Abstract

This dataset presents a real-world lipidomics resource for developing and benchmarking quality control methods, batch effect detection algorithms, and data validation workflows. The data originates from a cross-sectional clinical study of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) patients (n = 81) and healthy controls (n = 26), matched for age, sex, and body mass index, which was collected at a tertiary university rheumatology center. Subtle laboratory irregularities were detected only through advanced unsupervised analysis, after passing conventional quality control and standard analytical methods. Blood samples were processed using standardized protocols and analyzed using high-resolution and tandem mass spectrometry platforms. Both targeted and untargeted lipid assays captured lipids of several classes (including carnitines, ceramides, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, glycerolipids, fatty acids, sterols and esters, endocannabinoids). The dataset is organized into four comma-separated value (CSV) files: (1) Box–Cox-transformed and imputed lipidomics values; (2) outlier-cleaned and imputed values on the original scale; (3) metadata including clinical classifications, biological sex, and batch information for all assay types and control sample processing dates; and (4) a variable-level description file (readme.csv). The 292 lipid variables are named according to LIPID MAPS classification and standardized nomenclature. Complete batch documentation and FAIR-compliant data structure make this dataset valuable for testing the robustness of analytical pipelines and quality control in lipidomics and related omics fields. This unique dataset does not compete with larger lipidomics quality control datasets for comparisons of results but provides a unique, real-life lipidomics dataset displaying traces of the laboratory sample processing schedule, which can be used to challenge quality control frameworks.

Dataset: Repository name: Mendeley Data; Data identification number: doi: 10.17632/32xts2zxdc.3; URL to data: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/32xts2zxdc/3 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

Dataset License: CC BY 4.0

1. Summary

This dataset presents a cautionary case study in lipidomics quality control and data exploration. The lipidomics data successfully passed quality control measures at a central analytical unit and met initial expectations during exploratory analysis. Planned supervised analyses identified lipid markers that appeared to be regulated in a disease context, with findings supported by existing literature. However, a subtle irregularity detected during unsupervised data analysis revealed underlying data quality issues that prevented manuscript completion. This case highlights critical limitations in current quality control procedures (see also Section 4.4.) and data exploration workflows, as well as those established in the analytical laboratory where the present dataset was generated [1,2].

The dataset is therefore unsuitable for drawing biological conclusions about lipidomics disease patterns. Instead, it serves as a valuable real-world resource for testing and validating laboratory and data-science processing workflows, including the identification of batch- and sampling processing errors and incomplete or missing metadata, enabling the detection of irregularities in lipidomics data.

The original study targeted psoriatic arthritis (PsA), a clinically relevant disease model for investigating lipid-mediated inflammatory processes. Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) are conditions characterized by overlapping autoimmune and autoinflammatory features [3]. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA), a prototypical IMID, affects nearly 20% of patients with psoriasis [4] and presents with joint and connective tissue involvement, bone changes, and diverse clinical manifestations [5,6,7]. The disease shows variable prevalence (estimated at 112 per 100,000 adults) influenced by risk factors including age, sex, and body mass index, with higher rates in Europe and North America compared to Asia and South America [8].

This dataset presents a cautionary case study in lipidomics quality control and data exploration. The original cohort comprised n = 140 samples (n = 90 PsA patients + n = 50 healthy controls [9]), which propensity score matching for age, BMI, and sex reduced to n = 107 (n = 81 PsA patients, n = 26 controls). The sample size was deemed sufficient for disease signature detection at the time. The lipidomics data successfully passed quality control measures at a central analytical unit and met initial expectations during exploratory analysis. Planned supervised analyses identified lipid markers that appeared to be regulated in a disease context, with findings supported by existing literature. However, a subtle irregularity detected during unsupervised data analysis revealed underlying data quality issues that prevented manuscript completion.

The dataset is therefore unsuitable for drawing biological conclusions about lipidomics disease patterns. Instead, it serves as a valuable real-world resource for testing and validating laboratory and data science processing workflows despite its single-center design, disease specificity (PsA only), reduced sample size post-matching (140→107), and imbalanced groups (81:26). For broader applications, researchers should complement this dataset with larger, multi-disease lipidomics resources such as LIPID MAPS consortia.

