Abstract

A gap still exists in published data on variation of morphological and ecological traits for common bird species over a large area. To diminish this knowledge gap, we report here average values of 99 bird species from three sites in Germany from the Biodiversity Exploratories on 24 ecological and functional traits. We present our own data on morphological and ecological traits of 28 common bird species and provide additional measurements for further species from published studies. This is a unique data set from live birds, which has not been published and is available neither from museum nor from any other collection in the presented coverage.

Dataset

available as the supplementary file.

Dataset license

CC-BY

1. Background

Variation in the structure of ecological communities through space and time is a fundamental property of biodiversity (e.g., [1,2,3]). Mostly, taxonomic measures of diversity are used for detection of patterns in structural variation, e.g., species richness. However, many times, species are more or less similar, for example in their functional characteristics [1,2], showing the imperative character of studies including functional diversity and therefore functional traits. Understanding spatial and temporal patterns of functional diversity and their determinants is important because different functional trait distributions may imply the operation of different assembly processes (e.g., [4]). Previous studies of spatial and temporal variation in functional diversity have used a limited number of functional group classes and a discontinuous measure of diversity (e.g., [5,6]), but largely lack continuous measures of functional diversity and functional traits.

While functional trait research has led to greater understanding of the impacts of biodiversity in ecosystems [7], so far functional trait approaches have not been widely applied with continuous functional/ecological traits for lack of data. Even in bird diversity studies, and European bird studies in particular, with relatively good baseline datasets of functional traits available [8,9,10], continuous measures of functional traits remain limited. However, widely applicable indicators of biodiversity are needed to monitor the responses of ecosystems to global change and design effective conservation schemes [11]. Among the potential indicators of biodiversity, those based on the functional traits of species and communities are probably the best suited [7,11], because they can be generalized to similar habitats and can be assessed by relatively rapid field assessment across eco-regions [11]. Nevertheless, there is still a gap in published data on variation of morphological traits or ecological traits for common bird species over a large area. To improve this knowledge gap, we report here average values of 99 bird species from three sites in Germany from the Biodiversity Exploratories [12] on 24 ecological and functional traits in total. We amend and complete our own data sets by data from already published studies [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. We present (1) our own data on morphological and ecological traits of 28 common bird species and 2158 individuals at three sites in Germany and (2) provide further measurements from other publications available for in total 99 bird species. This is a unique data set, which has not been published or the data made available, neither from museum nor from any other collection in the presented coverage.

2. Data Description

This data set contains data on ecological and morphological traits of birds across three major sites in Germany for 99 bird species. The data covers 2014 and 2015 breeding season in the three areas. The baseline data are amend by the addition of morphological traits compiled through a set of available sources [26,27,28,29,30,31]. For each bird captured, we measured several relevant ecological (four own plus six others) and morphological traits (six own plus eight others).

3. Data

The data are separated into two parts; a table with own data (Table 1) and data compiled from other sources (Table 2).

Table 1.

Data sets of ecological and morphological traits of 28 common bird species in Germany (own data, metadata see Table 3). Gray-shaded areas are what we consider ecological traits, all others are morphological traits. n/a indicates that data was not available from other source or we could not measure this trait on the birds.

Table 2.

Compiled data for 99 common bird species in Germany (sources and metadata see Table 3). Gray-shaded areas are what we consider ecological traits, all others are morphological traits. n/a indicates that data are not available or published.

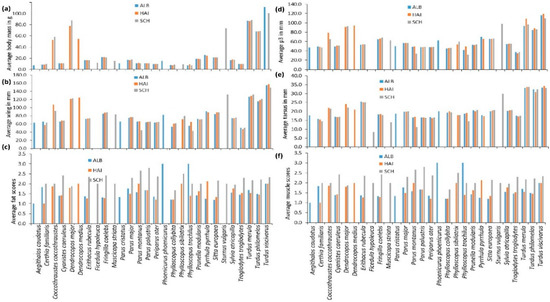

All traits varied considerably between species (Table 1; Figure 1). Within species and between the three sites, 64% of all tests were not significant. The one-third of cases with a significant difference were equally divided among ecological (28) and morphological traits (24) (Appendix A, Table A1).

