Abstract

This study investigated methane (CH4) production in a bioelectrochemically enhanced anaerobic digester (BEAD) equipped with a pair of 3-dimensional flow-through electrodes made of conductive polypropylene biorings. The performance of the BEAD reactor was compared to that of a similarly sized Anaerobic Upflow Sludge Bed (UASB) reactor. The reactors were operated at a temperature of 22 ± 1 °C using food waste (FW) leachate fed at organic loading rates of 3–8 g (LR d)−1 or at a temperature of 35 ± 1 °C using the liquid fraction of FW separated using a screw press. With both tested feedstocks, the BEAD reactor demonstrated up to 30% higher CH4 yield, reaching 0.35–0.38 L g−1 (COD consumed), compared to the UASB reactor. Additionally, reactor stability under organic overload conditions improved, with the difference more pronounced at organic loads above 6 g (LR d)−1. Energy consumption for bioelectrochemical CH4 production was estimated at 5.1–12.4 Wh L−1 (of CH4 produced), which is significantly below the energy consumption for electrochemical H2-based methanation. Overall, BEAD increases methane production and improves process stability, offering a novel sustainable solution for waste management.

1. Introduction

Although anaerobic digestion (AD) is an excellent technology for converting waste organics into biogas, only a small fraction of biodegradable organics is actually used for biogas production [1]. According to the International Energy Agency’s 2020 report, biomethane production in 2018 amounted to approximately 35 million tons of oil equivalent (Mtoe), accounting for only 6% of the global biogas production potential of 570 Mtoe [2]. Common challenges hindering widespread AD adoption for methane production from organic wastes include the high transportation costs of organic wastes to AD facilities, the substantial costs of constructing anaerobic reactors, the relatively low volumetric rates of biogas production often limited by hydrolysis, and the susceptibility of the AD process to various external uncontrollable factors [3,4]. Municipal anaerobic digesters typically operate with hydraulic retention times exceeding 20 days [5,6,7], whereas high-rate anaerobic systems like Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Bed (UASB) reactors face limitations in processing feedstocks with high solid contents and require highly skilled operators for efficient operation [8]. Additionally, fluctuations in feedstock quantity and quality often result in organic overloads, leading to acidification events that can severely impact methanogenic populations [9,10]. Recovering from such disturbances can be extremely long, sometimes necessitating re-inoculation to fully restore reactor performance. Moreover, successful AD operation requires relatively high temperatures (35–38 °C), which pose challenges in colder regions where energy requirements for reactor heating may nearly equal energy production [11].

Recent advances in the development of the bioelectrochemically enhanced anaerobic digestion (BEAD) process offer a promising approach to resolve some of the limitations associated with conventional anaerobic reactors. A BEAD reactor is based on the microbial electrolysis cell (MEC) concept and integrates conventional pathways for organic matter hydrolysis, fermentation, and methane production with bioelectrochemical pathways involving electroactive microorganisms capable of direct or indirect electron exchange with electrodes [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Accordingly, it includes at least one pair of flow-through electrodes (anode and cathode). In this configuration, anaerobic exoelectrogenic microorganisms, such as Geobacter spp., oxidize organic matter using the anode as a terminal electron acceptor. To overcome thermodynamic limitations, electron flow to the cathode is assisted by a power supply operated below the onset of water electrolysis [13,15,16,17,21,22,23,24,25]. At the cathode, H2 produced electrochemically or with the assistance of electroactive microorganisms is utilized for CH4 production. Recent studies have identified several pathways leading to CH4 production, including direct and indirect electron transfer mechanisms, as well as direct electromethanogenesis from CO2 [17,18,21,26,27]. This combination of pathways leads to increased CH4 yield in bioelectrochemical systems, which can be attributed to the higher affinity of anodophilic electroactive microorganisms for acetate and other acidified substrates [16,28,29,30] and enhanced electron exchange between the members of syntrophic microbial consortium [31]. In addition to increased biogas production, improved reactor stability under varying operational conditions and stable performance at lower mesophilic temperatures have been reported [15,20].

The slow hydrolysis of complex organic substrates, such as food waste, is the main factor limiting the rate of CH4 production and COD removal in anaerobic reactors [32,33,34,35]. To resolve this limitation, a two-phase process typically includes a pre-treatment step in a bioreactor operated under conditions optimized for organic substrate hydrolysis and fermentation [36]. This pre-treatment step can be accomplished in a dry fermenter such as a Leach Bed Reactor (LBR) [37]. LBRs are attractive as a low cost and low energy consumption approach for pretreatment. Nevertheless, this pretreatment system faces limitations such as clogging of the waste-holding chamber and prolonged fermentation times of up to 14–18 days. A recently developed solid-state submerged fermenter (3SF) offers solutions for overcoming these limitations [38]. This new reactor design allows for a higher volumetric loading rate as well as shorter fermentation times of 8–10 days. Furthermore, new pre-treatment methods such as solid–liquid separation with a screw press [39], hydrothermal pretreatment [33,40,41,42] and coupled alkali-microwave-H2O2 oxidation pretreatment [43] have emerged.

This proof-of-concept study aimed to evaluate the performance of a UASB-style BEAD reactor with an upflow configuration of three-dimensional flow-through electrodes. To enable a direct performance comparison, a conventional UASB (Control) reactor was operated simultaneously with the BEAD reactor. Since the effective operation of high-rate anaerobic reactors based on the UASB design requires feedstock with low solid contents, food waste was pretreated in all experiments. The broad applicability of the proposed approach to various types of organic waste and solids pretreatment methods was demonstrated using two distinct feedstocks: leachate from a 3SF LBR reactor fed with synthetic food waste and the liquid fraction of food waste collected from a local food bank and separated using a screw press, i.e., a two-phase anaerobic digestion process was adopted for the experiments. To ensure the robustness and broad applicability of the proposed approach, experiments were conducted by two independent research groups at different geographical locations using different feedstocks and two different mesophilic temperatures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inoculum and Feedstock Characteristics

All reactors used for CH4 production from FW leachate were inoculated with homogenized granular anaerobic sludge treating agriculture waste (Lassonde Inc., Rougemont, QC, Canada) with an average VSS content of 40–45 g L−1. Reactors used for treating screw press separated (SPS) liquid were inoculated with the same inoculum; however, the anaerobic sludge was not homogenized.

Food waste leachate was obtained in a 3SF LBR operated on simulated FW. This simulated FW was composed of carrots (40%), potatoes (35%), bread (15%), and pet food (10%). Leachate was collected at the end of each LBR batch (approximately 8–10 days in duration). The total suspended solids (TSS) and volatile suspended solids (VSS) of the FW leachate were 4.9% ± 0.05% and 2.7% ± 0.03%. For initial tests, the leachate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min (THERMO SCIENTIFIC, Waltham, MA, USA, Sorvall, Legend RT+ Centrifuge, rotor diameter 19 cm) to remove all remaining solids, while non-centrifuged leachate was used for subsequent tests.