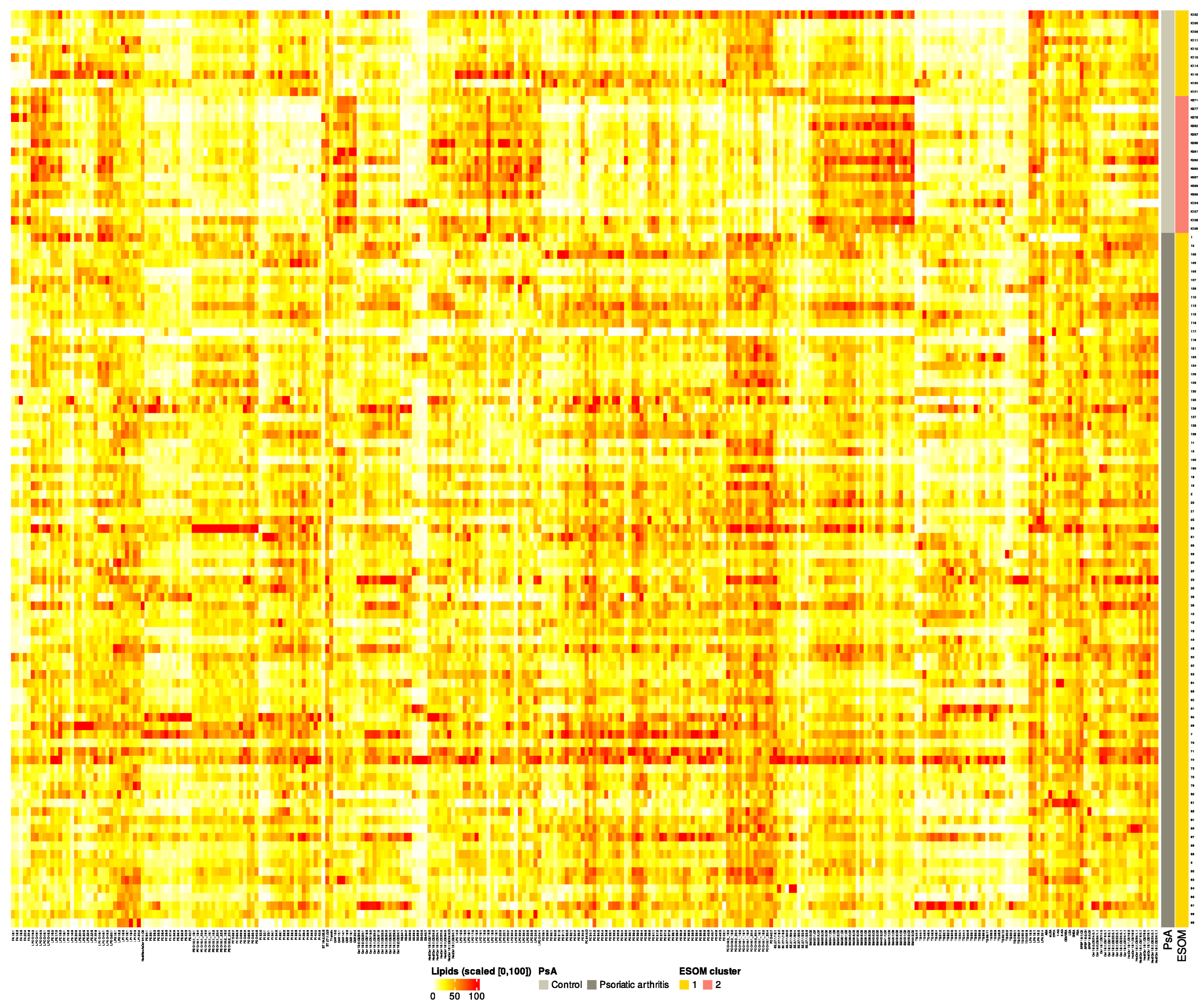

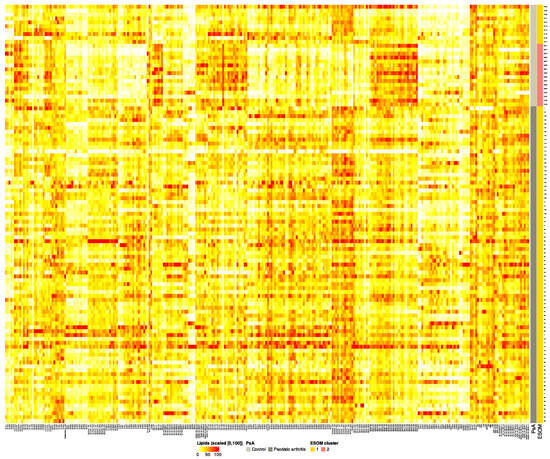

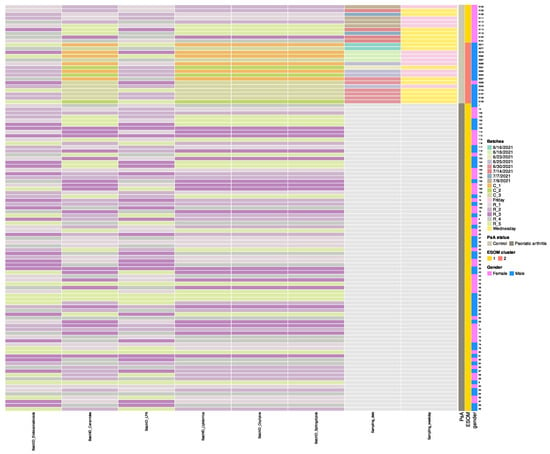

Detailed reanalysis of this cross-sectional PsA lipidomics dataset revealed subtle batch effects linked to laboratory workflow variations despite passing initial batch-wise quality controls (Figure 1). We provide the complete dataset along with documentation of the quality control process, facilitating its use as a benchmark for developing more robust analytical pipelines and quality assessment strategies in lipidomics research.

Figure 1.

Heatmap of lipid abundance across samples, ordered by Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and ESOM cluster status. Color intensity represents relative abundance, scaled from 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest), for intuitive visualization. Warm colors (yellow to red) indicate higher abundance, while cool colors (blue) indicate lower abundance. Row annotations show the PsA and ESOM cluster classification for each sample. This visualization highlights differences in lipid profiles between patient groups and clusters. Note that the prior classes challenge standard clustering algorithms, which seem incapable of detecting clusters that reflect the underlying class structure. Therefore, more sophisticated methods are required; this data set is a benchmark for them.

