Abstract

With the rapid rate at which networking technologies are changing, there is a need to regularly update network activity datasets to accurately reflect the current state of network infrastructure/traffic. The uniqueness of this work was that this was the first network dataset collected using Zeek and labelled using the MITRE ATT&CK framework. In addition to identifying attack traffic, the MITRE ATT&CK framework allows for the detection of adversary behavior leading to an attack. It can also be used to develop user profiles of groups intending to perform attacks. This paper also outlined how both the cyber range and hadoop’s big data platform were used for creating this network traffic data repository. The data was collected using Security Onion in two formats: Zeek and PCAPs. Mission logs, which contained the MITRE ATT&CK data, were used to label the network attack data. The data was transferred daily from the Security Onion virtual machine running on a cyber range to the big-data platform, Hadoop’s distributed file system. This dataset, UWF-ZeekData22, is publicly available at datasets.uwf.edu.

1. Introduction

As the variety of cyberattacks grow by the day, targeting everything from corporations (large and small), municipalities, healthcare institutions, educational institutions, critical infrastructure, etc., it is no longer sufficient to just analyze attacks after they happen. Though analyzing attacks after they happen will provide some insight, attackers are constantly finding new ways to attack different systems and infrastructures. Basically, in addition to network intrusion detection, other aspects such as threat hunting, intelligence hunting, and risk management are equally important for corporations (large and small) as well as other systems and infrastructures. Hence, developing a good cybersecurity dataset is a major challenge in today’s world. In addition to network intrusion detection capabilities, a good network dataset has to be able to provide intelligence and be responsive to address the new threats. Hence our choice of using the MITRE Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge (ATT&CK) framework in the development of this new network dataset, UWF-ZeekData22, available at datasets.uwf.edu [1]. The MITRE ATT&CK framework has a knowledge base that can be expanded to be quickly responsive to newer threats.

This paper describes the creation of a one-of-a-kind modern real (not simulated) network data repository, created using Zeek [2], labeled using the MITRE ATT&CK framework [3]. The MITRE ATT&CK® framework, originally created in 2013 and constantly being upgraded to the present day, is a knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques based on real-world observations. This knowledge base serves as a foundation for the development of threat models used in the private sector as well as government. The present version of the MITRE ATT&CK framework presently contains 14 tactics, and each tactic consists of several techniques and sub-techniques. The basis of the ATT&CK model is the set of techniques and sub-techniques that represent actions that adversaries can perform to accomplish objectives (tactics).

Zeek is an open-source traffic analyzer, optimized for interpreting network traffic and generating logs based on network traffic. Zeek specifically targets high-speed, high-volume network monitoring, and an increasing number of sites, including supercomputing centers, major corporations, government agencies, etc., are now using Zeek to monitor their 10 GE networks. Zeek is best known for its transaction data, and it generates a collection of compact, richly annotated sets of transaction logs that describe the protocols and activities seen on the wire [2]. By default, Zeek writes all this information into well-structured tab-separated or JSON log files suitable for post-processing with external software.

Due to the volume of data being collected, the data collected for this research project, UWF-ZeekData22, generated using Zeek, is being collected in the Big Data Framework, specifically, Apache Hadoop. Hadoop is a highly fault-tolerant distributed file system that is used to efficiently store and process large datasets. Apache hadoop uses an open-source framework.

Hence, to summarize the novelty of this paper:

This dataset, UWF-ZeekData22, was created using the MITRE ATT&CK framework. This implies that this dataset:

- Can be used to detect adversary behavior leading up to an attack;

- Can be used to develop a profile of user or user groups intending to perform attacks;

- Can also be used to identity attack traffic and attacks.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section presents the related works and provides some background on the present state of network datasets. Section 3 presents the architectural framework used for collecting UWF-ZeekData22. Section 4 describes the process of generating and collecting the data. Section 5 explains the data. Section 6 presents the mapping and correlation (labelling) of the data. Section 7 presents a traffic analysis, and, finally, Section 8 presents the conclusion.

2. Background and Related Work

To develop strong and robust automated network risk detection and mitigation solutions, the first necessity is to have a modern network traffic dataset, which is presently lacking. Though several network intrusion datasets have been developed over the past 25 years, researchers are still looking for better datasets that can be used to build robust solutions. Table 1 presents a comparison of many of the major network intrusion datasets built to date, starting with KDDCup99. The datasets were compared based on the following parameters: duration of data collected, whether the data was simulated or real, number of attack families, format of the data collected, the number of networks the data was collected from, number of distinct IP addresses, extraction tools used, number of features, number of files in the data, and the framework. Next, the datasets are briefly discussed.

Table 1.

Comparing major network intrusion detection datasets.