Figure 1.

Selected traits of the most common bird species in the three Biodiversity-Exploratories in 2014 and 2015; ALB: Schwäbische ALB in the southwest, HAI Hainich-Dün in the center, and SCH Schorfheide-Chorin in the northeast of Germany. (a) Average body mass in grams; (b) average wing length in mm from tip to bow, flattened; (c) average fat scores (following [28,32]); (d) average length of primary three (counted from outside) in mm; (e) average tarsus length (back of the intertarsal joint to the bend of the toe at the metatarsal joint [28] in mm); (f) average muscle scores (following [28,32]).

However, regarding the interspecies differences in traits between the different habitat categories, 88% of the tests were not significant. Here too, the cases with a significant difference were approximately equally divided among ecological (7) and morphological traits (11) (Appendix A, Table A2). A high number of significant interspecies trait differences exist for Erithacus rubecula, Fringilla coelebs, Parus major, Sitta europaea, Sylvia atricapilla, Turdus merula, and T. philomelos (Appendix A, Table A2).

4. Metadata

This section describes the descriptive metadata variables in the data set. In some of the data dimensions, additional information is added in order to provide a full assessment of the data. For each data dimension, we give the variable name, a short verbal description, the unit measured (if applicable) and the source (own and/or a citation if amended by other resource).

5. Methods

The study was part of the large-scale and long-term biodiversity research project ‘Biodiversity Exploratories’ (www.biodiversity-exploratories.de). The three regions differ in climate, geology, and topography but each is characterized by a gradient of forest management types typical for large parts of temperate Europe [12]. In each region, forest plots are selected to cover the whole range of forest management types, whilst minimizing confounding factors such as spatial position [12]. In this study, we sampled a subset of 70 plots (Schwäbische Alb: 28, Hainich-Dün: 21, Schorfheide-Chorin: 21) from which data for all taxa (see below) were available. The three sites in Germany are:

- (1)

- The Schwäbische Alb is located in southwest Germany (centroid about 48.41 North, 9.41 East).

- (2)

- The Hainich-Dün area is located roughly in the center of Germany in-between Schwäbische Alb and Schorfheide-Chorin (centroid about 51.15 North, 10.38 East).

- (3)

- The Schorfheide-Chorin in northeast Germany (centroid about 52.98 North, 13.76 East).

The distance from the northeast to the center exploratory is about 320 km and from the center to the southwest 270 km as the crow flies.

At each exploratory we captured birds at the forest plots (EP), as defined in [12]. All EPs in which we captured birds can be separated into four habitat categories, which represent most of the forest types of the Biodiversity Exploratories in general: natural beech (Fagus sylvatica; i.e., stands with ≥70% of the canopy layer represented by beech trees with diameter at breast height ≥7 cm and at least unmanaged for 60 years), used beech stands (same as natural beech stands but with regular conventional beech forestry management), mixed-deciduous (≤70%), and coniferous stands that either included Norway spruce (Picea abies; ≥70% of spruce) in the Alb and Hainich-Dün, or Scots pine (Pinus sylvatica) in the Schorfheide-Chorin [12]. All plots are 100 m × 100 m with at least an additional 30 m buffer of the same forest structure. The minimum distance between our EP centroids was 300 m. We captured each plot for in total three days in 2014 and two days in 2015, however with a time gap of at least 10 days between each capture day.

