Abstract

This article presents articulatory–kinematic data on preboundary lengthening (Intonational Phrase-final lengthening) from the productions of ten native speakers of American English—a relatively rare class of phonetic data compared with the more widely available acoustic data. The dataset includes three trisyllabic nonce words (bábaba, babába, bababá), each designed to manipulate the location of lexical stress. These were produced under prosodic conditions that varied in boundary position and focus-induced phrasal prominence, enabling analysis of how preboundary lengthening is distributed across words with different lexical stress locations and how it interacts with prosodic prominence. Articulatory data were collected using electromagnetic articulography (EMA, Carstens AG200), providing kinematic measurements such as movement duration, peak velocity, and displacement of articulatory gestures. The accompanying files allow examination of individual speaker variation in these measures as modulated by prosodic structure, including boundary and prominence effects. While theoretical findings have been reported in a previous study, the full dataset, including detailed descriptions of individual speaker patterns, is made available here. By making these less commonly available articulatory data publicly available, we aim to promote broad reuse and support further research in prosody, articulatory phonetics, and speech production.

Dataset License: CC BY 4.0

1. Summary

This dataset consists of CSV files documenting articulatory measures of preboundary lengthening (Intonational Phrase-final lengthening) in American English [], collected from ten native speakers. The files, together with the full articulatory dataset, are accessible through OSF [10.17605/OSF.IO/V9T6X]. The materials include three trisyllabic nonce words that vary in lexical stress placement, each embedded within four carrier sentences.

Each sentence was produced four times by each speaker. Articulatory and acoustic data were obtained under systematically varied prosodic contexts, crossing two boundary positions (IP-final, Wd-final) with two pitch accent conditions (Accented, Unaccented). (As explained in §3.2, pitch accent was induced by placing contrastive focus on the target.) This design enables examination of how prosodic structure shapes preboundary lengthening as a function of lexical stress location and phrasal pitch accent status across speakers while holding the segmental context constant across conditions—a constraint that necessitated the use of nonce words.

Lip Aperture—defined as the Euclidean distance between the upper and lower lips [,]—was used to derive movement profiles of lip opening and closing, which is closely tied to the timing and magnitude of the underlying vowel (opening) and consonant (closing) gestures. For each syllable, two temporal indices of preboundary lengthening were extracted: the duration of lip closure and the duration of lip opening. In addition, the CSV files report peak velocity and displacement for both closing and opening movements, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of the kinematic properties associated with preboundary lengthening.

This dataset offers a valuable resource, relatively rare compared with the acoustic data, for researchers exploring articulatory–phonetic variation in preboundary lengthening under different prosodic conditions in American English. It is especially well-suited for investigating how prosodic structure shapes articulatory realization, beyond what is typically captured by suprasegmental (acoustic) measures. While the original study [] primarily reports aggregate articulatory duration across the full trisyllabic target word and kinematics (i.e., peak velocity and displacement) for the phrase-final gesture (i.e., the final syllable), it does not report individual-difference analyses, nor does it examine peak velocity or displacement for pre-final gestures (i.e., the penultimate and antepenultimate syllables). The present dataset, however, includes articulatory measurements for all syllables by individual speakers. By including these additional dimensions, the present dataset offers opportunities to analyze speaker-specific strategies in encoding prosodic boundaries. It also provides useful data in examining the interaction between boundary and prominence, both in terms of lexical-level prominence (i.e., lexical stress) and phrasal-level prominence (i.e., pitch accent). We acknowledge that the current dataset includes only a small number of native American English speakers, and thus the findings should not be generalized across dialects or broader sociolinguistic groups. This limitation also renders any statistical results reported here necessarily tentative. Nonetheless, given the rarity of articulatory data of this kind, we hope that making this dataset publicly available will provide a valuable baseline from which more extensive future studies can develop. In short, researchers interested in questions not covered in []—or in extending its analyses—now have full access to the underlying articulatory records needed to examine these issues in detail.

