Chitosan Hydrochloride Applied as a Grapevine Biostimulant Modulates Sauvignon Blanc Vines’ Growth, Grape, and Wine Composition

Highlights

- Foliar chitosan hydrochloride increased antioxidant activity, polyphenolic content, and protein levels in Sauvignon Blanc berries.

- Wines from treated grapes exhibited higher total phenolics, polysaccharides, Abs 320 nm values, and total proteins.

- Chitosan biostimulation can modulate key grape secondary metabolites, thereby affecting wine composition.

- There is potential to modify the quality and stability of wine through the targeted application of biostimulants.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

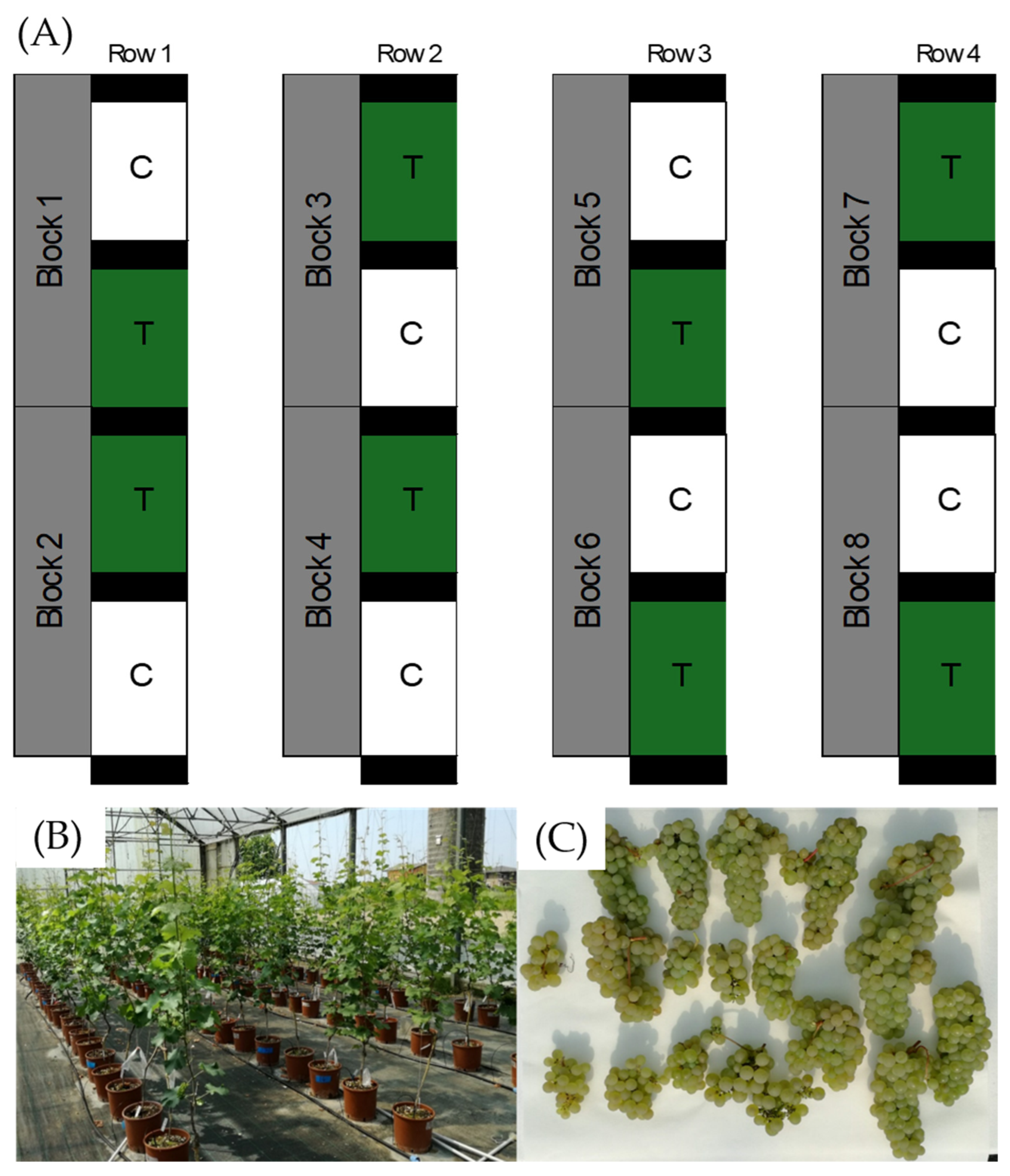

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sampling Protocol

2.4. Vine Growth Analyses

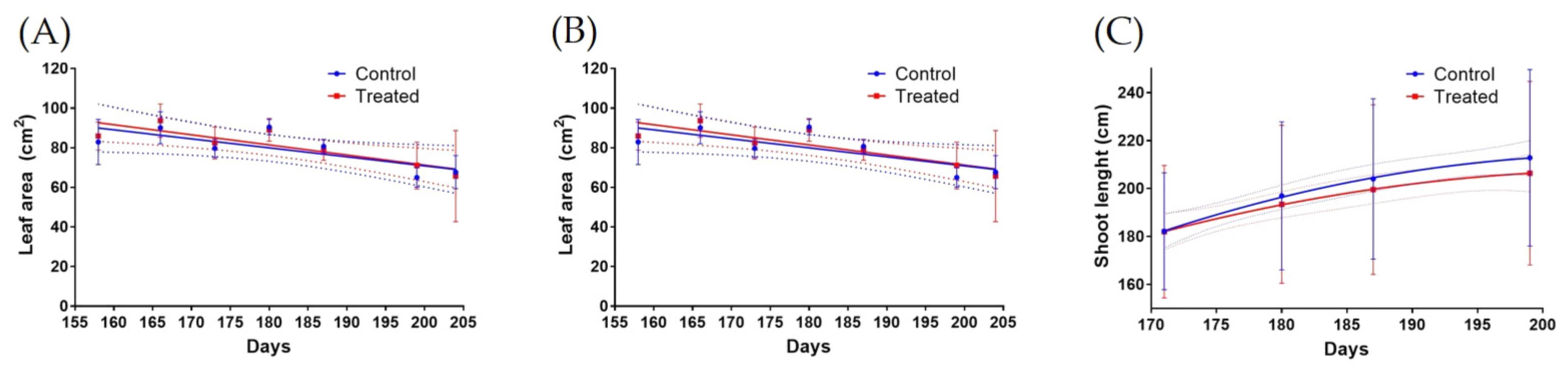

2.4.1. Shoot Length and Leaf Area

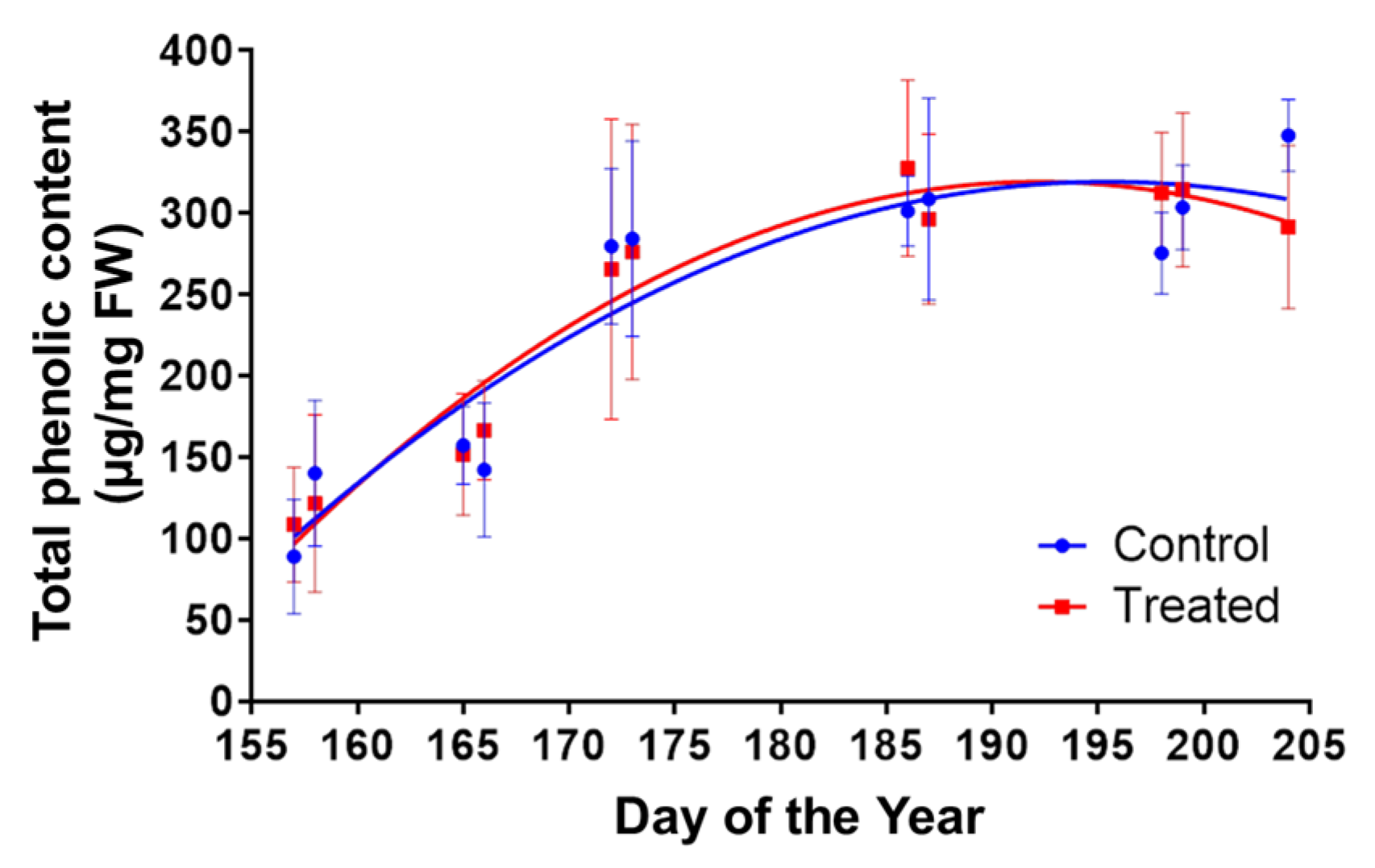

2.4.2. Leaves Total Phenolic Quantification

2.4.3. Berry Weight and Diameter

2.4.4. Yield and Berries’ Protein Content

