The Volatile Composition of Commercially Available New England India Pale Ales as Defined by Hop Blending

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Beer Selection

2.2. Data Collection and Analytical Workflow Overview

2.3. Target Compound Database Building

2.4. Targeted Spectral Deconvolution and Compound Identification

- 1.

- Q-ratio: Defines the deviation threshold among the confirming ions and main ions within a scan; a potential peak is identified as a minimum of five consecutive scans meeting the threshold. A Q-ratio of 20% was set for this study.

- 2.

- Reduced Intensity Deviation (ΔI): Describes the average deviation among ion ratios across the peak; lower ΔI values indicate a stronger spectral match (Equation (2)). An acceptable compound match is determined by ΔI ≤ K + Δ0/Ai, where K is the user-defined (acceptable) relative percent difference and Δ0 is the additive error attributable to instrument noise and/or background signal.

- 3.

- Scan-to-Scan Variance (ΔE): The SSV is calculated from ΔE = ΔI × log (Ai). The algorithm calculates the relative error by comparing the mass spectrum of one scan against the others. The smaller the difference, the closer the SSV is to zero, the better the spectral agreement. It is acceptable when ΔI or ΔE are below the maximum allowable error, ΔEmax, in five consecutive scans. In this study the maximum allowable scan-to-scan error, ΔEmax, was set to 5 [25,26].

- 4.

- Q-value: Measures the total deviation between the observed and expected ion ratios across the peak, expressed as percentage. Values approaching 100 indicate higher certainty between sample and reference spectra.

