Abstract

The AlimurgITA portal is a user-friendly and effective tool for researching Wild Edible Plants (WEPs). It provides valuable information on alimurgic plant species, aiding conservation and potential applications (agricultural, food, etc.). Users can interact with authors to report errors and contribute to the knowledge base regarding local uses. The authors will update the site every six months to include new data. Currently, the online database contains data on 1116 taxa used in 20 Italian regions: updated scientific name and link to the site Acta Plantarum, family, main synonyms, common name in Italian and regional dialect, chorotype, life form, a map showing the regions where it is known to be used, the part used, how it is used, and the bibliography. From the home page, you can search for taxa by scientific name, and there are pages dedicated to summaries of the entries: scientific name, family, chorotype, life form, method of use, and part used. Additionally, within the FuD WE PIC Project, the AlimurgITA entity list is being integrated with Italian vegetation data from the European Vegetation Archive to model WEPs richness, identify diversity hotspots, and explore the relationship between WEPs diversity and habitat types.

Dataset: AlimurgITA–Il portale delle piante alimurgiche italiane. https://alimurgita.it/ (accessed on 3 October 2025)

Dataset License: (CC-BY-NC-SA)

1. Introduction

The growing number of initiatives on biodiversity conservation makes it important to increase the sharing and accessibility of this information to a broad audience, including non-specialists in the sector.

Indeed, this information field also comprehends ethnobotanical and alimurgic information, which crosses the knowledge interests of other disciplines, like the preservation of cultural heritage, and extends to the pharmacopeia, nutraceuticals, and agriculture interests, including their application opportunities.

This scientific and cultural phenomenon has attracted great interest in Italy, especially in the last 30 years, leading to a notable increase in ethnobotanical studies.

In the field of WEPs (an acronym for Wild Edible Plants), the growing number of data published by the specialized literature has brought about the need to structure and organize this data in a reasoned and systematic framework to make knowledge about alimurgic plants easier to access and browse over the internet, through a public open website AlimurgITA (available at https://alimurgita.it/). The database was created at the Botanic Laboratory of the University of Molise. It contains 1116 alimurgic entities or WEPs of the Italian flora that have been detected through the consultation of over 330 texts (mainly books and scientific publications) published from 1918 to 2024. These entities correspond to 13.1 percent of the Italian flora [1,2].

Such a high number of WEPs is motivated by the integration of geographical, biological, sociological, and anthropological factors. The Italian territory is characterized by a high level of specific diversity resulting from the complex history of its flora and its complex climate, lithology, and geomorphology. This is the foundation of Italy’s gastronomic geography, extraordinarily rich in culinary variations consistent with the physical characteristics of its territories, the structure of agricultural activities, and the succession of historical, cultural, and socio-demographic events. Regarding the latter two aspects, the impact of the cultures of different ethnic groups, often limited to minority communities present primarily in the regions of southern Italy (e.g., Puglia, Molise, Calabria), is cited as an example [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

Currently, WEPs represent an interesting vector from an anthropological and sociological perspective because they allow us to keep alive a thousand-year-old tradition that, as long as it remains functional, will have a chance of surviving.

The use of WEPs, moreover, is also a way to reformulate some production paradigms in the agricultural world. Agriculture is currently considered the main cause of biodiversity loss [11,12,13] due to the huge amount of energy inputs required (e.g., water, fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides). WEPs maintain a high intrinsic genetic diversity that allows their effective adaptation to a wide variety of habitats [14] and therefore can provide an important contribution to the significant increase in agricultural production, a consequence of the expected growth of the human population. WEPs can therefore increase the availability to humanity of food, vitamins, and nutrients from sustainable sources, also including herbal preparations, traditional medicine formulas or new biopharmaceuticals [15,16].

The widespread global interest in WEPs has boosted the development of several databases that facilitate the effective synthesis of the countless published texts on the topic and the wider dissemination of the use of these plants. For public consultation, several WEP-specific databases have been created and placed online, varying in geographical scope (nation, continent, world). A comprehensive list of these online sites is provided in Table 1. The content of these databases is highly heterogeneous, and the fields of information provided are diverse.