For experiments involving screw press separated (SPS) liquid, food waste was procured from a food bank (Moisson Montreal) located in Montreal, QC, Canada. Solid–liquid separation was achieved with a CP-4 screw press (Vincent Corporation, Tampa, FL, USA). The screw press was operated at 20 rpm with an applied pressure of 60 psig. The liquid fraction was collected and stored at 4 °C until further use. Detailed description of the screw press operation conditions can be found elsewhere [39].

2.2. Reactor Design and Location

Experiments were conducted at two different laboratories located at Carleton university (Ottawa, ON, Canada) and at the National Research Council of Canada (NRC, Montreal, QC, Canada).

At each location, all experiments were conducted using two simultaneously operated cylindrical glass reactors (BEAD and Control). Since the experiments were conducted independently at two different laboratories, slightly different reactor dimensions were employed. At Carleton university (Ottawa), each reactor had a height of 435 mm and a diameter of 54 mm, resulting in a total volume of 1 L and a working (liquid) volume of 0.65 L. At the NRC (Montreal), the reactors had the same design and internal diameter, however each reactor had a working liquid volume of 0.45 L.

In all experimental setups, reactors were equipped with external recirculation loops. An upflow velocity of 1–2 m h−1 was maintained using peristaltic pumps. Also, the reactors were equipped with temperature and pH probes. Heating elements wrapped around the external recirculation lines were used to maintain a preset temperature. Reactor pH was maintained at a preset level using a pH controller connected to a peristaltic pump, which added either 0.25 N HCl solution or 0.25 N NaOH solution into the external recirculation loop.

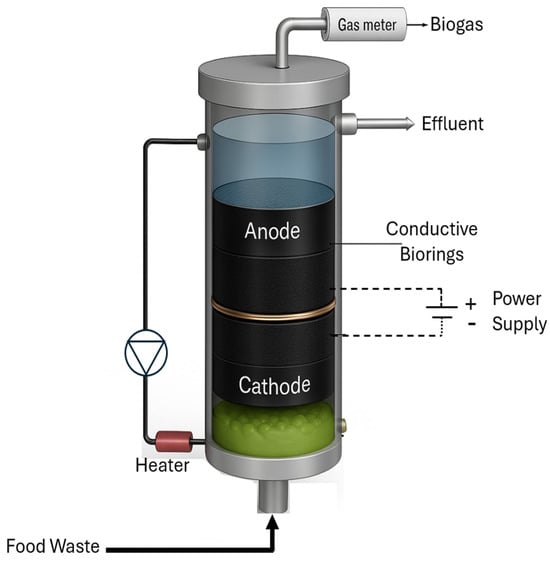

The BEAD reactor used a membrane-less, flow-through electrode configuration. Titanium current collectors (meshes) measuring 120 mm in height, 20 mm in width, and 2 mm in thickness, were used in both the anode and cathode compartments. The flow-through electrodes were composed of densely packed custom-made electrically conductive biorings (c-biorings) with each electrode compartment containing 30 c-biorings (Montreal) or 42 c-biorings (Ottawa). The c-biorings had a hollow cylinder shape with an approximate surface area of 11.4 cm2, an internal diameter of 15 mm, a wall thickness of 2 mm, a height of 12 mm and a weight of 1.7 g. These c-biorings were made of Polypropylene containing 12% carbon black (CB) and 2% carbon nanotubes (CNT), resulting in a conductivity of 200–250 Ohm (top to bottom).

The electrode compartments were separated by a non-conductive 3 mm thick geotextile separator perforated with multiple 2–3 mm holes. The cathode compartment was positioned at the reactor bottom to enhance H2 solubilization. This configuration takes advantage of the longer time for H2 bubbles produced at the cathode to reach liquid surface. Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of the BEAD reactor. The Control reactor had an identical design; however, it was filled with non-conductive Polypropylene biorings (Ottawa) and lacked power supply. The Control reactor in Montreal followed a standard UASB design and lacked microbial support.

Figure 1.

BEAD reactor diagram.

2.3. Reactor Startup and Operating Conditions

For the startup of LBR leachate-fed reactors at Carleton university (Ottawa), both BEAD and Control reactors were inoculated with 550 mL of homogenized anaerobic sludge, followed by the addition of 100 mL of diluted centrifuged leachate with a COD concentration of 10 g L−1. During the first three weeks of the experiment, reactors operated in batch mode with 20 mL food waste (FW) leachate added daily to each reactor. Once biogas production and composition stabilized reaching more than 60% CH4 content, continuous mode of reactor operation started. A temperature of 22 ÷ 1 °C was maintained (room temperature).

The reactor startup procedure at the NRC laboratory (Montreal) was similar, but each reactor was inoculated with 150 mL of homogenized anaerobic sludge. At each location, various organic loading rates (OLRs) were applied to both reactors, as shown in Table 1. The corresponding hydraulic retention time (HRT) values varied between 3–12 days. A temperature of 22 ÷ 1 °C was maintained (room temperature).

Table 1.

Experimental conditions during BEAD and Control reactor experiments. OLR values represent the average of 5–8 measurements with standard deviations estimated to be below 7% of each value.

In all experiments, each OLR was maintained until observing steady-state performance in terms of CH4 production (both reactors) and BEAD reactor current. Steady state was considered when observing less than a 10% variation in current and CH4 production for at least 3 consecutive days. Key performance parameters (CH4 production, yield, etc.) were compared using Student’s t-test, provided a sufficient number of measurements was available. In total, the BEAD and Control reactors were operated with food waste leachate for 68 days and 47 days in at Carleton University (Ottawa) and at the NRC laboratory (Montreal), respectively.

During the experiments involving reactor operation with screw press-separated (SPS) liquid feedstock in Montreal, the reactors were reinoculated and once steady state performance was observed operated for 26 days at a temperature of 35 °C. Similar to the experiments with FW leachate, tests using SPS liquid were conducted at several organic loads outlined in Table 1. Due to the significant presence of settleable fine solids in the SPS liquid, a settler with a hydraulic retention time of 4–5 days was utilized to partially remove these solids and facilitate hydrolysis and fermentation of the SPS liquid. Table 2 provides SPS liquid characterization at the settler exit.

Table 2.

FW leachate and SPS liquid characterization. Values correspond to concentrations in the reactor influent stream, i.e., after feedstock dilution. Volatile fatty acid (VFA) and COD values represent the average of 5–8 measurements with standard deviations below 5% of each value.