While other network attack datasets have been purposed [4,5,6,7], older datasets such as DARPA’98 and KDDCup 99 [8,9] are still being used in current research. The KDD99Cup dataset has been a very widely studied network intrusion dataset. This simulated dataset was mainly built off DARPA’98 and inherited the problems of DARPA’98. For example, an analysis of the attacks in the DARPA dataset revealed that many did not fit any of the attack categories and were likely caused by simulation artifacts [10]. KDD99Cup has additional problems of its own. The KDD99Cup dataset is un-proportionately distributed and hence is not efficient for machine learners. It is known to have repeating records. To solve the issues of the KDD99Cup dataset, the NSL-KDD was developed. In the NSL-KDD dataset, redundant or duplicate records were removed, and the dataset was more balanced [10]. This dataset has four types of attacks: DoS, probe, user-to-root, and remote-to-local. It has 5,209,458 records.

The DDoS 2016 dataset (not included in Table 1) was developed using the Network Simulator NS2 [11]. This dataset has 27 features and 734,627 records. It includes four types of attacks: HTTP flood, UDP flood, DDoS using SQL injection, and Smurf.

The UNSW-NB15 dataset was developed using the IXIA PerfectStorm tool in a network with 45 IP addresses over 31 h [12]. This dataset, which has 49 features and 175,341 records, and includes both typical activities and injected attack behaviors.

The University of Granada 2016 (UGR16) acquired network data from a teir-three Internet Service Provider (ISP) over four months, and this dataset was labeled using the logs from a honeypot system [13]. This dataset includes three types of malware: annotated botnet, SSH scan, and SPAM attacks.

The CICIDS 2017 dataset, collected by the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity [14], used the CICFlowMeter for the extraction of network data from twenty-five users over five days. This dataset includes Heartbleed, DoS, and DDoS attacks and has 80 features.

The CSE-CIC-IDA 2018 dataset uses synthetic user profiles, which abstractly represent network events and behaviors of 420 computers and 30 servers collected with CICFlowMeter-V3 [15]. This dataset has eighty-four features and includes four types of attacks: Botnet, brute force, denial-of-service, and distributed DoS.

ToN-IoT, published in 2021 by researchers at the University of New South Wales, includes Zeek netflow data, system operation logs from both windows and linux operating systems, and telemetry datasets from a collection of seven IoT and IIoT devices. The dataset has nine attack families, and the authors specifically emphasized the need for a standardization of feature descriptions and cyberattack classes. This dataset is the first that combines netflow, IoT telemetry, and operating system data [16].

Additional comparisons of network attack datasets can be found in [17,18]. These comparisons are based largely on network statistics, types of attacks, whether the data is synthetic or not, and the size of the dataset. Hence, from the literature it is apparent that, to date, there is no modern network labelled dataset using the MITRE ATT&CK framework, as is created in this work.

3. Architectural Framework for Collecting UWF-ZeekData22

3.1. Overall Architectural Framework

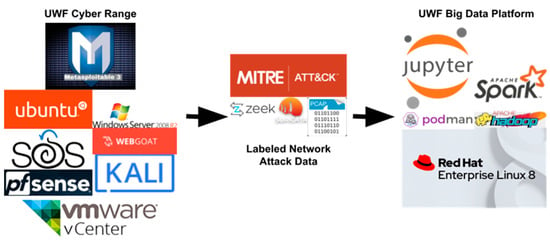

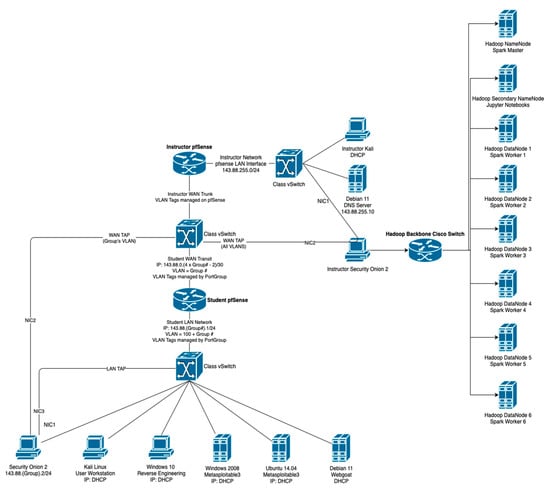

Figure 1 presents the overall architectural framework for data collection. It shows how both the cyber range and big data platform were used for this research. Cybersecurity attacks generated in University of West Florida (UWF)’s cybersecurity classes were collected using Security Onion in two formats: Zeek and PCAPs. Mission logs, which contain the MITRE ATT&CKs, were collected and used to label the network attack data. The data was transferred daily from the Security Onion virtual machine running on the cyber range to the big-data platform, Hadoop’s distributed file system (HDFS).

Figure 1.