2. Data Description

2.1. CSV File: Articulatory Measurements

A CSV file containing articulatory measurements is provided. Table 1 presents a sample from the file, which contains duration, peak velocity, and displacement of articulatory movements, measured for each individual speaker. Each row in the CSV file corresponds to a single token produced under specific experimental conditions. Descriptions of each column, as exemplified in Table 1, are provided below:

Table 1.

Sample from the CSV file for illustrative purposes. The table shows articulatory measurements, as produced by a female speaker of American English (speaker SF01).

- Speaker: A unique speaker code identifying each participant. “S” stands for speaker and the second letter indicates gender (“F” for female, “M” for male), followed by two digits (01–10) randomly assigned to each speaker. The dataset includes 10 speakers.

- Gender: The gender of the speaker (“F” for female, “M” for male).

- Boundary: The prosodic boundary condition under which the target word was produced. “IP” indicates Intonational Phrase boundaries: for IP-final, it occurred phrase-finally (at the end of an IP). Wd-final refers to phrase-medial (word-level) positions.

- Accent: The pitch accent condition applied to the target word. “Acc” indicates that the target word was produced with a pitch accent under contrastive focus, while “Una” indicates that the pitch accent was placed on another word in the utterance.

- Stress: The lexical stress location of the target word. “Final” indicates that the lexical stress of the target word fell on the final (third) syllable, “Penult” on the penultimate (second) syllable, and “Antepenult” on the antepenultimate (first) syllable.

- Repetition: The repetition number for a given condition, labeled from r1 to r4, where “r” stands for repetition.

- Cxclos_dur: The movement duration (in ms) of the lip closing movement in the x-th syllable (e.g., “C1clos_dur” refers to the lip closing movement duration of the first syllable; “C2clos_dur” to the second syllable; “C3clos_dur” to the third syllable).

- Cxopen_dur: The movement duration (in ms) of the lip opening movement in the x-th syllable (e.g., “C1open_dur” refers to the lip opening movement duration of the first syllable; “C2open_dur” to the second syllable; “C3open_dur” to the third syllable).

- Cxclos_pkvel: The peak velocity (in cm/s) of the lip closing movement in the x-th syllable (e.g., “C1clos_pkvel” refers to the lip closing movement peak velocity of the first syllable; “C2clos_pkvel” to the second syllable; “C3clos_pkvel” to the third syllable).

- Cxopen_pkvel: The peak velocity (in cm/s) of the lip opening movement in the x-th syllable (e.g., “C1open_pkvel” refers to the lip opening movement peak velocity of the first syllable; “C2open_pkvel” to the second syllable; “C3open_pkvel” to the third syllable).

- Cxclos_displ: The displacement (in mm) of the lip closing movement in the x-th syllable (e.g., “C1clos_displ” refers to the lip closing movement displacement of the first syllable; “C2clos_displ” to the second syllable; “C3clos_displ” to the third syllable).

- Cxopen_displ: The displacement (in mm) of the lip opening movement in the x-th syllable (e.g., “C1open_displ” refers to the lip opening movement displacement of the first syllable; “C2open_displ” to the second syllable; “C3open_displ” to the third syllable).