2.5. Thin-Film Solid-Phase Microextraction (TF-SPME) of Beer Samples

2.6. Sequential GC-GC/MS Parameters

2.7. GC/MS Parameters

2.8. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Volatiles

3.1.1. Esters

3.1.2. Terpenes

3.1.3. Ketones

3.1.4. Other

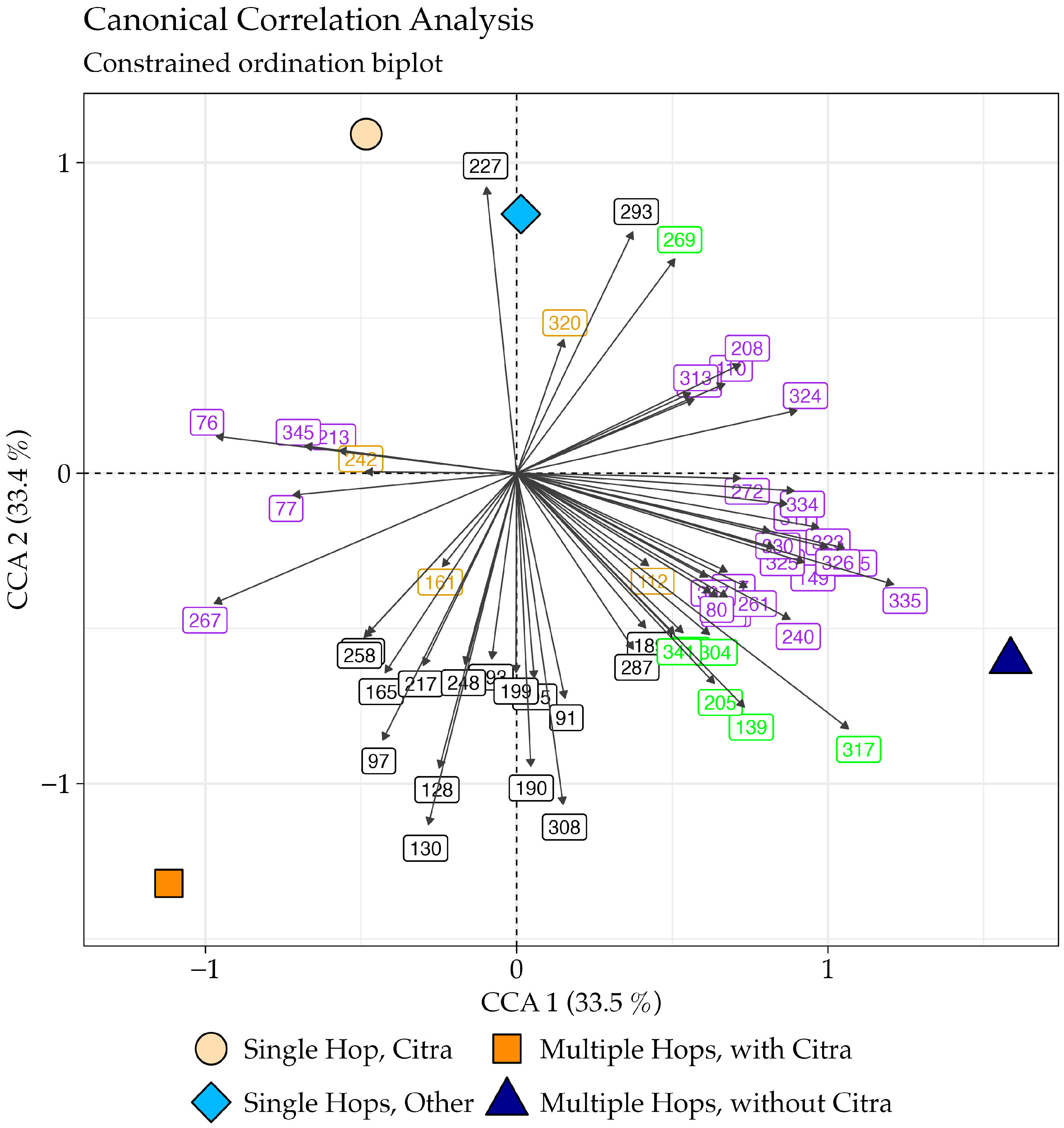

3.2. Chemical Signatures of Hop Profile

3.3. Linear Discriminant Analysis

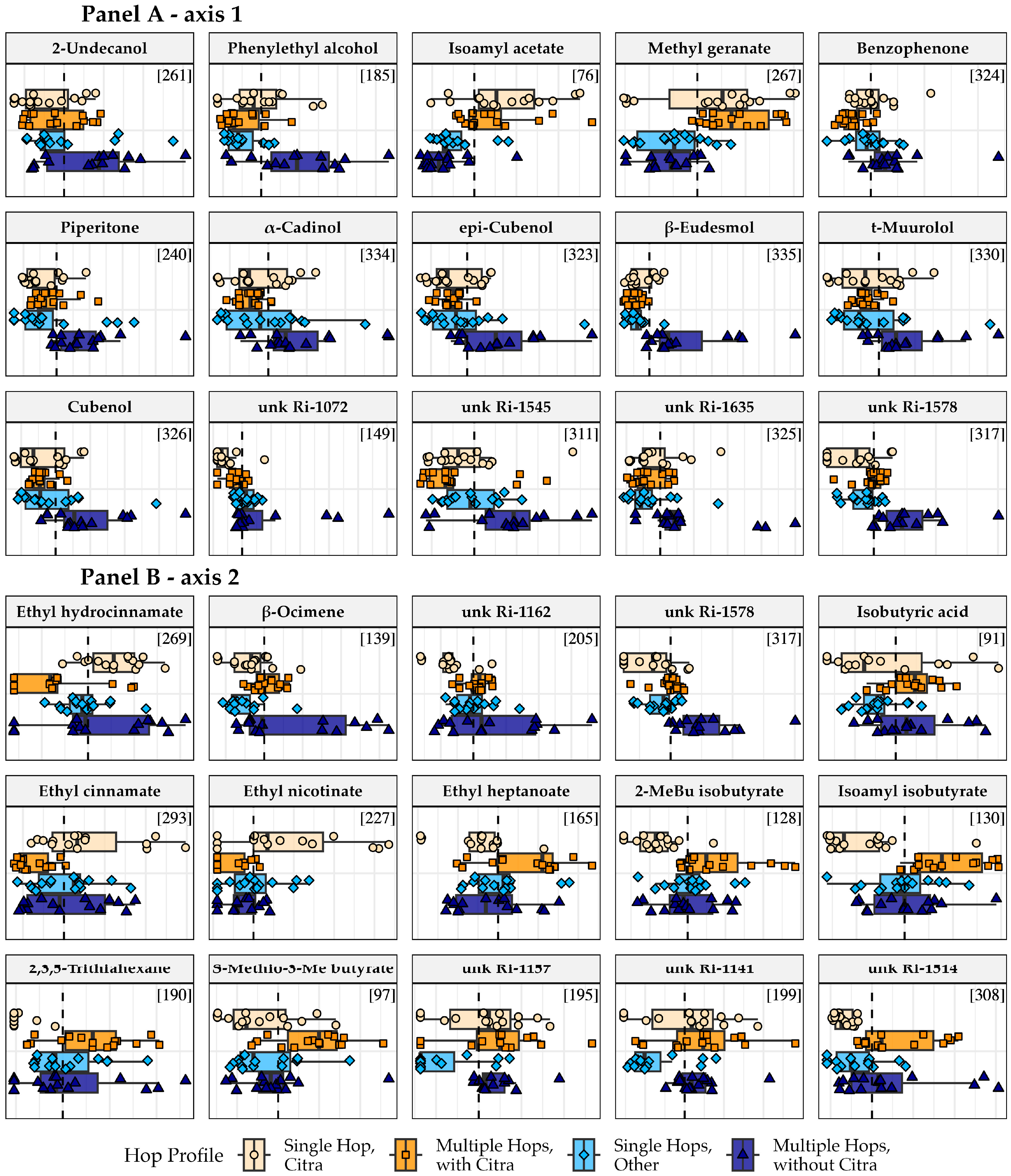

3.4. Boxplot Analysis of Top Compounds

4. Discussion

Hop Variety as a Driver of Volatile Diversity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| SPME | Solid Phase Microextraction |

| CCA | Canonical Correlation Analysis |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| NEIPA | New England India Pale Ale |