6. Capturing of Birds

We captured birds from April to June 2014 and 2015 in all three Exploratories at the same time frame. For capturing, we used (per Exploratories) eight mist nets of 9 m × 2.5 m (size of mesh: 16 mm, nylon). We opened nets 30 min after local sunrise to hit the activity peak of birds and left nets open for five consecutive hours. For improved capture success we placed two playback stations (two per exploratory) close to the mist nets, playing territorial songs of our nine focal species (these are nine species we focus on for other studies: Cyanistes caeruleus, Erithacus rubecula, Fringilla coelebs, Parus major, Periparus ater, Sylvia atricapilla, Troglodytes troglodytes, Turdus merula, Turdus philomelos; [13]). We determined species, sex, and age wherever possible [28]. We screened each bird individual for ecto-parasites (ticks, lice, feather mites) at the head and the under wing, including the areas of primaries/secondaries covered by the under wing coverts. We scored the flight muscle and fat deposits on the abdomen and the furcular in classes following [32].

7. Handling Birds and Permits

Capturing, handling, and blood drawing were performed in compliance with laws and regulations of the European Union, plus German federal and state legislation. All permits were granted by the Regierungspräsidium Tübingen, Referat Tierschutz (TVG-Nr. FR1/14, 35/9185.81-3) for the Schwäbische Alb, by Thüringer Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz, Dezernat 22, Allgemeines Veterinärwesen, Tierseuchenbekämpfung, Tierschutz (TVG-Nr. 15-002/14, 2684-04-15-002/14) for the Hainich-Dün, and by the Landesamt für Umwelt, Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz, Potsdam (TVG-Nr. Para-Aves 2347-3-2014) for the Schorfheide-Chorin. All land owners and land users approved access to the sites.

8. Measuring Birds

All captured birds were measured by three observers (one observer in each site during the field season) in the field to reduce measurements errors through observer bias. In addition, all observers performed a calibration workshop prior to the field season and the discrepancies of measured features was ≤0.05 mm between the observers.

We measured the bill length from tip to proximal end of the operculum, the bill width at the proximal end of the operculum and the bill height at the proximal end of the operculum with a digital caliper to the nearest of 0.01 mm. We determined length of tarsus to the nearest 0.1 mm, and primary feather three (counted from the outside) and wing (tip to carpal joint, flattened) to the nearest of 0.5 mm. To determine the degree of morphological asymmetry, we measured all bilateral traits on both sides of each individual for most individuals, but report only measurements of the left body side (tarsus, for holding position of bird while measured) or right (all other measurements) to reduce bias of different measurement types. For all measurements, the same observer took all measurements from the same individual, resetting the caliper before measuring the next trait. Tarsus length was measured with a digital caliper from the notch at the back of the intertarsal joint to the bend of the toe at the metatarsal joint [28].

We estimated muscle and fat scores (mean scores) in categories as a very rough measure for body condition, following Svensson [28] and Eck et al. [32] respectively.

9. Statistical Analysis

First, we tested the normality of the trait data per given bird species using R [34] and the Shapiro-Wilk test. For 65% of tests that included trait data with more than three observations, the trait data followed a non-normal distribution. Second, to test for differences between Exploratory or between habitat categories, we performed either a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed trait data or a one-way ANOVA for normally distributed trait data (Appendix Table A1 and Table A2).

10. Data Amendments

In addition to our own measured data, we amended and summarized for 99 bird species measurements from other sources that have not yet been presented for the birds, or amended our own data. Our first source for ecological and morphological traits was [28], then we amended the information from [26,27]. Tarsus for Prunella modularis was added from [33] and tarsus of Regulus regulus was added from [31]. We ensured that the specific data from other sources (Table 2) are from the geographically shortest distance towards at least one of the three sites.