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of relevant WEP online databases with the AlimurgITA online database. Name = Sitename and link; Lang. = language used; Scale = geographical scale of the information provided (Cont. = continental; Nat = national; World = worldwide); TR = website update interval (first date/last date); NT = number of taxa; Search = modes of searching the database; Inf. = information on taxa provided in the database (Sci = scientific name; Syn. = synonyms, F = Family, Com. = common and dialectal names, U = type of use, P = parts used, C = cultivation tips); Ref./L = presence of bibliographical references in the database (Yes/No) or links to external pages (Y/N); WEPs = database that contains only WEPs or not (Yes/No).

In Italy, to date, no alimurgic database has been produced. The only attempts can be traced back to the archives of the CET (Centro Etnobotanico Toscano) of the University of Pisa [17,18,19] and an ethnobotanical database for the Liguria region [20], whose initial purpose was to serve as a regional and national reference point for the dissemination of information on ethnobotany. Unfortunately, these databases are not available for consultation by the general public.

AlimurgITA was created to disseminate knowledge already available in the literature, both scientific and humanistic, not only available and usable over the Internet but also creating relationships between different kinds of data, supporting other investigations, and integrating other knowledge collected in other databases [21].

The “FuD WE PIC” project (Functional and biological Diversity and habitat assessment of Wild Edible Plants in Italy under different Climate and land-use change scenarios) fits into this context. The project is specifically committed to addressing the contribution of land-use, landscape patterns (fragmentation and heterogeneity), and climatic variables to the preservation of WEPs and related ecosystem services under a multidisciplinary framework involving Bioclimatology, Ethnobotany, Landscape Ecology, and Vegetation Ecology.

2. Data Description and Use of the Database

2.1. The Taxon Page

The main point of interest of the AlimurgIta database is the information collected on the 1116 alimurgical entities.

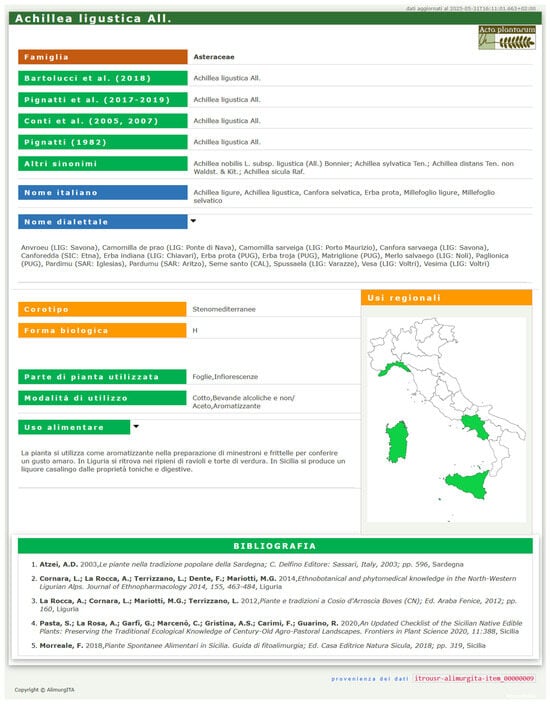

For each registered WEP, the following information is available to those consulting the entity of interest page (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

AlimurgITA online database: a screenshot of the page corresponding to the species Achillea ligustica All.

- Current scientific plant name according to the Portale della Flora d’Italia–Portal to the flora of Italy 2024.2 [22].

- Link to the taxon page on the site Acta Plantarum [21].

- “Famiglia” (Family) according to the Portale della Flora d’Italia–Portal to the flora of Italy 2024.2 [22].

- “Bartolucci et al. (2018)” (scientific plant name according to Bartolucci et al. [23]).

- “Pignatti et al. (2017–2019)” (scientific plant name present in the most recent edition of Flora of Italy [24]).

- “Conti et al. (2005, 2007)” (scientific plant name present in the checklist of the Italian vascular flora [25] and its first update [26]).

- “Pignatti (1982)” (scientific plant name found in the first Flora of Italy by Pignatti [27]);

- “Altri sinonimi” (other scientific plant names synonyms).

- “Nome italiano” (common name in Italian [21,22,24]). In this section, the names of Italian administrative regions are abbreviated as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The 20 administrative regions of Italy and their abbreviations: Valle d’Aosta (VDA), Piemonte (PIE), Lombardia (LOM), Trentino-Alto Adige (TAA), Veneto (VEN), Friuli-Venezia Giulia (FVG), Liguria (LIG), Emilia Romagna (EMR), Toscana (TOS), Umbria (UMB), Marche (MAR), Abruzzo (ABR), Lazio (LAZ), Campania (CAM), Molise (MOL), Puglia (PUG), Basilicata (BAS), Calabria (CAL), Sicilia (SIC), Sardegna (SAR).

