Abstract

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders represent chronic degenerative musculoskeletal conditions with a high prevalence in the general population and limited regenerative treatment options. Owing to the insufficient efficacy of current conservative and surgical therapies, there is a growing clinical need for biologically based regenerative approaches. Tissue engineering (TE), particularly scaffold-based strategies, has emerged as a promising avenue for TMJ regeneration. This systematic review analyzed preclinical in vivo studies investigating scaffold-based interventions for TMJ disc and osteochondral repair. A structured literature search of PubMed and Scopus databases identified 39 eligible studies. Extracted data included scaffold composition, use of cellular and bioactive components, animal models, and reported histological, radiological, and functional outcomes. Natural scaffolds, such as decellularized extracellular matrix and collagen-based hydrogels, demonstrated favorable biocompatibility and support for fibrocartilaginous regeneration, whereas synthetic materials including polycaprolactone, poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid), and polyvinyl alcohol provided superior mechanical stability and structural tunability. Cells were used in 17/39 studies (43%); quantitative improvements were variably reported across these studies. Bioactive molecule delivery, including transforming growth factor-β, histatin-1, and platelet-rich plasma, further enhanced tissue regeneration, while emerging drug- and gene-delivery approaches showed potential for modulating local inflammation. Despite encouraging results, the reviewed studies exhibited substantial heterogeneity in experimental design, outcome measures, and animal models, limiting direct comparison and translational interpretation. Scaffold-based approaches show preclinical promise but heterogeneity in design and incomplete quantitative reporting limit definitive conclusions. Future research should emphasize standardized methodologies, long-term functional evaluation, and the use of clinically relevant large-animal models to facilitate translation toward clinical application. However, functional and biomechanical outcomes were inconsistently reported and rarely standardized, preventing robust conclusions regarding the relationship between structural regeneration and restoration of TMJ function.

1. Introduction

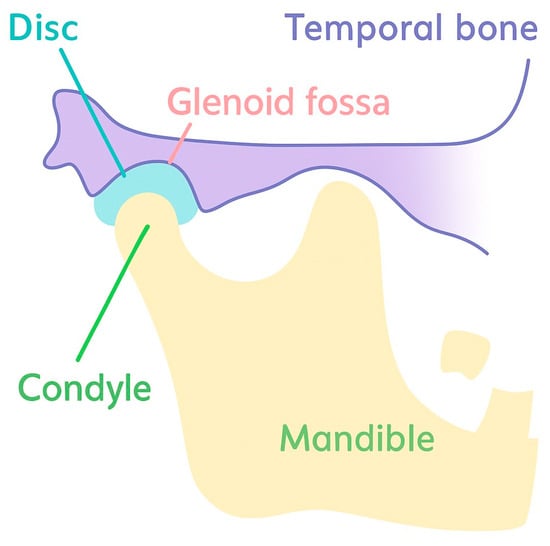

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a synovial joint that connects the mandibular condyle with the temporal bone at the glenoid fossa, with a biconcave fibrocartilaginous articular disc interposed between them (Figure 1) [1,2,3]. This disc–condyle–fossa complex enables smooth mandibular movements under high and heterogeneous mechanical loads, while the compact anatomy and limited intrinsic healing capacity make TMJ tissues particularly susceptible to degeneration [1,2,3].

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of TMJ anatomy.

Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) represent a group of chronic degenerative musculoskeletal conditions affecting the TMJ and associated musculature and are highly prevalent in the general population [4,5]. Their etiology is multifactorial and includes trauma, anatomical variations, and muscle hyperactivity [6,7]. Clinically, TMDs commonly manifest as joint clicking, restricted mandibular motion, myofascial pain, and headaches, while more severe symptoms such as trismus and pain during mouth opening and chewing have been linked to degenerative and osteoarthritic changes in the mandibular condyle, particularly following disc perforation [8,9]. Together, these features contribute to a substantial reduction in quality of life due to chronic pain, functional limitations, and impaired mastication [8,9].

Current treatment strategies initially rely on conservative approaches, including occlusal splints, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, lifestyle modification, exercises, and diet restrictions [8,9]. Although these modalities may relieve symptoms and slow progression in selected patients, a considerable proportion of cases ultimately require surgical intervention. Surgical options include discectomy, placement of autologous or alloplastic grafts, and total joint replacement [10,11,12,13]. However, discectomy may shift the joint toward a more degenerative state, and interposition grafting introduces additional surgery with donor-site morbidity and potential limitation of jaw motion due to scar formation; autogenous grafts have also been associated with graft resorption, functional limitations, and poor long-term outcomes [10,11,12,13]. In the absence of reliable regenerative solutions, many end-stage patients undergo total joint arthroplasty, which adds further clinical and socioeconomic burden [10,11,12,13].

Accordingly, there is a clear need for regenerative therapeutic approaches that can bridge the gap between minimally invasive treatment and terminal surgical procedures. Tissue engineering (TE) has emerged as a promising strategy for restoring TMJ integrity by combining biomaterial scaffolds with biological cues to support cell adhesion, proliferation, and extracellular matrix formation [14,15,16,17]. Nevertheless, the TMJ remains one of the most challenging anatomical targets for regeneration due to its constrained surgical accessibility, limited vascularization, and demanding mechanical environment, which together impose strict requirements on scaffold biocompatibility, degradation, and mechanical performance [14,15,16,17].

Recent preclinical work has reported regeneration of fibrocartilaginous tissues, including the TMJ disc, using scaffold-based approaches with both natural and synthetic biomaterials [18,19,20]. However, the complex structure and function of the TMJ disc and osteochondral unit require scaffolds with carefully balanced biomechanical and biological properties to withstand mandibular movements and masticatory forces, while maintaining an environment conducive to stable matrix deposition and tissue integration [8,14,15,16,17]. In addition, scaffold platforms are increasingly designed as tunable systems, allowing adjustment of biochemical and mechanical characteristics and serving as delivery vehicles for cells and growth factors [21]. Despite this rapid progress, there is still no consensus regarding which scaffold type or cell-loading strategy yields the most consistent regenerative outcomes across preclinical TMJ models [14,15,16,17].

Therefore, the aim of the present systematic review was to critically synthesize preclinical in vivo evidence on scaffold-based TE strategies for TMJ disc and osteochondral regeneration. By analyzing scaffold types, cellular and bioactive components, animal models, and reported outcomes, this review seeks to identify reproducible patterns, clarify current limitations, and inform future translational research in TMJ regeneration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Registration

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. This systematic review was registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/H3W7K). The review protocol was defined as a priori to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility.

2.2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed in April 2025 using PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases. Studies published between 1988 and April 2025 were considered eligible. The search strategy combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free-text keywords related to temporomandibular joint regeneration and tissue engineering, including: “temporomandibular joint” OR “TMJ” AND “tissue engineering” OR “scaffold” OR “regeneration” AND “animal model” OR “preclinical” OR “in vivo”.

The search was limited to studies published in English. All retrieved records were imported into EndNote software (version 20.5, Clarivate Analytics), where duplicate entries were identified and removed prior to screening.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria were defined before study selection and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria for Study Selection - Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two authors independently screened titles and abstracts of all identified records. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were subsequently assessed for inclusion. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

For each included study, the following data were extracted: authorship and publication year; animal species and strain; number of animals; defect type and location; scaffold material and composition; use of cells and/or bioactive molecules; follow-up duration; evaluation methods (e.g., histology, imaging, biomechanical testing); and reported outcomes. Full study-level data extraction (raw numeric values, mean ± SD where available, and timepoints) is provided as Supplementary Table S3.

2.5. Risk of Bias and Methodological Quality Assessment

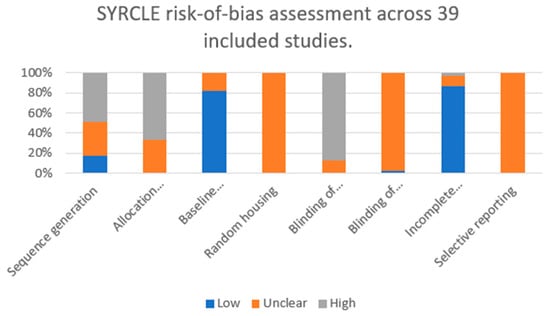

The risk of bias and methodological quality of the included studies were independently assessed by the authors using a modified version of the SYRCLE (Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal Experimentation) Risk of Bias tool, which is specifically designed for preclinical in vivo studies. The assessment included sequence generation, allocation concealment, baseline comparability, random housing, blinding of investigators and outcome assessors, completeness of outcome data, and selective outcome reporting.