11. Bird Species Included

We provide data for Accipiter gentilis, Acrocephalus palustris, Acrocephalus scirpaceus, Aegithalos caudatus, Alauda arvensis, Anser anser, Anthus pratensis, Anthus trivialis, Apus apus, Ardea cinerea, Buteo buteo, Carduelis cannabina, Carduelis carduelis, Carduelis chloris, Carduelis spinus, Certhia brachydactyla, Certhia familiaris, Ciconia ciconia, Coccothraustes coccothraustes, Columba oenas, Columba palumbus, Corvus corax, Corvus corone cornix, Corvus corone corone, Corvus monedula, Coturnix coturnix, Cuculus canorus, Cyanistes caeruleus, Delichon urbica, Dendrocopos major, Dendrocopos medius, Dendrocopos minor, Dryocopus martius, Emberiza calandra, Emberiza citrinella, Erithacus rubecula, Falco tinnunculus, Ficedula hypoleuca, Ficedula parva, Fringilla coelebs, Fringilla montifringilla, Gallinago gallinago, Garrulus glandarius, Grus grus, Hippolais icterina, Hirundo rustica, Jynx torquilla, Lanius collurio, Locustella naevia, Loxia curvirostra, Lullula arborea, Luscinia megarhynchos, Milvus migrans, Milvus milvus, Motacilla alba, Motacilla flava, Muscicapa striata, Oenanthe oenanthe, Oriolus oriolus, Parus cristatus, Parus major, Parus montanus, Parus palustris, Passer domesticus, Passer montanus, Periparus ater, Pernis apivorus, Phasianus colchicus, Phoenicurus ochruros, Phoenicurus phoenicurus, Phylloscopus bonelli, Phylloscopus collybita, Phylloscopus sibilatrix, Phylloscopus trochilus, Pica pica, Picus canus, Picus viridis, Prunella modularis, Pyrrhula pyrrhula, Regulus ignicapillus, Regulus regulus, Saxicola rubetra, Saxicola rubicola, Scolopax rusticola, Sitta europaea, Streptopelia turtur, Strix aluco, Sturnus vulgaris, Sylvia atricapilla, Sylvia borin, Sylvia communis, Sylvia curucca, Sylvia nisoria, Troglodytes troglodytes, Turdus iliacus, Turdus merula, Turdus philomelos, Turdus pilaris, and Turdus viscivorus. Most of the bird species have very low captures and therefore these bird species need to be treated with caution in statistical analysis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the three local management teams of the Biodiversity Exploratories for their incredible support in the field. We thank F. Fischer, W.W. Weisser, K. E. Linsenmair, and F. Buscot for their role in setting up the Biodiversity Exploratories. The work has been funded by the DFG (www.dfg.de) Priority Program 1374 ‘Biodiversity-Exploratories’ (Re1733/6-1). We thank Bruntje Lüdtke, Isa Moser, Julia Kienle, Birke Springer, Marita Salzmann, Manuel Wojta, and Clara Leutgeb for field work and other support in the field. All permits were granted by the Regierungspräsidium Tübingen, Referat Tierschutz (TVG-Nr. FR1/14, 35/9185.81-3) for the Schwäbische Alb, by Thüringer Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz, Dezernat 22, Allgemeines Veterinärwesen, Tierseuchenbekämpfung, Tierschutz (TVG-Nr. 15-002/14, 2684-04-15-002/14) for the Hainich-Dün, and by the Landesamt für Umwelt, Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz, Potsdam (TVG-Nr. Para-Aves, 2347-3-2014) for the Schorfheide-Chorin. The funding organizations or permit organizations had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

SCR conceived and designed the study, provided data and wrote and finalized the paper. WvH provided data and the statistical analysis and co-wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A.

Table A1.

Test results for analyzing differences in variation of traits per species in-between the three Biodiversity Exploratories for the set of ecological and morphological traits of 28 common bird species in Germany based on own data. Gray-shaded and bold indicates p-values < 0.05. Underlined p-values indicate ANOVA, otherwise a Kruskal-Wallis test has been performed. n/a indicates no data available for that trait or too low N.

Table A1.