Figure 2. The 20 administrative regions of Italy and their abbreviations: Valle d’Aosta (VDA), Piemonte (PIE), Lombardia (LOM), Trentino-Alto Adige (TAA), Veneto (VEN), Friuli-Venezia Giulia (FVG), Liguria (LIG), Emilia Romagna (EMR), Toscana (TOS), Umbria (UMB), Marche (MAR), Abruzzo (ABR), Lazio (LAZ), Campania (CAM), Molise (MOL), Puglia (PUG), Basilicata (BAS), Calabria (CAL), Sicilia (SIC), Sardegna (SAR). - “Nome dialettale” (vulgar/common names in the dialects of the 20 Italian administrative regions, mainly according to Penzig [28,29]).

- “Corotipo” (chorotype from Pignatti et al. [24]).

- “Forma biologica” (life form sensu Raunkiaer, from Pignatti et al. [24]).

- “Uso regionale” (map of the Italian administrative regions for which at least an edible use of the entity has been recorded).

- “Parte di pianta utilizzata” (part used; for a list and description of the categories used, see Paura et al. [30]).

- “Modalità di utilizzo” (method of use, for a list and description of the categories used, see Paura et al. [30]).

- “Uso alimentare” (description of use, not always available).

- “Bibliografia” (list of bibliographic references related to the entity among the 331 texts used to collect information for building the AlimurgITA database).

2.2. AlimurgITA Home Page

The “AlimurgITA–Il portale delle piante alimurgiche italiane” online database (see the following Figure 2) collects 1116 records of WEPs (species and subspecies). Among the plant entities, only vascular plants have been considered, excluding from the collection of the alimurgic species, fungi, and lichens that have received little consideration in most ethnobotanical texts.

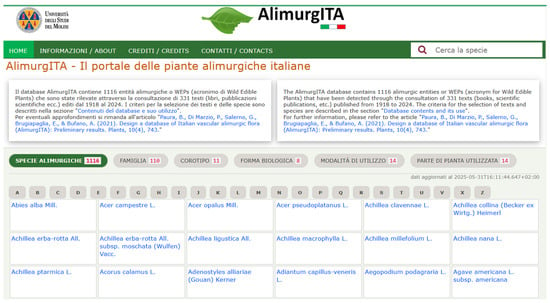

The home page of the site (Figure 3) is divided into the following information sections:

Figure 3.

AlimurgITA online database: a screenshot of the home page (the taxa list is partially shown).

- A brief description of the website in Italian and English.

- Six buttons corresponding to the possibilities of searching information by “Specie alimurgiche” (taxa), ”Famiglia” (Family), “Corotipo” (Chorotype), “Forma biologica” (Life Form), “Modalità di utilizzo” (Methods of use), and “Parte di pianta utilizzata” (Part used), each button showing the total number of corresponding records: 1116 taxa, 110 Families, 11 Chorotypes, 8 Life forms, 14 Methods of use, and 14 Part used (see Figure 4).

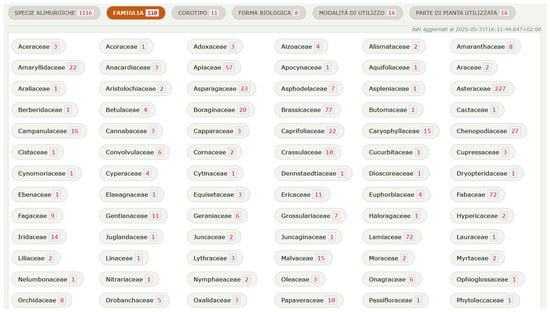

Figure 4. Screenshot of the “Famiglia” (Family) page (the buttons contain the corresponding number of records for each Family). Families are listed in alphabetical order (left to right and top to bottom) on the page for easy searching.

Figure 4. Screenshot of the “Famiglia” (Family) page (the buttons contain the corresponding number of records for each Family). Families are listed in alphabetical order (left to right and top to bottom) on the page for easy searching. - Twenty-four buttons for alphabetically searching the entities recorded (see Figure 5, which provides an example of the letter B).