Any discrepancies in assessment were resolved through group discussion. For each domain, studies were classified as having low, unclear, or high risk of bias, and the distribution of these judgments across all 39 studies was summarized using descriptive statistics and visualized as a stacked bar chart.

2.6. Data Synthesis and Quantitative Heterogeneity Assessment

Data were extracted in full (means, standard deviations, group sizes, and timepoints) when reported; the complete extraction is provided in Supplementary Table S1 (Excel/CSV). For outcomes reported by ≥3 studies with comparable continuous metrics we planned exploratory random-effects analyses and calculation of between-study heterogeneity (I2). Where continuous data or consistent metrics were unavailable, we performed quantitative summaries of data availability (number and proportion of studies reporting mean ± SD for each outcome) and descriptive subgroup counts by target tissue, animal species, defect type, scaffold class, cell/GF use and follow-up category. Pre-specified subgroup analyses/meta-regressions included animal species (rodent/rabbit/large), defect model (perforation/partial discectomy/total discectomy/osteochondral/condylectomy), scaffold class (natural/synthetic/hybrid) and follow-up (≤4 wks/4–12 wks/>12 wks). If fewer than three comparable continuous effect estimates were available for any subgroup, pooling was not performed, and the rationale is reported. The results were structured according to scaffold type, use of cellular and bioactive components, and targeted TMJ tissue (articular disc or osteochondral region).

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus in April 2025. Articles published between 1988 and April 2025 were included in the search. The search strategy included a combination of MeSH terms and free-text keywords related to temporomandibular joint (TMJ), tissue engineering, scaffolds, growth factors, and animal models. The detailed search syntax is provided below: (“temporomandibular joint” OR “TMJ”) AND (“tissue engineering” OR “scaffolds” OR “regeneration”) AND (“animal model” OR “preclinical” OR “in vivo”).

Searches were limited to studies published in English. All identified citations were imported into EndNote software (version 20.5, Clarivate Analytics) for reference management and removal of duplicates. If fewer than three comparable continuous effect estimates were available for any subgroup, pooling was not performed, and the rationale is reported.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

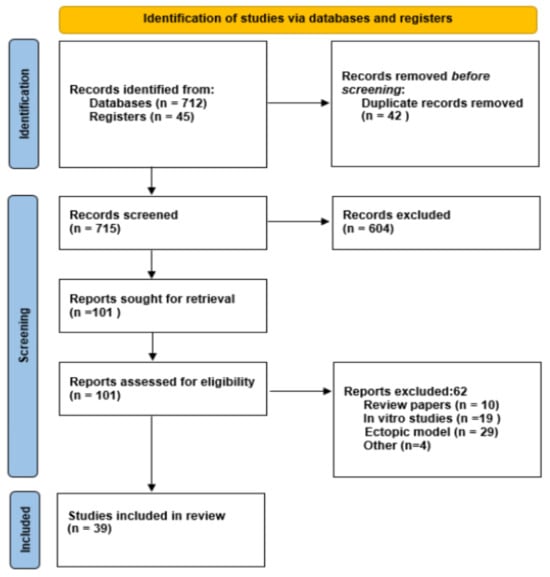

A total of 757 records were identified, and 39 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. The study selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2) [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection process.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

The 39 included studies were all preclinical in vivo trials evaluating scaffold-based tissue engineering strategies for the TMJ regeneration. Most studies used rabbits (19/39), with follow-up time from 1 week to 12 months. Other animal models included goats (6/39), rodents (6/39), dogs (3/39), sheep (3/39) and mini-pigs (1/39). Observation times varied between species: rats (2–12 weeks), rabbits (1 week to 12 months), goats (12–24 weeks) and sheep (4 months). Data availability: 22/39 studies (56%) provided at least one extractable quantitative outcome (mean ± SD or clear numeric timecourse); 17/39 (44%) provided only qualitative or semi-quantitative data (Supplementary Table S3).” “Cells were used in 17/39 studies (43%); growth factors or other bioactives were used in 14/39 studies (36%).

An overview of study characteristics is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of revised articles.

3.3. Study Objectives

Of the included studies 16 evaluated TMJ disc regeneration or replacement,21 studies focused on osteochondral regeneration in the condylar region, and 2 studies investigated drug delivery systems for TMJ regeneration.

In osteochondral models, regeneration was assessed either after surgically created defects in the mandibular condyle or following condylectomy (Table 2).

3.4. Evaluation Methods

The diagnostic modalities used for characterizing the new bone formation included micro-CT examination, histology, immunohistochemistry, real-time PCR, fluorescence microscopy, biomechanical testing, and scanning electron microscopy.

3.5. Scaffold Types

All studies utilized scaffolds as the central experimental component or as delivery platforms for cells and/or bioactive substances. Most studies used synthetic polymer in the form of hydrogels (n = 17), in comparison to natural hydrogel scaffolds (n = 13) (Table 2).

3.6. Bioactive Molecules and Cell Therapies

Bioactive molecules were used in 14 studies (36%), either alone or in combination with a scaffold or cell therapy (Table 2). The most common growth factor was TGF-β and BMP-2. Several studies reported using various concentrations of growth factors for bone regeneration.

Cell therapies were used for TMJ regeneration in 17 studies (43%). Bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) were mostly used to promote osteochondral regeneration. Dental-pulp-derived stem cells (DPSCs) were used in 2 studies.

A detailed overview is provided in Table 2.

Overall, the included studies demonstrate promising preclinical outcomes, but substantial methodological heterogeneity limits the ability to perform quantitative synthesis.

3.7. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

The methodological quality of the included animal studies was evaluated using a modified version of the Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal Experimentation (SYRCLE) Risk of Bias tool, which is specifically designed to assess bias in preclinical in vivo experiments. The following domains were considered: sequence generation, allocation concealment, baseline characteristics, blinding of investigators and outcome assessors, random housing, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting.

For each of the eight SYRCLE domains, we quantified the number and proportion of studies judged as low, unclear, or high risk of bias (Figure 3). Across the 39 included studies, sequence generation (randomization) was most frequently rated as high risk (19/39, 48.7%), with only 7 studies (17.9%) judged as low risk and 13 (33.3%) as unclear. Allocation concealment showed an even less favorable profile, with no study meeting low-risk criteria (0/39, 0%), while 13 (33.3%) were classified as unclear and 26 (66.7%) as high risk.

Figure 3.

Domain-level risk-of-bias assessment of the 39 included preclinical in vivo studies according to the SYRCLE tool. Bars represent the proportion of studies rated as low (blue), unclear (orange), or high (grey) risk of bias for each domain (sequence generation, allocation concealment, baseline comparability, random housing, blinding of investigators, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting).

In contrast, baseline comparability between experimental groups was predominantly adequate, with 32/39 studies (82.1%) rated as low risk and 7/39 (17.9%) as unclear, and none classified as high risk. Random housing was not explicitly reported in any of the studies and was therefore uniformly judged as unclear risk (39/39, 100%).

Blinding of investigators was frequently rated as high risk (34/39, 87.2%). Blinding of outcome assessors was almost never clearly reported: 1/39 (2.6%) low risk, 38/39 (97.4%) unclear.

Conversely, incomplete outcome data represented a methodological strength of the included literature, with 34/39 studies (87.2%) judged as low risk, 4/39 (10.3%) as unclear, and only 1/39 (2.6%) as high risk. Selective outcome reporting could not be reliably assessed due to the lack of preregistered protocols; all 39 studies (100%) were therefore rated as unclear risk in this domain.

Taken together, these findings indicate that the most frequently violated or insufficiently reported domains were allocation concealment and blinding of investigators, whereas baseline comparability and completeness of outcome data were generally well addressed. Detailed descriptions of study designs, animal models, scaffold types, and interventions for each of the 39 included studies are shown in Table 2, whereas the aggregated domain-level risk-of-bias judgments are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 3.

Table 3.

SYRCLE risk-of-bias summary.

Study-level risk-of-bias judgments for each domain are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

3.8. Heterogeneity Assessment and Data Availability

The full extracted dataset is provided as Supplementary Table S3. Overall, 22/39 studies (56%) reported at least one extractable quantitative outcome (mean ± SD or clear numeric time-course); 17/39 (44%) provided only qualitative or semi-quantitative data. Summary counts (see Supplementary Table S3):

Target tissue: Disc 16, Osteochondral/condyle 21, Drug delivery 2.