2. Data Description

2.1. General Properties of the Dataset

The dataset comprises four files: three interrelated files that provide (i) variables (raw and processed) and metadata, enabling the tracing of laboratory or processing workflows within the lipid data, and a separate readme file that offers a high-level overview of the dataset’s structure and content. The first two files (described below) contain lipid data in two forms: extensively preprocessed values suitable for statistical analysis and back-transformed values on the original measurement scale. The third file documents metadata, including clinical classifications, an unsupervised data-driven classification that uncovered analytical irregularities, and complete batch information for all assay types. This cohesive structure supports diverse use cases: evaluating quality control procedures, testing batch effect detection algorithms, validating data preprocessing workflows, and developing robust unsupervised analysis methods. While the dataset is not intended to inform biological conclusions, its primary value lies in documenting the transition from seemingly acceptable to problematic data, making it highly suitable for benchmarking quality assessment strategies in lipidomics studies.

2.2. Description of the Single Data Files

The dataset includes four comma-separated values (CSV) files, each of which plays a specific role in representing the lipidomics data and its associated metadata.

2.2.1. “PsA_lipids_BC.csv”

This file contains the primary lipidomics data matrix with 107 rows (cases) and 293 columns. The first column (“ID”) lists arbitrary subject identifiers. Columns 2 through 293 contain plasma lipid measurements (Table 1) that have undergone extensive preprocessing:

Table 1.

Overview of lipid classes, abbreviations, and analytical methods.

- Propensity score matching (PSM) [10] for age, using logistic regression with nearest-neighbor matching (1:1) within the region of common support (psmatch2, Stata/IC 15.1 for Linux, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), reduced confounding between PsA patients (n = 81) and controls (n = 26); post-matching balance of age, sex, and BMI confirmed by ANOVA and chi-square tests.

- Box–Cox transformation to normalize distributions [11], implemented via the “ABCstats” R package (https://github.com/Waddlessss/ABCstats, (accessed on 12 December 2025) [12]).

- The original lipidomics matrix was complete with no missing values. Outliers were removed using the boxplot method, which targets extreme values defined as the third quartile plus three times the interquartile range (IQR) or below the first quartile minus three IQRs. This method was implemented in the R package “rstatix” (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix, (accessed on 12 December 2025) [13]). This process removed 0.017% of the lipidomics variable values and created missingness.

- Imputation of missing and outlier values (totaling only 14 values) was performed using multivariate random forest imputation from the R package “miceRanger” (https://cran.r-project.org/package=miceRanger, (accessed on 12 December 2025) [14]) with parameters m = 1 (1 imputation), maxiter = 1 (1 iteration), valueSelector = “meanMatch”, meanMatchCandidates = max(5, 1% of samples), and returnModels = TRUE. Additionally, 60 highly correlated lipid variables (r > 0.9) were removed during preprocessing.

Lipid variables are categorized following the LIPID MAPS classification system [15] and standardized nomenclature [16]. Variables are named using class abbreviations followed by specific member IDs, following the standardized nomenclature proposed recently [16]. The dataset includes diverse lipid classes such as carnitines, ceramides, glycerophospholipids (e.g., phosphatidylcholine and lysophospholipids), sphingolipids (e.g., sphingomyelin, gangliosides), glycerolipids (e.g., triacylglycerols, diacylglycerols), fatty acids, sterols and esters, endocannabinoids, and others (see Table 1).

2.2.2. “PsA_lipids_orig_values.csv”

This file contains the same 107 cases and 293 columns but provides the lipid values on their original scale. Values represent the inverse Box–Cox transformed, outlier-cleaned, and imputed plasma lipid values. The first column again contains the arbitrary subject IDs, followed by the 292 lipid variables.

2.2.3. “PsA_classes.csv”

This metadata file includes 107 rows and 12 columns. The first column lists subject IDs consistent with the other files. Columns 2 to 4 provide three classification variants:

- “PsA”: Original clinical classification distinguishing Psoriatic arthritis patients from controls.

- “ESOM”: An unsupervised classification derived from projecting the transformed dataset onto a self-organizing feature map of artificial neurons (ESOM/U-matrix) [17], revealing a distinct subset (class “2”) associated with laboratory workflow differences.

- “gender”: Biological sex of subjects (“Male” or “Female”).