Test results for analyzing differences in variation of traits per species in-between the three Biodiversity Exploratories for the set of ecological and morphological traits of 28 common bird species in Germany based on own data. Gray-shaded and bold indicates p-values < 0.05. Underlined p-values indicate ANOVA, otherwise a Kruskal-Wallis test has been performed. n/a indicates no data available for that trait or too low N.

| Species | Fat Score | Muscle Score | Body Mass | Bill Height | Bill Length | Tarsus | Wing | p3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aegithalos caudatus | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Certhia familiaris | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.49 | 0.73 | 0.28 | 0.47 |

| Coccothraustes coccothraustes | 0.51 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.49 | 0.14 |

| Cyanistes caeruleus | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.15 | 0.94 | 0.48 | 0.20 | 0.33 |

| Dendrocopos major | 0.47 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 0.21 | 0.61 | 1.00 |

| Dendrocopos medius | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Erithacus rubecula | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.89 |

| Ficedula hypoleuca | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Fringilla coelebs | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.74 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.05 |

| Muscicapa striata | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Parus cristatus | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Parus major | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.85 |

| Parus montanus | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.72 | 0.91 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.67 |

| Parus palustris | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.69 | 0.43 |

| Periparus ater | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.97 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.90 |

| Phoenicurus phoenicurus | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Phylloscopus collybita | 0.79 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.76 |

| Phylloscopus sibilatrix | 0.48 | 1.00 | n/a | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.35 | 0.39 |

| Phylloscopus trochilus | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.75 | 0.26 | 0.12 |

| Prunella modularis | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.14 | 0.46 |

| Pyrrhula pyrrhula | 0.01 | 0.48 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

| Sitta europaea | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.89 |

| Sturnus vulgaris | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Sylvia atricapilla | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.09 |

| Troglodytes troglodytes | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Turdus merula | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 |

| Turdus philomelos | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Turdus viscivorus | 0.79 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.09 |

Table A2.

Test results for analyzing differences in variation within species in-between the four different habitat categories for the set of ecological and morphological traits of 28 common bird species in Germany based on own data. Gray-shaded and bold indicates p-values < 0.05. Underlined p-values indicate ANOVA, otherwise a Kruskal-Wallis test has been performed. n/a indicates no data available for that trait or too low N.

Table A2.

Test results for analyzing differences in variation within species in-between the four different habitat categories for the set of ecological and morphological traits of 28 common bird species in Germany based on own data. Gray-shaded and bold indicates p-values < 0.05. Underlined p-values indicate ANOVA, otherwise a Kruskal-Wallis test has been performed. n/a indicates no data available for that trait or too low N.

| Species | Fat | Muscle Score | Body Mass | Bill Height | Bill Length | Tarsus | Wing | p3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aegithalos caudatus | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Certhia familiaris | 0.51 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 0.66 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.22 |

| Coccothraustes coccothraustes | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.60 | 0.83 |

| Cyanistes caeruleus | 0.90 | 0.58 | 0.84 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.39 |

| Dendrocopos major | 0.93 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.83 | 0.39 | 0.85 | 0.27 |

| Dendrocopos medius | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Erithacus rubecula | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Ficedula hypoleuca | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Fringilla coelebs | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.99 | 0.30 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.82 | 0.99 |

| Muscicapa striata | n/a | n/a | 0.46 | 0.73 | 0.12 | 0.51 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Parus cristatus | 0.16 | n/a | 0.18 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.30 | 0.73 | 0.82 |

| Parus major | 0.44 | 0.88 | 0.66 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.07 |

| Parus montanus | 0.26 | 0.55 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.60 | 0.26 |

| Parus palustris | 0.73 | 0.12 | 0.46 | 0.65 | 0.24 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.73 |

| Periparus ater | 0.56 | 0.18 | 0.44 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.28 | 0.13 |

| Phoenicurus phoenicurus | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Phylloscopus collybita | 0.30 | 0.42 | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.70 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.57 |

| Phylloscopus sibilatrix | 0.48 | 1.00 | n/a | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.35 | 0.39 |

| Phylloscopus trochilus | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.83 | 0.87 |

| Prunella modularis | 0.20 | 0.45 | 0.57 | 0.72 | 0.19 | 0.84 | 0.60 | 0.32 |

| Pyrrhula pyrrhula | 0.29 | 0.90 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.76 | 0.18 |

| Sitta europaea | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.43 | 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.87 | 0.24 | 0.14 |

| Sturnus vulgaris | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Sylvia atricapilla | 0.01 | 0.55 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Troglodytes troglodytes | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.97 | 0.62 |

| Turdus merula | 0.23 | 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.26 | 0.84 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Turdus philomelos | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.95 | 0.15 | 0.70 | 0.13 | 0.66 | 0.56 |

| Turdus viscivorus | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.85 | 0.03 | 0.51 | 0.60 |