At both locations, the feedstock was supplied to the reactors without removing trace oxygen (e.g., by flushing with N2), as multiple studies have demonstrated the positive impact of trace oxygen concentration on biogas production [44].

In all experiments involving FW leachate in Ottawa, Canada, reactors were operated at room temperature (22 ± 1 °C) and near-neutral pH (7.0 ± 0.2). FW leachate treatment tests were carried out in the BEAD reactor operated at a constant applied voltage of 1.4 V, which was maintained using a potentiostat (Metrohm, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Experiments utilizing screw press separated (SPS) liquid feedstock (Montreal, Canada) were also carried out at pH 7, but a temperature of 35 °C was maintained. Also, a lower applied voltage of 1.2 V was used throughout the SPS liquid fed BEAD reactor experiments.

2.4. Analytical Methods and Calculations

Chemical oxygen demand (COD) measurements were conducted using the Potassium Dichromate spectrophotometric method [45]. For the estimation of soluble COD (sCOD), samples were filtered using a 0.45 µm pore size filter membrane in a vacuum filter. The filtration step was omitted for total COD (tCOD) determination.

The influent and effluent concentrations of volatile fatty acids (VFAs) including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, were analyzed using HPLC (Thermo Scientific Ultimate 3000 series, Waltham, MA, USA). The mobile phase was composed of 100% Acetonitrile and 2.5 mM methanesulfonic acid and AcclaimTM OA 5 µm, 4 × 150 mm column was used. The column temperature was maintained at 30 °C, with a fixed mobile phase flow rate of 1 mL min−1 and the detector’s absorption wavelength set at 210 nm.

Biogas production was quantified using gas flow meters (Milligas counter, Ritter North America Inc., Summerville, SC, USA). The biogas composition was measured using gas chromatography. Method details are provided elsewhere [46].

The COD Removal Efficiency (RE, %) was calculated by comparing the influent and effluent COD values, while CH4 yield calculations were based on the amount of CH4 produced relative to the amount of COD removed (L g−1).

Cathodic Coulombic Efficiency (CEc) was calculated as:

where m is the number of moles of electrons required to produce one mole of CH4 (m = 8); F is the Faraday constant (F = 96,485 C mol−1); QCH4 is the flow of CH4, L d−1, i is the current (A); T is the total time in a day expressed in seconds (T = 86,400 s).

To estimate the contribution of bioelectroactive microorganisms to CH4 production in the BEAD reactor, CH4 production in the BEAD and Control reactors was compared under identical operating conditions as follows. The maximum theoretical CH4 production attributable to bioelectrochemical activity was estimated based on the electrical current measured in the BEAD reactor and the assumption of 100% CEc. Under this assumption, all electrons transferred through the cathode are used exclusively for the conversion of CO2 into CH4. Accordingly, Equation (1) can be rearranged:

Equation (2) provides the theoretical CH4 production, which could be produced if all measured current is used for CH4 formation. To compare the theoretical value with the actual increase in CH4 production, once CH4 production rates in the Control and BEAD reactors were determined under identical conditions, the difference between these two values, which represents actual CH4 production due to the applied voltage, was calculated.

Additionally, energy consumption for bioelectrochemical production of CH4 (Wh L−1) was calculated as:

where U is the voltage (V), I is the current (A) and VCH4 is the volume of methane produced in 24 h (L).

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the experimental results describing the evaluation of the proposed bioelectrochemical anaerobic digestion (BEAD) concept using centrifuged and non-centrifuged food waste leachate from the LBR reactor. To ensure the robustness and broad applicability of the proposed combined AD-MEC setup, the experiments were also conducted using screw press separated (SPS) food waste as a feedstock. Furthermore, the approach was tested at two distinctly different operating temperatures: 22 °C (food waste leachate feedstock tests) and 35 °C (SPS feedstock tests). By conducting the experiments simultaneously at two independent laboratories, further validation of the proposed approach was achieved.

3.1. Operation of BEAD and Control Reactors on Food Waste Leachate

As described in the Materials and Methods section, at both locations, reactor experiments were started by initially maintaining a low organic load within a range of 1.5–3 g (LR d)−1 during the initial 3–4 weeks of operation (adaptation phase). In experiments utilizing FW leachate, reactors were operated on the centrifuged leachate before changing the feed to non-centrifuged leachate. Following the successful startup of each reactor, experiments were conducted with progressively increasing organic loads, as outlined in Table 1.

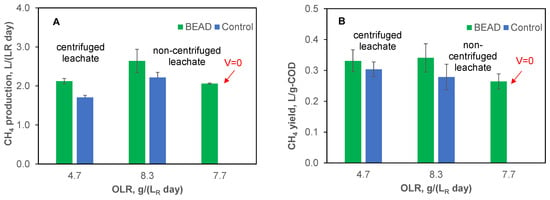

During tests conducted in Montreal, following the adaptation phase, both BEAD and Control reactors were operated using centrifuged leachate at an organic load of 4.7 g (LR d)−1 for a duration of 16 days (Test #1-1, Table 1). In the following experimental phase (Test #1-2), the feedstock was switched to the non-centrifuged leachate resulting in an OLR of 8.3 g (LR d)−1. The resulting performance of the two reactors is compared in Figure 2, illustrating the average steady state volumetric rates of CH4 production (Figure 2A) and CH4 yields (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Specific rate of CH4 production (A) and CH4 yields (B) observed during BEAD and Control reactor operation at NRC (Montreal, reactor temperature 22 °C). Error bars represent the standard deviation.

As can be seen from this comparison, at both tested organic loads, CH4 production was higher in the BEAD reactor, with the difference becoming more pronounced at an OLR of 8.3 g (LR d)−1. At this organic load, both CH4 production and yield were improved by 20–22%. At the same time, the biogas composition and COD removal efficiencies of the two reactors were comparable with values in a range of 79–80% and 92–95%, respectively. The observed high COD removal efficiency can be attributed to FW pretreatment in the LBR reactor, resulting in elevated concentrations of readily biodegradable short chain fatty acids, such as acetate.

Interestingly, reactor operation on the non-centrifuged leachate did not lead to a performance decline, suggesting that a significant part of leachate solids was also readily biodegradable. However, considering the relatively short duration of 18 days for this experiment, additional tests may be warranted to confirm stable long-term reactor performance and the absence of inert solid accumulation in the reactors.

To confirm the impact of microbial electrolysis on CH4 yield, in the following Test #1-3, conducted using non-centrifuged leachate, the BEAD reactor was operated at zero applied voltage (Figure 2). Due to variations in feedstock composition, the test was conducted at a slightly lower organic load of 7.7 g (LR d)−1. Under these conditions, both CH4 production and yield decreased approaching the performance of the Control reactor, while the COD removal efficiency remained high (94–95%). These results suggest that bioelectrochemical conditions predominantly influenced CH4 yield. Previous studies have demonstrated the higher efficiency of direct electromethanogenesis as compared to CH4 production through such intermediates as H2 [26,47,48,49].