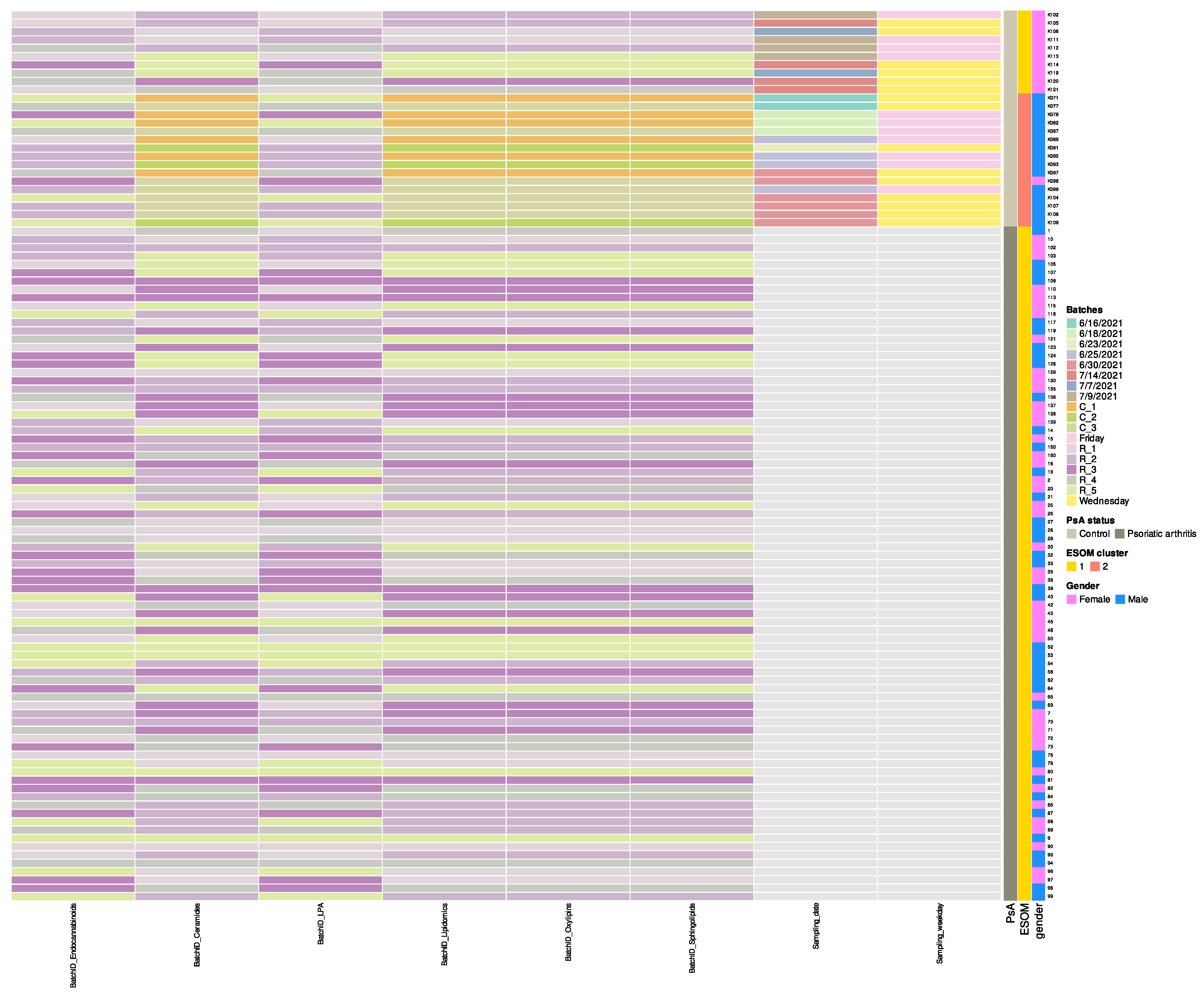

- Columns 5 through 10 document analytical batch identifiers for each assay type: “BatchID_Endocannabinoids”, “BatchID_Ceramides”, “BatchID_LPA”, “BatchID_Lipidomics”, “BatchID_Oxylipins”, and “BatchID_Sphingolipids”. Most samples (PsA patients) were analyzed in five batches (BatchID prefix “R_1” through “R_5”), while 16 control samples were processed in three batches (BatchID prefix “C_1” through “C_3”) approximately one month earlier (June vs. July 2021) (Figure 2). Both disease groups appear intermingled across multiple analytical runs within each batch type. These temporal batch differences among controls were subsequently identified by unsupervised ESOM analysis as the primary driver of control sample bifurcation (forthcoming analysis paper). “BatchID_Lipidomics” contains additional lipids not included in other batches.

Figure 2. Heatmap of analytical batch assignments across samples, ordered by Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and ESOM cluster status. Color tiles represent original batch identifiers for each assay type (Endocannabinoids, Ceramides, LPA, Lipidomics, Oxylipins, Sphingolipids), with controls predominantly utilizing C_1, C_2, C_3 batches and patients utilizing R_1 through R_5 batches. Both disease groups appear intermingled across multiple analytical runs within each batch type, minimizing systematic batch effects between groups. Row annotations (right) display PsA status, ESOM cluster classification, and gender for each sample. Sampling dates and weekdays (specific to controls) are included in the matrix.

Figure 2. Heatmap of analytical batch assignments across samples, ordered by Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and ESOM cluster status. Color tiles represent original batch identifiers for each assay type (Endocannabinoids, Ceramides, LPA, Lipidomics, Oxylipins, Sphingolipids), with controls predominantly utilizing C_1, C_2, C_3 batches and patients utilizing R_1 through R_5 batches. Both disease groups appear intermingled across multiple analytical runs within each batch type, minimizing systematic batch effects between groups. Row annotations (right) display PsA status, ESOM cluster classification, and gender for each sample. Sampling dates and weekdays (specific to controls) are included in the matrix. - Columns 11 and 12 provide processing metadata specific to control subjects: “Sampling_date” (June–July 2021) and “Sampling_weekday”. The complete batch processing strategy is visualized in Figure 2.

- “Sampling_weekday”: Day of the week for control sample collection.