References

- Petchey, O.L.; Evans, K.L.; Fishburn, I.S.; Gaston, K.J. Low functional diversity and no redundancy in british avian assemblages. J. Anim. Ecol. 2007, 76, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petchey, O.L.; Gaston, K.J. Functional diversity: Back to basics and looking forward. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenzweig, M.L. Species Diversity in Space and Time; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, B.J.; Enquist, B.J.; Weiher, E.; Westoby, M. Rebuilding community ecology from functional traits. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006, 21, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heino, J. Functional biodiversity of macroinvertebrate assemblages along major ecological gradients of boreal headwater streams. Freshw. Biol. 2005, 50, 1578–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, R.D.; Cox, S.B.; Strauss, R.E.; Willig, M.R. Patterns of functional diversity across an extensive environmental gradient: Vertebrate consumers, hidden treatments and latitudinal trends. Ecol. Lett. 2003, 6, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.A.; Karp, D.S.; DeClerck, F.; Kremen, C.; Naeem, S.; Palm, C.A. Functional traits in agriculture: Agrobiodiversity and ecosystem services. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bregman, T.P.; Sekercioglu, C.H.; Tobias, J.A. Global patterns and predictors of bird species responses to forest fragmentation: Implications for ecosystem function and conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 169, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, T.J.; Sheard, C.; Cottee-Jones, H.E.W.; Bregman, T.P.; Tobias, J.A.; Whittaker, R.J. Ecological traits reveal functional nestedness of bird communities in habitat islands: A global survey. Oikos 2015, 124, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklefs, R.E. Passerine morphology: External measurements of ca. One-quarter of passerine bird species. Ecology 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandewalle, M.; de Bello, F.; Berg, M.P.; Bolger, T.; Dolédec, S.; Dubs, F.; Feld, C.K.; Harrington, R.; Harrison, P.A.; Lavorel, S.; et al. Functional traits as indicators of biodiversity response to land use changes across ecosystems and organisms. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 2921–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Bossdorf, O.; Gockel, S.; Hänsel, F.; Hemp, A.; Hessenmöller, D.; Korte, G.; Nieschulze, J.; Pfeiffer, S.; Prati, D.; et al. Implementing large-scale and long-term functional biodiversity research: The biodiversity exploratories. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2010, 11, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, S.C.; Lüdtke, B.; Kaiser, S.; Kienle, J.; Schaefer, H.M.; Segelbacher, G.; Tschapka, M.; Santiago-Alarcon, D. Forests of opportunities and mischief: Disentangling the interactions between forests, parasites and immune responses. Int. J. Parasitol. 2016, 46, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renner, S.C. Disentangling the Interactions Between Forests, Parasites, and Immune Responses. In Proceedings of the European Ornithologsits’ Union, Badajoz, Spain, 24–28 August 2015; EOU: Badajoz, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Renner, S.C.; Gossner, M.M.; Kahl, T.; Kalko, E.K.; Weisser, W.W.; Fischer, M.; Allan, E. Temporal changes in randomness of bird communities across central europe. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüdtke, B.; Moser, I.; Santiago-Alarcon, D.; Fischer, M.; Kalko, E.K.V.; Schaefer, H.M.; Suarez-Rubio, M.; Tschapka, M.; Renner, S.C. Associations of forest type, parasitism and body condition of two european passerines, fringilla coelebs and sylvia atricapilla. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renner, S.C.; Baur, S.; Possler, A.; Winkler, J.; Kalko, E.K.; Bates, P.J.; Mello, M.A. Food preferences of winter bird communities in different forest types. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e53121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, K.; O’Hara, R.B.; Bohm, S.M.; Gockel, S.; Hemp, A.; Renner, S.C.; Pfeiffer, S.; Boehning-Gaese, K.; Kalko, E.K.V. Trait-dependent occupancy dynamics of birds in temperate forest landscapes: Fine-scale observations in a hierarchical multi-species framework. Anim. Conserv. 2012, 15, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliveres, S.; Manning, P.; Prati, D.; Gossner, M.; Alt, F.; Arndt, H.; Baumgartner, V.; Binkenstein, J.; Birkhofer, K.; Blaser, S.; et al. Locally rare species influence grassland ecosystem multifunctionality. Philos. Trans. Ser. B 2016, 371, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliveres, S.; van der Plas, F.; Manning, P.; Prati, D.; Gossner, M.M.; Renner, S.C.; Alt, F.; Arndt, H.; Baumgartner, V.; Binkenstein, J.; et al. Biodiversity at multiple trophic levels is needed for ecosystem multifunctionality. Nature 2016, 536, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, E.; Bossdorf, O.; Dormann, C.F.; Prati, D.; Gossner, M.M.; Tscharntke, T.; Blüthgen, N.; Bellach, M.; Birkhofer, K.; Boch, S.; et al. Interannual variation in land-use intensity enhances grassland multidiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluthgen, N.; Simons, N.K.; Jung, K.; Prati, D.; Renner, S.C.; Boch, S.; Fischer, M.; Holzel, N.; Klaus, V.H.; Kleinebecker, T.; et al. Land use imperils plant and animal community stability through changes in asynchrony rather than diversity. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gossner, M.M.; Getzin, S.; Lange, M.; Pašalić, E.; Türke, M.; Wiegand, K.; Weisser, W.W. The importance of heterogeneity revisited from a multiscale and multitaxa approach. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 166, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossner, M.M.; Lewinsohn, T.M.; Kahl, T.; Grassein, F.; Boch, S.; Prati, D.; Birkhofer, K.; Renner, S.C.; Sikorski, J.; Wubet, T.; et al. Land-use intensification causes multitrophic homogenization of grassland communities. Nature 2016, 540, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, N.K.; Weisser, W.W.; Gossner, M.M. Multi-taxa approach shows consistent shifts in arthropod functional traits along grassland land-use intensity gradient. Ecology 2016, 97, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Blotzheim, U.N.G.; Bauer, K.M. Handbuch Der Vögel Mitteleuropas; Aula: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Swiss Ornithological Institute. Birds of Switzerland. Available online: http://www.vogelwarte.ch/en/birds/birds-of-switzerland/ (accessed on 18 April 2016).

