Abstract

In this paper, we study the information lost when a real-valued statistic is used to reduce or summarize sample data from a discrete random variable with a one-dimensional parameter. We compare the probability that a random sample gives a particular data set to the probability of the statistic’s value for this data set. We focus on sufficient statistics for the parameter of interest and develop a general formula independent of the parameter for the Shannon information lost when a data sample is reduced to such a summary statistic. We also develop a measure of entropy for this lost information that depends only on the real-valued statistic but neither the parameter nor the data. Our approach would also work for non-sufficient statistics, but the lost information and associated entropy would involve the parameter. The method is applied to three well-known discrete distributions to illustrate its implementation.

1. Introduction

We consider the data sample from a random sample for a discrete random variable with sample space and one-dimensional parameter A statistic is a function of the random sample for any fixed but arbitrary value of a parameter associated with the underlying Thus a statistic is a random variable itself. Here we consider only real-valued statistics that reduce the data sample to a number that might be used to summarize to characteriz , However, data reduction is an irreversible process [1] and always involves some information loss. For instance, if is the sample mean the original measurements cannot be reconstructed from and some information about is lost. Nonetheless, such data reduction is frequently used to make inferences.

More explicitly, our motivation for considering such situations is that is usually communicated in practice as a summary for the data but without the actual data. The question then naturally arises: how much information is lost to someone about a data sample when only the value of is available for , but not the data itself? To answer this question, we develop a theoretical framework for determining how much information is lost about a given data set by knowing only the value of but neither itself nor the parameter . Our information-theoretic approach to data reduction generalizes the observation in [2] that a binomial random variable loses all the information about the order of successes in the associated sequence of Bernoulli trials. In other words, for a series of n Bernoulli trials one cannot recreate the order of successes by only knowing the number that occurred.

For any real-valued statistic and the given sample data we decompose the total information about available in into the sum of (a) the information available in the reduced data and (b) the information lost in the process of data reduction. When is a sufficient statistic for this lost information is independent of . Moreover, by taking the expected value of this lost information over all possible data sets, we define an associated entropy measure that depends on but neither nor . Our approach also works for non-sufficient statistics, but the lost information and associated entropy would then involve . Thus must be estimated before computing these quantities.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we present the necessary definitions, notation, and preliminary results. In Section 3, we decompose the total information available about in and give various expressions for the Shannon information lost by reducing to In Section 4, we develop an entropy measure associated with this lost information. In Section 5, we present examples of our results for some standard discrete distributions and several sufficient statistics for Conclusions are offered in Section 6.

2. Preliminaries

Standard definitions, notation, and results to be used in our development are now presented for completeness and accessibility. In addition, some new definitions and results are established for subsequent use. Definition 1, Result 1, Definition 2, and Definition 3 can be found in [3,4,5] and elsewhere. The notion of a sufficient statistic is first defined.

Definition 1 (Sufficient Statistic [3]).

A statisticis a sufficient statistic (SS) for the parameterif the probability

is independent of.

Note that instead of is used in (1) since this probability is independent of In addition, observe that (1) is not a joint conditional probability distribution for since its condition changes with . This observation is significant in Section 4. The fact that (1) does not involve can be used to prove the Fisher Factorization Theorem (FFT) below, which is the usual method for determining if a statistic is an SS for . In the FFT, we use the notation to denote the joint probability mass function (pmf) of evaluated at the variable for a fixed value of .

Result 1 (FFT [3]).

The real-valued statisticis sufficient forif and only if there exist functionsandsuch that for any sample dataand for all values ofthe joint pmfofcan be factored as

for real-valued, nonnegative functionson andonThe functiondoes not depend onwhiledoes depend onbut only through

We focus on a sufficient statistic for in Section 3, where we need the notion of a partition [5] defined next.

Definition 2 (Partition [3]).

Letbe the denumerable sample space of the discrete random variableso thatis the denumerable sample space of the random sample. For any statistic, letbe the denumerable setfor which, which is the range ofThenpartitions the sample spaceinto the mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive partition sets.