2.2. General Figures

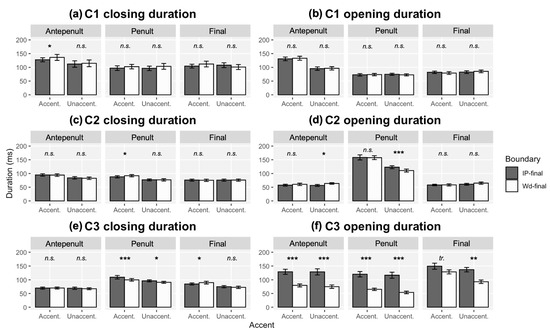

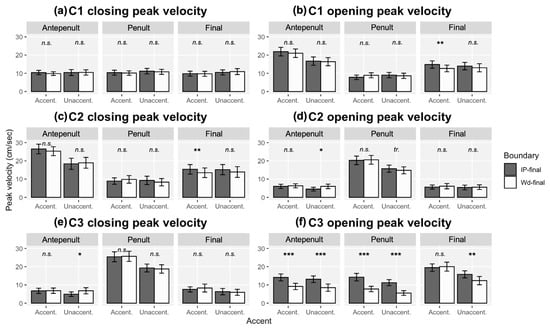

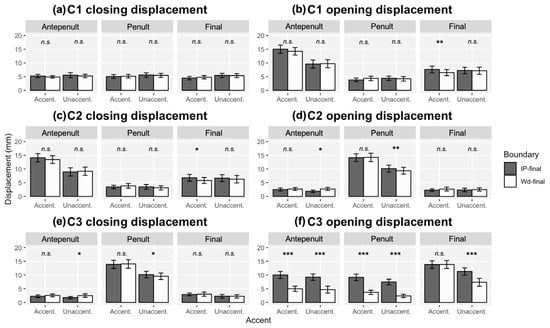

Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 present data from ten native American English speakers. The figures display articulatory movement duration (Figure 1), peak velocity (Figure 2), and displacement values (Figure 3) as a function of boundary (IP-final, Wd-final) and accent conditions (Accented, Unaccented), plotted separately for each lexical stress position (Antepenult, Penult, Final).

Figure 1.

Bar plots with 95% confidence intervals for articulatory movement duration (in ms) by boundary, accent, and lexical stress conditions during the measured interval: (a) C1 lip closing, (b) C1 lip opening, (c) C2 lip closing, (d) C2 lip opening, (e) C3 lip closing, and (f) C3 lip opening. Asterisks (*) indicate results of pairwise comparisons with the emmeans package [,] based on linear mixed-effects models fitted with the lme4 package [], with Boundary × Accent × Stress as fixed effects and speaker as a random factor in R []. *** = p < 0.001, ** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05, tr. = 0.05 < p < 0.06, n.s. = p > 0.06.

Figure 2.

Bar plots with 95% confidence intervals for movement peak velocity (in cm/s) by boundary, accent, and lexical stress conditions during the measured interval: (a) C1 lip closing, (b) C1 lip opening, (c) C2 lip closing, (d) C2 lip opening, (e) C3 lip closing, and (f) C3 lip opening. Asterisks (*) indicate results of pairwise comparisons with the emmeans package [,] based on linear mixed-effects models fitted with the lme4 package [], with Boundary × Accent × Stress as fixed effects and speaker as a random factor in R []. *** = p < 0.001, ** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05, tr. = 0.05 < p < 0.06, n.s. = p > 0.06.

Figure 3.

Bar plots with 95% confidence intervals for movement displacement (in mm) by boundary, accent, and lexical stress conditions during the measured interval: (a) C1 lip closing, (b) C1 lip opening, (c) C2 lip closing, (d) C2 lip opening, (e) C3 lip closing, and (f) C3 lip opening. Asterisks (*) indicate results of pairwise comparisons with the emmeans package [,] based on linear mixed-effects models fitted with the lme4 package [], with Boundary × Accent × Stress as fixed effects and speaker as a random factor in R []. *** = p < 0.001, ** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05, n.s. = p > 0.06.

2.3. Individual Speaker Figures

Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 present individual data from ten native American English speakers. The figures display articulatory movement duration, peak velocity, and displacement values as a function of boundary (IP-final, Wd-final), accent (Accented, Unaccented), and lexical stress (Antepenult, Penult, Final) conditions, plotted separately for each speaker.

Figure 4.