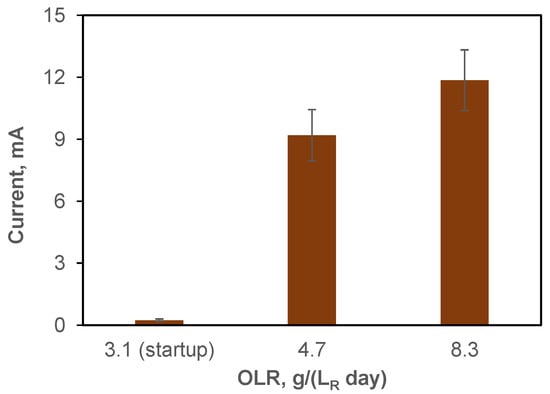

In addition to the observed differences in CH4 production, the proliferation of electroactive populations can also be inferred from the observed increase in current in the BEAD reactor over time (Figure 3). Notably, the current increased from 0.2 mA at reactor startup (day 1) to 12 ± 1.5 mA by the end of BEAD operation on non-centrifuged leachate (day 34). These values can be used to estimate the energy consumption for bioelectrochemical CH4 production by first calculating the difference between CH4 production in the BEAD and Control reactors and then dividing energy consumption by this value.

Figure 3.

BEAD reactor current observed at the NRC laboratory (Montreal, reactor temperature 22 °C) during the startup phase and reactor operation at OLR values of 4.7 and 8.3 g (LR d)−1. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

For BEAD reactor operation on centrifuged and non-centrifuged FW leachate, energy consumption estimates of 5.1 and 12.4 Wh , respectively, were calculated. Importantly, these values are significantly lower than the energy required for CH4 production using electrochemical H2. Assuming an energy consumption of 4.5–5.0 Wh for electrochemical H2, based on average reported values for commercial electrolyzers [50] and considering the stoichiometry of CO2 to CH4 conversion, wherein a CO2/H2 molar ratio of 4 is required for hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, an energy consumption of 18–20 Wh is obtained. Therefore, the substantially lower energy consumption in the BEAD reactor can be interpreted as evidence of electromethanogenesis as one of the pathways leading to CH4 production at the BEAD reactor cathode. At the same time, energy consumption with respect to all CH4 produced in BEAD through a combination of conventional AD and bioelectrochemical pathways was only 0.1 Wh Wh .

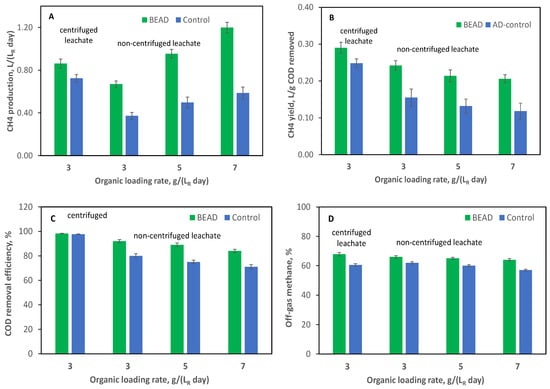

To confirm the observed improvement in food leachate conversion to CH4, the operation of BEAD and Control reactors was repeated at the Carleton University laboratory (Ottawa). Results of this experiment are summarized in Figure 4. Similar to the experiments conducted at the NRC laboratory (Montreal), both reactors (BEAD and Control) underwent startup at a low organic load using centrifuged leachate (Table 1, Test #2-1). Figure 4 shows results observed during reactor operation at an OLR = 3 g (LR d)−1. Which already showed improved CH4 production and yield in the BEAD reactor.

Figure 4.

(A) CH4 production, (B) CH4 yield; (C) COD removal efficiency, and (D) CH4 percentage in the reactor off-gas observed during BEAD and Control reactors operation at Carleton university (Ottawa, reactor temperature 22 °C). Error bars represent the standard deviation.

In the subsequent phase of the experiment, both reactors were fed with non-centrifuged leachate at progressively increasing OLRs (Tests #2-2 to #2-4). As can be seen from the results presented in Figure 4A, consistently higher biogas production was observed in the BEAD reactor as compared to the Control reactor at all tested organic loads with non-centrifuged leachate. Also, CH4 yields were significantly different between the two reactors at higher organic loads (Figure 4B). While CH4 yield declined in both reactors with the increase in organic load, this decline was substantially more pronounced in the Control reactor at the highest organic load, resulting in a 75% difference in CH4 yield between the reactors.

The two reactors demonstrated similar COD removal at an OLR of 3 g (LR d)−1 during reactor operation on centrifuged leachate. However, BEAD exhibited higher removal at OLR values of 5 and 7 g (LR d)−1 during reactor operation on non-centrifuged leachate (Figure 4C), with differences of up to 18%. Such difference was not observed in the previous set of experiments. It can be hypothesized that during a relatively brief previous experiment conducted at the NRC laboratory (Montreal), solids accumulated in the Control reactor, resulting in comparable COD removal efficiencies. Additionally, the CH4 percentage remained higher in the BEAD reactor off-gas throughout the experiment, with average values of 66% and 60% for the BEAD and Control reactors, respectively (Figure 4D).

At both locations, at the end of reactor experiments, c-biorings were removed from BEAD reactors and visually inspected. This inspection showed no observable signs of degradation after 68 days and 73 days of operation, at Ottawa and Montreal locations, respectively. Indeed, a comparison of different biofilm supports in anaerobic digestion demonstrated that polypropylene fiber and biorings media significantly increase CH4 production and COD removal [51,52]. Notably, an attempt to operate a UASB-style reactor using carbon felt at the Ottawa laboratory led to reactor clogging at high organic loading rates (unpublished results).

Overall, the results of experiments conducted at two different laboratories yielded qualitatively similar findings, suggesting that under bioelectrochemical conditions, conventional pathways for biomethane production were augmented by the activity of electroactive microorganisms, both at the anode and cathode. Moreover, the observed improvement in biogas yield agreed well with the recently published results of bioelectrochemically enhanced anaerobic digestion of industrial fishery wastewater, where a similar range of CH4 yield and current density was observed [28]. Additionally, methane production was observed to triple in a microbial electrolysis–anaerobic digestion (ME-AD) reactor treating waste activated sludge [22].