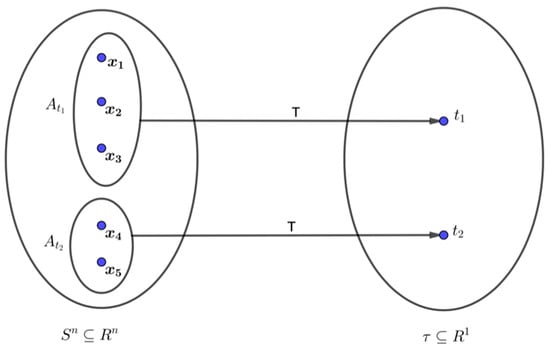

Figure 1 illustrates Definition 2.

Figure 1.

Partition Sets.

We also use the well-known likelihood function.

Definition 3 (Likelihood Function [3,4,5]).

Letbe sample data from a random samplefrom a discrete random variablewith sample spaceand real-valued parameterand letdenote the joint pmf of the random sample. For any sample data, the likelihood function ofis defined as

The likelihood function in (3) is a function of the variable for given data . However, the joint pmf as a function of for fixed is frequently called the likelihood function as well. In this case, we also write the joint pmf as We distinguish the two cases since is not a statistic but is one that incorporates all available information about . Moreover, is an SS for [4] and uniquely determines an associated SS called the likelihood kernel to be used in subsequent examples.

We next define a new concept called the likelihood kernel. As a function of for fixed , it is shown below to be a sufficient statistic for and is used in Section 5 to facilitate the computation of lost information associated with other sufficient statistics T. As a function of for fixed , a possibility not considered here, the likelihood kernel may be useful in applying the likelihood principle [3,4] to make inferences about without resorting to the notion of equivalence classes. It would be the “simplest” factor of that can be used in a likelihood ratio comparing two values of

Definition 4 (Likelihood kernel).

Letbe the sample space of. For fixed but arbitrarysuppose thatcan be factored as

whereandhave the following properties.

- (a)

- Every nonnumerical factor ofcontains

- (b)

- does not contain

- (c)

- Forbothand

- (d)

- is not divisible by any positive number except 1.

Thenis defined as the likelihood kernel ofandas the residue of

Theorem 1.

The likelihood kernelhas the following properties.

- (i)

- exists uniquely.

- (ii)

- is an SS for.

- (iii)

- For anyandthe likelihood ratioequals

Proof.

To prove (i), for fixed we first show that the likelihood kernel of Definition 4 exists by construction. Since the formula for must explicitly contain the parameter cannot appear only in the range of . Hence as a function of can be factored into , satisfying (a) and (b) of Definition 4, where and the numerical factor of is either or Then since and Thus (c) is satisfied. Finally, the only positive integer that evenly divides or is so (d) holds. It follows that the and its associated in Definition 4 are well defined and exist.

We next show that as constructed above is unique. Let with residue and with both satisfy Definition 4. Thus for does not contain , while every nonnumerical factor of does contain It follows that and must be identical or else be a positive multiple of one another. Assume that for some If is divisible by a positive number other than to contradict (d). Thus is unique.

To prove (ii), we show that this unique is an SS for For let and in (2). Then, = Thus is an SS by the FFT of Result 1. Finally, (iii) follows from Definition 4 and the fact that the joint pmf for □

We next discuss the notion of information to be used. Actually, probability itself is a measure of information in the sense that it captures the surprise level of an event. An observer obtains more information, i.e., surprise, if an unlikely event occurs than if a likely one does. Instead of probability, however, we use the additive measure known as Shannon information [6,7], defined as follows.

Definition 5 (Shannon Information [6,7]).

Letbe sample data for the random samplefrom the discrete random variablewith a one-dimensional parameterand letbe the joint pmf ofatThe Shannon information obtained from the sample datais defined as

where the units of is bits if the base of the logarithm is 2, which is to be used here.

Other definitions for information have been proposed. For example, Vigo [8,9] has defined a measure of representational information. Further details on different types of information can be found in [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. For Shannon information, we use its expected value over .

Definition 6 (Entropy [17,18,19,20]).

Under the conditions of Definition 5, the Shannon entropyis defined as the expected value ofi.e.,

The general properties of Shannon entropy are given in [17,18,19,20], for example. Since entropy is the expected information over all possible random samples, it can be argued that entropy is a better measure of the available information aboutthan would the Shannon information for a single data setwhich might not be typical [18]. We next give a method to obtain the information loss aboutthat occurs when a data setis reduced toIn our approach, we focus on a sufficient statisticso there will be noin (5) for the lost information below.