Plots with standard error intervals for ten individual speakers showing movement duration in ms by boundary, accent, and lexical stress conditions during the measured interval: (a) C1 lip closing, (b) C1 lip opening, (c) C2 lip closing, (d) C2 lip opening, (e) C3 lip closing, and (f) C3 lip opening. “F” and “M” in the speaker code stand for female and male, respectively.

Figure 5.

Plots with standard error intervals for ten individual speakers showing movement peak velocity in cm/s by boundary, accent, and lexical stress conditions during the measured interval: (a) C1 lip closing, (b) C1 lip opening, (c) C2 lip closing, (d) C2 lip opening, (e) C3 lip closing, and (f) C3 lip opening. “F” and “M” in the speaker code stand for female and male, respectively.

Figure 6.

Plots with standard error intervals for ten individual speakers showing movement displacement in mm by boundary, accent, and lexical stress conditions during the measured interval: (a) C1 lip closing, (b) C1 lip opening, (c) C2 lip closing, (d) C2 lip opening, (e) C3 lip closing, and (f) C3 lip opening. “F” and “M” in the speaker code stand for female and male, respectively.

- Figure 4 shows the movement duration (in ms) for each of the 10 speakers, plotted by boundary, accent, and lexical stress conditions.

- Figure 5 shows the movement peak velocity (in cm/s) for each of the 10 speakers, plotted by boundary, accent, and lexical stress conditions.

- Figure 6 shows the movement displacement (in mm) for each of the 10 speakers, plotted by boundary, accent, and lexical stress conditions.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

Ten native English speakers (5 female, 5 male) participated in this articulatory study. All participants were native speakers of American English in their twenties or thirties, visiting South Korea as exchange students, English teachers or employees at the time of recording. The participants were not informed of the specific research questions and purpose of the study, in order to avoid bias in their responses, and were paid for their participation.

3.2. Speech Materials

Three trisyllabic nonce words (e.g., bábaba, babába, bababá), which consisted of bilabial stop/b/and low vowel/ɑ/, differing only in the location of lexical stress. The vowel was realized as [ɑ] under stress, and [ə] (or auditory judged to be reduced) when unstressed. Nonce words were used to hold the segmental context constant across stress positions, and to ensure a clean link between articulatory measures (e.g., lip aperture for/b–ɑ/sequences) and prosodic manipulations (stress, pitch accent, boundary).

The target words were embedded in carrier sentences serving as responses to given questions within a semi-spontaneous discourse context, as illustrated in Table 2. The mini-discourses were designed to elicit different prosodic boundaries and accent types. Table 2 provides example carrier sentences in English, where the utterance labeled “B” contains the target word bábaba with lexical stress on the initial syllable.

Table 2.

Example sentences with target word bábaba. Target words are underlined, and accented words are in bold.

For example, the IP-final accented condition was elicited with a question such as, “Did you say Mr. Mámama?”, prompting the response, “No, I said Mr. Bábaba, didn’t I?” In this context, bábaba is the focused item, contrasted with mámama, and appears at the end of the IP. In contrast, the Wd-initial (i.e., phrase-medial) unaccented condition was elicited with a question like, “Did you say Mrs. Bábaba said it?”, followed by the response, “No, I said Mr. Bábaba said it.” Here, the contrast lies between Mrs. and Mr., so bábaba is not accented and occurs phrase-medially. Accordingly, the pitch-accented condition was elicited by placing contrastive focus on the target, and the unaccented condition by placing contrastive focus immediately before it, rendering the target post-focal.

3.3. Procedures

On the day prior to the experiment, participants completed a 30–60 min training session. The target words were introduced as surnames (e.g., Mr. Bababa) to facilitate practice of the intended lexical stress patterns.