References

- Maye, J.P.; Smith, R. Hidden Secrets of the New England IPA. Master Brew. Assoc. Am. 2018, 55, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hop Growers of America. 2023 Statistical Report; Hop Growers of America: Yakima, WA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lafontaine, S.R.; Shellhammer, T.H. Sensory Directed Mixture Study of Beers Dry-Hopped with Cascade, Centennial, and Chinook. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2018, 76, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tressl, R.; Friese, L.; Fendesack, F.; Koeppler, H. Gas Chromatographic-Mass Spectrometric Investigation of Hop Aroma Constituents in Beer. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1978, 26, 1422–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, T.; Teramoto, S.; Fujita, A.; Yamada, O. Principal Component Analysis of Hop-Derived Odorants Identified by Stir Bar Sorptive Extraction Method. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2021, 79, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lermusieau, G.; Bulens, M.; Collin, S. Use of GC−Olfactometry to Identify the Hop Aromatic Compounds in Beer. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 3867–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samia, R.; Shayevitz, A.; Fischborn, T.; Shellhammer, T.H. Wort Nitrogen and Yeast Strain Drive Thiol Release, Flavor Expression, and Fermentation Performance in Beer. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2025, 83, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawa-Rygielska, J.; Adamenko, K.; Pietrzak, W.; Paszkot, J.; Głowacki, A.; Gasiński, A. Characteristics of New England India Pale Ale Beer Produced with the Use of Norwegian KVEIK Yeast. Molecules 2022, 27, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takoi, K.; Koie, K.; Itoga, Y.; Katayama, Y.; Shimase, M.; Nakayama, Y.; Watari, J. Biotransformation of Hop-Derived Monoterpene Alcohols by Lager Yeast and Their Contribution to the Flavor of Hopped Beer. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 5050–5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, D.G.; Simaeys, K.R.V.; Lafontaine, S.R.; Shellhammer, T.H. A Comparison of Single-Stage and Two-Stage Dry-Hopping Regimes. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2019, 77, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, D.G.; Lafontaine, S.R.; Shellhammer, T.H. Extraction Efficiency of Dry-Hopping. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2019, 77, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettberg, N.; Schubert, C.; Dennenlöhr, J.; Thörner, S.; Knoke, L.; Maxminer, J. Instability of Hop-Derived 2-Methylbutyl Isobutyrate during Aging of Commercial Pasteurized and Unpasteurized Ales. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2020, 78, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, O.; Hofmann, S.; Braumann, I.; Jensen, S.; Fenton, A.; Oladokun, O. Changes in Key Hop-derived Compounds and Their Impact on Perceived Dry-hop Flavour in Beers after Storage at Cold and Ambient Temperature. J. Inst. Brew. 2021, 127, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhaus, M.; Schieberle, P. Comparison of the Most Odor-Active Compounds in Fresh and Dried Hop Cones (Humulus lupulus L. Variety Spalter Select) Based on GC−Olfactometry and Odor Dilution Techniques. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1776–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, D.G.; Francis, G.W. The Capacity of Humans to Identify Odors in Mixtures. Physiol. Behav. 1989, 46, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.G.; Lim, J.; Osterhoff, F.; Blacher, K.; Nachtigal, D. Taste Mixture Interactions: Suppression, Additivity, and the Predominance of Sweetness. Physiol. Behav. 2010, 101, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delwiche, J. The Impact of Perceptual Interactions on Perceived Flavor. Food Qual. Prefer. 2004, 15, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takoi, K.; Itoga, Y.; Matsumoto, I.; Nakayama, Y. Control of Hop Aroma Impression of Beer with Blend-Hopping Using Geraniol-Rich Hop and New Hypothesis of Synergy among Hop-Derived Flavour Compounds. BrewingScience 2016, 69, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, F.; Caldeira, M.; Câmara, J.S. Development of a Dynamic Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction Procedure Coupled to GC–qMSD for Evaluation the Chemical Profile in Alcoholic Beverages. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 609, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, R.F. Volatile Aroma Components of Australian Port Wines. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1980, 31, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, D.; Effting, L.; Cremasco, H.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Recent Applications of Mixture Designs in Beverages, Foods, and Pharmaceutical Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods 2021, 10, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, S.C.; Walker, P.; Orians, C.M.; Robbat, A. The Chemistry of Green and Roasted Coffee by Selectable 1D/2D Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry with Spectral Deconvolution. Molecules 2022, 27, 5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kfoury, N.; Baydakov, E.; Gankin, Y.; Robbat, A. Differentiation of Key Biomarkers in Tea Infusions Using a Target/Nontarget Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Workflow. Food Res. Int. 2018, 113, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalsick, A.; Kfoury, N.; Robbat, A.; Ahmed, S.; Orians, C.; Griffin, T.; Cash, S.B.; Stepp, J.R. Metabolite Profiling of Camellia Sinensis by Automated Sequential, Multidimensional Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Reveals Strong Monsoon Effects on Tea Constituents. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1370, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbat, A.; Wilton, N.M. A New Spectral Deconvolution–Selected Ion Monitoring Method for the Analysis of Alkylated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Complex Mixtures. Talanta 2014, 125, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbat, A.; Kfoury, N.; Baydakov, E.; Gankin, Y. Optimizing Targeted/Untargeted Metabolomics by Automating Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Workflows. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1505, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.J.; Jung, M.Y. Simple and Fast Sample Preparation Followed by Gas Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) for the Analysis of 2- and 4-Methylimidazole in Cola and Dark Beer. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; Posit Software, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package 2001, version 2.7-1; The R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-387-95457-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, I.H.; Namgung, H.-J.; Choi, H.-K.; Kim, Y.-S. Volatiles and Key Odorants in the Pileus and Stipe of Pine-Mushroom (Tricholoma matsutake Sing.). Food Chem. 2008, 106, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I.; Maccioni, S.; Baldini, R. Phytochemical Typologies in Some Populations of Myrtus communis L. on Caprione Promontory (East Liguria, Italy). Food Chem. 2004, 85, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, C.E.; Salamanca, G.; Pino, J.A. Aroma Volatile Constituents of Colombian Varieties of Mango (Mangifera indica L.). Flavour Fragr. J. 2007, 22, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, M.D.; Quijano, C.E.; Pino, J.A. Volatile Compounds of Chile Pepper (Capsicum annuum L. Var. Glabriusculum) at Two Ripening Stages. Flavour Fragr. J. 2009, 24, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, J.A.; Mesa, J.; Muñoz, Y.; Martí, M.P.; Marbot, R. Volatile Components from Mango (Mangifera indica L.) Cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2213–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J.C.; Grimm, C.C. Identification of Volatile Compounds in Cantaloupe at Various Developmental Stages Using Solid Phase Microextraction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premecz, J.E.; Ford, M.E. Gas Chromatographic Separation of Substitutes Pyridines. J. Chromatogr. 1987, 388, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carunchia Whetstine, M.E.; Croissant, A.E.; Drake, M.A. Characterization of Dried Whey Protein Concentrate and Isolate Flavor. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 3826–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahattanatawee, K.; Goodner, K.L.; Baldwin, E.A. Volatile Constituents and Character Impact Compounds of Selected Florrida’s Tropical Fruit. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 2005, 118, 414–418. [Google Scholar]