3. Information Decomposition under Data Reduction by a Real-Valued Statistic

We now develop a procedure to determine how much information about contained in a data set is lost when the data is reduced to by the sufficient statistic Consider the joint conditional probability

which is identified with the probabilistic information lost about the event by the data reduction of to The notation refers to the fact that the discrete probability (7), in general, involves the parameter We next express (7) using the definition of conditional probability to obtain the basis of our development. Result 2 is given in ([3], p. 273) and proven below to illustrate the reasoning.

Result 2 [3].

Letbe sample data for a random samplefrom a discrete random variablewith sample spaceand real-valued parameterand letbe any real-valued statistic. Then

Proof.

Using the definition of conditional probability, rewrite (7) as

However, whenever so (8) follows. □

Observe that if is an SS for the left side of (8) is independent of by the FFT and hence so is the right. Taking the negative logarithm of (8) and rearranging terms gives

From (8), note that since so Similarly, These facts suggest that the left side of (10) is the total Shannon information in bits about contained in the sample data . On the right side of (10), the term is considered the information about contained in the reduced data summary and the term is identified as the information about that has been lost as the result of the data reduction by

In particular, this lost information represents a combinatorial loss in the sense that multiple ’s may give the same value , as depicted in Figure 1 above. In other words, the lost information is a measure of the knowledge unavailable about the data sample when only the reduced data summary is known but not itself. For a sufficient statistic for , this lost information is independent of . It is a characteristic of for the given data sample

In terms of Figure 1, (10) may be described as follows. On the left of the figure is the sample space over which probabilities on are computed. On the right is the range of over which the probability of are computed. reduces the data sample into where multiple ’s may give the same . In Figure 1, the distinct data samples and are all reduced into the same value However, knowing that for some data sample does not provide sufficient information to know unequivocally, for example, that Information is lost in the reduction. One can also say that the total information obtained from the left side of Figure 1 is reduced to obtained from the right. The reduction in information from the left to the right side is precisely the lost information of (10). For fixed it is lost due to the ambiguity as to which data sample on the left actually gave There is no such ambiguity when is one-to-one.

The general decomposition of information in (10) is next summarized in Definition 7, where does not need to be sufficient for

Definition 7 ().

Letbe sample data for a random samplefrom a discrete random variablewith sample spaceand real-valued parameterFor any real-valued statisticthe Shannon information aboutobtained from the sample datacan be decomposed as

where

and

Definition 7generalizes the information decomposition of [2] for a data sampleof size n from a Bernoulli random variablein [2] is the probability 0.5 of success on a single Bernoulli trial, andIt should be noted that the notationin [2], which refers to compressed information, corresponds toin Equation (13). We use the term “data reduction” as described in [3] as opposed to “data compression” to prevent misinterpretation. In computer science, data compression refers to encoding information using fewer bits than the original representation and is often lossless.

Both Result 2 and Definition 7 are valid for any real-valued statistic for The notation indicates that is a function of the sample data for a fixed but arbitrary parameter value Similarly, both and are functions of for fixed and However, in this paper we focus on sufficient statistics, which provide a simpler expression for that does not involve For a sufficient statistic for we use the notation for the lost information, though and still require The next result is an application of the FFT of Result 1.

Theorem 2 (Lost Information for an SS).

Letbe sample data for a random samplefrom a discrete random variablewith sample spaceand real-valued parameterLetbe an SS forletbe the joint pmf ofand writeas in Result 1. Then for all

whereis defined in Definition 2 for

Proof.

Let Then since is a realization of Because is an SS, we write (7) without . It now suffices to establish that

from which (15) immediately follows. Rewrite (8) as

so from (17) and (2), then

However, in (18), so

Since and hence , this term can be canceled on the right side of (19) to yield (16). Taking the of (16) completes the proof. □

Now consider Theorem 2 when each is a singleton in (16), i.e., when is a one-to-one function. In this extreme case, since in the denominator of the right side of (16). Thus from which for all in . Thus, the special case of a one-to-one T justifies the identification of the lost information as . In other words, for all data samples if whenever then is not diminished by the reduction of the singleton to the number .

More generally, it is also true that when is one-to-one but not sufficient for In this case, write However, since is one-to-one, then , and again .

Now consider the other extreme case where is constant on Thus However, so and on In this case, because the event gives no information about

We also note that could be used as a metric to compare sufficient statistics for a given data sample . For example, could be regarded as better than for if However, this comparison would be limited to the given . In Section 4, we propose but do not explore a metric based on entropy independent of a particular data sample. We next show that (16) can be simplified when is the likelihood function.