2.4.5. Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO) Activity and Total Phenolic Quantification

2.4.6. Determination of Antioxidant Activity

2.5. Experimental Winemaking

2.5.1. Wine Composition and Protein Characterization

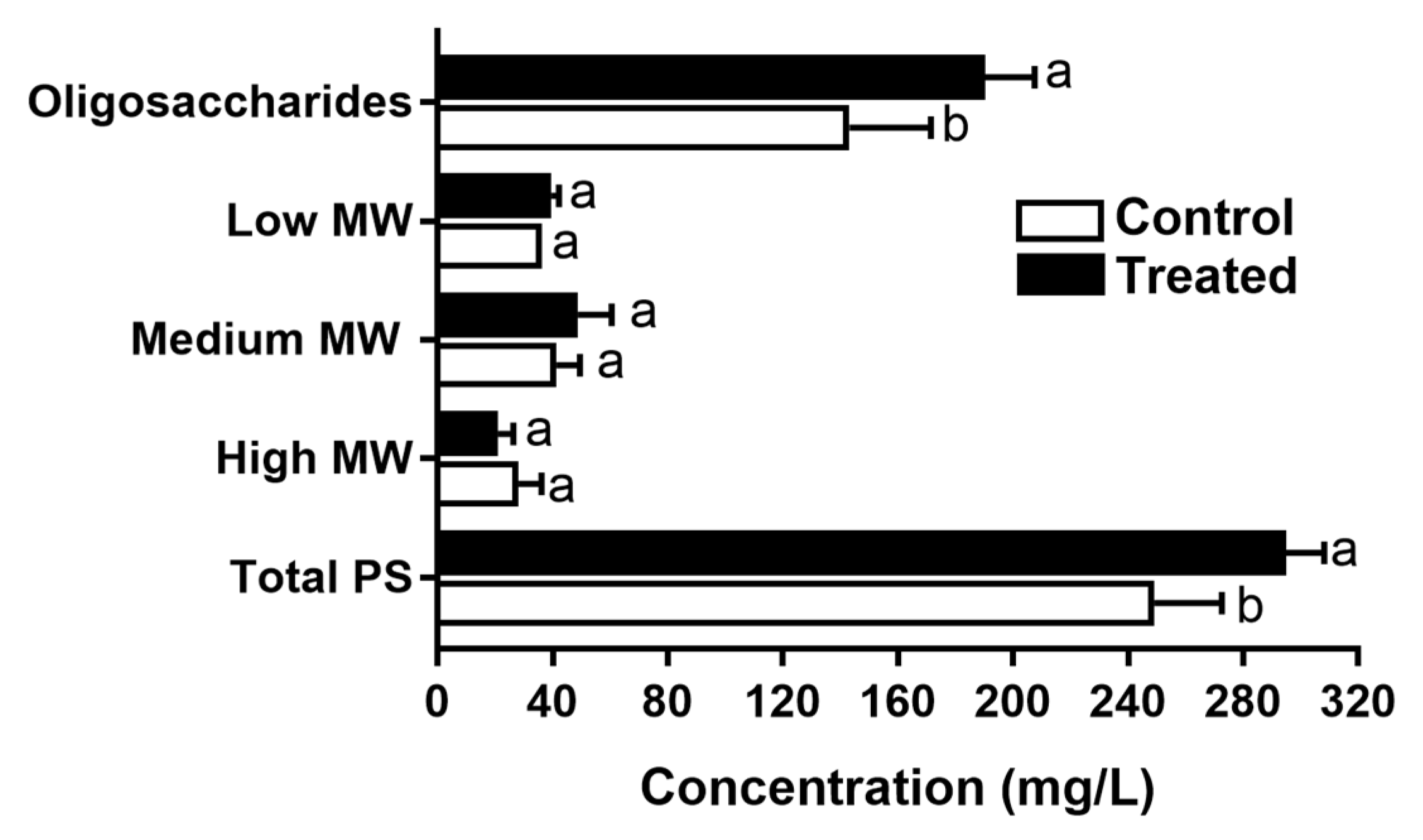

2.5.2. Wine Polysaccharide Quantification by High-Resolution Size-Exclusion Chromatography (HRSEC)

2.5.3. Wine Phenolics Quantification

2.5.4. Wine Colour Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chitosan Effect on Vine Growth, Yield, and Berry Composition