3.2. Biogas Production from SPS Liquid

To demonstrate the versatility of the BEAD reactor for treating various feedstocks, in addition to its operation on FW leachate, another set of experiments was conducted at the NRC laboratory (Montreal) using SPS liquid and a higher reactor temperature of 35 °C. Similar to previous tests, two rectors were simultaneously operated. However, to provide additional comparison, in this experiment, the Control reactor setup was changed to a more conventional UASB configuration by removing the non-conductive polypropylene biorings and inoculating both reactors with granular (non-homogenized) anaerobic sludge. The BEAD reactor design remained unchanged, although it was also inoculated with granular anaerobic sludge, as opposed to the homogenized sludge in the previous experiment.

Table 2 outlines key characteristics of the SPS feedstock utilized throughout this experiment. Notably, a settler was used to remove fine solids from the SPS liquid. Accordingly, the influent stream contained a relatively high concentration of short and medium chain fatty acids. Medium and long chain fatty acids are known to inhibit methanogenic microorganisms.

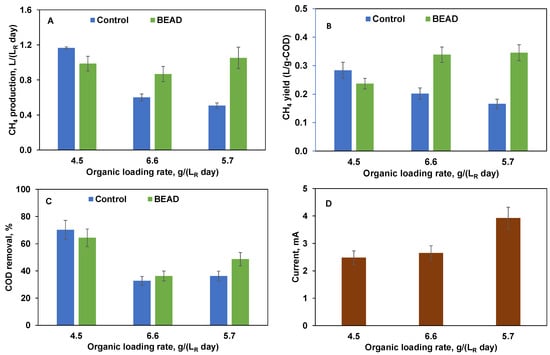

Figure 5 compares the performances of the two reactors at the three tested organic loads. At a relatively low organic load of 4.5 g (LR day)−1, the two reactors demonstrated comparable performance, exhibiting similar average volumetric rates of CH4 production and CH4 yields, which is consistent with the results obtained in the two previous experiments using LBR leachate. Moreover, the COD removal efficiency and biogas composition were similar, with values ranging between 65–70% and 64–68%, respectively.

Figure 5.

BEAD and Control reactor operation on screw press separated (SPS) food waste (Montreal, reactor temperature 35 °C) showing (A) CH4 production, (B) CH4 yield, (C) COD removal efficiency, and (D) BEAD current at three tested organic loading rates. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the measurements.

The differences between the two reactors became more apparent once the organic load was increased to 6.6 g (LR day)−1. This organic load corresponded to organic overload conditions, with acetate, propionate, and butyrate concentrations increasing to 3700 mg L−1, 2020 mg L−1, 1200 mg L−1, respectively, and a total VFA concentration of 6920 mg L−1. The corresponding sCOD values were 9600 mg L−1. 14,090 mg L−1, respectively. Consequently, this organic overload led to a nearly 50% decrease in CH4 production in the Control reactor (Figure 5A). Also, CH4 yield in this reactor dropped below 0.2 L g−1 (Figure 5B), thereby confirming reactor overload.

At the same time, CH4 production in the BEAD reactor remained relatively unchanged (Figure 5B), although VFA concentrations were also high: 2340 mg L−1, 2420 mg L−1, 2150 mg L−1, respectively, resulting in a total VFA concentration of 6910 mg L−1. Remarkably, in spite of such high VFA levels, CH4 yield progressively increased towards the end of this phase, approaching 0.35 L g−1, which exceeded that at a load of 4.4 g (LR day)−1 (Figure 5B).

In an attempt to restore the Control reactor performance, in the following experimental phase, the organic load was reduced to 5.7 g (LR day)−1 for both reactors. Consequently, the volumetric rate of CH4 production improved in the BEAD reactor, while both CH4 production and yield further declined in the Control reactor. VFA analysis corroborated further increase of BEAD reactor capacity for COD removal showing a decrease in total VFA concentrations to 4860 mg L−1. Meanwhile total VFA concentration in the Control reactor increased to 7530 mg L−1 reflecting continuing organic overload.

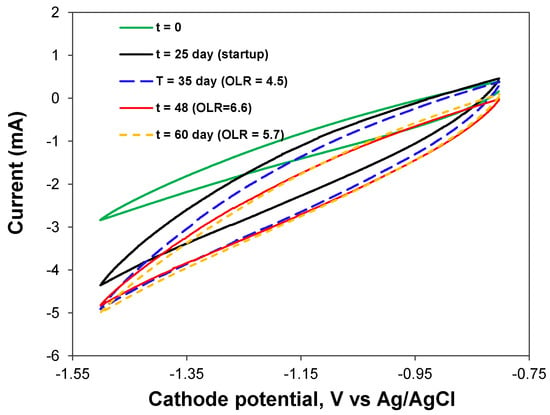

Stable performance of the BEAD reactor with increasing activity of the electroactive bacteria was confirmed through current measurements (Figure 5D) and cyclic voltammetry (Figure 6). Both measurements indicated a progressive increase in current, indicative of an augmented population of electroactive bacteria. In addition, the broadening of the cyclic voltammograms (CV) relative to that at the experiment startup can be attributed to the growth of electroactive biofilm. Considering the absence of metal catalysts at both anode and cathode electrodes, it can be inferred that anodophilic and cathodophilic biofilms developed on the surface of conductive biorings, although electrochemical oxidation of organic materials at the anode cannot be completely excluded.

Figure 6.

BEAD reactor cyclic voltammograms acquired at different phases of BEAD reactor operation.

As discussed earlier, the improved CH4 production can be attributed to both direct and indirect (through acetate and hydrogen) pathways of CH4 formation at the cathode. While more insights into electrode–microorganism charge transfer mechanisms can be gained using impedance spectroscopy (IES), this electrochemical technique could damage electroactive biofilm due to generation of reactive species at the electrode and pH changes. Nevertheless, detailed electrochemical characterization, which also can include measuring current distribution in 3-dimensional electrodes comprising multiple c-rings, might be of interest for future studies.

Previous studies of bioelectrochemically enhanced anaerobic reactors have emphasized the substantial presence of acetoclastic microorganisms at the cathode [53,54]. In particular, significant presence of Methanosarcinales was observed in a bioelectrochemical reactor equipped with stainless steel electrodes [28], while in another study, hydrogenotrophic Methanobacterium and Methanocorpusculum dominated cathodic biofilm of a microbial electrolysis cell [31]. These species are capable of producing CH4 both from acetate and H2. Given the high acetoclastic activity of the inoculum sludge, acetate produced by the acetogenic bacteria is expected to be converted to CH4. However, considering the high acetate concentration at elevated organic loads, the proliferation of hydrogenotrophic methanogens can be considered as a more plausible explanation for increased CH4 production in the BEAD reactor. Indeed, a significant contribution of hydrogenotrophic methanogens to CH4 production in microbial electrolysis and microbial electrosynthesis cells has been previously observed [14,55,56]. Furthermore, CH4 production through direct electron transfer can be hypothesized [18,27,57].