Corollary 1 (Information Loss for Likelihood Function).

Under the assumptions of Theorem 2, if then

where is the cardinality of the partition set for

Proof.

For in (2), let be the identity function and Then substituting into (16) gives the denominator to yield (20). □

We next state a reproductive property of a statistic that is a one-to-one function of a sufficient statistic for

Theorem 3.

If there is a one-to-one function between a sufficient statisticforand an arbitrary real-valued statisticonthen the following hold.

- (i)

- is also an SS.

- (ii)

- andpartition the sample space into the same partition sets.

- (iii)

Proof.

To prove (i), let be a real-valued one-to-one function of such that

Since is an SS, by Equation (2) there are real-valued functions on and on for which

By substituting from (21) in (22), we get

which can be rewritten as

Since in (24) satisfies the condition of Result 1 for , is an SS.

To prove (ii), we use Definition 2. Let partition the sample space into the mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive sets . By Equation (21) we can also write as

Since is a one-to-one function, it has an inverse . Letting we apply to the right side of (25) and get

However, and the cardinalities satisfy so the right side of (26) is and

Finally, to get (iii) we use Theorem 2 to calculate information lost over two statistics and Since is the same in (22) and (24) and since Equation (27) holds, we sum over the same sets in the denominator of Equation (16) for both and to give

and complete the proof. □

We next compare the information loss of the sufficient statistic to other sufficient statistics. For the sufficient statistic a lemma is needed.

Lemma 1.

Letbe any data sample for a random samplefrom the discrete random variablewith real-valued parameter. Thenis a function ofand

Proof.

From ([3], p. 280), is a function of if and only if whenever For all data samples and we prove that if then Thus suppose that By Definition 4, we can decompose and into and respectively. Note that Otherwise, in contradiction to being sample data with a nonzero probability of occurring. Now write

Suppose that so that in (29). From Definition 4, every nonnumerical factor of and contains Moreover, neither nor is divisible by any positive number except the number 1. Hence, since does not contain the nonnumerical factors of and must cancel in (29) and the remaining numerical factors could not be identical. Thus at least one of these factors would be divisible by a positive number other than 1 in contradiction to Definition 4. It now follows that so is some function of Finally, since this function is surjective from onto its image . □

Lemma 2.

Under the conditions of Lemma 1, the sufficient statisticsandsatisfy

Proof.

Let and suppose that Then so it follows from Lemma 1 that and thus Hence and so

Taking the negative log of both sides of the inequality in (31) and using (13) gives (30). □

Theorem 4.

Letbe sample data for a random samplefrom a discrete random variablewith the real-valued parameterThen for all

Proof.

Let Note that in (12) does not depend on the arbitrary sufficient statistic of (11). Hence

Then (32) follows immediately from (30) and (33). □

As a consequence of Theorem 3, Theorem 4 has an immediate corollary.

Corollary 2.

Under the conditions of Theorem 4, letbe a sufficient statistic forfor which there is a one-to-one function betweenand. Then for all

The question remains open as to whether (34) holds for all sufficient statistics for . Regardless, the proofs of Lemma 2 and Theorem 4 illustrate the fact that the relation between the lost information for two statistics and is determined by the relation between their partition sets and For example, if for every there exists a for which , then the partition of by the of is said to be coarser than the partition by the of In that case, because each has more with than there are with In other words, is at least as ambiguous as in determining the data sample giving the value of the respective statistics.

4. Entropic Loss for an SS

For a sufficient statistic for , we now propose an entropy measure to characterize by the expected lost information incurred by the reduction of to This expectation is taken over all possible data sets This nonstandard entropy measure is called entropic loss, and it depends on neither a particular data set nor the value of Before defining this measure, we need to determine the appropriate pmf to use in taking an expectation. The following results are used.

Result 3.

Under the assumptions of Theorem 2, for any data sample letand consider the partition set Then

Proof.

Summing (16) over yields

to give (35). □

Result 4.

Under the assumptions of Theorem 2, the sum

Proof.

We perform the sum on the left of (37) by first summing over for fixed and then summing over each to give

The inner series on the right side of (38) sums to one by Result 3. Hence, the outer sum yields for for which □

From (37), it follows that the left side of (37) is not a probability distribution on unless Moreover, is not a conditional probability distribution even if since the condition varies with However, we use Result 4 to normalize and obtain the appropriate pmf for calculating the expectation of .