All above files maintain consistent row order by subject ID, facilitating cross-referencing. The dataset adheres to FAIR principles, promoting interoperability and reuse within the lipidomics community. Its standardized structure supports integration with lipid databases such as LIPID MAPS Structure Database (LMSD) for comprehensive data analysis [15].

2.2.4. “readme.csv”

In addition to the three interrelated files, a readme.csv file is provided to describe the lipidomics dataset at the level of individual variables. Unlike the metadata files, this file directly corresponds to the lipid variables included in the study, with the number of rows matching the total number of variables in the dataset.

This file contains 292 rows (equaling the number of lipid variables) and seven columns, summarizing the following information for each lipid variable:

- “variable_name”: The specific lipid variable (analyte) name, consistent with how it appears in the dataset’s raw and processed files.

- “unit”: The unit of measurement for the variable. Lipid screening results are expressed in arbitrary units, calculated as the chromatographic peak area in relation to the chromatographic peak area of the corresponding lipid-class-specific internal standard.

- “class_name”: The lipid class to which the variable belongs (e.g., “Phosphatidylcholines,” “Triacylglycerols”).

- “class_code”: Abbreviations used to identify the corresponding lipid class (e.g., “PC” for Phosphatidylcholines, “TG” for Triacylglycerols).

- “analytical_method_category”: The analytical method applied to quantify the lipid variable, either “Lipid screening” (broad profiling) or “Lipid targeted” (target-specific assays).

- “LLOQ”: Lower limit of quantification (NA for screening lipids; numeric values such as “3” ng/mL or “25” pg/mL for targeted lipids).

- “ULOQ”: Upper limit of quantification (NA for screening lipids; numeric values such as “250” ng/mL or “6250” pg/mL for targeted lipids).