Figure 5. AlimurgITA online database: a screenshot of the page, resulting from the B letter filter: in the upper right corner, the number 44 states the corresponding number of records, titled by taxon names starting with the letter B.

Figure 5. AlimurgITA online database: a screenshot of the page, resulting from the B letter filter: in the upper right corner, the number 44 states the corresponding number of records, titled by taxon names starting with the letter B.

The information is primarily written in Italian, apart from the scientific names of the entities (Latin binomial and patronymic). Other English texts are the AlimurgITA introduction of the HOME page and the other informative sections of the top menu: (1) Informazioni/About, (2) Crediti/Credits, (3) Contatti/Contacts.

The user can reach descriptive pages of the entities of interest in two ways: (1) by typing part of the entity name in the search button on the right upper part of the HOME page, or (2) by browsing the table of URL links, named with the taxon and alphabetically ordered from the top of the page downward (Figure 3).

2.3. Browsing by Alphabetic Filters

Figure 4 shows the twenty-four buttons that alphabetically filter the search of taxon names. The blue-highlighted “B” letter at the top of the figure means that the “B” button has been pushed, activating the corresponding page list of the taxons starting with the “B” letter.

2.4. Browsing by Semantic Filters

The semantic search for taxa is structured around five classification types, each gathering taxon data in a specific topic class reflecting different multipurpose perspectives.

Thus, the interface presents the first button “Specie Alimurgiche” as the main button for returning to the main taxa list, and the five buttons with the following sequence: “Famiglia” Family, “Corotipo” Chorotype, “Forma biologica” Life form, “Modalità di utilizzo” Methods of use, and “Parte di pianta utilizzata” Part used.

Figure 4 shows the list of taxon families retrieved by pushing the “Famiglia” (Family) button: for each Family, the corresponding number of matching taxa is also displayed (Figure 4).

The user can choose the specific family by clicking on the corresponding button, which shows the list of entities belonging to that family. Figure 6 shows the resulting list of entities belonging to the Crassulaceae family class.

Figure 6.

Screenshot of the Family Crassulaceae page. Taxa are listed in alphabetical order (left to right and top to bottom) on the page for easy searching and linked to the corresponding taxon page.

Analogously, Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the results of taxa semantic filtering executed by “Corotipo” (Chorotype).

Figure 7.

Screenshot of the “Corotipo” (Chorotype) page (the buttons contain the corresponding number of records for each chorotype). Chorotypes are listed in alphabetical order (left to right and top to bottom) on the page for easy searching.

Figure 8.

Screenshot of the chorotype “Stenomediterranee” (Steno-Mediterranean) page. Taxa are listed in alphabetical order (left to right and top to bottom) on the page for easy searching and linked to the corresponding taxon page.

2.5. Statistical Results

For statistical purposes, the successive browsing of pages that can be reached through the buttons is always accompanied by the number of records corresponding to the different categories. Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 report the frequencies and percentages for Chorotypes, Life forms, Methods of use, and Parts used.

Table 2.

Chorotypes and their abundance in the AlimurgITA database (in decreasing order of frequency).

Table 3.

Plant life forms and their abundance in the AlimurgITA database (in decreasing order of frequency).

Table 4.

Methods of use and their abundance in the AlimurgITA database (in decreasing order of frequency).

Table 5.

Parts used and their abundance in the AlimurgITA database (in decreasing order of frequency).

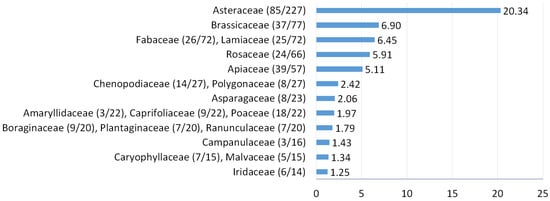

Among the 110 families, 19 comprise more than 1% of the registered entities (Figure 9). The most represented family is Asteraceae, with 227 entities belonging to 85 genera; the next, Brassicaceae, has just over a quarter as many entities as Asteraceae (77) and about half as many genera (35). In order of importance, they follow Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, Rosaceae, and Apiaceae. Finally, with percentages below 5%, we find Chenopodiaceae, Polygonaceae, Asparagaceae, Amaryllidaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Poaceae, Boraginaceae, Plantaginaceae, Ranunculaceae, Campanulaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Malvaceae, and Iridaceae.

Figure 9.

AlimurgITA online database: relative abundance of the 19 most represented families (numbers of genera and entities in brackets: genera/entities).