Evaluating the contribution of bioelectrochemical pathways to the overall observed CH4 production involved calculating the difference between CH4 produced in the BEAD and control reactors and comparing it with the anticipated bioelectrochemical CH4 production. The latter was determined based on the assumption of 100% Coulombic Efficiency in Equation (1). According to this calculation, at an OLR of 6.6 g (LR d)−1, only 11% of the difference between CH4 production in the BEAD and Control reactors (SPS-separated feedstock) can be attributed to bioelectrochemical CH4. This value somewhat increased in the experiment conducted at the NRC laboratory (Montreal) using leachate as a feedstock, where the highest current of 11.9 mA was observed at an OLR of 8.3 g (LR d)−1 (Figure 3). Consequently, in this test bioelectrochemical CH4 production accounted for 25–30% of the increase in CH4 production. Notably, since these values are based on the assumed 100% Coulombic efficiency, the calculated values represent an upper limit of the bioelectrochemical contribution. The actual contribution to CH4 production is expected to be lower due to electron losses to competing reactions (e.g., redox processes, biomass growth).

Considering that CH4 production in BEAD was increased up to 30% as compared to Control reactor and exceeded the estimations based on the observed current, a significant part of this increase can be attributed to the improved interspecies electron transfer (IET) within the anodic and cathodic biofilms. Indeed, several previous studies demonstrated increased CH4 production in the presence of conductive materials such as carbon powder and biochar, which facilitated electron exchange between different members of the mixed anaerobic microbial consortium [58,59].

Detailed biomolecular characterization of biofilms and suspended microbial populations of the BEAD reactor would be instrumental in enhancing our understanding of this complex system. Additionally, such detailed characterization of microbial populations might help to understand and differentiate between contributions of microbial biofilms formed at the anode and cathode surface and suspended biomass, including granular biomass introduced to the reactor during its inoculation. The improved performance of an anaerobic digestor equipped with electrodes was previously observed and attributed to improved biomass (biofilm) retention [60].

Furthermore, several previous AD-MEC studies have reported improved CH4 production and yield, consistent with the results of this study. For example, Yin et al. [61] reported a 24% increase in CH4 yield in AD-MEC tests using synthetic wastewater, while a 22% increase was observed in an AD-MEC system fed with waste activated sludge [62]. Even greater improvements in CH4 production and yield have been observed in other studies. For instance, Park et al. [17] reported a 1.7-fold increase in CH4 production and nearly 4-fold reduction in stabilization time. Although none of these studies employed the same reactor and electrode design making direct performance comparison difficult, it can be concluded that the results of this study agree well with the broadly observed trend of improved reactor performance and stability in AD-MEC systems.

3.3. Implications of Using BEAD for Food Waste Conversion to Biogas

The experimental results described above provide strong evidence of enhanced biogas production under bioelectrochemical conditions. The increased CH4 production enables more efficient renewable energy recovery from organic waste. Importantly, in addition to the increased CH4 production, reactor stability also improved. The stability of anaerobic reactors is of utmost importance for successful application of AD technology, particularly in small and remote communities. Such communities often rely on high-cost fossil fuels for energy production and lack alternative sources of energy due to limited agricultural activity and harsh climate that limits solar and wind energy generation. In these communities, food waste serves as a viable source of renewable energy. Nevertheless, attempts to utilize biodegradable food waste for biogas production are hindered by the high cost of anaerobic reactors and the substantial expertise required for successful reactor operation. Consequently, a significant amount of food waste is landfilled, posing environmental challenges such as the contamination of the delicate northern environment with leachates rich in nitrogen and phosphorus. Moreover, anaerobic degradation of landfilled food waste results in a considerable release of CH4, a potent greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere [63].

In more temperate climates, the high sensitivity of AD to feedstock composition often results in reactors being operated at low organic loads. Many anaerobic digesters are built using the continuous stirred tank reactor (CSTR) design rather than a more efficient high-rate UASB design due to the simpler operation and higher stability of CSTR reactors. Such CSTR-based anaerobic digesters treating food waste are typically operated at OLR in the range of 2–5 g COD (L d)−1 to avoid excessive VFA accumulation and process instability. Operation such OLR ranges necessitate long hydraulic retention times of 20–30 days [5,6,7] and oversized reactor volumes to maintain stable performance. In contrast, the BEAD reactor evaluated in this study demonstrated stable operation and enhanced methane production at organic loading rates up to 7–8 g COD (L d)−1, even under conditions that led to organic overload in the control reactor. This highlights the potential of integrating bioelectrochemical pathways with high-rate reactor configurations to achieve high volumetric methane productivity without compromising process stability.

4. Conclusions

This proof-of-concept study evaluated CH4 production in a high-rate UASB-based BEAD reactor and compared its performance with that of a conventional UASB reactor. To ensure the robustness of the proposed bioelectrochemical approach, the reproducibility of observed trends, and the broad applicability of the proposed reactor design, experiments were conducted in two different laboratories using similar reactor setups but distinct feedstocks and operating temperatures. Also, to assess long-term reactor performance, both the BEAD and Control reactors were operated for a combined total of 141 days.

In all experiments, the BEAD reactor consistently demonstrated enhanced CH4 production and yield, as well as improved reactor stability under high organic loading conditions, compared to the Control reactor. On average, CH4 production and yield in the BEAD reactor were increased by 20–30%. Notably, this improvement increased to nearly 50% when the reactors were operated with SPS liquid at the highest tested organic load, which caused overloading of the Control, whereas the BEAD reactor maintained stable performance. These results suggest that bioelectrochemical systems can significantly enhance the activity of electroactive microorganisms, leading to increased methane output and greater reactor stability.