UWF cyber range and big-data platform.

3.2. The UWF Cyber Range

The UWF cyber range is an internet HTML5 browser-accessible VMware vCenter that consists of one vCenter server appliance and three ESXi servers. The cyber range allows for the development of a full spectrum of cybersecurity skills, malware analysis, offensive cyber operations, and defensive cyber operations, in the safety of a sandbox environment. The software stack consists of virtualization, router/firewall, penetration testing/cybersecurity, induction detection system/threat hunting, targeting insecure application servers, and targeting insecure platform servers (Windows and Linux). Specifically, it is composed of:

- VMware vCenter;

- Pfsense;

- Kali;

- WebGoat;

- Security Onion 2;

- Ubuntu and Windows Server 2008 R2 Metasploitable 3.

VMware vSphere is VMware’s virtualization platform, which transforms data centers into aggregated computing infrastructures that include CPU, storage, and networking resources [19]. vSphere manages these infrastructures as a unified operating environment and provides tools to administer the data centers that participate in this environment. The range runs VMware vCenter Server Essentials Version 6.7. Figure 1 presents the UWF’s cyber range, and the specifications of UWF’s cyber range are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

UWF cyber range specifications.

3.3. UWF’s Hadoop Cluster

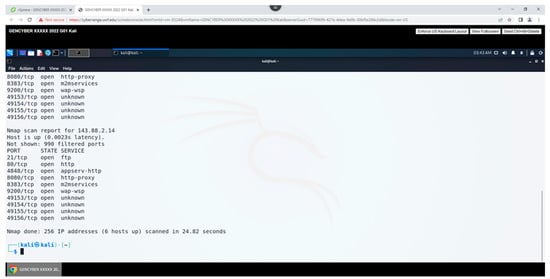

UWF’s big-data platform is a HTML5-accessible JupyterLab via secure shell protocol (SSH) tunneling for security, as shown in Figure 2. The software stack consists of HDFS and the Spark distributed computing system.

Figure 2.

UWF’s browser-accessible cyber range, HTML5.

- RedHat Enterprise Linux;

- Podman;

- Apache HDFS;

- Apache Spark;

- JupyterLab.

Red Hat Enterprise Linux is the world’s leading enterprise Linux platform, which is certified on hundreds of clouds and with thousands of hardware and software vendors [20]. Red Hat Enterprise Linux can be purchased to support specific use cases such as edge computing or SAP workloads, but every subscription includes these core benefits. Podman is a daemonless container engine for developing, managing, and running OCI containers on Linux system’s [21]. Containers can either be run as root or in a rootless mode. Apache HDFS is a distributed file system that provides high-throughput access to application data [22]. Apache Spark is a multi-language engine for executing data engineering, data science, and machine learning on single-node machines or clusters [23]. JupyterLab is the latest web-based interactive development environment for notebooks, code, and data [24]. Its flexible interface allows users to configure and arrange workflows in data science, scientific computing, computational journalism, and machine learning. A modular design allows extensions to expand and enrich functionality.

The hardware stack includes nine servers.

- (×3) 2015 Dell PowerEdge R730 (20 cores, 128 GB RAM, and 4 TB Storage);

- (×6) 2015 Dell PowerEdge R730xd (20 cores, 128 GB RAM, and 48 TB Storage).

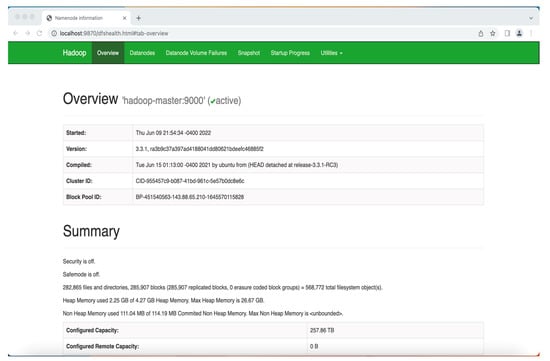

UWF’s Hadoop cluster consists of one Hadoop name node and five Hadoop worker nodes. The Apache Hadoop software library is a framework that allows for the distributed processing of large datasets across clusters of computers using simple programming models [22]. It is designed to scale-up from single servers to thousands of machines, each offering local computation and storage. Rather than relying on hardware to deliver high-availability, the library itself is designed to detect and handle failures at the application layer, thus delivering a highly available service on top of a cluster of computers, each of which may be prone to failures. The cluster runs Apache Hadoop Version 3.3.1-RC3 on Redhat Enterprise Release 8 (Figure 3). The cluster has a storage capacity of 214.88 TB.

Figure 3.

Hadoop cluster user interface.