3.2. Oenological Parameters of Grape Juice and Wine

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Delrot, S.; Grimplet, J.; Carbonell-Bejerano, P.; Schwandner, A.; Bert, P.-F.; Bavaresco, L.; Dalla Costa, L.; Di Gaspero, G.; Duchêne, E.; Hausmann, L.; et al. Genetic and Genomic Approaches for Adaptation of Grapevine to Climate Change. In Genomic Designing of Climate Smart Fruit Crops; Kole, C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schreck, E.; Gontier, L.; Dumat, C.; Geret, F. Ecological and Physiological Effects of Soil Management Practices on Earthworm Communities in French Vineyards. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2012, 52, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lini, R.S.; Scanferla, D.T.P.; de Oliveira, N.G.; Aguera, R.G.; Santos, T.D.S.; Teixeira, J.J.V.; Kaneshima, A.M.D.S.; Mossini, S.A.G. Fungicides as a Risk Factor for the Development of Neurological Diseases and Disorders in Humans: A Systematic Review. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2024, 54, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliste, M.; Pérez-Lucas, G.; Garrido, I.; Fenoll, J.; Navarro, S. Risk Assessment of 1,2,4-Triazole-Typed Fungicides for Groundwater Pollution Using Leaching Potential Indices. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaunois, B.; Farace, G.; Jeandet, P.; Clément, C.; Baillieul, F.; Dorey, S.; Cordelier, S. Elicitors as Alternative Strategy to Pesticides in Grapevine? Current Knowledge on Their Mode of Action from Controlled Conditions to Vineyard. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 4837–4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.A.; Gupta, A. Secondary Metabolite Basis of Elicitor- and Effector-Triggered Immunity in Pathogen Elicitation Amid Infections. In Genetic Manipulation of Secondary Metabolites in Medicinal Plant; Singh, R., Kumar, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 225–251. ISBN 978-981-9949-39-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gozzo, F.; Faoro, F. Systemic Acquired Resistance (50 Years after Discovery): Moving from the Lab to the Field. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 12473–12491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capanoglu, E. The Potential of Priming in Food Production. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.; Gonçalves, B.; Cortez, I.; Castro, I. The Role of Biostimulants as Alleviators of Biotic and Abiotic Stresses in Grapevine: A Review. Plants 2022, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, J.; Castro, J.; Gonzalez, A.; Moenne, A. Seaweed Polysaccharides and Derived Oligosaccharides Stimulate Defense Responses and Protection Against Pathogens in Plants. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 2514–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paladines-Quezada, D.F.; Gil-Muñoz, R.; Apolinar-Valiente, R.; Williams, P.; Fernández-Fernández, J.I.; Doco, T. Effect of Applying Elicitors to Vitis vinifera L. Cv. Monastrell at Different Ripening Times on the Complex Carbohydrates of the Resulting Wines. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 248, 2369–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-García, A.I.; Martínez-Gil, A.M.; Cadahía, E.; Pardo, F.; Alonso, G.L.; Salinas, M.R. Oak Extract Application to Grapevines as a Plant Biostimulant to Increase Wine Polyphenols. Food Res. Int. 2014, 55, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Álvarez, E.P.; Sáenz de Urturi, I.; Rubio-Bretón, P.; Marín-San Román, S.; Murillo-Peña, R.; Parra-Torrejón, B.; Ramírez-Rodríguez, G.B.; Delgado-López, J.M.; Garde-Cerdán, T. Application of Elicitors, as Conventional and Nano Forms, in Viticulture: Effects on Phenolic, Aromatic and Nitrogen Composition of Tempranillo Wines. Beverages 2022, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portu, J.; López, R.; Baroja, E.; Santamaría, P.; Garde-Cerdán, T. Improvement of Grape and Wine Phenolic Content by Foliar Application to Grapevine of Three Different Elicitors: Methyl Jasmonate, Chitosan, and Yeast Extract. Food Chem. 2016, 201, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portu, J.; López, R.; Santamaría, P.; Garde-Cerdán, T. Methyl Jasmonate Treatment to Increase Grape and Wine Phenolic Content in Tempranillo and Graciano Varieties during Two Growing Seasons. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 240, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Gamboa, G.; Garde-Cerdán, T.; Rubio-Bretón, P.; Pérez-Álvarez, E.P. Seaweed Foliar Applications at Two Dosages to Tempranillo Blanco (Vitis vinifera L.) Grapevines in Two Seasons: Effects on Grape and Wine Volatile Composition. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salifu, R.; Chen, C.; Sam, F.E.; Jiang, Y. Application of Elicitors in Grapevine Defense: Impact on Volatile Compounds. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalini, S.; Ruggiero, A.; Rapparini, F.; Neri, L.; Tonni, M.; Iriti, M. The Application of Chitosan and Benzothiadiazole in Vineyard (Vitis vinifera L. Cv Groppello Gentile) Changes the Aromatic Profile and Sensory Attributes of Wine. Food Chem. 2014, 162, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žiarovská, J.; Zamiešková, L.; Bilčíková, J.; Zeleňáková, L.; Sabo, J.; Kačániová, M. Comparative Analysis of Allergenic Chitinase Expression in Grape Varieties. J. Hyg. Eng. Des. 2021, 34, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Van Sluyter, S.C.; McRae, J.M.; Falconer, R.J.; Smith, P.A.; Bacic, A.; Waters, E.J.; Marangon, M. Wine Protein Haze: Mechanisms of Formation and Advances in Prevention. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 4020–4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marassi, V.; Marangon, M.; Zattoni, A.; Vincenzi, S.; Versari, A.; Reschiglian, P.; Roda, B.; Curioni, A. Characterization of Red Wine Native Colloids by Asymmetrical Flow Field-Flow Fractionation with Online Multidetection. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 110, 106204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangon, M.; Marassi, V.; Mattivi, F.; Marangon, C.M.; Moio, L.; Roda, B.; Rolle, L.; Ugliano, M.; Versari, A.; Zanella, S.; et al. The Role of Protein-Phenolic Interactions in the Formation of Red Wine Colloidal Particles: This Is an Original Research Article Submitted in Cooperation with Macrowine 2025. OENO One 2025, 59, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Gamboa, G.; Romanazzi, G.; Garde-Cerdán, T.; Pérez-Álvarez, E.P. A Review of the Use of Biostimulants in the Vineyard for Improved Grape and Wine Quality: Effects on Prevention of Grapevine Diseases. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, G.; Brunetti, G. Effects of the Times of Application of a Soil Humic Acid on Berry Quality of Table Grape (Vitis vinifera L.) Cv Italia. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 8, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde-Cerdán, T.; Mancini, V.; Carrasco-Quiroz, M.; Servili, A.; Gutiérrez-Gamboa, G.; Foglia, R.; Pérez-Álvarez, E.P.; Romanazzi, G. Chitosan and Laminarin as Alternatives to Copper for Plasmopara Viticola Control: Effect on Grape Amino Acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 7379–7386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugliese, M.; Monchiero, M.; Gullino, M.L.; Garibaldi, A. Application of Laminarin and Calcium Oxide for the Control of Grape Powdery Mildew on Vitis Vinifera Cv. Moscato. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2018, 125, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bona, G.S.; Vincenzi, S.; De Marchi, F.; Angelini, E.; Bertazzon, N. Chitosan Induces Delayed Grapevine Defense Mechanisms and Protects Grapevine against Botrytis Cinerea. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2021, 128, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Ruiz-May, E.; Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T.; Gómez-Peraza, R.L.; Verma, K.K.; Shekhawat, M.S.; Pinto, C.; Falco, V.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R. Viewpoint of Chitosan Application in Grapevine for Abiotic Stress/Disease Management towards More Resilient Viticulture Practices. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Singh, R.K.; Gomes, N.; Soares, B.G.; Silva, A.; Falco, V.; Capita, R.; Alonso-Calleja, C.; Pereira, J.E.; Amaral, J.S.; et al. Comparative Insight upon Chitosan Solution and Chitosan Nanoparticles Application on the Phenolic Content, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Individual Grape Components of Sousão Variety. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Soares, B.; Goufo, P.; Castro, I.; Cosme, F.; Pinto-Sintra, A.L.; Inês, A.; Oliveira, A.A.; Falco, V. Chitosan Upregulates the Genes of the ROS Pathway and Enhances the Antioxidant Potential of Grape (Vitis vinifera L. ‘Touriga Franca’ and ’Tinto Cão’) Tissues. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Martins, V.; Soares, B.; Castro, I.; Falco, V. Chitosan Application in Vineyards (Vitis vinifera L. Cv. Tinto Cão) Induces Accumulation of Anthocyanins and Other Phenolics in Berries, Mediated by Modifications in the Transcription of Secondary Metabolism Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, D.H.; Eichhorn, K.W.; Bleiholder, H.; Klose, R.; Meier, U.; Weber, E. Growth Stages of the Grapevine: Phenological Growth Stages of the Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. vinifera)—Codes and Descriptions According to the Extended BBCH Scale. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 1995, 1, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsialtas, J.T.; Koundouras, S.; Zioziou, E. Leaf Area Estimation by Simple Measurements and Evaluation of Leaf Area Prediction Models in Cabernet-Sauvignon Grapevine Leaves. Photosynthetica 2008, 46, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruperti, B.; Botton, A.; Populin, F.; Eccher, G.; Brilli, M.; Quaggiotti, S.; Trevisan, S.; Cainelli, N.; Guarracino, P.; Schievano, E.; et al. Flooding Responses on Grapevine: A Physiological, Transcriptional, and Metabolic Perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meggio, F.; Trevisan, S.; Manoli, A.; Ruperti, B.; Quaggiotti, S. Systematic Investigation of the Effects of a Novel Protein Hydrolysate on the Growth, Physiological Parameters, Fruit Development and Yield of Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L., Cv Sauvignon Blanc) under Water Stress Conditions. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidant by Means of Foline Ciocalteu Reagent. Methods Enzym. 1999, 299, 153–178. [Google Scholar]