- Benkaci–Ali, F.; Baaliouamer, A.; Meklati, B.Y.; Chemat, F. Chemical Composition of Seed Essential Oils from Algerian Nigella sativa Extracted by Microwave and Hydrodistillation. Flavour Fragr. J. 2007, 22, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccouri, B.; Temime, S.; Campeol, E.; Cioni, P.; Daoud, D.; Zarrouk, M. Application of Solid-Phase Microextraction to the Analysis of Volatile Compounds in Virgin Olive Oils from Five New Cultivars. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, J.G.S.; Andrade, E.H.A.; Da Silva, A.C.M.; Oliveira, J.; Carreira, L.M.M.; Araújo, J.S. Leaf Volatile Oils from Four Brazilian Xylopia Species. Flavour Fragr. J. 2005, 20, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, V.; Arfan, M.; Shabir, A.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D.; Skaltsa, H. Composition and Antioxidant Activity of the Essential Oil of Teucrium royleanum Wall. Ex Benth Growing in Pakistan. Flavour Fragr. J. 2007, 22, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuming, W.A.; Beauchamp, P.S.; Descalzo, J.T.; Dev, B.C.; Dev, V.; Frost, S.; Ma, C.W. Essential Oil Composition of Four Lomatium Raf. Species and Their Chemotaxonomy. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2005, 33, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.F. Chemical Composition and Toxicities of Essential Oil of Illicium fragesii Fruits against Sitophilus zeamais. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 18179–18184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamaharavo, N.R. Retention Data; NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2014.