UWF’s Hadoop and Spark clusters share the same hardware. The clusters:

- Use one Dell PowerEdge R730 with 40 cores, 128 GB Memory, and a minimal amount of storage as the Hadoop name node and Spark master (Table 3);

Table 3. UWF Hadoop/Spark cluster.

Table 3. UWF Hadoop/Spark cluster. - Use five Dell PowerEdge R730xd, while maximizing the storage, as the Hadoop worker nodes and Spark workers;

- The cluster is interconnected using two bonded 10 gbps

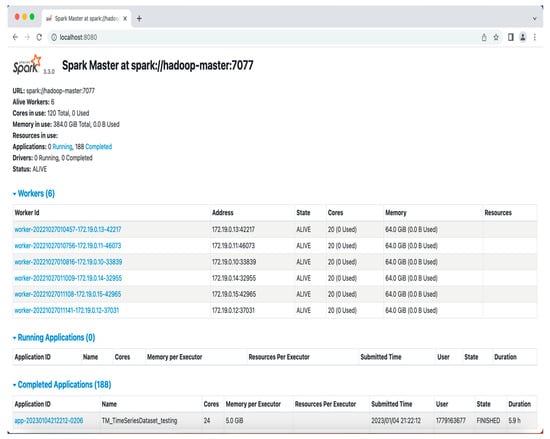

3.4. UWF’s Spark Cluster

UWF’s Spark cluster consists of one Spark master and five Spark workers. Apache Spark is a multi-language engine for executing data engineering, data science, and machine learning on single-node machines or clusters [23]. The cluster runs Apache Spark Version 3.2.1 (Apache Software Foundation, United States) on Redhat Enterprise Release 8 (Figure 4). The cluster has a storage capacity of 460 GHz/200 cores and 640 GB of memory.

Figure 4.

UWF Spark cluster user interface.

4. Generating and Collecting the Data

These data were collected from a cyber wargaming course, designed and offered at the University of West Florida, Pensacola, Florida, USA. The theme of the course was that every organization, whether government or private, needs IT personnel to defend its networks against attack. The most effective way to provide this experience was to recreate scenarios that students will see in the real world. Exercises were provided that performed specific roles in attacking and defending IT infrastructures. The cyber wargaming courses used UWF’s cyber range, as presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Virtualized network architecture: UWF’s cyber wargaming lab setup.

This VMware vCenter allowed access to virtualized networks from the Internet via a hypertext markup language version 5 (HTML5)-compatible web browser. Network principles were practiced with the aid of pfsense, which acted as a router with a built-in firewall. Offensive cyber operations (OCO) (e.g., red team or penetration testing) were practiced in the safety of the closed virtualized networks provided by the UWF cyber range using Kali Linux, implementing the full Lockheed Martin kill chain (e.g., the use of EternalBlue) [25]. Kali Linux is an open-source penetration-testing, security-research, computer-forensics, and reverse-engineering distribution based on Debian Linux [26]. Defensive cyber operations (DCO) and network operations (NetOps) (e.g., blue team, hunt, network monitoring) were conducted using Security Onion with both built-in and custom IDS rules via Snort and Suricata, and analytics using Elastic Stack dashboards and visualization were used to detect events. Security Onion is a free and open-source threat-hunting, network-security-monitoring, and log-management platform including best-of-breed open-source tools (e.g., Zeek, Wazuh, and Elastic Stack) [27]. A target-rich and diverse environment was provided by both Windows and Linux variants of Metasploitable. Metasploitable is a virtual machine with numerous built-in security vulnerabilities (e.g., security vulnerabilities found in GlassFish, Apache Structs, Tomcat Jenkins, IIS FTP, IIS HTTP, psexec, SSH, WinRM, Chinese caidao, ManageEngine, ElasticSearch, Apache Axis2, WebDAV, SNMP, MySQL, JMX, Wordpress, SMB, Remote Desktop, PHP MyAdmin), which are intended to be exploited using Metasploit, such as the Metasploit Framework found in Kali Linux [18]. These VMs formed the bases of our virtualized networks, but many other VMs and services have found their way into the network for research and educational purposes (e.g., Splunk, CentOS, Windows XP, Windows 7, Windows 10, lightweight directory access protocol (LDAP), active directory (AD)). Pfsense, Kali Linux, Security Onion, and Metasploitable were arranged in such a manner that each group had their own network (Figure 5).

The cyber war-gaming stages of the cyber operation topics (i.e., reconnaissance, gaining access, hiding presence, establishing persistence, execution, and assessment) were assessed through labs conducted within UWF’s cyber range (e.g., conduct a reconnaissance offense cyber operation on your target(s)). The attacks were recorded using the Security Onion VM, producing Zeek logs and PCAP files. Mission logs that contained the MITRE ATT&CK data were collected and used to label the network attack data. The data was transferred daily from the Security Onion virtual machine running on the cyber range to the big-data platform, HDFS.