Animal groups: Small rodents 6, Rabbits 19, Large animals (goat/sheep/pig/dog) 14.

Scaffold class: Synthetic 17, Natural 13, Hybrid 9.

Studies reporting cells: 17/39 (43%); reporting growth factors/bioactives: 14/39 (36%). When we inspected specific outcomes (histological scores, μCT bone metrics, biomechanical tests), fewer than three studies reported the same continuous outcome metric within the same tissue/animal/defect subgroup for most comparisons. For example, only two rabbit osteochondral GelMA studies reported comparable μCT BV/TV metrics. Biomechanical outcomes with mean ± SD were present in only five studies across heterogeneous species and tests. We therefore constructed a data-availability matrix (Supplementary Table S3) listing the number of studies with extractable mean ± SD for each outcome by subgroup; this matrix documents the precise gaps that precluded reliable pooled analyses. Exploratory meta-analysis was planned a priori but no prespecified subgroup met the n ≥ 3 and metric-consistency criteria for a primary pooled analysis; where n ≥ 3 homogeneous estimates are identified later, these data are provided to enable future pooling.

3.9. Functional and Biomechanical Outcomes

Across the 39 included studies, functional and biomechanical assessment of regenerated TMJ tissues was inconsistently reported. Eighteen of 39 studies (≈46%) described at least one functional or biomechanical outcome (e.g., joint kinematics, mastication-related behavior, or ex vivo mechanical testing of regenerated tissues).

Where reported, functional outcomes included joint kinematics (e.g., range and symmetry of mandibular motion) in large-animal disc replacement models, qualitative or semi-quantitative assessments of chewing behavior, and, more rarely, measurements related to jaw opening or mastication patterns in rodent models of TMJ inflammation. Biomechanical testing most commonly involved ex vivo measurement of compressive or tensile properties of native or regenerated discs and osteochondral constructs (e.g., elastic modulus, stiffness, failure load), comparison of the mechanical behavior of decellularized or synthetic scaffolds to native tissues, or time-dependent changes in scaffold/tissue mechanical performance.

However, the specific parameters, testing protocols, and reporting formats varied substantially between studies. For most combinations of tissue type, animal model, and defect configuration, fewer than three studies reported the same biomechanical metric with comparable methodology, and standardized functional endpoints such as maximal interincisal opening, lateral excursions, bite force, or quantitative mastication efficiency were rarely measured. As a result, we were unable to perform pooled analyses of functional restoration or to formally test correlations between functional and structural (histological or radiological) regeneration.

4. Discussion

This systematic review synthesizes preclinical evidence on scaffold-based tissue engineering (TE) strategies for regeneration of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) structures [16,61,62,63,64]. Overall, the findings indicate that scaffold-based approaches can support disc and osteochondral regeneration under experimental conditions; however, regenerative success is highly dependent on scaffold design, biological augmentation, and model-specific factors. Importantly, while numerous studies report favorable histological outcomes, robust functional restoration and long-term durability remain insufficiently demonstrated, underscoring the persistent translational gap between experimental feasibility and clinically reliable TMJ regeneration [16,26]. In our dataset, functional and biomechanical outcomes were reported in less than half of the included studies, and even when present, they were rarely standardized or quantitatively comparable. Only a small subset of studies provided mean ± SD values for biomechanical properties (e.g., tensile or compressive modulus, stiffness, failure load) or for clinically relevant functional surrogates such as jaw kinematics or mastication-related behavior. Moreover, no study systematically combined quantitative functional measurements (e.g., maximal interincisal opening, lateral excursions, bite force, or mastication efficiency) with detailed structural assessment in a way that would allow robust evaluation of whether functional restoration tracks with histological or radiological regeneration. This fragmented and heterogeneous reporting represents a critical analytical gap and likely explains why encouraging structural findings have not yet translated into predictable clinical functional benefits.

4.1. TMJ Articular Disc Regeneration

Among TMJ components, the articular disc has received particular attention due to its essential biomechanical role and limited intrinsic healing capacity [1,2,3,4,5]. Across the included studies, both natural and synthetic scaffolds demonstrated the ability to support fibrocartilaginous regeneration, although outcomes were variable and strongly influenced by scaffold composition and experimental models.

Natural scaffolds, particularly decellularized extracellular matrix (ECM) and collagen-based hydrogels, consistently exhibited favorable biocompatibility and integration with surrounding tissues. Several studies reported formation of fibrocartilage-like tissue with improved cellular organization and extracellular matrix deposition following implantation of ECM-derived or collagen-based constructs, especially in rabbit, canine, and goat models [22,24,27,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Nevertheless, the limited mechanical strength of natural scaffolds, together with variable degradation rates and potential immunogenicity, remains a critical limitation in the load-bearing TMJ environment [14,16,17].

Synthetic scaffolds offered improved reproducibility and tunable mechanical properties. Materials such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polycaprolactone (PCL), and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) demonstrated enhanced resistance to joint loading and more predictable degradation behavior [23,25,26]. Importantly, composite scaffolds incorporating controlled release of growth factors, such as connective tissue growth factor and transforming growth factor-β, resulted in superior regenerative outcomes compared with scaffold-only approaches [29,37]. These findings emphasize the importance of biomimetic scaffold design and spatiotemporal bioactive signaling. In contrast, purely synthetic constructs lacking biological augmentation frequently failed to achieve complete functional restoration and, in some cases, induced degenerative changes [25].

Disc regeneration outcomes were also strongly influenced by the defect model. Studies employing disc perforation models differed substantially from those using partial or total discectomy, while spontaneous healing varied across animal species [29,34]. The absence of clearly defined critical-size defect models for TMJ disc injury represents a major limitation in the current literature and hinders direct comparison between studies [29,34].

Taken together, available preclinical data suggest that neither natural nor synthetic scaffolds alone consistently ensure predictable TMJ disc regeneration; this interpretation is limited by heterogeneous and largely non-comparable outcome reporting (see Supplementary Table S3). Hybrid constructs that combine mechanical stability with controlled biological signaling appear most promising; however, the lack of standardized defect models and functional outcome measures precludes definitive conclusions regarding optimal scaffold design.

4.2. Osteochondral Regeneration of the Mandibular Condyle

Osteochondral regeneration of the mandibular condyle represents an equally complex challenge in TMJ tissue engineering [2,3,4,5,6]. Injectable hydrogels have emerged as particularly attractive platforms due to their minimally invasive application, adaptability to irregular articular surfaces, and capacity for local delivery of cells and bioactive agents [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75].

Multiple studies demonstrated that scaffolds seeded with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), particularly bone marrow-derived MSCs, significantly enhanced cartilage and subchondral bone regeneration [43,44,46,47,50,76,77,78]. Improved outcomes were generally attributed to enhanced chondrogenic differentiation, modulation of the inflammatory microenvironment, and improved integration with host tissue. However, regenerative efficacy varied across studies, and inconsistent results—particularly those involving alternative stem cell sources such as dental pulp stem cells [79]—suggest that successful regeneration depends on complex interactions between cell type, scaffold properties, and local mechanical conditions [38,42].

Biofunctionalization of scaffolds with growth factors or signaling peptides further improved osteochondral repair. Histatin-1-functionalized scaffolds and platelet-rich plasma–enriched hydrogels promoted angiogenesis, cell recruitment, and matrix remodeling in several models [39,40,50]. In contrast, the role of potent osteogenic factors such as bone morphogenetic protein-2 remains controversial, as inconsistent cartilage outcomes and the risk of ectopic ossification highlight the need for precise control of dosing, localization, and release kinetics [53,55,57].

Collectively, these findings indicate that osteochondral regeneration of the mandibular condyle is feasible in preclinical models, particularly when cell-based strategies are employed. Nevertheless, inconsistent outcomes across studies demonstrate that biological augmentation cannot compensate for suboptimal scaffold mechanics or inadequate experimental design.