- Feizbakhsh, A.; Naeemy, A. Volatile Constituents of Essential Oils of Eleocharis pauciflora (Light) Link and Eleocharis uniglumis (Link) J.A. Schultes Growing Wild in Iran. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2011, 25, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeira, S.F.; Moura, F.D.S.; Alves, V.D.L.; Oliveira, F.M.D.; Bento, E.S.; Conserva, L.M.; Andrade, E.H.D.A. Neutral Components from Hexane Extracts of Croton sellowii. Flavour Fragr. J. 2004, 19, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzit, M.; Baaliouamer, A.; Faleiro, M.L.; Miguel, M.G. Composition of the Essential Oils of Thymus and Origanum Species from Algeria and Their Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 6314–6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaltsa, H.D.; Demetzos, C.; Lazari, D.; Sokovic, M. Essential Oil Analysis and Antimicrobial Activity of Eight Stachys Species from Greece. Phytochemistry 2003, 64, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbontín, C.; Gaete-Eastman, C.; Vergara, M.; Herrera, R.; Moya-León, M.A. Treatment with 1-MCP and the Role of Ethylene in Aroma Development of Mountain Papaya Fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 43, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dural, H.; Bagci, Y.; Ertugrul, K.; Demirelma, H.; Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I. Essential Oil Composition of Two Endemic Centaurea Species from Turkey, Centaurea mucronifera and Centaurea chrysantha, Collected in the Same Habitat. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2003, 31, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setzer, W.N.; Noletto, J.A.; Lawton, R.O.; Haber, W.A. Leaf Essential Oil Composition of Five Zanthoxylum Species from Monteverde, Costa Rica. Mol. Divers. 2005, 9, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino, J.A.; Márquez, E.; Quijano, C.E.; Castro, D. Volatile Compounds in Noni (Morinda citrifolia L.) at Two Ripening Stages. Ciênc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2010, 30, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, C.; Thörner, S.; Knoke, L.; Rettberg, N. Development and Validation of a HS-SPME-GC-SIM-MS Multi-Method Targeting Hop-Derived Esters in Beer. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2023, 81, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvim, R.P.R.; De Cássia Oliveira Gomes, F.; Garcia, C.F.; De Lourdes Almeida Vieira, M.; De Resende Machado, A.M. Identification of Volatile Organic Compounds Extracted by Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction in Specialty Beers Produced in Brazil: Identification of Volatile Compounds in Specialty Beers. J. Inst. Brew. 2017, 123, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettberg, N.; Thörner, S.; Labus, A.B. Aroma Active Monocarboxylic Acids–Origin and Analytical Characterization in Fresh and Aged Hops. BrewingScience 2014, 67, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lafontaine, S.; Varnum, S.; Roland, A.; Delpech, S.; Dagan, L.; Vollmer, D.; Kishimoto, T.; Shellhammer, T. Impact of Harvest Maturity on the Aroma Characteristics and Chemistry of Cascade Hops Used for Dry-Hopping. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, T.; Wanikawa, A.; Kono, K.; Shibata, K. Comparison of the Odor-Active Compounds in Unhopped Beer and Beers Hopped with Different Hop Varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 8855–8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takoi, K.; Tokita, K.; Sanekata, A.; Usami, Y.; Itoga, Y.; Koie, K.; Matsumoto, I.; Nakayama, Y. Varietal Difference of Hop-Derived Flavour Compounds in Late-Hopped/Dry-Hopped Beers. BrewingScience 2016, 69, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Dong, J.; Yin, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, R.; Wan, X.; Chen, P.; Hou, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, L. Wort Composition and Its Impact on the Flavour-Active Higher Alcohol and Ester Formation of Beer—A Review: Wort Composition and Impact on Higher Alcohol and Ester Formation. J. Inst. Brew. 2014, 120, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Féchir, M.; Dailey, J.W.; Buffin, B.; Russo, C.J.; Shellhammer, T.H. The Impact of Whirlpool Hop Addition on the Wort Metal Ion Composition and on the Flavor Stability of American Style Pale Ales Using Citra® Hop Extract and Pellets. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2022, 81, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczak, K.; Cioch-Skoneczny, M.; Duda-Chodak, A. Effects of Dry-Hopping on Beer Chemistry and Sensory Properties—A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langos, D.; Granvogl, M.; Schieberle, P. Characterization of the Key Aroma Compounds in Two Bavarian Wheat Beers by Means of the Sensomics Approach. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 11303–11311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Dancker, P.; Biendl, M.; Coelhan, M. Comparison of Polyfunctional Thiol, Element, and Total Essential Oil Contents in 32 Hop Varieties from Different Countries. Food Chem. 2024, 455, 139855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Stee, L.L.P.; Williams, J.; Beens, J.; Adahchour, M.; Vreuls, R.J.J.; Brinkman, U.A.; Lelieveld, J. Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography (GC × GC) Measurements of Volatile Organic Compounds in the Atmosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2003, 3, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Qian, M. Aroma Compounds in Oregon Pinot Noir Wine Determined by Aroma Extract Dilution Analysis (AEDA). Flavour Fragr. J. 2005, 20, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Shin, J.H.; Baek, H.H.; Lee, H.J. Volatile Flavour Compounds in Suspension Culture of Agastache rugosa Kuntze (Korean Mint). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2001, 81, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, P.R.; Miracle, E.R.; Krause, A.J.; Drake, M.; Cadwallader, K.R. Effect of Cold Storage and Packaging Material on the Major Aroma Components of Sweet Cream Butter. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 7840–7846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, U.F.; Borba, E.L.; Semir, J.; Marsaioli, A.J. A Simple Solid Injection Device for the Analyses of Bulbophyllum (Orchidaceae) Volatiles. Phytochemistry 1999, 50, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, A.; Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I. Essential Oil Composition of Achillea santolina L. and Achillea biebersteinii Afan. Collected in Jordan. Flavour Fragr. J. 2003, 18, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidorov, V.A.; Krajewska, U.; Dubis, E.N.; Jdanova, M.A. Partition Coefficients of Alkyl Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Esters in a Hexane–Acetonitrile System. J. Chromatogr. A 2001, 923, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarani, A.; Brand, G.; Dacremont, C.; Valentin, D.; Brochard, R. The Influence of Stimulus Concentration and Odor Intensity on Relaxing and Stimulating Perceived Properties of Odors. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 87, 104030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, A.D.; Mottram, D.S. Compounds Contributing to the Characteristic Aroma of Malted Barley. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1994, 42, 2880–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, J.G.; Rouseff, R.L.; Naim, M. GC−Olfactometric Characterization of Aroma Volatiles from the Thermal Degradation of Thiamin in Model Orange Juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3097–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I. Composition of the Essential Oils and in Vivo Emission of Volatiles of Four Lamium Species from Italy: L. purpureum, L. hybridum, L. bifidum and L. amplexicaule. Food Chem. 2005, 91, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, J.G.S.; Andrade, E.H.A.; Zoghbi, M.D.G.B. Volatile Constituents of the Leaves, Fruits and Flowers of Cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2000, 13, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Tsering, T.; Zhong, Y.; Nan, P. Chemical Composition of the Volatiles of Three Wild Bergenia Species from Western China. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.H.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Choi, H.-K.; Kim, K.-O.; Kim, Y.-S. Differentiation of Aroma Characteristics of Pine-Mushrooms (Tricholoma matsutake Sing.) of Different Grades Using Gas Chromatography−Olfactometry and Sensory Analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 2323–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, J.A.; Marbot, R.; Rosado, A.; Vázquez, C. Volatile Constituents of Malay Rose Apple [Syzygium malaccense (L.) Merr. & Perry]. Flavour Fragr. J. 2004, 19, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, J.; Marbot, R.; Rosado, A.; Vázquez, C. Volatile Constituents of Fruits of Garcinia dulcis Kurz. from Cuba. Flavour Fragr. J. 2003, 18, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetzos, C.; Angelopoulou, D.; Perdetzoglou, D. A Comparative Study of the Essential Oils of Cistus salviifolius in Several Populations of Crete (Greece). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2002, 30, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I.; Bader, A. Essential Oils of the Aerial Parts of Three Salvia Species from Jordan: Salvia lanigera, S. spinosa and S. syriaca. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 732–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, V.; Dorizas, N.; Kypriotakis, Z.; Skaltsa, H.D. Analysis of the Essential Oil Composition of Eight Anthemis Species from Greece. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1104, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissbecker, B.; Holighaus, G.; Schutz, S. Gas Chromatography with Mass Spectrometric and Electroantennographic Detection: Analysis of Wood Odorants by Direct Coupling of Insect Olfaction and Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1056, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonella, V.; Rosa, G.; Zappalà, M.; Cotroneo, A. Essential Oil Composition of Different Cultivars of Bergamot Grown in Sicily. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2000, 12, 493–501. [Google Scholar]