To date, 208.62 GB of Zeek logs and PCAPs have been collected. A total of 16 weeks of network traffic data have been collected using 81 subnets.

5. The Data

This dataset contains several files that include nominal and numeric as well as object variables. To completely understand this dataset, it is necessary to have a good understanding of Zeek as well as the MITRE ATT&CK framework, both of which are fairly complex structures.

5.1. Zeek

Zeek, in many ways, exceeds the capabilities of other network-monitoring tools and is also highly customizable. Zeek produces an extensive set of logs that describe the network activity. These logs not only document every connection but also document application-layer transcripts such as DNS requests with replies. Table 4 shows the Zeek log files collected in this experimentation process, the total count of records in each file, and a description of each of the files. The field names of each of the files are given in Appendix A. For further information on the files, for example, the field types, null values, and other information, please refer to [1].

Table 4.

Zeek Files in UWF-ZeekData22 dataset.

5.2. MITRE ATT&CK Framework

ATT&CK is a behavioral model consisting of tactics, techniques, and sub-techniques. It documents known adversary behavior. The first ATT&CK model, created in September 2013, was refined and released in May 2015 with ninety-six techniques organized under nine tactics. Since then, the ATT&CK model has experienced tremendous growth based on contributions from the cybersecurity community and has had several updated versions. The April 2021 version, used for the creation of UWF-ZeekData22, has 14 tactics as well as 191 techniques and 358 sub-techniques, for a grand total of 576 techniques. In order to keep the techniques at a manageable level as well as address some of the new abstractions of the techniques, sub-techniques were added to the knowledge base in 2020.

The MITRE ATT&CK framework reflects various phases on an adversary’s attack lifecycle. Tactics represent an adversary’s goals for an attack. Tactics are the ways that adversaries perform an operation, such as persist, discover information, move laterally, or execute files.

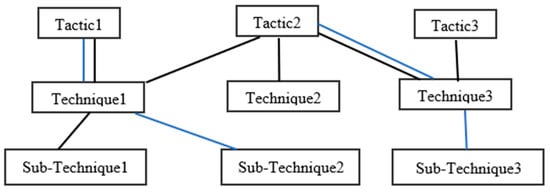

Tactics have techniques, and techniques have sub-techniques. A technique or sub-technique can be used to perform one or multiple tactics, and there can be multiple techniques for each tactic. Likewise, there are multiple ways to perform a technique, so there can be multiple sub-techniques for each technique. However, all techniques may not have sub-techniques.

Techniques or sub-techniques show what an adversary intends to do. For example, for the discovery tactic, the technique or sub-technique may show what type of information an adversary is after. Techniques and sub-techniques, which are actions for a tactic, are implemented with procedures and used for achieving tactical goals. Sub-techniques further break down behaviors described by techniques [28].

The quick response offered by the MITRE ATT&CK framework after identifying new adversarial behavior is created by adding a new technique or sub-technique and making the existing technique or sub-technique inclusive of the new adversarial behavior. Some techniques were originally very broad, having the capacity to add sub-techniques, hence limiting the need to create new techniques every time. However, each sub-technique will only have a relationship with a single parent technique, and the sub-technique is not required to fall under all tactics that a technique is in. This is shown in Figure 6 with the blue lines. Sub-technique2 falls under Technique1 and Tactic1, but not Tactic2, although Technique1 falls under both Tactic1 and Tactic2. Similarly, Sub-technique3 falls under Technique3 and Tactic2, though Technique3 falls under both Tactic2 and Tactic3. This presents an interesting problem for the data structure and how the data is stored, which is discussed briefly in the latter part of this paper.

Figure 6.

Relationship between MITRE ATT&CK tactics, techniques, and sub-techniques.

Hence, since the ATT&CK model is just as much about the mindset of the user as the process of using it (with a combination of various techniques and sub-techniques), it can be used to develop profiles of adversary groups, which can be used to improve defensive measures [29].

Tactics Available in UWF-ZeekData22

All 14 tactics presently available in the MITRE ATT&CK framework are now available in this dataset, UWF-ZeekData22. Table 5 presents the tactics found in UWF-ZeekData22. Not all tactics are disruptive to information systems. For example, some tactics such as initial access, discovery, and credential access are mainly focused on breaching the confidentiality of information and can be used to gain information and obtain more access within an environment, with the eventual goal of obtaining information through collection and exfiltration.

Table 5.

Tactics in UWF-ZeekData22.

Table 6 presents the distribution of malicious traffic in the UWF-ZeekData22 dataset, labelled as per the MITRE ATT&CK framework. There were 10 attack types (or tactics), but reconnaissance made up 99.97% of the attacks in this dataset.

Table 6.

Distribution of malicious traffic in UWF-ZeekData22.