- Zocca, F.; Lomolino, G.; Spettoli, P.; Lante, A. Deriphat 2-DE to Visualize Polyphenol Oxidase in Moscato and Prosecco Grapes. Electrophoresis 2007, 28, 3992–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapeanu, G.; Van Loey, A.; Smout, C.; Hendrickx, M. Biochemical Characterization and Process Stability of Polyphenoloxidase Extracted from Victoria Grape (Vitis vinifera Ssp. Sativa). Food Chem. 2006, 94, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, K.; Nakayama, M.; Koshioka, M.; Ippoushi, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Kohata, K.; Yamauchi, Y.; Ito, H.; Higashio, H. Phenolic Antioxidants from the Leaves of Corchorus olitorius L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 3963–3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cisneros, M.; Canazza, E.; Mihaylova, D.; Lante, A. The Effectiveness of Extracts of Spent Grape Pomaces in Improving the Oxidative Stability of Grapeseed Oil. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangon, M.; Lucchetta, M.; Duan, D.; Stockdale, V.J.; Hart, A.; Rogers, P.J.; Waters, E.J. Protein Removal from a Chardonnay Juice by Addition of Carrageenan and Pectin. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2012, 18, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenzi, S.; Mosconi, S.; Zoccatelli, G.; Pellegrina, C.D.; Veneri, G.; Chignola, R.; Peruffo, A.; Curioni, A.; Rizzi, C. Development of a New Procedure for Protein Recovery and Quantification in Wine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2005, 56, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, H.; Beier, H.; Gross, H.J. Improved Silver Staining of Plant Proteins, RNA and DNA in Polyacrylamide Gels. Electrophoresis 1987, 8, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.D.P.D.; Nadai, C.; da Silva Duarte, V.; Brearley-Smith, E.J.; Marangon, M.; Vincenzi, S.; Giacomini, A.; Corich, V. Starmerella Bacillaris Strains Used in Sequential Alcoholic Fermentation with Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Improves Protein Stability in White Wines. Fermentation 2022, 8, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayestarán, B.; Guadalupe, Z.; León, D. Quantification of Major Grape Polysaccharides (Tempranillo v.) Released by Maceration Enzymes during the Fermentation Process. Anal. Chim. Acta 2004, 513, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliordos, D.E.; Alatzas, A.; Kontoudakis, N.; Kouki, A.; Unlubayir, M.; Gémin, M.-P.; Tako, A.; Hatzopoulos, P.; Lanoue, A.; Kotseridis, Y. Abscisic Acid and Chitosan Modulate Polyphenol Metabolism and Berry Qualities in the Domestic White-Colored Cultivar Savvatiano. Plants 2022, 11, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, E.; Fucile, M.; Mattii, G.B. Biostimulants in Viticulture: A Sustainable Approach against Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Plants 2022, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olavarrieta, C.E.; Sampedro, M.C.; Vallejo, A.; Štefelová, N.; Barrio, R.J.; De Diego, N. Biostimulants as an Alternative to Improve the Wine Quality from Vitis vinifera (Cv. Tempranillo) in La Rioja. Plants 2022, 11, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, B.; Barbosa, C.; Oliveira, M.J. Chitosan Application towards the Improvement of Grapevine Performance and Wine Quality. Ciênc. Téc. Vitivinícola 2023, 38, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Rahman, M.; Khan, M.A.R.; Bhowmik, P.; Mahmud, N.U.; Tanveer, M.; Islam, T. Mechanism of Plant Growth Promotion and Disease Suppression by Chitosan Biopolymer. Agriculture 2020, 10, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Montes, E.; Escalona, J.M.; Tomás, M.; Martorell, S.; Bota, J.; Tortosa, I.; Medrano, H. Carbon Balance in Grapevines (Vitis vinifera L.): Effect of Environment, Cultivar and Phenology on Carbon Gain, Losses and Allocation. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2022, 28, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katalinic, V.; Mozina, S.S.; Generalic, I.; Skroza, D.; Ljubenkov, I.; Klancnik, A. Phenolic Profile, Antioxidant Capacity, and Antimicrobial Activity of Leaf Extracts from Six Vitis vinifera L. Varieties. Int. J. Food Prop. 2013, 16, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichyangkura, R.; Chadchawan, S. Biostimulant Activity of Chitosan in Horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Esteso, M.J.; Selles-Marchart, S.; Vera-Urbina, J.C.; Pedreno, M.A.; Bru-Martinez, R. Changes of Defense Proteins in the Extracellular Proteome of Grapevine (Vitis vinifera Cv. Gamay) Cell Cultures in Response to Elicitors. J. Proteom. 