- Ruther, J. Retention Index Database for Identification of General Green Leaf Volatiles in Plants by Coupled Capillary Gas Chromatography−mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 890, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidnia, K.; Miri, R.; Kamalinejad, M.; Khazraii, H. Chemical Composition of the Volatile Oil of Aerial Parts of Valeriana sisymbriifolia Vahl. Grown in Iran. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 516–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidnia, K.; Miri, R.; Kamalinejad, M.; Nasiri, A. Composition of the Essential Oil of Salvia mirzayanii Rech. f. & Esfand from Iran. Flavour Fragr. J. 2002, 17, 465–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaltsa, H.D.; Mavrommati, A.; Constantinidis, T. A Chemotaxonomic Investigation of Volatile Constituents in Stachys subsect. Swainsonianeae (Labiatae). Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saroglou, V.; Marin, P.D.; Rancic, A.; Veljic, M.; Skaltsa, H. Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oil of Six Hypericum Species from Serbia. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2007, 35, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zorn, H.; Krings, U.; Berger, R.G. Volatiles from Submerged and Surface-cultured Beefsteak Fungus, Fistulina hepatica. Flavour Fragr. J. 2007, 22, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.-X.; Zhao, C.-X.; Liang, Y.-Z.; Yang, H.; Fang, H.-Z.; Yi, L.-Z.; Zeng, Z.-D. Comparative Analysis of Volatile Components from Clematis Species Growing in China. Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 595, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Fu, C.; Chen, S. Essential Oil of Actinidia macrosperma, a Catnip Response Kiwi Endemic to China. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. B 2006, 7, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flamini, G.; Tebano, M.; Cioni, P.L. Volatiles Emission Patterns of Different Plant Organs and Pollen of Citrus limon. Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 589, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, D.H.M.; Ishimoto, E.Y.; Ortiz, M.; Marques, M.; Fernando Ferri, A.; Torres, E.A.F.S. Essential Oil and Antioxidant Activity of Green Mate and Mate Tea (Ilex paraguariensis) Infusions. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Ho, C.; Wang, E.I. Analysis of Leaf Essential Oils from the Indigenous Five Conifers of Taiwan. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandreou, V.; Magiatis, P.; Chinou, I.; Kalpoutzakis, E.; Skaltsounis, A.-L.; Tsarbopoulos, A. Volatiles with Antimicrobial Activity from the Roots of Greek Paeonia Taxa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 81, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, J.; Marbot, R.; Vázquez, C. Volatile Components of the Fruits of Vangueria madagascariensis J. F. Gmel. from Cuba. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2004, 16, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulović, N.; Mišić, M.; Aleksić, J.; Đoković, D.; Palić, R.; Stojanović, G. Antimicrobial Synergism and Antagonism of Salicylaldehyde in Filipendula vulgaris Essential Oil. Fitoterapia 2007, 78, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulović, N.; Lazarević, J.; Ristić, N.; Palić, R. Chemotaxonomic Significance of the Volatiles in the Genus Stachys (Lamiaceae): Essential Oil Composition of Four Balkan Stachys Species. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2007, 35, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagojević, P.; Radulović, N.; Palić, R.; Stojanović, G. Chemical Composition of the Essential Oils of Serbian Wild-Growing Artemisia absinthium and Artemisia vulgaris. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4780–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karioti, A.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D.; Mensah, M.L.K.; Fleischer, T.C.; Skaltsa, H. Composition and Antioxidant Activity of the Essential Oils of Xylopia aethiopica (Dun) A. Rich. (Annonaceae) Leaves, Stem Bark, Root Bark, and Fresh and Dried Fruits, Growing in Ghana. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 8094–8098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carunchia Whetstine, M.E.; Cadwallader, K.R.; Drake, M. Characterization of Aroma Compounds Responsible for the Rosy/Floral Flavor in Cheddar Cheese. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3126–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Beer ID | Hop Profile | Group Name |