6. Mapping and Labeling the Data

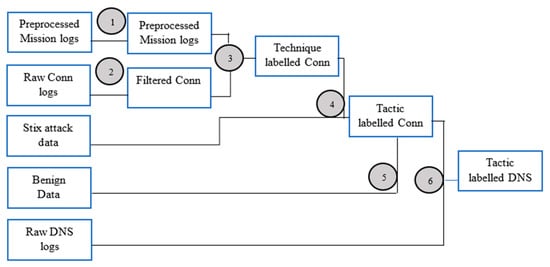

One of the major challenges faced in creating this dataset was mapping and labelling the attacks or Zeek logs as per the MITRE ATT&CK framework. This was conducted with the help of the mission logs and is detailed in the next couple sections. We present the pseudo-algorithms used to label two data files: the DNS data file and a similar sub-set of the DNS mappings that were used to label the Conn data files.

6.1. Labeling the DNS Data File

Figure 7 presents a flowchart of the process used to map and label the DNS data file. The numbers in the figure correspond to the numbered list below.

Figure 7.

Process to label the DNS data file.

- Preprocess mission logs

- Convert time stamps to unix epoch time;

- Create arrays for port, IP, and attack features;

- With strings such as “101, 102, 103” in a port column, create a new column port_array that contains [101, 102, 103];

- Manually set port and IP address values where mission log input is noisy or unclear (for example, for responses such as “unknown high port” or “all ports”). Responses were interpreted as broadly as possible; for instance, the response “unknown” was replaced with all port numbers in the registered range 1–1023;

- Preprocess Conn data file (this is shown in Section 6.2);

- Convert time stamps to unix epoch time;

- Rename attributes with “.” in the attribute name to avoid Spark syntax issues;

- Join mission logs and preprocessed Conn file on the following:

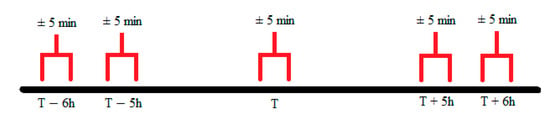

- Time (see Figure 8 for specifics on slop factor)

Figure 8. Timeline slop factor graphic (not to scale).

Figure 8. Timeline slop factor graphic (not to scale).- Conn datetime ≥ mission log start time (±slop factor)

- AND Conn datetime ≤ mission log end time (±slop factor)

- AND IP

- Conn src ip == mission log src ip

- AND Conn dest ip == mission log dest ip

- AND Port

- Conn src port == mission log src port

- AND Conn dest port == mission log dest port

- Join labeled Conn and STIX data;

- Flatten array columns (IP and MITRE attacks). Unflattened and flattened data are shown in Table 7 and Table 8 respectively;

Table 7. Unflattened dataframe with array data.

Table 7. Unflattened dataframe with array data. Table 8. Flattened dataframe.

Table 8. Flattened dataframe. - Map MITRE technique (already in Conn) to MITRE tactic (with mappings from STIX data);

- Some techniques map to multiple tactics. This is handled by flattening the array;

- Mix benign data;

- Label with mitre_attack == none, label_tactic == none;

- Join labeled Conn with raw DNS to produce labeled DNS;

- FROM Conn SELECT uid, mitre_attack, label_tactic

- FROM dns SELECT all

- Join on conn.uid == dns.uid

The slop factor (Figure 8) was used to take-into-account any human error that might have occurred in the recording of the mission logs. Since the manual timings entered in the mission logs might be plus or minus a few minutes, to adjust for this, a time interval of plus or minus a few minutes was used to record the actual time of the attack.

Since there were multiple techniques for each tactic and multiple sub-techniques for each technique, the STIX data contained many array type attributes. We chose to flatten these; Table 7 shows a generic base case with array data, and Table 8 shows the method we used to flatten our data applied to the generic case from Table 7.

6.2. Labeling the Conn Data File

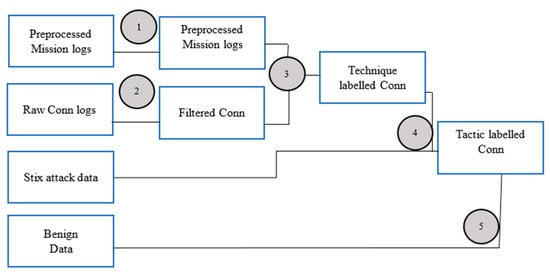

Figure 9 presents a flowchart of the process to map and label the Conn data file. The numbers in the figure correspond to the numbered list in Section 6.1.

Figure 9.

Process to label the Conn data file.

7. Traffic Analysis

Table 9 shows the distribution of the malicious vs. non-malicious traffic in this new dataset, UWF-ZeekData22. The non-malicious traffic was collected at a time where there was no possibility of an attack.