3. Clustering Analysis as a Demonstration of Dataset Complexity

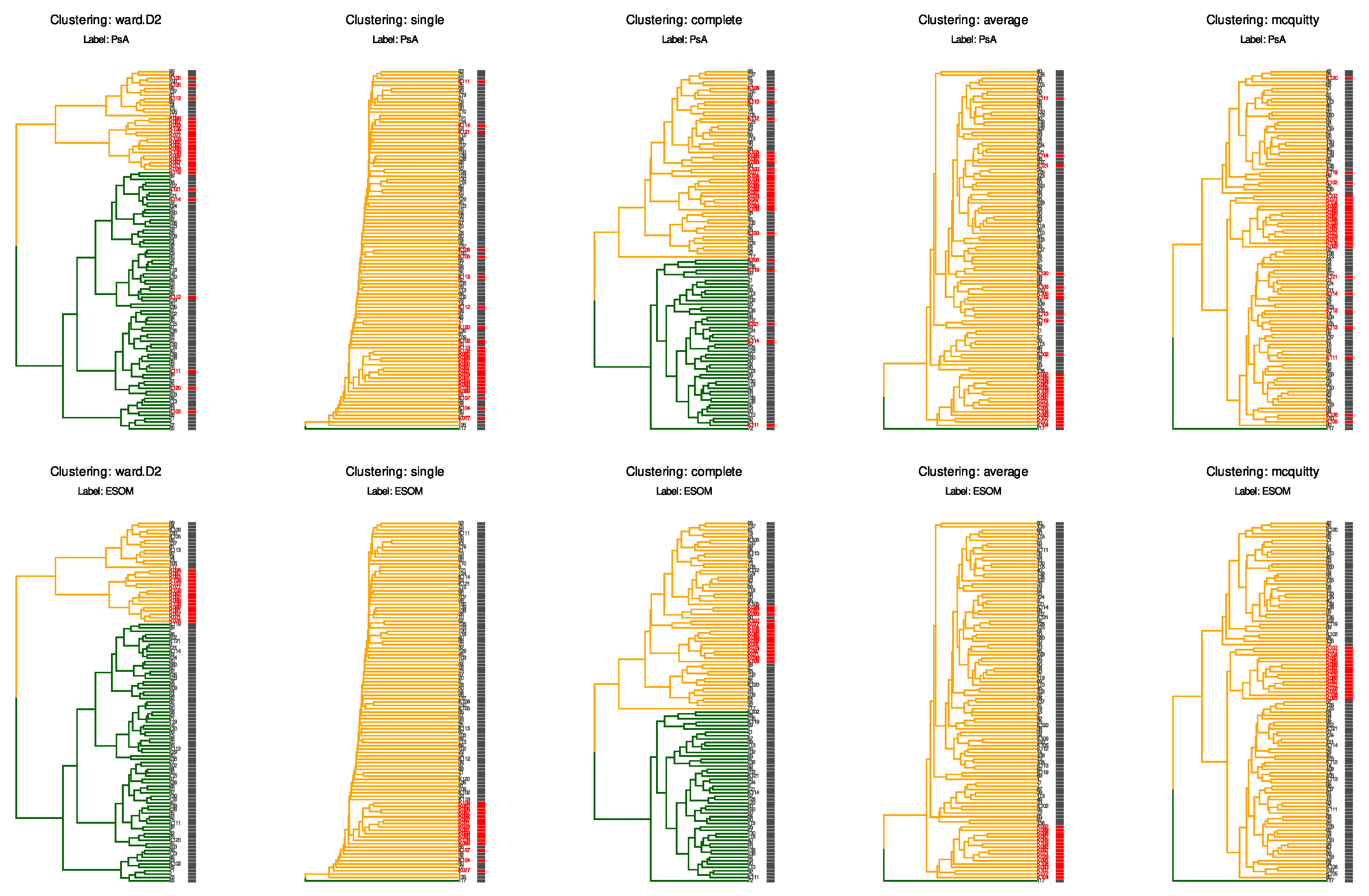

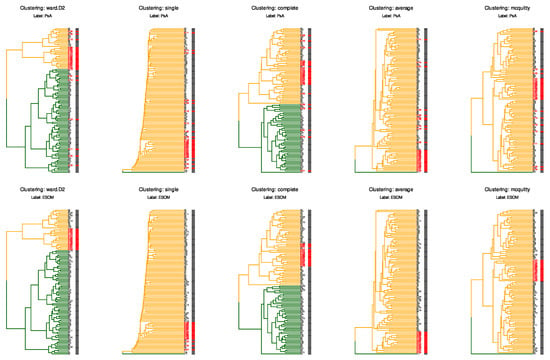

To illustrate the analytical challenges posed by this dataset, we performed ad hoc hierarchical clustering using the Euclidean distance and five established methods (Ward’s linkage, single, complete, linkage, and McQuitty linkage) on the scaled and centered Box–Cox transformed lipid data (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Hierarchical clustering analysis reveals the challenge of detecting subtle batch effects. Dendrograms show ad hoc hierarchical clustering of the scaled and centered data from “PsA_lipids_BC.csv”, using the Euclidean distance and five different linkage methods (Ward’s linkage (“WardD2”), single, complete, average, and McQuitty linkage). The two rows illustrate how ad hoc clustering may or may not correspond to an a priori classification. Dendrogram branch colors (dark green and orange) represent the two data-driven clusters, while the row labels and the small colored bars immediately to their right indicate the chosen a priori class for each sample. Top row: samples are labeled by clinical classification with Psoriatic arthritis patients shown in darg gray and controls in red (column “PsA” in the file “PsA_classes.csv”). Bottom row: samples are labeled by ESOM-derived classification with class “1” in gray and class “2” (column “ESOM” in the file “PsA_classes.csv”; the 16 control samples from earlier batches with different laboratory workflow) in red. Branch colors (dark green and orange) indicate the two major clusters according to the expectation of k = 2 (PsA versus controls, 2 detected ESOM clusters). None of the clustering methods successfully separated the ESOM class “2” samples from the rest of the dataset, even though these control samples were processed on different dates, which was reflected in their projection onto two-dimensional planes.

The analysis demonstrates that conventional clustering algorithms fail to identify the underlying structure revealed by advanced semi-supervised methods. This example underscores the suitability of the dataset as a benchmark: users can test whether their analytical workflows successfully identify the documented batch structure, thereby validating the sensitivity of their quality control procedures.

When samples are labeled by their original clinical classification (PsA patients vs. controls, top row; column “PsA” in the file “PsA_classes.csv”), all clustering methods produce groupings that do not correspond to the disease status. Similarly, when samples are labeled according to the ESOM-derived classification (bottom row), which identifies the subset affected by laboratory workflow variations (ESOM class “2”, marked in red; column “ESOM” in the file “PsA_classes.csv”), the clustering methods again fail to separate this group from the remaining samples (ESOM class “1”, marked in gray). This is particularly notable because the ESOM classification precisely identifies the 16 control samples processed in earlier batches with different laboratory workflows. In contrast to these conventional hierarchical clustering approaches, the ESOM method successfully detected and separated this analytical subgroup through its combination of emergent self-organizing map projection and subsequent density-based clustering on the resulting U-matrix [17].

The consistent failure of multiple hierarchical clustering approaches, despite using different linkage criteria and distance metrics, underscores the subtle nature of the batch effect present in this dataset. The fact that these widely used clustering methods cannot detect a structure that is clearly present and biologically meaningful highlights why this batch effect also evaded detection by standard quality control procedures and conventional data projection methods such as PCA [18,19] and PLS-DA [20]. This characteristic makes the dataset particularly valuable for benchmarking quality control workflows and developing more sensitive batch effect detection strategies in lipidomics research.

4. Methods

4.1. Patients and Study Design

The present analysis focused on lipidomic patterns in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) in a cohort of which the clinical details have been described separately [21]. This cross-sectional study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany (approval numbers 19-492 and 20-982). Informed written consent was obtained from each participant. Inclusion criteria included a minimum age of 18 years and a clinical diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis.

Additional PsA patients were enrolled compared to the earlier published study, resulting in an initial cohort of n = 90 PsA patients, of whom n = 50 (62.5%) had been part of previously reported analyses [21]. For the lipidomics analyses, samples from n = 50 healthy adult subjects were added from the Frankfurt, Germany, branch of the German Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service (see also [9]). After matching patients and controls for age, body mass index (BMI), and sex, the present dataset comprised lipidomics data from n = 81 PsA patients and n = 26 controls.

4.2. Blood Sample Collection

The accurate determination of the lipidome is critically dependent on the correct performance of blood sampling and appropriate preanalytical procedures [1,22]. Since samples were predominantly collected during routine consultations at the rheumatology outpatient clinic, fasting could not be ensured for all study participants. This also applies to the control group. However, correct filling volumes were strictly adhered to during sampling to avoid underfilling, and dead volume in collection set tubing was carefully avoided.