|---|---|---|

| SC1 | Citra | Single Hop, Citra |

| SC2 | Citra | |

| SC3 | Citra | |

| SC4 | Citra | |

| SC5 | Citra | |

| MC1 | Citra, Mosaic | Multiple Hops, with Citra |

| MC2 | Citra, Mosaic | |

| MC3 | Citra, Mosaic | |

| MC4 | Citra, Simcoe, Idaho 7 | |

| MC5 | Citra, Galaxy | |

| SO1 | Mosaic | Single Hop, Other |

| SO2 | Strata | |

| SO3 | Galaxy | |

| SO4 | Mosaic | |

| SO5 | Strata | |

| MO1 | Sabro, El Dorado, El Dorado Cryo 1 | Multiple Hops, without Citra |

| MO2 | Idaho 7, Mosaic, Enigma | |

| MO3 | Galaxy, Ekuanot | |

| MO4 | Idaho 7, Ella | |

| MO5 | El Dorado, Amarillo |

| Cpd Index | Compounds | Single Hop, Citra | Multiple Hops, with Citra | Single Hop, Other | Multiple Hops, Without Citra | CCA Corr | Exp. RI Idx | Lit. RI Idx | Ref | Aroma Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esters | ||||||||||

| 76 | Isoamyl acetate | a | a | b | b | 1 | 876 | 876 | [32] | Fruity, banana, pear-drop |

| 77 | 2-Methylbutyl acetate | ab | a | ab | b | 1 | 879 | 877 | [33] | Fruity, sweet, apple/banana |

| 80 | Ethyl pentanoate | b | ab | ab | a | 1 | 902 | 898 | [34] | Fruity, apple |

| 128 | 2-Methylbutyl isobutyrate | c | a | ab | b | 2 | 1014 | 1014 | [35] | Fruity, sweet |

| 130 | Isoamyl isobutyrate | c | a | b | b | 2 | 1018 | 1018 | [35] | Fruity, banana, pear |

| 165 | Ethyl heptanoate | b | a | ab | b | 2 | 1100 | 1095 | [36] | Fruity, pineapple |

| 171 | 2-Me-2-methylbutanoate | b | ab | ab | a | 1–2 | 1110 | 1107 | [37] | Fruity, green |

| 208 | Ethyl benzoate | ab | b | ab | a | 1 | 1170 | 1171 | [34] | Minty, fruity |

| 227 | Ethyl nicotinate | a | b | ab | b | 2 | 1216 | 1224 | [38] | Warm, sweet, tobacco-like |

| 237 | Ethyl phenylacetate | b | ab | ab | a | 1 | 1245 | 1244 | [36] | Floral, honey |

| 242 | 2-Phenylethyl acetate | a | ab | b | ab | none | 1257 | 1245 | [39] | Honeyed, rosy, sweet |

| 269 | Ethyl hydrocinnamate | a | b | ab | a | 1–2 | 1349 | 1350 | [40] | Sweet, floral, honey, balsamic |

| 293 | Ethyl cinnamate | a | b | ab | a | 2 | 1466 | 1474 | [40] | Sweet, balsamic, cinnamon |

| 267 | Methyl geranate | a | a | b | b | 1 | 1325 | 1326 | [41] | Floral, citrus–herbal |

| Terpenes | ||||||||||

| 119 | β-Myrcene | a | a | a | a | 2 | 993 | 992 | [42] | Green, resinous, balsamic |

| 139 | β-Ocimene | b | ab | b | a | 1–2 | 1049 | 1041 | [43] | Green, citrus, herbal |

| 240 | Piperitone | b | b | b | a | 1 | 1254 | 1250 | [44] | Minty, herbal |

| 287 | Caryophyllene | ab | ab | b | a | 2 | 1421 | 1420 | [42] | Woody, spicy, clove-like |

| 304 | d-Cadinene | b | ab | b | a | 1–2 | 1525 | 1528 | [45] | Herbal |

| 313 | Caryophyllenyl alcohol | ab | b | ab | a | 1 | 1572 | - | [46] | Woody, spicy |