Table 9.

Malicious vs. non-malicious traffic.

A total of 60 different tactics and techniques are available in UWF-ZeekData22. More information about the specific tactics and techniques (both flattened and unflattened) is available in [1]. Table 10 presents an unflattened count of each of the different tactics and techniques in UWF-ZeekData22.

Table 10.

MITRE ATT&CK tactics/techniques in UWF-ZeekData22.

Traffic Analysis of Cumulative Flows

A summary traffic analysis is presented for the cumulative flows during the period of data collection while generating the UWF-ZeekData22 dataset. Table 11 presents the dataset statistics, which shows the flow numbers, total of source bytes, destination bytes, number of source packets, number of destination packets, protocol types, number of normal and abnormal records, and the number of unique source/destination IP addresses for the data collection period.

Table 11.

Summary traffic analysis of UWF-ZeekData22.

8. Conclusions

In conclusion, UWF-ZeekData22 can be considered a modern NIDS benchmark dataset and will be useful to the NIDS research community. Since it is based on the MITRE ATT&CK framework, in addition to the network traffic analysis that is usually carried out using machine learning, other aspects of adversarial behavior can also be studied using this dataset, which is available at datasets.uwf.edu [1].

9. Future Works

This dataset will be used in the future for the classification of attacks using classification algorithms such as Random Forest, Decision Tree, SVM, and other machine learning algorithms. Feature selection will also be conducted using this dataset.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.B., D.M., S.C.B. and T.G.; methodology, D.M., S.S.B., R.P. and T.M.; software, R.P. and T.M.; formal analysis, S.S.B., D.M., T.G., R.P. and T.M.; investigation, D.M.; data curation, R.P. and T.M.; writing—original draft, S.S.B., D.M., S.D. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S.B., D.M., T.G., S.C.B., S.D. and S.S.; visualization, T.M. and S.S.; supervision, S.S.B. and D.M.; project administration, S.S.B., D.M. and S.C.B.; funding acquisition, S.S.B., D.M. and S.C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by 2021 NCAE-C-002: Cyber Research Innovation Grant Program, grant number: H98230-21-1-0170.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All discussed data available online at datasets.uwf.edu.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Zeek files and attributes.

Table A1.

Zeek files and attributes.

| Name | Attributes |

|---|---|

| mission_logs | id, sis_id, datetime_submitted, attempt, group_number, mitre_attck_technique, bcol_1-011, src_ip, src_port, dest_ip_arrays, dest_ip, dest_portdatetime_submitted, dt_start, datetime_start, dt_end, datetime_end, num_correct, num_incorrect, score |

| Broker | ts, ty, ev, peer.address, peer.bound_port, message, peer |

| capture_loss | ts, ts_delta, peer, gaps, acks, percent_lost |

| Cluster | |

| conn-summary | |

| Conn | ts, uid, id.orig_h, id.orig_p, id.resp_h, id.resp_p, proto, service, duration, orig_bytes, resp_bytes, conn_state, local_orig, local_resp, missed_bytes, history, orig_pkts, orig_ip_bytes, resp_pkts, resp_ip_bytes, community_id, id, tunnel_parents |

| dhcp | ts, uids, client_addr, server_addr, mac, host_name, domain, assigned_addr, lease_time, msg_types, duration, requested_addr, client_port, server_port, client_fqdn, client_message, server_message, client_chaddr |

| dns | ts, uid, id.orig_h, id.orig_p, id.resp_h, id.resp_p, proto, trans_id, query, qclass, qclass_name, qtype, qtype_name, rcode, rcode_name, AA, TC, RD, RA, Z, rejected, rtt, answers, TTLs, lass_name, qtype, qtype_name, rcode, rcode_name, AA, TC, RD, RA, Z, rejected, rtt, answers, TTLs, id, total_answers, total_replies, saw_query, saw_reply |

| loaded_scripts | |

| Notice | ts, uid, id.orig_h, id.orig_p, id.resp_h, id.resp_p, fuid, proto, note, msg, sub, src, dst, p, peer_descr, actions, suppress_for, id, conn, iconn, f, file_mime_type, file_desc, n, peer_name, email_dest, email_body_sections, email_delay_tokens, identifier |

| packet_filter | |

| Reporter | |

| Stats | ts, peer, mem, pkts_proc, bytes_recv, events_proc, events_queued, active_tcp_conns, active_udp_conns, active_icmp_conns, tcp_conns, udp_conns, icmp_conns, timers, active_timers, files, active_files, dns_requests, active_dns_requests, reassem_tcp_size, reassem_file_size, reassem_frag_size, reassem_unknown_size, pkts_dropped, pkts_link, pkt_lag |

| Stderr | |

| Stdout | |

| Weird | ts, uid, id.orig_h, id.orig_p, id.resp_h, id.resp_p, name, notice, peer, addl, source, id, conn, identifier |