Blood samples were collected using S-Monovette® collection tubes from Sarstedt (SARSTEDT AG & Co. KG, Nümbrecht, Germany) in the following order: (1) GlucoExact (3.1 mL) and (2) K3EDTA (7.5 mL). Blood samples were gently inverted several times and immediately stored in ice water until centrifugation, which was performed within 20 min at 2000× g for 10 min in a cooled centrifuge (4 °C).

Plasma was immediately separated from cells after centrifugation. For K3EDTA tubes, the entire plasma (approximately 3.5 mL) was carefully transferred to labeled 5 mL transfer tubes, homogenized by vortexing, and aliquoted into 1.5 mL Eppendorf (Eppendorf SE, Hamburg, Germany) tubes (three aliquots of 1 mL each and one aliquot with the remaining volume). For GlucoExact tubes, the entire plasma (approximately 1.5 mL) was transferred to a labeled 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube, homogenized, and 0.5 mL was transferred to another tube.

Samples were stored at ≤−70 °C as soon as possible, with temporary storage at ≤−20 °C allowed for a maximum of one week if necessary. The entire process from collection to final storage was completed within one hour and meticulously documented to ensure sample integrity for lipidomic analysis.

4.3. Lipidomics Analysis

Prior to lipid analysis, the required sample volumes for each analysis were prepared from a 1 mL plasma aliquot. The aliquot was thawed under controlled conditions, appropriate volumes were extracted and divided for different analyses, and these samples were then stored at ≤−70 °C until further processing.

All plasma samples were analyzed using a well-established LC-MS platform described in detail in a previous publication [1]. This platform integrates liquid chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS) for quantification of abundant lipids and polar metabolites, alongside liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for detection of less prevalent lipid mediators, including oxylipins, endocannabinoids, lysophosphatidic acids (LPAs), and sphingolipids. Due to their pre-analytical instability, endocannabinoids and LPAs were analyzed in plasma samples containing citrate/sodium fluoride additives (GlucoExact) instead of K3EDTA plasma [1,22].

4.4. Batch Structure and Quality Control Considerations

Notably, most samples (n = 91) were analyzed in five batches, while 16 control samples were processed earlier in three separate batches with differences in laboratory workflow (Figure 2). The data were processed according to the established sample handling and data quality control protocols established in the local laboratory. Details have been described previously [1,2]. Briefly, traditional quality control included acceptance criteria for each analytical run: (i) back-calculated concentrations of calibration standards within ±15% of nominal values (±20% for LLOQ), (ii) at least 75% of calibration standards (minimum six) fulfilling accuracy criteria, (iii) accuracy of QC samples within ±15% of nominal values, and (iv) at least 67% of QC samples at each concentration level complying with these criteria. For screening methods, compounds were excluded if less than 80% of values exceeded the extracted blank sample signal by at least a factor of 2, or if the coefficient of variance in pooled QC samples exceeded 20% for lipids or 30% for polar metabolites. QC samples were measured at regular intervals throughout each batch (every 10 samples), and long-term control samples were used to track system performance across multiple analytical runs using method-specific control charts [2]. Data are provided in a FAIR-compliant structure to support reproducibility. Lipid identifiers were harmonized using the R package “rgoslin” (https://doi.org/doi:10.18129/B9.bioc.rgoslin, (accessed on 12 December 2025) [23]), following the standardized lipid shorthand nomenclature widely accepted in the lipidomics community. This approach ensures consistency with established databases such as LIPID MAPS and enables straightforward mapping to other datasets for users interested in extended comparative analyses.

5. Recommended Use

This dataset provides a valuable resource for developing and validating quality control methodologies in lipidomics and related metabolomics workflows, including the identification of laboratory errors and the handling of incomplete or missing metadata. Its inclusion of subtle data inconsistencies and incomplete annotations makes it especially useful for testing workflow robustness under non-ideal, real-world conditions. The presence of subtle laboratory workflow artifacts that were not detected by conventional quality control procedures makes this dataset particularly suited for

- Benchmarking batch effect detection algorithms: The dataset contains documented temporal variation across collection periods and analytical batches, enabling researchers to test the sensitivity of their quality control frameworks to real-world laboratory processing patterns.

- Evaluating dimensionality reduction and exploratory analysis methods: Researchers can assess how different analytical approaches reveal or obscure systematic technical variation relative to biological signal in complex lipidomics data.

- Testing classification and variable selection strategies: The dataset structure supports comparative evaluation of how supervised and unsupervised methods perform when biological and technical sources of variation coexist at different magnitudes.

- Developing robust preprocessing pipelines: The inclusion of both transformed and original-scale data, along with comprehensive metadata, allows methodologists to test normalization, scaling, and imputation strategies under realistic conditions where quality issues are subtle rather than obvious.

- Training and validation of integrative analytical frameworks: The dataset’s complexity and documented characteristics make it suitable for testing multi-method approaches to identifying samples or variables that may be affected by uncontrolled technical factors.

The dataset is not intended to replace large-scale quality control reference datasets for method comparison or biological discovery in psoriatic arthritis research. Rather, it serves as a challenging test case for methods aimed at detecting laboratory workflow traces that can confound biological interpretation despite passing standard quality metrics.