- Svensson, L. Identification Guide to European Passerines; British Trust for Ornithology: Stockholm, Sweden, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Päckert, M.; Dietzen, C.; Martens, J.; Wink, M.; Kvist, L. Radiation of atlantic goldcrests regulus regulus spp.: Evidence of a new taxon from the canary islands. J. Avian Biol. 2006, 37, 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Päckert, M.; Martens, J.; Kosuch, J.; Nazarenko, A.A.; Veith, M. Phylogenetic signal in the song of crests and kinglets (aves: Regulus). Evol. Int. J.Org. Evol. 2003, 57, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Päckert, M.; Martens, J.; Sun, Y.H. Phylogeny of long-tailed tits and allies inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear markers (aves: Passeriformes, aegithalidae). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2010, 55, 952–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eck, S.; Fiebig, J.; Fiedler, W.; Heynen, I.; Nicolai, B.; Töpfer, T.; Winkler, R.; Woog, F. Measuring Birds/Vögel Vermessen; Christ Media Natur: Minden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hatchwell, B.; Davies, N. An experimental study of mating competition in monogamous and polyandrous dunnocks, prunella modularis: Ii. Influence of removal and replacement experiments on mating systems. Anim. Behav. 1992, 43, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing http://www.R-project.Org; v 3.1.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).