References

- Available online: https://datasets.uwf.edu/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- About Zeek—Book of Zeek. Available online: https://docs.zeek.org/en/master/about.html (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- MITRE ATT&CK. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/ (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Krundyshev, V.M. Preparing datasets for training in a neural network system of intrusion detection in industrial systems. Autom. Control Comput. Sci. 2019, 53, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almomani, I.; Al-Kasasbeh, B.; AL-Akhras, M. WSN-DS: A Dataset for Intrusion Detection Systems in Wireless Sensor Networks. J. Sens. 2016, 2016, 4731953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zago, M.; Gil Pérez, M.; Martínez Pérez, G. UMUDGA: A dataset for profiling algorithmically generated domain names in botnet detection. Data Brief 2020, 30, 105400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.; Naser Mahmood, A.; Hu, J. A survey of network anomaly detection techniques. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2016, 60, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DARPA Intrusion Detection Evaluation Dataset. MIT Lincoln Lab. Available online: https://www.ll.mit.edu/r-d/datasets/1998-darpa-intrusion-detection-evaluation-dataset (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- KDD Cup 1999. Available online: http://kdd.ics.uci.edu/databases/kddcup99/kddcup99.html (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Tavallaee, M.; Bagheri, E.; Lu, W.; Ghorbani, A. A detailed analysis of the KDD CUP 99 data set. In Proceedings of the Second IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence for Security and Defence Applications, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 8–10 July 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkasassbeh, M.; Al-Naymat, G.; Hassanat, A.; Almseidin, M. Detecting Distributed Denial of Service Attacks Using Data Mining Techniques. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2016, 7, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, N.; Slay, J. UNSW-NB15: A Comprehensive Data Set for Network Intrusion Detection Systems. In Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS); IEEE: Canberra, Australia, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciá-Fernández, G.; Camacho, J.; Magán-Carrión, R.; García-Teodoro, P.; Therón, R. UGR’16: A New Dataset for the Evaluation of Cyclostationarity-Based Network IDSs. Comput. Secur. 2018, 73, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafaldin, I.; Habibi Lashkari, A.; Ghorbani, A.A. A Detailed Analysis of the CICIDS2017 Data Set. In ICISSP; Revised Selected Papers; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNB CSE-CIC-IDS2018 on AWS. Available online: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/ids-2018.html (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Booij, T.M.; Chiscop, I.; Meeuwissen, E.; Moustafa, N.; den Hartog, F.T. ToN_IoT: The Role of Heterogeneity and the Need for Standardization of Features and Attack Types in IoT Network Intrusion Data Sets. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, A.; Harshini, E.; Selvakumar, S. SSENet-2011: A network intrusion detection system dataset and its comparison with KDD CUP 99 dataset. In Proceedings of the 2011 Second Asian Himalayas International Conference on Internet (AH-ICI), Kathmundu, Nepal, 4–6 November 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasevicius, R.; Venckauskas, A.; Grigaliunas, S.; Toldinas, J.; Morkevicius, N.; Aleliunas, T.; Smuikys, P. LITNET-2020: An Annotated Real-World Network Flow Dataset for Network Intrusion Detection. Electronics 2020, 9, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VMware vSphere Documentation. Available online: https://docs.vmware.com/en/VMware-vSphere/index.html (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Red Hat Enterprise Linux Operating System. Available online: https://www.redhat.com/en/technologies/linux-platforms/enterprise-linux (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Podman. Available online: https://podman.io/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Apache Hadoop. Available online: https://hadoop.apache.org/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Apache Spark—Unified engine for large-scale data analytics. Available online: https://spark.apache.org/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Project Jupyter | Home. Available online: https://jupyter.org/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Hutchins, E.M.; Cloppert, M.J.; Amin, R.M. Amin. Intelligence-driven computer network defense informed by analysis of adversary campaigns and intrusion kill chains. Lead. Issues Inf. Warf. Secur. Res. 2011, 1, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Kali Linux | Penetration Testing and Ethical Hacking Linux Distribution. Available online: https://www.kali.org/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Security Onion Solutions. Available online: https://securityonionsolutions.com/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Strom, B.E.; Applebaum, A.; Miller, D.P.; Nickels, K.C.; Pennington, A.G.; Thomas, C.B. Mitre att&ck: Design and Philosophy. Technical Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.mitre.org/news-insights/publication/mitre-attck-design-and-philosophy (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- MITRE ATT&CK: Design and Philosophy—Mitre Corporation. Available online: https://pdf4pro.com/view/mitre-att-amp-ck-design-and-philosophy-mitre-corporation-7083ef.html (accessed on 19 September 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).