3. Methods

The AlimurgITA database was built to contain data relating to food uses (typology and regional distribution in Italy) and to some morphological characteristics (biological form), chorological (chorotype), and toxicological characteristics of WEPs used for feeding in Italy.

Alimurgita database lists only strictly alimurgic plants, that is, plant taxa—autochthonous or alien naturalized—considered edible in some areas of the Italian territory studied from an ethnobotanical perspective. Casual alien and archaeophyte species have not been considered alimurgic, whereas the database contains species used in both their spontaneous and cultivated states (e.g., olive, chestnut, vine, hazelnut, fig, white mulberry), even though domesticated forms are widely dominant [30].

The database does not include taxa reported by mistake, no longer recorded, absent, or doubtfully occurring according to the status defined by Acta plantarum [21] and the Portal to the Flora of Italy [22]. As regards a taxonomy perspective, some critical taxa, such as Taraxacum officinale and Rubus hirtus, have been taken into account as a group; for Portulaca oleracea and Thymus serpyllum, the choice has been made, on the contrary, to keep it as sensu lato (s.l.), because of the impossibility to refer back the records to the taxa into which it has been divided [30].

Each taxon has been associated with the part used and the methods of food preparation, using the categories listed by Guarrera [31] as modified by Paura et al. [30]. The database does not consider species used exclusively for herb teas, infusions, and decoctions, which are more often used for their medicinal properties than as beverages [32]; on the contrary, it includes species used to prepare liqueurs, which are an integral part of the meal, according to Guarrera [32].

Finally, fungi and lichens were not considered (for example, Cetraria islandica used during a famine in Veneto in 1916) [33], which are only marginally treated in most ethnobotanical texts. The data would therefore have been scarce and partial, and therefore insufficient for a comparison between plants on an ethnobotanical basis.

As regards the edible uses, the data collection was based on the selection of three types of contributions [30]:

- Monographs of authoritative or famous authors;

- Works published in international and national journals with refereeing;

- Very few cases of personal communications.

These three criteria are also associated with a reference to clearly defined territories, up to the national scale; the idea was to follow a specific ethnobotanical approach, highlighting contributions that established a close relationship between WEPs uses and popular tradition. We have expressly chosen to focus only on ‘traditional uses’, because our interest concentrated on collecting information about the use of WEPs, leaving aside—for the time being and intentionally—all ‘new’ food uses of plants recently acquired in the wake of new experimentations in the area of gastronomy and nutrition. This choice was also due to the need to contain—as much as possible—the margin for erroneous identification of taxa, which, without this a priori selection, would most likely have been higher. Attention was thus paid to redundant work, that is to say, where the same set of data had been published, by the same authors, in separate contributions for the same geographical area. Finally, scientific contributions of a methodology, conceptual, demo-anthropological, or generic nature have been excluded, where no reference was made to alimurgic species.

Owing to the significant variation in the types of data sources, an archive comprising paper sources and PDFs of the contributions that have been photocopied or made available in that format has been established in the Laboratory of Botany of the Department of Environment, Agriculture, and Food at the University of Molise in Campobasso (Molise, Italy).

4. Discussion

The AlimurgITA portal is clear, simple, and effective in its consultation; for this reason, this consultation tool will give a new impulse and a systematization to the research on the subject of WEPs. The information stored in the portal and the list of alimurgic entities can also be of considerable use for practical application purposes. Having access to some characteristics (e.g., biological forms) that contribute to defining the ecology of WEP species can be a prerequisite for their satisfactory conservation and, at the same time, provide functional data for their potential use in agriculture.

Currently, more and more attention is focused on WEPs that frequently combine organoleptic characteristics, biomass production, high nutraceutical qualities (they are sometimes called superfoods), and the possibility (and opportunity) of their cultivation with low energy inputs (e.g., use of chemical fertilizers and phytosanitary products). In the context of global change, it will be increasingly important to have crops that consume little water and understand the stock of species potentially available for each specific territory.

The AlimurgITA database’s strength lies is its ability to perform searches using alphabetical and semantic filters, allowing for easy and immediate access to basic statistics. Search tools are also planned to be enhanced in the near future. For example, it is currently not possible to search for WEP entities based on their synonyms; furthermore, the number of buttons that will allow for links to major databases dedicated to WEPs (e.g., PFAF) and to WEP autoecology (e.g., https://fudwepic.unipa.it, (accessed on 3 October 2025)) should be increased.