Articulatory data were collected using Electromagnetic Midsagittal Articulography (Carstens AG200), and acoustic data were simultaneously recorded with a SHURE VP88 microphone at a sampling rate of 16 kHz in a sound-attenuated booth at Hanyang Institute for Phonetics and Cognitive Sciences of Language. Sensors were attached to articulators, including the upper and lower lips, and the data were processed following standard procedures (see []). During the experiment, the mini-discourse sentences were displayed on a computer screen. A prerecorded prompt sentence produced as Speaker A was played through a loudspeaker, and participants responded in the role of Speaker B. Test sentences were presented in randomized order across four repetition blocks. In total, 480 sentences were collected [3 lexical stress positions (bábaba, babába, bababá) × 2 boundary conditions (IP-final, Wd-final) × 2 accent types (accented, unaccented) × 4 repetitions × 10 speakers]. The prosodic realizations of the sentences were subsequently examined by the authors (trained prosodic transcribers), and 13 tokens were excluded due to unintended boundary or pitch accent patterns.

3.4. Measurements

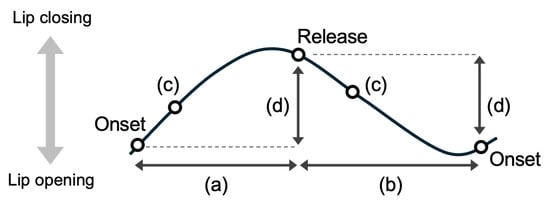

Movements of the lips were quantified using the Euclidean distance between sensors placed on the upper and lower lips, commonly referred to as Lip Aperture [,]. Specifically, for each frame, Lip Aperture (LA) was calculated as where and represent the horizontal and vertical coordinates of the upper and lower lip sensors. Figure 7 provides a summary of the kinematic measures. For each syllable, two primary temporal metrics related to preboundary lengthening were extracted: lip closing duration (Figure 7a), which encompasses both the time taken for the lips to close and the period of full closure until constriction release, and lip opening duration (Figure 7b), which includes the release phase and the lip opening plateau leading up to the next closing movement. In addition, peak velocity (Figure 7c) and displacement (Figure 7d) were calculated for both closing and opening motions to characterize the overall kinematics potentially associated with preboundary lengthening. The onset and target of each lip movement were defined as the time points where velocity reached 20% of its peak following or preceding the zero-crossing, respectively. Although this 20% threshold can slightly vary depending on the actual peak velocity of each movement, prior experience with kinematic data suggests that such variation is minimal. This consistency is also reflected in earlier studies, which have commonly applied the same threshold across different experimental conditions, as was done here.

Figure 7.

Schematized lip closing and opening movements with kinematic measures: (a) lip closing duration; (b) lip opening duration; (c) peak velocity; and (d) displacement.

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and was approved by the ethics committee of the Hanyang Institute for Phonetics and Cognitive Sciences of Language.

4. Findings and Potential Implications

This section outlines key findings from the original research article [], discusses potential implications of the current data, and suggests future research directions based on the current dataset.

4.1. Findings and Potential Implications for Preboundary Lengthening in American English

- In American English, preboundary lengthening on the phrase-final articulatory movement is modulated by the degree of prominence, i.e., the less prominent, the more preboundary lengthening. Preboundary lengthening is attracted to the penultimate stressed syllable but only when the word received no pitch accent whereas the antepenultimate stressed syllable showed no such attraction. Kinematically, preboundary lengthening is accompanied by a larger movement along with an increase in peak velocity, showing a kind of boundary-related articulatory strengthening.

- Further inspection of individual speaker differences as illustrated in Figure 4 reveals that while all 10 speakers consistently lengthen the phrase-final C3 opening duration in Unaccented condition, only 6 out of 10 speakers do so in the Accented condition. The remaining four either show no preboundary lengthening or show shortening. This individual difference helps explain the results reported in [], where preboundary lengthening in the Accented condition was not statistically significant. These individual differences suggest that when another factor drives hyperarticulation of the phrase-final (C3) opening gesture—here, focus-induced prominence—speakers differ in how they control the kinematics of the final-syllable closure–opening cycle: some preserve boundary-driven lengthening at C3, reinforcing the kinematic signature of finality, while others prioritize prominence cues and effectively trade off boundary signaling, yielding little or no preboundary lengthening in the final consonantal gesture.