| 320 | Humulol | a | b | b | ab | none | 1604 | 1610 | [47] | Woody, hops |

| 323 | epi-Cubenol | b | b | b | a | 1 | 1617 | 1619 | [48] | Woody, herbal |

| 326 | Cubenol | b | b | b | a | 1 | 1631 | 1642 | [49] | Woody, warm, spicy |

| 330 | t-Muurolol | b | b | b | a | 1 | 1643 | 1640 | [50] | Woody, earthy |

| 335 | β-Eudesmol | b | b | b | a | 1 | 1653 | 1645 | [50] | Woody, earthy, sweet |

| 334 | α-Cadinol | b | b | ab | a | 1 | 1658 | 1650 | [50] | Woody, herbal, sweet |

| 345 | (E,E)-Farnesol | a | ab | c | bc | 1 | 1724 | 1722 | [51] | Floral, sweet, mild citrus |

| Ketones | ||||||||||

| 161 | 2-Nonanone | a | a | a | a | none | 1093 | 1092 | [52] | Fatty, green, fruity |

| 217 | 2-Decanone | b | a | ab | ab | 2 | 1193 | 1194 | [53] | Fatty, waxy, citrus peel |

| 258 | 2-Undecanone | b | a | ab | b | 2 | 1294 | 1294 | [41] | Herbal, minty, orange |

| 324 | Benzophenone | ab | b | ab | a | 1 | 1627 | 1621 | [36] | Sweet, balsamic; fixative |

| 14 | 2-Butanone | b | ab | ab | a | 1 | <900 | - | - | Solvent-like, sweet |

| 112 | 6-Methyl-5-heptene-2-one | a | ab | b | a | none | 988 | 988 | [42] | Citrus, green, metallic |

| Other | ||||||||||

| 110 | 1-Octen-3-ol | ab | c | bc | a | 1 | 981 | 983 | [32] | Mushroom, earthy, green |

| 261 | 2-Undecanol | b | ab | ab | a | 1 | 1303 | 1303 | [54] | Fatty, waxy, citrus peel |

| 185 | Phenylethyl Alcohol | b | b | b | a | 1 | 1117 | 1114 | [34] | Rose-like, floral, honey |

| 91 | Isobutyric acid | a | a | a | a | 2 | 915 | 914 | [47] | Sweaty, rancid, cheesy |

| 193 | Heptanoic acid | b | a | ab | ab | 2 | 1103 | 1109 | [55] | Oily, rancid, cheesy |

| 272 | γ-Nonanolactone | ab | b | ab | a | 1 | 1362 | 1362 | [41] | Coconut, creamy, peach |

| 190 | 2,3,5-Trithiahexane | b | a | a | a | 2 | 1123 | 1134 | [47] | Sulfurous, alliaceous |

| 97 | S-methyl thio-3-methylbutyrate | b | a | b | b | 2 | 938 | 938 | [37] | Sulfurous, onion, meat |

| Unknown | ||||||||||

| 117 | unk Ri-995 | b | ab | ab | a | 1 | 995 | - | - | - |

| 149 | unk Ri-1072 | b | b | ab | a | 1 | 1072 | - | - | - |

| 189 | unk Ri-1095 | b | ab | ab | a | 2 | 1095 | - | - | - |

| 195 | unk Ri-1157 | a | a | b | a | 2 | 1141 | - | - | - |

| 199 | unk Ri-1141 | ab | a | b | a | 2 | 1141 | - | - | - |

| 205 | unk Ri-1162 | b | a | ab | a | 1–2 | 1162 | - | - | - |

| 213 | unk Ri-1185 | a | a | a | a | 1 | 1185 | - | - | - |

| 248 | unk Ri-1278 | b | a | ab | ab | 2 | 1278 | - | - | - |

| 307 | unk Ri-1525 | a | a | a | a | 1 | 1525 | - | - | - |

| 308 | unk Ri-1514 | b | a | b | a | 2 | 1514 | - | - | - |

| 311 | unk Ri-1545 | b | b | ab | a | 1 | 1545 | - | - | - |

| 312 | unk Ri-1566 | ab | b | ab | a | 1 | 1566 | - | - | - |

| 317 | unk Ri-1578 | b | b | b | a | 1–2 | 1578 | - | - | - |

| 325 | unk Ri-1635 | b | b | b | a | 1 | 1635 | - | - | - |

| 341 | unk Ri-1661 | b | ab | ab | a | 1–2 | 1662 | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frost, S.C.; Laing, S.J.; Robbat, A., Jr.; Orians, C.M. The Volatile Composition of Commercially Available New England India Pale Ales as Defined by Hop Blending. Beverages 2025, 11, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060167

Frost SC, Laing SJ, Robbat A Jr., Orians CM. The Volatile Composition of Commercially Available New England India Pale Ales as Defined by Hop Blending. Beverages. 2025; 11(6):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060167

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrost, Scott C., Serena J. Laing, Albert Robbat, Jr., and Colin M. Orians. 2025. "The Volatile Composition of Commercially Available New England India Pale Ales as Defined by Hop Blending" Beverages 11, no. 6: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060167

APA StyleFrost, S. C., Laing, S. J., Robbat, A., Jr., & Orians, C. M. (2025). The Volatile Composition of Commercially Available New England India Pale Ales as Defined by Hop Blending. Beverages, 11(6), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060167