The authors are considering adding English translations of the database and additional information fields to the pages for alimurgic taxa, such as information on the harvesting period, toxicity, etc.

Furthermore, the site is expected to be implemented soon, updated every six months, and welcome and include new scientific publications on ethnobotanical and alimurgic themes.

The site users will be able to interact with the authors by reporting errors or suggesting changes through personal contact via email, but above all, by increasing the information on the uses still detected in the user’s investigation territory. The site’s authors will critically examine all information received.

Within the FuD WE PIC Project, the AlimurgITA entity list is being integrated with Italian vegetation graphs from the European Vegetation Archive (EVA) to pursue two main objectives: (i) to model WEP richness and identify diversity hotspots and (ii) explore the relationships between WEP diversity and their preferential habitat types.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.P. and P.D.M.; methodology, B.P. and P.D.M.; design of the database and automatic conversion of database2web, A.D.I.; validation, B.P.; data curation, P.D.M. and B.P.; writing—original draft preparation, B.P. and P.D.M.; writing—review and editing, B.P., P.D.M., C.G., and A.D.I.; funding acquisition, B.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the funds of the Ministry of University and Research, Project PNRR M4.C2.1.1; CUP: B53D23011830006 ‘Functional and biological Diversity and habitat assessment of Wild Edible Plants in Italy under different Climate and land-use change scenarios’ (FuD WE PIC).

Data Availability Statement

All the data are available at AlimurgITA–Il portale delle piante alimurgiche italiane at http://alimurgita.it/ (accessed on 3 October 2025). Dataset License: (CC-BY-NC-SA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WEP | Wild Edible Plant |

| WEPs | Wild Edible Plants |

References

- Bartolucci, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Galasso, G.; Alessandrini, A.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Bacchetta, G.; Banfi, E.; Barberis, G.; Bernardo, L.; Bouvet, D.; et al. A second update to the checklist of the vascular flora native to Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2024, 158, 219–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, G.; Conti, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Alessandrini, A.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Bacchetta, G.; Banfi, E.; Barberis, G.; Bernardo, L.; Bouvet, D.; et al. A second update to the checklist of the vascular flora alien to Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2024, 158, 297–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Quave, C.L. Functional food or food medicine? On the consumption of wild plants among Albanians and Southern italians in Lucania. In Eating and Healing: Traditional Food as Medicine; Pieroni, A., Price, L.L., Eds.; Haworth Press: Binghamton, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 101–129. [Google Scholar]

- Di Tizio, A.; Łuczaj, Ł.J.; Quave, C.L.; Redžić, S.; Pieroni, A. Traditional food and herbal uses of wild plants in the ancient South-Slavic diaspora of Mundimitar/Montemitro (Southern Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. Healing with sacred and medicinal plants in three Arbereshe Communities of Southern Italy. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Congress of Ethnobotany, Naples, Italy, 22–30 September 2001; Volume 43, p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni, A.; Nebel, S.; Quave, C.; Munz, H.; Heinrich, M. Ethnopharmacology of liakra: Traditional weedy vegetables of the Arbereshe of the Vulture area in southern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 81, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieroni, A.; Nebel, S.; Quave, C.; Heinrich, M. Ethnopharmacy of the ethnic Albanians of northern Basilicata, Italy. Fitoterapia 2002, 73, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. Traditional health care and food and medicinal plant use among historic Albanian migrants and Italians in Lucania, Southern Italy. In Traveling Cultures and Plants: The Ethnobiology and Ethnopharmacy of Human Migrations; Pieroni, A., Vandebroek, I., Eds.; Berghahn Books: Oxford, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 204–227. [Google Scholar]