- Moreover, an attraction pattern (e.g., whether the IP boundary influences the penultimate syllable’s C2 opening duration) was observed in 6 out of 10 speakers, most clearly in the Unaccented condition. This suggests that boundary-driven adjustments to pre-final gestures are optional when they are not the primary cue to prosodic structure, yielding substantial inter-speaker variation.

Taken together, these implications illustrate only part of what can be drawn from the provided dataset. From an articulatory perspective, a key finding is that preboundary lengthening in American English is shaped by prosodic prominence: phrase-final movements lengthen more when the word is unaccented, and this lengthening is often attracted to the penultimate stressed syllable. Importantly, the results also reveal evidence of boundary-related articulatory strengthening, with lengthening accompanied by increased peak velocity and larger movement amplitude. At the same time, an examination of individual differences underscores that such patterns may also be further differentiated at the level of individual speakers’ articulatory modulations (cf. []). While the group as a whole shows systematic prosodic fine-tuning, individual speakers diverge in whether and how they implement lengthening under accented conditions or exhibit attraction effects on earlier syllables. This suggests that the articulatory mechanisms through which prosodic boundaries are realized may vary across speakers, with greater freedom when the controlled parameter is not the primary cue to boundary strengthening. It is noteworthy that, for the purposes of data description, the present dataset focuses on articulatory patterns at the level of individual speakers rather than offering theoretically informed interpretations based on aggregated data. Future studies employing statistical modeling will be necessary to determine whether the observed individual differences reflect systematic prosodic strategies or speaker-specific idiosyncrasies. Such work, in turn, would shed light on how community-wide patterns interact with speaker-specific strategies in the encoding of prosodic structure. In turn, this invites further work on how community-wide patterns interact with speaker-specific strategies in encoding prosodic structure.

4.2. Further Implications

While the previous study [] primarily focused on the durational effect of preboundary lengthening and kinematics of the phrase-final articulatory movement, the current dataset may also serve as a valuable baseline for future research, offering opportunities for extended analyses in areas including, but not limited to, the following:

- Kinematics of prosodic modulation: The dataset includes articulatory kinematic measures—movement duration, peak velocity, and displacement—that allow detailed analyses of how prosodic modulation shapes the dynamics of speech gestures. These measures make it possible to examine how articulatory movements are scaled and timed across different prosodic conditions, such as phrase-final versus phrase-medial positions and accented versus unaccented contexts, providing insight into the temporal and spatial adjustments of articulatory gestures under prosodic modulation. Such analyses can further reveal whether kinematic parameters are systematically enhanced in response to prosodic strengthening or boundary effects, and, importantly, how these adjustments vary across individual speakers, thereby contributing to our understanding of the articulatory basis of prosodic structure.

- Individual variability in prosodic encoding: The dataset is appropriate for investigating speaker-specific variation in the prosodic encoding of preboundary lengthening in American English. It enables analyses of how individual speakers differ in the extent to which preboundary lengthening is conditioned by the presence versus absence of pitch accent and by the location of lexical stress within the word. Crucially, the design incorporates multiple prosodic conditions, allowing for within-speaker comparisons of how boundary-related articulatory adjustments interact with prominence at both the phrasal and lexical levels. This provides opportunities to examine whether preboundary lengthening reflects a uniform prosodic strategy or whether speakers employ distinct encoding patterns shaped by their individual use of prominence cues—and, crucially, how those strategies track the relative primacy of specific phonetic cues to prosodic structure. Overall, the dataset offers a robust empirical foundation for understanding how prosodic structure modulates articulation and how such effects vary across speakers in systematic yet individually differentiated ways.