While the current experimental results provide compelling evidence of the BEAD reactor improved performance compared to the conventional UASB design, scaling up the BEAD approach requires long-term studies to validate its performance over extended periods (e.g., beyond 6 months) and at even lower temperatures. Notably, bioelectrochemical systems, such as microbial electrolysis cells, have previously demonstrated effective operation at low mesophilic temperatures, e.g., 15–25 °C. Given the substantial energy requirements for maintaining a typical mesophilic temperature of 35–37 °C in a UASB reactor, operating the BEAD reactor at lower mesophilic temperatures could significantly reduce energy consumption in temperate and cold climates facilitating BEAD technology acceptance. Moreover, a comprehensive techno-economic assessment is required to identify organic loading rates and reactor operating temperatures that balance CH4 production, energy input, and process stability for full-scale applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.H. and B.T.; Experimental work: V.S., J.P.-F., H.L., E.N. and B.T.; Data curation: V.S., A.H., B.Ö., J.P.-F., E.N. and B.T.; Formal analysis and results validation: V.S., A.H., B.Ö., H.L., E.N. and B.T.; Funding acquisition: A.H., B.Ö. and B.T.; Methodology: A.H., B.Ö. and B.T.; Supervision: A.H. and B.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Reactor operation at Carleton University was supported by NSERC and AAFC. Research at NRC received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Assistance of Yunfei Liu in the reactor operation at NRC is greatly appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- De Gioannis, G.; Muntoni, A.; Polettini, A.; Pomi, R.; Spiga, D. Energy recovery from one- and two-stage anaerobic digestion of food waste. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Outlook for Biogas and Biomethane; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Anwar, N.; Ma, Z.; Liu, G.; Zhang, R. Effect of Organic Loading Rate on Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste under Mesophilic and Thermophilic Conditions. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 2976–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip, A.; Bhatt, S.M.; Sharma, N.; Poudel, B. Enhanced Biogas Production Using Anaerobic Co-digestion of Animal Waste and Food Waste: A Review. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2024, 30, 761–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.S.; Kim, B.; Chung, I. Anaerobic Treatment of Food Waste Leachate for Biogas Production Using a Novel Digestion System. Environ. Eng. Res. 2012, 17, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Yun, Y.-M. Effect of operation temperature on anaerobic digestion of food waste: Performance and microbial analysis. Fuel 2017, 209, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusín, J.; Chamrádová, K.; Basinas, P. Two-stage psychrophilic anaerobic digestion of food waste: Comparison to conventional single-stage mesophilic process. Waste Manag. 2021, 119, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Hong, X.; Yang, H.; Yu, X.; Fang, S.; Bai, Y.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Yan, L.; Wang, W.; et al. Effect of hydraulic retention time on anaerobic co-digestion of cattle manure and food waste. Renew. Energy 2020, 150, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Frear, C.; Wang, Z.-W.; Yu, L.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X.; Chen, S. A simple methodology for rate-limiting step determination for anaerobic digestion of complex substrates and effect of microbial community ratio. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 134, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Zhu, N. Progress in inhibition mechanisms and process control of intermediates and by-products in sewage sludge anaerobic digestion. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atelge, M.R.; Atabani, A.E.; Banu, J.R.; Krisa, D.; Kaya, M.; Eskicioglu, C.; Kumar, G.; Lee, C.; Yildiz, Y.Ş.; Unalan, S.; et al. A critical review of pretreatment technologies to enhance anaerobic digestion and energy recovery. Fuel 2020, 270, 117494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang Bejarano, A.; Champagne, P. Optimization of biogas production during start-up with electrode-assisted anaerobic digestion. Chemosphere 2022, 3012, 134739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, T.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, L.; Tao, Y.; He, X.; Li, D.; Yan, Z. A new upgraded biogas production process: Coupling microbial electrolysis cell and anaerobic digestion in single-chamber, barrel-shape stainless steel reactor. Electrochem. Commun. 2014, 45, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vrieze, J.; Arends, J.B.A.; Verbeeck, K.; Gildemyn, S.; Rabaey, K. Interfacing anaerobic digestion with (bio)electrochemical systems: Potentials and challenges. Water Res. 2018, 146, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Buisman, C.J.N.; ter Heijne, A. Bioelectrochemical enhancement of methane production in low temperature anaerobic digestion at 10C. Water Res. 2016, 99, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Lin, R.; Mao, J.; Deng, C.; Ding, L.; O’Shea, R.; Wall, D.M.; Murphy, J.D. Improving the efficiency of anaerobic digestion and optimising in-situ CO2 bioconversion through the enhanced local electric field at the microbe-electrode interface. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 304, 118245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, B.; Tian, D.; Jun, H. Bioelectrochemical enhancement of methane production from highly concentrated food waste in a combined anaerobic digester and microbial electrolysis cell. Biores. Technol. 2018, 247, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villano, M.; Monaco, G.; Aulenta, F.; Majone, M. Electrochemically assisted methane production in a biofilm reactor. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 9467–9472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chang, J.-S.; Lee, D.-J. Integrating anaerobic digestion with bioelectrochemical system for performance enhancement: A mini review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 345, 126519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dhar, B.R. A critical review of microbial electrolysis cells coupled with anaerobic digester for enhanced biomethane recovery from high-strength feedstocks. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 52, 50–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauwaert, P.; Verstraete, W. Methanogenesis in membraneless microbial electrolysis cells. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 82, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Cai, W.; Guo, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, C.; Varrone, C.; Wang, A. Microbial electrolysis contribution to anaerobic digestion of waste activated sludge, leading to accelerated methane production. Renew. Energ. 2016, 91, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, G.K.; Logan, B.E. Multi-electrode continuous flow microbial electrolysis cell for biogas production from acetate. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 8848–8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eerten-Jansen, M.; Jansen, N.; Plugge, C.M.; de Wilde, V.; Buisman, C.; ter Heijne, A. Analysis of the mechanisms of bioelectrochemical methane production by mixed cultures. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2014, 90, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozendal, R.A.; Hamelers, H.V.M.; Rabaey, K.; Keller, J.; Buisman, C.J.N. Towards practical implementation of bioelectrochemical wastewater treatment. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Xing, D.; Logan, B. Direct biological conversion of electrical current into methane by electromethanogenesis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 3953–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villano, M.; Aulenta, F.; Ciucci, C.; Ferri, T.; Giuliano, A.; Majone, M. Bioelectrochemical reduction of CO2 to CH4 via direct and indirect extracellular electron transfer by a hydrogenophilic methanogenic culture. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 3085–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantoni, S.; Molognoni, D.; Sánchez-Cueto, P.; De Soto, C.; Bosch-Jimenez, P.; Ghemis, R.; Borràs, E. Bioelectrochemically-improved anaerobic digestion of fishery processing industrial wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 65, 105848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Rodriguez, C.; Nagendranatha Reddy, C.; Min, B. Enhanced methane production from acetate intermediate by bioelectrochemical anaerobic digestion at optimal applied voltages. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 127, 105261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Tartakovsky, B.; Örmeci, B.; Li, H.; Hussain, A. Combining a solid-state submerged fermenter with bioelectrochemically enhanced anaerobic digestion (BEAD) process for enhanced methane (CH4) production from food waste: Effects of the organic loading rates and applied voltages. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ren, Z.J.; Huang, C.; Liu, B.; Ren, N.; Xing, D. Multiple syntrophic interactions drive biohythane production from waste sludge in microbial electrolysis cells. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, J.E.; Bakke, R. Enhancing hydrolysis with microaeration. Water Sci. Technol. 2006, 53, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Choi, G.; Lee, C. Enhancing anaerobic digestion of dewatered sewage sludge through thermal hydrolysis pretreatment: Performance evaluation and microbial community analysis. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 57, 104617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenigün, O.; Demirel, B. Ammonia inhibition in anaerobic digestion: A review. Process Biochem. 2013, 48, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xing, W.; Li, R. Real-time recovery strategies for volatile fatty acid-inhibited anaerobic digestion of food waste for methane production. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 265, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisowmeya, G.; Chakravarthy, M.; Nandhini Devi, G. Critical considerations in two-stage anaerobic digestion of food waste—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radadiya, P.; Lee, J.; Venkateshwaran, K.; Benn, N.; Lee, H.-S.; Hussain, A. Acidogenic fermentation of food waste in a leachate bed reactor (LBR) at high volumetric organic Loading: Effect of granular activated carbon (GAC) and sequential enrichment of inoculum. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 361, 127705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Örmeci, B.; Singh, A.; Saha, S.; Hussain, A. A novel solid-state submerged fermenter (3SF) for acidogenic fermentation of food waste at high volumetric loading: Effect of inoculum to substrate ratio, design optimization, and inoculum enrichment. Chem. Eng. 2023, 475, 146173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguay-Rioux, F.; Spreutels, L.; Roy, C.; Frigon, J.-C. Assessment of the Feasibility of Converting the Liquid Fraction Separated from Fruit and Vegetable Waste in a UASB Digester. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Ellacuriaga, M.; Aguilar-Pesantes, A.; Carrillo-Peña, D.; García-Cascallana, J.; Smith, R.; Gómez, X. Feasibility of Coupling Anaerobic Digestion and Hydrothermal Carbonization: Analyzing Thermal Demand. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehari, B.B.; Chang, S.; Hong, Y.; Chen, H. Temperature-Phased Biological Hydrolysis and Thermal Hydrolysis Pretreatment for Anaerobic Digestion Performance Enhancement. Water 2018, 10, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I.; Rackemann, D.; Ramirez, J.; Cronin, D.J.; Moghaddam, L.; Beltramini, J.N.; Te’O, J.; Li, K.; Shi, C.; Doherty, W.O.S. Exploring the potential for biomethane production by the hybrid anaerobic digestion and hydrothermal gasification process: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Han, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhi, Z.; Zhang, R.; Cai, T.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, X.; Song, Y.; Zhen, G. Microbial mechanism underlying high methane production of coupled alkali-microwave-H2O2-oxidation pretreated sewage sludge by in-situ bioelectrochemical regulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 305, 127195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; He, L.; Liu, M.; Xiang, J.; Chen, Y.; Gu, L.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Pan, W.; et al. Enhancing Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste by Combining Carriers and Microaeration: Performance and Potential Mechanisms. ACS ES&T Eng. 2024, 4, 2506–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA; AWWA; WEF. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 19th ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Carrera, L.; Escapa, A.; Mehta, P.; Santoyo, G.; Guiot, S.R.; Morán, A.; Tartakovsky, B. Microbial electrolysis cell scale-up for combined wastewater treatment and hydrogen production. Biores. Technol. 2012, 130, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasco-Gomez, R.; Batlle-Vilanova, P.; Villano, M.; Balaguer, M.D.; Colprim, J.; Puig, S. On the Edge of Research and Technological Application: A Critical Review of Electromethanogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kracke, F.; Deutzmann, J.S.; Gu, W.; Spormann, A.M. In situ electrochemical H2 production for efficient and stable power-to-gas electromethanogenesis. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 6194–6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eerten-Jansen, M.; Ter Heijne, A.; Buisman, C.J.N.; Hamelers, H.V.M. Microbial electrolysis cells for production of methane from CO2: Long-term performance and perspectives. Int. J. Energy Res. 2012, 36, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Giovannini, C. Recent and Future Advances in Water Electrolysis for Green Hydrogen Generation: Critical Analysis and Perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jia, H.; Yong, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; Cao, Z.; Kruse, A.; Wei, P. Effects of different biofilm carriers on biogas production during anaerobic digestion of corn straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habouzit, F.; Hamelin, J.; Santa-Catalina, G.; Steyer, J.P.; Bernet, N. Biofilm development during the start-up period of anaerobic biofilm reactors: The biofilm Archaea community is highly dependent on the support material. Microb. Biotechnol. 2014, 7, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevin, K.P.; Woodard, T.L.; Franks, A.E.; Summers, Z.M.; Lovley, D.R. Microbial Electrosynthesis: Feeding Microbes Electricity To Convert Carbon Dioxide and Water to Multicarbon Extracellular Organic Compounds. mBio 2010, 1, e00103-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xafenias, N.; Mapelli, V. Performance and bacterial enrichment of bioelectrochemical systems during methane and acetate production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 21864–21875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabranska, J.; Pokorna, D. Bioconversion of carbon dioxide to methane using hydrogen and hydrogenotrophic methanogens. Biotech. Adv. 2018, 36, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantoni, S.; Santiago, Ó.; Weiler, J.R.; Knoll, M.T.; Lapp, C.J.; Gescher, J.; Kerzenmacher, S. Comparative study of bioanodes for microbial electrolysis cells operation in anaerobic digester conditions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xiao, J.; Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Sun, D.; Cheng, X.; Li, P.; Dang, Y.; Smith, J.A.; Holmes, D.E. High efficiency in-situ biogas upgrading in a bioelectrochemical system with low energy input. Water Res. 2021, 197, 117055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; Nishi, K.; Koyama, M.; Toda, T.; Matsuyama, T. Combined effects of various conductive materials and substrates on enhancing methane production performance. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 178, 106977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, X.; Chen, C.; Xu, L.; Du, Z.; Gu, L.; Xiang, P.; Shi, D.; Huangfu, X.; Liu, F. Conductive materials enhance microbial salt-tolerance in anaerobic digestion of food waste: Microbial response and metagenomics analysis. Environ. Res. 2023, 227, 115779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vrieze, J.; Gildemyn, S.; Arends, J.B.A.; Vanwonterghem, I.; Verbeken, K.; Boon, N.; Verstraete, W.; Tyson, G.W.; Hennebel, T.; Rabaey, K. Biomass retention on electrodes rather than electrical current enhances stability in anaerobic digestion. Water Res. 2014, 54, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Q.; Zhu, X.; Zhan, G.; Bo, T.; Yang, Y.; Tao, Y.; He, X.; Li, D.; Yan, Z. Enhanced methane production in an anaerobic digestion and microbial electrolysis cell coupled system with co-cultivation of Geobacter and Methanosarcina. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 42, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Quan, X. Enhanced production of methane from waste activated sludge by the combination of high-solid anaerobic digestion and microbial electrolysis cell with iron–graphite electrode. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 259, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, T.; Feng, H.; Chen, S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Landfills: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.