Definition 8 (Entropic Loss).

Under the assumptions of Theorem 2, the entropic loss resulting from the data reduction byis defined as

which from (15) and (16) can be rewritten as

Observe that (39) and (40) are independent of both and Indeed, for a given underlying random variable and sample size n, is a function only of Thus, could be used as a metric to compare sufficient statistics independent of the data sample. In particular, could be regarded as better than if i.e., if the expected information loss associated with is less than that for Moreover, for a given underlying random variable and sample size n, Definition 8 could be extended to non-sufficient statistics. In that case, the entropic loss would be a function of both and For a fixed a non-sufficient statistic could again be considered as better than a non-sufficient if < for a given statistic the numerical value could be considered as a better numerical point estimate for than the value if < Similarly, could be minimized over to give a best numerical point estimate for based on the entropic loss criterion. However, we do not pursue these possibilities here. We next compute for the sufficient statistic

Theorem 5 (Entropic Loss for Likelihood Function).

Under the assumptions of Theorem 2, the entropic loss resulting from the data reduction by

is

Proof.

From (20), write

We decompose the sum over x ∈ Sn in (42) to consecutive sums over and then to get

Equation (41) now follows from (43). □

Result 5.

Suppose there is a one-to-one function between two sufficient statisticsandfor. Then

Proof.

For all from Theorem 3, so

from which

Thus from (45) and (46),

Now summing (47) over yields

However, from Theorem 3, Thus dividing the left side of (48) by and the right side by yields (44). □

5. Examples and Computational Issues

In this section, we present examples involving the discrete Poisson, binomial, and geometric distributions [21]. For each distribution, three sufficient statistics for a parameter are analyzed. For each such , does not involve . However, calculating can still present computational issues, some of which are discussed below. Our examples are simple in order to focus on the definitions and results of Section 3 and Section 4.

Example 1 (Poisson Distribution).

Consider the random samplewith the data samplefrom a Poisson random variable. We consider three sufficient statistics for the parameterThese sufficient statistics arethe likelihood kernelfor fixed but arbitraryand the likelihood function. We useas a surrogate forNeitherorinvolvesand can thus be used either to characterizeor to estimateMoreover, there is an obvious one-to-one function relatingandso Theorems 3 and 5 establish thatandrespectively. We analyzebecause it is also Poisson, whereasis not Poisson sinceis notnecessarily a nonnegative integer. In contrast tobothandcontainand can only be used to characterizeFor each of these three sufficient statistics, we develop an expression forand describe how to obtain a numerical value. We then illustrate previous results with a realistic Poisson data sample. We present further computational results in Table 1.

Table 1.

Poisson Example.

Case 1: Let is a sufficient statistic for from Result 1 since can be factored in (2) into the functions and Next recall that the statistic has a Poisson distribution with parameter [21]. Thus, and so (8) becomes

where the multinomial coefficient It follows from (49) and (10) that

which is also , as noted above.

For a data sample the evaluation of in (50) involves computing factorials [22]. For realistic data, the principal limitation to calculating them by direct multiplication is their magnitude. See [23] for a discussion. However, (50) can be approximated using either the well-known Stirling formula or the more accurate Ramanujan approximation [24]. The online multinomial coefficient calculator [25] can evaluate multinomial coefficients for when all as well as are less than approximately 50 if any is removed from Such deletions do not affect the calculation since .

As a numerical example, consider a data sample of size from a Poisson random variable with , where

Then, and the calculator at [25] gives 10123 in (49) and (50). Moreover, 518.915. Hence, from (50), bits. This value corresponds to 13.708 bytes at 8 bits per byte or to 0.013 kilobytes (KB) at 1024 bytes per KB. It follows from previous discussion in this example that the Shannon information lost by using the sample mean as a surrogate for itself is KB, which seems surprisingly small. Perhaps the small loss results partially from the fact that

Case 2: Let for fixed but arbitrary For a data sample , write

from which

and in (4). Note that for all fixed there is an obvious one-to-one function between and (53). Hence, from Case 1, KB from Theorem 3 for all For from (53) and is constant with respect to any data sample Thus, and It follows that provides no information about

Case 3: Let for fixed but arbitrary We attempt to obtain for a data sample by determining and using (20). From (52), note that for all fixed if and only if

Thus, for any fixed satisfying if both and However, for some it is possible that when neither nor For example, let and Then, 5, and However, (54) is satisfied.