- Sociophonetic variation (i.e., gender-related differences): The dataset also provides an opportunity to examine sociophonetic dimensions of preboundary lengthening, particularly gender-related differences in its realization and interaction with prosodic structure. For example, male and female speakers may differ in the magnitude, temporal distribution, or consistency of lengthening, especially as conditioned by pitch accent or lexical stress position. These questions, unaddressed in previous publications, can be pursued with the dataset accompanying this data article, opening a valuable avenue for future research on how social factors intersect with prosodic structure to shape fine-grained articulatory variation in American English.

5. Conclusions

This data descriptor presents a collection of articulatory–kinematic measurements—relatively rare compared to acoustic datasets—examining how prosodic boundary modulation varies with phrasal and lexical prominence in productions by native speakers of American English (available via OSF: [10.17605/OSF.IO/V9T6X]). The materials were elicited under systematically varied prosodic conditions—specifically, different boundary positions (Intonational Phrase-final, medial), lexical stress locations (Antepenultimate, Penultimate, Final), and focus-induced accent conditions (Accented, Unaccented)—enabling detailed analysis of how prosodic structure conditions articulatory realization. While a prior publication based on this dataset [] reported group-level findings, the present release includes full individual-speaker records and extends coverage to pre-final gestures, substantially widening the opportunities for future research.

A key strength of the dataset lies in its prosodic design and per-speaker detail, enabling comparisons of boundary and prominence within and across speakers. With the full set of measured articulatory values and accompanying articulatory data, this dataset enables detailed investigation of how both phrasal-level prominence (focus-induced pitch accent) and lexical-level prominence (stress placement within the target word) influence phrase-final lengthening.

More broadly, the inclusion of individual speaker data is expected to facilitate further exploration into inter-speaker variability—an increasingly central question in phonetic and phonological research. With the provided data, researchers can examine how American English speakers differ in encoding prosodic information through preboundary lengthening patterns, how this variation is modulated by prominence, and how the relative primacy of individual cues shapes these patterns. As such, by making these data publicly available, we aim to promote broad reuse and stimulate further research at the intersection of prosody, articulatory phonetics, and speech production—ultimately advancing our understanding of how phonetic patterns emerge and vary across languages and individual speakers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J., S.K. and T.C.; methodology, J.J., S.K. and T.C.; software, J.J.; validation, J.J., S.K. and T.C.; formal analysis, J.J.; investigation, J.J., S.K. and T.C.; resources, J.J., S.K. and T.C.; data curation, J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J.; writing—review and editing, J.J., S.K. and T.C.; visualization, J.J.; supervision, T.C.; project administration, T.C.; funding acquisition, S.K. and T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF2021S1A5C2A02086884).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Hanyang Institute for Phonetics and Cognitive Sciences of Language. Approval ID: HIPCS-201510-02-1 (23 October 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/V9T6X.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the American English speakers for their participation in the experiment. We also thank the editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF2021S1A5C2A02086884).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kim, S.; Jang, J.; Cho, T. Articulatory characteristics of preboundary lengthening in interaction with prominence on tri-syllabic words in American English. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2017, 142, EL362–EL368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd, D. Articulatory vowel lengthening and coordination at phrasal junctures. Phonetica 2000, 57, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, T.; Son, M.; Kim, S. Articulatory reflexes of the three-way contrast in labial stops and kinematic evidence for domain-initial strengthening in Korean. J. Int. Phon. Assoc. 2016, 46, 129–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means; R Package Version 1.4.5; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Searle, S.R.; Speed, F.M.; Milliken, G.A. Population Marginal Means in the Linear Model: An Alternative to Least Squares Means. Am. Stat. 1980, 34, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Pouplier, M.; Rodriquez, F.; Lo, J.J.; Alderton, R.; Evans, B.G.; Reinisch, E.; Carignan, C. Language-specific and individual variation in anticipatory nasal coarticulation: A comparative study of American English, French, and German. J. Phon. 2024, 107, 101365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).