2009, 73, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Z.M.; Mahapatra, R.; Jampala, S.S.M. Chapter 11—Role of Fungal Elicitors in Plant Defense Mechanism. In Molecular Aspects of Plant Beneficial Microbes in Agriculture; Sharma, V., Salwan, R., Al-Ani, L.K.T., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 143–158. ISBN 978-0-12-818469-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim, S.; Usha, K.; Singh, B. Pathogenesis-Related (PR)-Proteins: Chitinase and β-1,3-Glucanase in Defense Mechanism against Malformation in Mango (Mangifera indica L.). Sci. Hortic. 2011, 130, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumudini, B.S.; Jayamohan, N.S.; Patil, S.V.; Govardhana, M. Chapter 11—Primary Plant Metabolism During Plant–Pathogen Interactions and Its Role in Defense. In Plant Metabolites and Regulation Under Environmental Stress; Ahmad, P., Ahanger, M.A., Singh, V.P., Tripathi, D.K., Alam, P., Alyemeni, M.N., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 215–229. ISBN 978-0-12-812689-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, M.; Tassoni, A.; Franceschetti, M.; Righetti, L.; Naldrett, M.J.; Bagni, N. Chitosan Treatment Induces Changes of Protein Expression Profile and Stilbene Distribution in Vitis vinifera Cell Suspensions. Proteomics 2009, 9, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constabel, C.P.; Barbehenn, R. Defensive Roles of Polyphenol Oxidase in Plants. In Induced Plant Resistance to Herbivory; Schaller, A., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 253–270. ISBN 978-1-4020-8182-8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Guo, A.; Wang, H. Mechanisms of Oxidative Browning of Wine. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echave, J.; Barral, M.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Bottle Aging and Storage of Wines: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somers, T.C.; Ziemelis, G. Spectral Evaluation of Total Phenolic Components in Vitis vinifera: Grapes and Wines. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1985, 36, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, E.J.; Alexander, G.; Muhlack, R.; Pocock, K.F.; Colby, C.; O’neill, B.K.; Høj, P.B.; Jones, P. Preventing Protein Haze in Bottled White Wine. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2005, 11, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curioni, A.; Brearley-Smith, E.J.; Marangon, M. Are Wines from Interspecific Hybrid Grape Varieties Safe for Allergic Consumers? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 15037–15038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, B.; Marangon, M.; Curioni, A.; Waters, E.; Marchal, R. 8—New Directions in Stabilization, Clarification, and Fining. In Managing Wine Quality, 2nd ed.; Reynolds, A.G., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 245–301. ISBN 978-0-08-102065-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pastorello, E.A.; Farioli, L.; Pravettoni, V.; Ortolani, C.; Fortunato, D.; Giuffrida, M.G.; Perono Garoffo, L.; Calamari, A.M.; Brenna, O.; Conti, A. Identification of Grape and Wine Allergens as an Endochitinase 4, a Lipid-Transfer Protein, and a Thaumatin. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apolinar-Valiente, R.; Ruiz-García, Y.; Williams, P.; Gil-Muñoz, R.; Gómez-Plaza, E.; Doco, T. Preharvest Application of Elicitors to Monastrell Grapes: Impact on Wine Polysaccharide and Oligosaccharide Composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 11151–11157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morkunas, I.; Ratajczak, L. The Role of Sugar Signaling in Plant Defense Responses against Fungal Pathogens. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2014, 36, 1607–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, A.I.; Rafudeen, M.S.; Golldack, D. Physiological Aspects of Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides in Plants: Protection against Abiotic Stress. Plant Biol. 2014, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Untreated | Treated | Variation | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berry weight (g) | 1.24 ± 0.09 | 1.20 ± 0.07 | −3.2% | ns |