This complication suggests that an efficient implicit enumeration of the satisfying (54) would be required to obtain for calculating from (20). Using such an algorithm, a conventional computer could possibly compute for the numerical data and value of in Case 1, since there is now a 250 petabyte, 200 petaflop conventional computer [26]. Substantially larger problems, if not already tractable, will likely be so in the foreseeable future on quantum computers. Recently, the milestone of quantum supremacy was achieved where the various possible combinations of a certain randomly generated output were obtained in 110 s, whereas this task would have taken the above conventional supercomputer 10,000 years [27]. Regardless, for the data of Case 1, we have the upper bound KB from (32).

Finally, we present some simple computational results to illustrate the relationships among with regard to the Poisson distribution. Table 1 below summarizes the results for sample data with In particular, a complete enumeration of in (20) gives .

Example 2 (Binomial Distribution).

Consider a random samplefrom a binomial random variablewithparametersandwhereis the probability of success on any of theBernoulli trials associated with theLetbe fixed, so the only parameter isMoreover, the sample space of the underlying random variable is now finite.

Case 1:. Again, is an SS for From [21], has a binomial distribution with parameter for fixed Hence,

and

From (1), dividing (56) by (55) gives

By taking the of (57), the lost information is given as

Case 2: In this case, we use (16) as in Example 1. Write

from which and in (4). To factor the right side of (60) as in (2), let be the identity function and . Hence,

and (60) gives

where

From (62), for any fixed satisfying it can easily be shown that if and only if Thus, in general, for a given and fixed determining in Case 2 would require an enumeration of the satisfying (62) to compute (61). We perform such an enumeration below for a simple example.

Case 3: For a data sample , we now have

with being the identity function and in (2). For fixed satisfying from (63) we obtain that if and only if

As in Case 3 of Example 1, developing an algorithm to use (64) and determine for calculating from (20) is beyond the scope of this paper.

As a simple example, consider the experiment of flipping a possibly biased coin twice (). The total number of heads follows a binomial distribution with the parameter , which is the probability of getting a head on any flip. By doing this experiment three times, we generate the random variables with possible values 0, 1, 2. Table 2 shows all the possibilities and the lost information for the statistics. The small size of this example allows the computation of in Cases 2 and 3 via total enumeration.

Table 2.

Binomial Example.

Now, using (40), we give in Table 3 the entropic losses of Example 2 for Note that is the same for the sum and the likelihood kernel which are related by a one-to-one function. Hence, Result 5 is corroborated. In addition, observe that is smallest for the likelihood function .

Table 3.

Entropic loss over different statistics for a binomial distribution.

Example 3 (Geometric Distribution).

Consider a random samplewith sample datafrom a geometric random variablewhere the parameteris the probability of success on any of the series of independent Bernoulli trials for whichis the trial number on which the first success is obtained. It readily follows from [5] that

Case 1:. For fixed has a negative binomial distribution with parameter [21]. Hence,

Thus is an SS for since it satisfies (2) with and . Moreover, substitution of (65) and (66) into (8) gives

Then from (14) and (67) we obtain that

Case 2:. From (66), for all and

Thus, for 0 there is an obvious one-to-one function between and in (69). Thus, from Theorem 3, as given in (68).

Case 3:. Since from (69), then

from (68). However, there is an alternate derivation of (70). For 0 it follows from (69) that then if and only if

But for fixed positive integers we have from [28] that the number of solutions to (71) in positive integers is

Thus, (70) follows for from (72) and (20), so from Theorem 3.

As a numerical illustration, let the random variable denote the number of flips of a possibly biased coin until a head is obtained. Then, has a geometric distribution, where the parameter is now the probability of getting a head on any flip. Suppose this experiment is performed three times yielding the sample data shown in Table 4. is then calculated for each of the sufficient statistics for of Example 3. Observe that the individual statistics depend on while the lost information does not. Moreover, for all data samples, as established above.

Table 4.