4.3. Comparative Performance of Cell-Based and Acellular Approaches

Cells were used in 17/39 studies (43%), most frequently bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), followed by adipose-derived stem cells, dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs), and chondrocytes. Across osteochondral and cartilage models, BMSC-seeded scaffolds generally showed improved histological scores, more mature cartilage and subchondral bone, and in some cases better μCT parameters compared with acellular scaffolds. However, reporting of continuous outcomes (mean ± SD) was inconsistent, and few studies used identical scoring systems, which precluded quantitative pooling of effect sizes. DPSCs were used in only two studies, both suggesting early benefits on cellularity and matrix deposition but without sufficient, standardized outcome data to compare their efficacy directly with BMSCs. Overall, the current evidence supports the use of MSC-based strategies over acellular scaffolds in terms of qualitative regeneration, but the small number of homogeneous datasets and heterogeneous outcome measures prevents robust ranking of specific cell sources.

4.4. Scaffold-Based Drug Delivery Strategies

Scaffold-based drug delivery systems have emerged as an innovative approach for addressing the inflammatory component of temporomandibular disorders [59,60]. Compared with conventional intra-articular injections, hydrogel-based delivery platforms enable sustained local release while potentially reducing the need for repeated interventions. Preclinical studies utilizing siRNA-loaded PLGA microparticles or naproxen-loaded lipid carriers demonstrated effective suppression of inflammatory cytokines and reduced leukocyte infiltration in experimental TMJ models [59,60]. Although these strategies primarily target inflammation rather than structural regeneration, they may serve as valuable adjuncts within broader regenerative treatment paradigms.

4.5. Growth Factors, Bioactive Molecules, and Delivery Strategies

Growth factors and other bioactive molecules were incorporated in 14/39 studies (36%), most commonly transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2), histatin-1, NELL-1, fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), and platelet-rich plasma (PRP). In general, biofunctionalization of scaffolds with these agents improved histological appearance of cartilage and subchondral bone, as well as μCT and molecular readouts, when compared with scaffold-only controls. Histatin-1–functionalized GelMA scaffolds consistently enhanced osteochondral repair quality relative to nonfunctionalized GelMA, and PRP-enriched hydrogels promoted more complete osteochondral fill and favorable macrophage polarization in a rabbit model.

In contrast, studies using BMP-2 reported robust osteogenesis but variable effects on articular cartilage, with concerns about ectopic ossification and irregular subchondral remodeling. However, the small number of BMP-2 studies and heterogeneous dosing regimens, defect models, and outcome measures did not allow us to quantify the frequency of such complications or to define an optimal dose window. Similarly, because different growth factors were almost never compared head-to-head within the same model using standardized metrics, it was not possible to establish the relative efficacy of TGF-β, BMP-2, NELL-1, PRP, or histatin-1 using pooled effect estimates.

Delivery strategies for bioactive molecules varied substantially and included simple adsorption or mixing with hydrogels (bolus release), encapsulation in microparticles or injectable hydrogels for sustained release, and gradient delivery within multilayered constructs. Although studies employing controlled or sustained-release systems often reported more stable cartilage and bone regeneration than those relying on bolus delivery, the number of studies per combination of factor, carrier, and defect model was too low to formally test whether delivery mode explained outcome variability. Consequently, we provide a structured narrative synthesis instead of a comparative quantitative ranking of individual growth factors or delivery systems [61,62,63,64].

4.6. Animal Models and Translational Considerations

The choice of animal model substantially influenced reported outcomes across studies. Small-animal models provided important mechanistic insights but exhibited limited translational relevance due to anatomical and biomechanical differences from the human TMJ [80,81,82,83,84,85,86]. Larger animal models, including goats, sheep, dogs, and mini-pigs, more closely approximated human TMJ anatomy and loading conditions, enabling assessment of scaffold fixation, durability, and functional performance [22,25,35,36,41]. However, ethical, logistical, and economic constraints continue to limit their widespread use [86,87,88,89]. The 39 included studies used a wide spectrum of animal models (rats, rabbits, goats, sheep, dogs, and mini-pigs), which differ substantially in TMJ anatomy, biomechanical loading, and intrinsic healing capacity. These interspecies differences are crucial for interpreting regenerative outcomes and for selecting appropriate preclinical models.

Rodents and rabbits have been valuable for early mechanistic and proof-of-concept studies because of their low cost and ease of handling. However, many small laboratory animals experience relatively low TMJ loads during mastication and display joint orientations and movement patterns that differ from humans, limiting their ability to replicate the complex fibrocartilaginous loading environment of the human disc [25,85,87]. In addition, the small disc size in rodents and rabbits constrains surgical access, fixation strategies, and the use of anatomically realistic implants.

In contrast, large-animal models such as sheep, goats, mini-pigs, and dogs more closely approximate human TMJ anatomy, disc dimensions, and loading conditions [25,90,91]. Detailed morphologic, histological, and biomechanical characterization of the ovine TMJ disc has demonstrated notable similarities to the human disc, including an elliptical, biconcave fibrocartilaginous structure, a thinner central zone supported by a thicker peripheral “ring-like” region, abundant collagen and elastic fibres, and tensile and compressive moduli in the same order of magnitude as reported for human discs [25,25,85,90]. The relative position of the disc between the mandibular condyle and glenoid fossa, the separation into upper and lower joint compartments, and the relationship to adjacent structures (external acoustic meatus, foramen ovale) are also comparable [25,25,90,92]. At the same time, important differences must be acknowledged: in sheep, mediolateral mandibular movements predominate, the condylar surface is mediolaterally concave, and the temporal fossa is comparatively flat, more closely resembling the edentulous human TMJ [25]. These features highlight that no single animal model fully reproduces the human joint, and species-specific biomechanics need to be considered when extrapolating preclinical findings.

Our dataset reflects this range of models: 6 small-rodent, 19 rabbit, and 14 large-animal studies (goat, sheep, mini-pig, dog). When outcomes were examined by species, large-animal studies were more likely to report clinically relevant parameters such as implant fixation, long-term degenerative changes, and functional measures of mastication and jaw motion, whereas small-animal studies predominantly reported short- to medium-term histology and imaging. In a randomized ovine trial of three interposal disc implants, poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) and PCL + poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PCL + PEGDA) devices led to pronounced condylar osteolysis, loss of non-hyaline cartilage, foreign-body reactions and osteoarthritic changes, whereas a poly(glycerol sebacate)/PCL (PGS + PCL) elastomeric scaffold was completely resorbed within 6 months and largely preserved articular cartilage and subchondral bone architecture [26]. These results illustrate that materials appearing promising on the basis of mechanical testing or small-animal data may fail under the higher and more complex loading conditions present in large-animal TMJs.

Taken together, the available evidence supports a tiered approach to model selection. Small rodents and rabbits are appropriate for early-stage studies aimed at screening scaffold compositions, cell and drug-delivery strategies, and basic mechanisms of TMJ regeneration. However, evaluation of fixation methods, long-term durability, scaffold degradation, subchondral remodelling and osteoarthritic sequelae should preferentially be performed in large-animal models (sheep, goats, mini-pigs) that more closely reproduce human TMJ anatomy and functional loading [25,25,26,87,90,93]. For disc replacement, medium-term rabbit studies (3–6 months) can be used to refine implant design and biological augmentation, but at least one long-term large-animal study (≥6–12 months) with quantitative imaging, histology and, where feasible, kinematic assessment of mastication and jaw opening appears necessary before considering clinical translation. For condylar osteochondral repair, similar follow-up durations in large animals are likely required to capture subchondral bone remodelling and potential implant-related degeneration.

Methodological limitations were common among the included studies and are clearly reflected in the domain-level SYRCLE assessment. Nearly half of the studies were judged to have a high risk of bias for sequence generation (19/39, 48,7%). Our analysis has shown that the lack of clearly described randomization and blinding represents one of the most significant sources of bias across the included preclinical studies, as demonstrated by the SYRCLE assessment (Figure 3, Table 3). Insufficient reporting and implementation of these methodological safeguards substantially limits internal validity and reduces the translational reliability of the reported regenerative outcomes. Therefore, future preclinical TMJ tissue engineering studies should prioritize standardized study designs with explicit reporting of randomization and blinding procedures. Inadequate reporting of randomization and blinding, lack of standardized defect models, and limited use of biomechanical testing likely contributed to variability in reported outcomes [16]. Furthermore, control strategies were heterogeneous across the included studies. As summarized in Supplementary Table S3, several studies used the contralateral TMJ of the same animal as the primary control, whereas others relied on independent control animals or defect-only/no-scaffold controls. In unilateral models, use of the contralateral joint as a control may underestimate or distort the effect of the intervention, because altered loading and compensatory mastication can induce secondary changes in the non-operated TMJ; such contralateral degeneration has been documented in experimental models of unilateral TMJ injury [94]. These observations indicate that contralateral TMJs do not necessarily represent “healthy” or unbiased controls over time, and future preclinical TMJ regeneration studies should therefore clearly report the type of control used and, where feasible, favor bilateral intervention models or separate control cohorts [95,96] (see Supplementary Table S3).