Author Contributions

J.L.: Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, and Revision of the Manuscript; R.G.: Data Curation, and Writing—Review and Editing; L.H.: Data Curation and Writing—Review and Editing, and Revision of the Manuscript; F.B.: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, and Funding acquisition; G.G.: Writing—Review and Editing and Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

These observations were made in the context of cross-sectional, multi-omics projects on immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including rheumatic diseases. These studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki on Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. They were also approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty at Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main, Germany (approval numbers 19-492 and 20-982). Written informed consent, including permission for the anonymized publication of data and study results, was obtained from each participant. The responsible ethics review board has explicitly approved the upload of the anonymized data to a public repository.

Data Availability Statement

Repository name: Mendeley Data; Data identification number: doi: 10.17632/32xts2zxdc.3; URL to data: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/32xts2zxdc/3, (accessed on 12 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Sens, A.; Rischke, S.; Hahnefeld, L.; Dorochow, E.; Schäfer, S.M.G.; Thomas, D.; Köhm, M.; Geisslinger, G.; Behrens, F.; Gurke, R. Pre-analytical sample handling standardization for reliable measurement of metabolites and lipids in LC-MS-based clinical research. J. Mass. Spectrom. Adv. Clin. Lab. 2023, 28, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rischke, S.; Hahnefeld, L.; Burla, B.; Behrens, F.; Gurke, R.; Garrett, T.J. Small molecule biomarker discovery: Proposed workflow for LC-MS-based clinical research projects. J. Mass. Spectrom. Adv. Clin. Lab. 2023, 28, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surace, A.E.A.; Hedrich, C.M. The Role of Epigenetics in Autoimmune/Inflammatory Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alinaghi, F.; Calov, M.; Kristensen, L.E.; Gladman, D.D.; Coates, L.C.; Jullien, D.; Gottlieb, A.B.; Gisondi, P.; Wu, J.J.; Thyssen, J.P.; et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 251–265.e219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGonagle, D.; McDermott, M.F. A proposed classification of the immunological diseases. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, J.U.; Ogdie, A.; Merola, J.F.; Ritchlin, C. Preventing psoriatic arthritis: Focusing on patients with psoriasis at increased risk of transition. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2019, 15, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogdie, A.; Schwartzman, S.; Husni, M.E. Recognizing and managing comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2015, 27, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembke, S.; Macfarlane, G.J.; Jones, G.T. The worldwide prevalence of psoriatic arthritis—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 3211–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, S.; Hahnefeld, L.; Kloka, J.A.; Ginzel, S.; Nürenberg-Goloub, E.; Zinn, S.; Vehreschild, M.J.; Zacharowski, K.; Lindau, S.; Ullrich, E.; et al. Short-term predictor for COVID-19 severity from a longitudinal multi-omics study for practical application in intensive care units. Talanta 2024, 268, 125295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G.E.; Cox, D.R. An analysis of transformations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1964, 26, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Sang, P.; Huan, T. Adaptive Box-Cox Transformation: A Highly Flexible Feature-Specific Data Transformation to Improve Metabolomic Data Normality for Better Statistical Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 8267–8276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassambara, A. rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests. R package version 0.7.3. CRAN Contrib. Packages 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. miceRanger: Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations with Random Forests. R package version 1.5.0. CRAN Contrib. Packages 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, M.J.; Andrews, R.M.; Andrews, S.; Cockayne, L.; Dennis, E.A.; Fahy, E.; Gaud, C.; Griffiths, W.J.; Jukes, G.; Kolchin, M.; et al. LIPID MAPS: Update to databases and tools for the lipidomics community. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1677–D1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebisch, G.; Fahy, E.; Aoki, J.; Dennis, E.A.; Durand, T.; Ejsing, C.S.; Fedorova, M.; Feussner, I.; Griffiths, W.J.; Köfeler, H.; et al. Update on LIPID MAPS classification, nomenclature, and shorthand notation for MS-derived lipid structures. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 1539–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultsch, A.; Lötsch, J. Machine-learned cluster identification in high-dimensional data. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017, 66, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotelling, H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. J. Educ. Psychol. 1933, 24, 498–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. LIII On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1901, 2, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, S.; Ruhe, A.; Wold, H.; Dunn, I.W.J. The Collinearity Problem in Linear Regression. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) Approach to Generalized Inverses. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 1984, 5, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rischke, S.; Poor, S.M.; Gurke, R.; Hahnefeld, L.; Köhm, M.; Ultsch, A.; Geisslinger, G.; Behrens, F.; Lötsch, J. Machine learning identifies right index finger tenderness as key signal of DAS28-CRP based psoriatic arthritis activity. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahnefeld, L.; Gurke, R.; Thomas, D.; Schreiber, Y.; Schäfer, S.M.G.; Trautmann, S.; Snodgrass, I.F.; Kratz, D.; Geisslinger, G.; Ferreirós, N. Implementation of lipidomics in clinical routine: Can fluoride/citrate blood sampling tubes improve preanalytical stability? Talanta 2020, 209, 120593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopczynski, D.; Hoffmann, N.; Peng, B.; Ahrends, R. Goslin: A Grammar of Succinct Lipid Nomenclature. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 10957–10960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.