiler’s growth, stress indicators, intestinal integrity, and gene expression under high stocking density. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, N.; Afsharmanesh, M.; Salarmoini, M.; Meimandipour, A.; Hosseini, S.A.; Ebrahimnejad, H. Effects of nanoencapsulated cumin essential oil as an alternative to the antibiotic growth promoter in broiler diets. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2020, 29, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Rabbits, 2nd ed.; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Marai, I.F.M.; Ayyat, M.S.; Abd El-Monem, U.M. Growth performance and reproductive traits at first parity of New Zealand White female rabbits as affected by heat stress and its alleviation under Egyptian conditions. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2001, 33, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shebl, H.M.; Ayoub, M.A.; Kishik, W.H.; Khalil, H.A.; Khalifa, R.M. Effect of thermal stresses on the physiological and productive performance of pregnant doe rabbits. Agric. Res. J. 2008, 8, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, N.; Mandal, L. Carcass and meat quality traits of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) under warm-humid condition of West Bengal, India. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2008, 20, 7. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis. Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 1990. Available online: https://archive.org/details/gov.law.aoac.methods.1.1990 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Abdel-Moneim, A.M.E.; Selim, D.A.; Basuony, H.A.; Sabic, E.M.; Saleh, A.A.; Ebeid, T.A. Effect of dietary supplementation of Bacillus subtilis spores on growth performance, oxidative status, and digestive enzyme activities in Japanese quail birds. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Sabic, E.; Abu-Taleb, A.; Abdel-Moneim, A. Effect of dietary supplementation of full-fat canola seeds on productive performance, blood metabolites and antioxidant status of laying Japanese quails. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2020, 22, eRBCA-2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.A.; Anas, H.; Alduwish, M.A.; Alharbi, N.A.; Alian, H.A.; Youssef, I.M.; Moustafa, M.; Elolimy, A.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Saber, H.S. Influence of probiotic supplementation on growth, health and gut characteristics in growing rabbits. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 24, 1499–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elazab, M.A.; Khalifah, A.M.; Elokil, A.A.; Elkomy, A.E.; Rabie, M.M.; Mansour, A.T.; Morshedy, S.A. Effect of dietary rosemary and ginger essential oils on the growth performance, feed utilization, meat nutritive value, blood biochemicals, and redox status of growing NZW rabbits. Animals 2022, 12, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, E.; Gul, M. Effects of cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) essential oil and chronic heat stress on growth performance, carcass characteristics, serum biochemistry, antioxidant enzyme activity, and intestinal microbiology in broiler chickens. Vet. Res. Commun. 2023, 47, 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimohamadi, K.; Taherpour, K.; Ghasemi, H.; Fatahnia, F. Comparative effects of using black seed (Nigella sativa), cumin seed (Cuminum cyminum), probiotic or prebiotic on growth performance, blood haematology and serum biochemistry of broiler chicks. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2014, 98, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R.F.; Hassan, M.A.; Moustafa, M.; Al-Shehri, M.; Alazragi, R.S.; Khojah, H.; El-Raghi, A.A.; Abdelnour, S.A.; Gad, A.M. The Influence of a nanoemulsion of cardamom essential oil on the growth performance, feed utilization, carcass characteristics, and health status of growing rabbits under a high ambient temperature. Animals 2023, 13, 2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, E.; Gul, M. Effects of essential oils on heat-stressed poultry: A review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 108, 1481–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnini, C.; Saeed, R.; Bamias, G.; Arseneau, K.O.; Pizarro, T.T.; Cominelli, F. Probiotics promote gut health through stimulation of epithelial innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kady, M.F.E.; Hassan, E.R.; Radwan, E.H.; Rabie, N.S.; Rady, M.M. Effect of probiotic on necrotic enteritis in chickens with the presence of immunosuppressive factors. Glob. Vet. 2012, 9, 345–351. Available online: http://www.idosi.org/gv/GV9(3)12/17.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Habibi, R.; Jalilvand, G.; Samadi, S.; Azizpour, A. Effect of different levels of essential oils of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) and cumin (Cuminum cyminum) on growth performance carcass characteristics and immune system in broiler chicks. Iran. J. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2016, 6, 395–400. [Google Scholar]