- Nebel, S.; Pieroni, A.; Heinrich, M. Ta chorta: Wild edible greens used in the Graecanic area in Calabria, southern Italy. Appetite 2006, 47, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebel, S.; Heinrich, M. The Use of Wild Edible Plants in the Graecanic Area in Calabria, Southern Italy. In Ethnobotany in the New Europe: People, Health and Wild Plant Resources; Pardo-de-santayana, M., Pieroni, A., Puri, R.K., Eds.; Berghahn Books: Oxford, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 172–188. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture; Bélanger, J., Pilling, D., Eds.; FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Assessments: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES. Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Díaz, S., Settele, J., Brondízio, E.S., Ngo, H.T., Guèze, M., Agard, J., Arneth, A., Balvanera, P., Brauman, K.A., Butchart, S.H.M., et al., Eds.; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxted, N.; Kell, S.; Ford-Lloyd, B.; Dulloo, E.; Toledo, Á. Toward the systematic conservation of global crop wild relative diversity. Crop Sci. 2012, 52, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandebroek, I.; Pieroni, A.; Stepp, J.R.; Hanazaki, N.; Ladio, A.; Alves, R.R.N.; Picking, D.; Delgoda, R.; Maroyi, A.; van Andel, T.; et al. Reshaping the future of ethnobiology research after the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19—The Role of Wild Plants in Health Treatment and Why Sustainability of Their Trade Matters. Available online: https://www.traffic.org/news/covid-19-the-role-of-wild-plants-in-health-treatment/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Uncini Manganelli, R.E.; Tomei, P.E. L’etnobotanica in Toscana: Stato attuale e prospettive future. Inf. Bot. Ital. 1999, 31, 164–165. [Google Scholar]

- Tomei, P.E.; Uncini Manganelli, R.E.; Trimarchi, S.; Camangi, F. Ethnopharmacobotany in Italy: State of knowledge and prospect in the future. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress of Ethnobotany (ICEB 2005), Istanbul, Turkey, 21–26 August 2005; Ege Yayinlari: Istanbul, Turkey, 2006; pp. 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Camangi, F.; Stefani, A.; Sebastiani, L. Etnobotanica in val di Vara. L’uso delle Piante Nella Tradizione Popolare; Biolabs Libri: Pisa, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini, M.; Bisio, A.; Minuto, L.; Profumo, P.; Ruggiero, C. Strutturazione della conoscenza per un database di etnobotanica ligure. Inf. Bot. Ital. 1999, 31, 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Acta Plantarum, from 2007 on. Available online: https://www.actaplantarum.org/home/utilities.php (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Portale della Flora d’Italia/Portal to the Flora of Italy 2024.2. Available online: http://dryades.units.it/floritaly (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Bartolucci, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Galasso, G.; Albano, A.; Alessandrini, A.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Astuti, G.; Bacchetta, G.; Ballelli, S.; Banfi, E.; et al. An updated checklist of the vascular flora native to Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2018, 152, 179–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatti, S.; Guarino, R.; La Rosa, M. Flora d’Italia, 2nd ed.; Edagricole: Bologna, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, F.; Abbate, G.; Alessandrini, A.; Blasi, C. An Annotated Checklist of the Italian Vascular Flora; Palombi Editori: Roma, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, F.; Alessandrini, A.; Bacchetta, G.; Banfi, E.; Barberis, G.; Bartolucci, F.; Bernardo, L.; Bonacquisti, S.; Bouvet, D.; Bovio, M.; et al. Integrazioni alla checklist della flora vascolare italiana. Nat. Vicentina 2007, 10, 5–74. [Google Scholar]

- Pignatti, S. Flora d’Italia; Edagricole: Bologna, Italy, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Penzig, O. Flora Popolare Italiana. Raccolta dei Nomi Dialettali delle Principali Piante Indigene e Coltivate in Italia; Orto Botanico della Regia Università: Genova, Italy, 1924; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Penzig, O. Flora Popolare Italiana. Raccolta dei Nomi Dialettali delle Principali Piante Indigene e Coltivate in Italia; Orto Botanico della Regia Università: Genova, Italy, 1924; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Paura, B.; Di Marzio, P.; Salerno, G.; Brugiapaglia, E.; Bufano, A. Design a Database of Italian Vascular Alimurgic Flora (AlimurgITA): Preliminary Results. Plants 2021, 10, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarrera, P.M. Usi e Tradizioni della Flora Italiana. Medicina, Popolare ed Etnobotanica; Aracne Editrice: Roma, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ghirardini, M.P.; Carli, M.; Del Vecchio, N.; Rovati, A.; Cova, O.; Valigi, F.; Agnetti, G.; Macconi, M.; Adamo, D.; Traina, M.; et al. The importance of a taste. A comparative study on wild food plant consumption in twenty-one local communities in Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampiva, F. Erbario Veneto: Cultura, Usi e Tradizioni delle Piante e delle Erbe Più Note; Egida: Vicenza, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).