We quantified data availability prior to any pooling attempt. Heterogeneity derived from: (i) divergent animal species and scale (rodent vs. rabbit vs. large animals), (ii) multiple defect models (perforation/partial discectomy/total discectomy/osteochondral/condylectomy), (iii) wide follow up range (1 week–12 months), and (iv) non standardized outcome metrics (multiple histological scoring systems, different μCT measures, and disparate biomechanical tests). Among these sources of heterogeneity, interspecies differences in TMJ anatomy, loading patterns, and healing capacity between small and large animals are likely to be particularly important for explaining variability in regenerative outcomes. Key drivers of heterogeneity included animal species, defect model, scaffold class, follow-up duration, and non-standardized outcome metrics; details on growth factor concentrations, dosing schedules, and per-group sample sizes were frequently missing, preventing standardized comparative analyses. Despite encouraging histological and radiological findings reported across multiple studies, substantial heterogeneity prevented formal pooling of effect sizes. Our Supplementary Table S3 (data-availability matrix) documents that for most clinically relevant outcomes there were <3 studies reporting the same continuous metric within a homogeneous subgroup. This lack of comparable effect estimates prevented robust pooled effect calculation and reliable heterogeneity statistics (I2). Therefore, we report a transparent narrative synthesis supported by the Supplementary Table S3 to enable reproducibility and facilitate future meta-analysis when standardized data become available.

4.7. Translational Perspective and Clinical Relevance

Despite encouraging preclinical outcomes, translation of scaffold-based tissue engineering strategies for temporomandibular joint regeneration into clinical trials remains limited. Key challenges include ensuring material safety, sterilizability, and reproducibility, as well as compliance with regulatory requirements and scalable manufacturing processes [94,97,98,99]. In practical terms, acellular TMJ scaffolds intended as implants are likely to follow device pathways (e.g., 510(k) or Investigational Device Exemption in the United States, or CE marking under the European Medical Device Regulation), whereas cell-loaded or gene-modified constructs would typically fall under advanced therapy medicinal product (ATMP) frameworks. These categories imply different expectations regarding preclinical evidence, manufacturing under good manufacturing practice (GMP) conditions, and the design of early-phase clinical trials. In addition, most preclinical studies lack long-term functional assessment and biomechanical validation under physiologically relevant loading conditions, which are essential prerequisites for clinical application [100].

Cell-based approaches, particularly those involving mesenchymal stem cells, have demonstrated short-term safety in intra-articular applications across various musculoskeletal indications, including osteoarthritis [101,102,103]. However, evidence for durable structural regeneration remains inconclusive. In the context of temporomandibular joint disorders, clinical data is scarce and largely limited to exploratory or small-scale studies. Notably, intra-articular injection of bone marrow-derived nucleated cells has been reported to improve clinical symptoms in patients with temporomandibular disorders, although radiological evidence of cartilage regeneration was not observed during follow-up [104]. Similar limitations have been described in later-stage clinical trials evaluating mesenchymal stem cell therapies for joint cartilage repair, where symptomatic improvement was not consistently accompanied by structural regeneration [105,106,107,108,109,110,111]. Taken together, these observations suggest that preclinical endpoints focused predominantly on histological or imaging markers of structural regeneration may not fully predict clinically meaningful improvements in pain, jaw function, or quality of life, and that functional outcome measures in animal models should be selected with these clinical endpoints in mind.

4.8. Implications for Future Research and Clinical Translation

In summary, scaffold-based tissue engineering strategies demonstrate clear regenerative potential for TMJ structures in preclinical settings, particularly when mechanically competent scaffolds are combined with mesenchymal stem cells and controlled bioactive signaling. However, current evidence remains insufficient to support direct clinical translation. Future progress will depend on standardized defect models, rigorous biomechanical validation, and long-term functional assessment in clinically relevant animal models. In the future perspectives, we emphasize that the evaluation of regeneration must not remain solely at the histological level. It is essential that future studies include standardized biomechanical tests that assess load-bearing capacity, functional performance, and long-term stability of the regenerated tissue. Only through a combination of histological, biomechanical, and functional outcomes can truly translational results in TMJ regeneration be achieved. Without such methodological refinement, promising experimental outcomes are unlikely to translate into predictable therapeutic solutions for patients with temporomandibular disorders. Based on the available data, we suggest that clinically oriented preclinical programs may include medium-term rabbit studies (3–6 months) and, where feasible, at least one long-term large-animal model (6–12 months) for disc replacement or condylar osteochondral repair, together with a basic set of functional outcomes (e.g., maximal interincisal opening and quantitative measures of mastication or bite force) and biomechanical testing of regenerated tissues under relevant loading. In parallel, clearer reporting of key manufacturing parameters and brief consideration of the intended regulatory route (device versus ATMP) could help better align experimental designs with subsequent clinical development. To address these gaps, we propose that future preclinical TMJ regeneration studies include a basic standardized panel of functional and biomechanical endpoints. At the joint level, this should at least comprise maximal interincisal opening and lateral/protrusive mandibular excursions (in mm), together with objective mastication-related measures such as bite force or mastication efficiency. At the tissue level, regenerated discs and osteochondral constructs should undergo ex vivo mechanical testing, including tensile and/or compressive modulus, stiffness and failure load, and, where feasible, cyclic loading under physiologically relevant conditions. These outcomes should be reported with clear test protocols and mean ± SD with group sizes, to enable both within-study interpretation and cross-study comparison. Harmonized functional and biomechanical outcome protocols would allow assessment of whether histologically promising scaffold-based strategies truly restore TMJ function under masticatory loading.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review provides a comprehensive synthesis of preclinical in vivo evidence on scaffold-based tissue engineering strategies for regeneration of temporomandibular joint structures. The available data demonstrates that both disc and osteochondral regeneration can be achieved under experimental conditions, particularly when mechanically competent scaffolds are combined with mesenchymal stem cells and carefully controlled bioactive signaling.

Scaffold-based approaches show preclinical promise, but translation is limited by heterogeneous study designs and incomplete quantitative reporting. Standardized reporting of sample sizes, primary outcome means ± SD, timepoints, and adverse events is required to enable robust comparative analyses. Importantly, functional restoration and long-term durability remain insufficiently addressed in most preclinical investigations, with fewer than half of the available studies reporting functional or biomechanical endpoints and very few using standardized, quantitatively comparable protocols. This lack of systematic functional evaluation constitutes a major barrier to translation, because histological and radiological improvements cannot, by themselves, guarantee clinically meaningful restoration of TMJ function.

Current evidence suggests that scaffold-based approaches alone are unlikely to ensure predictable TMJ regeneration. Instead, integrated strategies that balance mechanical stability with biological augmentation appear most promising. However, successful translation will depend on methodological refinement, including standardized defect models, rigorous biomechanical evaluation, and long-term functional assessment in clinically relevant animal models. Standardized reporting of cell type, dose, and delivery parameters, as well as growth factor identity, concentration, and release kinetics, will be essential to identify which combinations yield the most consistent and clinically relevant regenerative effects. In addition to standardized outcome reporting, model selection will be critical for successful translation. Small-animal experiments are appropriate for early proof-of-concept work, but positive findings in rodents or rabbits should be confirmed in at least one clinically relevant large-animal model that reproduces human TMJ anatomy and loading conditions before progression to human trials.

We emphasize that large animal models, such as sheep, goats, or minipigs, are essential due to their anatomical and biomechanical similarity to the human TMJ. They enable the assessment of long-term stability, fixation, and functional performance under human-like conditions, and therefore represent a crucial step toward clinical application.