- Adaszýnska-Skwirzýnska, M.; Szczerbínska, D. The effect of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) essential oil as a drinking water supplement on the production performance, blood biochemical parameters, and ileal microflora in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathi, M.; Abdelsalam, M.; Al-Homidan, I.; Ebeid, T.; El-Zarei, M.; Abou-Emera, O. Effect of probiotic supplementation and genotype on growth performance, carcass traits, hematological parameters and immunity of growing rabbits under hot environmental conditions. Anim. Sci. J. 2017, 88, 1644–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.F.; El-Sayiad, G.A.; Reda, F.M.; Ashour, E.A. Effects of breed, probiotic and their interaction on growth performance, carcass traits and blood profile of growing rabbits. Zagazig J. Agric. Res. 2017, 44, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufarelli, V.; Losacco, C.; Pugliese, G.; Tateo, A.; Schiavitto, M.; Iarussi, F.; Laudadio, V.; Passantino, L. Effects of a multi-strain probiotic on productive traits, antioxidant defence, caecal microbiota and short-chain fatty acid profile, and intestinal histomorphology in rabbits. Anim. Biosci. 2025, 38, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Yu, Y.; Su, Z.; Zhang, K. Effects of essential oils on performance, egg quality, nutrient digestibility and yolk fatty acid profile in laying hens. Anim. Nutr. 2017, 3, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.; Everts, H.; Kappert, H.J.; Frehner, M.; Losa, R.; Beynen, A.C. Effects of dietary essential oil components on growth performance, digestive enzymes and lipid metabolism in female broiler chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2003, 44, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbaz, A.M.; El-Hawy, A.S.; Salem, F.M.; Lotfy, M.F.; Ateya, A.; Alshehry, G.; Alghamdi, Y.S.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Elolimy, A.A.; Abdelhady, A.Y. Dietary incorporation of melittin and clove essential oil enhances performance, egg quality, antioxidant status, gut microbiota, and MUC-2 gene expression in laying hens under heat stress conditions. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 24, 1762–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemipour, H.; Kermanshahi, H.; Golian, A.; Veldkamp, T.J.P.S. Effect of thymol and carvacrol feed supplementation on performance, antioxidant enzyme activities, fatty acid composition, digestive enzyme activities, and immune response in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madkour, M.; Aboelenin, M.M.; Habashy, W.S.; Matter, I.A.; Shourrap, M.; Hemida, M.A.; Elolimy, A.A.; Aboelazab, O. Effects of oregano and/or rosemary extracts on growth performance, digestive enzyme activities, cecal bacteria, tight junction proteins, and antioxidants-related genes in heat-stressed broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorati, R.; Foti, M.C.; Valgimigli, L. Antioxidant activity of essential oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 10835–10847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, N.; Aziza, A.; Orma, O.; Ibrahim, T. Effect of supplementation of broiler diets with essential oils on growth performance, antioxidant status, and general health. Mansoura Vet. Med. J. 2020, 21, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidi, M.; Khosravinia, H.; Masouri, B. Independent and combined effects of Satureja khuzistanica essential oils and dietary acetic acid on fatty acid profile in thigh meat in male broiler chicken. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 2266–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, J.P.; Gotardo, L.R.; Dos Santos, A.M.; Litz, F.H.; Olivieri, O.C.; Alves, R.L.; Moraes, C.A.; de Mattos Nascimento, M.R. Effect of cyclic heat stress on thyroidal hormones, thyroid histology, and performance of two broiler strains. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 64, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Moneim, A.M.E.; Ali, S.A.; Sallam, M.G.; Elbaz, A.M.; Mesalam, N.M.; Mohamed, Z.S.; Abdelhady, A.Y.; Yang, B.; Elsadek, M.F. Effects of cold-pressed wheat germ oil and Bacillus subtilis on growth performance, digestibility, immune status, intestinal microbial enumeration, and gene expression of broilers under heat stress. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, R.E.S.; Ateya, A.; Gadalla, H.; Alharbi, H.M.; Alwutayd, K.M.; Embaby, E.M. Growth Performance, Immuno-Oxidant Status, Intestinal Health, Gene Expression, and Histomorphology of Growing Quails Fed Diets Supplemented with Essential Oils and Probiotics. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Su, X.; Guo, S.; Shi, H.; Guo, C.; Li, J.; Lv, J.; Yu, M.; Huang, M. Effects of compound essential oil and oregano oil on production performance, immunity and antioxidant capacity of meat rabbits. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 22, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Moneim, A.M.E.; Khidr, R.S.; Badran, A.M.; Amin, S.A.; Badri, F.B.; Gad, G.G.; Thabet, H.A.; Elbaz, A.M. Efficacy of supplementing Aspergillus awamori in enhancing growth performance, gut microbiota, digestibility, immunity, and antioxidant activity of heat-stressed broiler chickens fed diets containing olive pulp. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, E.; Gul, M. Effects of dietary supplementation of cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) essential oil on expression of genes related to antioxidant, apoptosis, detoxification, and heat shock mechanism in heat-stressed broiler chickens. Anim. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 2766–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.F.; Bai, K.W.; Su, W.P.; Wang, A.A.; Zhang, L.L.; Huang, K.H.; Wang, T. Curcumin attenuates heat-stress-induced oxidant damage by simultaneous activation of GSH-related antioxidant enzymes and Nrf2-mediated phase II detoxifying enzyme systems in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humam, A.M.; Loh, T.C.; Foo, H.L.; Samsudin, A.A.; Mustapha, N.M.; Zulkifli, I.; Izuddin, W.I. Effects of feeding different postbiotics produced by Lactobacillus plantarum on growth performance, carcass yield, intestinal morphology, gut microbiota composition, immune status, and growth gene expression in broilers under heat stress. Animals 2019, 9, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, A.M.; Ateya, A.; Youssef, S.A.; Arafa, A.S.; Sallam, M.G.; Abd El-Aziz, A.; Al-Rasheed, M.; Babaker, M.A.; Othman, D.O.; Gad, G.G.; et al. Efficacy of in ovo feeding with Lactobacillus acidophilus and oregano essential oil in improving growth performance, immunity, microbial enumeration, and gene expression of ostrich chicks. Livest. Sci. 2025, 298, 105723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Xiao, C.; Tian, B.; Dorthe, S.; Meuter, A.; Song, B.; Song, Z. Dietary probiotic based on a dual-strain Bacillus subtilis improves immunity, intestinal health, and growth performance of broiler chickens. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, K.; Li, C.L.; Wang, J.; Qi, G.H.; Gao, J.; Zhang, H.J.; Wu, S.G. Effects of dietary supplementation with Bacillus subtilis, as an alternative to antibiotics, on growth performance, serum immunity, and intestinal health in broiler chickens. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 786878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Croom, J.; Ali, R.A.; Ballou, A.L.; Smith, C.D.; Ashwell, C.M.; Hassan, H.M.; Chiang, C.C.; Koci, M.D. Direct fed microbial supplementation repartitions host energy to the immune system. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 2639–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnesr, S.; Abdel-Azim, A. The impact of heat stress on the gastrointestinal tract integrity of poultry. Labyrinth: Fayoum J. Sci. Interdiscip. Stud. 2023, 1, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Ncho, C.M.; Choi, Y.H. Regulation of gene expression in chickens by heat stress. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, K.; Tian, G.; Ding, X.; Bai, S.; Zeng, Q. Effects of thymol and carvacrol eutectic on growth performance, serum biochemical parameters, and intestinal health in broiler chickens. Animals 2023, 13, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosi, F.; Metzler-Zebeli, B.U. Dietary probiotics modulate gut barrier and immune-related gene expression and histomorphology in broiler chickens under non-and pathogen-challenged conditions: A meta-analysis. Animals 2023, 13, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Raheem, S.M.; Abd El-Hamid, M.I.; Khamis, T.; Baz, H.A.; Omar, A.E.; Gad, W.M.; El-Azzouny, M.M.; Habaka, M.A.; Mohamed, R.I.; Elkenawy, M.E.; et al. Comprehensive efficacy of nano-formulated mixed probiotics on broiler chickens’ performance and Salmonella typhimurium challenge. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, A.; Kitahara, K.; Terada, H.; Ueno, A.; Ohmori, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Horio, F. Ingestion of paddy rice increases intestinal mucin secretion and goblet cell number and prevents dextran sodium sulfate-induced intestinal barrier defect in chickens. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 3577–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).