| Berry diameter (cm) | 1.22 ± 0.14 | 1.21 ± 0.02 | −0.8% | ns |

| Yield/vine (kg) | 0.41 ± 0.09 | 0.43 ± 0.05 | +4.9% | ns |

| Protein content (µg BSA/mL) | 158.16 ± 13.33 | 383.33 ± 121.67 | +142.3% | *** |

| PPO activity (AU/min/µg protein) | 22.96 ± 2.31 | 8.14 ± 3.11 | −64.5% | *** |

| Total phenolics (mg GAE/g FW) | 4.00 ± 0.49 | 4.67 ± 0.30 | +16.7% | *** |

| Antioxidant activity (FRAP, mg TE/g FW) | 3.90 ± 0.94 | 5.02 ± 0.38 | +28.7% | *** |

| Parameter | Untreated | Treated | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brix (°) | 16.95 ± 1.72 | 17.26 ± 2.37 | ns |

| Glucose + Fructose (g/L) | 164.68 ± 18.78 | 169.46 ± 27.33 | ns |

| pH | 2.89 ± 0.03 | 2.91 ± 0.05 | ns |

| Titratable acidity (g/L) | 11.25 ± 0.82 | 11.05 ± 0.97 | ns |

| Tartaric acid (g/L) | 9.03 ± 0.43 | 9.13 ± 0.25 | ns |

| Malic acid (g/L) | 4.51 ± 0.59 | 4.31± 0.52 | ns |

| Citric acid (g/L) | 0.31 ±0.01 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | ns |

| Parameter | Untreated | Treated | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol content (% v/v) | 10.90 ± 0.52 | 10.71 ± 0.37 | ns |

| Glucose (g/L) | 3.46 ± 0.11 | 3.12 ± 0.14 | ** |

| Fructose (g/L) | 0.76 ± 0.08 | 0.77 ± 0.07 | ns |

| pH | 2.84 ± 0.01 | 2.84 ± 0.02 | ns |

| Titratable acidity (g/L) | 12.28 ± 0.36 | 11.65 ± 0.24 | * |

| Tartaric acid (g/L) | 5.64 ± 0.25 | 5.62 ± 0.22 | ns |

| Malic acid (g/L) | 4.00 ± 0.24 | 3.70 ± 0.14 | ns |

| Citric acid (g/L) | 0.57 ± 0.05 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | * |

| Acetic acid (g/L) | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 0.44 ± 0.02 | * |

| Potassium (g/L) | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.41 ± 0.02 | ** |

| Abs 320 nm (mAU) | 901 ± 19 | 991 ± 23 | *** |

| Abs 420 nm (mAU) | 125 ± 20 | 122 ± 8 | ns |

| Total phenolics (mg/L) | 160.6 ± 3.9 | 181.5 ± 7.5 | * |

| Total proteins (mg/L) | 94.1 ± 1.4 | 107.1 ± 2.7 | ** |

| Total polysaccharides (mg/L) | 249.2 ± 23.5 | 294.8 ± 13.5 | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marangon, M.; Botton, A.; Meggio, F.; Lante, A.; Tinello, F.; De Iseppi, A.; Mayr Marangon, C.; Vincenzi, S.; Curioni, A. Chitosan Hydrochloride Applied as a Grapevine Biostimulant Modulates Sauvignon Blanc Vines’ Growth, Grape, and Wine Composition. Beverages 2025, 11, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060168

Marangon M, Botton A, Meggio F, Lante A, Tinello F, De Iseppi A, Mayr Marangon C, Vincenzi S, Curioni A. Chitosan Hydrochloride Applied as a Grapevine Biostimulant Modulates Sauvignon Blanc Vines’ Growth, Grape, and Wine Composition. Beverages. 2025; 11(6):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060168

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarangon, Matteo, Alessandro Botton, Franco Meggio, Anna Lante, Federica Tinello, Alberto De Iseppi, Christine Mayr Marangon, Simone Vincenzi, and Andrea Curioni. 2025. "Chitosan Hydrochloride Applied as a Grapevine Biostimulant Modulates Sauvignon Blanc Vines’ Growth, Grape, and Wine Composition" Beverages 11, no. 6: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060168

APA StyleMarangon, M., Botton, A., Meggio, F., Lante, A., Tinello, F., De Iseppi, A., Mayr Marangon, C., Vincenzi, S., & Curioni, A. (2025). Chitosan Hydrochloride Applied as a Grapevine Biostimulant Modulates Sauvignon Blanc Vines’ Growth, Grape, and Wine Composition. Beverages, 11(6), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060168