In conclusion, scaffold-based tissue engineering represents a compelling regenerative concept for temporomandibular joint disorders, but its clinical implementation remains premature. Future well-designed preclinical studies are essential to establish reproducible, functionally relevant outcomes and to provide a robust foundation for eventual translation into clinical trials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/bioengineering13020169/s1, Supplementary Table S1. Extracted quantitative outcome data (means, SDs, group sizes, timepoints. Supplementary Table S2. Study-level SYRCLE risk-of-bias judgments (low/unclear/high) across all eight domains for each of the 39 included studies. Supplementary Table S3. Full extracted dataset of included studies: study identifiers, model parameters, intervention details, outcomes and numeric data (mean ± SD, n) with notes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., G.R., D.S. and P.M.; methodology, M.S., G.R. and P.M.; software, M.S. and P.M.; validation, M.S. and P.M.; formal analysis, M.S., D.S., G.R., J.M., A.A., M.V. and P.M.; investigation, M.S., D.S., G.R., J.M., A.A., M.V., N.J., L.V., M.N. and P.M.; resources, M.S., G.R. and P.M.; data curation, M.S., D.S., G.R., J.M., A.A., M.V. and P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S., D.S., G.R., J.M., N.J. and P.M.; writing—review and editing, M.S., D.S., G.R., J.M., A.A., M.V., N.J., L.V., M.N. and P.M.; visualization, M.S., D.S., G.R. and P.M.; supervision, M.S., G.R. and P.M.; project administration, M.S. and P.M.; funding acquisition, D.S. and G.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the JP (03/23) Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Serbia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alomar, X.; Medrano, J.; Cabratosa, J.; Clavero, J.A.; Lorente, M.; Serra, I.; Monill, J.M.; Salvador, A. Anatomy of the temporomandibular joint. Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI 2007, 28, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryaei, A.; Vapniarsky, N.; Hu, J.C.; Athanasiou, K.A. Recent Tissue Engineering Advances for the Treatment of Temporomandibular Joint Disorders. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2016, 14, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindelar, B.J.; Herring, S.W. Soft tissue mechanics of the temporomandibular joint. Cells Tissues Organs 2005, 180, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, E.; Detamore, M.S.; Mercuri, L.G. Degenerative disorders of the temporomandibular joint: Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J. Dent. Res. 2008, 87, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbaum, S.; Kelso, A.; Dairi, N.F.; Boucher, N.S.; Yu, W. Assessment of Condylar Changes in Patients with Degenerative Joint Disease of the TMJ After Stabilizing Splint Therapy: A Retrospective CBCT Study. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohrbach, R.; Dworkin, S.F. The Evolution of TMD Diagnosis: Past, Present, Future. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Yang, Y.; Dutra, E.H.; Robinson, J.L.; Wadhwa, S. Temporomandibular Joint Disorders in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 1213–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Wang, T.; He, Y.; Guo, Y. Applications of hydrogels in tissue-engineered repairing of temporomandibular joint diseases. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 2579–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredini, D.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Winocur, E.; Piccotti, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Lobbezoo, F. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2011, 112, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolwick, M.F.F.; Dimitroulis, G. Is there a role for temporomandibular joint surgery? Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1994, 32, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, L.; Westesson, P.L. Discectomy as an effective treatment for painful temporomandibular joint internal derangement: A 5-year clinical and radiographic follow-up. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2001, 59, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Chowdhury, S.; Navaneetham, A.; Upadhyay, S.; Alam, S. Costochondral Graft as Interpositional material for TMJ Ankylosis in Children: A Clinical Study. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2015, 14, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolford, L.M.; Dingwerth, D.J.; Talwar, R.M.; Pitta, M.C. Comparison of 2 temporomandibular joint total joint prosthesis systems. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, J.; Almarza, A.J. A review of in-vitro fibrocartilage tissue engineered therapies with a focus on the temporomandibular joint. Arch. Oral Biol. 2017, 83, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, N.; Cheng, J.; Sun, M.; Yang, P.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, J.; Duan, X.; Fu, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Biomechanically, structurally and functionally meticulously tailored polycaprolactone/silk fibroin scaffold for meniscus regeneration. Theranostics 2020, 10, 5090–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helgeland, E.; Shanbhag, S.; Pedersen, T.O.; Mustafa, K.; Rosén, A. Scaffold-Based Temporomandibular Joint Tissue Regeneration in Experimental Animal Models: A Systematic Review. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2018, 24, 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, F.; Chai, F.; Chijcheapaza-Flores, H.; Garcia-Fernandez, M.J.; Blanchemain, N.; Nicot, R. Systematic review of studies on drug-delivery systems for management of temporomandibular-joint osteoarthritis. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 123, e336–e341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgar, N.; Ghiaseddin, A.; Irani, S.; Rabbani, S.; Tafti, S.H.A.; Soufizomorrod, M.; Soleimani, M. Cartilage tissue engineering using injectable functionalized demineralized bone matrix scaffold with glucosamine in PVA carrier, cultured in microbioreactor prior to study in rabbit model. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 120, 111677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cengiz, I.F.; Maia, F.R.; da Silva Morais, A.; Silva-Correia, J.; Pereira, H.; Canadas, R.F.; Espregueira-Mendes, J.; Kwon, I.K.; Reis, R.L.; Oliveira, J.M. Entrapped in cage (EiC) scaffolds of 3D-printed polycaprolactone and porous silk fibroin for meniscus tissue engineering. Biofabrication 2020, 12, 025028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezelbash, F.; Eskandari, A.H.; Shirazi-Adl, A.; Kazempour, M.; Tavakoli, J.; Baghani, M.; Costi, J.J. Modeling of human intervertebral disc annulus fibrosus with complex multi-fiber networks. Acta Biomater. 2021, 123, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desnica, J.; Vujovic, S.; Stanisic, D.; Ognjanovic, I.; Jovicic, B.; Stevanovic, M.; Rosic, G. Preclinical Evaluation of Bioactive Scaffolds for the Treatment of Mandibular Critical-Sized Bone Defects: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socorro, M.; Dong, X.; Trbojevic, S.; Chung, W.; Brown, B.N.; Almarza, A. The goat as a model for temporomandibular joint disc replacement: Techniques for scaffold fixation. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, L. Three-dimensional, biomimetic electrospun scaffolds reinforced with carbon nanotubes for temporomandibular joint disc regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2022, 147, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Yi, P.; Wang, X.; Huang, F.; Luan, X.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, C. Acellular matrix hydrogel for repair of the temporomandibular joint disc. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2020, 108, 2995–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelo, D.F.; Morouco, P.; Alves, N.; Viana, T.; Santos, F.; Gonzalez, R.; Monje, F.; Macias, D.; Carrapico, B.; Sousa, R.; et al. Choosing sheep (Ovis aries) as animal model for temporomandibular joint research: Morphological, histological and biomechanical characterization of the joint disc. Morphologie 2016, 100, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ângelo, D.F.; Wang, Y.; Morouço, P.; Monje, F.; Mónico, L.; González-Garcia, R.; Moura, C.; Alves, N.; Sanz, D.; Gao, J.; et al. A randomized controlled preclinical trial on 3 interposal temporomandibular joint disc implants: TEMPOJIMS—Phase 2. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2021, 15, 852–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Cao, P.; Wang, P.; Hou, Y.; Tan, P.; Sun, J.; Li, Z.; Zhu, S. Decellularized-disc based allograft and xenograft prosthesis for the long-term precise reconstruction of temporomandibular joint disc. Acta Biomater. 2023, 159, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.L.; Brown, B.N.; Almarza, A.J. Decellularized small intestine submucosa device for temporomandibular joint meniscus repair: Acute timepoint safety study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, C.; Trindade, D.; Vieira, M.; Francisco, L.; Ângelo, D.F.; Alves, N. Multi-Material Implants for Temporomandibular Joint Disc Repair: Tailored Additive Manufacturing Production. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarafder, S.; Koch, A.; Jun, Y.; Chou, C.; Awadallah, M.R.; Lee, C.H. Micro-precise spatiotemporal delivery system embedded in 3D printing for complex tissue regeneration. Biofabrication 2016, 25, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Sui, B.; Liu, X.; Sun, J. A bioinspired and high-strengthed hydrogel for regeneration of perforated temporomandibular joint disc: Construction and pleiotropic immunomodulatory effects. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 20, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.H.; Chan, W.P.; Chiu, L.H.; Tsai, Y.H.; Fang, C.L.; Yang, C.B.; Chen, K.C.; Tsai, H.L.; Lai, W.F. Histological and Immunohistochemical Analyses of Repair of the Disc in the Rabbit Temporomandibular Joint Using a Collagen Template. Materials 2017, 9, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.P.; Lin, M.F.; Fang, C.L.; Lai, W.F. MRI and histology of collagen template disc implantation and regeneration in rabbit temporomandibular joint: Preliminary report. Transplant. Proc. 2004, 36, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.F.; Tsai, Y.H.; Su, S.J.; Su, C.Y.; Stockstill, J.W.; Burch, J.G. Histological analysis of regeneration of temporomandibular joint discs in rabbits by using a reconstituted collagen template. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2005, 34, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, E.; Nakahara, T.; Inoue, M.; Shigeno, K.; Tanaka, A.; Nakamura, T. Experimental Study on In Situ Tissue Engineering of the Temporomandibular Joint Disc using Autologous Bone Marrow and Collagen Sponge Scaffold. J. Hard Tissue Biol. 2015, 24, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.N.; Chung, W.L.; Pavlick, M.; Reppas, S.; Ochs, M.W.; Russell, A.J.; Badylak, S.F. Extracellular matrix as an inductive template for temporomandibular joint meniscus reconstruction: A pilot study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, e488–e505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B.N.; Chung, W.L.; Almarza, A.J.; Pavlick, M.D.; Reppas, S.N.; Ochs, M.W.; Russell, A.J.; Badylak, S.F. Inductive, scaffold-based, regenerative medicine approach to reconstruction of the temporomandibular joint disk. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, 2656–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahtiainen, K.; Mauno, J.; Ellä, V.; Hagström, J.; Lindqvist, C.; Miettinen, S.; Ylikomi, T.; Kellomäki, M.; Seppänen, R. Autologous adipose stem cells and polylactide discs in the replacement of the rabbit temporomandibular joint disc. J. R. Soc. Interface 2013, 29, 20130287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, J.L.; Takusagawa, T.; Sampaio, G.C.; He, H.; de Oliveira e Silva, E.D.; Vasconcelos, B.C.E.; McCain, J.P.; Redmond, R.W.; Randolph, M.A.; Guastaldi, F.P.S. Gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel with and without dental pulp stem cells for TMJ regeneration: An in vivo study in rabbits. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Chen, M.; Jiang, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, G.; Feng, J. Hst1/Gel-MA Scaffold Significantly Promotes the Quality of Osteochondral Regeneration in the Temporomandibular Joint. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Yao, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, P.; Feng, J.; Wu, G. Human salivary histatin-1-functionalized gelatin methacrylate hydrogels promote the regeneration of cartilage and subchondral bone in temporomandibular joints. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedrelow, D.S.; Rassi, A.; Ajeeb, B.; Jones, C.P.; Huebner, P.; Ritto, F.G.; Williams, W.R.; Fung, K.M.; Gildon, B.W.; Townsend, J.M.; et al. Regenerative Engineering of a Biphasic Patient-Fitted Temporomandibular Joint Condylar Prosthesis. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2023, 29, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, J.; Wei, S.; Ge, Q.; Wu, J.; Xue, L.; Qi, Y.; Xu, S.; Jin, H.; Gao, C.; et al. Delivery of dental pulp stem cells by an injectable ROS-responsive hydrogel promotes temporomandibular joint cartilage repair via enhancing anti-apoptosis and regulating microenvironment. J. Tissue Eng. 2024, 15, 20417314241260436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, P.; Ma, J.; Wang, P.; Han, X.; Fan, Y.; Bai, D.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X. Cell-mediated injectable blend hydrogel-BCP ceramic scaffold for in situ condylar osteochondralrepai. Acta Biomater. 2021, 123, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Hu, Y.; Zou, L.; Yan, S.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, K.; Liu, W.; He, D.; Yin, J. A bilayered scaffold with segregated hydrophilicity-hydrophobicity enables reconstruction of goat hierarchical temporomandibular joint condyle cartilage. Acta Biomater. 2021, 121, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Cao, Z.; Peng, Y.; Wu, R.; Xu, H.; Yuan, Z.; Xiong, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, W.; et al. Subchondral bone-inspired hydrogel scaffold for cartilage regeneration. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 218, 112721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, C.; Zheng, H.; Meng, Z.; Heng, B.C.; Zhou, T.; Jiang, S.; Wei, Y. Superwettable and injectable GelMA-MSC microspheres promote cartilage repair in temporomandibular joints. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 1026911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X. Co-culture of bone marrow stromal cells and chondrocytes in vivo for the repair of the goat condylar cartilage defects. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 2969–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chang, F.; Xu, W.; Ding, J. Repair of full-thickness articular cartilage defect using stem cell-encapsulated thermogel. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2018, 88, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; Hu, S.; Wu, N.; Jiang, S.; Shi, J. Therapeutic application of 3B-PEG injectable hydrogel/Nell-1 composite system to temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 17, 015004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, G.; Li, S.; Yu, K.; He, B.; Hong, J.; Xu, T.; Meng, J.; Ye, C.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Z.; et al. A 3D-printed PRP-GelMA hydrogel promotes osteochondral regeneration through M2 macrophage polarization in a rabbit model. Acta Biomater. 2021, 128, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yang, X.; Cheng, J.; Wang, X.; Shen, S.G. Distraction osteogenesis combined with tissue-engineered cartilage in the reconstruction of condylar osteochondral defect. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Zhang, B.; Man, C.; Ma, Y.; Hu, J. NEL-like molecule-1-modified bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells/poly lactic-co-glycolic acid composite improves repair of large osteochondral defects in mandibular condyle. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2011, 19, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormer, N.H.; Busaidy, K.; Berkland, C.J.; Detamore, M.S. Osteochondral interface regeneration of rabbit mandibular condyle with bioactive signal gradients. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, e50–e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takafuji, H.; Suzuki, T.; Okubo, Y.; Fujimura, K.; Bessho, K. Regeneration of articular cartilage defects in the temporomandibular joint of rabbits by fibroblast growth factor-2: A pilot study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 36, 934–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Bessho, K.; Fujimura, K.; Okubo, Y.; Segami, N.; Iizuka, T. Regeneration of defects in the articular cartilage in rabbit temporomandibular joints by bone morphogenetic protein-2. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2002, 40, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Bialy, T.; Uludag, H.; Jomha, N.; Badylak, S.F. In vivo ultrasound-assisted tissue-engineered mandibular condyle: A pilot study in rabbits. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2010, 16, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, K.; Takazakura, D.; Marukawa, K.; Shimada, M.; Nakagawa, K.; Takatsuka, S.; Yamamoto, E. The use of polylactic acid/polyglycolic acid copolymer and gelatin sponge complex containing human recombinant bone morphogenetic protein-2 following condylectomy in rabbits. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 31, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocca, L.; Donati, D.; Ragazzini, S.; Dozza, B.; Rossi, F.; Fantini, M.; Spadari, A.; Romagnoli, N.; Landi, E.; Tampieri, A.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and platelet gel improve bone deposition within CAD-CAM custom-made ceramic HA scaffolds for condyle substitution. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountziaris, P.M.; Tzouanas, S.N.; Sing, D.C.; Kramer, P.R.; Kasper, F.K.; Mikos, A.G. Intra-articular controlled release of anti-inflammatory siRNA with biodegradable polymer microparticles ameliorates temporomandibular joint inflammation. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 3552–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, V.A.; Ribeiro, L.N.M.; Alcântara, A.C.S.; Castro, S.R.; Rodrigues da Silva, G.H.; Gonçalves da Silva, C.; Breitkreitz, M.C.; Clemente-Napimoga, J.; Macedo, C.G.; Abdalla, H.B.; et al. Improved efficacy of naproxen-loaded NLC for temporomandibular joint administration. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Han, Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Hilborn, J.; Shi, L. Click chemistry-based biopolymeric hydrogels for regenerative medicine. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 16, 022003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xv, D.; Xie, C.; Lu, X. Smart self-healing hydrogel wound dressings for diabetic wound treatment. Nanomedicine 2025, 20, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, Z.; Pei, X. Recent advances of hydrogels as smart dressings for diabetic wounds. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2024, 12, 1126–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crapo, P.M.; Gilbert, T.W.; Badylak, S.F. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 3233–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehghani, S.; Aghaee, Z.; Soleymani, S.; Tafazoli, M.; Ghabool, Y.; Tavassoli, A. An overview of the production of tissue extracellular matrix and decellularization process. Cell Tissue Bank 2024, 25, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, T.J.; Swinehart, I.T.; Badylak, S.F. Methods of tissue decellularization used for preparation of biologic scaffolds and in vivo relevance. Methods 2015, 84, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, K.G.; Genasan, K.; Kamarul, T. Polyvinyl Alcohol-Chitosan Scaffold for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine Application: A Review. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, S.; Frommer, K.W.; Krumbholz, G.; Tsiklauri, L.; Gerstberger, R.; Rehart, S.; Steinmeyer, J.; Rickert, M.; Wenisch, S.; Schett, G.; et al. Expression of adipokines in osteoarthritis osteophytes and their effect on osteoblasts. Matrix Biol. 2017, 62, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naba, A.; Clauser, K.R.; Ding, H.; Whittaker, C.A.; Carr, S.A.; Hynes, R.O. The extracellular matrix: Tools and insights for the “omics” era. Matrix Biol. 2016, 49, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, R.S.; Chen, A.F.; Klatt, B.A. Cartilage regeneration. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2013, 21, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Du, C.; Liu, S.; Zhao, P.; Gao, S.; Chen, B.; Wu, X.; Huang, W.; Zhu, Z.; Liao, J. Notch1 signaling regulates Sox9 and VEGFA expression and governs BMP2-induced endochondral ossification of mesenchymal stem cells. Genes Dis. 2024, 12, 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalairaj, M.S.; Pradhan, R.; Saleem, W.; Smith, M.M.; Gaharwar, A.K. Intra-Articular Injectable Biomaterials for Cartilage Repair and Regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 2303794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thysen, S.; Luyten, F.P.; Lories, R.J. Targets, models and challenges in osteoarthritis research. Dis. Model. Mech. 2015, 8, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H. Injectable hydrogels delivering therapeutic agents for disease treatment and tissue engineering. Biomater. Res. 2018, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Jing, Y.; Su, J. Subchondral bone microenvironment in osteoarthritis and pain. Bone Res. 2021, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Chen, Y.; Dou, C.; Dong, S. Microenvironment in subchondral bone: Predominant regulator for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, D.B.; Gallant, M.A. Bone remodelling in osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2012, 8, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrivikraman, G.; Athirasala, A.; Twohig, C.; Boda, S.K.; Bertassoni, L.E. Biomaterials for Craniofacial Bone Regeneration. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 61, 835–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Meng, Z.; Chen, G.; Xie, D.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Tang, W.; Liu, L.; Jing, W.; Long, J.; et al. Restoration of critical-size defects in the rabbit mandible using porous nanohydroxyapatite-polyamide scaffolds. Tissue Eng. Part A 2012, 18, 1239–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scadden, D.T. The stem-cell niche as an entity of action. Nature 2006, 441, 1075–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerssens, J.; Boonen, S.; Lowet, G.; Dequeker, J. Interspecies differences in bone composition, density, and quality: Potential implications for in vivo bone research. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilsanz, V.; Roe, T.F.; Gibbens, D.T.; Schulz, E.E.; Carlson, M.E.; Gonzalez, O.; Boechat, M.I. Effect of sex steroids on peak bone density of growing rabbits. Am. J. Physiol. 1988, 255, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, S.; Largo, R.; Calvo, E.; Rodríguez-Salvanés, F.; Marcos, M.E.; Díaz-Curiel, M.; Herrero-Beaumont, G. Bone mineral measurements of subchondral and trabecular bone in healthy and osteoporotic rabbits. Skelet. Radiol. 2006, 35, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpakci, K.N.; Willard, V.P.; Wong, M.E.; Athanasiou, K.A. An interspecies comparison of the temporomandibular joint disc. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, D.K.; Daniel, J.C.; Herzog, S.; Scapino, R.P. An animal model for studying mechanisms in human temporomandibular joint disc derangement. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1994, 52, 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almarza, A.; Brown, B.; Arzi, B.; Angelo, D.F.; Chung, W.L.; Badylak, S.F.; Detamore, M.S. Preclinical Animal Models for Temporomandibular Joint Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2018, 24, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, R.A.; Pfeiffer, F.M.; Choma, T.J. The minipig as a potential model for pedicle screw fixation: Morphometry and mechanics. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strom, D.; Holm, S.; Clemensson, E.; Haraldson, T.; Carlsson, G.E. Gross anatomy of the mandibular joint and masticatory muscles in the domestic pig (Sus scrofa). Arch. Oral Biol. 1986, 31, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapniarsky, N.; Aryaei, A.; Arzi, B.; Hatcher, D.C.; Hu, J.C.; Athanasiou, K.A. The Yucatan Minipig Temporomandibular Joint Disc Structure-Function Relationships Support Its Suitability for Human Comparative Studies. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2017, 23, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinno, Y.; Jimbo, R.; Lindström, M.; Sawase, T.; Lilin, T.; Becktor, J.P. Vertical Bone Augmentation Using Ring Technique with Three Different Materials in the Sheep Mandible Bone. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2018, 33, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basyuni, S.; Ferro, A.; Santhanam, V.; Birch, M.; McCaskie, A. Systematic scoping review of mandibular bone tissue engineering. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 58, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevanovic, M.; Selakovic, D.; Vasovic, M.; Ljujic, B.; Zivanovic, S.; Papic, M.; Zivanovic, M.; Milivojevic, N.; Mijovic, M.; Tabakovic, S.Z.; et al. Comparison of Hydroxyapatite/Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) and Hydroxyapatite/Polyethyleneimine Composite Scaffolds in Bone Regeneration of pigs Mandibular Critical Size Defects: In Vivo Study. Molecules 2022, 27, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.A.; Servais, J.M.; Polur, I.; Li, Y.; Xu, L. Articular cartilage degeneration in the contralateral non-surgical temporomandibular joint in mice with a unilateral partial discectomy. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2014, 43, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sillmann, Y.M.; Eber, P.; Orbeta, E.; Wilde, F.; Gross, A.J.; Guastaldi, F.P.S. Milestones in Mandibular Bone Tissue Engineering: A Systematic Review of Large Animal Models and Critical-Sized Defects. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acri, T.M.; Shin, K.; Seol, D.; Laird, N.Z.; Song, I.; Geary, S.M.; Chakka, J.L.; Martin, J.A.; Salem, A.K. Tissue Engineering for the Temporomandibular Joint. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, e1801236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Culbreath, C.J.; Taylor, M.S.; McCullen, S.D.; Mefford, O.T. A Review of Additive Manufacturing in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2024, 3, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, C.; Zhang, B.; Yao, C.; Zhang, Y. Advances in 3D-printed scaffold technologies for bone defect repair: Materials, biomechanics, and clinical prospects. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 2025, 24, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.B.; Irfan, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, W. Redefining Medical Applications with Safe and Sustainable 3D Printing. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 6470–6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Hu, J.; Zhu, S. Self-repair capability of surgically created incisions in TMJ disc: An experimental study on goats. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2014, 42, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosanquet, A.; Ishimaru, J.; Goss, A.N. Effect of experimental disc perforation in sheep temporomandibular joints. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1991, 20, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, E.; Bays, R.; Sharawy, M. Osteoarthrosis of the temporomandibular joint following experimental disc perforation in Macaca fascicularis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1988, 46, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, H.; Shigematsu, H.; Hamao, A.; Magshi, S.; Suzuki, S.; Sakashita, H. Effect of disc perforation on the temporomandibular joint: An experimental study and review of the literature on a canine model. Jpn. J. Oral Diagn./Oral Med. 2003, 16, 349–361. [Google Scholar]

- Basurto, I.M.; Passipieri, J.A.; Gardner, G.M.; Smith, K.K.; Amacher, A.R.; Hansrisuk, A.I.; Christ, G.J.; Caliari, S.R. Photoreactive Hydrogel Stiffness Influences Volumetric Muscle Loss Repair. Tissue Eng. Part A 2022, 28, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Yoo, Y.; Shin, H.; Kim, H.; Min, D.S.; Bae, J.S.; Seo, Y.K. Highly Efficient Soluble Blue Delayed Fluorescent and Hyperfluorescent Organic Light-Emitting Diodes by Host Engineering. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 7070–7080. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, J.C.; Shukla, M.; Shukla, M. From bench to bedside: Translating mesenchymal stem cell therapies through preclinical and clinical evidence. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1639439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Santalla, M.; Bueren, J.A.; Garin, M.I. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cell-based therapy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: An update on preclinical studies. EBioMedicine 2021, 69, 103427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]