Geometric Example.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, the Shannon information obtained for a random sample taken from a discrete random variable with a single parameter was decomposed into two components: (i) the reduced information associated with the value of a real-valued statistic evaluated at the data sample , and (ii) the information lost by using this value as a surrogate for Information is lost because multiple data sets can give the same value of the statistic. In data analysis, the data uniquely determines the value of a statistic, but typically the value of the statistic does not uniquely determine the data yielding it. The lost information thus measures the knowledge unavailable about the data sample when only the reduced data summary is known, but not itself. To eliminate the effect of , we focused on sufficient statistics for such as the sample mean. We then answered the question: how much Shannon information is lost to someone about a data sample when only the value of is available but not the data itself? Our answer is independent of the parameter and does not require that be known. Our method generalizes the approach of [2] for analyzing the information contained in a sequence of Bernoulli trials.

More generally, we developed a metric associated with the value used to summarize, represent, or characterize a given data set. Our approach and results are significant because such statistics are often communicated without the original data. One could argue that should be communicated along with in a manner similar to providing the margin of error associated with the results of a poll. A small would signify that is more informative than if were large.

In addition, we defined the entropic loss associated with a sufficient statistic under consideration as the expected lost information over all possible samples, to give a value dependent only on . We noted but did not explore the possibility that entropic loss could be used as a metric to compare different sufficient statistics. Moreover, if sufficient statistics were not required, entropic loss could provide metrics on either or if the other of these variables is fixed. Finally, numerical examples of our results were presented and some computational issues noted.

Author Contributions

M.M. suggested the topic after reading [2]. She shared the development of the theory and examples of this paper, as well as wrote early drafts. H.C. formulated the general decomposition here. He shared the development of the theory and examples of this paper, as well as edited the final draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Landauer, R. Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1961, 5, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, S.E.; Vieland, V.J. Information loss in binomial data due to data compression. Entropy 2017, 19, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casella, G.; Berger, R.L. Statistical Inference, 2nd ed.; Cengage Learning: Delhi, India, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pawitan, Y. All Likelihood: Statistical Modeling and Inference Using Likelihood, 1st ed.; The Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi, V.K.; Saleh, A.K.E. An Introduction to Probability and Statistics, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication, 1st ed.; The University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell. Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigo, R. Representational information: A new general notion and measure of information. Inf. Sci. 2011, 181, 4847–4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigo, R. Complexity over uncertainty in generalized representational information theory (GRIT): A structure-sensitive general theory of information. Information 2013, 4, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klir, G.J. Uncertainty and Information: Foundations of Generalized Information Theory, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, K. Logic and Information, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Luce, R.D. Whatever happened to information theory in psychology? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2003, 7, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L. The Philosophy of Information, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, W.R. The Processing of Information and Structure, 1st ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Spellerberg, I.F.; Fedor, P.J. A tribute to Claude-Shannon (1916–2001) and a plea for more rigorous use of species richness, species diversity and the “Shannon-Wiener” index. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, O.; Sabato, S.; Tishby, N. Learning and generalization with the information bottleneck. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2010, 411, 2696–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiszár, I. Axiomatic characterizations of information measures. Entropy 2008, 10, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, J.N.; Kesavan, H.K. Entropy Optimization Principles and Their Applications, 1st ed.; Water Science and Technology Library, Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Cover, T.M.; Thomas, J.A. Elements of Information Theory, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ibekwe-SanJuan, F.; Dousa, T. Theories of Information, Communication and Knowledge: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 1st ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.L. Probability and Statistics for Computer Science, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Beeler, R.A. How to Count: An Introduction to Combinatorics and Its Applications, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan, S.; Balakrishnan, R. Foundations of Discrete Mathematics with Algorithms and Programming, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mortici, C. Ramanujan formula for the generalized Stirling approximation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2010, 19, 2579–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multinomial Coefficient Calculator. Available online: https://mathcracker.com/multinomial-coefficient-calculator.php (accessed on 27 July 2019).

- Wan, L.; Mehta, K.V.; Klasky, S.A.; Wolf, M.; Wang, H.Y.; Wang, W.H.; Li, J.C.; Lin, Z. Data management challenges of exascale scientific simulations: A case study with the Gyrokinetic Toroidal Code and ADIOS. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computational Methods, ICCM’19, Singapore, 9–13 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arute, F.; Arya, K.; Martinis, J.M. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 2019, 574, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudvand, R.; Hassani, H.; Farzaneh, A.; Howell, G. The exact number of nonnegative integer solutions for a linear Diophantine inequality. IAENG Int. J. Appl. Math. 2010, 40, 5. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).